Abstract

BACKGROUND

Physician disclosure of medical errors to institutions, patients, and colleagues is important for patient safety, patient care, and professional education. However, the variables that may facilitate or impede disclosure are diverse and lack conceptual organization.

OBJECTIVE

To develop an empirically derived, comprehensive taxonomy of factors that affects voluntary disclosure of errors by physicians.

DESIGN

A mixed-methods study using qualitative data collection (structured literature search and exploratory focus groups), quantitative data transformation (sorting and hierarchical cluster analysis), and validation procedures (confirmatory focus groups and expert review).

RESULTS

Full-text review of 316 articles identified 91 impeding or facilitating factors affecting physicians' willingness to disclose errors. Exploratory focus groups identified an additional 27 factors. Sorting and hierarchical cluster analysis organized factors into 8 domains. Confirmatory focus groups and expert review relocated 6 factors, removed 2 factors, and modified 4 domain names. The final taxonomy contained 4 domains of facilitating factors (responsibility to patient, responsibility to self, responsibility to profession, responsibility to community), and 4 domains of impeding factors (attitudinal barriers, uncertainties, helplessness, fears and anxieties).

CONCLUSIONS

A taxonomy of facilitating and impeding factors provides a conceptual framework for a complex field of variables that affects physicians' willingness to disclose errors to institutions, patients, and colleagues. This taxonomy can be used to guide the design of studies to measure the impact of different factors on disclosure, to assist in the design of error-reporting systems, and to inform educational interventions to promote the disclosure of errors to patients.

Keywords: medical errors, error reporting, patient safety, disclosure, medical ethics

The disclosure of medical errors is a vital part of ongoing efforts to improve patient safety and the quality of care.1–10 Disclosure of medical error through direct communication with patients and their families is also an integral part of patient care,11–14 and candor about errors between colleagues is essential to professional learning.15–18 However, there are diverse and potent factors that impede a physician's willingness to disclose errors to institutions, patients, and colleagues.5,6,12,16,19–25 Recommendations to address these impediments by changing professional culture7,8,25–29 are accompanied by sobering descriptions of the tension between the transparency promoted by the patient safety movement and the silence induced by the malpractice system.30,31 The number and variety of variables affecting a decision to disclose an error pose serious challenges for those trying to design systems and promote practices that increase disclosure. Because of this complexity, there is a need to define and organize the various influences on error disclosure, both to enhance multifaceted, disclosure-promoting interventions and to aid evaluation and interpretation of the results of such interventions. To address this need, we used qualitative and quantitative methodologies to develop an empirically based, comprehensive taxonomy of factors that may impede or facilitate the voluntary disclosure of errors by physicians.

METHODS

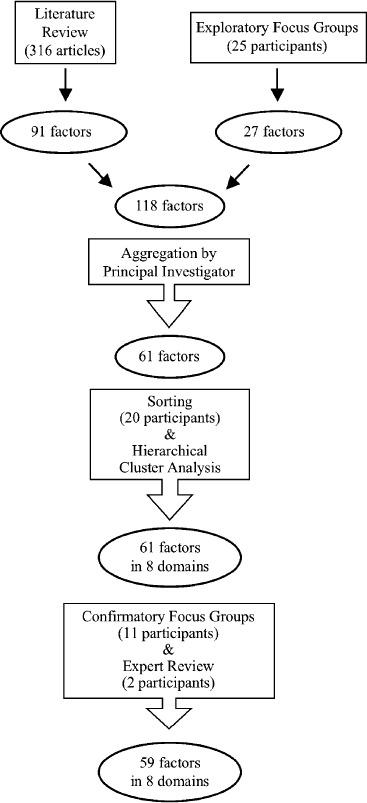

We used a sequence of methodologies to collect qualitative data (structured literature search and exploratory focus groups), perform quantitative data transformation (sorting and hierarchical cluster analysis), and validate our results (confirmatory focus groups and expert review) (Fig. 1). We considered “disclosure” to include admitting errors to patients, discussing them with colleagues, and reporting them to health care institutions. We used the term “factor” to denote a variety of variables (attitudes, emotions, desires, beliefs, circumstances) that may impede or facilitate disclosure. This project was approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board.

FIGURE 1.

Outline of methods for derivation of taxonomy

Literature Review

We performed a MEDLINE search of English-language articles published between January 1975 and March 2003. The Medical Subject Heading terms and key words that we used are reported elsewhere.32 To be included in the review, articles had to (1) have an identifiable first author, (2) address the clinical experience of physicians, and (3) discuss error disclosure or reporting. We selected articles with identifiable first authors in order to be able to abstract data by unique first authors as well as by article, a design that allowed us to quantify results of the literature review by calculating the citation frequency of individual factors that facilitate or impede disclosure.32 We selected articles that addressed the experience of physicians because of their unique professional, legal, and institutional status. All types of articles (empirical studies, reviews, editorial/commentaries, letters, personal narratives, interviews) were reviewed so long as they met the inclusion criteria.

Two investigators (E.W.J. and L.C.K.) screened 4,382 articles by titles. One investigator (E.W.J.) reviewed the entire content of 606 articles and identified 316 articles that satisfied the inclusion criteria; the second investigator (L.C.K.) was consulted whenever there was uncertainty about an article's satisfaction of the inclusion criteria. Bibliographies of included articles were screened for additional articles.

After analyzing 10 articles for factors related to disclosure, 2 investigators created a provisional list of factors that facilitate or impede disclosure to form a data-abstraction template; this template was then tested on another 10 articles and expanded. One investigator (E.W.J.) reviewed the remainder of the articles and consulted with the second investigator (L.C.K.) when uncertain about factor categorization or when a new factor was identified for inclusion in the data-abstraction template. Labels for facilitating and impeding factors were derived through an iterative process. Factors were first named using the language of the articles in which they were found. As more articles were reviewed, labels were modified to reflect similar concepts phrased variously by different authors. This iterative process of naming served to synthesize the linguistic heterogeneity of the literature reviewed.

The second investigator (L.C.K.) reviewed 64 randomly selected articles (20% of sample) to assess the interrater reliability of facilitating and impeding factors. To assess intrarater reliability of the sample, the first investigator (E.W.J.) repeated the data abstraction from these 64 articles after a hiatus of 11 weeks.

Exploratory Focus Groups

We conducted 5 focus groups, segregated by training level, to discuss factors related to physician self-disclosure of medical errors to institutions, patients, and colleagues. We identified convenience samples of fourth-year medical students, resident physicians (internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics), community attending physicians (general internal medicine), and university attending physicians (general internal medicine, family medicine, general pediatrics) (Table 1). Two of the investigators attended each focus group, 1 serving as moderator (L.C.K.) and 1 as assistant (E.W.J.). The moderator adhered to a formal question route (Appendix A) based on the literature review. A physician-investigator served as moderator to enhance the perceived credibility of the focus groups among participants who are professionals. We recognized that a moderator's identity can influence participant discussion, but based on focus group literature33,34 we concluded that the benefits of professional credibility outweighed the risks of undue influence. Sessions lasted 90 minutes and were audiotaped; audiotapes were transcribed verbatim.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics for Exploratory Focus Groups

| n | Age (Mean) | Years Since Medical School Graduation (Mean) | Female (%) | Ever Reported an Error to an Institution (%) | Ever Disclosed a Mistake to a Patient (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fourth-year medical students | 7 | 26 | −1 | 71 | 0 | 29 |

| First-year residents | 6 | 31 | 1 | 33 | 33 | 100 |

| Third-year residents | 3 | 28 | 5 | 67 | 67 | 67 |

| Attending physicians (community) | 3 | 44 | 19 | 0 | 33 | 100 |

| Attending physicians (university) | 6 | 42 | 17 | 33 | 33 | 100 |

We designed an anonymous exit questionnaire to assess participant perceptions about the influence of peers and the moderator. All participants either disagreed or strongly disagreed with the following 2 statements: (1) “The presence of my peers made it hard for me to say what I really thought”; or (2) “The presence of the moderator made it hard for me to say what I really thought.” All participants either agreed or strongly agreed with the following 3 statements: (1) “The moderator made me feel comfortable enough to speak my mind during the discussion,” (2) “The duration of the focus group provided me enough time to say what I wanted to say,” and (3) “Overall, I was able to say what I really thought about the issues we discussed.”

Transcripts were coded for content independently by 2 investigators (E.W.J. and L.C.K.) using the list of factors generated from the literature review and analyzed for new factors or new wording of previously identified factors. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus between the 2 investigators.

Combination and Aggregation of Factors

The factors identified from the focus groups were combined with the factors from the literature review. To increase the feasibility of the next step (pile sorting), 1 investigator (L.C.K.) reviewed all the factors and aggregated into mini-groups those factors that appeared directly related. The factors and factor mini-groups were printed on index cards for the sorting task; cards containing factor mini-groups listed each factor within the mini-group.

Pile Sorting and Hierarchical Cluster Analysis

The pile-sorting task35 involved 9 attending physicians (general internal medicine and family medicine, 7 men and 2 women), 5 resident physicians (internal medicine and family medicine, 2 men and 3 women), and 6 fourth-year medical students (3 men and 3 women), who had not participated in the exploratory focus groups. Participants were given index cards with 1 factor or factor mini-group on each card (ordered alphabetically) and instructed to sort the index cards into 5 to 10 groups by placing together cards that were most related. Participants sorted the cards at their convenience.

The pile-sorting results were entered into a database for hierarchical cluster analysis36 using the CLUSTER procedure in SAS to construct clustering schemes derived from the number of participants who placed a given pair of factors together in a group. This organized the factors according to participants' assessment of the conceptual proximity of each pair of factors. For each pair of factors, we computed a “distance” score, defined as 20 (the total number of participants) minus the number of participants who placed the 2 factors in the same group. Thus, the distance score for a pair of factors was an integer between 0 and 20, with 20 indicating no relatedness and 0 indicating maximum relatedness.

Four types of hierarchical cluster analysis were performed: single linkage, complete linkage, average linkage, and Ward's minimum variance method. Ward's method performed the best because it resulted in unique solutions and higher R2 values and lower semipartial R2 values for a given cluster size.37

Validation: Confirmatory Focus Groups and Expert Review

Eleven of the sorting task participants (3 students, 2 resident physicians, 6 attending physicians) accepted invitations to participate in 1 of 3 focus groups to validate the initial cluster scheme. Focus groups were segregated by training level and moderated by the principal investigator (L.C.K.). Each cluster was individually projected onto a screen. Participants identified items that did not appear to belong in a given cluster. Consensus was required to dismiss or relocate an item to another cluster. Participants were also asked to suggest words that best summarized the factors in each cluster. At the final session involving attending physicians, participants affirmed or rebutted (by consensus) changes that were suggested by the other 2 confirmatory focus groups. Final cluster titles were suggested by the moderator and modified by consensus.

The resulting taxonomy was independently reviewed by 2 expert ethicists, each a full professor with a PhD in ethics. Our choice of experts in ethics who had no particular background in patient safety or error disclosure allowed us to engage conceptual expertise that was unlikely to be accompanied by formal preconceptions about errors or disclosure.

Final Labeling of Factors

To enhance the taxonomy's comprehensibility, we made 3 final adjustments. To express the meaning of factor labels more fully, we added words to factor labels to flesh out the original meaning of a given factor (e.g., “integrity” was changed to “desire to maintain one's integrity”). We reviewed the content of the factor mini-groups (see Appendix B) and, where appropriate, used words from other factors within a given mini-group to modify or expand the final label for that mini-group. In order to condense factors within a domain, we combined some related factors using the conjunction “or.”

RESULTS

Literature Review

Three hundred and sixteen articles, representing 254 unique first authors, were included (109 reviews, 74 editorials/commentaries, 69 empirical studies, 42 letters, 18 personal narratives, 4 interviews). Content analysis of the articles identified 91 factors (53 impeding and 38 facilitating), as shown in Appendix B. Reliability testing showed that the majority of the most commonly cited factors were reproducibly identifiable within and between investigators (κ statistics for the 10 most commonly cited facilitating and impeding factors ranged between 0.47 and 0.96).

The literature review identified 91 factors (53 impeding and 38 facilitating), as shown in Appendix B. The 10 most frequently cited facilitating factors were as follows: accountability, honesty, restitution, trust, reduce malpractice risk, consolation, fiduciary relationship, truth-telling, avoid “cover up,” and informed consent. The 10 most frequently cited impeding factors were as follows: professional repercussions, legal liability, blame, lack of confidentiality, negative patient/family reaction, humiliation, perfectionism, guilt, lack of anonymity, and absence of a supportive forum for disclosure. The 3 most common contexts for error disclosure were as follows: (1) reporting errors to institutions to improve patient safety; (2) discussion of errors among physicians to enhance learning; and (3) informing patients about errors as part of patient care. Statistical analyses (32) showed that the most commonly cited facilitating factors, except for accountability, were more frequently mentioned in articles focusing on disclosing errors to patients, as opposed to institutions or colleagues (P < .001). By contrast, impeding factors showed no consistent differences in the frequency of citation based on the context of disclosure.

Exploratory Focus Groups

Content analysis of focus group transcripts produced 27 new factors (see Appendix B) and resulted in the rewording of some previously identified factors based on focus group vernacular. These new factors tended to focus on the actual experience of disclosing an error—particularly to patients. Participants noted emotional responses to errors such as “that sinking feeling,” the desire to explain the circumstances surrounding an error, and practical difficulties such as lack of time to explain errors to patients. Issues specific to the training environment were also prominent, such as lack of support from supervising physicians, competition with peers, and fear of looking foolish in front of junior colleagues.

Final Taxonomy, with Selected Annotations from Exploratory Focus Groups

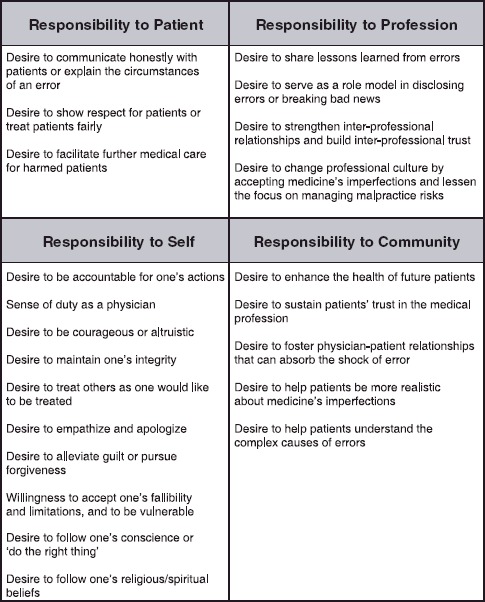

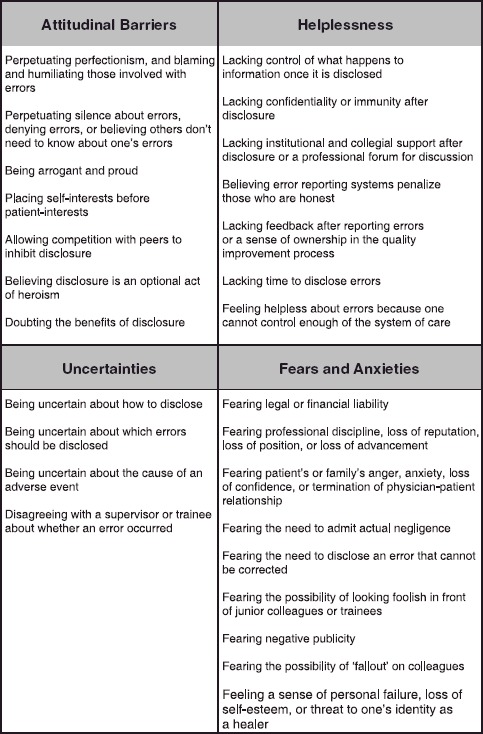

The 27 factors identified from the focus groups were combined with the 91 factors from the literature review for a total of 118 facilitating and impeding factors. All the factors were reviewed by 1 of the investigators (L.C.K.) and those factors that appeared directly related were aggregated into mini-groups, as shown in Appendix B, reducing the number of factors and factor mini-groups to 61. In the pile-sorting task, participants placed the 61 factors and factor mini-groups into an average of 7 piles. In the hierarchical cluster analysis, plots of cluster statistics did not reveal a definitive jump in the values that would suggest an obvious cluster solution. Using Ward's method, we reviewed printouts of 5 different clustering solutions (factors clustered into 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9 clusters) and determined that the 8-cluster solution (R2=.586) was the most satisfactory in terms of clinical interpretation; this solution established the number of domains for the taxonomy as well as the initial contents of the 8 domains. As a result of the confirmatory focus groups, 4 items were relocated, 1 item was deemed redundant and dismissed, and 1 item (“restitution”) could not be categorized due to competing interpretations that resisted consensus. Two expert ethicists found the taxonomy to be comprehensive and recommended changes to the first 4 domain names to increase descriptive clarity and movement of 2 items from 1 domain to another. The final taxonomy comprised of 4 domains of facilitating factors (Fig. 2) and 4 domains of impeding factors (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 2.

Factors that facilitate physician disclosure of medical errors

FIGURE 3.

Factors that impede physician disclosure of medical errors

Responsibility to patient focuses on the physician's fundamental respect for the patient as a person, through open communication and ongoing care. The core of this domain was suggested by a student who said “It boils down to just how you view other people. Do you view them as worthy of knowing?” An intern spoke similarly “That's really the focus of what we're doing here: patient care … it comes down to what's happened with this particular patient.”

Responsibility to self focuses on personal and professional values that derive from the physician's character, commitments, and desire for integrity. An intern stressed the importance of “being accountable for our errors and not being a weasel or arrogant or denying that we ever make errors.” A faculty physician acknowledged the need for courage “If you don't have the guts to say, “I screwed up” to a patient, you're in the wrong business.” A resident commented that “in order to receive forgiveness you have to admit to your wrong,” and another expressed the need to “make amends” with a harmed patient in order to move forward. Participants saw the need to accept fallibility and to be willing to be vulnerable. Such willingness, a student observed, will drive “a lot of your desire to report to anybody because you are going to be vulnerable when you say “I made a mistake.” Some participants articulated spiritual or religious motivations, such as the student who said: “I should be motivated by love and also I'm ultimately responsible to God for my actions … whether I'm deceptive with patients or whether I tell them the truth about what's going on.”

Responsibility to profession focuses on the physician's desire to improve the medical profession through sharing lessons learned, modeling disclosure skills, fostering a culture of disclosure, and providing support to colleagues who are involved with errors. A faculty physician described the need for role modeling in discussing and disclosing errors “If I as a faculty member can't express my own fallibility … how can the learner learn?” A resident said “When people have come out and told the patient, have taken responsibility—it's usually based on just a need to do the right thing and the need to be a good role model for those who are training under you.” A student spoke of the need for support “There's a catharsis in being able to say to your colleagues, ‘This is what happened’ and then to be able to hear, ‘I made that same mistake, I've been there, I know how you feel, this is what I did to correct it.’”

Responsibility to community focuses on the physician's desire to improve the quality of care for all patients, to enhance society's trust in physicians and the medical profession, and to educate the community about medicine's complexities and imperfections. One student's remark about reporting errors to improve systems of care was representative “Your one case may not seem to make a difference, but if there are trends at a certain hospital or in a certain area of the country, this is how we get demographic information, this is how we improve our care … and there are public health implications of reporting, if you feel there's a duty to improve for the greater good.”

Attitudinal barriers focus on a range of attitudes that may hamper disclosure. Perfectionism was a persistent theme in the focus groups. An intern explained “Even though I know it's not logical for me to think that doctors aren't going to make errors, I hold doctors to that standard, that we're going to be perfect and we're not going to make errors.” Participants also drew a connection between silence about errors and the competitive nature of medical training.

A student observed:

[As a student] you're competing within your class, competing with yourself, and trying to reach the academic goals that you want. As a resident you're competing to attain that certain fellowship position. You don't get points for making mistakes; in fact, you get points taken away. It's like the SATs. So admitting to mistakes doesn't exactly help your career…. It's the inherent competition within our career that kind of fuels a lot of people who want to put their mistakes under the carpet and just show off their achievements and try to put themselves in the best light possible.

Uncertainties focus on doubts about how to disclose errors, which ones to disclose, what constitutes an error, and disagreements between clinicians about whether an error occurred. A student expressed the struggle to discern the difference between a complication and an error:

There's a risk that you're going to cause a pneumothorax when you do a thoracentesis…. But if I am the one that causes that pneumothorax, is it because I was an idiot? Do I say, “You know, I collapsed your lung, I'm really sorry, I made a mistake” or do I just present it as, “It's one of the risks, you signed informed consent.” I really struggle with how you even define some of the errors.

A faculty physician described the difficulty of determining whether an error is significant enough to disclose “At what level does the error become big enough that now something needs to be done about it?” A resident spoke of conflicting views between supervisors and trainees “Medicine is vague enough sometimes that even though I feel [an error occurred], there's no higher power for me to appeal to if the higher power within my group feels that the right thing was done.”

Helplessness focuses on dissatisfactions with the process, context, follow-up, and outcome of error disclosure, as well as not having the power necessary to improve the system of care. A student complained of not knowing what will “happen with what you [report], the path [the information] is going to take, and who's going to be reading it,” suggesting that reported errors may be “going down a black hole” and may result in “retributions that come back to you.” An intern described discussion forums at a prior institution that were demoralizing:

Morbidity & mortality conferences were just brutal. We wouldn't go, we wanted nothing to do with them. The students would actually sometimes go to see the residents they didn't like just get toasted.

Participants were disappointed by lack of feedback after reporting errors. A resident complained “So far as I know, [the report] goes to some dead space out there and it's vaporized….”

Fears and anxieties focus on a range of potential negative consequences of error disclosure. Participants spoke about profound personal struggles related to their identities as healers. An intern said “[Patients are] coming in here, they're sort of putting their life in my hands, and they're trusting me and I've violated this trust.” Another intern remarked “Disclosing to the patient makes you admit to yourself that—what's that first tenet of our oath, “First do no harm?”—well, we did harm.” A faculty physician opined “I'm delivering bad news to the patient about something, but I'm also delivering bad news about myself because I have been the cause of that bad news.” A resident articulated the difficulty of apologizing for negligence:

Saying “I'm sorry” has got to be some of the toughest words in any language and we, as physicians, take a lot of pride in the fact that we're pretty smart and capable people…. To make a mistake that acknowledges my own [fallibility] is in a way saying that I'm not as good as I could be.… If it is something like you forgot to deflate the catheter that ends in the patient dying, that's a pretty, pretty serious outcome. Like, if you're flying a jet and you drop the bomb on the wrong person. Those things live in your memory forever….

A resident feared the loss of reputation: “There's the fear of other people saying, ‘Boy, he dropped the ball, he screwed up, he's not really a good doctor, he really doesn't know what he's doing.’ You don't want people pointing fingers at you. It's enough to be pointing fingers at yourself, but you don't want other people to say ‘he doesn't belong among us.’”

DISCUSSION

This taxonomy defines and organizes the complex motivational context surrounding the decision to disclose a medical error, clarifying the host of factors—positive and negative, personal and environmental—that may influence this uniquely challenging process. The taxonomy's impeding factors describe variables that need to be addressed to enhance the likelihood that policies and procedures instituted to increase disclosure will succeed. The facilitating factors describe variables that may help promote error disclosure by encouraging clinicians to connect their personal and professional values with the goals of improving the quality of care, respecting patients through candid communication, and enhancing professional learning.

Amidst current discussions about ways to encourage or mandate error disclosure to institutions or patients, this taxonomy helps define the motivations and concerns that surround the discretionary role of the individual clinician. Although a systems emphasis is necessary to understand the causes of medical errors and the systems-related factors that inhibit their disclosure, the taxonomy reminds us how intrinsically challenging disclosure is for individuals. Policies to increase disclosure need to be informed by the concrete experience of clinicians and the systems within which they operate.

The 2 sides of this taxonomy stress the need to focus both on the factors that impede disclosure and on those that facilitate it. Facilitating factors represent substantial motivational resources that physicians can rely upon in the face of potent fears and anxieties. It is important to explore how these resources may counteract internal threats to a physician's identity as a healer and perceived external threats from aggrieved patients (39% of whom may support punishment for error-committing physicians38) or their attorneys (as candor with patients about errors may not result in fewer lawsuits.30,31)

The development of our taxonomy had limitations. Regarding the literature review: initial screening of articles by titles may have excluded some relevant articles; only 1 investigator analyzed most of the selected articles for content; and although 69 articles were empirically based, the majority of articles represented authors' personal assessments rather than systematically collected data from physicians. Regarding the focus groups, physician participants were generalists; however, only 27 of the factors were identified through focus groups, compared with 91 factors identified from the structured literature review (which was not limited to generalist disciplines), suggesting that the content of our taxonomy should be generalizable. Using a physician-investigator as a moderator may have influenced the content of the discussions, and the risk of social desirability bias is always present. Lastly, our taxonomy was not designed to identify the relative importance of different facilitating or impeding factors, and for the sake of clarity and simplicity, we have listed the factors without explicating the potentially numerous and complex interactions among them.

Our taxonomy suggests several directions for educational and institutional change. First, educators and leaders should acknowledge and address the diversity of facilitating and impeding factors that affect disclosure. Second, the taxonomy should help clinicians view disclosure holistically, that is, as a unified process of information sharing oriented toward patient safety (disclosure to institutions), professional learning (disclosure to colleagues), and direct clinical care (disclosure to patients). Third, the individual's role in reporting and discussing errors should complement the systems orientation of the patient safety movement. Fourth, error disclosure should be included in the teaching of medical ethics and professionalism, as has already been recommended.39 Fifth, innovations to enhance error disclosure should consistently address both sides of the equation: impeding factors should be removed and facilitating factors should be promoted.

Our work suggests a number of research questions for the future. Which facilitating and impeding factors have the greatest influence on disclosure? Does the influence of specific factors vary by level of training and speciality? Does the influence of specific factors vary according to the context of disclosure (to institutions, colleagues, or patients)? How does professional environment affect attitudes toward disclosure? Do current training practices support or discourage disclosure? Future research will need to ascertain whether educational and institutional interventions actually reduce the influence of impeding factors or enhance the influence of facilitating factors.

This taxonomy provides a comprehensive framework of the diverse factors that may affect a physician's willingness to disclose medical errors to institutions, patients, and colleagues. It advances our understanding of this complex subject by articulating and organizing the wide range of facilitating and impeding factors that are cited in the literature and described by physicians. Although hospitals and leaders increasingly endorse the importance of disclosing errors, there is evidence to suggest that such endorsements may not be reflected in practice.40,41 To advance the transition from institutional ideals to individual practice, it is important to acknowledge and engage the factors that influence disclosure. To this end, our taxonomy should be useful to policy makers, health care administrators, and educational leaders who are endeavoring to increase disclosure through better error-reporting systems, more candid dialogue with affected patients, and enhanced professional forums to promote learning.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Kaldjian is supported by funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation's Generalist Physician Faculty Scholars Program (grant # 45446). We are grateful to Dr. Paul Haidet for his review of an earlier version of this manuscript, to 2 expert ethicists, and to the many focus group participants. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Supplementary Material

The following supplementary material is available for this article online at http://www.blackwell-synergy.com

Question Route for Exploratory Focus Groups

Results of Aggregation to Reduce the Number of Factors Prior to Sorting

REFERENCES

- 1.Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weingart SN, Wilson RM, Bibberd RW, Harrison B. Epidemiology of medical error. BMJ. 2000;320:774–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7237.774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leape LL. Error in medicine. JAMA. 1994;272:1851–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leape LL, Woods DD, Hatlie MJ, Kizer KW, Schroeder SA, Lundberg GD. Promoting patient safety by preventing medical error. JAMA. 1998;280:1444–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.16.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reason J. Human error: models and management. BMJ. 2000;320:768–70. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7237.768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altman DE, Clancy C, Blendon RJ. Improving patient safety—five years after the IOM report. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2041–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leape LL. Reporting of adverse events. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1633–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMNEJMhpr011493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flynn E, Jackson JA, Lindgren K, Moore C, Poniatowski L, Youngberg B. Shining the Light on Errors: How Open Should We Be? Oak Brook, IL: University Health System Consortium; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weissman JS, Annas CL, Epstein AM, et al. Error reporting and disclosure systems: views from hospital leaders. JAMA. 2005;293:1359–66. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.11.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aspden P, Corrigan JM, Wolcott J, Erickson SM. Patient Safety: Achieving a New Standard for Care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2004. p. 237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baylis F. Errors in medicine: nurturing truthfulness. J Clin Ethics. 1997;8:336–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosner F, Berger JT, Kark P, Potash J, Bennett AJ. Disclosure and prevention of medical errors. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2089–92. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Council on ethical and judicial affairs. Code of Medical Ethics. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 1998. pp. 141–2. –1999. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gallagher TH, Waterman AD, Ebers AG, Faser VJ, Levinson W. Patients' and physicians' attitudes regarding the disclosure of medical errors. JAMA. 2003;289:1001–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.8.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McIntyre N, Popper K. The critical attitude in medicine: the need for a new ethics. BMJ. 1983;287:1919–23. doi: 10.1136/bmj.287.6409.1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu AW, Folkman S, McPhee SJ, Lo B. Do house officers learn from their mistakes? JAMA. 1991;265:2089–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orlander JD, Barber TW, Fincke BG. The morbidity and mortality conference: the delicate nature of learning from error. Acad Med. 2002;77:1001–6. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200210000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pierluissi E, Fischer MA, Campbell AR, Landefeld CS. Discussion of medical errors in morbidity and mortality conferences. JAMA. 2003;290:2838–42. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.21.2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaldjian LC. Disclosing our own medical errors: are three good reasons enough? Johns Hopkins Adv Stud Med. 2003;3:51–2. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finkelstein D, Wu AW, Holtzman NA, Smith MK. When a physician harms a patient by medical error: ethical, legal, and risk-management considerations. J Clin Ethics. 1997;8:330–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greely HT. Do physicians have a duty to disclose mistakes? West J Med. 1999;171:82–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sexton JB, Thomas EJ, Helmreich RL. Error, stress, and teamwork in medicine and aviation: cross-sectional surveys. BMJ. 2000;320:745–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7237.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu AW, Cavanaugh TA, McPhee SJ, Lo B, Micco GP. To tell the truth: ethical and practical issues in disclosing medical mistakes to patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:770–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.07163.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kapp MB. Legal anxieties and medical mistakes: barriers and pretexts. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:787–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.07167.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brennan TA. The Institute of medicine report on medical errors—could it do harm? N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1123–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004133421510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berwick DM. Not again! preventing errors lies in redesign—not exhortation. BMJ. 2001;322:247–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7281.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Studdert DM, Brennan TA. No-fault compensation for medical injuries: the prospect of error prevention. JAMA. 2001;286:217–23. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen MR. Why error reporting systems should be voluntary. BMJ. 2000;320:728–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7237.728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schoenbaum SC, Bovbjerg RR. Malpractice reform must include steps to prevent medical injury. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:51–3. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-1-200401060-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Studdert DM, Mello MM, Brennan TA. Medical malpractice. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:283–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr035470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kachalia A, Shojania KG, Hofer TP, Piotrowski M, Saint S. Does full disclosure of medical errors affect malpractice liability? Jt Comm J Qual Safety. 2003;29:503–11. doi: 10.1016/s1549-3741(03)29060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaldjian LC, Jones EW, Rosenthal GE. Facilitating and impeding factors for physicians' error disclosure: a structured literature review. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Safety. 2006;32:188–98. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(06)32024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krueger RA. Moderating Focus Groups (Focus Group Kit, Vol. 4) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. pp. 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus Groups. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2000. pp. 97–101. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weller SC, Romney AK. Systematic Data Collection. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1988. pp. 20–31. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Everitt B. Cluster Analysis. London: Heinemann; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharma S. Applied Multivariate Techniques. New York: Wiley; 1996. pp. 185–236. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mazor KM, Simon SR, Yood RA, et al. Health plan members' views about disclosure of medical errors. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:409–18. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-6-200403160-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physician charter. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:243–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-3-200202050-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leape LL, Berwick DM. Five years after To Err is Human: what have we learned? JAMA. 2005;293:2384–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.19.2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gallagher TH, Lucas MH. Should we disclose harmful medical errors to patients? If so, how? J Clin Outcomes Manage. 2005;12:253–9. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Question Route for Exploratory Focus Groups

Results of Aggregation to Reduce the Number of Factors Prior to Sorting