Abstract

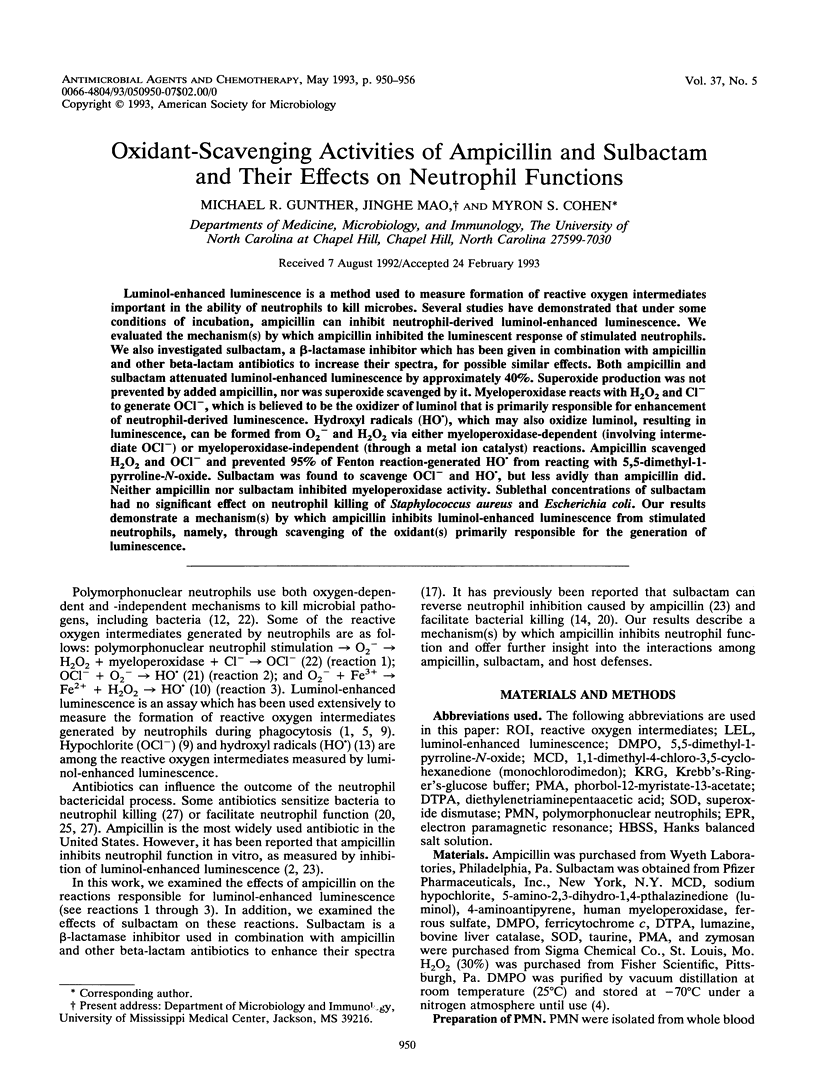

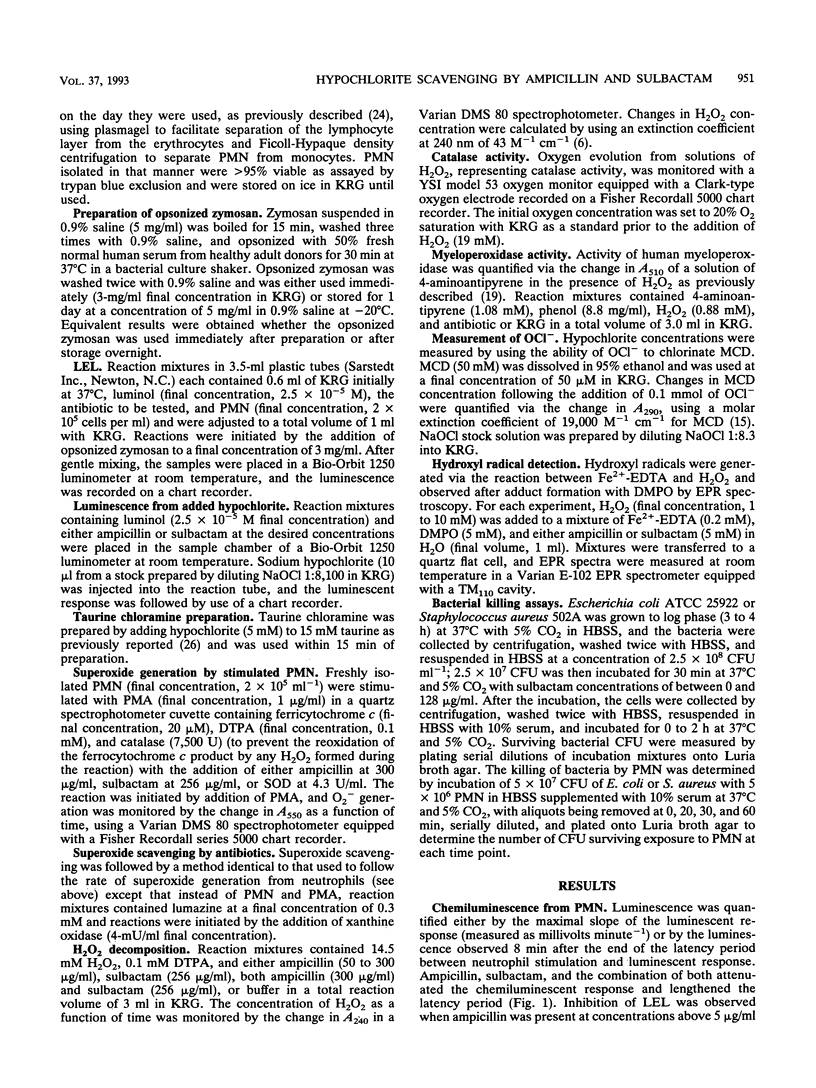

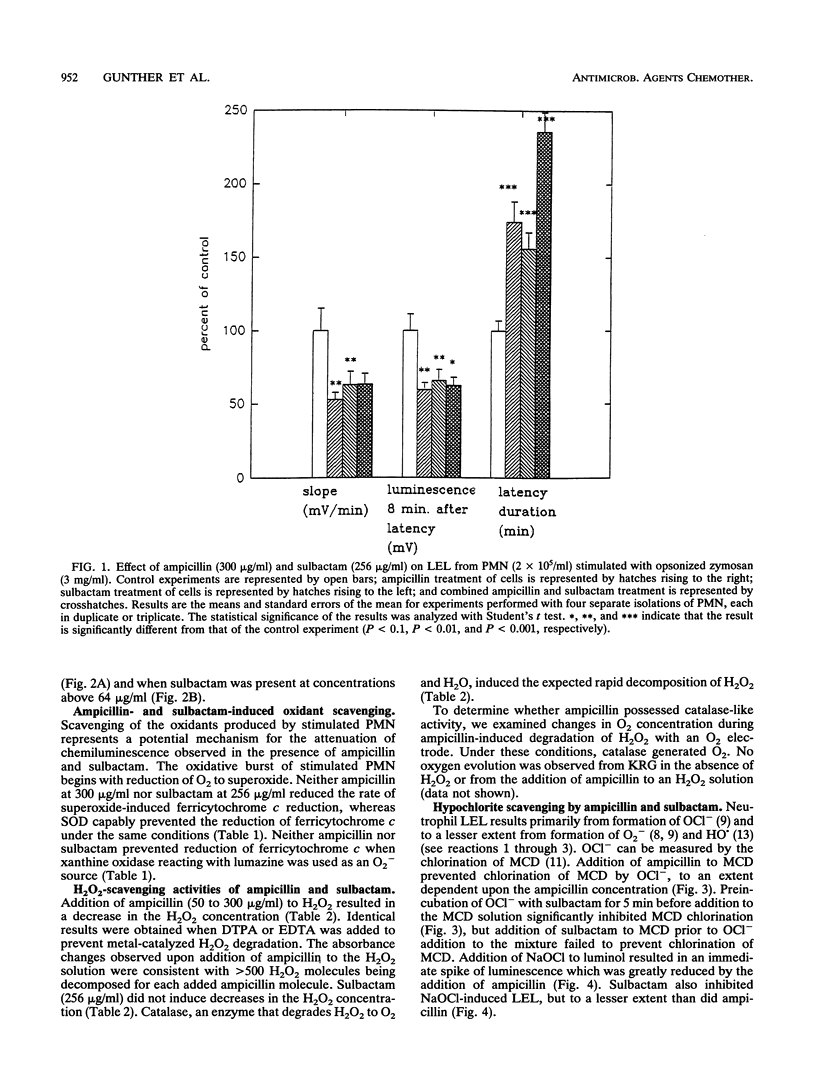

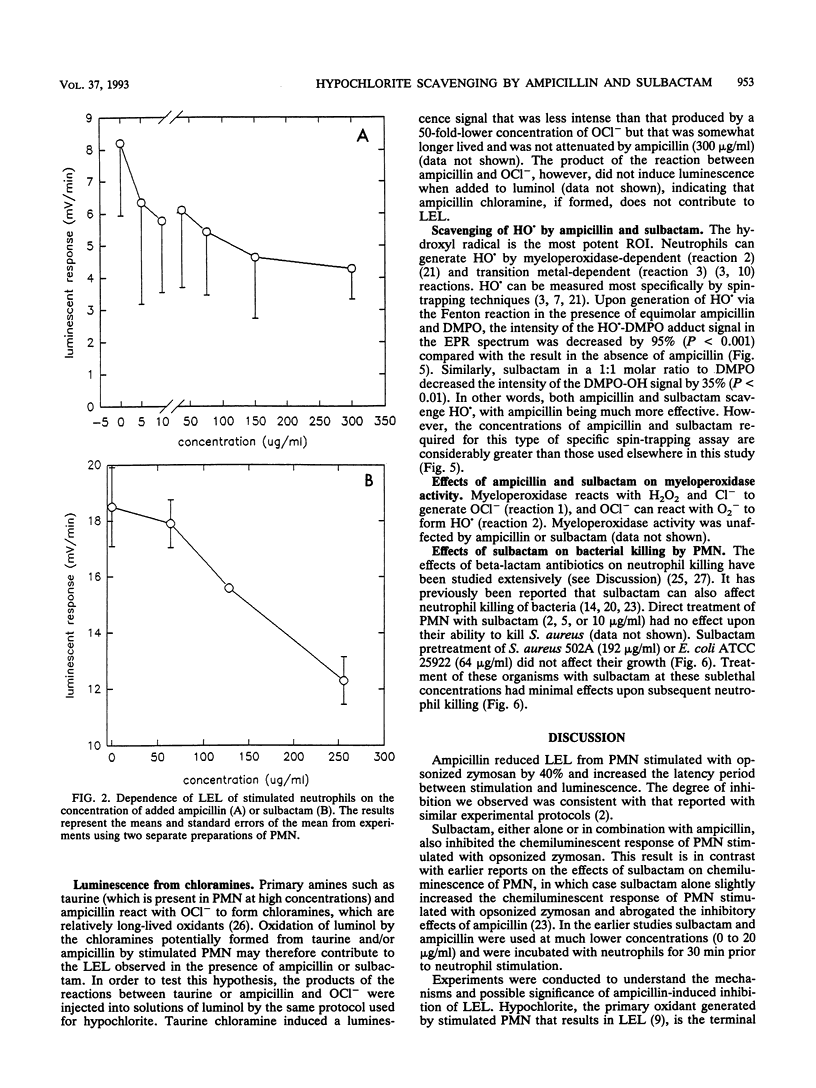

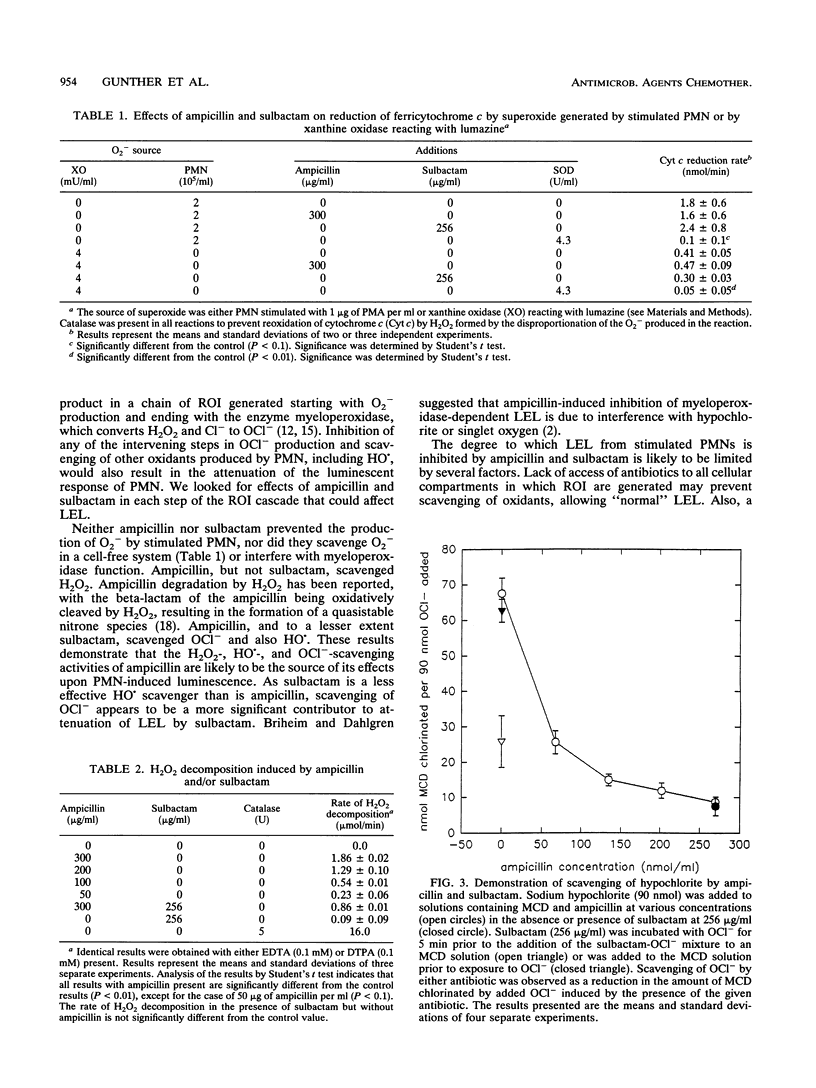

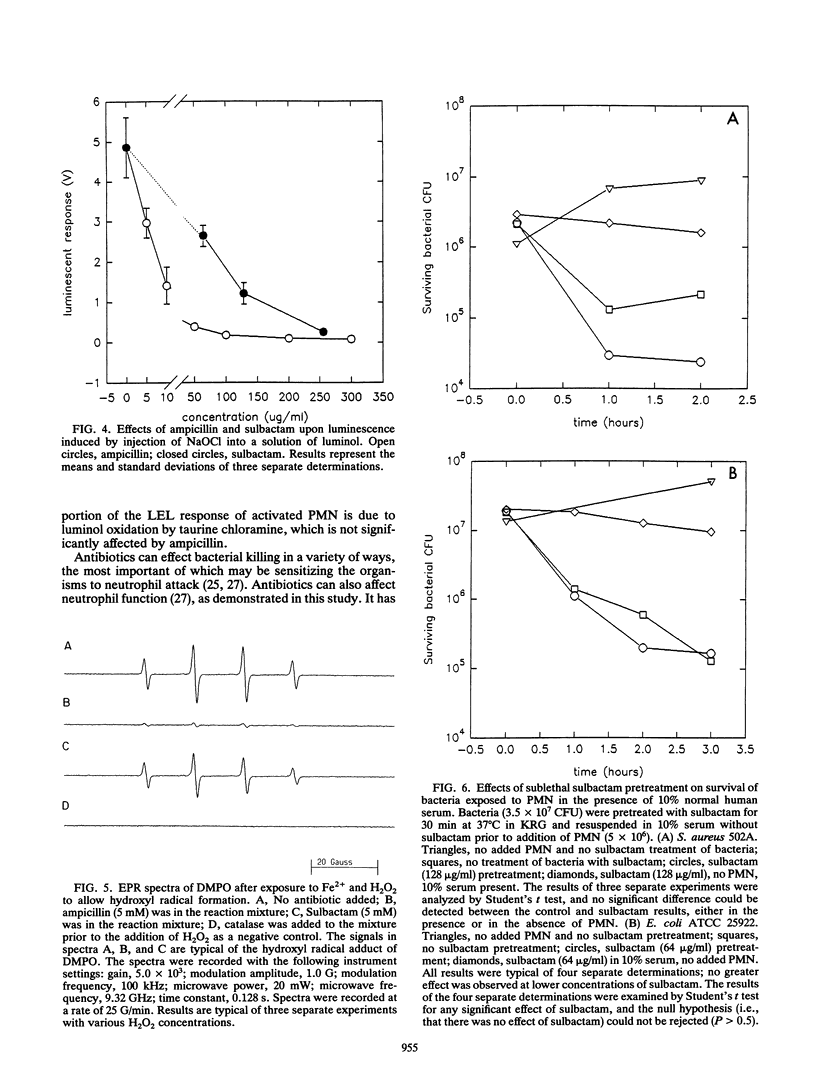

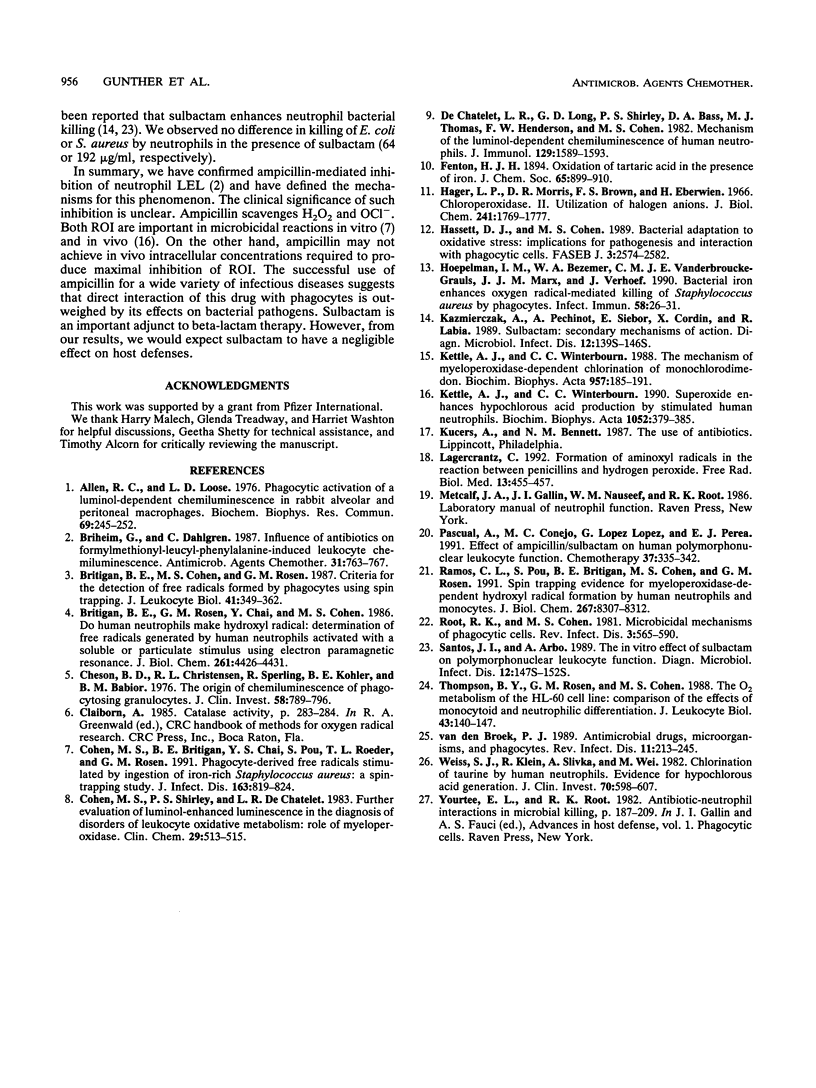

Luminol-enhanced luminescence is a method used to measure formation of reactive oxygen intermediates important in the ability of neutrophils to kill microbes. Several studies have demonstrated that under some conditions of incubation, ampicillin can inhibit neutrophil-derived luminol-enhanced luminescence. We evaluated the mechanism(s) by which ampicillin inhibited the luminescent response of stimulated neutrophils. We also investigated sulbactam, a beta-lactamase inhibitor which has been given in combination with ampicillin and other beta-lactam antibiotics to increase their spectra, for possible similar effects. Both ampicillin and sulbactam attenuated luminol-enhanced luminescence by approximately 40%. Superoxide production was not prevented by added ampicillin, nor was superoxide scavenged by it. Myeloperoxidase reacts with H2O2 and Cl- to generate OCl-, which is believed to be the oxidizer of luminol that is primarily responsible for enhancement of neutrophil-derived luminescence. Hydroxyl radicals (HO.), which may also oxidize luminol, resulting in luminescence, can be formed from O2- and H2O2 via either myeloperoxidase-dependent (involving intermediate OCl-) or myeloperoxidase-independent (through a metal ion catalyst) reactions. Ampicillin scavenged H2O2 and OCl- and prevented 95% of Fenton reaction-generated HO. from reacting with 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide. Sulbactam was found to scavenge OCl- and HO., but less avidly than ampicillin did. Neither ampicillin nor sulbactam inhibited myeloperoxidase activity. Sublethal concentrations of sulbactam had no significant effect on neutrophil killing of Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Our results demonstrate a mechanism(s) by which ampicillin inhibits luminol-enhanced luminescence from stimulated neutrophils, namely, through scavenging of the oxidant(s) primarily responsible for the generation of luminescence.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Allen R. C., Loose L. D. Phagocytic activation of a luminol-dependent chemiluminescence in rabbit alveolar and peritoneal macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1976 Mar 8;69(1):245–252. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(76)80299-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briheim G., Dahlgren C. Influence of antibiotics on formylmethionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine-induced leukocyte chemiluminescence. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987 May;31(5):763–767. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.5.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britigan B. E., Cohen M. S., Rosen G. M. Detection of the production of oxygen-centered free radicals by human neutrophils using spin trapping techniques: a critical perspective. J Leukoc Biol. 1987 Apr;41(4):349–362. doi: 10.1002/jlb.41.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britigan B. E., Rosen G. M., Chai Y., Cohen M. S. Do human neutrophils make hydroxyl radical? Determination of free radicals generated by human neutrophils activated with a soluble or particulate stimulus using electron paramagnetic resonance spectrometry. J Biol Chem. 1986 Apr 5;261(10):4426–4431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheson B. D., Christensen R. L., Sperling R., Kohler B. E., Babior B. M. The origin of the chemiluminescence of phagocytosing granulocytes. J Clin Invest. 1976 Oct;58(4):789–796. doi: 10.1172/JCI108530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M. S., Britigan B. E., Chai Y. S., Pou S., Roeder T. L., Rosen G. M. Phagocyte-derived free radicals stimulated by ingestion of iron-rich Staphylococcus aureus: a spin-trapping study. J Infect Dis. 1991 Apr;163(4):819–824. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.4.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M. S., Shirley P. S., DeChatelet L. R. Further evaluation of luminol-enhanced luminescence in the diagnosis of disorders of leukocyte oxidative metabolism: role of myeloperoxidase. Clin Chem. 1983 Mar;29(3):513–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeChatelet L. R., Long G. D., Shirley P. S., Bass D. A., Thomas M. J., Henderson F. W., Cohen M. S. Mechanism of the luminol-dependent chemiluminescence of human neutrophils. J Immunol. 1982 Oct;129(4):1589–1593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hager L. P., Morris D. R., Brown F. S., Eberwein H. Chloroperoxidase. II. Utilization of halogen anions. J Biol Chem. 1966 Apr 25;241(8):1769–1777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassett D. J., Cohen M. S. Bacterial adaptation to oxidative stress: implications for pathogenesis and interaction with phagocytic cells. FASEB J. 1989 Dec;3(14):2574–2582. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.3.14.2556311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoepelman I. M., Bezemer W. A., Vandenbroucke-Grauls C. M., Marx J. J., Verhoef J. Bacterial iron enhances oxygen radical-mediated killing of Staphylococcus aureus by phagocytes. Infect Immun. 1990 Jan;58(1):26–31. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.1.26-31.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazmierczak A., Pechinot A., Siebor E., Cordin X., Labia R. Sulbactam: secondary mechanisms of action. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1989 Jul-Aug;12(4 Suppl):139S–146S. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(89)90126-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettle A. J., Winterbourn C. C. Superoxide enhances hypochlorous acid production by stimulated human neutrophils. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990 May 22;1052(3):379–385. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(90)90146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettle A. J., Winterbourn C. C. The mechanism of myeloperoxidase-dependent chlorination of monochlorodimedon. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988 Nov 23;957(2):185–191. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(88)90271-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagercrantz C. Formation of aminoxyl radicals in the reaction between penicillins and hydrogen peroxide. Free Radic Biol Med. 1992 Oct;13(4):455–457. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(92)90186-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual A., Conejo M. C., López Lopez G., Perea E. J. Effect of ampicillin/sulbactam on human polymorphonuclear leukocyte function. Chemotherapy. 1991;37(5):335–342. doi: 10.1159/000238876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos C. L., Pou S., Britigan B. E., Cohen M. S., Rosen G. M. Spin trapping evidence for myeloperoxidase-dependent hydroxyl radical formation by human neutrophils and monocytes. J Biol Chem. 1992 Apr 25;267(12):8307–8312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Root R. K., Cohen M. S. The microbicidal mechanisms of human neutrophils and eosinophils. Rev Infect Dis. 1981 May-Jun;3(3):565–598. doi: 10.1093/clinids/3.3.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos J. I., Arbo A. The in vitro effect of sulbactam on polymorphonuclear leukocyte function. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1989 Jul-Aug;12(4 Suppl):147S–152S. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(89)90127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson B. Y., Sivam G., Britigan B. E., Rosen G. M., Cohen M. S. Oxygen metabolism of the HL-60 cell line: comparison of the effects of monocytoid and neutrophilic differentiation. J Leukoc Biol. 1988 Feb;43(2):140–147. doi: 10.1002/jlb.43.2.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss S. J., Klein R., Slivka A., Wei M. Chlorination of taurine by human neutrophils. Evidence for hypochlorous acid generation. J Clin Invest. 1982 Sep;70(3):598–607. doi: 10.1172/JCI110652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Broek P. J. Antimicrobial drugs, microorganisms, and phagocytes. Rev Infect Dis. 1989 Mar-Apr;11(2):213–245. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]