Abstract

Voltage-gated K+ channels are tetramers with each subunit containing six (S1–S6) putative membrane spanning segments. The fifth through sixth transmembrane segments (S5–S6) from each of four subunits assemble to form a central pore domain. A growing body of evidence suggests that the first four segments (S1–S4) comprise a domain-like voltage-sensing structure. While the topology of this region is reasonably well defined, the secondary and tertiary structures of these transmembrane segments are not. To explore the secondary structure of the voltage-sensing domains, we used alanine-scanning mutagenesis through the region encompassing the first four transmembrane segments in the drk1 voltage-gated K+ channel. We examined the mutation-induced perturbation in gating free energy for periodicity characteristic of α-helices. Our results are consistent with at least portions of S1, S2, S3, and S4 adopting α-helical secondary structure. In addition, both the S1–S2 and S3–S4 linkers exhibited substantial helical character. The distribution of gating perturbations for S1 and S2 suggest that these two helices interact primarily with two environments. In contrast, the distribution of perturbations for S3 and S4 were more complex, suggesting that the latter two helices make more extensive protein contacts, possibly interfacing directly with the shell of the pore domain.

Keywords: secondary structure, scanning mutagenesis, amphipathic, Fourier transform, voltage-dependent gating

INTRODUCTION

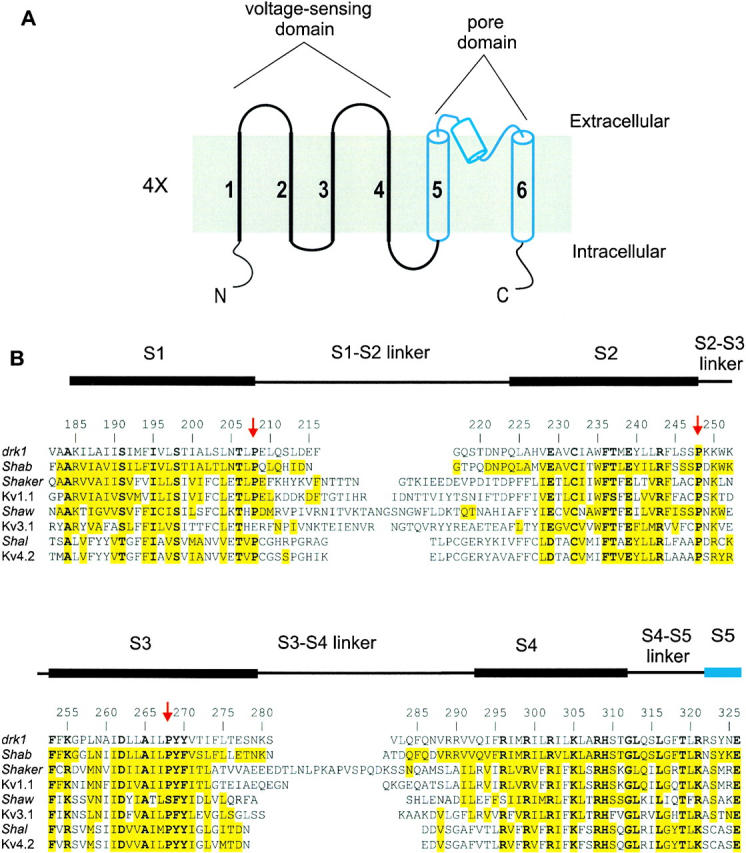

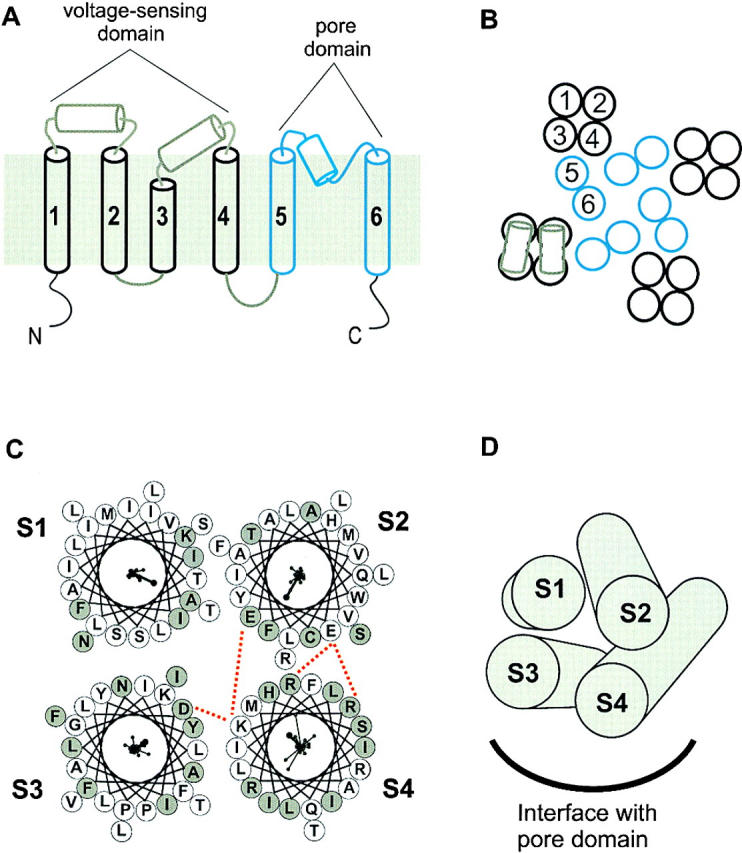

The voltage-gated K+ channels comprise a large family of tetrameric membrane proteins that open and close in response to changes in membrane voltage. Based on hydrophobicity analysis, each subunit in the tetramer contains six putative transmembrane segments, termed S1 through S6 (Fig. 1 A). The central pore domain, which contains the K+ selective ion conduction pathway, is formed by the assembly of the S5 through S6 regions (MacKinnon and Miller 1989; MacKinnon and Yellen 1990; Hartmann et al. 1991; MacKinnon 1991; Yellen et al. 1991; Yool and Schwarz 1991; Liman et al. 1992; Heginbotham et al. 1994; Ranganathan et al. 1996; Armstrong and Hille 1998). The KcsA K+ channel, a tetrameric membrane protein of known three-dimensional structure, is a relatively simple prokaryotic K+ channel with two transmembrane segments in each subunit that are homologous to S5–S6 in voltage-gated K+ channels (Schrempf et al. 1995; Doyle et al. 1998). Both sequence homology and the conservation of pore-blocking toxin receptors suggests that the structure of the pore domain of voltage-gated channels is likely to be similar to that of KcsA (Schrempf et al. 1995; Doyle et al. 1998; MacKinnon et al. 1998). Thus, both S5 and S6 are undoubtedly membrane spanning α-helices with the S5–S6 linker, the most conserved region of all K+ channels, forming a short pore helix and the selectivity filter.

Figure 1.

Topology and sequence alignment of voltage-gated K+ channels. (A) Putative topology of a single subunit of the voltage-gated K+ channel with six putative transmembrane segments. Top is extracellular and the bottom is intracellular. In the tetramer, the coassembly of S5–S6 segments form the pore domain. The first four transmembrane segments form a single voltage-sensing domain with four of these domains surrounding the central pore domain. (B) Sequence alignment between the four classes of voltage-gated K+ channels in a region spanning four putative transmembrane segments (S1–S4) and linkers. Black bars above the sequence represent the approximate positions of the four transmembrane segments as indicated by the Kyte-Doolittle hydrophobicity analysis. Residue numbering is for the drk1 K+ channel. Yellow highlighting indicates similarity to drk1. Bold letters indicate residues that are highly conserved in all the voltage-gated K+ channels. Red arrows mark three highly conserved proline residues.

The first four transmembrane segments (S1–S4) of voltage-gated K+ channels are not present in the simple pore K+ channels, like KcsA and the inward rectifier K+ channels, and appear to underlie their unique voltage-sensing capabilities (Armstrong and Hille 1998). However, when compared with the pore domain, much less is known about the structure of this voltage-sensing region of the channel. The presence of four transmembrane segments outside the pore domain is supported by hydrophobicity analysis (Schwarz et al. 1988; Butler et al. 1989; Frech et al. 1989; Stühmer et al. 1989; Durell et al. 1998) and sequence comparisons showing that highly conserved residues tend to cluster into four main groups (Fig. 1, bold residues). In addition, the numerous topological constraints that support the membrane-folding model shown in Fig. 1 A argue for the presence of four transmembrane segments in this region (Hoshi et al. 1990; Zagotta et al. 1990; Santacruz-Toloza et al. 1994; Holmgren et al. 1996; Swartz and MacKinnon 1997a,Swartz and MacKinnon 1997b; Larsson et al. 1996; Yang et al. 1996; Yusaf et al. 1996). There is considerable evidence suggesting that most, if not all, of the first four transmembrane segments participate in sensing changes in membrane voltage. This is particularly true for S4, an unusual transmembrane segment that contains a large number of basic residues (Papazian et al. 1991; Liman et al. 1991; Perozo et al. 1994; Aggarwal and MacKinnon 1996; Larsson et al. 1996; Mannuzzu et al. 1996; Seoh et al. 1996; Yang et al. 1996; Yusaf et al. 1996; Smith-Maxwell et al. 1998a,Smith-Maxwell et al. 1998b; Ledwell and Aldrich 1999). In addition, a growing body of evidence suggests that S2 and S3 may also be involved in voltage sensing (Papazian et al. 1995; Planells-Cases et al. 1995; Seoh et al. 1996; Cha and Bezanilla 1997; Tiwari-Woodruff et al. 1997; Monks et al. 1999). While there is no strong argument to include S1 in the voltage sensor, it is nonetheless present with S2–S4 in all voltage-gated channels and absent from the simple pore channels like KcsA and the inward rectifier K+ channels. It therefore seems reasonable to consider the first four transmembrane segments as collectively forming a domain-like voltage-sensing structure. This view is supported by the general sequence conservation in this region between voltage-gated K+, Ca2+, and Na+ channels. In addition, several “gating modifier” toxins that bind within this region of voltage-gated ion channels tend to interact rather promiscuously with voltage-gated K+, Ca2+, and Na+ channels (Li-Smerin and Swartz 1998; Chuang et al. 1998), suggesting that the voltage-sensing domains adopt well-conserved three-dimensional structures.

What are the secondary and tertiary structures of these four transmembrane segments? The inference from hydrophobicity analysis is that these hydrophobic segments are membrane-spanning α-helices. This, however, remains to be established experimentally. Several studies examining the secondary structure of short peptides corresponding to isolated S2, S3, or S4 segments using circular dichroism, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, or 1H-NMR are consistent with these segments adopting α-helical structures (Mulvey et al. 1989; Peled and Shai 1994; Doak et al. 1996; Peled-Zehavi et al. 1996). Perhaps the strongest case for helical structure can be made for S2, where there is additional evidence from tryptophan-scanning mutagenesis in the Shaker K+ channel (Monks et al. 1999).

In this paper, we explore the secondary structures of the four transmembrane segments in the voltage-sensing domains using alanine-scanning mutagenesis of the region spanning from the NH2-terminal edge of S1 to the COOH-terminal edge of S4 in the drk1 voltage-gated K+ channel (Frech et al. 1989). We examined the mutation-induced perturbation in channel gating for periodicity characteristic of α-helices. Our results support the presence of four transmembrane segments in the region on the NH2-terminal side of the pore domain (S5–S6) and suggest that at least parts of all four segments adopt α-helical structure. We also found evidence for helical secondary structure in the two extracellular linkers between the four transmembrane segments. The distribution of gating perturbations on the four transmembrane segments, together with previously proposed electrostatic interactions, help constrain the packing arrangement within the voltage-sensing domain and suggest which region of the helical bundle may interface with the pore domain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mutagenesis and Channel Expression

Point mutations of drk1 K+ channels were introduced by generating mutant fragments by PCR and ligating into appropriately digested vectors. The construct used contained several previously introduced unique restriction sites (Swartz and MacKinnon 1997b). Mutations were confirmed by dideoxy sequencing (Sanger et al. 1977) or by automated DNA sequencing. cDNAs encoding wild-type and mutant channels were linearized with NotI and transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase. Oocytes were removed surgically from Xenopus laevis frogs and defolliculated by incubating with agitation for 1–1.5 h in a solution containing (mM): 82.5 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 5 HEPES, and 2 mg/ml collagenase (Worthington Biochemical Corp.), adjusted to pH 7.6 with NaOH. Defolliculated oocytes were injected with cRNA and incubated at 17°C in a solution containing (mM): 96 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, 5 HEPES, and 50 μg/ml gentamicin (GIBCO BRL), pH 7.6 with NaOH.

Electrophysiology

Channels were studied using two-electrode voltage clamp recording between 1 and 5 d after cRNA injection using an OC-725C oocyte clamp (Warner Instruments). Oocytes were studied in a 160-μl recording chamber that was perfused with a solution containing (mM): 50 RbCl, 50 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 0.3 CaCl2, and 5 HEPES, pH 7.6 with NaOH. Data were filtered at 2 kHz (eight-pole Bessel) and digitized at 10 kHz. Microelectrode resistances were between 0.2 and 1.2 MΩ when filled with 3 M KCl. All experiments were performed at room temperature (∼22°C).

Voltage–activation relations were obtained by measuring tail current amplitude for various strength depolarizations using 50 mM Rb+ as the charge carrier to slow deactivation. The reversal potential under these ionic conditions was approximately −25 mV. Holding voltages were chosen where no steady state inactivation could be detected, typically −130 to −80 mV. For most channels, inward tail currents were elicited by repolarization to −50 mV and tail current amplitude measured 1–3 ms after repolarization. More negative tail voltages were used for mutants with large negative shifts in the voltage–activation relationship. For mutants with large rightward shifts in the voltage–activation relationship, outward tail currents were elicited by repolarization to voltages between 0 and +30 mV. For a few mutant channels that displayed fast deactivation kinetics, conductance–voltage (G-V) relations were also examined using steady state outward K+ currents and calculating G according to G = I/V − Vrev. In these instances, tail voltage–activation relations and G-V relations were comparable.

Analysis of Channel Gating

To evaluate the gating properties of mutant channels, we considered the channel as existing in two states, closed and open, with a single transition between them. Voltage–activation relations were fit with single Boltzmann functions according to:

|

where I/Imax is the normalized tail current amplitude, z is the equivalent charge, V50 is the half-activation voltage, F is Faraday's constant, R is the gas constant, and T is temperature in Kelvin. Curve fitting was performed using Levenberg-Marquardt minimization procedures (Origin software; MicroCal Software, Inc.). The difference in Gibbs free energy between closed and open states at 0 mV (ΔG 0) was calculated according to: ΔG0 = 0.2389 zFV50.

The change in ΔG 0 caused by each mutation (ΔΔG 0) was then calculated as: ΔΔG 0 = ΔG 0 mut − ΔG 0 wt.

Analysis of Periodicity

Fourier transform methods (Cornette et al. 1987; Komiya et al. 1988; Rees et al. 1989a,Rees et al. 1989b) were used to evaluate the periodicity of ΔΔG 0 for mutations in various regions according to: P(ω) = [X(ω)2 + Y(ω)2],

|

where P(ω) is the Fourier transform power spectrum as a function of angular frequency ω, n is the number of residues of a segment, Vj is |ΔΔG 0| at a given position j and≪V≫is the average value of |ΔΔG 0| for the segment. Corrections of the Fourier transform power spectra, such as smoothing the outliers and ramp correction with least squares, did not significantly change the power spectra. All power spectra are therefore shown without correction.

To quantitatively evaluate the α-helical character from power spectra, the α-periodicity index (α-PI) (Cornette et al. 1987; Komiya et al. 1988) was calculated according to:

|

While an ideal amphipathic helix should give a peak in the power spectrum at ∼100°, transmembrane helices in membrane proteins of known structure tend to show peaks significantly shifted to higher frequencies (Rees et al. 1989b). Our choice of integration window reflects the centering of transmembrane helices at 105° (Komiya et al. 1988; Rees et al. 1989b). α-PI values >2 have been considered indicative of α-helical secondary structure (Cornette et al. 1987; Rees et al. 1989b).

RESULTS

We began by supposing that the four transmembrane segments (S1–S4) of the voltage-sensing domains in voltage-gated K+ channels adopt α-helical structures. In this case, at least some of the helices would be amphipathic, interacting with lipid on one face and protein on another. Since the region in question undergoes a conformational change in response to changes in membrane voltage, a mutation to alanine might be expected to alter the channel's gating properties if it lies at a protein–protein interface, but have little consequence if located at a protein–lipid interface because alanine is hydrophobic. If all residues in a hypothetical amphipathic helix were mutated to alanine (one at a time), then the positions with large effects on gating might cluster on one face and demarcate the protein–protein interface and the positions with only small effects on gating might cluster and identify the protein–lipid interface. The actual situation is likely to be more complicated because there may also be water filled crevices projecting from the internal or external aqueous environments, and therefore a protein–water interface is also possible on the transmembrane surface. Some helices may interact with other helices in the voltage-sensing domain through one face and interact with the helices in the pore domain (S5 and S6) through another face. Thus, there may also be two different types of protein–protein interfaces with mutations in each having different manifestations. We were encouraged, however, by a recent study by Monks et al. 1999, where tryptophan-scanning mutagenesis was applied to the S2 segment of the Shaker K+ channel. They found that residues clustered onto two faces of a helix with high impact residues dominating one face and low impact residues dominating the other. Conceptually, a tryptophan scan and an alanine scan are similar; the difference being that in one case the perturbation is typically the result of adding a bulky residue and the other the result of mutating to the smaller alanine. Both alanine and tryptophan would be expected to interact favorably with membrane lipids. We chose to use an alanine scan with the hope that it would be more gentle than a tryptophan scan and minimize instances where mutations cause channels to fold incompletely or in some way become nonfunctional.

Perturbation in Channel Gating by Mutations in S1 through S4

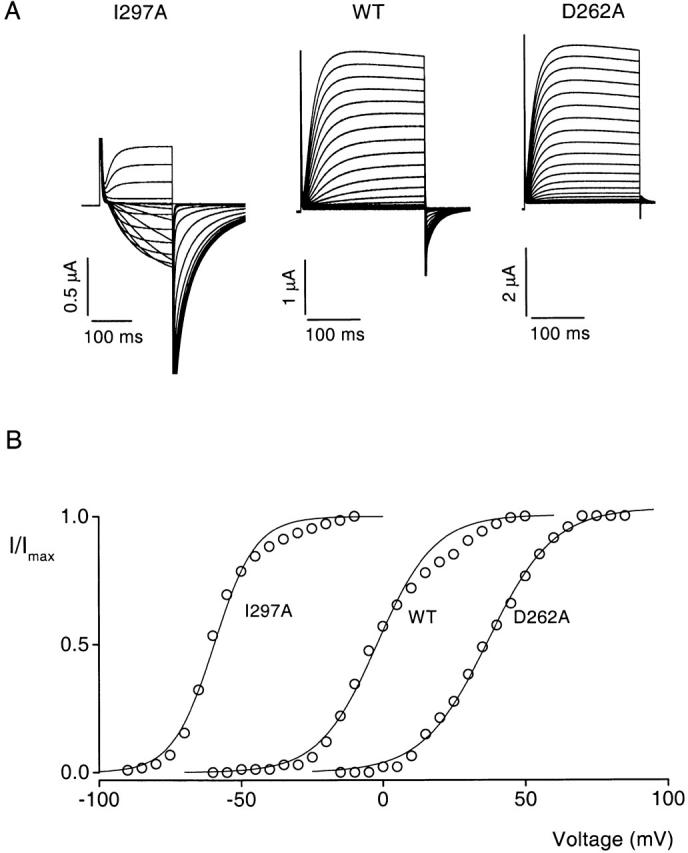

With the above strategy in mind, we alanine scanned the voltage-sensing domain of the drk1 voltage-gated K+ channel (Frech et al. 1989). Each residue was separately mutated to alanine beginning at K185, near the presumed NH2 terminus of S1, and continuing through to T311, near the presumed COOH terminus of S4 (Fig. 1 B). Of the 127 residues mutated, 119 were mutated to alanine, while the 8 native alanine residues were mutated to either valine or tyrosine. Wild-type and mutant channels were expressed in Xenopus oocytes and their gating behavior was assessed using two-electrode voltage-clamp recording techniques. Remarkably, all 127 mutant channels, carrying mutations spanning four putative transmembrane segments and three linkers, could be functionally expressed. Voltage-activation relations were obtained for each mutant channel using tail current protocols (see METHODS). Fig. 2 A shows examples of recording traces for the wild-type and two mutant channels. The families of tail currents show that the opening of these two mutant channels were shifted compared with the wild-type channel—I297A to more negative voltages and D262A to more positive voltages. To obtain a single parameter that reflects the strength of the energetic perturbation produced by each mutation, we first fit single Boltzmann functions to the voltage-activation relations as shown in Fig. 2 B. Based on the parameters derived from the curve fitting (see methods), we calculated the free energy difference between closed and open states at 0 mV (ΔG 0) for each channel, and then calculated the difference in ΔG 0 between wild-type and mutant channels (ΔΔG 0). Table summarizes the gating properties for all 127 mutations.

Figure 2.

Measurement of the effects of mutations on channel gating properties. (A) Current traces obtained from two-electrode voltage-clamp recordings for the wild-type (middle) and two mutant drk1 K+ (I297, left; D262A, right) channels. Current families were elicited by voltage pulses given in 5-mV increments. Tail currents carried by 50 mM Rb+ were elicited by repolarization to appropriate voltages. For I297A, holding voltage was −110 mV, tail voltage was −90 mV, and test pulses start at −90 mV. For the wild-type channel, holding voltage was −80 mV, tail voltage was −50 mV, and test pulses start at −60 mV. For D262A, holding voltage was −80 mV, tail voltage was −10 mV, and test pulses start at −15 mV. (B) Voltage-activation relations for the three channels in A. Symbols are normalized tail current amplitude measured 2–3 ms after repolarization. Solid lines are single Boltzmann fits to the data. The parameters derived from fitting are: V50 = −59.6 mV and z = 3.5 for I297A, V50 = −2.1 mV and z = 2.5 for wild type, and V50 = +36.9 mV and z = 2.2 for D262A.

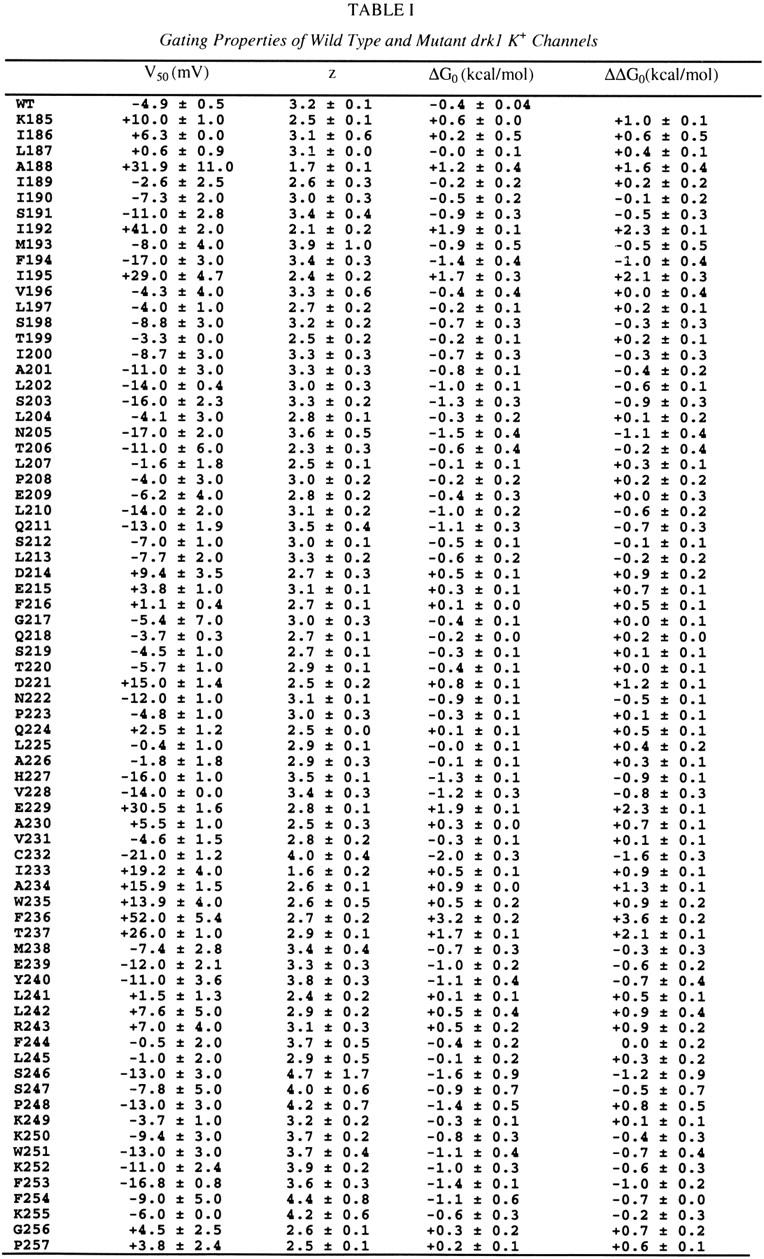

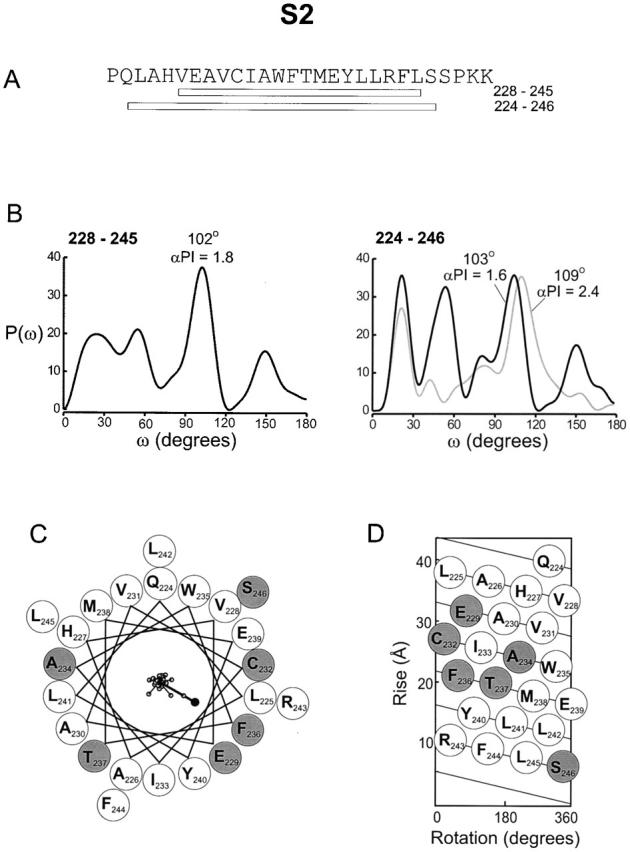

Table 1.

The first column indicates the number and identity of wild-type residues. All non-alanine residues were mutated to alanine. Native alanines were mutated to tyrosine, except fot A307, which was mutated to valine. V50 (the half-activation voltage) and z (the equivalent charge) were derived from fitting single Blotzmann functions to individual tail voltage-activation relations (see MATERIALS AND METHODS and Fig. 2). ΔG 0 (the free energy difference between closed and open states at 0 mV) was calculated as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. ΔΔG 0 is the difference in ΔG 0 between the wild-type and the mutant channel. Data are mean ± SEM for 3-12 voltage-activation relations from three to nine cells for each channel.

|

|---|

|

Distribution of Gating Perturbations

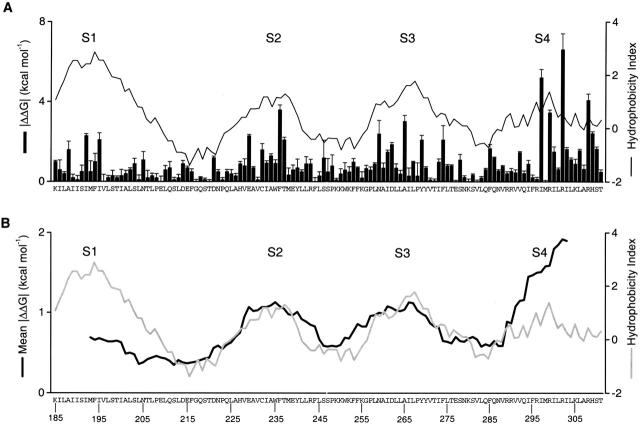

The absolute values of ΔΔG 0 for all the mutant channels are shown in Fig. 3 superimposed with a Kyte-Doolittle hydrophobicity analysis (Kyte and Doolittle 1982) for the region. Residues with large |ΔΔG 0| values tend to cluster into four groups separated by stretches of relatively small |ΔΔG 0| values. The distribution of perturbation energy correlates nicely with the hydrophobicity profile. The energy maxima correspond to the peaks in the hydrophobicity index, while the energy minima correspond to the valleys in the index. Thus, mutations in the linkers between transmembrane segments where the residues tend to be more hydrophilic typically have much smaller effects on gating. The results are quite remarkable and support the notion that four transmembrane segments are present within this region of voltage-gated K+ channels. While the largest perturbations are seen in S4 (up to 6.6 kcal mol−1), there are also sizable changes in ΔΔG 0 for the other three transmembrane segments. It is interesting that there is a trend in the perturbation energies across the region studied with the smallest effects occurring in S1 and the largest effects occurring in S4.

Figure 3.

Distribution of free energy perturbations in channel gating. (A) The bar graph plots the absolute value of ΔΔG 0 for all mutations studied. Data are mean ± SEM from Table . The solid line superimposed on the |ΔΔG 0| plot is a windowed hydrophobicity index calculated using the Kyte-Doolittle scale (Kyte and Doolittle 1982) with a 17-residue window. (B) Sliding window analysis for mean ΔΔG 0 (black line) and hydrophobicity index (gray line). Both use a 17-residue sliding window. Letters and numbers indicate the wild-type residues and their positions, respectively.

Periodicity of Gating Perturbations

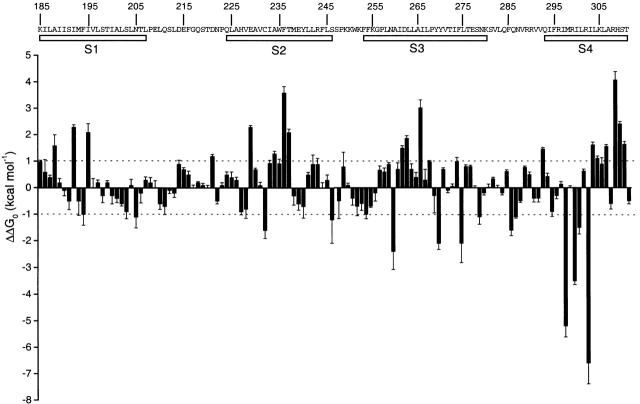

Fig. 4 shows a plot of the actual ΔΔG 0 values for all of the mutations, revealing periodicity in the data. Most notably, positions with negative values of ΔΔG 0, where mutations cause a relative stabilization of the open state, tend to cluster together in patches. Similar clustering is observed for positions with positive values of ΔΔG 0, where mutations produce a relative stabilization of the closed state. For example, mutations in the NH2-terminal half of S4 generally result in large negative values of ΔΔG 0, while mutations in the COOH-terminal half of S4 mostly cause large positive ΔΔG 0 values. There are similar patterns evident in S1, S2, and S3.

Figure 4.

Periodicity in the distribution of free energy perturbations. Plot of actual values of ΔΔG 0 from Table for all positions. Letters and numbers indicate the wild-type residues and their positions, respectively. Dotted lines mark ± 1 kcal mol−1. Open bars mark the approximate limits of the four transmembrane segments defined by hydrophobicity analysis.

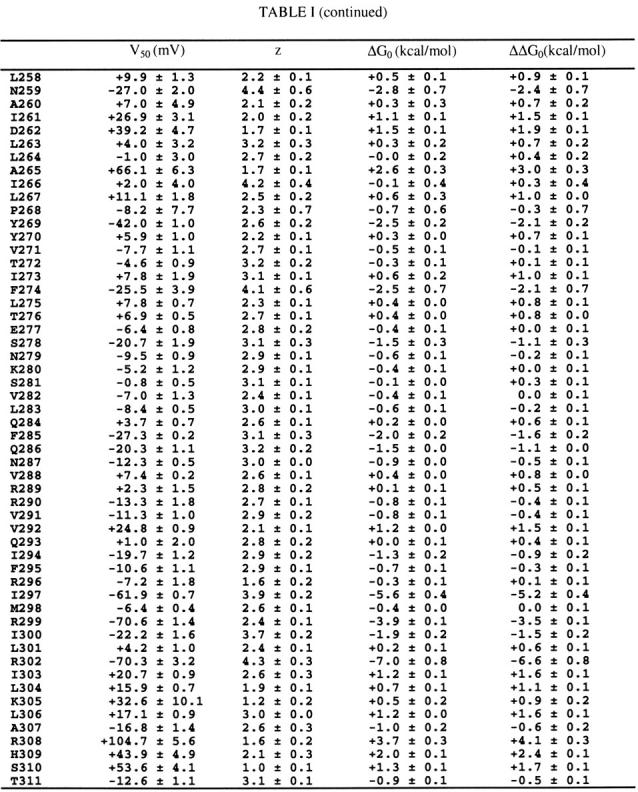

To look more closely for evidence of helical secondary structure, we examined each transmembrane segment individually using Fourier transform methods and helical wheel diagrams. The Fourier transform power spectrum calculated from the |ΔΔG 0| values for the S1 segment is shown in Fig. 5 B. The spectrum is for 23 residues beginning with K185 and ending with L207, just before a highly conserved proline at 208. The strongest peak in the spectrum occurs at 106°, a frequency within the characteristic range for an α-helix. Previous studies suggest that α-PI > 2.0 are a strong indication of α-helical secondary structure (Cornette et al. 1987; Komiya et al. 1988; Rees et al. 1989b) (see METHODS). The α-PI calculated from the spectrum in Fig. 5 B was 2.3. The periodicity within the data for S1 can also be seen in the helical wheel (Fig. 5 C) and net (D) diagrams. Six residues (K185 I192, A188, F194, I195, N205) have |ΔΔG 0| ≥ 1 kcal mol−1 and most are clustered on one side of the wheel. The remaining residues have |ΔΔG 0| < 1 kcal mol−1 and cover a larger fraction of the wheel circumference. Individual |ΔΔG 0| values plotted as vectors on the helical wheel (Fig. 5 C) have a sum of 4.8 kcal mol−1, a value larger than any individual |ΔΔG 0| value. The sum vector therefore points to the side where residues have the largest |ΔΔG 0| values, most likely identifying the face involved in protein–protein interactions. It is notable that this side of the helical wheel contains many of the highly conserved residues observed in sequence comparisons (Fig. 1 B) (Durell et al. 1998; Monks et al. 1999), although it is not a one-to-one correspondence. The residues on the left face of the wheel, where mutations have only minor effects on gating, are all hydrophobic, as if this face of the helix interacts predominantly with lipid. These results suggest that S1 is a membrane spanning α-helix and that it primarily contacts two distinct environments.

Figure 5.

Periodicity of gating perturbations in the S1 segment. (A) Amino acid sequence of the S1 segment in the drk1 K+ channel. The bar indicates the stretch used for Fourier transform analysis. (B) The power spectrum of the |ΔΔG 0| values for this stretch, where P(ω) is plotted as a function of angular frequency (ω). The primary peak of power spectrum occurs at 106°. (C) Helical wheel diagram of these 23 residues viewed from the extracellular side of the membrane. Large shaded circles indicate positions with |ΔΔG 0| ≥ 1 kcal mol−1 and large open circles indicate positions with |ΔΔG 0| < 1.0 kcal mol−1. |ΔΔG 0| values were plotted as vectors on the helical wheel (small open circles); scale is 0–6.9 kcal mol−1. The sum of the |ΔΔG 0| vectors, represented by the solid circle, has a magnitude of 4.8 kcal mol−1. (D) Helical net diagram for 23 residues with top as extracellular and bottom as intracellular. Open and shaded circles are as in C.

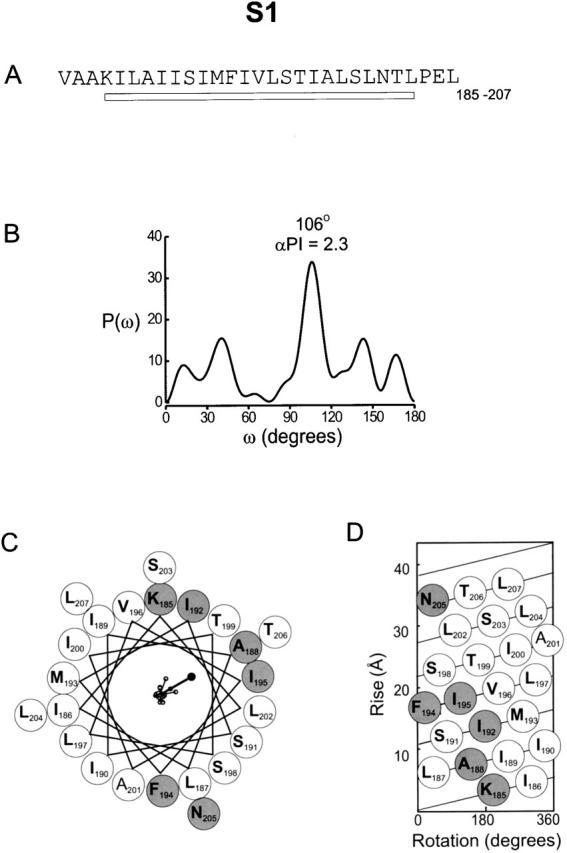

Fig. 6 shows power spectra and both helical wheel and net diagrams using |ΔΔG 0| values in S2. The first power spectrum covers a stretch of 18 residues, from V228 to L245, and ends several residues before a highly conserved proline residue at position 248. As with S1, the spectrum shows a strong peak near the expected frequency for an α-helix, in this case at 102° (Fig. 6 B, left). The α-PI for this spectrum is 1.8. The α-PI for a shorter window in S2 (containing 13 residues) is 2.1 (see Fig. 9). The results from a previous tryptophan scan of S2 in the Shaker K+ channel also showed that residues having large and small effects on channel gating cluster on opposite sides of a helical wheel (Monks et al. 1999). Power spectra of this tryptophan scan (gray line) and our alanine-scan (black line) are shown together in Fig. 6 B for the equivalent 23 residues in the S2 segments of the Shaker and drk1 K+ channels, respectively. The spectrum of the alanine scan of drk1 begins with Q224 and ends with S246, five residues longer than the left spectrum in Fig. 6 B. The superimposed power spectra for the two sets of data are very similar; the typtophan scan of Shaker giving a major peak at 109° (α-PI = 2.4) and the alanine scan of drk1 giving a peak at 103° (α-PI = 1.6). The spectra for S2 in the drk1 K+ channel are somewhat more complex than for S1, with multiple peaks observed at lower frequencies (Fig. 6 B). The helical wheel and net diagrams in Fig. 6C and Fig. D, show the distribution of mutations in S2. Many of the residues with |ΔΔG 0| ≥ 1 kcal mol−1 (shaded circles) overlap those presented by Monks et al. 1999 and mainly lie on one face of the wheel. Individual |ΔΔG 0| values were plotted as vectors on the helical wheel with a sum of 5.3 kcal mol−1, larger than any individual |ΔΔG 0| value. The vector sum points to the side with the largest |ΔΔG 0| values, again most likely identifying the face involved in a protein–protein interface. This side also contains the most highly conserved residues (Fig. 1 B; Durell et al. 1998; Monks et al. 1999), including the acidic residues E229 and E239. Most of the residues where mutations produce only small effects on gating are hydrophobic, representing a putative lipid interface. Taken together, these results suggest that S2 is a membrane spanning α-helix.

Figure 6.

Periodicity of gating perturbations in the S2 Segment. (A) Amino acid sequence of the S2 segment in the drk1 K+ channel with bars indicating the lengths used for the Fourier transform analysis. (B) Power spectra of |ΔΔG 0| values are for either 18 (left) or 23 (right) residues. The primary peak in the power spectra occurs at 102° for the short stretch and at 103° for the long sequence. Gray line in right power spectrum was calculated using data from Monks et al. 1999 for positions in Shaker K+ channel equivalent to 224–246 in the drk1 K+ channel. P(ω) for the Shaker data was scaled down by factor of 8.5 for comparison and has a dominant peak at 109°. (C) Helical wheel diagram containing 23 residues (from Q224 to S246) viewed from the extracellular side of the membrane. Large shaded circles indicate positions with |ΔΔG 0| ≥ 1 kcal mol−1 and large open circles indicate positions with |ΔΔG 0| < 1.0 kcal mol−1. |ΔΔG 0| values were plotted as vectors on the helical wheel (small open circles); scale is 0–6.9 kcal mol−1. The sum of the |ΔΔG 0| vectors, represented by the solid circle, has a magnitude of 5.3 kcal mol−1. (D) Helical net diagram for 23 residues with top as extracellular and bottom as intracellular. Open and shaded circles are as in C.

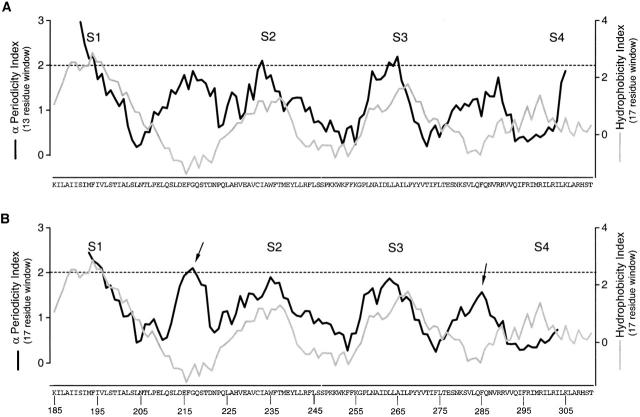

Figure 9.

Windowed α-periodicity analysis for S1–S4. (A) Windowed α-periodicity index analysis with a 13-residue sliding window (black line). (B) Windowed α-periodicity index analysis with a 17-residue sliding window (black line). The superimposed gray line in both A and B is a windowed hydrophobicity index calculated using the Kyte-Doolittle scale (Kyte and Doolittle 1982) with a 17-residue window. Dashed lines in both A and B mark α-PI = 2.0. α-PI ≥ 2.0 suggest α-helical secondary structure (Cornette et al. 1987; Rees et al. 1989b). The arrows mark positions in the S1–S2 and S3–S4 linkers with high α-PI values.

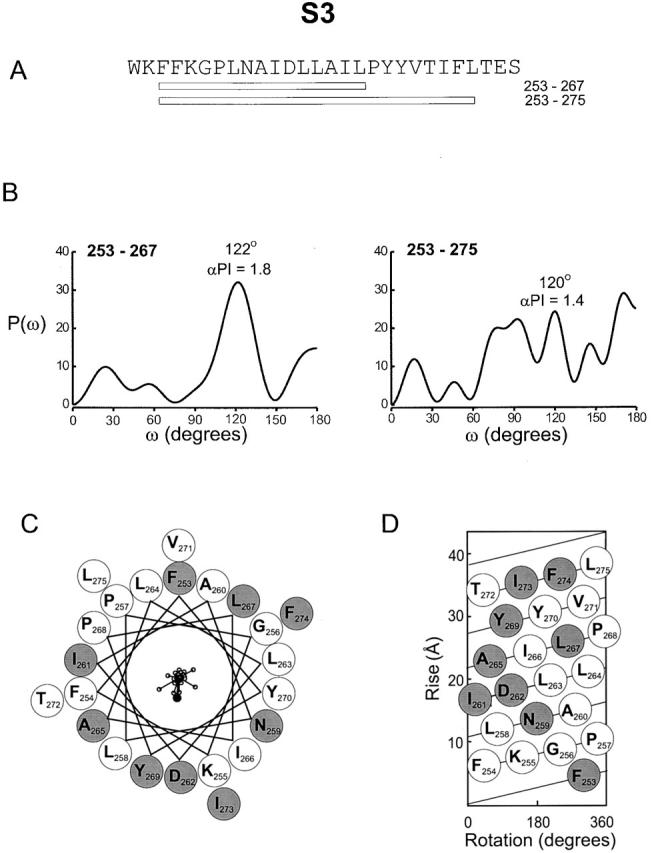

Two power spectra calculated for S3 are shown in Fig. 7 B. As with S1 and S2, a conserved proline residue (P268) is present in S3, but in this case the proline is located at the center of the segment, as collectively defined by the hydrophobicity analysis and the distribution of gating perturbations (Fig. 1 and Fig. 3). We therefore initially examined the power spectrum for only 15 residues beginning with F253A and ending at L267A, just before the conserved proline at 268. This power spectrum shows a major peak at 122°, near the edge of the α-helical frequency, with an α-PI of 1.8. The α-PI for a 13-residue window in this region is 2.2 (see Fig. 9). The spectrum for a COOH-terminally extended segment past the conserved P268 (F253 to L275) is more complex. A peak is still observed within the helix frequency (120°), but it is no longer dominant, and there are many other peaks observed at both lower and higher frequencies. The helical wheel diagram presented in Fig. 7 C shows that the mutations with |ΔΔG 0| ≥ 1 kcal mol−1 (shaded circles) distribute over a large portion of the wheel. However, the net diagram in Fig. 7 D shows a cluster of residues on one face of the helix where mutations have only small effects on gating. The sum of the individual |ΔΔG 0| vectors was 2.6 kcal mol−1, slightly smaller than the largest individual |ΔΔG 0| (3 kcal mol−1 for A265). The sum vector points to the side containing conserved residues (Fig. 1 B; Durell et al. 1998; Monks et al. 1999), including a highly conserved aspartate (D262). While our results for the internal or NH2-terminal two-thirds of S3 are consistent with α-helical structure, they are ambiguous for the COOH-terminal part of S3.

Figure 7.

Periodicity of gating perturbations in the S3 segment. (A) Amino acid sequence of the S3 segment in the drk1 K+ channel with bars indicating the length used for the Fourier transform analysis. (B) Power spectra of |ΔΔG 0| values are for either 15 (left) or 23 (right) residues. The primary peak of power spectrum occurs at 122° for the short stretch. The spectrum for the longer length of sequence contains a peak at 120°, but has greater complexity with many additional peaks. (C) Helical wheel diagram containing 23 residues (from F253 to L275) viewed from the extracellular side of the membrane. Large shaded circles indicate positions with |ΔΔG 0| ≥ 1 kcal mol−1 and large open circles indicate positions with |ΔΔG 0| < 1.0 kcal mol−1. |ΔΔG 0| values were plotted as vectors on the helical wheel (small open circles); scale is 0–6.9 kcal mol−1. The sum of the |ΔΔG 0| vectors, represented by the solid circle, has a magnitude of 2.6 kcal mol−1. (D) Helical net diagram for 23 residues with top as extracellular and bottom as intracellular. Open and shaded circles are as in C.

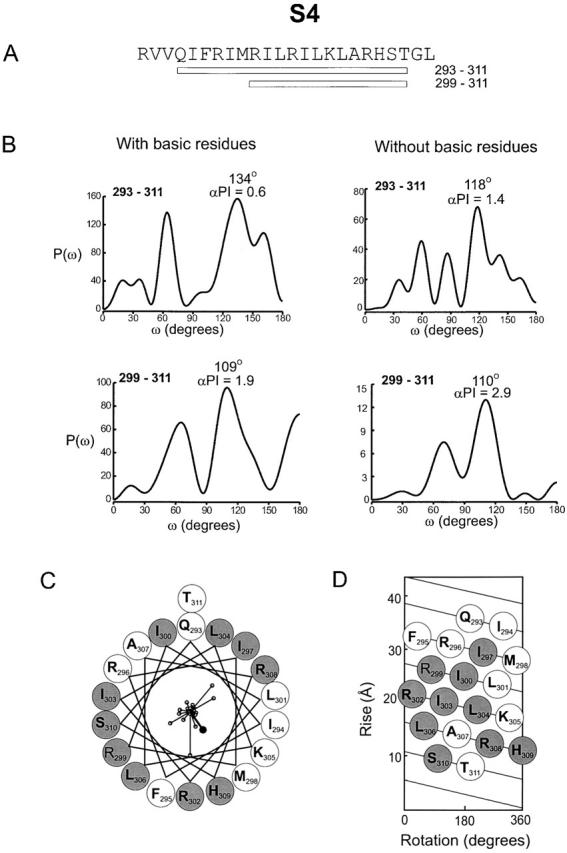

The amino acid sequence of the S4 segment is unique in that it contains a repeating triad of two hydrophobic residues and one basic residue (arginine or lysine). There is strong evidence that the basic residues in S4 move in response to changes in membrane voltage and determine the voltage dependence of the channel (Liman et al. 1991; Papazian et al. 1991, Papazian et al. 1995; Perozo et al. 1994; Planells-Cases et al. 1995; Aggarwal and MacKinnon 1996; Larsson et al. 1996; Mannuzzu et al. 1996; Seoh et al. 1996; Yang et al. 1996; Yusaf et al. 1996; Cha and Bezanilla 1997; Tiwari-Woodruff et al. 1997; Smith-Maxwell et al. 1998a,Smith-Maxwell et al. 1998b; Ledwell and Aldrich 1999; Monks et al. 1999). Thus, mutation of these basic residues may perturb gating by altering protein–protein interactions and/or by changing the voltage dependence of the conformational changes within this region of the protein. Suppose that neutralizing mutations of the arginine and lysine residues in S4 perturbed gating by altering the channel's voltage dependence by reducing the gating charge without any effect on protein–protein interactions. In this case, a periodicity of ∼120° would be observed, regardless of the secondary structure of this region, since the residues in question occur at every third position. However, it is interesting to note that in drk1, two of the seven canonical basic residue positions contain neutral amino acids (Q293 and T311) and mutations at two basic residue positions (R296 and K305) produced only modest perturbations in gating (ΔΔG 0 = +0.1 kcal mol−1 for R296A and ΔΔG 0 = +0.9 kcal mol−1 for K305A). Thus, there are only three positions in the S4 segment of drk1 (R299, R302, and R308) where mutations produce large perturbations that could, either partially or completely, be due to changes in gating charge. To minimize the contribution of changes in voltage dependence to the evaluation of periodicity, we compared spectra containing all |ΔΔG 0| values for a given stretch of residues with those where the |ΔΔG 0| values for the basic S4 residues were set to the mean value of |ΔΔG 0|. This procedure effectively removes these residues from the power spectrum calculation.

Fig. 8 shows four power spectra for the S4 segment. The top left spectrum was calculated using all |ΔΔG 0| values for a stretch of 19 residues beginning at Q293 and ending at T311 (starting from the equivalent of R1 in the Shaker K+ channel and ending with the equivalent of K7). This spectrum is very complex, with the closest peak to the α-helix frequency occurring at 134°. The spectrum for the same stretch after minimizing the contribution of the basic residues is still rather complex, but now the dominant peak occurs at lower frequency (Fig. 8 B, top right). The power spectrum calculated from all |ΔΔG 0| values for the COOH-terminal 13 residues in S4 (R299 to T311) contains a strong peak at 109°, within the frequency range expected for an α-helix, with an α-PI of 1.9 (Fig. 8 B, bottom left). After minimizing the contribution of the basic residues, the spectrum for this region still has a peak in the α-helical frequency range (110°), but now this peak is more dominant, as indicated by the larger α-PI value of 2.9 (Fig. 8 B, bottom right). The similarity of the spectra with and without contributions from the basic residues for the COOH-terminal part of S4 suggests that the observed periodicity reflects an underlying α-helical secondary structure. The helical wheel and net diagrams in Fig. 8C and Fig. D, show that mutations with |ΔΔG 0| ≥ 1 kcal mol−1 (shaded circles) are distributed with little evidence of clustering. Moreover, the sum of the individual |ΔΔG 0| vectors was 3.4 kcal mol−1, significantly smaller than several individual |ΔΔG 0| values. These results suggest that the COOH-terminal part of S4 is α-helical, but say little about the structure of the NH2-terminal part of S4.

Figure 8.

Periodicity of gating perturbations in the S4 segment. (A) Amino acid sequence of the S4 segment in the drk1 K+ channel with bars indicating the length used for the Fourier transform analysis. (B) Power spectra of |ΔΔG 0| values are for either 19 (top) or 13 (bottom) residues. The two left spectra were calculated using all |ΔΔG 0| values for the indicated stretch. The two right spectra were calculated after setting the ΔΔG 0 values for the basic residues to the mean |ΔΔG 0| of all other residues in the indicated stretch. (C) Helical wheel diagram containing 19 residues (from Q293 to T311) viewed from the extracellular side of the membrane. Large shaded circles indicate positions with |ΔΔG 0| ≥ 1 kcal mol−1 and large open circles indicate positions with |ΔΔG 0| < 1.0 kcal mol−1. |ΔΔG 0| values were plotted as vectors on the helical wheel (small open circles); scale is 0–6.9 kcal mol−1. The sum of the |ΔΔG 0| vectors, represented by the solid circle, has a magnitude of 3.4 kcal mol−1. (D) Helical net diagram for 19 residues with top as extracellular and bottom as intracellular. Open and shaded circles are as in C.

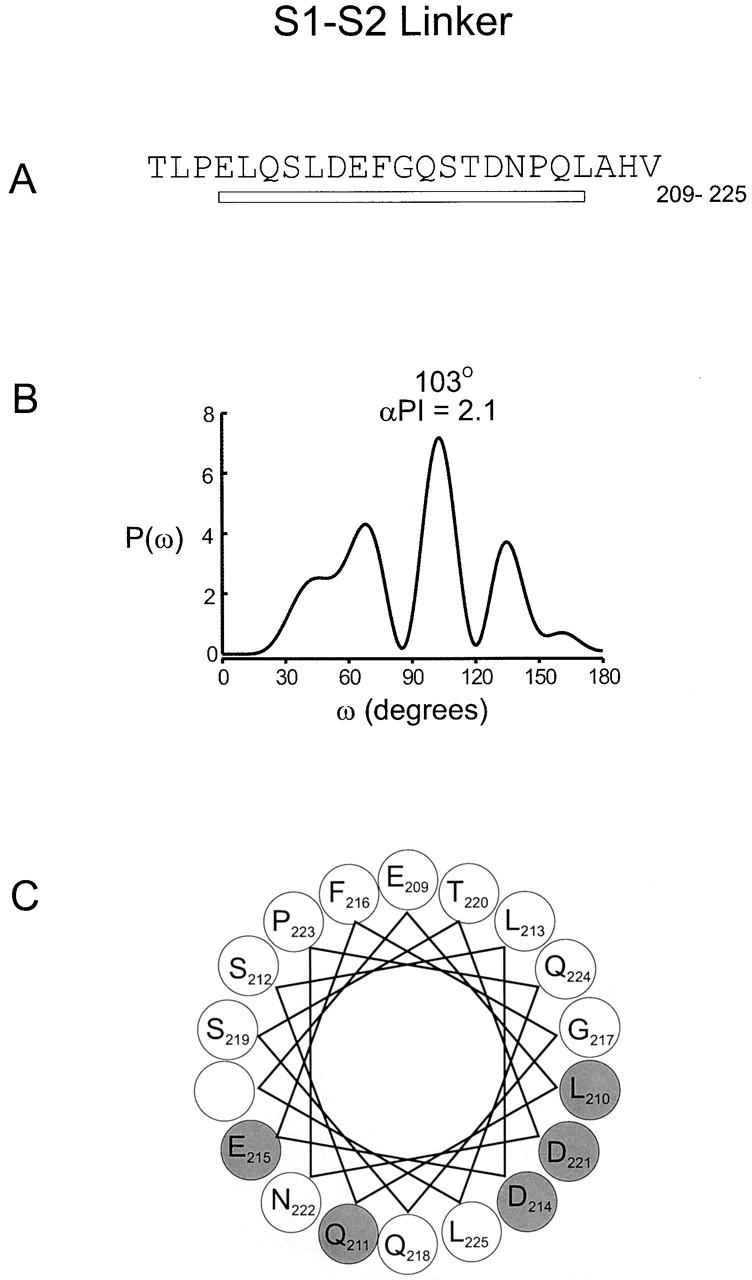

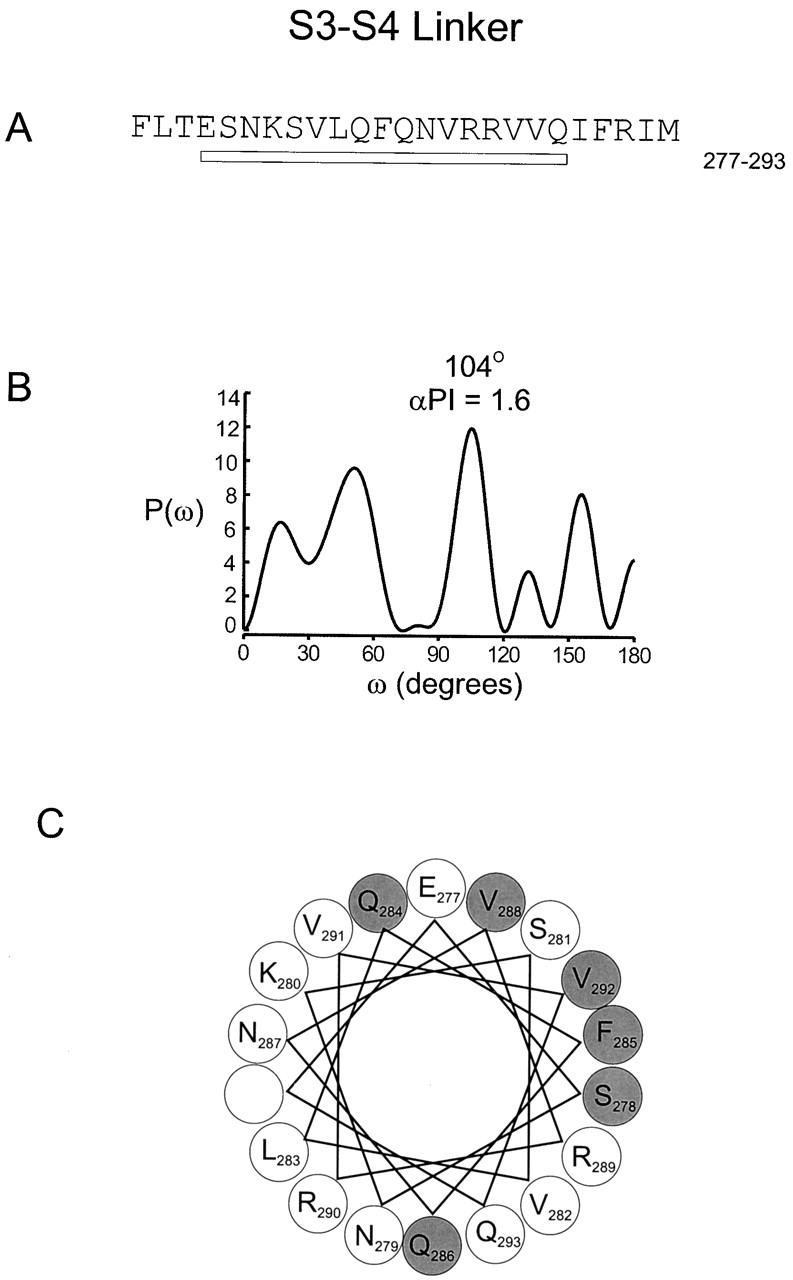

Fig. 9 shows a sliding window analysis of α-PI beginning at the NH2 terminus of S1 and ending at the COOH terminus of S4. A 13-residue window is shown in A and a 17-residue window is shown in B. A sliding window hydrophobicity analysis is also shown for comparison. The comparison between the α-PI and the hydrophobicity index is quite remarkable for two reasons. First, there is an excellent correlation between the α-PI and hydrophobicity index for all four transmembrane segments, especially for S1, S2, and S3. For the 13-residue window, α-PI values greater than 2 are observed for S1, S2, and S3 and a value of 1.9 is seen for S4. This high degree of correspondence between α-PI and hydrophobicity makes it highly probable that all four transmembrane segments are in fact α-helical in structure. A second remarkable aspect of the graph is that within the two extracellular linkers (S1–S2 and S3–S4) there are peaks in the α-PI that correspond to troughs in the hydrophobicity index. For the 17-residue window, peak α-PI values of 2.1 and 1.6 are observed for the S1–S2 and S3–S4 linkers, respectively. In contrast, for the S2–S3 linker, a corresponding minimum is observed for both the α-PI and hydrophobicity index. Fig. 10 and Fig. 11 show power spectra and helical wheel diagrams for the S1–S2 and S3–S4 linkers, respectively. Both spectra show dominant peaks within the α-helical frequency range and both helical wheels show clustering of residues with small versus moderate effects on gating. These results raise the possibility that there is an additional α-helix in each of the two extracellular linkers.

Figure 10.

Periodicity of gating perturbations in the S1–S2 linker. (A) Amino acid sequence of the S1–S2 linker in the drk1 K+ channel. The bar indicates the stretch used for Fourier transform analysis. (B) The power spectrum of the |ΔΔG 0| values for this stretch, where P(ω) is plotted as a function of angular frequency (ω). The primary peak of power spectrum occurs at 103°. (C) Helical wheel diagram of these 17 residues viewed from the NH2 terminus. Large shaded circles indicate positions with |ΔΔG 0| > 0.5 kcal mol−1 and large open circles indicate positions with |ΔΔG 0| ≤ 0.5 kcal mol−1.

Figure 11.

Periodicity of gating perturbations in the S3–S4 linker. (A) Amino acid sequence of the S3–S4 linker in the drk1 K+ channel. The bar indicates the stretch used for Fourier transform analysis. (B) The power spectrum of the |ΔΔG 0| values for this stretch, where P(ω) is plotted as a function of angular frequency (ω). The primary peak of power spectrum occurs at 104°. (C) Helical wheel diagram of these 17 residues viewed from the NH2 terminus. Large shaded circles indicate positions with |ΔΔG 0| > 0.5 kcal mol−1 and large open circles indicate positions with |ΔΔG 0| ≤ 0.5 kcal mol−1.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to probe the secondary structure of the transmembrane segments in the voltage-sensing domain of the drk1 K+ channel using alanine-scanning mutagenesis. The premise of the approach is that rearrangement of the segments in the voltage-sensing domains is important for the conformational changes involved in gating. There is considerable support for this notion for S2, S3, and S4 from mutagenesis (Liman et al. 1991; Papazian et al. 1991, Papazian et al. 1995; Perozo et al. 1994; Planells-Cases et al. 1995; Aggarwal and MacKinnon 1996; Seoh et al. 1996; Tiwari-Woodruff et al. 1997; Smith-Maxwell et al. 1998a,Smith-Maxwell et al. 1998b; Ledwell and Aldrich 1999; Monks et al. 1999) and various labeling techniques (Larsson et al. 1996; Mannuzzu et al. 1996; Yang et al. 1996; Yusaf et al. 1996; Cha and Bezanilla 1997). Thus, we would expect that the energetics of gating would be perturbed by mutations of residues involved in protein–protein interactions but would be much less affected by mutations of residues interacting with either lipid or water. Our measurements do not elucidate the mechanism by which these mutations perturb the energetics of channel gating. The approach was to look for patterns that might be revealed by simply quantifying the perturbation in gating energetics (ΔΔG 0) produced by the mutations. The first observation was that the pattern of perturbations in gating energy nicely paralleled both the hydrophobicity index and the degree of conservation (Fig. 1 and Fig. 3), supporting the notion that there are four transmembrane segments present on the NH2 terminal side of the pore domain. Closer examination of the periodicity in the energetic perturbations within individual transmembrane segments suggests that at least portions of all four segments (S1–S4) adopt α-helical structures. In addition, we found evidence for α-helical structure in the two extracellular linkers. We will discuss each of these regions in detail, pointing out a number of interesting features for each.

The mutations in S1 had the smallest effects on ΔG 0 compared with the other three transmembrane segments with the largest change of +2.3 kcal mol−1 occurring for I192A. Nevertheless, the periodicity in the data for S1 was clear from both the Fourier transform power spectrum and helical wheel diagrams (Fig. 5). A clean peak in the power spectrum occurred at 106°, a frequency corresponding to an α-helix, with an α-PI of 2.3. The sum of the individual |ΔΔG 0| vectors (4.8 kcal mol−1) was much larger than any individual |ΔΔG 0| vector and pointed to the face containing the majority of residues having large effects. This suggests that S1 is an α-helix with two main faces interacting with different environments. The face identified by the vector sum likely represents a protein–protein interface. The opposite face contains 10 residues with only minor effects on gating and these residues are all hydrophobic, suggesting that they likely interact with lipid. The highly conserved proline (P208) at the COOH-terminal border of S1 may serve as a helix breaker and thus demarcate the end of the S1 helix. If the NH2 terminus of the S1 helix begins at K185, where our analysis starts, the helix would contain 23 residues and have sufficient length to cross the hydrophobic core of the lipid membrane (∼35 Å). Since the hydrophobicity index is still rather large at K185, it is possible that the S1 helix may begin several residues before K185.

Our results for the S2 segment also support a helical structure, consistent with previous results in the Shaker K+ channel (Monks et al. 1999). The power spectra gave major peaks at either 102° or 103°, depending on the length of the stretch analyzed. Although the two spectra shown in Fig. 6 have α-PI values of 1.8 and 1.6, the sliding 13-residue window analysis gave an α-PI of 2.1. Multiple lower frequency peaks, especially in the stretch containing 23 residues, imply that the S2 segment may have a somewhat more complex environment than S1. As with S1, the sum of the individual |ΔΔG 0| vectors was larger (5.3 kcal mol−1) than any individual |ΔΔG 0| vector, pointing to the face containing the majority of positions where mutants have large effects. These results suggest that S2 is an α-helix with the large vector sum identifying the protein–protein interface. This face contains two acidic residues (E229 and E239) that are equivalent to residues in the Shaker K+ channel (E283 and E293) thought to form electrostatic interactions with basic residues in S4 (Papazian et al. 1995; Planells-Cases et al. 1995; Tiwari-Woodruff et al. 1997). It is interesting that mutation of E229, but not E239, had a significant effect on gating. Perhaps the strength of these electrostatic interactions differs between the drk1 and Shaker K+ channels. Most of the positions where mutations have only minor effects on gating contain hydrophobic residues, suggesting that they might interact with lipid. The two exceptions, Q224 and H227, are near the beginning of the helix, where they might interact with water filling a crevice. As with S1, a highly conserved proline (P248) at the COOH-terminal border of S2 may serve as a helix breaker and thereby mark the end of the S2 helix. If the S2 helix begins near Q224, it would have sufficient length (23 residues) to cross the hydrophobic core of the lipid membrane.

It is remarkable that our results for an alanine scan of S2 in the drk1 K+ channel are so similar to those for a tryptophan scan of S2 in the Shaker K+ channel (Monks et al. 1999). While the two related channels are similar in many ways, the actual mutations made in the two studies are very different. In the tryptophan scan the mutation generally introduces a much larger residue, while in the alanine scan the mutation generally introduces a smaller one. However, comparison of the power spectra for the two types of scans shows that both spectra have similar dominant peaks at the proper frequency for an α-helix, and in addition contain several coincident minor peaks. The similarity in the results with the two scans strongly supports the premise that the large perturbations occur at protein–protein interfaces and that the weak perturbations occur at protein–lipid or protein–water interfaces. For positions where the native residues are hydrophobic, and equally tolerant of alanine or tryptophan, it seems likely that the solvent is lipid.

Our results for S3, together with the hydrophobicity and sequence analysis, suggest that either the structure of this region or its environment is considerably more complex than seen for S1 and S2. We first considered only the results obtained with the first 15 residues in S3 because there is a very highly conserved proline residue (P268) only 15 residues in from the likely start of the S3 segment. P268 corresponds, not to minima in the |ΔΔG 0| or hydrophobicity index patterns, but to maxima in both. The power spectrum for this stretch of 15 residues contains a large peak at 122°, near the α-helix frequency range, but pushing the high frequency end of that range. The calculated α-PI for the spectrum shown in Fig. 7 is 1.8, but values as high as 2.2 are observed in the sliding 13-residue window analysis (Fig. 9). The unusually high frequency of 120° would be consistent with the NH2-terminal part of S3, adopting an α-helical structure that is more tightly coiled than a typical helix, possibly indicating that S3 is a 310 helix. This seems unlikely since a 310 helix of this length would be highly unusual, if not unprecedented. Alternately, this may simply reflect that the environment of the helix is rather complex, possibly suggesting that S3 has protein–protein contacts on multiple faces. In this regard, it is interesting that residues having large effects on gating are rather distributed on a helical wheel. This is manifest in a rather weak vector sum for |ΔΔG 0| (2.6 kcal mol−1), a value actually less than any individual |ΔΔG 0| value. In any case, a helix containing 15 residues cannot span the width of the membrane and the minima in both the |ΔΔG 0| and hydrophobicity index patterns occur some distance past P268 towards the COOH terminus. However, the power spectrum for a COOH-terminally extended region past P268 and containing 23 residues was very complex. Many more peaks are now observed with the 120° peak being of equal or smaller size than many other peaks in the spectrum. One possibility is that the entire S3 segment is α-helical, but there is a break or kink at P268 that results in a phase shift between the NH2- and COOH-terminal portions of the segment. Alternatively, it may simply be that the environments surrounding the NH2- and COOH-terminal portions of the S3 helix are very different. In this regard, it is interesting to note that before P268 there is a cluster of mutations that give positive ΔΔG 0 values. On the COOH-terminal side of P268, several mutants significantly perturb channel gating, but with no clustering with respect to relative stabilization of closed or open states. It is important to stress that our results are equally compatible with the COOH-terminal region of S3 adopting a completely different secondary structure (i.e., nonhelical).

Another interesting aspect of the COOH-terminal part of S3 is that it seems to form the binding site for hanatoxin, a gating modifier of the drk1 K+ channel. Three residues (I273, F274, and E277) located on the COOH-terminal side of P268 are particularly important for interaction with hanatoxin (Swartz and MacKinnon 1997a,Swartz and MacKinnon 1997b; Li-Smerin and Swartz 1999). Moreover, hanatoxin interacts rather promiscuously with different voltage-gated ion channels (Li-Smerin and Swartz 1998), suggesting that this region adopts a similar structure in different voltage-gated ion channels. This is despite the fact that the degree of sequence conservation in the COOH-terminal part of S3 is much less than in the NH2-terminal part of S3.

The power spectrum for the COOH-terminal 13 residues of the S4 segment contains a peak at 109°, suggesting α-helical structure. This result does not appear to be dominated by the repeating pattern of basic residues because minimizing the contribution of these residues in the analysis does not alter the position of the main peak at the α-helical frequency (see RESULTS). In fact, removing the basic residues from the Fourier transform analysis greatly improves the α-PI (from 1.9 to 2.9). The spectrum for a longer stretch (containing 19 residues) was much more complex, with no dominant peaks at frequencies indicative of an α-helix. These results suggest that the COOH-terminal portion of S4 is α-helical, but are ambiguous when it comes to the NH2-terminal part. However, the repeating triad of two hydrophobic residues and a basic residue extends through the entire S4 segment, suggesting a similar secondary structure throughout. Perhaps the simplest explanation is that the environments of both the NH2- and COOH-terminal parts of the S4 helix are rather different, possibly involving different combinations of protein–protein, protein–water, and even small protein–lipid interfaces. The observation that mutations producing the largest effects on gating are more or less evenly distributed around the helical wheel suggests that protein–protein interfaces may dominate most of the transmembrane surface of S4. In addition, we find that mutations in the NH2-terminal part of S4 produce negative values of ΔΔG 0, whereas mutations in the COOH-terminal part produce positive values of ΔΔG 0. This suggests that the NH2- and COOH-terminal portions of S4 may play different roles in the voltage-gating process such that mutations in the NH2-terminal part cause a relative stabilization of the open state and mutations in the COOH-terminal part cause a relative stabilization of the closed state. Perhaps the two parts of S4 interact with distinct structural elements of the protein.

One of the most unanticipated results of the present study was that the analysis of both the S1–S2 and S3–S4 linkers shows evidence of helical secondary structure. This was first apparent from the sliding window analysis where peaks in the α-PI are observed at minima in the hydrophobicity analysis (Fig. 9). The helical character of these linkers is also evident in both the power spectra and helical wheel diagrams (Fig. 10 and Fig. 11). If the extracellular linker between S1 and S2 is an α-helix, then it most likely rests on the surface of the protein for two reasons (Fig. 12A and Fig. B). First, we observed strong helical character for long enough stretches (23 residues) in both S1 and S2 to completely span the hydrophobic core of the membrane. Second, in contrast to most of the membrane-spanning helices, the entire circumference of the S1–S2 linker helix contains many hydrophilic residues. Thus, for the S1–S2 linker helix, the likely interfaces are protein–protein and protein–water, with no significant protein–lipid interfaces. The conceptual frame of reference for the S3–S4 linker is less clear because of the uncertainties with the secondary structure of the COOH-terminal part of S3. The S3–S4 linker helix may lie on the surface, as we postulate for the S1–S2 linker. Alternately, this helix may begin soon after the conserved proline (268) in S3 and thus represent an extension of S3 and possibly lie partially within the membrane (Fig. 12A and Fig. B).

Figure 12.

Secondary structure and packing orientation of S1 to S4. (A) Membrane-folding model for a voltage-gated K+ channel showing four membrane spanning α-helices (black cylinders) and two possible α-helices (gray cylinders) in the extracellular linkers. The black and gray helices comprise the voltage-sensing domains, while the blue region (S5 through S6) forms the pore domain. (B) Possible arrangement of transmembrane helices in the tetrameric voltage-gated K+ channel shown schematically. Gray helices in the S1–S2 and S3–S4 linkers are shown lying on the surface of the four transmembrane helices of the voltage-sensing domain. (C) Helical wheel diagrams for S1–S4 arranged to allow for appropriate protein–lipid and protein–protein interfaces and to account for previously proposed electrostatic interactions (marked by red dotted line). Electrostatic interactions are for E239 in S2 and D262 in S3 with K305 in S4 and for E229 in S2 with R302 and R299 in S4 (see discussion). The helical wheel diagrams (same as used in Fig. 5 Fig. 6 Fig. 7 Fig. 8) are shown as viewed from the extracellular side of the channel. Vector sums all point towards the interior of the complex, although this was not a constraint used in making the arrangement. (D) S1 to S4 segments presented as a bundle of four helices viewed from the extracellular side with the approximate position of the interface with pore domain indicated. Each helix is tilted relative to the membrane plane and to each other to maximize the presence of residues with ΔΔG < 1 kcal mol−1 on the surface and minimize the presence of residues with ΔΔG ≥ 1 kcal mol−1 on the surface. The relative position of each segment is the same as in C.

The present results are consistent with S1 to S4 each adopting α-helical secondary structures, albeit with the above-noted complexities. What is the tertiary structure of the four transmembrane helices, and where do they interface with the pore domain? Our helical wheel diagrams and vector plots identify the most likely faces where protein–protein interactions take place and where protein–solvent interfaces form. Several previously proposed electrostatic interactions add additional constraints (Papazian et al. 1995; Planells-Cases et al. 1995; Tiwari-Woodruff et al. 1997). Three acidic residues in the S2 and S3 segments of the Shaker K+ channel have been proposed to interact with basic residues in S4. For the Shaker K+ channel, E283 in S2 is thought to interact with R368 and R371 in S4, while E293 in S2 and D316 in S3 interact with K374 in S4. The equivalent electrostatic network in the drk1 K+ channel would suggest that E229 in S2 interacts with R299 and R302 in S4, while E239 in S2 and D362 in S3 interact with K305 in S4. Positioning of the helical wheels to accommodate the electrostatic interactions and place the protein–lipid and protein–protein interfaces appropriately gives a possible arrangement of the four helices in the helical bundle (Fig. 12C and Fig. D). The angles of the four helices with respect to each other and the membrane were then approximated by maximizing the presence of residues with small effects on gating on the transmembrane surface (Fig. 12 D). The relative location of S1 is the most arbitrary because the only constraint for this helix is that a large fraction of its circumference likely interacts with lipid. While this arrangement is speculative, it illustrates several important points. It seems likely that S1 and S2, the most amphipathic of the helices with probable lipid-exposed faces, are positioned in the periphery away from the interface with the pore domain. In contrast, for both S3 and S4, mutations causing large effects on gating tend to be regularly distributed around the helices. This suggests that S3 and S4 are the most buried of the helices, making them good candidates to interface directly with structural elements in the pore domain.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rod MacKinnon for helpful discussions, Rosalind Chuang for making some of the mutants, and J. Nagle and D. Kauffman in the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Sequencing Facility for DNA sequencing. We thank Chris Miller and Kwang Hee Hong for sharing unpublished tryptophan-scanning results in the Shaker K+ channel.

D.H. Hackos was supported by the PRAT program, National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Abbreviation used in this paper: α-PI, α-periodicity index.

References

- Aggarwal S.K., MacKinnon R. Contribution of the S4 segment to gating charge in the Shaker K+ channel. Neuron. 1996;16:1169–1177. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong C.M., Hille B. Voltage-gated ion channels and electrical excitability. Neuron. 1998;20:371–380. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80981-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler A., Wei A.G., Baker K., Salkoff L. A family of putative potassium channel genes in Drosophila. Science. 1989;243:943–947. doi: 10.1126/science.2493160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha A., Bezanilla F. Characterizing voltage-dependent conformational changes in the Shaker K+ channel with fluorescence. Neuron. 1997;19:1127–1140. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80403-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang R.S., Jaffe H., Cribbs L., Perez-Reyes E., Swartz K.J. Inhibition of T-type voltage-gated calcium channels by a new scorpion toxin. Nat. Neurosci. 1998;1:668–674. doi: 10.1038/3669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornette J.L., Cease K.B., Margalit H., Spouge J.L., Berzofsky J.A., DeLisi C. Hydrophobicity scales and computational techniques for detecting amphipathic structures in proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1987;195:659–685. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90189-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doak D.G., Mulvey D., Kawaguchi K., Villalain J., Campbell I.D. Structural studies of synthetic peptides dissected from the voltage-gated sodium channel. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;258:672–687. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle D.A., Cabral J.M., Pfuetzner R.A., Kuo A., Gulbis J.M., Cohen S.L., Chait B.T., MacKinnon R. The structure of the potassium channelmolecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science. 1998;280:69–77. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durell S.R., Hao Y., Guy H.R. Structural models of the transmembrane region of voltage-gated and other K+ channels in open, closed, and inactivated conformations. J. Struct. Biol. 1998;121:263–284. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1998.3962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frech G.C., VanDongen A.M., Schuster G., Brown A.M., Joho R.H. A novel potassium channel with delayed rectifier properties isolated from rat brain by expression cloning. Nature. 1989;340:642–645. doi: 10.1038/340642a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann H.A., Kirsch G.E., Drewe J.A., Taglialatela M., Joho R.H., Brown A.M. Exchange of conduction pathways between two related K+ channels. Science. 1991;251:942–944. doi: 10.1126/science.2000495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heginbotham L., Lu Z., Abramson T., MacKinnon R. Mutations in the K+ channel signature sequence. Biophys. J. 1994;66:1061–1067. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80887-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren M., Jurman M.E., Yellen G. N-type inactivation and the S4–S5 region of the Shaker K+ channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 1996;108:195–206. doi: 10.1085/jgp.108.3.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi T., Zagotta W.N., Aldrich R.W. Biophysical and molecular mechanisms of Shaker potassium channel inactivation. Science. 1990;250:533–538. doi: 10.1126/science.2122519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komiya H., Yeates T.O., Rees D.C., Allen J.P., Feher G. Structure of the reaction center from Rhodobacter sphaeroides R-26 and 2.4.1symmetry relations and sequence comparisons between different species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:9012–9016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.23.9012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyte J., Doolittle R.F. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J. Mol. Biol. 1982;157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson H.P., Baker O.S., Dhillon D.S., Isacoff E.Y. Transmembrane movement of the Shaker K+ channel S4. Neuron. 1996;16:387–397. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledwell J.L., Aldrich R.W. Mutations in the S4 region isolate the final voltage-dependent cooperative step in potassium channel activation. J. Gen. Physiol. 1999;113:389–414. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.3.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liman E.R., Hess P., Weaver F., Koren G. Voltage-sensing residues in the S4 region of a mammalian K+ channel. Nature. 1991;353:752–756. doi: 10.1038/353752a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liman E.R., Tytgat J., Hess P. Subunit stoichiometry of a mammalian K+ channel determined by construction of multimeric cDNAs. Neuron. 1992;9:861–871. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90239-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li-Smerin Y., Swartz K.J. Gating modifier toxins reveal a conserved structural motif in voltage-gated Ca2+ and K+ channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:8585–8589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li-Smerin Y., Swartz K.J. Structural determinants of the hanatoxin receptors on the drk1 voltage-gated K+ channel Biophys. J. 76 1999. A328(Abstr.) [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon R. Determination of the subunit stoichiometry of a voltage-activated potassium channel. Nature. 1991;350:232–235. doi: 10.1038/350232a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon R., Cohen S.L., Kuo A., Lee A., Chait B.T. Structural conservation in prokaryotic and eukaryotic potassium channels. Science. 1998;280:106–109. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon R., Miller C. Mutant potassium channels with altered binding of charybdotoxin, a pore-blocking peptide inhibitor. Science. 1989;245:1382–1385. doi: 10.1126/science.2476850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon R., Yellen G. Mutations affecting TEA blockade and ion permeation in voltage-activated K+ channels. Science. 1990;250:276–279. doi: 10.1126/science.2218530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannuzzu L.M., Moronne M.M., Isacoff E.Y. Direct physical measure of conformational rearrangement underlying potassium channel gating. Science. 1996;271:213–216. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5246.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monks S.A., Needleman D.J., Miller C. Helical structure and packing orientation of the S2 segment in the Shaker K+ channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 1999;113:415–423. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.3.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey D., King G.F., Cooke R.M., Doak D.G., Harvey T.S., Campbell I.D. High resolution 1H NMR study of the solution structure of the S4 segment of the sodium channel protein. FEBS Lett. 1989;257:113–117. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81799-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papazian D.M., Shao X.M., Seoh S.A., Mock A.F., Huang Y., Wainstock D.H. Electrostatic interactions of S4 voltage sensor in Shaker K+ channel. Neuron. 1995;14:1293–1301. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90276-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papazian D.M., Timpe L.C., Jan Y.N., Jan L.Y. Alteration of voltage-dependence of Shaker potassium channel by mutations in the S4 sequence. Nature. 1991;349:305–310. doi: 10.1038/349305a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peled H., Shai Y. Synthetic S-2 and H-5 segments of the Shaker K+ channelsecondary structure, membrane interaction, and assembly within phospholipid membranes. Biochemistry. 1994;33:7211–7219. doi: 10.1021/bi00189a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peled-Zehavi H., Arkin I.T., Engelman D.M., Shai Y. Coassembly of synthetic segments of Shaker K+ channel within phospholipid membranes. Biochemistry. 1996;35:6828–6838. doi: 10.1021/bi952988t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perozo E., Santacruz-Toloza L., Stefani E., Bezanilla F., Papazian D.M. S4 mutations alter gating currents of Shaker K channels. Biophys. J. 1994;66:345–354. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(94)80783-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planells-Cases R., Ferrer-Montiel A.V., Patten C.D., Montal M. Mutation of conserved negatively charged residues in the S2 and S3 transmembrane segments of a mammalian K+ channel selectively modulates channel gating. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:9422–9426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan R., Lewis J.H., MacKinnon R. Spatial localization of the K+ channel selectivity filter by mutant cycle-based structure analysis. Neuron. 1996;16:131–139. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees D.C., DeAntonio L., Eisenberg D. Hydrophobic organization of membrane proteins Science. 245 1989. 510 513a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees D.C., Komiya H., Yeates T.O., Allen J.P., Feher G. The bacterial photosynthetic reaction center as a model for membrane proteins Annu. Rev. Biochem. 58 1989. 607 633b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger F., Nicklen S., Coulson A.R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santacruz-Toloza L., Huang Y., John S.A., Papazian D.M. Glycosylation of Shaker potassium channel protein in insect cell culture and in Xenopus oocytes. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5607–5613. doi: 10.1021/bi00184a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrempf H., Schmidt O., Kummerlen R., Hinnah S., Muller D., Betzler M., Steinkamp T., Wagner R. A prokaryotic potassium ion channel with two predicted transmembrane segments from Streptomyces lividans . EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1995;14:5170–5188. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00201.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz T.L., Tempel B.L., Papazian D.M., Jan Y.N., Jan L.Y. Multiple potassium-channel components are produced by alternative splicing at the Shaker locus in Drosophila. Nature. 1988;331:137–142. doi: 10.1038/331137a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seoh S.A., Sigg D., Papazian D.M., Bezanilla F. Voltage-sensing residues in the S2 and S4 segments of the Shaker K+ channel. Neuron. 1996;16:1159–1167. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Maxwell C.J., Ledwell J.L., Aldrich R.W. Role of the S4 in cooperativity of voltage-dependent potassium channel activation J. Gen. Physiol. 111 1998. 399 420a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Maxwell C.J., Ledwell J.L., Aldrich R.W. Uncharged S4 residues and cooperativity in voltage-dependent potassium channel activation J. Gen. Physiol. 111 1998. 421 439b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stühmer W., Ruppersberg J.P., Schroter K.H., Sakmann B., Stocker M., Giese K.P., Perschke A., Baumann A., Pongs O. Molecular basis of functional diversity of voltage-gated potassium channels in mammalian brain. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1989;8:3235–3244. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08483.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz K.J., MacKinnon R. Hanatoxin modifies the gating of a voltage-dependent K+ channel through multiple binding sites Neuron. 18 1997. 665 673a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz K.J., MacKinnon R. Mapping the receptor site for hanatoxin, a gating modifier of voltage-dependent K+ channels Neuron. 18 1997. 675 682b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari-Woodruff S.K., Schulteis C.T., Mock A.F., Papazian D.M. Electrostatic interactions between transmembrane segments mediate folding of Shaker K+ channel subunits. Biophys. J. 1997;72:1489–1500. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78797-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang N., George A.L., Jr., Horn R. Molecular basis of charge movement in voltage-gated sodium channels. Neuron. 1996;16:113–122. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yellen G., Jurman M.E., Abramson T., MacKinnon R. Mutations affecting internal TEA blockade identify the probable pore-forming region of a K+ channel. Science. 1991;251:939–942. doi: 10.1126/science.2000494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yool A.J., Schwarz T.L. Alteration of ionic selectivity of a K+ channel by mutation of the H5 region. Nature. 1991;349:700–704. doi: 10.1038/349700a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusaf S.P., Wray D., Sivaprasadarao A. Measurement of the movement of the S4 segment during the activation of a voltage-gated potassium channel. Pflügers Arch. 1996;433:91–97. doi: 10.1007/s004240050253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagotta W.N., Hoshi T., Aldrich R.W. Restoration of inactivation in mutants of Shaker potassium channels by a peptide derived from ShB. Science. 1990;250:568–571. doi: 10.1126/science.2122520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]