Abstract

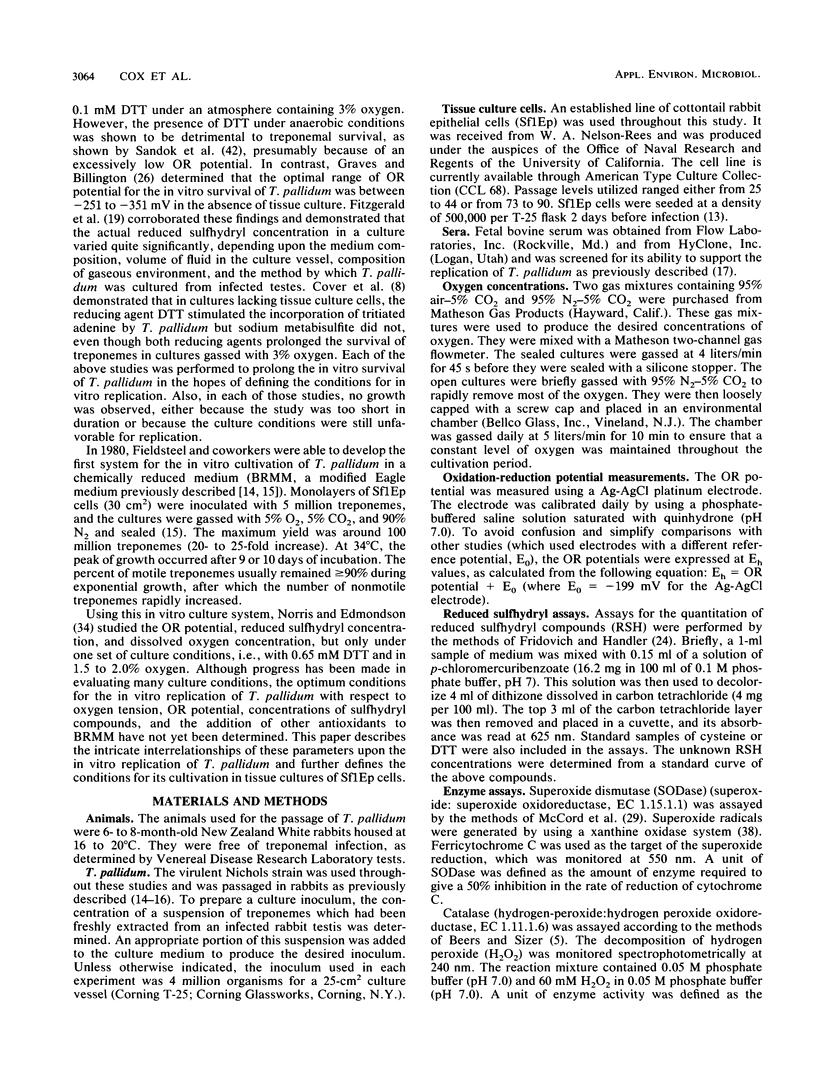

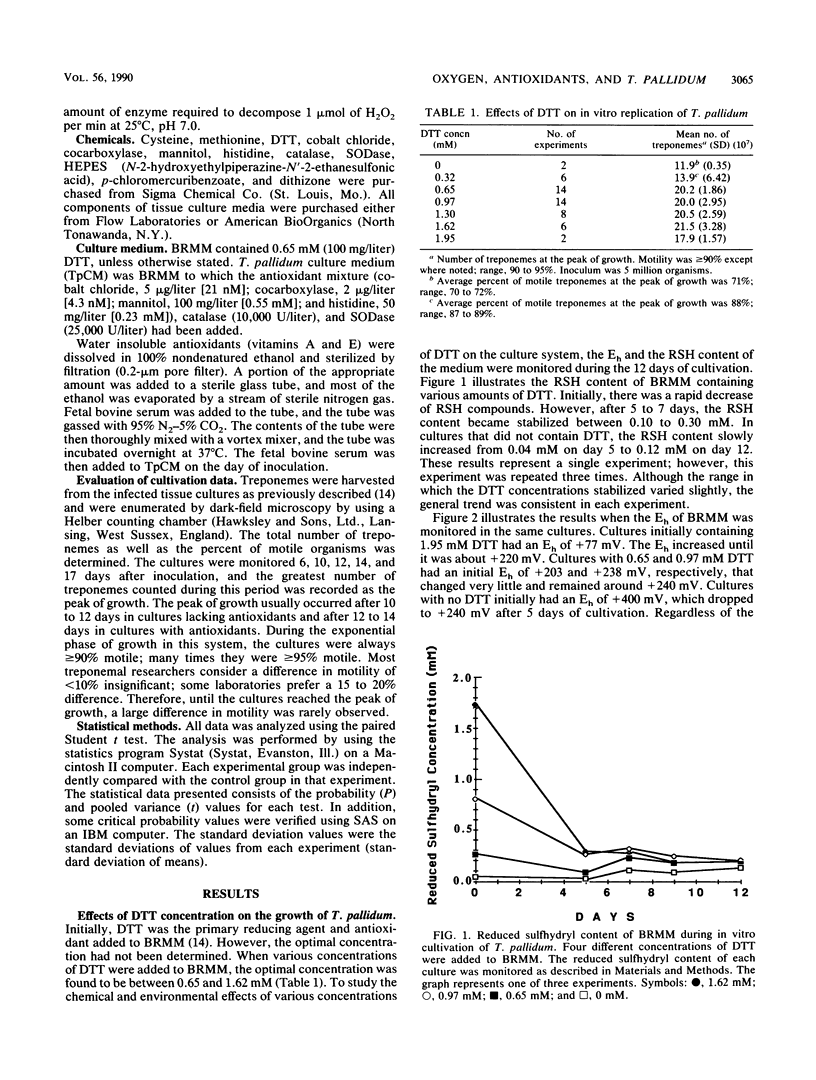

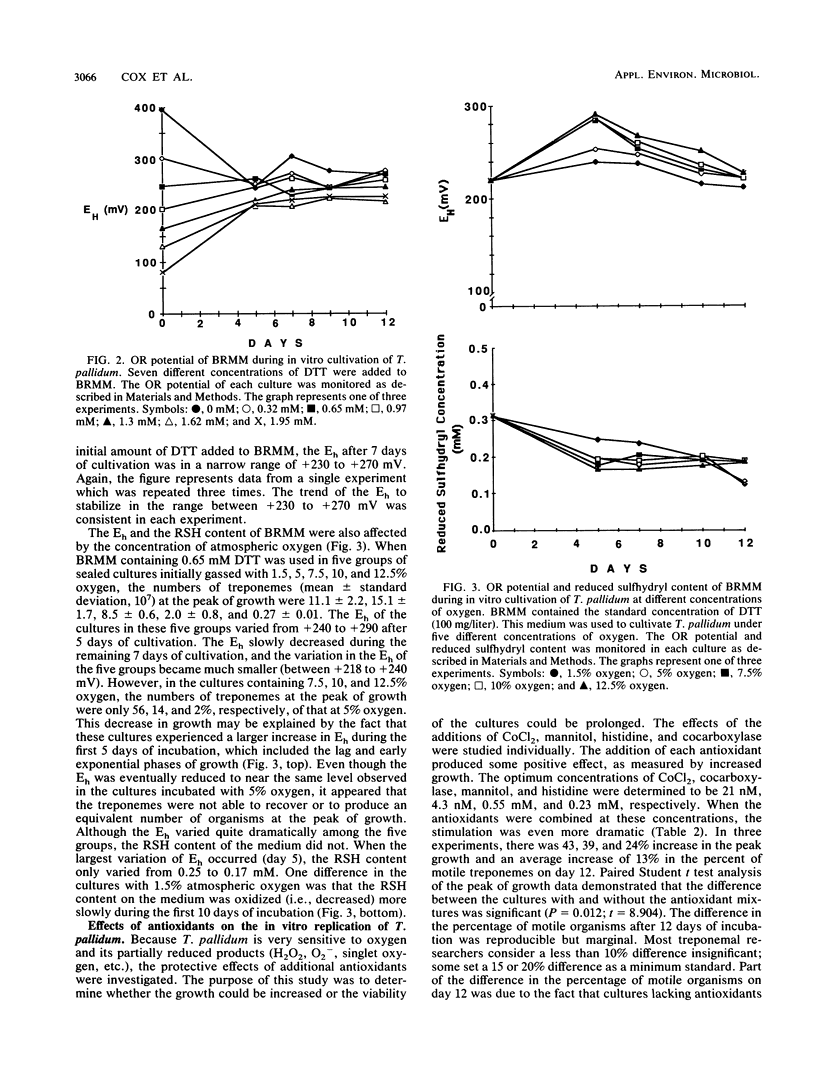

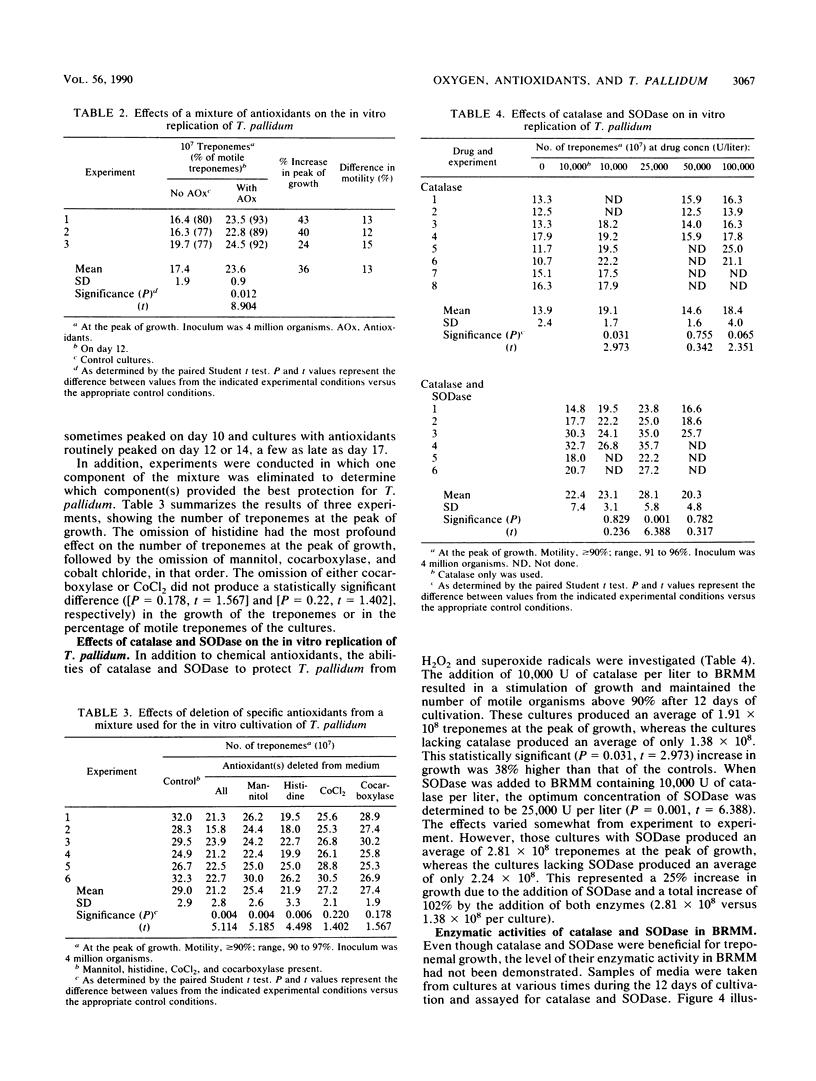

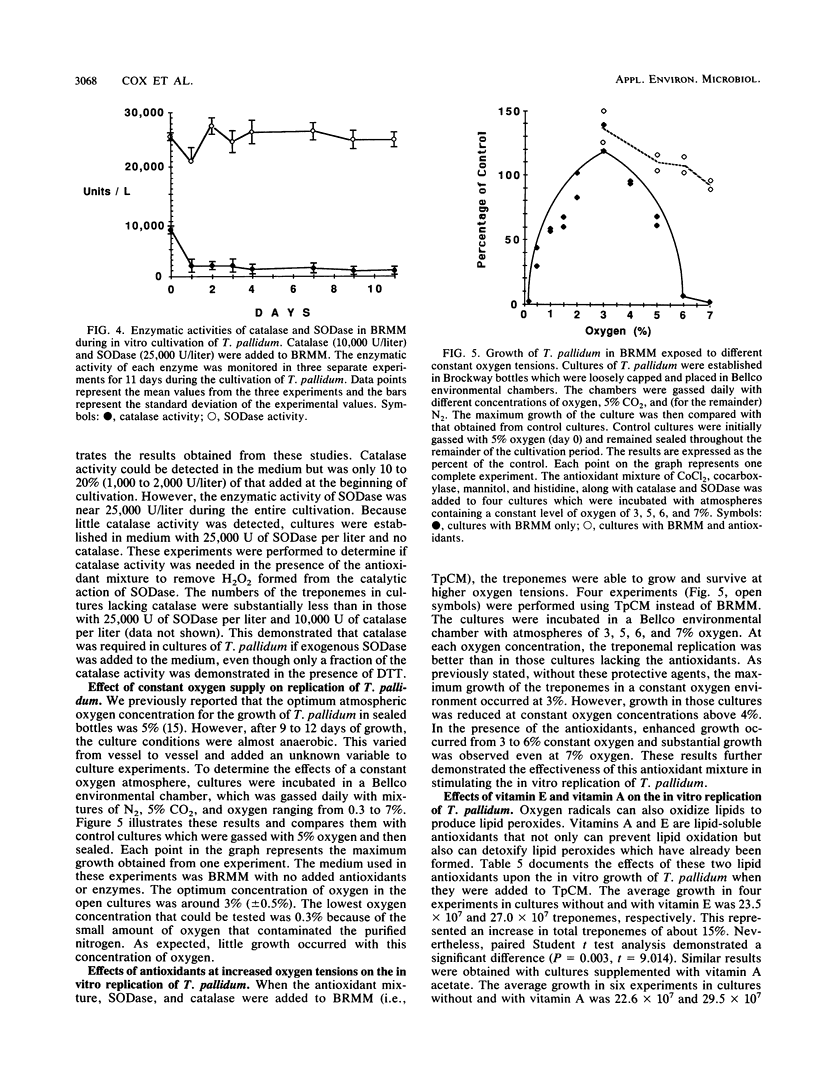

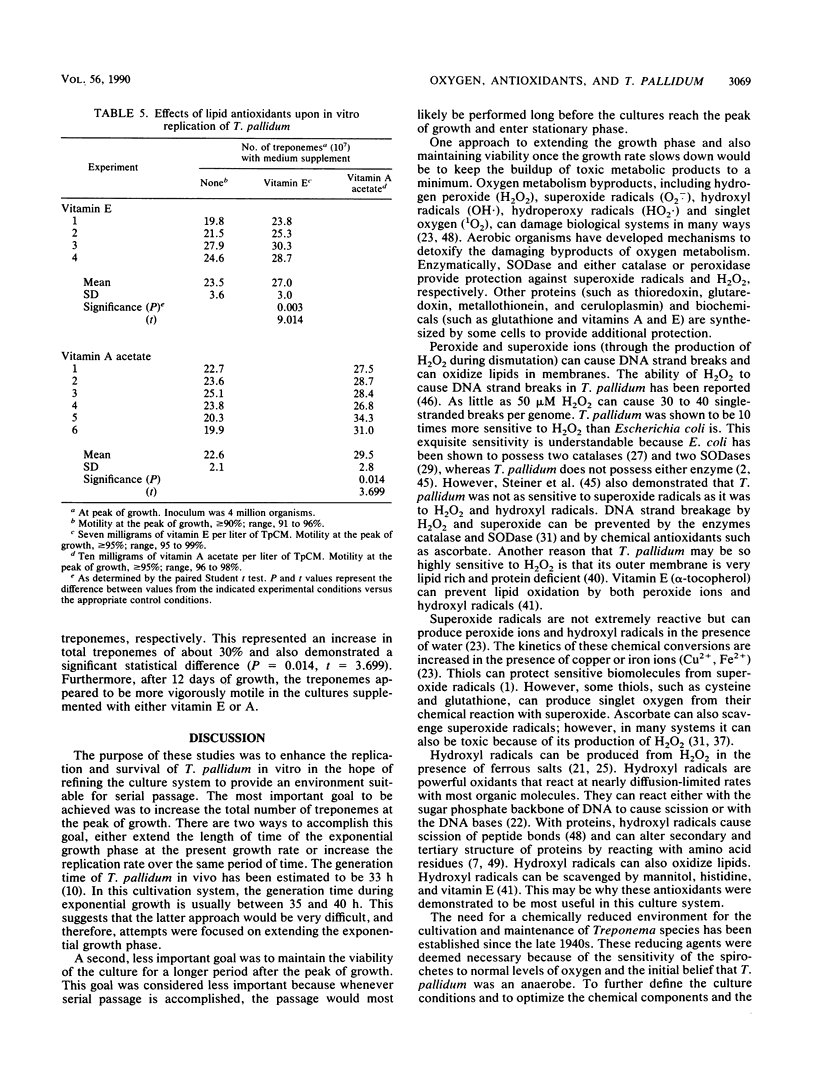

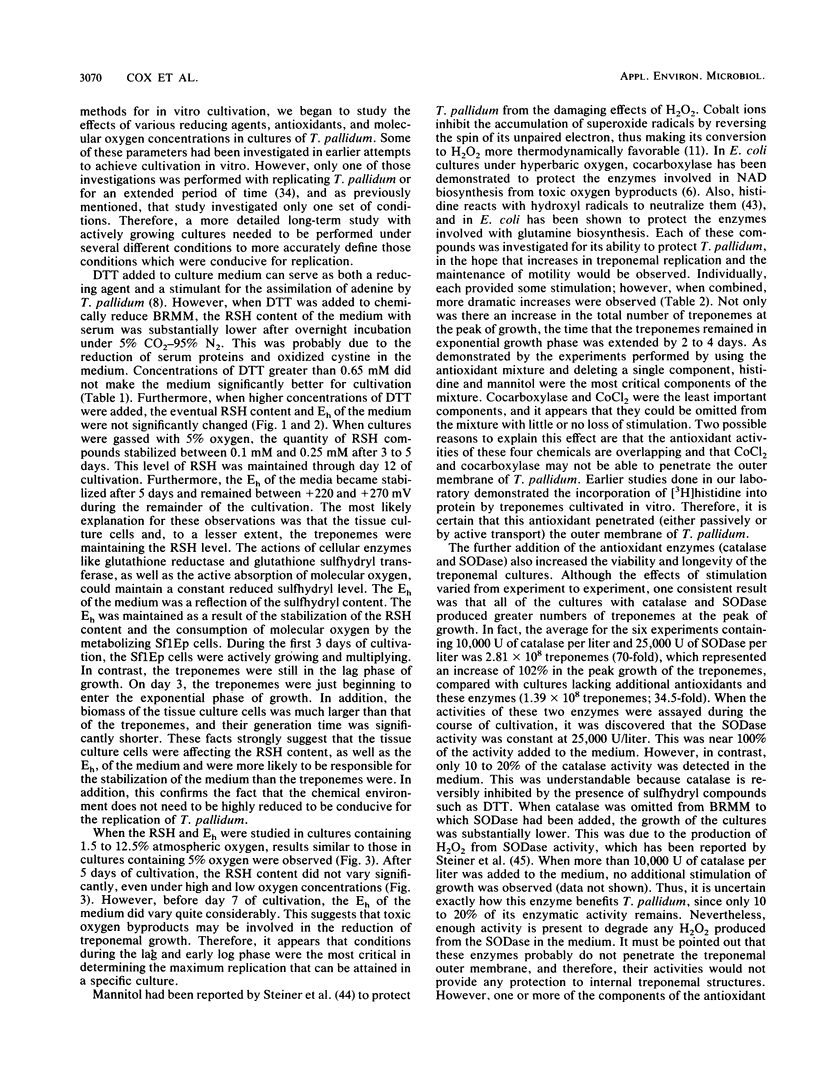

The effects of various concentrations of dithiothreitol, molecular oxygen, and several antioxidants upon the in vitro replication of Treponema pallidum were studied. The optimal dithiothreitol concentration was between 0.65 and 1.62 mM, and the optimum oxygen concentration was 3.0% +/- 0.5% in both the presence and absence of additional antioxidants. It was discovered that the reduced sulfhydryl concentration and the oxidation-reduction potential of the medium were stabilized after 5 days. The water-soluble antioxidants cobalt chloride, cocarboxylase, mannitol, and histidine were individually tested for their ability to increase treponemal growth in vitro. The optimum concentrations for these antioxidants were 21 nM, 4.3 nM, 0.55 mM, and 0.23 mM, respectively. When combined at these concentrations, the mixture of antioxidants stimulated the in vitro replication of T. pallidum. The number of treponemes in cultures with the antioxidants averaged a 59-fold increase, compared with a 43-fold increase in cultures lacking the antioxidants. It was further demonstrated that histidine and mannitol were the most critical components of this mixture. Catalase and superoxide dismutase were investigated for their ability to promote the growth and maintain viability of T. pallidum in tissue culture. The optimum concentrations for these enzymes were 10,000 U/liter and 25,000 U/liter, respectively. When these enzymes and the above antioxidants were combined and added to a chemically reduced modified Eagle medium, the treponemes increased an average of 70-fold, compared with an average of 35-fold in cultures lacking them. Furthermore, this medium, T. pallidum culture medium, supported the replication of T. pallidum at oxygen concentrations from 5 to 7% with little loss in yield or viability. The lipid-soluble antioxidants vitamin A and vitamin E acetate were also shown to enhance the in vitro growth of T. pallidum in this medium.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Austin F. E., Barbieri J. T., Corin R. E., Grigas K. E., Cox C. D. Distribution of superoxide dismutase, catalase, and peroxidase activities among Treponema pallidum and other spirochetes. Infect Immun. 1981 Aug;33(2):372–379. doi: 10.1128/iai.33.2.372-379.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEERS R. F., Jr, SIZER I. W. A spectrophotometric method for measuring the breakdown of hydrogen peroxide by catalase. J Biol Chem. 1952 Mar;195(1):133–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baseman J. B., Hayes N. S. Protein synthesis by Treponema pallidum extracted from infected rabbit tissue. Infect Immun. 1974 Dec;10(6):1350–1355. doi: 10.1128/iai.10.6.1350-1355.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baseman J. B., Nichols J. C., Mogerley S. Capacity of virulent Treponema pallidum (Nichols) for deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis. Infect Immun. 1979 Feb;23(2):392–397. doi: 10.1128/iai.23.2.392-397.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown O., Yein F., Boehme D., Foudin L., Song C. S. Oxygen poisoning of NAD biosynthesis: a proposed site of cellular oxygen toxicity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1979 Dec 14;91(3):982–990. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(79)91976-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper B., Creeth J. M., Donald A. S. Studies of the limited degradation of mucus glycoproteins. The mechanism of the peroxide reaction. Biochem J. 1985 Jun 15;228(3):615–626. doi: 10.1042/bj2280615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cover W. H., Norris S. J., Miller J. N. The microaerophilic nature of Treponema pallidum: enhanced survival and incorporation of tritiated adenine under microaerobic conditions in the presence or absence of reducing compounds. Sex Transm Dis. 1982 Jan-Mar;9(1):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox C. D., Barber M. K. Oxygen uptake by Treponema pallidum. Infect Immun. 1974 Jul;10(1):123–127. doi: 10.1128/iai.10.1.123-127.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEDIC G. A., KOCH O. G. Aerobic cultivation of Clostridium tetani in the presence of cobalt. J Bacteriol. 1956 Jan;71(1):126–126. doi: 10.1128/jb.71.1.126-126.1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagle H., Steinman H. G. The Nutritional Requirements of Treponemata: I. Arginine, Acetic Acid, Sulfur-containing Compounds, and Serum Albumin as Essential Growth-promoting Factors for the Reiter Treponeme. J Bacteriol. 1948 Aug;56(2):163–176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fieldsteel A. H., Becker F. A., Stout J. G. Prolonged survival of virulent Treponema pallidum (Nichols strain) in cell-free and tissue culture systems. Infect Immun. 1977 Oct;18(1):173–182. doi: 10.1128/iai.18.1.173-182.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fieldsteel A. H., Cox D. L., Moeckli R. A. Cultivation of virulent Treponema pallidum in tissue culture. Infect Immun. 1981 May;32(2):908–915. doi: 10.1128/iai.32.2.908-915.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fieldsteel A. H., Cox D. L., Moeckli R. A. Further studies on replication of virulent Treponema pallidum in tissue cultures of Sf1Ep cells. Infect Immun. 1982 Feb;35(2):449–455. doi: 10.1128/iai.35.2.449-455.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fieldsteel A. H., Stout J. G., Becker F. A. Comparative behavior of virulent strains of Treponema pallidum and Treponema pertenue in gradient cultures of various mammalian cells. Infect Immun. 1979 May;24(2):337–345. doi: 10.1128/iai.24.2.337-345.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fieldsteel A. H., Stout J. G., Becker F. A. Role of serum in survival of Treponema pallidum in tissue culture. In Vitro. 1981 Jan;17(1):28–32. doi: 10.1007/BF02618027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald T. J., Johnson R. C., Sykes J. A., Miller J. N. Interaction of Treponema pallidum (Nichols strain) with cultured mammalian cells: effects of oxygen, reducing agents, serum supplements, and different cell types. Infect Immun. 1977 Feb;15(2):444–452. doi: 10.1128/iai.15.2.444-452.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald T. J., Johnson R. C., Wolff E. T. Sulfhydryl oxidation using procedures and experimental conditions commonly used for Treponema pallidum. Br J Vener Dis. 1980 Jun;56(3):129–136. doi: 10.1136/sti.56.3.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald T. J., Miller J. N., Sykes J. A. Treponema pallidum (Nichols strain) in tissue cultures: cellular attachment, entry, and survival. Infect Immun. 1975 May;11(5):1133–1140. doi: 10.1128/iai.11.5.1133-1140.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd R. A. Direct demonstration that ferrous ion complexes of di- and triphosphate nucleotides catalyze hydroxyl free radical formation from hydrogen peroxide. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1983 Aug;225(1):263–270. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(83)90029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman B. A., Crapo J. D. Biology of disease: free radicals and tissue injury. Lab Invest. 1982 Nov;47(5):412–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridovich I. The biology of oxygen radicals. Science. 1978 Sep 8;201(4359):875–880. doi: 10.1126/science.210504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf E., Mahoney J. R., Bryant R. G., Eaton J. W. Iron-catalyzed hydroxyl radical formation. Stringent requirement for free iron coordination site. J Biol Chem. 1984 Mar 25;259(6):3620–3624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves S., Billington T. Optimum concentration of dissolved oxygen for the survival of virulent Treponema pallidum under conditions of low oxidation-reduction potential. Br J Vener Dis. 1979 Dec;55(6):387–393. doi: 10.1136/sti.55.6.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imlay J. A., Linn S. DNA damage and oxygen radical toxicity. Science. 1988 Jun 3;240(4857):1302–1309. doi: 10.1126/science.3287616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi H., Yoshii Z., Cox D. L. Electron microscopy of Treponema pallidum (Nichols) cultivated in tissue cultures of Sf1Ep cells. Infect Immun. 1986 Jul;53(1):32–37. doi: 10.1128/iai.53.1.32-37.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord J. M., Keele B. B., Jr, Fridovich I. An enzyme-based theory of obligate anaerobiosis: the physiological function of superoxide dismutase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1971 May;68(5):1024–1027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.5.1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger M., Smogór W. Study of the effect of pH and Eh values of the Nelson-Diesendruck medium on the survival of virulent Treponema pallidum. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 1966;14(4):445–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan A. R., Cone R. L., Elgert T. M. The mechanism of DNA strand breakage by vitamin C and superoxide and the protective roles of catalase and superoxide dismutase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1976 May;3(5):1139–1149. doi: 10.1093/nar/3.5.1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NELSON R. A., Jr, DIESENDRUCK J. A., ZHEUTLIN H. E. C., STACK P. S., BARNETT M. Studies on treponemal immobilizing antibodies in syphilis. I. Techniques of measurement and factors influencing immobilization. J Immunol. 1951 Jun;66(6):667–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris S. J., Edmondson D. G. Factors affecting the multiplication and subculture of Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum in a tissue culture system. Infect Immun. 1986 Sep;53(3):534–539. doi: 10.1128/iai.53.3.534-539.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris S. J., Miller J. N., Sykes J. A., Fitzgerald T. J. Influence of oxygen tension, sulfhydryl compounds, and serum on the motility and virulence of Treponema pallidum (Nichols strain) in a cell-free system. Infect Immun. 1978 Dec;22(3):689–697. doi: 10.1128/iai.22.3.689-697.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien R. W., Morris J. G. Oxygen and the growth and metabolism of Clostridium acetobutylicum. J Gen Microbiol. 1971 Nov;68(3):307–318. doi: 10.1099/00221287-68-3-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PORTNOY J., HARRIS A., OLANSKY S. Studies of the Treponema pallidum immobilization test. I. The effect of increased sodium thioglycollate and complement. Am J Syph Gonorrhea Vener Dis. 1953 Mar;37(2):101–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterkofsky B., Prather W. Cytotoxicity of ascorbate and other reducing agents towards cultured fibroblasts as a result of hydrogen peroxide formation. J Cell Physiol. 1977 Jan;90(1):61–70. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1040900109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picker S. D., Fridovich I. On the mechanism of production of superoxide radical by reaction mixtures containing NADH, phenazine methosulfate, and nitroblue tetrazolium. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1984 Jan;228(1):155–158. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(84)90056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radolf J. D., Norgard M. V., Schulz W. W. Outer membrane ultrastructure explains the limited antigenicity of virulent Treponema pallidum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 Mar;86(6):2051–2055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.6.2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao P. S., Luber J. M., Jr, Milinowicz J., Lalezari P., Mueller H. S. Specificity of oxygen radical scavengers and assessment of free radical scavenger efficiency using luminol enhanced chemiluminescence. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988 Jan 15;150(1):39–44. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(88)90483-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandok P. L., Knight S. T., Jenkin H. M. Examination of various cell culture techniques for co-incubation of virulent Treponema pallidum (Nichols I strain) under anaerobic conditions. J Clin Microbiol. 1976 Oct;4(4):360–371. doi: 10.1128/jcm.4.4.360-371.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadtman E. R., Wittenberger M. E. Inactivation of Escherichia coli glutamine synthetase by xanthine oxidase, nicotinate hydroxylase, horseradish peroxidase, or glucose oxidase: effects of ferredoxin, putidaredoxin, and menadione. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1985 Jun;239(2):379–387. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90703-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner B. M., Wong G. H., Sutrave P., Graves S. Oxygen toxicity in Treponema pallidum: deoxyribonucleic acid single-stranded breakage induced by low doses of hydrogen peroxide. Can J Microbiol. 1984 Dec;30(12):1467–1476. doi: 10.1139/m84-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner B., Wong G. H., Drummond L., Graves S. The role of respiratory protection on increased survival of Treponema pallidum (Nichols) when cocultivated with mammalian cells in vitro. Can J Microbiol. 1983 Nov;29(11):1595–1600. doi: 10.1139/m83-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner B., Wong G. H., Graves S. Susceptibility of Treponema pallidum to the toxic products of oxygen reduction and the non-treponemal nature of its catalase. Br J Vener Dis. 1984 Feb;60(1):14–22. doi: 10.1136/sti.60.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEBER M. M. Factors influencing the in vitro survival of Treponema pallidum. Am J Hyg. 1960 May;71:401–417. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]