Abstract

Annexin 1 (ANX-A1) exerts antimigratory actions in several models of acute and chronic inflammation. This is related to its ability to mimic the effect of endogenous ANX-A1 that is externalized on neutrophil adhesion to the postcapillary endothelium. In the present study we monitored ANX-A1 expression and localization in intravascular and emigrated neutrophils, using a classical model of rat peritonitis. For this purpose, a pair of antibodies raised against the ANX-A1 N-terminus (ie, able to recognize intact ANX-A1) or the whole protein (ie, able to interact with all ANX-A1 isoforms) was used by immunofluorescence and immunocytochemistry analyses. The majority (∼50%) of ANX-A1 on the plasma membrane of intravascular neutrophils was intact. Extravasation into the subendothelial matrix caused loss of this pool of intact protein (to ∼6%), concomitant with an increase in total amount of the protein; only ∼25% of the total protein was now recognized by the antibody raised against the N-terminus (ie, it was intact). In the cytoplasm of these cells, ANX-A1 was predominantly associated with large vacuoles, possibly endosomes. In situ hybridization confirmed de novo synthesis of ANX-A1 in the extravasated cells. In conclusion, biochemical pathways leading to the externalization, proteolysis, and synthesis of ANX-A1 are activated during the process of neutrophil extravasation.

The process of leukocyte extravasation is an essential part of the host inflammatory reaction to tissue injuries and infections. Movement of leukocytes outside the blood stream toward the site of inflammation is generally a transient phenomenon, which is completed once the pathogen(s) is immobilized, killed, and removed by phagocytosis. Nonetheless, in several pathologies leukocyte extravasation persists and these white blood cells are now responsible for tissue damage and subsequent irreversible alteration of the organ functionality. 1 It is not surprising that the process of leukocyte extravasation may be targeted to develop new and efficient forms of therapies for chronic and debilitating inflammatory diseases. 2

The events that promote the interaction between a circulating neutrophil and the endothelium of an inflamed microvascular beds have recently been dissected. Classes of adhesion molecules and chemoattractants able to initiate and sustain the leukocyte migration process have been identified, attributing to each of them specific functions in the phenomena of cell rolling, adhesion, and emigration. 3 Besides these pro-inflammatory mediators that have the function to attract the leukocyte out of the vessel into and toward the site of injury, other regulatory mechanisms must operate. For instance, a fraction of rolling leukocytes will actually become firmly adherent on the endothelium. 4 Similarly, a relevant proportion of adherent cells that are apparently ready to begin the emigration or diapedesis process, actually detach from the endothelium and return to the blood flow. 5,6 Therefore, endogenous regulatory mediators able to counteract the action of the pro-inflammatory mediators briefly mentioned above exist and operate at different phases of the leukocyte extravasation process. 7

Annexin 1 (ANX-A1) is a 37-kd member of the annexin superfamily of proteins that share the likely irrelevant function to bind phospholipids in the presence of calcium ions. 8 The N-terminal region of these proteins is unique to each member of the family, and it is likely to confer the specific activity that each annexin must play in cell pathophysiology. ANX-A1 is particularly abundant in neutrophils where it represents up to 4% of the cytosolic proteins. 9,10 This finding may be of pathological importance, because the large majority of ANX-A1 detected in inflamed tissues is associated with the presence of this cell type. 11,12

In a previous study we demonstrated that ANX-A1 is externalized onto the cell surface of neutrophils on adhesion to monolayers of endothelial cells in vitro. 7 Once on the plasma membrane, the protein is likely to be cleaved at the N-terminus to obtain the 33-kd isoform, and therefore released into the extracellular milieu. 7 In accordance with this model, ANX-A1 recovered from the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients suffering from several forms of lung diseases, including cystic fibrosis, is predominantly of the 33-kd isoform, being cleaved between Val-36 and Ser-37. 13,14 This catabolic feature significantly correlated with the presence of serine proteases, 14 long known to be able to cleave the protein N-terminal region in different sites. 15 The function of ANX-A1 externalized on the plasma membrane of adherent neutrophils is to down-regulate their emigration through the endothelial cells. Several laboratories, including our own, have demonstrated the antimigratory action of exogenous and, more importantly, endogenous ANX-A1, in vitro 16 and in vivo studies, both in acute 6,17,18 and chronic 19 models of inflammation. Based on all this experimental evidence we proposed ANX-A1 as an autocrine inhibitor of the process of neutrophil extravasation. 7 In this respect ANX-A1 groups with a series of endogenous anti-inflammatory agonists. Adenosine 20 and lipoxin A4 21 generated in the microenvironment of a leukocyte adherent to the postcapillary endothelium act to reduce the degree of cell extravasation.

Despite this wealth of pharmacological data, very few in vitro studies have investigated the subcellular localization of ANX-A1 in resting or activated neutrophils. During the process of phagocytosis of the U937 monocytic cell line, ANX-A1 localizes around the phagosome, as demonstrated by immunocytochemical analysis. 22 However this redistribution of the protein is stimulus-dependent, and it occurs when these cells phagocytose Escherichia coli but not Brucella suis. 22 It is also cell-specific because it does not occur in neutrophils phagocytosing an attenuated strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis 23 or opsonized zymosan. 24 In the latter in vitro study, we have been able to determine a high degree of co-localization between ANX-A1 and gelatinase in the matrix of cytosolic granules of human resting neutrophils. Therefore, increased ANX-A1 levels onto the plasma membrane of adherent neutrophils is consequent to a process of exocytosis. 24,25

So far, no studies have monitored ANX-A1 distribution in migrating leukocytes by immunocytochemistry during an on-going inflammatory reaction in vivo. We have analyzed here the neutrophils, and assessed the subcellular localization of ANX-A1 in neutrophils adherent to the postcapillary venule endothelium as well as in cells already extravasated into the tissue. Intact (37 kd) ANX-A1 is predominantly found on the membrane of intravascular adherent neutrophils in vivo. Once in the extravascular tissue, the majority of the protein contained in the neutrophil is cleaved (33 kd isoform). Contact with extravascular matrix up-regulates ANX-A1 synthesis as determined by in situ hybridization analysis.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (200 to 250 g body weight; Banton and Kingsman, Hull, UK) maintained on a standard chow pellet diet with tap water ad libitum were used for all experiments. Animals were housed at four animals per cage in a room with controlled lighting (lights on 8:00 to 20:00 hours) in which the temperature was maintained at 21 to 23°C, and the rats used 2 to 3 days after arrival. Animal work was performed according to Home Office regulations (Guidance on the Operation of Animals, Scientific Procedures Act 1986).

Model of Inflammation

For pharmacological treatment, rats were administered human recombinant ANX-A1 (a generous gift of Dr. E. Solito, Inserm U332, Paris, France) 26 intravenously at doses of 20 or 100 μg/kg 27 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), or with 100 μl PBS alone. It must be noted that >90% sequence homology exists between human and rat ANX-A1 species. 28 Five minutes later, experimental peritonitis was induced by the intraperitoneal injection of 1.5 mg/kg of carrageenin (type lambda; Sigma Chemical Co., Poole, Dorset, UK) in PBS. In all cases rats were sacrificed 4 hours later by CO2 exposure, this time-point being chosen because of the intense neutrophilic infiltrate produced in response to local injection of carra-geenin. 29

Neutrophil migration was assessed both into the extravascular tissue and into the peritoneal cavity. Cavities were washed with 2 ml of PBS containing 25 U/ml heparin. Aliquots of the lavage fluids were stained with Turk’s solution (0.01% crystal violet in 3% acetic acid). Fragments of rat mesenteries (flat-mount preparations) 30 fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde were stained with toluidine blue solution (1% toluidine blue in 1% borax solution). Differential cell counts were performed using a Neubauer hemocytometer and light microscopy (Olympus B061). The extent of neutrophil infiltration into the mesenteric tissues was then quantified by an observer unaware of the treatments as described below.

Western Blot Analysis

Mesenteries were dissected and immediately frozen in liquid N2, and homogenized at 4°C in 50 mmol/L Tris buffer rich in protease inhibitors (1 mmol/L phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride, 1.5 mmol/L pepstatin A, and 0.2 mmol/L leupeptin, pH 7.4) and centrifuged (4,000 × g, 5 minutes, 4°C). Protein concentrations in supernatants were determined by the Bradford assay (Sigma) and adjusted to 2 mg/ml, mixed 1:1 with 2× loading buffer (125 mmol/L Tris base, 2 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 10% mercaptoethanol, 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 20% glycerol, and 0.1% Coomassie blue, pH 6.8), and boiled for 5 minutes. Samples (20 μg proteins per lane), molecular weight markers, and standard ANX-A1 (10 to 1,000 ng) were resolved by gel electrophoresis on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. ANX-A1 was detected using a specific monoclonal antibody raised against the entire protein. 31 The signal was amplified with horseradish peroxidase-linked rat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:3,000; Serotec, Oxford, UK) and visualized on BioMax MR-1 film (Kodak, Rochester, NY) after the application of Luminol (ECL; Amersham, Little Chalfont, UK). Densitometric analysis of the data produced a standard curve, and unknowns were quantified by interpolation.

Fixation, Processing, and Embedding for Immunofluorescence and Electron Microscopy

Animals were anesthetized by injection with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg) and perfused through the heart left ventricle with sterile saline (30 to 50 ml per rat) for 30 to 60 seconds. This was followed by a slow infusion of 100 ml of cold paraformaldehyde (2% in PBS) lasting for 5 to 10 minutes. After perfusion, fragments of the mesentery were postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.5% glutaraldehyde, 0.1% sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) for 24 hours at 4°C. They were then washed in sodium cacodylate, dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol, and embedded in LR Gold (London Resin Co., Reading, Berkshire, UK). Sections (0.5 μm) were prepared for immunofluorescence and stored at −70°C. For electron microscopy, ∼90-nm sections were cut on an ultramicrotome (Reichert Ultracut; Leica, Austria) and placed on nickel grids for immunogold labeling.

Fluorescence Immunohistochemistry

Sections (0.5-μm thick) were incubated for 1 hour with 10% sodium periodate (Sigma), then washed three times in 10 mmol/L PBS (pH 7.3) for 15 minutes. Fragments of the mesentery were permeabilized by 15 minutes incubation in 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS (repeated three times). Nonspecific binding sites were blocked with normal rabbit serum in 0.1% bovine serum albumin in PBS. Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary antibody. Sections were then washed in PBS (15 minutes) and incubated with the secondary antibody, a fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated rabbit IgG anti-sheep IgG (Sigma), diluted 1:50, for 1 hour at room temperature. A final wash again in PBS (15 minutes) preceded mounting in Citifluor (Stanstead, Essex, UK).

Two distinct anti-ANX-A1 antibodies were used. A polyclonal sheep anti-ANX-A1 serum termed LCS3 raised against full-length human ANX-A1, and successfully used to detect the protein in rat systems, 32 by both immunofluorescence and immunocytochemical techniques. 24,33 A sheep anti-ANX-A1 serum termed LCPS1 raised against the unique N-terminal region of human ANX-A1 (peptide Ac2-26, Ac-AMVSEFLKQAWFIENEEQEYVQTVK), 8 previously used to measure the levels of intact protein (37-kd isoform) in murine cells 34 and human neutrophils 24 was also used. Both LCS3 and LCPS1 have successfully been used to monitor ANX-A1 expression in rat mesenteric mast cells by electron microscopy, 35 and have been shown to neutralize the activities of rat ANX-A1. 36,37 Final dilution was 1:2,000 for both antisera.

As controls for the reaction, sections were incubated with nonimmune sheep serum (NSS; Sigma) instead of the primary antibody, at the same working dilution of 1:2,000. Another negative control was produced by pre-adsorbing LCS3 with 100 ng of ANX-A1 or LCPS1 with 10 μg of peptide Ac2-26. Sections were examined at a wavelength of 435 nm in an Olympus model BH2-RFCA model fluorescence microscope.

Postembedding Immunogold Labeling

To detect ANX-A1 in the tissues, a recently established immunogold staining procedure was used. 35 Sections of the mesenteric tissues were prepared for electron microscopy by standard methods. Briefly, mesentery was stained with uranyl acetate (2% w/v in distilled water), dehydrated through increasing concentrations of ethanol (70 to 100%), and embedded in LR Gold resin. Ultrathin sections (0.2 μm) were incubated with the following reagents at room temperature: 1) 0.1 mol/L PBS containing 0.1% egg albumin (PBEA); 2) 2.5% normal rabbit serum in PBEA for 1 hour; 3) the sera LCS3, LCPS1, or nonimmune sheep serum (final dilutions of 1:300 in PBEA); 4) after five washes (3 minutes each) in PBEA, with a donkey anti-sheep IgG (Fc fragment-specific) antibody (Ab) (1:50 in PBEA) conjugated to 15-nm colloidal gold (British Biocell, Cardiff, UK). After 1 hour at 4°C, sections were extensively washed in PBEA and then in distilled water. Ultrathin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate before examination on a Jeol 1200 EX II electron microscope.

In analogy to our study with human neutrophils in vitro, 24 selected sections were double-labeled with LCPS1 and with an anti-human gelatinase rabbit serum (generous gift of Dr. N. Borregaard, Copenhagen, Denmark). Antibodies were used at a final dilution of 1:200. LCPS1-mediated immunoreactivity was detected with a donkey anti-sheep IgG (Fc fragment-specific) Ab (1:50 in PBEA) conjugated to 5-nm colloidal gold (British Biocell), whereas the anti-gelatinase staining was detected with a goat anti-rabbit IgG (Fc fragment-specific) Ab (1:50 in PBEA) conjugated to 15-nm colloidal gold (British Biocell).

Nonradioactive in Situ Hybridization with Oligonucleotide Probes

Animals were perfused as described above. Flat-mount preparations of the mesenteries were processed for in situ hybridization. The fragments were postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.5% glutaraldehyde, 0.1 mol/L sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4, for 2 hours at 4°C. After fixation, the sections were mounted on Superfrost (BDH, Poole, UK) slides. Hybridization histochemistry was performed according to a published method. 35,38 The oligonucleotide probes were synthesized and purified commercially (Genosys, Poole, UK) and were directed against the N-terminal domain of LC1. Antisense probe: 5′ GCA GGC CTG CTT GAG GAA TTC TGA TAC CAT TGC C3′. Sense probe: 5′ CGT CCG GAC GAA CTC CTT AAG ACT ATG GTA ACG G3′. Oligonucleotides were labeled by tailing the 3′ end with terminal transferase (Roche, Lewes, UK) and digoxigenin 11-dUTP (Roche). Oligonucleotide probes were checked against the GenBank database to eliminate sequences preventing obvious homologies with other known probes. Sections were washed with PBS, followed by treatment with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS (30 minutes) at room temperature. Sections were then incubated in prehybridization buffer (4× sodium chloride/sodium citrate, 1× Denhardt’s solution, 10 μg/ml denatured yeast tRNA, 1 μg/ml denatured salmon sperm DNA) at 37°C for 2 hours before incubation with labeled oligonucleotides (20 to 40 nmol/L) in hybridization buffer (50% formamide, 80 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 10 μg/ml tRNA, 600 mmol/L NaCl, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 4 mmol/L EDTA) at 37°C, overnight.

After hybridization, sections were washed in 2× standard saline citrate and then placed in 0.1% standard saline citrate at room temperature. After washes in 0.1 mol/L Tris buffer for 20 minutes, slides were soaked in blocking solution (100 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1% bovine serum albumin) for 30 minutes at room temperature, before immersion in anti-digoxigenin alkaline phosphatase conjugate (Roche, UK) diluted 1:500 in blocking buffer for 2 hours at room temperature. Finally, slides were washed in buffer A (0.1 mol/L Tris-HCl, 1 mol/L NaCl, 2 mmol/L MgCl2, 1% bovine serum albumin, 0.1% Triton X-100) for 10 minutes and then with detection buffer (100 mmol/L Tris, pH 9.5, 100 mmol/L NaCl, 50 mmol/L MgCl2). They were reacted in a detection solution containing 360 mg/ml nitro blue tetrazolium and 140 mg/ml 5-bromo-6-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate p-toluidine salt (Roche, UK) for 48 hours at room temperature. The sections were mounted and coverslipped with Glycergel media (Sigma). Then, the same sections were stained with propidium iodide (Sigma) and were examined in a fluorescence microscope, using interference filters at two excitation wavelengths of 334 to 365 and 546 nm (Olympus model BH2-RFC).

Data Handling and Statistical Analysis

Cell extravasation data are reported as mean ± SE of four rats per group. Analysis of leukocyte infiltration in the mesenteric connective tissue was performed with a high-power objective (×40) counting neutrophils in 100-μm 2 areas (analyzing at least 10 distinct determinations per sample). Similarly, randomly photographed sections of rat tissues were used for the immunocytochemical analysis. The area of each cell compartment (membrane, cytosol, and nucleus) for intravascular and extravasated neutrophils was determined with a point-counting morphometric method using a square test grid with 8.7-mm spacing. 35 Analysis was performed by an operator unaware of the different experimental groups. The density of immunogold (number of gold particles per μm2) was calculated and expressed for each cell compartment. Values are reported as mean ±SEM of n number of the electron micrographs.

Statistical differences between means were determined by analysis of variance followed, if significant, by the Bonferroni test. 39 A probability value less than 0.05 was taken as significant.

Results

Carrageenin Peritonitis

Exogenous and endogenous ANX-A1 down-regulate neutrophil extravasation in several models of acute inflammation. 6,7,17,22 Initially, we tested the susceptibility of carrageenin-induced neutrophil migration to the inhibitory action of ANX-A1. Administration (intravenously) of the protein produced a dose-related reduction in the number of neutrophils recovered from the peritoneal cavities at the 4-hour time-point (Figure 1a) ▶ . This effect was mirrored by a similar reduction in extravasated neutrophils as counted in the mesenteric tissues (Figure 1a) ▶ .

Figure 1.

Anti-migratory effect of ANX-A1 and detection of endogenous ANX-A1 in inflamed mesenteries. Rats (n = 4) were treated intravenously with vehicle, PBS (1 ml/kg), or ANX-A1 (20 to 100 μg/kg) 5 minutes before intraperitoneal injection of carrageenin (1.5 mg/kg). a: Dose-dependent reduction by ANX-A1 of neutrophil extravasation into the peritoneal cavity and in the mesenteric tissue. b: Detection of endogenous ANX-A1 in the inflamed mesenteries by Western blot analysis and reduction by the pharmacological treatment. Human recombinant ANX-A1, 500 ng, was used as positive control. c and d: Densitometric analysis for the ANX-A1 standard curve and the mesenteric tissue homogenates (n = 4). Data are mean ±SEM. #, P < 0.05 versus control; *, P < 0.05 versus vehicle group.

ANX-A1 immunostaining was hardly detected by Western blotting in noninflamed mesenteries, whereas a strong increase in tissue ANX-A1 was observed during the inflammatory reaction (Figure 1b) ▶ . Figure 1d ▶ illustrates this finding in a semiquantitative manner, using a standard curve generated with human recombinant ANX-A1 (Figure 1c) ▶ . The anti-migratory effect of ANX-A1 produced a dose-dependent reduction in tissue immunoreactivity for the endogenous protein (Figure 1, b and d) ▶ . All subsequent analyses were conducted on mesenteric tissue inflamed with carrageenin and collected at the 4-hour time-point.

ANX-A1 Expression in Neutrophils Adherent to or Migrated through the Postcapillary Endothelium

The anti-ANX-A1 sera were initially validated by immunofluorescence. Figure 2a ▶ gives a histological view of the inflamed mesentery as seen 4 hours after carrageenin with the presence of intravascular and extravascular neutrophils. Neutrophils adherent to the postcapillary endothelium were positive for ANX-A1 (Figure 2b) ▶ . Similarly, neutrophils extravasated across the postcapillary venules were also positive for the protein. As control for the primary antibodies nonimmune sheep serum was tested, but this serum did not give any positive reaction (data not shown). Similarly, pre-adsorption of LCS3 or LCPS1 with the respective immunogens (ANX-A1 or peptide Ac2-26) greatly diminished the immunofluorescent signal (Figure 2 ▶ , compare c with d, and e with f). Together, these data indicated that the LCS3 and LCPS1 sera were genuinely detecting leukocyte ANX-A1, and encouraged the analysis by transmission electron microscopy.

Figure 2.

Light micrographs of rat mesenteries showing ANX-A1 immunoreactivity in intravascular and extravascular neutrophils. a: Inflamed mesentery as seen 4 hours after carrageenin with neutrophils adherent to the postcapillary venule (arrowheads) and in the extravascular tissue (open arrow). Endothelium (arrow). Section (0.5 μm) was stained with toluidine blue. b: Immunofluorescence labeling of ANX-A1 in sections of rat mesentery by LCS3. Neutrophils adherent (arrowheads) to the postcapillary endothelium (arrow) were positive for ANX-A1. c, e, and f: Examples of LCS3 (c and d) and LCPS1 (e and f) immunoreactivity in extravasated neutrophils (arrowhead). Staining was obtained with both antibodies (c and e) and greatly diminished after pre-adsorption with the respective antigen (ANX-A1 or peptide Ac2–26) (d and f). Scale bar, 10 μm.

ANX-A1 expression detected by postembedding immunogold labeling was then analyzed to define the subcellular localization of the protein in the neutrophils undergoing recruitment. In neutrophils adherent to the endothelium, gold particles were detected throughout the cytosol, with a significant proportion being observed also in the plasma membrane (Figure 3, a and b) ▶ . Modest but reproducible staining was also detected in the nucleus. Table 1 ▶ reports the quantitative data for the two antibodies as measured in 10 distinct photographs, with the immunoreactivity quantified in the nucleus, cytosol, and membrane compartments. The majority (∼50%) of LCPS1 immunoreactivity that detects intact (37 kd) protein was within the membrane compartment, whereas LCS3 immunoreactivity (that detects both intact and cleaved 33- kd isoforms) seemed to be more equally distributed throughout the cell (Table 1) ▶ . Intact ANX-A1 immunoreactivity was also detected at the points of contact between adherent neutrophils and endothelial cells. A close interaction between these two cells is also seen in Figure 3c ▶ . No labeling was detected in sections incubated with the control nonimmune sheep serum (Figure 3d) ▶ .

Figure 3.

Immunocytochemistry for ANX-A1 using LCPS1 and LCS3 in intravascular neutrophils. a: LCPS1 staining for ANX-A1 shows a significant proportion in the plasma membrane (arrowheads). Immunoreactivity throughout the cytosol and in granules (arrows) can also be seen. En, endothelial cells. b: Similar but higher immunostaining with LCS3. Arrowheads indicate gold particles in the plasma membrane. c: Example of ANX-A1 labeling at points of contact (arrows) between an adherent neutrophil (Nø) and the endothelial cell (En). d: Absence of gold labeling in sections incubated with control nonimmune sheep serum. Scale bars: 0.5 μm (a); 0.2 μm (b–d).

Table 1.

Density of ANX-A1 Immunogold Particles in Neutrophils Interacting with Postcapillary Venule Endothelium

| Antibody (specificity) | ANX-A1 immunoreactivity (gold particles/μm2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Plasmamembrane | % | Cytoplasm | % | Nucleus | % | |

| LCPS1 (intact ANX-A1) | 36.6 ± 5.7 | 18.5 ± 5.2 | 50 | 9.28 ± 0.7 | 25 | 8.82 ± 1.0 | 25 |

| LCS3 (all ANX-A1 isoforms) | 68.5 ± 5.0* | 14.6 ± 2.9 | 21 | 28.7 ± 5.5 | 42 | 25.2 ± 5.4 | 37 |

Data are mean ±SEM of 10 distinct neutrophils analyzed in the mesenteric postcapillary venule of rats treated with carrageenin (1.5 mg/kg intraperitoneally for 4 hours). Electron microscopy analysis was performed as described in the Materials and Methods using the two antisera LCPS1 (to detect intact 37-kd ANX-A1) and LCS3 (to detect all ANX-A1 isoforms).

*, P < 0.005 versus LCPS1.

Extravasated neutrophils were also strongly positive for ANX-A1, as detected 4 hours after carrageenin injection. An intense immunoreactivity was observed with LCS3, with apparent foci of expression of the protein (Figure 4a) ▶ . In particular, cytoplasmic vacuoles contained a high amount of ANX-A1, as detected with LCS3. In contrast, lower immunoreactivity for intact ANX-A1 was obtained with LCPS1 in extravascular neutrophils (Figure 4b) ▶ . Table 2 ▶ illustrates these findings in a quantitative manner. LCPS1 immunoreactivity in the membrane compartment was greatly diminished compared to intravascular cells, and the gap between total LCPS1 and LCS3 immunoreactivity was also increased (Table 2) ▶ . These data indicate an overall decrease in intact 37-kd ANX-A1 species in migrated neutrophils.

Figure 4.

Immunocytochemistry for ANX-A1 using LCPS1 and LCS3 in extravascular neutrophils. Extravasated neutrophils were greatly activated as indicated by the presence of large vacuoles in the cytosol (asterisks). a: LCS3 produced intense immunoreaction in the cytosol and nucleus. Foci of ANX-A1 expression are found in the vacuoles. b: A lower degree of immunoreactivity was obtained with LCPS1. Scale bars, 0.5 μm.

Table 2.

Density of ANX-A1 Immunogold Particles in Neutrophils Extravasated into the Rat Mesenteric Tissue

| Antibody | ANX-A1 immunoreactivity (gold particles/μm2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Plasmamembrane | % | Cytoplasm | % | Nucleus | % | |

| LCPS (intact ANX-A1) | 21.1 ± 4.7 | 1.1 ± 0.9 | 5 | 10.2 ± 3.0 | 49 | 9.8 ± 1.8 | 46 |

| LCS3 (all ANX-A1 isoforms) | 93.6 ± 6.0* | 31.9 ± 4.6 | 34 | 43.9 ± 8.3 | 47 | 20.5 ± 5.4 | 22 |

Data are mean ±SEM of 10 distinct neutrophils analyzed in the extravascular tissue of rat mesenteries treated with carrageenin (1.5 mg/kg intraperitoneally for 4 hours). Electron microscopy analysis was performed as described in the Material and Methods using the two antisera LCPS1 (to detect intact 37-kd ANX-A1 and LCS3 (to detect all ANX-A1 isoforms).

*, P < 0.05 versus LCPS1.

Double-staining with LCPS1 and the anti-gelatinase antibody of the inflamed specimens demonstrated a good degree of co-localization between the two antigens in intravascular neutrophils (Figure 5a) ▶ . As shown above, extravasated neutrophils were significantly positive for ANX-A1, whereas for gelatinase a much lower degree of immunoreactivity was observed (Figure 5b) ▶ .

Figure 5.

Analysis of ANX-A1 and gelatinase localization in intravascular and extravasated neutrophils. Co-localization of ANX-A1 with gelatinase, after immunogold labeling with 5-nm particles (anti-ANX-A1 serum, LCPS1) and 15-nm particles (anti-gelatinase serum). a: Intravascular neutrophil with examples of gelatinase and ANX-A1 immunoreactivity in close vicinity (arrowheads); En, endothelium. b: Extravascular neutrophil with almost absent gelatinase immunoreactivity, and a high degree of ANX-A1 protein expression. As in Figure 4 ▶ , the presence of large vacuoles in the cytosol is indicated by asterisks. C, collagen fibers. Scale bars: 0.2 μm (a), 0.5 μm (b).

ANX-A1 Immunoreactivity in Postcapillary Venule Endothelial Cells

Endothelial cells of the postcapillary venules were found to contain much less ANX-A1 as detected with LCS3. Table 3 ▶ reports the quantitative analysis of ANX-A1 immunoreactivity in endothelial cells, as determined by immunocytochemistry and quantified in 12 distinct micrographs. A significant difference between LCPS1 and LCS3 immunoreactivity was seen between endothelial cells in contact with an intravascular neutrophil or already passed by a migrated neutrophil. The former antibody detecting intact 37-kd ANX-A1 in endothelial cells gave modest results irrespective of the spatial position of the blood-borne leukocyte, whereas a stronger immunoreactivity was seen with LCS3 once neutrophils had migrated into the extravascular space (Table 3) ▶ .

Table 3.

Density of ANX-A1 Immunogold Particles in Postcapillary Venule Endothelial Cells Interacting with Extravasating Neutrophils

| Neutrophil localization | ANX-A1 immunoreactivity in endothelial cells (gold particles/μm2) | |

|---|---|---|

| LCPS1 antiserum (intact ANX-A1) | LCS3 antiserum (all ANX-A1 species) | |

| Intravascular | 12.8 ± 2.0 | 23.9 ± 1.8* |

| Extravascular | 8.6 ± 1.5 | 45.8 ± 6.2*† |

Data are mean ±SEM of 12 distinct endothelial cells analyzed, distinguishing between those with an adherent intravascular neutrophil from those in close vicinity to a neutrophil in the extravascular space. Inflammation was indeed with carrageenin (1.5 mg/kg intraperitoneally for 4 hours). Electron microscopy analysis was performed as described in Materials and Methods using the two antisera LCPS1 (to detect intact 37 kd ANX-A1) and LCS3 (to detect all ANX-A1 isoforms).

*, P < 0.05 versus LCPS1.

†, P < 0.05 versus intravascular.

In Situ Hybridization for ANX-A1 mRNA in the Inflamed Mesenteries

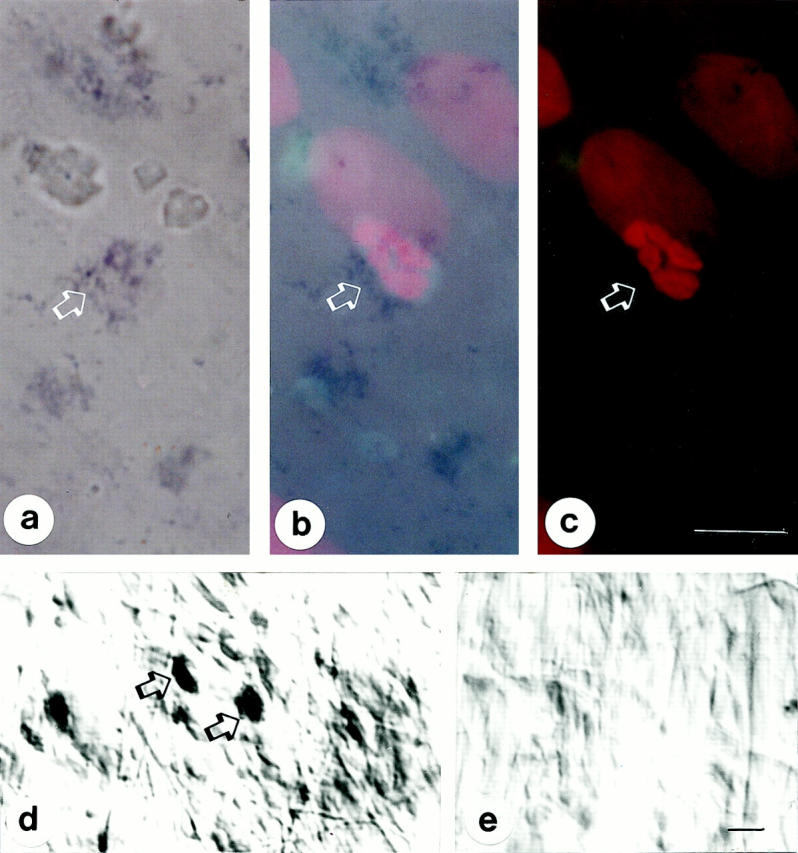

Positive ANX-A1 mRNA signals were observed in the cytosol of neutrophils extravasated in the mesenteric tissue of carrageenin-treated rats (Figure 6, a and d) ▶ . The identity of the cell type was confirmed morphologically by staining of the same sections with propidium iodide and analysis in the fluorescence microscope (Figure 6 ▶ ; a, b, and c). Figure 6b ▶ shows the strict association between ANX-A1 mRNA and the neutrophil nucleus, using fluorescence with partial light. No signal was seen in inflamed tissues stained with sense oligonucleotides, used as negative control for the in situ hybridization reaction (Figure 6e) ▶ .

Figure 6.

ANX-A1 mRNA expression in extravasated neutrophils as assessed by in situ hybridization in flat mount rat mesenteries. a: ANX-A1 mRNA is detected in neutrophils after tissue incubation with specific antisense oligonucleotide (arrows). a, b, and c: The identity of the cell type was confirmed by staining of the same sections with propidium iodide (color staining of the nucleus) and analysis in the fluorescence microscope (interference filters at two excitation wavelengths of 334 to 365 and 546 nm). In b the two images were superimposed. d: In situ hybridization product formation after incubation of mesenteric tissue with the antisense oligonucleotides, but not in e after tissue incubation with the sense oligonucleotide. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Discussion

In the past 10 years a fundamental inhibitory action of ANX-A1 on the process of polymorphonuclear leukocyte extravasation has been reported by several groups, including our own. 17,18,40 We began the present study by validating this effect in the model of carrageenin peritonitis. A potent and dose-dependent inhibition of neutrophil extravasation and recovery in the lavage fluids was found on treatment with human recombinant ANX-A1. Therefore, this model of acute peritonitis can be added to the list of experimental systems in which neutrophil extravasation is down-regulated by systemic injection of ANX-A1. 41

Human and rodent neutrophils have abundant ANX-A1 9,34,42-44 . A substantial amount of protein externalization and secretion (>60% of total content) has been observed on adhesion of this cell type to monolayers of endothelial cells in vitro. 16 This is an important issue in our understanding of the biology of this protein. Apart from one study that reported a constitutive secretion of ANX-A1 in human semen, 45 it is unclear how the protein can exit the cell and be found in the extracellular space. What is evident, though, is that ANX-A1 protein expression is often associated with inflammatory conditions characterized by accumulation of blood-borne neutrophils. This has been observed in the human lung 13,14 and also in rodent models of gut inflammation. 11 In the latter study, inflamed tissues secreted ANX-A1 11 and this was strongly associated with presence of neutrophils. 12 In the present investigation we could detect a marked increase in mesenteric ANX-A1 expression in relation to neutrophil infiltration into this tissue. This observation, together with the functional data obtained with exogenous administration of ANX-A1, made carrageenin peritonitis a suitable model to determine the ultrastructural localization of ANX-A1 during an on-going process of neutrophil extravasation.

Intravascular neutrophils were found to be positive for ANX-A1, distributed in the nucleus, the cytoplasm, and in the plasma membrane. This distribution is generally in line with observations produced in other cell types. A partial nuclear localization for ANX-A1 has been reported in endothelial cells 46 and also in human neutrophils. 24 The function of nuclear ANX-A1 is presently obscure, although electron microscopy analysis of rat mesenteries showed the presence of ANX-A1 in the nucleus of peri-venular mast cells and macrophages. 35 A different pattern of staining was obtained with the two polyclonal antibodies. LCPS1, raised against an N-terminus peptide unique to ANX-A1, 8,34 gave a positive signal that was more abundant in the plasma membrane compartment (∼50% in intravascular neutrophils). The LCS3 serum produced an almost even staining throughout the adherent neutrophil, with equal amounts among nucleus, cytosol, and plasma membrane. Therefore, the majority of ANX-A1 present in the plasma membrane of adherent neutrophils is in the intact isoform (37 kd). This is the biologically active species of the protein. 47,48 The present in vivo demonstration of the presence of intact ANX-A1 on the cell surface of adherent neutrophils extends studies performed with human cells in vitro. 16,24 Overall these data support the hypothesis of an autocrine action for ANX-A1 externalized on the cell surface 7 in a model susceptible to the inhibitory action of the protein.

The mechanism by which ANX-A1 is transported onto the plasma membrane during the process of neutrophil migration in vivo remains partially obscure. ANX-A1 is mainly localized within the gelatinase granules of human neutrophils, as demonstrated by the in vitro co-localization of antibodies raised against human gelatinase and ANX-A1. 24 Because gelatinase granules are mobilized onto the cell surface after neutrophil adhesion to the endothelium, 25 this process of controlled exocytosis can permit movement into the extracellular space of a protein devoid of signal peptide as ANX-A1. 49 In intravascular neutrophils, adherent to the postcapillary venule endothelium, we could demonstrate a good degree of co-localization between intact ANX-A1 and gelatinase. A different profile was obtained in extravasated cells, with a very low degree of gelatinase immunoreactivity indicating that the enzyme was almost entirely exocytosed. 25 ANX-A1 follows a different biochemical path, and this is discussed below. From this set of experiments, we can propose that adhesion-dependent neutrophil exocytosis might be responsible for ANX-A1 externalization also in an in vivo experimental condition. It is possible that localization in similar or other subcellular organelles may be responsible for the export of ANX-A1 outside other cell types 33,50 including the monocyte. 51

A striking difference was observed between the ANX-A1 immunoreactivity produced by the two anti-sera with respect to neutrophils extravasated in the extracellular matrix. The plasma membrane of these cells was significantly less positive for LCPS1 than intravascular adherent neutrophils. An opposite result was obtained with LCS3. Extravascular neutrophils demonstrated the classical signs of cell activation, with membrane ruffles and presence of large vacuoles in the cytosol. ANX-A1 immunoreactivity was particularly accumulated in the latter organelles, probably generated by endocytosis. Relevantly, ANX-A1 association with early but not multivesicular endosomes has been reported in MDCKII cells. 52 In our experimental conditions and cells, the immunoreactivity detected by electron microscopy was mainly because of the cleaved (33 kd) ANX-A1 species.

We believe this result is of importance for determining the biochemical pathways that may be operating on ANX-A1 during the process of neutrophil extravasation. In fact, it has long been known that analysis of biological samples for ANX-A1 content often generated a double band when determined by Western blotting analysis, corresponding to the 37- and 33-kd species. 12,53 The occurrence of a putative spontaneous ANX-A1 protein degradation has been invoked as responsible for this recurrent feature. 47 We have recently proposed the existence of a specific enzymatic activity (termed lipocortinase) responsible for cleavage of intact ANX-A1 and removal of a portion of the N-terminus, 7,16 selectively activated during the process of neutrophil activation. Such an activity will be responsible for the appearance of the cleaved (33 kd) isoform in inflammatory samples, as seen in the bronchoalveolar lavage of patients suffering from different forms of lung inflammatory disorders 13 or in the gut of rats affected by colitis. 12 A recent study by Tsao and colleagues 14 has sequenced the exact cleavage site in human ANX-A1 recovered in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients affected by cystic fibrosis, proposing a causal role for neutrophil elastase. A different site of cleavage has been proposed by a distinct study performed with reconstitute neutrophil granules in vitro. 54 In addition, it is also possible that ANX-A1 phosphorylation may change the susceptibility of the protein to proteolysis. 55

Our data demonstrate for the first time the occurrence of ANX-A1 cleavage at the ultrastructural level monitoring neutrophils in the process of interacting, or a few hours after the interaction, with the postcapillary venule endothelium. Intravascular neutrophils adherent to the endothelium have the majority of cell surface ANX-A1 present in the intact form, whereas extravasated cells have the majority of cell-associated ANX-A1 in the cleaved isoform, localized in large endosome-like vacuoles. We suggest that the immunoreactivity detected with LCS3 in the vacuoles of extravasated neutrophils is because of the internalized cleaved ANX-A1, which was intact and on the cell surface at the step of neutrophil adhesion. Figure 7 ▶ schematizes this working hypothesis that, in our opinion, is the most likely to explain the data obtained by this immunocytochemical investigation.

Figure 7.

Model to summarize neutrophil ANX-A1 mobilization during the extravasation process. a: Circulating (resting) neutrophils have the majority of their ANX-A1 intact (37-kd isoform). 16,22 b: Neutrophil adhesion to the endothelium causes externalization of the protein on the leukocyte plasma membrane (this study and Harricane et al 22 ). c: A cleavage process may here take place. 16 d: Extravasated neutrophils contain mainly cleaved ANX-A1 (33-kd isoform), with a predominant intracellular localization. Neutrophil contact with extracellular matrix proteins leads to de novo ANX-A1 synthesis as seen by in situ hybridization. Cleaved ANX-A1 (33 kd) is mainly found in the endothelial cells after neutrophil diapedesis.

This scheme (Figure 7) ▶ includes the observation, partially unexpected, that endothelial cells acquire ANX-A1 (mainly of the 33-kd species) during the process of neutrophil diapedesis. This is corroborated by the larger amount of ANX-A1 detected in these cells with LCS3, but not LCPS1, after neutrophil passage. The existence of a potential interaction, and ANX-A1 mobilization during the cross-talk between the adherent neutrophil and endothelial cells has been previously hypothesized. 56 Goulding and Guyre 56 suggested that ANX-A1 could be retained by low-affinity binding sites on endothelial cells and transferred to the emigrating neutrophil that express high-affinity binding sites for the protein. Our data indicate, however, that this interaction goes in the opposite direction. Neutrophil-derived ANX-A1 can be taken up by endothelial cells. In agreement with other studies, endothelial cells contain much less ANX-A1 than blood-borne neutrophils, 16,24 however their content is increased after neutrophil trans-endothelial passage. It is the cleaved isoform of ANX-A1 that is predominantly found in these cells, as seen by comparing the number of gold particles measured with LCS3 and LCPS1. We cannot exclude the synthesis in endothelial cells of an ANX-A1 species not recognized by LCPS1. However, LCPS1 produced a good degree of immunoreactivity in neutrophils present in the same sections. We hypothesize that ANX-A1 can be transferred from the neutrophil plasma membrane after the proposed action of the specific enzyme that removes a large portion of the N-terminus. However this phenomenon must be carefully investigated in subsequent studies.

Finally, in situ hybridization of flat-mount mesenteric preparations detected ANX-A1 mRNA in extravasated neutrophils. This is the first positive in situ hybridization data obtained for ANX-A1 in these cells, and in a way it is not surprising because of the strong positive signal for ANX-A1 protein displayed by inflamed tissues. 11 Neutrophil passage though monolayers of endothelial cells in vitro does not activate ANX-A1 synthesis. 16 It is therefore likely that neutrophil interaction with the extracellular matrix signals for activation of the gene. In addition, ANX-A1 gene is under control of specific transcription factors, such as nuclear factor interleukin-6 or C/EBP-β in the mouse, 57,58 and the cytokine interleukin-6 present during the early phases of carrageenin inflammation. 59 Future studies will address the mechanisms responsible for ANX-A1 gene activation in extravasated neutrophils. What is important, at this stage, is the observation that cell extravasation leads to the activation of genes for pro-inflammatory cytokines (eg, tumor necrosis factor 60 ) as well as for anti-inflammatory mediators such as ANX-A1.

An interesting comparison can be made among the different mediators that fall in the group of anti-inflammatory agonists. 7 With respect to neutrophil adhesion to monolayers of endothelial cells, the ANX-A1 derived N-terminal peptide Ac2-26 produces ∼60% inhibition at 11 μmol/L, 61 with lipoxin A4 and aspirin-triggered lipoxin A4 producing >50% reduction at 5 μmol/L concentration. 62 Full-length ANX-A1 inhibits shedding of l-selectin from the cell surface of activated neutrophils by a third (to ∼60% of control l-selectin levels) at 3 μg/ml corresponding to 80 nmol/L, 63 whereas aspirin-triggered lipoxin A4 produced a similar effect at 50 nmol/L. 62 Native lipoxin A4 is almost 10-fold less potent in this assay. 62 In vivo the comparison is more favorable to ANX-A1, likely for pharmacokinetics reasons. Almost 80% inhibition of cytokine-induced neutrophil migration into a murine dorsal air-pouch was achieved with 10 μg of ANX-A1 per mouse (corresponding to 2 nmol), 17 200 μg of peptide Ac2-26 (corresponding to 65 nmol per mouse), 48 or by 10 μg of 15-epi-16-phenoxy-lipoxin A4 (∼200 nmol). 64

In conclusion, this study has used an immunocytochemical approach to study the alterations in the ANX-A1 biochemical pathways during an on-going process of neutrophil extravasation in vivo. The major indication is that both ANX-A1 protein and mRNA undergo changes in their content and localization when neutrophils adhere to the endothelium of postcapillary venules or immediately after this, when blood-borne cells are in contact with the extracellular matrix. These observations will shed light on the intimate mechanisms regulating the functions of this important protein in the biology of the neutrophilic polymorphonuclear leukocyte.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lynne Scott and Sarah Rodgers (Department of Human Anatomy and Genetics, University of Oxford) for their expert technical assistance; Amilcar S. Damazo for the quantitative analysis of the electron micrographs; and Dr. E. Solito (Inserm unit 332, Institut Cochin de Genetique Moleculaire, Paris) for the supply of human recombinant ANX-A1.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to M. Perretti Ph.D., The William Harvey Research Institute, Pharmacology Division, St. Bartholomew’s and The Royal London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Charterhouse Square, London EC1M 6BQ, UK. E-mail: m.perretti@qmw.ac.uk.

Supported by the Arthritis Research Campaign United Kingdom (grant P0567). R. J. F. is a principal fellow of the Wellcome Trust, and M. P. is a post-doctoral fellow of the Arthritis Research Campaign. S. M. O. was supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo, Brazil.

References

- 1.Epstein FH: Tissue destruction by neutrophils. N Engl J Med 1989, 320:365-376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallin JI, Goldstein IM, Snyderman R: Inflammation: Basic Principles and Clinical Correlates. 1992:pp 1-4 IM Goldstein. New York, Raven Press Ltd., Edited by JI Gallin

- 3.Panés J, Perry M, Granger DN: Leukocyte-endothelial cell adhesion: avenues for therapeutic intervention. Br J Pharmacol 1999, 126:537-550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Von Andrian UH, Hansell P, Chambers JD, Berger EM, Filho IT, Butcher EC, Arfors K-E: l-selectin function is required for β2-integrin-mediated neutrophil adhesion at physiological shear rates in vivo. Am J Physiol 1992, 263:H1034-H1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hatanaka K, Katori M: Detachment of polymorphonuclear leukocytes adhered on venular endothelial cells. Microcirculation Ann 1992, 8:129-130 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mancuso F, Flower RJ, Perretti M: Leukocyte transmigration, but not rolling or adhesion, is selectively inhibited by dexamethasone in the hamster post-capillary venule. Involvement of endogenous lipocortin 1. J Immunol 1995, 155:377-386 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perretti M: Endogenous mediators that inhibit the leukocyte-endothelium interaction. Trends Pharmacol Sci 1997, 18:418-425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raynal P, Pollard HB: Annexins: the problem of assessing the biological role for a gene family of multifunctional calcium- and phospholipid-binding proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta 1994, 1197:63-93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ernst JD: Annexin functions in phagocytic leukocytes. Seaton BA eds. Annexins: Molecular Structure to Cellular Function. 1996, :pp 81-96 TX, R.G. Landes Company, Austin [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosales JL, Ernst JD: Calcium-dependent neutrophil secretion: characterization and regulation by annexins. J Immunol 1997, 159:6195-6202 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vergnolle N, Coméra C, Buéno L: Annexin 1 is overexpressed and specifically secreted during experimentally induced colitis in rats. Eur J Biochem 1995, 232:603-610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vergnolle N, Coméra C, Moré J, Alvinerie M, Buéno L: Expression and secretion of lipocortin 1 in gut inflammation are not regulated by pituitary-adrenal axis. Am J Physiol 1997, 273:R623-R629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith SF, Tetley TD, Guz A, Flower RJ: Detection of lipocortin 1 in human lung lavage fluid: lipocortin degradation as a possible proteolytic mechanism in the control of inflammatory mediators and inflammation. Env Health Perspect 1990, 85:135-144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsao FH, Meyer KC, Chen X, Rosenthal NS, Hu J: Degradation of annexin I in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1998, 18:120-128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pepinsky RB, Sinclair LK, Browning JL, Mattaliano RJ, Smart JE, Chow EP, Falbel T, Ribolini A, Garwin JL, Wallner BP: Purification and partial sequence of a 37-kDa protein that inhibits phospholipase A2 activity from rat peritoneal exudates. J Biol Chem 1986, 261:4239-4246 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perretti M, Croxtall JD, Wheller SK, Goulding NJ, Hannon R, Flower RJ: Mobilizing lipocortin 1 in adherent human leukocytes downregulates their transmigration. Nat Med 1996, 22:1259-1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perretti M, Flower RJ: Modulation of IL-1-induced neutrophil migration by dexamethasone and lipocortin 1. J Immunol 1993, 150:992-999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang Y, Leech M, Hutchinson P, Holdsworth SR, Morand EF: Antiinflammatory effect of lipocortin 1 in experimental arthritis. Inflammation 1997, 21:583-596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang Y, Hutchinson P, Morand EF: Inhibitory effect of annexin I on synovial inflammation in rat adjuvant arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1999, 42:1538-1544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cronstein BN: Adenosine, an endogenous anti-inflammatory agent. J Appl Physiol 1994, 76:5-13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serhan CN, Takano T, Chiang N, Gronert K, Clish CB: Formation of endogenous “antiinflammatory” lipid mediators by transcellular biosynthesis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000, 161:S95-S101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harricane M-C, Caron E, Porte F, Liautard J-P: Distribution of annexin I during non-pathogen or pathogen phagocytosis by confocal imaging and immunogold electron microscopy. Cell Biol Int 1996, 20:193-203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Majeed M, Perskvist N, Ernst JD, Orselius K, Stendahl O: Roles of calcium and annexins in phagocytosis and elimination of an attenuated strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in human neutrophils. Microb Pathog 1998, 24:309-320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perretti M, Christian H, Wheller SK, Aiello I, Mugridge KG, Morris JF, Flower RJ, Goulding NJ: Annexin I is stored within gelatinase granules of human neutrophils and mobilised on the cell surface upon adhesion but not phagocytosis. Cell Biol Int 2000, 24:163-174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borregaard N, Cowland JB: Granules of the human neutrophilic polymorphonuclear leukocyte. Blood 1997, 89:3503-3521 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lim LH, Solito E, Russo-Marie F, Flower RJ, Perretti M: Promoting detachment of neutrophils adherent to murine postcapillary venules to control inflammation: effect of lipocortin 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998, 95:14535-14539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cirino G, Peers SH, Flower RJ, Browning JL, Pepinsky RB: Human recombinant lipocortin 1 has acute local anti-inflammatory properties in the rat paw edema test. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1989, 86:3428-3432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pepinsky RB, Tizard R, Mattaliano RJ, Sinclair LK, Miller GT, Browning JL, Chow P, Burne C, Huang K-S, Pratt D, Watcher L, Hession C, Frey AZ, Wallner B: Five distinct calcium and phospholipid binding proteins share homology with lipocortin I. J Biol Chem 1988, 263:10799-10811 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Di Rosa M, Sorrentino L: The mechanism of the inflammatory effects of carrageenin. Eur J Pharmacol 1968, 4:340-342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tailor A, Tomlinson A, Salas A, Panés J, Granger DN, Flower RJ, Perretti M: Dexamethasone inhibition of leucocyte adhesion to rat mesenteric postcapillary venules: role of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and KC. Gut 1999, 45:705-712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pepinsky RB, Sinclair LK, Dougas I, Liang C-M, Lawton P, Browning JL: Monoclonal antibodies to lipocortin-1 as probes for biological functions. FEBS Lett 1990, 261:247-252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Minghetti L, Nicolini A, Polazzi E, Greco A, Perretti M, Parente L, Levi G: Down-regulation of microglial cyclo-oxygenase-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase by lipocortin 1. Br J Pharmacol 1999, 126:1307-1314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Traverso V, Morris JF, Flower RJ, Buckingham JC: Lipocortin 1 (annexin 1) in patches associated with the membrane of a lung adenocarcinoma cell line and in the cell cytoplasm. J Cell Sci 1998, 111:1405-1418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perretti M, Flower RJ: Measurement of lipocortin 1 levels in murine peripheral blood leukocytes by flow cytometry: modulation by glucocorticoids and inflammation. Br J Pharmacol 1996, 118:605-610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oliani SM, Christian HC, Manston J, Flower RJ, Perretti M: An immunocytochemical and in situ hybridization analysis of annexin 1 expression in rat mast cells: modulation by inflammation and dexamethasone. Lab Invest 2000, 80:1629-1638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taylor AD, Loxley HD, Flower RJ, Buckingham JC: Immunoneutralization of lipocortin 1 reverses the acute inhibitory effects of dexamethasone on the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenocortical responses to cytokines in the rat in vitro and in vivo. Neuroendocrinology 1995, 62:19-31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferreira SH, Cunha FQ, Lorenzetti BB, Michelin MA, Perretti M, Flower RJ, Poole S: Role of lipocortin-1 in the analgesic actions of glucocorticoids. Br J Pharmacol 1997, 121:883-888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trembleau A, Bloom FE: Enhanced sensitivity for light and electron microscopic in situ hybridization with multiple simultaneous non-radioactive oligodeoxynucleotide probes. J Histochem Cytochem 1995, 43:829-841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berry DA, Lindgren BW: Statistics: Theory and Methods. 1990. Brooks/Cole Publishing Company, Pacific Grove

- 40.Errasfa M, Russo-Marie F: A purified lipocortin shares the anti-inflammatory effect of glucocorticosteroids in vivo in mice. Br J Pharmacol 1989, 97:1051-1058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perretti M: Lipocortin 1 and chemokine modulation of granulocyte and monocyte accumulation in experimental inflammation. Gen Pharmacol 1998, 31:545-552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fava RA, McKanna J, Cohen S: Lipocortin I (p35) is abundant in a restricted number of differentiated cell types in adult organs. J Cell Physiol 1989, 141:284-293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Francis JW, Balazovich KJ, Smolen JE, Margolis DI, Boxer LA: Human neutrophil annexin I promotes granule aggregation and modulates Ca2+-dependent membrane fusion. J Clin Invest 1992, 90:537-544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goulding NJ, Godolphin JL, Sharland PR, Peers SH, Sampson M, Maddison PJ, Flower RJ: Anti-inflammatory lipocortin 1 production by peripheral blood leucocytes in response to hydrocortisone. Lancet 1990, 335:1416-1418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Christmas P, Callaway J, Fallon J, Jonest J, Haigler HT: Selective secretion of annexin I, a protein without a signal sequence, by the human prostate gland. J Biol Chem 1991, 266:2499-2507 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raynal P, van Bergen PMP, Hullin F, Ragab-Thomas JMF, Fauvel J, Verkleij A, Chap H: Morphological and biochemical evidence for partial nuclear localization of annexin I in endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Comm 1992, 186:432-439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Browning JL, Ward MP, Wallner BP, Pepinsky RB: Studies on the structural properties of lipocortin-1 and the regulation of its synthesis by steroids. Melli M Parente L eds. Cytokines and Lipocortins in Inflammation and Differentiation. 1990, :pp 27-45 Wiley-Liss, New York [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Perretti M, Ahluwalia A, Harris JG, Goulding NJ, Flower RJ: Lipocortin-1 fragments inhibit neutrophil accumulation and neutrophil-dependent edema in the mouse: a qualitative comparison with an anti-CD11b monoclonal antibody. J Immunol 1993, 151:4306-4314 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wallner BP, Mattaliano RJ, Hession C, Cate RL, Tizard R, Sinclair LK, Foeller C, Chow EP, Browning JL, Ramachandran KL, Pepinsky RB: Cloning and expression of human lipocortin, a phospholipase A2 inhibitor with potential anti-inflammatory activity. Nature 1986, 320:77-81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Traverso V, Christian HC, Morris JF, Buckingham JC: Lipocortin 1 (annexin 1): a candidate paracrine agent localized in pituitary folliculo-stellate cells. Endocrinology 1999, 140:4311-4319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perretti M, Wheller SK, Flower RJ, Wahid S, Pitzalis C: Modulation of cellular annexin I in human leukocytes infiltrating DTH skin reactions. J Leukoc Biol 1999, 65:583-589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seemann J, Weber K, Osborn M, Parton RG, Gerke V: The association of annexin I with early endosomes is regulated by Ca2+ and requires an intact N-terminal domain. Mol Biol Cell 1996, 7:1359-1374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peers SH, Smillie F, Elderfield AJ, Flower RJ: Glucocorticoid- and non-glucocorticoid induction of lipocortins (annexins) 1 and 2 in rat peritoneal leucocytes in vivo. Br J Pharmacol 1993, 108:66-72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Movitz C, Sjolin C, Dahlgren C: Cleavage of annexin I in human neutrophils is mediated by a membrane-localized metalloprotease. Biochim Biophys Acta 1999, 1416:101-108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chuah S, Pallen CJ: Calcium-dependent and phosphorylation-stimulated proteolysis of lipocortin I by an endogenous A431 cell membrane protease. J Biol Chem 1989, 264:21160-21166 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goulding NJ, Guyre PM: Regulation of inflammation by lipocortin 1. Immunol Today 1992, 13:295-297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Solito E, de Coupade C, Parente L, Flower RJ, Russo-Marie F: Human annexin 1 is highly expressed during differentiation of the epithelial cell line A549: involvement of nuclear factor interleukin 6 in phorbol ester induction of annexin 1. Cell Growth Differ 1998, 9:327-336 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Solito E, de Coupade C, Parente L, Flower RJ, Russo-Marie F: IL-6 stimulates annexin 1 expression and translocation and suggests a new biological role as class II acute phase protein. Cytokine 1998, 10:514-521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Utsunomiya I, Nagai S, Oh-Ishi S: Sequential appearance of IL-1 and IL-6 activities in rat carrageenin-induced pleurisy. J Immunol 1991, 147:1803-1809 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xing Z, Kirpalani H, Torry D, Jordana M, Gauldie J: Polymorphonuclear leukocytes as a significant source of tumor necrosis factor-α in endotoxin-challenged lung tissue. Am J Pathol 1993, 143:1009-1015 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Perretti M, Wheller SK, Choudhury Q, Croxtall JD, Flower RJ: Selective inhibition of neutrophil function by a peptide derived from the lipocortin 1 N-terminus. Biochem Pharmacol 1995, 50:1037-1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Filep JG, Zouki C, Petasis NA, Hachicha M, Serhan CN: Anti-inflammatory actions of lipoxin A4 stable analogues are demonstrable in human whole blood: modulation of leukocyte adhesion molecules and inhibition of neutrophil-endothelial interactions. Blood 1999, 94:4132-4142 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zouchi C, Oullet S, Filep JG: The anti-inflammatory peptides, antiflammins, regulate the expression of adhesion molecules on human leukocytes and prevents neutrophil adhesion to endothelial cells. FASEB J 2000, 14:572-580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Clish CB, O’Brien JA, Gronert K, Stahl GL, Petasis NA, Serhan CN: Local and systemic delivery of a stable aspirin-triggered lipoxin prevents neutrophil in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999, 96:8247-8252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]