Abstract

Objective

Two-pore domain potassium channels (K2P) play integral roles in cell signaling pathways by modifying cell membrane resting potential. Here we describe the expression and function of K2P channels in nonhuman primate sperm.

Design

Experimental animal study, randomized blinded concentration-response experiments.

Setting

University affiliated primate research center.

Animal(s)

Male nonhuman primates.

Interventions

Western blot and immunofluorescent analysis of epididymal sperm samples. Kinematic measures (VCL and ALH) and acrosome status were studied in epidydimal sperm samples exposed to K2P agonist (Docosahexaenoic acid) and antagonist (Gadolinium).

Main outcome measures

Semi-quantitative protein expression and cellular localization and quantitative changes in specific kinematic parameters and acrosome integrity.

Results

Molecular analysis demonstrated expression and specific regional distribution of TRAAK, TREK-1, and TASK-2 in nonhuman primate sperm. Docosahexaenoic acid produced a concentration-dependent increase in curvilinear velocity (p < 0.0001) with concomitant concentration-dependent reductions in lateral head displacement (p = 0.005). Gadolinium reduced velocity measures (p < 0.01) without significantly affecting lateral head displacement.

Conclusion(s)

The results demonstrated for the first time, expression and function of K2P potassium channels in nonhuman primate sperm. The unique, discrete distributions of K2P channels in nonhuman primate sperm suggest specific roles for this sub-family of ion channels in primate sperm function.

Keywords: Nonhuman primate sperm, protein, ion channel, two-pore domain

INTRODUCTION

Potassium ion (K+) channels have long been known to respond to a host of signals that affect various aspects of mammalian sperm function and morphology (1). Potassium channel-dependent sperm cell hyperpolarization is intimately linked to calcium mediated signaling events required for proper sperm function (2,3,4). Non voltage-dependent two-pore domain (K2P) potassium channels act to determine a cell’s responsiveness to its surroundings through membrane conductance mediated alterations of other voltage-dependent ion channels (5,6). However, very little information is available concerning the expression and function of K2P channels in mammalian reproductive cell types, including sperm.

K2P channels consist of four trans-membrane spanning protein segments that form two ion pores specific for the non-voltage dependent transport of K+ and are highly conserved across a wide range of species and tissues (7,8,9). Chemical mediators, mechanical cellular changes and physiological changes in the intracellular and extracellular milieu modify the activity of K2P channels (10,11). Several K2P channel isoforms respond to alterations in environmental conditions (osmolarity, pH, temperature, and membrane phospholipid content) that play a significant role in mammalian sperm function and fertility (2,12).

The presence, distribution and activity of K2P channels have not previously been reported for primate sperm. The objective of this study was to determine the presence and distribution of TREK-1 (KCNK2), TRAAK (KCNK4) and TASK-2 (KCNK5) K2P channels in nonhuman primate sperm and subsequently, to determine the effects of a TRAAK agonist and antagonist on nonhuman primate sperm kinematic measures and acrosome integrity in an experimental model system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sperm collection and preparation

Animal experiments were performed at the Washington National Primate Research Center (WANPRC) and the Department of Urology at the University of Washington with approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and did not require Institutional Review Board approval. Sperm was collected from the isolated epididymies of Macaca nemestrina testes supplied by the WANPRC tissue redistribution program. Both fresh (immunocytochemistry, drug experiments) and frozen-thawed (Western blot) sperm samples were used. Sperm motility and concentration were determined according to standard procedures (13).

Western Blots

Polyclonal primary antibodies directed against TREK-1 and TASK-2 (Alamone Laboratories), monoclonal primary antibody directed against TRAAK (a generous gift from Professor’s Lesage and Lazdunski, Institut de Pharmacologie Moleculaire et Cellulaire, France) and secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated antibodies (Bio-Rad) were prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sperm samples (50 μl) were diluted 1:10 with 2X Laemmli sample buffer (4% Sodium dodecyl sulfate, 20% glycerol, 10% 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.004% bromphenol blue, 0.125 Tris HCl), boiled (100° C) for 5 minutes, placed into 50 μl wells on a standard electrophoretic gel (10% Tris-HCL) and run for 35 minutes at 200 volts. Rat brain extract (25 μg; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used as the positive control (14). Migrated proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (100 volts for 1 hour at 4° C), blocked (5% skim milk powder) overnight at 4° C and washed before exposure to primary antibody (1:1000) at room temperature for one hour. Washed membranes were then exposed to secondary antibody (1:1,250 – 5,000 host: goat α-rabbit) and conjugated α-HRP (1:2,500 – 1:5,000; Strep-tactin) for 1 hour at room temperature before being exposed to signal enhancing substrate (Pierce Biotechology) for 2 minutes prior to film exposure and development.

Immunofluorescent detection of K2P channels

The protocol used for immunofluorescent detection of K2P channels was adapted from methods described previously for other biological samples (15). Microscope slides smeared with sperm samples (20 μl) were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, air dried, blocked for 1 hour and incubated with or without (negative control) primary antibody against TREK-1, TASK-2 or TRAAK in segregated slide boxes for 20 hours at room temperature. Washed and blocked slides were then incubated at room temperature with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) conjugated secondary antibody (1:800, goat α-rabbit IgG) for 12 hours and visualized at 100X magnification under oil immersion (standard and UV light exposure).

Effects of a K2P agonist and antagonist on sperm kinematics

The TRAAK agonist docosahexaenoic acid (DOHA) and antagonist gadolinium (Gd3+) were studied for their effects on sperm kinematics under non-capacitating conditions (10–12,16). Drug effects on acrosome status were studied under capacitating conditions using sperm previously exposed to caffeine and dbcAMP (16,17,18). Stock solutions of DOHA (10 mM) were prepared in 5% methanol under nitrogen gas and stored at −30° C. Stock solutions of Gd3+ (10 mM) were prepared in PBS and stored at −30° C. The final concentration of sperm in each experimental reaction vessel was approximately 40 x 106 sperm/ml. Twenty minutes after drug exposure, sperm samples were loaded into one of 4 wells of a 20 μl microscope slide chamber (Spectrum Technologies) and recorded on video tape over 1 minute under darkfield microscopy at 20X magnification. Kinematic variables were measured (minimum of 200 individual sperm per sample) from video recordings using a computer assisted sperm analysis system (CASA, IVOS Motility Analyzer, Hamilton-Thorne).

Effects of a K2P agonist and antagonist on sperm acrosome integrity

Sperm samples were fixed and stained using a commercial dye-based colorimetric acrosome stain (Spermac®, Conception Technologies) (19) and visualized at 100X magnification under oil immersion. A minimum of 400 individual sperm were analyzed for each experimental condition and were classified as exhibiting a fully intact acrosome (Acr +), a partially intact acrosome (Acr +/−) or complete acrosome loss (Acr -). For proportional analysis of acrosome integrity, sperm exhibiting partially or fully absent acrosomes were combined.

Data analysis

Experiments were run in a randomized and blinded fashion. Video recordings were scored by an observer blinded to drug treatment. Data are expressed as mean ± the standard error of the mean (SEM) or as proportions for n = 400 – 1654 sperm examined from 2 (acrosome integrity) or 3 (CASA) different males (n = 5 total). Alterations in sperm kinematic measures (VCL; ALH) across treatment groups were analyzed by single factor ANOVA and post hoc Tukey Test (20). Comparisons of VCL and ALH stability over time in drug and vehicle controls and, comparisons of VCL and ALH in capacitated and non-capacitated sperm samples, were carried out using t-tests for samples with equal or unequal variance as determined by F-test (20). Comparisons of the proportions of acrosome intact (Acr+) sperm across treatment groups were completed using chi-square analysis (20).

RESULTS

Western blots

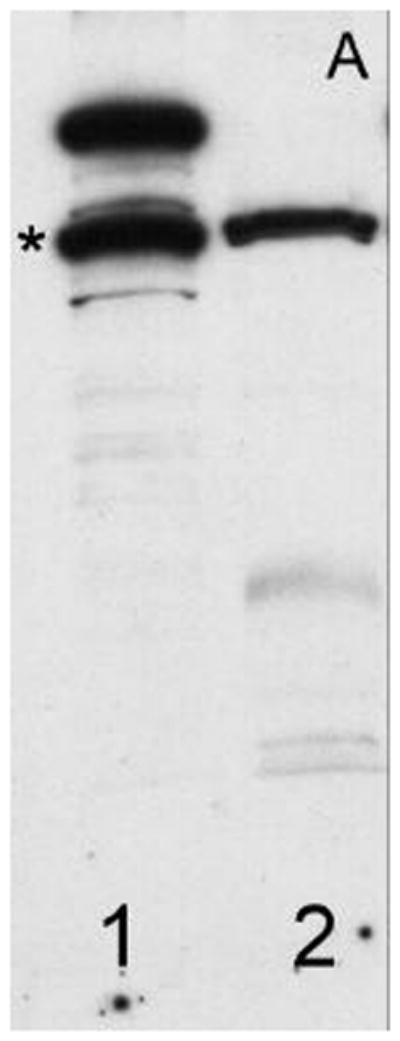

Epididymal sperm collected from 5 males exhibited normal morphology and forward progressive motility (1.98 x 109 ± 0.20 x 109 sperm/ml and 91.8% ± 1.5% motile cells). Sperm samples demonstrated specific K2P protein bands at ~100 KD consistent with the expected molecular weights (92–117 KD) of the various K2P channels reported previously under similar conditions (11,21,22) (Figures 1A–C, column 2). Rat brain extract controls exhibited similar molecular weight bands at ~100 KD (Figure 1A–C; column 1). Rat brain extracts exhibited several bands at ~100 KD consistent with numerous variant forms of K2P channel protein known to exist in this preparation (23,24).

Figure 1.

Demonstrates the expression of (A) TRAAK, (B) TREK-1 and (C) TASK-2 in non-human primate sperm (Macaca nemestrina). Columns 1, Rat brain extract; 2, native sperm. The asterisk (*) indicates protein bands at ~100 KD.

Immunofluorescent detection of K2P channels

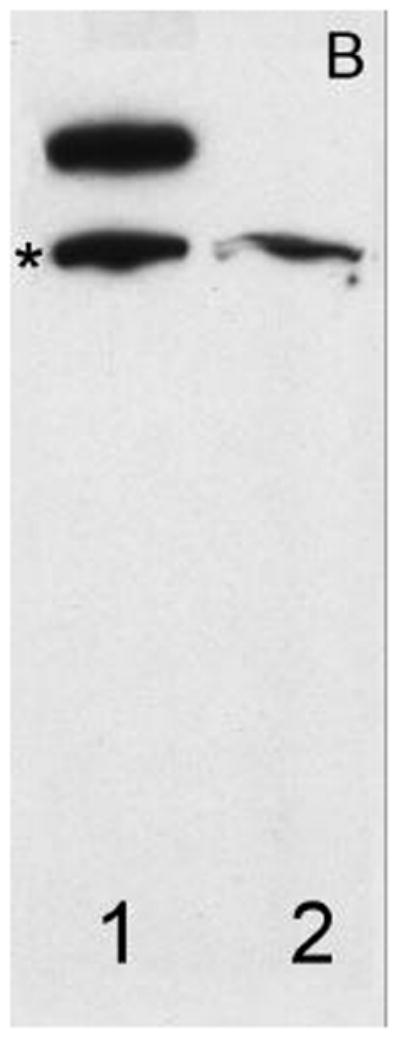

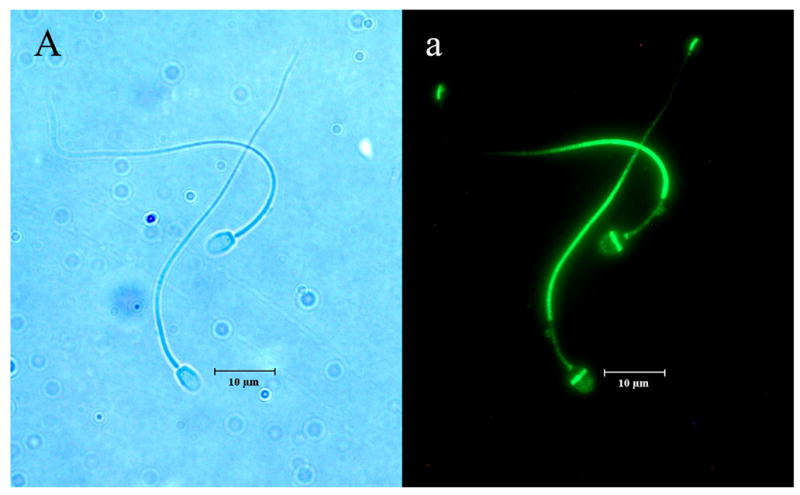

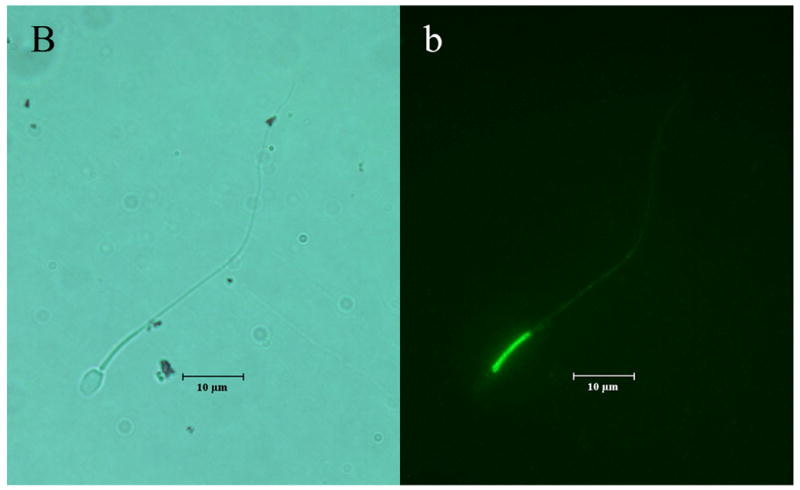

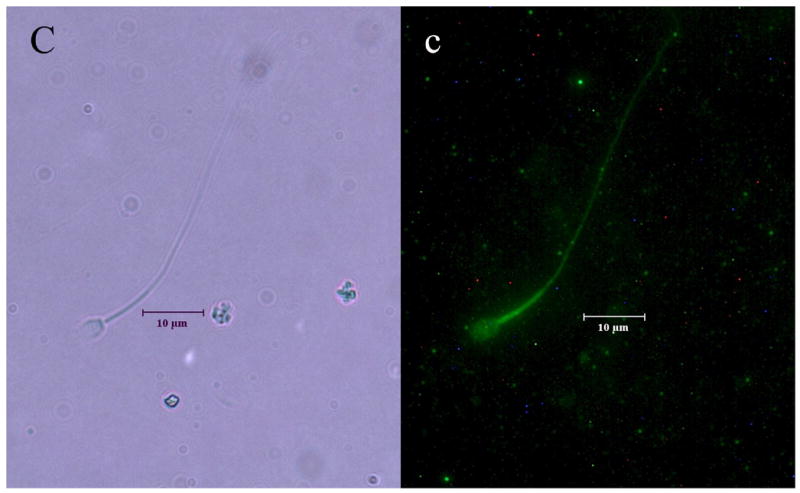

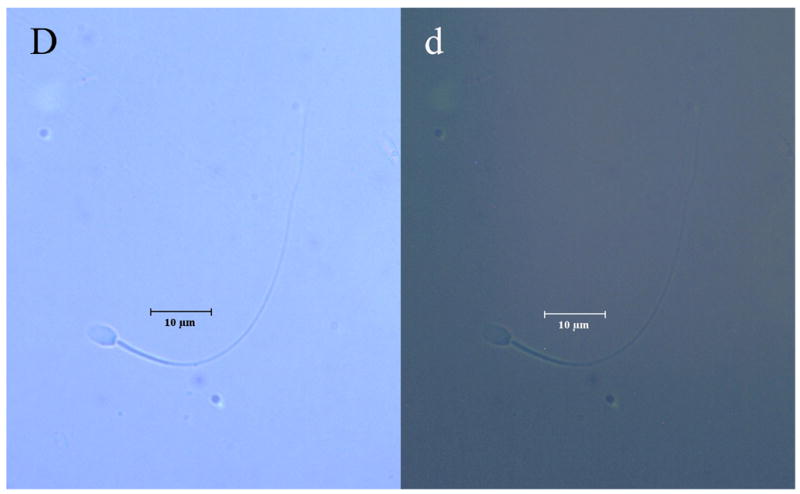

The distinct regional distribution of the K2P isoforms in nonhuman primate sperm is demonstrated for the first time in Figures 2a–c. TRAAK was primarily located at the equatorial band within the sperm head and within the principal piece of the flagellum (Figure 2a). Although the TRAAK signal was present in the mid-piece region, there was a striking transition with a bright signal emanating from the principal piece of the tail with gradual diminution of the signal until it was again accentuated at the tip of the flagellum. TREK-1 was isolated to the mid-piece region of the flagellum (Figure 2b) and exhibited a sharp demarcation point at which the TRAAK isoform demonstrated its greatest intensity in the principal piece of the tail (compare Figures 2a and 2b). The immunofluorescent TASK-2 signal appeared diffuse, with a uniform distribution throughout the entire sperm (Figure 2c). Negative controls lacking exposure to primary antibody failed to exhibit labeled K2P channel protein (Figure 2d).

Figure 2.

Illustrates the regional distributions of (A, a) TRAAK, (B, b) TREK-1 and (C, c) TASK-2 in non-human primate sperm (Macaca nemestrina). Sperm exposed to secondary antibody in the absence of exposure to primary antibodies directed against K2P channel isoforms served as negative controls (D, d). Images with capital letters are light microscope images whereas images with lower case letters represent fluorescent images for each K2P isoform. The horizontal bar indicates a distance of 10 μm.

Effects of a K2P agonist and antagonist on sperm kinematics

DOHA and Gd3+ were selected as a representative agonist and antagonist, respectively to examine the effects of K2P channels on nonhuman primate sperm kinematics and acrosome status due to their relative selectivity for the TRAAK isoform compared to TREK-1 and TASK-2 (5,21,25,26). Because VCL (curvilinear velocity) and ALH (lateral head displacement) are non vector-dependent measures of sperm motion, these measures were used to describe the effects of DOHA and Gd3+ on sperm kinematics (27,28).

Under non-capacitating conditions, DOHA and Gd3+ produced opposite and significant effects on VCL whereas significant effects of drug on ALH were only observed for DOHA and only at the highest concentration examined. Analysis of untreated control preparations over the 20 minute experimental time course indicated preparation stability with no significant differences in VCL (range 109.24 ± 1.42 μm/sec to 113.4 ± 1.49 μm/sec , p = 0.27 to 0.67) or ALH (range 10.82 ± 0.99 μm to 11.14 ± 0.99 μm, p = 0.82 to 0.92). DOHA produced a concentration-dependent increase in VCL (F = 7.70, df = 3, p < 0.0001) and a concomitant concentration-dependent decrease in ALH (F = 4.31, df = 3, p = 0.005) (Table 1). Gd3+ produced a concentration-dependent reduction of VCL (F = 7.42, df = 3. p < 0.0001) whereas the drug effect on ALH failed to reach significance (F = 2.48, df = 3, p = 0.06; Table 1).

TABLE 1.

The Effects of Docosahexaenoic Acid and Gadolinium on Curvilinear Velocity, Lateral Head Displacement and Acrosome Integrity of Nonhuman Primate Sperm

| Drug Treatment | Variable | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| VCL (μm/sec) | ALH (μm) | Acr+ (%) | |

| DOHA | |||

| 0 μM | 105.39 ± 0.96 | 10.39 ± 0.10 | 382/400 (96) |

| 1 μM | 107.77 ± 1.09 | 10.15 ± 0.10 | 388/401 (97) |

| 10 μM | 112.25 ± 1.09a,b | 10.43 ± 0.10 | 381/400 (95) |

| 100 μM | 109.68 ± 0.94a | 10.01 ± 0.09a | 351/400 (88)a,b |

| Gd3+ | |||

| 0 μM | 113.94 ± 1.11 | 10.35 ± 0.10 | 367/400 (92) |

| 1 μM | 112.29 ± 1.17 | 10.58 ± 0.10 | 344/400 (86)a |

| 10 μM | 107.91 ± 1.12a,b | 10.34 ± 0.10 | 390/400 (98)a,b |

| 100 μM | 107.75 ± 1.16a,b | 10.19 ± 0.10 | 380/400 (95)a,b |

Table 1 describes the effects of the 2-pore domain potassium channel agonist docosahexaneoic acid (DOHA) and the antagonist Gadolinium (Gd3+) on curvilinear velocity (VCL) and lateral head displacement (ALH) of non-human primate sperm under non-capacitating conditions and, acrosome integrity (Acr+) under capacitating conditions. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM for 1152–1654 individual sperm (VCL, ALH) or as the proportion (%) of acrosome intact sperm (Acr+, n=400). The superscript letter (a) indicates a significant difference compared to vehicle control (0 μM) whereas (b) indicates a significant difference compared to the 1 μM treatment group. The proportions (%) of acrosome intact sperm in capacitated time controls were 376/400 (94) and 375/400 (94) for DOHA and Gd3+ experiments, respectively and did not differ significantly from respective vehicle controls (0 μM).

Effects of a K2P agonist and antagonist on acrosome integrity

Treatment of nonhuman primate sperm with caffeine and dbcAMP for 15 minutes resulted in full capacitation (16–18,29–31) as demonstrated by drug induced increases in VCL (non-capacitated 110.5 ± 1.0 μm/sec vs. capacitated 176.5 ± 1.4 μm/sec, p < 0.0001) and ALH (non-capacitated 10.1 ± 0.1 μm vs. capacitated 13.6 ± 0.2 μm, p < 0.0001). The effects of DOHA and Gd3+ on acrosome integrity under capacitating conditions were subtle but significant and very different. DOHA produced a significant increase in the proportion of acrosome reacted sperm at a concentration of 100 μM (χ2 = 34.9, df = 4, p < 0.0001; Table 1). Capacitation induced acrosome loss was enhanced by Gd3+ at the lowest concentration examined (1 μM) but was inhibited at higher concentrations of 10 and 100 μM (χ2 = 45.0, df = 4, p < 0.0001; Table 1).

DISCUSSION

The goal of these experiments was to determine the presence, regional distribution and biological effects of a limited number of K2P channels in a nonhuman primate sperm model. Our western blot and indirect immunofluorescent results demonstrate for the first time the presence and distinct regional distributions of the TREK-1, TRAAK and TASK-2 K2P channel isoforms in nonhuman primate sperm. K2P agonist (DOHA) and antagonist (Gd3+) drugs produced subtle but significant direct effects on sperm kinematic measures and acrosome status.

Although the full biological and clinical significance of the differential distribution of ion channels in mammalian sperm remains to be fully elucidated, the importance of potassium and calcium-mediated signaling to sperm physiology remains undisputed (1,32–34). Recent experimental evidence has linked murine sperm membrane hyperpolarization mediated by voltage-gated potassium channels to the acquisition of calcium signaling required for normal sperm function (4,35,36). Thus, changes in membrane potential mediated by non-voltage-dependent K2P channels in response to various physiological stimuli (pH, temperature, osmolarity) could serve as an elegant environmental control mechanism for other voltage-dependent (e.g. Ca2+) mediators of sperm function.

Protein expression and immunocytochemical analysis demonstrated a concentration of TRAAK channel protein at the principle piece of the sperm flagellum and at the equatorial band of the acrosome on the sperm head. In many mammals sperm kinematic measures related to velocity are closely related to movement at the principle piece of the flagellum (37,38). Rapid curvilinear and hyperactivated motility of nonhuman primate sperm are both Ca2+-dependent events and acquisition of both are required for fertilization (29). DOHA produced, through an undetermined mechanism, concentration-dependent changes in nonhuman primate sperm VCL consistent with data obtained from other species (39–41). In our studies Gd3+ produced concentration-dependent reductions in VCL. Previous work with sperm from the Puffer fish (42) also demonstrated a significant inhibitory effect of Gd3+ (10 to 40 μM) on sperm kinematic measures that were ultimately related to block of hyperpolarization-mediated increases in Ca2+ signaling (43).

The effects of DOHA and Gd3+ on nonhuman primate sperm were limited with respect to ALH. VCL is a very sensitive measure of general sperm motility whereas ALH is much less sensitive (44) and, is more closely associated with changes in kinematic variables related to capacitation-induced hyperactivation in nonhuman primate sperm (29). The limited drug effects on ALH were not unexpected given that our experimental conditions were designed to specifically examine the drug effects under non-capacitating conditions.

One of the primary functions that must occur during binding of nonhuman primate sperm to the oocyte is the Ca2+-dependent release of the acrosomal contents (45). Lipids are potent mediators of sperm capacitation and acrosome loss related to fertilization in mammalian species (46,47). DOHA is a lipid that is present in substantial quantities, is differentially distributed, and exhibits marked developmental regulation in nonhuman primate sperm (48,49). Therefore, it is not surprising that lipid sensitive K2P channels such as TRAAK are expressed in sperm regions related to acrosome function. The increase in the degree of acrosome loss in DOHA (100 μM) treated sperm is consistent with other data demonstrating direct links between sperm membrane hyperpolarization, calcium signaling and acrosome loss (4,35,50).

K2P channels are sensitive to a number of physiological conditions that are important determinants of proper sperm function. We have described for the first time the presence and discrete regional distribution of K2P channels in nonhuman primate sperm. The unique expression of K2P channels in nonhuman primate sperm and effects of K2P channel agonists and antagonists on sperm kinematics and acrosome status provides greater insight into the diverse activity of potassium ion channels in sperm biology. Nonhuman primate sperm provides an excellent model for further study of K2P channels related to reproduction in other mammalian species including humans.

Footnotes

These studies supported by grant #R00166 (ECC & ESH) and University of Washington Department of OB/GYN Departmental Funds (GEC) Presented at the ASRM, Montreal, Canada, October 16–19, 2005

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Darszon A, Labarca P, Nishigaki T, Espinosa F. Ion channels in sperm physiology. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:481–510. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.2.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Visconti P, Westbrook VA, Chertihin O, Demarco I, sleight S, Diekman AB. Novel signaling pathways involved in sperm acquisition of fertilizing capacity. J Repro Immunol. 2002;53:133–150. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0378(01)00103-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beltran C, Zapata O, Darszon A. Membrane potential regulates sea urchin sperm adenylylcyclase. Biochemistry. 1996;35:7591–7598. doi: 10.1021/bi952806v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnoult C, Kazam IG, Visconti PE, Kopf GS, Villaz M, Florman HM. Control of the low voltage-activated calcium channel of mouse sperm by egg ZP3 and by membrane hyperpolarization during capacitation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6757–6762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldstein SAN, Bockenhauer D, O’Kelly I, Zilberberg N. Potassium leak channels and the KCNK family of two-P-domain subunits. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:175–184. doi: 10.1038/35058574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kindler CH, Yost CS. Two-pore domain potassium channels: new sites of local anesthetic action and toxicity. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2005;30:260–274. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Talley EM, Solorzano G, Lei Q, Kim D, Bayliss DA. CNS distribution of members of the two-pore-domain (KCNK) potassium channel family. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7491–7505. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-19-07491.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medhurst AD, Rennie G, Chapman CG, Meadows H, Duckworth MD, Kelsell RE, Gloger II, Pangalos MN. Distribution analysis of human two pore domain potassium channels in tissues of the central nervous system and periphery. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2001;86:101–114. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00263-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lesage F. Pharmacology of neuronal background potassium channels. Neuropharmacology. 2003;44:1–78. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00339-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franks NP, Lieb WR. Volatile general anaesthetics activate a novel neuronal K+ current. Nature. 1988;333:662–664. doi: 10.1038/333662a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lesage F, Lazdunski M. Molecular and functional properties of two-pore-domain potassium channels. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2000;279:793–801. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.279.5.F793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Connell AD, Morton MJ, Hunter M. Two-pore domain K+ channels-molecular sensors. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2002;1566:152–161. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(02)00597-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feradis AH, Pawitri D, Suatha IK, Amin MR, Yusuf TL, Sajuthi D, Budiarsa IN, Hayes ES. Cryopreservation of epididymal spermatozoa collected by needle biopsy from cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) J Med Primatol. 2001;30:100–106. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0684.2001.300205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lauritzen I, Zanzouri M, Honore E, Duprat F, Ehrengruber MU, Lazdunski M, Patel AJ. K+-dependent cerebellar granule neuron apoptosis. Role of TASK leak K+ channels. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:32068–32076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302631200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobelt P, Tebbe JJ, Tjandra I, Bae HG, Ruter J, Klapp BF, Wiedenmann B, Monnikes H. Two immunocytochemical protocols for immunofluorescent detection of c-Fos positive neurons in the rat brain. Brain Res Brain Res Protoc. 2004;13:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresprot.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curnow EC, Pawitri D, Hayes ES. Sequential culture medium promotes the in vitro development of Macaca fascicularis embryos to blastocysts. Am J Primatol. 2002;57:203–212. doi: 10.1002/ajp.10043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayes ES, Curnow EC, Trounson AO, Danielson LA, Unemori EN. Implantation and pregnancy following in vitro fertilization and the effect of recombinant human relaxin administration in Macaca fascicularis. Biol Reprod. 2004;71:1591–1597. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.030585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahony MC, Lanzendorf S, Gordon K, Hodgen GD. Effects of caffeine and dbcAMP on zona pellucida penetration by epididymal spermatozoa of cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) Mol Reprod Dev. 1996;43:530–535. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199604)43:4<530::AID-MRD16>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan PJ, Corselli JU, Jacobson JD, Patton WC, King A. Correlation between intact sperm acrosome assessed using the Spermac stain and sperm fertilizing capacity. Arch Androl. 1996;36:25–27. doi: 10.3109/01485019608987881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zar JH. Biostatistical analysis. 2. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maingret F, Lauritzen I, Patel AJ, Heurteaux C, Reyes R, Lesage F, Lazdunski M, Honore E. TREK-1 is a heat-activated background K+ channel. EMBO J. 2000;19:2483–2491. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.11.2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barfield JP, Yeung CH, Cooper TG. The Effects of Putative K+ Channel Blockers on Volume Regulation of Murine Spermatozoa. Biol Reprod. 2005;72:1275–1281. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.038448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salinas M, Reyes R, Lesage F, Fosset M, Heurteaux C, Romey G, Lazdunski M. Cloning of a New Mouse Two-P Domain Channel Subunit and a Human Homologue with a Unique Pore Structure. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11751–11760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gu W, Schlichthörl G, Hirsch JR, Engels H, Karschin C, Karschin A, Derst C, Steinlein OK, Daut J. Expression pattern and functional characteristics of two novel splice variants of the two-pore-domain potassium channel TREK-2. J Physiol. 2002;539:657–668. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fink M, Lesage F, Duprat F, Heurteaux C, Reyes R, Fosset M, Lazdunski M. A neuronal two P domain K+ channel stimulated by arachidonic acid and polyunsaturated fatty acids. EMBO J. 1998;17:3297–3308. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang D, Choe C, Kim D. Thermosensitivity of the two-pore domain K+ channels TREK-2 and TRAAK. J Physiol. 2005;564:103–116. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.081059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis RO, Katz DF. Standardization and comparability of CASA instruments. J Androl. 1992;13:81–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mortimer ST. CASA--practical aspects. J Androl. 2000;21:515–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mahony MC, Gwathmey TY. Protein tyrosine phosphorylation during hyperactivated motility of cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis) spermatozoa. Biol Reprod. 1999;60:1239–1243. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod60.5.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tervino CL, Felix R, Castellano LE, Gutierrez C, Rodriguez D, Pacheco J, Lopez-Gonzalez I, Gomora JC, Tsutsumi V, Hernandez-Cruz A, Fiordelisio T, Scaling AL, Darzon A. Expression and differential cell distribution of low-threshold Ca2+ channels in mammalian germ cells and sperm. FEBS Lett. 2004;563:87–92. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00257-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Felix R, Serrano CJ, Trevino CL, Munoz-Garay C, Bravo A, Navarro A, Pacheco J, Tsutsumi V, Darzon A. Identification of distinct K+ channels in mouse spermatogenic cells and sperm. Zygote. 2002;10:183–188. doi: 10.1017/s0967199402002241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baker MA, Lewis B, Hetherington L, Aitken RJ. Development of the signaling pathways associated with sperm capacitation during epididymal maturation. Mol Reprod Dev. 2003;64:446–457. doi: 10.1002/mrd.10255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benoff S. Modeling human sperm-egg interactions in vitro: signal transduction pathways regulating the acrosome reaction. Mol Hum Reprod. 1998;4:453–471. doi: 10.1093/molehr/4.5.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marin-Briggiler CI, Jha KN, Chertihin O, Buffone MG, Herr JC, Vazquez-Levin MH, Visconti PE. Evidence of the presence of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV in human sperm and its involvement in motility regulation. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:2013–2022. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patrat C, Serres C, Jouannet P. Progesterone induces hyperpolarization after a transient depolarization phase in human spermatozoa. Biol Reprod. 2002;66:1775–1180. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod66.6.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Izumi H, Marian T, Inaba K, Oka Y, Morisawa M. Membrane hyperpolarization by sperm-activating and -attracting factor increases cAMP level and activates sperm motility in the ascidian Ciona intestinalis. Dev Biol. 1999;213:246–256. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turner R. Tales From the Tail: What Do We Really Know About Sperm Motility? J Androl. 2003;24:790–803. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.2003.tb03123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Travis AJ, Jorgez CJ, Merdiushev T, Jones BH, Dess DM, Diaz-Cueto L, Storey BT, Kopf GS, Moss SB. Functional relationships between capacitation-dependent cell signaling and compartmentalized metabolic pathways in murine spermatozoa. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7630–7636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006217200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nissen HP, Kreysel HW. Polyunsaturated fatty acids in relation to sperm motility. Andrologia. 1983;5:264–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.1983.tb00374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mitre R, Cheminade C, Allaume P, Legrand P, Legrand AB. Oral intake of shark liver oil modifies lipid composition and improves motility and velocity of boar sperm. Theriogenology. 2004;62:1557–1566. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brinsko SP, Varner DD, Love CC, Blanchard TL, Day BC, Wilson ME. Effect of feeding a DHA-enriched nutriceutical on the quality of fresh, cooled and frozen stallion semen. Theriogenology. 2005;63:1519–1527. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krasznai Z, Morisawa M, Kraznai ZT, Morisawa S, Inaba K, Bazsane ZK, Rubovszky B, Bodnar B, Borsos A, Marian T. Gadolinium, a mechano-sensitive channel blocker, inhibits osmosis-initiated motility of sea- and freshwater fish sperm, but does not affect human or ascidian sperm motility. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2003;55:232–243. doi: 10.1002/cm.10125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krasznai Z, Márián T, Izumi H, Damjanovich S, Balkay L, Trón L, Morisawa M. Membrane hyperpolarization removes inactivation of Ca2+ channels, leading to Ca2+ influx and subsequent initiation of sperm motility in the common carp. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:2052–2057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040558097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Agarwal A, Sharma RK, Nelson DR. New semen quality scores developed by principal component analysis of semen characteristics. J Androl. 2003;24:343–352. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.2003.tb02681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kirkman-Brown JC, Punt EL, Barratt CL, Publicover SJ. Zona Pellucida and Progesterone-Induced Ca2+ Signaling and Acrosome Reaction in Human Spermatozoa. J Androl. 2002;23:306–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim CK, Im KS, Zheng X, Foote RH. In vitro capacitation and fertilizing ability of ejaculated rabbit sperm treated with lysophospatidylcholine. Gamete Res. 1989;22:131–141. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1120220203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Llanos MN, Meizel S. Phospholipid methylation increases during capacitation of golden hamster sperm in vitro. Biol Reprod. 1983;28:1043–1051. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod28.5.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lenzi A, Gandini L, Maresca V, Rago R, Sgrò P, Dondero F, Picardo M. Fatty acid composition of spermatozoa and immature germ cells. Mol Hum Reprod. 2000;6:226–231. doi: 10.1093/molehr/6.3.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Connora WE, Lina DS, Wolf DP, Alexander M. Uneven distribution of desmosterol and docosahexaenoic acid in the heads and tails of monkey sperm. J Lipid Res. 1998;39:1404–1411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rossato M, Virgilio FDi, Rizzuto R, Galeazzi C, Foresta C. Intracellular calcium store depletion and acrosome reaction in human spermatozoa: role of calcium and plasma membrane potential. Mol Hum Reprod. 2001;7:119–128. doi: 10.1093/molehr/7.2.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]