Abstract

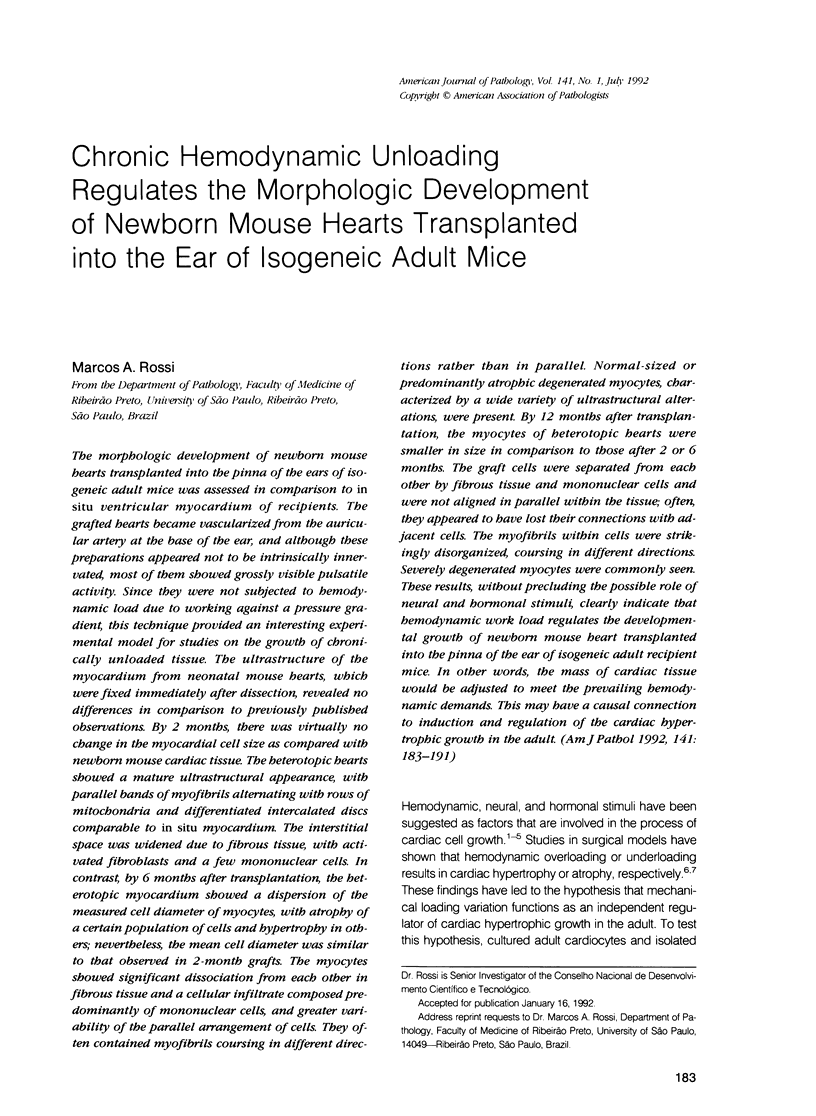

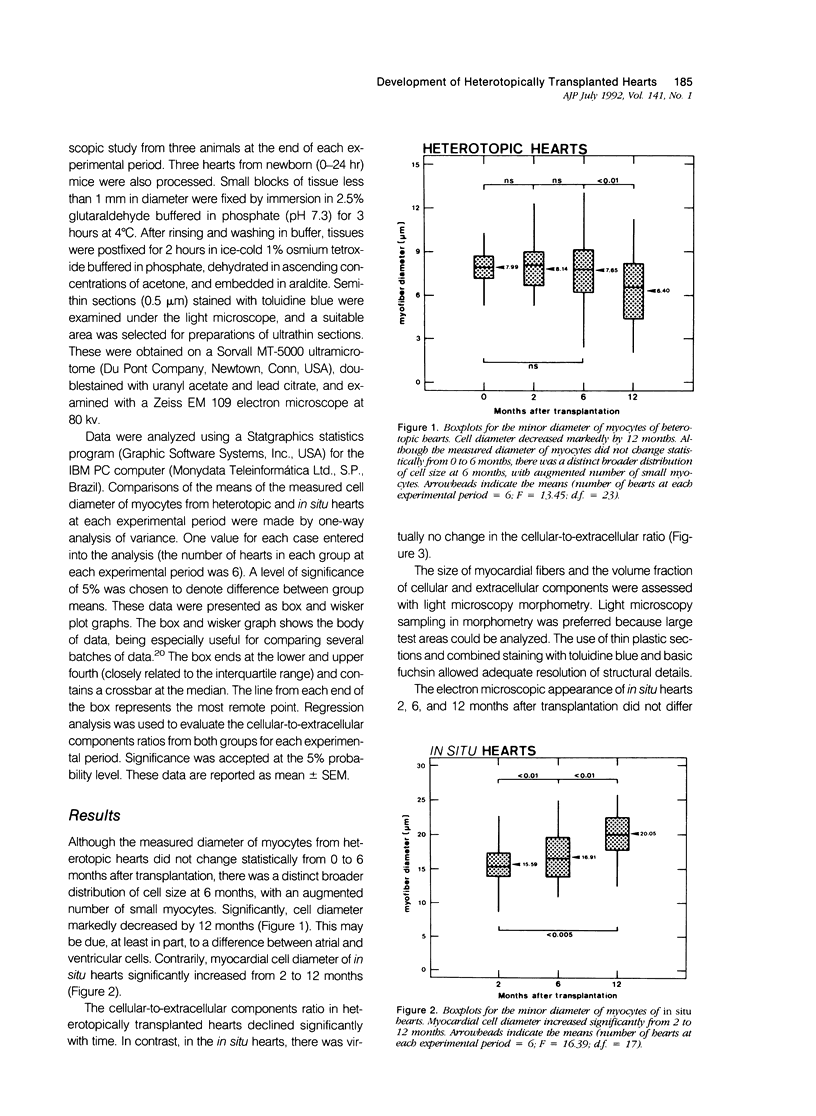

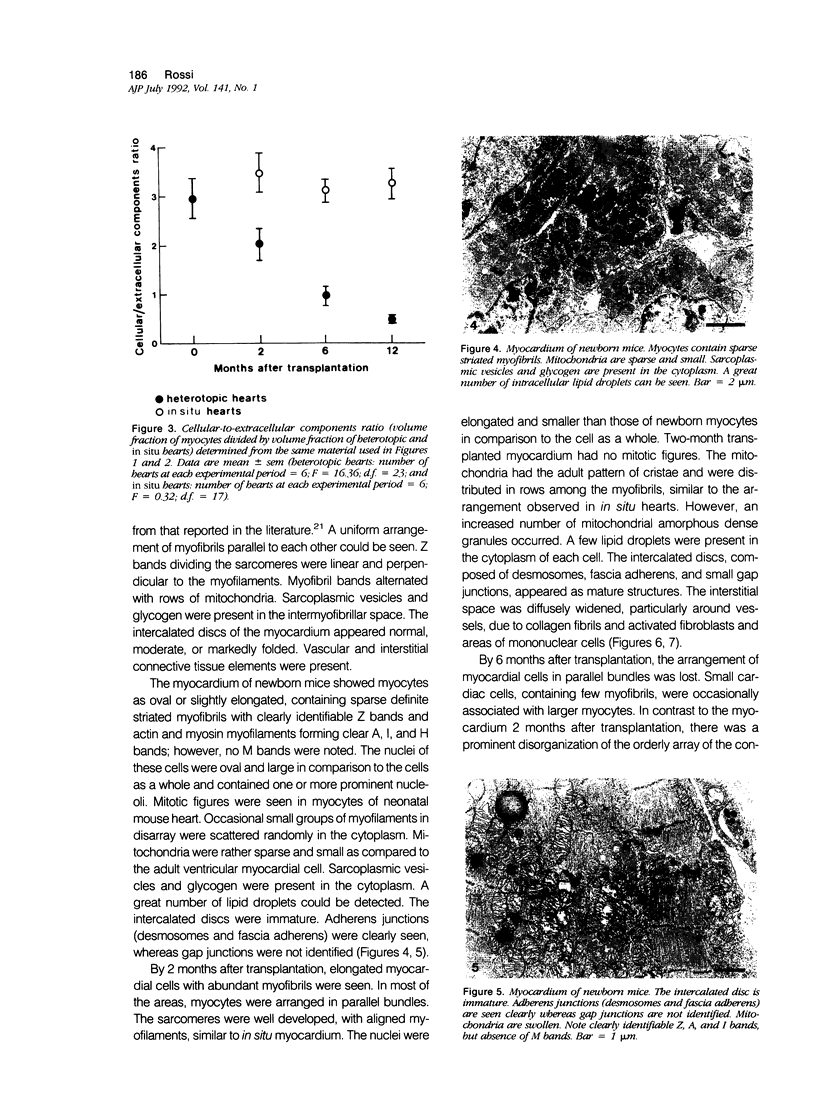

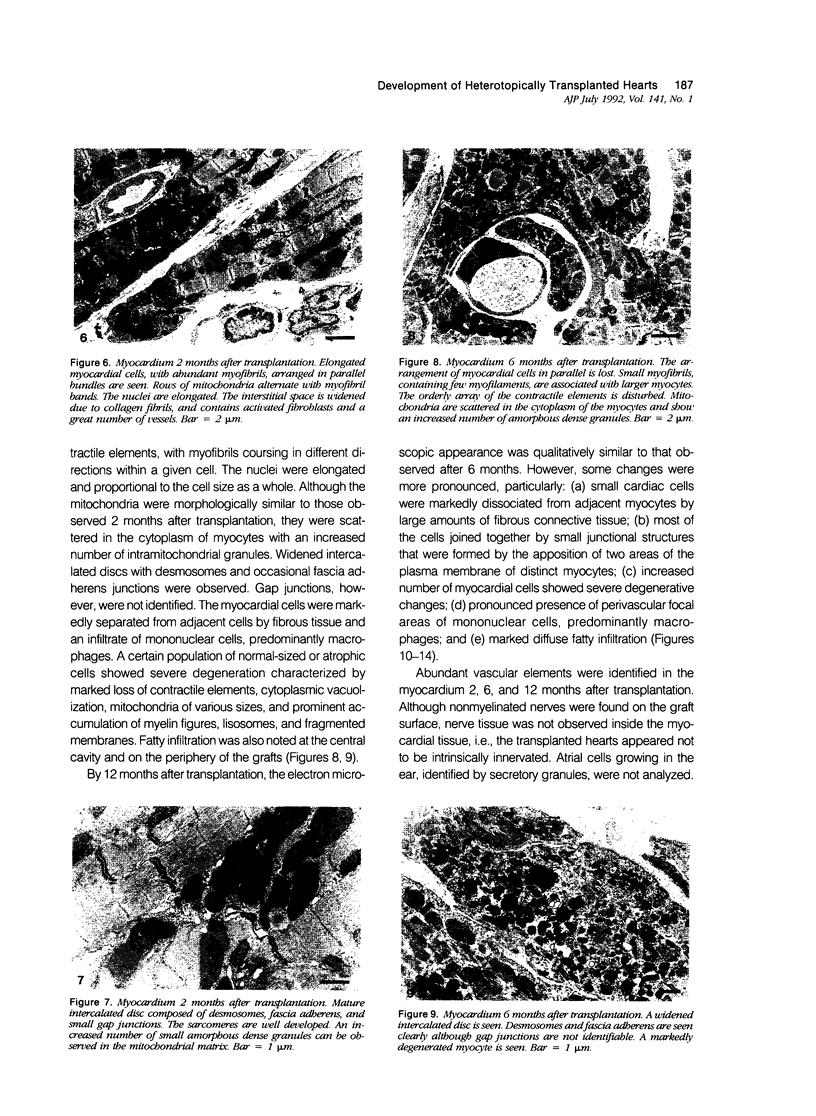

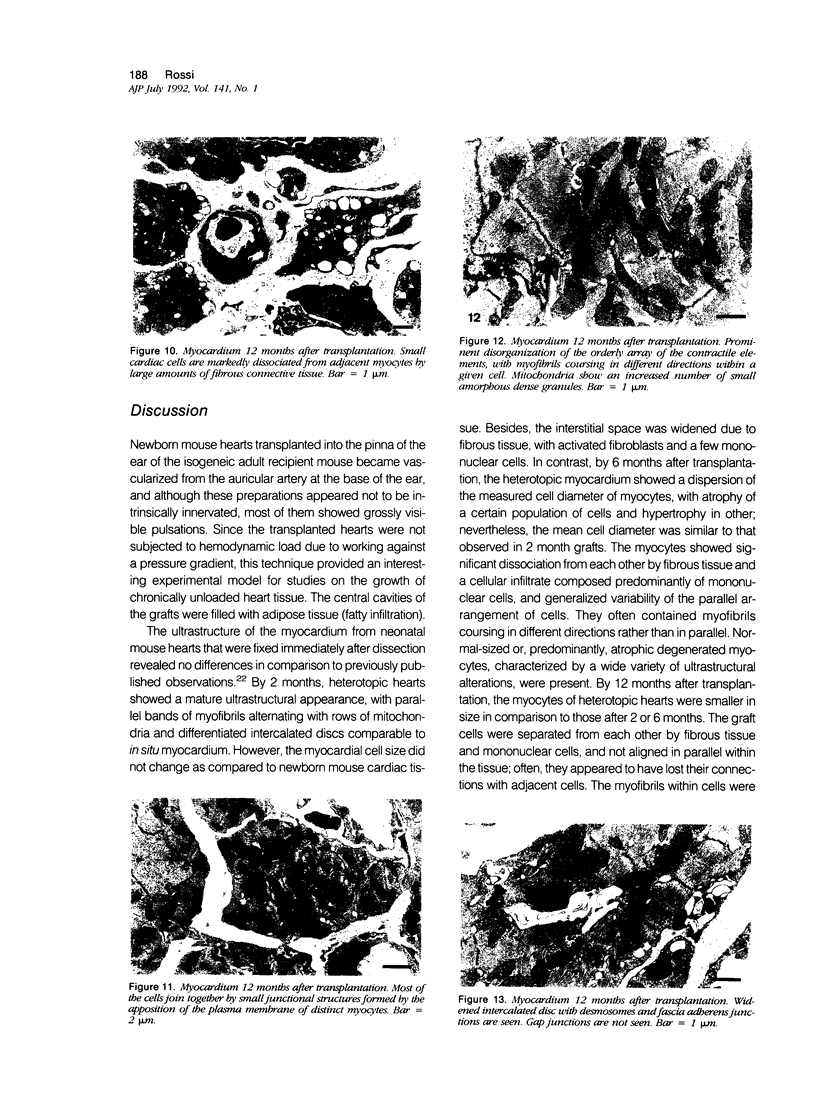

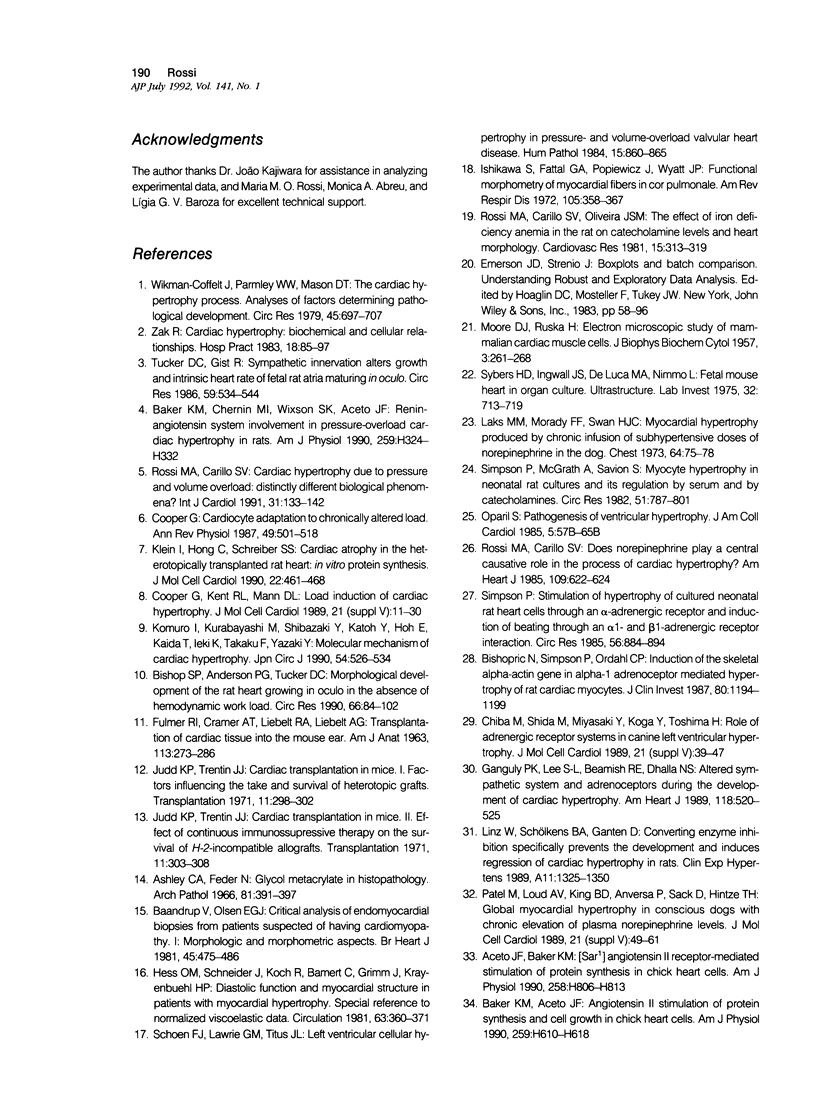

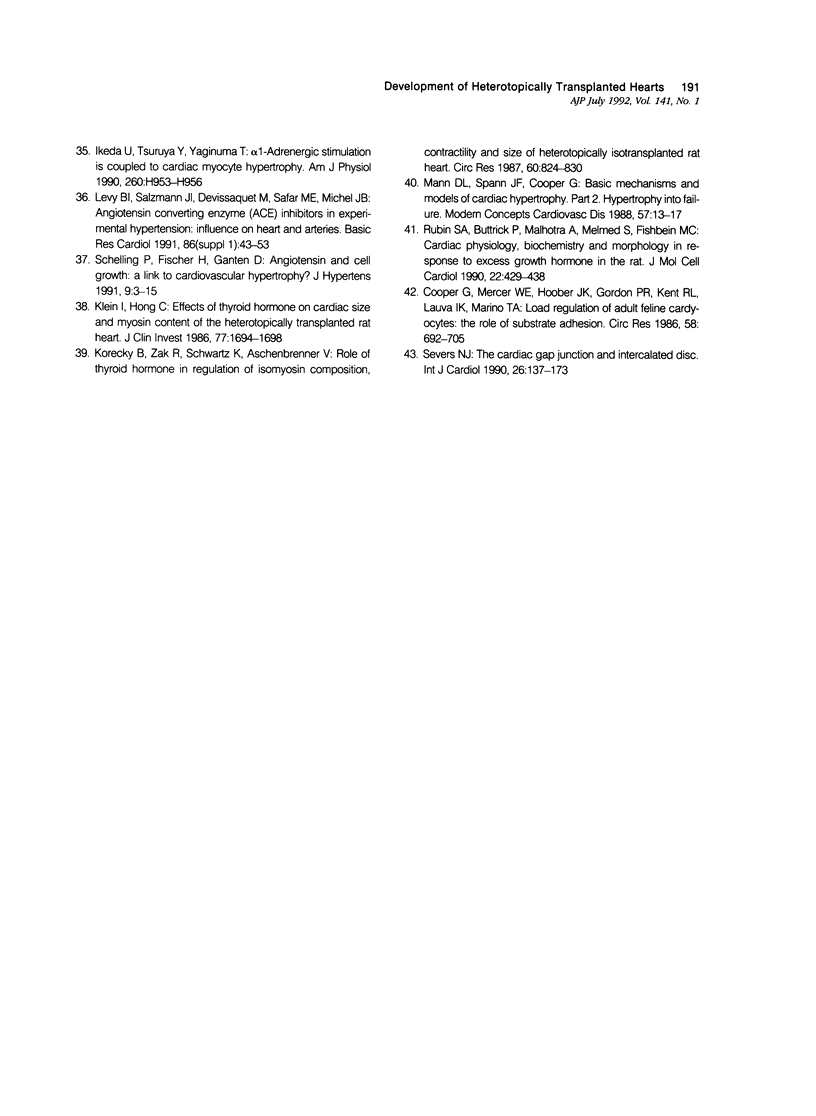

The morphologic development of newborn mouse hearts transplanted into the pinna of the ears of isogeneic adult mice was assessed in comparison to in situ ventricular myocardium of recipients. The grafted hearts became vascularized from the auricular artery at the base of the ear, and although these preparations appeared not to be intrinsically innervated, most of them showed grossly visible pulsatile activity. Since they were not subjected to hemodynamic load due to working against a pressure gradient, this technique provided an interesting experimental model for studies on the growth of chronically unloaded tissue. The ultrastructure of the myocardium from neonatal mouse hearts, which were fixed immediately after dissection, revealed no differences in comparison to previously published observations. By 2 months, there was virtually no change in the myocardial cell size as compared with newborn mouse cardiac tissue. The heterotopic hearts showed a mature ultrastructural appearance, with parallel bands of myofibrils alternating with rows of mitochondria and differentiated intercalated discs comparable to in situ myocardium. The interstitial space was widened due to fibrous tissue, with activated fibroblasts and a few mononuclear cells. In contrast, by 6 months after transplantation, the heterotopic myocardium showed a dispersion of the measured cell diameter of myocytes, with atrophy of a certain population of cells and hypertrophy in others; nevertheless, the mean cell diameter was similar to that observed in 2-month grafts. The myocytes showed significant dissociation from each other in fibrous tissue and a cellular infiltrate composed predominantly of mononuclear cells, and greater variability of the parallel arrangement of cells. They often contained myofibrils coursing in different directions rather than in parallel. Normal-sized or predominantly atrophic degenerated myocytes, characterized by a wide variety of ultrastructural alterations, were present. By 12 months after transplantation, the myocytes of heterotopic hearts were smaller in size in comparison to those after 2 or 6 months. The graft cells were separated from each other by fibrous tissue and mononuclear cells and were not aligned in parallel within the tissue; often, they appeared to have lost their connections with adjacent cells. The myofibrils within cells were strikingly disorganized, coursing in different directions. Severely degenerated myocytes were commonly seen. These results, without precluding the possible role of neural and hormonal stimuli, clearly indicate that hemodynamic work load regulates the developmental growth of newborn mouse heart transplanted into the pinna of the ear of isogeneic adult recipient mice. In other words, the mass of cardiac tissue would be adjusted to meet the prevailing hemodynamic demands.(ABSTRACT TRUNCATED AT 400 WORDS)

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aceto J. F., Baker K. M. [Sar1]angiotensin II receptor-mediated stimulation of protein synthesis in chick heart cells. Am J Physiol. 1990 Mar;258(3 Pt 2):H806–H813. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.258.3.H806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley C. A., Feder N. Glycol methacrylate in histopathology. A study of central necrosis of the liver using a water-miscible plastic as embedding medium. Arch Pathol. 1966 May;81(5):391–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baandrup U., Olsen E. G. Critical analysis of endomyocardial biopsies from patients suspected of having cardiomyopathy. I: Morphological and morphometric aspects. Br Heart J. 1981 May;45(5):475–486. doi: 10.1136/hrt.45.5.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker K. M., Aceto J. F. Angiotensin II stimulation of protein synthesis and cell growth in chick heart cells. Am J Physiol. 1990 Aug;259(2 Pt 2):H610–H618. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.2.H610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker K. M., Chernin M. I., Wixson S. K., Aceto J. F. Renin-angiotensin system involvement in pressure-overload cardiac hypertrophy in rats. Am J Physiol. 1990 Aug;259(2 Pt 2):H324–H332. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.2.H324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop S. P., Anderson P. G., Tucker D. C. Morphological development of the rat heart growing in oculo in the absence of hemodynamic work load. Circ Res. 1990 Jan;66(1):84–102. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishopric N. H., Simpson P. C., Ordahl C. P. Induction of the skeletal alpha-actin gene in alpha 1-adrenoceptor-mediated hypertrophy of rat cardiac myocytes. J Clin Invest. 1987 Oct;80(4):1194–1199. doi: 10.1172/JCI113179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba M., Shida M., Miyazaki Y., Koga Y., Toshima H. Role of adrenergic receptor systems in canine left ventricular hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1989 Dec;21 (Suppl 5):39–47. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(89)90770-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper G., 4th Cardiocyte adaptation to chronically altered load. Annu Rev Physiol. 1987;49:501–518. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.49.030187.002441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper G., 4th, Kent R. L., Mann D. L. Load induction of cardiac hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1989 Dec;21 (Suppl 5):11–30. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(89)90768-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper G., 4th, Mercer W. E., Hoober J. K., Gordon P. R., Kent R. L., Lauva I. K., Marino T. A. Load regulation of the properties of adult feline cardiocytes. The role of substrate adhesion. Circ Res. 1986 May;58(5):692–705. doi: 10.1161/01.res.58.5.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FULMER R. I., CRAMER A. T., LIEBELT R. A., LIEBELT A. G. TRANSPLANTATION OF CARDIAC TISSUE INTO THE MOUSE EAR. Am J Anat. 1963 Sep;113:273–285. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001130206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly P. K., Lee S. L., Beamish R. E., Dhalla N. S. Altered sympathetic system and adrenoceptors during the development of cardiac hypertrophy. Am Heart J. 1989 Sep;118(3):520–525. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(89)90267-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess O. M., Schneider J., Koch R., Bamert C., Grimm J., Krayenbuehl H. P. Diastolic function and myocardial structure in patients with myocardial hypertrophy. Special reference to normalized viscoelastic data. Circulation. 1981 Feb;63(2):360–371. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.63.2.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda U., Tsuruya Y., Yaginuma T. Alpha 1-adrenergic stimulation is coupled to cardiac myocyte hypertrophy. Am J Physiol. 1991 Mar;260(3 Pt 2):H953–H956. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.260.3.H953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa S., Fattal G. A., Popiewicz J., Wyatt J. P. Functional morphometry of myocardial fibers in cor pulmonale. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1972 Mar;105(3):358–367. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1972.105.3.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd K. P., Trentin J. J. Cardiac transplantation in mice. I. Factors influencing the take and survival of heterotopic grafts. Transplantation. 1971 Mar;11(3):298–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd K. P., Trentin J. J. Cardiac transplantation in mice. II. Effect of continuous immunosuppressive therapy on the survival of H-2-incompatible allografts. Transplantation. 1971 Mar;11(3):303–308. doi: 10.1097/00007890-197103000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein I., Hong C. Effects of thyroid hormone on cardiac size and myosin content of the heterotopically transplanted rat heart. J Clin Invest. 1986 May;77(5):1694–1698. doi: 10.1172/JCI112488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein I., Hong C., Schreiber S. S. Cardiac atrophy in the heterotopically transplanted rat heart: in vitro protein synthesis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1990 Apr;22(4):461–468. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(90)91481-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komuro I., Kurabayashi M., Shibazaki Y., Katoh Y., Hoh E., Kaida T., Ieki K., Takaku F., Yazaki Y. Molecular mechanism of cardiac hypertrophy. Jpn Circ J. 1990 May;54(5):526–534. doi: 10.1253/jcj.54.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korecky B., Zak R., Schwartz K., Aschenbrenner V. Role of thyroid hormone in regulation of isomyosin composition, contractility, and size of heterotopically isotransplanted rat heart. Circ Res. 1987 Jun;60(6):824–830. doi: 10.1161/01.res.60.6.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laks M. M., Morady F., Swan H. J. Myocardial hypertrophy produced by chronic infusion of subhypertensive doses of norepinephrine in the dog. Chest. 1973 Jul;64(1):75–78. doi: 10.1378/chest.64.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy B. I., Salzmann J. L., Devissaguet M., Safar M. E., Michel J. B. Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors in experimental hypertension: influence on heart and arteries. Basic Res Cardiol. 1991;86 (Suppl 1):43–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linz W., Schölkens B. A., Ganten D. Converting enzyme inhibition specifically prevents the development and induces regression of cardiac hypertrophy in rats. Clin Exp Hypertens A. 1989;11(7):1325–1350. doi: 10.3109/10641968909038172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOORE D. H., RUSKA H. Electron microscope study of mammalian cardiac muscle cells. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1957 Mar 25;3(2):261–268. doi: 10.1083/jcb.3.2.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oparil S. Pathogenesis of ventricular hypertrophy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985 Jun;5(6 Suppl):57B–65B. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(85)80528-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel M. B., Loud A. V., King B. D., Anversa P., Sack D., Hintze T. H. Global myocardial hypertrophy in conscious dogs with chronic elevation of plasma norepinephrine levels. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1989 Dec;21 (Suppl 5):49–61. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(89)90771-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi M. A., Carillo S. V. Cardiac hypertrophy due to pressure and volume overload: distinctly different biological phenomena? Int J Cardiol. 1991 May;31(2):133–141. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(91)90207-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi M. A., Carillo S. V. Does norepinephrine play a central causative role in the process of cardiac hypertrophy? Am Heart J. 1985 Mar;109(3 Pt 1):622–624. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(85)90582-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi M. A., Carillo S. V., Oliveira J. S. The effect of iron deficiency anemia in the rat on catecholamine levels and heart morphology. Cardiovasc Res. 1981 Jun;15(6):313–319. doi: 10.1093/cvr/15.6.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin S. A., Buttrick P., Malhotra A., Melmed S., Fishbein M. C. Cardiac physiology, biochemistry and morphology in response to excess growth hormone in the rat. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1990 Apr;22(4):429–438. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(90)91478-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schelling P., Fischer H., Ganten D. Angiotensin and cell growth: a link to cardiovascular hypertrophy? J Hypertens. 1991 Jan;9(1):3–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoen F. J., Lawrie G. M., Titus J. L. Left ventricular cellular hypertrophy in pressure- and volume-overload valvular heart disease. Hum Pathol. 1984 Sep;15(9):860–865. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(84)80147-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severs N. J. The cardiac gap junction and intercalated disc. Int J Cardiol. 1990 Feb;26(2):137–173. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(90)90030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson P., McGrath A., Savion S. Myocyte hypertrophy in neonatal rat heart cultures and its regulation by serum and by catecholamines. Circ Res. 1982 Dec;51(6):787–801. doi: 10.1161/01.res.51.6.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson P. Stimulation of hypertrophy of cultured neonatal rat heart cells through an alpha 1-adrenergic receptor and induction of beating through an alpha 1- and beta 1-adrenergic receptor interaction. Evidence for independent regulation of growth and beating. Circ Res. 1985 Jun;56(6):884–894. doi: 10.1161/01.res.56.6.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sybers H. D., Ingwall J. S., De Luca M. A. Fetal mouse heart in organ structure: ultrastructure. Lab Invest. 1975 Jun;32(6):713–719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker D. C., Gist R. Sympathetic innervation alters growth and intrinsic heart rate of fetal rat atria maturing in oculo. Circ Res. 1986 Nov;59(5):534–544. doi: 10.1161/01.res.59.5.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikman-Coffelt J., Parmley W. W., Mason D. T. The cardiac hypertrophy process. Analyses of factors determining pathological vs. physiological development. Circ Res. 1979 Dec;45(6):697–707. doi: 10.1161/01.res.45.6.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zak R. Cardiac hypertrophy: biochemical and cellular relationships. Hosp Pract (Off Ed) 1983 Mar;18(3):85–97. doi: 10.1080/21548331.1983.11702494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]