Abstract

myo-Inositol hexakisphosphate (InsP6) is the most abundant inositol phosphate in cells, yet it remains the most enigmatic of this class of signaling molecule. InsP6 plays a role in the processes by which the drought stress hormone abscisic acid (ABA) induces stomatal closure, conserving water and ensuring plant survival. Previous work has shown that InsP6 levels in guard cells are elevated in response to ABA, and InsP6 inactivates the plasma membrane inward K+ conductance (IK,in) in a cytosolic calcium-dependent manner. The use of laser-scanning confocal microscopy in dye-loaded patch-clamped guard cell protoplasts shows that release of InsP6 from a caged precursor mobilizes calcium. Measurement of calcium (barium) currents ICa in patch-clamped protoplasts in whole cell mode shows that InsP6 has no effect on the calcium-permeable channels in the plasma membrane activated by ABA. The InsP6-mediated inhibition of IK,in can also be observed in the absence of external calcium. Thus the InsP6-induced increase in cytoplasmic calcium does not result from calcium influx but must arise from InsP6-triggered release of calcium from endomembrane stores. Measurements of vacuolar currents in patch-clamped isolated vacuoles in whole-vacuole mode showed that InsP6 activates both the fast and slow conductances of the guard cell vacuole. These data define InsP6 as an endomembrane-acting calcium-release signal in guard cells; the vacuole may contribute to InsP6-triggered Ca2+ release, but other endomembranes may also be involved.

InsP6 (myo-inositol hexakisphosphate), a physiological signal generated in guard cells in response to the drought-stress hormone abscisic acid (ABA), is a potent inhibitor of the K+-inward rectifier (IK,in) (1), one of the fundamental elements of the control of guard cell turgor and hence of stomatal aperture. Whereas much is known of the physiological circumstances and molecular mechanisms by which the second messenger, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate [Ins(1,4,5)P3], acts almost ubiquitously as a calcium-mobilizing signal (2, 3), little is known of the circumstances or mode of action of InsP6. In animal cells, Ins(1,4,5)P3 functions to mobilize calcium by acting as a ligand at the cytosolic face of ligand-gated endomembrane calcium-release channels. To date, no candidate Ins(1,4,5)P3 receptor has yet been identified in the Arabidopsis or yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) genomes. Nevertheless, Ins(1,4,5)P3 elevates [Ca2+]cyt when released from caged precursor in guard cells, with consequential inhibition of IK,in and decrease in aperture (4, 5). The calcium reservoir, claimed initially to be the vacuole (6), could also include nonvacuolar stores, because most of the InsP3-binding capacity in the cell is in nonvacuolar membranes (7). Our ignorance of the role on InsP6 in signaling chains stems in part from a general lack of responsiveness of InsP6 to extracellular stimuli in systems other than guard cells (1), fission yeast (8), and hippocampal neurons (9). It is striking that the levels of InsP6 quickly increase in hyperosmotically stressed Schizosaccharomyces pombe (8), and that in plants, treatment with ABA also quickly increases InsP6 levels in guard cells (1). It is clearly important to establish the role of InsP6 in ABA-induced signaling chains. The stomatal guard cell has emerged as a uniquely tractable experimental system in which to study the function of InsP6 in osmotic-stress biology. By applying patch–clamp electrophysiology in whole-cell and -vacuole mode, we have investigated the cellular effectors of InsP6 signaling. In guard cell protoplasts (GCPs), inhibition of IK,in by InsP6 does not occur in the presence of internal calcium chelators such as EGTA or BAPTA (1), suggesting that InsP6 is a calcium-mobilizing signal. In the present work, by use of laser-scanning confocal microscopy in dye-loaded patch-clamped GCPs, we show first that laser uncaging of InsP6 does indeed mobilize calcium and then investigate the source of this increase.

InsP6-induced calcium transients in guard cells could arise from calcium entry through the plasma membrane or by calcium release from internal stores. In pancreatic β cells, InsP6 activates an l-type calcium current (10). Recent studies (11–14) have shown that plants harbor calcium-permeable channels [hyperpolarization-activated calcium current (ICa)] that activate, in contrast to those in animal cells on membrane hyperpolarization, and that in guard cells, these channels increase their opening probability in response to ABA (13). We have tested the effect of InsP6 on ICa and show that the InsP6-induced increase in cytoplasmic Ca2+ is not a consequence of Ca2+ influx from outside but of release of Ca2+ from internal stores. Study of tonoplast ion channels in patch-clamped isolated vacuoles shows activation of both fast-activating [fast vacuolar (FV)] and slowly activating [slow vacuolar (SV)] channels by InsP6.

Methods

Protoplast Isolation. Vicia faba L. cv. (Bunyan) Bunyan Exhibition was grown on vermiculite and GCPs isolated from abaxial epidermal strips of 3- to 4-week-old leaves as described (15). Epidermal strips were floated on medium containing 1.8–2.5% of Cellulase Onozuka RS (Yacult Honsha, Osaka), 1.7–2% Cellulysin (Calbiochem, Behring Diagnostics), 0.026% Pectolyase Y-23, 0.26% BSA, and 1 mM CaCl2 (pH 5.6 and osmolality 360 mOsm·kg–1 adjusted with mannitol), and incubated at 28°C, with gentle shaking. After 120–150 min, released protoplasts were passed through a 25-μm mesh and kept on ice for 2–3 min before being centrifuged at 100 × g for 4 min (at room temperature). The pellet of GCPs was resuspended and kept on ice in 1 or 2 ml of fresh medium containing 0.42 M mannitol, 10 mM (Mes), 200 μM CaCl2, and 2.5 mM KOH (pH 5.55 and osmolality 466 mOsm·kg–1).

Vacuole Isolation. Freshly made protoplasts were allowed to settle to the bottom of the recording chamber and stick well to the glass, then given a hypoosmotic shock (200 mOsm·kg–1) by a continuous perfusion of a solution containing (in mM): 100 KCl, 10 Hepes, 2 EGTA, pH adjusted to 8 (KOH). Perfusion was stopped when >50% of the protoplasts had released their vacuoles (usually in ≈20–30 min). Vacuoles were then perfused with a suitable external solution.

Solutions. Protoplasts (or vacuoles) were placed in a 0.5-ml chamber, allowed to settle, then perfused continuously at flow rates of 1–2 ml per min. The bath and pipette solutions were chosen appropriately for the particular membrane conductance measured. Four different conductances were studied: the inward K+-rectifier (IK,in) and the hyperpolarization-activated calcium current (or ICa) located at the plasma membrane, and the FV vacuolar current and the SV vacuolar current at the vacuolar membrane. For recording of IK,in, the solutions contained (in mM): 5 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 2 K4EGTA, 10 Mes (KOH) at pH 5.5, osmolality 480 mOsm·kg–1 (sorbitol) in the bath; and 92 K-glutamate, 2 MgATP, 3.4 CaCl2, 5 K4EGTA, 10 Hepes (KOH) at pH 7.5, osmolality 520 mOsm·kg–1 (sorbitol) in the pipette. For ICa, the solutions contained 100 BaCl2, 10 Mes (Tris) at pH 5.5, osmolality 230 mOsm·kg–1 in the bath, and 4 K4EGTA, 10 BaCl2, 10 Hepes (Tris) at pH 7.5, osmolality 230 mOsm·kg–1 in the pipette. For recording of both vacuolar channels, the bath contained 200 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 0.1 CaCl2, 10 Hepes (Tris) at pH 7.5, osmolality 440 mOsm·kg–1, with the further addition of 4 mM K4EGTA for the FV channel; for both SV and FV, the pipette contained 200 KCl, 10 CaCl2, 10 Mes (KOH) at pH 5.5, osmolality 460 mOsm·kg–1.

Current-Voltage (I–V) Recording and Analysis. Patch pipettes (5–10 MΩ) were pulled from Kimax-51 glass capillaries (Kimble/Kontes, Vineland, NJ) by using a two-stage puller (Narishige PP-83, Tokyo). Experiments were done at room temperature (20–22°C) by using the standard whole-cell patch–clamp techniques, with an Axopatch 200B Integrating Patch Clamp amplifier (Axon, Union City, CA). Voltage commands and simultaneous signal recordings and analysis were assessed by a microcomputer connected to the amplifier via a multipurpose input/output device (Digidata 1200A, Axon) using pclamp 8.0 software (Axon). After gigaohm seals were formed, the whole-cell configuration was achieved by gentle suction, and the membrane was immediately clamped to a holding voltage (hv) dependent on the membrane conductance to be recorded. For IK,in, FV, and SV, hv was set close to the Nernst potential for K+ (EK). For ICa,hv was set close to ECl. GCPs or their vacuoles were left for 3–5 min before starting any current measurements. All current traces shown were low-pass filtered at 2 kHz before analog-to-digital conversion and were uncorrected for leakage current or capacitative transients. Membrane potentials were corrected for liquid junction potential as described in ref. 16. Nernst potentials were calculated after correction for ionic activities (estimated by geochem-pc software, public domain freeware). I–V relationships for ICa, FV, and SV were plotted as steady-state currents vs. test potential, but IK,in was plotted as the time-dependent current (i.e., the steady-state current minus the instantaneous current) vs. test potential. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Confocal Microscopy. Laser-scanning confocal microscopy of dye-loaded patch-clamped GCPs was used to determine the consequences of laser uncaging of InsP6 on cytosolic calcium. GCPs, isolated from either V. faba or Solanum tuberosum as described above (see also ref. 17), loaded through the patch pipette with P (4, 5)-(o-Nitrobenzyl) inositol hexakisphosphate [P(4,5)-NBZ InsP6] (100–200 μM) (18) and a calcium-sensitive single wave-length emission dye, Calcium Green-1 (100 μM; Molecular Probes Europe, Leiden, The Netherlands). A Leica TCS-NT-UV CLSM was used to uncage InsP6 and to follow changes in [Ca2+]i. InsP6 was uncaged by simultaneous exposure to the 354- and 361-nm lines of an UV laser (10–30 randomly chosen spots of 10-ms duration each). Calcium Green-1 was excited by using the 488-nm line of an ArKr laser with the other lines attenuated to zero. A reflectance short-pass filter of 510 nm was used, and emitted fluorescence was monitored between 515 and 545 nm by using a water immersion 1.2 N.A. objective lens. Ten images of the Calcium Green-1 fluorescence were collected at a resolution of 512 × 512 pixels before uncaging and a further 200 after uncaging at 200-ms intervals. Images were analyzed by using metamorph software (Universal Imaging, West Chester, NY). Each image was pseudocolor-coded, and a scale bar was generated to indicate low (blue) to high [Ca2+] (red). GCPs were bathed in solutions (in mM): 10 KCl/0.5 CaCl2/2 MgCl2/10 Mes, pH 5.5 (KOH)/sorbitol to give 480 mOsm·kg–1. The patch pipette contained (in mM): 92 K+ glutamate, 2 MgCl2,2K2ATP, 10 Hepes at pH 7.5 (KOH), and sorbitol to give 520 mOsm·kg–1 (some experiments contained 3.4 CaCl2/5 EGTA to give resting [Ca2+]i 100 nM).

Results

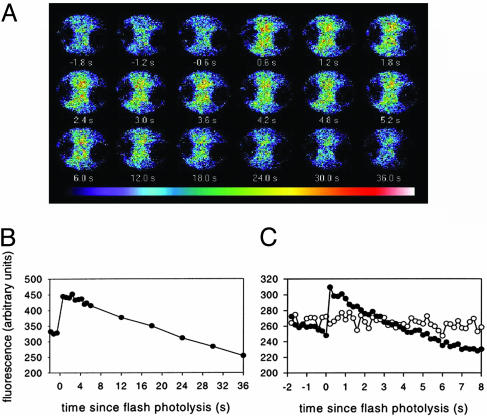

InsP6, Released from Caged Precursor, Mobilizes Ca2+ in Patch-Clamped GCPs. GCPs were loaded with Calcium Green-1 and caged InsP6 to determine the effects on cytoplasmic Ca2+ of uncaging InsP6. In six of nine dye- and P(4,5)-NBZ InsP6-loaded GCPs, we observed transient increases in Calcium Green-1 fluorescence on uncaging. One such experiment is shown in Fig. 1 A and B, in which [Ca2+]cyt levels increased to a maximum within1sof uncaging, persisting at maximal level for ≈5 s before decaying to resting levels within 25–30 s. The time course varied in different experiments, and Fig. 1C shows another time course, with a faster return to preflash levels within 6 s, together with a nonflashed control. UV irradiation was without effect in dye-only loaded protoplasts and also in protoplasts coloaded with caged ATP (not shown). The nature of transients induced by InsP6 release in this study is similar to the transients induced by ABA in GCPs from V. faba (19) and are among the most transitory [Ca2+]cyt signals yet recorded in single protoplasts of a higher plant. We have also investigated the consequence of repetitive uncaging events. Successive release events at intervals of 2–5 min elicited immediate and repetitive excursions in [Ca2+]cyt levels but of diminishing amplitude (not shown). It is therefore clear that uncaging of InsP6 did not exhaust the reservoir of calcium from which the excursions in [Ca2+]cyt level originate. Similarly, ionomycin treatment of a dye- and P(4,5)-NBZ InsP6 coloaded and UV laser-responsive protoplast resulted in a massive increase in dye fluorescence, assumed to result from entry of calcium from the bath solution (not shown). This indicates clearly that the GCPs used were able to regulate their internal free calcium both before and after uncaging of InsP6. These data identify InsP6 as a calcium-mobilizing agent and provide an unambiguous explanation of the [Ca2+]cyt dependence of inhibition of IK,in by InsP6.

Fig. 1.

Transient excursion in cytosolic free Ca2+ observed on uncaging of InsP6 from its caged form. (A) Confocal imaging of a Vicia GCP loaded from a patch pipette containing both [P(4,5)-NBZ InsP6] (100 μM) and Calcium Green-1 (100 μM). Successive images recorded before and after laser irradiation are shown. Each image was pseudocolor-coded, shown in the scale bar (bottom) indicating low (blue) to high (red) [Ca2+]. (B) Integrated fluorescent intensity against time for the images shown. (C) Integrated fluorescent intensity in a second cell flashed at zero time (▪) and in a nonflashed control (□). GCPs were bathed in solutions (mM): 10 KCl/0.5 CaCl2/2 MgCl2/10 Mes at pH 5.5 (KOH)/sorbitol to give 480 mOsm·kg–1. The patch pipette contained (mM) 92 K+ glutamate, 2 MgCl2,2K2ATP, 10 Hepes at pH 7.5 (KOH), and sorbitol to give 520 mOsm·kg–1 (some experiments contained 3.4 CaCl2/5 EGTA to give resting [Ca2+]i ≈100 nM).

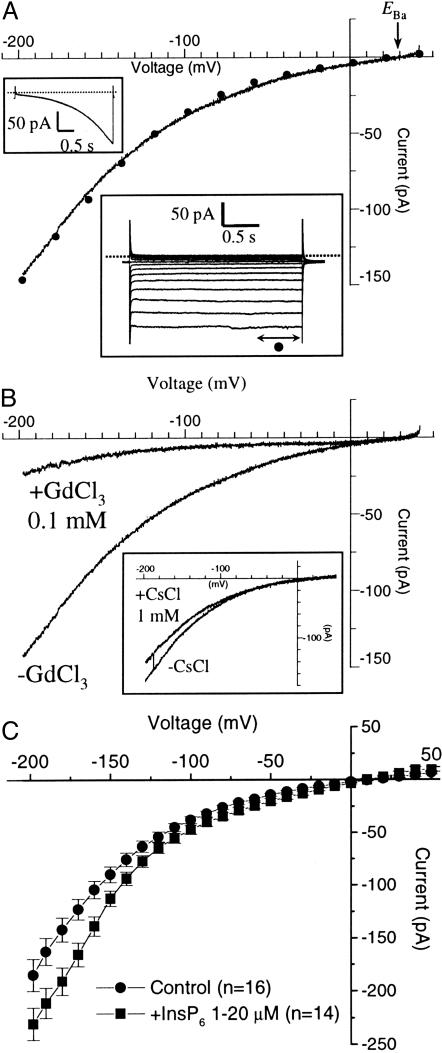

InsP6 Has No Effect on Ca2+ Currents at the Plasmalemma. To measure ICa, GCPs isolated from V. faba were bathed in 100 mM BaCl2, pH 5.5 (Mes/Tris), with 10 mM BaCl2, pH 7.5 (Hepes/Tris) in the pipette. The use of barium instead of calcium has two advantages: that Ba permeates calcium channels more freely than Ca, and that Ba blocks potassium channels more efficiently than Ca. Moreover, in these solutions EBa (+29 mV) and ECl (–58 mV) are far removed from each other, allowing easy identification of the conducting species. GCPs exhibited large whole-cell hyperpolarization-activated barium-permeable channels (IBa) (Fig. 2). Large IBa were observed even in the absence of stimuli such as H2O2 or ABA, which were essential for channel activity in Arabidopsis GCPs (14). We also confirmed substantial activation by ABA (up to 5-fold) and H2O2 (up to 16-fold) of whole-cell currents in Vicia protoplasts (not shown). In Fig. 2A (Lower Inset), Ba-permeable current traces activated instantly without a time-dependent kinetic component, irrespective of voltage (–198 to +42 mV and up to 4-s square wave test pulses). The I–V relationship of whole-cell IBa showed a weakly voltage-dependent rectification with current reversing near the predicted Nernstian equilibrium for barium, EBa (Fig. 2). External addition of GdCl3 (20–100 μM) suppressed these currents (Fig. 2B), whereas in other experiments designed to measure IK,in, similar concentrations of GdCl3 were without effect (not shown). LaCl3 also inhibited IBa but less potently than GdCl3. Verapamil, a calcium-channel blocker, was, at 50 μM concentration, much less effective than GdCl3 or LaCl3. Moreover addition of 1 mM CsCl, which blocks IK,in completely, has no or little effect on IBa (Fig. 2B Inset). More importantly, we show (Fig. 2C) that InsP6 (in the range 1–20 μM in the patch pipette) was without major effect on IBa (n = 16, control; n = 14, InsP6). This contrasts markedly with the effects of ABA on IBa (13) and also with the strong inhibition of IK,in manifest in Vicia at submicromolar InsP6 concentrations (1). The present results therefore indicate that InsP6-mediated [Ca2+]cyt-dependent inhibition of IK,in is not a consequence of InsP6-induced calcium influx via hyperpolarization-activated calcium current.

Fig. 2.

IBa is activated by membrane hyperpolarization, blocked by gadolinium (not cesium), and only slightly affected by InsP6. (A) Whole-cell I–V relationship of IBa showing a weak voltage dependence and current reversal at V ≈+30 mV, which coincides with the calculated theoretical EBa (arrow). See text for detailed bath and pipette solutions. (Upper Inset) Current response to a 4-s voltage ramp from +42 to –198 mV. (Lower Inset) A family of IBa currents in response to square voltage test pulses from +40 to –200 mV (in 20-mV steps); the broken line indicates zero current. The I–V curve is a superimposition of current measurement obtained in response to the voltage ramp protocol (continuous line), and the current measurements in response to the square test pulse protocol (•); each data point is a mean value of the current measured at steady state). (B) I–V curves of IBa (4-s voltage ramp) before and after perfusion with 0.1 mM GdCl3.(Inset) I–V curves of IBa (4-s voltage ramp) before and after perfusion with 1 mM CsCl. (C) I–V curves of IBa (square voltage pulse; 10 mV steps from +50 to –200 mV) in the presence (▪; n = 14) and absence (•; n = 16) of internal InsP6.

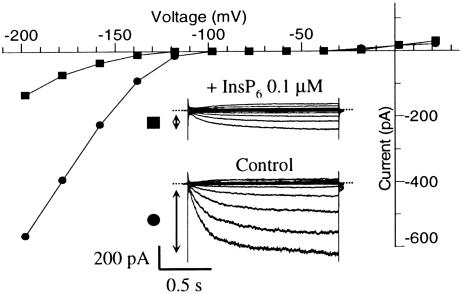

Further confirmation of the absence of an apoplast-derived calcium influx component in InsP6-dependent inhibition of IK,in was afforded by measuring IK,in in the absence of external calcium. Fig. 3 shows one such experiment performed with 2 mM EGTA in the bath solution. Loading the cell with InsP6 (0.1–1 μM in the patch pipette), we observed an up to 80% inhibition of IK,in in 4–6 min (n = 4). We conclude from the foregoing data (Figs. 1, 2, 3) that the InsP6-induced calcium mobilization and the [Ca2+]cyt dependency of inhibition of IK,in resides with an InsP6-sensitive endomembrane store of calcium.

Fig. 3.

InsP6 inactivates IK,in in the absence of external calcium. Current recordings from a GCP 1 min (•) and 5 min (▪) after breaking the patch seal to go whole cell. The patch pipette contained 0.1 μM InsP6. Time-dependent current values (indicated by arrows) were plotted on the corresponding I–V curve; note the inhibition of IK,in by InsP6 but absence of effect on IK,out. The bath contained (mM) 5 KCl, 2 K4EGTA, 2 MgCl2, 10 Mes at pH 5.5 (KOH), and sorbitol to give 480 mOsm·kg–1. The patch pipette contained (mM): 92 K+ glutamate, 3.4 CaCl2/5 EGTA (resting [Ca2+]i ≈ 100 nM), 2 MgATP, 10 Hepes at pH 7.5 (KOH), and sorbitol to give 520 mOsm·kg–1.

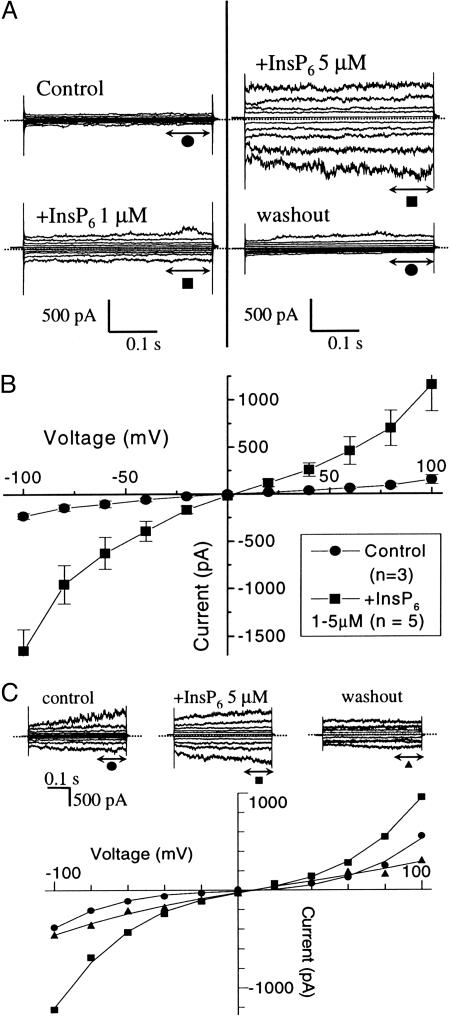

InsP6 Activates Vacuolar Ion Channels. By patch-clamping of isolated vacuoles, we tested whether the endomembrane-store-dependent inhibition of IK,in could be explained by mobilization of vacuolar calcium. Three vacuolar conductances have previously been characterized. The fast vacuolar (FV) conductance is active only at low resting calcium concentration and is inhibited by high cytoplasmic calcium concentration (20–22). On the other hand, high [Ca2+]cyt activates a SV channel (21, 23), which is permeated by both potassium and calcium (24), and a vacuolar potassium channel (23).

Vacuoles were perfused with the recording solution, containing either low calcium (2–200 nM) to measure FV or high calcium (100 μM) to measure SV. In low external calcium and in the whole-vacuole mode, excursion of the membrane voltage between –100 and +100 mV initiated a weakly voltage-dependent fast-activating conductance in both inward and outward directions. Challenge of vacuoles with cytosolic InsP6 (1–5 μM in the perfusing solution) enhanced this conductance without effect on the time-dependent kinetic component (Fig. 4A Left); the activation was reversible on washout of InsP6 (Fig. 4A Right). The effects of InsP6 were further confirmed in cytosolicside-out patches (not shown), indicating that InsP6-dependent activation of the FV conductance is a membrane-delimited process. The I–V plots of vacuolar conductances measured at low cytosolic calcium are shown (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

InsP6 activates vacuolar conductances measured in either low or high cytosolic calcium. (A) Whole vacuolar current traces from two different patch–clamp experiments obtained in low cytosolic calcium (2 nM–200 nM). (Left) Vacuolar current traces before (•) and 10 min after (▪) addition of 1 μM InsP6. (Right) Recovery of current to prestimulated levels after washout of InsP6 (stimulation was achieved in this experiment by 20-min treatment with 5 μM InsP6). (B) I–V plot (+100 to –100 mV in 20-mV steps) measured from whole vacuolar currents obtained in low cytosolic calcium before (•; n = 3) and after (▪; n = 5) addition of 1–5 μM InsP6. (C) Whole vacuolar current traces and corresponding I–V curves (+100 to –100 mV in 20-mV steps) obtained in high cytosolic calcium (100 μM) before (•) and after (▪) addition of 5 μM InsP6. The effect of InsP6 is reversible (▴). (A and B) Bath contained (in mM): 200 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 0.1 CaCl2, 4 EGTA (≈2 nM Free Ca2+), 10 Hepes at pH 7.5 (KOH); patch pipette composition (in mM): 200 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM CaCl2, 10mM Mes at pH 5.5 (KOH). Solutions in C were as in A and B but with 100 μM external calcium and no added EGTA. All membrane potentials are specified as the potential on the cytosolic side relative to the vacuolar side.

Experiments in high calcium and in the whole-vacuole mode were also carried out to assess the effects of InsP6 on SV conductance. Addition of InsP6 (5 μM) activated SV currents. Fig. 4C shows one such experiment where control, InsP6, and recovery measurements were obtained from the same vacuole. InsP6 seems to affect mostly the instantaneous component, with no noticeable effect on the time-dependent activation; as with FV, the effect on SV was also fully reversible on washout (n = 3).

Discussion

The measurements of cytoplasmic Ca2+ after the flash release of InsP6 from its cage establish InsP6 as an effective Ca2+-mobilizing agent in guard cells, to be added to the list of such agents already identified. We now have four agents capable of mobilizing Ca2+ in guard cells and need to establish their physiological relevance. Both Ins(1,4,5)P3 and InsP6 elicit elevations in [Ca2+]cyt in guard cells and both signal to IK,in, inhibiting IK,in in a calcium-dependent manner (1, 5). However, we have shown that InsP6 is ≈100 times more potent as an inhibitor of IK,in than Ins(1,4,5)P3 (1). Two other intracellular signaling agents, cyclic adenosine diphosphoribose (cADPR) (25) and sphingosine-1-phosphate (26), have also been shown to modulate [Ca2+]cyt when introduced into guard cells. Evidence has been presented for the involvement of all four agents in the response of guard cells to ABA (1, 25–29), and an important goal for the future is to establish their relative contributions in different conditions.

The [Ca2+]cyt response of GCPs to uncaging of InsP6 (Fig. 1) is fundamentally different from the response of guard cells to Ins(1,4,5)P3, cADPR, and sphingosine-1-phosphate. The instantaneous increase of [Ca2+]cyt observed with InsP6 and the rapid decay to resting level within 30 s or less contrasts markedly with the sustained increases of [Ca2+]cyt (5–10 min) observed after flash photolysis of caged-Ins(1,4,5)P3 (4) or the 3- to 5-min periodic elevations of [Ca2+]cyt observed with cADPR (25) and sphingosine-1-phosphate (26). However, it is important to note that the method of application of the agent differs in different studies, and the rapid decay in the response to a pulse of InsP6 may reflect the diffusion of InsP6 in the patch pipette or its metabolism; the accurate time course of change in InsP6 levels after stimulation with ABA in intact cells is not established.

InsP6-induced calcium transients in guard cells could result from calcium entry through plasma membrane-permeable channels or calcium release from internal stores. Our findings that InsP6 has no effect on ICa and that InsP6 can inhibit IK,in in the absence of external Ca2+ rule out an effect through activation of calcium influx and point to an endomembrane source for calcium release.

In the context of endomembrane calcium, the vacuole constitutes an important pool of mobilizable calcium in higher plants but may not be the dominant signaling pool. Among the different agents reported to increase guard cell [Ca2+]cyt, both Ins(1,4,5)P3 and cADPR are believed to target endomembranes (25, 30). Thus both agents activate calcium release from the vacuole (30) but also from other endomembranes such as the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (7, 31). A further Ca2+-mobilizing agent in higher plants, nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate, is active exclusively at the ER (32). Our results establish that InsP6 activates two tonoplast ion channels, the FV and SV channels. The activation of the FV channel is reminiscent of the effects of cADPR (25), which activated a fast tonoplast channel inhibited by cytoplasmic Ca2+ above ≈600 nM, but which appeared to be permeable to Ca2+, because the reversal potential was shifted by increase in vacuolar Ca2+. Our results show activation also of the SV channel by InsP6, and this channel is permeable to Ca2+ (24). Thus our results suggest that the vacuole contributes to the InsP6-triggered Ca2+ release, but other endomembranes may also be involved, as is the case for both InsP3 and cADPR.

Our study further defines the mechanism by which InsP6 mediates physiological (ABA-dependent) inhibition of IK,in. The discovery that InsP6 is a calcium-mobilizing agent and produces inhibition of IK,in much more effectively than does InsP3 may yet explain the absence of InsP3 receptors in the yeast and Arabidopsis genomes; conversion of InsP3 introduced into the cytoplasm to InsP6 would produce the effects observed. The work identifies release from endomembrane stores rather than Ca2+ influx as the source of InsP6-triggered increase in cytoplasmic Ca2+, and the demonstration that InsP6 regulates vacuolar release channel(s) provides further evidence that endomembrane channels are cellular targets of InsP6. It remains to be established whether this reflects a direct interaction with the channels or action via a regulatory agent. That such channels are involved in osmoregulation adds considerably to our understanding of the physiological and cellular signaling function of this, the most enigmatic of inositol phosphates.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) Responsive Mode Research Grant 8/P11978 to C.A.B., who is a BBSRC Advanced Research Fellow. A.A.R.W. is a Royal Society University Research Fellow.

Abbreviations: ABA, abscisic acid; IK,in,K+-inward rectifier; InsP6, myo-inositol hexakisphosphate; FV, fast vacuolar; SV, slow vacuolar; GCP, guard cell protoplast; cADPR, cyclic adenosine diphosphoribose; Ins(1,4,5)P3, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate; I–V, current–voltage.

References

- 1.Lemtiri-Chlieh, F., MacRobbie, E. A. C. & Brearley, C. A. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 8687–8692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berridge, M. J. (1997) Nature 386, 759–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berridge, M. J., Lipp, P. & Bootman, M. D. (2000) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 1, 11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilroy, S., Read, N. D & Trewavas, A. J. (1990) Nature 346, 769–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blatt, M. R., Thiel, G. & Trentham, D. R. (1990) Nature 346, 766–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alexandre, J., Lassalles, J. P. & Kado, R. T. (1990) Nature 343, 567–570. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muir, S. R. & Sanders, D. (1997) Plant Physiol. 114, 1511–1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ongusaha, P. P., Hughes, P. J, Davey, J. & Michell R. H. (1998) Biochem. J. 335, 671–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang, S. N., Yu, J., Mayr, J. W., Hofmann, F., Larsson, O. & Berggren, P. O. (2001) FASEB J. 15, 1753–1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larsson, O., Barker, C. J., Sj-oholm, A., Carlqvist, H., Michell, R. H., Bertorello, A., Nilsson, T., Honkanen, R. E., Mayr, G. W., Zwiller, J., et al. (1997) Science 278, 471–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Véry, A. A. & Davies, J. M. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 9801–9806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kiegle, E., Gilliham, M., Haseloff, J. & Tester, M. (2000) Plant J. 21, 225–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamilton, D. W. A., Hills, A., Kohler, B. & Blatt, M. R. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 4967–4972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pei, Z. M., Murata, Y., Benning, G., Thomine, S., Klüser, B., Allen, G. J., Grill, E. & Schroeder, J. I. (2000) Nature 406, 731–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lemtiri-Chlieh, F. (1996) J. Membr. Biol. 153, 105–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neher, E. (1992) Methods Enzymol. 207, 123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muller-Rober, B., Ellenberg, J., Provart, N., Willmitzer, L., Busch, H., Becker, D., Dietrich, P., Hoth, S. & Hedrich, R. (1995) EMBO J. 14, 2409–2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen, J. & Prestwich, G. D. (1997) Tetrahedron Lett. 38, 969–972. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schroeder, J. I. & Hagiwara, S. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 9305–9309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hedrich, R. & Neher, H. (1987) Nature 329, 833–836. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen, G. J. & Sanders, D. (1996) Plant J. 10, 1055–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tikhonova, L. I., Pottosin, I. I., Dietz, K. J. & Schönknecht, G. (1997) Plant J. 11, 1059–1070. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ward, J. M. & Schroeder, J. I. (1994) Plant Cell 6, 669–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pottosin, I. I., Dobrovinskaya, O. R. & Muniz, J. (2001) J. Membr. Biol. 181, 55–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leckie, C. P., McAinsh, M. R., Allen, G. J., Sanders, D. & Hetherington, A. M. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 15837–15842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ng, C. K., Carr, K., McAinsh, M. R., Powell, B. & Hetherington, A. M. (2001) Nature 410, 596–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee, Y., Choi, Y. B., Suh, S., Lee, J., Assmann, S. M., Joe, C. O., Kelleher, J. F. & Crain, R. C. (1996) Plant Physiol. 110, 987–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Staxen, I., Pical, C., Montgomery, L. T., Gray, J. E., Hetherington, A. M. & McAinsh, M. R. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 1779–1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacRobbie, E. A. C. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 12361–12368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allen, G. J., Muir, S. R. & Sanders, D. (1995) Science 268, 735–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Navazio, L., Mariani, P. & Sanders, D. (2001) Plant Physiol. 125, 2129–2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Navazio, L., Bewell, M. A., Siddiqua, A., Dickinson, G. D., Galione, A. & Sanders, D. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 8693–8698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]