Abstract

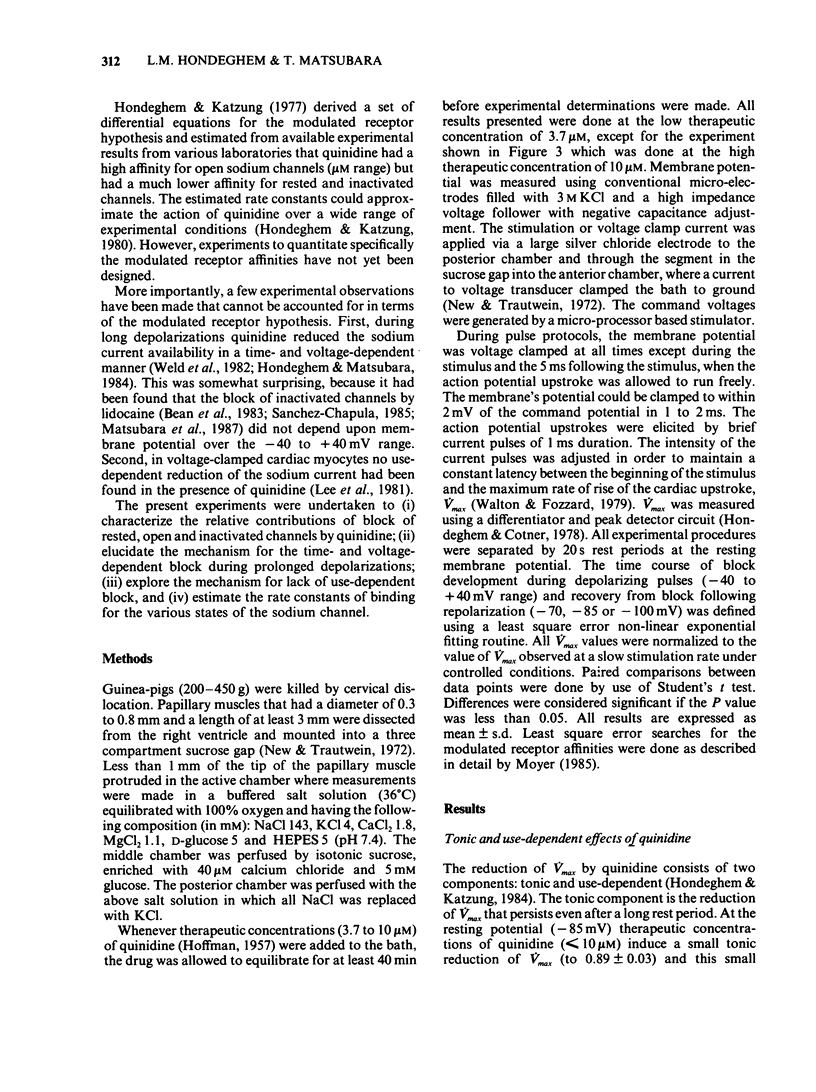

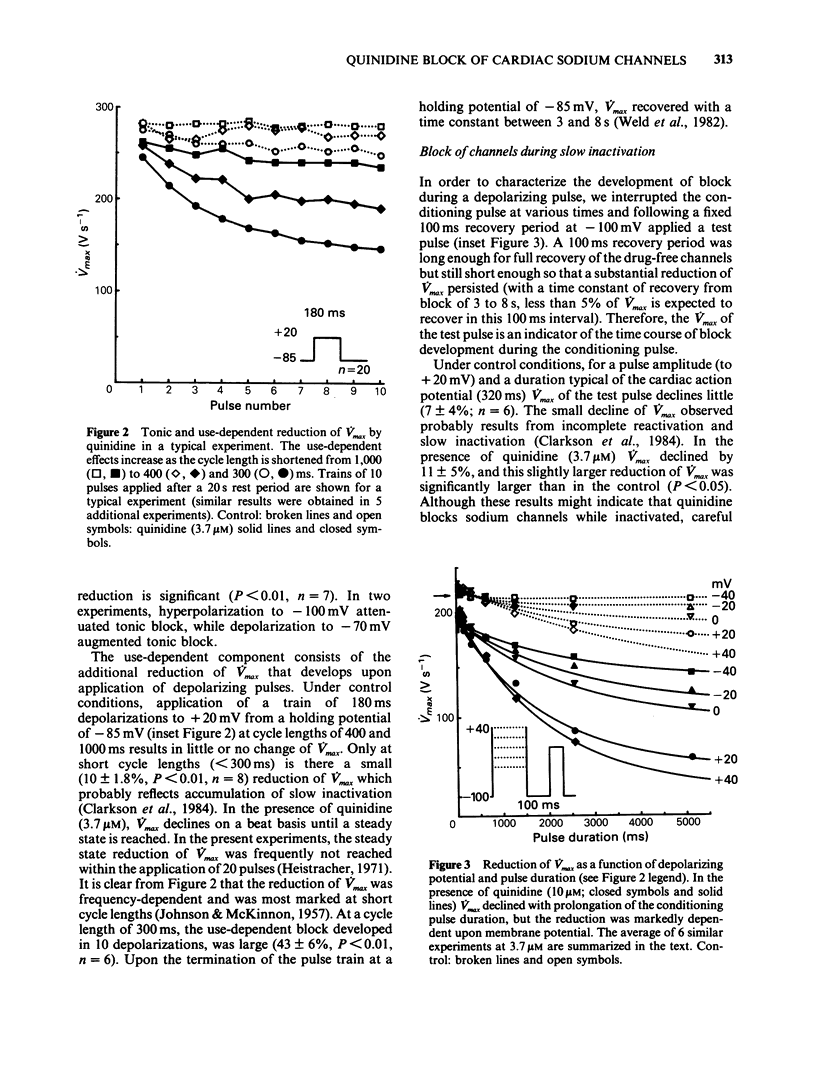

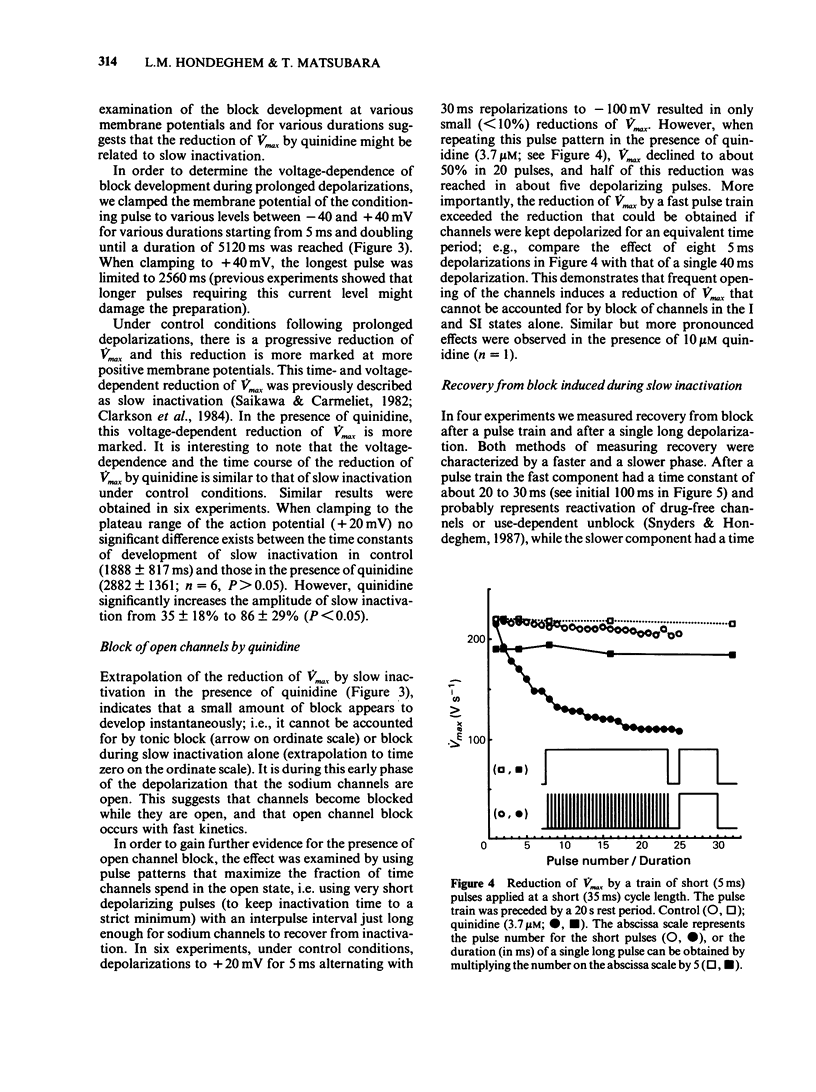

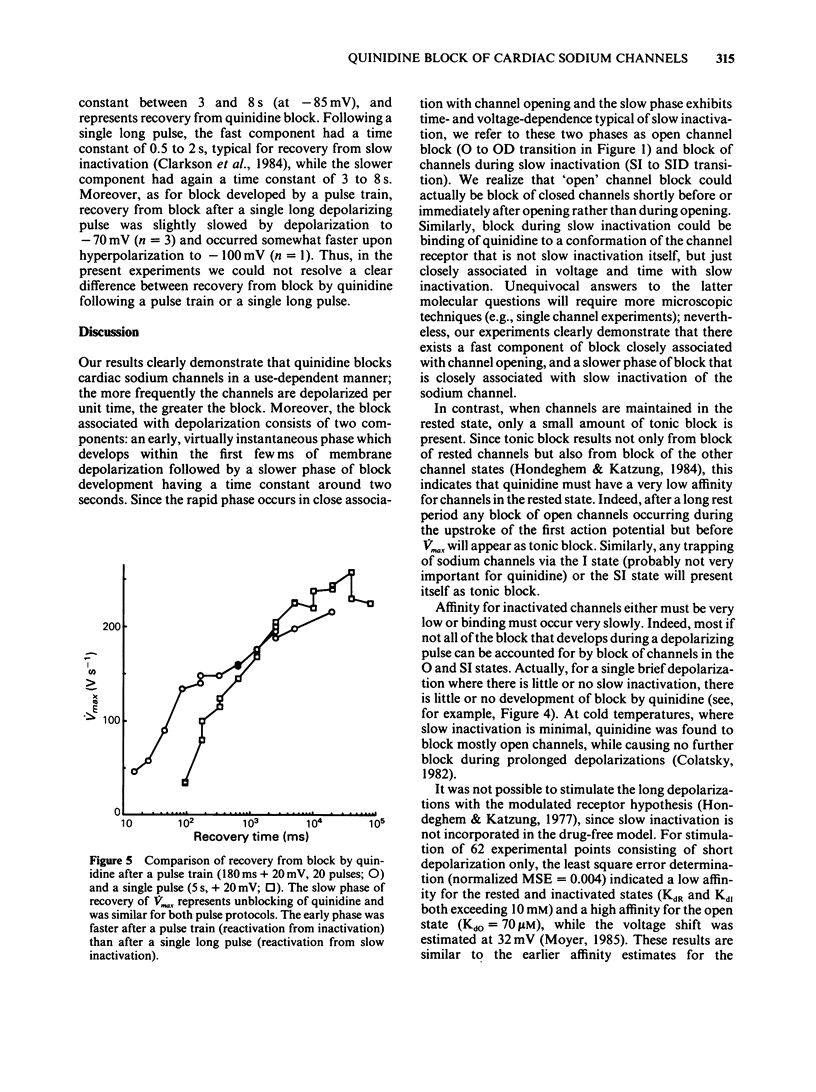

1. In order to quantify the time- and voltage-dependent block of sodium channels by quinidine, we voltage clamped guinea-pig papillary muscles and measured the maximum upstroke velocity (Vmax) of the cardiac action potential. 2. Quinidine reduces Vmax presumably by blocking cardiac sodium channels. In therapeutic concentrations, quinidine causes a small amount of tonic block. Upon depolarization of the cardiac cell membrane, a use-dependent block develops. 3. A slow component of use-dependent block has time- and voltage-dependence similar to that of slow inactivation, develops for the duration of the depolarization or until a steady state is reached. 4. In addition, closely associated with the action potential upstroke, a fraction of the channels blocks very quickly. This represents block of activated or open channels. 5. Near the normal resting potential, channels recover from block with a time constant of 3 to 8 s. At more negative membrane potentials recovery from block occurs slightly faster, while at more positive potentials recovery from block proceeds somewhat more slowly. 6. In terms of the modulated receptor hypothesis, quinidine has a low affinity for the rested state, avidly blocks open sodium channels, but does not bind significantly to inactivated channels. In addition, quinidine blocks channels as they exhibit slow inactivation.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bean B. P., Cohen C. J., Tsien R. W. Lidocaine block of cardiac sodium channels. J Gen Physiol. 1983 May;81(5):613–642. doi: 10.1085/jgp.81.5.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahalan M. D. Local anesthetic block of sodium channels in normal and pronase-treated squid giant axons. Biophys J. 1978 Aug;23(2):285–311. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(78)85449-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapula J. S. Interaction of lidocaine and benzocaine in depressing Vmax of ventricular action potentials. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1985 May;17(5):495–503. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(85)80054-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson C. W., Matsubara T., Hondeghem L. M. Slow inactivation of Vmax in guinea pig ventricular myocardium. Am J Physiol. 1984 Oct;247(4 Pt 2):H645–H654. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1984.247.4.H645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen C. J., Bean B. P., Tsien R. W. Maximal upstroke velocity as an index of available sodium conductance. Comparison of maximal upstroke velocity and voltage clamp measurements of sodium current in rabbit Purkinje fibers. Circ Res. 1984 Jun;54(6):636–651. doi: 10.1161/01.res.54.6.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant A. O., Strauss L. J., Wallace A. G., Strauss H. C. The influence of pH on th electrophysiological effects of lidocaine in guinea pig ventricular myocardium. Circ Res. 1980 Oct;47(4):542–550. doi: 10.1161/01.res.47.4.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HODGKIN A. L., HUXLEY A. F. A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. J Physiol. 1952 Aug;117(4):500–544. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heistracher P. Mechanism of action of antifibrillatory drugs. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmakol. 1971;269(2):199–212. doi: 10.1007/BF01003037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Local anesthetics: hydrophilic and hydrophobic pathways for the drug-receptor reaction. J Gen Physiol. 1977 Apr;69(4):497–515. doi: 10.1085/jgp.69.4.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hondeghem L. M., Cotner C. L. Measurement of Vmax of the cardiac action potential with a sample/hold peak detector. Am J Physiol. 1978 Mar;234(3):H312–H314. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1978.234.3.H312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hondeghem L. M., Katzung B. G. Antiarrhythmic agents: the modulated receptor mechanism of action of sodium and calcium channel-blocking drugs. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1984;24:387–423. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.24.040184.002131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hondeghem L. M., Katzung B. G. Time- and voltage-dependent interactions of antiarrhythmic drugs with cardiac sodium channels. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1977 Nov 14;472(3-4):373–398. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(77)90003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hondeghem L. M., Matsubara T. Quinidine and lidocaine: activation and inactivation block. Proc West Pharmacol Soc. 1984;27:19–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hondeghem L., Katzung B. G. Test of a model of antiarrhythmic drug action. Effects of quinidine and lidocaine on myocardial conduction. Circulation. 1980 Jun;61(6):1217–1224. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.61.6.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSON E. A., McKINNON M. G. The differential effect of quinidine and pyrilamine on the myocardial action potential at various rates of stimulation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1957 Aug;120(4):460–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. S., Hume J. R., Giles W., Brown A. M. Sodium current depression by lidocaine and quinidine in isolated ventricular cells. Nature. 1981 May 28;291(5813):325–327. doi: 10.1038/291325a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New W., Trautwein W. The ionic nature of slow inward current and its relation to contraction. Pflugers Arch. 1972;334(1):24–38. doi: 10.1007/BF00585998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saikawa T., Carmeliet E. Slow recovery of the maximal rate of rise (Vmax) of the action potential in sheep cardiac Purkinje fibers. Pflugers Arch. 1982 Jul;394(1):90–93. doi: 10.1007/BF01108313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyders D. J., Hondeghem L. M. Drug associated sodium channels inactivate and reactivate at more negative potentials than drug-free channels. Proc West Pharmacol Soc. 1987;30:149–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEIDMANN S. The effect of the cardiac membrane potential on the rapid availability of the sodium-carrying system. J Physiol. 1955 Jan 28;127(1):213–224. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1955.sp005250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEST T. C., AMORY D. W. Single fiber recording of the effects of quinidine at atrial and pacemaker sites in the isolated right atrium of the rabbit. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1960 Oct;130:183–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton M., Fozzard H. A. The relation of Vmax to INa, GNa, and h infinity in a model of the cardiac Purkinje fiber. Biophys J. 1979 Mar;25(3):407–420. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(79)85312-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weld F. M., Coromilas J., Rottman J. N., Bigger J. T., Jr Mechanisms of quinidine-induced depression of maximum upstroke velocity in ovine cardiac Purkinje fibers. Circ Res. 1982 Mar;50(3):369–376. doi: 10.1161/01.res.50.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh J. Z., Narahashi T. Kinetic analysis of pancuronium interaction with sodium channels in squid axon membranes. J Gen Physiol. 1977 Mar;69(3):293–323. doi: 10.1085/jgp.69.3.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]