Abstract

Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (VSCC) is a biologically and morphologically diverse disease, consisting of human papillomavirus (HPV)-positive and -negative tumors that differ in their morphological phenotypes and associated vulvar mucosal disorders. This study analyzed the frequencies of allelic loss (loss of heterozygosity (LOH)) in HPV-positive and -negative VSCCs to identify potential targets for the study of preinvasive diseases, to determine whether HPV status influenced patterns of LOH, and to determine whether these patterns differed from HPV-positive tumors of another genital site, cervical squamous cell carcinomas (CSCC). DNA extracted from microdissected archival sections of two index tumors, one each HPV negative and positive, was analyzed for LOH at 65 chromosomal loci. Loci scoring positive with either sample were included in an analysis of 14 additional cases that were also typed for HPV. Frequencies of LOH at loci were computed in a panel of HPV-positive and -negative VSCCs. Twenty-nine loci demonstrated LOH on the initial screen and were used to screen the remaining 14 tumors. High frequencies of LOH were identified, some of which were similar to a prior karyotypic study (3p, 5q, 8p, 10q, 15q, 18q, and 22q) and others of which had not previously been described in VSCC (1q, 2q, 8q, 10p, 11p, 11q, 17p, and 21q). With the exception of 5q and 10p, there were no significant associations between frequency of LOH and HPV status in VSCC. LOH at 3p and 11q were frequent in both VSCC and CSCC; however, allelic losses at several sites, including 5q, 8q, 17p, 21q, and 22q, were much more common in VSCC. VSCCs exhibit a broad range of allelic losses irrespective of HPV status, with high frequencies of LOH on certain chromosomal arms. This suggests that despite their differences in pathogenesis, both HPV-positive and -negative VSCCs share similarities in type and range of genetic losses during their evolution. Whether the different frequencies of LOH observed between VSCC and CSCC are real or reflect differences in stage and/or tumor size remains to be determined by further comparisons. The role of these altered genetic loci in the genesis of preinvasive vulvar mucosal lesions merits additional study.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva (VSCC) is an uncommon neoplasm with an incidence of approximately 1.5 per 100,000. VSCC has generated considerable interest in recent years not only by its association with papillomaviruses (HPVs) but because a substantial proportion of these neoplasms appear to arise via a pathway that does not include HPV infection. Supporting the concept that VSCC is a disease with multiple pathogeneses are the observations that HPV-positive tumors are strongly associated with vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (carcinoma in situ), exhibit specific morphological patterns, and correlate positively with sexual activity, multifocal disease, smoking, and antibodies to HPV. 1 This contrasts with HPV-negative tumors, which have a unique keratinizing morphology, frequently co-exist with lichen sclerosis, epithelial hyperplasia, and atypical hyperplasia (differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN)), and lack the patient demographics of a sexually transmitted etiological agent. 1 The strong association between high risk HPV, particularly type 16, and invasive carcinomas implies a pathogenesis for these tumors in which expression of viral oncogenes interacts with somatic mutations to lead to invasive cancer. Presumably, the pathogenesis of HPV-negative tumors requires somatic mutations; however, it is unclear whether the same somatic mutations occur in HPV-dependent and -independent pathways.

A variety of karyotypic abnormalities have been associated with VSCC in general, including those associated with HPVs. Reported karyotypic changes include both losses (3p, 5q, 8p, 10q, 15q, 18q, 19p, 22q, Xp, and others) and gains (3q). 2 Following a report by one group linking HPV16-associated cervical cancers with gains in 3q, others have linked the 3q gains with HPV-positive VSCCs. 3,4 In contrast, HPV-negative tumors have been distinguished by mutations in p53. 5

This study was a survey of a panel of HPV-positive and -negative VSCCs for allelic losses at multiple chromosomal loci. The purpose was threefold: 1) to identify common sites of allelic loss that would be potentially productive targets for analyzing HPV-positive and -negative preinvasive disease, 2) to determine whether frequencies of loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at loci were a function of HPV status, and 3) to determine whether distribution patterns of LOH between VSCC and a prototypical HPV-dependent neoplasm, cervical squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC) were similar. 2,6

Materials and Methods

Case Selection

Cases of VSCC from the files of the Women’s and Perinatal Pathology Division in the Department of Pathology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital were selected. Attention was paid to obtaining a wide spectrum of epithelial morphology, including intraepithelial-like growth patterns (warty or basaloid tumors commonly associated with HPV nucleic acids and VIN), and keratinizing VSCCs (HPV-negative tumors typically associated with lichen sclerosis, hyperplasia, and atypical hyperplasias).

Tissue DNA Isolation

DNA was extracted from archival tissue as previously described. 7,8 Briefly, 6-μm unstained serial sections were oriented and areas of tumor and control (stroma) tissue identified by referring to paired stained sections. Tumor and stroma were separately removed from two to four sections by scraping the lesional or stromal cells with a clean scalpel. Tissues were transferred to an Eppendorf microcentrifuge tube containing digestion buffer and incubated overnight at 62°C. After addition of Chelex (Biorad, Burlingame, CA) the samples were incubated in a waterbath at 100°C for 10 minutes and centrifuged, and the supernatant was transferred to a sterile tube. 7,8

HPV DNA Detection

Cases were analyzed for HPV DNA as previously described using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and restriction fragment polymorphism analysis (RFLP). 7,8 Briefly, 2 to 5 μl of sample DNA was amplified in PCR buffer containing primers designed to amplify a wide range of HPV types (MY09/MY11) based on shared homology in the L1 region. 9 Reactions were conducted in the presence of [α32P]dCTP, and the radioactive PCR products were digested with restriction endonucleases Pst1, RsaI, and HaeIII and resolved on polyacrylamide gels. 10 After autoradiography, HPV type was assigned based on fragment sizes expected for known sequences.

To account for potential loss of the L1 region via viral disruption during genomic integration, samples scoring negative with the L1 consensus primers were analyzed using primers designed to amplify HPV 16/31 and 18 E7 sequences. 8 Using the same strategy as described above, type was assigned after Alu1 digestion.

Analysis of LOH or Microsatellite Instability (MI)

PCR primers flanking tetranucleotide repeat sequences were selected from the Cooperative Human Linkage Center Human Screening Set Version 1/Weber Set 8 and purchased from Research Genetics (Huntsville, AL). To increase the likelihood of identifying microsatellite loci distinguishing HPV-positive from -negative phenotypes, we selected examples for detailed LOH analysis at 66 loci on 22 chromosomes (Table 1) ▶ . Primers scoring positive for LOH in either of two VSCC prototypes were selected for more extensive testing of remaining HPV-positive and -negative VSCCs.

Table 1.

Microsatellite Locus Designation and Corresponding Chromosome

| Locus | C | Locus | C | Locus | C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1S468 | 1p | D6S1027 | 6q | CHLCGATA 136B01 | 14q |

| D1S534 | 1p | CHLCGATA 24F03 | 7p | D15S822 | 15q |

| D1S518 | 1q | D7S1824 | 7q | D15S643 | 15q |

| CHLCGATA 165C07 | 2p | D8S264 | 8p | D17S1308 | 17p |

| D2S1399 | 2q | D8S1132 | 8q | D17S1303 | 17p |

| D2S1384 | 2q | D8S373 | 8q | D17S928 | 17q |

| D3S2387 | 3p | CHLCGATA 62F03 | 9p | CHLAGATA 178F11 | 18p |

| CHLCGATA 164B08 | 3p | D9S938 | 9q | D18S843 | 18p |

| D3S2432 | 3p | D10S1435 | 10p | D18S535 | 18q |

| CHLCGATA 128C02 | 3q | D10S1432 | 10q | D18S858 | 18q |

| D3S1744 | 3q | D10S1237 | 10q | CHLCGATA 7E12 | 18q |

| D3S2427 | 3q | D10S1248 | 10q | D18S844 | 18q |

| D3S2418 | 3q | D11S1999 | 11p | D19S586 | 19p |

| D4S2366 | 4p | D11S2002 | 11q | D19S254 | 19q |

| D4S2639 | 4p | D11S2359 | 11q | D20S470 | 20p |

| D4S2367 | 4q | D12S372 | 12p | D20S481 | 20q |

| D4S1652 | 4q | D12S375 | 12p | D21S1432 | 21p |

| CHLCGATA 145D10 | 5p | D12S395 | 12q | CHLCGATA 129D11 | 21q |

| D5S816 | 5q | D13S787 | 13p | CHLCGATA 188F04 | 21q |

| D5S820 | 5q | D13S285 | 13q | D21S1446 | 21q |

| D5S408 | 5q | D14S742 | 14p | D22S683 | 22q |

| CHLCGATA F13A1 | 6p | D14S606 | 14q | DXS6810 | Xp |

C, chromosome arm.

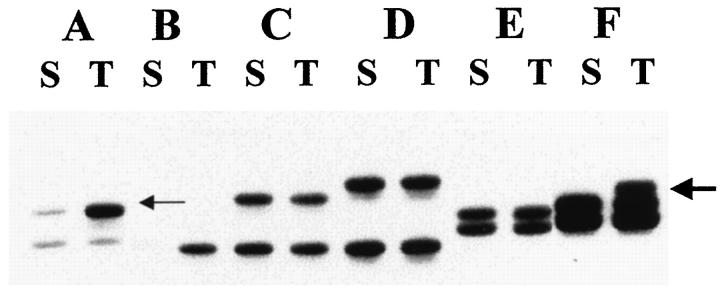

For each locus, the epithelial sample was scored relative to the normal reference stromal genotype as follows: 1) homozygous (uninformative), if a single product was present in control and target tissue, 2) heterozygous, if two products were identified with equal intensity in normal and target tissues, 3) positive for LOH, if bands of unequal intensity were identified in the epithelial but not stromal tissue of heterozygous patients, and 4) positive for MI, if novel products present in the epithelium were not seen in matched normal tissue (Figure 1) ▶ . A conclusive LOH score required a minimum of a 50% reduction in band intensity as visually assessed. The visual method was established by comparison of visual score against a previously quantitated (by densitometry) set of autoradiographs made by amplification of titrated DNA standards 11 (G.M. Mutter, unpublished data). Amplification bias during PCR was insignificant, as evidenced by equivalent intensity of PCR products in normal control tissues.

Figure 1.

Composite autoradiograph depicting heterozygous (informative) loci with two PCR products in all but one sample (B;, uninformative) after amplification of stromal (S) DNA. Loss of heterozygosity is depicted in sample A by the more intense signal in the upper band (small arrow) in the tumor (T) DNA. Microsatellite instability is shown in sample F by the additional band in the PCR product from the tumor DNA (large arrow).

Analysis of Data

Frequencies of allelic loss at individual loci were expressed as the number of cases scoring positive for LOH over the total number of cases informative (heterozygous) at that locus. Differences in frequency of allelic loss were compared between HPV-positive and HPV-negative tumors using the Fisher’s exact test. Differences in frequency were assessed as significant at P values equal to or less than 0.05.

For comparison, frequencies of LOH on chromosome arms using the primers were contrasted with one previously published cytogenetic study of VSCC 2 and one comprehensive study of allelic loss in cervical carcinomas. 6

Results

Comparison between Studies Using Cytogenetics and LOH

The two prototype tumors were tested with a total of 65 markers targeting loci on all chromosomes (Table 1) ▶ . Of these, chromosomal loci targeted by 29 primer pairs demonstrated LOH and were used to screen the remaining 14 tumors (Table 2) ▶ . For all 16 cases, a total of 464 loci were tested; 358 (77.2%) were informative and 106 were either homozygous (89 loci; 19.2%), demonstrated MI (8 loci; 1.7%), or failed to amplify sufficiently to be analyzed (9 loci; 1.9%).

Table 2.

Loss of Heterozygosity in HPV-Positive and -Negative VSCCs

| Locus | C | All cases | HPV positives | HPV negatives | P value§ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOH* | % | LOH | % | LOH | % | |||

| D1S468 | 1p | 4/13 | 30.8 | 2 /6 | 33.3 | 2 /7 | 28.6 | NS |

| D1S518 | 1q | 3/14 | 21.4 | 2 /8 | 25.0 | 1 /6 | 16.7 | NS |

| CHLCGATA165C07 | 2p | 2/12 | 16.7 | 0 /4 | 0.0 | 2 /8 | 25.0 | NS |

| D2S1399 | 2q | 3/12 | 25.0 | 0 /5 | 0.0 | 3 /7 | 42.9 | NS |

| D2S1384 | 2q | 7/14 | 50.0 | 4 /6 | 66.7 | 3 /8 | 37.5 | NS |

| CHLCGATA164B08 | 3p | 6/12 | 50.0 | 3 /6 | 50.0 | 3 /6 | 50.0 | NS |

| CHLCGATA128C02 | 3q‡ | 2/9 | 22.2 | 1 /5 | 20.0 | 1 /4 | 25.0 | NS |

| D4S2366 | 4p | 2/11 | 18.2 | 2 /6 | 33.3 | 0 /5 | 0.0 | NS |

| D5S816 | 5q | 6/14 | 42.9 | 1 /8 | 12.5 | 5 /6 | 83.3 | 0.016 |

| D8S264 | 8p | 7/14 | 50.0 | 2 /6 | 33.3 | 5 /8 | 62.5 | NS |

| D8S1132 | 8q | 8/14 | 57.1 | 3 /6 | 50.0 | 5 /8 | 62.5 | NS |

| D10S1435 | 10p | 4/9 | 44.4 | 1 /6 | 16.7 | 3 /3 | 100.0 | 0.048 |

| D10S1432 | 10q | 4/9 | 44.4 | 1 /4 | 25.0 | 3 /5 | 60.0 | NS |

| D10S1237 | 10q | 2/9 | 22.2 | 1 /5 | 20.0 | 1 /4 | 25.0 | NS |

| D11S1999 | 11p | 3/14 | 21.4 | 3 /7 | 42.9 | 0 /7 | 0.0 | NS |

| D11S2002 | 11q | 4/12 | 33.3 | 2 /8 | 25.0 | 2 /4 | 50.0 | NS |

| D12S372 | 12p | 1/14 | 7.1 | 0 /7 | 0.0 | 1 /7 | 14.3 | NS |

| D14S606 | 14q | 2/12 | 16.7 | 1 /5 | 20.0 | 1 /7 | 14.3 | NS |

| CHLCGATA136B01 | 14q | 3/12 | 25.0 | 2 /6 | 33.3 | 1 /6 | 16.7 | NS |

| D15S822 | 15q | 2/12 | 16.7 | 2 /7 | 28.6 | 0 /5 | 0.0 | NS |

| D15S643 | 15q | 5/14 | 35.7 | 3 /7 | 42.9 | 2 /7 | 28.6 | NS |

| D17S1303 | 17p | 7/12 | 58.3 | 3 /7 | 42.9 | 4 /5 | 80.0 | NS |

| CHLAGATA178F11 | 18p | 2/13 | 15.4 | 1 /6 | 16.7 | 1 /7 | 14.3 | NS |

| D18S535 | 18q | 4/15 | 26.7 | 1 /8 | 12.5 | 3 /7 | 42.9 | NS |

| CHLCGATA129D11 | 21q | 6/13 | 46.2 | 4 /6 | 66.7 | 2 /7 | 28.6 | NS |

| CHLCGATA188F04 | 21q | 6/14 | 42.9 | 4 /7 | 57.1 | 2 /7 | 28.6 | NS |

| D21S1446 | 21q | 7/14 | 50.0 | 4 /8 | 50.0 | 3 /6 | 50.0 | NS |

| D22S683 | 22q | 4/10 | 40.0 | 1 /5 | 20.0 | 3 /5 | 60.0 | NS |

| DXS6810 | Xp | 1/11 | 9.1 | 0 /6 | 0.0 | 1 /5 | 20.0 | NS |

C, chromosomal arm; NS, not significant.

*Expressed as number showing LOH over number of cases informative at the respective locus.

‡The primer CHLCGATA128C02 is located between WC3.13 and WC3.14 contigs on the Radiation Hybrid Map, most probably on 3q.

§Fisher exact test.

Table 2 ▶ displays the findings in the full series of 16 tumors. LOH frequencies were generally high, with a mean of 32% for each locus and a range from 7.1% to 58.3%. Loci scoring positive for LOH in more than 40% of tumors are highlighted, with six (2q, 3p, 8p, 8q, 17p, and 21q) scoring for LOH at more than 50% of informative cases.

Table 3 ▶ compares the frequencies of karyotypic losses observed by Worsham et al 2 with the findings in this study. Close parallels between PCR-ascertained LOH and cytogenetic losses at 3p, 5q, 8p, 10q, and 15q and 22q were observed. Other chromosome arms were identified in this study that were not previously emphasized by Worsham et al, 2 including 1q, 2q, 8q, 10p, 11p, 11q, 17p, and 21q.

Table 3.

Comparison of Studies of Cytogenetic and Allelic Losses in Vulvar Cancer and Allelic Losses in Cervical Cancer

| C | Karyotypic loss, VSCC 2 | Allelic loss, VSCC (this study) | Allelic loss, CXSCC 6 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| 1q | NI | 3/14 | 21.4 | 1 /12 | 8 | |

| 2q | NI | 3/12 | 25.0 | 6 /25 | 24 | |

| 3p | 5 /6 | 83.3 | 6/12 | 50.0 | 8 /20 | 40 |

| 5q | 4 /6 | 66.6 | 6/14 | 42.9 | 2 /25 | 8 |

| 6p | NI | NI* | 12 /38 | 32 | ||

| 8p | 5 /6 | 83.3 | 7/14 | 50.0 | 3 /22 | 14 |

| 8q | NI | 8/14 | 57.1 | 2 /29 | 7 | |

| 10p | NI | 4/9 | 44.4 | 1 /24 | 4 | |

| 10q | 4 /6 | 66.6 | 4/9 | 44.4 | 2 /32 | 6 |

| 11p | NI | 3/14 | 21.4 | 2 /29 | 7 | |

| 11q | NI | 4/12 | 33.3 | 5 /14 | 36 | |

| 15q | 3 /6 | 50 | 5/14 | 35.7 | 1 /20 | 5 |

| 17p | NI | 7/12 | 58.3 | 2 /29 | 7 | |

| 18q | 4 /6 | 66.6 | 4/15 | 26.7 | 4 /21 | 19 |

| 18p | NI | 2/13 | 15.4 | 3 /21 | 14 | |

| 19p | 4 /6 | 66.6 | NI* | 1 /31 | 3 | |

| 21q | NI | 7/14 | 50.0 | 2 /27 | 7 | |

| 22q | 5 /6 | 83.3 | 4/10 | 40.0 | 3 /23 | 13 |

| Xp | 5 /6 | 83.3 | 1/11 | 9.1 | 1 /23 | 4 |

C, chromosome arm; NI, not identified; NI*, negative for LOH in the two index cases and not studied further.

MI was uncommonly identified, in contrast to LOH, scoring positive only eight times at seven loci in six tumors (Table 2) ▶ .

Relationship between HPV Status and Allelic Loss

Fifty percent (8/16) of tumors scored positive for HPV nucleic acids. Of the HPV-positive tumors, six were type 16, one was type 33, and one was a novel HPV type. This predilection for HPV type 16 is consistent with previous reports. Table 2 ▶ depicts the distribution pattern of LOH as a function of HPV status. Altogether, 181 and 177 informative loci were analyzed from HPV-positive and -negative tumors, respectively, with 54 (29.8%) and 63 (35.6%) scoring positive. MI was noted in similar frequencies in HPV-positive and -negative tumors.

Frequencies of allelic loss at individual loci were compared between HPV-positive and -negative tumors and differences analyzed by the Fisher’s exact test. Significant differences in frequency were identified at two loci, D5S816 (5q) and D10S1435 (10p), where a greater proportion of HPV-negative tumors scored positive for LOH at P = 0.016 and 0.047, respectively (Table 2) ▶ . All other loci, including those scoring for LOH in 50% or more tumors, did not exhibit a statistically significant relationship between allelic loss and HPV status.

Relationship between Patterns of Allelic Loss in Vulvar versus Cervical Squamous Tumors

Overall, the frequency of allelic losses in this study of VSSCs was markedly higher than that observed in cervical carcinomas by Rader et al, 6 who observed a mean allelic loss on all chromosomal arms to be 12% in contrast to the 32% seen in this study (Table 3) ▶ . Similar frequencies in allelic loss between the two sites were observed in 2q, 3p, 11q, and 18p. In contrast, higher frequencies of allelic loss were identified in VSSCs at 5q, 8p, 8q, 10p, 10q, 11p, 11q, 17p, 21q, and 22q. These differences in frequency relative to cervical cancers generally held for both HPV-positive and -negative VSSCs.

Discussion

This study has confirmed a high frequency of PCR-ascertained allelic loss associated with VSCC. The distribution of LOH in some loci was consistent with prior karyotypic analysis. 2 Previous publications have found consistent correlation between PCR and karyotypic delineation of chromosomal loss in squamous cell carcinomas of head and neck and squamous and adenocarcinomas of the lung. 8-13 However, in this study, PCR analysis identified a much wider range of allelic loss than in prior karyotypic reports and included LOH at higher than 30% of informative cases on chromosomes 1p, 5q, 10p, 10q, 11q, 15q, 21q (on two different loci), and 22q. Allelic loss in at least 50% of informative cases was seen on chromosomes 2q, 3p, 8p, 8q, 17p, and 21q (on a third locus) (Table 2) ▶ .

The frequency of LOH in VSCCs (32%) was considerably higher than that reported in cervical tumors (12%) by Rader et al. 6 However, it should be emphasized that the strategy for detecting LOH between the two studies varied. Rader et al 6 selected certain primers sets to enrich for loci thought to be important in the pathogenesis of tumors. The current study targeted two prototype tumors with a large number of primers, and subsequent screening was pursued only in loci initially scoring positive (29 loci). Thus, it is not possible to answer with certainty whether VSCCs have a fundamentally different pathogenesis than CSCC by comparison of LOH alone. However, because of the low frequencies of LOH reported in CSCC by Rader et al 6 and others, 12 this hypothesis merits further study. Generally, a wide range of allelic loss has also been reported in tumors in extragenital squamous cell carcinomas, including of the skin, lung, head and neck, and esophagus. 13-20

Similar to studies of the cervix, we found high rates of LOH at 3p and 11q. 6 The locus at 6p, which is also a frequent site of LOH in cervical tumors, was not examined further in our study after scoring negative in the two index cases. Allelic losses on 3p were detected in 50% of our cases. The high frequency of LOH in this chromosomal region was in accordance with previous investigations, suggesting an important role for 3p in carcinogenesis and progression of squamous-epithelium-derived tumors of the head and neck, esophagus, lung, skin, anus, vulva, and cervix. 6,21-28 Losses on 3p were also detected in high frequency (five of six) in the cytogenetic analysis by Worsham et al. 2 Potential sites for novel 3p tumor suppresser genes were mapped in carcinomas of the head and neck and lung as well as endometrium, cervix, and ovary. 16,23,29 However, this chromosomal region has previously been identified as a fragile site (hot spot) for sequence loss or rearrangement. 30 This has prompted speculation that alterations in genes, such as the FHIT (fragile histidine triad) gene, within this region are incidental to rather than a cause of the initiation of squamous neoplasia. 31 In any event, there is no evidence from this study that allelic loss in this region will distinguish HPV-positive from -negative tumors. Similarly, allelic loss at 11q, although present in one-third of informative VSCCs, was not associated with HPV status.

The highest prevalence of LOH in our series of VSSC involved chromosome 17p (58.3%), which is of interest in light of the very low incidence of LOH on 17p in cervical squamous cell carcinomas, and the reported low incidence of p53 mutations in HPV positive VSCCs. 5,6,12,32 Consistent genetic losses on this chromosomal arm have also been described in many solid tumors and in squamous cell carcinomas of the head, neck, lung, esophagus, and skin. 14,17-19 Accordingly, carcinomas of head and neck have shown consistent mutation and/or LOH of p53 (17p13.1) as well as the nearby CHRNB1 locus at 17p12-p11.1. 33,34 One of these studies also indicated 17p12-p11 as a potential site for a tumor suppressor gene. 33 In the present study, LOH on 17p was present in both HPV-positive (3/7) and HPV-negative (4/5) tumors and, like 3p and 11q, failed to discriminate between the two groups.

Other loci of interest included 8p, 8q, 21q, and 22q, all of which scored high for LOH in VSCC in contrast to cervix. Chromosome 21 scored high for LOH by three different markers: CHLCGATA129D11 (46.2%), CHLCGATA188F04 (42.9%), and D21S1446 (50%). LOH on 8q, the second most frequent site containing losses in our study (53.3%) has not been conspicuous in squamous cell carcinomas of any other site except for the cervix, but this may be subject to revision after its study in a wider spectrum of tumors. High prevalence of LOH in our study was found in the short (50.0%) and long (57.1%) arms of chromosome 8. Allelic losses in 8p were described also in squamous cell carcinomas of head and neck and lung and are consistent with previous cytogenetic findings in short-term culture of vulvar carcinoma cells. 2,20,35,36

One objective of this study was to determine whether HPV-positive and -negative VSCCs could be distinguished according to frequencies of chromosome-specific allelic loss. However, with the exception of 5q and 10p, no loci exhibited significant differences in frequency, and only one (5q) demonstrated a P value of less than 0.01. These findings are not compelling, given the likelihood that a random comparison of 29 loci might produce differences at one or two loci that appear significant. Moreover, LOH at 5q was reported in 23% of CSCCs. 12 Further analysis of 5q by three additional primer pairs targeting flanking loci revealed six additional sites of LOH in three HPV-negative and three in two HPV-positive tumors (data not shown). However, although these findings further support the high prevalence of LOH on 5q, determining their relationship to viral status will require additional study.

Another objective of this study was to identify loci with high frequencies of LOH that could serve as targets in the study of precursor lesions and help resolve the timing of these molecular events during the evolution of HPV-positive and -negative vulvar neoplasia. LOH at 3p has been reported to be an early event in cervical and head and neck carcinogenesis, occurring in premalignant lesions. 25,28,37 In a previous study, we showed non-invasive monoclonal squamous lesions of the vulva could have either a VIN or hyperplasia morphology. 38 In a recent study targeting a limited number of chromosomal loci, LOH was identified in some of these intraepithelial lesions, and LOH at one locus, 5q, was shared by VIN and VSCC. 11 Based on the current study, additional loci merit testing in noninvasive vulvar mucosal lesions to determine their role in the pathogenesis of HPV-positive and -negative squamous cell carcinomas at this site.

It should be emphasized that assumptions regarding allelic loss should be tempered by one technical limitation, the inability to completely exclude allelic gain. Studies using comparative genomic hybridization have revealed amplification of several chromosomal loci, either in cervical carcinomas or cell cultures of HPV-immortalized cells. 3,39 When pronounced, asymmetric allelic amplification could produce differences in PCR product intensity, similar to allelic loss. Thus, the nature of any “allelic imbalance” of potential etiologic importance should be verified to determine its influence (by either loss or gain) on tumor phenotype.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Christopher P. Crum, Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA 02115. E-mail: cpcrum@bics.bwh.harvard.edu.

Supported by a grant from the Milton Fund and the Pemberton Fellowship Fund (A.P. Pinto). Dr. Pinto is also a recipient of a Ph.D. fellowship grant from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento em Pesquisa, Brazil.

References

- 1.Crum CP: Carcinoma of the vulva: epidemiology and pathogenesis. Obstet Gynecol 1992, 79:448-454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Worsham MJ, Van Dyke DL, Grenman SE, Hopkins MP, Roberts JA, Gasser KM, Schwartz DR, Carey TE: Consistent chromosome abnormalities in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Genes Chromosomes & Cancer 1991, 3:420-432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heselmeyer K, Schrock E, Manoir S, Blegen H, Shah K, Steinbeck R, Auer G, Ried T: Gain of chromosome 3q defines the transition from severe dysplasia to invasive carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996, 93:479-484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Isaacson C, Kessis T, MacVille M, Baranayai J, Jones R, Kurman R, Shah K: Comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) analysis of primary vulvar carcinomas. Mod Pathol 1997, 10:102A [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee YY, Wilczynski SP, Chumakov A, Chih D, Koeffler HP: Carcinoma of the vulva: HPV and p53 mutations. Oncogene 1994, 9:1655-1659 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rader JS, Kamarasova T, Huettner PC, Li L, Li Y, Gerhard DS: Allelotyping of all chromosomal arms in invasive cervical cancer. Oncogene 1996, 13:2737-2741 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lungu O, Wright TC, Silverstein S: Typing of human papillomaviruses by polymerase chain reaction amplification with L1 consensus primers and RFLP analysis. Mol Cell Probes 1992, 6:145-152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tate JE, Mutter GL, Prasad CJ, Berkowitz R, Goodman H, Crum CP: Analysis of HPV-positive and -negative vulvar carcinomas for alterations in c-myc, Ha-, Ki-, and N-ras genes. Gynecol Oncol 1994, 53:78-83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manos MM, Ting Y, Wright DK, Lewis AJ, Borker TR, Wolinsky SM: Use of polymerase chain reaction amplification for the detection of genital human papillomaviruses. Furth H Greaves H eds. Cancer Cells: Molecular Diagnostics of Human Cancer. 1989, :pp 209-214 Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Cold Spring Harbor, NY, [Google Scholar]

- 10.Genest D, Stein L, Cibas E, Sheets E, Zitz J, Crum CP: A binary (Bethesda) system for classifying cervical cancer precursors: criteria, reproducibility and viral correlates. Hum Pathol 1993, 24:730-736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin M-C, Mutter GL, Trivijisilp P, Boynton KA, Sun D, Crum CP: Patterns of allelic loss (LOH) in vulvar squamous carcinomas and adjacent noninvasive epithelia. Am J Pathol 1998, 152:1313-1318 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Busby-Earle RMC, Steel CM, Bird CC: Cervical carcinoma: low frequency of allele loss at loci implicated in other common malignancies. Br J Cancer 1993, 67:71-75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carey TE, Van Dyke DL, Worsham MJ: Nonrandom chromosome aberrations and clonal populations in head and neck cancer. Anticancer Res 1993, 13:2561-2567 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ah-See KW, Cooke TG, Pickford IR, Soutar D, Balmain A: An allelotype of squamous carcinoma of the head and neck using microsatellite markers. Cancer Res 1994, 54:1617-1621 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakurai M, Tamada J, Maseki N, Kaneko Y, Suzuki T, Notohara K, Shimosato Y: Chromosomal deletions in non-small cell lung carcinomas. Proc Annu Meet Am Assoc Cancer Res 1991, 32:A1176 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petersen I, Bujard M, Cremer T, Dietel M, Ried T: Comparative genomic hybridization reveals multiple DNA gains and losses in non-small cell lung carcinomas. Proc Annu Meet Am Assoc Cancer Res 1995, 36:A3289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lasko D, Cavaenee W, Nordenskjold M: Loss of constitutional heterozygosity in human cancer. Annu Rev Genet 1991, 25:281-314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aoki T, Mori Tdu X, Nisihira T, Matsubara T, Nakamura Y: Allelotype study of esophageal carcinoma. Genes Chromosomes & Cancer 1994, 10:177-182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quinn AG, Sikkink S, Rees JL: Basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas of human skin show distinct patterns of chromosome loss. Cancer Res 1994, 54:4756-4759 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Dyke DL, Worsham MJ, Benninger MJ, Kraus CJ, Baker SR, Wolf GT, Drumheller T, Tilley TC, Carey TE: Recurrent cytogenetic abnormalities in squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck region. Genes Chromosomes & Cancer 1994, 9:192-206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogasawara S, Maesawa C, Tamura G, Sakata K, Suzuki Y, Kashiwaba M, Terashima M, Ikeda K, Ishida K, Satou N: Frequent microsatellite alterations on chromosome 3p in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Proc Annu Meet Am Assoc Cancer Res 1995, 36:A3262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng JQ, Crepin M, Hamelin R: Loss of heterozygosity on chromosomes 1p, 3p, 11p and 11q in human non-small cell lung cancer. Serono Symp Publ Raven 1990, 78:357-364 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maestro R, Gasparotto D, Vukosavljevic T, Barzan L, Sulfaro S, Boiocchi M: Three discrete regions of deletion at 3p in head and neck cancers. Cancer Res 1993, 53:5775-5779 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van der Riet P, Califano J, Westra W, Sidranski D: Loss of heterozygosity on chromosome 3p12 and 9p21 in preinvasive head and neck tumors: toward a progression model for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Proc Annu Meet Am Assoc Cancer Res 1995, 36:A3264 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roz L, Wu CL, Porter S, Scully C, Speight P, Read A, Sloan P, Thakker N: Allelic imbalance on chromosome 3p in oral dysplastic lesions: an early event in oral carcinogenesis. Cancer Res 1996, 56:1228-1231 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ransom DT, Barnett TC, Bot J, de Boer B, Metcalf C, Davidson A, Turbett GR: Loss of heterozygosity on chromosome 3p: a poor prognostic factor in squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck (SCCHN). Proc Annu Meet Am Soc Clin Oncol 1996, 15:A870 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Todd S, Franklin WA, Varella-Garcia M, Kennedy T, Hilliker CE, Jr, Hahner L, Anderson M, Wiest JS, Drabkin HA, Gemmill RM: Homozygous deletions of human chromosome 3p in lung tumors. Cancer Res 1997, 57:1344-1352 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rader JS, Gerhard DS, O’Sullivan MJ, Li Y, Li L, Liapis H, Huettner PC: Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia II shows frequent allelic loss in 3p and 6p. Genes Chromosomes & Cancer 1998, 22:57-65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones MH, Nakamura Y: Deletion mapping of chromosome 3p in female genital tract malignancies using microsatellite polymorphisms. Oncogene 1992, 7:1631-1634 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inoue H, Ishii H, Alder H, Snyder E, Druck T, Huebner K, Croce CM: Sequence of the FRA3B common fragile region: implications for the mechanism of FHIT deletion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997, 94:14584-14589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Le Beau MM, Drabkin H, Blover TW, Gemmill R, Rassool FV, McKeithan TW, Smith DI: An FHIT tumor suppressor gene? Genes Chromosomes & Cancer 1998, 21:281-290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitra AB, Murty VV, Li-RG, Pratap M, Luthra UK, Chaganti RS: Allelotype analysis of cervical carcinoma. Cancer Res 1994, 54:4481–4487 [PubMed]

- 33.Adamson R, Jones AS, Field JK: Loss of heterozygosity studies on chromosome 17 in head and neck cancer using microsatellite markers. Oncogene 1994, 9:2077-2082 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Field JK, Adamson RE, Tsisiyotis C, Zoumpourlis V, Howard P, Jones AS: Allelic imbalance on chromosomes 3 and 17 in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas indicates novel predisposing sites. Proc Annu Meet Am Assoc Cancer Res 1994, 35:A687 [Google Scholar]

- 35.El-Naggar AK, Hurr K, Huff V, Clayman GL, Luna MA, Batsakis JG: Microsatellite instability in preinvasive and invasive head and neck squamous carcinoma. Am J Pathol 1996, 148:2067-2072 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohata H, Emi M, Fugiwara Y, Higashino K, Nakagawa K, Futagami R, Tsuchiya E, Nakamura Y: Deletion mapping of the short arm of chromosome 8 in non-small cell lung carcinoma. Genes Chromosomes & Cancer 1993, 7:85-88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wistuba II, Montellano FD, Milchgrub S, Virmani AK, Behrens C, Chen H, Ahmadian M, Nowak JA, Muller C, Minna JD, Gazdar AF: Deletions of chromosome 3p are frequent and early events in the pathogenesis of uterine cervical carcinoma. Cancer Res 1997, 57:3154-3158 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tate JE, Mutter GL, Crum CP: Monoclonal origin of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia and some vulvar hyperplasia. Am J Pathol 1997, 150:315-322 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Solinas-Toldo S, Durst M, Lichter P: Specific chromosomal imbalances in human papillomavirus-transfected cells during progression toward immortality. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997, 94:3854-3859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]