Abstract

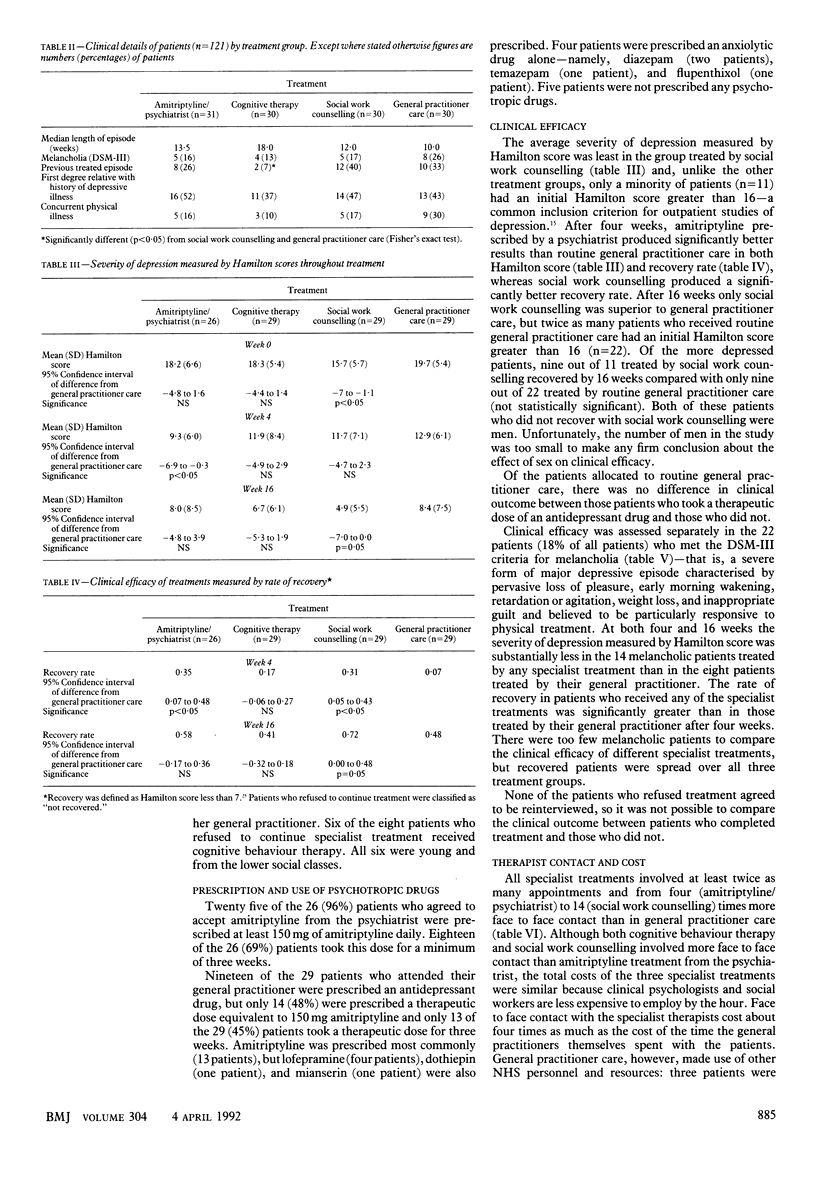

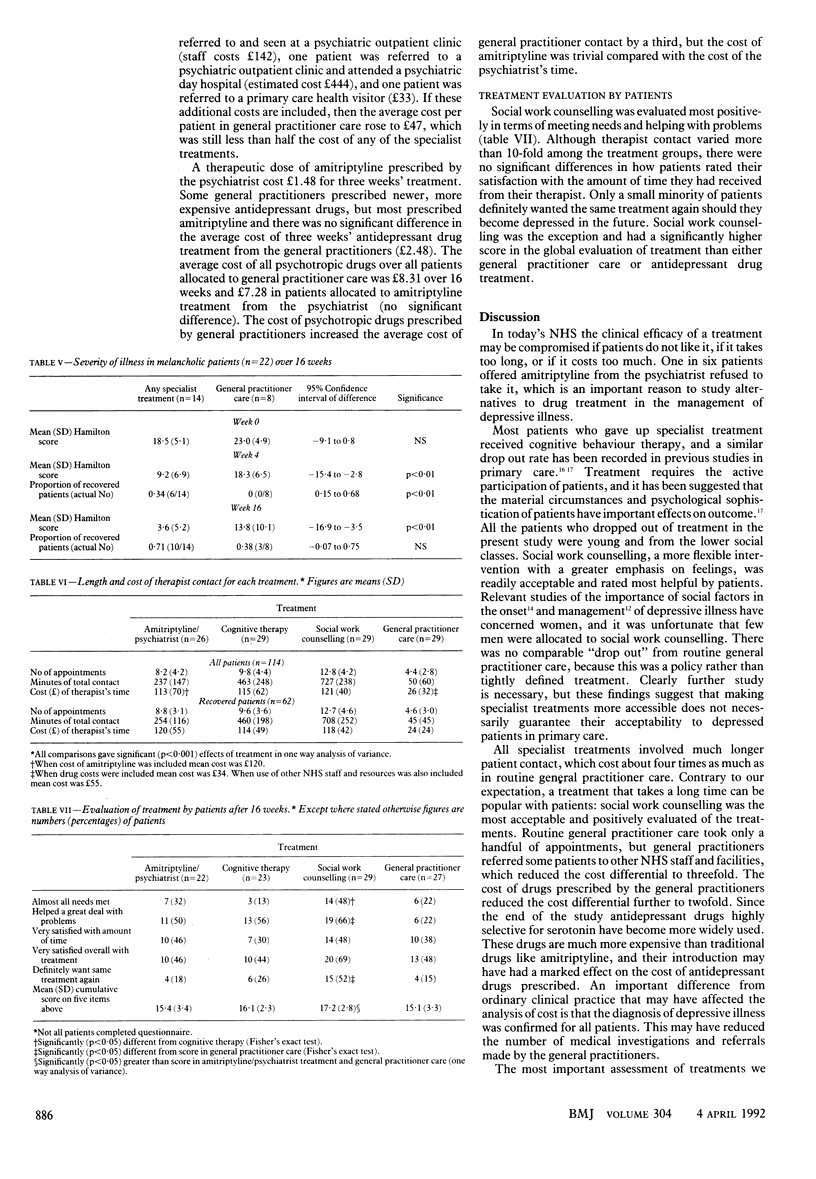

OBJECTIVE--To compare the clinical efficacy, patient satisfaction, and cost of three specialist treatments for depressive illness with routine care by general practitioners in primary care. DESIGN--Prospective, randomised allocation to amitriptyline prescribed by a psychiatrist, cognitive behaviour therapy from a clinical psychologist, counselling and case work by a social worker, or routine care by a general practitioner. SUBJECTS AND SETTING--121 patients aged between 18 and 65 years suffering depressive illness (without psychotic features) meeting the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition for major depressive episode in 14 primary care practices in southern Edinburgh. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES--Standard observer rating of depression at outset and after four and 16 weeks. Numbers of patients recovered at four and 16 weeks. Total length and cost of therapist contact. Structured evaluation of treatment by patients at 16 weeks. RESULTS--Marked improvement in depressive symptoms occurred in all treatment groups over 16 weeks. Any clinical advantages of specialist treatments over routine general practitioner care were small, but specialist treatment involved at least four times as much therapist contact and cost at least twice as much as routine general practitioner care. Psychological treatments, especially social work counselling, were most positively evaluated by patients. CONCLUSIONS--The additional costs associated with specialist treatments of new episodes of mild to moderate depressive illness presenting in primary care were not commensurate with their clinical superiority over routine general practitioner care. A proper cost-benefit analysis requires information about the ability of specialist treatment to prevent future episodes of depression.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Blackburn I. M., Bishop S., Glen A. I., Whalley L. J., Christie J. E. The efficacy of cognitive therapy in depression: a treatment trial using cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy, each alone and in combination. Br J Psychiatry. 1981 Sep;139:181–189. doi: 10.1192/bjp.139.3.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn I. M., Eunson K. M., Bishop S. A two-year naturalistic follow-up of depressed patients treated with cognitive therapy, pharmacotherapy and a combination of both. J Affect Disord. 1986 Jan-Feb;10(1):67–75. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(86)90050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blashki T. G., Mowbray R., Davies B. Controlled trial of amitriptyline in general practice. Br Med J. 1971 Jan 16;1(5741):133–138. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5741.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper B., Sylph J. Life events and the onset of neurotic illness: an investigation in general practice. Psychol Med. 1973 Nov;3(4):421–435. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700054234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkin I., Shea M. T., Watkins J. T., Imber S. D., Sotsky S. M., Collins J. F., Glass D. R., Pilkonis P. A., Leber W. R., Docherty J. P. National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. General effectiveness of treatments. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989 Nov;46(11):971–983. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110013002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glen A. I., Johnson A. L., Shepherd M. Continuation therapy with lithium and amitriptyline in unipolar depressive illness: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Psychol Med. 1984 Feb;14(1):37–50. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700003068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg D. P., Blackwell B. Psychiatric illness in general practice. A detailed study using a new method of case identification. Br Med J. 1970 May 23;1(5707):439–443. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5707.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMILTON M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960 Feb;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D. A. Treatment of depression in general practice. Br Med J. 1973 Apr 7;2(5857):18–20. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5857.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lader M. Advances in drugs - boon or curse? The social implications of psychotropic drugs. R Soc Health J. 1975 Dec;95(6):304–305. doi: 10.1177/146642407509500615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormel J., Van Den Brink W., Koeter M. W., Giel R., Van Der Meer K., Van De Willige G., Wilmink F. W. Recognition, management and outcome of psychological disorders in primary care: a naturalistic follow-up study. Psychol Med. 1990 Nov;20(4):909–923. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700036606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paykel E. S., Hollyman J. A., Freeling P., Sedgwick P. Predictors of therapeutic benefit from amitriptyline in mild depression: a general practice placebo-controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 1988 Jan-Feb;14(1):83–95. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(88)90075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter A. M. Depressive illness in a general practice. A demographic study and a controlled trial of imipramine. Br Med J. 1970 Mar 28;1(5699):773–778. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5699.773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons A. D., Murphy G. E., Levine J. L., Wetzel R. D. Cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy for depression. Sustained improvement over one year. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986 Jan;43(1):43–48. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800010045006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sireling L. I., Freeling P., Paykel E. S., Rao B. M. Depression in general practice: clinical features and comparison with out-patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1985 Aug;147:119–126. doi: 10.1192/bjp.147.2.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale J. D., Fennell M. J., Hibbert G. A., Amies P. L. Cognitive therapy for major depressive disorder in primary care. Br J Psychiatry. 1984 Apr;144:400–406. doi: 10.1192/bjp.144.4.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson J., Rankin H., Ashcroft G. W., Yates C. M., McQueen J. K., Cummings S. W. The treatment of depression in general practice: a comparison of L-tryptophan, amitriptyline, and a combination of L-tryptophan and amitriptyline with placebo. Psychol Med. 1982 Nov;12(4):741–751. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700049047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trethowan W. H. Pills for personal problems. Br Med J. 1975 Sep 27;3(5986):749–751. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5986.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrer P. Drug treatment of psychiatric patients in general practice. Br Med J. 1978 Oct 7;2(6143):1008–1010. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6143.1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson J. M., Barber J. H. Depressive illness in general practice: a pilot study. Health Bull (Edinb) 1981 Mar;39(2):112–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]