Abstract

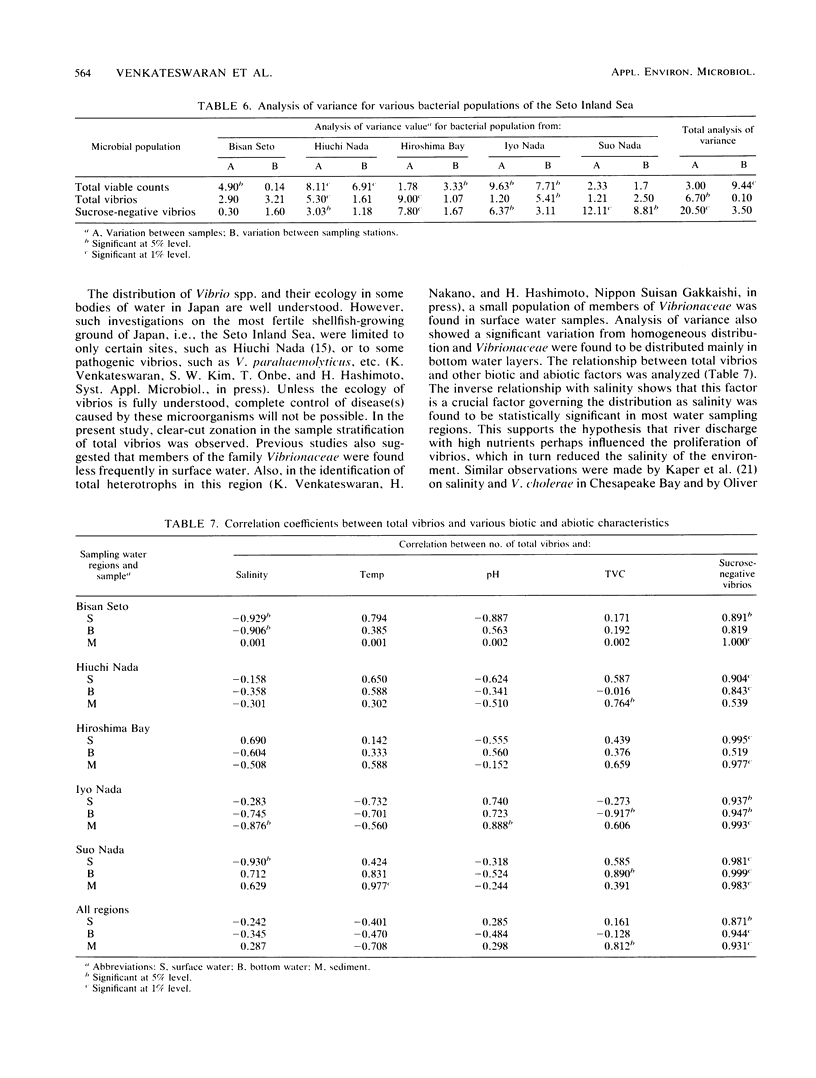

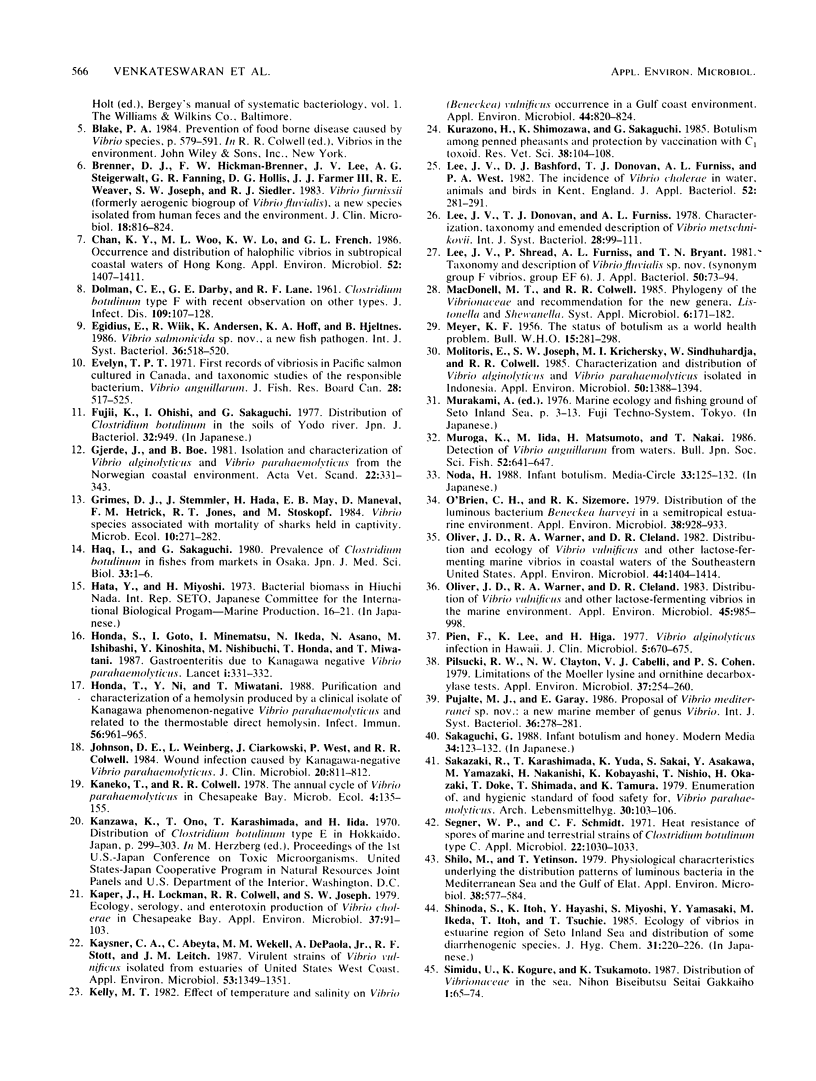

The distribution of Vibrio species in samples of surface water, bottom water (water 2 m above the sediment), and sediment from the Seto Inland Sea was studied. A simple technique using a membrane filter and short preenrichment in alkaline peptone water was developed to resuscitate the injured cells, followed by plating them onto TCBS agar. In addition, a survey was conducted to determine the incidence of Clostridium botulinum in sediment samples. Large populations of heterotrophs were found in surface water, whereas large numbers of total vibrios were found in bottom water. In samples from various water sampling regions, high counts of all bacterial populations were found in the inner regions having little exchange of seawater when compared with those of the open region of the inland sea. In the identification of 463 isolates, 23 Vibrio spp. and 2 Listonella spp. were observed. V. harveyi was prevalent among the members of the Vibrio genus. Vibrio species were categorized into six groups; an estimated 20% of these species were in the so-called "pathogenic to humans" group. In addition, a significant proportion of this group was hemolytic and found in the Bisan Seto region. V. vulnificus, V. fluvialis, and V. cholerae non-O1 predominated in the constricted area of the inland sea, which is eutrophic as a result of riverine influence. It was concluded that salinity indirectly governs the distribution of total vibrios and analysis of variance revealed that all bacterial populations were distributed homogeneously and the variance values were found to be significant in some water sampling regions.(ABSTRACT TRUNCATED AT 250 WORDS)

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Brenner D. J., Hickman-Brenner F. W., Lee J. V., Steigerwalt A. G., Fanning G. R., Hollis D. G., Farmer J. J., 3rd, Weaver R. E., Joseph S. W., Seidler R. J. Vibrio furnissii (formerly aerogenic biogroup of Vibrio fluvialis), a new species isolated from human feces and the environment. J Clin Microbiol. 1983 Oct;18(4):816–824. doi: 10.1128/jcm.18.4.816-824.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan K. Y., Woo M. L., Lo K. W., French G. L. Occurrence and distribution of halophilic vibrios in subtropical coastal waters of Hong Kong. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986 Dec;52(6):1407–1411. doi: 10.1128/aem.52.6.1407-1411.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjerde J., Böe B. Isolation and characterization of Vibrio alginolyticus and Vibrio parahaemolyticus from the Norwegian coastal environment. Acta Vet Scand. 1981;22(3-4):331–343. doi: 10.1186/BF03548658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haq I., Sakaguchi G. Prevalence of Clostridium botulinum in fishes from markets in Osaka. Jpn J Med Sci Biol. 1980 Feb;33(1):1–6. doi: 10.7883/yoken1952.33.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda T., Ni Y. X., Miwatani T. Purification and characterization of a hemolysin produced by a clinical isolate of Kanagawa phenomenon-negative Vibrio parahaemolyticus and related to the thermostable direct hemolysin. Infect Immun. 1988 Apr;56(4):961–965. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.4.961-965.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hondo S., Goto I., Minematsu I., Ikeda N., Asano N., Ishibashi M., Kinoshita Y., Nishibuchi N., Honda T., Miwatani T. Gastroenteritis due to Kanagawa negative Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Lancet. 1987 Feb 7;1(8528):331–332. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)92062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D. E., Weinberg L., Ciarkowski J., West P., Colwell R. R. Wound infection caused by Kanagawa-negative Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J Clin Microbiol. 1984 Oct;20(4):811–812. doi: 10.1128/jcm.20.4.811-812.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaper J., Lockman H., Colwell R. R., Joseph S. W. Ecology, serology, and enterotoxin production of Vibrio cholerae in Chesapeake Bay. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1979 Jan;37(1):91–103. doi: 10.1128/aem.37.1.91-103.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaysner C. A., Abeyta C., Jr, Wekell M. M., DePaola A., Jr, Stott R. F., Leitch J. M. Virulent strains of Vibrio vulnificus isolated from estuaries of the United States West Coast. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987 Jun;53(6):1349–1351. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.6.1349-1351.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly M. T. Effect of temperature and salinity on Vibrio (Beneckea) vulnificus occurrence in a Gulf Coast environment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982 Oct;44(4):820–824. doi: 10.1128/aem.44.4.820-824.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurazono H., Shimozawa K., Sakaguchi G., Takahashi M., Shimizu T., Kondo H. Botulism among penned pheasants and protection by vaccination with C1 toxoid. Res Vet Sci. 1985 Jan;38(1):104–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. V., Bashford D. J., Donovan T. J., Furniss A. L., West P. A. The incidence of Vibrio cholerae in water, animals and birds in Kent, England. J Appl Bacteriol. 1982 Apr;52(2):281–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1982.tb04852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. V., Shread P., Furniss A. L., Bryant T. N. Taxonomy and description of Vibrio fluvialis sp. nov. (synonym group F vibrios, group EF6). J Appl Bacteriol. 1981 Feb;50(1):73–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1981.tb00873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEYER K. F. The status of botulism as a world health problem. Bull World Health Organ. 1956;15(1-2):281–298. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molitoris E., Joseph S. W., Krichevsky M. I., Sindhuhardja W., Colwell R. R. Characterization and distribution of Vibrio alginolyticus and Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated in Indonesia. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985 Dec;50(6):1388–1394. doi: 10.1128/aem.50.6.1388-1394.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda H., Sugita K., Koike A., Nasu T., Takahashi M., Shimizu T., Ooi K., Sakaguchi G. Infant botulism in Asia. Am J Dis Child. 1988 Feb;142(2):125–126. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1988.02150020019012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'brien C. H., Sizemore R. K. Distribution of the Luminous Bacterium Beneckea harveyi in a Semitropical Estuarine Environment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1979 Nov;38(5):928–933. doi: 10.1128/aem.38.5.928-933.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver J. D., Warner R. A., Cleland D. R. Distribution and ecology of Vibrio vulnificus and other lactose-fermenting marine vibrios in coastal waters of the southeastern United States. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982 Dec;44(6):1404–1414. doi: 10.1128/aem.44.6.1404-1414.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver J. D., Warner R. A., Cleland D. R. Distribution of Vibrio vulnificus and other lactose-fermenting vibrios in the marine environment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983 Mar;45(3):985–998. doi: 10.1128/aem.45.3.985-998.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pien F., Lee K., Higa H. Vibrio alginolyticus infections in Hawaii. J Clin Microbiol. 1977 Jun;5(6):670–672. doi: 10.1128/jcm.5.6.670-672.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilsucki R. W., Clayton N. W., Cabelli V. J., Cohen P. S. Limitations of the Moeller lysine and ornithine decarboxylase tests. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1979 Feb;37(2):254–260. doi: 10.1128/aem.37.2.254-260.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segner W. P., Schmidt C. F. Heat resistance of spores of marine and terrestrial strains of Clostridium botulinum type C. Appl Microbiol. 1971 Dec;22(6):1030–1033. doi: 10.1128/am.22.6.1030-1033.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shilo M., Yetinson T. Physiological characteristics underlying the distribution patterns of luminous bacteria in the mediterranean sea and the gulf of elat. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1979 Oct;38(4):577–584. doi: 10.1128/aem.38.4.577-584.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simidu U., Tsukamoto K. Habitat segregation and biochemical activities of marine members of the family vibrionaceae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985 Oct;50(4):781–790. doi: 10.1128/aem.50.4.781-790.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith H. L., Jr, Bhat-Fernandes P. Modified decarboxylase-dihydrolase medium. Appl Microbiol. 1973 Oct;26(4):620–621. doi: 10.1128/am.26.4.620-621.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith L. D. The occurrence of Clostridium botulinum and Clostridium tetani in the soil of the United States. Health Lab Sci. 1978 Apr;15(2):74–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward B. Q., Carroll B. J., Garrett E. S., Reese G. B. Survey of the U.S. Gulf Coast for the presence of Clostridium botulinum. Appl Microbiol. 1967 May;15(3):629–636. doi: 10.1128/am.15.3.629-636.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]