Abstract

Francisella tularensis subspecies tularensis (type A F. tularensis) is considered to be one of the most virulent of all bacterial pathogens. Mice are extremely susceptible to infection with this subspecies (LD100 via various inoculation routes is <10 cfu). However, it has not been established whether overt virulence differences exist amongst type A strains of F. tularensis. To this end, the present study compared the virulence of two distinct type A strains, FSC033 and SCHU S4, for naïve mice and mice immunized with the live vaccine strain of the pathogen, F. tularensis LVS. One nominal isolate of SCHU S4 was found to be completely avirulent. Another isolate was highly virulent, but all examined cases appeared somewhat less virulent than FSC033. The implication of these findings for future infection and immunity studies is discussed.

Keywords: Francisella tularensis, Virulence, Mice

1. Introduction

Francisella tularensis is a facultative intracellular bacterial pathogen of mammals in which it causes a spectrum of diseases collectively known as tularemia [1,2]. Two clinically important subspecies of the pathogen are recognized, F. tularensis subs. tularensis and subs. holarctica, trivially referred to as type A and B strains, respectively [1,2]. Both subspecies are highly infectious for humans at low dose, however, only type A strains have the capacity to cause high mortality, especially when inhaled. In the past, type A F. tularensis was extensively studied as a potential biowarfare agent, and was routinely employed for infection and immunity studies on tularemia, including studies with human volunteers [3–4]. Amongst other things, the latter work demonstrated the utility of a live vaccine consisting of a pragmatically attenuated Russian type B strain of the pathogen, F. tularensis LVS [5–6]. In the intervening years LVS itself, because it retains residual virulence for mice, was used exclusively to reveal the molecular basis of host defences against the pathogen in murine models [reviewed in 6 and 7]. However, results obtained with LVS have rarely been predictive of those recently obtained using virulent strains of the pathogen [8–12]. Currently, concerns about biosecurity have rekindled research interest in type A F. tularensis infection and immunity [13]. Most of the original work was performed with a human type A isolate of the pathogen termed, SCHU, and its derivatives particularly SCHU S4 [3–5,14]. More recently, SCHU S4 became the sole type A strain to have its genome sequenced [15]. Consequently, SCHU S4 now appears ready to become a mainstay for much future tularemia research. However, to date no infection and immunity studies appear to have been undertaken to establish whether SCHU S4 is representative of type A strains in general. To this end, the current study compared the virulence of SCHU S4 with another highly virulent type A strain, FSC033, for naïve mice and mice immunized with LVS. The latter strain appeared subtly, and often statistically, more virulent than the former. However, for the most part, the observed virulence differences seemed not to be biologically significant. Finally, one nominal type A isolate of F. tularensis turned out to be completely avirulent for mice. Thus, care is needed when choosing an isolate of F. tularensis for virulence studies and for vaccine efficacy testing.

2. Results

2.1. Virulence of F. tularensis isolates for mice

Several years ago we acquired a number of type A and B F. tularensis isolates from Defence Research Development Canada (DRDC, Suffield, Alta, Canada) which, in turn, had obtained them from the Francisella Strain Collection (FSC) of the Swedish Defence Research Agency, Umea, Sweden. One isolate, FSC043, was archived as SCHU S4, but proved to be even more attenuated than LVS with an i.d. LD50 for BALB/c mice >108 cfu [16]. In contrast, another type A strain, FSC033, originally isolated from a squirrel, proved highly virulent for a variety of mouse strains with an LD100 of <10 cfu when administered either as an aerosol or via the i.d. route [8–11]. Consequently, it was used in all of our recent studies on F. tularensis infection and immunity [8–11,17–19]. More recently, we received from FSC a bona fide isolate, of virulent SCHU S4, archived as FSC237. This isolate was used to generate the published genome of SCHU S4. An initial screen in BALB/c mice showed that it too had a very low LD100 (<10 cfu) when administered intradermally. However, the median time to death (MTD) of BALB/c mice was 7 days (range 7–7 days, n = 5) compared to the 4–6 days (range 4–7 days) we usually observe with strain FSC033 in multiple mouse strains [17]; in BALB/c mice MTD following i.d. challenge with approximately 10 cfu of FSC033 was consistently <6 days (range 4–6 days; n = 4–6) [11,17–19]. In contrast, MTD following challenge with a similar dose of SCHU S4 was closer to that we have often observed with a virulent type B isolate of F. tularensis [9,11,19].

In an attempt to enhance its virulence, we re-isolated SCHU S4 from the spleen of an infected mouse on our standard cysteine heart agar medium supplemented with 1% hemoglobin and Isovitalex. However, this animal-passaged SCHU S4 did not display enhanced virulence measured as decreased mean time to death in i.d. infected mice (MTD 7 days, range 7–8 days, n = 5). In this regard, FSC033 in now on its fifth animal passage since we initially received it, but this has not affected its virulence measured as MTD following low dose aerosol or i.d. challenge, nor has re-passaging it once again on agar medium. Therefore, we decided to directly compare the virulence of SCHU S4 and FSC033 in naïve mice and mice immunized with the live vaccine strain of the pathogen, F. tularensis LVS.

2.2. Virulence differences between type A F. tularensis strains following i.d. challenge

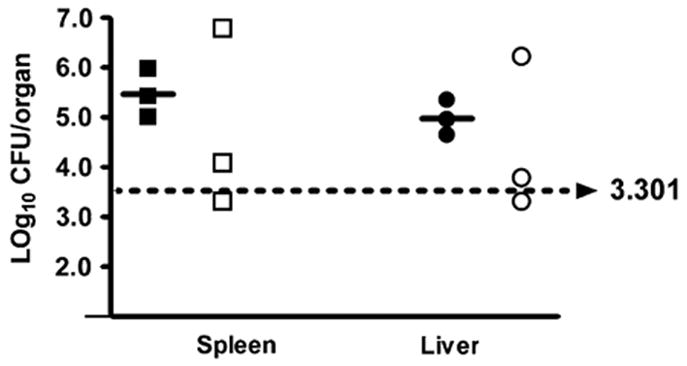

First, we infected naïve BALB/c mice intradermally with ~10 cfu of one or other strain (mice received 17 cfu of FSC237/SCHU S4 or 10 cfu of FSC033, n = 8/group). Some mice from each group (n = 3) were killed on day 3 of infection and bacterial burdens in their livers and spleens determined (Fig. 1). The FSC033 strain of the pathogen was consistently recovered in numbers >104 cfu/organ from the livers and spleens, whereas this was the case in only 1/3 mice infected with SCHU S4 suggesting that the former strain was better able to disseminate from the original inoculation site. When remaining mice were monitored for survival, all five of those infected with FSC033 were dead by day 6, at which time 4/5 mice infected with SCHU S4 were still alive (Fig. 2). Survival differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05 by Logrank test).

Fig. 1.

Dissemination from the skin and growth in the liver and spleen of two type A isolates of F. tularensis. BALB/c mice (n = 3/group) were infected by i.d challenge with 17 cfu of F. tularensis strain SCHU S4 (open symbols) or 10 cfu of strain FSC033 (closed symbols), and bacterial burdens determined in the liver and spleen 3 days later. Bar, mean; dashed line, lower limit of detection.

Fig. 2.

Survival of naïve mice following i.d. challenge with type A strains of F. tularensis. BALB/c mice (n = 5/group) were challenged intradermally with 17 cfu of F. tularensis strain SCHU S4 (open boxes) or 10 cfu of strain FSC033 (closed boxes), and survival was monitored. Survival curves are significantly different (P < 0.005) by Logrank test.

The ability to proliferate during the first few days of infection is a reflection of a pathogen’s ability to survive innate host defences. Thereafter, it has to contend with specific immunity as well. Thus, differences in ability to resist specific immunity could also translate into virulence differences. Next, therefore, we examined the ability of mice immunized with LVS to resist subsequent i.d. challenge with either FSC033 or SCHU S4 In the first instance (Fig. 3) we used C57BL/6 mice that unlike BALB/c mice, remain susceptible to low dose i.d. challenge with FSC033 following immunization with LVS [8]. In each case, mice vaccinated i.d. with 4.2 × 105 cfu of LVS were challenged 61 days later by the same route with ~20 or ~200 cfu of SCHU S4 or FSC033 and their survival was monitored. At the lower dose, 3/4 vaccinated C57BL/6 mice succumbed to challenge with either FSC033 or SCHU S4, but more quickly to the former than the latter. All vaccinated mice died when challenged with ~200 cfu of FSC033, whereas 50% of such mice survived challenge with a similar dose of SCHU S4 for 21 days. However, the observed survival differences were not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Survival of immunized mice following i.d. infection with type A strains of F. tularensis. C57BL/6 mice were immunized by the i.d route with 4.2 × 105 cfu of the live vaccine strain of F. tularensis and were challenged by the same route 61 days later with ~20 (A) or 200 (B) cfu of F. tularensis strain SCHU S4 (open boxes), or FSC033 (closed boxes), and survival was monitored. The observed differences in survival times between the two isolates at both test doses were not significantly different by Logrank test.

Next, we challenged LVS immunized BALB/c mice 74 days later with a large (~2000 cfu) i.d. inoculum of either pathogen (n = 7/group) since we have previously shown that such mice resist such a challenge with FSC033 [8,17–19]. Some mice (n = 3) from each group were killed on day 5 of challenge and F. tularensis burdens in their livers and spleens determined. Evidence that infection had disseminated from the skin was found in 2/3 mice challenged with FSC 033 (3000–6000 cfu recovered from both the spleens and livers), but in none of the mice challenged with SCHU S4 (lower detection limit = 200 cfu) suggesting that LVS immunization imparted better protection against the latter versus the former isolate of the pathogen. In each case 3/4 remaining vaccinated mice survived for 21 days post challenge.

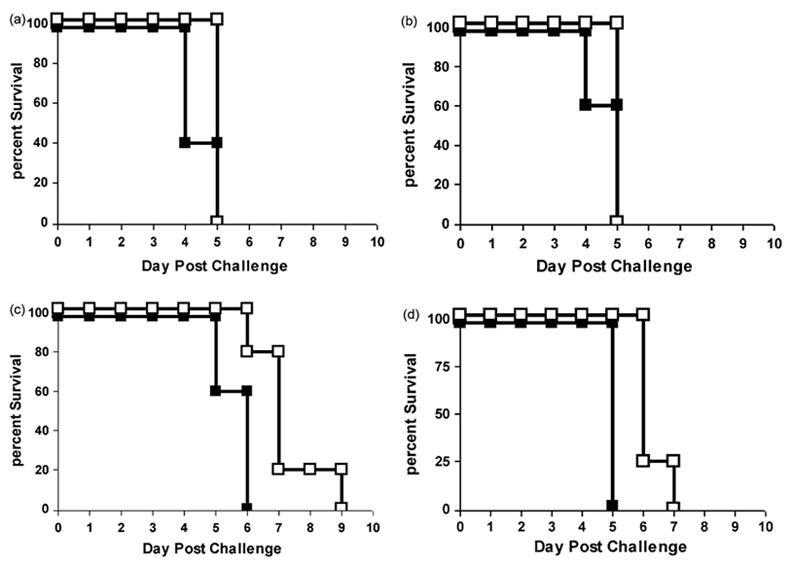

2.3. Virulence differences between type A F. tularensis strains following aerosol challenge

In contrast to the excellent protection i.d. vaccination with LVS confers on BALB/c mice against systemic challenge with FSC033, we have previously shown this regimen elicits very little protection against a low dose (~10 cfu) aerosol challenge with FSC033 [8,17–19]. Therefore, we examined whether mice vaccinated in this way would also remain susceptible to challenge with an aerosol of SCHU S4. The results are presented in Fig. 4. It shows that 60% of naïve BALB/c (Fig. 4a) and 40% of naïve C57BL/6 (Fig. 4b) mice challenged with FSC033 died a day earlier than similar mice challenged with SCHU S4. The former, but not the latter result was statistically significant (P < 0.05). Similarly, most LVS vaccinated BALB/c (Fig. 4c) and C57BL/6 (Fig. 4d) mice challenged with an aerosol of FSC033 succumbed more quickly than mice exposed to an aerosol of SCHU S4, and in each case these differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Survival of naïve and LVS-immunized mice following aerosol challenge with type A strains of F. tularensis. Naïve BALB/c (a) or C57BL/6 (b) mice, or mice immunized with LVS (c and d) were challenged by aerosol with approximately 10 cfu of SCHU S4 (open boxes) or FSC 033 (closed boxes) and survival monitored (n = 5 mice/group). The observed differences in survival times were statistically significant in situations a (P < 0.05), c (P < 0.01), and d (P < 0.005) by Logrank test.

3. Discussion

Historically, the F. tularensis type A strain, SCHU S4, was routinely used in published studies on experimental tularemia. Additionally, it is the only type A strain with a sequenced genome. For these reasons it is natural to assume that SCHU S4 could be used as a standard strain for future infection and immunity studies. However, as far as we can tell, there have been no studies published demonstrating that type A strains of F. tularensis are all equally virulent. Indeed, the reported [20] inhaled LD50 of a streptomycin-resistant variant of SCHU S4 for naïve and LVS-immunized mice (80 and 3500 cfu, respectively), is substantially higher than for type A strain FSC033 (<10 and <10 cfu, respectively) that we have employed in the majority of our published studies to date [8–11,17–19]. Therefore, we were interested in determining whether or not SCHU S4 itself might be less virulent than FSC033 since this could significantly influence the outcome of infection and immunity studies.

Overall, it was clear that both strains of F. tularensis examined were highly virulent for mice challenged by the i.d. or aerosol route and that the LD100 of either strain for naïve mice by either route was <20 cfu. Nevertheless, both naïve and LVS-immunized mice consistently appeared to be more susceptible to infection by strain FSC033 than SCHU S4, and this difference was statistically significant for both naïve and LVS-immunized BALB/c mice challenged by either the i.d route or with an infectious aerosol. In this regard, although only small numbers of mice were used in each experiment in the current study, accumulatively approximately 100 mice were employed. In addition, all our previous experiences involving administration of FSC033 to several thousand mice using similar group sizes have always generated very consistent organ bacterial burdens and survival times [8,9,11,17–19]. Thus, we believe that the deviations from these parameters observed with SCHU S4 are real. However, our results do not necessarily mean that FSC033 is innately more virulent than SCHU S4. Indeed, it is possible that other type A isolates including other subcultures of SCHU S4 with similar or enhanced virulence characteristics compared to FSC033 exist in other laboratories. Nevertheless, the results of the current study do indicate that virulence differences can exist even between highly virulent strains of type A F. tularensis. These virulence differences could significantly impact infection and immunity studies, though this does not appear to be the case for FSC033 versus SCHU S4. Regardless, merely designating the LD50 of the pathogen for mice is not sufficient to rank its relative virulence. On the other hand, median time to death of naïve BALB/c mice challenged intradermally with a low dose of the pathogen does appear to allow subtle virulence distinctions to be made. Therefore, this characteristic should be established before beginning studies with any virulent type A strain of F. tularensis to allow for informed interpretation of the ensuing results. Additionally, our experience with an avirulent type A strain, FSC043, should be a warning to those performing exclusively in vitro studies to ensure that they are dealing with a virulent isolate of the pathogen.

The mechanisms underpinning potential virulence differences between type A strains of F. tularensis were not established by the current study. Previously, others [21,22] have revealed genetic differences between type A strains that allow them to be grouped into two distinct clades designated A.I and A.II. SCHU S4 was formally assigned to the former clade and FSC033 has also been mapped to this clade (Anders Johansson personal communication). However, these genetic studies did not compare the virulence of the type A strains employed. Recently, we have begun to compare the proteomes of in vitro and in vivo grown SCHU S4 and FSC033. Under both growth conditions qualitative and quantitative differences in the proteomes of the two isolates have been observed (unpublished data). We are in the process of determining whether these differences can explain the subtle virulence differences observed herein between the two strains.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Bacteria

F. tularensis LVS was originally obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. (ATCC 29684). The F. tularensis strain FSC033 (subspecies tularensis) was originally isolated from a squirrel in Georgia, USA [21], the strains SCHU S4 (subspecies tularensis), FSC237, and a spontaneous mutant of the SCHU S4 strain, FSC043, are all archived in the Francisella Strain Collection (FSC) of the Swedish Defence Research Agency, Umeå. The passage history of these strains prior to their use in the present study is unknown, but presumed to be highly checkered. For the present study, stock cultures of all strains were prepared by growing them as confluent lawns on cysteine heart agar supplemented with 1% (w/v) hemoglobin (CHAH). Bacteria were harvested after 48–72 h incubation at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 into freezing medium consisting of modified Mueller Hinton broth [23] containing 10% w/v sucrose. Stocks were aliquoted in a volume of 1 ml and stored at −80 °C.

4.2. Mice and bacterial challenges

Specific-pathogen-free female BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles Rivers Laboratories (St Constant, Que.), and entered experiments when they were 8–12-weeks old. Mice were maintained and used in accordance with the recommendations of the Canadian Council on Animal Care Guide to the Care and Use of Experimental Animals. For aerosol exposure, thawed F. tularensis stocks were diluted in Mueller Hinton broth containing 20% (w/v) glycerol; for i.d. inoculations stocks were diluted in sterile saline. Actual inoculum concentrations were determined by plating 10-fold serial dilutions on CHAH. Colonies were counted after 48–72 h of incubation at 37 °C. Intradermal inocula (50 μl/mouse) were injected into a fold of skin in the shaved mid-belly. Aerosols of F. tularensis strains were generated with a Lovelace nebuliser operating at a pressure of 40 p.s.i. to produce particles in the 4–6 μm range required for inhalation and retention in the alveoli. Mice were exposed to these aerosols for 7 min using a customized commercial nose-only exposure apparatus (In-tox Products, Albuquerque, NM). Exposures were performed first with SCHU S4 then immediately afterwards with FSC033 using an identical nebulizer inoculum of 4 × 108 cfu/ml of the respective pathogen. In our hands this nebulizer concentration of FSC033 routinely results in approximately 10 cfu of the pathogen being retained in the lungs. In each experiment, the generated aerosol was delivered to the exposure ports at a flow rate of 15 l/min, and at 70% relative humidity. Approximately, 0.3 ml of inoculum was consumed/aerosolization. The viability of the F. tularensis in the nebulizer was similar before and after aerosolization. Aerosol exposures were performed in a federally-licensed small animal containment level 3 facility. At various times post-exposure, some mice were killed, and their livers and spleens removed, diced, homogenized, and plated.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly funded by grants AI48474 and AI059064 from the National Institutes of Health, USA.

References

- 1.Ellis J, Oyston PCF, Green M, Titball RW. Tularemia. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:631–46. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.4.631-646.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sjostedt A. Virulence determinants and protective antigens of Francisella tularensis. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2003;6:66–71. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(03)00002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saslaw S, Eigelsbach HT, Wilson HE, Prior JA, Carhart S. Tularemia vaccine study. I. Intracutaneous challenge. Arch Int Med. 1961;107:689–701. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1961.03620050055006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saslaw S, Eigelsbach HT, Prior JA, Wilson HE, Carhart S. Tularemia vaccine study II. Respiratory challenge Arch Int Med. 1961;107:702–14. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1961.03620050068007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eigelsbach HT, Downs CM. Prophylactic effectiveness of live and killed tularemia vaccines. I. Production of vaccine and evaluation in the white mouse and guinea pig. J Immunol. 1961;87:415–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conlan JW. Vaccines against Francisella tularensis—past, present and future. Expert Rev Vaccine. 2004;3:307–14. doi: 10.1586/14760584.3.3.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elkins KL, Cowley SC, Bosio CM. Innate and adaptive immune responses to an intracellular bacterium, Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain. Microbes Infect. 2003;5:135–42. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(02)00084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen W, Shen H, Webb A, KuoLee R, Conlan JW. Tularemia in BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice vaccinated with Francisella tularensis LVS and challenged intradermally, or by aerosol with virulent isolates of the pathogen; protection varies depending on pathogen virulence, route of exposure, and host genetic background. Vaccine. 2003;21:3690–700. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00386-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen W, KuoLee R, Shen H, Conlan JW. Susceptibility of immuno-deficient mice to aerosol and systemic infection with virulent strains of Francisella tularensis. Microb Pathog. 2004;36:311–8. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conlan JW, Shen H, Webb A, Perry MB. Mice vaccinated with the O-antigen of Francisella tularensis—LVS lipopolysaccharide conjugate to bovine serum albumin develop varying degrees of protective immunity against systemic or aerosol challenge with virulent type A and type B strains of the pathogen. Vaccine. 2002;20:3465–71. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00345-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conlan JW, Chen W, Shen H, Webb A, KuoLee R. Experimental tularemia in mice challenged by aerosol or intradermally with virulent strains of Francisella tularensis: Bacteriologic and histopathologic studies. Microb Pathog. 2003;34:239–48. doi: 10.1016/s0882-4010(03)00046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fulop M, Mastroeni P, Green M, Titball RW. Role of antibody to lipopolysaccharide in protection against low- and high-virulence strains of Francisella tularensis. Vaccine. 2001;19:4465–72. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(01)00189-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dennis DT, Inglesby TV, Henderson DA, Bartlett JG, Ascher MS, Eitzen E, et al. Tularemia as a biological weapon. Medical and Public Health Management. J Am Med Assoc. 2001;285:2763–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.21.2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eigelsbach HT, Braun W, Herring RD. Studies on the variation of Bacterium tularense. J Bacteriol. 1951;61:557–69. doi: 10.1128/jb.61.5.557-569.1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larsson P, Oyston PC, Chain P, Chu MC, Duffield M, Fuxelius HH, et al. The complete genome sequence of Francisella tularensis, the causative agent of tularemia. Nat Genet. 2005;37:153–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Twine SM, Bystrom M, Chen W, Forsman M, Golovliev IR, Johansson A, et al. A mutant of Francisella tularensis strain SCHU S4 lacking the ability to express a 58 kDa protein is attenuated for virulence and an effective live vaccine. Infect Immun. 2005;73:8345–52. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.12.8345-8352.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shen H, Chen W, Conlan JW. Susceptibility of various mouse strains to systemically- or aerosol-initiated tularemia by virulent type A Francisella tularensis before and after immunization with the attenuated live vaccine strain of the pathogen. Vaccine. 2004;22:2116–21. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conlan JW, Shen H, KuoLee R, Zhao X, Chen W. Aerosol-, but not intradermal-immunization with the live vaccine strain of Francisella tularensis protects mice against subsequent aerosol challenge with a highly virulent type A strain of the pathogen by an αβ T cell-and interferon gamma-dependent mechanism. Vaccine. 2005;23:2477–85. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen H, Chen W, Conlan JW. Mice sublethally infected with Francisella novicida U112 develop only marginal protective immunity against systemic or aerosol challenge with virulent type A or B strains of F. tularensis. Microb Pathog. 2004;37:107–10. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hodge FA, Leif WR, Silverman MS. Susceptibility to infection with Pasteurella tularensis and the immune response of mice exposed to continuous low dose rate gamma radiation. Nat Radiol Def Lab Trans. 1968;68–85:1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johansson A, Ibrahim A, Goransson I, Eriksson U, Gurycova D, Clarridge JE, III, et al. Evaluation of PCR-based methods for discrimination of Francisella species and subspecies and development of a specific PCR that distinguishes the two major subspecies of Fransicella tularensis. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:4180–5. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.11.4180-4185.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johansson A, Farlow J, Larsson P, Dukerich M, Chambers E, Bystrom M, et al. Worldwide genetic relationships among Francisella tularensis isolates determined by multiple-locus variable-nimber tandem repeat analysis. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:5808–18. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.17.5808-5818.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baker CN, Hollis DG, Thornsberry C. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Francisella tularensis with a modified Mueller–Hinton broth. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;22:212–5. doi: 10.1128/jcm.22.2.212-215.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]