Abstract

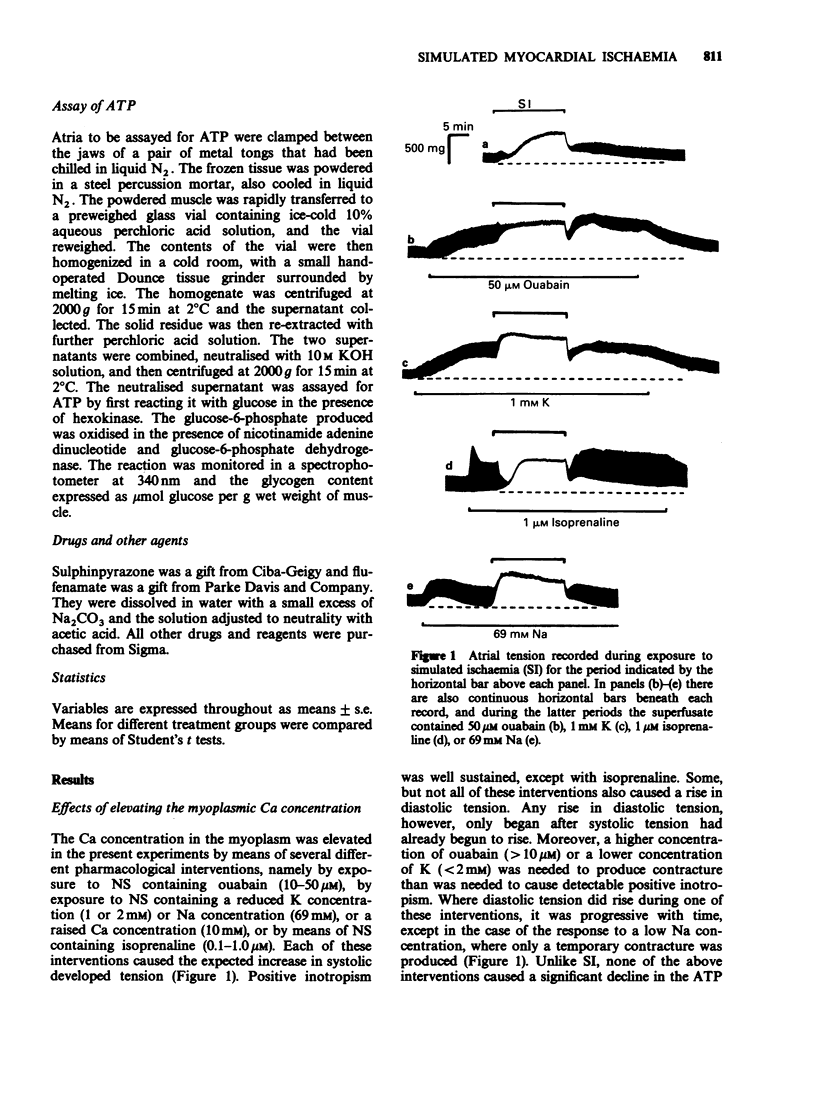

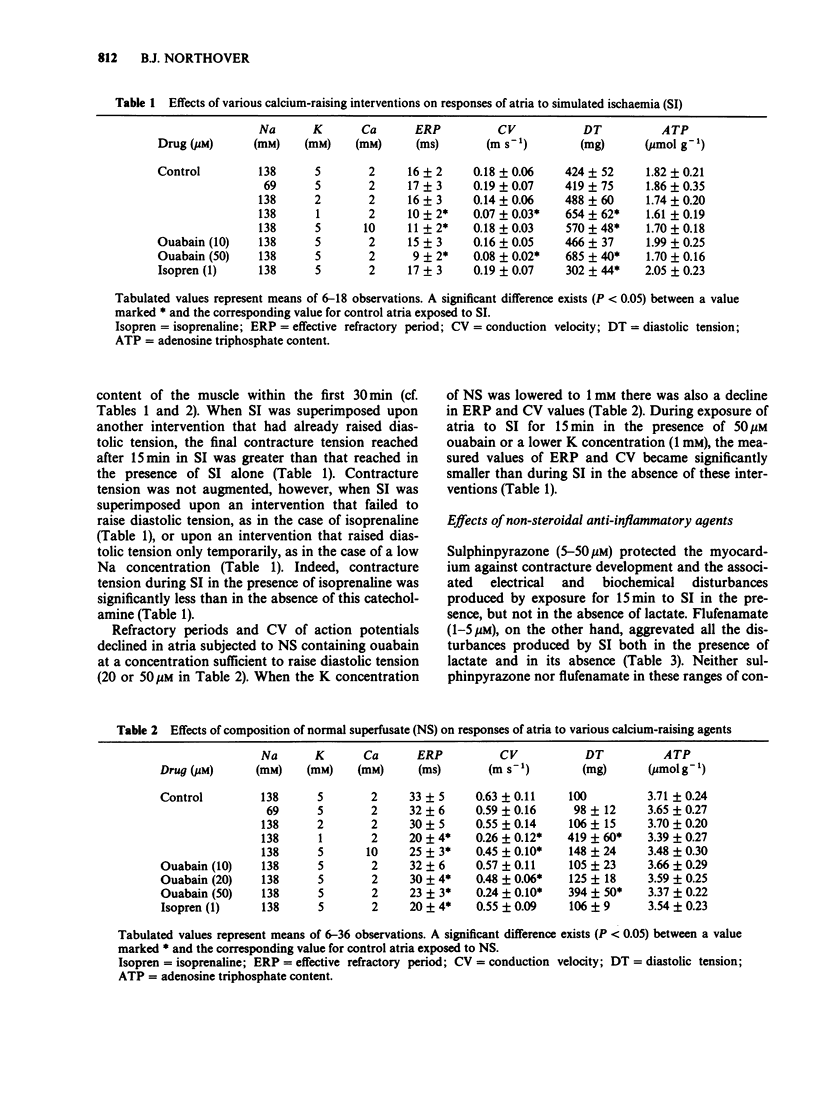

1. Rat isolated and superfused atria were exposed to a lactate-containing solution simulating the composition of extracellular fluid during myocardial ischaemia (SI). 2. Atria subjected to SI showed a decreased adenosine 5'-triphosphate (ATP) content, a rise in diastolic tension, a diminished conduction velocity of action potentials and shortened refractory periods. All these changes were less pronounced during lactate-free SI. 3. Atria preloaded with calcium displayed exaggerated responses measured electrically and mechanically during exposure to SI, whereas atria previously depleted of calcium displayed diminished electrical and mechanical responses to SI. Neither calcium loading nor calcium depletion modified the SI-induced depletion of the atrial stores of ATP. 4. Sulphinpyrazone protected atria against all aspects of the response to SI, but failed to protect the muscle under conditions of lactate-free SI. It is concluded that during SI, sulphinpyrazone protects against a lactate-mediated inhibition of the glycolytic synthesis of ATP. 5. Flufenamate exaggerated all responses of the atria to SI. These deleterious actions were still observed during lactate-free SI. It is concluded that flufenamate inhibits the synthesis of ATP in the mitochondria.

Full text

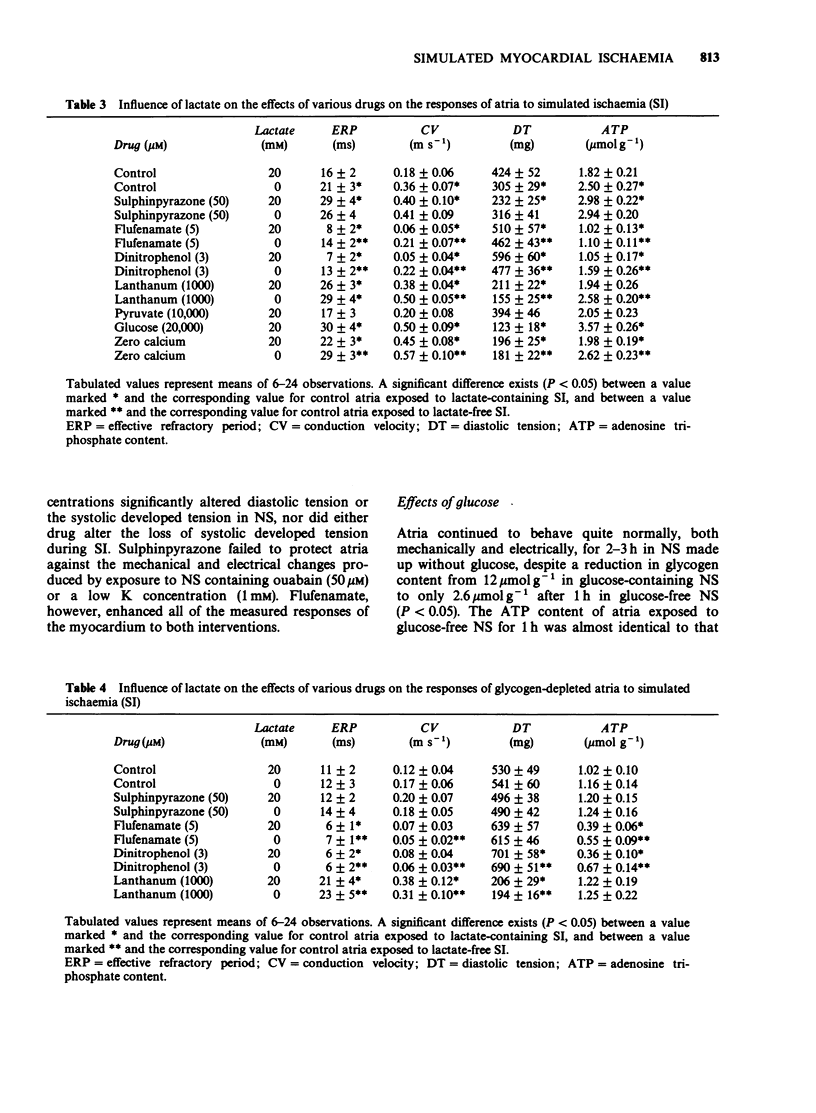

PDF

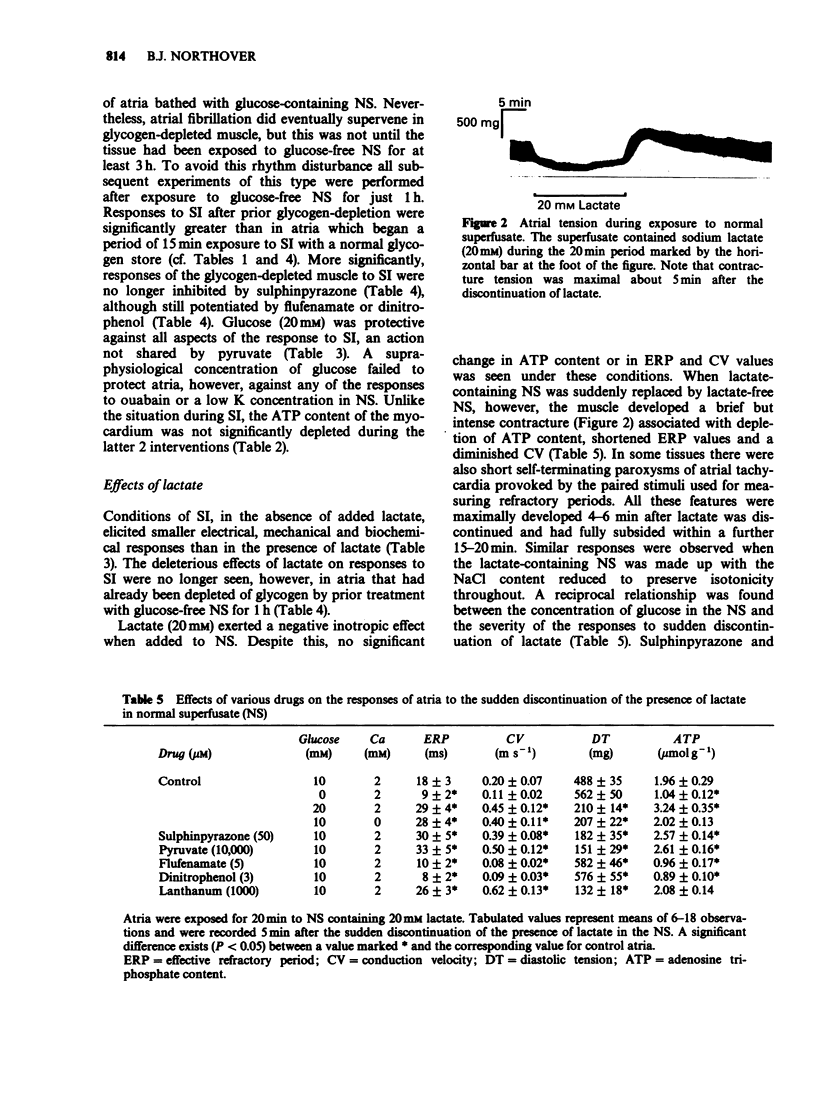

Selected References

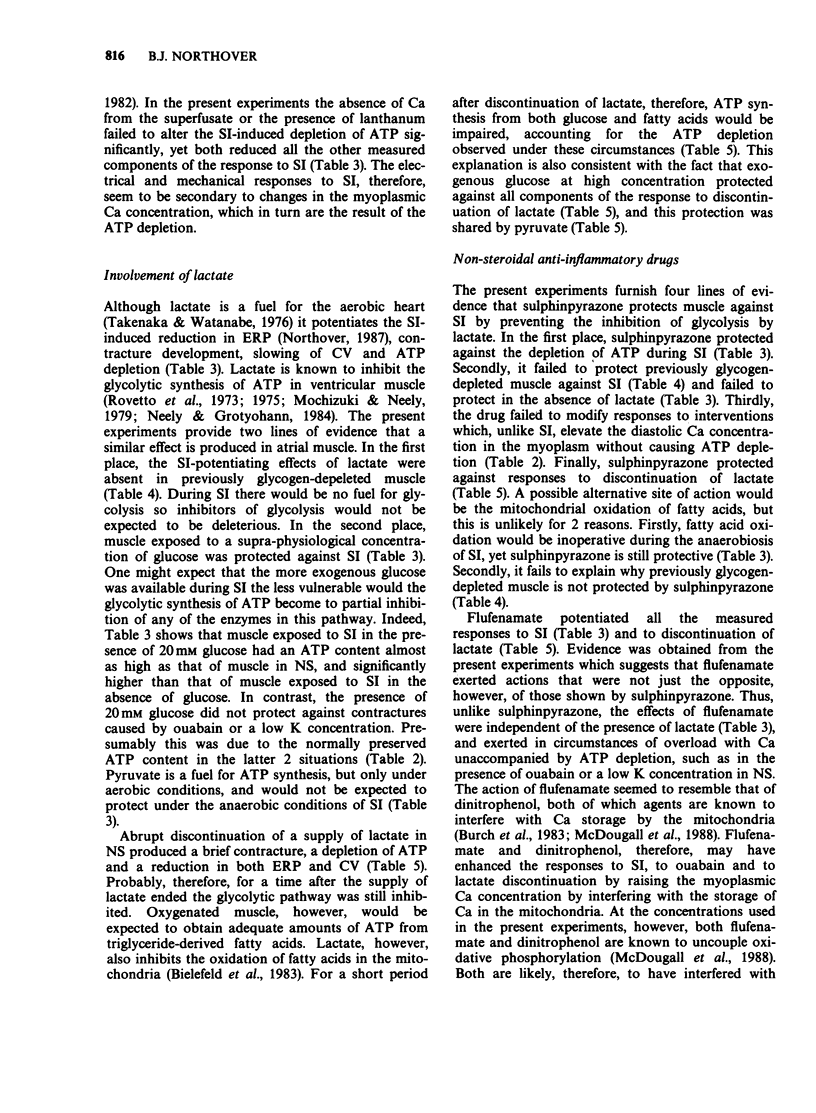

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Armiger L. C., Gavin J. B., Herdson P. B. Mitochondrial changes in dog myocardium induced by neutral lactate in vitro. Lab Invest. 1974 Jul;31(1):29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry W. H., Peeters G. A., Rasmussen C. A., Jr, Cunningham M. J. Role of changes in [Ca2+]i in energy deprivation contracture. Circ Res. 1987 Nov;61(5):726–734. doi: 10.1161/01.res.61.5.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry W. H., Smith T. W. Mechanisms of transmembrane calcium movement in cultured chick embryo ventricular cells. J Physiol. 1982 Apr;325:243–260. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burch R. M., Wise W. C., Halushka P. V. Prostaglandin-independent inhibition of calcium transport by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: differential effects of carboxylic acids and piroxicam. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1983 Oct;227(1):84–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoh M., Blinks J. R. Actions of sympathomimetic amines on the Ca2+ transients and contractions of rabbit myocardium: reciprocal changes in myofibrillar responsiveness to Ca2+ mediated through alpha- and beta-adrenoceptors. Circ Res. 1988 Feb;62(2):247–265. doi: 10.1161/01.res.62.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erne P., Hermsmeyer K. Desensitization to norepinephrine includes refractoriness of calcium release in myocardial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988 Feb 29;151(1):333–338. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(88)90598-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrier G. R., Moffat M. P., Lukas A. Possible mechanisms of ventricular arrhythmias elicited by ischemia followed by reperfusion. Studies on isolated canine ventricular tissues. Circ Res. 1985 Feb;56(2):184–194. doi: 10.1161/01.res.56.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham J. A., Lamb J. F. The effect of adrenaline on the tension developed in contractures and twitches of the ventricle of the frog. J Physiol. 1968 Jul;197(2):479–509. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guevara M. R., Shrier A., Glass L. Phase-locked rhythms in periodically stimulated heart cell aggregates. Am J Physiol. 1988 Jan;254(1 Pt 2):H1–10. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1988.254.1.H1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin Y., Doorey A., Barry W. H. Effects of calcium flux inhibitors on contracture and calcium content during inhibition of high energy phosphate production in cultured heart cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1984 Sep;16(9):823–834. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(84)80006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haworth R. A., Goknur A. B., Hunter D. R., Hegge J. O., Berkoff H. A. Inhibition of calcium influx in isolated adult rat heart cells by ATP depletion. Circ Res. 1987 Apr;60(4):586–594. doi: 10.1161/01.res.60.4.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavaler F., Morad M. Paradoxical effects of epinephrine on excitation-contraction coupling in cardiac muscle. Circ Res. 1966 May;18(5):492–501. doi: 10.1161/01.res.18.5.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakatta E. G., Lappé D. L. Diastolic scattered light fluctuation, resting force and twitch force in mammalian cardiac muscle. J Physiol. 1981 Jun;315:369–394. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod D. P., Prasad K. Influence of glucose on the transmembrane action potential of papillary muscle. Effects of concentration, phlorizin and insulin, nonmetabolizable sugars, and stimulators of glycolysis. J Gen Physiol. 1969 Jun;53(6):792–815. doi: 10.1085/jgp.53.6.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougall P., Markham A., Cameron I., Sweetman A. J. Action of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent, flufenamic acid, on calcium movements in isolated mitochondria. Biochem Pharmacol. 1988 Apr 1;37(7):1327–1330. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90790-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougall P., Markham A., Cameron I., Sweetman A. J. The mechanism of inhibition of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation by the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent diflunisal. Biochem Pharmacol. 1983 Sep 1;32(17):2595–2598. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(83)90024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochizuki S., Neely J. R. Control of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in cardiac muscle. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1979 Mar;11(3):221–236. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(79)90437-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy E., Jacob R., Lieberman M. Cytosolic free calcium in chick heart cells. Its role in cell injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1985 Mar;17(3):221–231. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(85)80005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy E., LeFurgey A., Lieberman M. Biochemical and structural changes in cultured heart cells induced by metabolic inhibition. Am J Physiol. 1987 Nov;253(5 Pt 1):C700–C706. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1987.253.5.C700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy J. G., Smith T. W., Marsh J. D. Calcium flux measurements during hypoxia in cultured heart cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1987 Mar;19(3):271–279. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(87)80594-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neely J. R., Grotyohann L. W. Role of glycolytic products in damage to ischemic myocardium. Dissociation of adenosine triphosphate levels and recovery of function of reperfused ischemic hearts. Circ Res. 1984 Dec;55(6):816–824. doi: 10.1161/01.res.55.6.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northover A. M., Northover B. J. Protection of rat atrial myocardium against electrical, mechanical and structural aspects of injury caused by exposure in vitro to conditions of simulated ischaemia. Br J Pharmacol. 1988 Aug;94(4):1207–1217. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb11640.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northover B. J. Electrical changes produced by injury to the rat myocardium in vitro and the protective effects of certain antiarrhythmic drugs. Br J Pharmacol. 1987 Jan;90(1):131–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1987.tb16832.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pressler M. L., Elharrar V., Bailey J. C. Effects of extracellular calcium ions, verapamil, and lanthanum on active and passive properties of canine cardiac purkinje fibers. Circ Res. 1982 Nov;51(5):637–651. doi: 10.1161/01.res.51.5.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray K. P., England P. J. Phosphorylation of the inhibitory subunit of troponin and its effect on the calcium dependence of cardiac myofibril adenosine triphosphatase. FEBS Lett. 1976 Nov;70(1):11–16. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(76)80716-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovetto M. J., Lamberton W. F., Neely J. R. Mechanisms of glycolytic inhibition in ischemic rat hearts. Circ Res. 1975 Dec;37(6):742–751. doi: 10.1161/01.res.37.6.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovetto M. J., Whitmer J. T., Neely J. R. Comparison of the effects of anoxia and whole heart ischemia on carbohydrate utilization in isolated working rat hearts. Circ Res. 1973 Jun;32(6):699–711. doi: 10.1161/01.res.32.6.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeki K., Muraoka S., Yamasaki H. Anti-inflammatory properties of N-phenylanthranilic acid derivatives in relation to uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1972 Apr;22(2):187–199. doi: 10.1254/jjp.22.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G. L., Allen D. G. Effects of metabolic blockade on intracellular calcium concentration in isolated ferret ventricular muscle. Circ Res. 1988 Jun;62(6):1223–1236. doi: 10.1161/01.res.62.6.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenbergen C., Murphy E., Levy L., London R. E. Elevation in cytosolic free calcium concentration early in myocardial ischemia in perfused rat heart. Circ Res. 1987 May;60(5):700–707. doi: 10.1161/01.res.60.5.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takenaka F., Watanabe A. Effects of iodoacetate and anoxia on phosphate metabolism in isolated perfused rat hearts. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1976 Jul;222(1):55–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]