Abstract

The yeast Sir2 protein, required for transcriptional silencing, has an NAD+-dependent histone deacetylase (HDA) activity. Yeast extracts contain a NAD+-dependent HDA activity that is eliminated in a yeast strain from which SIR2 and its four homologs have been deleted. This HDA activity is also displayed by purified yeast Sir2p and homologous Archaeal, eubacterial, and human proteins, and depends completely on NAD+ in all species tested. The yeast NPT1 gene, encoding an important NAD+ synthesis enzyme, is required for rDNA and telomeric silencing and contributes to silencing of the HM loci. Null mutants in this gene have significantly reduced intracellular NAD+ concentrations and have phenotypes similar to sir2 null mutants. Surprisingly, yeast from which all five SIR2 homologs have been deleted have relatively normal bulk histone acetylation levels. The evolutionary conservation of this regulated activity suggests that the Sir2 protein family represents a set of effector proteins in an evolutionarily conserved signal transduction pathway that monitors cellular energy and redox states.

Transcriptional silencing is a regulatory mechanism that results in the inactivation of large blocks of chromosomes via an altered chromatin structure. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, silencing is observed at the HM silent mating type loci (reviewed in ref. 1), telomeres (2), and at the rDNA locus (3, 4). Although a different subset of proteins is required for silencing at each of the three loci, all types of silencing require Sir2p (3, 5). The Sir2 family of proteins is highly conserved and found in Archaea, eubacteria, and metazoa (6–9). A recent study showed that yeast and mouse Sir2p have NAD+-dependent HDA activity on histone peptides specific for Lys-16 of histone H4 (10), an important residue for silencing (11–13). Earlier work had suggested that Sir2p might have HDA activity. Acetylated histones were inefficiently immunoprecipitated from the silent mating type (HM) loci relative to the expressed mating type (MAT) locus, and overexpression of Sir2p led to changes in levels of bulk histone acetylation (14, 15). Other recent papers demonstrated a phosphotransferase activity for Sir2p, with NAD+ as the source of phosphate and a variety of proteins implicated as targets of ADP ribosylation (9, 16). A sir2 missense mutation that destroys this in vitro activity also destroys silencing in vivo. These results suggest that the Sir2p family is a group of ADP-ribosyl transferases (ARTs).

We show here that Archaeal, eubacterial, and human Sir2 proteins, like Sir2p, have potent NAD+-dependent HDA activity in vitro. The importance of NAD+ to the in vivo activity of Sir2p is underscored by our finding that mutations in the S. cerevisiae NPT1 gene lead to severe silencing defects. NPT1 encodes a nicotinate phosphoribosyltransferase, required for NAD+ synthesis through a salvage pathway. Intracellular NAD+ levels are significantly lower in npt1 null mutants than in the wild type, providing independent evidence that NAD+ is critical for silencing in vivo. In addition, extracts from wild-type yeast cells contain a readily detectable NAD+-dependent HDA activity. In extracts made from yeast lacking all five SIR2-like genes, no HDA activity is detected. Finally, we examined the in vivo acetylation state of histones in the wild-type and mutant strains. Surprisingly, the mutant strain has levels of bulk histone acetylation similar to the wild type, suggesting that histones might not be the in vivo target of the Sir2p family. This, together with the fact that bacteria do not encode histones with N-terminal tails (prominent sites of protein acetylation in eukaryotes), indicates that Sir2p belongs to a family of NAD+-dependent protein deacetylases that may have other targets in addition to histone tails.

Materials and Methods

Strains and Mutagenesis.

Yeast strains are described in the supplementary materials (see www.pnas.org). Yeast media were previously described (3, 17, 18). Strains M217 (npt1–1) and M269 (npt1–2) were isolated from a genetic screen designed to identify mutations that affect rDNA silencing (19). M217 and M269 were selected as loss of rDNA silencing (lrs2) mutations that activated all three reporters. M217 and M269 had transposons inserted between codons 378–379 of NPT1 (npt1–1) and codons 35–36 (npt1–2), respectively. Whereas the npt1–1 mutation was phenotypically indistinguishable from a constructed null mutation, the npt1–2 mutant showed an intermediate phenotype, with only partial loss of rDNA silencing and a modest increase in rDNA recombination. NPT1 was deleted by using one-step PCR-mediated gene replacement (19).

Yeast Assays.

Two different rDNA silencing assays were used. To assay for silencing of mURA3 in the rDNA, strains were grown on yeast extract/peptone/dextrose medium, resuspended in sterile water, normalized to an A600 of 0.5, and then serially diluted 5-fold. Five microliters of each dilution was spotted onto synthetic complete (SC) and SC medium lacking uracil. Plates were incubated at 30°C for 2–4 days. The MET15 colony color rDNA silencing assay was as described (3).

Two different telomeric position effect (TPE) assays were used to assay the effects of npt1 deletion. To measure silencing of URA3 adjacent to the chromosome VIIL telomere, cells were serially diluted in 5-fold increments and spotted, as above, but on SC and SC+ 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-Foa) medium. Loss of silencing activates URA3 expression, preventing growth on 5-Foa. The colony color TPE assay is based on the ADE2 reporter integrated at the chromosome VR telomere. Reporter strains are plated onto SC medium containing limiting amounts of adenine. The colonies are red if ADE2 is silenced and white if it is not; epigenetic switching results in sectoring (2). The npt1 colonies were white overall, with only a thin rim of tiny red sectors near the outer edges of the colony, indicating a major reduction in TPE. The HMR silencing assay was performed by measuring the growth capacity of a strain containing TRP1 integrated into a weakened HMR locus deleted for the ARS element (A) of the E silencer (20). Cells were serially diluted on either SC or SC-Trp and grown at 30°C for 1–4 days. Growth on SC-Trp medium indicates loss of silencing. For measurements of intracellular NAD+, cells were grown in 100 ml yeast extract/peptone/dextrose medium and collected at A600 = 1. NAD+ was extracted and measured as described (21, 22).

HDA Activity Assay, Extract Preparation, and Protein Purification.

Immature chicken erythrocytes obtained as described (23) were labeled with [3H]acetic acid, and the histones were isolated (24). For the HDA assays, 20 μl (18 μg; 18,000 cpm) of [3H]acetylated histone was combined with ≈1 μg Sir2p (or other purified protein) or 300 μg of yeast whole-cell protein extract in a 100-μl reaction. The standard buffer used for the reactions consisted of 25 mM Tris⋅Cl, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, and 200 μM NAD+. All reactions were incubated at 30°C except CobB reactions (37°C) and Sir2AF reactions (55°C). Reactions were stopped by the addition of 36 μl 1 N HCl and 0.4 N acetic acid. Released acetyl groups were extracted by adding 800 μl ethyl acetate, vortexing 20 s, and putting on ice for 10 min. After a 5-min centrifugation in a microfuge, 600 μl was combined with 3 ml scintillation fluid. This reaction was scaled down 10-fold for certain experiments.

Extracts were prepared from 100 ml cultures grown in yeast extract/peptone/dextrose at 30°C and collected at an A600 of 1.0. The cells were washed with water and resuspended in 250 μl breaking buffer (100 mM Tris⋅Cl, pH 8.0/200 mM NaCl/1 mM EDTA/0.5 mM EDTA/0.5 mM PMSF/10% glycerol) to which a protease inhibitor mixture (25) was added. Cells were broken by using a mini-Bead-Beater three times for 45 s with 0.4 g glass beads. The supernatant was pooled with a 250-μl wash of the beads, and the protein concentration was determined by using the Bio-Rad Bradford protein assay with BSA as a standard. Sir2p and its homologs were expressed from Pharmacia pGEX plasmids, and the fusion proteins were purified by using methods described by the manufacturer. Sir2AF was produced as a native protein in Escherichia coli in pET11A and purified by heat denaturation and Q-Sepharose Fast Flow chromatography. Salmonella CobB was prepared as described (8).

Yeast Histone Labeling and Electrophoresis.

Spheroplasts were prepared and resuspended in buffer containing cycloheximide and [3H]acetate, as described in detail in the supplemental material (see www.pnas.org). After labeling, nuclei were isolated, and acid soluble nuclear proteins were extracted. Acid-insoluble proteins were collected and purified. Acetic acid-urea-Triton gels (14 cm) were stained with Coomassie blue R (Sigma) and prepared for fluorography after the Enhance (ICN) protocol.

The quintuple mutant strains grow somewhat more slowly than wild type. However, the cells were harvested at similar densities (YCB180, wild type, A600 of 0.94; YCB496, mutant, A600 of 0.0.62; YCB497, mutant, A600 of 0.92) and were spheroplasted to similar extents: 70% (YCB496 and 497), and 100% (YCB180). Total counts incorporated were also similar: 30,000 (YCB180), 18,000 (YCB496) and 13,000 (YCB497). Thus differences in the total incorporated acetate between the wild-type and mutant strains were about 2-fold.

Results

NAD+-Dependent Histone Deacetylase Activity in Yeast Extracts.

We carried out systematic gene disruptions of all five genes encoding Sir2-like proteins in S. cerevisiae, SIR2, HST1, HST2, HST3, and HST4. In the YPH499/500 strain background, all five genes could be disrupted without compromising viability (C.B.B., I.C., E. Caputo, J.S.S. & J.D.B., unpublished observations). The sir2 hst1 hst2 hst3 hst4 quintuple mutant grows well enough to prepare extracts for biochemical analysis. We investigated whether extracts from the mutant cells had HDA activity. We used purified native chicken histones labeled biosynthetically with [3H]acetate as a HDA substrate and monitored the release of free acetate. No difference in HDA activity was observed between nuclear extracts of wild-type and quintuple-mutant cells by using previously described methods (26, 27). The Rpd3 family of HDAs (28, 29) was presumably responsible for the bulk of activity detected under these conditions, because Sir2p requires NAD+ for its HDA activity (10). Indeed, when crude whole-cell extracts were tested in the presence of NAD+, a robust HDA activity was readily detected (Fig. 1A). By using conditions reported as optimal for Sir2p's ADP-ribosyltransferase activity with 200 μM NAD+, there was little detectable HDA activity in the quintuple mutant, whereas the wild-type extract had a robust activity (Fig. 1A). Under these conditions, the activity in the yeast extracts was linear for many hours. After 8 h, approximately 20% of the acetate label was released from 18 μg of histones. Because no activity is detected in the absence of NAD+, we assume that Rpd3 HDA is absent from our extracts and/or inactive under these conditions.

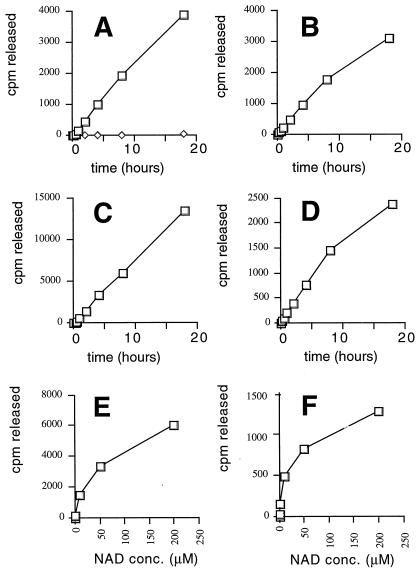

Figure 1.

NAD+-dependent HDA activity in yeast extracts and purified proteins. Time courses of the reactions done in parallel are shown (A–D). (A) Wild-type (strain YCB180; squares) and quintuple mutant (strain YCB496; sir2 hst1 hst2 hst3 hst4; diamonds) yeast extracts were assayed for deacetylase activity by using a [3H]acetate-labeled chicken histone substrate. Purified Sir2ps were also assayed: (B) GST-Sir2p protein from S. cerevisiae, 30°C; (C) Sir2AF from A. fulgidus, 55°C; (D) GST-Sir2A protein from human, 30°C. GST protein purified in parallel with the GST-Sir2 and GST-Sir2A was completely inactive in several experiments. By using 2 μg GST protein in a 4-h reaction, 7 and 8 cpm were released; with 4, 8, and 16 μg protein 8, 14, and 17 cpm were released, respectively; the activities were all NAD+ dependent. With CobB, 33% of the label was released by 1 μg protein after 4 h at 37°C in the presence of NAD+ and 0.9% was released in the absence of NAD+, by using a 10-fold scaled-down reaction, indicating that CobB is approximately as active as Sir2AF. E and F show the effect of NAD+ titrations on the Sir2AF and human Sir2A proteins, respectively. By fitting these data to a hyperbola, we estimate that the NAD+ concentrations yielding half-maximal activity are 55 ± 12 μM for Sir2AF and 23 ± 8 μM for human Sir2A.

We investigated the activity of NAD+-dependent HDA activity in yeast bearing individual sir2 and hst mutations. Activity levels similar to wild type were observed in all single mutants except for the hst2 mutant extract, which was reduced to near background levels, similar to the sir2 hst1 hst2 hst3 hst4 quintuple mutant extract (Fig. 2). Under these extraction and assay conditions, the Hst2p protein apparently contributes most of the in vitro NAD+-dependent HDA activity in the yeast extract.

Figure 2.

NAD+-dependent histone deacetylase activity in extracts prepared from individual mutants, assayed for 4 h at 30°C. We assayed extracts prepared from the indicated mutants in the presence or absence of 200 μM NAD+. The amount of NAD+-dependent activity is plotted. Experiments were performed at least in triplicate. Strains used were YCB180 (wild type), YCB178 (sir2), YCB232 (hst1), YCB172 (hst2), YCB394 (hst3), YCB526 (hst4), and YCB234 (hst1 hst2).

Activity of Purified Proteins.

The HDA activity of purified Sir2-like proteins was assayed by using proteins from bacteria, yeast, and humans. Yeast Sir2p, Salmonella typhimurium CobB, a homolog from the archaebacterium Archaeoglobus fulgidus (Sir2AF), and human Sir2A (30) were purified from overexpressing bacteria. The yeast and human proteins were expressed as GST fusion proteins, and the bacterial enzymes were expressed in native form. All four purified proteins had robust in vitro activity, whereas GST protein purified in parallel was completely inactive (Fig. 1 B–D). The Sir2AF enzyme was the most active of the four, as assayed at 55°C. All three enzymes tested in time courses were active for at least 20 h. By this time, Sir2AF had removed >50% of the acetate from the histones. The reactions were carried out with at least a 10-fold molar excess of substrate over enzyme, showing that the HDA activity on native histones is enzymatic. All four enzymes required NAD+ for activity. An NAD+ titration showed that both the human and Archaeoglobus enzymes had strikingly similar NAD+ requirements (Fig. 1 E–F).

NPT1, a Gene Required for rDNA Silencing and Control of rDNA Recombination.

We recently described a screen designed to isolate mutations affecting rDNA silencing. In this screen, three reporter genes, mURA3, HIS3, and MET15, were inserted into different rDNA repeats (19). A strain with all three rDNA silencing reporter genes was mutagenized with a marked transposon (19, 31). Mutants with loss of rDNA silencing were identified. Two such mutations fell in the LRS2 gene, also known as NPT1 (YOR209C). This gene encodes a protein homologous to the bacterial nicotinate phosphoribosyltransferase (NaPRTase), a key enzyme in NAD+ biosynthesis (32).

One of the mutations, npt1–1, reduced rDNA silencing to a similar extent as a sir2Δ mutation at both the mURA3 (Fig. 3A) and MET15 (Fig. 3B) reporters. In a quantitative assay done by using the mURA3 reporter, we saw approximately 50-fold more Ura+ colonies in the npt1–1 mutant relative to the wild type, similar to the results with a sir2Δ mutant, indicating that NPT1 is as important for rDNA silencing as SIR2. Many lrs mutations affect rDNA silencing and rDNA recombination, both of which are presumably regulated by a similar chromatin structure. Like sir2Δ mutants, and like a constructed npt1Δ:kanMX null allele, the npt1–1 mutant colonies displayed a greatly increased frequency of recombination in the rDNA, monitored by the frequency of black sectors (Fig. 3B) relative to wild-type colonies. The growth properties, colony color, and sectoring pattern of npt1–1 and npt1Δ∷kanMX are virtually indistinguishable from that of sir2 null mutants. Deletion of NPT1 had no effect on expression of Ty1-mURA3 integrated at a non-rDNA location; both NPT1+ and npt1 strains bearing this insertion grew far more slowly than URA3+ strains. This experiment shows that the effect of npt1 mutations is specific to the rDNA locus and does not affect the mURA3 reporter generally. We showed that npt1 sir2 double mutants had silencing phenotypes similar to sir2 mutants, indicating the two mutations are in the same epistasis group. Importantly, the npt1 null mutants grew almost as fast as the wild type (Fig. 3), suggesting that general cellular physiology was only minimally impaired. This was true in three different strain backgrounds (data not shown).

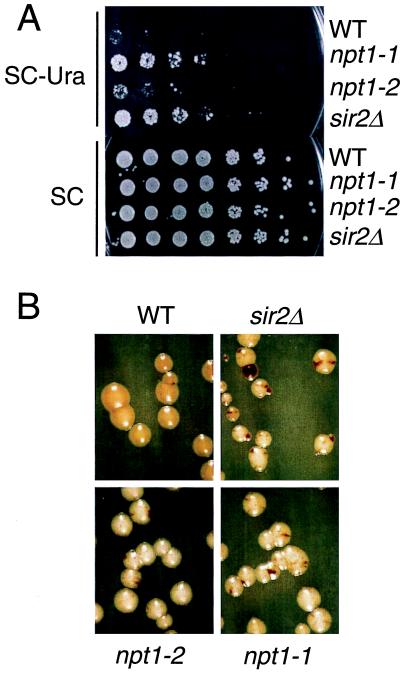

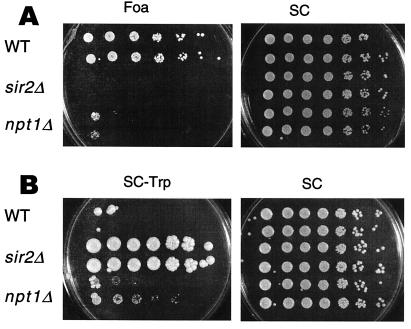

Figure 3.

NPT1 is required for rDNA silencing and rDNA recombinational stability. (A) Silencing of mURA3 reporter. Strains JS311 (WT), M217 (npt1–1), M269 (npt1–2), and JS566 (sir2Δ) were spotted onto SC medium lacking uracil to measure silencing or nonselective SC medium as a growth control. (B) Silencing of MET15 reporter. Strains are as in A, except the sir2Δ strain is JS218.

NPT1 Is Generally Important for Silencing.

We tested whether the npt1 mutations affected other forms of silencing by introducing the npt1 null mutation into a strain bearing a telomeric URA3 reporter. The npt1 mutant lost telomeric position effect to nearly the same degree as sir mutants (Fig. 4A); similar results were obtained with a telomeric ADE2 reporter (not shown). Unlike sir2 mutants, npt1 mutants mated normally, indicating that if silencing function was lost at the HM loci, the loss was only partial. We therefore introduced the npt1null allele into a strain in which TRP1 was inserted at HMR. The npt1 mutants grew very slowly on medium lacking tryptophan, forming tiny colonies, whereas the wild-type strain did not grow (Fig. 4B). In contrast, sir2Δ mutants grew robustly. These results indicate that NPT1 functions in, but is not essential for, silencing at HMR.

Figure 4.

Effects of npt1 mutation on telomeric and HMR silencing. (A) Silencing of a telomeric URA3 was analyzed in strains YCB647 (WT), YCB652 (sir2Δ), and JS641 (npt1Δ). Each strain was grown on 5-fluoroorotic acid (Foa) or SC medium. Growth on Foa indicates silencing. The npt1 mutant shows a ≈3,000-fold reduction in the frequency of FoaR colonies relative to wild-type cells. In the sir2 mutant, the frequency was reduced >15,000-fold relative to wild type. (B) Silencing of a TRP1 reporter gene integrated at HMRΔA was analyzed in YL559 (WT), MC119 (sir2Δ), JS643 (npt1Δ), and JS644 (npt1Δ). Strains were spotted on SC-Trp and SC medium. Growth on the SC-Trp medium indicates loss of silencing.

NPT1 Determines Intracellular NAD+ Concentrations.

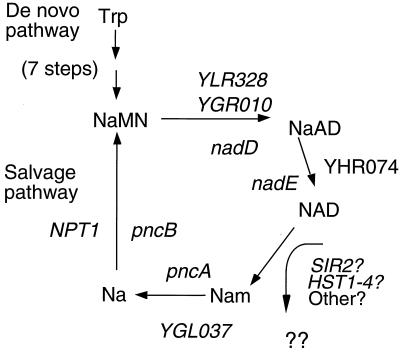

Two separate pathways for NAD+ synthesis have been shown in pro- and eukaryotes, the de novo and salvage pathways. The latter culminates with NaMN synthesis by NaPRTase. A fairly complete understanding of the pathways, enzymes, and genes involved in NAD+ synthesis is available for Salmonella, although the major source of NAD+ breakdown and hence flux through the salvage pathway in both bacteria and eukaryotes remains unidentified (33). NaPRTase performs the last step in the salvage pathway before it converges with the final steps of the de novo pathway (Fig. 5). We note significant homologies between yeast and bacterial ORFs whose products carry out specific steps in NAD+ biosynthesis. On the basis of these homologies, we outline a scheme for the enzymes responsible for various steps in NAD+ metabolism in yeast and bacteria (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

An NAD+ salvage pathway important for transcriptional silencing in yeast. The diagram indicates the enzymatic steps known to occur in synthesis of NAD+. For the part of the pathway conserved in Salmonella, the names of the relevant genes proposed or known to carry out each step are given in lowercase letters inside the circle, and the relevant yeast ORFs are written in uppercase. NaMN, nicotinic acid mononucleotide; NaAD, desamido NAD+; Nam, nicotinamide; Na, nicotinic acid.

The role of NPT1 in silencing is probably to maintain high levels of intracellular NAD+. If NAD+ is converted to nicotinamide released via various metabolic reactions, potentially including ADP-ribosylation reactions carried out by Sir2p, its homologs and other NAD+-using enzymes, we reasoned that a salvage pathway may be required to maintain adequate NAD+ concentrations in the cell. We measured intracellular NAD+ in wild-type and npt1 mutant yeast cells and found that npt1 mutants contained 2.6-fold less NAD+ than the wild type (Table 1). The fact that this significant drop in intracellular NAD+ has only negligible effects on general cell growth and vigor in npt1 mutants contrasts with striking and specific silencing defects. High levels of NAD+ may be required to maintain silencing but not other aspects of cellular metabolism.

Table 1.

Intracellular NAD+ concentrations

| Strain no. | Relevant genotype | NAD+ concentration (× 10−4 pmol/cell) ± SD

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1 | Experiment 2 | Experiment 3 | ||

| JS325 | NPT1 | 1.52 ± 0.37 | 1.42 ± 0.23 | 1.59 ± 0.76 |

| JS596 | npt1Δ∷kanMX | 0.60 ± 0.02 | 0.53 ± 0.05 | 0.46 ± 0.12 |

| JS597 | npt1Δ∷kanMX | 0.63 ± 0.12 | 0.51 ± 0.04 | 0.83 ± 0.27 |

| Fold reduction | In npt1Δ∷kanMX | 2.47 | 2.73 | 2.47 |

Data are from three independent NAD+ extractions, and the numbers represent the mean of at least three independent measurements. JS596 and 597 are two independent isolates.

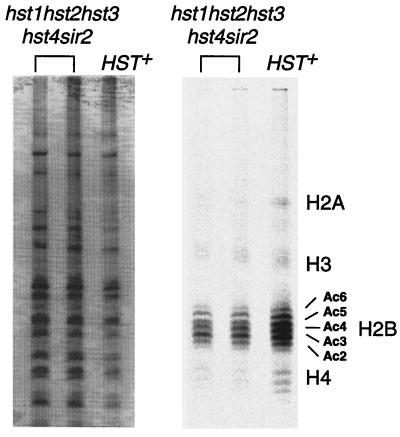

Analysis of Bulk Histone Acetylation in Vivo.

We analyzed the wild-type and quintuple mutant strains for extent of histone acetylation in vivo. If Sir2p and its homologs represent a major family of HDAs in vivo, an effect on bulk histone acetylation levels is expected. Histones would be expected to be hyperacetylated in quintuple mutant strains. To evaluate whether this was the case, we labeled wild-type and mutant yeast spheroplasts with [3H]acetate in the presence of cycloheximide. We then extracted histones, loaded equal amounts of counts from mutant and wild-type strains, and separated them by charge on acid-urea Triton gels. The gel was then stained for total protein, and fluorography was performed to visualize the acetylated histone bands. If the Sir2 and Hst proteins had deacetylated a majority of yeast histones, we would expect to observe histone hyperacetylation in the quintuple mutant. Instead, we observed a modest reduction in the amount of acetylated histones in the quintuple mutant relative to the wild type, even though the amount of total protein loaded on the gel was somewhat greater for the mutant cells (Fig. 6). The slight reduction probably reflects the ≈2-fold lower efficiency of labeling of the mutant cells. Several forms of acetylated histone are easily seen for histone H2B; some subtle differences in the distributions of acetylated species are observed. Specifically, the band corresponding to triply acetylated H2B is more abundant in the mutant than in the wild type. However, the overall pattern of histone acetylation is remarkably similar between mutant and wild type.

Figure 6.

Histone acetylation in vivo in wild-type and mutant strains. Histones were extracted from yeast spheroplasts labeled with [3H]acetic acid. The acid extracts were then separated electrophoretically on acid-urea-Triton gels. (Left) Protein samples stained for total protein content by Coomassie brilliant blue staining. (Right) Fluorograph of the gel, after a 6-month exposure at −70°C. Strains tested were YCB496, 497 (mutant), and 180 (wild type).

Discussion

What are the Sir2p deacetylase substrates? We have shown that the NAD+-dependent HDA activity of Sir2p is conserved in homologs from eubacteria, Archaea, and humans. The high degree of phylogenetic conservation of Sir2-like proteins from diverse species has always suggested functional conservation at the biochemical level. We have shown that Sir2-like proteins from bacterial, yeast, and human cells can efficiently remove acetyl groups from histones in vitro. This in vitro reaction absolutely requires NAD+ in all five species of protein tested.

The presence of Sir2p homologs in eubacteria suggests that if these enzymes function as protein deacetylases or ADP-ribosyl transferases, or both, the absence of histones in these bacteria means that these enzymes must have other targets in prokaryotes. Even Archaea have histones substantially dissimilar to those of eukaryotes; they contain a single species of histone lacking the N-terminal tail that is acetylated in eukaryotic histones. This suggests that the Sir2p family of protein deacetylases may have in vivo targets other than histones.

Surprisingly, the quintuple knockout mutant sir2 hst1 hst2 hst3 hst4 has modestly reduced histone acetylation levels—the opposite of what is predicted for a deacetylation defect. There are two possible interpretations of this. The first is that histones are indeed a relevant in vivo target of Sir2-like proteins; if this is true, then the fraction of total histones subject to deacetylation by Sir2p and the Hst proteins must be a relatively small proportion of the total. This could be because there are two well-known active HDAs in yeast that may affect the bulk of the deacetylation (29). Also, Sir2p's HDA activity is specific for histone H4 residue K16 (10), a residue implicated in silencing. The second possibility is that histones are not an in vivo substrate, and that some other molecule associated with silent chromatin is the relevant target of Sir2p. Our current data are insufficient to choose between these possibilities. Whichever is correct, it is likely that the Sir2p family of proteins will have nonhistone substrates, at least in bacteria, if not in other organisms. Human Sir2A and a trypanosomal Sir2p homolog are both cytoplasmically localized (34, 35), suggesting nonchromatin targets for these proteins. Similarly, Hst2p, the yeast homolog most closely related to human Sir2A, is located in the yeast cytoplasm, and hst2 mutants have no detectable silencing defect. These cytoplasmic Sir2p homologs could have nonhistone substrates in vivo. Despite the cytoplasmic localization of these proteins, we have shown that both Hst2p and human Sir2A have in vitro HDA activity. Additional data on the substrate specificities of these enzymes should help to resolve this important issue.

A Critical Role for NAD+ in Silencing.

A genetic screen designed to identify yeast genes required for rDNA silencing identified a gene required for maintenance of intracellular NAD+ levels, thereby providing independent evidence for the in vivo role of NAD+-dependent Sir2p activity. NPT1 encodes an enzyme with NaPRTase activity that salvages the nicotinate moiety from NAD+ metabolites in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes. NAD+ turnover is quite rapid in both bacteria and eukaryotic cells, with half-lives of 25–90 min (33, 36). Yeast npt1 null mutants have 2.6-fold lower intracellular NAD+ levels than wild type, consistent with a role for NPT1 in maintaining intracellular NAD+. Because most intracellular NAD+ is enzyme bound, the concentration of free intracellular NAD+ is likely considerably lower than our measurement. The essential roles of NAD+ and its derivatives in electron transport and redox reactions are well known. Because npt1 mutants do not have general growth defects, Sir2-like proteins may have lower affinities for NAD+ than metabolic enzymes.

The tightest form of silencing, occurring at the HM loci, is least sensitive to npt1 mutations and hence to intracellular NAD+ levels. The multiply redundant nature of silencing at the HM loci may be responsible for their relative immunity to a drop in NAD+ (1). Telomeric silencing, which silences reporters less tightly than the HM loci, is much more sensitive to npt1 mutations. The rDNA locus, which is the least tightly silenced locus and requires only Sir2p for silencing, is the most sensitive to npt1 mutations; it is also the most sensitive to Sir2p protein levels (5). Thus rDNA, comprising about 10% of the genome, may be much more dependent on Sir2p's enzymatic activities than are other forms of silencing. Sir2p interacts with Sir4p at HM loci and at telomeres (37, 38), but with Net1p at the rDNA (39, 40). The affinity of Sir2ps for NAD+ may be modulated by interactions with specific partner proteins in the discrete silencing complexes found in the three different classes of silenced domains in the genome. Alternatively, NAD+ concentrations could vary within the cell or even among different nuclear subcompartments. Variations in local intranuclear NAD+ concentration could underlie the differential sensitivity of the various forms of silencing to npt1 mutations.

Sir2p-Deacetylase and ADP-Ribosyl Transferase?

Two recent papers reported that yeast Sir2p, E. coli CobB protein, and human Sir2A protein can transfer (31) P label from NAD+ to substrate proteins, including BSA, histones, and, in the case of Sir2p, to itself (9, 16). The CobB protein was also reported to transfer label from NAD+ to a small molecule, 5,6-dimethylbenzimidazole. Importantly, mutagenesis of the highly conserved H364 residue in yeast Sir2p eliminated this activity and led to a complete loss of transcriptional silencing. Furthermore, antibodies raised against mono-ADP-ribose reacted with the modified substrates, suggesting that Sir2p had mono-ADP-ribosylation activity (16). These results support the possibility that Sir2ps contain an ART activity. However, this activity is not very strong, nor does the reaction appear very specific, as the nonphysiologic substrate, BSA, is as good a substrate as the more relevant histones. The sir2H364 mutation eliminates both the ART and HDA activities as well as silencing (10, 16). However, the sir2G270 mutation reduces (but does not eliminate) ART activity and has only modest effects of silencing and HDA activity, suggesting the two activities are at least partially separable.

We have recently shown that, like cobB, both yeast and human Sir2ps can complement the Salmonella cobB cobT cobalamin auxotrophy in vivo, indicating that this prokaryotic biochemical defect is corrected by the eukaryotic enzymes (C.B.B., I.C., E. Caputo, V.J.S., J.C.E.-S., J.S.S. & J.D.B., unpublished observations). This result supports the idea that these enzymes can transfer ADP-ribose or a related moiety of NAD+ to a small molecular target in vivo; in this case, a cobalamin biosynthetic intermediate. This result supports a conserved NAD+ phosphotransferase activity in Sir2 proteins.

The NAD+ requirement for the HDA activity could reflect a simple allosteric (noncovalent) binding of NAD+ to the enzyme. Alternatively, it is quite possible that the HDA activity in these enzymes is activated by NAD+ via actual chemistry of the NAD+ moiety. This could include formation of a covalent adduct to the enzyme, such as ADP-ribose, or cleavage of NAD+ during the reaction. The NPT1 requirement of silencing is consistent with a requirement for consumption of NAD+ during the deacetylation reaction.

By whatever mechanism NAD+ activates the protein deacetylase activity of Sir2-like proteins, it is remarkable that the NAD+ dependence of this activity is conserved from eubacteria to Archaea to humans. We speculate that the Sir2p family of proteins represents a phylogenetically conserved set of effector proteins in an evolutionarily conserved signal transduction pathway that monitors cellular energy and redox states. Cellular NAD+ synthesis depends on ATP, a precursor for NAD+ synthesis. Thus the level of NAD+ depends on the level of ATP. Similarly, if redox states shift to highly reducing, a larger proportion of the cellular NAD+ will be converted to NADH. Viewed from this perspective, it seems reasonable that Sir2-like proteins may have been recruited in evolution to perform diverse deacetylation reactions (and possibly ADP-ribosylation reactions) on a wide variety of substrates in a manner regulated by cellular metabolic state. The human genome contains at least six Sir2p homologs at the last count, and multiple homologs are found in several species, suggesting diverse roles and targets. It seems possible that in yeast, Sir2p, found primarily in the nucleolus, plays a role in regulating rRNA synthesis in response to cellular NAD+ levels. The rate of ribosomal RNA synthesis responds to cellular growth rate in all organisms. Perhaps yeast Sir2p plays a role in transducing metabolic signals that control ribosome synthesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Guarente and R. Sternglanz for communicating their results before publication. We thank D. Moazed, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, for providing reagents, E. Hoff for making a crucial connection, and members of the Boeke lab for helpful discussions. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant CA16519 to J.D.B. Work on Salmonella cobB is supported by National Science Foundation grant MCB9724924 to J.C.E.-S. J.S.S. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Leukemia Society of America and an NIH postdoctoral training grant.

Abbreviations

- HDA

histone deacetylase

- ART

ADP-ribosyl transferase

- SC

synthetic complete medium

References

- 1.Loo S, Rine J. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1995;11:519–548. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.002511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gottschling D E, Aparicio O M, Billington B L, Zakian V A. Cell. 1990;63:751–762. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90141-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith J S, Boeke J D. Genes Dev. 1997;11:241–254. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryk M, Banerjee M, Murphy M, Knudsen K E, Garfinkel D J, Curcio M J. Genes Dev. 1997;11:255–269. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith J S, Brachmann C B, Pillus L, Boeke J D. Genetics. 1998;149:1205–1219. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.3.1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brachmann C B, Sherman J M, Devine S E, Cameron E E, Pillus L, Boeke J D. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2888–2902. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.23.2888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freeman-Cook L L, Sherman J M, Brachmann C B, Allshire R C, Boeke J D, Pillus L. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:3171–3186. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.10.3171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsang A W, Escalante-Semerena J C. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:31788–31794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.31788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frye R A. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;260:273–279. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imai S-I, Armstrong C M, Kaeberlein M, Guarente L. Nature (London) 2000;403:795–800. doi: 10.1038/35001622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park E C, Szostak J W. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:4932–4934. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.9.4932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Megee P C, Morgan B A, Mittman B A, Smith M M. Science. 1990;247:841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.2106160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson L M, Kayne P S, Kahn E S, Grunstein M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6286–6290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braunstein M, Rose A B, Holmes S G, Allis C D, Broach J R. Genes Dev. 1993;7:592–604. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.4.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braunstein M, Sobel R E, Allis C D, Turner B M, Broach J R. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4349–4356. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanny J, Dowd G, Huang J, Moazed D. Cell. 1999;99:735–745. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81671-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rose M D, Winston F, Heiter P. Methods in Yeast Genetics. A Laboratory Course Manual. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cost G C, Boeke J D. Yeast. 1996;12:939–941. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199608)12:10%3C939::AID-YEA988%3E3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith J S, Caputo E, Boeke J D. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3184–3197. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.3184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buck S W, Shore D. Genes Dev. 1995;9:370–384. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.3.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collinge M A, Althaus F R. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;245:686–693. doi: 10.1007/BF00297275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cornell N W, Veech R L. Anal Biochem. 1983;132:418–423. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferenz C R, Nelson D A. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:1977–1995. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.6.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson D A. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:1565–1568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holt G, Hart J. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:8049–8057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lopez-Rodas G, Tordera V, Sanchez del Pino M M, Franco L. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:19028–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanchez del Pino M M, Lopez-Rodas G, Sendra R, Tordera V. Biochem J. 1994;303:723–729. doi: 10.1042/bj3030723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taunton J, Hassig C A, Schreiber S L. Science. 1996;272:408–411. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5260.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rundlett S E, Carmen A A, Kobayashi R, Bavykin S, Turner B M, Grunstein M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14503–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sherman J M, Stone E M, Freeman-Cook L L, Brachmann C B, Boeke J D, Pillus L. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:3045–3059. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.9.3045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burns N, Grimwade B, Ross-Macdonald P B, Choi E-Y, Finberg K, Roeder G S, Snyder M. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1087–1105. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.9.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vinitsky A, Grubmeyer C. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:26004–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Penfound T, Foster J W. In: Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology. Curtiss R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Washington, DC: Am. Soc. Microbiol.; 1996. pp. 721–730. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Afshar G, Murnane J P. Gene. 1999;234:161–168. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zemzoumi K, Guilvard E, Sereno D, Preto A, Benlemlih M, Cordeiro Da Silva A, Lemesre J, Ouaissi A. Gene. 1999;240:57–65. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00433-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manser T, Olivera B M, Haugli F B. J Cell Physiol. 1980;102:379–384. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041020312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moazed D, Kistler A, Axelrod A, Rine J, Johnson A D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2186–2191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strahl-Bolsinger S, Hecht A, Luo K, Grunstein M. Genes Dev. 1997;11:83–93. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Straight A F, Shou W, Dowd G J, Turck C W, Deshaies R J, Johnson A D, Moazed D. Cell. 1999;97:245–256. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80734-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shou W, Seol J H, Shevchenko A, Baskerville C, Moazed D, Chen Z W S, Jang J, Shevchenko A, Charbonneau H, Deshaies R J. Cell. 1999;97:233–244. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80733-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.