Abstract

NC2 is a heterodimeric regulator of transcription that plays both positive and negative roles in vivo. Here we show that the α and β subunits of yeast NC2 are not always associated in a tight complex. Rather, their association is regulated, in particular by glucose depletion. Indeed, stable NC2 α/β complexes can only be purified from cells after the diauxic shift when glucose has been depleted from the growth medium. In vivo, the presence of NC2 α, but not NC2 β, at promoters generally correlates with the presence of TBP and transcriptional activity. In contrast, increased presence of NC2 β relative to TBP correlates with transcriptional repression. NC2 is regulated by phosphorylation. We found that mutation of genes encoding casein kinase II (CKII) subunits as well as potential CKII phosphorylation sites in NC2 α and β affected gene repression. Interestingly, NC2-dependent repression in the phosphorylation site mutants was only perturbed in high glucose when NC2 β and NC2 α are not associated, but not after the diauxic shift when NC2 α and β form stable complexes. Thus, the separation of NC2 α and β function indicated by these mutants also supports the existence of multiple NC2 complexes with different functions in transcription.

Keywords: NC2, diauxic shift, transcriptional repression, yeast, casein kinase II

Assembly of a functional preinitiation complex on core promoters of protein coding genes in eukaryotic cells requires RNA polymerase II and general transcription factors, as well as chromatin remodeling activities. Once the chromatin has been remodeled, the initial and rate limiting event is the recruitment of the TATA-binding protein (TBP) to the core promoter (Klein and Struhl 1994), which then nucleates the assembly of the rest of the complex, initially by the recruitment of TFIIA and TFIIB (Nikolov et al. 1995; Geiger et al. 1996; Orphanides et al. 1996; Tan et al. 1996). The best characterized form of TBP recruited to core promoters is TFIID, which consists of TBP and multiple TAFIIs (TBP-associated factors; Verrijzer and Tjian 1996). However, it is generally thought that other forms of TBP also play important roles in transcriptional regulation (Kuras et al. 2000; Li et al. 2000). Besides the TAFIIs, examples of other TBP-associating factors include the Ccr4–Not complex (Collart and Struhl 1994; Lee et al. 1998; Liu et al. 1998), the Mot1 ATPase (Timmers et al. 1992; Auble et al. 1994; Van der Knaap et al. 1997; Chicca et al. 1998) and the NC2 histone-fold heterodimer (Bur6p–Ydr1p, α–β, or Drap1–Dr1; Meisterernst and Roeder 1991; Inostroza et al. 1992; Goppelt et al. 1996; Cang et al. 1999). It has been suggested that these factors are global repressors of transcription that also play positive roles in vivo (Collart 1996; Madison and Winston 1997; Prelich 1997; Liu et al. 1998).

NC2 was initially purified from human cell extracts as an activity that inhibits basal TATA-dependent transcription in vitro (Meisterernst and Roeder 1991; Inostroza et al. 1992). It was subsequently identified as an essential factor in yeast [encoded by the BUR6 (NC2 α/Bur6p) and NCB2 (NC2 β/Ydr1p) genes] that is both conserved and functionally interchangeable between yeast and human (Goppelt and Meisterernst 1996; Kim et al. 1997; Lemaire et al. 2000). Many experiments define NC2 as a transcriptional repressor. First, after its initial identification, experiments in vitro showed that NC2 could exert variable extents of repression on transcription, depending upon the core promoter (Kim et al. 1996; Willy et al. 2000). NC2 associates with promoter-bound TBP, thereby preventing the recruitment of TFIIA and TFIIB to the promoter (Goppelt et al. 1996). Subsequent studies in yeast identified a mutation in the largest subunit of TFIIA as a suppressor of the essential role for NC2 providing in vivo support for the results of the in vitro studies (Xie et al. 2000). Furthermore, mutations in TBP that prevent the interaction with NC2 were isolated and found to locate near the surfaces of TBP that also mediate association with TFIIB (Cang et al. 1999). Finally, a recent crystal structure of NC2 recognizing the TBP–DNA transcription complex nicely demonstrates how NC2 binding might preclude recruitment of TFIIB and TFIIA to a preformed TBP–DNA complex (Kamada et al. 2001).

In addition to its well-characterized role as a repressor, several experiments suggest that NC2 might also play positive roles in transcription. First, yeast cells expressing a mutant form of the α subunit of NC2, and cells in which NC2 α is depleted, as well as cells that have altered NC2 β activity, display both increased and decreased transcript levels in vivo, depending upon the gene studied (Prelich 1997; Lemaire et al. 2000; Geisberg et al. 2001). Second, the Drosophila homolog of NC2 was isolated from extracts as an activity capable of activating transcription from promoters that carry an element conserved in Drosophila and humans, but not in yeast, called the DPE (downstream promoter element; Willy et al. 2000). Finally, a study in yeast showed that the association of the α subunit of NC2 to promoters generally correlates with transcriptional activity and with occupancy by general transcription factors (Geisberg et al. 2001). Taken together, these studies suggest that NC2 might be an activator as well as a repressor. However, the molecular mechanisms that enable such a dual function are unknown.

We have previously shown that both subunits of NC2 are required for transcription of the yeast HIS3 gene from its TATA-less promoter in exponentially growing cells, as well as for repression of the same gene from its TATA promoter at the diauxic shift (Lemaire et al. 2000). We used these opposite effects of NC2 on HIS3 as a starting point to dissect how NC2 may act both as a transcriptional repressor and a transcriptional activator. Here we report that the two NC2 subunits are not tightly associated in exponentially growing cells, but are able to form a stable complex upon glucose depletion. Furthermore, whereas the α subunit of NC2 can be found at promoters together with TBP in correlation with transcriptional activity, an increased ratio of NC2 β to NC2 α and TBP at promoters correlates with transcriptional repression. The existence of separate forms of the NC2 α and β subunits, taken together with the different association of the α and β subunits of NC2 with promoters, allows us to propose that the two subunits play distinct roles in vivo. This work provides a conceptual framework to explain how mutations in transcription factor genes can have pleiotropic effects, and suggests a molecular mechanism that can enable both positive and negative functions for regulatory factors in vivo.

Results

Different forms of NC2 α and β subunits in cells before and after the diauxic shift

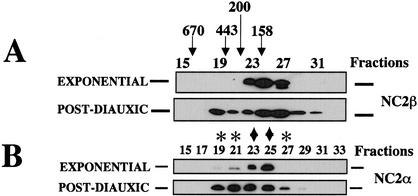

We took a biochemical approach to try and understand the pleiotropic effects of NC2 on transcription. We first analyzed the gel filtration elution profile of the NC2 α and β subunits in yeast cells before and after the diauxic shift (Fig. 1). We found that the β subunit from exponentially growing cells eluted in fractions 23–27 corresponding to a size of ∼150 kD. After the diauxic shift, however, NC2 β eluted with a much broader profile, in fractions 19–31, with new forms found in fractions 19–21, and a broadening of the peak in fraction 25 towards smaller sizes (Fig. 1A). The α subunit of NC2 eluted with a similar profile, mainly in fractions 23–25 from cells growing exponentially, and in fractions 19–27 in cells after the diauxic shift (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Different forms of NC2 α and β subunits before and after the diauxic shift. Three-hundred microliters of total cell extracts from wild-type cells grown exponentially or to the postdiauxic phase, as indicated, was fractionated by Superose 6 gel filtration. The resulting fractions were analyzed by Western blot analysis with antibodies against NC2 β (A) or α (B), as indicated. The peaks of elution from exponential phase cells are indicated by ♦, whereas novel complexes appearing in the postdiauxic phase are indicated by ✻. The sizes indicated from the elution of molecular weight markers (Bio-Rad) are shown above the fractions.

Taken together, these results indicate that both the α and the β subunits of NC2 are associated in complexes of ∼150 kD in exponentially growing cells, and additionally become associated in larger complexes of ∼400 kD after the diauxic shift. It is interesting to note that both subunits also additionally elute as species smaller than 150 kD after the diauxic shift.

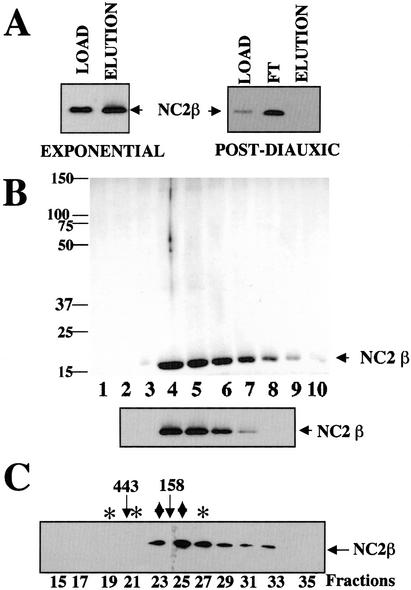

Purification of the β subunit of NC2

To better understand the biochemical behavior of the NC2 complex, we set out to purify the β subunit from extracts made from exponentially growing cells and postdiauxic phase cells, respectively. For this purpose, a strain was constructed in which the β subunit carried a double affinity tag at its C terminus (see Table 1; Winkler et al. 2001). We then purified the subunit through several chromatographic steps including Bio-Rex 70 chromatography, HA-affinity chromatography, and finally nickel–agarose chromatography. We used low salt conditions in order not to disrupt putative fragile complexes. Surprisingly, whereas NC2 β from exponentially growing cells bound well to the affinity columns, the epitope tag was not accessible on NC2 β from extracts of postdiauxic phase cells (Fig. 2A). Thus, NC2 β was purified from exponentially growing cells and coomassie staining revealed a single protein that was confirmed by mass spectroscopy to be the β subunit of NC2 (Fig. 2B). Significantly, the purified β subunit eluted from a gel filtration column with an elution profile similar to the one observed with the β subunit from crude extracts of cells growing exponentially (Fig. 2C; cf. Fig. 1A), supporting the idea that this is the major, if not only, form of NC2 β found in exponentially growing cells. These results, combined with the fact that NC2 β is a 17-kD protein, suggest that the protein forms homo-oligomers in cells growing exponentially in glucose, rather than being associated in stable complexes with other proteins. In particular, the α subunit did not copurify with the β subunit, as this protein was neither detectable by coomassie staining nor mass spectroscopy analysis of the purified fraction.

Table 1.

Strains

| Strain

|

Genotype

|

Reference

|

|---|---|---|

| MY1 | MATa gcn4Δ ura3-52 trp1Δ1 leu2::PET56 gal2 | (Hope and Struhk 1986) |

| MY114 | MATα ura3-52 trp1Δ63 his3Δ200 leu2::PET56 | This study |

| MY1800 | Isogenic to MY1 except ncb2::KanMX4 + pPADH1hNCB2–LEU2 | (Lemaire et al. 2000) |

| MY2407 | Isogenic to MY1 except ncb2::KanMX4 + pPADC1HA-NCB2–LEU2 | This study |

| MY2493 | Isogenic to MY1 except bur6::BUR6-3HA-KanMX4 | This study |

| MY2556 | his4-917Δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ1 ura3-52 suc2ΔUAS(−1900/−390) trp1Δ63 spt15Δ102::LEU2 pSPT15-URA3 | (Cang et al. 1999) |

| MY2658 | Isogenic to MY2556 except bur6::BUR6–3HA-KanMX4 | This study |

| MY2699 | Isogenic to MY1 except MATα ncb2::KanMX4 pPNCB2NCB2-HIS10-HA-TRP1 | This study |

| MY2952 | Isogenic to MY1 except MATα bur6::KanMX4 pPBUR6BUR6-HIS10-HA-TRP1 | This study |

| MY3223 | Isogenic to MY1 except ncb2::KanMX4 + pPNCB2NCB2–URA3 | This study |

| MY3412 | Isogenic to MY1 except ncb2::KanMX4 + pPNCB2ncb2-1-LEU2 | This study |

| MY3413 | Isogenic to MY1 except bur6::KanMX4 + pPBUR6bur6-1-LEU2 | This study |

| MY3351 | Isogenic to MY114 except ncb2::KanMX4 + pPNCB2HA-NCB2–LEU2 | This study |

| MY3352 | Isogenic to MY1 except ncb2::KanMX4 + pPNCB2HA-NCB2–LEU2 | This study |

| MY3357 | Isogenic to MY1 except ncb2::KanMX4 + pPNCB2ncb2-2-3HA-LEU2 | This study |

| YDH6 | MATa cka1-Δ1::HIS3 cka2-Δ1::TRP1 pCKA2-LEU2 | (Hanna et al. 1995) |

Figure 2.

Purification of epitope-tagged NC2 β. (A) Total cell extracts from a strain expressing C-terminally epitope-tagged NC2 β (MY2699) grown to exponential or postdiauxic phase, as indicated, were loaded on a HA-affinity column after elution from a Bio-Rex 70 column. The column load (LOAD), flow-through (FT) or eluate (ELUTION) were analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies against NC2 β. (B) The eluate from the final nickel–agarose column was analyzed by 12.5% SDS-PAGE, followed by coomassie staining (upper panel) or Western blot analysis with antibodies against NC2 β (lower panel). Migration of NC2 β is indicated. (C) Fraction 4 from nickel–agarose was subjected to Superose 6 gel filtration and the indicated fractions were analyzed by Western blot analysis with antibodies against NC2 β. The fractions that were indicated by ♦ and ✻ in the equivalent experiment in Figure 1 are indicated for comparison.

Because the C-terminal tag of NC2 β was not accessible in extracts derived from glucose-depleted cells, the purification was repeated from a strain expressing NC2 β with a single epitope (HA) at the N terminus of the protein. In extracts from this strain, the epitope was accessible under all growth conditions tested (see below). Western blot analysis of the partially purified material from this purification confirmed our previous finding that NC2 α does not copurify with NC2 β from extracts made from cells in exponential phase (Fig. 3A). In contrast, NC2 α did copurify with NC2 β from glucose-depleted cells (Fig. 3A), suggesting a de novo association of the two subunits following glucose depletion at the diauxic shift. Analysis of partially purified NC2 β by gel filtration (Fig. 3B) demonstrated that the purified NC2 β had an elution pattern that was similar to NC2 β from crude cell extracts. Furthermore, the copurified α protein from postdiauxic phase cells eluted with a peak in fraction 21, corresponding to a form of NC2 β that was only observed in extracts from cells grown to the postdiauxic phase (see Fig. 1C).

Figure 3.

Purification of NC2 β epitope tagged at the N terminus. (A) Total cell extracts from a strain expressing N-terminally epitope-tagged NC2 β (MY2407) grown to exponential or postdiauxic phase as indicated, were purified via Bio-Rex 70, DEAE Sepharose, 12CA5-affinity, and nickel–agarose chromatography. The indicated fractions from the final nickel–agarose column were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against NC2 β or α as indicated. (B) The equivalent of 30 μL eluate from the HA-affinity column was subjected to Superose 6 gel filtration. The resulting fractions were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against NC2 β or α, as indicated. The fractions that were indicated by ♦ and ✻ in the equivalent experiment in Figure 1 are indicated for comparison.

Taken together, these results indicate that in cells growing exponentially in glucose, the NC2 β subunit forms a homo-oligomeric complex of ∼100–150 kD, and is not associated in a stable complex with the α subunit. At the diauxic shift, the α subunit then associates with NC2 β to form novel larger complexes.

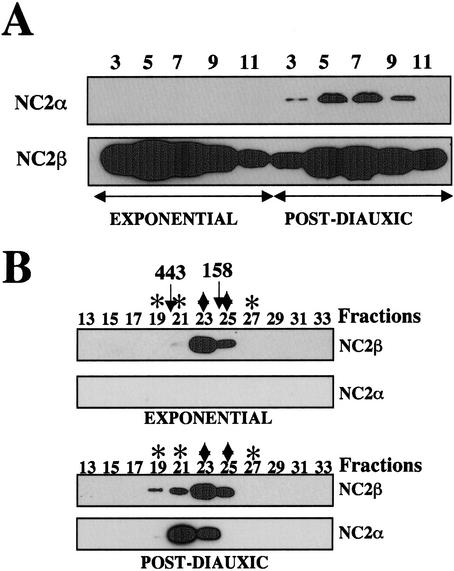

Purification of the NC2 α subunit

To investigate the biochemical behavior of NC2 from the point of view of NC2 α, epitope-tagged NC2 α was now purified from cells growing exponentially and cells grown to the postdiauxic phase, respectively (Fig. 4A). Western blot analysis of purified NC2 α fractions derived from extracts of glucose-depleted cells indicated the presence of copurifying NC2 β, whereas the β subunit was absent in the purified fraction derived from exponentially growing cells (Fig. 4A). The purified NC2 α fractions were also analyzed by coomassie staining (Fig. 4B). This analysis revealed a number of proteins in addition to NC2 α. Whether these additional proteins are associated in a stable complex with NC2 α or are primarily contaminants remains to be resolved. In any case, the β subunit was clearly detectable by coomassie staining (Fig. 4B) and Western blotting (Fig. 4A) of the purified NC2 α fractions from postdiauxic phase cells, but not in the fractions derived from exponentially growing cells.

Figure 4.

Purification of epitope-tagged NC2 α. (A) Total cell extracts from cells expressing C-terminally tagged NC2 α (MY2952) grown to exponential (E) or postdiauxic (PD) phase, as indicated, were purified via Bio-Rex 70, DEAE Sepharose, HA-affinity resin and nickel–agarose. Purified fractions from nickel–agarose were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against NC2 α and β, as indicated. (B) Purified NC2 α (from the nickel eluate) was loaded on a gradient gel (NuPAGE, Invitrogen) and the gel was analyzed by coomassie staining. Molecular weight markers are indicated on the left (in kD).

Taken together, these results confirm that the α and β subunits of NC2 are not associated in a stable complex in exponentially growing cells, but that they do form stable complexes as glucose is depleted.

The α and β subunits of NC2 are not generally found together at promoters

Because the results presented above suggest that the two subunits of NC2 are not always associated in a stable complex, we investigated their association with promoters in vivo by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP). These experiments were done in situations where the tested genes are well expressed, as well as in a situation in which NC2-dependent repression has previously been described. We chose to look at cells growing exponentially in glucose, and shifted to medium without glucose for up to 3 h to mimic the diauxic shift. Under both these conditions, ADH1 is well expressed, with a decrease in expression after glucose depletion. In contrast, HSP104 is activated by glucose depletion (Fig. 5C), whereas HIS3 transcription becomes repressed in an NC2-dependent manner (Lemaire et al. 2000). We used strains that expressed tagged versions of the α and β subunits of NC2 and verified that the two subunits could be immunoprecipitated both from extracts of cells growing exponentially in the presence of glucose, and from cells depleted for glucose (Fig. 5A; data not shown).

Figure 5.

The association of NC2 α with promoters correlates with the presence of TBP at promoters, whereas the presence of both NC2 α and β correlates with transcriptional repression. Wild-type cells (MY1 or MY2556) or cells expressing HA-tagged NC2 α (MY2493 or MY2658) or NC2 β (MY2407 or MY3351) were grown exponentially in glucose-rich medium, washed, and transferred to rich medium lacking glucose for up to 3 h. NC2 α and β were immunoprecipitated with antibodies against HA (A), or were cross-linked for ChIP experiments (B,C), or, finally, total RNA was prepared for S1 analysis of ADH1 or HSP104 mRNA levels (C). (A) Equal amounts of total extract (WCE) and supernatant (FT), or last wash (W) and immunoprecipitate (IP) were analyzed by Western blotting with NC2 α and β antibodies, as indicated. (B,C) For ChIP experiments, fixed cells were lysed, and incubated with HA antibody and protein A Sepharose, or TBP antibody and protein G Sepharose, for immunoprecipitation. (B) The presence of HIS3 or PHO5 (as a control) promoter DNA in the immunoprecipitate was analyzed by radiolabeled PCR (25 cycles). As a control for the equal presence of the investigated DNAs in the strain with (T) or without (U) the tag, the DNA present in the total extract before immunoprecipitation was also analyzed by PCR (INPUT). (C) Input DNAs were comparable for all strains, and the amount of promoter DNA in the immunoprecipitates was expressed in arbitrary units relative to input DNA. The somewhat lower levels of NC2 α occupancy of the ADH1 promoter before glucose depletion was not reproducible. Controls (cont) were either immunoprecipitation from untagged strains (for HA) or processing without antibody (for TBP). Fifty micrograms of total cellular RNA from wild-type cells growing with glucose, or 1 and 3 h after glucose depletion, as indicated, was analyzed for ADH1 and HSP104 expression. Identical results were obtained with all three strains, and thus only the results for the wild-type strain is shown.

As previously described by others (Geisberg et al. 2001), we found that occupancy of the tested promoters by NC2 α alone generally correlated with occupancy by TBP. Thus, like TBP density, NC2 α density on the HSP104 promoter increased under conditions where the HSP104 gene was transcriptionally induced, whereas it was constantly high on the ADH1 promoter (Fig. 5C). Surprisingly, in both cases, TBP and NC2 α remained associated with the promoters after transcript levels decreased. Likewise, NC2 α was present in exponentially growing cells on the active HIS3 promoters (Fig. 5B). In contrast, no association of the NC2 β subunit with the same promoters under conditions where they were active could be detected (Fig. 5B,C). Significantly, both NC2 β and NC2 α could be detected at the HIS3 promoters when this gene was repressed (Fig. 5B).

These results indicate that NC2 α and NC2 β are not generally together at promoters. In contrast to NC2 α, NC2 β association at promoters does not correlate with association of TBP, at least at our test genes under the conditions studied. The presence of NC2 β at a promoter does, however, correlate with transcriptional repression, and occurs under growth conditions in which the NC2 α and NC2 β subunits are associated. This suggests that the association of NC2 α with NC2 β could transform this protein into a repressor.

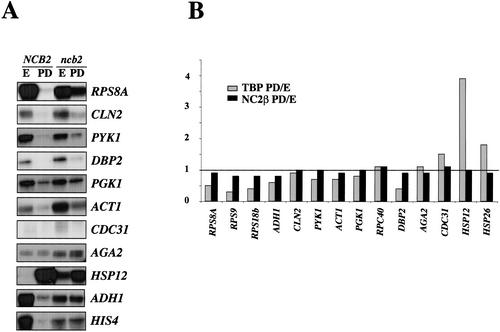

Repression by NC2 correlates with increased presence of NC2 β relative to NC2 α and TBP at promoters

To extend these studies, we set out to identify additional genes that might be regulated by NC2 and in particular repressed by NC2 at the diauxic shift. We compared transcript levels in a wild-type strain and in cells carrying a centromeric plasmid expressing human NC2 β to replace the chromosomal disruption of NCB2. These cells are viable, but mutant for several NC2 β functions as previously reported (Lemaire et al. 2000). We found that many genes repressed at the diauxic shift in wild-type cells were less well repressed in the mutant strain. These include RPS8A, CLN2, PYK1, DBP2, ACT1, HIS4, ADH1, and to a lesser extent PGK1, as shown on Figure 6A. Genes that were not under the same control included CDC31, which was somewhat more expressed in mutant cells than in wild-type cells during exponential growth, but was equally well repressed upon glucose depletion (Fig. 6A). In yet another example, AGA2 was not down-regulated at the diauxic shift in wild-type or mutant cells (Fig. 6A). Finally, we found that appropriate repression of HSP12 in exponentially growing cells and activation of HSP12 at the diauxic shift was also dependent on NC2 β (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

NC2 β is required for repression of HSP12 in cells growing in glucose and for repression of many genes after the diauxic shift. (A) Wild-type (NCB2; MY1) or ncb2 disrupted cells expressing human NC2 from a centromeric plasmid (ncb2; MY1800) were grown to exponential (E) or postdiauxic (PD) phase. Total cellular RNA was extracted and analyzed for the levels of the indicated transcripts. HIS4 was included as a control in this study because the results have been described (Lemaire et al. 2000). (B). For the experiment presented in Table 2, the association of TBP or NC2 β with the indicated promoters in cells after transfer to medium lacking glucose (PD), relative to in cells growing exponentially (E), was calculated. The results presented are the average of three experiments, and each individual experiment showed the same modulations of promoter occupancy.

We next used ChIP experiments to try and correlate the presence of NC2 α and NC2 β at promoters with expression of the studied genes (Table 2). We found that there was generally very little change in the NC2 α/TBP ratio at promoters between cells growing in presence or absence of glucose. This is in agreement with previous results obtained by others showing that the presence of NC2 α at promoters generally follows that of TBP and transcriptional activity (Geisberg et al. 2001). The only exception was the DBP2 promoter where the amount of NC2 α relative to TBP dropped dramatically after the diauxic shift (Table 2). In contrast, the NC2 β/TBP ratio invariably increased upon glucose depletion at the promoters that were repressed in an NC2-β-dependent manner (see Fig. 6A for expression data; Table 2). This was particularly striking for the RPS genes. Significantly, at the AGA2 promoter, which was not repressed upon glucose depletion, there was no increase in the ratio of NC2 β to TBP. Finally, for the HSP12 and HSP26 promoters, the NC2 β/TBP ratio was three- to fourfold higher in cells growing in glucose compared to cells lacking glucose. This correlated nicely with the observation that HSP12 was repressed in an NC2-β-dependent manner in exponentially growing cells in glucose (see Fig. 6A). The changes in the relative levels of NC2 β to TBP result in most part from the fact that whereas TBP (and NC2 α) association at promoters changes when transcription is induced or repressed, the amount of NC2 β associated with promoters does not change much (Fig. 6B).

Table 2.

Modulation of the NC2 α/TBP and NC2 β/TBP ratios at promoters

|

|

NC2 α/TBP

|

NC2 β/TBP

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E

|

PD

|

E

|

PD

|

|

| RPS8A | 1 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 0.07 | 0.2 ± 0.07 | 0.4 ± 0.15 |

| RPS9 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 0.1 ± 0.06 | 0.4 ± 0.1 |

| RPS18b | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.15 | 0.2 ± 0.07 | 0.4 ± 0.15 |

| ADH1 | 1 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.15 |

| CLN2 | 1 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.07 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.2 |

| PYK1 | 2.1 ± 0.15 | 2 ± 0.5 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 |

| ACT1 | 2.5 ± 0.65 | 2 ± 0.25 | 0.3 ± 0.05 | 0.4 ± 0.05 |

| PGK1 | 1.5 ± 0.25 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 0.2 ± 0.07 | 0.2 ± 0.05 |

| RPC40 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.02 | 0.6 ± 0.25 | 0.6 ± 0.2 |

| DBP2 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.3 |

| AGA2 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.15 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.2 |

| CDC31 | 1.9 ± 0.45 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 0.25 | 0.4 ± 0.15 |

| HSP12 | 0.9 ± 0.02 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.15 | 0.2 ± 0.05 |

| HSP26 | 1.3 ± 0.07 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.15 |

Cells expressing tagged NC2 α (MY2493) or tagged NC2 β (MY3352) to functionally complement genomic disruptions of the genes encoding the endogenous subunit were grown to exponential phase in glucose-rich medium (E) and then washed and placed 2 h in rich medium lacking glucose (PD). Cells were then treated with formaldehyde, and TBP (with polyclonal antibodies) or NC2 α or β (with monoclonal antibodies against the HA epitope) were immunoprecipitated from the total cell extract. The amount of the indicated promoter DNA in the immunoprecipitates relative to the total input was calculated. The values obtained for NC2 α or β relative to the values obtained for TBP are indicated. The results presented are the average of three experiments, and each individual experiment showed the same modulations of promoter occupancy.

We finally repeated ChIP experiments using a wild-type strain and polyclonal antibodies raised against the β subunit of NC2 or TBP, to be confident about the modulations of the NC2 β/TBP ratio described above (Table 3). We were able to confirm that the NC2 β/TBP ratio was higher at the promoters under conditions where such promoters are repressed in an NC2-β-dependent manner, such as after the diauxic shift for RPS8A, and to a lesser extent CLN2, and before the diauxic shift for HSP12.

Table 3.

Modulation of the NC2 β/TBP promoter occupancy measured using polyclonal antibodies

|

|

β/TBP

|

|

|---|---|---|

|

E

|

PD

|

|

| HSP12 | 5.1 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.07 |

| RPS8A | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 1.1 |

| CLN2 | 2 ± 0.15 | 2.5 ± 0.75 |

Wild-type (MY1) cells were grown to exponential phase in glucose-rich medium (E) and then washed and placed 2 h in rich medium lacking glucose (PD). Cells were treated with formaldehyde, and TBP or NC2 β were immunoprecipitated with polyclonal antibodies from the total cell extract. The amount of the indicated promoter DNA in the immunoprecipitates relative to the total input was calculated. The values obtained for NC2 β relative to the values obtained for TBP are indicated in the table. The immunoprecipitation of cross-linked NC2 β with polyclonal antibodies is more efficient (approximately 5–10-fold) than that of epitope-tagged NC2 β with anti-HA antibodies, explaining the higher ratios in this table compared to Table 1.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that the presence of NC2 α and NC2 β at promoters does not generally correlate, and that the presence of the subunits at promoters changes independently. These results furthermore show that the amount of NC2 β relative to TBP at promoters increases upon repression if the gene in question is repressed in an NC2- β-dependent manner.

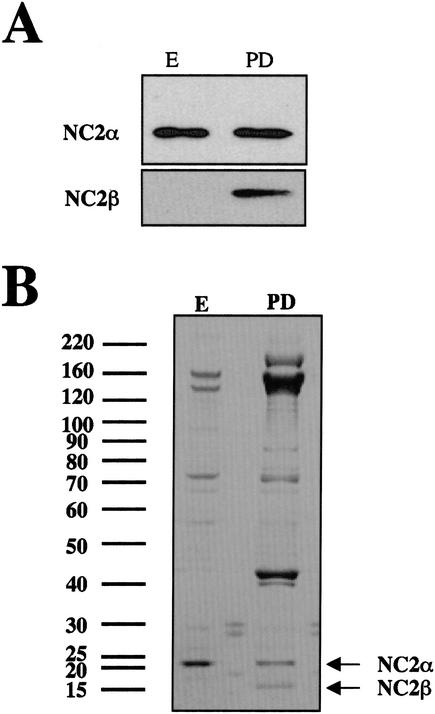

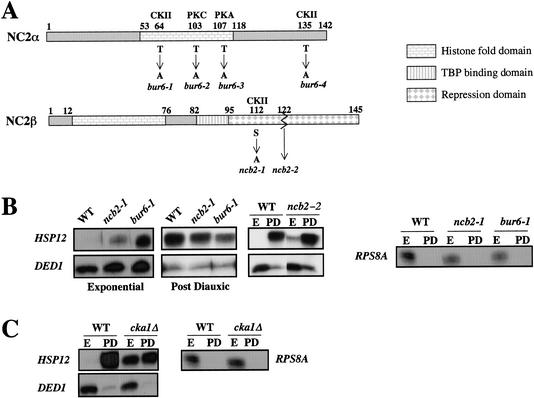

Mutant studies lead to a distinction of the different NC2 functions in vivo

The results presented above suggest that the relative presence at promoters of the α and β subunits of NC2 is variable and important for transcriptional regulation by NC2. Together with our observation that NC2 α and β do not always form a stable complex, these results suggest that different functions of NC2 might be mediated by different forms of the factor. Since NC2 has been described to be a phosphoprotein and the phosphorylation status of NC2 is thought to affect its interaction with TBP and DNA (Inostroza et al. 1992; Goppelt et al. 1996), we investigated the role of phosphorylation in the different NC2 functions. For this purpose, we created several mutant alleles, expressing derivatives of either subunit with mutations in different putative phosphorylation sites (Fig. 7A). We also created a truncated version of NC2 β, lacking the C-terminal domain beyond amino acid 122 and carrying instead a triple HA epitope. This mutant is partially defective in repression (Kim et al. 2000). The function of the mutant alleles was studied through the analysis of the regulation of HSP12 and RPS8A in exponential and postdiauxic phase cells. Most of the mutations had little or no effect on the regulation of HSP12 or RPS8A (data not shown). However, in cells expressing NC2T64A α or NC2S112A β, repression of HSP12 in exponentially growing cells and activation of HSP12 at the diauxic shift was reduced, whereas repression of RPS8A at the diauxic shift was normal (Fig. 7B). In contrast, cells expressing a truncated NC2 β derivative that lacked the C-terminal repression domain were defective in repression of HSP12 in exponentially growing cells and RPS8A at the diauxic shift, but activated HSP12 normally at the diauxic shift (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

Analysis of NC2 and CKII mutants for regulation of HSP12 and RPS8A expression. (A) Schematic representation of the NC2 α and β subunits with indication of the amino acid changes created in the different alleles constructed, and indication of the deletion end-point of the ncb2-2 allele. The mutated sites are putative phosphorylation sites for the kinases indicated above the schematized subunits: casein kinase II (CKII), protein kinase C (PKC), and protein kinase A (PKA). (B,C) The indicated cells were grown to exponential or postdiauxic phases, as indicated, and total cellular RNA was analyzed for the levels of HSP12, DED1 (as an internal control), or RPS8A mRNAs. (B) Wild-type cells (WT; MY3223), or cells expressing NC2S112Aβ (ncb2-1; MY3412), NC2T64Aα (bur6-1; MY3413), or NC2C122β (ncb2-2; MY3357) were studied. (C) Wild-type cells (WT; MY1) or cells lacking CKA1 (cka1Δ; YDH6) were studied.

Threonine 64 in NC2 α and serine 112 in NC2 β are putative phosphorylation sites for casein kinase II (CKII). Thus, to determine whether CKII might be important for NC2 function as previously suggested by studies in vitro (Goppelt et al. 1996), we analyzed regulation of HSP12 and RPS8A in cells lacking CKA1 (encoding one of the two catalytic subunits of CKII; Chen-Wu et al. 1988). We found that such cells had higher levels of the HSP12 transcripts in exponentially growing cells and lower levels of HSP12 at the diauxic shift compared to wild-type cells, but had normal repression of RPS8A at the diauxic shift (Fig. 7C). Interestingly, we observed a similar effect in cells overexpressing the CKA2 gene, encoding the second catalytic subunit (data not shown). These data are consistent with a role for CKII in the transcriptional regulation of HSP12 by NC2.

Taken together, the experiments with these mutants demonstrate a difference between NC2-dependent repression in exponential phase and after the diauxic shift, and also between repression and activation by NC2 after the diauxic shift. Furthermore, they suggest a role in vivo for CKII in regulating NC2 function.

Discussion

In this work we analyzed the molecular interactions of the NC2 regulator in cells growing exponentially in glucose and in cells after the diauxic shift. We made the surprising finding that the NC2 α and NC2 β subunits are not associated in a stable complex in exponentially growing cells. This conclusion was reached after purifying the NC2 β subunit to homogeneity, isolating NC2 β complexes of the same size as those identified in total cell extracts, and finding that no NC2 α subunit copurified with NC2 β. Instead, NC2 β forms homo-oligomers, as has previously been observed (Inostroza et al. 1992). Purification of the NC2 α subunit led to similar conclusions, in that no NC2 β subunit could be copurified with the NC2 α subunit from exponentially growing cells. Because both NC2 α and β have been shown to be essential for yeast vegetative growth (Gadbois et al. 1997; Kim et al. 1997; our personal observations), these results suggest that each subunit plays a separate essential role. Alternatively, the subunits do function together at promoters in exponentially growing cells, but without forming a stable complex.

Our findings are surprising, because it has generally been thought that the two subunits of NC2 function together to activate or repress transcription (Goppelt and Meisterernst 1996; Goppelt et al. 1996), to the extent that conclusions about the NC2 regulator have been drawn based upon experiments done with the NC2 α subunit alone (Geisberg et al. 2001) or with the NC2 β subunit alone (Christova and Oelgeschlager 2001). Nevertheless, results that point towards possible distinct or independent roles for the two NC2 subunits can be found in the literature (Inostroza et al. 1992; Yeung et al. 1994, 1997; Mermelstein et al. 1996; Kim et al. 1997, 2000). First, human NC2 β was isolated in the absence of NC2 α and found to form a complex with TBP and DNA as well as to repress transcription in vitro (Inostroza et al. 1992). Secondly, binding of human NC2 β alone to a TBP–DNA complex precluded the association of TFIIB (Yeung et al. 1997). Thirdly, a truncated form of human NC2 β that lacked the histone-fold domain, could repress transcription on its own in vitro (Kim et al. 1997). Finally, overexpression of NC2 β alone in yeast reduced the total mRNA content (Kim et al. 1997). These experiments point to a possible role for NC2 β without NC2 α. However, there is also evidence for a possible role of NC2 α independently of NC2 β. For example, sin4 mutation suppresses the lethality of cells lacking NC2 β but not of cells lacking NC2 α (Kim et al. 2000). Interestingly, in plants a role for NC2 α without NC2 β has also been described, in that rice NC2 α can function as a repressor independently of NC2 β (Song et al. 2002).

In contrast to the situation in exponentially growing cells, we find that the α and β subunits of NC2 are associated in a stable complex after the diauxic shift. Interestingly, the conditions that we studied, namely glucose depletion, lead to a large number of changes in cells that are the similar to those induced by a broad range of environmental stress conditions. These stresses in turn lead to specific changes in the expression of specific genes, and these changes can to a large extent be mimicked by the loss of NC2 α function (Geisberg et al. 2001). It will be interesting to determine whether association of the α and β subunits of NC2 is generally regulated by environmental stress conditions. Indeed, if the assembly of a functional NC2 repressor occurs as part of a general response to environmental stress this would nicely explain the relationship between NC2 and regulation of environmental stress genes.

Many phosphorylation events are associated with environmental stress responses, and NC2 is a phosphoprotein whose phosphorylation state has an impact on activity (Inostroza et al. 1992; Goppelt and Meisterernst 1996; Goppelt et al. 1996). Thus, one might expect that protein phosphorylation plays a role in the regulation of NC2 α and β activity. Mutation of putative PKA or PKC sites within NC2 had no observable effect on NC2-dependent transcriptional regulation. In contrast, mutation of putative CKII phosphorylation sites within NC2 α or NC2 β altered certain NC2 functions in vivo. This is consistent with previous experiments in vitro, in which it was shown that phosphorylation by CKII increases the affinity of NC2 for TBP–DNA complexes, over nonspecific DNA binding (Goppelt et al. 1996). The exciting finding is that such mutations reduce repression by NC2 in exponentially growing cells but not NC2-dependent repression after the diauxic shift. This correlates with our observed difference in NC2 complexes before and after the diauxic shift and suggests that phosphorylation by CKII is important to obtain NC2-dependent repression when there are no stable NC2 α/β complexes, possibly because it allows specific binding of NC2 to certain promoters.

We have found a nice correlation between the association of NC2 β and NC2 α in stable complexes, NC2-β-dependent repression of many genes at the diauxic shift, and increased occupancy of repressed promoters by NC2 β relative to NC2 α at this time. We have also found that NC2-β-dependent repression of stress genes in exponentially growing cells correlates with higher occupancy of NC2 β relative to NC2 α on these promoters compared to after the diauxic shift when the stress genes are induced. In fact, in exponentially growing cells, the ratio of NC2 α to NC2 β occupancy is lowest on the repressed HSP12 promoter compared to all other promoters that we have tested. It seems likely that NC2 β represses the stress genes together with NC2 α, as we have mutants both in the α and in the β subunit that affect HSP12 repression in exponentially growing cells. This suggests that promoter-bound NC2 α can associate with NC2 β at promoters when repression is required also in exponentially growing cells. However, the nature of the promoter may be very important. For instance, the presence of activator proteins on a given promoter might interfere with the association of NC2 β to promoter-bound NC2 α. In any event, our results show that increased presence of NC2 β relative to NC2 α clearly correlates with repression, not activation.

As others before us, we have found that NC2 α is present at promoters in a way that correlates with the presence of TBP and transcriptional activity (Geisberg et al. 2001). Whether NC2 α associates with TBP-bound promoters in order to be able to associate with NC2 β at the correct time, or whether it plays an active positive role in transcription is not known. The description of a role of NC2 α independently of NC2 β (Kim et al. 2000) would argue against the former possibility. Furthermore, recent experiments in vitro have suggested that the NC2 complex can play a positive role in transcription (Willy et al. 2000). Whether or not NC2 α plays an active positive role at promoters is not clear from our results. In contrast to what others have found (Geisberg et al. 2001) we do not see any difference in the occupancy of promoters by NC2 α relative to TBP at promoters that are up-regulated by NC2 α (such as DBP2), down-regulated (AGA2, HSP12) or unaffected (PGK1, PYK1, ACT1 …). Nevertheless, it is still possible that the presence of NC2 α is important for transcription from certain promoters but not others. This will need to be studied further.

Whether NC2 β has a function in vivo independently of NC2 α particularly in exponentially growing cells is unclear. Previous studies have demonstrated that it has the capacity to repress transcription in vitro in the absence of NC2 α (Yeung et al. 1997), but whether it actually does so in vivo cannot be deduced from our results. Indeed, we have not detected NC2 β in the absence of NC2 α at any promoter analyzed, active or repressed, although we can not rule out the possibility that we have not yet analyzed the right target promoters. Concerning a possible role of NC2 β in activation, a recent study described that human NC2 β could be selectively cross-linked to active but not inactive class II gene promoters in asynchronous cell populations (Christova and Oelgeschlager 2001). However, our studies do not reveal any correlation that might suggest a positive role of NC2 β in transcription in yeast. In one NC2 β mutant, ncb2-1, we did observe decreased activation of HSP12 at the diauxic shift. However, concurrently we also observed a drop in the ratio of NC2 β versus NC2 α at the HSP12 promoter at the diauxic shift, which argues against a model in which an NC2 α/β complex contributes to activate the HSP12 promoter at this time.

Taken together, our observations suggest that a modified view of the NC2 transcriptional regulator is required. According to this model, the NC2 α subunit alone might function on certain promoters as a positive transcription factor independently of the β subunit, and might then be transformed into a factor with repressive functions by association with NC2 β. These studies thus provide an attractive example of how a positive transcription factor might be turned into a negatively acting one by the regulated association with a repressive subunit.

Materials and methods

Strains and media

All strains used are listed in Table 1, and were cultured either in YPD or YP. Strains expressing the NC2 α protein or a truncated NC2 β protein, tagged with a triple HA epitope at the C terminus, were created according to Longtine et al. (1998). The in-frame fusions, as well as protein expression levels, were controlled by immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibodies and Western blotting revealed with polyclonal antibodies against NC2 α or β.

To create a plasmid expressing the β subunit of NC2 with an HA epitope at the N terminus, we subcloned the coding sequences of NC2 β in a pBS derivative carrying the HA epitope in the polylinker. The created fusion sequence was subcloned into pPC62, leading it to be expressed under the control of the ADC1 promoter (pMAC280). A construct expressing the same fusion protein under the control of its own promoter was obtained by amplifying promoter sequences by PCR and subcloning them into pMAC280 between the ApaI and PstI restriction sites to replace the ADC1 promoter (pMAC399).

To put a His10-HA epitope tag at the C terminus of NC2 α, a DNA sequence encoding part of the coding region of NC2 α in which the stop codon was replaced by a SpeI restriction site was amplified by PCR from the pML12 plasmid (Lemaire et al. 2000), and the PCR product was cloned between the KpnI and SpeI sites of pMAC303, leading to pMAC312. pMAC312 was digested with SphI-StyI and cloned into the same sites of pML21 (carrying a genomic clone of the gene) to obtain a TRP1 centromeric plasmid expressing a complete NC2 α fusion protein from its native promoter (pMAC334).

To obtain a TRP1 centromeric plasmid expressing a complete NC2 β fusion protein with a His10-HA epitope at the C terminus from its own promoter, the gene was amplified by PCR and cloned between the KpnI and SpeI sites of pMAC303 (pMAC306). The KpnI-SacI DNA fragment of pMAC306 was further subcloned into pRS314 (pMAC311). Strains expressing the tagged derivatives in place of the wild-type gene grew like their wild-type counterparts.

Site-directed mutagenesis

We used the QuikChange Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and controlled clones by sequencing.

Immunoprecipitation

Whole cell extracts were prepared from 50 O.D.600 units of cells growing exponentially (O.D.600 < 1.5) or after the diauxic shift (O.D.600 8–10). Cells were broken in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES at pH 7.5; 300 mM NaCl; 1 mM EDTA at pH 8.0; 0.1% Triton, 1 mM PMSF) with glass beads and vortexing 40 min at 4°C. The lysates obtained were clarified by successive centrifugations. Immunoprecipitations were performed with 1 mg of total protein extract in a final volume of 200 μL. One microliter of antibodies (anti-HA monoclonal, Babco) and 50 μL of protein A Sepharose slurry in lysis buffer (1:1) were added before incubating the tubes overnight on a rotator at 4°C. After spinning down the beads and removing the supernatant, the beads were washed 3× with an excess of lysis buffer by gently inverting the tubes. The immunoprecipitated proteins were recovered in SDS-PAGE loading buffer and analyzed by Western blot.

Antibodies

Recombinant NC2 α or β were injected into rabbits for antibody production (Elevage scientifique des Dombes).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Cells were grown in YPD to an O.D.600 between 0.6 and 1.0, extensively washed with water or YP and placed in rich medium with glucose, or without any carbon source, for 1–3 h. Cells were fixed by addition of formaldehyde to a final concentration of 1% for 30 min at room temperature, followed by addition of glycine to a final concentration of 125 mM. Cells were washed 2× in cold TBS, and broken in FA lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES at pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA at pH 8.0, 1% Triton, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate) supplemented with 1 mM PMSF as described previously (Strahl-Bolsinger et al. 1997; Kuras and Struhl 1999). The crude extract was sonicated after addition of SDS to a final concentration of 0.5%, cleared, and sonicated again, leading to the Soluble Total Chromatin (STC). An aliquot of the STC (30 μL) was kept as a control. The immunoprecipitation of DNAs were done on STC diluted 1:5 in FA-lysis buffer. For immunoprecipitation, 1 mL of diluted STC was incubated overnight on a rotator at 4°C with 2 μL of monoclonal anti-HA antibodies or 0.5 μL of polyclonal anti-TBP antibodies (purified IgG fraction), or 2 μL of polyclonal anti-NC2 β antibodies, and 50 μL of protein A or G Sepharose (a 1:1 slurry in FA lysis buffer). The resin was then sequentially washed with TSE 150 (20 mM Tris at pH 8.0; 2 mM EDTA at pH 8.0; 1% Triton; 0.1% SDS; 150 mM NaCl), TSE 500 (TSE 150, except 500 mM NaCl), buffer III (10mM Tris at pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA at pH 8.0, 250 mM LiCl, 1% Igepal, 1% sodium deoxycholate), and, finally, TE. Immunoprecipitated DNA was recovered by incubating twice the resin in elution buffer (1% SDS; 50 mM Tris at pH 7.5; 10 mM EDTA at pH 8.0) at 65°C. The reversal of cross-links, phenol-chloroform extraction and precipitation of the DNA have been described previously (Deluen et al. 2002). Immunoprecipitated DNA was finally resuspended in 25 μL of TE or H2O, whereas the aliquot of STC was resuspended in 100 μL of TE or H2O. The presence of the HIS3 and PHO5 promoters in the immunoprecipitate was determined by radio-labeled PCR, whereas for all other promoters tested, real-time PCR with the SYBR Green dye was used. The sequence of the primers used is available upon request. For the real-time PCR, the DNA recovered in the precipitate was expressed relative to the amount of DNA in the STC (as calculated by dilution curves) in arbitrary units.

Gel fitration

Whole cell extract was prepared in lysis buffer (see above) supplemented with 5% glycerol. Cleared lysate was filtered on 0.45-μm filter and 300 μL were loaded on the Superose 6 column (Superose 6 HR10/30, Pharmacia) equilibrated in the same buffer, at a flow rate of 24 mL/h. Four-hundred-microliter fractions were collected. Uneven fractions were precipitated with TCA and pellets were resuspended in 0.1 N NaOH by sonication, mixed with SDS-PAGE loading buffer and analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting. Thyroglobuline (669 kD), apoferritin (443 kD), β-amylase (200 kD), aldolase (158 kD), bovine serum albumin (67 kD), and ovalbumin (44 kD) were used as markers to calibrate the column and eluted at 12.5, 14, 15, 15.75, 16.5, and 17.125 mL, respectively.

NC2 purification

Cultures (inoculated at ∼3.107 cells/mL) of 100 L were grown in YPD in fermentators. Half was collected at the exponential phase of growth, whereas the second part was collected after the diauxic shift. Cells were broken in 3× lysis buffer [450 mM Tris acetate at pH 7.8; 150 mM potassium acetate; 3 mM EDTA; 60% glycerol; proteases inhibitors (100× is leupeptin 0.0284 g/L, pepstatin A 0.137 g/L, PMSF 17 g/L and benzamidine 0.033 g/L)] using a Ball Mill (Dyno-Mill Type KDL-A). Proteins were separated from DNA by ultracentrifugation after potassium acetate precipitation. The protein extract was diluted in the appropriate buffer before loading onto columns, to reduce the conductivity of the samples.

For strain MY2699, expressing NC2 β-His10-HA, the first step was Bio-Rex 70 (Bio-Rad) anion exchange chromatography. The Bio-Rex 70 was pre-equilibrated in buffer A (10% glycerol, 40 mM HEPES at pH 7.6, 1 mM EDTA, 1× protease inhibitors) supplemented with 100 mM KCl. Bound proteins were step-wise eluted with buffer A to which 200, 600, and 1000 mM KCl was added. NC2 β-His10-HA eluted at 600 mM KCl. Those fractions were pooled and submitted to 70% ammonium sulfate precipitation. The pellet was resuspended with 30 mL of buffer A and incubated with 4 mL of protein A Sepharose CL4B-12CA5 monoclonal antibody resin (1–3 mg antibody/mL resin) overnight at 4°C. The resin was collected by flow gravity in a column and washed with 4 mL Ni-buffer (40 mM Hepes at pH 7.6; 10% glycerol; 0.1% Tween 20; 600 mM KOAc; 2 mM β mercaptoethanol and 1× protease inhibitors). Bound proteins were eluted 2× with 1 mL of Ni-buffer containing 2 mg/mL HA peptide (KKRILYPYDVPDYA) for 15 min at 30°C. The elution fractions were pooled and incubated with 0.4 mL Ni-NTA agarose (QIAGEN) for 4 h at 4°C on a rotating wheel. The resin was collected by gravity flow in a disposable column and washed with 2 mL of Ni-buffer. Bound proteins were eluted successively with 10× 75 μL fractions of Ni40-buffer (40 mM imidazole; 40 mM Hepes at pH 7.6; 10% glycerol; 0.1% Tween 20; 200 mM KOAc; 2 mM β mercaptoethanol; 1× protease inhibitors) and Ni500-buffer (same except 500 mM imidazole, 300 mM KOAc).

For strain MY2407, expressing NC2 β with a single HA epitope at the N terminus from a heterologous promoter, the flow-through of the Bio-Rex 70 was loaded onto DEAE Sepharose, pre-equilibrated in buffer B (10% glycerol 20 mM Tris acetate at pH 7.8, 1 mM EDTA, 1× protease inhibitors) supplemented with 100 mM KCl. Bound proteins were step-wise eluted with buffer B supplemented with 200 and 600 mM KCl. NC2 β complexes eluted in 200 mM KCl. Those fractions were pooled and precipitated as before, and then subjected to 12CA5-affinity purification as described above. The elutate from the 12CA5-affinity resin was further purified on nickel–agarose. This step was done by mistake as NC2 β in this strain was not tagged with multiple histidines, and although NC2 β did bind the resin, the nickel–agarose step did not contribute to any further enrichment. The fractions eluted from nickel–agarose were aliquoted and stored at −80°C.

For strain MY2952, expressing NC2 α-His10-HA, the protein extracts were diluted with buffer B, and loaded first to the Bio-Rex 70 resin preequilibrated in buffer A containing 100 mM KCl. The flow through of the Bio-Rex 70 went directly on top of the DEAE resin pre-equilibrated in buffer B containing 100 mM KCl. Proteins bound to the DEAE resin were step-wise eluted with buffer B containing 200 mM and 600 mM KCl. NC2 α-containing complexes were found essentially in the 200 mM KCl fractions of the DEAE. Those fractions were pooled and precipitated as mentioned above. The precipitated material was then subjected to HA-epitope-affinity followed by nickel-affinity chromatographies as described previously.

S1 analysis of total cellular RNA

Total RNA was prepared and analyzed as described previously (Collart and Struhl 1993). Oligonucleotide sequences are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Popi Syntichaki and George Thireos for helping to set up ChIP experiments. We thank Nicole Paquet for expert technical assistance and all members of the laboratory for useful comments, in particular Cécile Deluen for a critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by Swiss National Science Foundation grants (31-39690.93 and 31-49808.96) as well as the OFES96.0072 TMR grant.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL martine.collart@medecine.unige.ch; FAX 41-22-702-55-02

Article and publication are at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.234002.

References

- Auble DT, Hansen KE, Mueller CGF, Lane WS, Thorner J, Hahn S. MOT1, a global repressor of RNA polymerase II transcription, inhibits TBP binding to DNA by an ATP-dependent mechanism. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:1920–1934. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.16.1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cang Y, Auble DT, Prelich G. A new regulatory domain on the TATA-binding protein. EMBO J. 1999;18:6662–6671. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.23.6662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen-Wu JL-P, Padmanabha R, Glover CVC. Isolation, sequencing, and disruption of the CKA1 gene encoding the α subunit of yeast casein kinase II. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:4981–4990. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.11.4981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chicca JJ, Auble DT, Pugh FB. Cloning and biochemical characterization of TAF172, a human homolog of yeast MOT1. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1701–1710. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.3.1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christova R, Oelgeschlager T. Association of human TFII–promoter complexes with silenced mitotic chromatin in vivo. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;4:79–82. doi: 10.1038/ncb733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collart MA. The NOT, SPT3, and MOT1 genes functionally interact to regulate transcription at core promoters. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6668–6676. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.6668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collart MA, Struhl K. CDC39, an essential nuclear protein that negatively regulates transcription and differentially affects the constitutive and inducible HIS3 promoters. EMBO J. 1993;12:177–186. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05643.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— NOT1 (CDC39), NOT2 (CDC36), NOT3, and NOT4 encode a global negative regulator of transcription that differentially affects TATA-element utilization. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:525–537. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.5.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deluen C, James N, Maillet L, Molinete M, Theiler G, Lemaire M, Paquet N, Collart MA. The Ccr4–Not complex and yTAF1(yTafII130p/yTafII145p) present physical and functional interactions. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:6735–6749. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.19.6735-6749.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadbois EL, Chao DM, Reese JC, Green MR, Young RA. Functional antagonism between RNA polymerase II holoenzyme and global negative regulator NC2 in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94:3145–3150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger JH, Hahn S, Lee S, Sigler PB. Crystal structure of the yeast TFIIA/TBP/DNA complex. Science. 1996;272:830–836. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisberg JV, Holstege FC, Young RY, Struhl K. Yeast NC2 associates with the RNA polymerase II preinitiation complex and selectively affects transcription in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:2736–2742. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.8.2736-2742.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goppelt A, Meisterernst M. Characterization of the basal inhibitor of class II transcription NC2 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4450–4455. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.22.4450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goppelt A, Stelzer G, Lottspeich F, Meisterernst M. A mechanism for repression of class II gene transcription through specific binding of NC2 to TBP–promoter complexes via heterodimeric histone fold domains. EMBO J. 1996;15:3105–3116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna DE, Rethinaswamy A, Glover CVC. Casein kinase II is required for cell cycle progression during G1 and G2/M in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25905–25914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope I, Struhl K. Functional dissection of a eukaryotic transcriptional activator protein. Cell. 1986;46:885–894. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inostroza JA, Mermelstein FH, Ha I, Lane WS, Reinberg D. Dr1, a TATA-binding protein-associated phosphoprotein and inhibitor of class II gene transcription. Cell. 1992;70:477–489. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90172-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamada K, Shu F, Chen H, Malik S, Stelzer G, Roeder RG, Meisterernst M, Burley SK. Crystal structure of negative cofactor 2 recognizing the TBP–DNA transcription complex. Cell. 2001;106:71–81. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00417-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Parvin JD, Shykind BM, Sharp PA. A negative cofactor containing Dr1/p19 modulates transcription with TFIIA in a promoter-specific fashion. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:18405–18412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Na JG, Hampsey M, Reinberg D. The Dr1/Drap1 heterodimer is a global repressor of transcription in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94:820–825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Cabane K, Hampsey M, Reinberg D. Genetic analysis of the Ydr1–Bur6 repressor complex reveals an intricate balance among transcriptional regulatory proteins in yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2455–2465. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.7.2455-2465.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein C, Struhl K. Increased recruitment of TATA-binding protein to the promoter. Science. 1994;266:280–282. doi: 10.1126/science.7939664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuras L, Struhl K. Binding of TBP to promoters in vivo is stimulated by activators and requires Pol II holoenzyme. Nature. 1999;399:609–613. doi: 10.1038/21239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuras L, Kosa P, Mencia M, Struhl K. TAF-containing and TAF-independent forms of transcriptionally active TBP in vivo. Science. 2000;288:1244–1248. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5469.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TI, Wyrick JJ, Koh SS, Jennings EG, Gadbois EL, Young RA. Interplay of positive and negative regulators in transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4455–4462. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.8.4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire M, Xie J, Meisterernst M, Collart MA. The NC2 repressor is dispensable in yeast mutated for the Sin4p component of the holoenzyme and plays roles similar to Mot1p in vivo. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:163–173. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XL, Bhaumik SR, Green MR. Distinct classes of yeast promoters revealed by differential TAF recruitment. Science. 2000;288:1242–1244. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5469.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H-Y, Badarinarayana V, Audino DC, Rappsilber J, Mann M, Denis CL. The NOT proteins are part of the CCR4 transcriptional complex and affect gene expression both positively and negatively. EMBO J. 1998;17:1096–1106. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.4.1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine MS, McKenzie A, Demarini DJ, Shah MG, Wach A, Brachat A, Philippsen P, Pringle JR. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison JM, Winston F. Evidence that SPT3 Functionally interacts with MOT1, TFIIA, and TATA-binding protein to confer promoter-specific transcriptional control in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:287–295. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisterernst M, Roeder RG. Family of proteins that interact with TFIID and regulate promoter activity. Cell. 1991;67:557–567. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90530-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mermelstein JH, Yeung KC, Inostrosa JA, Erdjument-Bromage H, Eagelson K, Landsman D, Levitt P, Tempst P, Reinberg D. Requirement of a corepressor for Dr1-mediated repression of transcription. Genes & Dev. 1996;10:1033–1048. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.8.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolov DB, Chen H, Halay ED, Usheva AA, Hisatake K, Lee DK, Roeder RG, Burley SK. Crystal structure of a TFIIB–TBP–TATA element ternary complex. Nature. 1995;377:119–128. doi: 10.1038/377119a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orphanides G, Lagrange T, Reinberg D. The general transcription factors of RNA polymerase II. Genes & Dev. 1996;10:2657–2683. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.21.2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prelich G. Saccharomyces cerevisiae BUR6 encodes a DRAP1/NC2a homolog that has both positive and negative roles in transcription in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2057–2065. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W, Solimeo H, Rupert RA, Yadav NS, Zhu Q. Functional dissection of a rice Dr1/DrAp1 transcriptional repression complex. Plant Cell. 2002;14:181–195. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strahl-Bolsinger S, Hecht A, Luo K, Grunstein M. Sir2 and Sir4 interactions differ in core and extended telomeric heterochromatin in yeast. Genes & Dev. 1997;11:83–93. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan S, Hunziker Y, Sargent DR, Richmond TJ. Crystal structure of a yeast TFIIA/TBP/DNA complex. Nature. 1996;381:127–134. doi: 10.1038/381127a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmers HTM, Meyers RE, Sharp PA. Composition of transcription factor b-TFIID. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1992;89:8140–8144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.8140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Knaap JA, Borst JW, Van de Vliet PC, Gentz R, Timmers MHT. Cloning of the cDNA for the TATA-binding protein-associated factor II170 subunit of transcription factor B-TFIID reveals homology to global transcription regulators in yeast and Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94:11827–11832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.11827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verrijzer CP, Tjian R. TAFs mediate transcriptional activation and promoter selectivity. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:338–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willy PJ, Kobayashi R, Kadonaga JT. A basal transcription factor that activates or represses transcription. Science. 2000;290:982–984. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5493.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler GS, Petrakis TG, Ethelberg S, Tokunaga M, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Svejstrup JQ. RNA polymerase II elongator holoenzyme is composed of two discrete subcomplexes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:32743–32749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105303200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J, Collart M, Lemaire M, Stelzer G, Meisterernst M. A single point mutation in TFIIA suppresses NC2 requirement in vivo. EMBO J. 2000;19:672–682. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.4.672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung KC, Inostroza JA, Mermelstein FH, Kannabiran C, Reinberg D. Structure-function analysis of the TBP-binding protein Dr1 reveals a mechanism for repression of class II gene transcription. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:2097–2109. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.17.2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung K, Kim S, Reinberg D. Functional dissection of a human DR1–DRAP1 repressor complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:36–45. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]