Abstract

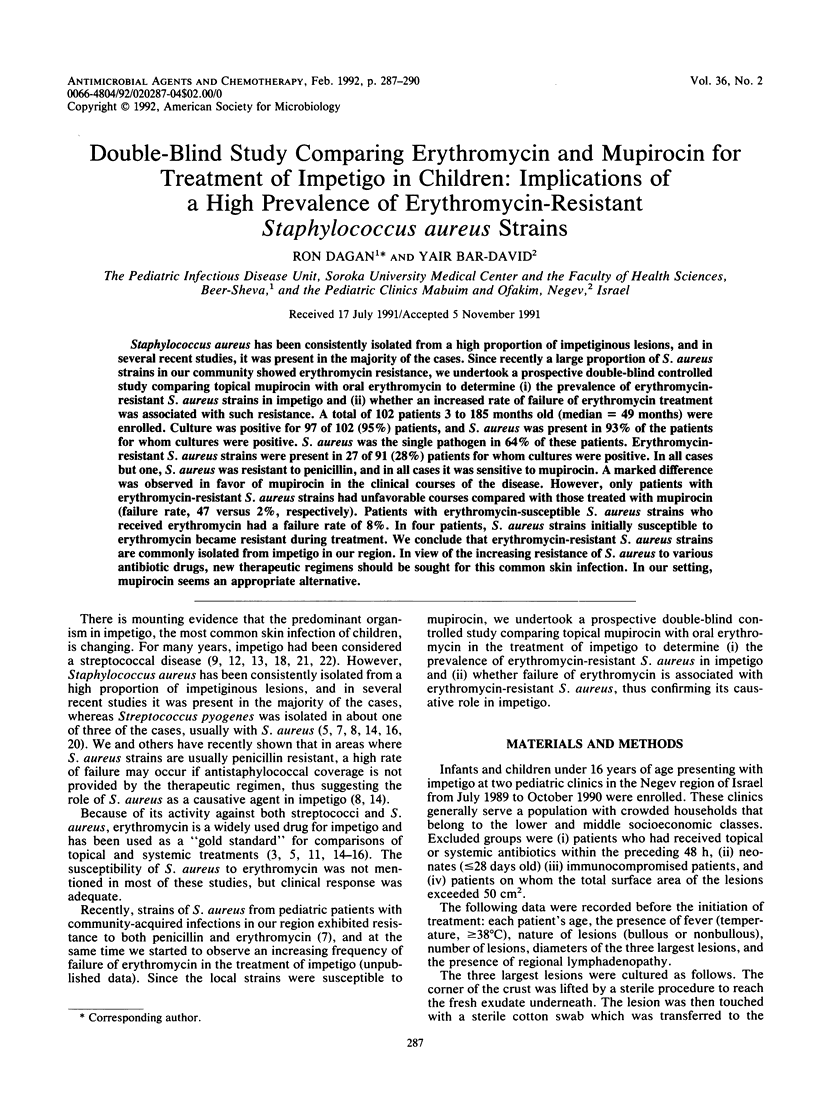

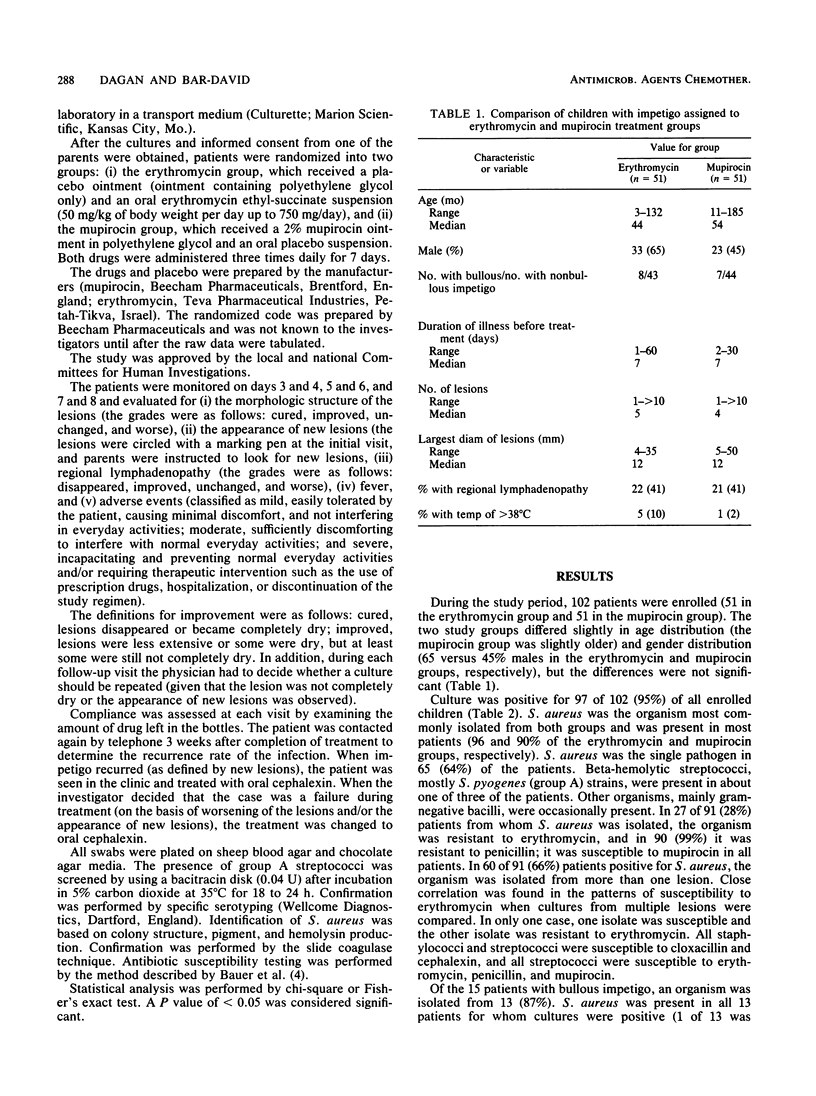

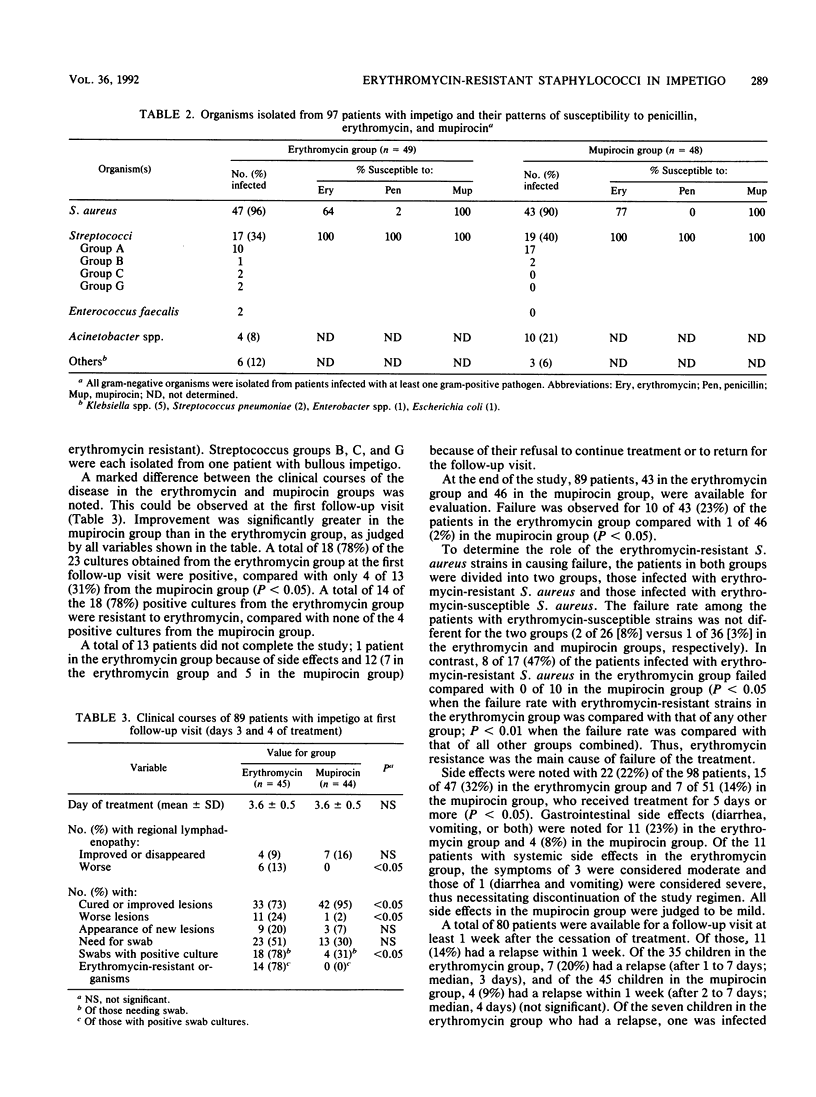

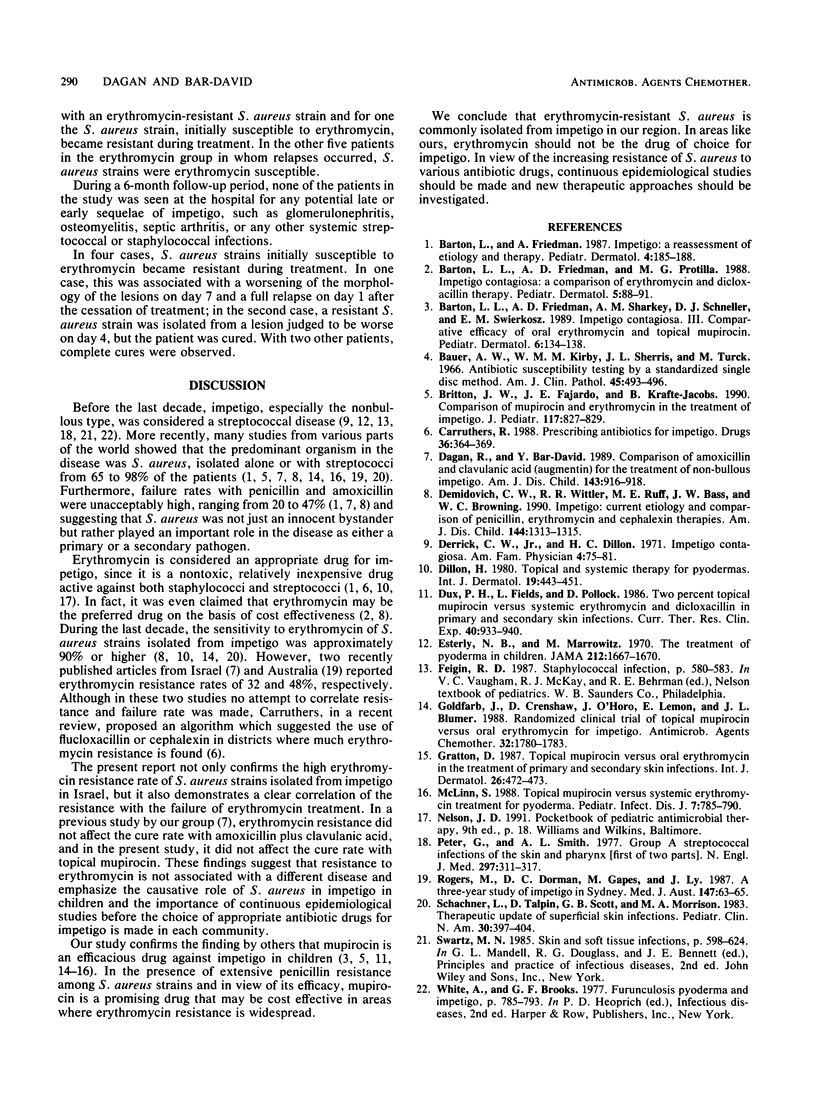

Staphylococcus aureus has been consistently isolated from a high proportion of impetiginous lesions, and in several recent studies, it was present in the majority of the cases. Since recently a large proportion of S. aureus strains in our community showed erythromycin resistance, we undertook a prospective double-blind controlled study comparing topical mupirocin with oral erythromycin to determine (i) the prevalence of erythromycin-resistant S. aureus strains in impetigo and (ii) whether an increased rate of failure of erythromycin treatment was associated with such resistance. A total of 102 patients 3 to 185 months old (median = 49 months) were enrolled. Culture was positive for 97 of 102 (95%) patients, and S. aureus was present in 93% of the patients for whom cultures were positive. S. aureus was the single pathogen in 64% of these patients. Erythromycin-resistant S. aureus strains were present in 27 of 91 (28%) patients for whom cultures were positive. In all cases but one, S. aureus was resistant to penicillin, and in all cases it was sensitive to mupirocin. A marked difference was observed in favor of mupirocin in the clinical courses of the disease. However, only patients with erythromycin-resistant S. aureus strains had unfavorable courses compared with those treated with mupirocin (failure rate, 47 versus 2%, respectively). Patients with erythromycin-susceptible S. aureus strains who received erythromycin had a failure rate of 8%. In four patients, S. aureus strains initially susceptible to erythromycin became resistant during treatment. We conclude that erythromycin-resistant S. aureus strains are commonly isolated from impetigo in our region.(ABSTRACT TRUNCATED AT 250 WORDS)

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Barton L. L., Friedman A. D. Impetigo: a reassessment of etiology and therapy. Pediatr Dermatol. 1987 Nov;4(3):185–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1987.tb00776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton L. L., Friedman A. D., Portilla M. G. Impetigo contagiosa: a comparison of erythromycin and dicloxacillin therapy. Pediatr Dermatol. 1988 May;5(2):88–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1988.tb01144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton L. L., Friedman A. D., Sharkey A. M., Schneller D. J., Swierkosz E. M. Impetigo contagiosa III. Comparative efficacy of oral erythromycin and topical mupirocin. Pediatr Dermatol. 1989 Jun;6(2):134–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1989.tb01012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer A. W., Kirby W. M., Sherris J. C., Turck M. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disk method. Am J Clin Pathol. 1966 Apr;45(4):493–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton J. W., Fajardo J. E., Krafte-Jacobs B. Comparison of mupirocin and erythromycin in the treatment of impetigo. J Pediatr. 1990 Nov;117(5):827–829. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)83352-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers R. Prescribing antibiotics for impetigo. Drugs. 1988 Sep;36(3):364–369. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198836030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagan R., Bar-David Y. Comparison of amoxicillin and clavulanic acid (augmentin) for the treatment of nonbullous impetigo. Am J Dis Child. 1989 Aug;143(8):916–918. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1989.02150200068020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demidovich C. W., Wittler R. R., Ruff M. E., Bass J. W., Browning W. C. Impetigo. Current etiology and comparison of penicillin, erythromycin, and cephalexin therapies. Am J Dis Child. 1990 Dec;144(12):1313–1315. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1990.02150360037015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrick C. W., Jr, Dillon H. C., Jr Impetigo contagiosa. Am Fam Physician. 1971 Oct;4(4):75–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon H. C., Jr Topical and systemic therapy for pyodermas. Int J Dermatol. 1980 Oct;19(8):443–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1980.tb05895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esterly N. B., Markowitz M. The treatment of pyoderma in children. JAMA. 1970 Jun 8;212(10):1667–1670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfarb J., Crenshaw D., O'Horo J., Lemon E., Blumer J. L. Randomized clinical trial of topical mupirocin versus oral erythromycin for impetigo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988 Dec;32(12):1780–1783. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.12.1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratton D. Topical mupirocin versus oral erythromycin in the treatment of primary and secondary skin infections. Int J Dermatol. 1987 Sep;26(7):472–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1987.tb00600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLinn S. Topical mupirocin vs. systemic erythromycin treatment for pyoderma. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1988 Nov;7(11):785–790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter G., Smith A. L. Group A streptococcal infections of the skin and pharynx (first of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1977 Aug 11;297(6):311–317. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197708112970606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers M., Dorman D. C., Gapes M., Ly J. A three-year study of impetigo in Sydney. Med J Aust. 1987 Jul 20;147(2):63–65. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1987.tb133260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachner L., Taplin D., Scott G. B., Morrison M. A therapeutic update of superficial skin infections. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1983 Apr;30(2):397–404. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)34366-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]