Abstract

A recently developed tightly bound ion model can account for the correlation and fluctuation (i.e., different binding modes) of bound ions. However, the model cannot treat mixed ion solutions, which are physiologically relevant and biologically significant, and the model was based on B-DNA helices and thus cannot directly treat RNA helices. In the present study, we investigate the effects of ion correlation and fluctuation on the thermodynamic stability of finite length RNA helices immersed in a mixed solution of monovalent and divalent ions. Experimental comparisons demonstrate that the model gives improved predictions over the Poisson-Boltzmann theory, which has been found to underestimate the roles of multivalent ions such as Mg2+ in stabilizing DNA and RNA helices. The tightly bound ion model makes quantitative predictions on how the Na+-Mg2+ competition determines helix stability and its helix length-dependence. In addition, the model gives empirical formulas for the thermodynamic parameters as functions of Na+/Mg2+ concentrations and helix length. Such formulas can be quite useful for practical applications.

INTRODUCTION

Nucleic acids, namely DNAs and RNAs, are negatively charged chain molecules. Ions in the solution can screen (neutralize) the Coulombic repulsion on nucleotide backbone and thus play an essential role in stabilizing compact three-dimensional structures of nucleic acids (1–18). Helices are the most widespread structural motifs in nucleic acid structures. Quantitative understanding of how the ions stabilize helices is a crucial step toward understanding nucleic acid folding.

Current experimental measurements for helix thermodynamic stability mainly focus on the standard salt condition 1 M Na+ (19–27). These parameters form the basis for quantitative studies of nucleic acid helices under this specific ionic condition (19–32). However, cellular physiological condition requires a mixed monovalent/multivalent solution (150 mM Na+, 5 mM Mg2+, and other ions such as K+). These different ions in the solution can compete with each other, resulting in complex interactions with the nucleic acid helix. Therefore, it is highly desirable to have a theory that can make quantitative predictions beyond single-species ion solutions. However, our quantitative understanding on nucleic acid stability in mixed ion solution is quite limited both experimentally and theoretically (33–47).

Experimental and theoretical works have been performed to investigate the general ion-dependence of nucleic acid helix stability (33–47). These studies have led to several useful empirical relationships between ion concentration and nucleic acid helix stability (24,31,44–47). These empirical relationships mainly focus on the monovalent ions (Na+ or K+) (24,31,44–47). However, the mixed multivalent/monovalent ions interact with nucleic acid helices in a much more complex way than single-species monovalent ions. One reason is due to the strong ion-ion correlation between multivalent ions. Extensive experiments suggest that Mg2+ ions are much more efficient than Na+ in stabilizing both DNA and RNA helices (48–59). Because of the limited experimental data and the inability to rigorously treat ion correlation and fluctuation effects, there is a notable lack in quantitative predictions for helix stability in multivalent/monovalent mixed salt solution (31).

A problem with the multivalent ions is the correlation between the ions, especially between ions in the close vicinity of RNA surface, and the related fluctuation over a vast number of possible ion-binding modes. There have been two major types of polyelectrolyte theories for studying the nucleic acid helix stability: the counterion condensation (CC) theory (60–62) and the Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) theory (63–70). Both theories have been quite successful in predicting thermodynamics of nucleic acids and proteins in ion solutions (60–70). The CC theory is based on the assumption of two-state ion distribution and is a double-limit law, i.e., it is developed for dilute salt solution and for nucleic acids of infinite length (71–73). The PB theory is a mean-field theory that ignores ion-ion correlations, which can be important for multivalent ions (e.g., Mg2+).

Recently, a tightly bound ion (TBI) model was developed (74–77). The essence of the model is to take into account the correlation and fluctuation effects for bound ions (74–77). Experimental comparisons showed that the inclusion of correlation and fluctuation effects in the TBI model can lead to improved predictions for the thermodynamic stability of DNA helix and DNA helix-helix assembly (75–77). However, the applicability of the TBI model is hampered by two limitations: 1), the model can only treat single-species ion solutions and cannot treat mixed ion solutions, which are biologically and physiologically significant; and 2), the model does not treat RNA helices. In this article, we go beyond the previous TBI studies by calculating the stability of finite-length RNA (and DNA) helices immersed in a mixed salt solution. Despite its biological significance, for a long time, quantitative and analytical predictions for RNA helix stability in mixed ionic solvent have been unavailable (31,57–59,75). The results presented in this study are a step toward bridging the gap.

METHODS

Thermodynamics for nucleic acid helix stability

We model RNA (DNA) duplex as a double-stranded (ds) helix and the coil as a single-stranded (ss) helix (75). The structures of dsRNA (dsDNA) and ssRNA (ssDNA) are modeled from the grooved primitive model (74–78); see Fig. 1 and Appendices A and B for the structures of ds and ss RNAs (DNAs). We quantify the helix stability by the free energy difference ΔG°T between helix and coil as

|

(1) |

where G°T (ds) and G°T (ss) are the free energies for the dsRNA (DNA) and the ssRNA (DNA), respectively. The stability ΔG°T depends on RNA (DNA) sequences, temperature T, the solvent ionic condition. To calculate the ion dependence of helix stability, we decompose ΔG°T into two parts: the electrostatic contribution  and the nonelectrostatic (chemical) contribution

and the nonelectrostatic (chemical) contribution  (75,79–82),

(75,79–82),

|

(2) |

where  is calculated from the polyelectrolyte theory and

is calculated from the polyelectrolyte theory and  is calculated from the empirical parameters for basepairing and stacking (19–26). As an approximation, we assume that the salt (ion)-independence of

is calculated from the empirical parameters for basepairing and stacking (19–26). As an approximation, we assume that the salt (ion)-independence of  is weak, thus

is weak, thus  for different salt conditions can be calculated from the following equation by using the nearest-neighbor model (19–26) in the standard 1 M NaCl condition:

for different salt conditions can be calculated from the following equation by using the nearest-neighbor model (19–26) in the standard 1 M NaCl condition:

|

(3) |

(1 M NaCl) in the above equation can be calculated from a polyelectrolyte theory, and ΔG°T (1 M NaCl) is obtained from experimental measurement or calculated through the nearest-neighbor model (19–26),

(1 M NaCl) in the above equation can be calculated from a polyelectrolyte theory, and ΔG°T (1 M NaCl) is obtained from experimental measurement or calculated through the nearest-neighbor model (19–26),

|

(4) |

Here the summation (Σ) is over all the base stacks in RNA (DNA) helix. ΔH°bs(1 M Na+) and ΔS°bs(1 M Na+) are the changes of enthalpy and entropy for the formation of base stacks at 1M NaCl, respectively. Here, as an approximation, we ignore the heat capacity difference ΔCp between helix and coil (75,83–90), and treat ΔH°(1 M Na+) and ΔS°(1 M Na+) as temperature-independent parameters (19–26). Such approximation has been shown to be valid when the temperature is not far way from 37°C (86–90).

FIGURE 1.

(A,B) The tightly bound regions around a 14-bp dsRNA (left) and a 14-nt ssRNA (right) in 10 mM MgCl2 (A) and in a mixed 10 mM MgCl2/50 mM NaCl (B) solutions. (C,D) The tightly bound regions around a 14-bp dsDNA (left) and a 14-nt ssDNA (right) in 10 mM MgCl2 (C) and in a mixed 10 mM MgCl2/50 mM NaCl (D) solutions. The red spheres represent the phosphate groups and the green dots represent the points on the boundaries of the tightly bound regions. The dsRNA (ssRNA) and dsDNA (ssDNA) are produced from the grooved primitive model (see Appendices A and B) (74–78) based on the atomic coordinates from x-ray measurements (103,104).

With the use of  determined from Eq. 3 and

determined from Eq. 3 and  calculated from a polyelectrolyte theory, we obtain the helix stability ΔG°T for any given NaCl/MgCl2 concentrations and temperature T (75) of

calculated from a polyelectrolyte theory, we obtain the helix stability ΔG°T for any given NaCl/MgCl2 concentrations and temperature T (75) of

|

(5) |

where NaCl/MgCl2 denotes a mixed NaCl and MgCl2 solution. From ΔG°T in Eq. 5, we obtain the melting temperature Tm for the helix-coil transition for a given strand concentration CS (24,27,31,90),

|

(6) |

Here R is the gas constant (= 1.987 cal/K/mol) and S is 1 or 4 for self-complementary or non-self-complementary sequences, respectively.

The computation of the electrostatic free energy  is critical to the calculation of the folding stability (total free energy ΔG°T). In this work, we go beyond the previously TBI model, which was originally developed for a single-species ionic solution, by computing

is critical to the calculation of the folding stability (total free energy ΔG°T). In this work, we go beyond the previously TBI model, which was originally developed for a single-species ionic solution, by computing  in a solution with mixed salts.

in a solution with mixed salts.

Tightly bound ion model for mixed ion solutions

Previous TBI theories focused on the stability of DNA helix in pure salt solutions, consisting of a single species of counterion and co-ion. In the present study, we extend the TBI model to treat RNA and DNA helices in mixed monovalent (1:1) and z-valent (z:1) salt solutions. The key idea here is to treat the monovalent ions as diffusive ionic background using the mean field PB theory and to treat the multivalent ions using the TBI model, which accounts for the ion-ion correlations.

For the multivalent ions, the inter-ion correlation can be strong. According to the strength of inter-ion correlations, we classify the z-valent ions into two types (74–77): the (strongly correlated) tightly bound ions and the (weakly correlated) diffusively bound ions. Correspondingly, the space for z-valent ions around the nucleic acid can be divided into tightly bound region and diffusive region, respectively. The motivation to distinguish these two types of z-valent ions (and the two types of spatial regions for z-valent ions) is to treat them differently: for the diffusive z-valent ions, we use PB; for the tightly bound z-valent ions, we must use a separate treatment that can account for the strong ion-ion correlations and ion-binding fluctuations.

For the z-valent ions, we divide the entire tightly bound region into 2N cells for an N-bp dsRNA (or DNA) helix, each around a phosphate. In a cell i, there can be mi = 0, 1, 2.. tightly bound z-valent ions (74–77). The distribution of the number of the tightly bound ions in the 2N cells, {m1, m2, … , m2N}, defines a binding mode, and a large number of such binding modes exists. The total partition function Z is given by the summation over all the possible binding modes M for z-valent ions,

|

(7) |

where ZM is the partition function for a given binding mode M.

To obtain the total partition function, we need to compute ZM. For a mode of Nb tightly bound z-valent ions and Nd(= Nz − Nb + N+ + N–) diffusively bound ions, we use Ri (i = 1, 2, … , Nb) and rj (j = 1, 2, … , Nd) to denote the coordinates of the ith tightly bound ion and the jth diffusive ion, respectively. Here Nz, N+, and N– are the numbers of z-valent ions, monovalent ions, and co-ions. The total interaction energy U(R, r) of the system for a given ion configuration  can be decomposed into three parts: the interaction energy Ub(R) between the fixed charges (the tightly bound z-valent ions and the phosphate charges), the interaction energy Us(R, r) between the diffusive ions, and the interaction energy Uint(R, r) between the diffusive ions and the fixed charges. Then, we can compute ZM from the following configurational integral (74,75):

can be decomposed into three parts: the interaction energy Ub(R) between the fixed charges (the tightly bound z-valent ions and the phosphate charges), the interaction energy Us(R, r) between the diffusive ions, and the interaction energy Uint(R, r) between the diffusive ions and the fixed charges. Then, we can compute ZM from the following configurational integral (74,75):

|

(8) |

In the above integral, for a given mode, Ri can distribute within the volume of the respective tightly bound cell while rj can distribute in the volume of the bulk solution. VR denotes the tightly bound region for z-valent ions, and the integration for Ri of the ith tightly bound z-valent ion is over the respective tightly bound cell. Vr denotes the region for the diffusive ions, and the integration for rj of the jth diffusive ion is over the entire volume of the region for diffusive ions. Averaging over all possible ion distributions gives the free energies ΔGb and ΔGd for the tightly bound and the diffusive ions, respectively (74–77),

|

(9) |

In the TBI model, we assume the dependence of ΔGd on the tightly bound ions is mainly through the net tightly bound charge, which is dependent only on Nb (74–77). Thus, we obtain the following simplified configurational integral for ZM (74–77),

|

(10) |

where Z(id) is the partition function for the uniform ionic solution without the polyanionic helix. The volume integral  provides a measure for the accessible space for the Nb tightly bound z-valent ions. ΔGb in Eq. 10 is the Coulombic interaction energy between all the charge-charge pairs (including the phosphate groups and the tightly bound ions) in the tightly bound region; and ΔGd in Eq. 10 is the free energy for the electrostatic interactions between the diffusive ions and between the diffusive ions and the charges in the tightly bound region, and the entropic free energy of the diffusive ions (74–77). The formulas for calculating the free energies ΔGb and ΔGd are presented in detail in the literature (74–77) and in Appendix C.

provides a measure for the accessible space for the Nb tightly bound z-valent ions. ΔGb in Eq. 10 is the Coulombic interaction energy between all the charge-charge pairs (including the phosphate groups and the tightly bound ions) in the tightly bound region; and ΔGd in Eq. 10 is the free energy for the electrostatic interactions between the diffusive ions and between the diffusive ions and the charges in the tightly bound region, and the entropic free energy of the diffusive ions (74–77). The formulas for calculating the free energies ΔGb and ΔGd are presented in detail in the literature (74–77) and in Appendix C.

The electrostatic free energies for a dsRNA (dsDNA) or an ssRNA (ssDNA) can be computed as

|

(11) |

From Eq. 3 for the nonelectrostatic part ( ) and Eq. 11 for the electrostatic part (

) and Eq. 11 for the electrostatic part ( we can compute the total folding stability ΔG°T for a nucleic acid helix for a given ionic condition and temperature.

we can compute the total folding stability ΔG°T for a nucleic acid helix for a given ionic condition and temperature.

The computational process of the TBI model can be summarized briefly into the following steps (74–77):

First, for an RNA (DNA) helix in salt solution, we solve the nonlinear PB to obtain the ion distribution around the molecule, from which we determine the tightly bound region for z-valent ions (74–77).

Second, we compute the pairwise potentials of mean force. The calculated potentials of mean force are tabulated and stored for the calculation of ΔGb.

Third, we enumerate the possible binding modes.

For each mode, we calculate ΔGb and ΔGd (see (74–77) and Appendix C), and compute ZM from Eq. 10. Summation over all the binding modes gives the total partition function Z (Eq. 7), from which we can calculate the electrostatic free energy for helices.

Before presenting the detailed results, we first clarify the terminology to be used in the discussions:

First, we use the term ion-binding to denote the ion-RNA interactions (in excess of the ion-ion interactions in the bulk solvent without the presence of RNA). Therefore, the distribution of the bound ions can be evaluated as the actual ion concentration (with the presence of RNA) minus the bulk ion concentration (91–93).

Second, in the TBI model, we call the strongly correlated bound ions the tightly-bound ions only because these ions are usually distributed within a thin layer surrounding the RNA surface. This term bears no relationship with the ions that are tightly held to certain specific sites of RNA through specific interactions.

Third, in the TBI theory, the actual distribution of the ions in the solution is not determined by one or two binding modes alone. Instead, it is determined by the ensemble average over all the possible modes. The different modes represent the different possible configurations of the bound ions.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

We investigate the folding thermodynamics of the nucleic acid duplexes for a series of RNA and DNA sequences of different lengths. In Tables 1 and 2, we list the RNA and DNA sequences used in the calculations, respectively, as well as the thermodynamic parameters (ΔH°, ΔS°, ΔG°37) for 1 M NaCl calculated from the nearest-neighbor model. We choose these sequences because the experimental data for the helix stability is available for theory-experiment comparison. A primary interest in this study is to investigate the folding stability of RNA helices. However, to make use of the available experimental data for DNA helices to test the theory and to go beyond the previous DNA helix stability studies by extending to the mixed salt solution, we will also investigate DNA helix stability in mixed salt solution.

TABLE 1.

The RNA sequences used in the calculations

| Sequence | N (bp) | Expt. ref. | −ΔH° (kcal/mol)* | −ΔS° (cal/mol/K)* | −ΔG°37 (kcal/mol)* | −ΔG°37 (expt) (kcal/mol)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGCGA | 5 | (26) | 37.4 | 103.7 | 5.2 | 5.2 |

| CCAUGG | 6 | (57) | 53.4 | 148.8 | 7.3 | 7.5 |

| ACCGACCA/AGGCUGGA‡ | 6 | (59) | — | — | — | 12.6 |

| ACUGUCA | 7 | (26) | 55.5 | 152.9 | 8.1 | 7.9 |

| CCAUAUGG | 8 | (57) | 72.7 | 198.6 | 11.1 | 9.7 |

| GCCAGUUAA | 9 | (53) | 74.6 | 202.6 | 11.8 | — |

| AUUGGAUACAAA | 12 | (53) | 94.0 | 259.9 | 13.4 | — |

| AAAAAAAUUUUUUU | 14 | (35) | 80.2 | 236.6 | 6.8 | 6.6 |

| CCUUGAUAUCAAGG | 14 | (57) | 130.0 | 353.2 | 20.4 | 17.2 |

In the calculations with the standard salt state (1 M NaCl), we use either the experimental data or the data calculated from the nearest-neighbor model if the corresponding experimental data is absent.

The thermodynamic data are calculated at standard salt state (1 M NaCl) from the nearest-neighbor model with the measured thermodynamic parameters in Xia et al. (26).

ΔG°37 (expt) is the experimental data at standard salt state (1 M NaCl).

The sequences form RNA duplex with dangling adenines (59). We neglect the contribution from the dangling adenines to the electrostatic free energy change ΔGel, and we use the experimental ΔH° and ΔS° in the calculations.

TABLE 2.

The DNA sequences used in the calculations

| Sequence 5′–3′ | N (bp) | Expt. ref. | −ΔH° (kcal/mol)* | −ΔS° (cal/mol/K)* | −ΔG°37 (kcal/mol)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GCATGC | 6 | (49) | 43.6 | 121.6 | 5.9 |

| GGAATTCC | 8 | (37) | 46.8 | 130.8 | 6.2 |

| GCCAGTTAA | 9 | (53) | 63.1 | 174.8 | 8.9 |

| ATCGTCTGGA | 10 | (41,47) | 70.5 | 192.0 | 11.0 |

| CCATTGCTACC | 11 | (41) | 81.1 | 222.5 | 12.1 |

| AGAAAGAGAAGA | 12 | (55) | 83.1 | 231.2 | 11.4 |

| TTTTTTTGTTTTTTT | 15 | (54) | 107.1 | 303.3 | 13.0 |

The thermodynamic data are calculated from the nearest-neighbor model with the thermodynamic parameters of SantaLucia (24).

In the following section, we first investigate the properties of Mg2+ binding to RNA and DNA duplexes in mixed Na+/Mg2+ solutions. We then investigate the stability of RNA helices in NaCl, MgCl2, and mixed NaCl/MgCl2 salt solutions. Finally, we study the thermal stability of finite-length DNA helices in mixed NaCl/MgCl2 solutions. The mixed Na+/Mg2+ condition under investigation covers a broad range of ion concentrations: [Mg2+] ∈ [0.1 mM, 0.3 M] and [Na+] ∈ [0 M, 1 M]. We mainly focus on the theory-experiment comparisons for two thermodynamic quantities: folding free energy ΔG°37 and melting temperature Tm. In addition, based on the results from the extended TBI model described above, we derive empirical expressions for the thermodynamic parameters for RNA and DNA duplexes as functions of [Na+] and [Mg2+] and helix length.

Mg2+ binding to finite-length RNA and DNA helices in mixed Na+/Mg2+ solutions

We have developed a grooved primitive structural model for A-form RNA helix. The model is based on the atomic coordinates of phosphate charges and contains the key structural details such as the major and minor grooves of the helix; see Appendix A for a detailed description of the model. For DNA helix, we use the previously developed structural model; see Appendix B. Based on these structural models, we investigate the ion binding properties and their effects on the thermodynamics of RNA and DNA helices.

Following the previous works (92,93), we use the extended TBI model developed here to calculate the binding of Mg2+ to RNA and DNA duplexes in the presence of Na+ ions. In the TBI model, the number of the so-called bound ions includes both the tightly bound Mg2+ ions and the diffusively bound ions (in the excess of bulk concentrations). We calculate the number of such bound ions per nucleotide,  from the equation (74,92,94)

from the equation (74,92,94)

|

(12) |

where  is the mean fraction of the tightly bound Mg2+ ions per nucleotide, which is given by the average over all the possible binding modes M of the tightly bound ions:

is the mean fraction of the tightly bound Mg2+ ions per nucleotide, which is given by the average over all the possible binding modes M of the tightly bound ions:  In Eq. 12, Nb is the number of the tightly bound ions for mode M, ZM is the partition function of the system in mode M, Z is the total partition function given by Eq. 7, and N is the number of the phosphates on each strand. The second term in Eq. 12 is the contribution from the diffusively bound Mg2+, where

In Eq. 12, Nb is the number of the tightly bound ions for mode M, ZM is the partition function of the system in mode M, Z is the total partition function given by Eq. 7, and N is the number of the phosphates on each strand. The second term in Eq. 12 is the contribution from the diffusively bound Mg2+, where  and

and  are the Mg2+ concentrations at r and the bulk concentration, respectively, and 2N is the total number of the nucleotides in the duplex.

are the Mg2+ concentrations at r and the bulk concentration, respectively, and 2N is the total number of the nucleotides in the duplex.

Fig. 2, A–D, show the  results for RNA and DNA duplexes in mixed Na+/Mg2+ solutions. The TBI predictions are close to the experimental data (95,96) for both RNA and DNA duplexes, while the PB underestimates

results for RNA and DNA duplexes in mixed Na+/Mg2+ solutions. The TBI predictions are close to the experimental data (95,96) for both RNA and DNA duplexes, while the PB underestimates  This is in accordance with the previous Monte Carlo analysis (91), which shows that PB underestimates the ion concentration near the nucleic acid surface, especially for multivalent ions. Such underestimation can be offset by the use of a smaller ion radius (= width of the charge exclusion layer) in the PB calculations. As shown in Fig. 2, A and B, a smaller Mg2+ ion radius can cause notable changes in the PB results for

This is in accordance with the previous Monte Carlo analysis (91), which shows that PB underestimates the ion concentration near the nucleic acid surface, especially for multivalent ions. Such underestimation can be offset by the use of a smaller ion radius (= width of the charge exclusion layer) in the PB calculations. As shown in Fig. 2, A and B, a smaller Mg2+ ion radius can cause notable changes in the PB results for

FIGURE 2.

The Mg2+ binding fraction  per nucleotide as a function of the Mg2+ concentration for RNA/DNA helices in a mixed salt solution with different [Na+]. (Symbols) Experimental data, poly (A.U.) (95) for A and C and calf thymus DNA (96) for B and D. (Shaded lines) PB results; (solid lines) TBI results. (A and B) Tests for different ion radii for the helices of length 24-bp. (Solid lines)

per nucleotide as a function of the Mg2+ concentration for RNA/DNA helices in a mixed salt solution with different [Na+]. (Symbols) Experimental data, poly (A.U.) (95) for A and C and calf thymus DNA (96) for B and D. (Shaded lines) PB results; (solid lines) TBI results. (A and B) Tests for different ion radii for the helices of length 24-bp. (Solid lines)  ; (dashed lines),

; (dashed lines),  (C,D) Tests for different helix lengths. (Solid lines) 24-bp; (dashed lines) 15-bp. (E) The statistical ensemble averaged fraction fb of the tightly bound Mg2+ ions in a 24-bp dsRNA helix. The nucleotides are numbered according to the z coordinates along the axis, and [Na+] = 0.01 M. Our calculations with both the TBI model and the PB theory are based on the grooved primitive structural models for the helices described in Appendices A and B.

(C,D) Tests for different helix lengths. (Solid lines) 24-bp; (dashed lines) 15-bp. (E) The statistical ensemble averaged fraction fb of the tightly bound Mg2+ ions in a 24-bp dsRNA helix. The nucleotides are numbered according to the z coordinates along the axis, and [Na+] = 0.01 M. Our calculations with both the TBI model and the PB theory are based on the grooved primitive structural models for the helices described in Appendices A and B.

As shown in Fig. 2, C and D, the TBI-predicted  results for 24-bp and 15-bp helices are smaller than the experimental data, which are for long helices. The theory-experiment difference may be attributed to the finite length effect (74,97,98), because our results for longer helices give better agreements with the experiments (see Fig. 2, C and D). In fact, one of the limitations of the current TBI model is its inability to treat very long helices (≳30 bps). Fig. 2 E shows the distributions of the tightly bound ions along the dsRNA helix. From Fig. 2 E, we find that the finite-length effect is weaker for higher [Mg2+]. This is because higher [Mg2+] leads to a larger fraction of charge neutralization for RNA and thus weaker finite length effect.

results for 24-bp and 15-bp helices are smaller than the experimental data, which are for long helices. The theory-experiment difference may be attributed to the finite length effect (74,97,98), because our results for longer helices give better agreements with the experiments (see Fig. 2, C and D). In fact, one of the limitations of the current TBI model is its inability to treat very long helices (≳30 bps). Fig. 2 E shows the distributions of the tightly bound ions along the dsRNA helix. From Fig. 2 E, we find that the finite-length effect is weaker for higher [Mg2+]. This is because higher [Mg2+] leads to a larger fraction of charge neutralization for RNA and thus weaker finite length effect.

The  curves for a similar system have been calculated previously using PB (92,93), where the RNA and DNA duplexes are represented by infinite-length charged cylinders with the negative charges distributed on the axes with equal spacing (92,93). In contrast, the present TBI theory is based on more realistic grooved structures for RNA and DNA helices. However, the present TBI model can only treat helices of (short) finite length. Moreover, the present TBI theory and the PB (92,93) may use quite different ion radii (we use

curves for a similar system have been calculated previously using PB (92,93), where the RNA and DNA duplexes are represented by infinite-length charged cylinders with the negative charges distributed on the axes with equal spacing (92,93). In contrast, the present TBI theory is based on more realistic grooved structures for RNA and DNA helices. However, the present TBI model can only treat helices of (short) finite length. Moreover, the present TBI theory and the PB (92,93) may use quite different ion radii (we use  in this TBI study).

in this TBI study).

Salt dependence of folding free energy ΔG°37 for RNA helices

Based on the structural models for dsRNA helix and ssRNA (see Appendix A), using Eq. 5, we calculate the folding free energy ΔG°37 for RNA duplex formation for the RNA sequences listed in Table 1.

In Na+ solutions

The folding free energy ΔG°37 for RNA helices, predicted by the TBI model, is plotted as a function of Na+ concentration in Fig. 3. Also plotted in Fig. 3 is the experimental data for the sequences with different lengths: CCAUGG (57), CCAUAUGG (57), GCCAGUUAA (53), AUUGGAUACAAA (53), and CCUUGAUAUCAAGG (57). Fig. 3 shows that, as we expected, higher [Na+] causes higher RNA helix stability, and the Na+-dependence is stronger for longer sequences. This is because higher [Na+] causes a smaller translation entropy decrease (and thus lower free energy) for the bound ions. As a result, the fraction of charge neutralization of RNA is larger for higher [Na+]. Such Na+-dependence is more pronounced for dsRNA (of higher charge density) than for ssRNA (of lower charge density), and consequently results in helix stabilization by higher [Na+]. Moreover, longer helices involve stronger Coulombic interactions and thus have stronger Na+-dependence than shorter helices. Fig. 3 shows good agreements between the TBI predictions and the available experimental data for RNA helices.

FIGURE 3.

The folding free energy ΔG°37 of RNA helix as functions of NaCl concentration for different sequences of various lengths: CCAUGG, CCAUAUGG, GCCAGUUAA, AUUGGAUACAAA, and CCUUGAUAUCAAGG (from top to bottom). (Solid lines) Calculated from the TBI model. (Dashed lines) SantaLucia's empirical formula for DNA duplex in NaCl solution (24). (Dotted lines) Tan-Chen's empirical formula for DNA duplex in NaCl solution (75). (Symbols) Experimental data: ◊ CCAUGG (57); ♦ CCAUAUGG (57); □ GCCAGUUAA (53); ▴ AUUGGAUACAAA; and ▪ CCUUGAUAUCAAGG (57). ▵ is calculated from the individual nearest-neighbor model with the thermodynamic parameters in Xia et al. (26).

In Mg2+ solutions

The folding free energy ΔG°37 predicted by the TBI model is plotted as function of [Mg2+] in Fig. 4 (curves with [Na+] = 0). Similar to the Na+-dependence of the helix stability, higher [Mg2+] causes larger neutralized fraction of RNA, resulting in a higher helix stability (i.e., lower folding free energy ΔG°37). As [Mg2+] exceeds a high concentration (>0.03M), the decrease of ΔG°37 with increased [Mg2+] becomes saturated. This is because for high [Mg2+], when the RNA helix becomes fully neutralized, further addition of Mg2+ will not increase the fraction of charge neutralization for RNA. Therefore, the decrease in ΔG°37 and the stabilization of the helix caused by further addition of ions are saturated.

FIGURE 4.

The folding free energy ΔG°37 of RNA helix as functions of MgCl2 concentration for mixed NaCl/MgCl2 solutions with different NaCl concentrations and for different sequences. (A) CCAUGG: [NaCl] = 0 M, 0.018 M, 0.1 M, and 1 M (from top to bottom); (B) CCAUAUGG: [NaCl] = 0 M, 0.03 M, 0.1 M, and 1 M (from top to bottom); and (C) CCUUGAUAUCAAGG: [NaCl] = 0 M, 0.03 M, 0.1 M, and 1 M (from top to bottom). (Solid lines) predicted by the TBI model; (dotted lines) predicted by the PB theory; (dashed lines) the fitted PB by decreasing the Mg2+ radius to 3.5 Å (to obtain optimal fit with the experimental data). Symbols: experimental data. (A) □ CCAUGG in mixed NaCl/MgCl2 solution with 0.1 M NaCl and 10 mM sodium cacodylate (57). (B) □ CCAUAUGG in mixed NaCl/MgCl2 solution with 0.1 M NaCl and 10 mM sodium cacodylate (57). (C) □ CCUUGAUAUCAAGG in mixed NaCl/MgCl2 solution with 0.1 M NaCl and 10 mM sodium cacodylate (57).

Fig. 4 shows that, as compared to the TBI theory, the PB theory can underestimate the RNA helix stability due to the neglected correlated low-energy states of the (bound) Mg2+ ions (75). Such deficiency in helix stability is more pronounced for longer helices, where electrostatic interactions and correlation effects become more significant.

In mixed Na+/Mg2+ solutions

In Fig. 4, we show the folding free energy ΔG°37 for three RNA helices in mixed Na+/Mg2+ solutions: CCAUGG (57), CCAUAUGG (57), and CCUUGAUAUCAAGG (57). The comparison shows improved predictions from the TBI than the PB as tested against the available experimental data.

For mixed Na+/Mg2+ solution, in addition to the general trend of increased stability for higher [Na+] and [Mg2+], the interplay between monovalent and divalent ions leads to the following behavior of the helix folding stability:

For high [Mg2+], helix stability is dominated by Mg2+ and is hence not sensitive to [Na+].

As [Mg2+] is decreased so that [Mg2+] becomes comparable with [Na+], Na+ ions, which are less efficient in stabilizing the helix, begin to play a role and compete with Mg2+, causing the helix to become less stable as manifested by the increase in ΔG°37 as [Mg2+] is decreased.

As [Mg2+] is further decreased, helix stability would be dominated by Na+ ions and becomes insensitive to [Mg2+].

Also shown in Fig. 4 are the predictions from the PB theory. For low-[Mg2+] solution, the electrostatic interactions are dominated by the Na+ ions, whose correlation effect is negligible. As a result, PB and TBI model give nearly identical results. For high-[Mg2+] solution, however, the mean-field PB theory underestimates helix stability because it cannot account for the low-energy correlated states of Mg2+ ions (75–77). For the PB calculations, to partially make up the stability caused by the ignored low-energy states for the correlated Mg2+ ions, one can use a smaller Mg2+ ion radius, corresponding to a smaller thickness of the exclusion layer on the molecular surface. As shown in Fig. 4, we find that the PB theory can give improved fit to the experimental data if we assume that the Mg2+ ion radius is as small as the Na+ ion radius. This does not imply the validity of PB for the Mg2+-induced stabilization because such fitted Mg2+ ion radius is the same as the Na+ radius (99). Even with the small Mg2+ ion radius (equal to Na+ radius), the agreement with the experiment data is not as satisfactory as the TBI theory, which uses a larger (than Na+) Mg2+ ion radius (99). In fact, the correlation effect neglected in the PB theory can be crucial for multivalent ion-mediated force in nucleic acid structures such as the packing of helices (76,77). It is important to note that the ion radius used here is an effective hydrated or partially dehydrated radius. Such a radius would vary with the change of the ion hydration state and could be different for different measurements.

An intriguing observation from Fig. 4, A–C, is the length-dependence of helix stability. As helix length is increased, the TBI model-predicted curves for the [Mg2+]-dependence of helix stability for different [Na+] begin to cross over each other; i.e., for a certain range of [Mg2+], adding Na+ ions can slightly destabilize the helix. Such (slight) Na+-induced destabilization has also been observed in experiments (53). We note that such phenomena is absent in the Poisson-Boltzmann theory-predicted curves. Physically, the Na+-induced destabilization is due to the Na+-Mg2+ competition for longer helices, as explained below. Mg2+ ions are (much) more efficient in charge neutralization than Na+ ions, and the higher efficiency of Mg2+ over Na+ is more pronounced for longer helices, which involves stronger electrostatic interactions. For a given [Mg2+], an increase in [Na+] would enhance the probability for the binding of Na+ ions (100). The enhanced Na+ binding would reduce the binding affinity of Mg2+. Such effect is more significant for longer helices, causing the helix to be slightly destabilized by the addition of Na+ for long helices.

Salt concentration-dependence of melting temperature Tm for RNA helices

From Eq. 6, the melting temperature Tm for RNA helix-to-coil transition can be calculated for different ionic conditions: pure Na+, pure Mg2+, and mixed Na+/Mg2+.

In Na+ solutions

In Fig. 5, Tm-values of RNA helices are plotted as a function of [Na+] for different sequences: CCAUGG (57), AUUGGAUACAAA (53), AAAAAAAUUUUUUU (35), CCUUGAUAUCAAGG (57), and ACCGACCA/AGGCUGGA with dangling adenines (59). Fig. 5 shows the good agreement between the TBI model and the available experimental data. In accordance with the predicted higher helix stability (lower ΔG°37) for higher [Na+] (Fig. 3), the Tm of RNA helices increases with [Na+].

FIGURE 5.

The melting temperature Tm of RNA helix as a function of NaCl concentration for different sequences of various lengths: CCUUGAUAUCAAGG of strand concentration CS = 10−4 M, ACCGACCA/AGGCUGGA of CS = 9 μM, AUUGGAUACAAA of CS = 8 μM, CCAUGG of CS = 10−4 M, and AAAAAAAUUUUUUU of 3.9 μM (from top to bottom). (Solid lines) calculated from TBI model. (Dashed lines) SantaLucia's empirical formula for DNA duplex in NaCl solution (24). (Dotted lines) Tan-Chen's empirical formula for DNA duplex in NaCl solution (75). (Symbols) Experimental data: □ CCUUGAUAUCAAGG (57); ♦ ACCGACCA/AGGCUGGA (59); ▪ AUUGGAUACAAA (53); ◊ CCAUGG (57); and ▴ AAAAAAAUUUUUUU (35). Here, ACCGACCA/AGGCUGGA is a duplex with dangling adenines (59), and we assume the dangling adenines do not contribute to the electrostatics in the helix-coil transition.

For comparison, in Figs. 3 and 5, we also show the results for DNA helix stability. The results for DNA helix are obtained from two different methods: SantaLucia's empirical formula (24) and the empirical formula derived from the TBI model (75). From Figs. 3 and 5, we find that for short helices, DNA and RNA helices have similar stabilities ΔG°37 for a given Na+ ion concentration in the range [0.1 M, 1 M]. Thus, the use of SantaLucia's empirical formula can still give reasonable estimations for RNA helix stabilities at high Na+ concentration (101,102). For [Na+] below ∼0.1 M Na+, SantaLucia's empirical formula overestimates the stabilities of RNA (and DNA) helices (75). From the experimental comparisons shown in Figs. 3 and 5, we find that the formula derived from the TBI model for DNA (75) can give good fit for Na+-dependence of ΔG°37 of RNA helix even for lower Na+ concentrations. For very low Na+ concentrations, the empirical relation for DNA slightly (75) overestimates the RNA stability. Therefore, compared to DNA helix, RNA helix stability has (slightly) stronger Na+-dependence. The (slightly) stronger Na+-dependence of ΔG°37 for RNA helix is because the A-form RNA helix has (slightly) higher negative charge density (103–105) than the B-form DNA helix (see Appendices A and B).

In mixed Na+/Mg2+ solutions

For mixed Na+/Mg2+ solutions, Fig. 6 shows the Tm-values of RNA helices for different sequences: CCAUGG (57), CCAUAUGG (57), and CCUUGAUAUCAAGG (57). In the high [Mg2+] and high [Na+] case, the electrostatic effect of helix stability is dominated by the Mg2+ and Na+ ions, respectively. In the regime of strong Na+-Mg2+ competition, the high concentration of Na+ ions would weaken the helix stability for a fixed [Mg2+]. Such effect would result in a lower Tm, and the Na+-induced helix destabilization is more pronounced for longer helices (75).

FIGURE 6.

The melting temperature Tm of RNA helix as a function of MgCl2 concentration in mixed NaCl/MgCl2 solutions with different NaCl concentrations and for different RNA sequences. (A) CCAUGG of strand concentration CS = 10−4 M: [NaCl] = 0 M, 0.018 M, 0.1 M, and 1 M (from bottom to top); (B) CCAUAUGG of CS = 10−4 M: [NaCl] = 0 M, 0.03 M, 0.1 M, and 1 M (from bottom to top); and (C) CCUUGAUAUCAAGG of CS = 10−4 M: [NaCl] = 0 M, 0.03 M, 0.1 M, 1 M (from bottom to top). (Solid lines) Predicted by the TBI model; (dotted lines) predicted by the PB theory; (dashed lines) the fitted PB by decreasing Mg2+ radius to 3.5 Å (to have optimal PB-experiment agreement). (Symbols) Experimental data. (A) □ CCAUGG in mixed NaCl/MgCl2 solution with 0.1 M NaCl and 10 mM sodium cacodylate (57). (B) □ CCAUAUGG in mixed NaCl/MgCl2 solution with 0.1 M NaCl and 10 mM sodium cacodylate (57). (C) □ CCUUGAUAUCAAGG in mixed NaCl/MgCl2 solution with 0.1 M NaCl and 10 mM sodium cacodylate (57).

Thermodynamic parameters of RNA helix as functions of Na+ and Mg2+ concentrations

With the TBI model, we can obtain RNA helix stability for any given Na+ and Mg2+ concentrations. However, for practical applications, it would be useful to derive empirical formulas for RNA helix stability as functions of Na+ and Mg2+ concentrations. In this section, based on the TBI model predictions for the RNA helix stability for sequences listed in Table 1, we derive empirical expressions for RNA helix stability at different ionic conditions. Since the general formula in mixed Na+/Mg2+ solution can be most conveniently derived from the results for pure Na+ or Mg2+ solution, we first derive formulas for pure Na+ and Mg2+ solutions. As we show below, the results for single species solution are the special limiting cases for more general results for mixed ions.

In Na+ solutions

Based on the predictions of the TBI model, we obtain the following fitted functions for the [Na+]-dependent ΔG°37, ΔS°, and Tm for RNA helix,

|

(13) |

|

(14) |

|

(15) |

where  is the mean electrostatic free energy per base stack.

is the mean electrostatic free energy per base stack.  is a function of [Na+] and helix length N:

is a function of [Na+] and helix length N:

|

(16) |

For a broad range of the Na+ concentration from 3 mM to 1 M, the above formulas give good fit with the TBI predictions for the folding free energy ΔG°37 (see Fig. 7 A) and good agreements with the experimental data for the melting temperature Tm (Fig. 8).

FIGURE 7.

The folding free energy ΔG°37 of RNA helix as functions of NaCl (A) and MgCl2 (B) concentrations for different sequences of various lengths. (A) CCAUGG, CCAUAUGG, GCCAGUUAA, AUUGGAUACAAA, and CCUUGAUAUCAAGG (from top to bottom). (B) CCAUGG, CCAUAUGG, AUUGGAUACAAA, and CCUUGAUAUCAAGG (from top to bottom). (Symbols) Predicted by the TBI model; (solid lines) the empirical relations Eq. 13 for NaCl and Eq. 17 for MgCl2.

FIGURE 8.

The melting temperature Tm of RNA helix as functions of NaCl concentration for different sequences of various lengths: CCUUGAUAUCAAGG of CS = 10−4 M, ACCGACCA/AGGCUGGA at CS = 9 μM, AUUGGAUACAAA of CS = 8 μM, CCAUGG of CS = 10−4 M, and AAAAAAAUUUUUUU of CS = 3.9 μM (from top to bottom). (Solid lines) Empirical extension for Na+ Eq. 15. (Symbols) Experimental data given in Fig. 5.

In Mg2+ solutions

Based on the free energy ΔG°37 calculated by the TBI model for pure Mg2+, we obtain the following expressions for [Mg2+]-dependent ΔG°37, ΔS°, and Tm for RNA helix:

|

(17) |

|

(18) |

|

(19) |

Here  is the electrostatic folding free energy per base stack, and is given by the following function of helix length N and the Mg2+ concentration:

is the electrostatic folding free energy per base stack, and is given by the following function of helix length N and the Mg2+ concentration:

|

(20) |

As shown in Fig. 7 B, the above formulas give good fit to the TBI-predicted ΔG°37.

In mixed Na+/Mg2+ solutions

For a mixed Na+/Mg2+ solution, from the TBI-predicted results, we have the following empirical formulas for RNA helix stability and melting temperature,

|

(21) |

|

(22) |

|

(23) |

where x1 and x2 stand for the fractional contributions of Na+ ions and Mg2+ to the whole stability, respectively, and are given by

|

(24) |

Here (x1, x2) = (1, 0) for a pure Na+ solution and (0, 1) for a pure Mg2+ solution. The values  and

and  are given by Eqs. 16 and 20 for pure Na+ and Mg2+ solutions, respectively. The value Δg12 is a crossing term for Na+-Mg2+ interference and is given by

are given by Eqs. 16 and 20 for pure Na+ and Mg2+ solutions, respectively. The value Δg12 is a crossing term for Na+-Mg2+ interference and is given by

|

(25) |

In a pure ionic solution, Δg12 = 0 and the formulas for mixed ion solution return to the results for the corresponding pure ionic solutions. The parameters at 1 M can be either calculated from the nearest-neighbor model (19–26) or obtained directly from experiments. Fig. 9 shows that the above expression for Tm (Eq. 23) gives good predictions for RNA helices as tested against the available experimental data (57) and the predictions from the PB theory.

FIGURE 9.

The melting temperature Tm of RNA helix as functions of MgCl2 concentration for mixed NaCl/MgCl2 solutions with different NaCl concentrations and for different sequences of various lengths. (A) CCAUGG of 10−4 M: [NaCl] = 0 M, 0.018 M, 0.1 M, and 1 M (from bottom to top); (B) CCAUAUGG of 10−4 M: [NaCl] = 0 M, 0.03 M, 0.1 M, and 1 M (from bottom to top); and (C) CCUUGAUAUCAAGG of 10−4 M: [NaCl] = 0 M, 0.03 M, 0.1 M, and 1 M (from bottom to top). (Solid lines) The empirical relation Eq. 23; (dotted lines) predicted by the PB theory. (Symbols) Experimental data, which are given in Fig. 6.

Na+ versus Mg2+ for RNA helix stability

Experiments show that a mixture of 10 mM Mg2+ and 150 mM Na+ is equivalent to 1 M Na+ in stabilizing a 6-bp DNA duplex (49), and a mixture of 10 mM Mg2+ and 50 mM Na+ is similar to 1 M Na+ in stabilizing a ribosomal RNA secondary structure (56). We have previously shown that 10 mM Mg2+ is slightly less efficient than 1 M Na+ for stabilizing a 9-bp DNA duplex with averaged sequence parameters (75).

Using the empirical expressions derived above, we can quantitatively compare RNA helix abilities in Na+ and Mg2+ solutions. To obtain a crude estimation, we use the mean enthalpy and entropy parameters averaged over different base stacks in 1 M NaCl: (

) = (−10.76 kcal/mol, −27.85 cal/mol/K) (26). Then ΔH = −10.76(N − 1) kcal/mol for an N-bp RNA helix. According to Eq. 23, for a 9-bp RNA duplex, the difference of the melting temperature ΔTm = Tm(1 M Na+) − Tm(10 mM Mg2+) is ∼−0.2°C. Therefore, 10 mM Mg2+ and 1 M Na+ solutions support approximately the same stability for a 9-bp RNA helix. The addition of Na+ in 10 mM Mg2+ would slightly destabilize the RNA duplex. For example, Tm would be lowered by 1.4°C for a 9-bp RNA helix if 50 mM Na+ is added to a 10 mM Mg2+ solution. As discussed above, this is because the added Na+ ions would counteract the efficient role of Mg2+.

) = (−10.76 kcal/mol, −27.85 cal/mol/K) (26). Then ΔH = −10.76(N − 1) kcal/mol for an N-bp RNA helix. According to Eq. 23, for a 9-bp RNA duplex, the difference of the melting temperature ΔTm = Tm(1 M Na+) − Tm(10 mM Mg2+) is ∼−0.2°C. Therefore, 10 mM Mg2+ and 1 M Na+ solutions support approximately the same stability for a 9-bp RNA helix. The addition of Na+ in 10 mM Mg2+ would slightly destabilize the RNA duplex. For example, Tm would be lowered by 1.4°C for a 9-bp RNA helix if 50 mM Na+ is added to a 10 mM Mg2+ solution. As discussed above, this is because the added Na+ ions would counteract the efficient role of Mg2+.

DNA helix stability in mixed Na+/Mg2+ solutions

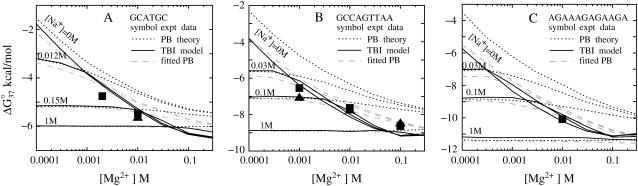

Although the [Na+]-dependence of DNA helix stability has been well studied based on the PB theory and the TBI model (44,75), quantitative understanding of DNA stability ΔG°37 in mixed Na+/Mg2+ solvent is relatively limited. Fig. 10 shows ΔG°37 versus [Mg2+] for different [Na+] values in a mixed Na+/Mg2+ solution for the three sequences GCATGC (49), GCCAGTTAA (53), and AGAAAGAGAAGA (55). The comparison between the TBI predictions and the available experimental data shows good agreements. From Figs. 4 and 10, we find that the stabilities of RNA and DNA helices have the same qualitative salt-dependence in a mixed salt solution.

FIGURE 10.

The folding free energy ΔG°37 of DNA helix as functions of MgCl2 concentration for mixed NaCl/MgCl2 solutions with different NaCl concentrations and for different DNA sequences. (A) GCATGC: [NaCl] = 0 M, 0.012 M, 0.15 M, and 1 M (from top to bottom); (B) GCCAGTTAA: [NaCl] = 0 M, 0.03 M, 0.1 M, and 1 M (from top to bottom); and (C) AGAAAGAGAAGA: [NaCl] = 0 M, 0.03 M, 0.1 M, and 1 M (from top to bottom). (Solid lines) Predicted by TBI model; (dotted lines) predicted by PB theory; (dashed lines) fitted PB by decreasing the Mg2+ radius to 3.5 Å. (Symbols) Experimental data: (A) ▪ GCATGC in mixed NaCl/MgCl2 solution with 0.012 M NaCl and 10 mM sodium cacodylate (49); and ▴ GCATGC in mixed NaCl/MgCl2 solution with 0.15 M NaCl and 10 mM sodium cacodylate (49). (B) ▪ GCCAGTTAA in MgCl2/10 mM sodium cacodylate solution (53); and ▴ GCCAGTTAA in mixed NaCl/MgCl2 solution with 0.1 M NaCl and 10 mM sodium cacodylate (53). (C) ▪ AGAAAGAGAAGA in MgCl2 solution with 50 mM HEPES (55).

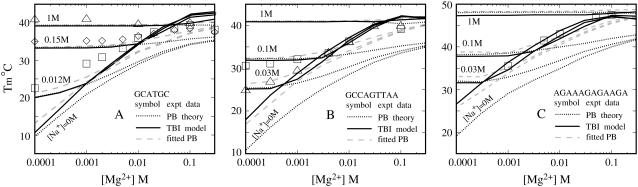

From the temperature-dependence of the folding free energy ΔG°T from Eq. 5, we obtain the melting temperature Tm in Eq. 6. In Fig. 11, we show the Tm-values for different sequences: GCATGC (49), GCCAGTTAA (53), and AGAAAGAGAAGA (55), as predicted from the experiments, the TBI model, and the PB theory. Fig. 11 shows the TBI predictions agree well with the experimental data, and the TBI model gives improved predictions over the PB theory. In a mixed salt solution with low NaCl concentration, the experimental Tm-values are slightly higher than those predicted by the TBI model, because the experimental buffers contain additional Na+ ions (from, e.g., sodium cacodylate) (49,53,55). The mean-field PB theory underestimates the role of Mg2+ ions in stabilizing DNA helix, especially for long helix, because PB ignores the correlated low-energy states (74–77). As shown in Figs. 10 and 11, PB could give better predictions if we decrease the Mg2+ ion radius.

FIGURE 11.

The melting temperature Tm of DNA helix as a function of MgCl2 concentration in mixed NaCl/MgCl2 solutions with different NaCl concentrations for different sequences. (A) GCATGC of CS = 10−4 M: [NaCl] = 0 M, 0.012 M, 0.15 M, and 1 M (from bottom to top); (B) GCCAGTTAA of CS = 8 μM: [NaCl] = 0M, 0.03 M, 0.1 M, and 1 M (from bottom to top); (C) AGAAAGAGAAGA of CS = 6 μM: [NaCl] = 0 M, 0.03 M, 0.1 M, and 1 M (from bottom to top). (Solid lines) Predicted by TBI model; (dotted lines) predicted by PB theory; (dashed lines) fitted PB by decreasing the Mg2+ radius to 3.5 Å. (Symbols) Experimental data: (A) □ GCATGC in mixed NaCl/MgCl2 solution with 0.012 M NaCl and 10 mM sodium cacodylate (49); ◊ GCATGC in mixed NaCl/MgCl2 solution with 0.15 M NaCl and 10 mM sodium cacodylate (49); Δ GCATGC in mixed NaCl/MgCl2 solution with 1 M NaCl and 10 mM sodium cacodylate (49). (B) Δ GCCAGTTAA in MgCl2/10 mM sodium cacodylate solution (53); and □ GCCAGTTAA in mixed NaCl/MgCl2 solution with 0.1 M NaCl and 10 mM sodium cacodylate (53). (C) □ AGAAAGAGAAGA in MgCl2 solution with 50 mM HEPES (55). Here, the data for AGAAAGAGAAGA is taken from the duplex melting in the study of triplex melting in MgCl2 solution and CS = 6 μM is the total strand concentration for triplex formation and the corresponding Tm is calculated from ΔG°–RTlnCS/6 = 0 (55).

As we predicted from the folding free energy, the addition of Na+ ions can destabilize the helix, which causes a lower Tm, and then the Na+-induced destabilization effect is stronger for long helices. For high Na+ concentration, Na+ ions can effectively push Mg2+ away from the helix surface and Na+ ions would dominate the helix stability. Consequently, Tm becomes close to the value of the Tm in pure Na+ solutions.

Thermodynamic parameters for DNA helix in Na+/Mg2+ mixed solution

For pure Na+ or Mg2+ solutions, previous studies have given several useful empirical expressions for thermodynamic parameters as functions of [Na+] or [Mg2+] and helix length (24,31,75). These expressions are practically quite useful for a broad range of biological applications such as the design of the ionic conditions for PCR and DNA hybridization (31,106). In this section, using the TBI model, we present a more general expression for the salt-dependent thermodynamic parameters, namely, the thermodynamic parameters in mixed Na+/Mg2+ salt condition. For mixed salt case, the computational modeling is particularly valuable because of the lacking of experimental data, especially for the folding free energy ΔG°T in the mixed salt. The calculated parameters are reliable because of agreements with available experimental results.

Using the results for the folding free energy ΔG°37 predicted from the TBI model for sequences with lengths of 6–15 bp (listed in Table 2), we obtain the following empirical expression for ΔG°37, ΔS°, and Tm,

|

(26) |

|

(27) |

|

(28) |

where x1 and x2, given by Eq. 24, are the fractional contributions of Na+ and Mg2+ respectively, and  and

and  are the mean electrostatic folding free energy per base stacks for DNA helix in a pure Na+ or Mg2+ solution, and are given by Tan and Chen (75):

are the mean electrostatic folding free energy per base stacks for DNA helix in a pure Na+ or Mg2+ solution, and are given by Tan and Chen (75):

|

(29) |

and

|

(30) |

Here, Δg12 is the crossing term for the effects of Na+ and Mg2+ and is given by Eq. 25. In Eq. 26, ΔG°37(1 M) is the folding free energy at 1 M NaCl, and N − 1 and N are the numbers of base stacks and basepairs in the DNA helix, respectively. Fig. 12 shows that the above expressions agree well with the available experimental data for DNA helix in mixed Na+/Mg2+ solutions (49,53,55).

FIGURE 12.

The melting temperature Tm of DNA helix as a function of MgCl2 concentration in mixed NaCl/MgCl2 solutions with different NaCl concentrations for different sequences. (A) GCATGC of CS = 10−4 M: [NaCl] = 0 M, 0.012 M, 0.15 M, and 1 M (from bottom to top); (B) GCCAGTTAA of CS = 8 μM: [NaCl] = 0 M, 0.03 M, 0.1 M, and 1 M (from bottom to top); (C) AGAAAGAGAAGA of CS = 6 μM: [NaCl] = 0 M, 0.03 M, 0.1 M, and 1 M (from bottom to top). (Solid lines) The fitted empirical relations Eq. 28; (dotted lines) predicted by PB theory; (symbols) experimental data given in Fig. 11.

Effects of the ssRNA structure

In the above calculations, we use a mean single-strand helix to represent the ensemble of ssRNA conformations. In this section, we investigate the sensitivity of our predictions of the helix stability to the structural parameters of ssRNA. For simplicity, we use an 8-bp RNA helix in pure Na+ and Mg2+ solutions as examples for illustration. As described in Appendix A, there are three major structural parameters for an ssRNA helix: rp, the radial coordinate of phosphates, Δz, the rise per nucleotide along axis, and Δθ, twist angle per residue. In the above calculations, the parameters used for ssRNA are (rp, Δz, Δθ) = (7 Å, 1.9 Å, 32.7°), where two adjacent nucleotides are separated by a distance of dp–p ≃ 4.4 Å. To study the effects of ssRNA structural parameters on the predicted helix stability, we test the following two cases: 1), we fix (rp, Δθ) = (7 Å, 32.7°) and change only the value of Δz; 2), we fix dp–p ≃ 4.4 Å and Δθ = 32.7°, and change rp and Δz concomitantly while keeping dp–p fixed.

First, we perform calculations for two values of Δz: 1.4 Å and 2.4 Å, corresponding to Δz smaller and larger than 1.9 Å (= the ssRNA helix parameter used in our calculations for RNA helix stability), respectively. As shown in Fig. 13, A and B, a larger Δz of ssRNA causes two effects: It lowers the dsRNA helix stability because it stabilizes the ssRNA by decreasing the electrostatic repulsion in ssRNA; and it causes a stronger ion concentration dependence of the helix stability. Larger Δz means smaller charge density of ssRNA, thus larger difference in the charge density between ssRNA and dsRNA. This would cause a stronger cation concentration-dependence of the stability shown as steeper curves in Fig. 13, A and B. Similarly, a smaller Δz would cause a weaker cation concentration dependence of the stability.

FIGURE 13.

The dsRNA helix folding stability ΔG°37 as functions of [Na+] (A,C) and [Mg2+] (B,D) concentrations for different structural parameters of ssRNA. Panels A and C are for pure Na+ solutions ([Mg2+] = 0 M), and panels B and C are for pure Mg2+ solutions ([Na+] = 0 M). (A,B) The radial distance of phosphates (rp) is fixed at 7 Å, while the rise along axis Δz varies. (C,D) Both rp and Δz are changed, but the distance between two adjacent phosphates is kept approximately constant.

Second, we use (rp, Δz) = (7.3 Å, 1.6 Å), and (6.5 Å, 2.3 Å), both with fixed dp–p ≃ 4.4 Å. Fig. 13, C and D, shows that the predicted ΔG°37 is nearly unchanged. This is because the charge density of ssRNA is approximately unchanged for the fixed dp–p. Thus the stability ΔG°37 is nearly unchanged.

From the above two test cases, we find that the theoretical predictions for the helix stability are stable for different ssRNA parameters with fixed dp–p. Strictly speaking, the structure of ssRNA is dependent on sequence, salt, and temperature. Furthermore, an ensemble of conformations for an ssRNA may exist. Therefore, it is a simplified approximation to use a mean structure to represent the ensemble of ssRNA structures (11,93,107), whose distribution is dependent on the temperature, sequence, and salt conditions. Such an approximation may attribute to the (slight) difference between our TBI results for the dsRNA helix stability and the experimental data.

CONCLUSIONS AND DISCUSSIONS

We have developed a generalized tightly bound ion (TBI) model to treat 1), RNA stability in both pure and mixed salt solutions; and 2), DNA helix stability in mixed Na+/Mg2+ solutions. Based on the TBI model, we investigate the thermal stability of RNA and DNA helices in the mixed Na+ and Mg2+ solutions for different helix lengths and different salt concentrations (0–1 M for Na+ and 0.1–0.3 M for Mg2+). The predicted folding free energy ΔG°37 and melting temperature Tm for the helix-coil transition agree with the available experimental data.

For the mixed Na+/Mg2+ solutions with different molar ratio, the helix stability has different behaviors for three distinctive ion concentration regimes: Na+-dominating, Na+/Mg2+ competing, and Mg2+-dominating. For the Na+-dominating case, both TBI model and PB theory can successfully predict thermodynamics of RNA and DNA helix stability. For the Na+/Mg2+ competition and Mg2+-dominating cases, the PB theory underestimates the roles of Mg2+ in stabilizing RNA and DNA helices, while the TBI model can give improved predictions. Moreover, in the Na+/Mg2+ competing regime, the addition of Na+ can slightly destabilizes the RNA and DNA helix stability, and such competition between Na+ and Mg2+ is stronger for longer helices.

Based on the predictions from the TBI model and the agreement between the predictions and experimental data, we obtain empirical formulas for the folding free energy and the melting temperature as functions of helix length and Na+/Mg2+ concentrations for both RNA and DNA helices. The empirical relations are tested against the available experimental results, and can be useful for practical use in predicting RNA and DNA helix stability in mixed Na+ and Mg2+ solutions.

Although the predictions from the TBI model agree with the available experimental data, the present studies for DNA and RNA helix stabilities are limited by several simplified assumptions. First, the helix stability calculation is based on the decoupled electrostatic and nonelectrostatic contributions. Second, the helix-coil transition is assumed to be a two-state transition between the mean structures of the double-stranded (ds) and the single-stranded (ss) helices, and the sequence and salt-dependence of the coil (modeled as ss helix) structure is neglected. In fact, ssDNA and ssRNA are denatured structures, which, depending on the sequence and ionic condition, can adopt an ensemble of different conformations (108,109). The sequence- and ion-dependent uncertainty of the ssDNA and ssRNA structures and the possible existence of partially unfolded intermediates may contribute to the theory-experiment differences, especially for RNAs, which can be quite flexible. Third, we neglect the heat capacity change in the helix to coil transition, which may also contribute to the difference between theoretical predictions and experimental results, especially when melting temperature is far away from 37°C. In addition, for bound ions, we neglect the possible dehydration effect (9), and neglect the binding of ions (including anions) to specific functional groups of nucleotides in the tightly bound region. The site-specific binding of dehydrated cations can make important contributions to the nucleic acid tertiary structure folding stability. In the simple DNA and RNA helical structures studied here, the effect of the binding to specific groups (sites) and the associated dehydration may be weaker than that in tertiary structure folding.

Acknowledgments

We thank Richard Owczarzy and Irina A. Shkel for helpful communications on modeling nucleic acid helix stability.

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of General Medical Sciences through grant No. GM063732 (to S.-J.C).

APPENDIX A: STRUCTURAL MODELS FOR dsRNA AND ssRNA

The dsRNA helix is modeled as an A-form helix (1). We use the grooved primitive model (74–78) to model the A-RNA helix. It has been shown that the grooved primitive model of DNA is able to give detailed ion distribution that agrees well with the all-atomic simulations (78). In the grooved primitive model, like that of DNA helix (74–78), an RNA helical basepair is represented by five spheres (74–77): one central large central sphere with radius 3.9 Å, two phosphate spheres with radii 2.1 Å, and two neutral spheres with radii 2.1 Å (78). For the canonical A-RNA, the coordinates of phosphate spheres ( ) are given by the canonical coordinates from x-ray measurements (104):

) are given by the canonical coordinates from x-ray measurements (104):  ; and

; and  where s = 1, 2 denotes the two strands and i = 1, 2, …N denotes the nucleotides on each strand. The parameters (

where s = 1, 2 denotes the two strands and i = 1, 2, …N denotes the nucleotides on each strand. The parameters (

) for the initial positions are (0°, 0 Å) for the first strand and (153.6°, 1.88 Å) for the second strand, respectively. The neutral spheres have the same angular coordinates except they have the smaller radial coordinates 5.8 Å (74–78); and the centers of the central large spheres are on the axis of DNA helix. Each phosphate sphere carries a point elementary charge −q at its center. In Fig. 1, we show a dsRNA helix produced from the primitive grooved model.

) for the initial positions are (0°, 0 Å) for the first strand and (153.6°, 1.88 Å) for the second strand, respectively. The neutral spheres have the same angular coordinates except they have the smaller radial coordinates 5.8 Å (74–78); and the centers of the central large spheres are on the axis of DNA helix. Each phosphate sphere carries a point elementary charge −q at its center. In Fig. 1, we show a dsRNA helix produced from the primitive grooved model.

Like ssDNA (75), we model ssRNA as a mean single helical structure averaged over the experimentally measured structures (105,110–114). We make use of the primitive grooved model-to-model ssRNA, and there are three structure parameters: radial coordinate of phosphates rp, twist angle per residue Δθ, and rise per basepair Δz. We use rp = 7 Å, and we take Δz = 1.9 Å and keep Δθ = 32.7°, which is the same as that of dsRNA. Δz(= 1.9 Å) is slightly smaller than that of ssDNA, which is in the same trend as the structural parameters fitted from the cylindrical PB model (43); see Appendix B. For ssRNA, the phosphate charge positions (ρi, θi, zi) can be given by the following equations: ρi = 7(Å); θi = i 32.73°; and zi = i 1.9(Å). The distance between two adjacent phosphates is ∼4.4 Å. As a control, we also perform the calculations for other two different sets of structure parameters for ssRNA: (Δθ, rp, Δz) = (32.73°, 7.3 Å, 1.6 Å) and (Δθ, rp, Δz) = (32.73°, 6.5 Å, 2.3 Å) and only found slight changes in the results, as shown in main text.

APPENDIX B: STRUCTURAL MODELS FOR DSDNA AND SSDNA

The dsDNA helix is modeled as the canonical B-form since it is the most common and stable form over a wide range of sequences and ionic conditions (1,105). In the grooved primitive model for DNA, a helical basepair is represented by five spheres (74–77): one large central sphere with radius 4 Å, two phosphate spheres with radii 2.1 Å, and two neutral spheres with radii 2.1 Å (78). The centers of the central large spheres are on the axis of DNA helix; the phosphate spheres are placed at the centers of the phosphate groups; the neutral spheres lie between phosphate spheres and central large one. The coordinates of phosphate spheres (

) are given by the canonical coordinates of B-DNA from x-ray measurements (103):

) are given by the canonical coordinates of B-DNA from x-ray measurements (103):  ; and

; and  where s = 1, 2 denotes the two strands and i = 1, 2, …N denotes the nucleotides on each strand. The parameters (

where s = 1, 2 denotes the two strands and i = 1, 2, …N denotes the nucleotides on each strand. The parameters ( ) for the initial position are (0°, 0 Å) for the first strand and (154.4°, 0.78 Å) for the second strand, respectively. The neutral spheres have the same angular coordinates except they have smaller radial coordinates 5.9 Å (74–78). Each phosphate sphere carries a point elementary charge −q at its center.

) for the initial position are (0°, 0 Å) for the first strand and (154.4°, 0.78 Å) for the second strand, respectively. The neutral spheres have the same angular coordinates except they have smaller radial coordinates 5.9 Å (74–78). Each phosphate sphere carries a point elementary charge −q at its center.

For ssDNA, we use the same helical structure as that used in our previous study (75), with the use of the grooved primitive model (74–78). We use rp = 7 Å and Δz = 2.2 Å, and keep Δθ = 36°, which is the same as that of dsDNA (75). Therefore, for ssDNA, the phosphate charge positions (ρi, θi, zi) can be given by the following equations (75): ρi = 7(Å); θi = i 36°; zi = i 2.2(Å) (75). As a control, we have performed calculations for other two different sets of structure parameters for ssDNA: (Δθ, rp, Δz) = (36°, 7.5 Å, 1.8 Å) and (Δθ, rp, Δz) = (36°, 6.4 Å, 2.6 Å) and found only negligible changes in the predictions.

APPENDIX C: FORMULAS FOR ΔGB AND ΔGD

In the calculation of ΔGb, the electrostatic interaction potential energy inside the tightly bound region Ub is given by the sum of all the possible pairwise charge-charge interactions (74–77),

|

(31) |

where uii is the Coulomb interactions between the charges in cell i and uij is the Coulomb interactions between the charges in cell i and in cell j. We compute the potential of mean force Φ1(i) for uii and Φ2(i, j) for uij (74–77) as

|

(32) |

The above averaging 〈…〉 is over all the possible positions (Ri, Rj) of the tightly bound ion(s) in the respective tightly bound cell(s). From Φ1(i) and Φ2(i, j), ΔGb is given by (74–77)

|

(33) |

To calculate ΔGd, we use the results of the mean-field PB theory for the diffusive ions (115,116), and we have (74–77)

|

(34) |

where the first and second integrals correspond to the enthalpic and entropic parts of the free energy, respectively. The value ψ′(r) is the electrostatic potential for the system without the diffusive salt ions. The value ψ′(r) is involved since ψ (r) − ψ′(r) gives the contribution of the diffusive ions to total electrostatic potential. The values ψ (r) and ψ′(r) are obtained from solving the nonlinear PB and the Poisson equation (salt-free), respectively.

APPENDIX D: SIMPLIFICATIONS FOR THE CALCULATIONS OF ΔGD

In the TBI model, we assume that the electrostatic potential outside the tightly bound region only depends on the equilibrium distribution of charges inside the tightly bound region (74–77). Thus, for each given number of total bound ions Nb (0 ≤ Nb ≤ 2N (76)), for a N-bp helix, we need to solve nonlinear PB and Poisson equations to obtain the free energy ΔGd (see Eq. 34) for the diffusive ions. We have developed a simplified algorithm to treat ΔGd. The essential idea of the simplification on PB-related calculations for ΔGd is to decrease the number of nonlinear PB equations and Poisson equations that need to be evaluated in the TBI theory. The simplification is based on the fact that the free energies ΔGd show smooth functional relations with the number of tightly bound ions (Nb) for different ion concentrations (shown in Fig. 14). Thus, the free energies (ΔGd) can be obtained from a fitted polynomial without solving PB and Poisson equation for each Nb (0 ≤ Nb ≤ 2N). In our present algorithm, we select eight specific Nb values (Nb = 0, N/4, N/2, 3N/4, N, 4N/3, 5N/3, and 2N). After obtaining ΔGd for these eight Nb by solving the PB and the Poisson equations, we fit the ΔGd-Nb relationship by a polynomial. The free energy ΔGd for any given Nb can be obtained from the fitted polynomial; see Fig. 14 for the comparisons between the values from the explicit PB calculations and those from the fitted polynomial. The two methods give almost exactly the same results for different ion concentrations. Based on the simplification, we only need to treat nonlinear PB equations (and Poisson equations) for several Nb even for longer polyanions, then the computational complexity of PB-related calculations is significantly reduced, especially for long helices.

FIGURE 14.

The free energy ΔGd for diffusive ions (which needs to be obtained by solving nonlinear PB and the corresponding Poisson equation, see Eq. 34) as a function of the number Nb of tightly-bound ions for different divalent ion concentrations: 0.001 M, 0.01 M, and 0.1 M. Here, the radii of divalent ions are taken as 3.5 Å and the temperature is 25°C. DNA helix is taken as 20-bp. For Mg2+ (with radius 4.5 Å), the Nb-dependence of ΔGd is less significant. (Symbols) Calculated from nonlinear PB for each Nb; (solid lines) from the polynomial functions fitted from the results for eight Nb-values.

APPENDIX E: PARAMETER SETS AND NUMERICAL DETAILS

In this study, ions are assumed to be hydrated (74–77), and the radii of hydrated Na+ and Mg2+ ions are taken as 3.5 Å and 4.5 Å (74–77,99), respectively. We also use smaller radius (∼3.5 Å) for Mg2+ to fit the PB predictions to the experimental data. In the computation with PB equation, the dielectric constant ε of molecule interior is set to be 12, an experimentally derived value (117), and ε of solvent is assumed to be the value of bulk water. At 25°C, the dielectric constant of water is ∼78. The temperature-dependence of solvent dielectric constant ε is accounted for by using the empirical function (118)

|

(35) |

where t is the temperature in Celsius.

Both the TBI and the PB calculations require numerical solution of the nonlinear PB. A thin layer of thickness of one cation radius is added to the molecular surface to account for the excluded volume layer of the cations (9,74–77). We also use the three-step focusing process to obtain the detailed ion distribution near the molecules (63,74–77). The grid size of the first run depends on the salt concentration used. Generally, we keep it larger than six times of Debye length to include all the ion effects in solutions, and the resolution of the first run varies with the grid size to make the iterative process viable within a reasonable computational time (74–77). The grid size (Lx, Ly, Lz) for the second and the third runs are kept at (102 Å, 102 Å, 136 Å) and (51 Å, 51 Å, 85 Å), respectively, and the corresponding resolutions are 0.85 Å per grid and 0.425 Å per grid, respectively. As a result, the number of the grid points is 121 × 121 × 161 in the second and 121 × 121 × 201 in the third run. Our results are tested against different grid sizes, and the results are robust.

References

- 1.Bloomfield, V. A., D. M. Crothers, and I. Tinoco, Jr. 2000. Nucleic Acids: Structure, Properties and Functions. University Science Books, Sausalito, CA.

- 2.Tinoco, I., and C. Bustamante. 1999. How RNA folds. J. Mol. Biol. 293:271–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson, C. F., and T. M. Record. 1995. Salt-nucleic acid interactions. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 46:657–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bloomfield, V. A. 1997. DNA condensation by multivalent cations. Biopolymers. 44:269–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brion, P., and E. Westhof. 1997. Hierarchy and dynamics of RNA folding. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 26:113–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pyle, A. M. 2002. Metal ions in the structure and function of RNA. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 7:679–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sosnick, T. R., and T. Pan. 2003. RNA folding: models and perspectives. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 13:309–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woodson, S. A. 2005. Metal ions and RNA folding: a highly charged topic with a dynamic future. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 9:104–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Draper, D. E., D. Grilley, and A. M. Soto. 2005. Ions and RNA folding. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 34:221–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rook, M. S., D. K. Treiber, and J. R. Williamson. 1999. An optimal Mg2+ concentration for kinetic folding of the Tetrahymena ribozyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:12471–12476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Misra, V. K., and D. E. Draper. 2001. A thermodynamic framework for Mg2+ binding to RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:12456–12461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heilman-Miller, S. L., D. Thirumalai, and S. A. Woodson. 2001. Role of counterion condensation in folding of the Tetrahymena ribozyme. I. Equilibrium stabilization by cations. J. Mol. Biol. 306:1157–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heilman-Miller, S. L., J. Pan, D. Thirumalai, and S. A. Woodson. 2001. Role of counterion condensation in folding of the Tetrahymena ribozyme. II. Counterion-dependence of folding kinetics. J. Mol. Biol. 309:57–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takamoto, K., Q. He, S. Morris, M. R. Chance, and M. Brenowitz. 2002. Monovalent cations mediate formation of native tertiary structure of the Tetrahymena thermophila ribozyme. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9:928–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Das, R., L. W. Kwok, I. S. Millett, Y. Bai, T. T. Mills, J. Jacob, G. S. Maskel, S. Seifert, S. G. J. Mochrie, P. Thiyagarajan, S. Doniach, L. Pollack, and D. Herschlag. 2003. The fastest global events in RNA folding: electrostatic relaxation and tertiary collapse of the Tetrahymena ribozyme. J. Mol. Biol. 332:311–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koculi, E., N. K. Lee, D. Thirumalai, and S. A. Woodson. 2004. Folding of the Tetrahymena ribozyme by polyamines: importance of counterion valence and size. J. Mol. Biol. 341:27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thirumalai, D., and C. Hyeon. 2005. RNA and protein folding: common themes and variations. Biochemistry. 44:4957–4970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lambert, M. N., E. Vocker, S. Blumberg, S. Redemann, A. Gajraj, J. C. Meiners, and N. G. Walter. 2006. Mg2+-induced compaction of single RNA molecules monitored by tethered particle microscopy. Biophys. J. 90:3672–3685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freier, S. M., R. Kierzek, J. A. Jaeger, N. Sugimoto, M. H. Caruthers, T. Neilson, and D. H. Turner. 1986. Improved free-energy parameters for predictions of RNA duplex stability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 83:9373–9377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breslauer, K. J., R. Frank, H. Blocker, and L. A. Marky. 1986. Predicting DNA duplex stability from the base sequence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 83:3746–3750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turner, D. H., and N. Sugimoto. 1988. RNA structure prediction. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 17:167–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.SantaLucia, J., H. T. Allawi, and P. A. Seneviratne. 1996. Improved nearest-neighbor parameters for predicting DNA duplex stability. Biochemistry. 35:3555–3562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sugimoto, N., S. I. Nakano, M. Yoneyama, and K. I. Honda. 1996. Improved thermodynamic parameters and helix initiation factor to predict stability of DNA duplexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:4501–4505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.SantaLucia, J., Jr. 1998. A unified view of polymer, dumbbell, and oligonucleotide DNA nearest-neighbor thermodynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:1460–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Owczarzy, R., P. M. Callone, F. J. Gallo, T. M. Paner, M. J. Lane, and A. S. Benight. 1998. Predicting sequence-dependent melting stability of short duplex DNA oligomers. Biopolymers. 44:217–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xia, T., J. SantaLucia, M. E. Burkard, R. Kierzek, S. J. Schroeder, X. Jiao, C. Cox, and D. H. Turner. 1998. Thermodynamic parameters for an expanded nearest-neighbor model for formation of RNA duplexes with Watson-Crick base pairs. Biochemistry. 37:14719–14735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]