Only 12% of consultants in England believe that patient care has improved under the new consultants' contract, a critical report by the National Audit Office (NAO) says.

The contract was implemented in 2003 and was supposed to provide better services for patients; increase productivity through improved management of consultants' work; and reward consultants for their NHS work through higher pay. It is based on an agreed “job plan” made up of 10 programmed activities of four hours each. The contract is the first update since the NHS was formed in 1948.

But a survey from the NAO of 2361 consultants compared time spent before and after implementation on patient care and showed no increase in time spent on direct care.

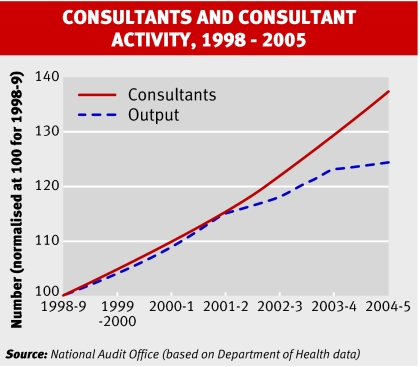

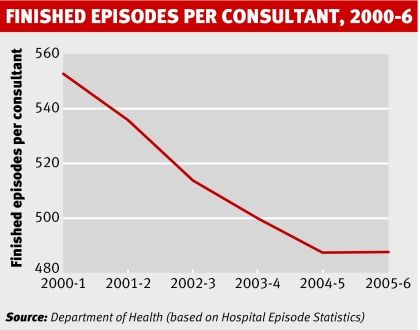

It also found that although consultants are paid an average of 25% more for doing the same or fewer hours than three years ago, their morale has fallen, with some admitting to adopting a “clockwatching attitude.” Hours of work have decreased since the contract came in, from an average of 51.6 to 50.2 a week.

“The contract has yet to deliver the full value for money to the NHS and the public that the Department [of Health] expected,” it says.

In negotiations it was agreed that the contract would be based on an average working week of 43 hours, although most consultants work longer hours.

Staff at 208 NHS acute and mental health trusts were also asked their opinion of the contract. Most (90%) thought the contract had been implemented in a hurry. And although half felt that their job plan did not reflect their working hours, 70% thought that their new salary better reflected their workload. Only 11%, however, thought that time spent on clinical care had increased.

Costs seem to have been underestimated by the Department of Health, which originally set aside an extra £565m (€831m; $1131m) over three years for the contract but had to add a further £150m after trusts reported that it was more expensive than predicted.

Trusts don't limit costs when working out job plans so they agreed to more hours than budgeted for, which led to overspending, the report points out. Eighty four per cent of the chief executives asked said that they did not think the contract was fully funded.

The report's author, Andy Fisher, said, “Consultants are often managed by clinical and medical directors who are in these jobs temporarily for just two or three years. They don't have the management skills to manage their peers.”

Linking pay to outcomes, as has been done in the Welsh version of the contract, would be a step towards improving productivity in England, the NAO says.

In Wales, trusts use “consultant outcome indicators” as part of job planning and to review the individual performance of consultants. Wales has also set aside management time for linking job plans with the modernisation agenda so that trusts can identify real examples of improvements achieved through job plans.

“The contract is capable of being adapted. We need better tools and better job plans,” said Karen Taylor, director for health value for money for the NAO. “There is a need for a proper evaluation of what has worked and economic modelling which would give [the department] a stronger position to provide evidence and guidance to individual trusts. The problems that we see now are due to that lack of modelling.”

The NAO said that the contract had improved the management of consultants and given more information on what they do. Time spent on private practice has slightly fallen since the contract came in.

The survey, Pay Modernisation: a New Contract for NHS Consultants in England, is at www.nao.org.uk.