Abstract

We report the crystal structure of the catalytic domain of human ADAR2, an RNA editing enzyme, at 1.7 angstrom resolution. The structure reveals a zinc ion in the active site and suggests how the substrate adenosine is recognized. Unexpectedly, inositol hexakisphosphate (IP6) is buried within the enzyme core, contributing to the protein fold. Although there are no reports that adenosine deaminases that act on RNA (ADARs) require a cofactor, we show that IP6 is required for activity. Amino acids that coordinate IP6 in the crystal structure are conserved in some adenosine deaminases that act on transfer RNA (tRNA) (ADATs), related enzymes that edit tRNA. Indeed, IP6 is also essential for in vivo and in vitro deamination of adenosine 37 of tRNAala by ADAT1.

One form of RNA editing is catalyzed by adenosine deaminases that act on RNA (ADARs), a family of enzymes that deaminate adenosine to form inosine in double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) (Fig. 1A) (1). ADARs are important for proper neuronal function (2–4) and also are implicated in the regulation of RNA interference (RNAi) (5–7). Inosine is recognized as guanosine by most cellular proteins and the translation machinery, and it pairs most stably with cytidine. Therefore, editing of RNA can alter a codon, create splice sites, and change its structure. The latter occurs when an AU base pair is changed to an IU mismatch and may be important for the effects of ADARs on the RNAi pathway.

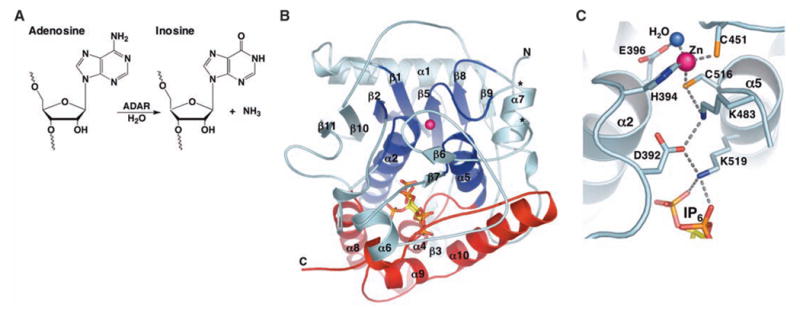

Fig. 1.

(A) ADAR catalyzed hydrolytic deamination of adenosine to inosine in dsRNA. (B) Ribbon model of hADAR2-D. The active-site zinc atom is represented by a magenta sphere. The N-terminal α/β domain (residues 306 to 620) is colored cyan, with the region that shares structural similarity with CDA and TadA colored dark blue (deamination motif; residues 350 to 375, 392 to 416, 439 to 455, 514 to 525, and 542 to 551). The C-terminal helical domain (residues 621 to 700), which with contributions from the deamination motif makes the major contacts to IP6 (ball and stick), is colored red. Ends of the disordered segment (residues 462 to 473) are indicated with asterisks. (C) Residue interactions at the active site. Shown are the zinc ion, coordinating residues (H394, C451, and C516), the nucleophilic water (blue sphere), and the proposed proton-shuttling residue, E396. The hydrogen-bond relay that connects the active site to the IP6 is also indicated. Single-letter abbreviations for amino acid residues are defined in (42).

ADARs from all organisms have a common domain structure consisting of one to three dsRNA binding motifs (dsRBMs) near the N terminus, followed by a conserved C-terminal catalytic domain (1, 8). Human ADAR2 (hADAR2) contains two dsRBMs, and its best characterized substrates are the pre-mRNAs of glutamate and serotonin receptors (9, 10). Editing of codons within these RNAs leads to altered amino acids and generates receptors with altered function. hADAR2 also edits its own message to create a new splice site (11). Purified hADAR2 deaminates substrates in vitro (12) in the absence of any added cofactors, and deletions of N-terminal sequences, including dsRBM1, result in an active protein that accurately edits an RNA substrate (13). In addition, we found that a protein consisting of only the catalytic deaminase domain of hADAR2 (hADAR2-D, residues 299 to 701) (fig. S1A) was active in vitro, although it deaminates RNA less efficiently than full-length hADAR2 (fig. S1B).

The structure of the ADAR2 catalytic domain

To better understand the ADAR mechanism, we crystallized hADAR2-D. The structure (PDB code 1ZY7) was determined by multiple isomorphous replacement and refined at 1.7 Å resolution to an Rfactor of 17.4% and Rfree of 20.7% (14). The asymmetric unit includes 669 water molecules, one sulfate ion, and two hADAR2-D molecules that are essentially identical [root mean square deviation (RMSD) = 0.28 Å for 358 pairs of Cα atoms]. The refined hADAR2-D model contains residues 306 to 461 and 474 to 700 (462 to 473 are disordered), one zinc ion, and one molecule of inositol hexakisphosphate (IP6).

The protein adopts a roughly spherical 40 Å diameter structure (Fig. 1B) that, consistent with sizing chromatography of hADAR2-D and equilibrium ultracentrifugation of the full-length hADAR2, appears monomeric in the crystal. The active site is indicated by an ordered zinc ion that coordinates a water molecule that presumably displaces ammonia during the deamination reaction. Coordination of the zinc ion by H394, C451, and C516, and hydrogen bonding of the water molecule by E396 (Fig. 1C), is essentially identical to the geometry seen at the catalytic centers of cytidine deaminase (CDA) (15) and TadA (16), a member of the ADAT2 (adenosine deaminase that acts on tRNA 2) family. This similarity was predicted earlier on the basis of equivalent chemistry and sequence conservation of the four residues that coordinate zinc and water (17, 18).

Superposition of zinc, water, and coordinating residues was used as the starting point to identify residues of hADAR2-D that were structurally equivalent to those in CDA and TadA (PDB codes 1CTU and 1WWR, respectively). Inspection shows that 77 residues (RMSD = 3.05 Å on Cα atoms) form a structurally conserved “deamination motif” comprising two helices (α2 and α5), four strands (β1, β2, β5, and β8), and connecting loops (Fig. 1B, dark blue). Other hADAR2-D residues do not have structural equivalents in CDA and TadA (Fig. 2A). Further emphasizing the large evolutionary separation between these enzymes, only four of the deamination motif residues have conserved identities in all three enzymes (excluding zinc/water ligands).

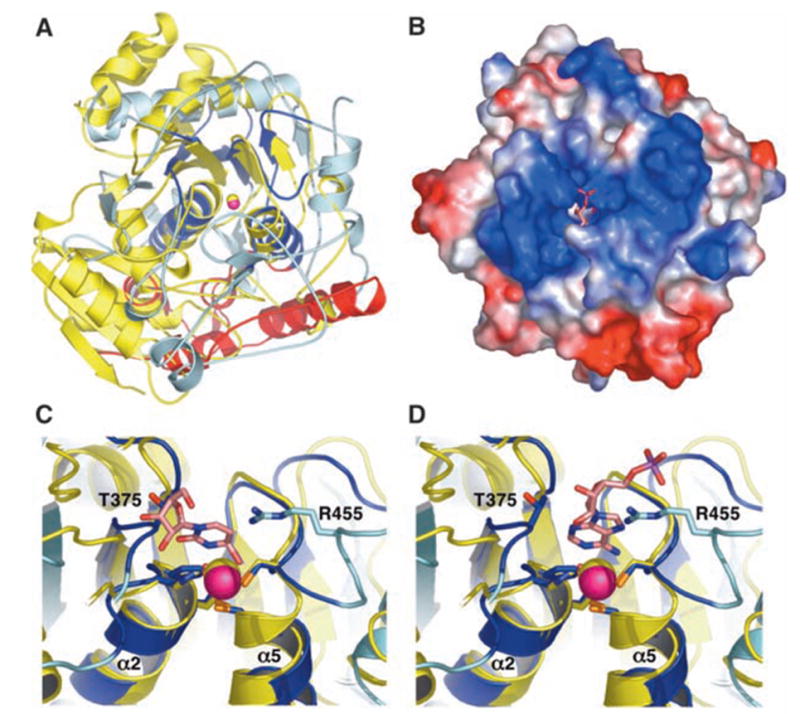

Fig. 2.

(A) Superposition of Escherichia coli CDA (yellow) and hADAR2-D (color scheme as in Fig. 1B) shows that these structures are highly diverged. View direction is similar to Fig. 1B. The only hADAR2-D residues that have structural equivalents in CDA are dark blue. (B) Electrostatic surface potential reveals a highly basic (blue) region flanking the active site. View direction is from the top of (A). The modeled AMP (pink) and catalytic zinc ion (magenta, partially occluded) are visible in the active site cleft. (C) Superposition of the hADAR2 and CDA active sites. Zebularine (pink) bound to CDA would clash with the loop containing T375 of hADAR2-D. (D) Docking of AMP (pink) in the same chemically equivalent orientation as zebularine would not clash with the T375 loop. Single-letter abbreviations for amino acid residues are defined in (42).

The active site of ADAR2

The site of nucleophilic attack during the ADAR reaction (C6 of adenine) lies deep in the major groove of the dsRNA substrate. Because this site is inaccessible to an enzyme, ADARs may use a base-flipping mechanism (19, 20) like other enzymes that modify double-stranded polynucleotides (21). Consistent with this scenario, the catalytic zinc center is located in a deep pocket in the enzyme surface that is surrounded by positive electrostatic potential that likely serves as the dsRNA binding site (Fig. 2B). In contrast, TadA uses an alternative mechanism of substrate selection that probably involves recognition of the anticodon stem/loop of tRNA (16).

To model binding of substrate, we overlapped the structure of a CDA-zebularine (cytidine analog inhibitor) complex (15) onto the hADAR2 structure and built the adenosine monophosphate (AMP) portion of an ADAR substrate to maintain the same catalytic geometry. In this simple overlap based on zinc ion and coordinating residues, the zebularine ribose clashes with the hADAR2 loop containing T375 (Fig. 2C), thereby providing a plausible explanation for why ADARs do not deaminate cytidine. The steric clash is absent with AMP because of the additional distance afforded by the purine ring (Fig. 2D). The proposed AMP-binding geometry requires repositioning of the hADAR2 R455 side chain, although this could be accomplished through minor rearrangements that may occur upon dsRNA binding.

Comparison of the ADAR and CDA/TadA structures reveals an important difference in the arrangement of the two cysteine residues that coordinate zinc (fig. S5). As often found in zinc-dependent enzymes (22, 23), the two cysteines of CDA and TadA are located in a Cys-X-X-Cys motif at the N terminus of a helix. The first cysteine forms hydrogen bonds with two main-chain amide NH groups at the helix terminus; this likely contributes to catalysis by increasing the positive character of the zinc ion and nucleophilicity of the water molecule (24). In ADAR2, however, C451 and C516 are separated by a 64-residue loop, and hydrogen bonding to main-chain atoms is reduced to a single bond between C451 and the amide NH group of C516. However, a second hydrogen bond is observed between C516 and K483 (Fig. 3A and fig. S5), and thus ADARs may have evolved a compensating interaction; K483 is conserved in ADAR sequences but not seen in CDA or TadA.

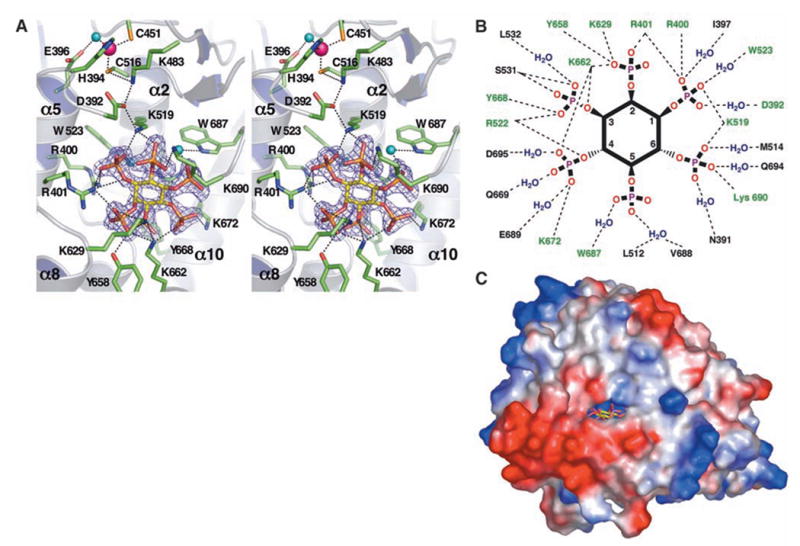

Fig. 3.

(A) Stereo image of the active site and IP6 binding site in hADAR2-D. The zinc ion (magenta sphere) and E396 are coordinating the nucleophilic water (aqua sphere). The hydrogen bond relay between the zinc and IP6 (yellow sticks) is shown as dashes, as are hydrogen bonds between conserved residues (green sticks) and IP6. IP6 interactions with W523 and W687 are mediated by water (aqua spheres). The 2Fo – Fc (where Fo is the observed structure factor and Fc is the calculated structure factor) difference electron density map demonstrating the presence of the bound IP6 is contoured at 4σ. Because IP6 is nearly buried, part of the protein molecule in the foreground has been cut away for clarity. (B) Schematic diagram of residues that hydrogen-bond with IP6 directly or through one water molecule. H bonds, dashed lines; conserved residues, green. For clarity, the inositol ring is depicted as planar, although it actually binds in the ‘‘chair’’ conformation. (C) Only view from which IP6 (yellow) is visible from the protein exterior in a surface representation. The ‘‘window’’ measures 8.4 Å by 4.6 Å between van der Waal’s surfaces. Single-letter abbreviations for amino acid residues are defined in (42).

Inositol hexakisphosphate binds in the core of the catalytic domain

One side of the deamination motif of hADAR2 contributes to a cavity, not found in CDA or TadA, that is formed mainly by C-terminal elements (Fig. 1B, red) and buries the IP6 molecule and 29 associated water molecules. The identity of IP6 was suggested by the strong, distinctive electron density (Fig. 3A and fig. S3) and the local electrostatic interactions, and was confirmed by (+) ion electrospray mass spectrometry [observed molecular weight (MW) of IP6 in complex with the protein = 660.0 Da; calculated MW = 659.9 Da] (14). IP6 is an abundant inositol polyphosphate implicated in many cellular functions, including RNA export, DNA repair, endocytosis, and chromatin remodeling (25–29). Intriguingly, the compound is reported to affect neuronal AMPA receptors (30), whose messages are edited by ADAR2 (9).

The IP6 cavity is extremely basic and lined with many arginine and lysine residues (R400, R401, and R522 and K519, K629, K662, K672, and K690), as well as W523, W687, Y658, and Y668 (Fig. 3, A and B). Most of these residues are invariant among catalytically active ADARs, as well as in the ADAT1 family of enzymes, which deaminate A37 of certain tRNAs. (The ADAT2 family, of which TadA is a member, is distinct from ADAT1 and does not have theIP6 binding pocket or its conserved residues.)

IP6 was not added during purification or crystallization but must have been acquired during expression of the human ADAR2-D protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which like other eukaryotes has pools of IP6 (31). The presence of IP6 in the purified protein therefore indicates a tight association, consistent with the extensive array of hydrogen bonds formed with conserved side chains (Fig. 3B) and the almost completely buried environment (Fig. 3C). The structure suggests that hADAR2 will be non-functional in the absence of IP6, a view that is supported by experiments described below.

IP6 is required for ADAR2 activity

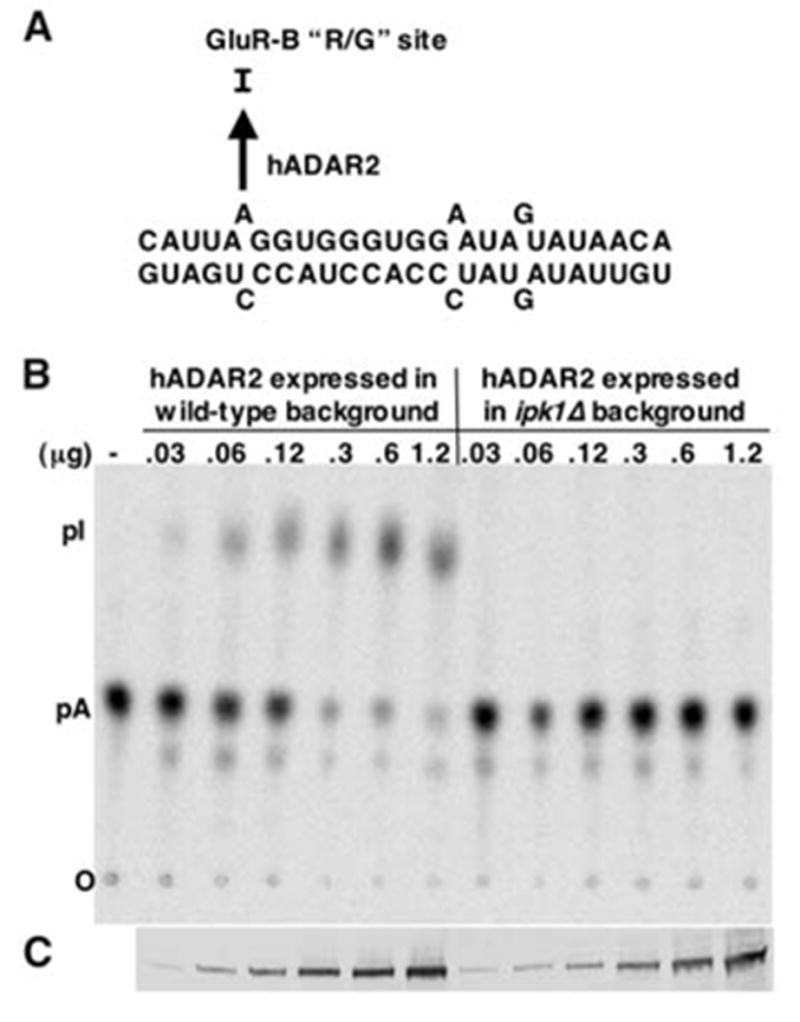

In S. cerevisiae, the last step in the synthesis of IP6 is the phosphorylation of IP5 by Ipk1p, and yeast harboring a deletion of IPK1 are viable but fail to produce IP6 (25). To test for the IP6 requirement of hADAR2, we expressed the protein in ipk1Δ yeast cells and compared its activity to hADAR2 expressed in the same strain but containing the IPK1 gene. As substrate, we used a 27-base-pair RNA that mimics the natural arginine/glycine (R/G) editing site of the glutamate receptor B (gluR-B) pre-mRNA (Fig. 4A) and that is efficiently edited by hADAR2 in vitro (20). IP6 was required for hADAR2 activity (Fig. 4B), because there was no editing of this RNA by protein expressed in the ipk1Δ mutant. Using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), we determined that hADAR2 mRNA was expressed at the same levels in the wild-type and ipk1Δ mutant strains, although the amount of hADAR2 protein was lower by a factor of 5 to 10 in the mutant strain. Western blots were performed to determine the amount of hADAR2 protein in each extract by comparison with a standard curve generated with known amounts of purified, histidine-tagged protein (R2D, an N-terminal truncation of hADAR2) (13). This information was used to normalize amounts of hADAR2 used for the in vitro assays, and a Western blot confirmed that amounts of hADAR2 in wild-type and mutant editing reactions were similar (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

(A) The 27-mer R/G site RNA substrate used to assay hADAR2 editing activity. (B) Editing of the R/G site RNA by hADAR2 expressed in wild-type or ipk1Δ yeast. The R/G site adenosine was labeled with 32P and incubated with increasing concentrations of expressed hADAR2 in extracts. Reacted RNA was treated with nuclease P1, the resulting 5′ nucleotide monophosphates separated by thin-layer chromatography (TLC), and the plate exposed to a PhosphorImager screen. The amount of hADAR2 in each extract was determined by Western blotting, and extract was added to give the final ADAR2 concentrations as indicated. (C) Western blot showing the amount of hADAR2 in each reaction. Single-letter abbreviations for amino acid residues are defined in (42).

IP6 is required for tRNA editing by the ADAT1 family of deaminases

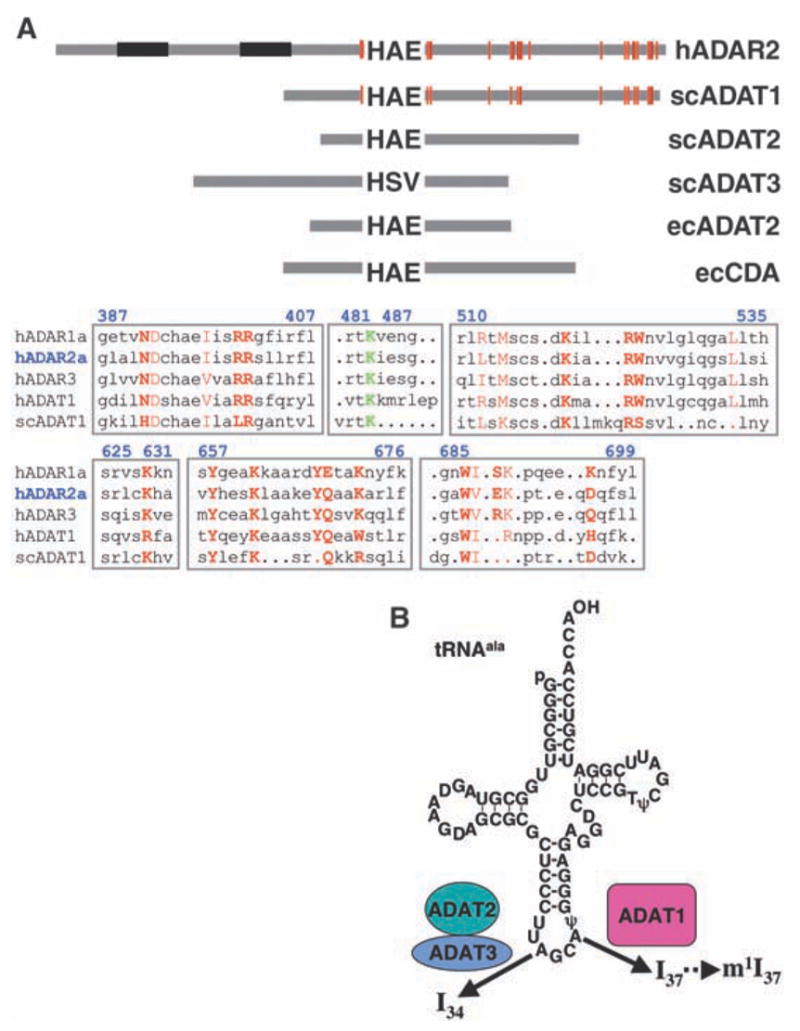

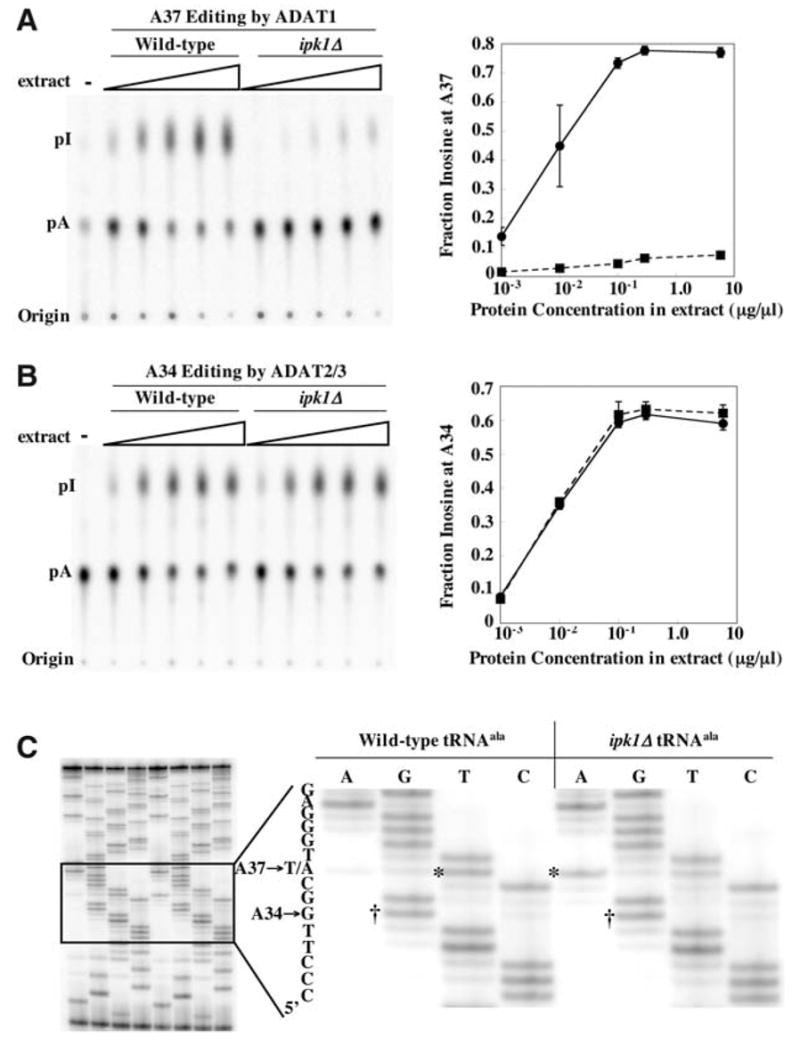

ADATs are another class of enzymes that deaminate adenosine to generate inosine in RNA. These enzymes contain only the catalytic domain and deaminate tRNAs at adenosines 34 and 37 (A34 and A37) (18). On the basis of their sequences and substrates, there are three types of ADATs in eukaryotes. ADAT1 deaminates A37 of tRNAala (32), and the resulting inosine is subsequently methylated at N1 in a reaction requiring a different enzyme and S-adenosylmethionine (33). ADAT2 and ADAT3 form a heterodimer that deaminates A34 of various tRNAs and, consistent with the fact that this is the wobble position, unlike ADAT1, these enzymes are essential (32, 34). By aligning enzyme sequences, we noted that residues observed to coordinate IP6 in the hADAR2 crystal structure were conserved in the ADAT1 family but not in the ADAT2 or ADAT3 families (Fig. 5A and fig. S6). To test the consequent prediction that ADAT1, but not ADAT2/3, requires IP6, we monitored activity of endogenous ADAT in extracts prepared from S. cerevisiae wild-type or ipk1Δ strains. S. cerevisiae tRNAala is deaminated at A34, as well as A37, and provided an ideal substrate with which to assay the IP6 requirement of the different ADATs (Fig. 5B). We observed that in vitro editing of A37 by ADAT1 is severely reduced in extract prepared from the ipk1Δ strain compared with extract from a wild-type strain (Fig. 6A). In contrast, there was no difference for in vitro editing of A34 by the ADAT2/ADAT3 heterodimer in the mutant versus the wild-type extract (Fig. 6B). To confirm that the lack of activity in the ipk1Δ strain derived from a lack of IP6 rather than a molecule downstream in the pathway, we tested ADAT1 activity in extracts prepared from a kcs1Δ mutant (fig. S7). The KCS1 gene product is downstream of IPK1 in the inositol polyphosphate synthesis pathway and phosphorylates IP6 to form the pyrophosphate-containing IP7 (5PP-IP5) (35). The kcs1Δ mutation had no effect on the A37 editing activity of ADAT1, which indicates that the editing defect in the ipk1Δ mutant is due to the IP6 deficiency.

Fig. 5.

(A) Schematic diagram showing the relative lengths and domain structures of hADAR2 and family members from S. cerevisiae (sc) and E. coli (ec). Proteins are anchored at the invariant zinc-coordinating histidine (H). Residues that coordinate IP6 are red lines; double-stranded RNA binding motifs are in black. Alignments for regions surrounding the residues that coordinate IP6 in hADAR2 are shown below, with blue numbering corresponding to hADAR2. IP6 coordinating residues are in red, with side-chain contacts in bold. Residues N391, W523, Q669, W687, E689, and D695 are water-mediated contacts. The conserved K483, which is part of a hydrogen-bond relay from IP6 to the active site zinc, is shown in green. Sequences diverge considerably in the region surrounding K483; the alignment shown was chosen because the conserved lysine of various subfamilies is aligned with K483 of hADAR2. Notably, the IP6 coordinating residues are found in ADAR3, which suggests that inefficient IP6 binding is not the reason this enzyme lacks deaminase activity (43). (B) The tRNAala substrate used in this study showing the sites of modification by the ADAT proteins. Single-letter abbreviations for amino acid residues are defined in (42).

Fig. 6.

(A) Editing of tRNAala A37 in vitro by extracts of wild-type or ipk1Δ yeast strains. tRNAala, labeled with 32P at A37, was incubated with increasing amounts of yeast extract protein, as indicated (14). Reacted RNA was processed as in Fig. 4B, and nuclease P1 products were separated by TLC (left). The fraction of inosine in each lane was quantified, and the average of three determinations was plotted as a function of protein concentration (right; error bars, standard deviation; when error was very small, error bars are obscured by data point symbols). Solid line, editing by ADAT1 from wild-type extracts; dashed line, editing by ADAT1 from ipk1Δ extracts. (B) As in (A) but showing editing of A34-labeled tRNAala. Solid line, editing by ADAT2/3 from wild-type extracts; dashed line, editing by ADAT2/3 from ipk1Δ extracts. (C) Editing of endogenous tRNA in vivo. tRNA was prepared from wild-type or ipk1Δ strains, reverse transcribed, and amplified by PCR. PCR products were sequenced using dideoxy nucleotide triphosphates and a 32P-labeled primer that anneals to the nontemplate strand at the 5′ end of the gene. The right panel shows an expanded view of the sequencing gel shown on the left. The dideoxy sequencing lanes are indicated at the top of each lane, and the 5′ to 3′ sequence to the left of the gel is read from bottom to top. Bands corresponding to A34 to G editing in the wild-type and ipk1Δ tRNAs are labeled with daggers, and the band representing the A37 site that is not edited in the ipk1Δ tRNA is labeled with an asterisk. Consistent with the observation of residual activity in the mutant extract in vitro (A), some editing of A37 in the mutant extract occurs.

The existence of the ipk1Δ mutant, and the fact that S. cerevisiae tRNAala is deaminated at both A34 and A37, provided a facile system for analyzing the in vivo requirement for IP6. RNA was prepared from wild-type or ipk1Δ cells, tRNAala was amplified using RT-PCR, and the RT-PCR product was sequenced (Fig. 6C). Because inosine is read as guanosine by reverse transcriptase, edited adenosines were identified as guanosine in the dideoxy sequencing reaction. Consistent with the in vitro data, we observed that A34 is edited with equal efficiency in the wild-type and mutant strain, but A37 is edited much less efficiently in the ipk1Δ strain (Fig. 6C). A37 in the wild-type strain is read as a thymidine, presumably due to N1-methylinosine at position 37. m1I, like m1A, may pair with reduced specificity in the reverse transcription reaction, explaining the presence of a T in the PCR product (36).

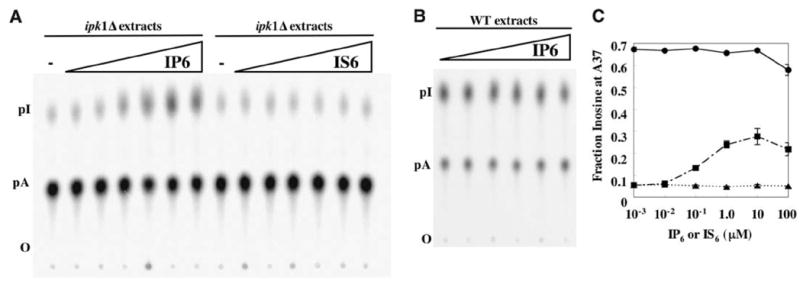

In the crystal structure of hADAR2, IP6 binds and fills an extremely basic hole, with the center of the inositol ring more than 10 Å from the protein surface. Thus, it seems possible that ADAR2 and, by analogy, ADAT1, are unstable without IP6. In this regard we wondered about the nature of ADAT1 expressed in the ipk1Δ mutant. Was this protein trapped in an irreversible inactive state or forming a folding intermediate that could bind IP6 to achieve its active conformation? To explore this question, we tested whether the addition of IP6 to extracts prepared from the ipk1Δ mutant could recover ADAT1 activity. When added to extracts prepared from the ipk1Δ strain, IP6 recovered activity to ~50% of wild-type (Fig. 7, A and C), which suggests that the protein does not require IP6 during its synthesis and the initial stages of folding. As expected, the addition of IP6 to wild-type extract had no effect, because these cells are capable of synthesizing IP6 (Fig. 7, B and C). To test for the specific requirement for IP6 by ADAT1, we performed a similar experiment, except we substituted inositol hexakissulfate (IS6) for IP6. Despite its similar charge and structure, IS6 does not recover ADAT1 activity when added to ipk1Δ extracts (Fig. 7A). This suggests that the enzyme specifically requires IP6 for function and can discriminate between the minor differences in phosphate/sulfate chemistry (e.g., the protonation state).

Fig. 7.

(A) Addition of IP6, but not IS6, rescued ADAT1 activity in extracts prepared from ipk1Δ yeast. Wild-type or ipk1Δ protein extract (0.1 μg/μl) was incubated with IP6 or IS6 for 15 min at 30°C before the addition of A37-labeled tRNAala. IP6 and IS6 concentrations were 10-fold dilutions from 100 μM to 10−3 μM. The tRNA was processed as described in Fig. 4B. (B) Addition of IP6 had no effect on ADAT1 activity in wild-type extracts using the reaction conditions of (A). Without the addition of IP6, wild-type extracts gave 70% A to I conversion. (C) The average fraction of inosine produced in three experiments each of (A) and (B) plotted as a function of IP6 or IS6 concentration; error bars show the standard deviation (small error bars are obscured by the data point symbol). Circles, ADAT1 activity from wild-type extracts with IP6 added; squares, activity of ipk1Δ extracts with IP6; triangles, activity of ipk1Δ extracts with IS6.

So far, we have been unable to rescue the activity of hADAR2 expressed in the ipk1Δ by adding IP6. Possibly, native S. cerevisiae ADAT1, but not the heterologous hADAR2, is associated with a host chaperone in the extract that promotes refolding in the presence of IP6. Alternatively, this result may hint at interesting differences between the two enzymes in IP6 accessibility. Such a difference might explain why assays of ADAT1 in ipk1Δ extracts show a small (~5%) amount of A37 deamination at the highest concentrations of extract (Fig. 6A), whereas ADAR2 expressed in this strain shows no residual activity. If the IP6 binding site in ADAT1 were more accessible than that of ADAR2, it might bind a noncognate inositol polyphosphate, such as IP5, to allow a low level of activity.

Discussion

Burial of IP6 may reflect a novel way of using an available cellular component to define and stabilize a protein fold. This would be analogous to the use of “structural” metal ions in stabilizing the fold of metalloproteins. To our knowledge, this represents the first example of a protein using IP6 for this purpose. Other protein structures with bound IP6 have been reported, such as deoxyhemoglobin (37) and the clathrin adaptor complex AP2 (38); however, unlike ADAR2-D, in these cases the IP6 molecule is not extensively buried and does not appear to dramatically stabilize the overall structure.

In addition to the structural requirement, IP6 may play a subtle role in modulating catalytic efficiency by indirectly ordering the side chain of K483. Two of the IP6 phosphate groups approach within 10 Å of the catalytic zinc ion and are indirectly coordinated to zinc by a chain of hydrogen-bonded residues that includes K519, D392, and K483 (Fig. 3A). These residues are conserved among active ADARs, and K483 may contribute to tuning the pKa of the nucleophilic water molecule through its interaction with C516 (Fig. 3A).

Sequence alignments indicate that ADAT1 enzymes are the evolutionary link between the other family members, ADAT2/3 (including TadA) and ADARs (18). ADAT1 apparently diverged from the ADAT2/3 family by acquiring the ability to bind IP6, followed by the acquisition of one or more dsRBMs to generate an ADAR. ADAT1 may have evolved an IP6 binding function as a means of regulation. IP6 accumulates in yeast during times of stress (39) and thus could lead to increased ADAT1 activity, and consequently to an increased conversion of A37 to N1-methylinosine. Modification of position 37 is predicted to increase fidelity of protein synthesis by stabilizing the codon-anticodon interaction (40), and thus yeast may use this modification to fine-tune protein synthesis in response to environmental conditions.

Once established as a means of regulation for ADAT1, metazoa may have extended this regulatory mode for use in ADARs, which perform important roles in the nervous system and display changes in activity during development (41). For example, a feedback mechanism could act through phospholipase C in response to hormones such as serotonin. Upon binding of serotonin to its 5-HT2c receptor, phospholipase C is activated to cleave phosphatidyl inositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to form the second messengers diacylglycerol and inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3), which is subsequently phosphorylated to form IP6. 5-HT2C receptor mRNA is edited at five distinct sites by ADAR2, with the more extensively modified receptors requiring greater concentrations of serotonin to stimulate phospholipase C. It is tempting, therefore, to speculate that the serotonin-induced production of IP6 causes increased production of active ADAR2, which in turn edits mRNA to attenuate the serotonin signaling pathway.

The structure of the hADAR2 catalytic domain reveals the active site architecture of a zinc-catalyzed deamination reaction and suggests how ADARs discriminate between cytidine and adenosine residues. The presence of IP6 in the protein core implied an unexpected requirement for this cofactor in ADARs, which was confirmed by assaying the RNA editing activity of enzymes lacking IP6. The finding that IP6 is required for ADAR and ADAT activity suggests many interesting links between RNA editing and diverse processes such as cell signaling and translation, thus setting the stage for future studies.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/309/5740/1534/

DC1

Materials and Methods

References

References and Notes

- 1.Bass BL. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:817. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Higuchi M, et al. Nature. 2000;406:78. doi: 10.1038/35017558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palladino MJ, Keegan LP, O’Connell MA, Reenan RA. Cell. 2000;102:437. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tonkin LA, et al. EMBO J. 2002;21:6025. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knight SW, Bass BL. Mol Cell. 2002;10:809. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00649-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scadden AD, Smith CW. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:1107. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tonkin LA, Bass BL. Science. 2003;302:1725. doi: 10.1126/science.1091340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maas S, Rich A, Nishikura K. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:1391. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R200025200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melcher T, et al. Nature. 1996;379:460. doi: 10.1038/379460a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burns CM, et al. Nature. 1997;387:303. doi: 10.1038/387303a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rueter SM, Dawson TR, Emeson RB. Nature. 1999;399:75. doi: 10.1038/19992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Connell MA, Gerber A, Keller W. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:473. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.1.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Macbeth MR, Lingam AT, Bass BL. RNA. 2004;10:1563. doi: 10.1261/rna.7920904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science Online.

- 15.Betts L, Xiang S, Short SA, Wolfenden R, Carter CW., Jr J Mol Biol. 1994;235:635. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuratani M, et al. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414541200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim U, Wang Y, Sanford T, Zeng Y, Nishikura K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerber AP, Keller W. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26:376. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01827-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polson AG, Bass BL. EMBO J. 1994;13:5701. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06908.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stephens OM, Yi-Brunozzi HY, Beal PA. Biochemistry. 2000;39:12243. doi: 10.1021/bi0011577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng X, Roberts RJ. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:3784. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.18.3784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwabe JW, Klug A. Nat Struct Biol. 1994;1:345. doi: 10.1038/nsb0694-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wedekind JE, Frey PA, Rayment I. Biochemistry. 1995;34:11049. doi: 10.1021/bi00035a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carlow DC, Carter CW, Jr, Mejlhede N, Neuhard J, Wolfenden R. Biochemistry. 1999;38:12258. doi: 10.1021/bi990819t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.York JD, Odom AR, Murphy R, Ives EB, Wente SR. Science. 1999;285:96. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5424.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanakahi LA, West SC. EMBO J. 2002;21:2038. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.8.2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoy M, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:6773. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shen X, Xiao H, Ranallo R, Wu WH, Wu C. Science. 2003;299:112. doi: 10.1126/science.1078068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steger DJ, Haswell ES, Miller AL, Wente SR, O’Shea EK. Science. 2003;299:114. doi: 10.1126/science.1078062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valastro B, et al. Hippocampus. 2001;11:673. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raboy V. Phytochemistry. 2003;64:1033. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(03)00446-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerber A, Grosjean H, Melcher T, Keller W. EMBO J. 1998;17:4780. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grosjean H, et al. Biochimie. 1996;78:488. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(96)84755-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerber AP, Keller W. Science. 1999;286:1146. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saiardi A, Caffrey JJ, Snyder SH, Shears SB. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:24686. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002750200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kroger M, Singer B. Biochemistry. 1979;18:3493. doi: 10.1021/bi00583a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arnone A, Perutz MF. Nature. 1974;249:34. doi: 10.1038/249034a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Collins BM, McCoy AJ, Kent HM, Evans PR, Owen DJ. Cell. 2002;109:523. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00735-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ongusaha PP, Hughes PJ, Davey J, Mitchell RH. Biochem J. 1998;335:671. doi: 10.1042/bj3350671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grosjean H, Houssier C, Romby P, Marquet R. In: Modification and Editing of RNA. Grosjean H, Benne R, editors. ASM Press; Washington, DC: 1998. pp. 113–134. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lomeli H, et al. Science. 1994;266:1709. doi: 10.1126/science.7992055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Single-letter abbreviations for the amino acid residues are as follows: A, Ala; C, Cys; D, Asp; E, Glu; F, Phe; G, Gly; H, His; I, Ile; K, Lys; L, Leu; M, Met; N, Asn; P, Pro; Q, Gln; R, Arg; S, Ser; T, Thr; V, Val; W, Trp; and Y, Tyr.

- 43.Chen CX, et al. RNA. 2000;6:755. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200000170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.We thank R. Schackmann for synthesis of oligonucleotides and N-terminal sequencing and C. Nelson for mass spectrometry analysis; both are supported by a Cancer Center Support Grant (2P30CA042014). We also thank P. Beal and S. Wente for helpful discussions. This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, GM44073 and GM56775, to B.L.B. and C.P.H., respectively. A.P.V. is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the American Cancer Society. B.L.B. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.