Abstract

In this study, we compared the uterine tissue of estrogen receptor (ER)β−/− mice and their WT littermates for differences in morphology, proliferation [the percentage of labeled cells 2 h after BrdUrd injection and EGF receptor (EGFR) expression], and differentiation (expression of progesterone receptor, E-cadherin, and cytokeratins). In ovariectomized mice, progesterone receptor expression in the uterine epithelium was similar in WT and ERβ−/− mice, but E-cadherin and cytokeratin 18 expression was lower in ERβ−/− mice. The percentage of cells in S phase was 1.5% in WT mice and 8% in ERβ−/− mice. Sixteen hours after injection of 17β-estradiol (E2), the number of BrdUrd-labeled cells increased 20-fold in WT mice and 80-fold in ERβ−/− mice. Although ERα was abundant in intact mice, after ovariectomy, ERα could not be detected in the luminal epithelium of either WT or ERβ−/− mice. In both untreated and E2-treated mice, ERα and ERβ were colocalized in the nuclei of many stromal and glandular epithelial cells. However, upon E2 + progesterone treatment, ERα and ERβ were not coexpressed in any cells. In WT mice, EGFR was located on the membranes and in the cytoplasm of luminal epithelium, but not in the stroma. In ERβ−/− mice, there was a marked expression of EGFR in the nuclei of epithelial and stromal cells. Upon E2 treatment, EGFR on cell membranes was down-regulated in WT but not in ERβ−/− mice. These findings reveal an important role for ERβ in response to E2 and in the organization, growth, and differentiation of the uterine epithelium.

Keywords: differentiation, proliferation, uterus

Proliferation of epithelial cells (1, 2), uterine hyperemia, fluid uptake (termed water imbibition), recruitment of inflammatory leukocytes from the bloodstream into the stromal compartment (3, 4), and the induction of the progesterone receptor (PR) are caused by 17β-estradiol (E2). Progesterone (P4) inhibits estrogen-induced cell proliferation of the luminal and glandular epithelial compartment (5) and stimulates epithelial differentiation in preparation for embryo implantation. Physiologically and pharmacologically, P4 is important for prevention of endometrial hyperplasia (6). After the cessation of ovarian function, estrogen replacement is needed for preservation of the skeletal, cardiovascular, and central nervous systems. To oppose the proliferative effects of estrogen on the uterus and reduce the risk of endometrial cancer, progesterone is used together with estrogen in hormone replacement therapy after menopause (7, 8).

Most of the known actions of estrogen are mediated by the estrogen receptors (ERs) ERα and ERβ, both of which bind E2 and modulate transcription of E2-responsive genes (9). A single injection of E2 results in a synchronized wave of cell proliferation, with DNA synthesis in epithelial cells beginning 6–9 h after E2 injection and peaking at 12–15 h. DNA synthesis is followed by a wave of cell division (1, 2, 10). P4 elicits its function through binding to the PR.

During the secretory phase of the estrus cycle, endometrial stroma becomes predecidual in preparation for decidualization if pregnancy occurs. Decidualization can be induced by P4 and E2 and involves EGF action on the stromal EGF receptor (EGFR). E2-induced epithelial cell proliferation is mediated by stromal ERα. It is currently thought that in the uterus, stromal ERα induces secretion of EGF. Although ERα is the predominant ER in the adult rodent uterus, ERβ mRNA has also been detected in WT and ERα−/− mouse uteri (11). Targeted disruption of ERβ in mice (12) has revealed roles for ERβ in differentiation of various epithelial and nonepithelial cell types in many tissues and organs (13–19). In the uteri of ERβ−/− mice, there is an exaggerated responsiveness to E2, resulting in enlargement of the lumen, increase in volume and protein content of uterine secretion, and induction of aberrant epithelial expression of PR after E2 injection (13). ERβ is expressed in all cell types of uterine tissue and modulates estrogenic function by inhibiting ERα function (13, 20). ERβ has been reported to play a role in decidualization of rat uterus (21) and in human cervical ripening, which is essential for parturition (22).

To better understand the role of ERβ in the regulation of uterine tissue development, we have compared the uteri of WT and ERβ−/− mice by observing markers of proliferation and differentiation before and after treatments with E2 alone or E2 + P4.

Results

E-Cadherin Expression and ERβ−/− Uterus Epithelium.

Uterus sections from ERβ−/− mice and their WT littermates were stained with antibodies specific for E-cadherin. Expression of E-cadherin on the lateral surfaces of the epithelial cells was markedly lower in untreated ERβ−/− mice than in WT mice (Fig. 1A and D). Upon treatment with E2 or with E2 + P4, expression of E-cadherin increased in both WT and ERβ−/− mice (Fig. 1 B and C and E and F, respectively). Visualization of E-cadherin on the epithelial membrane and cell borders permitted a clear picture of the shape of the epithelial cells and revealed that in ERβ−/− mice, the lateral surfaces of the epithelial cells were deformed.

Fig. 1.

Immunohistochemical detection of E-cadherin. Nine-week-old mice received a single s.c. injection of 150 μl of olive oil containing no hormone (A and D), 100 ng of E2 (B and E), or 100 ng of E2 + 1 mg of P4 (C and F), and 16 h later, expression of E-cadherin in the uterus was examined. As expected, E-cadherin immunoreactivity was confined to the epithelial compartment. Its expression was markedly lower in vehicle-treated ERβ−/− than in WT mice (A and D). (Insets) Outlined areas at 4 times greater magnification. Treatment with E2 restored E-cadherin levels in ERβ−/− mice.

Hyperresponsiveness of ERβ−/− Uterus to Proliferative Effects of E2.

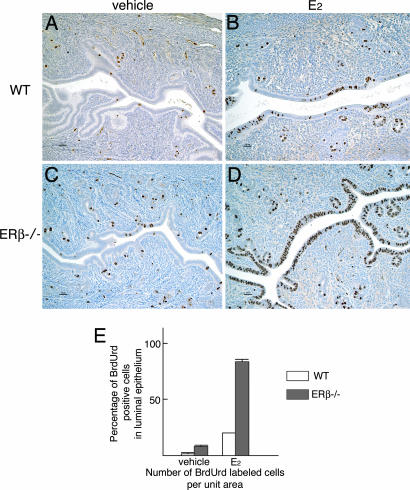

BrdUrd was injected 14 h after injection of E2. DNA synthesis in the epithelial cells in the uterus commences ≈6 h after E2 injection and peaks at 12 to 15 h (1, 10). E2 treatment of ovariectomized adult mice resulted in uterine luminal epithelial cell proliferation in both WT (Fig. 2A and B) and ERβ−/− (Fig. 2 C and D) littermates. No stromal BrdUrd-labeled cells were observed. Consistent with the earlier report (13), there were more BrdUrd-stained cells in the epithelium of ERβ−/− than in WT mice. After administration of E2, almost all of the luminal epithelial cells of ERβ−/− mice were BrdUrd-labeled (Fig. 2 D and E).

Fig. 2.

Detection of S-phase cells in uteri of WT and ERβ−/− littermates. Sixteen hours before being killed, mice received a single injection of vehicle (A and C) or 100 ng of E2 (B and D). Two hours before being killed, mice were injected i.p. with BrdUrd at 30 mg/kg. In vehicle-treated WT mice, 1.5% of epithelial cells were labeled, whereas 8% were labeled in ERβ−/− mice. After administration of E2, 23% of luminal epithelial cells were labeled in WT mice, and 82% were labeled in ERβ−/− mice (B, D, and E).

Differentiation of Cells in the Uterine Endometrium and Cervix in ERβ−/− and WT Littermates.

In the absence of ovarian hormones, expression of cytokeratin (CK) 18 in the luminal and glandular epithelium was similar in WT and ERβ−/− mice (Fig. 3A and D). Upon hormonal treatment, expression of CK18 in uteri showed a slight reduction in WT mice but was significantly decreased in ERβ−/− mice (Fig. 3 B and C and E and F, respectively). In contrast, expression of CK13, which is preferentially expressed in cells at the uterine cervix, was similar in WT and ERβ−/− mice, and hormonal treatment resulted in no remarkable changes as determined by using immunohistochemical staining (Fig. 3 G–L).

Fig. 3.

Immunohistochemical detection of CK18 (epithelial marker) and CK13 (uterine cervical marker) in the uteri of WT and ERβ−/− littermates. Mice received a single injection with vehicle (A, D, G, and J), 100 ng of E2 (B, E, H, and K), or 100 ng of E2 + 1 mg of P4 (C, F, I, and L). The differentiation marker CK18 is confined to luminal and glandular cells in the uteri of WT (A–C) and ERβ−/− mice (D–F). In vehicle-treated mice, CK18 expression was lower in ERβ−/− than in WT mice (A and D). Treatment with E2 or E2 + P4 resulted in reduction of CK18 expression in WT mice (B and C) but complete loss CK18 in ERβ−/− mice (E and F). Expression of CK13 in the uterine cervix was similar in WT (G–I) and ERβ−/− mice (J–L).

Colocalization of ERα and ERβ in Uterine Tissue.

Cellular localization of ERα and ERβ was studied in the uteri of WT mice treated with vehicle (Fig. 4A and D), E2 (Fig. 4 B and E), or E2 + P4 (Fig. 4 C and F). In Fig. 4, Cy3-conjugated anti-chicken IgG (red) detects ERβ, and FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (green) detects ERα. Cells in which ERα and ERβ are colocalized are stained yellow or orange (arrows). ERα was abundantly expressed in intact WT mice (Fig. 4M), but in vehicle-treated ovariectomized mice, ERβ (but not ERα) was expressed in the luminal epithelium (Fig. 4A). Both receptors were expressed in the stroma and glandular epithelium. In the glandular epithelium, the two receptors colocalized in the same nuclei, but in the stroma, they were in separate cells (Fig. 4 A and D). Upon E2 treatment, ERβ was lost from the luminal epithelium, whereas the two receptors were colocalized in nuclei of the stroma and glandular epithelium (Fig. 4 B and E). When mice were treated with E2 + P4, only ERα was detected in the glandular epithelium (Fig. 4F). In the stroma, many cells were ERα-positive, and a few were ERβ-positive, but the two receptors were not coexpressed in the same cells (Fig. 4C). Expression of ERα was studied in the uteri of WT and ERβ−/− mice treated with vehicle (Fig. 4 G and J), E2 (Fig. 4 H and K), or E2 + P4 (Fig. 4 I and L). Expression of ERα showed similar pattern in both genotypes but tended to be more intense in ERβ−/− mice. Surprisingly, after ovariectomy, ERα could not be detected in the luminal epithelium of either WT or ERβ−/− mice (Fig. 4 G–L).

Fig. 4.

Colocalization of ERα and ERβ in uteri of WT mice. In intact WT mice, ERα, as expected, was abundantly expressed in both epithelium and stroma (M). However, after ovariectomy, ERα could not be detected in the luminal epithelium of either WT or ERβ−/− mice (G–L). Ovariectomized mice received a single injection of vehicle (A, D, G, and J), 100 ng of E2 (B, E, H, and K), or 100 ng of E2 + 1 mg of P4 (C, F, I, and L). Colocalization of ERα (green) and ERβ (red) in the stroma was seldom seen in mice treated with vehicle or E2 + P4 (A–C) but was seen in mice treated with E2 alone. In the glandular epithelium (D–F) receptors were colocalized (yellow and arrows) in vehicle-treated (D) and E2-treated (E, arrows) mice. Upon administration of E2 + P4 (F), expression of ERβ was extinguished, whereas ERα expression remained.

PR as a Stromal Differentiation Marker in ERβ−/− and WT Littermates.

In vehicle-treated mice there was intense staining for PR in the majority of luminal and glandular epithelial cells in both WT and ERβ−/− mice. There was faint staining in the stromal and muscular compartments (Fig. 5A, D, and G). E2 and E2 + P4 treatment resulted in a significant increase in expression of PR in the stroma (Fig. 5 B, C, and E–G), with only a small difference in expression of PR between WT and ERβ−/− mice (Fig. 5G). The intensity of PR staining in the luminal epithelium was reduced by treatment with E2 or E2 + P4 in mice of both genotypes (Fig. 5 B, C, E, and F).

Fig. 5.

Immunohistochemical detection of PR. PR was abundant in the luminal and glandular epithelium of both WT and ERβ−/− mice. Stromal PR immunoreactivity was faint in vehicle-treated WT and ERβ−/− mice (A, D, and G). It was markedly induced in both WT and ERβ−/− mice by the administration of 100 ng of E2 (B, E, and G), or 100 ng of E2 + 1 mg of P4 (C, F, and G).

Stromal Expression of EGFR in ERβ−/− Mice.

EGFR is up-regulated by estrogens (23) and plays an important role in uterine and vaginal organ growth in response to estrogens (24). Immunohistochemical staining in uteri from ovariectomized mice revealed specific EGFR staining in the cytoplasm of luminal epithelium in WT mice and much weaker staining in ERβ−/− mice (Fig. 6A and D). E2 treatment enhanced cytoplasmic staining in epithelium of WT but resulted in patchy staining in the nuclei of epithelial cells in ERβ−/− mice (Fig. 6 B and E). Upon treating ERβ−/− mice with E2 + P4, there was a striking increase in nuclear staining of EGFR in the stromal cells (Fig. 6F). In WT mice, stromal nuclear staining was rarely detected (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Immunohistochemical analysis of EGFR protein expression. Mice received a single injection of vehicle (A and D), 100 ng of E2 (B and E), or 100 ng of E2 + 1 mg of P4 (C and F). In vehicle-treated mice, there was strong membrane EGFR immunoreactivity in the luminal epithelium of WT mice (A) but no membrane or cytoplasmic staining in ERβ−/− mice (D). E2 treatment resulted in enhanced EGFR expression in the cytoplasm of WT mice (B) and increased nuclear staining in ERβ−/− mice. In ERβ−/− mice treated with E2 + P4, there was a marked increase in nuclear localization of EGFR in the stroma (F), whereas in WT mice, this treatment resulted in nuclear localization of EGFR in the epithelium but not in the stroma. (Insets) Outlined areas at 3 times greater magnification.

Discussion

Our studies show that deficiency of ERβ leads to hyperproliferation and loss of differentiation in the uterine epithelium. This finding is similar to what has been observed in the ventral prostate (17) and colon (18). Thus, in the ventral prostate, colon, and uterus, ERβ seems to be essential for driving cellular differentiation.

Previous studies have shown aberrant expression of adhesion molecules in the mammary gland and colon of ERβ−/− mice. There is decreased expression of E-cadherin, connexin 32, occludin, and integrin α2 in mammary glands (15) and of α-catenin and plectin in the colon (18). These changes are accompanied by alterations in cytoarchitecture as revealed by EM (15, 18, 19). In the present study, the shape of the luminal epithelial cells was distorted in ERβ−/− mice. This distortion was most evident as a lack of straight lateral walls. This change in shape may be attributed to the decreased expression of E-cadherin and CK18 exhibited in ERβ−/− mice. E-cadherin is required at adherence junctions (25) and is essential for anchoring of epithelial cells. Loss of E-cadherin expression can disrupt these adherence junctional complexes and elicit phenotypic changes, including the acquisition of invasive growth (26). In addition to physical attachment, adhesion molecules transmit regulatory information through cytoplasmic adaptors (27) such as β-catenin, an adherence-junction protein that attaches to E-cadherin and EGFR (28). E-cadherin expression is estrogen-dependently regulated by ERα (29). The present data show that ERβ plays a regulatory role in E-cadherin expression. Although E-cadherin expression was reduced in the absence of ERβ, after administration of E2, E-cadherin expression levels returned to normal in ERβ−/− mice. Thus, both ERs are involved in expression of E-cadherin.

Tissue recombinant experiments have clearly shown that uterine stroma is necessary for the proliferative response of the epithelium to E2 (30). ERα-positive stroma behaves as an interpreter of the estrogen signal, translating it into a growth-stimulating message that is sent to the epithelium. Loss of growth control is a characteristic of ERβ−/− mouse uterus (13), bone marrow (16), ventral prostate (14, 17), and colon (18). The present study shows that in the uterine epithelium of ovariectomized ERβ−/− mice, both in the absence and in the presence of E2, there were markedly more cells in S phase of the cell cycle than in WT littermates. Several peptide growth factors whose expression is hormonally responsive have been identified in the uterus. These factors include EGF, insulin-like growth factor-I, TGF-α, and TGF-β. The present studies show that dysregulation of the EGF system may be part of the reason for the hyperproliferative response of the ERβ−/− uterus to E2. The role of the EGF family in estrogenic effects in the female genital tract is well documented (31). Estrogens have effects on both EGF and EGFR in the uterus (32, 33). The present study revealed that EGFR is found not only in association with the cell membrane but also in the cytoplasm and in nuclei of stromal cells in ERβ−/− mice treated with E2 + P4. As is already known, P4 induces proliferation of stromal cells and primes the uterus to respond to decidualizing stimuli (34–36). The nuclear localization of EGFR is of special interest. Recently, several studies have reported that growth factors and their receptors are not confined to the membrane compartment of cells (37–39). It has been suggested that nuclear EGFR is strongly correlated with highly proliferating activity (39) and that nuclear EGFR might function as a transcription factor to activate genes required for proliferation. Because the epithelial and stromal compartments communicate with each other through growth factors, the substantial expression of EGFR in stromal nuclei of ERβ−/− mice might be related to the enhanced proliferation of the epithelium.

The pattern of differentiation of the uterine epithelium in the absence of ERβ signaling was studied by immunohistochemical staining. In epithelial cells, CKs are intermediate filaments that determine cell shape. Over 20 distinct proteins constitute the CK family, which includes types I (CK9–CK20) and II (CK1–CK8). All epithelial cells express one or more type I and type II CKs. Changes in expression of CKs are seen during epithelial cell differentiation. CK18 is expressed in luminal and glandular epithelial cells of both human and rabbit endometrium at all developmental stages (40). CK13 exhibits stage-specific expression in the secretory-phase luminal epithelium of humans and the peri-implantation-stage endometrium of rabbits (40). We report here that CK18 is found in all luminal and glandular epithelial cells, and CK13 is found in the uterine cervix. After E2 treatment, there was a marked reduction in CK18 expression in epithelial cells of ovariectomized ERβ−/− but not WT mice. This reduction in CK18 may simply reflect that although most of the luminal epithelial cells are proliferating, very few are fully differentiated.

In uterine tissue, both ERα and ERβ are expressed. In uterine stroma, ERα and ERβ are colocalized in nuclei in E2-treated mice. We interpret this finding to indicate that as ERα mediates EGF secretion from the stroma, ERβ plays a modulatory role on ERα-mediated growth factor secretion. In the uterine glandular epithelium of WT mice there are very few cells where the two receptors are colocalized. In rodents, uterine secretory products of the endometrial glands are required for establishment of uterine receptivity and conceptus implantation. When ERβ is absent, uterine glands are hyperresponsive to E2, with exaggerated uterine secretion of proteins, including growth factors (13). ERα−/− mice have hypoplastic uteri that contain all characteristic cell types, but the number of uterine glands is reduced (41). We hypothesize that the adenogenesis and development of the uterine gland requires ERα, whereas ERβ mainly plays a role in differentiation.

Consistent with the studies in refs. 13 and 20, ERβ has a role in regulating PR expression in the rodent uterus. The 5′ region of the PR gene contains clusters of estrogen-responsive element half-sites that are essential for trans-activation of the PR gene by liganded ER. However, the mouse PR gene is not a typical estrogen-responsive element-regulated gene, and its 5′ region contains many other putative binding sites for other regulatory transcription factors. Because administration of E2 decreases PR in the uterine epithelium of immature WT mice but increases PR in ERβ−/− mice, it has been suggested that the induction of PR is an ERα-mediated event, whereas repression of epithelial PR is ERβ-mediated (13). This study shows that ERβ is not required for an E2-induced decrease of uterine epithelial PR in adult mice. Interestingly, the E2 induction of stromal PR in ERα−/− mice suggests that ERβ might be responsible for stromal PR induction.

When ERβ−/− mice are treated with E2 + P4, there is strong stimulation of growth in the stroma. Hom et al. (24) found that EGFR is required for the stromal response to estrogen. The hyperproliferation of the epithelium of ERβ−/− mice after ovariectomy suggests that when E2 and ERβ are absent, there is growth-factor-induced proliferation of the uterus. Thus, loss of ERβ predisposes the uterus to aberrant endometrial proliferation. In view of the increased risk for endometrial cancer that accompanies estrogen treatment of postmenopausal women, we suggest that these women should be routinely checked for expression of ERβ in the endometrium. Loss of ERβ would identify women who are at higher risk for proliferative diseases of the endometrium.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

WT and ERβ−/− mice were bred from heterozygous mice. Genotyping by using PCR was performed on DNA isolated from tails of 2-week-old mice as described in ref. 12. Mice were fed a soy-free standard chow diet (Special Diet Services, Whitham, Essex, U.K.) and tap water ad libitum. All animals were housed in Huddinge University Hospital Animal Facility under controlled lightning (12-h light, 12-h dark cycle), temperature (21–22°C), and relative humidity (50%) conditions. Animals were maintained in accordance with the Södra Djurförsöksetiska Nämnd Guidelines for Care and Use of Experimental Animals.

Hormone Treatments.

Twelve WT and ERβ−/− mice were ovariectomized at 8 weeks of age. Seven days after surgery, mice were injected once s.c. with 150 μl of olive oil containing no hormone, 100 ng of E2, or 100 ng of E2 + 1 mg of P4. Mice were killed by cervical dislocation 16 h after the injection, and the uteri were isolated.

Chemicals and Antibodies.

BrdUrd was purchased from Roche Diagnositcs (Mannheim, Germany). E2 and P4 were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Chicken polyclonal antibody anti-ERβ 503 IgY was produced in our laboratory (18). Rabbit antibodies were anti-ERα (catalog no. sc-542; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-PR (catalog no. A0098; DAKO, Carpinteria, CA), and anti-CK18 (catalog no. 10830-1-AP; Protein Tech Group, Chicago, IL). Goat polyclonal antibody anti-EGFR was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (catalog no. sc-03-G). Mouse monoclonal antibodies were anti-BrdUrd (catalog no. 3D4; BD Biosciences PharMingen, San Jose, CA) and anti-CK13 (catalog no. ab16112; Abcam, Cambridge, U.K.). Biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG, anti-mouse IgG, horse anti-goat IgG, and avidin-biotin complex kits were from Vector Laboratories (Peterborough, U.K.). Cy-3-conjugated donkey anti-chicken IgG (catalog no. 703-165-155) and FITC-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit (catalog no. 711-095-152) were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA).

Treatment with BrdUrd.

For measurement of proliferation, mice were treated i.p. with BrdUrd at 30 mg/kg 2 h before being killed.

Immunohistochemistry.

For immunohistochemical studies, uteri were removed and fixed flat on wet filter papers overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde. They were routinely embedded in paraffin wax, and 4-μm sections were mounted on organosilane-coated slides. Four-micrometer paraffin sections were dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated through graded ethanol to water. Antigens were retrieved by boiling in a 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 20 min except for the immunostaining of EGFR. The cooled sections were incubated in methanol containing 0.3% H2O2 for 30 min to quench endogenous peroxidase. To block the nonspecific binding, sections were incubated in PBS containing 3% BSA and 0.1% Nonidet P-40 for 10 min at room temperature. Sections were then incubated with the antisera anti-BrdUrd (1:800), anti-CK13 (1:200), anti-CK18 (1:200), anti-PR (1:100), anti-EGFR (1:50), and anti-E-cadherin (1:200) in PBS containing 3% BSA and 0.1% Nonidet P-40 overnight at 4°C. Negative controls were incubated with PBS containing 3% BSA and 0.1% Nonidet P-40 without a primary antibody. The avidin–biotin complex method was used to visualize the signal, according to the manufacturer's manual (Vector Laboratories). The sections were incubated in appropriate biotinylated IgG solution (1:200) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by washing with PBS and incubation in avidin-biotin-horseradish peroxidase for 1 h. After washing in PBS, sections were developed with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride substrate (DAKO) for 1–3 min, producing a brown stain. The sections were lightly counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin, dehydrated through a graded ethanol series and xylene, and mounted.

Immunofluorescence Labeling of ERα and ERβ.

ERα and ERβ were detected in tissue sections by standard immunofluorescence as described in ref. 42. For immunofluorescent detection, 4-μm paraffin sections were dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated through graded ethanol to water. Antigens were retrieved by boiling in a 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) in a microwave oven for 20 min. Sections were incubated with PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 for 30 min, then with PBS containing 3% BSA for 15 min. For double staining of ERα/ERβ, sections were incubated sequentially with anti-ERα (1:200) and anti-ERβ (1:100) in PBS containing 3% BSA and 0.1% Nonidet P-40 overnight at 4°C. Negative controls were incubated with PBS containing 3% BSA and 0.1% Nonidet P-40 without a primary antibody. The secondary antibodies were Cy-3-conjugated anti-chicken IgG (1:200), and FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:200). After incubation for 1 h, the sections were washed and dipped in DAPI solution (0.1 μg/ml in PBS) for 20 sec at room temperature to delineate nuclei and mounted in Vectashield antifading medium (Vector Laboratories). The sections were examined under a Zeiss (Göttingen, Germany) Axioplan 2 fluorescence microscope by using suitable filters for selectively detecting the fluorescence of FITC (green) and Cy3 (red). Colocalization was indicated by yellow or orange in cells in which both FITC- and Cy3-conjugated secondary antibodies were sequestered.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jose Inzunza and AnnMarie Witte for managing ERβ−/− mice. This study was supported by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture, Japan, JMS Schering, the Japan Menopausal Society, Japan (to O.W.-H.), the European Union CASCADE Network of Excellence, the Swedish Cancer Fund, Konung Gustav V och Drottning Victorias Stiftelse, and Karo Bio AB.

Abbreviations

- CK

cytokeratin

- E2

17β-estradiol

- ER

estrogen receptor

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- P4

progesterone

- PR

progesterone receptor.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: J.-Å.G. is a cofounder, consultant, deputy board member, and shareholder of Karo Bio AB.

References

- 1.Martin L, Finn CA, Trinder G. J Endocrinol. 1973;56:133–144. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0560133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quarmby VE, Korach KS. Endocrinology. 1984;114:694–702. doi: 10.1210/endo-114-3-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kachkache M, Acker GM, Chaouat G, Noun A, Garabedian M. Biol Reprod. 1991;45:860–868. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod45.6.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De M, Wood GW. J Endocrinol. 1990;126:417–424. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1260417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin L, Das RM, Finn CA. J Endocrinol. 1973;57:549–554. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0570549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Persson I. Maturitas. 1996;23(Suppl):S37–S45. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(96)01010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen CJ, Bruckner HW, Deppe G, Blessing JA, Homesley H, Lee JH, Watring W. Obstet Gynecol. 1984;63:719–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henderson BE, Ross RK, Pike MC. Science. 1993;259:633–638. doi: 10.1126/science.8381558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paech K, Webb P, Kuiper GGJM, Nilsson S, Gustafsson J-Å, Kushner PJ, Scanlan TS. Science. 1997;277:1508–1510. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin L, Pollard JW, Fagg B. J Endocrinol. 1976;69:103–115. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0690103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Couse JF, Lindzey J, Grandien K, Gustafsson J-Å, Korach KS. Endocrinology. 1997;138:4613–4621. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.11.5496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krege JH, Hodgin JB, Couse JF, Enmark E, Warner M, Mahler JF, Sar M, Korach KS, Gustafsson J-Å, Smithies O. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15677–15682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weihua Z, Saji S, Makinen S, Cheng G, Jensen EV, Warner M, Gustafsson J-Å. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5936–5941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.11.5936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weihua Z, Makela S, Andersson LC, Salmi S, Saji S, Webster JI, Jensen EV, Nilsson S, Warner M, Gustafsson J-Å. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6330–6335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111150898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forster C, Makela S, Warri A, Kietz S, Becker D, Hultenby K, Warner M, Gustafsson J-Å. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15578–15583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192561299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shim GJ, Wang L, Andersson S, Nagy N, Kis LL, Zhang Q, Makela S, Warner M, Gustafsson J-Å. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:6694–6699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0731830100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imamov O, Morani A, Shim GJ, Omoto Y, Thulin-Andersson C, Warner M, Gustafsson J-Å. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:9375–9380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403041101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wada-Hiraike O, Imamov O, Hiraike H, Hultenby K, Schwend T, Omoto Y, Warner M, Gustafsson J-Å. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2959–2964. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511271103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morani A, Barros RPA, Imamov O, Hultenby K, Arner A, Warner M, Gustafsson J-Å. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7165–7169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602194103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurita T, Lee K, Saunders PT, Cooke PS, Taylor JA, Lubahn DB, Zhao C, Makela S, Gustafsson J-Å, Dahiya R, Cunha GR. Biol Reprod. 2001;64:272–283. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod64.1.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tessier C, Deb S, Prigent-Tessier A, Ferguson-Gottschall S, Gibori GB, Shiu RP, Gibori G. Endocrinology. 2000;141:3842–3851. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.10.7734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu JJ, Geimonen E, Andersen J. Eur J Endocrinol. 2000;142:92–99. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1420092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Das SK, Tsukamura H, Paria BC, Andrews GK, Dey SK. Endocrinology. 1994;134:971–981. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.2.7507841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hom YK, Young P, Wiesen JF, Miettinen PJ, Derynck R, Werb Z, Cunha GR. Endocrinology. 1998;139:913–921. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.3.5817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams CL, Nelson WJ. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:572–577. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Behrens J, Mareel MM, Van Roy FM, Birchmeier W. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:2435–2447. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.6.2435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thiery JP. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:442–454. doi: 10.1038/nrc822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoschuetzky H, Aberle H, Kemler R. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:1375–1380. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.5.1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fujita N, Jaye DL, Kajita M, Geigerman C, Moreno CS, Wade PA. Cell. 2003;113:207–219. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00234-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cooke PS, Buchanan DL, Young P, Setiawan T, Brody J, Korach KS, Taylor J, Lubahn DB, Cunha GR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6535–6540. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mukku VR, Stancel GM. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:9820–9824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DiAugustine RP, Petrusz P, Bell GI, Brown CF, Korach KS, McLachlan JA, Teng CT. Endocrinology. 1988;122:2355–2363. doi: 10.1210/endo-122-6-2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sakai Y, Nelson KG, Snedeker S, Bossert NL, Walker MP, McLachlan J, DiAugustine RP. Cell Growth Differ. 1994;5:527–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Finn CA, Martin L. J Endocrinol. 1970;47:431–438. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0470431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lydon JP, DeMayo FJ, Funk CR, Mani SK, Hughes AR, Montgomery CA, Jr, Shyamala G, Conneely OM, O'Malley BW. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2266–2278. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.18.2266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lydon JP, DeMayo FJ, Conneely OM, O'Malley BW. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;56:67–77. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(95)00254-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Podlecki DA, Smith RM, Kao M, Tsai P, Huecksteadt T, Brandenburg D, Lasher RS, Jarett L, Olefsky JM. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:3362–3368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Antoine M, Reimers K, Dickson C, Kiefer P. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:29475–29481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.47.29475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marti U, Ruchti C, Kampf J, Thomas GA, Williams ED, Peter HJ, Gerber H, Burgi U. Thyroid. 2001;11:137–145. doi: 10.1089/105072501300042785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olson GE, Winfrey VP, Blaeuer GL, Palisano JR, NagDas SK. Biol Reprod. 2002;66:1006–1015. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod66.4.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Curtis SW, Clark J, Myers P, Korach KS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3646–3651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barros RPA, Machado UF, Warner M, Gustafsson J-Å. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1605–1608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510391103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]