Abstract

The E. coli isolate CT596 excludes infection by the Myoviridae T4 ip1− phage that lacks the encapsidated IPI* protein normally injected into the host with the phage DNA. Screening of a CT596 genomic library identified adjacent genes responsible for this exclusion, gmrS (942bp) and gmrD (708bp) that are encoded by a cryptic prophage DNA. The two genes are necessary and sufficient to confer upon a host the ability to exclude infection by T4 ip1− phage and other glucosyl-hydroxymethylcytosine (glc-HMC) Tevens lacking the ip1 gene, yet allow infection by phages with nonglucoslyated cytosine (C) DNA that lack the ip1 gene. A plasmid expressing the ip1 gene product, IPI*, allows growth of Tevens lacking ip1 on E. coli strains carrying the cloned gmrS/gmrD genes. Members of the Teven family carry a diverse and, in some cases, expanded set of ip1 locus genes. In vivo analysis suggests a family of gmr genes that specifically target sugar-HMC modified DNA have evolved to exclude Teven phages, and these exclusion genes have in turn been countered by a family of injected exclusion inhibitors that likely help determine the host range of different glc-HMC phages.

Keywords: restriction, DNA modifications, DNA injection, virus evolution, myoviridae

Introduction

It has long been thought that bacteria and their phages have co-evolved exclusion and anti-exclusion mechanisms1. Such dual “antagonistic co-evolution”2 is also exemplified by phage versus phage exclusion mechanisms; indeed, host exclusion of infecting phages is often due to prophage or defective prophage DNAs carried within the host. Phage exclusion strategies are exceedingly diverse, as they are based on (i) proteolysis3, 4, (ii) membrane impermeability5, (iii) blockage of macromolecular synthesis6, as well as other mechanisms7, 8. Exclusion can be apoptotic or “altruistic”, sacrificing individual bacteria for the population3, or alternatively, operate through a non-abortive (i.e. non-killing) mechanism whereby phage infection is halted in the absence of host death.

Prominent among the non-abortive exclusion strategies are restriction-modification (R-M systems) and modification-dependent system (MDS) enzymes that degrade the invading phage DNA9–11. To avoid destruction by resident restriction systems, the Teven Myoviridae phages cloak their DNA in extended modifications, including methylated adenine, 100% hydroxymethylated cytosine (HMC), and glucosylated HMC (glc-HMC)12. Methylated adenine and HMC are used to thwart digestion by Type I and Type III such as EcoKI and EcoP112 R-M systems, as well as by many Type II restriction endonucleases13. Glc-HMC in turn protects against the Mcr family of endonucleases that were the first enzymes known to be able to digest HMC phage DNA14.

Glucosylation of Teven HMC DNA is performed by the phage-encoded α-glucosyltransferase and β-glucosyltransferase following incorporation of Hm-dCTP during replication, and is dependent upon UDPG produced by the bacterial UDPG pyrophosphorylase12, 15. T4 glucosylates 100% of its HMC residues, 70% are α-linkages and 30% β-linkages. In T6 only 3% are α-glc while the β linkages are found in gentiobiose form (a second glucose in a β linkage bound to a pre-existing α-linked glucose) and account for 72% of all glc-HMC modified sites. T2 uses α-linked glucosylation at 70% and gentiobiose at 5% of HMC sites16. It has yet to be established to what extent the sugar distributions are random with respect to DNA sequence and whether other sugar modifications will be found among the more recently studied members of the extended Myoviridae family of phages. Until our discovery of the GmrSD enzyme, no restriction system had been discovered that is capable of specifically targeting these glucose-modified HMC residues to effectively restrict Teven phage in vivo.

In addition to extensive base modifications, phages can also use proteins to physically shield target DNA sequences in their genomes or to inactivate host cell exonucleases and endonucleases. For example, the ocr protein of T3 and T7 binds to and inactivates EcoKI by mimicking the β-form of DNA bound by Type I systems17–19. The T4 g2 protein product protects the ends of the injected DNA from attack by the RecBCD enzyme20. Our work reveals that the Myoviridae encapsidate a diverse set of ip1 locus-encoded internal proteins that likely function to protect Teven DNA from the novel GmrSD enzyme family. These ip1 locus ORFs are characterized by a number of common features21, 22. They are found in forty-five Teven phages as single genes or as a cluster of closely related genes situated between ORF 57.B and ORF 2, with the gene product of the T4 ip1 gene designated IPI and the other ip1-like orfs designated IP5-IP9 in the other phages; IP2-IP4 are encoded at a distant locus adjacent to gene e. Each of the ip1-like orfs in the Teven genomes is embedded in intergenic regions with comparable sequences, and each encodes an N-terminal consensus capsid targeting sequence (CTS) that directs the protein into the procapsid scaffold22. Processing by the head assembly protease gp21 at a consensus sequence during head maturation removes this N-terminal CTS and leaves the processed protein with the packaged DNA to be injected into the host. Only the IPI* (the processed form of the IPI protein found in the mature phage particle and injected into the infected host) of T4 has been thoroughly studied and characterized with respect to the amount that is packaged within the capsid (~360 molecules) 23, the N-terminal processing of the CTS that yields the encapsidated IPI* 24, and its injection and anti-exclusion function upon injection25.

The natural hospital strain E. coli CT596 is able to exclude, among most other phages, T4 phage lacking the encapsidated IPI* protein. T4 ip1− mutants display no defect in infection of most E. coli strains. Thus this protein appears to have been procured specifically to protect T4 from the largely uncharacterized exclusion system of hosts such as CT596. Early studies revealed that the T4 ip1− infection process is halted prior to phage mRNA synthesis and that the IPI* protein is responsible for the observed inhibition. DNA degradation was demonstrated to occur in the absence of injection of the IP1* protein. However, since a specific degradation enzyme was not discovered, DNA breakdown could have been an indirect consequence of failure of DNA to cross the host membrane productively as in some other exclusion mechanisms26.

In this work, the genetic basis for the T4 ipI defective exclusion system residing within CT596 is characterized. It is shown that T4 ip1− exclusion is due to the actions of two unique gene products, GmrS (glucose modified restrictionS) encoded by gmrS and GmrD encoded by gmrd. Together they form the enzyme GmrSD, which is specifically overcome by the T4 IPI* protein. When GmrD is fused at its COOH-terminal end to a 6XHis-tag, this imparts upon the enzyme an intermediate exclusion activity that may be overcome by both IPI* and the IPI* related IP5* protein of certain Teven phages. Additionally, E. coli expressing the T4 IPI* protein as a 6XHis-tag fusion from a plasmid and expressing the gmrS/gmrD genes from a compatible plasmid (i.e. gmrS/gmrD clones) are observed to inhibit specifically GmrSD exclusion of different glc-HMC DNA Tevens. This in vivo analysis supports the hypothesis that the polymorphism of the Teven sugar modified HMC residues and the parallel polymorphism of their ip1 locus genes are evolutionarily linked, and further that the ip1 locus genes of the Teven family function to counteract the novel Gmr family of sugar HMC-targeting enzymes.

Results

T4 ip1− E. coli CT596 Exclusion Genes are Encoded by a Cryptic Prophage

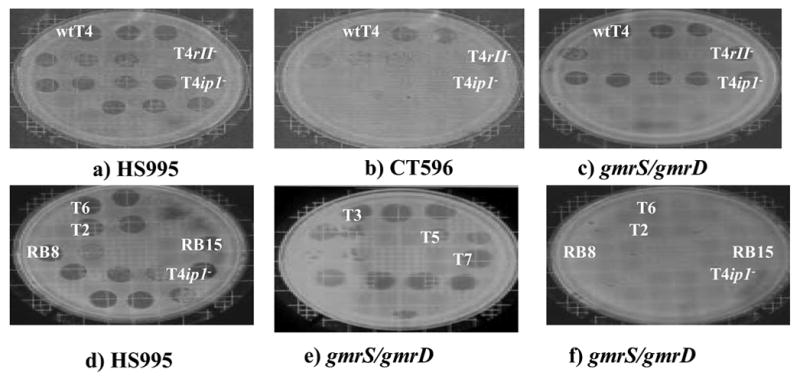

A partial BamHI digest of E. coli CT596 DNA was ligated into the pBeloBAC11 vector and the library was screened by a series of in vivo challenges that use T4 ip1− phage (gene deletion or amino acid missense mutants) to select for transformants expressing the T4 ip1− resistant phenotype. The two survival screens (see methods) were possible because of the non-killing mechanism by which CT596 excludes T4 ip1− 25,27. Figure 1 illustrates wild type T4, T4 rII− and T4 ip1− phage growth on an E. coli DH10B transformant designated B11N that contains a 35 kb E. coli CT596 DNA insert encompassing the gmrS/gmrD genes in the single copy pBeloBAC11 vector. T4 rII− mutants were included in the initial screen because the ip1− and rII- resistances of CT596 were thought to be linked in a mitomycin curable cryptic prophage element25. E. coli DH10B containing only the empty pBeloBAC11 vector (HS995) allowed for full growth of the three phages, seen as a readily visible clear spot in the bacterial lawn due to elimination of bacteria employing high concentrations of phage. Individual plaques at high dilution were used to determine the phages’ efficiency of plating (eop). In contrast, the B11N clone exhibits specific restriction of T4 ip1− equal to that seen on CT596, yet still allowed full growth of wtT4 and T4 rII− (Figure 1 (b) and (c)). All three T4 ip1 defective mutants (deletions and amino acid replacements) exhibited comparable defective growth on this and other E. coli CT596 derived restrictive clones.

Figure 1. Exclusion properties of E. coli CT596 clones toward phages with modified and unmodified DNAs.

Compared to growth of phages on standard E. coli such as DH10B (with a BAC vector, HS995) (a) and (d), E. coli CT596 excludes growth of most phages except T4 and close relatives with the ip1 gene (b). DH10B BAC transformant B11N containing the gmrS/gmrD genes cloned from CT596 specifically excludes growth of glucosyl HMC DNA phage T4 and close relatives that lack ip1 (c) and (f). However the gmrS/gmrD genes do not affect the growth of phages such as T3, T5 and T7 containing unmodified cytosine DNA (e). Phage growth is assayed by serial hundred fold dilutions from ~1010/ml.

Clone B11N also restricts a number of Teven phages, however it remains sensitive to Todd and lambda phages. E. coli CT596 restricts all of these phages, showing that only some of the restriction genes of this host are present in this clone (Figure 1 (e) and (f)). A 15 kb BamHI subclone (pBexB) of the35 kb B11N BamHI fragment was found to retain the resistance phenotype. This more tractable insert was used for transposon insertion mutagenesis to locate the genetic elements responsible for the observed T4 ip1− restriction. The majority of the apparent loss-of-exclusion insertions, however, were found to have occurred within vector sequences responsible for maintaining the pBeloBAC11 plasmid in E. coli (e.g. parA, parB, parC). Nevertheless, one clone (CLE) was found by restriction digest analysis to be sensitive to phage T4 ip1−due to Tn10 insertion within the CT596 genomic sequence (Table 1).

Table 1. Exclusion properties of clones derived from E. coli CT596.

Relative titers of phages on the various transformants containing gmrS (S), intergenic region (i) and/or gmrD (D) are given. In the table, + = efficiency of plating (eop) > 0.6, and - = eop < 10−6. The DNA fragments in the clones are listed in the first column, and the clone designations listed in the second column (see Figure 3).

| CT596 Genetic Elements Encoded | Strain or Gmr Clone Designation | PHAGE | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wtT4 | T4ip1− (A58T) | T4rII− | T2/T6/RB15 | T3/T7/λ | RB69/C16 | ||

| ALL | CT596 | + | − | − | − | − | + |

| ----- | DH10B | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 35kb | pB11N | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| 15kb | pBExB | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| 15kb+Tn10 | pCLE | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| S, D, 3, 4 | pCONTIG | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| S, i, D | pARC | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| S, i | pSI | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| i, D | pID | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| S, no i, D | pSNID | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| short S, i, D | pPLSE | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| S, i, D-His6 | pL7H | + | − | + | − | + | + |

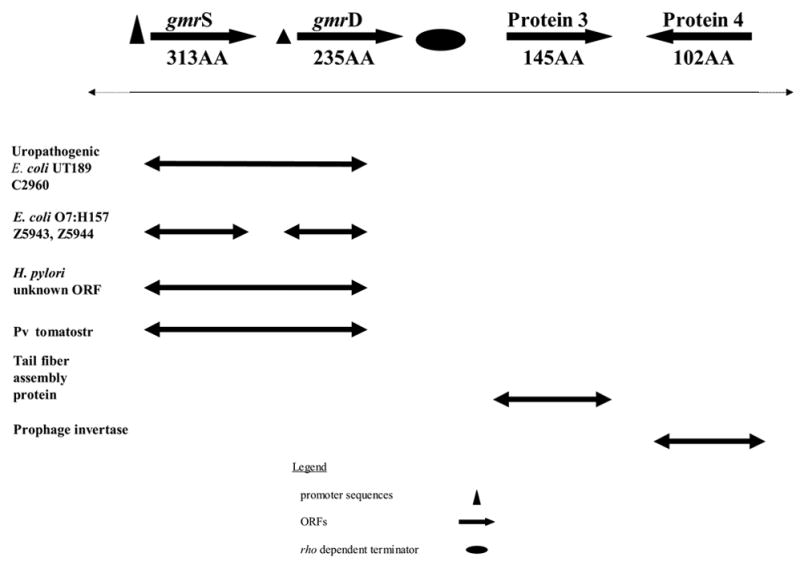

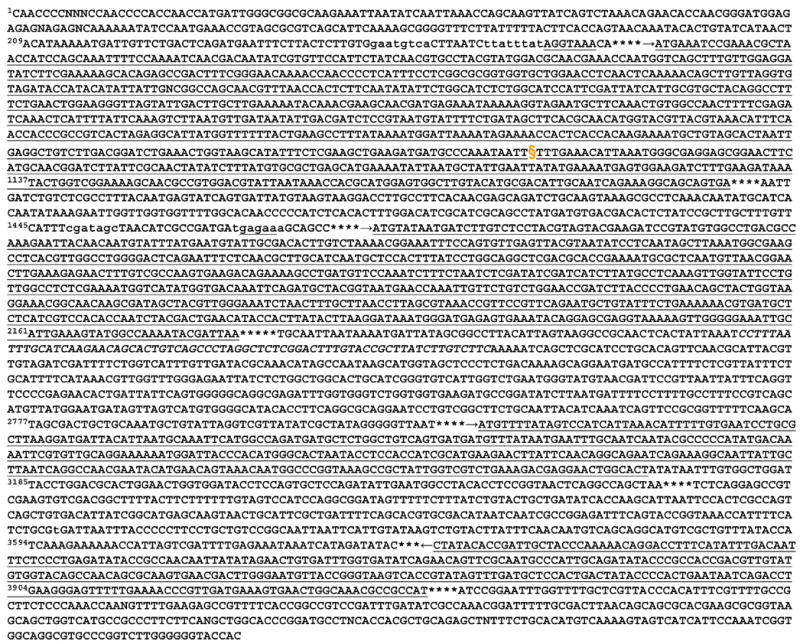

The region surrounding the transposon within the CLE 15 kb insert was sequenced in both directions through standard chromosome walking techniques, and four ORFs were found within an interrupted E. coli K-12-like RNA polymerase-β sequence that lies adjacent to the β-polymerase gene of E. coli K12 (position 3879244..3880344, complete genome accession # NC_000913), which is a region known to undergo high rates of recombination with exogenous DNAs (Figure 2(a)). The sequence of this entire 3.7 kb contig was determined (Figure 2(b)) and its gene structure is illustrated as a schematic in Figure 2(a). The four ORF’s within this contig (gmrS, gmrD, protein3 and protein4) comprise approximately 3.6 kb of the sequenced region. Derivation of the pCONTIG sequences from a prophage in CT596 is strongly supported by the sequences of protein3 and protein4, the former being >90% homologous to several phage tail fiber assembly genes and the latter being modestly (32%) homologous to a phage invertase. The presence of a putative rho-dependent termination sequence and predicted stem loop structure elements lead to the speculation that the two genes are cotranscribed28, consistent with the fact that gmrS and gmrD must be cotranscribed to yield a single ORF in the ~90% homologous gene of E. coli UT189, as discussed later. The latter two genes have been deposited in the NCBI GenBank as gprotein3 accession no: 21217465 and gprotein4 accession no: 21217466.

Figure 2a. A summary diagram of the E. coli CT596 four ORF pCONTIG clone containing the gmrS/gmrD genes.

The four ORFs of pCONTIG display homology to ORFs in other organisms, sometimes with fused gmrS/gmrD genes. The pCONTIG Protein 3 and Protein 4 sequences display evidence of a prophage origin. Also shown are putative regulatory elements with the strength of the regulatory elements indicated by symbol size. .

Figure 2b. Nucleotide sequence of the entire 3.6 kb E. coli CT596 clone pCONTIG containing gmrS, gmrD, Protein 3 and Protein 4.

ORFs are underlined, with arrows depicting the direction of transcription. The −10 and −35 regions are uncapitalized, the ribosome binding sites are underlined prior to the start of the gmrS and gmrD coding regions. The putative rho termination sequence is in italics. The transposon (Tn10) insertion site resulting in the loss of T4 ip1− exclusion is indicated with the symbol §.

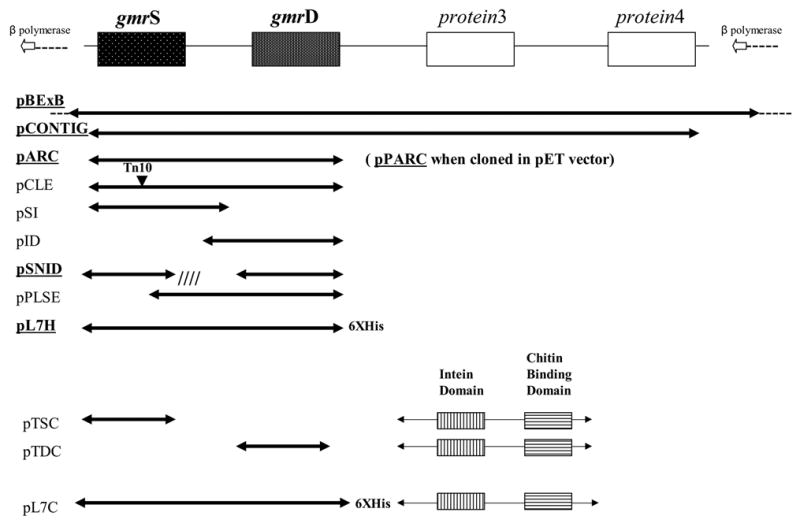

The first two ORFs, glucose-modified DNA restriction Start (gmrS) and glucose-modified DNA restriction Downstream (gmrD), proved to confer upon DH10B the ability to specifically resist T4 ip1− phage (Figure 3). There was no significant difference observed in the clones’ Ability to Resist Challenge by T4 ip1− when the genes were cloned into either a medium copy pET vector (pPARC) or in the single copy pBeloBAC11 vector (pARC). Removal of the intergenic region between gmrS and gmrD (to form pSNID) did not affect the restrictive phenotype (Table 1). Neither gmr gene individually demonstrated a restrictive phenotype (pSI, pID). In addition, an alternative, mid-gene translation of a truncated gmrS (beginning at methionine256 and ending distal to gmrD) (pPLSE) was insufficient for restriction. Overall, it could be concluded that the expression of both gmrS and gmrD is necessary and sufficient to restrict T4 ip1−. Moreover, restriction of Teven phages, Todd phages and lambdoid phages are consistent for those derivatives of the initial isolate that retain the T4 ip1− resistance (Table 1). Restriction by these clones was not dependent on the host genotype (E. coli DH10B and E. coli BL21(DE3), among others, were comparable), and expression could be initiated from a number of plasmid promoters as well as the CT596 promoter(s). In fact, analysis of the sequences surrounding the gmrS and gmrD genes leads to the speculation that these two genes are cotranscribed in CT596. Preceding gmrS, there are strong -35 (GAATGTCA) and -10 (TTATTTATT) promoter consensus sequences and a strong consensus ribosome binding site (S/D) sequence (AGGTAAA) 29. In contrast, the gmrD promoter, if any, is weak in relation to known sequences (−10 of TGAGAAA; −35 of CGATAGC), whereas its S/D sequence is strong (GAGAAA). Although independent transcription of gmrS and gmrD cannot be excluded, it is likely that they are cotranscribed as a two-gene cassette from the gmrS promoter. No other transcription initiation sequences were evident within the gmrS/gmrD region. These two gmr gene sequences have been catalogued in GenBank as gmrS and GmrS accession no: 21327768 and gmrD and GmrD accession no: 21327770.

Figure 3. Schematic of E. coli CT596 derived clones, their gene content, and their exclusion properties.

Those conferring T4 ip1− exclusion to the cell are underlined.

Specificity of gmrS/gmrD restriction and phage inhibition

The gmr restriction system was examined for its specificity of resistance towards glc-HMC phages as well as to unmodified cytosine DNA phages. The gmrS/intergenic/gmrD transformant pARC and the clone pBExB that possesses the gmr genes within a 15 kb insert gave equivalent results (Table 1). Only some glc-HMC phages are restricted, whereas no cytosine DNA phages (T3, T7, T5 and lambda, among others) are restricted. All of these phages except some of the Tevens are excluded by CT596. Further testing, shown in Table 2, revealed that the cloned gmr genes generally confer resistance to glc-HMC Tevens lacking IPI* (T4 ip1−, T2, T6, RB15 and RB70). However, glc-HMC Tevens that contain IPI* are generally not restricted (T4, RB69 and C16), although the correlation is not perfect since phage K3 (with ip9, ip7, ip8 at the ip1 locus) can infect gmr transformants. Moreover, RB69 plaques are small on pBExB clones, suggesting only partial protection by IP1*. Phages RB49, RB42 and RB43 are not restricted by the gmr clones. These three pseudo Teven phages apparently do not contain HMC DNA, nor, in the case of RB49, ip1 locus genes, although they contain many gene sequences similar or identical to phage T4 genes22,30 (J.D. Karam, Tulane University Web Site). Overall, it was concluded that the exclusion profile of gmrS/gmrD is directly related to the gene variants existing at the Teven ip1 locus (i.e. generally the lack of a T4 IPI* leads to exclusion) and the state of HMC glucosylation (i.e. the enzyme system acts only on glc-HMC DNA)27, 34, and since non-glucosylated phage T4 (T*) is not excluded by E. coli CT596 (Abremski, K. Ph.D. thesis).

Table 2. The ip1 locus genes encode antagonists of the gmrS/gmrD genes.

Growth of T-even phages that possess glc-HMC DNA and lack IPI* is inhibited by the co-expression of gmrS/gmrD from pBExB, and expression of IPI* from a compatible plasmid pET15b prevents their exclusion, whereas expression of an IPI* missense protein does not. Extensive ip1 locus polymorphism among Teven phages is found and correlates with growth on the gmrS/gmrD genes containing host with ip1 most effective in antagonizing the gmrS/gmrD exclusion.

| Inhibitor Plasmid | ---- | ← pET15b → | ---- | ---- | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +/− ip1 gene | ---- | ---- | ip1+ | ip1− aa | ---- | ---- | ||

| GMR resistance plasmid | ← pBExB → | L7Hb | ---- | |||||

| Phage | ip locus gene products | DNA | E. coli BL21(DE3) | |||||

| T4 | IPI* | HMC | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| T4 ip1− | ---- | HMC | − | − | + | − | − | + |

| RB15 | IP5, IP7, IP8, IP9 | HMC | − | − | + | − | − | + |

| K3 | IP7, IP8, IP9 | HMC | +/− | +/− | + | +/− | + | + |

| T2 | IP5, IP7 | HMC | − | − | + | − | − | + |

| T6 | IP5, IP6 | HMC | − | − | + | − | +/− | + |

| RB70 | IP5 | HMC | − | − | + | − | +/− | + |

| C16 | IPI* | HMC | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| RB69 | IPI* | HMC | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| RB49 | ---- | C | + | + | + | + | + | + |

ip1− = ip1 double mutant A58T, E56K

L7 = gmrS/gmrD-His tag in pET21, as shown in Fig. 3

+ = efficiency of plating (eop) > 0.6

− = eop < 10−6,

+/− = intermidate eop with small or minute plaques

Interestingly, fusion of a short 6XHis tag to the C-terminal coding end of gmrD to produce pL7H resulted in an intermediate restriction profile of the clone containing a wild type gmrS gene and an altered gmrD gene (Figure 3). As expected, there was no change seen in the ability of cytosine DNA containing Todds (T3, T7 and T5) to successfully infect strains carrying pL7H (Table 1). However, the L7H resistance displayed toward phages containing glc-HMC modified DNA was different from the full gmr clone pBExB (Table 2). The presence of the 6XHis Tag did not alter the ability of the gmr genes to restrict phages T4 ip1−, T2, and RB15. However, the clone appeared to display either an altered specificity or weaker restriction that allowed intermediate growth of phages T6 and RB70. Thus a more limited L7H resistance spectrum again appeared to target specifically those phages containing glc-HMC modified DNA in addition to lacking the T4 IPI* protein. The altered restriction profile also suggested the possibility that the altered L7H resistance could be overcome by interaction between ip5 and the modified gmr gene products, i.e. that IP5* could partially fill in for IPI* in some genetic contexts (see discussion).

The inhibition of the gmrS/gmrD restriction system by the T4 IPI* protein was pursued further by cloning a derivatized ip1 phage gene into a pET15b expression vector to express an N-terminal His-tag derivatized IP1*. When the pET15b compatible pBExB BAC plasmid construct is also introduced into E. coli BL21 (DE3), inhibition of the gmrS/gmrD restriction system by the expressed His-tag IP1* protein is determined by phage plating (Table 2). The empty pET15b expression vector has no effect on the ability of pBExB to inhibit the growth of Teven phages lacking ip1. The IPI* expression vector allows all Tevens tested to grow, even in the absence of IPTG induction of the T7 promoter-driven gene, presumably due to weak IPI* expression. The specificity of this IPI* protein inhibition is demonstrated by the observation that the isogenic cloned ip1 mutant HA35 (A58T, E56K) does not inhibit GmrSD exclusion of ip1− Tevens.

gmrS/gmrD Sequence Analysis

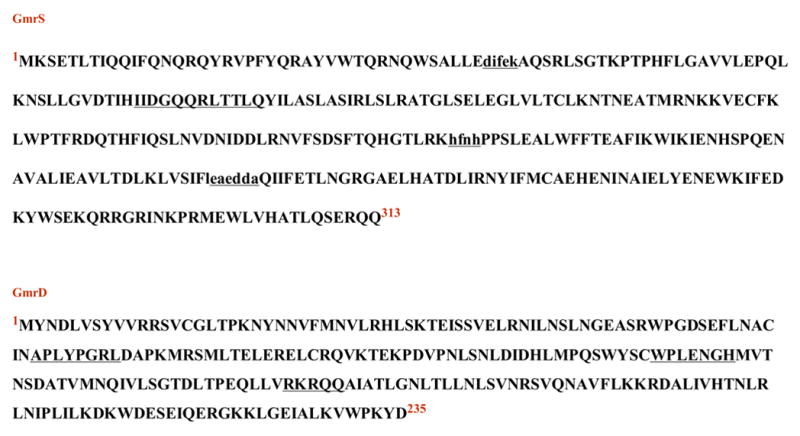

Introduction of the gmrS/gmrD nucleotide sequences into the NCBI Blast program reveals homologies ranging from 40% to 94% to numerous pairs of adjacent ORFs of unknown function. These sequence homologies are found to conserved hypothetical proteins whose sources include two slightly longer and adjacent genes of E. coli K-12 (approximately 43% homology), the uropathogenic E. coli UT189 (hypothetical protein C2960 at 84% and 94% identity to gmrS and gmrD respectively), E. coli O157:H7 (the separate genes Z5943 and Z5944 at 39% each), H. pylori (numerous sequences with an average homology of 42%) and Pseudomonas syringae pv. Tomatostr. DC3000 (at 65% similarity to gmrS and 62% similarity to gmrD), and to one large protein sequence with an average 50% similarity in C. jejuni (RloF), C. chlorochromatii (hypothetical protein) and A. vairiabilis (hypothetical protein). Of interest, in some hosts such as E. coli UT189 the gmrS gene, the intervening sequence and the gmrD gene are fused to yield a single polypeptide chain (Figure 2a). Possibly of significance to deciphering its function, at the amino acid level most of the unorganized sequence (a designation given by NCBI BLAST) of gmrS (94ILASLASIRLSLRA107) is matched by only the Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomatostr DC30001 gmrS-like gene. These results lead to the speculation that there are a number of GmrSD-like enzymes that exist across a number of bacterial species, with each form of GmrSD-like enzyme potentially possessing unique biochemistry. GmrS and GmrD were screened for homologies to known restriction endonucleases. The GmrS protein (Figure 4(a)) possesses the putative endonuclease motifs 228LEAEDDA234, 178HFNH181 and 41DIFEK45 of the LAGLIDADG and HNH families31, 32. These sequences may potentially confer upon this protein the ability to act as the nuclease subunit of the enzyme. Only GmrS was found to contain an extended conserved domain. The 81IIDGQQRLTTLQ92 amino acid sequence has near 100% identity to the DUF (Domain of Unknown Function) motif. The DUF region is found in of the DUF- and COG-containing families, which contains enzymes responsible for UTP hydrolysis33. It was determined that GmrD contains motifs similar to DNA-binding proteins (Figure 4(b)).

Figure 4. The amino acid sequences of GmrS and GmrD.

Highlighted are regions containing putative functional motifs. In GmrS, the endonuclease-like sequences are in lower case and underlined, and the DUF domain is underlined. In GmrD the putative DNA binding motifs are underlined.

Discussion

In this work the genes responsible for the T4 ip1− resistance phenotype of E. coli CT596 were cloned and analyzed. The analysis demonstrates that gmrS and gmrD are necessary and sufficient to confer specific resistance to T4 ip1− infection as well as to infection by numerous other glc-HMC Teven family members lacking ip1, but not to phages lacking glc-HMC modified DNA. Other E. coli CT596 phage exclusion and restriction genes (e.g. of T4 rII−, Todd and lambdoid phages) proved to be separable and distinct. Since IPI* is completely dispensable for infection of most bacteria, the singular function of the encapsidated IPI* is apparently to counter restriction genes comparable to the gmrS/gmrD genes of CT596. In fact, there is evidence for comparable restriction systems among some other “natural” E. coli strain isolates that also restrict T4 ip1− mutants (unpublished observations). In addition, the presence at the sequence level of gmrS and gmrD homologues in species as varied as uropathogenic E. coli UT189, H. pylori, E. coli O7:H157 and P. syringae suggests that this type of restriction system might be widespread. This is consistent with the location of these genes on a prophage in CT596, likely reflective of horizontal transfer. In light of the high degree of diversification of gmrS-like and gmrD-like genes and the coincident diversification of the ip1 locus of genes across Myoviridae, it can be speculated that a specific functional co-evolution has occurred between bacterial hosts and their parasitic glc-HMC phages.

Despite convincing homology to proteins of unknown function in other organisms, presumably gmrS and gmrD-like restriction genes, sequence analysis of GmrS and GmrD showed that the proteins are novel compared to proteins of known function and show only modest homologies to amino acid sequence motifs of DNA binding proteins and nucleases. However, one significant and relatively extended sequence identity was to a domain of unknown function (DUF) found in members of a family of proteins that includes UTPases. These sequence similarities to nucleases and NTPases are consistent with our biochemical characterization of the GmrS protein34.

The specificity of inhibition by the ip1 gene locus family of gmrS/gmrD restriction was determined through in vivo and in vitro analysis of a variety of Teven and Todd phages and their genomes. Expression of the 6XHis-IPI* protein in a host expressing the gmrS/gmrD genes demonstrates that it can function in trans to allow growth of Teven phages on gmrS/gmrD hosts. These results also demonstrate that the IPI* protein can block restriction of Teven DNAs without entering the host bound with the DNA, although these basic internal proteins are found to be bound to T4 DNA when released from the capsid23. Several Teven phages containing the ip1 gene (i.e. those of the sequenced T4, C16 and RB69) were able to overcome gmrS/gmrD restriction (Table 2), further supporting the proposed functional link between restriction avoidance and the ip1 locus. The inability of most Tevens (RB15, T2, T6, RB70) that lack the IPI* protein to infect gmrS/gmrD hosts further supports the specificity of inhibition by IPI*. Numerous other unsequenced Teven phages that appear to carry the ip1 gene by PCR analysis35 were tested and most were found also able to infect gmrS/gmrD clones (data not shown). One explanation for the lack of IPI* protection of a few of the IPI*-containing phages is that there may be HMC targets among some of these phages that are not protected from the gmrS/gmrD restriction by IPI*. An alternative explanation for the inability of a few ip1 containing Tevens to infect may be due to inactivating mutations in IPI among these phages, in light of the fact that sequence differences are known to exist within several of the sequenced ip1 variant genes22. In the absence of growth selection on gmrS/gmrD hosts, it is likely that mutations may accumulate in the ip1genes. In support of this interpretation, apparently minor amino changes in the T4 IPI− mutant HA35 (A58T, E56K) eliminate function (Table 2). In fact, it is likely that the residue 56 mutation is silent since, surprisingly, the single amino acid replacement of T4 IPI− mutant KAI− (A58T) is equivalent in eliminating ip1 function as well as the IPI* protein from the phage head25.

The specificity of the gmrS/gmrD restriction system and of the ip1 locus genes was demonstrated by the altered restriction profile of the gmrS/gmrD-6XHis mutant clone L7H. This clone demonstrated an intermediate sensitivity phenotype to a select few Tevens, all of which contain the ip1 variant ip5. Thus RB70 and T6 (intermediate eop) and T2 (eop = <l0−6) (Table 2) exhibited different growth on L7H from the gmrS/gmrD containing pBExB. The amino acid sequences of gene ip5 within phages T2 and RB70 contain one and five amino acid changes in relation to the ip5 of phage T6, respectively22. Also, there is only one gene encoded within the RB70 ip1 locus and two within those of T2 and T6. The potential advantage or disadvantage of possessing only one form of a gene at the ip1 locus is difficult to assess. In T4 phage, there are a limited number of internal proteins that are observed to be packaged (~1200, ~360 of which are IPI*, the remainder IPII* and IPIII*) within the capsid23. Thus in cases where the phage ip1 locus contains more than one gene variant, there likely is a decreased number of each protein relative to the possible total when only one variant is present. Interestingly, it was observed that expression of ip5 allowed partial growth of T6 phage but not of T2 phage. This specific inhibition argues for differences among the glc-HMC targets in T6 (can be overcome by high level expression of IP5*) and T2 (cannot be shielded by IP5), or perhaps that the sequence differences among the ip5 genes are important for specificity and function. The results also suggest that IPI* is superior to IP5* in protecting all the tested Tevens against the gmrS/gmrD restriction system. Overall, the results suggest that the other ip1 locus genes may counter with different specificity restriction systems related to the gmr system.

Although the ip1 locus encoded proteins are all small ~10 kDa proteins, they show no sequence homology except for the signature NH2–terminal capsid targeting sequence peptide cleaved from the proteins by the morphogenetic protease during prohead maturation to yield the mature capsid internal proteins found with the phage DNA22, 23. Interestingly, among many Tevens, ip1 has been found only in isolation at the ip1 locus (in 10 phages), whereas other ip1 locus genes are only sometimes found alone (ip5, alone in 7 cases, in 23 cases with other ip1 genes). The ip6, 7, 8 and 9 genes are always found with other ip1 genes (25 cases), sometimes with as many as three other ip1 genes, and generally with ip535. This could suggest that IPI* is able to function independently, whereas the other ip1 genes are cooperative. Such specificity could operate at the DNA level (glc-HMC targets), protein level (GmrS and/or GmrD targets), or both. A direct relationship between the restriction inhibition by an ip1 locus gene product and the targeted glc-HMC in a phage’s DNA is suggested by the poor growth of RB69 (contains a T4 ip1gene and HMC modified DNA with a sugar modification that is unlikely to be glucose, rather perhaps mannose (http://phage.bioc.tulane and J.D. Karam, personal communication). Further study is necessary for a definite conclusion about the mechanism of ip1 locus gene inhibition of GmrSD-like exclusion in relation to the diverse sugar modifications that appear to exist among the HMC containing phage DNAs. Further information about the mechanism and specificity of this type of exclusion system and its phage ip1locus antagonists might allow an assessment of a possible causal relationship between sugar-HMC polymorphism and ip1 locus polymorphism.

Materials and Methods

Phages

T4 mutants used in this project: T4 ip1− (ΔeG506 a T4 ip1− deletion; and ΔeG192 a control overlapping deletion except for the T4 ip1− gene; T4 ip1− point mutants HA35 (E56K, A58T) and KAI− (A58T) 25, T4 rII− Δ1272 is a deletion of the rIIA and B genes. Todds (T3, T5, T7), and lambda were from this laboratory. A number of Tevens are from this laboratory or were a generous gift of Henry Krisch, University of Toulouse, France. The sequences of the T4 ip1 locus genes of phages T4, T2, T6, RB15, K3, RB70, and C16 were reported22. Sequencing of ip1 in phage RB69 and absence of the T4 ip1− locus genes in the unmodified DNA of pseudo Teven RB49 were reported by J.D. Karam (Tulane web site). Identification by PCR analysis of the T4 ip1 locus genes of phages M1, RB27, RB30, RB59, N209, DDYI, D8, Ac3, RB2, RB52, RB53, RB5, RB32, RB33, FS10, Pol, SKV, SKX, SKII, RB7, RB3, RB6, RB8, RB10, RB14, RB18, RB55, RB60, RB68, SV76.3, RB58, and RB59 was reported35.

E. coli strains

CT596 (a clinical isolate of E. coli serotype K12)25, 22, BL21(DE3) (r−; m−; dcm); DH10B (DE3, recA−, r−, rgl−, sup−); HS995 (DH10B + pBeloBAC11).

Plasmid Vectors

The pBeloBAC11 plasmid was kindly provided by Dr. Shizuya of CalTech. Plasmids pET17b, pET15b, pET21a were purchased from Novagen, pTYB2 was purchased from New England Biolabs.

Plasmid constructs: gmrS and gmrD constructs

pB11N (contains a 35 kb CT596 genomic fragment in pBeloBAC11; cloned using BamHI restriction of CT596 genomic DNA and the pBeloBAC11 vector); pB11B (contains a 40 kb CT596 genomic fragment in pBeloBAC11; cloned using HindIII restriction of CT596 genomic DNA and the pBeloBAC11 vector); pBexB (contains a 15 kb CT596 genomic fragment that confers T4 ip1− resistance; produced from BamHI-digestion of the pB11N insert); pCLE (Tn10-insertion mutant of pBexB); pS (contains the complete 313 AA GmrS ORF in pBeloBAC11; 5′-3′ (BamHI) CGCGGATCCATGAAATCCGAAAC GCTAACCATCCAGCAA and 3′-5′ (HindIII) CCCAAGCTTTCAATTTCACTGCTGCCTTTCTG ATTGCA); pARC (contains the gmrS + intergenic region + gmrD in pBeloBAC11; 5′-3′ (BamHI) CGCGGATCCATGAAATCCGAAACGCT AACCATCCAGCAA and 3′-5′ (HindIII) CCCAAGCTTCTTTTGTCAGAGGGAGCTACCATGCTT); pPARC (contains the gmrS + intergenic region + gmrD in the higher copy pET17b; 5′-3′ (XhoI) CGGGAGCTCATGAAATCCGAAACG CTAACCATCCAGCAA and 3′-5′ (XhoI) CGGGAGCTCATCGTATTTTGGCCATACTTTCAATGCA); pSI (contains the gmrS + intergenic region in pBeloBAC11; 5′-3′ (BamHI) CGCGGATCCATGAAATC CGAAACGCTAACCATCCAGCAA and 3′-5′ (HindIII) CCCAAGCTTCTTCGTACTACGT AGGAGACAAGATCATT); pID (contains the intergenic region + gmrD in pBeloBAC11; 5′-3′ (BamHI) CGCGGATCCTATGAAAATGAGTGGAAGA TCTTTGA and 3′-5′ (HindIII) CCCAAGCTT CTTTTGTCAGAGGGAGCTACCATGCTT); pSNID (contains the gmrS + gmrD in pBeloBAC11; 5′-3′ (BamHI)CGCGGATCCATGAAATCCGAAACGCTAACCATC CAGCAA and 3′-5′ (HindIII)CCCAAGCTTTCAATTTCACTGCTGCCTTTCTGATTGCA for gmrS. 5′-3′ (HindIII) CCCAAGCTTTGAATGTATAATGATCTTGTCTCCTACGTA and 3′-5′ (BamHI) CGCGGAT CCCTTTTGTCAGAGGGAGCTACCATGCTT for gmrD); pD (contains the gmrD in pBeloBAC11; 5′-3′ (BamHI) CGCGGATCCATGTATAATGATCTTGTCTCCTACGTAG and 3′-5′ (HindIII) CCCAAGCTT CTTTTGTCAGAGGGAGCTACCATGCTT); pCONTIG (contains gmrS + gmrD + protein3 + protein4 in pBeloBAC11 from BamHI digestion of pBExB); pTDC (contains the gmrd-CBD/intein in pTYB2 wherein an alanine and serine residue are added to the N-terminal end, and a glycine residue remains on the C-terminal end following cleavage; 5′-3′ (NheI) CTAGCTAGCTATAATGATCTTGTCTCCTAC GTAGTAC and 3′-5′(SmaI)TCCCCCGGGATCGTATTTTGGCCATACTTTCAATGCAA); pTSC (contains the gmrS-CBD/intein in pTYB2 wherein an alanine and serine residue are added to the N-terminal end, and a glycine residue remains on the C-terminal end following cleavage; 5′-3′ (NdeI) GGAATTCCATATGAAATCCG AAACGCTAACCATCCAGCAA and (SmaI) TCCCCCGGG CTGCTGCCTTTCTGATTGCAATGTC 3′-5′); pL7H (contains the gmrS + gmrD-6XHis (cac) in pET21a; 5′-3′ (BamHI) CGCGGATCCATGAAATCCGAA ACGCTAACCATCCAGCAA and 3′-5′ (XhoI) CGGGAGCTCATCGTATTTTGGCCATACTTTCAATGCA followed by ligation into the His Tag of pET21a); pL7C (contains gmrS + gmrD-6XHis (cac)-CBD/intein in pTYB2; 5′-3′ (BamHI) CGCGGATCC ATGAAATCCGAAACGCTAACCATCCAGCAA and sequential 3′-5′ (HIS)CACCACCACCATCATCAT ATCGTATTTTGGCCATACTT and (SmaI)TCCCCCGGG GTGGTGGTGGTAGTAGTAATCGTATT). All vector constructs were electroporated into DH10B for in vivo assays or into BL21(DE3) for protein expression and purification. Transformants of these constructs are designated by the plasmid name (i.e. DH10B containing pL7 is referred to as L7).

ip1 constructs

Pdl4 and pdl5 contains 231 bp of ip1 encoding the encapsidated IPI* protein from T4 ip1 and T4 ip1 mutant HA35 respectively. The 231 bp DNA fragments were amplified using primers D9 and D10: 5′-3′ (XhoI) CCCCTCGAGGCTACTCTTACTTCTGAAGTTATTAA AGCAA ATAAAGG 3′ and 3′-5′ (BamHI) CCCGGATCCTTACAAAAGATTTTTAGCAATAAT CTTGAGA TGTGC 3′. These fragments were cloned into pET15b at the XhoI and BamHI sites to yield IPI* proteins initiated by a 15 amino acid His tag. These constructs transferred to BL21 (DE3) by electroporation were designated DL13 and DL14, respectively. The construct pBexB was also transferred into DL13 and DL14, and these transformants were designated DL23 and DL24, respectively.

Phage isolation

Phages were isolated and purified by CsCl step gradient centrifugation and phage DNAs were isolated from CsCl phages by proteinase K phenol extractions as described36.

PBeloBAC11 plasmid preparation

The pBeloBAC11 vector, kindly provided by Dr. Shizuya of CalTech, was chosen to prepare an E. coli CT596 BAC library in E. coli DH10B cells essentially as described37, 27.

Preparation of insert DNA

Agarose-embedded CT596 genomic DNA was partially digested with either HindIII or BamHI and ligated to the linearized pBeloBAC11 vector essentially as described37. For insert size analysis, NotI digestion products were loaded onto a 1% SeaPlaque GTG agarose (FMC BioProducts) 0.5xTBE gel and run in the CHEF-DRII system. The pBeloBAC11 vector contains NotI sites flanking the MCS for easy insert analysis.

PCR Amplification

All PCR amplifications were performed in a GeneMate (Denville Scientific) cycler in a 100μL reaction containing 1U Pfu polymerase (Stratagene), 1X supplied buffer (Stratagene), 25 ng template DNA, 50 μM each dNTP and 20 pM each primer.

Electroporation

Twenty microliters of de-salted bacterial cells, at an approximate concentration of 2x1011/mL, were combined with 5 pg to 0.5 μg plasmid DNA using standard electroporation techniques for E. coli cells. Transformed cells were plated on agar supplemented with 12.5 μg/mL chloramphenicol (Sigma), 30 μg/mL kanamycin (Sigma), or 50μg/mL ampicillin (Sigma), and 50 μg/mL X-Gal, 25 μg/mL IPTG where appropriate.

Plate Survival Assay

Clones expressing the T4 ip1− phage resistant phenotype were first identified by challenge with 106 T4 ip1− phage or wild type (wt) T4 phage. Here, colony formation after phage challenge is indicative of potential T4 ip1− restriction. The growth of test transformants is compared to that of non-challenged transformants, to the growth of challenged E. coli DH10B cells containing an empty pBeloBAC11 vector (HS995), and to challenged E. coli CT596.

Culture Survival Assay

Fifty milliliters of a single colony was grown in Tryptone broth culture (TBC) to log phase, infected with T4 ip1 at an multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5 and allowed to continue growing overnight at 37 oC. The culture was analyzed for turbidity and 200 μL was plated on selection plates to assay colony growth under challenge by T4 ip1− at 1X106. Comparison was performed against the growth of E. coli HS995, E. coli CT596 and E. coli DH10B treated in the same manner.

Spot tests

Comparison of phage growth between sensitive and restrictive strains and HS995 determines the efficiency of plating (eop), utilizing the ratio of PFU on a permissive bacterial strain to the PFU for the test strain38.

Transposon Insertion Mutagenesis

PBexB plasmids, purified utilizing the Qiagen Midi Kit (Qiagen), was combined with the transposon, EZ::TN <NotI/KAN-3> Tn5, transposase and 10X buffer provided in the kit (EZ::TN In-Frame Linker Insertion Kit, Epicentre) in the recommended equimolar amounts. The reaction was incubated at 37 oC for 2 h, halted with EZ::TN 10X Stop Solution, heated at 70 oC for 10min then dialyzed against 1X TE prior to electroporation into E. coli DH10B cells.

DNA Sequencing

All sequencing of plasmids and phage DNAs was performed by Sequinet (Colorado State University) using the ABI Prism Model 377 (Version 3.4), with readings done on both strands to verify results.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rocha EPC, Danchin A, Viari A. Evolutionary Role of Restriction/Modification Systems as Revealed by Comparative Genome Analysis. Genome Research. 2001;11:946–958. doi: 10.1101/gr.gr-1531rr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buckling A, Rainey PB. The role of parasites in sympatric and allopatric host diversification. Nature (London) 2002;420:496–499. doi: 10.1038/nature01164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Georgiou Y, Yu N, Ekunwe S, Buttner MJ, Zuurmond A, Kraal B, Kleanthous C, Snyder L. Specific peptide-activated proteolytic cleavage of Escherichia coli elongation factor. Tu Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 1998;95:2891–2895. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Snyder L, Kaufmann G. T4 phage exclusion mechanisms. In: Karam J, editor. Molecular Biology of bacteriophage T4. American Society for Molecular Biology, Cold Spring Harbor Library Press; Washington, D.C.: 1994. pp. 391–396. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kliem M, Dreiseikelmann B. The superimmunity gene sim of bacteriophage P1 causes superinfection exclusion. Virology. 1989;171:350–355. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90602-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haggard-Ljungquist E, Barreiro V, Calendar R, Kurnit DM, Cheng H. The P2 phage old gene: sequence, transcription and translational control. Gene. 1989;85:25–33. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90460-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dai G, Ping SU, Allison GE, Geller BL, Zhu P, Kim WS, Dunn NW. Molecular Characterization of a New Abortive Infection System (AbiU) from Lactococcus lactis LL51-1. AEM. 2001;67:5225–5232. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.11.5225-5232.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molineux I. Host-parasite interactions: recent developments in the genetics of abortive phage infections. New Biol. 1991;3:230–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts RJ, Belfort M, Bestor T, et al. A nomenclature for restriction enzymes, DNA methyltransferases, homing endonucleases and their genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:1805–1812. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bickle TA. DNA restriction and modification systems E. coli and S. typhimurium. In: Neidhardt H, editor. Cellular and Molecular Biology. ASM Press; Washington DC: 1987. pp. 692–696. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Modrich P, Roberts RJ. TypeII RMS. In: Lin J, Roberts RJ, editors. Nucleases. Cold spring Harbor Lab Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1982. pp. 109–154. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carlson K, Raleigh EA, Hattman S. Restriction and Modification. In: Carlson K, editor. Molcular Biology of bacteriophage T4. Cold Spring Harbor Library Press; Washington, D. C.: 1994. pp. 369–381. American Society for Molecular Biology, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pingoud A, Jeltsch A. Structure and function of TypeII restriction endonucleases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:3705–3727. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.18.3705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sutherland E, Coe L, Raleigh EA. McrBC: a multisubunit GTP-dependent restriction endonuclease. J Mol Biol. 1992;225:327–348. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90925-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hattman S, Fukasawa T. Host-induced modification of Teven phages due to defective glucosylation of their DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 1963;50:287–300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.50.2.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lehman IR, Pratt EA. On the structure of the glucosylated hydroxymethylcytosine nucleotides of coliphages T2, T4, and T6. J Biol Chem. 1960;235:3254–3259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moffat BA, Studier FW. Entry of bacteriophage T7 DNA into the cell and escape from host restriction. J Bacteriology. 1988;170:2095–2105. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.5.2095-2105.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walkinshaw MD, Taylor P, Sturrock SS, Atanasiu C, Berge T, Henderson RM, Edwardson JM, Dryden DTF. Structure of Ocr from bacteriophage T7, a protein that mimics B-form DNA. Molecular Cell. 2002;9:187–194. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00435-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bandyopadhyay PK, Studier FW, Hamilton DL, Yuan R. Inhibition of the Type I restriction-modification enzymes EcoB and EcoK by the gene 0.3 protein of bacteriophage T7. J Mol Biol. 1985;182:567–578. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90242-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silverstein JL, Goldberg EB. T4 DNA injection: II. Protection of entering DNA from host Exonuclease V. Virology. 1976;72:212–223. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(76)90324-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Black LW, Ahmad-Zadeh C. Internal proteins of bacteriophage T4D: Their characterization and relation to the head structure and assembly. J Mol Biol. 1969;57:71–92. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90120-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Repoila F, Tetart F, Bouet JY, Krish HM. Genomic polymorphism in the Teven bacteriophages. EMBO J. 1994;13:4181–4192. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06736.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Black LW, Showe MK, Steven AC. Morphogenesis of the T4 Head. In: Carlson K, editor. Molecular Biology of bacteriophage T4. American Society for Molecular Biology, Cold Spring Harbor Library Press; Washington, D.C.: 1994. pp. 218–258. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Isobe T, Black LW, Tsugita A. Complete amino acid sequence of bacteriophage T4 internal protein I and its cleavage site on virus maturation. J Mol Biol. 1977;110:168–177. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(77)80104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Black LW, Abremski K. Restriction of phage T4 internal protein I mutants by a strain of Escherichia coli. Virology. 1974;60:180–191. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(74)90375-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abremski K, Black LW. The function of bacteriophage T4 internal protein I in a restrictive strain of Escherichia coli. Virology. 1979;97:439–447. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(79)90353-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bair C. Setting the Phage for Evolution: Thesis. University of Maryland at Baltimore: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graham JE, Richardson JP. rut Sites in the Nascent Transcript Mediate rho-dependent Transcription Termination in Vivo. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20764–20769. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.20764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilkens K, Rüger W. Transcription from early promoters. In: Karam JD, editor. Molcular Biology of bacteriophage T4. American Society for Molecular Biology; Washington, D.C: 1994. pp. 132–142. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monod C, Repoila F, Kutateladze M, Tetart F, Krisch HM. The genome of the pseudo Teven bacteriophages, a diverse group that resembles T4. J Mol Biol. 1997;267:237–249. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dalgaard JZ, Klar AJ, Moser MJ, Holley WR, Chatterjee A, Mian IS. Statistical modeling and analysis of the LAGLIDADG family of site-specific endonucleases and identification of an intein that encodes a site-specific endonuclease of the HNH family. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4626–4638. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.22.4626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pommer AJ, Ulrike C, Kühlmann AC, Hemmings AM, Moore GR, James R, Kleanthous C. Homing in on the Role of Transition Metals in the HNH Motif of Colicin Endonucleases. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:27153–27160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.27153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bateman A, Coin L, Durbin R, Finn RD, Hollich V, Griffiths-Jones S, Khanna A, Marshall M, Moxon S, Sonnhammer ELL, Studholme DJ, Yeats C, Eddy SR. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D138–D141. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bair CL, Black LW. A Type IV modification dependent restriction enzyme that targets glucosylated hydroxymethyl cytosine modified DNAs. accompanying manuscript. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Repoila F. Thesis. Devant L’Universite Paul Sabatier de Toulouse: 1995. Etude du polymorphisme genomique chez les bacteriophages T-pair. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sambrook J, Maniatis T, Fritsch EF. In: Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2. Sambrook J, editor. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Birren B, Green ED, Klaphalz S, Myers RM, Riethman H, Roskams J. Genome Analysis. In: Birren B, Green ED, Klaphalz S, Myers RM, Riethman H, Roskams J, editors. A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carlson K, Miller ES. Enumerating phage. In: Carlson K, editor. Molecular Biology of bacteriophage T4. American Society for Molecular Biology Press; Washington, D.C: 1994. pp. 421–441. Paper 1 figure legends LB 10/12/06. [Google Scholar]