Abstract

Anaplasma phagocytophilum, an obligatory intracellular bacterium that causes human granulocytic anaplasmosis, has significantly less coding capacity for biosynthesis and central intermediary metabolism than do free-living bacteria. Thus, A. phagocytophilum needs to usurp and acquire various compounds from its host. Here we demonstrate that the isolated outer membrane of A. phagocytophilum has porin activity, as measured by a liposome swelling assay. The activity allows the diffusion of l-glutamine, the monosaccharides arabinose and glucose, the disaccharide sucrose, and even the tetrasaccharide stachyose, and this diffusion could be inhibited with an anti-P44 monoclonal antibody. P44s are the most abundant outer membrane proteins and neutralizing targets of A. phagocytophilum. The P44 protein demonstrates characteristics consistent with porins of gram-negative bacteria, including detergent solubility, heat modifiability, a predicted structure of amphipathic and antiparallel β-strands, an abundance of polar residues, and a C-terminal phenylalanine. We purified native P44s under two different nondenaturing conditions. When reconstituted into proteoliposomes, both purified P44s exhibited porin activity. P44s are encoded by approximately 100 p44 paralogs and go through extensive antigenic variation. The 16-transmembrane-domain β-strands consist of conserved P44 N- and C-terminal regions. By looping out the hypervariable region, the porin structure is conserved among diverse P44 proteins yet enables antigenic variation for immunoevasion. The tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle of A. phagocytophilum is incomplete and requires the exogenous acquisition of l-glutamine or l-glutamate for function. Efficient diffusion of l-glutamine across the outer membrane suggests that the porin feeds the Anaplasma TCA cycle and that the relatively large pore size provides Anaplasma with the necessary metabolic intermediates from the host cytoplasm.

Anaplasma phagocytophilum is the causative agent of an emerging infectious disease called human granulocytic ehrlichiosis or anaplasmosis (HGE or HGA), one of the most prevalent life-threatening tick-borne zoonoses in North America (2, 3, 6). A. phagocytophilum is an obligate intracellular bacterium in the order Rickettsiales. All members of the order Rickettsiales have limited biosynthetic capability due to the loss of many genes present in the closely related free-living α-Proteobacteria during reductive genome evolution (4). These bacteria therefore cannot survive extracellularly and are obliged to import large varieties of nutrients and metabolic products from their host cells. As gram-negative bacteria, rickettsiae have two lipid bilayer membranes, i.e., inner and outer membranes. In order for small hydrophilic compounds, such as sugars, amino acids, or ions, to pass through the outer membrane, most gram-negative bacteria have special proteins, called porins, on the outer membrane which function as passive diffusion channels (20, 22). Porins also allow the diffusion of antibiotics. Despite the potential importance of porins for rickettsial physiology, pathogenesis, and chemotherapy, the porin activities of these pathogens have not been reported until now.

The best-studied outer membrane protein of A. phagocytophilum is P44. P44 is the immunodominant, most abundant outer membrane protein and is encoded by a polymorphic multigene family (40). Notably, 113 p44 genes are present in the A. phagocytophilum genome, including 22 full-length, 64 silent/reserve (without a start codon), 21 fragmented (containing only the 5′ or 3′ conserved region), and 6 truncated (containing a portion of the hypervariable region and a portion of either the 5′ or 3′ conserved region) p44 genes (4). There is one major expression site for p44, termed the p44 (msp2) expression locus (1, 16). Expression of either a full-length or silent/reserve p44 gene occurs after the hypervariable region of that p44 gene replaces the p44 gene currently occupying the p44 expression locus by nonreciprocal recombination in a RecF-dependent manner (16, 17). Each expressed p44 gene can be identified by its signature central hypervariable sequence. Among all of the p44 genes, 65 (71 if duplicated p44 genes in the genome are included) have been found thus far to be expressed in cell culture, HGA patients, experimentally infected mice and horses, or ticks (5, 14-16, 18, 36, 40, 42). Expansion of the P44 family is thought to provide a diverse antigenic population for establishing new infections in regions where A. phagocytophilum is endemic. It also allows antigenic variation to persist in immunocompetent mammals to allow effective tick transmission, because A. phagocytophilum cannot be transmitted transovarially in the vector tick.

However, the biological functions of P44 for the bacterium have been unknown. Therefore, in the present study, we first examined the pore-forming activity of the isolated outer membrane fraction of A. phagocytophilum, using an in vitro proteoliposome swelling assay, and whether this activity is inhibited by an anti-P44 monoclonal antibody (MAb). We then purified native P44s under two different nondenaturing conditions and examined whether P44s have pore-forming activity. Third, we analyzed how such hypervariable proteins can serve as porins by secondary structure prediction. In the context of the limited biosynthetic capability of A. phagocytophilum, the implication of P44 as a porin facilitates the investigation of A. phagocytophilum physiology and pathogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

A. phagocytophilum strain HZ (29) was propagated in HL-60 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (U.S. Biotechnologies, Parker Ford, PA) and 2 mM l-glutamine (Invitrogen). Cultures were incubated at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2-95% air atmosphere.

Outer membrane fraction preparation.

A. phagocytophilum-infected HL-60 cells (>95% infectivity) were collected by centrifugation at 200 × g for 5 min, and both the pellet and the supernatant were saved. The pellet was resuspended in RPMI medium and sonicated twice for 7 s each at setting 2.5, using a W-380 sonicator (Heat Systems, Farmingdale, NY) with a microtip. After sonication, the suspension was centrifuged at 400 × g for 10 min to remove cell debris and unbroken host cells. The supernatant was combined with the culture supernatant before sonication and passed sequentially through syringe-driven 5-μm nylon and 2.7-μm glass fiber membrane filters (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The filtrate was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C to pellet the A. phagocytophilum organism. The outer membrane fraction was obtained from the isolated A. phagocytophilum organism by using 0.1% N-lauroyl sarcosine (Sarkosyl; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) as previously described (25).

Outer membrane solubilization.

The outer membrane fraction that was insoluble in 0.1% Sarkosyl was washed with 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 10 min to remove residual Sarkosyl. The pellet was resuspended in 2% n-octylglucopyranoside (OG; Sigma), incubated at 37°C for 10 min, and then centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was used for an in vitro proteoliposome swelling assay. The outer membrane fraction solubilized with OG was evaluated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and stained with GelCode blue according to the manufacturer's instructions (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc., Rockford, IL). Gel pictures were taken with a Fuji LAS3000 imaging system (Fuji Film Medical Systems USA, Stamford, CT).

In vitro proteoliposome swelling assay.

Porin activity was determined by the reconstituted liposome swelling assay as previously described (23), with slight modifications. Egg phosphatidylcholine (2.4 μmol) (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL) and 0.2 μmol of dicetylphosphate (Sigma) dissolved in chloroform-methanol (2:1 [vol/vol]) were mixed and dried under a stream of N2 at the round bottom of a test tube. The lipid film was resuspended in 0.2 ml of water or water containing the purified protein or the outer membrane fraction. The resuspension step was completed by vortexing and finally by a brief (1 to 2 min) sonication in a Branson bath-type 1510 sonicator (Branson Ultrasonic, Danbury, CT). The lipid-protein mixture was then dried. To make proteoliposomes, the dried protein-lipid film was resuspended in 0.3 ml of 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, containing 15% (wt/vol) dextran T-40 (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ). Proteoliposome swelling was measured by recording the optical density at 400 nm every 2 s after diluting 17-μl proteoliposome suspensions in 600-μl solutions containing various concentrations of various solutes in a quartz cuvette, using a Spectramax Plus 384 plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) at 25°C. The tetrasaccharide stachyose (Sigma) was used to determine the isosmotic concentration for the liposomes without proteins. The permeability of the proteoliposome for the monosaccharides arabinose (Sigma) and glucose (GIBCO-BRL, Grand Island, NY), the disaccharide sucrose (Sigma), stachyose, and the amino acid l-glutamine (Sigma) was tested.

Porin activity of the outer membrane treated with MAb 5C11.

The outer membrane fraction (pellet) was resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (137 mM NaCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 2.7 mM KCl, 1.8 mM KH2PO4 [pH 7.2]) and divided into two tubes. The anti-P44 N terminus MAb 5C11 (immunoglobulin G2b [IgG2b]) was added to one tube, and isotype-matched control mouse IgG2b was added to another tube. The samples were then incubated at room temperature for 1 h with rotation. Pellets were collected by centrifugation at 18,000 × g for 10 min. Pellets were washed once with 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), solubilized in 2% OG in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. After incubation, the samples were centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 10 min to collect the supernatant. The solubilized membrane fraction was used for the liposome swelling assay.

Heat modifiability of P44.

After the addition of SDS-PAGE sample buffer to the outer membrane fraction solubilized in 2% OG, one-half of the sample was boiled for 5 min, and the other half was incubated at room temperature. After electrophoresis, the gel was stained with GelCode blue. In addition, Western blotting was performed to detect P44s, using MAb 5C11 as the primary antibody. Peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD) diluted 1:1,000 was used as the secondary antibody, and reacting bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence by incubating the membrane with ECL Western blotting detection reagents (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). Images were then captured using an LAS3000 image documentation system.

P44 purification from SDS-PAGE gel.

A. phagocytophilum outer membrane proteins were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE, with reduced concentrations of SDS in the sample buffer (final concentration, 0.4% SDS), running buffer (final concentration, 0.02% SDS), and gel (final concentration, 0.02% SDS). One lane of the gel was cut and stained with GelCode blue to visualize the positions of the P44s. The band (molecular mass of around 36 kDa) distinct from that of denatured P44s (molecular mass of around 44 kDa) was cut, minced, and passively eluted with 2% OG in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) with overnight rotation at 4°C. The mixture was then centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 10 min to collect the supernatant, which contained the eluted P44s. The eluate was concentrated by vacuum evaporation and dialyzed against 1% OG in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) in D-tube dialysis tubes (Novagen, San Diego, CA).

P44 purification by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

The outer membrane fraction (pellet) was resuspended in 0.5 ml 1% dithiothreitol (Sigma) in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and incubated at room temperature for 10 min, with rotation. Next, 0.5 ml 3% iodoacetamine (Sigma) in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) was added to the suspension and incubated for an additional 10 min, with rotation. After incubation, the outer membrane fraction was pelleted by centrifugation at 18,000 × g for 10 min. The pellet was washed once with 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), solubilized in 2% OG in 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0), and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. After incubation, the sample was centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 10 min to collect the supernatant. The solubilized membrane fraction was concentrated to 100 μl by evaporation, filtered through a 0.22-μm filter, and loaded onto a TSK gel G3000 SWXL column (Tosho Bioscience LLC, Montgomeryville, PA) equilibrated with 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0), 0.5 M NaCl, and 1% OG in an ÁKTA purifier system (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). Proteins were eluted with the same buffer at a flow rate of 1 ml/min, and the absorbance was monitored at 280 nm. Fractions (0.25 ml each) of the eluted proteins were obtained for peak areas. Molecular masses of eluted proteins were calculated based on the standard curve for a gel filtration standard (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Fifty microliters from each fraction was precipitated by adding 50 μl 20% trichloroacetic acid, mixed, incubated on ice for 30 min, and then centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 15 min. Pellets were resuspended in SDS-PAGE sample buffer and boiled for 5 min. After SDS-PAGE, the gels were stained with GelCode blue. Samples containing P44s without detectable contaminants were dialyzed against 1% OG in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and then concentrated by evaporation. After concentration, samples were dialyzed again in 1% OG in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) before being used for the liposome swelling assay.

P44 secondary structure prediction.

The P44-18 secondary structure was predicted by hydrophobicity and the hydrophobic moment profile method (8, 9). Briefly, the membrane criterion (hydrophobic moment [for either a normal β-strand or a twisted β-strand] plus mean hydrophobicity of the window [nine amino acid residues long in this case]) was plotted along the entire sequence. Continuous peaks with six or more amino acid residues above the cutoff of 1.5 were considered transmembrane β-strands. Both normal β-strand and twisted β-strand predictions were considered. When there was a discrepancy between the two results, the prediction with the longer transmembrane strand was selected.

Statistical analysis.

The unpaired Student t test was applied to assess differences among swelling rates. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

In vitro porin activity of the outer membrane fraction of A. phagocytophilum.

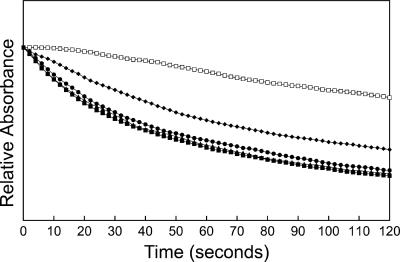

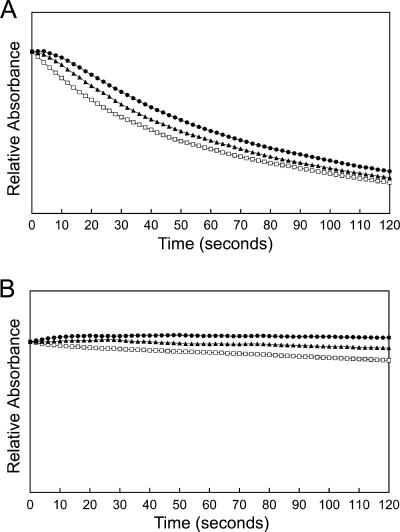

The liposome swelling assay for the study of porin function was used not only because it is well established but also because this assay affords precise information on the rates of diffusion of solutes through the porin channels (24). This assay involves the formation of liposomes incorporating a putative pore-forming protein and then determinations of whether and how fast test solutes can diffuse through the protein channels. The porin activity of A. phagocytophilum N-lauroyl sarcosine (Sarkosyl)-insoluble outer membrane proteins solubilized by OG was determined by an in vitro osmotic swelling assay with reconstituted proteoliposomes. The isosmotic concentration of 33 mM was determined with tetrasaccharide stachyose solutes for liposomes devoid of proteins. The detergents used in this study, including Sarkosyl and OG, did not influence the liposome swelling assay, as liposomes made in the presence of 20 μl (the same volume as samples containing proteins) of 0.1% or 0.01% Sarkosyl and 2% or 1% OG in the absence of protein did not swell or shrink in isosmotic stachyose and arabinose solutes (data not shown). The monosaccharides arabinose and glucose and the disaccharide sucrose were transported efficiently (Fig. 1). Even the tetrasaccharide stachyose could be diffused, although at a much lower rate than those for mono- or disaccharides. To verify the ability of stachyose to permeate membranes, the effects of different concentrations of stachyose on swelling rates of proteoliposomes reconstituted with outer membrane proteins were examined. When large amounts of outer membrane proteins were reconstituted into proteoliposomes, they swelled in the presence of hyperosmotic, isosmotic, and hypo-osmotic stachyose solutes (Fig. 2A). A slight shrinkage of the proteoliposomes in hyperosmotic stachyose solution could be observed only when a minimum protein amount (0.63 μg) was used (Fig. 2B). The permeability of proteoliposomes toward arabinose and stachyose was proportionate to the amount of outer membrane proteins used in the proteoliposome preparation (Fig. 3), but the swelling rate for proteoliposomes in stachyose was much lower than that for proteoliposomes in arabinose (Fig. 3). These results indicate that the A. phagocytophilum porin channel is much larger than those of well-studied porins (OmpC and OmpF) from Escherichia coli, which allow effective diffusion of monosaccharides, but not disaccharides, in a similar liposome swelling assay (24). In addition, the A. phagocytophilum outer membrane was permeable to l-glutamine (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Optical density changes in liposomes reconstituted with A. phagocytophilum outer membrane proteins diluted in an isosmotic concentration of solutes of various sizes. The proteoliposomes reconstituted with 3 μg of A. phagocytophilum outer membrane proteins were diluted in isosmotic solutions of 33 mM stachyose (□), 33 mM arabinose (▪), 33 mM l-glutamine (▴), 33 mM glucose (•), and 33 mM sucrose (⧫). The y axis represents a range of A400 values of 0.2. The traces were made after some vertical displacement so that they all started from the same initial point for easy comparison. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

FIG. 2.

Effects of different concentrations of stachyose on the diffusion rate of proteoliposomes reconstituted with A. phagocytophilum outer membrane proteins. A total of 10 μg (A) or 0.63 μg (B) of A. phagocytophilum outer membrane proteins were reconstituted into proteoliposomes. Proteoliposomes were diluted in 25 mM (□), 33 mM (▴), and 40 mM (•) stachyose solutions. The y axis represents a range of A400 values of 0.25. The traces in each panel were made after some vertical displacement so that they all started from the same initial point for easy comparison. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

FIG. 3.

Diffusion rates of proteoliposomes reconstituted with different amounts of A. phagocytophilum outer membrane proteins. Different amounts of A. phagocytophilum outer membrane proteins (0 to 12 μg) were reconstituted into proteoliposomes. Proteoliposome suspensions were diluted in a 33 mM isosmotic arabinose or stachyose solution. The change in optical density at 400 nm (OD400) was recorded, and the initial rates of OD400 decrease in arabinose (•) and stachyose (○) were calculated using readings from between 10 and 20 s after the start of the reading. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

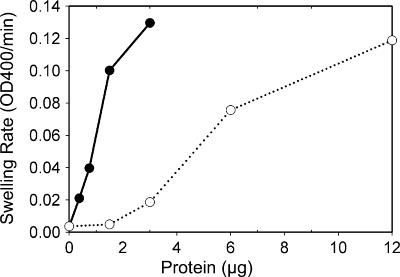

Porin activity of outer membrane treated with MAb 5C11.

P44s are surface exposed, and MAbs against P44s can neutralize A. phagocytophilum infection in vitro (35). We examined whether the porin activity of the A. phagocytophilum outer membrane fraction is inhibited when it is pretreated with MAb 5C11, specific to P44s. After preincubation of the outer membrane fraction with MAb 5C11 or the isotype control, the total amount of OG-solubilized outer membrane proteins treated with MAb 5C11 was the same as that of proteins treated with the isotype control MAb. The P44 protein amounts were also the same between these two treatment groups. When reconstituted into proteoliposomes, the outer membrane proteins treated with MAb 5C11 showed a distinctly reduced swelling pattern compared to that for proteins treated with the isotype control (Fig. 4A). Figure 4B shows significantly reduced swelling rates for the outer membrane proteins treated with MAb 5C11 than for those treated with the isotype control. These results suggest that P44s are porins and further indicate that MAb 5C11 has the ability to block their pore-forming activity.

FIG. 4.

Effect of MAb 5C11 on diffusion rate of proteoliposomes reconstituted with outer membrane proteins. (A) Optical density changes in MAb 5C11-treated (▵) and IgG2b isotype control-treated (▪) outer membrane proteins (0.88 μg) reconstituted into proteoliposomes. The proteoliposome suspensions were diluted in an isosmotic 33 mM arabinose solution. The traces were made after some vertical displacement so that they all start from the same initial point for easy comparison. The y axis represents a range of A400 values of 0.1. (B) Swelling rate of proteoliposomes reconstituted with MAb 5C11- or IgG2b isotype control-treated A. phagocytophilum outer membrane proteins (0.80 μg). The swelling rate was calculated using readings of the OD400 decrease between 0 and 60 s after the start of reading. Data are presented as means and standard deviations for triplicate samples. *, significant difference from isotype control (P < 0.05). Results shown are representative of two independent experiments.

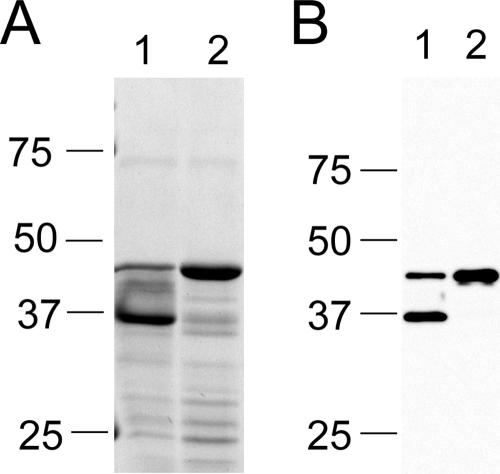

Heat modifiability of P44s.

The characteristics of porins of gram-negative bacteria include OG solubility, a predicted structure of amphipathic and antiparallel β-strands, an abundance of polar residues, a C-terminal phenylalanine, and heat modifiability (20). Heat modifiability means that proteins are relatively resistant to SDS treatment and thus remain folded in SDS-PAGE sample buffer without boiling conditions. Heat modifiability was thought to be related to the β-barrel structure in the porin (20). Folded proteins migrate faster in SDS-PAGE gels because of their condensed conformation. P44s have a predicted structure of amphipathic and antiparallel β-strands (35), an abundance of polar residues, and a C-terminal phenylalanine. OG-solubilized outer membrane proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis in SDS-PAGE sample buffer, with or without boiling of samples (Fig. 5A). Proteins in the range of 36 to 44 kDa were the major proteins found. These major proteins were P44s, as detected by Western blot analysis using MAb 5C11, which is specific to the N-terminal conserved region of P44s (35) (Fig. 5B). Based on both the GelCode blue-stained SDS-PAGE gel and Western blot results, P44s are soluble in OG, with more P44s migrating as 36-kDa proteins when the outer membrane samples were not heated in SDS-PAGE sample buffer and the majority of P44s migrating as 44-kDa proteins after being boiled, indicating that the 36-kDa protein was condensed P44 and the 44-kDa protein was totally denatured P44. The heat modifiability of P44 supports the presence of a β-barrel structure.

FIG. 5.

Heat modifiability of P44s. A. phagocytophilum outer membrane proteins were subjected to 12% SDS-PAGE, followed by either GelCode blue staining (A) or Western blotting using MAb 5C11 as the primary antibody (B). A. phagocytophilum outer membrane proteins in the SDS-PAGE sample buffer were treated at room temperature (lanes 1) or boiled for 5 min (lanes 2). Numbers to the left of each panel show molecular mass standards in kDa. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

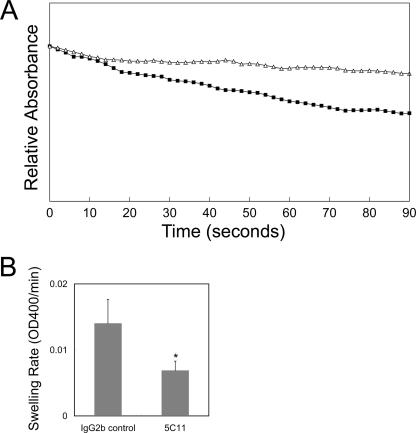

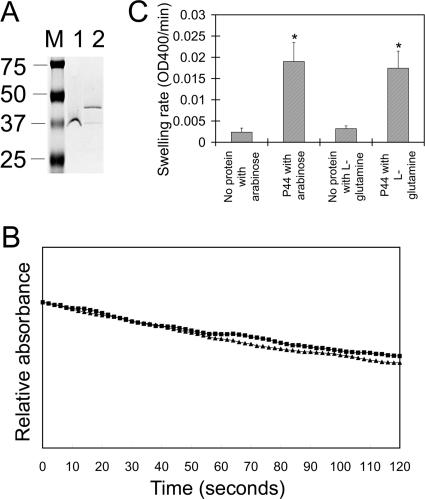

Porin activity of gel-purified P44.

The protein corresponding to nondenatured P44 (molecular mass of around 36 kDa) was eluted from the gel, dialyzed, and concentrated in the presence of 1% OG to prevent it from denaturation. The pore-forming activity of gel-purified P44 (Fig. 6A) was determined by reconstitution into proteoliposomes and by osmotic swelling. Purified P44-reconstituted proteoliposomes were permeable for arabinose and l-glutamine (Fig. 6B). The swelling rates of the P44-reconstituted proteoliposomes in isosmotic arabinose and l-glutamine were significantly higher than those of proteoliposomes containing no proteins in isosmotic arabinose or l-glutamine (Fig. 6C). Purified P44-reconstituted proteoliposomes were permeable for l-glutamine at a rate comparable to that for arabinose (Fig. 6C).

FIG. 6.

Pore-forming activity of gel-purified P44. (A) Gel-eluted P44 proteins (0.62 μg/lane) and molecular size standards (M) were subjected to SDS-PAGE with 0.02% SDS (final concentration) in running buffer, followed by GelCode blue staining. Gel-purified P44 proteins were treated in SDS-PAGE sample buffer with 0.4% SDS (final concentration) at room temperature (lane 1) or treated in standard SDS sample buffer and boiled for 5 min (lane 2). Numbers to the left of the panel show the molecular mass standards in kDa. (B) Optical density changes in proteoliposomes reconstituted with gel-purified P44. A total of 2.5 μg of gel-purified P44s were reconstituted into proteoliposomes. The proteoliposome suspensions were diluted in isosmotic 33 mM arabinose (▴) and 33 mM l-glutamine (▪) solutions. The traces were made after some vertical displacement so that they all start from the same initial point for easy comparison. The y axis represents a range of A400 values of 0.1. (C) Swelling rates of proteoliposomes reconstituted with purified P44s in the presence of arabinose and l-glutamine. A total of 2.5 μg of gel-purified P44s were reconstituted into proteoliposomes. The swelling rate was calculated using readings of the OD400 decrease between 0 and 60 s after the start of reading. Data are presented as means and standard deviations of triplicate samples. *, significant difference from proteoliposomes without proteins in the presence of arabinose or l-glutamine (P < 0.05). Results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

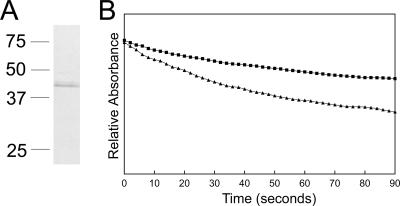

Porin activity of HPLC-purified P44s.

To confirm the porin activity of the gel-purified P44s, P44s were purified under nondenaturing conditions from the outer membrane fraction pretreated with dithiothreitol to reduce disulfide bonds among outer membrane proteins. After examination of the protein composition in each fraction from HPLC, one fraction containing P44s with a calculated molecular size of 36 kDa and no other bands visible by GelCode blue staining (Fig. 7A) was selected for porin activity analysis. This fraction had a stronger activity than the gel-purified P44 proteins, as indicated by the rapid swelling in isosmotic arabinose and stachyose (Fig. 7B); presumably, the rapid procedure without the use of any SDS more effectively prevented the denaturation of P44 proteins. The swelling rate was comparable to that measured for a similar amount of outer membrane proteins. This result supports the observation that P44s are porins.

FIG. 7.

Pore-forming activity of HPLC-purified P44s. (A) HPLC-purified P44s. The fractions containing P44s and the least contaminants were subjected to 12% SDS-PAGE followed by GelCode blue staining. The HPLC fraction showed a protein with a 36-kDa calculated molecular mass. The molecular mass of denatured P44 proteins was approximately 44 kDa. Numbers to the left of the panel show the molecular mass standards in kDa. (B) Optical density changes in proteoliposomes reconstituted with HPLC-purified P44s. A total of 1.2 μg of HPLC-purified P44s were reconstituted into proteoliposomes. The proteoliposome suspensions were diluted in isosmotic 33 mM stachyose (▪) and 33 mM arabinose (▴) solutions. The y axis represents a range of A400 values of 0.2.

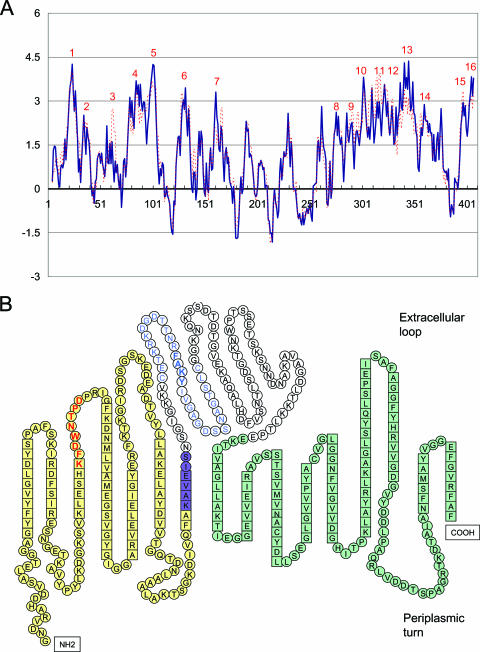

Secondary structure prediction for P44-18.

P44s have central hypervariable regions flanked by conserved N- and C-terminal sequences (40). In order to understand how such hypervariable proteins can serve as porins, the secondary structure of mature P44s (after cleavage of the signal peptide) was determined by a method previously described as useful for porin structure prediction (8, 9, 20). This method uses the sum of the hydrophobicity and the hydrophobic moment of each nine-residue segment to detect transmembrane strands. A strong peak indicates the strong probability of a transmembrane domain, and a trough indicates the strong probability of a loop. A. phagocytophilum HZ cultured in HL-60 cells mostly expresses P44-18 by reverse transcription-PCR as well as by immunofluorescence labeling using MAb 3E65, specific to P44-18 (35), and thus the membrane criterion profile for P44-18 is shown in Fig. 8A. According to the criteria described in Materials and Methods, there are 16 amphipathic and antiparallel β-strands predicted for P44-18 (Fig. 8B). There are two long stretches of β-strands predicted, between strands 4 and 5 and between strands 10 and 14. They are divided into β-strands with about 10 residues each by a residue(s) at the deepest gorge, with an additional single flanking residue on both ends. The last residue in β-strand 7 has a membrane criterion value of >1.49, close to the cutoff of 1.5, and was considered to be in the β-strands. All 16 β-strands were detected in the N- and C-terminal conserved regions or the semiconserved region between the N-terminal conserved region and the central hypervariable region (Fig. 8B). Approximately 37% (26/70) of expressed P44s carry this semiconserved region. Even though some P44s carry different amino acids in the semiconserved region, all of them tend to form similar β-strand structures at this position (data not shown). These prediction results are in agreement with our previous observation that MAb 5C11 and MAb 3E65 epitopes are exposed on the bacterial surface (Fig. 8B) (35). The hypervariable regions of different P44s did not change the secondary structure, since this region constitutes one extracellular exposed loop (Fig. 8B). Like the predominantly helical periplasmic domains at the C termini of E. coli OmpA (34) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa OprF (32), these hypervariable regions were easily denatured in SDS-PAGE buffer, even at room temperature, and gave P44s enough of a negative charge to migrate in SDS-PAGE gels, because they were not part of the stable β-barrel structure. But the β-barrel was probably the region responsible for the heat modifiability of P44s, because the β-barrel structure was not opened in the SDS-PAGE sample buffer without boiling, and P44s under this condition were in a more condensed form and migrated faster in the SDS-PAGE gel than they did with boiling.

FIG. 8.

Secondary structure prediction for P44-18. (A) Membrane criterion profile for P44-18. The solid blue line shows normal β-strands. The dotted red line shows twisted β-strands. The x axis shows the amino acid number, starting from the N terminus of mature P44-18. Numbers in red at the top of each peak are predicted β-strands, from the N to the C terminus. (B) Secondary structure drawing based on results from panel A, showing individual amino acids. Amino acids in boxes are predicted to be in β-strands, and amino acids in circles are predicted to be in the extracellular loop or periplasmic turn. Amino acids with a yellow background are in the N-terminal conserved region, amino acids with a purple background are semiconserved amino acids at the border of the N-terminal conserved region and the central hypervariable region, amino acids with a green background are in the C-terminal conserved region, and amino acids without any background are in the central hypervariable region. Amino acids in bold red form the epitope recognized by MAb 5C11, amino acids in blue show the C-C region (35), and those in bold form the epitope recognized by MAb 3E65 within the hypervariable region.

DISCUSSION

The P44 protein demonstrated characteristics consistent with those of porins of gram-negative bacteria. These shared features include outer membrane localization with a typical signal peptide, OG solubility, heat modifiability, a total of 16 predicted amphipathic and antiparallel β-strands, an abundance of polar residues, and a C-terminal phenylalanine (20). All 16 β-strands were predicted to be formed by conserved or semiconserved amino acid sequences in the N and C termini of P44-18. This implies that all P44s are capable of forming similar structures to that of P44-18, because they have conserved N and C termini. Recombination between a donor p44 gene outside the expression site and the one at the expression site needs the conserved 5′ and 3′ nucleotide sequences (17). At the protein level, conserved N and C termini may be required to form the conserved structure. Different porins are often expressed in different environmental situations (21). P44s differentially expressed by A. phagocytophilum under different conditions (36, 40-42) may have different properties: in addition to providing antigenic variations, this may also affect A. phagocytophilum's physiologic activities under these conditions. In addition, our previous study showed that the P44 protein concentration per bacterium is reduced at a lower culture temperature than 37°C (42), implying that the concentration of P44 protein in the membrane may be used to regulate the overall transport activity.

Porins normally function as trimers (22), although some are monomers (23, 33). In either case, each monomer forms a hydrophilic channel. In most cases, 16 transmembrane β-strands form a barrel-like channel (20). Occasionally, 18-β-strand barrels can also be seen (20). A report by Park et al. indicates surface oligomerization of P44/MSP2 as well as heteromeric complexes (27). Oligomeric structures were not detectable in the isolated membrane fraction, perhaps because the structure may become unstable in SDS-PAGE after Sarkosyl treatment.

Based on our data, P44s have pore-forming activity. First, since the porin is a passive diffusion channel, a large amount (a few μg) of the protein is required to clearly demonstrate its pore-forming activity in the liposome swelling assay. The P44 proteins purified by either method (HPLC or SDS-PAGE) did not have contaminating proteins detectable by GelCode blue staining (detection limit, 8 ng protein/lane [according to the manufacturer's instructions]). It is unlikely that such a small amount of contaminating protein accounts for the entire pore-forming activity observed in the present study. Second, it is unlikely that P44 proteins purified by two different methods (HPLC and SDS-PAGE) were consistently contaminated with the same protein accounting for the entire pore-forming activity demonstrated in the present study. Third, the antigenic epitope of MAb 5C11 is KFDWNTPD (35), and this sequence was not detected in any predicted proteins of A. phagocytophilum other than P44s. Thus, it is unlikely that MAb 5C11 inhibited the pore-forming activity of other proteins. Fourth, in the genome sequence data for A. phagocytophilum (4), we did not find any other protein in the 44-kDa-molecular-mass range which is predicted to have a β-barrel structure except for an outer membrane efflux protein TolC homolog (APH1110) and MSP2 family proteins (APH1325 and APH1017). However, TolC requires the trimeric complex to make a pore (30). The trimeric TolC complex is much larger than 44 kDa and was thus unlikely to contaminate the purified P44s in our study. Protein identification by capillary-liquid chromatography-nanospray tandem mass spectrometry revealed P44-18ES but no other protein predicted to have a β-barrel structure in this mass range (Mingqun Lin and Yasuko Rikihisa, unpublished data). Therefore, even if TolC and MSP2s have pore-forming activity and consistently contaminate the P44 protein fraction, their amounts are too small to account for the entire pore-forming activity observed. The present porin studies were conducted with native proteins. The protocol was developed to prevent the protein from denaturing during multiple steps involved in the extraction of P44s from obligatory intracellular bacteria. The recombinant P44s were obtained under denaturing conditions (41). When exactly refolded or nondenatured recombinant full-length P44s that are free of E. coli porin can be obtained in the future, this will allow direct testing of the role of conserved P44 N and C termini in porin activity. Additional characterization of porin activity for P44s, especially P44 species with different hypervariable region sequences, will aid in understanding the functions of differentially expressed P44s and their role in pathogenesis.

Our study showed that l-glutamine diffuses through the A. phagocytophilum porin. The tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle of A. phagocytophilum is incomplete, because one gene for isocitrate dehydrogenase is missing from the genome (KEGG pathway database [http://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html]) (GenBank accession no. CP000235). In A. phagocytophilum, in order for the TCA cycle to function, 2-oxoglutarate or glutamate is required. A. phagocytophilum has the enzyme GMP synthase (glutamine hydrolyzing) (GenBank accession no. YP_505762), which can convert l-glutamine to l-glutamate. Thus, the porin likely feeds the A. phagocytophilum TCA cycle. Neorickettsia sennetsu, which is closely related to A. phagocytophilum, has a similar TCA cycle defect to that of A. phagocytophilum (KEGG pathway database [http://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html]). A Neorickettsia sp. was shown to metabolize exogenous l-glutamine to generate CO2 and ATP (19, 28, 37). Similarly, Chlamydia lacks genes for three enzymes in the TCA cycle and for GMP synthase (KEGG pathway database) (11, 31). In chlamydiae, PorB, a substrate-specific porin for dicarboxylates such as 2-oxoglutarate, feeds the TCA cycle (11, 31). Unlike Chlamydia, A. phagocytophilum lacks genes for glycolysis (4). This suggests that P44s have a critical role in providing Anaplasma with carbon and energy sources.

Because porins are surface exposed, they are accessible to the host immune system and are generally good vaccine candidates (7, 26, 38). In this regard, antibodies against P44s are present in HGA patients and experimentally infected horses (36, 41). MAbs 5C11 and 3E65 can neutralize A. phagocytophilum infection in vitro (35). The reason why inhibition of porin activity with MAb 5C11 was not 100% has not been determined. It is possible that the epitope is not the optimum location or length for effective inhibition. Another possibility is that A. phagocytophilum may have an additional porin. In the obligate intracellular pathogen Chlamydia, two porins, namely, MOMP (10, 39) and PorB (12, 13), have been identified. Further analysis of the A. phagocytophilum porin will help to delineate the physiology of the obligatory intracellular pathogen and illuminate a vaccine candidate to prevent HGA.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate Hiroshi Nikaido and Etsuko Sugawara at University of California, Berkeley, for hands-on instructions on the liposome swelling assay and for critical readings of the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01AI30010 and R01AI47407.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 December 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barbet, A. F., P. F. Meeus, M. Belanger, M. V. Bowie, J. Yi, A. M. Lundgren, A. R. Alleman, S. J. Wong, F. K. Chu, U. G. Munderloh, and S. D. Jauron. 2003. Expression of multiple outer membrane protein sequence variants from a single genomic locus of Anaplasma phagocytophilum. Infect. Immun. 71:1706-1718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen, S. M., J. S. Dumler, J. S. Bakken, and D. H. Walker. 1994. Identification of a granulocytotropic Ehrlichia species as the etiologic agent of human disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:589-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dumler, J. S., K. S. Choi, J. C. Garcia-Garcia, N. S. Barat, D. G. Scorpio, J. W. Garyu, D. J. Grab, and J. S. Bakken. 2005. Human granulocytic anaplasmosis and Anaplasma phagocytophilum. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11:1828-1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunning Hotopp, J. C., M. Lin, R. Madupu, J. Crabtree, S. V. Angiuoli, J. Eisen, R. Seshadri, Q. Ren, M. Wu, T. R. Utterback, S. Smith, M. Lewis, H. Khouri, C. Zhang, H. Niu, Q. Lin, N. Ohashi, N. Zhi, W. Nelson, L. M. Brinkac, R. J. Dodson, M. J. Rosovitz, J. Sundaram, S. C. Daugherty, T. Davidsen, A. S. Durkin, M. Gwinn, D. H. Haft, J. D. Selengut, S. A. Sullivan, N. Zafar, L. Zhou, F. Benahmed, H. Forberger, R. Halpin, S. Mulligan, J. Robinson, O. White, Y. Rikihisa, and H. Tettelin. 2006. Comparative genomics of emerging human ehrlichiosis agents. PLoS Genet. 2:e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Felek, S., S. Telford III, R. C. Falco, and Y. Rikihisa. 2004. Sequence analysis of p44 homologs expressed by Anaplasma phagocytophilum in infected ticks feeding on naive hosts and in mice infected by tick attachment. Infect. Immun. 72:659-666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodman, J. L., C. Nelson, B. Vitale, J. E. Madigan, J. S. Dumler, T. J. Kurtti, and U. G. Munderloh. 1996. Direct cultivation of the causative agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 334:209-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Humphries, H. E., J. N. Williams, R. Blackstone, K. A. Jolley, H. M. Yuen, M. Christodoulides, and J. E. Heckels. 2006. Multivalent liposome-based vaccines containing different serosubtypes of PorA protein induce cross-protective bactericidal immune responses against Neisseria meningitidis. Vaccine 24:36-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeanteur, D., J. H. Lakey, and F. Pattus. 1991. The bacterial porin superfamily: sequence alignment and structure prediction. Mol. Microbiol. 5:2153-2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeanteur, D., J. H. Lakey, and F. Pattus. 1994. The porin superfamily: diversity and common features, p. 363-380. In J.-M. Ghuysen and R. Hakenbeck (ed.), New comprehensive biochemistry, vol. 27. Bacterial cell wall. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones, H. M., A. Kubo, and R. S. Stephens. 2000. Design, expression and functional characterization of a synthetic gene encoding the Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein. Gene 258:173-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalman, S., W. Mitchell, R. Marathe, C. Lammel, J. Fan, R. W. Hyman, L. Olinger, J. Grimwood, R. W. Davis, and R. S. Stephens. 1999. Comparative genomes of Chlamydia pneumoniae and C. trachomatis. Nat. Genet. 21:385-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kubo, A., and R. S. Stephens. 2000. Characterization and functional analysis of PorB, a Chlamydia porin and neutralizing target. Mol. Microbiol. 38:772-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kubo, A., and R. S. Stephens. 2001. Substrate-specific diffusion of select dicarboxylates through Chlamydia trachomatis PorB. Microbiology 147:3135-3140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin, Q., and Y. Rikihisa. 2005. Establishment of cloned Anaplasma phagocytophilum and analysis of p44 gene conversion within an infected horse and infected SCID mice. Infect. Immun. 73:5106-5114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin, Q., Y. Rikihisa, R. F. Massung, Z. Woldehiwet, and R. C. Falco. 2004. Polymorphism and transcription at the p44-1/p44-18 genomic locus in Anaplasma phagocytophilum strains from diverse geographic regions. Infect. Immun. 72:5574-5581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin, Q., Y. Rikihisa, N. Ohashi, and N. Zhi. 2003. Mechanisms of variable p44 expression by Anaplasma phagocytophilum. Infect. Immun. 71:5650-5661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin, Q., C. Zhang, and Y. Rikihisa. 2006. Analysis of involvement of the RecF pathway in p44 recombination in Anaplasma phagocytophilum and in Escherichia coli by using a plasmid carrying the p44 expression and p44 donor loci. Infect. Immun. 74:2052-2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin, Q., N. Zhi, N. Ohashi, H. W. Horowitz, M. E. Aguero-Rosenfeld, J. Raffalli, G. P. Wormser, and Y. Rikihisa. 2002. Analysis of sequences and loci of p44 homologs expressed by Anaplasma phagocytophila in acutely infected patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2981-2988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Messick, J. B., and Y. Rikihisa. 1994. Inhibition of binding, entry, or intracellular proliferation of Ehrlichia risticii in P388D1 cells by anti-E. risticii serum, immunoglobulin G, or Fab fragment. Infect. Immun. 62:3156-3161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nikaido, H. 2003. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67:593-656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nikaido, H. 1994. Porins and specific diffusion channels in bacterial outer membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 269:3905-3908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nikaido, H., and T. Nakae. 1979. The outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 20:163-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nikaido, H., K. Nikaido, and S. Harayama. 1991. Identification and characterization of porins in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Biol. Chem. 266:770-779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nikaido, H., and E. Y. Rosenberg. 1983. Porin channels in Escherichia coli: studies with liposomes reconstituted from purified proteins. J. Bacteriol. 153:241-252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohashi, N., N. Zhi, Y. Zhang, and Y. Rikihisa. 1998. Immunodominant major outer membrane proteins of Ehrlichia chaffeensis are encoded by a polymorphic multigene family. Infect. Immun. 66:132-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pal, S., E. M. Peterson, and L. M. de la Maza. 2005. Vaccination with the Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein can elicit an immune response as protective as that resulting from inoculation with live bacteria. Infect. Immun. 73:8153-8160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park, J., K. J. Kim, D. J. Grab, and J. S. Dumler. 2003. Anaplasma phagocytophilum major surface protein-2 (Msp2) forms multimeric complexes in the bacterial membrane. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 227:243-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rikihisa, Y., Y. Zhang, and J. Park. 1995. Role of Ca2+ and calmodulin in ehrlichial infection in macrophages. Infect. Immun. 63:2310-2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rikihisa, Y., N. Zhi, G. P. Wormser, B. Wen, H. W. Horowitz, and K. E. Hechemy. 1997. Ultrastructural and antigenic characterization of a granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent directly isolated and stably cultivated from a patient in New York State. J. Infect. Dis. 175:210-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharff, A., C. Fanutti, J. Shi, C. Calladine, and B. Luisi. 2001. The role of the TolC family in protein transport and multidrug efflux. From stereochemical certainty to mechanistic hypothesis. Eur. J. Biochem. 268:5011-5026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stephens, R. S., S. Kalman, C. Lammel, J. Fan, R. Marathe, L. Aravind, W. Mitchell, L. Olinger, R. L. Tatusov, Q. Zhao, E. V. Koonin, and R. W. Davis. 1998. Genome sequence of an obligate intracellular pathogen of humans: Chlamydia trachomatis. Science 282:754-759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sugawara, E., E. M. Nestorovich, S. M. Bezrukov, and H. Nikaido. 2006. Pseudomonas aeruginosa porin OprF exists in two different conformations. J. Biol. Chem. 281:16220-16229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sugawara, E., and H. Nikaido. 1992. Pore-forming activity of OmpA protein of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 267:2507-2511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sugawara, E., M. Steiert, S. Rouhani, and H. Nikaido. 1996. Secondary structure of the outer membrane proteins OmpA of Escherichia coli and OprF of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 178:6067-6069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang, X., T. Kikuchi, and Y. Rikihisa. 2006. Two monoclonal antibodies with defined epitopes of P44 major surface proteins neutralize Anaplasma phagocytophilum by distinct mechanisms. Infect. Immun. 74:1873-1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang, X., Y. Rikihisa, T. H. Lai, Y. Kumagai, N. Zhi, and S. M. Reed. 2004. Rapid sequential changeover of expressed p44 genes during the acute phase of Anaplasma phagocytophilum infection in horses. Infect. Immun. 72:6852-6859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weiss, E., J. C. Williams, G. A. Dasch, and Y. H. Kang. 1989. Energy metabolism of monocytic Ehrlichia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:1674-1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Worgall, S., A. Krause, M. Rivara, K. K. Hee, E. V. Vintayen, N. R. Hackett, P. W. Roelvink, J. T. Bruder, T. J. Wickham, I. Kovesdi, and R. G. Crystal. 2005. Protection against P. aeruginosa with an adenovirus vector containing an OprF epitope in the capsid. J. Clin. Investig. 115:1281-1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wyllie, S., R. H. Ashley, D. Longbottom, and A. J. Herring. 1998. The major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia psittaci functions as a porin-like ion channel. Infect. Immun. 66:5202-5207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhi, N., N. Ohashi, and Y. Rikihisa. 1999. Multiple p44 genes encoding major outer membrane proteins are expressed in the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent. J. Biol. Chem. 274:17828-17836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhi, N., N. Ohashi, Y. Rikihisa, H. W. Horowitz, G. P. Wormser, and K. Hechemy. 1998. Cloning and expression of the 44-kilodalton major outer membrane protein gene of the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent and application of the recombinant protein to serodiagnosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1666-1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhi, N., N. Ohashi, T. Tajima, J. Mott, R. W. Stich, D. Grover, S. R. Telford III, Q. Lin, and Y. Rikihisa. 2002. Transcript heterogeneity of the p44 multigene family in a human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent transmitted by ticks. Infect. Immun. 70:1175-1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]