Abstract

Uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) strains are responsible for the majority of uncomplicated urinary tract infections, which can present clinically as cystitis or pyelonephritis. UPEC strain CFT073, isolated from the blood of a patient with acute pyelonephritis, was most cytotoxic and most virulent in mice among our strain collection. Based on the genome sequence of CFT073, microarrays were utilized in comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) analysis of a panel of uropathogenic and fecal/commensal E. coli isolates. Genomic DNA from seven UPEC (three pyelonephritis and four cystitis) isolates and three fecal/commensal strains, including K-12 MG1655, was hybridized to the CFT073 microarray. The CFT073 genome contains 5,379 genes; CGH analysis revealed that 2,820 (52.4%) of these genes were common to all 11 E. coli strains, yet only 173 UPEC-specific genes were found by CGH to be present in all UPEC strains but in none of the fecal/commensal strains. When the sequences of three additional sequenced UPEC strains (UTI89, 536, and F11) and a commensal strain (HS) were added to the analysis, 131 genes present in all UPEC strains but in no fecal/commensal strains were identified. Seven previously unrecognized genomic islands (>30 kb) were delineated by CGH in addition to the three known pathogenicity islands. These genomic islands comprise 672 kb of the 5,231-kb (12.8%) genome, demonstrating the importance of horizontal transfer for UPEC and the mosaic structure of the genome. UPEC strains contain a greater number of iron acquisition systems than do fecal/commensal strains, which is reflective of the adaptation to the iron-limiting urinary tract environment. Each strain displayed distinct differences in the number and type of known virulence factors. The large number of hypothetical genes in the CFT073 genome, especially those shown to be UPEC specific, strongly suggests that many urovirulence factors remain uncharacterized.

Escherichia coli strains capable of causing disease outside the gastrointestinal tract belong to a diverse group of isolates referred to as extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC) (50, 84). ExPEC strains are responsible for a variety of diseases, including urinary tract infections (UTIs), newborn meningitis, septicemia, nosocomial pneumonia, intra-abdominal infections, osteomyelitis and wound infections (22, 27, 49, 84). Uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC), a prominent member of the ExPEC family, is responsible for up to 90% of uncomplicated UTIs in otherwise healthy individuals (108). An infection occurs primarily by the ascending route following the contamination of the periurethral area, presumably via a fecal reservoir. Bacteria ascend the urethra and colonize the bladder, resulting in cystitis, and in severe cases, infection may spread up the ureters to the kidneys, causing pyelonephritis (15). A serious and potentially life-threatening complication of pyelonephritis occurs when bacteria invade the bloodstream and produce a systemic infection. Due to anatomical differences, UTIs are significantly more common in women than in men, with approximately half of all women experiencing a UTI by their late twenties (109). Foxman and colleagues (28) reported that 10.8% of women aged 18 years and older had experienced at least one physician-diagnosed UTI within the previous 12 months, with the majority of these women having experienced a total of two or more UTIs during their lifetime. Clinically, a UTI is defined as bacteriuria with ≥105 CFU/ml midstream urine (93, 105). However, Stamm and colleagues studied women with presumptive lower numbers of UTIs and discovered that up to 50% of symptomatic women with coliforms in their urine were not detected by using this criterion (98), suggesting that UTI is even more common than reported.

Although UPEC strains exist within the intestinal tract of humans, they are distinct from most diarrheagenic or commensal E. coli strains in that UPEC isolates possess specific factors that permit their successful transition from the intestinal tract to the urinary tract. A range of putative and established virulence genes have been identified in UPEC that enable these isolates to overcome host defenses and establish infection in this unique niche. These factors include fimbrial adhesins (type 1, P, and S/F1C), toxins (cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 [cnf1], hemolysin, and secreted autotransporter toxin), host defense avoidance mechanisms (capsule or O-specific antigen), and multiple iron acquisition systems (aerobactin, enterobactin, enterobactin-like, including iroN, and yersiniabactin) (47, 84). Additionally, sequencing of the prototypic pyelonephritogenic UPEC isolate E. coli CFT073 (104) has revealed that many of the coding sequences (CDS) could be assigned no function and are labeled as hypothetical or have been assigned putative functions. This abundance of unknown genes strongly suggests the existence of novel virulence determinants that may play important role in UTI pathogenesis. Despite the identification of multiple virulence-associated genes in UPEC, no single profile of urovirulence has been determined, with half of all UPEC isolates containing none or only one of the urovirulence determinants identified to date (60).

The genome size of naturally occurring E. coli isolates can differ by up to 1 Mb, ranging from approximately 4.5 to 5.5 Mb (5). This variability is reflected in the commensal E. coli K-12 isolate MG1655 (4.64 Mb) (9), the enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) strains O157:H7 Sakai (5.50 Mb) (38) and O157:H7 EDL933 (5.53 Mb) (77), the enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC) strain O42 (5.36 Mb) (www.sanger.ac.uk), and UPEC isolates CFT073 (5.23 Mb) (104), J96 (5.06 Mb) (83), 536 (4.94 Mb) (16), and UTI89 (5.07 Mb) (20). The observed differences in genome size between different E. coli strains are primarily due to the insertion or deletion of a few large chromosomal regions, with overall gene order maintained between different strains (83).

The acquisition of DNA by horizontal gene transfer (HGT) is an effective mechanism of generating diversity between bacterial species. The acquisition of plasmids and bacteriophages also plays an important role in generating genomic diversity (24). HGT results in an unusually high degree of similarity in DNA composition between the exchanged region of the donor and recipient genomes (69). If the newly acquired DNA confers an advantage to the organism, then it is retained and may be stably integrated into the genome through the process of natural selection (56). HGT is believed to be essential for adaptive evolution of bacterial species (87). The amount of genetic material which has been acquired through HGT is unexpectedly high in a number of bacterial pathogens (54, 69). For example, 18% of the genes in the E. coli K-12 MG1655 chromosome appear to have been acquired from other bacterial species through HGT (57).

Overall, the G+C content of bacterial species can differ significantly; however, within a single species, base composition and codon usage are generally conserved. Regions of genome plasticity (plasticity zones) can be identified as areas with an atypical G+C content relative to the rest of the genome, suggesting that such DNA segments originated from a different organism (57, 69). Large regions of genomic DNA, ranging from 5 to 100 kb in length, are frequently exchanged between bacterial isolates. These regions of DNA are referred to as “genomic islands” (GIs) or, if these DNA segments contain virulence factors or virulence-associated genes, the term “pathogenicity island” (PAI) is commonly used (33). PAIs are large (>30 kb), unstable regions of chromosomal DNA that contain bacterial virulence genes (33, 34). The G+C content of PAIs frequently differs from the rest of the genome, indicating possible acquisition from a related bacterial species by HGT, and PAIs are frequently associated with tRNA genes, which have been suggested to act as integration sites for foreign DNA. Insertion sequences or direct repeats often flank these pathogenicity-associated GIs, and mobility genes (often cryptic), including insertion sequence elements, transposases, origins of plasmid replication, and integrases are often found within PAIs. Additionally, PAIs are commonly found in pathogenic strains but are absent or rarely found in nonpathogenic strains (33, 34). PAIs were first described for the UPEC strain 536 (11) and have since been identified in three other UPEC strains, the pyelonephritis isolates J96 (102) and CFT073 (32, 75, 81) and the cystitis isolate UTI89 (20).

Identification of the somatic (O) and flagellar (H) antigens of E. coli by serotyping is the traditional diagnostic classification system of pathogenic E. coli. Various groups of O and H antigens have been associated with specific E. coli pathotypes, with more than 176 O serogroups described to date (6, 71, 89). Ten of these O serogroups (O1, O2, O4, O6, O7, O8, O16, O18, O25, and O75) are preferentially associated with UPEC strains (48, 71). The majority of ExPEC isolates belong to phylogenetic group B2 and, to a lesser extent, group D (7, 13, 51, 78), whereas most commensal strains, including K-12 MG1655, belong to group A (41). Well-studied UPEC isolates 536 and J96 both belong to phylogenetic group B2 and have the serotypes O6:H31 and O4:H5, respectively.

The use of comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) analysis capitalizes upon the rapidly expanding fields of microbial genomics, bioinformatics, and microarray technology and is a powerful tool for comparing the gene content of multiple bacterial genomes. For this study, the genomes of three pyelonephritis strains, four cystitis strains, and three fecal/commensal E. coli isolates (including E. coli K-12 MG1655) were hybridized against the E. coli CFT073 microarray. A distinction could be made between genes with “core functions” (present in all 12 E. coli strains) and genes that were potentially involved in the pathogenesis of UTIs. Using this technique, we were able to clearly delineate 13 genomic or phage islands in strain CFT073 and identify UPEC-specific genes. Additional bioinformatic screens confirmed our CGH findings and allowed the inclusion of the recently sequenced UPEC strains UTI89, 536, and F11 in comparative analyses. Using these methods, we were able to conclusively identify 131 genes that were exclusively found in UPEC relative to commensal and fecal isolates. Half of these genes are annotated as hypothetical or have little functional characterization, thus identifying a pool of potential urovirulence factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

E. coli CFT073 was isolated from the blood of a patient admitted to the University of Maryland Medical System for the treatment of acute pyelonephritis. This strain is highly virulent in the CBA mouse model of ascending UTI (65), is cytotoxic for cultured human renal proximal tubular epithelial cells (64), and has been sequenced (104). Three collections of E. coli strains isolated from humans with appropriate clinical syndromes were used in this study. Pyelonephritis strains (CFT204, CFT269, and CFT325) were isolated from the urine or blood of patients who were admitted to the University of Maryland Medical System with acute pyelonephritis (bacteriuria of ≥105 CFU/ml, pyuria, fever, and no other source of infection) (65). Cystitis strains (F3, F11, F24, and F54) were isolated from the urine of women under the age of 30 years with first episodes of cystitis and bacteriuria of ≥105 CFU/ml (99). Fecal/ commensal E. coli isolates (EFC4 and EFC9) were collected from healthy women aged 20 to 50 years with no history of diarrhea, antibiotic usage, or symptomatic UTI within the past month (65) and are avirulent in the murine model of UTI (64). Additionally, the laboratory-adapted fecal/commensal E. coli isolate K-12 MG1655 was used as a negative control for CGH microarray experiments as the genome sequence has been determined (9).

Serotyping and virulence gene identification.

All serotyping and virulence gene identification was conducted by the Gastroenteric Disease Center at Pennsylvania State University. Using PCR, strains were tested for the presence of a range of virulence genes associated with UPEC and diarrheagenic E. coli strains: heat labile toxin (LT); heat stable toxin a and b (STa/STb), Shiga toxin types 1 and 2 (STX1/STX2), cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 and 2 (CNF1/2), intimin-gamma (EAE), bundle-forming pili (BFP), O antigen type 157 (O157), P-fimbrial adhesin genes (papG alleles I and III), S-fimbrial adhesin (SFA), and F1C-fimbrial adhesin (focG).

Genome alignments of E. coli strains CFT073 and K-12 MG1655.

The full genomes of E. coli CFT073 (104) (GenBank accession no. AE014075) and K-12 MG1655 (9) (GenBank accession no. U00096) were sequentially aligned in ≤20-kb segments using coliBASE software (http://colibase.bham.ac.uk) (19). Using a gene-by-gene comparison of these two genomes, it was possible to identify CFT073 genes that are present in K-12 but may not have been annotated as present. Genes were classified as present if (i) the same gene was annotated in both strains, (ii) an orthologous gene was identified in K-12, or (iii) a gene with a high level of nucleotide identity to a CFT073 gene was found in K-12. Genes that were severely truncated in either strain were not considered present. The findings from this gene-by-gene comparison between the E. coli CFT073 and K-12 genomes were used to validate the microarray data.

CGH microarray analysis.

The E. coli CFT073-specific DNA microarray (NimbleGen Systems, Inc., Madison, WI) includes 5,379 annotated CDS from the CFT073 genome sequence (104). Each of the CDS is represented on the glass slide by a minimum of 17 unique probe pairs of 24-mer in situ-synthesized oligonucleotides. Probes are evenly spaced throughout the CDS, and intergenic sequences are not included on the array. Each pair consists of a sequence perfectly matched to the CDS, and another adjacent sequence harbors two mismatched bases for the determination of background and cross-hybridization, equating to 190,000 probes per array.

Total genomic DNA from log-phase UPEC and fecal/commensal E. coli isolates was isolated using Genomic-Tip 500/G columns (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's protocol, and the DNA concentration was adjusted to approximately 1 μg/μl. Genomic DNA was labeled with a randomly primed reaction (92). DNA (1 μg) was mixed with 1 optical density of 5′ Cy3-labeled random nonamer (TriLink Biotechnologies) in 62.5 mM Tris-HCl, 6.25 mM MgCl2, and 0.0875% β-mercaptoethanol; denatured at 98°C for 5 min; chilled on ice; and incubated with 100 U Klenow fragment (NEB) and deoxynucleoside triphosphate mix (6 mM each in Tris-EDTA) for 2 h at 37°C. Reactions were terminated with 0.5 M EDTA (pH 8.0), precipitated with isopropanol, and resuspended in water. A 50-fold amplification was typically achieved. Labeled genomic DNA was hybridized to arrays in 1× NimbleGen hybridization buffer for 16 h at 45°C using a Hybriwheel hybridization apparatus (NimbleGen) in a rotisserie oven. The next morning, arrays were washed with nonstringent wash buffer (6× SSPE [1× SSPE is 0.18 M NaCl, 10 mM NaH2PO4, and 1 mM EDTA {pH 7.7}], 0.01% [vol/vol] Tween 20) for 2 min and then twice in stringent wash buffer (100 mM morpholineethanesulfonic acid [MES], 0.1 M NaCl, 0.01% [vol/vol] Tween 20) for 5 min, all at 47.5°C. Finally, arrays were washed again in nonstringent wash buffer (1 min) and rinsed twice for 30 s in 0.05× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate). Arrays were spun dry in a custom centrifuge and stored until scanned. Microarrays were scanned at a 5-μm resolution using the Genepix 4000b scanner (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA), and pixel intensities were extracted using NimbleScan image extraction and analysis software.

Data from all microarray experiments were normalized using the technique described by Irizarry and colleagues (44) and log2 transformed prior to analysis. The normalized data took into account the signal intensity from every probe (perfect match and mismatch oligonucleotides) for each CDS in the genome and permitted comparative analyses to be made between individual hybridization experiments. Normalized data were analyzed for the presence/absence of annotated CDS relative to the E. coli CFT073 reference strain. CDS with normalized array values of less than 7.9 were considered to be absent from the test strain relative to the reference strain, E. coli CFT073. The cutoff value differs between individual microarray experiments, as the normalization of data from multiple experiments is dependent upon the set of input data. To validate the normalized, log2-transformed microarray data, a gene-by-gene comparison between the E. coli CFT073 and K-12 genomes was conducted using coliBASE software (19).

Bioinformatic screen of the E. coli CFT073 genome.

Each of the CDS for the E. coli CFT073 genome was compared against the CDS for the publicly available UPEC genomes (UTI89, 536, and F11) as well as all other commensal and diarrheagenic E. coli strains listed in Table 1 by using BLAST score ratio (BSR) analysis (80). The comparisons in this study were performed using the nucleotide sequences for each coding region instead of the peptide coding regions to allow direct comparison between the microarray studies and the BSR analysis (peptide comparisons were also performed, and the data for the peptides were similar to data for the nucleotide comparisons). For each of the predicted CDS in E. coli CFT073, a BLASTN raw score was obtained for the alignment of the CDS against itself (REF_SCORE) and the most similar CDS (QUE_SCORE) in each of the genomes listed in Table 1. These scores were then normalized by dividing the QUE_SCORE obtained for each query genome CDS by the REF_SCORE. CDS with a normalized ratio of <0.4 were considered to be nonhomologous and scored as “absent” in this data set. A normalized BSR of 0.4 is generally similar to two CDS being ∼30% identical over ∼30% of the CDS. A normalized BSR of >0.8 indicates that the CDS are highly conserved and were scored as “present” in the study. This value represents more than ∼85 to 90% nucleotide identity over 90% of the reference sequence, indicative of a highly conserved sequence. CDS labeled as divergent have BSR values between these two extremes and represent genes that have diverged but still show significant levels of similarity such that they can be identified as homologs.

TABLE 1.

Sequenced E. coli strains used for BSR analysis against CFT073

| Strain | Disease | GenBank accession number or location |

|---|---|---|

| CFT073 | UPEC | AE014075.1 |

| UTI89 | UPEC | CP000243.1 |

| 536 | UPEC | CP000247.1 |

| F11 | UPEC | AAJU00000000 |

| K-12 MG1655 | Lab-adapted human commensal E. coli | U00096.2 |

| HS | Human commensal E. coli | AAJY00000000 |

| EDL933 | EHEC | AE005174.2 |

| Sakai | EHEC | BA000007.2 |

| 101-1 | EAEC | AAMK00000000 |

| O42 | EAEC | Sanger Center |

| E24377A | ETEC | AAJZ00000000 |

| B7A | ETEC | AAJT00000000 |

| E22 | REPEC | AAJV00000000 |

| E110019 | EPEC | AAJW00000000 |

| B171 | EPEC | AAJX00000000 |

RESULTS

Selection of strains for comparison to E. coli CFT073.

Seven uropathogenic strains of E. coli (three pyelonephritis strains and four cystitis strains) were selected for detailed genomic comparisons to E. coli CFT073, a pyelonephritis strain used widely for the study of UTI (64, 95, 104). Serotypes and virulence gene profiles were determined for these eight UPEC strains and for two fecal/commensal E. coli strains (Table 2). UPEC strains were represented by five O serogroups (O1, O6, O18, O25, and O75) that are among the six most common UPEC O serogroups (48, 71). Direct genomic sequence comparison was also used for three additional UPEC strains (UTI89, 536, and F11) and the well-characterized commensal strain HS.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of E. coli strains used in this study

| Type of strain | Strainb | Source of isolate | Reaction resulta

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serotypec | cnf1 | papG allele I* | papG allele III* | SFA | focG | Hemolysin | |||

| Pyelonephritis | CFT073 | Blood | O6:H1 | − | + | − | + | + | + |

| Pyelonephritis | CFT204 | Urine | O6:H1 | − | + | − | − | − | + |

| Pyelonephritis | CFT269 | Urine | O1:H7 | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Pyelonephritis | CFT325 | Blood | O75:H56 | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Cystitis | F3 | Urine | O18:H7 | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| Cystitis | F11 | Urine | O6:H31 | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| Cystitis | F24 | Urine | O18:H7 | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| Cystitis | F54 | Urine | O25:H4 | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Feces | EFC4 | Feces | OM:H32 | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Feces | EFC9 | Feces | OM:H21 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

“+,” positive reaction; −, negative reaction. *, strains were tested for only the presence of papG alleles I and III (allele II test not available).

All strains were negative for heat labile toxin, heat stable toxin a/b, Shiga toxin types 1/2; cytotoxic necrotizing factor 2; intimin-gamma and bundle-forming pili. All strains were negative for O antigen type 157 except strains CFT269, F24, and F54 (not tested).

“M” in the serotype indicates multiple positives.

Validation of microarray data and comparison of E. coli CFT073 with E. coli K-12 MG1655.

Genomic DNA from the seven UPEC strains and three fecal or commensal strains was hybridized to the CFT073 microarray for the purpose of CGH. To validate this technique, we compared the signal intensities from the microarrays to an evaluation of whether genes of K-12 strain MG1655 are present or absent with respect to CFT073 by direct sequence comparison. Genome alignments between CFT073 and MG1655 revealed 4,025 CDS in common, as either orthologous CDS or coding regions with substantial identity at the nucleotide level. A threshold value for the normalized microarray data was established by comparing array data signal intensity to genome alignments. We determined the normalized microarray value that most closely represented the presence or absence of genes in K-12 (see Materials and Methods). Array data were normalized and log2 transformed prior to analysis. Using the established cutoff value, microarray analysis identified 3,878 genes common to both K-12 and CFT073.

Of the 4,025 CFT073 CDS identified in K-12 by genome alignments, 531 of these CDS are not annotated in K-12. Microarray data confirmed the presence of 461 of these genes (87%) in the K-12 genome sequence. Many of the genes that are present in K-12 but appeared to be absent by microarray were either truncated genes or contained divergent nucleotide sequences that would have affected DNA hybridization to the CGH arrays. The difference in the number of genes shared between K-12 and CFT073 by genome alignment versus array data was 147 genes, indicating that only 2.7% of the genes in the array could be misclassified by CGH as absent when they were present (i.e., false negative results). Thus, 97.3% of genes were classified correctly, validating the microarray for determination of gene content among strains. In silico BSR analysis of the K-12 and CFT073 CDS revealed a similar number (3,933) of the CDS classified as either present (3,381) or divergent (552) using a conservative threshold.

Comparative genomic hybridization of E. coli CFT073 with uropathogenic and fecal or commensal E. coli strains.

The number of genes that each E. coli strain had in common with CFT073, based upon microarray data, is shown in Table 3. Pyelonephritis and cystitis isolates (UPEC strains) contained similar numbers of CFT073 genes, whereas the fecal or commensal strains had ∼100 fewer genes than the UPEC isolates; the laboratory-adapted fecal or commensal strain K-12 had approximately 300 fewer genes than the UPEC isolates. Although the UPEC isolates tended to contain more CFT073 genes than did the fecal or commensal strains, this difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). The number of genes that were common to all 10 E. coli strains was 2,820, representing 52.4% of the E. coli CFT073 genome.

TABLE 3.

Number of CFT073 genes present in UPEC and fecal/commensal E. coli strains based on CGH microarrays

| Strain type | Strain | No. of CFT073 genes in common | Avg no. of CFT073 genes in common ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pyelonephritis | CFT204 | 4,178 | 4,198 ± 37 |

| CFT269 | 4,241 | ||

| CFT325 | 4,176 | ||

| Cystitis | F3 | 4,245 | 4,189 ± 38 |

| F11 | 4,162 | ||

| F24 | 4,168 | ||

| F54 | 4,181 | ||

| Fecal/commensal | EFC4 | 4,054 | 4,011 ± 118 |

| EFC9 | 4,101 | ||

| K-12 | 3,878 |

Genomic islands identified in E. coli CFT7073.

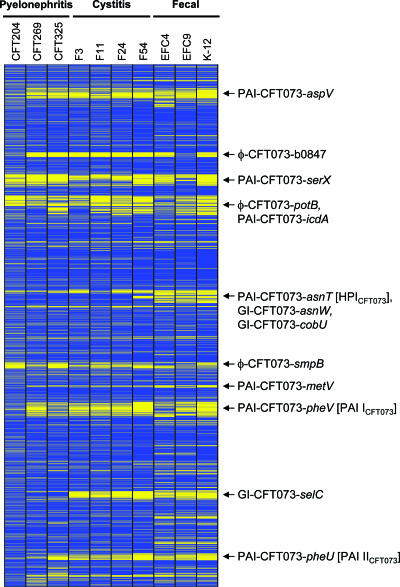

The presence or absence of CFT073 genes in E. coli strains, grouped by clinical source, is graphically displayed in Fig. 1. The 5,379 CDS of CFT073 are classified as present or absent in the three pyelonephritis, four cystitis, and three fecal or commensal E. coli strains. The CGH microarray analysis of seven UPEC and three fecal or commensal strains clearly revealed the presence of 10 genomic islands of >30 kb in E. coli strain CFT073 (Table 4). Strain CFT204 has more genomic islands in common with CFT073 than do the other UPEC isolates, suggesting a closer evolutionary relationship between these two strains (Fig. 1). Seven islands are newly delineated, and three previously described islands (32, 70, 81) were confirmed. These large genomic islands comprise 672 of the 5,231 kb (12.8%) of the CFT073 genome. Three islands consisting of predominantly phage DNA are also shown.

FIG. 1.

Graphical display of CGH microarray data. Each row corresponds to the annotated CDS of E. coli CFT073, from thrL (c0001) at the top, to lasT (c5379) at the bottom. The columns represent the 10 E. coli strains hybridized against the CFT073 microarray, grouped by clinical presentation (CFT204, CFT269, and CFT325 strains, pyelonephritis; F3, F11, F24, and F54 strains, cystitis; EFC4 and EFC9, fecal/commensal strains; and K-12, E. coli K-12 MG1655). Based on the microarray data, blue indicates CDS identified as present and yellow indicates CDS identified as absent. The 10 genomic islands and three phage regions identified in Table 4 are shown on the right.

TABLE 4.

Genomic islands and phage regions of >30 kb identified in E. coli CFT073 using CGH

| Island no. | CDS in islanda | Associated tRNA | Size (kb) | % GCb | Virulence gene(s)c within island | No. hypo. CDSd | Island namee |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | c0253-c0368 | Asp tRNA-aspV | 100 | 47 | cdiA (c0345) and picU (c0350) | 99 | PAI-CFT073-aspV (PAI IIICFT073) |

| 2 | intT-ogrK | 33 | 50 | Prophage DNA | 34 | φ-CFT073-b0847 | |

| 3 | c1165-c1293 | Ser tRNA-serX | 113 | 49 | mchBCDEF (c1227 and c1229-c1232), sfa/F1C operon (c1237-c1247), iroNEDCB (c1250-c1254), and antigen 43 precursor (c1273) | 91 | PAI-CFT073-serX |

| 4 | c1400-c1474 | 44 | 51 | Prophage DNA | 65 | φ-CFT073-potB | |

| 5 | c1518-c1601 | 54 | 50 | Prophage DNA and sitDCBA (c1597-c1600) | 61 | PAI-CFT073-icdA | |

| 6 | c2418-c2437 | Asn tRNA-asnT | 32 | 57 | Yersiniabactin receptor (c2436) | 18 | PAI-CFT073-asnT (HPICFT073 [70]) |

| 7 | c2449-c2475 | Asn tRNA-asnW | 54 | 53 | 23 | GI-CFT073-asnW | |

| 8 | c2482-c2528 | 44 | 50 | 34 | GI-CFT073-cobU | ||

| 9 | c3143-c3206 | 48 | 49 | Prophage DNA | 52 | φ-CFT073-smpB | |

| 10 | c3385-c3410 | Met tRNA-metV | 32 | 53 | Secreted protein Hcp (c3391) and ClpB protein (c3392) | 19 | PAI-CFT073-metV |

| 11 | c3556-kpsM | Phe tRNA-pheV | 123 | 47 | hlyA (c3570), pap operon (c3582-c3593), iha (c3610), sat (c3619), iutA (c3623), iucDCBA (c3624-c3628), antigen 43 precursor (c3655), and kpsTM (c3697-c3698) | 86 | PAI-CFT073-pheV (PAI ICFT073 [32]) |

| 12 | intC-c4581 | Sec tRNA-selC | 68 | 47 | 76 | GI-CFT073-selC | |

| 13 | c5143-c5216 | Phe tRNA-pheU | 52 | 48 | pap_2 operon (c5179-c5189) | 53 | PAI-CFT073-pheU (PAI IICFT073 [81]) |

Boundaries of the genomic islands are recoded to the nearest CDS in CFT073, although the actual insertion site may be intergenic.

%GC is the G+C content of the genomic island, determined by using the GeeCee program (http://bioweb.pasteur.fr/seqanal/interfaces/geecee.html) and the coliBASE fragment viewer.

Established or putative virulence factors of UPEC that are found in CFT073.

CFT073 genes annotated in coliBASE (http://colibase.bham.ac.uk/) with hypothetical (hypo.) or putative functions.

Genomic islands have been named as PAI (containing known virulence genes), GI (containing genes with unknown role in virulence), or φ (containing predominantly phage DNA), followed by the strain (CFT073) and the gene adjacent to the insertion site (CFT073 tRNA gene or the corresponding gene in E. coli K-12).

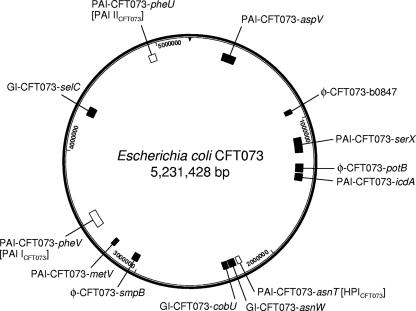

A new nomenclature for these genomic islands has been proposed based on this analysis (Table 4) and the recommendations of Moritz and Welch (66). Genomic islands containing established or putative virulence genes are labeled PAI-CFT073-gene name, where “gene name” is the approximate site of insertion of the island and represents either a tRNA gene in CFT073 or the corresponding gene in the K-12 genome. Genomic islands containing genes of unknown function are labeled GI-CFT073-gene name, and regions of predominantly bacteriophage DNA are noted as φ-CFT073-gene name, as described above. Eight of the 10 genomic islands (80%) were associated with a tRNA locus, and the majority of islands contained a phage integrase, transposase, or insertion sequence at one or both boundaries of the island. The size of the islands ranged from 32 to 123 kb (median size of 54 kb) and 8 of the 10 (80%) islands had G+C contents that differed from that of CFT073 (50.5%) (104). Seven of the genomic islands contained one or more genes with predicted or established roles in virulence (PAI-CFT073-pheV [formerly designated PAI ICFT073], PAI-CFT073-pheU [PAI IICFT073], PAI-CFT073-aspV [PAI IIICFT073], PAI-CFT073-serX, PAI-CFT073-icdA, PAI-CFT073-metV, and PAI-CFT073-asnT [HPICFT073]), while six (φ-CFT073-b0847, φ-CFT073-potB, GI-CFT073-asnW, GI-CFT073-cobU, φ-CFT073-smpB, and GI-CFT073-selC) contained no known virulence genes. However, all of the genomic islands contained a high number of CDS with hypothetical or putative functions (Table 4), and thus, additional virulence factors may exist within these islands. Studies are currently under way in our laboratory to elucidate the function of these genes. Phage DNA sequence is common in E. coli CFT073; indeed, five cryptic prophage genomes have been identified in this strain, although they do not contain sufficient genetic information to produce viable phage (104). Islands φ-CFT073-b0847, φ-CFT073-potB, PAI-CFT073-icdA, and φ-CFT073-smpB are particularly phage-rich regions of sequence. The position of each genomic island relative to the CFT073 genome sequence is shown in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

Ten genomic islands in E. coli CFT073. The 10 genomic islands and three phage regions of E. coli CFT073 (Table 4) are shown relative to the CFT073 genome sequence. The three previously identified PAIs of CFT073 (PAI-CFT073-pheV [PAI ICFT073], PAI-CFT073-pheU [PAI IICFT073], PAI-CFT073-asnT [HPICFT073]) are shown in white boxes, and the 10 novel genomic islands (including three phage islands) identified by CGH analysis are shown in black boxes.

Our in silico analysis suggests that these genomic islands are not limited to E. coli CFT073. Four of the genomic islands were present in other uropathogenic strains (UTI89, 536, and F11), and one of these genomic islands was also present in an EPEC and EAEC strain, suggesting that a similar island may play a role in the pathogenesis of some diarrheagenic E. coli isolates. It must be noted that although portions of the GIs and PAIs have been identified in other strains, a complete island has not been found in any of the examined strains, suggesting that the E. coli is highly fluid in nature and its mosaic structure has been confirmed by these studies.

The presence of these 10 genomic and 3 phage islands in nine other sequenced bacterial strains was examined using coliBASE genome alignments. Eleven of the CFT073 genomic islands are not present in any of the strains available for analysis by coliBASE. φ-CFT073-b0847 and PAI-CFT073-asnT (HPICFT073) are present in other strains to various degrees. φ-CFT073-b0847 is present in E. coli E2348/69 (EPEC), Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi TY2, and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2, although differences were observed at CDS c0933, c0944 to c0946, and c0967 to c0970. CDS c0963 to c0968 of φ-CFT073-b0847 are inverted in E. coli E2348/69 (EPEC) relative to the CFT073 genome. Otherwise, the gene order is conserved between strains in the genomic island regions. PAI-CFT073-asnT (HPICFT073) was also identified in E. coli O42 (EAEC) and Yersinia pestis CO92, although a minor difference was observed at CDS c2425, and CDS c2424 to c2429 were annotated differently in the strains. In Y. pestis CO92, the corresponding region of sequence from c2424 to c2429 in CFT073 is annotated as irp2 and irp1, and the same CDS have been predicted in E. coli O42 (EAEC) by using Glimmer (86). The irp1 and irp2 genes encode iron-repressible yersiniabactin biosynthesis proteins, which, along with fyuA (yersiniabactin receptor), are part of the high-pathogenicity island (HPI) in Yersinia species (91).

UPEC-specific genes.

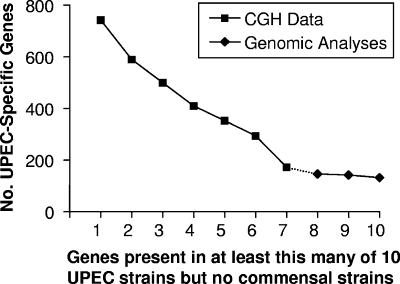

Using CGH analysis, we identified 2,820 genes that were common to all of the UPEC and fecal or commensal strains studied. To estimate the number of these genes that could be considered UPEC specific, we asked how many genes were present in at least a certain number of UPEC strains but not present in any of the fecal or commensal strains, including strain K-12 MG1655. For example, there were 743 such genes present in at least one of the UPEC strains studied by CGH, 590 in at least two strains, and so on (Fig. 3). In our most conservative assessment, there were 173 UPEC-specific CDS that were considered present in all eight UPEC strains (including CFT073) but absent in the fecal or commensal strains. Although UPEC strains are members of the ExPEC family of E. coli, and many genes referred to here as UPEC specific may actually be ExPEC specific, we refrain from making this assumption since no other members of the ExPEC family were tested in this study. In order to answer this question, it would be necessary to examine the presence of these genes in bacterial meningitis E. coli, septicemia isolates, and avian pathogenic E. coli, rather than extrapolate data based upon UPEC isolates alone.

FIG. 3.

Identification of UPEC-specific genes in 10 UPEC strains using CGH and genomic analyses. CGH analysis of seven UPEC strains and three fecal/commensal strains in reference to strain CFT073 identified 173 genes as present in all seven UPEC isolates that were not present in any fecal/commensal strain. These 173 genes were then compared to the sequenced UPEC genomes UTI89, 536, and F11, and the fecal/commensal strain HS. Genes present in the seven UPEC strains by CGH and in one, two, or all three strains UTI89, 536, and F11 but absent from HS were determined; 131 genes were identified as UPEC specific. Of these, 37 genes are within genomic islands of ≥30 kb and 61 genes are annotated as encoding hypothetical proteins.

To determine whether we were approaching a true estimate of the number of UPEC-specific genes or whether the number would continue to fall if we included additional strains in the analysis, we included an analysis of three sequenced UPEC strains and one sequenced commensal strain. If we ask how many of the 173 UPEC-specific genes are also conserved among the three additional sequenced UPEC strains, UTI89, 536, and F11, but not present in sequenced commensal strain HS (58), the answer is 131 (Fig. 3). Thus, 131 genes are present in all 11 UPEC strains, including CFT073, but in none of the fecal or commensal strains examined (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

131 UPEC-specific genes identified using CGH and in silico BSR analysis of ten UPEC and four fecal/commensal strains

| Genea | CFT073 genome annotation | In vivo gene expressionb | Upregulation in vivo (fold change)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| c0287 | Hypothetical protein | 14.46 | 2.42 |

| c0294 | Hypothetical protein | 1.18 | 0.84 |

| c0295 | Hypothetical protein | 0.38 | 3.50 |

| c0296 | Hypothetical protein | 0.64 | 6.57 |

| c0297 | Hypothetical protein | 0.47 | 0.88 |

| c0375 | Hypothetical protein | 0.10 | 0.97 |

| c0638 | Hypothetical protein | 0.22 | 0.24 |

| c0646 | Hypothetical protein | 1.32 | 0.95 |

| ybdO | Hypothetical transcriptional regulator ybdO | 0.52 | 4.57 |

| c0758 | Hypothetical protein | 0.69 | 0.99 |

| c0761 | Putative dihydrodipicolinate synthase | 0.08 | 0.93 |

| c0763 | Putative inner membrane protein | 1.76 | 1.68 |

| c0765 | Putative transcriptional regulator | 0.23 | 0.38 |

| c0807 | Hypothetical protein | 0.15 | 0.40 |

| modD | Putative pyrophosphorylase modD | 0.48 | 0.73 |

| c1650 | Putative iron compound ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein | 0.34 | 0.75 |

| fecD | Iron(III) dicitrate transport system permease protein fecD | 0.08 | 1.09 |

| c1761 | Acriflavine resistance protein A precursor | 0.10 | 1.08 |

| c1762 | Hypothetical protein | 1.12 | 0.69 |

| c1766 | Putative membrane transport protein | 0.35 | 1.72 |

| c1810 | Hypothetical protein | 0.29 | 2.22 |

| c1811 | Hypothetical protein | 0.13 | 1.26 |

| c1812 | Hypothetical protein | 0.08 | 0.62 |

| c1813 | Hypothetical protein | 0.36 | 0.67 |

| c2418 | Prophage P4 integrase | 0.62 | 1.71 |

| c2419 | Putative anthranilate synthase | 0.57 | 1.45 |

| c2420 | Putative cytoplasmic transmembrane protein | 0.12 | 0.41 |

| c2421 | Putative ABC transporter protein | 0.32 | 2.62 |

| c2422 | Putative inner membrane ABC transporter | 0.37 | 0.75 |

| c2423 | Putative AraC type regulator | 1.97 | 2.32 |

| c2429 | Hypothetical protein | 0.08 | 1.10 |

| c2430 | Hypothetical protein | 0.25 | 0.55 |

| c2431 | Hypothetical protein | 0.73 | 2.12 |

| c2432 | Putative thioesterase | 1.00 | 4.30 |

| c2434 | Putative salicyl-AMP ligase | 0.23 | 2.59 |

| c2435 | Hypothetical protein | 0.42 | 0.19 |

| c2436 | Putative pesticin receptor precursor (82) | 0.30 | 0.73 |

| c2437 | Hypothetical protein | 0.37 | 3.66 |

| c2482 | Putative outer membrane receptor for iron compound or colicin | 4.86 | 6.56 |

| c2484 | Hypothetical protein ybdM | 2.36 | 1.06 |

| c2485 | Hypothetical protein ybdN (37) | 0.51 | 0.44 |

| c2504 | Hypothetical protein | 0.27 | 1.97 |

| c2515 | Putative ABC transporter | 0.66 | 3.70 |

| c2516 | ABC transporter, FecCD transport family | 0.90 | 4.25 |

| c2520 | Hypothetical protein | 1.15 | 0.79 |

| c2521 | Hypothetical protein | 0.60 | 0.47 |

| c2522 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 0.83 | 2.79 |

| c2523 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 0.07 | 0.54 |

| c2524 | Hypothetical protein | 0.14 | 0.28 |

| c2525 | Hypothetical protein | 0.28 | 0.51 |

| yfaL | Hypothetical protein yfaL precursor | 0.09 | 0.21 |

| c3147 | Hypothetical protein | 2.68 | 5.66 |

| c3292 | Potential molybdenum-pterin-binding-protein | 0.17 | 0.10 |

| c3304 | Hypothetical protein | 0.29 | 1.17 |

| c3390 | Hypothetical protein | 1.09 | 1.68 |

| c3405 | 2-Hydroxyacid dehydrogenase | 0.12 | 0.39 |

| c3408 | Phosphotransferase (PTS) system, maltose- and glucose-specific IIABC component | 0.10 | 1.45 |

| c3509 | Putative ATP-binding protein of ABC transport system | 0.40 | 4.06 |

| c3686 | Hypothetical protein yrbH | 8.70 | 4.27 |

| c3750 | Putative regulator | 1.04 | 0.67 |

| c3753 | Ureidoglycolate dehydrogenase | 0.40 | 1.88 |

| c3755 | Hypothetical protein | 0.47 | 1.19 |

| ygiK | C4-dicarboxylate permease | 0.32 | 1.63 |

| c3770 | Hypothetical protein (74) | 1.06 | 0.96 |

| c3771 | Putative iron compound-binding protein of ABC transporter family (74) | 1.15 | 1.07 |

| c3772 | Putative iron compound permease protein of ABC transporter family (74) | 0.75 | 2.69 |

| c3773 | Putative iron compound permease protein of ABC transporter family (74) | 0.45 | 4.02 |

| c3774 | Ferric enterobactin transport ATP-binding protein fepC (74) | 0.59 | 2.60 |

| assT | Arylsulfate sulfotransferase | 1.04 | 2.40 |

| c4016 | Ribose transport ATP-binding protein rbsA | 0.14 | 0.53 |

| c4017 | Putative ribose ABC transporter | 0.10 | 0.90 |

| c4018 | Tagatose-bisphosphate aldolase gatY | 0.28 | 0.29 |

| c4205 | Hypothetical protein | 0.07 | 0.56 |

| chuS | Putative heme/hemoglobin transport protein | 3.69 | 22.21 |

| chuA | Outer membrane heme/hemoglobin receptor | 5.25 | 7.05 |

| chuT | Putative periplasmic binding protein | 2.08 | 15.52 |

| chuW | Putative oxygen-independent coproporphyrinogen I II oxidase | 3.29 | 42.74 |

| chuX | Hypothetical protein | 4.28 | 14.07 |

| chuY | Hypothetical protein | 4.62 | 3.35 |

| chuU | Putative permease of iron compound ABC transport system | 1.81 | 3.47 |

| yiaN | Hypothetical protein yiaN | 0.10 | 1.35 |

| c4481 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 1.93 | 2.70 |

| c4482 | Hypothetical protein yajF | 0.54 | 3.00 |

| c4483 | Putative aldolase | 0.18 | 0.91 |

| c4484 | Putative aldolase | 0.09 | 1.22 |

| c4485 | Putative PTS enzyme II fructose | 0.19 | 0.41 |

| c4487 | Putative PTS system, fructose specific | 0.98 | 2.32 |

| c4488 | Putative transcriptional antiterminator | 0.06 | 0.58 |

| c4580 | Hypothetical protein | 0.96 | 2.00 |

| c4735 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 0.68 | 1.03 |

| c4757 | Hypothetical protein | 1.07 | 1.72 |

| c4758 | PTS system, glucose-specific IIBC component | 0.24 | 1.01 |

| c4759 | Transketolase 1 | 0.90 | 0.75 |

| c4760 | Hypothetical protein | 0.51 | 2.06 |

| c4761 | Putative conserved protein | 0.13 | 0.50 |

| c4762 | Putative permease | 0.12 | 0.41 |

| c4763 | Hypothetical protein | 0.10 | 0.35 |

| c4764 | Carbamate kinase-like protein yahI | 1.14 | 1.53 |

| c4765 | Hypothetical protein yahG | 0.11 | 1.13 |

| c4766 | Hypothetical protein | 1.89 | 1.40 |

| c4767 | Hypothetical protein yahF | 0.48 | 1.73 |

| c4768 | Hypothetical protein | 0.42 | 1.75 |

| c4774 | Hypothetical protein | 0.84 | 1.63 |

| c4775 | Hypothetical protein | 0.17 | 0.25 |

| c4776 | Hypothetical protein | 0.35 | 1.02 |

| c4777 | Putative conserved protein | 1.13 | 1.95 |

| c4778 | Putative conserved protein | 0.13 | 1.03 |

| c4924 | Putative hippuricase | 0.68 | 0.62 |

| c4925 | Putative citrate permease | 0.14 | 0.78 |

| c4981 | Putative oxidoreductase | 0.38 | 1.58 |

| c4982 | PTS system, mannose-specific IID component | 1.09 | 1.48 |

| c4983 | PTS system, mannose-specific IIC component | 0.10 | 1.15 |

| c4984 | Putative sorbose PTS component | 0.12 | 1.86 |

| c4986 | d-Glucitol-6-phosphate dehydrogenase | 0.56 | 2.11 |

| c4987 | Putative transcriptional regulator of sorbose uptake and utilization genes | 0.41 | 0.54 |

| c5032 | 2-Oxoglutarate dehydrogenase E1 component | 0.67 | 1.49 |

| c5033 | Hypothetical protein | 0.39 | 0.99 |

| c5034 | Dihydrolipoamide succinyltransferase component of 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex | 0.12 | 0.64 |

| c5035 | Putative 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase | 0.70 | 0.88 |

| c5036 | Succinyl-CoA synthetase beta chain | 1.36 | 1.26 |

| c5037 | Succinyl-CoA synthetase alpha chain | 0.80 | 1.29 |

| c5038 | Putative membrane-bound protein | 0.55 | 2.47 |

| c5039 | Putative lactate dehydrogenase | 0.45 | 4.49 |

| c5040 | Putative C4-dicarboxylate transport transcriptional regulatory protein | 0.12 | 0.68 |

| c5060 | Hypothetical protein | 0.76 | 3.20 |

| c5061 | Hypothetical protein | 0.40 | 0.84 |

| yddO | Hypothetical ABC transporter ATP-binding protein yddO | 1.20 | 1.50 |

| c5078 | Putative oligopeptide ABC transporter | 0.09 | 0.65 |

| yddQ | Hypothetical ABC transporter permease protein yddQ | 0.65 | 0.83 |

| yddR | Hypothetical ABC transporter permease protein yddR | 0.42 | 1.39 |

| c5081 | Putative conserved protein | 2.00 | 0.67 |

CGH analysis revealed 173 genes that were present in all of the seven UPEC strains but none of the three fecal/commensal strains. In silico BSR analysis of these 173 genes revealed a subset (131 genes) that was all present in three sequenced UPEC strains (536, UTI89, and F11) but absent from the commensal strain HS. These 131 genes are also shown as the last data point in Fig. 3. Reference numbers are included for genes that were investigated elsewhere.

Microarray signal intensity from cDNA synthesized from mRNA recovered from bacteria in the urine of mice infected with E. coli CFT073 (95).

Presented as the ratio of in vivo average/in vitro average expression data from the murine transcriptome study of UPEC; in vitro data were derived from bacteria grown in LB broth (95).

These genes are listed within Table 5 and are contained within 16 clusters of ≥3 genes with no more than one missing gene (range, 3 to 12 genes; median, 5 genes), with an additional six 2-gene clusters, and 25 individual genes. CDS with hypothetical functions comprise approximately half (61/131 genes) of these UPEC-specific genes. The UPEC-specific group also contains seven CDS predicted to be involved in transcriptional regulation, 12 CDS for ABC transport systems, and the chu gene cluster involved in heme/hemoglobin utilization (103). Relative expression of these 131 genes in vivo and their upregulation in vivo relative to in vitro expression are provided from our previous study (95) (Table 5). More than half (78) of these genes had an in vivo/in vitro ratio of >1, suggesting that they are synthesized as well in vivo as in vitro. Thirty-eight of 131 genes were upregulated more than twofold in vivo.

Virulence-associated genes in UPEC strains.

While surveys of virulence factors in large strain collections have been conducted previously by us and others (2), we were nevertheless able to make unique observations using this approach. The prevalence of 11 virulence-associated genes or operons from CFT073 (sat, picU, tsh, iha, iroN, sitABCD, fyuA, iucABCD/iutA, chuSA, hlyA, and usp) were assessed in the eight UPEC and three fecal or commensal isolates (Table 6). Pyelonephritis strain CFT204 contains 8 of the 11 virulence-associated genes and appears most closely related to CFT073 in terms of gene content and presence of genomic islands (Table 6 and Fig. 1). The pyelonephritis strains generally contained the most established virulence factors (mean, 6.3), cystitis isolates contained a mean of 4.8 virulence factors, and fecal/commensal strains contained a mean of only 1.3 virulence factors (with none present in E. coli K-12). Both pyelonephritis and cystitis isolates contain significantly more virulence factors than fecal strains do (P < 0.05).

TABLE 6.

Presence of virulence-associated genes in uropathogenic and fecal/commensal E. coli strains

| Strain | Presence of virulence factora

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sat | picU | tsh | iha | iroN | sitb | fyuA | iucc | chuSA | hlyA | usp | |

| CFT073 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| CFT204 | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| CFT269 | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | − |

| CFT325 | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | + |

| F3 | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | − |

| F11 | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | − |

| F24 | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| F54 | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | + |

| EFC4 | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − |

| EFC9 | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| K-12 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

Established or putative virulence factors of UPEC.

sit, sitABCD.

iuc, iucABCD/iutA.

With respect to adhesins, 9 of the 10 strains in this study were shown by PCR to contain papG allele I or III (Table 2). papG allele I was present in all of the pyelonephritis strains, while allele III was seen in the majority (3/4) of cystitis isolates. However, the pap gene clusters showed many genes with borderline or absent array values, indicating sequence divergence at the nucleotide level. The only gene in striking contrast to this observation is fimH, the fimbrial tip adhesin of type 1 fimbriae, which is present in all 10 UPEC and fecal/commensal isolates studied by CGH (data not shown). The in silico screen of the CFT073 genome against 14 other sequenced E. coli strains revealed that the fimH gene is present in 12/14 strains, with only the two EAEC strains lacking the entire fim gene cluster, suggesting that this is a common mechanism by which many E. coli pathovars adhere.

As many as 12 putative fimbrial gene clusters have been identified in CFT073 (95, 104), 10 chaperone-usher family fimbriae, and two type IV pili. Several of these chaperone-usher pathway fimbrial gene clusters were found to be UPEC specific by CGH, including the yad/htr/ecp genes (c0166 to c0172) and CDS c4207 to c4214. In each case, the chaperone-usher genes were the most highly conserved, the adhesive tip protein was the least conserved, and the minor structural subunits showed various degrees of conservation between strains.

Type IV pili, a feature of many gram-negative bacteria, are involved in twitching motility (14, 40, 52). Type IV pili have been associated with adhesion to epithelial cells (30, 43, 100), and the extension and retraction of type IV pili have been shown to directly mediate cell movement (61, 62, 94). The type IV pilin genes c2394 and c2395 were present in all three pyelonephritis isolates and one of four cystitis isolates (F11), but not in fecal/commensal strains by CGH (data not shown). In silico BSR analysis revealed that the type IV pilin genes are present only in UPEC strains 536 and F11.

For iron acquisition, enterobactin (79), also known as enterochelin (68), functions as a catecholate siderophore in E. coli that sequesters iron from the environment and provides it in a soluble form able to be utilized by the organism. The enterobactin gene cluster (ent/fep genes) was present in all 10 E. coli strains analyzed by CGH and all 14 sequenced E. coli strains by in silico BSR analysis (data not shown). The entire iroNEDCB gene cluster, encoding the related enterobactin-like system, was found in three cystitis isolates (F3, F11, and F24) and one fecal/commensal strain (EFC9) by CGH (data not shown). The enterobactin-like gene cluster (iroNEDCB) was identified by in silico BSR analysis as present in only UTI89, 536, and F11, not in 11 other E. coli strains, and therefore, it appears to be UPEC specific.

The yersiniabactin receptor, encoded by the fyuA gene in Yersinia pestis CO92 (76), is 99.9% identical to CFT073 gene c2436 at the nucleotide level. c2436 contains no apparent premature stop codons with reference to Y. pestis. The c2436 gene, annotated as a putative pesticin receptor precursor, is present in all seven UPEC isolates but none of the fecal/commensal strains analyzed by CGH. The in silico BSR screen reveals that gene c2436 is present in the UPEC strains UTI89, 536, and F11 as well as EPEC strain E110019 and EAEC strain 042. The sitABCD operon is an iron transport system in CFT073 that was present in all three pyelonephritis isolates, three of four cystitis isolates and one fecal/commensal strain by CGH. In addition, as determined by BSR analysis, the three UPEC strains and the EAEC strain O42 contain the sitABCD operon, while this iron transport system was absent from 10 other E. coli strains. The chuS (c4307) and chuA genes (c4308), involved in heme/hemoglobin transport and binding, respectively, are present in all seven UPEC strains (three pyelonephritis and four cystitis isolates) but none of the fecal/commensal strains as examined by CGH. The chuSA genes are also present in the UPEC strains UTI89, 536, and F11, the EHEC strains EDL933 and Sakai, and EAEC strain O42 as measured by BSR. However, these genes are absent from all other E. coli strains examined, including the commensal strain HS and the laboratory-adapted commensal strain K-12 MG1655.

All genera within the family Enterobacteriaceae are capable of producing a layer of strain-specific, surface-associated polysaccharides known as capsule (88). Some forms of capsule have been strongly associated with extraintestinal E. coli infections, including urinary tract infection (45, 53, 72). The kpsMT genes of CFT073 encode the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter components of the group II capsule gene locus (10), have been associated with virulence in UPEC (29), and were present in a single pyelonephritis strain (CFT204) in the CGH analysis. The capsule genes in both UPEC and fecal/commensal E. coli were diverse in strains based upon DNA hybridization to the arrays. This likely indicates that different strains express different capsular types.

The autotransporter genes sat and picU, found in CFT073, were identified in only the pyelonephritis strains CFT325 and CFT204, respectively. In contrast, the autotransporter tsh (also referred to as vat or hemoglobin protease) (39) was present in all pyelonephritis isolates and three cystitis isolates (F3, F11, and F24).

The uropathogenic specific protein (usp) is encoded by gene c0133 in CFT073 and was identified in one pyelonephritis isolate and one cystitis isolate but in none of the fecal/commensal strains by CGH (data not shown). Furthermore, BSR analysis supported the results of previous studies showing that the usp gene is UPEC specific. The usp gene was present in all three UPEC strains but none of the EHEC, ETEC, EPEC, rabbit enteropathogenic Escherichia coli, EAEC, or fecal/commensal E. coli isolates (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

With the escalating number of bacterial genome sequences available, CGH microarray analysis is an increasingly popular tool to study pathogenic microorganisms. CGH is a comprehensive analytical tool permitting the examination of multiple bacterial strains at the whole-genome level, providing data about the acquisition and loss of genetic information, the potential evolutionary lineages of pathogens, and the identification of virulence-associated and/or strain-specific genes. Recently, a number of important bacterial pathogens of humans and animals have been analyzed using CGH, including Bordetella pertussis (23), Vibrio cholerae (26), Helicobacter pylori (85), Coxiella burnetti (3), Yersinia pestis (42), and Aeromonas salmonicida (67).

This is the first study to use CGH microarray analysis to compare a collection of uropathogenic and fecal/commensal E. coli isolates. This approach permits the identification of genomic islands and genes specific to UPEC isolates. Genomic DNA from three pyelonephritis isolates, four cystitis isolates, and three fecal/commensal E. coli strains were hybridized to an E. coli CFT073 whole-genome microarray. Seven new genomic islands were delineated and characterized in CFT073, the details of the two previously known PAIs in this strain were revised, and a third PAI of CFT073 was analyzed in greater detail than that previously published. The prevalence of established or putative virulence factors of UPEC was analyzed across the 11 E. coli strains. Furthermore, this study has demonstrated that unrelated UPEC isolates hybridize to the CFT073 microarray, with approximately 77% of the CFT073 genes present in other UPEC isolates.

Genes found to be conserved in all UPEC strains but not found in fecal or commensal strains (Table 5) are perhaps not those that would be expected. When one considers urovirulent strains, specific virulence determinants come to mind, including P, S, or F1C fimbriae, hemolysin, cytotoxic necrotizing factor, autotransporters, and certain iron acquisition systems. Despite being characteristic of uropathogenic strains, genes encoding these virulence factors are not found in every strain. On the contrary, half of UPEC-specific genes identified in this study predicted proteins with no known homologs or function. This indicates that these strains possess invariant genes for which the role in uropathogenesis is not known. Our findings also suggest that ABC transport of several unknown substrates may be critical and that the Chu heme uptake system is important. Implication as a virulence factor, however, requires the testing of complementable mutations in the murine model of UTI. Finally, the identification of the target genes of seven predicted transcriptional regulators may reveal more about the mechanisms of urovirulence. Finding that 106 of the 131 genes present in all UPEC strains are found within 22 gene clusters of 2 or more genes indicates that UPEC-specific genes are not randomly distributed in these strains; rather, operons likely encode systems that contribute to pathogenesis or survival in the urinary tract.

Three PAIs, PAI-CFT073-pheV (PAI ICFT073), PAI-CFT073-pheU (PAI IICFT073), and PAI-CFT073-asnT (HPICFT073) have previously been identified in UPEC strain CFT073 (32, 70, 81). Some confusion, however, currently exists in the literature as to the correct annotation of PAIs in CFT073, as subsequent analysis showed that the original annotation of PAI-CFT073-pheV (PAI ICFT073) and PAI-CFT073-pheU (PAI IICFT073) contained errors. We are now able to clarify and expand on these findings based upon our CGH data by using the CFT073 whole-genome microarray. Nomenclature for these new PAIs and GIs has been proposed based upon the existing PAIs in this and other UPEC strains (25, 66) (Table 4). PAI-CFT073-pheV (PAI ICFT073) (32) was originally reported to be 58.0 kb and to contain a pap operon, hemolysin, and iron-regulated genes. Our current study has shown that PAI-CFT073-pheV (PAI ICFT073) is ∼123 kb in length, has a G+C content of 47%, is located at the pheV tRNA locus and contains hlyA (c3570), the first CFT073 pap operon (c3582-c3593), iha (c3610), sat (c3619), iutA (c3623), iucDCBA (c3624-c3628), antigen 43 precursor (c3655), and kpsTM (c3697-c3698). The original annotation of PAI-CFT073-pheU (PAI IICFT073) (81) contained errors related to rearrangements in cosmid clones, resulting in incorrectly assembled sequence from distinct regions of the genome. This PAI was annotated as being at least 71.7 kb, although insertion sites at the boundary of the island were never identified. We have shown that PAI-CFT073-pheU (PAI IICFT073) is 52 kb in length, has a G+C content of 48%, is located at the pheU tRNA locus, and contains the pap_2 operon (c5179-c5189).

Parham and colleagues (75) recently identified a 100-kb PAI in CFT073 which they reported to be the correctly annotated PAI-CFT073-pheU (PAI IICFT073) originally identified by Rasko et al. (81). However, previous studies of PAI-CFT073-pheU (PAI IICFT073) (8, 81, 96, 104) consistently mention the presence of the second pap operon of CFT073 (c5179-c5189) within this island. The PAI identified by Parham and colleagues is identical to genomic island 1 identified in this study (c0253-c0368). However, since this PAI does not contain the pap_2 operon, it cannot be referred to as PAI-CFT073-pheU (PAI IICFT073); we therefore propose that this PAI be renamed PAI-CFT073-aspV (PAI IIICFT073).

The HPI of Yersinia pestis encodes the yersiniabactin iron acquisition system (18). The HPI has been identified in members of the Enterobacteriaceae family that are pathogenic to humans (91) and was present in 71% of E. coli urine isolates and 75% of E. coli blood isolates (90). Although the HPI has been documented in E. coli CFT073 previously (70), it was not well characterized. The HPI of CFT073 has subsequently been reported to contain premature stop codons in several genes, corresponding to an absence of detectable yersiniabactin production (16). The HPI of E. coli CFT073 (PAI-CFT073-asnT [HPICFT073]) has been further examined in Table 4. In this study, the PAI-CFT073-asnT (HPICFT073) was present in 100% of pyelonephritis and cystitis isolates but none of the fecal/commensal strains. In three pathogenic Yersinia species, the HPI was inserted at one of three asn tRNA genes (17) and the PAI-CFT073-asnT (HPICFT073) is also located at an asn tRNA gene in CFT073. It should be noted that data from CGH microarrays indicate the presence of only DNA sequences and does not indicate the functionality of a CDS.

These genomic islands are frequently associated with tRNA genes, generally have G+C contents that differ from that of CFT073, and contain integrases, transposases, and phage sequences, all of which are common characteristics of bacterial PAIs (33, 34). In each of the genomic and phage islands, the majority of CDS predict hypothetical or putative functions, which is highly suggestive of additional genes with potential roles in virulence. For example, PAI-CFT073-aspV (PAI IIICFT073) is 100 kb in length and contains 99 hypothetical or putative CDS, GI-CFT073-selC is 68 kb and contains 76 CDS with hypothetical or putative functions, and even the most well-characterized PAI of CFT073, PAI-CFT073-pheV (PAI ICFT073), is 123 kb and contains 86 uncharacterized CDS.

Sequence alignments revealed that two of the genomic islands in strain CFT073 were found in five sequenced bacterial genomes. φ-CFT073-b0847 was identified in E. coli E2348/69 (EPEC), Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi TY2, and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2, whereas PAI-CFT073-asnT (HPICFT073) was present in E. coli O42 (EAEC) and Yersinia pestis CO92. The 11 remaining PAIs were not identified in their entirety in any of the strains analyzed. Some of the PAIs appeared to have been composed of smaller genomic islands, indicated by internal insertion sequences and differences in gene content between strains. Over time, these smaller genomic regions may have become parts of larger islands that acquire virulence genes and are mobilized together between strains as PAIs. Alternatively, these regions may be remnants of larger islands that have been lost over time in these isolates. PAIs frequently have a mosaic-like structure which has been generated by a multistep process of genomic acquisition, loss, and rearrangement (34).

In a comparative analysis of newly sequenced E. coli 536, Brzuszkiewicz and colleagues noted that the primary difference between strains 536 and CFT073 was restricted to large PAIs that were unique to 536 or CFT073 (16). Indeed, they were able to predict or confirm the presence of six islands in CFT073 associated with aspV, serX, selC, aspV, pheV, and pheU. In our study, we precisely delineated these islands along with additional islands. Interestingly, they noted that 432 genes were present in both 536 and CFT073. Using additional strains in our analysis, we restricted the number of genes common to UPEC to 131.

The eight UPEC isolates were of the common UPEC-associated O serogroups (O1, O2, O4, O6, O7, O8, O16, O18, O25, and O75) (48, 71). Several serotypes were found in more than one UPEC isolate, confirming that randomly selected UPEC isolates demonstrate similarities in serotypes. Two of the pyelonephritis strains had the serotype O6:H1, two cystitis isolates were O18:H7, and the representative cystitis isolate F11 (97) had the same serotype as another well-characterized UPEC isolate, E. coli 536 (O6:H31) (35).

A strong correlation between the production of class III P-fimbrial adhesin (papG allele III), α-hemolysin (hly), S-fimbrial adhesin (sfa), and cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 (cnf1) has been shown by Mitsumori and colleagues (63), with 87% of UPEC strains analyzed containing these four genes. Similarly, 75% of the cystitis isolates in this study were positive for cnf1, papG allele III, sfa and hly, whereas this profile was not observed for any of the pyelonephritis or fecal/commensal E. coli strains (Table 2). The class III papG allele is predominantly found in cystitis isolates (1, 63, 99). As shown in Table 2, 75% of the cystitis isolates contained papG allele III, whereas 80% of the pyelonephritis isolates contained papG allele I.

One of the most striking findings of this study was high prevalence of iron acquisition systems in UPEC isolates and the obvious importance of iron sequestration and transport in the urinary tract. An analysis of the enterobactin (ent/fep), enterobactin-like (iro), aerobactin (iuc/iut), yersiniabactin (fyu), iron transport (sit), and heme (chu) systems clearly illustrated the importance of iron for the survival of UPEC in the urinary tract. All seven UPEC isolates, in addition to CFT073, contained between three and five of these iron acquisition systems, with an average of four per strain. The fecal/commensal strains contained two or three iron-related operons, while K-12 contained only the enterobactin system, which was present in all 10 E. coli strains examined. The enterobactin-like genes were predominantly found in cystitis strains, whereas the aerobactin system was more prevalent in pyelonephritis isolates. In contrast, the heme/hemoglobin gene cluster (chu) was found in almost all UPEC isolates but was absent in the fecal/commensal strains. Torres and colleagues showed that an isogenic chuA mutant of CFT073 was significantly outcompeted by the wild-type strain in both the bladders and kidneys of mice (103), and the chu locus has shown to be associated with ExPEC isolates causing neonatal meningitis (12). Heme/hemoglobin utilization may be more important in the later stages of a UTI, where heme and hemoglobin are released following the lysis of host cells. The prototypic pyelonephritogenic isolate CFT073 contains all six iron systems mentioned above, five of which were highly upregulated in vivo (95). This redundancy in iron acquisition systems may provide a competitive advantage to UPEC in vivo in terms of growth and survival over E. coli strains lacking these alternative iron acquisition systems.

CGH analysis does have limitations and may not accurately represent genes with divergent sequences at the nucleotide level. The array signal is dependent upon DNA hybridization to the probes, and low sequence identity results in poor recognition of the probe sequence. The use of at least 17 probes for every CDS in CFT073 partially compensates for this, as regions of minor sequence divergence generally do not adversely affect overall hybridization. In contrast, substantial divergence across the entire gene sequence results in low normalized signal intensities from the array. Genes, operons, or genomic islands that are absent are generally evident, resulting in regions with very low normalized data signals. Similarly, genes that are clearly present give high normalized signals. However, genes that have divergent nucleotide sequences tend to give values close to the cutoff value, often with some CDS in an operon appearing present and others appearing absent. This was observed with the fimbrial genes of CFT073, which showed substantial sequence divergence and consequently hybridized poorly to the microarray. PCR analysis revealed that all UPEC strains contained either papG allele I or papG allele III, and yet the microarray suggested that the pap operon was absent from or only partially present in all strains. Although the type 1, P, and S/F1C operons gave variable results, there were clear trends within these data. The adhesin genes were the least conserved betweens strains, whereas the chaperone-usher genes were most conserved. Chaperone-usher genes perform very similar functions in strains and, therefore, require a similar structure, as sequence divergence would only reduce their efficiency. In contrast, it is beneficial for bacterial pathogens to differ in their adhesin moieties, which may provide an advantage for survival in different niches. It has been proposed that the three papG alleles in UPEC confer differences in receptor binding specificity, resulting in differences in host range (59, 101) or clinical presentation (46, 73), and a similar argument can be made for other adhesins. The only exception to this observation was the fimH adhesin of type 1 fimbriae, which was highly conserved among all E. coli strains analyzed and was present in 100% of strains by microarray (data not shown). Type 1 fimbriae are found in more than 90% of uropathogenic and commensal E. coli strains (4, 36, 47, 106) but nevertheless contribute significantly to the virulence of UPEC isolates (21, 31, 55). A recent CGH study comparing 11 ExPEC isolates, all E. coli K1 strains from the cerebral spinal fluid of patients with meningitis, showed sequence divergence in the adhesin gene of F1C fimbriae and of another gene, hek, identified only as an adhesin/virulence factor (107). These findings support the hypothesis that adhesin genes are not highly conserved between E. coli strains.

The hybridization of genomic DNA to conventional microarrays is a powerful approach to studying the genomic content of multiple bacterial strains, and comparisons between pathogenic and commensal isolates permit the identification of novel virulence factors. One weakness of the CGH approach is that only genes present in the array strain can be analyzed in other strains. Nevertheless, sequenced bacterial genomes are generally based upon a representative isolate from a specific disease or clinical syndrome and, therefore, will contain numerous virulence factors, including strain- or subtype-specific genes or PAIs. Whole-genome analysis provides data on a scale that cannot be compared to any other technique, allowing insight into the genomic content of an entire organism(s) and the ability to identify trends across strains.

The E. coli CFT073 genome contains 5,379 CDS, and therefore, an analysis of these genes across multiple strains provides a much broader and more extensive understanding of UPEC isolates and how the gene content compares to fecal/commensal E. coli strains. This is the first study using both experimental and bioinformatic approaches to compare the genomic content of a collection of uropathogenic and fecal/commensal E. coli isolates. One of the most significant findings was the identification and characterization of seven additional genomic islands in strain CFT073, opening the way for subsequent studies of the many CDS that have been annotated with hypothetical or putative functions as well as closer comparisons between the CFT073 PAIs and other well-characterized UPEC PAIs, such as strains 536 (25) and J96 (102).

Acknowledgments

We thank Victor DiRita and Chris Alteri for critical reading of the manuscript, Tom Albert (NimbleGen) for assistance with interpreting and analyzing microarray data, and Chobi DebRoy (Gastroenteric Disease Center, Pennsylvania State University) for serotyping of E. coli isolates.

Funding for this research was provided by Public Health Service grants AI043363 and AI059722 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 February 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arthur, M., C. E. Johnson, R. H. Rubin, R. D. Arbeit, C. Campanelli, C. Kim, S. Steinbach, M. Agarwal, R. Wilkinson, and R. Goldstein. 1989. Molecular epidemiology of adhesin and hemolysin virulence factors among uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 57:303-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bahrani-Mougeot, F. K., N. W. Gunther IV, M. S. Donnenberg, and H. L. T. Mobley. 2002. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli p. 239-268. In M. S. Donnenberg (ed.), Escherichia coli: virulence mechanisms of a versatile pathogen. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

- 3.Beare, P. A., J. E. Samuel, D. Howe, K. Virtaneva, S. F. Porcella, and R. A. Heinzen. 2006. Genetic diversity of the Q fever agent, Coxiella burnetii, assessed by microarray-based whole-genome comparisons. J. Bacteriol. 188:2309-2324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergsten, G., B. Wullt, and C. Svanborg. 2005. Escherichia coli, fimbriae, bacterial persistence and host response induction in the human urinary tract. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 295:487-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergthorsson, U., and H. Ochman. 1998. Distribution of chromosome length variation in natural isolates of Escherichia coli. Mol. Biol. Evol. 15:6-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beutin, L., Q. Kong, L. Feng, Q. Wang, G. Krause, L. Leomil, Q. Jin, and L. Wang. 2005. Development of PCR assays targeting the genes involved in synthesis and assembly of the new Escherichia coli O174 and O177 O antigens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:5143-5149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bingen, E., B. Picard, N. Brahimi, S. Mathy, P. Desjardins, J. Elion, and E. Denamur. 1998. Phylogenetic analysis of Escherichia coli strains causing neonatal meningitis suggests horizontal gene transfer from a predominant pool of highly virulent B2 group strains. J. Infect. Dis. 177:642-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bingen-Bidois, M., O. Clermont, S. Bonacorsi, M. Terki, N. Brahimi, C. Loukil, D. Barraud, and E. Bingen. 2002. Phylogenetic analysis and prevalence of urosepsis strains of Escherichia coli bearing pathogenicity island-like domains. Infect. Immun. 70:3216-3226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blattner, F. R., G. Plunkett III, C. A. Bloch, N. T. Perna, V. Burland, M. Riley, J. Collado-Vides, J. D. Glasner, C. K. Rode, G. F. Mayhew, J. Gregor, N. W. Davis, H. A. Kirkpatrick, M. A. Goeden, D. J. Rose, B. Mau, and Y. Shao. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277:1453-1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bliss, J. M., and R. P. Silver. 1996. Coating the surface: a model for expression of capsular polysialic acid in Escherichia coli K1. Mol. Microbiol. 21:221-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blum, G., M. Ott, A. Lischewski, A. Ritter, H. Imrich, H. Tschape, and J. Hacker. 1994. Excision of large DNA regions termed pathogenicity islands from tRNA-specific loci in the chromosome of an Escherichia coli wild-type pathogen. Infect. Immun. 62:606-614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonacorsi, S. P., O. Clermont, C. Tinsley, I. Le Gall, J. C. Beaudoin, J. Elion, X. Nassif, and E. Bingen. 2000. Identification of regions of the Escherichia coli chromosome specific for neonatal meningitis-associated strains. Infect. Immun. 68:2096-2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyd, E. F., and D. L. Hartl. 1998. Chromosomal regions specific to pathogenic isolates of Escherichia coli have a phylogenetically clustered distribution. J. Bacteriol. 180:1159-1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradley, D. E. 1980. A function of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO polar pili: twitching motility. Can. J. Microbiol. 26:146-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brumfitt, W., R. A. Gargan, and J. M. Hamilton-Miller. 1987. Periurethral enterobacterial carriage preceding urinary infection. Lancet i:824-826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brzuszkiewicz, E., H. Bruggemann, H. Liesegang, M. Emmerth, T. Olschlager, G. Nagy, K. Albermann, C. Wagner, C. Buchrieser, L. Emody, G. Gottschalk, J. Hacker, and U. Dobrindt. 2006. How to become a uropathogen: comparative genomic analysis of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli strains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:12879-12884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchrieser, C., R. Brosch, S. Bach, A. Guiyoule, and E. Carniel. 1998. The high-pathogenicity island of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis can be inserted into any of the three chromosomal asn tRNA genes. Mol. Microbiol. 30:965-978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buchrieser, C., M. Prentice, and E. Carniel. 1998. The 102-kilobase unstable region of Yersinia pestis comprises a high-pathogenicity island linked to a pigmentation segment which undergoes internal rearrangement. J. Bacteriol. 180:2321-2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chaudhuri, R. R., A. M. Khan, and M. J. Pallen. 2004. coliBASE: an online database for Escherichia coli, Shigella and Salmonella comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:D296-D299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen, S. L., C. S. Hung, J. Xu, C. S. Reigstad, V. Magrini, A. Sabo, D. Blasiar, T. Bieri, R. R. Meyer, P. Ozersky, J. R. Armstrong, R. S. Fulton, J. P. Latreille, J. Spieth, T. M. Hooton, E. R. Mardis, S. J. Hultgren, and J. I. Gordon. 2006. Identification of genes subject to positive selection in uropathogenic strains of Escherichia coli: a comparative genomics approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:5977-5982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Connell, I., W. Agace, P. Klemm, M. Schembri, S. Marild, and C. Svanborg. 1996. Type 1 fimbrial expression enhances Escherichia coli virulence for the urinary tract. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:9827-9832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Louvois, J. 1994. Acute bacterial meningitis in the newborn. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 34(Suppl. A):61-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diavatopoulos, D. A., C. A. Cummings, L. M. Schouls, M. M. Brinig, D. A. Relman, and F. R. Mooi. 2005. Bordetella pertussis, the causative agent of whooping cough, evolved from a distinct, human-associated lineage of B. bronchiseptica. PLoS Pathogens 1:e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dobrindt, U., F. Agerer, K. Michaelis, A. Janka, C. Buchrieser, M. Samuelson, C. Svanborg, G. Gottschalk, H. Karch, and J. Hacker. 2003. Analysis of genome plasticity in pathogenic and commensal Escherichia coli isolates by use of DNA arrays. J. Bacteriol. 185:1831-1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dobrindt, U., G. Blum-Oehler, G. Nagy, G. Schneider, A. Johann, G. Gottschalk, and J. Hacker. 2002. Genetic structure and distribution of four pathogenicity islands (PAI I536 to PAI IV536) of uropathogenic Escherichia coli strain 536. Infect. Immun. 70:6365-6372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]