Abstract

Background and hypothesis

The pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (HPAF) cells have a multipotent stem cell potential. It was hypothesised that all‐trans‐retinoic acid (atRA) can induce transdifferentiation of these cells into cells with an endocrine phenotype.

Material and methods

To explore this hypothesis, an in vitro system of cells was established. Some cells were treated with atRA at concentrations of 100 nmol/l (non‐apoptosis‐inducing) and 5 μmol/l (apoptosis‐inducing) and harvested. Cells were examined for cell cycle kinetics, apoptosis (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase assay and p53 protein expression) and immunomorphological features of redifferentiation (MUC1 and DUPAN‐2) and endocrine transdifferentiation (insulin, somatostatin, glucagon, neurone‐specific enolase) by using immunoperoxidase staining methods. Levels of insulin, transforming growth factor (TGF) β2, TGFα and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) were measured by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The vehicle‐treated cells served as a control group.

Results

When compared with untreated cells, cells treated with 100 nmol/l and 5 μmol/l atRA were observed to show (1) decreased proliferative activity (cpm) as indicated by decreased incorporation of thymidine labelled with hydrogen‐3; (2) cell cycle arrest; (3) increased apoptotic activity associated with p53 protein overexpression; (4) upregulated expression of the transdifferentiation and redifferentiation markers; (5) morphological changes indicative of transdifferentiation (increased cell size and appearance of dendrites); (6) decreased production of EGFR; (7) upregulation of TGFα and TGFβ2; and (8) increase in basal and glucose‐induced insulin secretion.

Conclusions

Functional endocrine transdifferentiation can be induced in HPAF lines by atRA. Further investigations are mandated to explore the underlying mechanisms of this transdifferentiation and to explore its in vivo extrapolation.

Several leads point to a possible common stem cell origin for the pancreatic ductal and endocrine cells. Firstly, despite the limited proliferative capacity of islet cells, the formation of new islets from cells associated with the ductal epithelium is achievable. Secondly, cultured mouse pancreatic ductal epithelial cells can produce islet cells.1 Thirdly, islets generated in vitro, derived from ductal stem cells, can reverse diabetes in diabetic mice.2 Finally, the insulin‐positive cells were found in cytokeratin (CK) 19‐positive ductal epithelium in both diabetic and non‐diabetic cells.3 The coincidence of pancreatic cancer and diabetes is well known and may reflect the failure of sustaining enough islet mass resulting from the dedifferentiation of ductal cells.

An active body of proliferating islet precursor cells is required for induction of ductal cancer. The prior destruction of these cells by streptozotocin prevents induction of cancer. The proliferating ductal cells, the islet precursors, are therefore required for transdifferentiation into islet cells and for induction of cancer.4

Retinoids are prototypical differentiation agents that have critical roles in the normal cellular functions and differentiation. As such, they have a fundamental role in the chemoprevention and treatment of epithelial tumours. In carcinoma, retinoids may have a role in chemoprevention by inhibiting the proliferation of cancer cells. This is achieved by different mechanisms such as (1) induction of differentiation or apoptosis, (2) modulation of oncogene expression and (3) modification of cell membrane glycoprotein and glycolipids in a way that alters cell‐to‐cell communication and cell adhesion.5

Transdifferentiation is a change from one differentiated phenotype to another, and involves morphological and functional markers. In this investigation, we hypothesised that retinoic acid can induce transdifferentiation of the pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell lines. We propose that this transdifferentiation represents an escape for the redifferentiated cells from undergoing apoptosis as against an effect mediated by a specific retinoid receptor. To test our hypothesis, on the basis of our previous reports,6,7,8 we examined a possible endocrine transdifferentiation as an integral part of a redifferentiation–apoptosis sequence by using the pleomorphic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (HPAF) cells as a representative model.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

HPAF cells (ATCC, Manassas, Virginia, USA) were established and maintained in a serum‐free and phenol red‐free 1:1 mixture of Dulbecco's modification of Eagle's medium (Gibco, Grand Island, New York, USA) and Ham's F‐12 media (Gibco, Grand Island, New York, USA), containing 2 mM l‐glutamine, 1 mM pyruvate, 2.5 g/l glucose, 10 mM 2‐hydroxyethylpoperazine‐N‐2‐ethane sulphonic acid (HEPES) (Gibco, Grand Island, New York, USA), 100 units/ml penicillin (Gibco, Grand Island, New York, USA) and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco, Grand Island, New York, USA). The cells were incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. All experiments were conducted under subconfluent saturation, included 3–4 replicates and were repeated at least three times.

All‐trans‐retinoic acid (atRA) treatment

The cells were maintained in tissue culture flasks (27 cm2) until they attained confluence. The cells in culture were trypsinised, suspended in serum‐containing medium and seeded in appropriate containers for 24 h and shifted to serum‐free conditions for a further 24 h before treatment. For treatment with atRA (Sigma, St Louis, Missouri, USA), the following steps were taken:

The cells were treated for different periods in 48‐well tissue culture plates (1×103 cells/ml) or in several 75‐cm2 flasks (1×105 cells/m) in the serum‐free medium.

atRA was renewed every third day with fresh media.

All atRA manipulations were carried out under subdued yellow light.

Both non‐apoptosis‐inducing (100 nmol/l) and apoptosis‐inducing (5 μmol/l) concentrations of atRA were used.

Controls (vehicle‐treated cells) were handled similarly. Cells were evaluated for viability, cell cycle arrest, apoptosis and the presence of features of redifferentiation (DUPAN‐2 and MUC1) and neuroendocrine transdifferentiation (insulin, somatostatin, glucagon and neurone‐specific enolase) after atRA treatment. Insulin secretion under basal and glucose‐induced states was tested.

Morphological changes

The cells, in culture, were examined and photographed for morphological changes with a phase‐contrast inverted microscope.

Proliferation and cell cycle assays

The pooled floating and adherent (after trypsinisation) cells were counted (Coulter Counter, Cloutronics, Luton, UK), the new DNA synthesis was assayed (incorporation of thymidine labelled with hydrogen‐3, 25 Ci/mmol/l, Amersham Life Science, Arlington Heights, Illinois, USA) and the cell cycle status was examined using propidium iodide‐stained HPAF cells with DNA index as the marker, as described previously.6,7,8

Detection of apoptosis

Apoptosis was detected using terminal incorporation of fluorescein‐12‐deoxyuridine phosphate by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase into HPAF cells treated for 5 days with vehicle, 100 nM or 5 μM atRA. Laser flow cytometry was used to quantify the green fluorescence of the incorporated fluorescein‐12‐deoxyuridine phosphate against the red fluorescence of propidium iodide. Controls without substrate and with EDTA‐pre‐inhibited enzyme were included.7,8

Immunohistochemical analysis

Immunocytochemical staining was carried out as described previously.9 Sections were mass incubated with mouse monoclonal antibodies for 30 min at room temperature. Antibodies to CK7 and CK19 were obtained from Sigma, to insulin, glucagons, somatostatin, neurone‐specific enolase and p53 were obtained from Biogenex (San Ramon, California, USA) and to DUPAN‐2 and MUC1 were generously provided by Dr M Hollingsworth (Eppely Cancer Center, Omaha, Nebraska, USA). Specimens consisting of normal pancreatic tissues served as positive controls. Alternatively, additional sections running in parallel but with omission of the primary antibody served as negative controls. The average weighted immunoreactivity score was evaluated as for other groups.10

Measurement of transforming growth factor (TGF) α, TGFβ2 and insulin secretion

Secretion of TGFα and TGFβ2 was measured by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in the medium that had been conditioned for 3 days. TGFβ2 was collected in polypropylene siliconised tubes with 0.1% bovine serum albumin and protease inhibitor cocktail to reduce loss. Quantikine immunoassay kits, using two specific polyclonal antibodies and human recombinant protein standards, were used according to the manufacturer's recommendations (DTGA00 for TGFα and DB250 for TGFβ2, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA). TGFα and TGFβ2 kits have lower detection limits of 2.27 and 2.27 pg/ml, respectively. The growth factor content of the conditioned medium was normalised to cell number/day after trypsinising and counting the cells.

For insulin secretion, cells at day 3 of treatment in regular treatment medium (5 mM glucose) were harvested and counted after collecting the conditioned medium, to measure basal insulin secretion. Other simultaneously cultured and treated flasks were shifted at this time into new treatment medium containing 22.5 mM glucose. Two days later, cells were harvested and counted after collecting the conditioned medium as above to measure induced insulin secretion. Insulin content, pg/106 cells/day, in basal and induced conditions was measured by ELISA (catalogue no KAP1251, Biosource Int., Camarillo California, USA, lower detection limit 5 pg/ml). Data are mean (SEM) of three experiments, with three 25‐cm2 flasks in each treatment.

Measurement of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) by ELISA

Cells treated for 3 days and control cells were trypsinised, counted and homogenised for preparation of whole homogenate to determine EGFR expression by using quantitative sandwich ELISA, with specific monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies that do not crossreact with other forms of the receptor, with horseradish peroxidase and o‐phenylenediamine as chromogen and EGFR as standard (0.0–80 fmol/ml, catalogue no QIA08, Oncogene Science, Uniondale, New York, USA). Homogenisation was carried out in 10 mM TRIS–HCl, pH 7.4, containing 1.5 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 0.5 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin and 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulphonylfluoride, mixed 6:1 with the extraction agent provided, centrifuged at 2000×g for 10 min. EGFR content was normalised to the cell number counted in an aliquot before lysis and was expressed as the percentage of control cell content, with control receptor level as 100%.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean (SEM). Different groups were statistically compared using analysis of variance. Data were analysed with the statistical package SPSS V.10 for Windows. Significance was defined as p<0.05.

Results

Growth kinetics of the cells

As compared with the untreated cells, cells treated with atRA (at concentrations of 100 nmol/l and 5 μmol/l) showed the following characteristics:

1. Gradual decrease in 3H‐thymidine incorporation (cpm) in culture (4910 (98.2) v 5305.3 (306.7) v 620.7 (46.6) at 24 h; 4707 (137.4) v 4427.4 (125.5) v 238.3 (17.1) at 48 h; 5277 (52.6) v 3478.7 (79.1) v 15.3 (1.2) at 96 h).

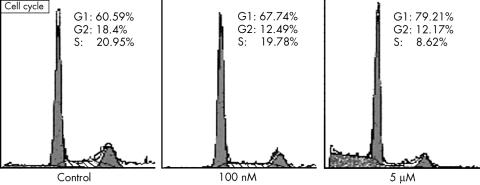

2. Increase in cell cycle arrest (G1 phase: 60.59% (1.891%) v 67.74% (1.711%) v 79.21% (2.045%); G2‐M phase: 18.45% (0.743%) v 12.49% (0.942%) v 12.17% (0.456%); S phase: 20.95% (1.483%) v 19.78% (0.885%) v 8.62% (0.125%)).

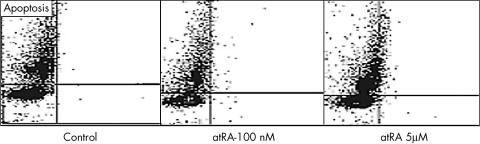

3. Increased apoptotic cell death (per cent apoptosis was 0.3 (0.01) in control, 0.5 (0.112) with 100 nmol/l and 10 (0.214) with 5 μmol/l atRA, p<0.001 comparing 5 μmol/l atRA v each of control or 100 nmol/l).

Table 1, figs 1 and 2 summarise these results.

Table 1 Incorporation of thymidine labelled with hydrogen‐3 (a marker of new DNA synthesis), percentage distribution of cells among phases of cell cycle and per cent apoptosis.

| Control | All‐trans‐retinoic acid | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 nmol/l | 5 μmol/l | ||

| 3H‐thymidine incorporation (cpm) | |||

| At 24 h | 4910 (98.2) | 5305.33 (306.7) NS | 620.67 (46.6)***$$$ |

| At 48 h | 4707 (137.4) | 4427.37 (125.5) NS | 238.33 (17.1)***$$$ |

| At 96 h | 5277 (52.6) | 3478.67 (79.1)*** | 15.33 (1.2)***$$$ |

| Cell cycle phase (%) | |||

| G1 | 60.59 (1.891) | 67.74 (1.711) NS | 79.21 (2.05)**$ |

| G2‐M | 18.45 (0.743) | 12.49 (0.94)** | 12.17 (0.46)** |

| S | 20.95 (1.48) | 19.78 (0.89) NS | 8.62 (0.13)***$$$ |

| Apoptosis (%) | 0.3 (0.01) | 0.5 (0.11) NS | 10 (0.21)***$$$ |

For thymidine incorporation, at given times (24, 48 and 96 h) and at all‐trans‐retinoic acid (atRA) concentrations, treated cells were washed, precipitated with trichloroacetic acie and solubilised in NaOH and β‐counted; results are expressed in cpm.

For analysis of distribution of cells among phases of cell cycle with flow cytometry, ethanol‐fixed cells were stained with propidium iodide and analysed at 24 h of treatment.

For terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase flow cytometry analysis of the percentage of apoptotic cells, the green fluorescence of fluorescein‐12‐deoxyuridine phosphate incorporated against the red fluorescence of propidium iodide was quantified.

Data are mean (SEM) of three experiments.

* or $p<0.05; ** or $$p<0.01; *** or $$$p<0.001, on comparing atRA and control, and the two atRA concentrations, respectively. NS, non‐significant difference.

Figure 1 Early cell cycle arrest as part of the antiproliferative effect of all‐trans‐retinoic acid (atRA). Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells were treated for 24 h with 100 nM or 5 μM atRA, then detached and stained with propidium iodide for cell cycle analysis according to DNA content. The arrest at G1 and reduction in cellular proportion at S phase is shown. A representative study of three experiments conducted is presented.

Figure 2 Induction of late apoptosis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (HPAF) cells. HPAF cells were treated for 5 days with 100 nM or 5 μM all‐trans‐retinoic acid (atRA). Cells were detached, fixed and stained with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase for cell cycle analysis and detection of apoptosis. It shows considerable induction of apoptosis only with 5 μM atRA, unseen with 100 nM atRA. One representative of three experiments conducted is shown.

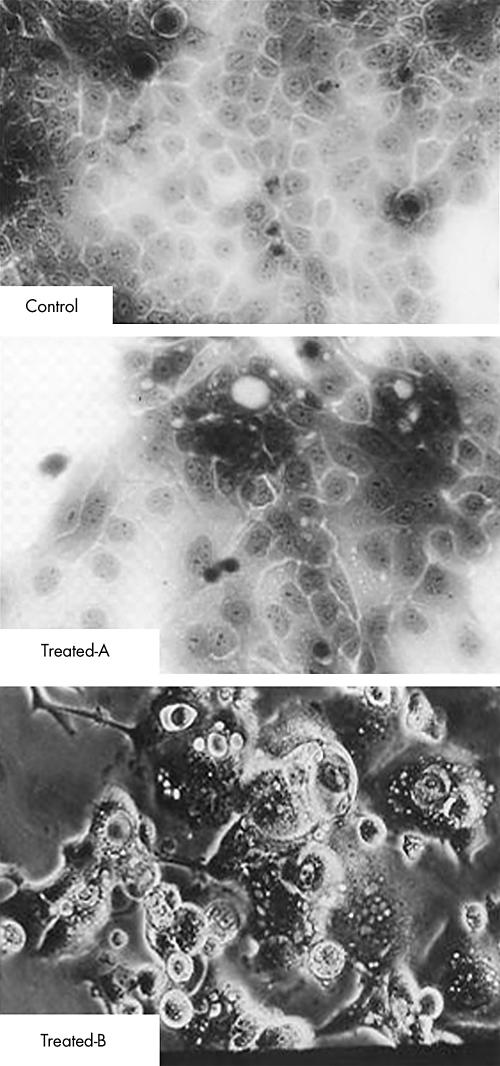

Morphological changes

When compared with the untreated cells, the treated cells showed an increase in cell size, appearance of neurone‐like multiple long‐process cell processes (dendriticity of the cells) and increased cytoplasmic areas (atRA at 5 μmol/l—ie, transdifferentiating concentration) within 72–96 h in culture. These changes were followed by features of cell death (detachment, shrinkage and floating in the culture media; fig 3). Alternatively, atRA at 100 nmol/l concentration induced milder phenotypic changes (not shown).

Figure 3 Induction of morphological changes indicating early redifferentiation and late transdifferentiation in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (HPAF) cells. Compared with control HPAF cells (top), cells treated with 5 μM all‐trans‐retinoic acid, photographed directly while attached, showed expensive changes indicative of redifferentiation (polarisation and secretory activities) at 3 days (centre) and suggestive of transdifferentiation, extensive flattening and process formation followed by float detaching, indicative of apoptosis at 5 days (bottom).

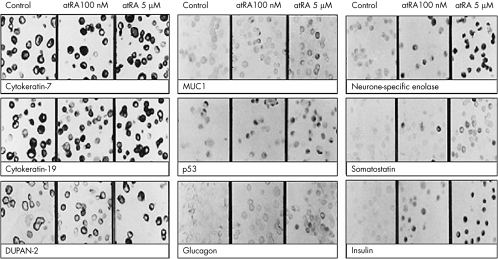

Results of immunohistochemical analysis

The presence of CK7 and CK19 confirmed the epithelial lineage of the cell lines. The staining patterns were cytoplasmic (for insulin), membranous (for somatostatin and enolase) and nuclear (for p53). As compared with the untreated cells, examination of the treated cells (100 nM and 5 μM atRA) showed the following results:

1. Increased apoptotic activity (0.3% v 0.5% v 10%) associated with p53 protein overexpression (0.5 (0.1) v 2.7 (0.3) v 10.6 (0.5), p<0).

2. Upregulated expression of the transdifferentiation (0 (0) v 5.0 (0.3) v 10.6 (0.6) for neurone‐specific enolase; 0 (0) v 2.7 (0.2) v 5.1 (0.4) for somatostatin; 0 (0) v 2.4 (0.2) 10.6 (0.6) for insulin; 0 (0) v 0 (0) v 4.3 (0.2) for glucagon, p<0) and redifferentiation markers (4.6 (0.5) v 5.2 (0.3) v 7.3 (0.5), p<0.05 for DUPAN‐2 and 2.1 (0.3) v 2.3 (0.3) v 4.8 (0.4), p<0.05 for MUC1; table 2, fig 4).

Table 2 Immunohistochemical expression values of the redifferentiation (DUPAN‐2 and MUC1), apoptosis (p53) and transdifferentiation proteins (insulin, somatostatin, glucagon and neuron‐specific enolase, NSE) in the control and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (HPAF) cells treated with atRA.

| Control | atRA concentration | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 nmol/l | 5 μmol/l | |||

| p53 | PP | 0.5 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.1) | 3.7 (0.1)*** |

| SI | 0.5 (0.1) | 1.5 (0.1) | 2.9 (0.1)*** | |

| IRS | 0.5 (0.1) | 2.7 (0.3) | 10.6 (0.5)*** | |

| DUPAN‐2 | PP | 2.5 (0.2) | 2.7 (0.1) | 2.5 (0.1) NS |

| SI | 1.8 (0.1) | 1.9 (0.1) | 2.8 (0.1)* | |

| IRS | 4.6 (0.5) | 5.2 (0.3) | 7.3 (0.5)* | |

| MUC1 | PP | 2.5 (0.1) | 2.5 (0.1) | 2.5 (0.1) NS |

| SI | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | 1.9 (0.1)* | |

| IRS | 2.1 (0.3) | 2.3 (0.3) | 4.8 (0.4)* | |

| NSE | PP | 0 (0) | 1.7 (0.1) | 3.7 (0.1)*** |

| SI | 0 (0) | 3.0 (0) | 2.9 (0.1)*** | |

| IRS | 0 (0) | 5.0 (0.3) | 10.6 (0.6)*** | |

| Insulin | PP | 0 (0) | 1.2 (0.1) | 3.7 (0.1)*** |

| SI | 0 (0) | 2.0 (0) | 2.9 (0.1)*** | |

| IRS | 0 (0) | 2.4 (0.2) | 10.6 (0.6)*** | |

| Somatostatin | PP | 0 (0) | 1.3 (0.1) | 2.7 (0.1)*** |

| SI | 0 (0) | 2.0 (0) | 1.9 (0.1)*** | |

| IRS | 0 (0) | 2.7 (0.2) | 5.1 (0.4)*** | |

| Glucagon | PP | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2.3 (0.1)*** |

| SI | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.9 (0.1)*** | |

| IRS | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4.3±0.2*** | |

Data are mean (SEM) of three experiments.

atRA, all‐trans‐retinoic acid; HPAF, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; NSE, neurone‐specific enolase.

IRS, immunoreactivity score; PP, percentage of positive cells; SI, staining intensity.

*p<0.05; ***p<0.001, on comparing each of the two atRA concentrations with control, and the two atRA concentrations with each other, respectively. NS, non‐significant difference.

Figure 4 Immunostaining for the endocrine transdifferentiation (insulin, glucagon, somatostatin, neurone‐specific enolase), redifferentiation (MUC1 and DUPAN‐2), apoptosis (p53) and ductal epithelial markers (cytokeratins CK7 and CK19) in vehicle‐treated control, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells treated with 100 nM and 5 μM all‐trans‐retinoic acid after 5 days. Table 2 shows the semiquantitative expression of rate of induction of these markers.

Evaluation of growth factors and insulin secretion

When compared with the untreated cells, cells treated with atRA (100 nmol/l and 5 μmol/l) showed the following characteristics:

1. Reduction in EGFR (measured as fmol/l ml, normalised to protein content and expressed as a percentage of control (100% (1.789%) v 81.56% (2.68%) v 11.72% (0.42%), p<0)).

2. Upregulation of TGFα (measured as fmol/106 cells/24 h (12.5 (1.61) v 28.5 (2.74) v 135 (3.35), p<0) and TGFβ2 (measured as pg/106 cells/24 h (67 (2.96) v 614 (5.46) v 2735 (15.19), p<0; table 3)).

Table 3 Secretion of insulin, TGFα and TGFβ2 and expression of EGFR.

| Control | 100 nmol/l | 5 μmol/l | |

|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR, % of control | 100 (1.79) | 81.56 (2.68)** | 11.72 (1.42) ***$$$ |

| TGFα | 12.5 (1.61) | 28.5 (2.74)* | 135 (3.35)***$$$ |

| TGFβ2 | 67 (2.96) | 614 (5.46)*** | 2735 (15.19)***$$$ |

| Insulin, basal v induced | 0 v 0 | 309.81 (2.57)*** v 947.68 (4.16)***§§§ | 815.27 (2.78)***$$$ v 1874.52 (3.18)***$$$§§§ |

atRA, all‐trans‐retinoic acid; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; TGF, transforming growth factor.

For secretion of TGFα and TGFβ2 from control cells and those treated with atRAfor 3 days, conditioned medium was collected in siliconised tubes treated with 0.1% bovine serum albumin and protease inhibitor cocktail, and assayed by specific enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA). Cells were counted and growth factor content was normalised. Results are expressed in fmol/106 cells/24 h (TGFα) or pg/106 cells/24 h (TGFβ2). Data are mean (SEM) of three experiments.

For secretion of insulin, cells at day 3 of treatment in regular treatment medium (5 mM glucose) were harvested and counted after collection of the condition medium. Other flasks were shifted at this time into a new treatment medium containing 22.5 mM glucose. Two days later, cells were harvested and counted after collecting the conditioned medium. Insulin content, pg/106 cells/day in basal and induced conditions, was measured by ELISA. Data are mean (SEM) of three experiments of three 25‐cm2 flasks each.

EGFR content (measured as fmol/l ml) in whole cell homogenate was measured by ELISA and expressed as a percentage of cells treated with vehicles compared with cells treated with 100 nM and 5 μM atRA after 3 days. Data are mean (SEM) of three experiments of three 75‐cm2 flasks.

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; *** or $$$ or §§§p<0.001, on comparing atRA‐treated cells with with control, the two atRA concentrations, and same treatment at basal and glucose‐induced states, respectively.

3. The basal undetectable insulin level was induced to 309.81 (2.57) pg/ml with the non‐apoptotic 100 nM atRA, whereas it reached 947.68 (4.16) pg/ml with 5 µM atRA. At high glucose concentration, insulin level more than doubled, particularly with 100 nM atRA, to 815.27 (2.78) and 1874.52 (3.18) pg/ml with 5 μM atRA.

Discussion

We have previously examined the anticancer effect of natural retinoic acid isomers on 11 human ductal pancreatic cancer cell lines at various degrees of differentiation. Results suggested a redifferentiation–apoptosis sequence in this model. In optimised conditions, controversy with previous reports and discussion of the results was published recently.6,7,8 Initially, cellular flattening, secretory activity and repolarisation were induced in all cell lines that were investigated. A few cells died subsequently by apoptosis, whereas most of the cells exhibited extensive process formation suggestive of endocrine transdifferentiation, which was later followed by apoptosis. These phenotypic changes were accompanied by a complete inhibition of proliferation and cell cycle arrest, where cells were completely viable for a few days. In a subclone of the cell line used, we showed that TGFβ2 immunoneutralisation or retinoid acid receptor α antagonism abrogate the effects of atRA, including apoptosis, suggesting a re‐differentiation‐apoptosis or trans‐differentiation‐apoptosis sequence of events.7,8,11 In HPAF cells, proliferation was completely obliterated within 24 h and cell cycle was arrested at G1, with a marked reduction in S phase cells by treatment with the apoptotic atRA concentration, whereas the subreceptor saturating concentration of atRA caused only a time‐dependent inhibition of proliferation and cell cycle. Phenotypically, there was a differential effect for the two atRA concentrations with extensive changes observed at apoptotic atRA concentrtion, as was observed with 11 cell lines previously tested. These changes were reasoned to be owing to transglutaminase activity, mucin expression, cytoskeletal changes or changes in cell–matrix attachment as reported for retinoids and other models.7,8,12,13,14,15,16,17 The role of cell–matrix interaction is evident for both morphology and for cell differentiation and insulin expression.18 In our model, endocrine transdifferentiation was evident from the strong induction of four major endocrine markers—namely, insulin, glucagon, somatostatin and neurone‐specific enolase—that were not expressed in vehicle‐treated control cells. Moreover, induction of insulin secretion by functional glucose in this model was confirmed, particularly with the subreceptor saturation at non‐apoptotic atRA concentration. This is important in light of early reports of atRA dependency of insulin and glucagon secretion in natural islet cells.12,19 Human pancreatic ductal cells cultured on Matrigel formed three‐dimensional structures of ductal cysts from which insulin‐expressing islet‐like clusters of pancreatic endocrine cells budded. Basal and glucose‐induced insulin secretion from these buds increased as the DNA content increased.18 Tissues from human fetal pancreas early in the second trimester of pregnancy were grafted into people with diabetes, in an attempt that has been unsuccessful so far, to reverse the hyperglycaemic state, because the ability of its β cells to release insulin in response to glucose is either poor or lacking. Exposure to retinoic acid induced insulinogenic response to glucose in these explants when grafted into diabetic nude mice; the explants normalised hyperglycaemia, and oral glucose tolerance tests and glucose‐responsive human C peptide was measurable in the plasma.20 Differentiation of endocrine and duct cells from embryonic pancreatic tissue was stimulated in culture by atRA, whereas it promoted apoptotic cell death of acinar tissue. Through regulation of the (pancreas duodenum homeobox‐l) PDX‐1 gene, atRA‐mediated mesenchymal–epithelial interactions determine the cell fate of epithelial cells during pancreatic organogenesis.21

The cellophane‐wrapping model of monkey pancreas showed that cells immunoreactive for pancreatic hormones bud from the ducts.22 Culture of mouse pancreatic ductal epithelial cells produced functioning islets containing α , β and δ cells, which, when grafted into diabetic NOD mice, could reverse diabetes.1 Islets generated in vitro, whether derived from ductal stem cells of human, porcine or murine origin, exhibit temporal changes in mRNA transcripts for islet‐associated markers, as well as regulated insulin responses after glucose challenge. The implantation of islets into diabetic mice induced neovascularisation of the implant, followed by reversal of insulin‐dependent diabetes.2 Insulin‐positive cells were found in CK19‐positive ductular epithelium in people with and without diabetes. The association of increased fibrosis and β cell neogenesis suggests that chronic exocrine disease may be the stimulus for ductal differentiation of endocrine cells in type 2 diabetes, perhaps as an escape from the apoptotic fate in these conditions.23 Non‐occlusive surgical wrapping of the pancreas in rats identified cells positive for both insulin and cytokeratin in or along the epithelial cell lining of the ductal structures and in the centroacinar cells. PDX‐1‐positive cells were observed in the exocrine area only after wrapping. Double staining also showed that cells positive for PDX‐1 but negative for insulin were present in the exocrine area 1 day after wrapping. Cells positive for both PDX‐1 and insulin developed 3 days later.24 In patients with autoimmune chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic ductal cells containing insulin expressed islet duodenum homeobox‐l/PDX‐l. In transgenic adult mice whose pancreas produced interferon γ, interleukin 6 or tumour necrosis factor α, ductal cells expressed insulin and insulin promoter factor‐1/PDX‐1/islet duodenum homeobox‐1, suggesting that cytokines have a crucial role in the expression of insulin promoter factor‐1/PDX‐1/islet duodenum homeobox‐1 in ductal cells in patients with such disease.25

In the partial pancreatectomy/streptozotocin model of regeneration, islet regeneration is not dependent on the existing β cell mass. Glucagon‐positive cells appear early in the development of the new lobules, then insulin‐positive cells appear as new islets, as small aggregates of cells and as single cells in ductules. Moreover, relatively β cell‐specific genes such as GLUT‐2, the homeodomain transcription factor PDX‐1 and glutamate decarboxylase are expressed in the ductal epithelium of the developing embryo.26 After partial pancreatectomy in rat, regeneration of endocrine cells started immediately and included the proliferation of pre‐existing islet cells and neogenesis of endocrine cells from epithelial cells of the most peripheral duct. Glucagon cells were the first endocrine cells differentiated, some of which were transformed to insulin cells by a mechanism of non‐replication. These results indicate that endocrine stem cells exist among the intercalated ductal or centroacinar cells, and these special regions should be used in transplantation for the successful treatment of diabetes.27 In the partial duct obstruction model of the adult hamster, cells that are positive for glucagon and insulin mRNA appeared within intralobular ducts as early as 6 and 8 days, respectively. Their peptides appeared in these cells at around 8 and 10 days, respectively, as cells migrated from the duct wall.28

The different regeneration models suggested involvement of paracrine or autocrine pathways, and of TGFα and TGFβ pathways in particular. Our results showed the ability of atRA to reduce EGFR expression and increase TGFβ2 secretion and, in particular, to induce extensive secretion of TGFα; all of which were previously responsible for control of ductal epithelium proliferation and differentiation into endocrine and exocrine cell types.26,28 This was particularly distinct with the higher level of atRA. Previously, by using cultured human ductal cells we showed that, during the course of the culture, cells gradually lost the expression of carbonic anhydrase II, secretin receptors, DUPAN‐2 and cancer antigen 19‐9 and assumed an undifferentiated phenotype, with the upregulation of TGFα and EGFR, an increase in the expression of Ki‐67, and cell surface changes as an increased binding to Phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin and tomato lectin.29 On the contrary, islet cells seem to transdifferentiate to exocrine cells and undifferentiated cells expressing neurone‐specific enolase, chromogranin A, laminin, vimentin, CK7 and CK19, α‐1‐antitrypsin, TGFα and EGFR, which may be considered to be pancreatic precursor (stem) cells.9,30

In the partial pancreatic duct ligation mouse model, it was shown that β cells or endocrine precursors are localised among duct lining cells. Induction of several transcription factors and differentiation or growth factors associated with islet cells, including insulin growth factor‐1, activin A, TGFβ1, β cellulin, heparin‐binding epidermal growth factor‐like growth factor and TGFα may have important roles during β cell neogenesis.31 Various hormones and growth factors—including TGFα, TGFβ, insulin growth factor‐I, gastrin, epidermal growth factor and hepatocyte growth factor scatter factor—affect proliferation of ductal epithelium and its differentiation into endocrine and exocrine cell types.32,33,34,35 Also, a dominant‐negative mutant of TGFβ type II receptor in transgenic mice showed an essential role for TGFβ in regulation of growth and differentiation of the exocrine pancreas.34 As EGFR is downregulated and TGFβ receptors are inactivated in pancreatic cancer, these growth factors may be working in a paracrine manner during the process of transdifferentiation. Embryologically, ductal progenitor cells express various proteins that are relatively specific to the β cells, such as GLUT‐2, PDX‐1 and glutamate decarboxylase.36

HPAF cells expressed p53 during exponential growth in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm, which was decreased at confluence and increased by hydroxy urea treatment.37 Similarly, our results showed a marked increase in basal p53 expression, particularly with the apoptotic concentrations of atRA. This could be a mechanistic effector in our endocrine transdifferentiation simulating PANC‐1 cells on transfection with wild‐type p53 reported previously. Stable expression of wild‐type p53 in PANC‐1 cells with mutant p53 caused upregulation of the p21/WAF1 gene, and G1 growth arrest and apoptosis in most of the cells. A subpopulation of the transfectants, however, survived this apoptotic fate and exhibited a neuroendocrine‐like phenotype with extensive branch‐like processes, and marked cytoplasmic and cytoskeletal immunostaining for τ2, synaptophysin and chromogranin A.15

The basal strong staining for CK7 and CK19 confirmed the ductal origin of HPAF cells and showed their continuous expression even after the observed transdifferentiation. The unchanged expression of cytoskeletal proteins did not help in explaining the observed phenotypic changes. Islet‐specific cytokeratin, not yet investigated, may, however, have been induced. It is established that keratin expression is stable in conditions in which morphogenetic differentiation, such as that in fetal life, or transdifferentiation occurs. Keratins have been used to trace the origin and fate of pancreatic cells. CK19 is suggested to represent a “switch” keratin, characterising cells that are in a flexible state of differentiation. In fetal human pancreas of 12–16 weeks' gestation, all epithelial cells express CK7 and CK19, a characteristic feature of adult ductal cells. Thereafter, a progressive loss in expression of these keratins is observed in the maturating acinar cells and islet cells, with a progressive increase in transient coexpression of insulin and CK19, showing the differentiation of duct‐like pancreatic precursor cells into different types of differentiated cells.9,38

Immunohistochemical analysis showed moderate induction of MUC1, and high DUPAN‐2, another MUC1 epitope. MUC1 expression of normal pancreas is retained by its carcinoma and cell lines.39 Ductal and ductular cells of the normal pancreas expressed a high level of the tumour‐associated glycoprotein DUPAN‐2, with diffuse cytoplasmic and glycocalyx patterns, which was maintained in pancreatic cancer cells; but cellular localisation differed appreciably.40 The membrane mucins, including MUC1, MUC3, MUC4/SMC and epiglycanin, also exist in soluble forms, produced by alternative splicing or proteolysis. MUC1/DUPAN‐2 is a ductal marker that is anchored in the membrane with its full O‐glycan moiety, presenting a large extended conformation predicted to be around 500 nm for its largest allele. This conformation provides antiadhesive properties to MUC1. These properties are directly implicated in the morphogenesis of the epithelial tissues by disturbing the cell–cell or cell–matrix interactions. Perturbations of its glycosylation relevant to numerous pathological situations, however, create new glycosidic epitopes and ligands for the P‐selectins, E‐selectins and intercellular adhesion molecule‐1, which present adhesive properties. MUC1 interacts directly with β catenin through its cytoplasmic tail. The β catenin is important in cell–cell interaction through E‐cadherin. The β catenin also binds adenomatous polyposis coli, an essential partner in the anticancer signal pathway Wingless/Wnt‐1.9,17 Treatment with retinoic acid clearly resulted in cytodifferentiation (including elongated cell processes, increased rough endoplasmic reticulum, intensified immunostaining for the mucin marker M1) in PT45 and PANC‐1 among other cell lines of pancreatic adenocarcinoma.41

Take‐home messages

The pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (HPAF) is a highly aggressive neoplasm with poor prognosis.

The HPAF cells have a multipotent stem cell potential.

All‐trans‐retinoic acid (atRA) can induce transdifferentiation of the HPAF cells into cells with endocrine phenotype.

atRA can induce functional endocrine transdifferentiation in HPAF cell lines.

The underlying mechanisms of this transdifferentiation and its in vivo extrapolation mandate further investigations.

As the clinically achievable subreceptor saturating concentration of atRA was able to strongly modulate all the endocrine markers and the possible mechanistic effectors investigated in the present study, the observed changes are clearly the original receptor‐mediated effects for atRA rather than the apoptotic pressure or extra‐receptor‐mediated effects. These results, unbiased with possible contamination by islet preparations, further support the several evidences already reported for the potential stem cell nature of the pancreatic ductal cells and provide a safe inducer for its endocrine transdifferentiation. Studies are in progress to disclose the transcription‐regulatory mechanisms of the retinoid‐induced transdifferentiation in our model, and the results will need to be reproduced in an in vivo diabetic model. This holds a great promise for combating diabetes mellitus.

Abbreviations

atRA - all‐trans‐retinoic acid

CK - cytokeratin

EGFR - epidermal growth factor receptor

ELISA - enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay

HPAF - pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells

PDX‐1 - pancreas duodenum homeobox‐l

TGF - transforming growth factor

TUNEL - terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Ramiya V K, Maraist M, Arfors K E.et al Reversal of insulin‐dependent diabetes using islets generated in vitro from pancreatic stem cells. Nat Med 20006278–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peck A B, Cornelius J G, Schatz D.et al Generation of islets of Langerhans from adult pancreatic stem cells. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 20029704–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heimberg H, Bouwens L, Heremans Y.et al Adult human pancreatic duct and islet cells exhibit similarities in expression and differences in phosphorylation and complex formation of the homeodomain protein Ipf‐1. Diabetes 200049571–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nonomura A, Kono N, Mizukami Y.et al Duct‐acinar‐islet cell tumor of the pancreas. Ultrastruct Pathol 199216317–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller W H., Jr The emerging role of retinoids and retinoic acid metabolism blocking agents in the treatment of cancer. Cancer 1998831471–1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El‐Metwally T H, Adrian T E. Optimization of treatment conditions for studying the anticancer effects of retinoids using pancreatic adenocarcinoma as a model. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1999257596–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El‐Metwally T H, Hussein M R, Pour P M.et al High concentrations of retinoids induce differentiation and late apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells in vitro. Cancer Biol Ther 20054602–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El‐Metwally T H, Hussein M R, Pour P M.et al Natural retinoids inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells previously reported to be retinoid resistant. Cancer Biol Ther 20054474–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmied B M, Ulrich A, Matsuzaki H.et al Transdifferentiation of human islet cells in a long‐term culture. Pancreas 200123157–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hussein M R, Ismael H H. Alterations of p53, Bcl‐2, and hMSH2 protein expression in the normal breast, benign proliferative breast disease, in situ and infiltrating ductal breast carcinomas in the Upper Egypt. Cancer Biol Ther 20043983–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choudhury A, Singh R K, Moniaux N.et al Retinoic acid‐dependent transforming growth factor‐beta 2‐mediated induction of MUC4 mucin expression in human pancreatic tumor cells follows retinoic acid receptor‐alpha signaling pathway. J Biol Chem 200027533929–33936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chertow B S, Moore M R, Blaner W S.et al Cytoplasmic retinoid‐binding proteins and retinoid effects on insulin release in RINm5F beta‐cells. Diabetes 1989381544–1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen C S, Mrksich M, Huang S.et al Geometric control of cell life and death. Science 19972761425–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosewicz S, Wollbergs K, Von Lampe B.et al Retinoids inhibit adhesion to laminin in human pancreatic carcinoma cells via the alpha 6 beta 1‐integrin receptor. Gastroenterology 1997112532–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lang D, Miknyoczki S J, Huang L.et al Stable reintroduction of wild‐type P53 (MTmp53ts) causes the induction of apoptosis and neuroendocrine‐like differentiation in human ductal pancreatic carcinoma cells. Oncogene 1998161593–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vaccari M, Silingardi P, Argnani A.et al In vitro effects of fenretinide on cell‐matrix interactions. Anticancer Res 2000203059–3066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moniaux N, Escande F, Porchet N.et al Structural organization and classification of the human mucin genes. Front Biosci 20016D1192–D1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonner‐Weir S, Taneja M, Weir G C.et al In vitro cultivation of human islets from expanded ductal tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000977999–8004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blumentrath J, Neye H, Verspohl E J. Effects of retinoids and thiazolidinediones on proliferation, insulin release, insulin mRNA, GLUT 2 transporter protein and mRNA of INS‐1 cells. Cell Biochem Funct 200119159–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tuch B E, Osgerby K J. Maturation of insulinogenic response to glucose in human fetal pancreas with retinoic acid. Horm Metab Res Suppl 199025233–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tulachan S S, Doi R, Kawaguchi Y.et al All‐trans retinoic acid induces differentiation of ducts and endocrine cells by mesenchymal/epithelial interactions in embryonic pancreas. Diabetes 20035276–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolfe‐Coote S, Louw J, Woodroof C.et al Development, differentiation, and regeneration potential of the Vervet monkey endocrine pancreas. Microsc Res Tech 199843322–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones L C, Clark A. beta‐cell neogenesis in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 200150(Suppl 1)S186–S187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hosotani R, Ida J, Kogire M.et al Expression of pancreatic duodenal hoemobox‐1 in pancreatic islet neogenesis after surgical wrapping in rats. Surgery 2004135297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanaka S, Kobayashi T, Nakanishi K.et al Evidence of primary beta‐cell destruction by T‐cells and beta‐cell differentiation from pancreatic ductal cells in diabetes associated with active autoimmune chronic pancreatitis. Diabetes Care 2001241661–1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Finegood D T, Weir G C, Bonner‐Weir S. Prior streptozotocin treatment does not inhibit pancreas regeneration after 90% pancreatectomy in rats. Am J Physiol 1999276(5 Pt 1)E822–E827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hayashi K Y, Tamaki H, Handa K.et al Differentiation and proliferation of endocrine cells in the regenerating rat pancreas after 90% pancreatectomy. Arch Histol Cytol 200366163–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenberg L, Vinik A I, Pittenger G L.et al Islet‐cell regeneration in the diabetic hamster pancreas with restoration of normoglycaemia can be induced by a local growth factor(s). Diabetologia 199639256–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ulrich A B, Schmied B M, Matsuzaki H.et al Establishment of human pancreatic ductal cells in a long‐term culture. Pancreas 200021358–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yuan S, Rosenberg L, Paraskevas S.et al Transdifferentiation of human islets to pancreatic ductal cells in collagen matrix culture. Differentiation 19966167–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li M, Miyagawa J, Moriwaki M.et al Analysis of expression profiles of islet‐associated transcription and growth factors during beta‐cell neogenesis from duct cells in partially duct‐ligated mice. Pancreas 200327345–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang T C, Bonner‐Weir S, Oates P S.et al Pancreatic gastrin stimulates islet differentiation of transforming growth factor alpha‐induced ductular precursor cells. J Clin Invest 1993921349–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gu D, Arnush M, Sawyer S P.et al Transgenic mice expressing IFN‐gamma in pancreatic beta‐cells are resistant to streptozotocin‐induced diabetes. Am J Physiol 1995269(Pt 1)E1089–E1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bottinger E P, Jakubczak J L, Roberts I S.et al Expression of a dominant‐negative mutant TGF‐beta type II receptor in transgenic mice reveals essential roles for TGF‐beta in regulation of growth and differentiation in the exocrine pancreas. EMBO J 1997162621–2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang R N, Rehfeld J F, Nielsen F C.et al Expression of gastrin and transforming growth factor‐alpha during duct to islet cell differentiation in the pancreas of duct‐ligated adult rats. Diabetologia 199740887–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pang K, Mukonoweshuro C, Wong G G. Beta cells arise from glucose transporter type 2 (Glut2)‐expressing epithelial cells of the developing rat pancreas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994919559–9563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mogaki M, Hirota M, Chaney W G.et al Comparison of p53 protein expression and cellular localization in human and hamster pancreatic cancer cell lines. Carcinogenesis 1993142589–2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bouwens L. Transdifferentiation versus stem cell hypothesis for the regeneration of islet beta‐cells in the pancreas. Microsc Res Tech 199843332–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vila M R, Balague C, Real F X. Cytokeratins and mucins as molecular markers of cell differentiation and neoplastic transformation in the exocrine pancreas. Zentralbl Pathol 1994140225–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takasaki H, Tempero M A, Uchida E.et al Comparative studies on the expression of tumor‐associated glycoprotein (TAG‐72), CA 19–9 and DU‐PAN‐2 in normal, benign and malignant pancreatic tissue. Int J Cancer 198842681–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Egawa N, Maillet B, VanDamme B.et al Differentiation of pancreatic carcinoma induced by retinoic acid or sodium butyrate: a morphological and molecular analysis of four cell lines. Virchows Arch 199642959–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]