1. Executive summary

Purpose of report

This document has been commissioned by the British Society of Gastroenterology. It is intended to draw together the evidence needed to fill the void created by the absence of a national framework or guidance for service provision for the management of patients with gastrointestinal and hepatic disorders. It sets out the service, economic and personal burden of such disorders in the UK, describes current service provision, and draws conclusions about the effectiveness of current models, based on available evidence. It does not seek to replicate existing guidance, which has been produced for upper and lower gastrointestinal cancers, hepatobiliary and pancreatic disorders, and many chronic disorders of the gut. It does, however, draw on evidence contained in these documents. It is intended to be of value to patient groups, clinicians, managers, civil servants, and politicians, particularly those responsible for developing or delivering services for patients with gastrointestinal disorders.

Methods used

A systematic review of the literature was undertaken to document the burden of disease and to identify new methods of service delivery in gastroenterology. This systematic review was supplemented by additional papers, identified when the literature on incidence, mortality, morbidity, and costs was assessed.

Routine data sources were interrogated to obtain additional data on burden of disease, the activity of the NHS, and costs, in relation to gastrointestinal disorders.

The views of users of the service were sought, through discussions with the voluntary sector and through a workshop held at the Royal College of Physicians in December 2004.

The views of professionals were obtained by wide dissemination of the document in a draft form, seeking feedback on the content and additional material.

Main findings

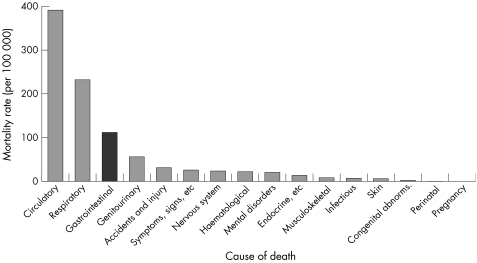

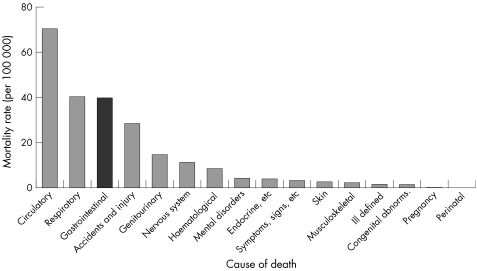

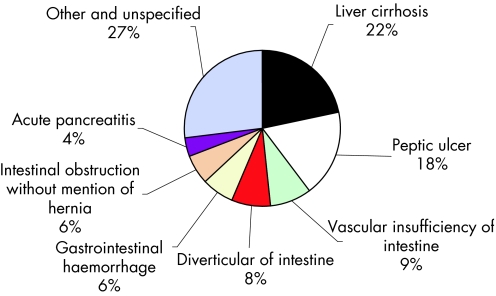

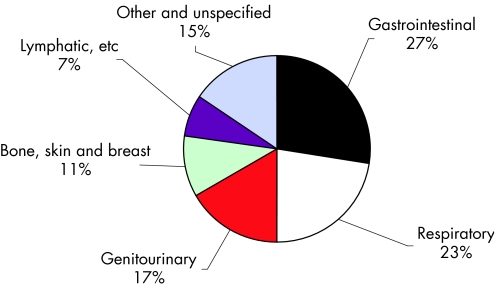

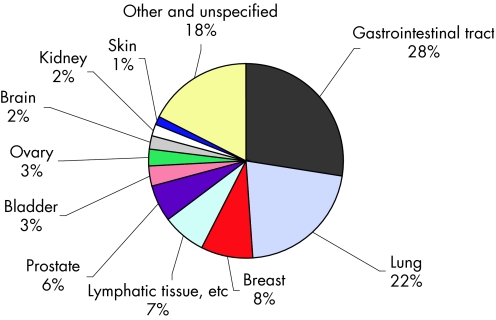

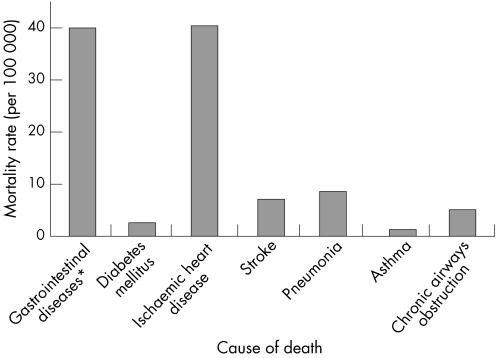

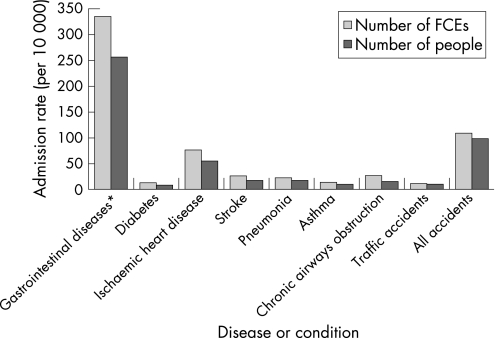

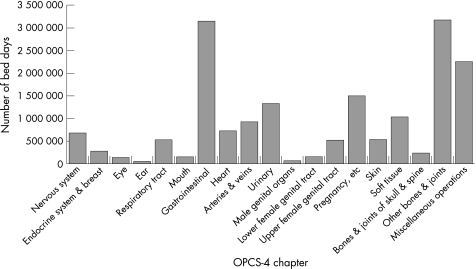

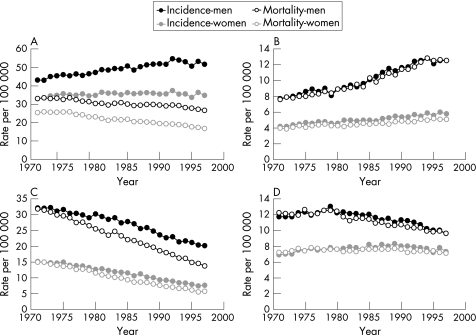

The burden of gastrointestinal and liver disease is heavy for patients, the NHS, and the economy, with gastrointestinal disease the third most common cause of death, the leading cause of cancer death, and the most common cause of hospital admission. There have been increases in the incidence of most gastrointestinal diseases which have major implications for future healthcare needs. These diseases include hepatitis C infections, acute and chronic pancreatitis, alcoholic liver disease, gallstone disease, upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage, diverticular disease, Barrett's oesophagus, and oesophageal and colorectal cancers. Socioeconomic deprivation is linked to a number of gastrointestinal diseases, such as gastric and oesophageal cancers, hepatitis B and C infections, peptic ulcer, upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage, as well as poorer prognosis for colorectal, gastric, and oesophageal cancers.

The burden on patients' health related quality of life has been found to be substantial for symptoms, activities of daily living, and employment, with conditions with a high level of disruption to sufferers' lives found to include: gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease, dyspepsia, irritable bowel syndrome, anorectal disorders, gastrointestinal cancers, and chronic liver disease. However, impact on patients is neither fully nor accurately reflected in routine mortality and activity statistics and although overall, the burden of gastrointestinal disease on health related quality of life in the general population appears to be high, the burden is neither systematically nor comprehensively described.

An overwhelming finding concerning evidence related to service delivery is the lack of high quality health technology assessment and evaluation. In particular, evidence of cost effectiveness from multicentre studies is lacking, with more research needed to establish a robust evidence base for models of service delivery.

Waiting times form the bulk of patients' concerns, with great difficulty in meeting government standards for referral and treatment. An extensive and systematic study of the problem of access for the delivery of gastrointestinal services has yet to be carried out and significant publications reporting inequalities in the delivery of gastrointestinal services are lacking. There is also a need to increase awareness and the implementation of initiatives aimed at improving the information flow between patients and practitioners.

Strong evidence exists, however, for a shift in care towards greater patient self management for chronic disease. The development of general practitioners with a special interest in gastroenterology is supported in primary care, but their clinical and cost effectiveness need to be researched. Indeed, emphasis needs to be given to developing interventions to increase preventative activities in primary care, and more research is required to determine their effectiveness and cost effectiveness.

Despite strong support for the development and use of widespread screening programmes for a wide variety of gastrointestinal diseases, there is a lack of evidence about how they are managed, their effectiveness, and their cost effectiveness. In contrast, a strong body of evidence exists on diagnostic services, and the need to develop and implement appropriate training and stringent assessment to ensure patient safety. There is also a substantial amount of work detailing guidelines for care.

In hospital, patients with gastrointestinal disorders should be looked after by those with specialist training, and more diagnostic endoscopies could be undertaken by trained nurses. Importantly, for service reconfiguration, there is currently insufficient evidence to support greater concentration of specialists in tertiary centres. More research is needed especially on the impact on secondary services before further changes are implemented.

Consultant gastroenterologist numbers need to increase to meet a rising burden of gastrointestinal disease. Gastroenterology teams should be led by consultants, but include appropriate non‐consultant career grade staff, specialist nurses, and other staff with integrated specialist training, where appropriate.

More research is needed into the delivery and organisation of services for patients with gastrointestinal and liver disorders, in particular to assess the clinical and cost effectiveness of general practitioners with a special interest in gastroenterology and endoscopy; the clinical and cost effectiveness of undertaking endoscopy or minor gastrointestinal surgery in diagnosis and treatment centres; and the reconfiguration of specialist services and the potential impact on secondary and primary care and on patients.

2. Introduction

2.0 Background including policy drivers

This document has been commissioned by the British Society of Gastroenterology. It is intended to draw together the evidence needed to fill the void created by the absence of a national framework or guidance for service provision for the management of patients with gastrointestinal (GI) and hepatic disorders. It sets out the service, economic and personal burden of such disorders in the UK, describes current service provision, and draws conclusions about the effectiveness of current models, based on the presently available evidence. It does not seek to replicate existing guidance, which has been produced for upper and lower gastrointestinal cancers, hepatobiliary and pancreatic disorders, and many chronic disorders of the gut. It does, however, draw on evidence contained in these documents.

The document takes into account recent strategies for the NHS in the UK, and recommendations for quality and service improvement, new information strategies in England and Wales. In particular, it builds on the recommendations of three reports from Derek Wanless, which have significantly influenced the strategic direction of the NHS.

In July 2000 the Government published the NHS plan which set out the core principles for the NHS and a framework for delivering these principles over the next decade. Following on from this the Chancellor of the Exchequer commissioned the first Wanless Report1 to examine future health trends and resources required over the next two decades. The report welcomed the Government's intention to extend the National Service Framework (NSF) approach to other disease areas and recommended that the NSFs and their equivalents in the developed administrations are rolled out in a similar way to the diseases already covered. It also recommended that a more effective partnership between health professionals and the public should be facilitated in a number of ways. These include setting standards for the service to help give people a clearer understanding of what the health service will and will not provide for them. Other factors include improving health information, reducing key health risk factors, and reinforcing patient involvement in NHS activities.

These recommendations were repeated and reinforced in a report on the NHS in Wales advised by Sir Derek Wanless.2 The report re‐emphasised the need for sustainable change: a shift in delivery from secondary care towards greater care in the community and more self management by patients; and significant investment in improving information and information technology. The report also emphasised the importance of change based on evidence. The third Wanless report3 emphasised the need for improvements in public health and the need for greater investment in prevention and risk reduction.

2.1 Aims and objectives

This review aims at describing how best to provide services for patients with gastrointestinal disorders from a professional and patient perspective, based on available evidence on disease burden and service provision.

Its objectives are to:

-

Review and synthesise published research evidence and routine data concerning the burden of GI diseases on

-

-

Patients—their mortality, morbidity, and quality of life

-

-

The NHS—its volume and cost

-

-

The economy of the UK.

-

-

Systematically review and synthesise research findings concerning the effectiveness of models of service provision for GI diseases and the cost effectiveness of GI services.

Describe the patients perspective on emerging issues of service delivery highlighted through the literature review as undergoing change.

Draw conclusions about optimal service provision based on evidence of burden and effectiveness, patients' view and in the current policy and service context.

The report covers the broad spectrum of GI and liver conditions. It does not examine disorders of nutrition, both malnutrition and obesity, as these have been dealt with in detail elsewhere.4,5,6

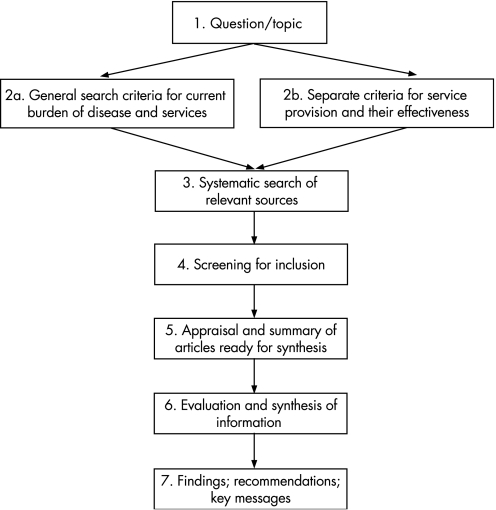

2.2 Overview of methods

Four methods were used in the generation of this document:

A systematic review of the literature was undertaken to identify research papers concerning the effectiveness of methods of service delivery in gastroenterology. This systematic review was supplemented by additional papers identified when the publications on incidence, mortality, morbidity, service activity, and costs were assessed. Some further papers were identified and included from consultation feedback.

Routine data sources were interrogated to identify additional data on burden of disease and the activity of the NHS in relation to GI disorders.

The views of users of the service were sought, through discussions with the voluntary sector and through a workshop held at the Royal College of Physicians in December 2004.

The views of professionals were obtained by wide dissemination of the document in a draft form, seeking feedback on the content and additional material. The full draft report was presented at the BSG annual conference in March 2005, alongside a strategy document outlined by the BSG president, based on the review findings. After this meeting, comments were invited, and the online report was made available to the BSG membership through a web link. In addition, patient representative groups and other GI specialist organisations were contacted to gain feedback. Comments were received over a 6 month period after release of the first draft, and these were incorporated where they were supported by evidence from well designed and reported research studies. Table A.13 summarises and appraises these papers.

More detail of the methods used is given in the appropriate sections of the document.

3. Burden of gastrointestinal and liver disease in the UK

3.0 Methods and data limitations

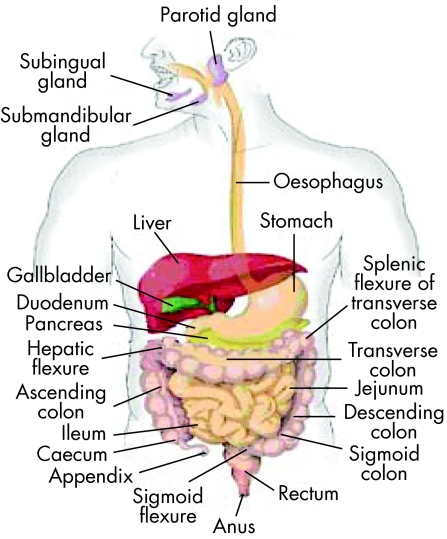

Figure 1 The digestive system. Source: Department of Gastroenterology, University of Miami, 2005.7

Gastrointestinal and liver disorders affect people of all ages. Some disorders are acute and life threatening, others are more chronic, less dangerous to life, but severely debilitating. Gastrointestinal cancers are common—some are curable, others are almost invariably fatal. Bowel problems cause considerable distress in the elderly. The care and management of such diverse problems requires contributions from a wide variety of professions.

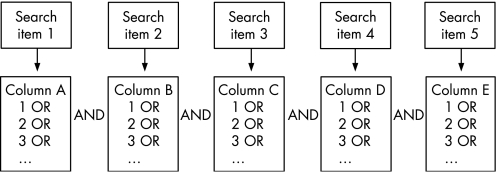

The main methods used in this chapter involved extensive and comprehensive searches of the literature on incidence, prevalence, mortality, and patients' quality of life for the various gastrointestinal diseases in the UK and, for comparative purposes, for those in other European or Western countries. Part of the literature had been already compiled through reviews undertaken during the course of previous studies of the incidence and mortality of gastrointestinal diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, liver cirrhosis, and acute pancreatitis.

The literature searches were primarily undertaken on the Medline and Embase databases with “incidence”, “prevalence”, “case fatality”, “mortality”, “quality of life”, “death rate”, “hospital”, “admission”, “gastrointestinal”, “review”, “epidemiology”, “aetiology”, “trend”, “population”, “rate”, “100 000”, “10 000”, “million”, “UK”, “England”, “Scotland”, “Wales”, other countries, and the various gastrointestinal diseases as the main search terms.

The literature reviews were supplemented with extensive searches of routine data sources in the UK to provide additional information on the burden of gastrointestinal disease in the UK. The main routine data sources used in this chapter were: firstly, the cancer surveillance and registry units in England, Wales, Scotland, and northern Ireland for publications and data on the incidence, mortality, survival, and socioeconomic aspects of gastrointestinal cancers. Secondly, data and reports published by the Office of National Statistics (ONS) and its predecessor, the Office of Population Censuses and Surveys (OPCS), were obtained for information on the causes of gastrointestinal and other mortality in England and Wales. Thirdly, information on hepatitis B and C infections was obtained from publications involving communicable disease surveillance units in the UK.

The main categories of gastrointestinal disease with corresponding ICD‐9 and ICD‐10 codes used are as follows: diseases of the digestive system (ICD‐9 = 520–579; ICD‐10 = K00‐K93), malignant neoplasms of the digestive system (150–159; K15‐K26), benign and other neoplasms of the digestive system (210, 211, 230, 235.2–235.5; D00, D01, D12, D13, D37), intestinal infectious diseases (001–009; A00‐A09), and viral hepatitis (070; B15‐B19).

Some of the main limitations of available data in the UK for investigating the burden of gastrointestinal diseases are: firstly, that incidence and prevalence data are routinely compiled for gastrointestinal cancers and communicable diseases only. Fairly complete incidence data for a few acute gastrointestinal disorders such as acute pancreatitis and acute appendicitis can be traced from hospital admissions, although there have been major concerns about the accuracy of routine hospital data.8,9,10,11 Secondly, different criteria for measuring incidence, case mix variation, and different methods used for age standardising population based incidence and mortality rates can also affect comparability across studies; while case fatality from follow‐up studies is affected by factors such as the length of follow‐up and the inclusion of deaths after discharge with in‐hospital deaths, as well as case mix. Trends in hospital admissions for many gastrointestinal disorders, such as gallstone operations and liver replacements, are also strongly affected by factors such as the availability of hospital facilities, as well as the prevailing clinical practice at the time.

People with other gastrointestinal diseases such as functional disorders are mainly managed in primary care; and so incidence or prevalence data for these diseases can usually only be determined through national primary care surveys, costly databases compiled by pharmaceutical companies, or through intensive local or regional surveys of general practices.

For other gastrointestinal disorders, many people remain undiagnosed. Incidence or prevalence data for some of these diseases, such as gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease, irritable bowel syndrome, and dyspepsia, can often be obtained at a regional level only, through diagnostic questionnaires or interviews; while differences in diagnostic criteria often affect comparability across studies.

For some gastrointestinal disorders, it is not possible to distinguish functional disorders from more serious diseases without the use of special investigation or tests. The growing sophistication of gastrointestinal diagnostic methods has probably resulted in increased diagnosis of milder forms of what would have been traditionally regarded as serious digestive diseases, and caution is therefore required when making comparisons longitudinally over time.12 In other words, increases in reported incidence over time may be attributable to improvements in diagnostic methods rather than real increases.

Routine mortality data are usually available for underlying cause of death only, while patterns of certification of the underlying cause of death vary according to the type of disease or condition. People who die soon after a hospital admission for myocardial infarction, stroke or lung cancer are almost always certified with these diseases as their underlying cause of death. In contrast, the certified underlying causes of death for those who die soon after admission for most gastrointestinal disorders are typically much less likely to be these gastrointestinal diseases.13 Therefore, mortality statistics, based on underlying cause of death often underreport true mortality from gastrointestinal diseases.

In summary, for many gastrointestinal diseases, other than cancers, burden of disease data are often patchy, collected at a local or regional level, have variation in case ascertainment and in comparability between studies and longitudinally over time, and can underreport the true burden of disease. Even for cancers that have been allocated specialist surveillance and registration units, despite improvements over time, there are sometimes differences between cancer registries in case ascertainment and completeness of registrations, so that some degree of caution is required when making comparisons longitudinally and between registry regions.

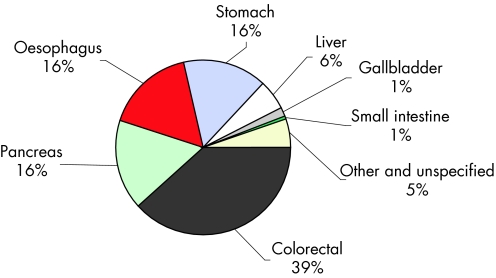

3.1 Spectrum of gastrointestinal disorders

Gastrointestinal disorders cover disease of the alimentary canal (from oesophagus to anus) and its associated organs (liver, gallbladder, and pancreas). They affect a significant proportion of the population. Of the cancers, those of the gastrointestinal tract are among the most common, with colorectal cancer being the second most common cancer in England and Wales as measured by incidence and mortality when both sexes are included.14 It includes very common conditions such as gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease, non‐ulcer dyspepsia, and functional bowel disease, which although a significant proportion of the population probably self treat at some stage in their life, have a huge impact on primary and secondary care. Other common conditions include inflammatory bowel disease, coeliac and diverticular disease. Alcoholic liver disease remains a significant problem but with increasing obesity and lifestyle trends chronic liver disease due to non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatitis C is being increasingly seen. The wide spectrum of disorders requires a range of treatment involving self care, primary care through to secondary care, and highly specialised tertiary referral centres.

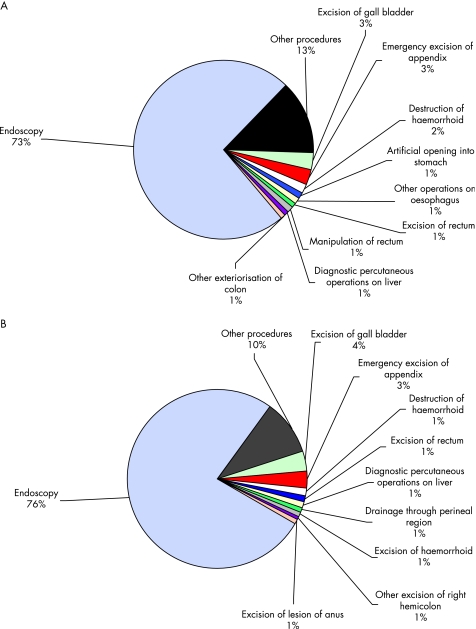

3.2 Incidence of gastrointestinal diseases

Gastrointestinal symptoms and complaints are common among the general population. About one in six admissions to hospital are for a primary diagnosis of gastrointestinal disease, and about one in six of the main surgical procedures in general hospitals are performed on the digestive tract. The following sections outline patterns of incidence and prevalence for some of the main gastrointestinal disorders in anatomical sequence: diseases of the oesophagus, followed by diseases of the stomach and duodenum, the small bowel and colon, the liver, pancreas and gastrointestinal cancers.

Incidence of diseases of the oesophagus

Gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease

Gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease (GORD or GERD when oesophagus is spelt as esophagus) occurs when reflux of stomach acid into the oesophagus is severe or frequent enough to impact the patient's life or damage the oesophagus, or both. It is the most common disorder of the gastrointestinal tract, resulting from failure of the gastro‐oesophageal sphincter. GORD is a chronic condition that, in most cases, returns shortly after discontinuing treatment.

Risk factors for GORD include hiatus hernia, certain foods, heavy alcohol use, smoking, and pregnancy. There is also a strong genetic component in the incidence of GORD: a first degree relative of a patient is four times more likely to be afflicted, while a recent study estimated that 50% of the risk of GORD is genetic.15 Other possible risk factors include concomitant drugs for treatment of hypertension, angina, and arthritis,16 and obesity.17

The risk of GORD increases with age, rising sharply above the age of 40. More than 50% of those afflicted are between the ages of 45 and 64. Incidence varies geographically, it is slightly higher in women than in men, and it is higher among white people than among Asian and Afro‐Caribbean ethnic groups.18,19

In Western countries, 10–40% of the adult population experience heartburn, which is the main symptom of GORD, although estimates vary according to the diagnostic criteria used.18,20,21 In the UK, a recent community based study reported a prevalence of 28.7% for GORD symptoms.22 Subjects with chronic GORD are at risk of developing Barrett's oesophagus (see below). About 10–15% of subjects who undergo endoscopy for GORD evaluation are found to have Barrett's oesophagus,16,23 while other complications of GORD include erosive oesophagitis, ulceration, strictures, and gastrointestinal bleeding.24

Barrett's oesophagus

Severe, longstanding gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease can damage the oesophagus and lead to a condition known as Barrett's oesophagus. This refers to an abnormal change or metaplasia in the cells of the lower end of the oesophagus. Barrett's oesophagus, or columnar‐lined oesophagus (CLO), occurs in about one in 400 of the general population, or about 15% of patients with reflux oesophagitis. It is a rare diagnosis in people aged under 40 years, but its prevalence increases sharply with age and with obesity. It is much more common in white people than in Asian and Afro‐Caribbean ethnic groups,18 among men than women, and among people in higher socioeconomic groups.25

Barrett's oesophagus is a major risk factor,16,23,24 and the only known precursor,26,27,28 for oesophageal adenocarcinoma, although the degree of risk is not very clearly defined as many people with Barrett's oesophagus remain undiagnosed. The diagnosed incidence of Barrett's oesophagus has been increasing sharply over time in the UK,29,30 indicating real increases in its prevalence.

Oesophagitis

Oesophagitis refers to the inflammation of the lower end of the oesophageal lining, arising mainly through the chronic reflux of stomach acid and digestive enzymes into the oesophagus. When the inflammation is severe, oesophageal ulcers may develop. Around 50% of people with GORD also have oesophagitis.31 Other, less common causes of oesophagitis include hiatus hernia, certain fungal infections such as monila and candida, viruses, irradiation, and caustic substances such as lye. The prevalence of oesophagitis increases with age and obesity, and it is also more common in men than in women, and among white people than in Asian and black ethnic groups.32,33

Oesophagitis is present in about 20% of patients at endoscopy,34 although case series from endoscopy units suggest that the diagnosis of oesophagitis is increasing over time. For example, one recent British study reported a diagnostic rate of 32%.35 It is likely that this reflects a true increase in the prevalence of oesophagitis, but the magnitude of the increase may not be entirely accurate owing to effective treatments for the condition, such as the advent of proton pump inhibitors.21

Dyspepsia

Functional gastrointestinal disorders are defined by symptoms in the absence of any structural abnormalities, and affect all areas of the GI tract, ranging from globus (feeling of a lump in the throat), non‐cardiac chest pain, functional dyspepsia in the upper GI tract, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in the lower GI tract. Functional gastrointestinal disorders are characterised by poorly understood abnormalities of gut motility and sensory perception. These and rare motility disorders occur owing to dysfunctional interactions between the brain/central nervous system and the gut/enteric nervous system. Biological triggers underlying functional gastrointestinal disorders are being identified, leading to research aimed at providing effective treatments.

Dyspepsia describes pain or discomfort in the upper abdomen, rather than a defined condition, and it is a chronic, relapsing, and remitting symptom. Causes of dyspepsia include peptic ulcers, acid reflux disease, oesophagitis, anti‐inflammatory drugs, gastritis and duodenitis, hiatus hernia, gastric motility disorder, oesophageal or gastric cancers, although in many cases there is no underlying disease.

Dyspepsia has been defined in different ways by a number of expert groups. For example, the 1988 Working Party classification states that symptoms need to be referable to the upper GI tract, and need to be present for the past four weeks. The less inclusive Rome II criteria later stated that patients need to have predominant pain or discomfort centred in the upper abdomen for at least 12 weeks of the past year, and excluded patients with heartburn or acid reflux as their only symptoms. More recently, the BSG have defined dyspepsia as any group of symptoms that alert doctors to consider diseases of the upper GI tract.

Dyspepsia symptoms typically affect between 20 and 40% of the UK population, depending on the diagnostic criteria used.21 Most recent British studies have used the BSG definition and have typically reported dyspepsia prevalence rates of about 40% (table 3.2.1),36,37,38,39 although lower rates of 26%,40 29%,41 and 12%,42 have also been reported. Prevalence rates in the UK have often been higher than those reported for populations in other Western countries (table 3.2.1).

Table 3.2.1 Prevalence rates (% of population) of dyspepsia, as reported from various regional studies in the UK and in other Western countries.

| Country | Region | Year of study* | Study size | Prevalence (% of population)‡ | Authors and reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK studies: | |||||

| UK | Scotland | 1967 | 1 487 men | 29.0 | Weir RD and Backett BM, 196841 |

| UK | Hampshire | 1988 | 2 066 | 38.0 | Jones RH and Lydeard SE, 198939 |

| UK | England and Scotland ‐ 5 centres | 1989 | 7 428 | 41.0 | Jones RH et al, 199038 |

| UK | 150 Centres | 1994 | 2 112 | 40.3 | Penston JG and Pounder RE, 199636 |

| UK | north of England | 1997 | 3 179 | 25.7 | Kennedy TM et al, 199840 |

| UK | Glasgow | 1998 | 1 611 | 12.0 | Woodward M et al, 199942 |

| UK | Leeds | 1999 | 8 407 | 37.8 | Moayyedi P et al, 200037 |

| Foreign studies: | |||||

| Norway | 1979–1980 | 14 390 | 20 | Johnsen R et al, 198851 | |

| Norway | Sørreisa, | 1987 | 1 802 | 27.5 | Bernersen B et al, 199652 |

| USA | Olmsted County | 1988–1991 | 835 | 25.8 | Talley NJ et al, 199253 |

| Denmark | 1993 | 3 619 | 14–51 | Kay L and Jorgensen T, 199454 | |

| Germany | Essen | 1993 | 180 | 24.4 | Holtmann G et al, 199455 |

| Netherlands | 1994 | 500 | 17 | Schlemper RJ et al, 199556 | |

| Japan | 1994 | 231 | 32 | Schlemper RJ et al, 199556 | |

| USA | Olmsted County | 1996 | 2 200 | 19.8 | Locke GR et al, 199757 |

| Australia | Sydney | 1997 | 592 | 13.2 | Nandurkar et al, 199858 |

| Germany | Ludwigshafen | 1997 | 4 054 | 20.4 | Zober A et al, 199859 |

| Spain | 1998 | 264 | 23.9 | Caballero‐Plasencia AM et al, 199960 | |

| New Zealand | Wellington | 1999 | 817 | 34.2 | Haque M et al, 200061 |

| Sweden | Uppsala | 1999 | 1 422 | 14.5 | Agreus L et al, 200062 |

| Netherlands | Utrecht | 2000 | 500 | 13.8 | Boekema PJ et al, 200163 |

| Iceland | 2000 | 2 000 | 17.8 | Olafsdottir LB et al, 200564 | |

| Australia | New South Wales | 2001 | 2 300 | 11.4–36 | Westbrook JJ and Talley NJ, 200265 |

*The year before the year of publication is given, where the study period was not specified; ‡ranges of prevalence refer to prevalence rates obtained using different criteria for diagnosing dyspepsia.

Dyspepsia also accounts for between 1.2 and 4% of all consultations in primary care in the UK.34,43 Half of these consultations are for functional dyspepsia. Non‐cardiac chest pain may be of gastrointestinal origin but sufferers often persist in the belief that they have heart disease, resulting in severe morbidity. Fifty per cent of patients consulting their GP for chest pain,44 and a similar proportion seen in rapid access chest pain clinics,45 have no cardiac cause of their symptoms. Although mortality in people with functional gastrointestinal disorders is not raised compared with the general population, these disorders have a significant impact on quality of life. For example, two studies reported that 75% of people with non‐cardiac chest pain suffered persistent symptoms and impaired quality of life over periods of 10 years or more; 30–50% never returned to work and were unable to carry out household tasks.44,46

Peptic ulcers have been thought to account for a quarter of all cases of dyspepsia.47 Several British studies from the 1940s to the 1980s reported that 18%,48 26%,41 and 31% 39 of people referred with dyspepsia were found to have peptic ulcers, although more recently this percentage has fallen to around 10–15%.34,39,49,50

Incidence of diseases of the stomach and duodenum

Peptic ulcer

Peptic ulcer is the collective term that includes ulcers of the stomach and the duodenum. About 90–95% of duodenal ulcers and 70–80% of gastric ulcers are caused by the Helicobacter pylori infection. Other risk factors include non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and corticosteroids, increased gastric acid secretion, blood group “O”, smoking, and heavy alcohol use.

Duodenal and gastric ulcer differ in their incidence by age and sex. The incidence of duodenal ulcer peaks at age 45–64 years, and is twice as common in men than in women, whereas gastric ulcer is more common in the elderly and more equally found in men and women.

The incidence of peptic ulcer in the UK increased during the first half of the 20th century. Since the 1950s, however, hospital admission rates for peptic ulcer have fallen among most age groups.66,67,68,69,70 Since the early 1980s, this is largely because of a reduction in recurrent ulcer disease consequent upon the identification and eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection in patients presenting with peptic ulcer. For example, admission rates for duodenal ulcer in Scotland fell by 38% from 157 to 98 per 100 000 population between 1975 and 1990,69 and the prevalence of peptic ulcer in primary care in England and Wales fell by 50% from 1994 to 1998.71 Hospital admissions for perforated peptic ulcer have also fallen over time in the UK; for example, by 26% in Oxford between 1976 and 1982,72 and by 44% in Scotland for perforated duodenal ulcer between 1975 and 1990.69

However, in contrast with this downward trend, hospital admissions for perforated peptic ulcer increased among elderly women in the UK during the 1970s and 1980s,69,73,74 and perforated duodenal but not gastric ulcer, and haemorrhagic peptic ulcers, increased among elderly people in England during the 1990s.75 These increases have been linked to the use of NSAIDs, which have been shown to cause both gastric and duodenal ulceration, including ulcer perforation and haemorrhage.76,77 Patients taking NSAIDs have been reported to be at 4.7 times greater risk of haemorrhagic peptic ulcer, with an increasing risk with age up to 13.2 in people aged over 60.21 Recent small reductions in the incidence of peptic ulcer among elderly women since the mid‐1980s, indicates increased awareness of the side effects of NSAIDs, and more selective prescribing of these drugs.12,70

Helicobacter pylori infection

Helicobacter pylori is a bacterial infection that was discovered in 1982 and is the causal agent in 90–95% of duodenal ulcers and 70–80% of gastric ulcers. It is also linked to other gastrointestinal diseases such as gastritis and dyspepsia,34,49 and it is estimated to be the cause of 73% of all gastric cancers.78,79Helicobacter pylori has been listed as a grade I carcinogen because gastric cancer can occur after Helicobacter pylori gastritis leads to atrophy and metaplasia.80

Risk of infection is strongly linked to social deprivation in childhood, and it is much higher in unsanitary or overcrowded living conditions with no fixed hot water supply.80 It is thought that the crowded living conditions of the expanding cities at the beginning of the industrial revolution led to a decline in hygiene and the spread of the infection early in life.12,81

The prevalence of the Helicobacter pylori infection in the UK has declined in recent decades, as the infection is progressively eradicated from patients presenting with peptic ulcer and also because of a declining incidence as conditions improved over time. Successive birth cohorts have had a lower risk of childhood infection: the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in 20–30 year olds is 10–20%, rising with age to 50–60% in 70 year olds.

Up to half of the world's population is infected with Helicobacter pylori.80 Prevalence varies between about 80% for adults in developing countries, Japan, and South America, around 40% in the UK, and 20% in Scandinavia. Local differences in prevalence exist where there has been substantial immigration from countries with a higher prevalence of infection.

About 15% of people infected with Helicobacter pylori will develop peptic ulcer or gastric cancer as a long term consequence of the infection. Infection in infancy is thought to lead to pangastritis, which predisposes to gastric ulcer and gastric cancer, while infection in later childhood may lead to antral gastritis, which predisposes to duodenal ulcers and duodenitis.82 It has been estimated that one in 35 men and one in 60 women in England and Wales die from a Helicobacter pylori related disease.78 Eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection has been shown to be effective for pylori peptic ulcer disease.49

Gastrointestinal haemorrhage

Gastrointestinal haemorrhage refers to bleeding from the bowel wall or mucosa anywhere along the GI tract. Presentation depends on the location and rate of haemorrhaging and includes melaena from rapid bleeding high in the gastrointestinal tract, iron deficiency anaemia from chronic slow blood loss, or red blood from the colon or ileum.

Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding is the commonest emergency managed by gastroenterologists. About half of all upper gastrointestinal haemorrhages are caused by peptic ulcers and NSAIDs, while other causes include oesophageal or gastric varices, gastric erosions, Mallory‐Weiss tear in the lining of the oesophagus, angiodysplasia, and upper gastrointestinal malignancies. For example, a review of nine European studies from 1973 to 1995 reported that the main causes of haemorrhage were duodenal ulcer (24% of all cases), gastric ulcer (13%), varices (9%), gastritis/erosions (9%), oesophagitis (8%), malignancies (5%), and no diagnosis (14%).83

Lower gastrointestinal haemorrhage accounts for about 20% of all acute gastrointestinal haemorrhages. The most common causes are diverticular disease, inflammatory bowel disease, colonic polyps, ischaemic or infective colitis, gastroenteritis, haemorrhoids, angiodysplasia, and colorectal neoplasms. Most lower gastrointestinal haemorrhages occur in elderly people, and most of these bleeds settle spontaneously and do not require emergency surgery. It is estimated that 20–30% of all gastrointestinal haemorrhages are related to the use of non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs.

The incidence of upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage increases very sharply with age, it is higher in men than in women, and it tends to be highest in areas with high incidence of peptic ulcer—for example, in Scotland and the north of England rather than in southern regions. High hospital admissions rates of upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage have been reported in the west of Scotland (172 per 100 000 in 1992–93),92 Aberdeen (117 in 1991–93),90 and the north east of Scotland (116 in 1967–6886; table 3.2.2).

Table 3.2.2 Hospital admission rates (per 100 000 adult population) for upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage as reported from various regional studies in the UK and in other countries.

| Country | City/region | Study period | No of cases | Hospital admission rate per 100 000 adult population | Authors and reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK studies: | |||||

| UK | Oxford | 1953–1967 | 2149 | 47*† | Schiller KF et al, 197084 |

| UK | Oxford | 1981–1982 | 125 | 56*† | Berry AR et al, 198485 |

| UK | NE Scotland | 1967–1968 | 817 | 116 | Johnston SJ et al, 197386 |

| UK | Newport, Gwent | 1980–1981 | 330 | 52*† | Madden MV and Griffith GH, 198587 |

| UK | Nottingham | 1984–1986 | 1017 | 64*† | Katschinski BD et al, 198988 |

| UK | Bath | 1986–1988 | 430 | 70*† | Holman RA et al, 199089 |

| UK | NE Scotland | 1991–1993 | 1098 | 117 | Masson J et al, 199690 |

| UK | north west Thames | 1991–1993 | NA | 91 | Rockall TA et al, 199591 |

| UK | South west Thames | 1991–1993 | NA | 99 | Rockall TA et al, 199591 |

| UK | West Midlands | 1991–1993 | NA | 102 | Rockall TA et al, 199591 |

| UK | Trent | 1991–1993 | NA | 107 | Rockall TA et al, 199591 |

| UK | West of Scotland | 1992–1993 | 1882 | 172 | Blatchford O et al, 199792 |

| Foreign studies: | |||||

| Sweden | Varberg | 1957–1961 | 283 | 121* | Herner B and Lauritzen G, 196593 |

| Sweden | Sundsvall | 1980–1988 | 978 | 100* | Henriksson AE and Svensson JO, 199194 |

| Spain | Cordoba | 1983–1988 | 3270 | 160* | Mino Fugarolas G et al, 199295 |

| Denmark | Odense | 1990–1992 | 183 | 88 | Hallas J et al, 199596 |

| USA | San Diego | 1991–1994 | 258 | 102* | Longstreth GF, 199597 |

| Saudi Arabia | Abha | 1991–1993 | 240 | 31 | Ahmed ME et al, 199798 |

| Finland | Central province | 1992–1994 | 298 | 68 | Soplepmann J et al, 199799 |

| Estonia | Tartu county | 1992–1994 | 270 | 99 | Soplepmann J et al, 199799 |

| Netherlands | Amsterdam | 1993–1994 | 951 | 45 | Vreeburg EM et al, 199783 |

| Crete | Heraklion | 1998–1999 | 353 | 160 | Paspatis GA et al, 2000100 |

| Italy and Spain | Multicentre | 1998–2001 | 2813 | 40 | Laporte JR et al, 2004101 |

*Admission rates are expressed per 100 000 general population, instead of the usual 100 000 adult population for upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage, and therefore underreport incidence in comparison with the other studies; †admission rates are calculated from the cited number of cases and total populations served by the hospital(s).

A study of four health regions in the south of England and the Midlands reported an overall hospital admission rate of 103 per 100 000; which varied between 91 for north west Thames and 107 for Trent.91 However, lower hospitalised incidence rates of 45–70 per 100 000 were reported from earlier studies particularly in relatively affluent studies such as Bath and Oxford from the 1950s to the 1980s.84,85,88,89 With an ageing UK population, incidence is likely to continue to rise.91

Incidence rates of upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in the UK are often higher than those reported in other recent studies in Europe and elsewhere. These include studies in Central Finland,99 the Netherlands,83 Saudi Arabia,98 Estonia,99 and a multicentre study in Spain and Italy. None the less, high incidence rates of 160 per 100 000 have been reported from studies in Crete in the late 1990s,100 and Spain in the 1980s.95

Incidence of diseases of the small bowel and colon

Inflammatory bowel disease

Ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease are the two main idiopathic types of inflammatory bowel disease. Ulcerative colitis, otherwise known as idiopathic proctocolitis, causes inflammation and ulcers in the colon. Crohn's disease differs from ulcerative colitis because it can occur anywhere along the GI tract and causes inflammation deeper within the intestinal wall. Inflammatory bowel disease usually affects younger people and has a chronic relapsing course that impacts on educational, social, professional, and family life. Along with gastrointestinal cancers and liver disease, inflammatory bowel disease is one of the three most important areas for British gastroenterologists.

A total of about 150 000 people have inflammatory bowel disease in the UK, and a total of approximately 2.2 million across Europe.102 Although there is substantial regional variation (table 3.2.3), the prevalence of Crohn's disease in the UK is currently about 55–140 per 100 000 population, and that of ulcerative colitis is about 160–240 per 100 000, with a combined incidence of about 13 300 new cases diagnosed each year.103

Table 3.2.3 Incidence and prevalence rates (per 100 000 population) for Crohn's disease and for ulcerative colitis, as reported from various regional studies in the UK.

| City/region | Study period | Study sources* | No of cases | Incidence rate per 100 000 population | Prevalence per 100 000 population | Authors and reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crohn's disease: | ||||||

| Cardiff | 1931–90 | SP, HR, Lab | 86 | 2.3 in 1961–65 11.9 in 1981–85 8.6 in 1986–90 | – | Thomas GA et al, 1995121 |

| Cardiff | 1991–95 | SP, HR, Lab | 84 | 5.6 | – | Yapp TR et al, 2000122 |

| Oxford | 1951–60 | SP, HR | 24 | 0.8 | 9 in 1960 | Evans JG and Acheson ED, 1965131 |

| Derby | 1951–85 | HR, Lab | 225 | 0.7 in 1951–55 6.7 in 1981–85 | 85 in 1985 | Fellows IW et al, 1990124 |

| Nottingham | 1958–72 | SP, HR, Lab | 144 | 0.7 in 1958–60 3.6 in 1970–72 | – | Miller DS et al, 1974137 |

| Clydesdale | 1961–70 | HR | 357 | 1.2 in 1961–65 1.9 in 1966–70 | – | Smith IS et al, 1975138 |

| Gloucester | 1966–70 | HR, Lab | 19 | 1.5 | – | Tresadern JC et al, 1973139 |

| North Tees | 1971–77 | HR, Lab | 73 | 5.3 | 35 in 1977 | Devlin HB et al, 1980134 |

| NE Scotland and N Isles of Scotland | 1955–88 | SP, HR, Lab | 1008 | 1.3 in 1955–57 9.8 in 1985–87 | 147 in 1988 | Kyle J, 1992123 |

| Northern Ireland | 1966–81 | HR, Lab | 440 | 1.3 in 1966–73 2.3 in 1974–81 | – | Humphreys WG et al, 1990140 |

| Blackpool | 1968–80 | HR, Lab | 156 | 3.3 in 1971–75 6.1 in 1976–80 | 47 in 1980 | Lee FI and Costello FT, 1985125 |

| Leicestershire | 1972–89 | SP, HR, Lab | 582 | 3.2–4.7 (among Europeans) | – | Jayanthi V et al, 1992126 |

| North Tees | 1985–94 | SP | 200 | 8.3 | 145 in 1994 | Rubin GP et al, 2000136 |

| Trent | 2002 | SP, HR, Lab | 113 | – | 130 in 2002 | Stone MA et al, 2003141 |

| Ulcerative colitis: | ||||||

| Oxford | 1951–60 | SP, HR | 238 | 6.5 | 80 in 1960 | Evans JG and Acheson ED, 1965131 |

| NE Scotland | 1967–76 | SP, HR, Lab | 537 | 11.3 | – | Sinclair TS et al, 1983135 |

| Cardiff | 1968–87 | SP, HR, Lab | 6.4 in 1968–77 6.3 in 1978–87 | – | Srivastava ED et al, 1992133 | |

| North Tees | 1971–77 | HR, Lab | 146 | 15.1 | 99 in 1977 | Devlin HB et al, 1980134 |

| High Wycombe | 1975–84 | HR, Lab | 313 | 7.1 | 84 in 1984 | Jones HW et al, 1988132 |

| North Tees | 1985–94 | SP | 334 | 13.9 | 243 in 1994 | Rubin GP et al, 2000136 |

| Trent | 2002 | SP, HR, Lab | 211 | – | 243 in 2002 | Stone MA et al, 2003141 |

*Study sources: SP, survey of physicians; HR, review of hospital records or admission data; Lab, pathology data.

The causes of ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease are not fully known. Although they are thought to be autoimmune diseases, it is not certain whether autoimmune abnormalities are a cause or result of the diseases. Suggested risk factors include appendectomy, diet, smoking, perinatal and childhood infections, and oral contraceptives,102 while a possible link with measles vaccination has been disputed.104,105 Inflammatory bowel disease predisposes strongly to cancer of the colon,106,107,108,109,110 to venous thromboembolism,111,112,113 and osteoporosis,114,115,116 and it is also associated with coeliac disease,117,118 and primary sclerosing cholangitis.119,120

There is a peak in incidence of inflammatory bowel disease between the ages of 10 and 19 years, and a smaller peak beyond 50 years of age. Women may be at a slightly increased risk of Crohn's disease than men, whereas the risk for ulcerative colitis is the same for men and women.

Studies of Crohn's disease in the UK, and in Europe, have typically reported large increases in incidence over the past 50 years, while others have reported incidence rates that have stabilised after earlier increases (table 3.2.3). There was a sharp increase in the incidence of Crohn's disease in Cardiff from the early 1960s to the early 1980s, before levelling off in the late 1980s,121 and subsequently declining during 1991–95.122 Other sharp increases in incidence of Crohn's disease up to the 1980s have been reported for the north east of Scotland,123 Derby,124 Blackpool,125 and among Europeans in Leicestershire.126

Incidence rates for ulcerative colitis have been more stable over time than those for Crohn's disease,127 although a few recent European studies have reported increasing,128,129 or decreasing rates.130 Several regional British studies have reported incidence rates of about six or 7 per 100 000 (table 3.2.3),131,132,133 although substantially higher rates of 11 to 15 have been reported for northern regions such as north Tees and the north east of Scotland.134,135,136

Although the incidence of inflammatory bowel disease may have shown a tendency to plateau in recent years, large increases in the incidence of paediatric Crohn's disease have continued to be reported in the UK. For example, in Scotland there was a threefold increase in paediatric incidence from 1968 to 1983,142 a further 50% increase from 1981–83 to 1990–92,143 and a 100% increase in north east Scotland from 1980–89 to 1990–99.144 In south Glamorgan there was a 140% increase in the incidence of paediatric disease from 1983–88 to 1989–93,145 although it is now thought to have reached a plateau.146 A recent comparison of two national British birth cohorts indicates that the prevalence of Crohn's disease has increased in younger people, although the prevalence of ulcerative colitis has remained stable.147

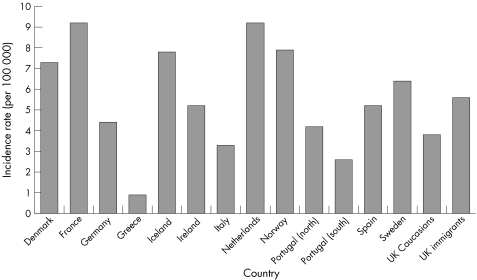

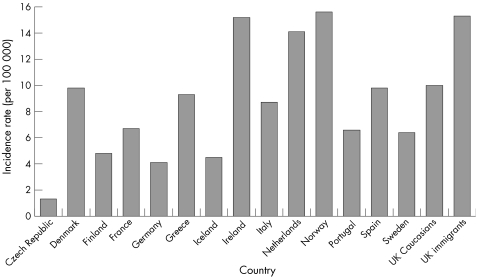

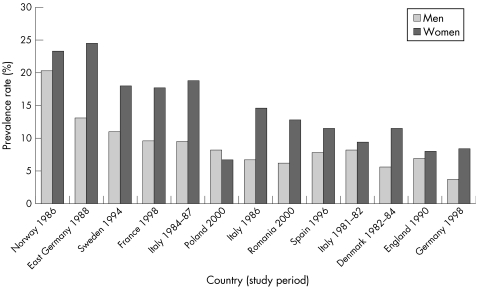

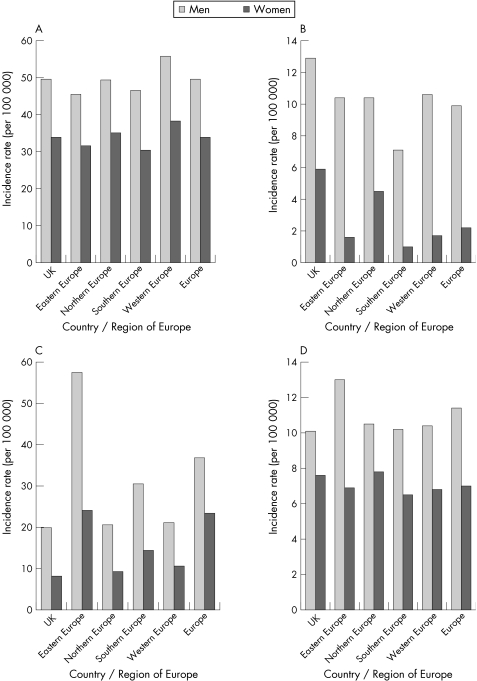

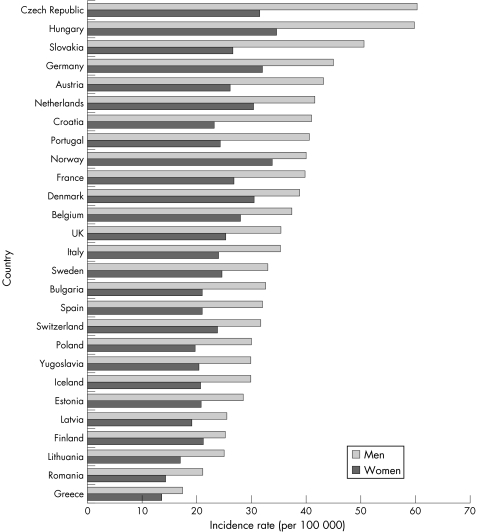

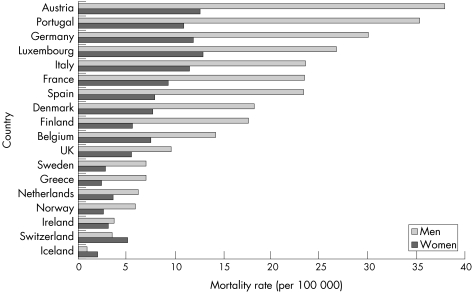

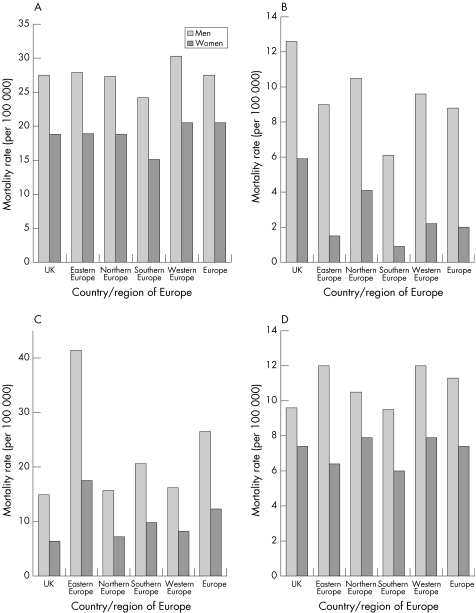

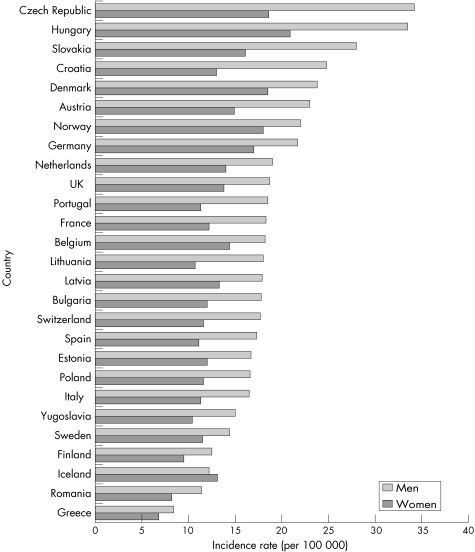

A comparison of incidence rates for Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in the UK, with those reported for various other European countries in 1991–93, is shown in figs 3.2.1 and 3.2.2.148 There is substantial international variation in the incidence of both types of inflammatory bowel disease. For Crohn's disease, incidence tends to be much higher in northern European countries, particularly in Scandinavia and the Netherlands.

Figure 3.2.1 Incidence rate (per 100 000 population) for Crohn's disease in the UK and in other European countries. Source: Shivananda et al, 1996.148

Figure 3.2.2 Incidence rate (per 100 000 population) for ulcerative colitis in the UK and in other European countries. Source: Shivananda et al, 1996.148

The incidence of ulcerative colitis among the UK white population (10.0 per 100 000) is similar to the average of all European countries reported here (9.4), but UK immigrants have a substantially higher rate (figs 3.2.1 and 3.2.2). The incidence of Crohn's disease in the UK white population (3.8) is lower than the European average (5.5), but UK immigrants have similar incidence (5.6).

Irritable bowel syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) refers to longstanding symptoms of abdominal pain, bloating, flatulence, diarrhoea, and/or constipation. It is the most common functional gastrointestinal disorder seen by GPs, and it is the most common disease diagnosed by gastroenterologists. Although not life threatening, IBS may severely impair quality of life, and it usually persists for several years. Like dyspepsia, IBS has been defined in a number of different ways according to different diagnostic criteria, which affects prevalence estimates.

IBS typically affects 10 to 25% of the general UK population. About half of people with IBS consult their GP, and of these about 20% are referred to a consultant.149 Consultation behaviour is often influenced by life events or psychological factors, as well as severity of symptoms. IBS constitutes about 20 to 50% of the outpatient gastroenterology workload.150,151,152

IBS can occur at any age, although it most commonly starts in late teenage years or early adulthood, and it is up to three times more common in women than in men. Although there is no consistent effect of age and ethnicity on symptoms,149 they vary according to which parts of the gut are affected.

Recent community based studies in the UK have reported an IBS prevalence of 10.5% in Birmingham,158 16.7% in Teeside,154 9.5% and 2.5% in Bristol,155,156 and 22% in Hampshire.43 In each of these studies, the prevalence in women was two to four times higher than in men. Prevalence also appears to be increasing in the UK. For example, a comparison of two British national birth cohorts revealed a prevalence rate that had risen from 2.9% in 1988 to 8.3% in 2000 among people aged 30 years.147

The prevalence of IBS ranges in all countries of the world from about 3% to 25%. Although differing diagnostic criteria affect comparability across studies, reported prevalence rates in the UK appear to be comparable with, or perhaps slightly higher than those reported in most other Western countries (table 3.2.4).

Table 3.2.4 Prevalence rates (expressed as percentages) of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) reported from various studies in the UK and in other Western countries.

| Country | City/region | Year of study* | Study size | Prevalence (% of population)† | Authors and reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK studies: | |||||

| UK | Avon | 1979 | 301 | 13.6 | Thompson WG and Heaton KW, 1980157 |

| UK | Hampshire | 1991 | 1 620 | 22.0 | Jones RH and Lydeard SE, 199243 |

| UK | Bristol | 1991 | 1 896 | 9.5 | Heaton KW et al, 1992155 |

| UK | Teeside | 1997 | 3 179 | 16.7 | Kennedy TM and Jones RH, 2000154 |

| UK | Bristol | 1995–7 | 3 111 | 2.5 | Thompson WG et al, 2000156 |

| UK | Birmingham | 2003 | 4 807 | 10.5 | Wilson S et al, 2004158 |

| Other Western countries: | |||||

| USA | 1981 | 789 | 17.1 | Drossman DA et al, 1982159 | |

| USA | 1983 | 566 | 15.0 | Sandler RS et al, 1984160 | |

| Italy | Umbria | 1988 | 533 | 8.5 | Gaburri M et al, 1989161 |

| Japan | 1988–89 | 231 | 25.0 | Schlemper RJ et al, 1993162 | |

| USA | 1990 | 5 430 | 9.4 | Drossman DA et al, 1993163 | |

| The Netherlands | 1991 | 500 | 9.0 | Schlemper RJ et al, 1993162 | |

| USA | Olmsted County | 1992 | 643 | 8.5–20.4 | Saito YA et al, 2000164 |

| Sweden | Osthammar | 1988 | 1 290 | 14.0 | Agreus L et al, 1995165 |

| Denmark | Glostrup | 1993 | 4 581 | 6.6 | Kay L et al, 1994166 |

| Australia | Penrith, Sydney | 1996 | 3 240 | 4.4–13.6 | Boyce PM et al, 2000167 |

| Spain | 2000 | 2 000 | 2.1–12.1 | Mearin F et al, 2001168 | |

| France | 2001 | 15 132 | 4.7 | Dapoigny M et al, 2004169 | |

| Canada | 2001 | 1 149 | 12.1–13.5 | Thompson WG et al, 2002170 | |

| New Zealand | Dunedin | 1998–99 | 980 | 3.3–18.8 | Barbezat G et al, 2002171 |

| Iceland | 2000 | 2 000 | 30.9 | Olafsdottir LB et al, 200564 | |

| USA | Olmsted County | 2002 | 643 | 5.1–27.6 | Saito YA et al, 2003172 |

*Year before the year of publication is given, where the year of study was not specified; †ranges of prevalence refer to prevalence rates obtained using different criteria for diagnosing IBS.

Coeliac disease

Coeliac disease is an inflammatory condition of the small intestine resulting from sensitivity to gluten, a protein in wheat flour, and similar proteins in barley and rye. It develops in genetically predisposed people but can be diagnosed at any age from early childhood to old age. It appears that a “trigger factor” may be required to initiate that response. The trigger might be a viral infection but is usually not known. Removal of wheat gluten (as well as barley and rye) from the diet permits the intestinal mucosa to recover.

Coeliac disease is highly prevalent throughout the world, particularly in countries where wheat forms part of the staple diet, and it is one of the most important conditions managed by gastroenterologists. It is more prevalent in the families of those who are affected: it is estimated that as many as 10% of first degree relatives of patients are also affected.173 Previous underdiagnosis of coeliac disease in primary care reflects an evolving awareness of the diversity in the presentation of coeliac disease.174 Coeliac disease is often associated with other diseases such as ulcerative colitis, biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, osteoporosis, malignant lymphomas, and thyroid disorders,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183 as well as being linked to increased risks of gastrointestinal cancer.182,184,185

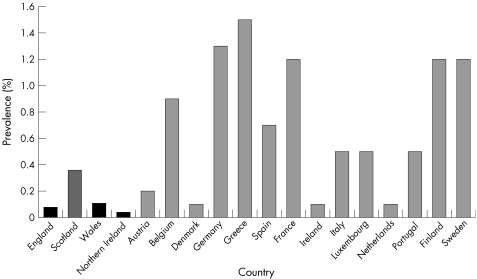

The prevalence of coeliac disease is thought to be about 1% in the UK,186 which appears to be comparable with other countries, globally (table 3.2.5). The prevalence of coeliac disease has increased sharply in the UK in the last couple of decades; largely because of improved diagnosis rates as a result of the introduction of screening tools which can be used in primary care. In the diagnosis of coeliac disease, IgA antibodies to tissue transglutaminase and endomysium show good sensitivity and specificity for coeliac disease; however, it is recommended that the diagnosis is confirmed by small bowel biopsy. Cases of coeliac disease have been described in patients with normal biopsy and positive serology and visa versa. In patients with coeliac disease and IgA deficiency the serology will be negative, in such patients IgG transglutaminase and endomysial antibody should be determined.

Table 3.2.5 Prevalence rates of coeliac disease as reported from various international studies.

| Country | Screening method | Study size | Prevalence rate† | Authors and reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Netherlands | EMA* | 1 440 | 1 in 288 (a) | Schweizer JJ et al, 2004187 |

| Australia | EMA | 3 011 | 1 in 251 (a) | Hovell CJ et al, 2001188 |

| Sweden | TGA EMA | 1 850 | 1 in 205 (a) | Lagerqvist C et al, 2001189 |

| The Netherlands | EMA | 6 127 | 1 in 198 (c) | Csizmadia CG et al, 1999190 |

| Brazil | EMA | 2 371 | 1 in 183 (a) | Pratesi R et al, 2003191 |

| Argentina | AGA EMA | 2 000 | 1 in 167 (a) | Gomez JC et al, 2001192 |

| USA | AGA EMA | 4 126 | 1 in 133 (a) | Fasano A et al, 2003193 |

| Finland | EMA | 1 070 | 1 in 130 (c) | Kolho KL et al, 1998194 |

| Northern Ireland | AGA EMA | 1 823 | 1 in 122 (a) | Johnston SD et al, 1997195 |

| Finland | EMA | 3 654 | 1 in 99 (c) | Maki M et al, 2003196 |

| England | EMA* | 7 550 | 1 in 87 (a) | West J et al, 2003186 |

| Europe (Finland, Germany, Italy, Northern Ireland) | TGA EMA | 29 268 | 1 in 50–1 in 220 (a) 1 in 88–1 in 123 (c) | Mustalahti K et al, 2004197 |

Determination in serum of IgA antibodies against gliadin (AGA), endomysium (EMA), and tissue transglutaminase (TGA).

*Diagnosis not confirmed by small bowel biopsy; †a, adults; c, children.

Diverticular disease

Diverticular of the intestine is a major cause of mortality and morbidity in the UK, mainly among elderly people. It refers to diverticula, or small sacs or pouches that form in the wall of the colon. The most common complication is acute diverticulitis, which occurs when the diverticular become infected, and is sometimes associated with perforation, intestinal obstruction, fistula or abscess formation. Diverticular disease is very common in elderly people, but it is rare in younger age groups and in developing countries. It is thought to be caused mainly by longstanding constipation.198

Risk factors for diverticular disease include low fibre diets and low levels of physical activity, while vegetarians have a lower incidence of diverticular disease.199,200 Increased risks of perforated diverticula have been identified for NSAIDs,201,202,203,204 corticosteroids,205 and opiate analgesics,206 whereas calcium antagonists are thought to have a protective effect.203

Diverticular disease is much more common in the west than in less developed countries.203 For example, a study from the 1960s reported a hospital admission rate of 12.9 per 100 000 in Scotland that was over 60 times higher than those in Fiji, Nigeria, and Singapore.207 Westerners residing in those countries were also substantially more affected than the native populations. In Singapore, for instance, the admission rate among Europeans (5.4 per 100 000) was over 40 times that in the indigenous population.207

In the UK, diverticular disease is much more common among white people than among Asian ethnic groups,208 while incidence increases sharply with age. About 5% of people are affected when in their 40s, and about 50% of people when aged over 80.209 Diverticular disease is more common in men than in women among younger age groups, but it is more common in women among older age groups.203

Because uncomplicated disease is not associated with any particular symptoms, it is often not discovered until postmortem examination, while few studies have examined the progression from uncomplicated to complicated diverticular disease. Lower gastrointestinal haemorrhaging, which occurs in about 15–20% of cases, and infection resulting in peritonitis or abscesses are the most common complications, and are the causes of most admissions to hospital.210 For details of mortality associated with complicated and uncomplicated diverticular disease, see section 3.3.

With an ageing UK population, the incidence of diverticular disease is increasing.211,212 For example, hospital admissions for diverticular disease increased by 16% in men from 20 to 23 per 100 000, and by 12% in women from 29 to 32 per 100 000 in England during the 1990s,212 while emergency surgical admissions for diverticular disease increased significantly in the south west of England from 1974 to 1998.213

Incidence of diseases of the liver

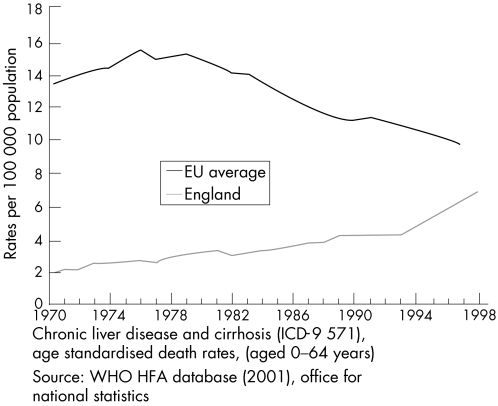

Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis

Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis, traditionally referred to as liver cirrhosis, encompasses a wide range of acute and chronic liver conditions that are caused by a number of different agents. These conditions may lead to cirrhosis, resulting in scarring, injury, and dysfunction of the liver. They include heavy alcohol consumption, hepatitis B or C viral infections, prolonged exposure to certain drugs and toxins, inherited diseases such as haemochromatosis and Wilson's disease, autoimmune liver disease, and chronic liver diseases such as alcoholic fatty liver disease, primary biliary cirrhosis and other chronic diseases of the bile ducts. Around 25% of liver disease is alcohol related, and a similar amount is caused by hepatitis C.214

Alcoholic liver disease

Alcoholic liver disease refers to a handful of liver diseases that are attributed to the effects of alcohol. These include alcoholic cirrhosis, alcoholic fatty liver disease, alcoholic hepatitis, and alcoholic hepatic failure. Because of diagnostic difficulties, there is negligible reporting of population based incidence rates for the different aetiologies; while in most cases routine hospital data fail to distinguish between them. For example, in Scotland in 1999–2000, 71% of hospital discharges for alcoholic liver disease were diagnosed as “unspecified alcoholic liver disease”.215 Since only 15–30% of heavy consumers of alcohol develop advanced alcoholic liver disease,216 genetic and other environmental factors also have an important role.

Earlier, regional British studies reported incidence rates for alcoholic liver disease of 6.5, 14.6, and 2.8 per 100 000 population in respectively, west Birmingham in 1971–76,217 Tayside in 1975–79, and the Scottish Islands of Lewis and Harris in 1977–82.218 The study of west Birmingham also reported an increase in alcoholic liver disease from 2.3 to 9.5 per 100 000 from 1959–61 to 1974–76.217

More recent figures show a 160% rise in hospital admissions for alcoholic liver disease in Scotland between 1996 and 2000,219 while an earlier Scottish study also reported a 160% increase in admissions for liver cirrhosis from 1983 to 1995.220 The large increase in alcoholic liver disease in the UK in recent years has become a major public health concern and has led to the publication of a national alcohol reduction strategy.221

Incidence rates for alcoholic liver disease in the UK are still relatively low compared with those in many other Western countries. For example, a rate of 32 per 100 000 was recently reported for Los Angeles, which varied between 8 per 100 000 for Asian ethnic groups and 61 for Hispanics,216 while the incidence rate in Stockholm County increased from 8 to 24 per 100 000 during the 1970s before falling to 12 per 100 000 by the late 1980s.222

Non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease

Non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), largely unheard of before the 1980s, is another liver disease on the increase, coinciding with the epidemic of obesity in the UK and in other Western countries. NAFLD is the term used to describe a number of liver conditions, including simple steatosis (fat accumulation in liver cells), steatosis with non‐specific inflammation, steatohepatitis (fat accumulation and liver cell injury), and hepatocellular cancer.223 It has also been suggested that cryptogenic cirrhosis may often actually be “burned out” non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis.224

NAFLD is commonly seen in conjunction with type 2 diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and dyslipidaemia, and is regarded as the liver's response to the metabolic syndrome. Although not the only risk factor, obesity is the most prevalent risk factor for NAFLD and is present in 65–90% of cases. Additional risk factors include advanced age and type 2 diabetes, while men and women are equally affected. Although many people with NAFLD remain undiagnosed, it is thought to affect about 20% of the general population in the UK,225 while the obesity epidemic is expected to result in increases in the prevalence of NAFLD in the future.

Non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis

Non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is a major cause of non‐alcoholic liver disease which closely resembles alcoholic liver disease, but occurs in people who consume little or no alcohol. As with alcoholic liver disease, an excess of fat is deposited in the liver, which leads to NASH, inflammation, and scarring, and can progress to cirrhosis. NASH is thought to progress to advanced liver disease in about 15–20% of cases. Most cases are asymptomatic and are diagnosed when abnormal liver blood results are discovered during routine investigations.226

Until relatively recently NASH was thought to be confined largely to middle aged obese women with diabetes. However, it has become increasingly recognised that NASH also occurs in people who are neither obese nor diabetic, and that it may be one of the most common liver diseases in the Western world.226 Unfortunately, figures on the incidence or prevalence of NASH in the UK are conspicuous by their absence.

Hepatitis C

The hepatitis C infection is caused by a virus, which is mainly passed through blood and blood products. Most new cases in western Europe are related to intravenous drug abuse, through using infected needles, and to the increased prevalence of hepatitis C infection in Eastern European immigrants.227 Other less common routes of infection in the UK include unprotected sex, through contaminated skin piercing and tattooing equipment, or from mother to baby.228 As symptoms from acute hepatitis C infection are uncommon, infection is often discovered by chance on routine screening or on testing after the patient's liver function tests have been found to be abnormal.

An estimated 0.5% of the general UK population, or about 300 000 people, are infected with hepatitis C. Since about one fifth of those infected appear to get rid of the virus naturally without treatment,228 the estimated prevalence of hepatitis C infection is about 0.4% or 240 000 people, which is about four times higher than the total number of 60 294 reported hepatitis C diagnoses in the UK up to the end of 2003.229

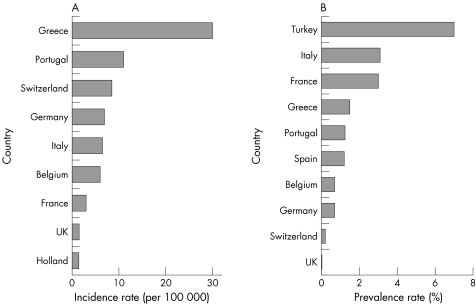

Prevalence rates, based on the total number of reported laboratory diagnoses in the UK, at the end of 2003 were 0.08% for the general population in England, 0.36% in Scotland, 0.11% in Wales, and 0.04% in Northern Ireland.229 These are typically lower than prevalence rates reported for other European countries (fig 3.2.3). There are an estimated five million hepatitis C carriers in western Europe,227 and 170 million in the world.230 Prevalence rates in the UK, and in Europe (1.0% of the population) are lower than in other parts of the world, such as Africa (5.3%), the Eastern Mediterranean (4.6%), and South East Asia (2.2%).230

Figure 3.2.3 Prevalence rates (% of population) for reported hepatitis C infections in England, Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland, and other European countries. Notes: Rates in England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland are based on reported laboratory diagnoses.229 The data source for reported rates in the other European countries is Burroughs and McNamara.227

Greatly increased risks of hepatitis C infection are found among high risk subgroups of the UK population, such as injecting drug users. In Scotland, for example, reported prevalence rates for hepatitis C antibodies among injecting drug users varied between 23% in the Forth Valley and 62% in Greater Glasgow in 1999–2000,229 while a prevalence rate of 44% was reported for injecting drug users in London in 2001.231 Another document reported the highest prevalence in 2001–02 of about 45–50% in London and the north west of England, the lowest prevalence of about 15% in the north east, and a prevalence of 20–35% in other English regions.232

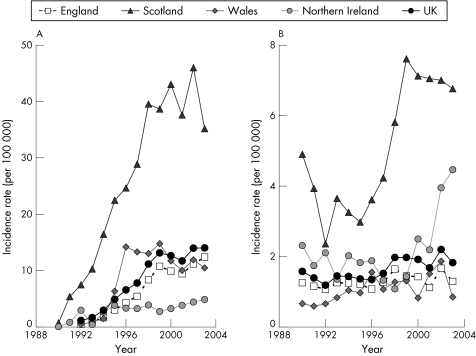

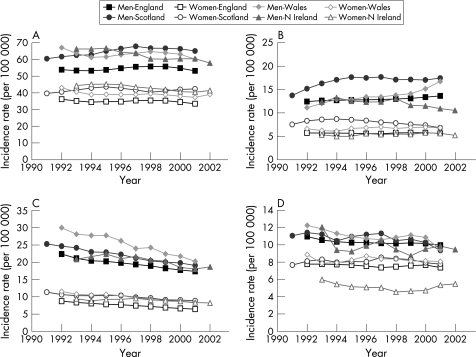

Reported incidence rates for hepatitis C increased alarmingly in the UK during the 1990s, particularly in Scotland (fig 3.2.4A). Based on reported diagnoses, the incidence is currently about 40 per 100 000 in Scotland, 10–15 per 100 000 in England, Wales, and in the UK overall, and around 5 per 100 000 in Northern Ireland.229 In Tayside, prevalence increased from 0.01% to 1.03% of the population from 1988 to 1998.233 The rise of hepatitis C infections has led to the recent publication of national English strategy and action plan documents.228,232

Figure 3.2.4 Trends in incidence rates (per 100 000 population) for reported hepatitis C and B infections in the UK, England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, 1990–2003. (A) Hepatitis C infection; (B) hepatitis B infection. Notes: These incidence rates are based on reported laboratory diagnoses.229

About 40% of people with an acute hepatitis C infection have lifelong chronic infection, which often causes liver cirrhosis or cancer many years after the initial infection. Infected people who consume alcohol have accelerated liver damage, and increased incidence of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular cancer.234,235 Hepatitis C infection invariably causes chronic illness, resulting in a major financial burden on healthcare resources. In western Europe, hepatitis C accounts for 70% of all cases of chronic hepatitis, 40% of all liver cirrhosis, and 60% of all hepatocellular cancer.227 Because of the increasing incidence of hepatitis C, it is estimated that the future burden of hepatitis C health care related to new incidence of cirrhosis will increase by 60% by 2008, and that there will be a fivefold increased need for liver transplantation.214

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B is also caused by a virus; which, in Europe and North America, is mainly passed from person to person by unprotected sex. In the rest of the world it is mainly passed from infected mothers to their children or from child to child.226 Both hepatitis B and chronic hepatitis C are premalignant diseases leading to hepatocellular cancer. However, unlike hepatitis C, vaccination for hepatitis B has proved to be successful in reducing infection rates.227

The prevalence of hepatitis B in the UK is thought to be 0.1% of the general population or approximately 60 000 people,226 which compares with a total of about 13 000 reported diagnoses up to the end of 2003.229 In districts of the UK where there are high levels of immigration, prevalence can be much higher; as high as 2% of the population. In Europe, an estimated one million people are infected each year, although the infection is more common in South East Asia, the Middle and Far East, Africa, and southern Europe.

Compared with hepatitis C, there is a less discernible trend in the incidence of reported hepatitis B diagnoses in the UK in recent years (fig 3.2.4B), although there appears to have been quite sharp increases in Scotland during the late 1990s and in Northern Ireland during the past few years. Reported incidence rates for hepatitis B are about one fifth of those for hepatitis C. Recent World Health Organisation figures also indicate that the incidence and prevalence of hepatitis B in the UK is relatively low compared with many European countries; particularly south European countries such as Turkey and Greece (figs 3.2.5A and 3.2.5B).

Figure 3.2.5 Incidence rates (per 100 000 population) and prevalence rates (% of population) for hepatitis B infection in the UK and in other European countries. (A) Incidence rate; (B) prevalence rate. Source: World Health Organisation.230

Primary biliary cirrhosis

Primary biliary cirrhosis is a disease characterised by inflammatory destruction of the small bile ducts within the liver that eventually leads to cirrhosis of the liver. The cause of primary biliary cirrhosis is unknown, but because of the presence of autoantibodies, it is generally thought to be an autoimmune disease. However, other aetiologies such as infectious agents have not been completely excluded.

About 90% of primary biliary cirrhosis occurs in women, and most commonly between the ages of 40 and 60 years. Incidence appears to be increasing sharply in the UK (table 3.2.6).236 For example, the prevalence of primary biliary cirrhosis in northern England rose sevenfold between 1976 and 1987,237 and by 70% from 1987 to 1994.238

Table 3.2.6 Incidence and prevalence rates (per 100 000 population) for primary biliary cirrhosis as reported from various studies in the UK, and in other countries.

| Country | Region | Study period | Study sources* | No of cases | Incidence per 100 000 population | Prevalence per 100 000 population | Authors and reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK studies: | |||||||

| UK | Sheffield | 1976–79 | SP, Lab | 34 | 0.6 | 5.4 | Triger DR, 1980239 |

| UK | Northern England | 1976–87 | SP, Lab, HR | 347 | 1.9 | 1.8 in 1976 12.9 in 1987 | Myszor M and James OF, 1990237 |

| UK | Dundee | 1975–79 | LHD | 29 | 1.1 | 4.0 | Hislop WS et al, 1982240 |

| UK | NE England | 1972–79 | SP | 117 | 1.0 | 3.7 (rural) 14.4 (urban) | Hamlyn AN et al, 1983241 |

| UK | Glasgow | 1965–80 | Lab, LHD | 373 | 1.1–1.5 | 7.0–9.3 | Goudie BM et al, 1987242 |

| UK | Northern England | 1987–94 | SP, Lab, HR, LHD, ND | 770 | 2.3 in 1987 3.2 in 1994 | 20.2 in 1987 34.5 in 1994 | James OF et al, 1999238 |

| UK | Newcastle | 1987–94 | SP, Lab, HR, LHD, ND | 160 | 2.2 | 18.0 in 1987 | Metcalf JV et al, 1997243 |

| 24.0 in 1994 | |||||||

| UK | Swansea | 1995–96 | Lab, HR, LHD | 67 | – | 20.0 | Kingham JG and Parker DR, 1998244 |

| Foreign studies: | |||||||

| Sweden | Umea | 1972–83 | SP, Lab, HR | 86 | 1.3 | 15.1 | Danielsson A et al, 1990245 |

| Sweden | Malmo | 1973–82 | Lab, HR, ND | 33 | 1.4 | 9.2 in 1982 | Eriksson S and Lindgren S, 1984246 |

| Sweden | Orebro | 1976–83 | Lab | 36 | 1.4 | 12.8 in 1983 | Lofgren J et al, 1985247 |

| Europe | 10 centres | 1981 | SP | 569 | – | 2.3 (0.5–7.5) | Triger DR et al, 1984248 |

| Canada | Ontario | 1986 | SP | 206 | 0.3 | 2.2 | Witt‐Sullivan H et al, 1990249 |

| Spain | Granada | 1976–89 | SP, HR | 25 | 4.1 | 3.6 in 1976 | Caballero Plasencia AM et al, 1991250 |

| 6.2 in 1989 | |||||||

| Australia | Victoria | 1991 | SP, HR | 84 | – | 1.9 | Watson RG et al, 1995251 |

| Norway | Oslo | 1986–95 | HR | 25 | 1.6 | 14.6 in 1995 | Boberg KM et al, 1998252 |

| Estonia | 1973–92 | SP, Lab | 69 | 0.2 | 2.7 | Remmel T et al, 1995253 | |

| USA | Olmsted County | 1976–2000 | Lab, HR | 22 | 1.3 in men 0.5 in women | 6.3 in women | Bambha K et al, 2003254 |

| Alaska | 1984–2000 | Lab, HR | 18 | – | 16 (natives) | Hurlburt KJ et al, 2002255 | |

| Australia | Victoria | 1990–2002 | SP, Lab, HR | 249 | – | 5.1 | Sood S et al, 2004256 |

*Study sources: SP, survey of physicians; Lab, laboratory data on subjects with AMA; HR, review of hospital records or admission data; LHD, liver history data; ND, notification of deaths.

There are large geographical and secular variations in the prevalence of primary biliary cirrhosis world wide (table 3.2.6). The disease appears to be most common in north west Europe, particularly in northern Britain and Scandinavia: some of the highest reported prevalence rates are for northern England (34.5 per 100 000 population)243 and for northern Sweden (15.2).245 These compare with much lower prevalence rates of 1.9 in Victoria, Australia,251 2.2 in Ontario, Canada,249 and 2.7 in Estonia,253 while primary biliary cirrhosis is rarely found in Africa or Asia.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

Primary sclerosing cholangitis is a chronic inflammatory condition that occurs when the bile ducts inside and outside the liver become inflamed and scarred. As the scarring increases, blockage of the ducts leads to damage to the liver. Although the exact cause of primary sclerosing cholangitis is unknown, it is thought that the tissue damage is mediated by the immune system.257

Primary sclerosing cholangitis usually begins between the ages of 30 and 60 and is about twice as common in men as in women.120 Primary sclerosing cholangitis is closely associated with inflammatory bowel disease, particularly ulcerative colitis,257,258 and coeliac disease.177 Around 75–80% of northern European people with primary sclerosing cholangitis have underlying inflammatory bowel disease.120

Primary sclerosing cholangitis usually progresses to biliary cirrhosis, persistent jaundice, and liver failure. For patients with end stage primary sclerosing cholangitis, liver transplantation remains the only effective treatment. Primary sclerosing cholangitis also predisposes to cholangiocarcinoma in up to 30% of cases,120,259 and has been associated with increased risks of cancer of the colon, pancreas, gallbladder, and liver.260 It has also been shown to potentiate the risks of cancer of the colon in people with ulcerative colitis.261,262,263

Although the disease is becoming increasingly common, there is relatively little reported information on incidence or prevalence. Prevalence rates of 12.7 per 100 000 have been reported in south Wales in 2003,264 8.5,252 and 5.6265 per 100 000 population have been reported from Norwegian studies in the mid‐1990s, and 20.9 per 100 000 for Minnesota, USA in 2000.254

Gallstone disease

Gallstones or cholelithiasis occur when bile stored in the gallbladder hardens into pieces of stone‐like material. The two types of gallstones are cholesterol stones that are made primarily of hardened cholesterol, and account for about 80% of gallstones, and pigment stones that are darker and made of bilirubin. It is thought that cholesterol stones form when bile contains too much cholesterol, too much bilirubin, or not enough bile salts, or when the gallbladder does not empty for some other reason. However, the cause of pigment stones is uncertain, although they tend to occur in people who have cirrhosis, biliary tract infections, and hereditary blood disorders, such as sickle cell anaemia, in which too much bilirubin is formed.

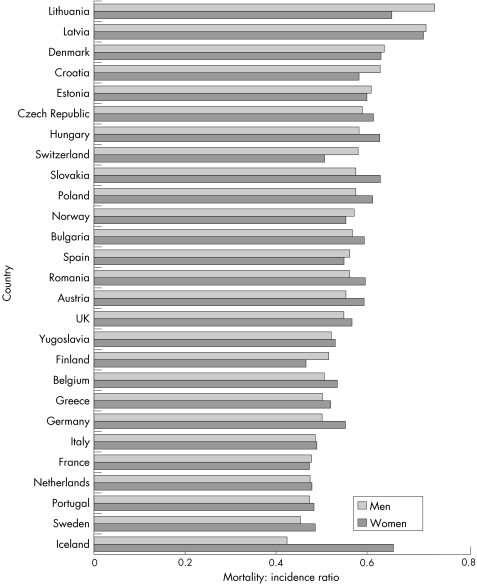

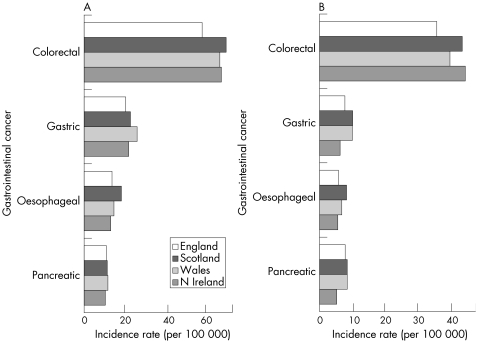

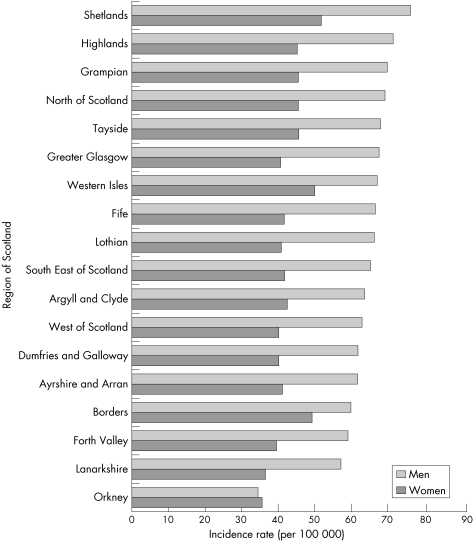

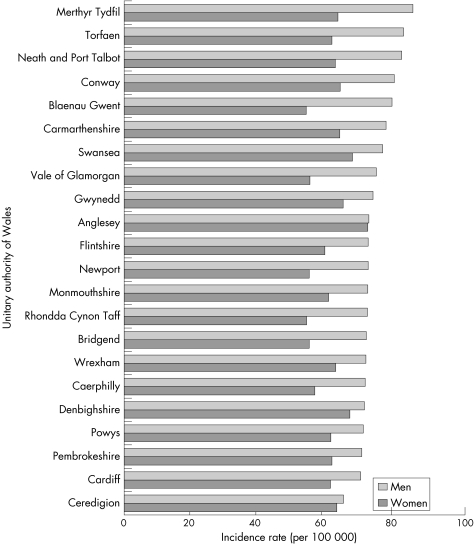

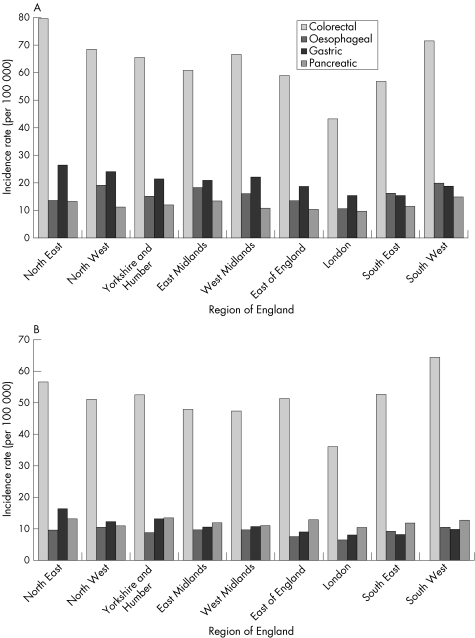

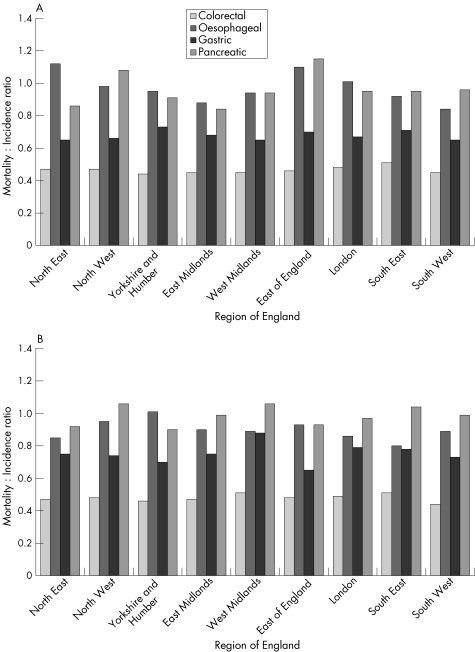

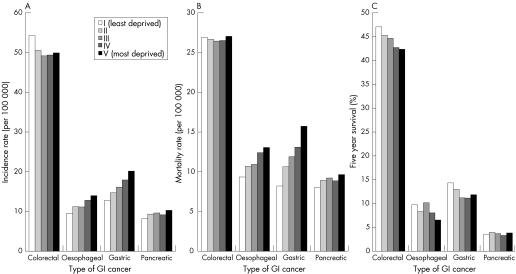

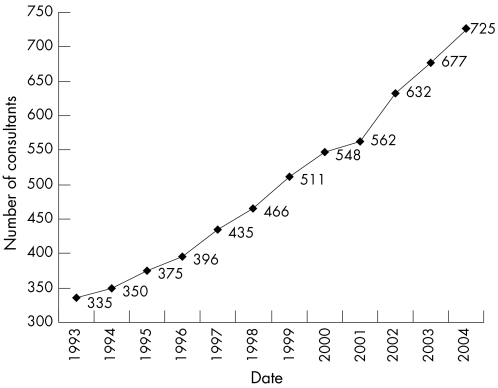

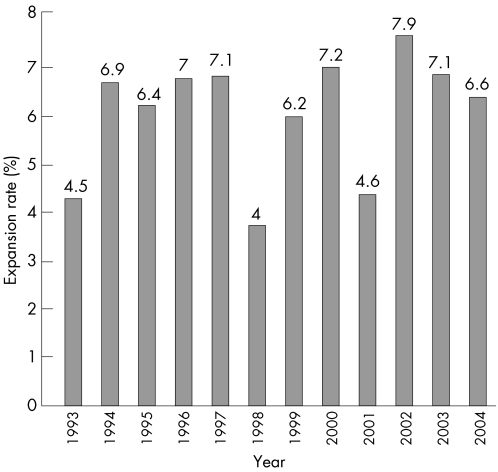

Gallstone disease is the most common abdominal condition for which patients are admitted to hospital in developed countries.266 The incidence of gallstones increases with age and obesity, and it is higher in women than in men. Other risk factors include diabetes, Crohn's disease, cholesterol lowering drugs, gastric bypass surgery, hormone replacement therapy, fasting, and rapid weight loss. Gallstones are very common in the UK among older age groups, with reported prevalence rates of 12% among men, and 22% among women, who were aged over 60 years in an ultrasound survey in Bristol.267