Abstract

Hox proteins have been proposed to act at multiple levels within regulatory hierarchies and to directly control the expression of a plethora of target genes. However, for any specific Hox protein or tissue, very few direct in vivo-regulated target genes have been identified. Here, we have identified target genes of the Hox protein Ultrabithorax (UBX), which modifies the genetic regulatory network of the wing to generate the haltere, a modified hindwing. We used whole-genome microarrays and custom arrays including all predicted transcription factors and signaling molecules in the D. melanogaster genome to identify differentially expressed genes in wing and haltere imaginal discs. To elucidate the regulation of selected genes in more detail, we isolated cis-regulatory elements (CREs) for genes that were specifically expressed in either the wing disc or haltere disc. We demonstrate that UBX binds directly to sites in one element, and these sites are critical for activation in the haltere disc. These results indicate that haltere and metathoracic segment morphology is not achieved merely by turning off the wing and mesothoracic development programs, but rather specific genes must also be activated to form these structures. The evolution of haltere morphology involved changes in UBX-regulated target genes, both positive and negative, throughout the wing genetic regulatory network.

Keywords: Hox protein, Ultrabithorax, Drosophila, wing, haltere, anachronism

INTRODUCTION

In segmented animals, including arthropods and chordates, serially homologous structures, such as appendages and vertebrae, are reiterated along the anterior-posterior axis. A major aspect of evolutionary diversification within these groups involves morphological differentiation of these serial homologs. For instance, specialized feeding limbs in crustaceans, different forewing and hindwing shapes in insects, and differences in the axial skeleton in vertebrates are all examples of the diversification of serial homologs. Understanding the mechanisms that generate this diversity is an important goal in both developmental and evolutionary biology.

The central role of the Hox genes in the development of serial homologs was initially recognized through perturbations that resulted in the transformation of one segment identity into that of another segment (Lewis, 1978). Shared among all bilaterian animals, the Hox genes are expressed in and regulate the fate of specific domains along the anterior-posterior axis during development. Changes in the regulation of Hox genes themselves and of the target genes they control are important in the development and evolution of serial homologs (Averof and Patel, 1997; Burke et al., 1995; Cohn and Tickle, 1999; Lohmann et al., 2002; Mahfooz et al., 2004; Pearson et al., 2005; Stern, 1998).

Within the insects, the Hox gene Ultrabithorax (Ubx) specifies identity in the third thoracic segment. Ubx activity is necessary for proper development of hindwings in butterflies, beetles, and fruit flies (Tomoyasu et al., 2005; Weatherbee et al., 1998; Weatherbee et al., 1999). Morphological differences between hindwings in these insect orders are postulated to be due at least in part to differences in Ubx-regulated target gene sets, rather than to differences in Ubx expression pattern or level (Weatherbee et al., 1998). To understand how Ubx shapes development and how these structures have evolved, the target genes controlled by Ubx must be identified.

Previous work that has identified individual Ubx-regulated target genes has suggested that Ubx acts at multiple levels of a regulatory hierarchy, and controls many target genes directly (Weatherbee et al., 1998). A modest number of direct Ubx-regulated target genes in the haltere and other tissues has been identified by candidate gene approaches (Capovilla et al., 1994; Pearson et al., 2005; Vachon et al., 1992). In the haltere, UBX protein binds to cis-regulatory elements (CREs) of two direct targets, spalt and knot, which are each expressed in the wing and repressed in the haltere (Galant et al., 2002; Hersh and Carroll, 2005). Additional genes that are differentially expressed in wings and halteres have been identified (Crickmore and Mann, 2006; Mohit et al., 2006; Weatherbee et al., 1998), but whether these genes represent direct or indirect targets of UBX regulation is not known. Furthermore, while UBX can both positively and negatively regulate target genes (Capovilla et al., 1994; Vachon et al., 1992), the mechanisms that specify the sign of UBX regulation are not understood. By identifying a large pool of potential direct targets of UBX and characterizing UBX-regulated CREs, we aim to understand the organization and evolution of Hox-responsive CREs.

To identify genes that are differentially expressed in developing wing and haltere imaginal discs, we used Drosophila whole transcriptome and custom gene oligonucleotide microarrays. We confirmed the tissue specific expression of several candidate genes, and found that multiple genes are either haltere-specific, or have an expanded distribution or a higher level of expression in the haltere disc. We proceeded to identify and characterize cis-regulatory elements for the ana gene, which is expressed in a wing-specific pattern, and the CG13222 gene, which is expressed in a haltere-specific pattern. Ectopic expression of Ubx is sufficient to repress the ana CRE and activate the CG13222 CRE, indicating that both regulatory elements function downstream of UBX protein activity. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the CG13222 CRE is directly bound by UBX in vitro, and that a single, well-conserved UBX binding site is necessary for CRE activation in vivo. CG13222 encodes a component of the cuticle, and therefore likely represents a terminal differentiation target. Thus, UBX does not simply repress the genetic pathway for wing development in order to generate the dipteran haltere. Rather, UBX can also directly activate specific terminal targets to regulate haltere differentiation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains

We used the y1w1118 strain to obtain wild-type wing and haltere imaginal discs. Two strains with altered wing development were also employed: vg83b27 , in which cells in the wing pouch do not proliferate, and Cbx1/MKRS, in which UBX protein is inappropriately expressed in the posterior compartment of the wing disc (Figure 4A).

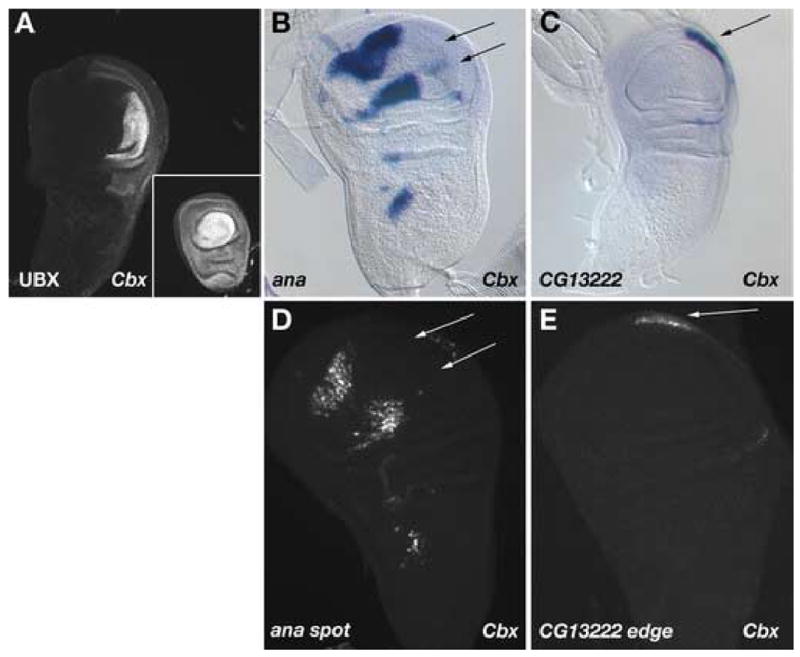

Figure 4. Misexpression of Ubx causes misregulation of wing- and haltere-specific genes.

(A) Wing and haltere imaginal discs from a Cbx1 mutant larva stained for UBX protein. The Cbx1 allele causes inappropriate expression of UBX protein in the posterior compartment of the developing wing imaginal disc without affecting expression of UBX in the haltere disc. (B) In situ hybridization of Cbx1 discs for ana transcript (compare to wild-type discs in Figure 1A). The posterior spots of ana gene expression are eliminated in Cbx1 mutant wing discs (arrows), whereas the anterior spots in both the pouch and notum are maintained. (C) In situ hybridization of Cbx1 discs for CG13222 transcript. The CG13222 transcript is now expressed in the wing discs of Cbx1 mutants (arrows), whereas it was restricted to the haltere disc in wild-type animals (compare to Figure 2A). (D) GFP reporter expression driven by the ana spot CRE is altered in Cbx1 mutant discs, by elimination of the posterior spots of expression (arrows). (E) The CG13222 edge CRE in Cbx1 mutant wing discs activates GFP reporter expression at the distal posterior edge of the wing disc.

Array sample preparation, labeling, hybridization and data analysis

Wing and haltere imaginal discs were dissected on ice from third instar yw larvae, and wing discs were collected from vg and Cbx larvae. Discs were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. We prepared total RNA from discs using Qiagen QIAshredder and Rneasy columns following the manufacturer’s instructions. We obtained approximately 11 μg total RNA from ~80 wild-type wing discs or Cbx mutant discs, 7.5 μg RNA from ~80 vg mutant discs, and 5 μg RNA from ~250 haltere discs. Three independent RNA samples were prepared from each tissue. For each sample, cDNA synthesis was performed with 5 μg total RNA as previously described (Nuwaysir et al., 2002). The sequence of the oligo-dT primer containing the T7 RNA polymerase promoter was 5’-GCA TTA GCG GCC GCG AAA TTA ATA CGA CTC ACT ATA GGG AGA-T21-V-3’. In vitro transcription labeling reactions were performed using the Enzo BioArray High Yield RNA transcript labeling kit.

Hybridization and signal extraction for each sample was performed as previously described (Nuwaysir et al., 2002). Two different microarrays were used for hybridization. The Drosophila whole transcriptome array contained 7 probe pairs (24 nt) per gene and covered 13,491 genes predicted in Drosophila Genome Release 2.0. The validation array contained 18 probe pairs per gene (24 nt) for 1388 genes (approximately one-half representing all transcription factors and signaling molecules in the genome, and one-half representing differentially expressed genes derived from the whole transcriptome screen), and replicated the entire array four times on each glass slide.

Two methods for the analysis of microarray expression data were used. First, mean difference values between perfect match and mismatch oligonucleotides were calculated for each gene (MAS method). Second, log base 2 values for only perfect match oligonucleotides were calculated for each gene (RMA method). We then used Significance Analysis of Microarrays (SAM) (Tusher et al., 2001) to identify transcripts that had significant expression differences between tissues. Data was analyzed as two-class, unpaired data, and the four replicates of each sample on the validation arrays were treated as blocks for the 10-Nearest Neighbor imputation engine. We set the SAM parameter in each analysis such that the median false discovery rate was less than one false positive (Δ ~ 2.0).

Complete whole-genome and validation array results are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). GEO accession numbers for array platforms are GPL4573 and GPL4568. GEO accession number for the array series is GSE6307.

In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry

We performed wing and haltere imaginal disc in situ hybridizations using minor modifications of a standard protocol (Sturtevant et al., 1993).

Third instar imaginal discs were dissected, fixed and immunostained as previously described (Galant et al., 2002). GFP protein fluorescence survived the fixation procedure and was visualized directly. UBX protein was detected using the FP 3.38 monoclonal antibody (Kelsh et al., 1994) (gift from R. White) and rhodamine-conjugated donkey anti-mouse secondary antibody (Jackson Labs). Imaging was performed on a Bio-rad MRC 1024 confocal microscope.

Reporter constructs

Fragments were amplified by PCR from Canton S Drosophila melanogaster genomic DNA and cloned into SMG2.0-GFP reporter plasmid (Gompel et al., 2005). Subclones of genomic regions exhibiting regulatory activity were generated by PCR or restriction digest. Details of cloning are available upon request. Transgenic lines were generated by standard P-element mediated transposition. GFP fluorescence in wing and haltere imaginal discs was assayed in a minimum of four independent transgenic lines.

Clonal analysis

Females of the genotype hsFLP122; FRT82B cu sr E[s] ca/TM6B were mated to males of the genotype P[w+:CG13222 edge-GFP] II; FRT82B Ubx6.28e11/TM6B. Clones lacking Ubx activity were generated by heat induction of FLP recombinase at 37°C for 45 minutes at 75–99 hours after egg laying (AEL). Imaginal discs from non-TM6B third instar larvae (genotype hsFLP122; P[w+:CG13222 edge-GFP]/+; FRT82B cu sr E[s] ca/FRT82B Ubx6.28e11) were dissected, fixed, and immunostained as described above.

Electromobility shift assays

Double-stranded oligonucleotides were radioactively labeled by end-filling dinucleotide TT overhangs on the 5’ and 3’ ends with [α-32P]dATP using Klenow enzyme. Labeled probes were incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature with 0, 0.4, 1.2, 3.7, 11, or 33 ng of UBX homeodomain in 20 mM Hepes pH 7.8, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 250 μg/ml BSA, 5 μg/ml poly(dI-dC) and 4% Ficoll. Samples were separated on a 5% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel (19:1 bis:acrylamide). Gels were fixed for 10 minutes in 10% acetic acid, dried on filter paper and exposed to a phosphorimager plate overnight. Oligonucleotide sequences analyzed were as follows: WT site 1, CGCAGATAAATTACACTGGCC; M1, CGCAGATAAGGCCCACTGGCC; WT site 2, GCCCGCGAGATTACCATCGAG; M2, GCCCGCGAGGGCCCCATCGAG.

RESULTS

Identification of differentially expressed genes in wing and haltere discs

We sought to identify genes expressed preferentially in wing or haltere imaginal discs to understand how the UBX homeoprotein modifies a developmental network to generate the morphologically distinct dipteran forewing and hindwing. Our strategy was to use microarray expression profiling to survey gene expression differences in these two tissues.

We generated labeled cRNA samples from wild-type wing imaginal discs, and from vg and Cbx mutant wing imaginal discs. The vg83b27 mutant wing discs have no VG protein present in the third larval instar, and thus do not develop a wing pouch, the region of the imaginal disc that contributes to the adult wing blade. Comparison of the wild-type expression profile to the profile of this mutant should reveal transcripts preferentially expressed in the wing pouch. In Cbx1 mutant wing discs UBX protein is inappropriately expressed in the posterior compartment of the disc. The expression profile of this mutant should identify transcripts that respond to UBX protein. Three independently isolated and labeled samples for each tissue were used to probe whole transcriptome microarrays based on Drosophila Genome Release 2.0. We determined by SAM analysis that 277 transcripts were expressed at significantly higher levels in wild-type wing discs than in vg mutant discs, 362 transcripts were expressed at significantly higher levels in wild-type wing discs than Cbx mutant discs, and 85 transcripts were expressed at higher levels in Cbx mutants than in wild-type wing discs.

Because the whole transcriptome screen was intended to be broadly inclusive, we designed an additional screen to validate the candidate transcripts. By reducing the number of genes on a second-generation microarray, we could increase the number of features per gene, thereby increasing the statistical reliability. We designed our validation arrays using the 724 transcripts identified in the first screen as the starting basis. In addition, we queried Flybase (Grumbling et al., 2006) for genes identified as transcription factors, involved in signal transduction, or expressed in or affecting wing, haltere, or other imaginal discs. These queries identified 896 genes for inclusion in the validation microarray. Many genes were represented in both the Flybase queries and SAM analysis. Together, these methods generated 1395 non-redundant genes for the validation microarray. Because some genes were eliminated and other genes were added during annotation of Drosophila Genome Release 3.0, the final validation array contains 1388 unique transcripts, approximately half of which were literature-derived and half of which were derived from the whole transcriptome expression profiling.

We probed the validation arrays with three independently isolated and labeled samples for each of the following tissues: wild-type wing and haltere imaginal discs; vg mutant wing discs; and Cbx mutant wing discs. We used SAM analysis to identify 18 genes that were expressed preferentially in haltere discs and 174 genes that were expressed preferentially in wing discs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Differentially expressed genes on validation array

| # genes significant by MAS | # genes significant by RMA | # genes (both) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ↑ Wing vs. Haltere | 314 | 203 | 174 |

| ↑ Haltere vs. Wing | 24 | 30 | 18 |

| ↑ Wing vs. Cbx | 140 | 108 | 93 |

| ↑ Cbx vs. Wing | 105 | 92 | 63 |

| ↑ Wing vs. Haltere, Cbx | 69 | 40 | 32 |

| ↑ Haltere, Cbx vs. Wing | 2 | 5 | 2 |

| ↑ Wing vs. vg | 229 | 150 | 136 |

| ↑ Wing, Haltere vs. vg | 67 | 63 | 54 |

The SAM procedure (Tusher et al., 2001) was performed on microarray values from indicated samples as described in Materials & Methods, employing both MAS and RMA values for that tissue. The number of genes calculated as significantly different in expression is indicated. Gene lists for both MAS and RMA values were compared, and the number of genes present in both lists is indicated. Wing-specific genes ana (16.9-fold difference), CG7201 (3.34-fold difference), and CG16884 (1.91-fold difference) are within both the combined W vs. H gene list and the combined W vs. vg gene list. Haltere-specific genes CG13222 (41.3-fold difference), CG8780 (1.98-fold difference) are within the combined H vs. W gene list and the H, C vs. W gene list, whereas the CG11641 (2.34-fold difference) expression value is only significantly different by the RMA method in both comparisons. Specific gene lists are available upon request.

Analysis of wing and haltere-specific gene expression in situ

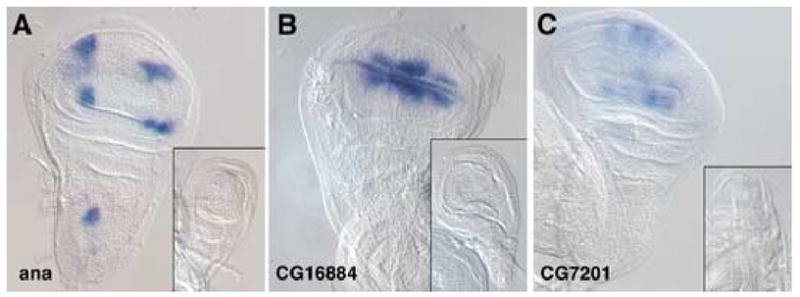

To verify that these transcripts were differentially expressed we performed in situ hybridizations on wing and haltere imaginal discs. We surveyed approximately one hundred transcripts, some of which have been characterized elsewhere (Butler et al., 2003; Mohit et al., 2006), and present several of the expression patterns here. For example, we found that anachronism (ana) expression is absent from the developing haltere disc (Figure 1A), and we observed the previously characterized (Butler et al., 2003) pattern of wing disc expression in several discrete clusters of expression. The novel genes, CG16884 and CG7201, were also expressed in the wing, but not haltere, disc (Figure 1B, 1C). CG16884 is expressed at the dorsal/ventral boundary, and the pattern of CG7201 is suggestive of presumptive wing veins, so both of these genes may be related to the development of wing-specific sensory or support structures that are not present in the haltere.

Figure 1. Genes expressed preferentially in wing discs.

Expression patterns of various transcripts were analyzed in wing and haltere (inset) imaginal discs by in situ hybridization. (A) anachronism (ana) is expressed in four spots in the wing pouch and an additional spot in the notum, but expression is entirely absent from the haltere. (B) CG16884 is expressed strongly at the dorsal-ventral compartment boundary in the wing pouch, as well extending a short distance into these compartments, but expression is also absent from the haltere disc. (C) CG7201 is expressed in longitudinal stripes that may correspond to wing vein primordia, and is absent from the haltere disc.

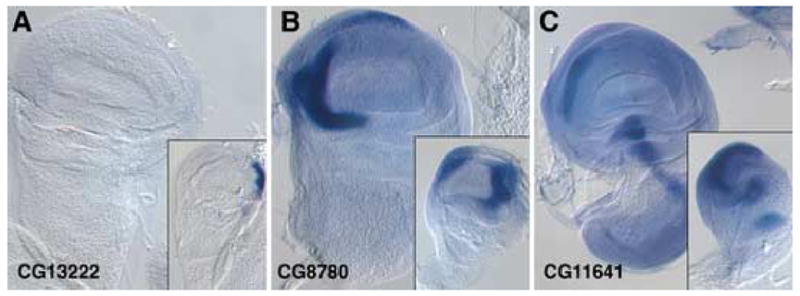

We also identified several genes that are preferentially expressed in the haltere imaginal disc (Figure 2). CG13222, predicted to encode a component of cuticle, is expressed in a small patch of cells at the distal posterior edge of the haltere disc. This patch of cells is located outside of the pouch region, which forms the balloon-like haltere structure. These cells may contribute to the hinge or pleura (Bryant, 1975). CG8780, a novel gene, is expressed in a single crescent in the wing disc, but is expressed in two symmetric crescents in the haltere disc. A third gene, CG11641, is expressed in a similar crescent as CG8780 as well as additional clusters of cells in the hinge and body wall region of the wing disc. The same spatial pattern is present for CG11641 in the haltere, but the level of expression appears to be higher in the haltere disc. These genes, then, are haltere-specific (CG13222), have an expanded distribution in the haltere (CG8780), or are expressed at a higher level in the haltere (CG11641).

Figure 2. Genes expressed preferentially in haltere discs.

Expression patterns of various transcripts were analyzed in wing and haltere (inset) imaginal discs by in situ hybridization. (A) CG13222 expression is absent from the wing disc, but is expressed strongly at the posterior edge of the haltere disc. These cells appear to be located outside of the pouch region of the haltere disc, and to contribute to body wall structures. (B) CG8780 is expressed strongly in a single crescent in the anterior portion of the wing disc, but is expressed in both the anterior and posterior regions of the haltere disc. (C) CG11641 is expressed in a similar pattern in both the wing and haltere discs—the anterior edge of the pouch and several spots in the hinge region—but at a higher level in the haltere disc than in the wing.

Identification of specific cis-regulatory elements controlling gene expression in wing and haltere discs

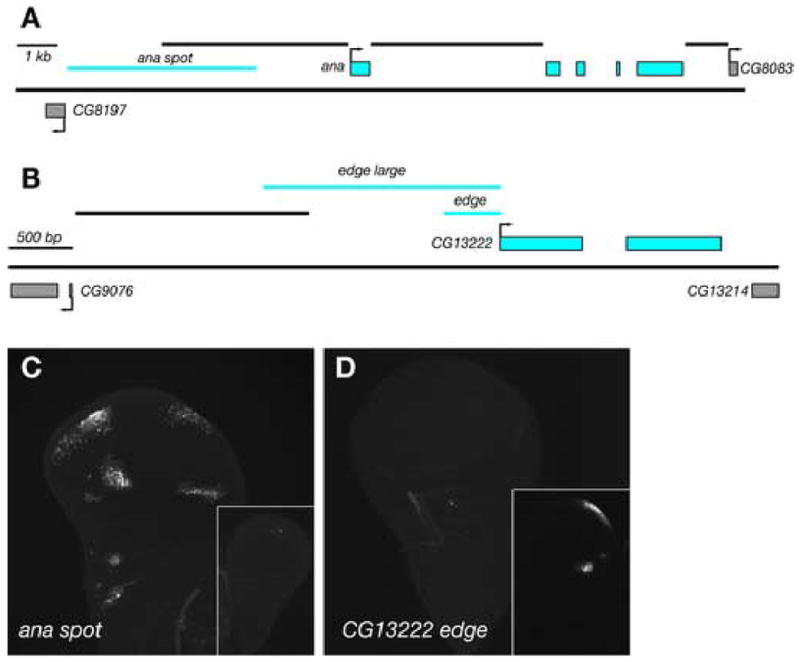

Genes we identified as preferentially expressed in the wing or haltere are potential targets for either UBX repression (wing-specific) or activation (haltere-specific). To determine whether these genes are regulated, either directly or indirectly, by UBX we sought to identify cis-regulatory elements (CREs) of these genes that drive expression specifically in the wing and haltere. We generated reporter constructs from non-coding genomic DNA, including all intergenic DNA and large segments of intronic DNA, associated with the ana and CG13222 genes (Figure 3). We identified a region of DNA approximately 6 kb 5’ of the ana gene that drives GFP reporter expression in four clusters of cells in the wing pouch and an additional cluster of cells in the body wall region of the wing disc (Figure 3C). The pattern of reporter expression recapitulates the pattern of ana expression observed by in situ hybridization in the wing, and the CRE does not drive reporter expression in the haltere disc. We termed this CRE the ana spot element.

Figure 3. Identification of wing- and haltere-specific regulatory elements.

(A) Genomic region of ana. Exons of ana are indicated by blue boxes and exons of neighboring genes are indicated by grey boxes. Sequences immediately 5’, 3’, and in the first intron of the ana gene that do not drive reporter expression in wing or haltere discs are indicated by black lines. The ana spot region (2R: 4573748..4578555), ~ 6 kb upstream, which possesses regulatory activity, is indicated by a blue line. (B) Genomic region of CG13222. The smallest construct tested for regulatory activity, edge, comprises 459 bp (2R: 6780553..6781011) immediately 5’ of the CG13222 gene. (C) The ana spot CRE drives GFP expression in a pattern that recapitulates the endogenous pattern of expression in the wing disc but does not drive expression in the haltere disc. (D) The CG13222 edge CRE drives GFP expression in cells at the posterior edge of the haltere disc, as well as at an additional spot in the hinge region.

We also identified a CRE immediately 5’ of the CG13222 gene that drives GFP reporter expression in a cluster of cells at the posterior edge of the haltere disc, corresponding to the expression pattern of CG13222 observed by in situ hybridization (Figure 3D). We also observed GFP fluorescence in an additional small cluster of cells in the hinge region of the haltere disc that was not observed by in situ hybridization. We termed this CRE the CG13222 edge element.

ana, CG13222 and their cis-regulatory elements respond to Ubx

If the genes we identified as differentially expressed in the wing and haltere are indeed targets of Ubx, then they and their associated regulatory elements should respond to changes in the dosage of Ubx. We first tested the responsiveness of the wing-specific ana gene and the haltere-specific CG13222 gene to Ubx by performing in situ hybridizations on wing imaginal discs from Cbx1 mutant animals. The Cbx1 allele causes misregulation of the Ubx gene, causing ectopic expression of UBX protein in the posterior compartment of the wing disc, without affecting the level of UBX protein in the haltere disc (Figure 4A). In Cbx1 mutant wing discs the ana gene is expressed in three clusters in the anterior wing disc and body wall region, but the two clusters normally found in the posterior wing disc are absent (Figure 4B), indicating that the ectopic Ubx expression in the posterior wing disc has repressed ana gene expression. CG13222, which is not expressed in wild-type wing discs, is expressed at the posterior edge of Cbx1 mutant discs (Figure 4C), indicating that CG13222 is activated in response to ectopic Ubx expression.

We also tested the activity of identified CREs in a Cbx1 mutant background to determine whether they contained sequences that could respond to Ubx expression. The ana spot CRE drives GFP expression in anterior clusters of cells in Cbx1 mutant discs, but the posterior clusters of GFP-positive cells are absent (Figure 4D), as expected. Similarly, the CG13222 edge CRE activates GFP expression in the wing in Cbx1 mutant discs (Figure 4E). Thus, expression of Ubx in wing tissue is sufficient to repress ana spot expression and to activate CG13222 edge expression.

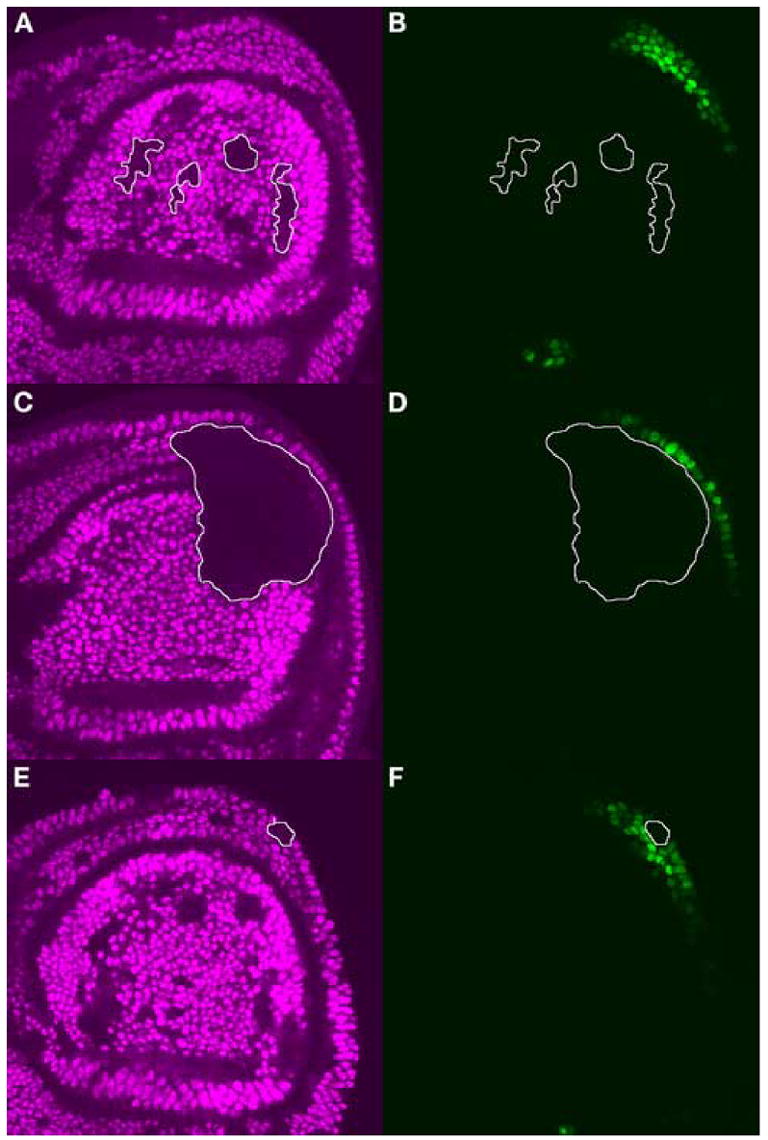

We next asked whether Ubx activity is necessary for the activity of the CG13222 edge CRE by generating homozygous mutant Ubx− clones in the haltere disc and assaying reporter expression. In clones that did not overlap the natural domain of reporter expression at the posterior edge of the haltere (Figure 5A, 5B), there was no effect on GFP expression driven by CG13222 edge. However, in clones that either overlapped with or were entirely within the normal domain of expression (Figure 5C–F), GFP reporter expression was eliminated in a cell autonomous manner. Thus, Ubx function is necessary within individual cells at the posterior edge of the haltere for expression of CG13222 through the CG13222 edge CRE. This result is consistent with the possibility of direct regulation of CG13222 by UBX protein.

Figure 5. Cell-autonomous loss of CG13222 edge expression in Ubx− clones.

Homozygous clones of Ubx6.28/Ubx6.28 were generated in the haltere disc. Discs were labeled for UBX protein (purple) and GFP protein (green). Ubx− clones of interest are outlined in white. (A) Clones that do not overlap the domain of CG13222 expression have no effect (B) on GFP expression driven by the CG13222 edge CRE. (C) A large Ubx− clone that overlaps the posterior edge of the haltere disc eliminates GFP expression (D) in the region of the clone. (E) A small Ubx− clone within the domain of CG13222 expression eliminates GFP expression (F) within that clone.

The CG13222 edge cis-regulatory element is a direct target of UBX

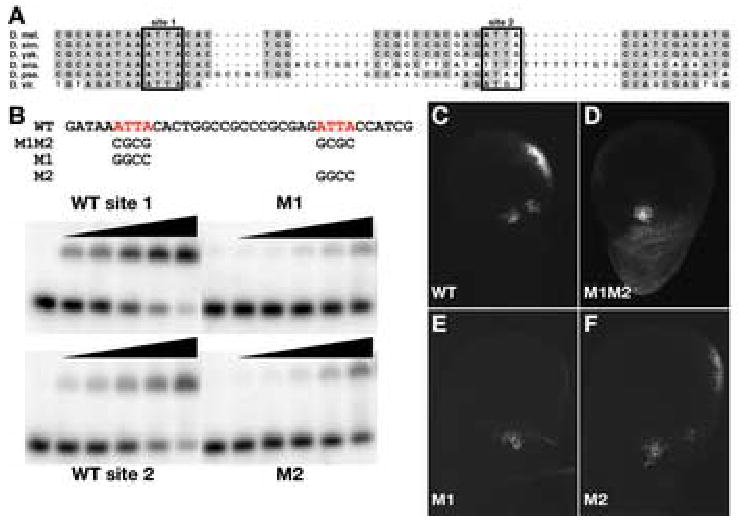

The cell-autonomous response of the CG13222 edge CRE indicates that this regulatory element acts downstream of Ubx. To determine whether the response to Ubx is direct or indirect, we identified potential UBX protein binding sites in the CRE and tested the effect of mutating those sites on both protein binding in vitro and regulatory activity in vivo. UBX protein, like most homeobox proteins, binds to a core sequence of TAAT. The CG13222 edge CRE contains only two of these TAAT core sequences. Using the Vista browser of Drosophila genome alignments at http://pipeline.lbl.gov/cgi-bin/gateway2?bg=dm1 (Frazer et al., 2004), we determined that one of these TAAT sequences is conserved in all species we examined, including the most evolutionary distant D. virilis, whereas the second motif is shared only with D. simulans, a close relative of D. melanogaster (Figure 6A).

Figure 6. UBX binding sites are necessary for activity of the CG13222 edge regulatory element in vivo.

(A) Sequence alignment of a portion of the CG13222 edge CRE in six Drosophilid species (D. melanogaster, D. simulans, D. yakuba, D. ananassae, D. pseudoobscura, D. virilis). UBX site 1 is highly conserved in all six species, representing approximately 60 million years of evolutionary distance. UBX site 2 is less well conserved, and appears to be present in only the closely related D. melanogaster and D. simulans. (B) Electromobility shift assays of oligonucleotides containing core UBX binding sites. Oligonucleotides containing either site 1 or site 2 were incubated with increasing amounts of UBX homeodomain. Lane 1 in each panel contains no UBX protein. Lanes 2–6 in each panel contain 3-fold increases of protein, ranging from 0.4 ng to 33 ng of UBX homeodomain. Binding of UBX to wild-type site 2 appears approximately 10-fold weaker than to wild-type site 1. Mutation of site 1 (M1) reduces UBX affinity by at least 30-fold compared to wild-type site 1. Mutation of site 2 (M2) reduces the affinity of UBX by approximately 10-fold compared to wild-type site 2. (C) The 459 bp CG13222 edge CRE that drives reporter expression in the haltere disc contains only two UBX core DNA binding sites (TAAT/ATTA), located within 20 bp of each other. (D) Mutation of both sites (M1M2) eliminates GFP reporter expression at the posterior edge of the haltere disc while maintaining the cluster of cells in the hinge region. (E) Mutation of site 1 alone (M1) eliminates GFP reporter expression, whereas (F) mutation of site 2 alone (M2) has no detectable effect on cis-regulatory activity.

We tested the ability of UBX homeodomain to bind these sequences in vitro by electrophoretic mobility shift assays (Figure 6B). Purified UBX homeodomain binds the wild-type site 1, tightly conserved within the Drosophila genus, with high affinity, and mutation of this site to a GC-rich sequence reduces UBX affinity by at least 30-fold. UBX binds to wild-type site 2, the variable site, with approximately 10-fold lower affinity than site 1. Nevertheless, mutation of site 2 reduces UBX binding by a further 10-fold, suggesting that site 2 is a specific binding site for UBX homeodomain, though a lower affinity site than the well-conserved site 1.

Having established the ability of UBX protein to bind these sites in vitro, we mutated these sequences and tested the activity of the mutated CRE in vivo. Whereas the wild-type CRE drives GFP expression in both the body wall and the posterior edge of the haltere disc (Figure 6C), the double mutant (M1M2) CRE fails to drive expression at the posterior edge of the disc (Figure 6D). Mutation of well-conserved site 1 alone (M1) completely eliminates reporter expression (Figure 6E), whereas mutation of the variable site 2 has little effect on expression (Figure 6F). Therefore, a single UBX binding site (M1) appears to be necessary for expression regulated by the CG13222 edge CRE. The location of this single binding site within a larger block of conserved sequence may suggest that additional, adjacent sequences are important for the function of this CRE.

DISCUSSION

We used microarrays to define a candidate set of direct target genes of the UBX homeoprotein in the haltere imaginal disc. We identified cis-regulatory elements for the ana gene, repressed by UBX in the haltere disc, and CG13222, activated by UBX in the haltere disc. UBX directly binds the haltere-specific CG13222 CRE in vitro, and a single UBX binding site is necessary for in vivo activation of a reporter gene. Our results indicate that UBX directly regulates genes throughout the wing development network, both through activation and repression, to specify the development of the haltere and third thoracic segment. Further, responsiveness to UBX may only require single sites, but the placement of these sites within the context of existing regulatory elements may be important.

Nature of the UBX target gene set in the haltere disc

Changes in either the pattern of Hox gene expression or the target gene sets that respond to a particular Hox gene are widely considered to be important for the evolution of diverse morphologies within the animal kingdom (Carroll, 1995; Pearson et al., 2005; Weatherbee and Carroll, 1999). Whereas it has been well established that changes in Hox gene expression patterns correlate with morphological differences (Averof and Patel, 1997; Burke et al., 1995; Cohn and Tickle, 1999), it has not been possible to define the entire set of Hox-responsive genes in a particular tissue, let alone how such a gene set has changed during evolution. Individual cases have related the loss of Hox binding sites to a change in appearance (Jeong et al., 2006), but it is still not clear how a target gene set has changed over evolutionary time.

A necessary first step is to accurately define target gene sets within serial homologs specified by Hox gene function. Several groups have used expression profiling with microarrays to identify gene sets acting downstream of Hox genes in mouse embryo fibroblasts (Lei et al., 2006; Williams et al., 2005), spinal cord (Hedlund et al., 2004), and digits and genitalia (Cobb and Duboule, 2005). In Drosophila, gene sets expressed in the developing wing pouch and body wall (Butler et al., 2003), or wing and haltere imaginal discs have also been identified (Mohit et al., 2006). Because it is difficult to identify cis-regulatory elements rapidly, the directness of regulation by Hox proteins has not been evaluated in vivo in these cases.

Most of these studies have emphasized the role of Hox genes as master regulators at the apex of a regulatory cascade. The best characterized targets of regulation by Ubx in the haltere are the components of the anterior/posterior (A/P) and dorsal/ventral (D/V) signaling pathways that pattern the dorsal appendages. Cell fates within the haltere are affected by Ubx repression of Wingless (Wg) signaling at the D/V boundary (Mohit et al., 2003; Weatherbee et al., 1998). Two genes repressed in the haltere, Cyp310a1 and CG17278, appear to act downstream of Wg in the wing (Butler et al., 2003; Mohit et al., 2006). However, their absence from the haltere may be due to reduction in Wg signaling rather than a direct response to UBX protein. Ubx also regulates cell proliferation in the haltere by influencing expression of dpp, thickveins (tkv), and master of thickveins (mtv), thereby altering the level and extent of Dpp pathway activation (Crickmore and Mann, 2006). However, in these cases, the CREs remain to be isolated and characterized. The two direct targets of Ubx in the haltere for which CREs have been identified, knot and sal (Galant et al., 2002; Hersh and Carroll, 2005), encode transcription factors that act downstream of Hedgehog (Hh) and Decapentaplegic (Dpp) signaling events that establish A/P patterning. However, even these two direct targets do not represent the highest level in the wing patterning regulatory hierarchy.

An alternative view to that of Hox genes as master regulators is to consider that they may act at multiple levels, even to the point of directly regulating terminal differentiation genes (Weatherbee et al., 1998). The 14 candidate HoxD-regulated genes in developing mouse limbs and genitalia do not represent any members of the classical FGF, Hh, Dpp, or Wg signaling pathways (Cobb and Duboule, 2005). Since candidates include kinases, and receptors, it is likely that they still act as signaling molecules, but perhaps closer to the level of terminal differentiation rather than pattern formation. Hox genes also directly control regulators of apoptosis (Knosp et al., 2004; Lohmann et al., 2002). Finally, ectopic Ubx can alter the fate of wing cells as late as 30 hours into pupation (Roch and Akam, 2000), suggesting that it has the capacity to affect terminal differentiation, as the general pattern formation process in the wing is already completed by this point. Our analysis of the CG13222 gene, predicted to encode a protein similar to structural components of insect cuticle (GO:0008010), has shown that it is directly activated by the binding of UBX protein to a CRE located less than 200 bp 5’ of the transcription start site. Because a cuticular component is unlikely to regulate other target genes, regulation of CG13222 by UBX probably represents direct control of a terminal differentiation gene. Since UBX also directly regulates the expression of the Knot and Sal transcription factors, our results strongly support the model whereby UBX acts at multiple levels within the wing regulatory hierarchy.

Organization and evolution of UBX-responsive cis-regulatory sequences

The nature of Hox-responsive target gene sets will be influenced, at least in part, by how easily Hox-responsive CREs can evolve. The ease with which Hox-responsive CREs evolve will depend on the complexity (or simplicity) of sequences required for Hox regulation. By defining UBX target gene sets and exploring the organization of several directly regulated CREs, we can begin to understand the underlying cis-regulatory sequence requirements for regulation by Hox genes.

The DNA binding specificity of Hox proteins is relatively low, and even when optimal binding sequences have been selected in vitro (Ekker et al., 1991), the in vivo response elements do not always match the biochemically defined sequence. Through interaction with PBC/EXD and MEIS/HTH proteins, Hox target selectivity can be increased by binding to a composite binding site (Chan et al., 1994). However, UBX-responsive CREs in the haltere, including those for sal, knot, and CG13222, do not contain these composite binding sites. In these instances, UBX could either act by binding to DNA as a monomer or by binding to DNA with a different collaborating factor. The TAAT core sequences in the sal1.1 and CG13222 edge CREs are embedded within larger blocks of sequence conservation. Such a level of conservation in the face of lax constraints for UBX binding is suggestive of constraints imposed by other sequence-specific factors acting at these CREs. These collaborating factors could represent actual co-factors that physically interact with UBX protein, but also could represent factors that act independent of physical interaction. In this latter case, the transcriptional output of the CRE would be determined by the combined additive or synergistic inputs of the collaborating factors. Even within single cells, UBX protein can activate some individual target genes while repressing others. The action of collaborating factors could also provide a mechanism for UBX to discriminate between activation and repression in such a target-specific manner.

If, however, UBX protein can regulate target genes in the haltere through monomer binding, a greater number of monomer binding sites is predicted to produce a stronger UBX-responsive output (Galant et al., 2002). In that case, the role of just a single site in CG13222 edge in activation by UBX is surprising. If single TAAT core sequences can generally mediate such a significant response, then the acquisition of new targets by UBX during evolution may occur with high frequency. On the other hand, if single TAAT sites are sufficient, then most genes in the Drosophila genome should be directly regulated by UBX or other Hox proteins. We do not believe that virtually all genes are direct targets of UBX, so how can the activity of a single 4 bp core sequence and the frequency of such sequences in the genome be reconciled? One possibility is that single sites are sufficient, but only when they arise within the context of previously existing CREs. That is, an active CRE with a factor or factors already binding to it is then co-opted for UBX-responsiveness by the evolution of a single core binding sequence. The position of the UBX binding site within the existing CRE may also be significant. In CREs of the Drosophila immune system and neurogenic ectoderm, the relative arrangement of sites for multiple factors is important for enhancer activity (Erives and Levine, 2004; Senger et al., 2004), and simply introducing UBX binding sites in UBX-nonresponsive CREs does not impart UBX regulation (C. Walsh & S.B.C, manuscript in preparation). Once UBX response mediated by a single site is achieved, it may then be modified by the gain of additional binding sites. The insertion of UBX sites into previously active CREs co-opted for Hox regulation may account for the high degree of sequence conservation surrounding UBX binding sites in sal1.1 and CG13222 edge. However, the conservation of the UBX sites themselves within drosophilids indicates that neither the CREs nor their regulation by UBX evolved recently.

Factors that collaborate with Hox proteins appear to be important for generating appropriate transcriptional outputs and may influence the evolution of Hox-responsive cis-regulatory elements. Therefore, to understand how UBX and other Hox proteins regulate their target genes and the evolution of Hox-responsive CREs, we must begin to identify the full range of collaborating factors that are involved.

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Beachy for purified UBX homeodomain and R. White for anti-Ubx monoclonal antibody. B. H. was supported by NIH NRSA F32GM65737 and S.B.C. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Averof M, Patel NH. Crustacean appendage evolution associated with changes in Hox gene expression. Nature. 1997;388:682–6. doi: 10.1038/41786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant PJ. Pattern formation in the imaginal wing disc of Drosophila melanogaster: fate map, regeneration and duplication. J Exp Zool. 1975;193:49–77. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401930106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke AC, Nelson CE, Morgan BA, Tabin C. Hox genes and the evolution of vertebrate axial morphology. Development. 1995;121:333–46. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.2.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler MJ, Jacobsen TL, Cain DM, Jarman MG, Hubank M, Whittle JRS, Phillips R, Simcox A. Discovery of genes with highly restricted expression patterns in the Drosophila wing disc using DNA oligonucleotide microarrays. Development. 2003;130:659–670. doi: 10.1242/dev.00293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capovilla M, Brandt M, Botas J. Direct regulation of decapentaplegic by Ultrabithorax and its role in Drosophila midgut morphogenesis. Cell. 1994;76:461–75. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll SB. Homeotic genes and the evolution of arthropods and chordates. Nature. 1995;376:479–85. doi: 10.1038/376479a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SK, Jaffe L, Capovilla M, Botas J, Mann RS. The DNA binding specificity of Ultrabithorax is modulated by cooperative interactions with extradenticle, another homeoprotein. Cell. 1994;78:603–15. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90525-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb J, Duboule D. Comparative analysis of genes downstream of the Hoxd cluster in developing digits and external genitalia. Development. 2005;132:3055–67. doi: 10.1242/dev.01885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn MJ, Tickle C. Developmental basis of limblessness and axial patterning in snakes. Nature. 1999;399:474–9. doi: 10.1038/20944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crickmore MA, Mann RS. Hox control of organ size by regulation of morphogen production and mobility. Science. 2006;313:63–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1128650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekker SC, Young KE, von Kessler DP, Beachy PA. Optimal DNA sequence recognition by the Ultrabithorax homeodomain of Drosophila. Embo J. 1991;10:1179–86. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb08058.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erives A, Levine M. Coordinate enhancers share common organizational features in the Drosophila genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3851–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400611101. Epub 2004 Mar 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazer KA, Pachter L, Poliakov A, Rubin EM, Dubchak I. VISTA: computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucl Acids Res. 2004;32:W273–279. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galant R, Walsh CM, Carroll SB. Hox repression of a target gene: extradenticle-independent, additive action through multiple monomer binding sites. Development. 2002;129:3115–26. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.13.3115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gompel N, Prud'homme B, Wittkopp PJ, Kassner VA, Carroll SB. Chance caught on the wing: cis-regulatory evolution and the origin of pigment patterns in Drosophila. Nature. 2005;433:481–7. doi: 10.1038/nature03235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grumbling G, Strelets V The FlyBase Consortium. FlyBase: anatomical data, images and queries. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D484–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedlund E, Karsten SL, Kudo L, Geschwind DH, Carpenter EM. Identification of a Hoxd10-regulated transcriptional network and combinatorial interactions with Hoxa10 during spinal cord development. J Neurosci Res. 2004;75:307–19. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersh BM, Carroll SB. Direct regulation of knot gene expression by Ultrabithorax and the evolution of cis-regulatory elements in Drosophila. Development. 2005;132:1567–77. doi: 10.1242/dev.01737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong S, Rokas A, Carroll SB. Regulation of body pigmentation by the Abdominal-B Hox protein and its gain and loss in Drosophila evolution. Cell. 2006;125:1387–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelsh R, Weinzierl RO, White RA, Akam M. Homeotic gene expression in the locust Schistocerca: an antibody that detects conserved epitopes in Ultrabithorax and abdominal-A proteins. Dev Genet. 1994;15:19–31. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020150104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knosp WM, Scott V, Bachinger HP, Stadler HS. HOXA13 regulates the expression of bone morphogenetic proteins 2 and 7 to control distal limb morphogenesis. Development. 2004;131:4581–92. doi: 10.1242/dev.01327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei H, Juan AH, Kim MS, Ruddle FH. Identification of a Hoxc8-regulated transcriptional network in mouse embryo fibroblast cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10305–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603552103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis EB. A gene complex controlling segmentation in Drosophila. Nature. 1978;276:565–70. doi: 10.1038/276565a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohmann I, McGinnis N, Bodmer M, McGinnis W. The Drosophila Hox gene deformed sculpts head morphology via direct regulation of the apoptosis activator reaper. Cell. 2002;110:457–66. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahfooz NS, Li H, Popadic A. Differential expression patterns of the hox gene are associated with differential growth of insect hind legs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4877–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401216101. Epub 2004 Mar 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohit P, Bajpai R, Shashidhara LS. Regulation of Wingless and Vestigial expression in wing and haltere discs of Drosophila. Development. 2003;130:1537–1547. doi: 10.1242/dev.00393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohit P, Makhijani K, Madhavi MB, Bharathi V, Lal A, Sirdesai G, Reddy VR, Ramesh P, Kannan R, Dhawan J, Shashidhara LS. Modulation of AP and DV signaling pathways by the homeotic gene Ultrabithorax during haltere development in Drosophila. Dev Biol. 2006;291:356–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuwaysir EF, Huang W, Albert TJ, Singh J, Nuwaysir K, Pitas A, Richmond T, Gorski T, Berg JP, Ballin J, McCormick M, Norton J, Pollock T, Sumwalt T, Butcher L, Porter D, Molla M, Hall C, Blattner F, Sussman MR, Wallace RL, Cerrina F, Green RD. Gene expression analysis using oligonucleotide arrays produced by maskless photolithography. Genome Res. 2002;12:1749–1755. doi: 10.1101/gr.362402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson JC, Lemons D, McGinnis W. Modulating Hox gene functions during animal body patterning. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:893–904. doi: 10.1038/nrg1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roch F, Akam M. Ultrabithorax and the control of cell morphology in Drosophila halteres. Development. 2000;127:97–107. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senger K, Armstrong GW, Rowell WJ, Kwan JM, Markstein M, Levine M. Immunity regulatory DNAs share common organizational features in Drosophila. Mol Cell. 2004;13:19–32. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00500-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern DL. A role of Ultrabithorax in morphological differences between Drosophila species. Nature. 1998;396:463–6. doi: 10.1038/24863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturtevant MA, Roark M, Bier E. The Drosophila rhomboid gene mediates the localized formation of wing veins and interacts genetically with components of the EGF-R signaling pathway. Genes Dev. 1993;7:961–73. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.6.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomoyasu Y, Wheeler SR, Denell RE. Ultrabithorax is required for membranous wing identity in the beetle Tribolium castaneum. Nature. 2005;433:643–7. doi: 10.1038/nature03272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5116–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vachon G, Cohen B, Pfeifle C, McGuffin ME, Botas J, Cohen SM. Homeotic genes of the Bithorax complex repress limb development in the abdomen of the Drosophila embryo through the target gene Distal-less. Cell. 1992;71:437–50. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90513-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatherbee SD, Carroll SB. Selector genes and limb identity in arthropods and vertebrates. Cell. 1999;97:283–6. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80737-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatherbee SD, Halder G, Kim J, Hudson A, Carroll S. Ultrabithorax regulates genes at several levels of the wing-patterning hierarchy to shape the development of the Drosophila†haltere. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1474–1482. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.10.1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatherbee SD, Nijhout HF, Grunert LW, Halder G, Galant R, Selegue J, Carroll S. Ultrabithorax function in butterfly wings and the evolution of insect wing patterns. Current Biology. 1999;9:109–115. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams TM, Williams ME, Kuick R, Misek D, McDonagh K, Hanash S, Innis JW. Candidate downstream regulated genes of HOX group 13 transcription factors with and without monomeric DNA binding capability. Dev Biol. 2005;279:462–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]