Abstract

Maspin, a serine protease inhibitor, was originally reported as a tumor suppressor gene in breast and prostatic cancers. We examined maspin expression and/or the allele-specific methylation status in four gastric cancer cell lines, as well as normal, metaplastic, and cancerous epithelia obtained from 50 gastric cancer patients. Three gastric cancer cell lines exhibiting maspin overexpression showed hypomethylation at either both alleles or a haploid allele. Only one cell line (GCIY) was maspin-negative but maspin expression was reactivated after treatment with a demethylating agent, 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine. Dense and diffuse immunoreactivity for maspin was observed in 40 (80%) of 50 gastric cancers and all gastric normal epithelia (GNE) with intestinal metaplasia (IM), but not in GNE without IM. We further analyzed the allele-specific methylation status in 10 of 50 cases subjected to immunohistochemistry by the crypt isolation technique followed by a bisulfite genome sequencing method. The maspin gene promoter region of all GNE without IM was hypermethylated on both alleles whereas those with IM frequently represented the haploid type of hypomethylation status. In six of seven gastric cancers in which crypt isolation was possible, demethylation frequently occurred and extended to both alleles. Maspin mRNA was amplified from GNE with IM and cancerous crypts but not from GNE without IM. These results suggest that demethylation at the maspin gene promoter disrupts the cell-type-specific gene repression in both GNE and gastric cancer.

Maspin, a mammary serine protease inhibitor, was originally identified in normal mammary epithelium by subtractive hybridization. 1 A maspin-transfected mammary cancer cell line had reduced capacity for tumorigenesis and metastasis in nude mice. 1 Maspin has been shown to have tumor suppressive activity attributable to inhibition of breast cancer cell motility, invasion, and metastasis. 2-7 Loss of maspin protein expression has been observed frequently and is associated with poor prognoses in breast, prostatic, and oral cancers. 8-11 Recent studies have suggested that maspin interacts with the p53 tumor suppressor pathway 12 and may function as an inhibitor of angiogenesis 13 in vitro and in vivo. These observations indicate that maspin acts as a tumor suppressor gene. However, it has been reported that maspin is overexpressed in pancreatic 14 and ovarian cancers, 15 whereas their normal tissues are maspin-negative. Precancerous lesions also express maspin protein and its up-regulation is highly correlated with malignant behavior. 15 In these tumors, maspin seemed to behave as an oncogene rather than a tumor suppressor gene. Thus, paradoxical maspin expression has been described in various cancer cell types.

In gastric cancer, there have been two conflicting reports. Maass and colleagues 14 failed to detect maspin mRNA in six gastric cancer cell lines by Northern blot analysis. Later, an immunohistochemical study detected frequent maspin overexpression in tumor tissues and intestinal metaplasia (IM) but not in gastric normal epithelium (GNE) without IM. 16 Maspin expression and its functional significance in gastric epithelium and cancer cells have not fully been elucidated.

To clarify the significance of maspin gene expression in gastric carcinogenesis, its regulation mechanisms have to be examined in GNE and cancer cells. Recently, Futscher and colleagues 17 showed that the maspin expression of normal cells is regulated by epigenetic modifications in a cell-type-specific manner. The maspin-positive cells (mammary and prostatic epithelia, and skin and oral keratinocytes) showed no methylation at the CpG islands of the maspin gene promoter region. 17 By contrast, maspin-negative cells (skin fibroblast, lymphocytes, heart, liver, and bone marrow) showed extensive methylation. 17 Futscher and colleagues 17 and Costello and Vertino 18 provided a new insight, demonstrating that cell-type-specific gene regulation was controlled by epigenetic modifications. Moreover, aberrant methylation of maspin gene CpG islands is associated with silencing of the gene expression in breast cancer cells. Treatment with a demethylation agent [5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-Aza-dC)] reactivated maspin expression in these cells. 19 These data suggested that epigenetic modification of the maspin gene might play an important role in not only the establishment and maintenance of normal cells in a cell-type-specific manner but also tumor progression of breast cancers.

Epigenetic modifications involving several tumor suppressor genes were examined in gastric precancerous epithelium and cancer cells. Aberrant methylations in tumor-related genes (p16, p15, p14, E-cadherin, and hMLH1) accumulated in the sequence from precancerous lesions (gastric adenoma and epithelium with IM) to cancers. 20-22 Epigenetic changes have been recognized as an important mechanism underlying gastric carcinoma progression, 23-30 whereas the methylation status of the maspin gene has never been examined.

We analyzed cytosine methylation of the maspin gene promoter region and its mRNA and protein expression in GNE, with or without IM, and cancer cells. To eliminate stromal cell contamination, we used the crypt isolation technique, 31,32 and the methylation status was determined allele specifically by the bisulfite genome-sequencing method. 33

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Tissue Samples

Four gastric cancer cell lines (MKN7, MKN28, MKN74, and GCIY) were obtained from Riken Cell Bank (Tsukuba, Japan). All cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 10% fetal bovine serum under the recommended conditions. The tumor and matching normal tissue samples subjected to crypt isolation were obtained surgically from 10 patients with gastric cancer. For immunohistochemical staining, 40 additional patients with gastric cancer were examined. Permission for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (Iwate Medical University School of Medicine, Morioka, Japan) and written consent was obtained from all patients before surgery.

Crypt Isolation and Extraction of DNA and RNA

Just after surgical excision, tissue specimens were obtained from the cancerous lesion, and unaffected areas of the corpus and pyloric parts of the stomach, and cut into 2-mm squares. The crypts were isolated as previously described; 31,32 briefly, the tissue was incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes in calcium- and magnesium-free Hanks’ balanced salt solution containing 30 mmol/L of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid. The crypts were then stirred in calcium- and magnesium-free Hanks’ balanced salt solution. The isolated crypts obtained from the noncancerous lesion were stained with Alcian blue (pH 2.5) to identify the goblet cells. Subsequently, the isolated crypts were divided into two groups: intestinal metaplastic and nonmetaplastic epithelia. DNA and RNA were isolated for the bisulfite modification and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RQ-PCR), respectively. Genomic DNA was isolated with a Puregene DNA isolation kit (Gentra Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) and total RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). mRNA was reverse-transcribed with the ThermoScript RT-PCR system and oligo (dT) (Invitrogen) to produce cDNA.

Bisulfite Modification and PCR Amplification

Bisulfite-modified DNA was examined for the methylation status of 19 CpG dinucleotides within the maspin gene promoter region. 19,34 Genomic DNA was digested by PstI, then subjected to bisulfite modification as described previously. 33 Briefly, 1 μg of genomic DNA was denatured with NaOH and modified by sodium bisulfite. Samples were then purified using Wizard DNA purification resin (Promega Corp., Madison, WI), again treated with NaOH, precipitated with ethanol, and resuspended in water. Modified DNA was PCR-amplified under conditions described previously. 17 The maspin gene promoter was amplified from the bisulfite-modified DNA by two rounds of PCR using nested primers specific to the bisulfite-modified sequence of the maspin gene CpG island. The first round primers were: primer U2 (nucleotides −284 to −255), 5′-AAA AGA ATG GAG ATT AGA GTA TTT TTT GTG-3′; primer D2 (nucleotides 157 to 184), 5′-CCT AAA ATC ACA ATT ATC CTA AAA AAT A-3′. 17 The second round primers were: primer U3 (nucleotides −238 to −212) 5′-GAA ATT TGT AGT GTT ATT ATT ATT ATA-3′; primer D3 (nucleotides 107 to 133) 5′-AAA AAC ACA AAA ACC TAA ATA TAA AAA-3′. 17 Both rounds of PCR were performed under the same PCR conditions, with 1% of the first-round PCR product serving as the template in the second-round PCR. PCR amplification was performed under the following conditions: 94°C for 4 minutes followed by five cycles of 94°C for 1 minute, 56°C for 2 minutes, 72°C for 3 minutes, then 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 seconds, 56°C for 2 minutes, 72°C for 1.5 minutes, and ending with a final extension of 72°C for 6 minutes.

Subcloning and Sequencing

Amplified PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel. PCR products were purified with a QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen). The PCR fragments were ligated to pGEM-T Easy Vectors (Promega) and transformed into DH5α competent cells (Toyobo, Tokyo, Japan). Ten or 30 subcloned colonies were chosen randomly in GNE and cancer cell lines, or primary gastric cancers, respectively. Plasmid DNA was purified by a PI-200 DNA automatic isolation system (Kurabo, Osaka, Japan). Cycle sequencing used a primer of the T7 promoter and a BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing FS Ready Reaction Kit (Applied Biosystems; ABI, Foster City, CA). The product was analyzed with an ABI PRISM 3100 DNA Sequencer (ABI).

5-Aza-dC Treatment

Cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 105 cells/10-cm plate on day 1. Twenty-four hours later, 5-Aza-dC (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was added to a final concentration of 2 μmol/L or 10 μmol/L. Three days after 5-Aza-dC treatment, the cells were harvested for RQ-PCR and Western blotting.

Western Blotting

All gastric cancer cell lines were cultured to 70 to 80% confluence on a 10-cm Petri dish, added to 1 ml of cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and removed from the dishes by cell scraping. The cell suspension was centrifuged at 7500 rpm for 1 minute. After removal of the supernatant, the cell pellet was dissolved in 1.0% Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer [50 mmol/L HEPES (pH 7.5)/1 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid/150 mmol/L NaCl/2.5 mmol/L EGTA/1.0% Nonidet P-40] and rotated at 4°C for 30 minutes. Insoluble material was spun down (20 minutes, 14,000 rpm) and the clear supernatants were collected. The protein concentration of the lysates was measured using a Bio-Rad DC Protein Assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Cell lysates containing equal amounts of protein were mixed with 6× concentrated loading dye, heated for 4 minutes at 95°C, and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on a 10% polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad). The proteins were then transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK) by electroblotting. The membrane was washed twice in 0.05% Tween-20 PBS (2 × 10 minutes), then blocked by 5% blocking reagent (Amersham Biosciences) in 0.05% Tween-20 PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. The membrane was washed twice in 0.05% Tween-20 PBS (2 × 10 minutes). Primary monoclonal antibody for maspin (anti-human maspin antibody; Pharmingen International, San Diego, CA) was diluted 1:1000 in 0.05% Tween-20 PBS. The membrane was incubated for 1 hour at room temperature and washed as already described. For the second antibody, anti-mouse IgG (Amersham Biosciences) was diluted 1:10,000 in blocking buffer. The membrane was incubated for 45 minutes at room temperature and washed. Maspin protein was detected by ECL Plus (Amersham Biosciences).

RQ-PCR

For RQ-PCR assay, primers and a fluorogenic probe were designed with Primer Express software (ABI): maspin F (nucleotides 646 to 665; 5′-CGA CCA GAC CAA AAT CCT TG-3′), maspin R (nucleotides 778 to 796; 5′-GAA CGT GGC CTC CAT GTT C-3′), probe (nucleotides 745 to 772; 5′-FAM-CAA CAA GAC AGA CAC CAA ACC AGT GCA G-TAMURA-3′). For RQ-PCR assay, an ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detector (ABI) was used. The reaction mix contained 50 ng of cDNA, 200 nmol/L of each primer, 5 μmol/L of probe, and 25 μl of TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (ABI), in a final volume of 50 μl. The cDNA was subjected to 50 cycles of a two-step PCR consisting of a 15-second denaturation step at 95°C and a 1-minute combined annealing/extension step at 60°C. Plasmids were diluted in a precise series, ranging from 5 pg to 0.005 fg (2 × 106 to 2 copies). For normalization of each target in the samples, the copy number of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as an internal control. The normalized values of maspin mRNA were expressed as the ratio of maspin copy number per 103 copy number of GAPDH.

Immunohistochemical Staining

Four-μ slices were cut from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded samples and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Serial sections were stained immunohistochemically. Antigen was retrieved by incubating the microwave-based antigen retrieval method with 10 mmol/L of citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 15minutes. After deparaffinization and antigen recovery, the sections were washed three times in PBS (3 × 5 minutes) and immersed in 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 30 minutes to block the endogenous peroxidase activity. After three washes with PBS (3 × 5 minutes), the sections were incubated with 5% bovine serum albumin for 10 minutes to block nonspecific reactions. Then the sections were incubated with anti-human maspin antibody (dilution, 1:50), overnight at 4°C. Secondary antibody and peroxidase labeling were performed with a Simple Stain MAX-PO Kit (Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan), colorization was produced by diaminobenzidine substrate (DAKO), and counterstaining was performed with Mayer’s hematoxylin.

Results

Maspin Expression and Methylation Status in Gastric Cancer Cell Lines

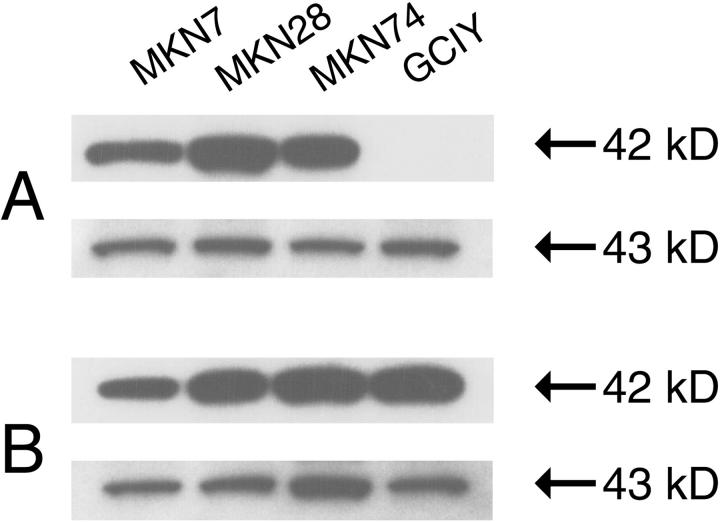

Three gastric cancer cell lines (MKN7, MKN28, and MKN74) strongly expressed maspin protein; only GCIY was undetectable (Figure 1A) ▶ . Maspin expression of GCIY was reactivated after treatment with the demethylating agent, 5-Aza-dC (2 μmol/L and 10 μmol/L; tumor cell viability did not differ between the two concentrations) (Figure 1B) ▶ . The same result for maspin mRNA was also confirmed in GCIY after treatment with 5-Aza-dC (Table 1) ▶ . These results indicated that maspin expression is regulated by epigenetic modification in gastric cancer cell lines; therefore, we evaluated the methylation status of the maspin gene promoter using the bisulfite genome-sequencing method.

Figure 1.

Western blot analyses of maspin expression before (A) and after (B) treatment with 5-Aza-dC (2 μmol/L) in gastric cancer cell lines. Equal loading was confirmed by incubation with an anti-actin antibody (C-2, Santa Cruz). A: Maspin protein expression was observed in three cancer cell lines. Only GCIY was undetectable. B: Reactivation of the maspin protein was observed in GCIY by the treatment with 5-Aza-dC.

Table 1.

Results of RQ-PCR Assay for Measuring Maspin mRNA in Gastric Cancer Cell Lines

| Cell line | Copy number of maspin mRNA/103 GAPDH | |

|---|---|---|

| 5-Aza-dC (−) | 5-Aza-dC (+) | |

| MKN7 | 40.2 | 50.0 |

| MKN28 | 7.80 | 11.8 |

| MKN74 | 9.00 | 5.70 |

| GCIY | 0 | 0.21 |

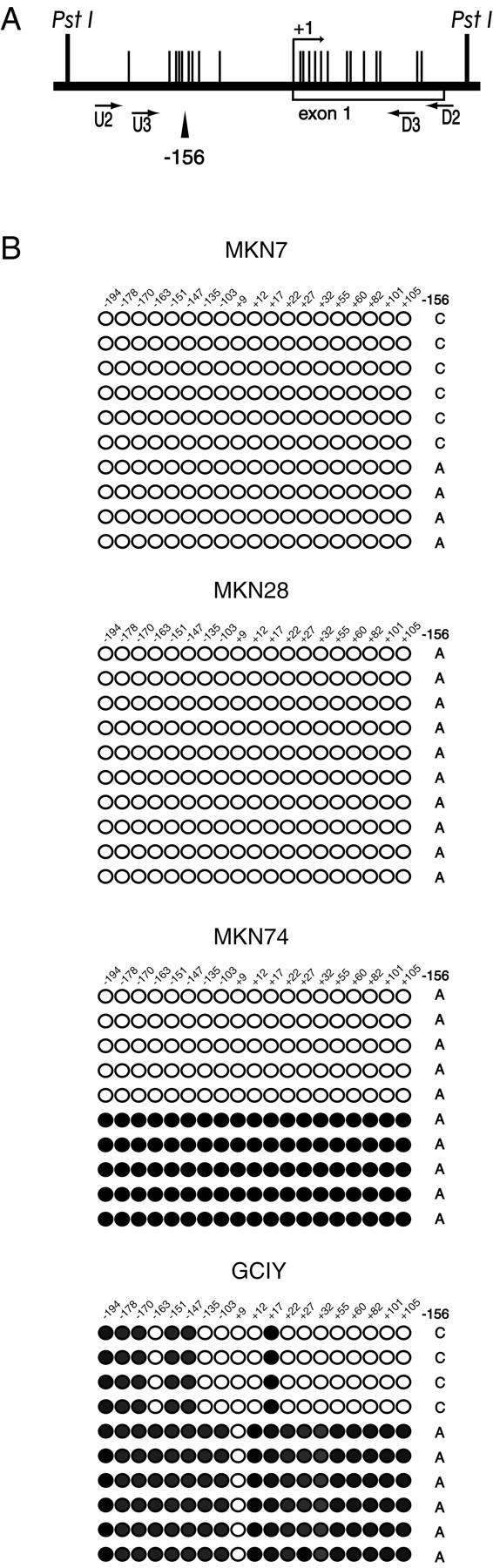

We found a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) site in the sequenced region (A/C at −156; the number indicates the location of the site with reference to the start site of the major transcription; Figure 2A ▶ ). We determined the allele-specific methylation status using SNP. The promoter region was completely unmethylated in both alleles in a maspin-positive cell line (MKN7) (Figure 2B) ▶ . All sequenced subclones of MKN28 were completely demethylated, but SNP revealed homozygosity. MKN74, a maspin-positive cell line, was methylated at 19 of 19 CpG sites in one-half of the clones (Figure 2B) ▶ . Unfortunately, the SNP revealed homozygosity, and we could not determine the allele-specific methylation status. However, one allele may be completely demethylated because one-half of the sequenced clones were completely demethylated (Figure 2B) ▶ . A maspin-negative cell line (GCIY) showed hypermethylation. One allele was methylated at 18 of 19 CpG sites, and another allele was methylated at six sites (Figure 2B) ▶ .

Figure 2.

Diagram of the maspin gene promoter region analyzed (A) and methylation status in four gastric cancer cell lines (B). A: The vertical lines mark the locations of CpG dinucleotide sites. The bent arrow indicates the transcription start site. The locations of nested PCR primers (U2/D2 and U3/D3) are indicated by arrows. SNP site (−156) is indicated by arrowhead. PstI indicates the position of the restriction site. B: Location and methylation status of 19 CpG sites in the maspin gene promoter. Each row of circles represents the methylation pattern obtained from individual clones of the maspin gene promoter. Each circle represents a CpG dinucleotide site. The filled circles are methylation-positive and the open circles are methylation-negative. The number at the top indicates the position of each CpG site from the major transcription start site. The allele status of each clone at the SNP site is indicated on the right.

Immunohistochemistry for Maspin Expression in Gastric Cancerous and Noncancerous Tissue Samples

The expression of maspin product was assessed immunohistochemically in 50 specimens obtained surgically from gastric cancer patients. Two sections in which the tumor cells infiltrated most deeply were stained in each case. Sections of GNE obtained from the corpus and pyloric parts of the stomach were also examined in each case.

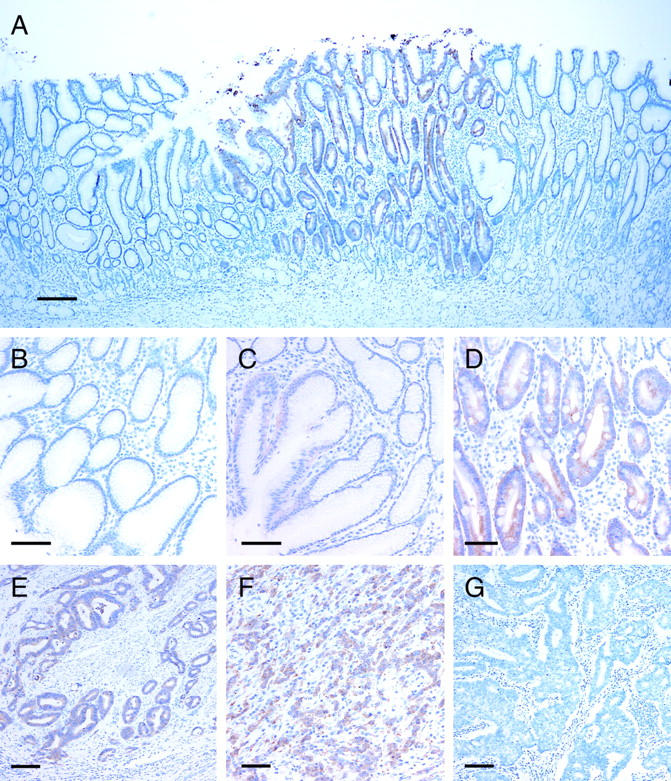

Maspin expression was observed in 40 (80%) of 50 tumor specimens (Table 2) ▶ . Their immunoreactivities were diffusely positive in 38 (95%) of 40 cases (Table 2 ▶ and Figure 3, E and F ▶ ), whereas the relative staining intensities varied. Subcellular localization of maspin protein was observed in the cytoplasm (Figure 3, E and F) ▶ . Cells with nuclear localization were extremely rare. There was no significant correlation between immunoreactivities of tumor cells and histological subtypes (Table 2) ▶ .

Table 2.

Immunohistochemistry for Maspin-Product in 50 Gastric Cancer Patients

| Histology | Number of cases | Maspin staining | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative (%) | Positive (%) | |||

| Focal | Diffuse | |||

| GNE without IM | 46 | 32 (69.5) | 14 (30.5) | 0 (0) |

| GNE with IM | 50 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 50 (100) |

| Gastric cancer | 50 | 10 (20.0) | 2 (4.0) | 38 (76.0) |

| Intestinal type | 38 | 7 (18.4) | 1 (2.6) | 30 (79.0) |

| Diffuse type | 12 | 3 (25.0) | 1 (8.3) | 8 (66.7) |

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemistry for maspin protein. A: A low-power view of a GNE. Immunoreactivity for maspin is observed in GNE with IM but not in GNE without IM. B–D: High-power views of GNE without (B and C) and with (D) IM. GNE without IM are almost negative (B) but focal and faint immunoreactivity is observed in the foveolar epithelia (C). Dense immunoreactivity is observed in GNE with IM (D). E–G: High-power views of gastric cancers. E: Maspin-positive intestinal-type gastric cancer. F: Maspin-positive diffuse-type gastric cancer. G: Maspin-negative intestinal-type gastric cancer. Scale bars: 200 μm (A); 50 μm (B–D); 100 μm (E–G).

All cases contained GNE with IM. Dense immunoreactivity was observed selectively in GNE with IM (Figure 3, A and D) ▶ . Forty-six cases (92%) of 50 had GNE without IM but those showed no diffuse and dense immunoreactivity (Figure 3, A and B) ▶ . Fourteen (30.5%) of the 46 patients showed focal and weak maspin expression in the foveolar epithelium (Figure 3C) ▶ . Subcellular localization in the epithelium with IM was confined to the cytoplasm (Figure 3D) ▶ .

Crypt Isolation and Maspin Analyses on Methylation Status and mRNA Expression

We studied the methylation status of the maspin gene promoter in more detail for 10 of 50 patients whose tissue was assessed immunohistochemically. For precise examination, we eliminated stromal cell contamination by isolating crypts. Crypts isolated from normal mucosa were stained with Alcian blue (pH 2.5) to distinguish those with IM from those without IM. Normal epithelia were obtained from the corpus and pylorus of the stomach. DNA was extracted from more than 200 crypts in each sample and prepared for the bisulfite genome-sequencing method.

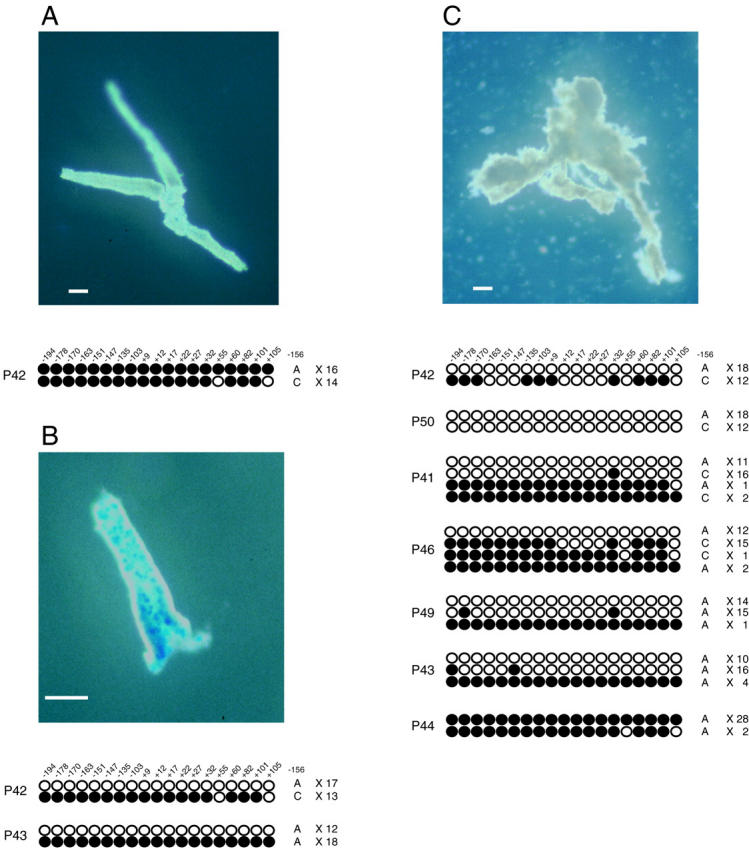

The results of the assessment of the methylation status of maspin gene promoter regions are shown in Figure 4 ▶ . In all patients, the maspin gene promoter region of GNE without IM was frequently methylated at almost all CpG sites, whereas those with IM were frequently demethylated (Figure 4, A and B) ▶ . Six of 10 patients exhibited heterozygosity at the SNP, and we determined the allele-specific methylation status in these patients. We found that methylation occurred in one allele at 17 to 19 CpG sites and that another allele was hypermethylated (Figure 4B ▶ , P42). Haploid demethylation might have occurred in the remaining four patients because one-half of the sequenced clones were completely methylated (Figure 4B ▶ , P43).

Figure 4.

Features of isolated crypts and methylation status of GNE without (A) and with (B) IM, and gastric cancer (C). A: The crypts are negative for Alcian blue staining. B: The goblet cells of IM are stained with Alcian blue. C: Irregularly shaped crypts with multiple branching are observed in cancerous crypts. A–C: Location and methylation status of 19 CpG sites in the maspin gene promoter. Each row of circles represents the methylation pattern obtained from individual clones of the maspin gene promoter. Each circle represents a CpG dinucleotide site. The filled circles are methylation-positive and the open circles are methylation-negative. The number at the top indicates the position of each CpG site from the major transcription start site. The allele status of each clone at the SNP site and number of clones exhibiting each methylation status are indicated on the right. Scale bars, 100 μm.

We failed to isolate cancerous crypts in 3 of 10 examined patients because they had diffuse-type gastric cancer. Demethylation frequently occurred in six of seven gastric cancers (Figure 4C ▶ ; P42, P50, P41, P46, P49, and P43), but the remaining one exhibited hypermethylation (Figure 4C ▶ , P44), and we confirmed negative immunoreactivity for maspin protein in that patient (Figure 2G) ▶ . We were able to determine the allele-specific methylation status in four of six patients using the SNP site (Figure 4C ▶ ; P42, P50, P41, and P46) both alleles were frequently demethylated in three of the four patients (Figure 4C ▶ ; P42, P50, and P41). One patient (P46) exhibited frequent demethylation on one allele, although another allele was methylated at 13 of 19 CpG sites. The other two patients were homozygous but approximately one-half of the sequenced clones showed demethylation (Figure 4C ▶ , P49 and P43). Small numbers of clones exhibiting different methylation patterns from major subclones (Figure 4C ▶ ; P41, P43, P46, and P49) were identified in the cancerous crypts. These clones revealed hypermethylation; therefore, they might have been amplified from contaminating stromal cells.

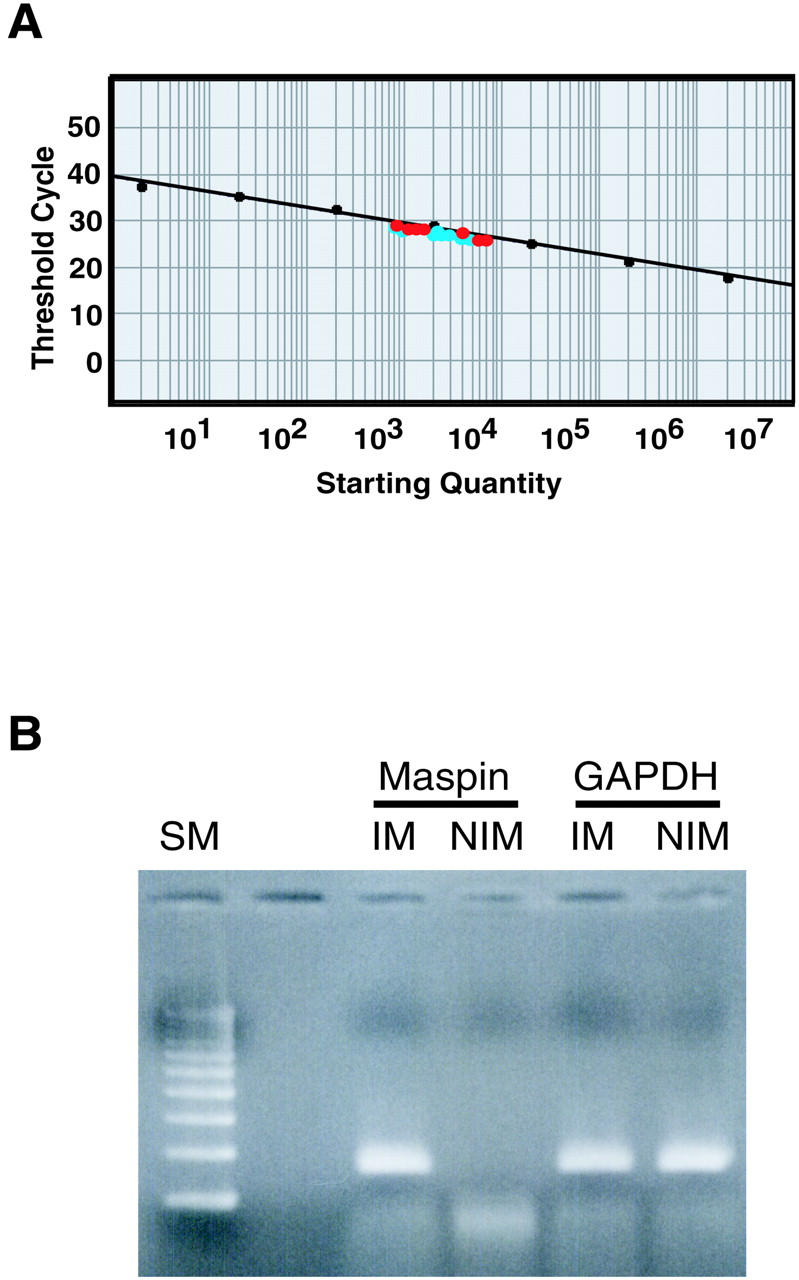

We examined maspin mRNA expression in cancerous and noncancerous crypts using RQ-PCR, and we were able to amplify maspin mRNA from GNE with IM and cancerous crypts but not from GNE without IM (Figure 5) ▶ . The quantitative results of maspin mRNA did not differ between normal epithelium with IM and cancerous crypts (Table 3 ▶ and Figure 5 ▶ ).

Figure 5.

Results of real-time quantitative PCR (A) and agarose gel electrophoresis (B) for maspin mRNA expression. A: A standard curve for the RQ-PCR. The red dots are quantitative results for 7 gastric cancers and the blue dots are those for 10 GNE with IM. B: PCR products are detectable in GNE with IM (IM) but not in GNE without IM (NIM). SM, size marker.

Table 3.

Results of RQ-PCR Assay for Measuring Maspin mRNA in GNE and Cancers

| Samples | Number of cases | Copy number of maspin mRNA/103 GAPDH* |

|---|---|---|

| GNE without IM | 10 | 0 |

| GNE with IM | 10 | 12.2 ± 12.5 |

| Gastric cancer | 7 | 13.9 ± 14.4 |

*Values indicate mean ± standard deviation.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that maspin protein production was high in gastric cancer cells as well as GNE with IM, but not in GNE without IM. The mechanism of regulation of maspin expression primarily depended on epigenetic modification in normal gastric cells and gastric cancer cells. Our allele-specific methylation analyses showed that demethylation on the haploid allele was sufficient to produce abundant maspin protein in vitro and in vivo. Moreover, the extent of demethylation of the maspin gene promoter was greater in gastric cancers. These data suggest that demethylation at the maspin gene promoter region disrupts the cell-type-specific gene repression of the establishment and/or maintenance of differentiated GNE and gastric cancer.

The aberrant expression of maspin protein in precancerous lesions has been described for the pancreas and ovary, 14,15 but the methylation status of the lesions has not been examined. Overexpression of maspin protein frequently occurred in both types of cancer cells, and lack of immunoreactivity was confirmed in the corresponding normal cells. 14,15 This immunophenotype analogous to that observed in the present study led us to propose the following explanation for the paradoxical expression of maspin among cancers. Maspin plays an important role in the establishment and/or maintenance in a cell-specific manner (breast and prostate). 17 In tumors arising from these organs, maspin had tumor-suppressive activity, such as inhibition of cell motility, invasion, and metastasis. 2-7 Unlike the situation in these tumors, maspin is expressed aberrantly in pancreatic and ovarian cancers as well as in gastric cancers. In these tissues, maspin is usually repressed in a cell-type-restricted manner. The maspin gene will be expressed aberrantly when differentiated normal epithelial cells transform to metaplastic or dysplastic cells. Tumor cells derived from these tissues were disrupted in a cell-type-restricted manner. Our present in vivo study is the first to have demonstrated that demethylation at the maspin gene promoter may play an important role in disruption of the maspin regulation mechanism and contribute to transformation from normal differentiated cells to metaplastic cells.

The functional significance of aberrant maspin expression in IM and gastric cancer cells has remained unclear. Although some morphological and genetic studies have suggested the precancerous nature of IM, 35-43 this issue remains controversial. We examined maspin expression in the gastric epithelia of autopsied patients without gastric cancer immunohistochemically, and demonstrated that most cases of IM strongly expressed maspin protein (data not shown). Our study did not suggest that the aberrant expression of maspin was related directly to tumor development. However, the high incidence of aberrant maspin expression in gastric cancers suggests that most gastric cancers arise from GNE with IM. Our observations are consistent with those from the immunohistochemical study by Son and colleagues. 16

Targeted overexpression of maspin in mice disrupts mammary gland development and inhibits the development of lobular-alveolar structures during pregnancy. 44 Architectural and differential abnormalities can occur in gastric mucosa, and these abnormalities may facilitate the development of gastric cancer. Recent epigenetic studies have examined tumor-related genes and also suggested that silencing of the genes because of hypermethylation at CpG islands tended to be accumulated along the multistep pathway of gastric carcinogenesis from IM to gastric cancer. 20-22 Only a few studies have examined the relationship between aberrant hypomethylation and overexpression of specific genes in other types of carcinoma. 45,46 In gastric cancer, there has been no report concerning aberrant expression because of hypomethylation at its CpG sites. Further functional studies are needed to clarify the contribution of inappropriate maspin expression to gastric carcinogenesis. The loss of control of epigenetic changes may be related to the formation of IM and/or cancers of the stomach.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Shin-ichi Nakamura and Dr. Yu-Fei Jiao, Division of Pathology, Central Clinical Laboratory, Iwate Medical University School of Medicine, for explaining the crypt isolation technique.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Chihaya Maesawa, Department of Pathology, Iwate Medical University School of Medicine, Uchimaru 19-1, Morioka, Japan. E-mail: chihaya@iwate-med.ac.jp.

Supported by the Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture, Japan (grants-in-aid 13671332, 14571221, and 14570156).

References

- 1.Zou Z, Anisowicz A, Hendrix MJ, Thor A, Neveu M, Sheng S, Rafidi K, Seftor E, Sager R: Maspin, a serpin with tumor-suppressing activity in human mammary epithelial cells. Science 1994, 263:526-529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sheng S, Pemberton PA, Sager R: Production, purification, and characterization of recombinant maspin proteins. J Biol Chem 1994, 269:30988-30993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheng S, Carey J, Seftor EA, Dias L, Hendrix MJ, Sager R: Maspin acts at the cell membrane to inhibit invasion and motility of mammary and prostatic cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996, 93:11669-11674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheng S, Truong B, Fredrickson D, Wu R, Pardee AB, Sager R: Tissue-type plasminogen activator is a target of the tumor suppressor gene maspin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998, 95:499-504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGowen R, Biliran H, Jr, Sager R, Sheng S: The surface of prostate carcinoma DU145 cells mediates the inhibition of urokinase-type plasminogen activator by maspin. Cancer Res 2000, 60:4771-4778 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biliran H, Jr, Sheng S: Pleiotrophic inhibition of pericellular urokinase-type plasminogen activator system by endogenous tumor suppressive maspin. Cancer Res 2001, 61:8676-8682 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi HY, Zhang W, Liang R, Abraham S, Kittrell FS, Medina D, Zhang M: Blocking tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis by maspin in a syngeneic breast cancer model. Cancer Res 2001, 61:6945-6951 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Umekita Y, Ohi Y, Sagara Y, Yoshida H: Expression of maspin predicts poor prognosis in breast-cancer patients. Int J Cancer 2002, 100:452-455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maass N, Hojo T, Rosel F, Ikeda T, Jonat W, Nagasaki K: Down regulation of the tumor suppressor gene maspin in breast carcinoma is associated with a higher risk of distant metastasis. Clin Biochem 2001, 34:303-307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Machtens S, Serth J, Bokemeyer C, Bathke W, Minssen A, Kollmannsberger C, Hartmann J, Knuchel R, Kondo M, Jonas U, Kuczyk M: Expression of the p53 and Maspin protein in primary prostate cancer: correlation with clinical features. Int J Cancer 2001, 95:337-342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xia W, Lau YK, Hu MC, Li L, Johnston DA, Sheng S, El-Naggar A, Hung MC: High tumoral maspin expression is associated with improved survival of patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncogene 2000, 19:2398-2403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zou Z, Gao C, Nagaich AK, Connell T, Saito S, Moul JW, Seth P, Appella E, Srivastava S: p53 regulates the expression of the tumor suppressor gene maspin. J Biol Chem 2000, 275:6051-6054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang M, Volpert O, Shi YH, Bouck N: Maspin is an angiogenesis inhibitor. Nat Med 2000, 6:196-199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maass N, Hojo T, Ueding M, Luttges J, Kloppel G, Jonat W, Nagasaki K: Expression of the tumor suppressor gene Maspin in human pancreatic cancers. Clin Cancer Res 2001, 7:812-817 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sood AK, Fletcher MS, Gruman LM, Coffin JE, Jabbari S, Khalkhali-Ellis Z, Arbour N, Seftor EA, Hendrix MJ: The paradoxical expression of maspin in ovarian carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2002, 8:2924-2932 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Son HJ, Sohn TS, Song SY, Lee JH, Rhee JC: Maspin expression in human gastric adenocarcinoma. Pathol Int 2002, 52:508-513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Futscher BW, Oshiro MM, Wozniak RJ, Holtan N, Hanigan CL, Duan H, Domann FE: Role for DNA methylation in the control of cell type specific maspin expression. Nat Genet 2002, 31:175-179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Costello JF, Vertino PM: Methylation matters: a new spin on maspin. Nat Genet 2002, 31:123-124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Domann FE, Rice JC, Hendrix MJ, Futscher BW: Epigenetic silencing of maspin gene expression in human breast cancers. Int J Cancer 2000, 85:805-810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang GH, Shim YH, Jung HY, Kim WH, Ro JY, Rhyu MG: CpG island methylation in premalignant stages of gastric carcinoma. Cancer Res 2001, 61:2847-2851 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.To KF, Leung WK, Lee TL, Yu J, Tong JH, Chan MW, Ng EK, Chung SC, Sung JJ: Promoter hypermethylation of tumor-related genes in gastric intestinal metaplasia of patients with and without gastric cancer. Int J Cancer 2002, 102:623-628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waki T, Tamura G, Tsuchiya T, Sato K, Nishizuka S, Motoyama T: Promoter methylation status of E-cadherin, hMLH1, and p16 genes in nonneoplastic gastric epithelia. Am J Pathol 2002, 161:399-403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leung SY, Yuen ST, Chung LP, Chu KM, Chan AS, Ho JC: hMLH1 promoter methylation and lack of hMLH1 expression in sporadic gastric carcinomas with high-frequency microsatellite instability. Cancer Res 1999, 59:159-164 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suzuki H, Itoh F, Toyota M, Kikuchi T, Kakiuchi H, Hinoda Y, Imai K: Distinct methylation pattern and microsatellite instability in sporadic gastric cancer. Int J Cancer 1999, 83:309-313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toyota M, Ahuja N, Suzuki H, Itoh F, Ohe-Toyota M, Imai K, Baylin SB, Issa JP: Aberrant methylation in gastric cancer associated with the CpG island methylator phenotype. Cancer Res 1999, 59:5438-5442 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iida S, Akiyama Y, Nakajima T, Ichikawa W, Nihei Z, Sugihara K, Yuasa Y: Alterations and hypermethylation of the p14(ARF) gene in gastric cancer. Int J Cancer 2000, 87:654-658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shim YH, Kang GH, Ro JY: Correlation of p16 hypermethylation with p16 protein loss in sporadic gastric carcinomas. Lab Invest 2000, 80:689-695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamura G, Yin J, Wang S, Fleisher AS, Zou T, Abraham JM, Kong D, Smolinski KN, Wilson KT, James SP, Silverberg SG, Nishizuka S, Terashima M, Motoyama T, Meltzer SJ: E-Cadherin gene promoter hypermethylation in primary human gastric carcinomas. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000, 92:569-573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Byun DS, Lee MG, Chae KS, Ryu BG, Chi SG: Frequent epigenetic inactivation of RASSF1A by aberrant promoter hypermethylation in human gastric adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res 2001, 61:7034-7038 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leung WK, Yu J, Ng EK, To KF, Ma PK, Lee TL, Go MY, Chung SC, Sung JJ: Concurrent hypermethylation of multiple tumor-related genes in gastric carcinoma and adjacent normal tissues. Cancer 2001, 91:2294-2301 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakamura S, Goto J, Kitayama M, Kino I: Application of the crypt-isolation technique to flow-cytometric analysis of DNA content in colorectal neoplasms. Gastroenterology 1994, 106:100-107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakamura S, Kino I, Baba S: Nuclear DNA content of isolated crypts of background colonic mucosa from patients with familial adenomatous polyposis and sporadic colorectal cancer. Gut 1993, 34:1240-1244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clark SJ, Harrison J, Paul CL, Frommer M: High sensitivity mapping of methylated cytosines. Nucleic Acids Res 1994, 22:2990-2997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang M, Maass N, Magit D, Sager R: Transactivation through Ets and Ap1 transcription sites determines the expression of the tumor-suppressing gene maspin. Cell Growth Differ 1997, 8:179-186 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Correa P: Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process—First American Cancer Society Award Lecture on Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. Cancer Res 1992, 52:6735-6740 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Filipe MI, Munoz N, Matko I, Kato I, Pompe-Kirn V, Jutersek A, Teuchmann S, Benz M, Prijon T: Intestinal metaplasia types and the risk of gastric cancer: a cohort study in Slovenia. Int J Cancer 1994, 57:324-329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shiao YH, Rugge M, Correa P, Lehmann HP, Scheer WD: p53 alteration in gastric precancerous lesions. Am J Pathol 1994, 144:511-517 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu MS, Shun CT, Lee WC, Chen CJ, Wang HP, Lee WJ, Sheu JC, Lin JT: Overexpression of p53 in different subtypes of intestinal metaplasia and gastric cancer. Br J Cancer 1998, 78:971-973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Filipe MI, Osborn M, Linehan J, Sanidas E, Brito MJ, Jankowski J: Expression of transforming growth factor alpha, epidermal growth factor receptor and epidermal growth factor in precursor lesions to gastric carcinoma. Br J Cancer 1995, 71:30-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leung WK, Kim JJ, Kim JG, Graham DY, Sepulveda AR: Microsatellite instability in gastric intestinal metaplasia in patients with and without gastric cancer. Am J Pathol 2000, 156:537-543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hamamoto T, Yokozaki H, Semba S, Yasui W, Yunotani S, Miyazaki K, Tahara E: Altered microsatellites in incomplete-type intestinal metaplasia adjacent to primary gastric cancers. J Clin Pathol 1997, 50:841-846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sung JJ, Leung WK, Go MY, To KF, Cheng AS, Ng EK, Chan FK: Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in Helicobacter pylori-associated premalignant and malignant gastric lesions. Am J Pathol 2000, 157:729-735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Rees BP, Saukkonen K, Ristimaki A, Polkowski W, Tytgat GN, Drillenburg P, Offerhaus GJ: Cyclooxygenase-2 expression during carcinogenesis in the human stomach. J Pathol 2002, 196:171-179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang M, Magit D, Botteri F, Shi HY, He K, Li M, Furth P, Sager R: Maspin plays an important role in mammary gland development. Dev Biol 1999, 215:278-287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosty C, Ueki T, Argani P, Jansen M, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Hruban RH, Goggins M: Overexpression of S100A4 in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas is associated with poor differentiation and DNA hypomethylation. Am J Pathol 2002, 160:45-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cho M, Uemura H, Kim SC, Kawada Y, Yoshida K, Hirao Y, Konishi N, Saga S, Yoshikawa K: Hypomethylation of the MN/CA9 promoter and upregulated MN/CA9 expression in human renal cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer 2001, 85:563-567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]