Abstract

We sought to evaluate the extent of the contribution of transposable elements (TEs) to human microRNA (miRNA) genes along with the evolutionary dynamics of TE-derived human miRNAs. We found 55 experimentally characterized human miRNA genes that are derived from TEs, and these TE-derived miRNAs have the potential to regulate thousands of human genes. Sequence comparisons revealed that TE-derived human miRNAs are less conserved, on average, than non-TE-derived miRNAs. However, there are 18 TE-derived miRNAs that are relatively conserved, and 14 of these are related to the ancient L2 and MIR families. Comparison of miRNA vs. mRNA expression patterns for TE-derived miRNAs and their putative target genes showed numerous cases of anti-correlated expression that are consistent with regulation via mRNA degradation. In addition to the known human miRNAs that we show to be derived from TE sequences, we predict an additional 85 novel TE-derived miRNA genes. TE sequences are typically disregarded in genomic surveys for miRNA genes and target sites; this is a mistake. Our results indicate that TEs provide a natural mechanism for the origination miRNAs that can contribute to regulatory divergence between species as well as a rich source for the discovery of as yet unknown miRNA genes.

MICRORNAS (miRNAs) are small, ∼22-nt-long, noncoding RNAs that regulate gene expression (Ambros 2004). In animals, miRNA genes are transcribed into primary miRNAs (pri-miRNAs) and processed by Drosha to yield ∼70- to 90-nt pre-miRNA transcripts that form hairpin structures. Mature miRNAs are liberated from these longer hairpin structures by the RNase III enzyme Dicer (Bartel 2004). Drosha acts in the nucleus, cleaving the pri-miRNA near the base of the hairpin stem to yield the pre-miRNA sequence. The pre-miRNA is then exported to the cytoplasm where the stem is cleaved by Dicer to produce a miRNA duplex. One strand of this duplex is rapidly degraded and only the mature ∼22-nt miRNA sequence remains. The mature miRNA associates with the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), and together the miRNA–RISC targets mRNAs for regulation. miRNA target specificity is determined by partial complementarity with the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) sequence of the mRNA, and regulation is achieved by translational repression and/or mRNA degradation. miRNAs have been implicated in a variety of functions, including developmental timing (Lee et al. 1993; Reinhart et al. 2000), apoptosis (Brennecke et al. 2003), and hematopoetic differentiation (Chen et al. 2004).

miRNAs were first discovered in Caenorhabditis elegans through genetic analysis of developmental mutants (Lee et al. 1993). The small RNA product of the lin-4 gene was found to negatively regulate lin-14 expression via interaction with a complementary region in the lin-14 3′-UTR. This system appeared to be unique until a second example of a similar small regulatory RNA in C. elegans, let-7, was discovered 7 years later (Reinhart et al. 2000). Shortly thereafter, let-7 homologs and transcripts were detected among a phylogenetically diverse set of animals (Pasquinelli et al. 2000). The realization that miRNAs represent a distinct, coherent, and abundant class of regulatory genes was finally crystallized in 2001 with the publication of three back-to-back articles in Science, reporting the discovery of numerous novel miRNA genes (Lagos-Quintana et al. 2001; Lau et al. 2001; Lee and Ambros 2001). These articles introduced the term miRNA to refer to all small RNAs with similar genomic features but unknown functions, and miRNAs have now been found in all metazoans surveyed for their presence (Bartel 2004).

Given their relatively recent discovery and characterization, a number of open questions concerning the function and evolution of miRNAs remain. In particular, the evolutionary origins of miRNAs are not well appreciated. For instance, many miRNA genes were found to be evolutionarily conserved and this was thought to be a general characteristic of miRNAs. However, a number of nonconserved miRNAs have been recently discovered (Bentwich et al. 2005). The extent to which miRNA genes evolve as paralogous gene families is also unknown. Even the upper bound on the number of miRNA genes encoded by any given genome is not known (Berezikov et al. 2006), and the number of new entries in the miRBase registry of miRNA genes continues to grow steadily (Griffiths-Jones et al. 2006).

We sought to evaluate the contribution of transposable elements (TEs) to the origin and evolution of human miRNA genes. Another class of regulatory RNAs, small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), are known to be related to TEs. Interestingly, this has been pointed out as a distinction between miRNAs and siRNAs, which are closely related in terms of structure, function, and biogenesis. As opposed to siRNAs, miRNAs were thought to derive from loci distinct from other genes or TEs (Bartel 2004). However, several examples of miRNA genes that are derived from TEs have been recently identified (Smalheiser and Torvik 2005; Borchert et al. 2006; Piriyapongsa and Jordan 2007). We wanted to look at this phenomenon more closely to identify the full extent of human miRNA genes that are related to TEs and to characterize how these genes evolve as well as their regulatory and functional potential.

TEs have several characteristics that make them interesting candidates for donating miRNA sequences. First of all, TEs are ubiquitous and abundant genomic sequences. Thus, they could provide for the emergence of paralogous miRNA gene families as well as multiple target sites dispersed throughout the genome. Since TEs tend to be among the most rapidly evolving of all genomic sequences, they may also provide a mechanism for the emergence of lineage-specific miRNA genes that could exert diversifying regulatory effects. Finally, the full contribution of TEs to miRNA sequences is likely to be underestimated due to ascertainment biases. This is because computational methods aimed at the detection of novel miRNAs tend to purposefully exclude TE sequences (Bentwich et al. 2005; Lindow and Krogh 2005; Nam et al. 2005; Li et al. 2006). This is often done for reasons of tractability, but also reflects the widely held notion that TEs are genomic parasites that do not play any functional role for their host species (Doolittle and Sapienza 1980; Orgel and Crick 1980). However, many studies have identified a variety ways in which TEs have been domesticated (Miller et al. 1992) to provide functions to their hosts (Kidwell and Lisch 2001). These cases include the donation of coding sequences (Volff 2006) as well as numerous instances of TE-derived regulatory sequences (Britten 1996; Jordan et al. 2003; van de Lagemaat et al. 2003).

To evaluate the contribution of TEs to human miRNAs, we compared the genomic locations of TEs to the locations of experimentally validated human miRNA sequences reported in the miRBase database (Griffiths-Jones et al. 2006). The evolutionary dynamics of TE-related miRNAs were evaluated by within- and between-genome sequence comparisons. The potential regulatory and functional significance of TE-derived miRNAs was explored by combining information on miRNA target-site prediction, expression data for miRNA–mRNA pairs, and gene functional annotations. We also sought to discover putative cases of novel TE-derived miRNA genes in the human genome through ab initio prediction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Detection:

Human miRNA sequences and predicted target sites were taken from version 8.2 of the miRBase database (Griffiths-Jones et al. 2006). These data do not include ab initio miRNA gene predictions. The UCSC Genome Browser (Kent et al. 2002) and Table Browser (Karolchik et al. 2004) tools were used to search for miRNA genes colocated with TEs and to compare the evolutionary rates of miRNA genes. Human miRNA sequences were mapped to the hg18 (NCBI build 36.1) version of the human genome sequence and a generic feature format “custom track” was created (available upon request). Genomic locations of the miRNAs were compared to the locations of TEs annotated with the RepeatMasker program (Smit et al. 1996–2004). For this purpose, precomputed RepeatMasker annotations of hg18 were combined with RepeatMasker-determined genomic locations of a set of 96 “conserved” TE families recently added to Repbase (Jurka et al. 2005). These conserved consensus sequences correspond to low-copy-number TEs that show anomalously low levels of between-genome orthologous sequence divergence and can be found by searching Repbase (http://www.girinst.org/) with the keyword “conserved.”

Sequences of TE-derived miRNAs were compared to the human genome sequence using BLAT (Kent 2002). The criteria used for genome sequence hits were (1) ≥80% sequence identity with the query miRNA sequence and (2) the genomic hit region must be ≥80% and ≤120% of the length of the miRNA query sequence. The latter requirement was used to ensure that long genomic insertions were not identified as putative paralogous miRNAs.

Evolution:

Comparative genomic sequence data from the UCSC Genome Browser were used to analyze the relative evolutionary rates of human miRNAs. Evolutionary rates were derived from multiple whole-genome sequence alignments between the human and 16 other vertebrate genomes (Kent et al. 2003; Blanchette et al. 2004). Human miRNA evolutionary rates were calculated in two ways: (1) by evaluating the number of conserved sites per miRNA and (2) by evaluating the per-site conservation scores of miRNA sequences. Conserved human genome sites were predicted by the phastCons program, which uses a phylogenetic hidden Markov model to calculate the probabilities of sites being either conserved or nonconserved (Siepel et al. 2005). Conservation scores for human genome sites were also taken from the phastCons analysis of the vertebrate multiple genome sequence alignment, and these scores correspond to the posterior probability that a site is conserved or nonconserved.

Regulation and function:

Human miRNA target-site predictions were taken from miRBase, which uses a modified protocol based on the miRanda algorithm (Enright et al. 2003). The locations of target-site sequences in the human genome were compared to the RepeatMasker-based TE annotations. Expression levels for human miRNAs across five tissues (thymus, brain, liver, placenta, and testis) were taken from an oligonucleotide-based microarray study (Barad et al. 2004). Human mRNA expression levels from corresponding mRNA targets were taken from the Novartis Symatlas data set (Su et al. 2004). Corresponding miRNA and mRNA expression profiles were normalized using standard z-score transformation with the program Spotfire (http://www.spotfire.com) and compared using the Pearson correlation coefficient. Gene expression data were visualized using the Genesis program (Sturn et al. 2002).

Gene ontology (GO) analysis (Ashburner et al. 2000) was done using the GO Tree Machine program (Zhang et al. 2004). GO Tree Machine was used to identify significantly overrepresented biological process GO terms from a set of genes predicted to be regulated by a particular miRNA and to plot the location of these GO terms along the GO-directed acyclic graph.

TE–miRNA prediction:

TE locations in the human genome were considered together with the output of the program EvoFold, which combines RNA secondary structure prediction with the evaluation of multiple sequence alignments to identify conserved secondary structures (Pedersen et al. 2006). TE sequences that encode conserved hairpin structures with length ≥55 bp, a single terminal loop ≤20bp, and at least six paired bases in the stem region (Bentwich et al. 2005) were chosen for further analysis. For conserved TE-encoded hairpins of <55 bp that met all other criteria, the predicted secondary structure sequences were extended manually and rechecked for the ability to form hairpin structures using the program RNAfold from the Vienna RNA package (Hofacker et al. 1994). Sequences that were able to encode hairpins ≥55 bp after manual extension were chosen for further analysis. The potential for putative TE-derived miRNAs identified in this way to be expressed was evaluated using EST and mRNA data. Our TE–miRNA prediction protocol is represented in supplemental Figure 1 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/.

RESULTS

Transposable-element-derived miRNAs:

miRBase is an online database of miRNA gene sequences and predicted target sites (Griffiths-Jones et al. 2006); version 8.2 of miRBase contained 462 human miRNA gene sequences. Of these human miRNA genes, 379 are defined on the basis of experimental information, cloning of mature miRNA sequences for the most part, while 83 are predictions on the basis of sequence similarity with miRNAs that have been experimentally characterized in related species. We mapped these human miRNA genes to the complete genome sequence and compared their locations to the locations of annotated TEs. A total of 68 human miRNA genes share sequences with TEs, and all but 7 of these correspond to miRNAs experimentally characterized from human samples. The absence of ab initio miRNA gene predictions in the miRBase data set ensures that we are uncovering bona fide TE–miRNA relationships. Of these TE-related miRNAs, 49 are found in intron sequences while 19 are intergenic.

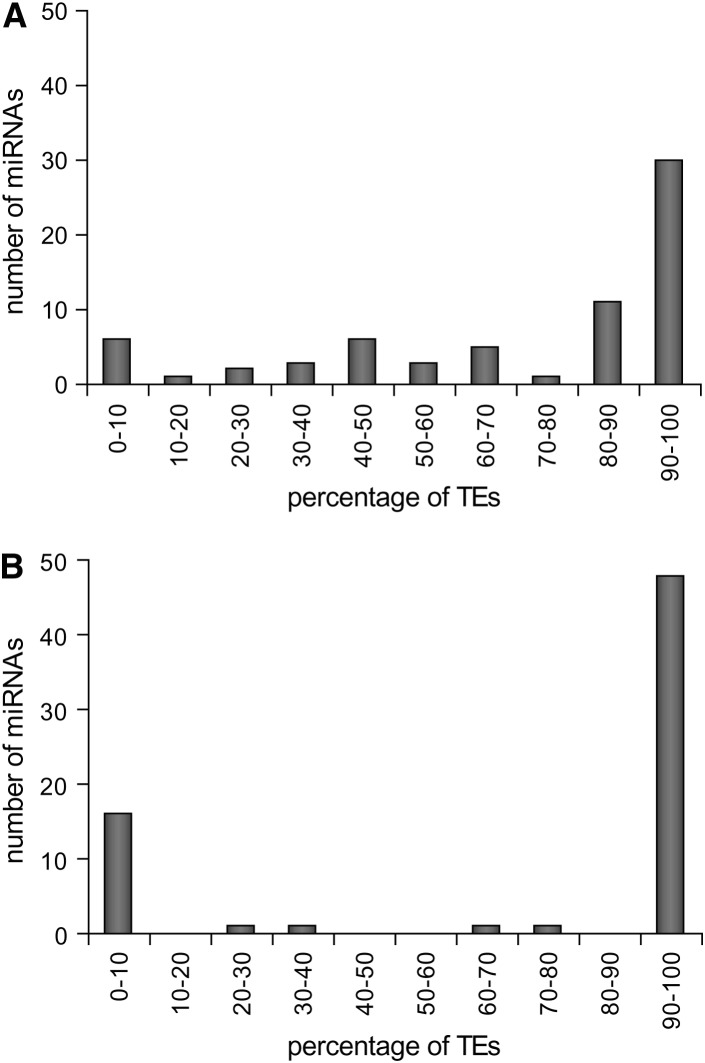

TE-related miRNAs differ in terms of the extent of overlap with TE sequences and the number of distinct TE sequences from which they are derived. For each individual TE-related human miRNA, a schematic in supplemental Figure 2 (at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/) illustrates the identity of all colocated TE sequences along with the extent and position of the TE–miRNA overlap and the relationship between the strand-specific orientation of the TE and the miRNA. The majority (50 of 68) of TE-related miRNAs consist of >50% TE-derived positions (Figure 1A), and this figure is likely to be an underestimate since many TE sequences are known to have diverged beyond the ability to be recognized by the RepeatMasker annotation software. The TE–miRNA overlap distribution for the region of the miRNA gene that corresponds to the processed (mature) regulatory sequence is even more bimodal (Figure 1B); 47 sequences have >95% of mature miRNA positions covered by TE sequence. Nevertheless, there are a handful (7 of 68) of TE-related miRNA genes that have <20% of their sequences colocated with TE sequence. These may represent spurious cases of TE–miRNA overlap. Visual inspection of the TE–miRNA alignments (supplemental Figure 2 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/) was used to eliminate these unreliable cases. Only the 55 cases with at least 50% TE coverage of the pre-miRNA sequence and/or 100% TE coverage of the mature miRNA sequence were considered as actual TE-derived miRNAs and used for further analysis (Table 1). These 55 TE-derived miRNAs represent ∼12% (55/462) of all human miRNAs reported in miRBase version 8.2.

Figure 1.—

Percentage of TE-derived residues in miRNA genes. Frequency distributions are shown for the percentages of TE-derived residues relative to miRNA gene sequences (A) and mature miRNA sequences (B).

TABLE 1.

TE-derived human miRNAs

| miRNA name (from miRBase) | miRBase accession no. | Coordinatesa | Colocated TE | Overlapb | Average conservation score | Targetsc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hsa-mir-130b | MI0000748 | Chromosome 22: 20337593–20337674(+) | MIRm | 65.85 | 0.8492 | 865 (10.75) |

| hsa-mir-151 | MI0000809 | Chromosome 8: 141811845–141811934(−) | L2 | 100.00 | 0.9317 | 863 (12.28) |

| hsa-mir-28 | MI0000086 | Chromosome 3: 189889263–189889348(+) | L2 | 93.02 | 0.9979 | 1136 (10.21) |

| hsa-mir-325 | MI0000824 | Chromosome X: 76142220–76142317(−) | L2 | 89.80 | 0.9905 | 751 (13.32) |

| hsa-mir-330 | MI0000803 | Chromosome 19: 50834092–50834185(−) | MIRm | 53.19 | 0.9867 | 927 (5.18) |

| hsa-mir-345 | MI0000825 | Chromosome 14: 99843949–99844046(+) | MIR | 39.80 | 0.8265 | 895 (7.82) |

| hsa-mir-361 | MI0000760 | Chromosome X: 85045297–85045368(−) | MER5A | 81.94 | 0.9998 | 882 (14.51) |

| hsa-mir-370 | MI0000778 | Chromosome 14: 100447229–100447303(+) | MIRm | 100.00 | 0.9893 | 1006 (4.77) |

| hsa-mir-374 | MI0000782 | Chromosome X: 73423846–73423917(−) | L2 | 54.17 | 0.9970 | 773 (7.50) |

| hsa-mir-378 | MI0000786 | Chromosome 5: 149092581–149092646(+) | MIRb | 90.91 | 1.0000 | 0 (0) |

| hsa-mir-421 | MI0003685 | Chromosome X: 73354937–73355021(−) | L2 | 89.41 | 0.9999 | 1023 (14.47) |

| hsa-mir-422a | MI0001444 | Chromosome 15: 61950182–61950271(−) | MIR3 | 100.00 | 0.0018 | 940 (7.34) |

| hsa-mir-493 | MI0003132 | Chromosome 14: 100405150–100405238(+) | L2 | 66.29 | 0.9990 | 0 (0) |

| hsa-mir-513-1 | MI0003191 | Chromosome X: 146102673–146102801(−) | MER91C | 100.00 | 0.0543 | 1065 (7.14) |

| hsa-mir-513-2 | MI0003192 | Chromosome X: 146115036–146115162(−) | MER91C | 100.00 | 0.0003 | 1065 (7.14) |

| hsa-mir-544 | MI0003515 | Chromosome 14: 100584748–100584838(+) | MER5A1 | 100.00 | 0.9337 | 1056 (10.42) |

| hsa-mir-545 | MI0003516 | Chromosome X: 73423664–73423769(−) | L2 | 82.08 | 0.9958 | 1065 (16.345) |

| hsa-mir-548a-1 | MI0003593 | Chromosome 6: 18679994–18680090(+) | MADE1 | 78.35 | 0.0391 | 1255 (7.09) |

| hsa-mir-548a-2 | MI0003598 | Chromosome 6: 135601991–135602087(+) | LTR16A1, MADE1 | 100.00 | 0.0047 | 1255 (7.09) |

| hsa-mir-548a-3 | MI0003612 | Chromosome 8: 105565773–105565869(−) | MLT1G1, MADE1 | 100.00 | 0.0044 | 1255 (7.09) |

| hsa-mir-548b | MI0003596 | Chromosome 6: 119431911–119432007(−) | MADE1 | 83.51 | 0.0175 | 1197 (5.93) |

| hsa-mir-548c | MI0003630 | Chromosome 12: 63302556–63302652(+) | MADE1 | 83.51 | 0.0092 | 1302 (6.76) |

| hsa-mir-548d-1 | MI0003668 | Chromosome 8: 124429455–124429551(−) | MADE1 | 83.51 | 0.0076 | 1055 (10.24) |

| hsa-mir-548d-2 | MI0003671 | Chromosome 17: 62898067–62898163(−) | MADE1 | 83.51 | 0.0000 | 1055 (10.24) |

| hsa-mir-552 | MI0003557 | Chromosome 1: 34907787–34907882(−) | L1MD2 | 100.00 | 0.0000 | 1067 (11.62) |

| hsa-mir-558 | MI0003564 | Chromosome 2: 32610724–32610817(+) | MLT1C | 45.74 | 0.0112 | 778 (7.58) |

| hsa-mir-562 | MI0003568 | Chromosome 2: 232745607–232745701(+) | L1MB7 | 100.00 | 0.0019 | 954 (11.64) |

| hsa-mir-566 | MI0003572 | Chromosome 3: 50185763–50185856(+) | AluSg | 100.00 | 0.0000 | 1184 (80.07) |

| hsa-mir-570 | MI0003577 | Chromosome 3: 196911452–196911548(+) | MADE1 | 82.47 | 0.0000 | 1115 (4.22) |

| hsa-mir-571 | MI0003578 | Chromosome 4: 333946–334041(+) | L1MA9 | 96.88 | 0.0000 | 948 (8.33) |

| hsa-mir-575 | MI0003582 | Chromosome 4: 83893514–83893607(−) | MIR | 61.70 | 0.0001 | 1048 (7.35) |

| hsa-mir-576 | MI0003583 | Chromosome 4: 110629303–110629400(+) | L1MB7 | 100.00 | 0.0121 | 921 (10.53) |

| hsa-mir-578 | MI0003585 | Chromosome 4: 166526844–166526939(+) | L2 | 44.79 | 0.0064 | 1012 (7.61) |

| hsa-mir-579 | MI0003586 | Chromosome 5: 32430241–32430338(−) | MADE1, L1MB8 | 100.00 | 0.3543 | 1202 (6.32) |

| hsa-mir-582 | MI0003589 | Chromosome 5: 59035189–59035286(−) | L3, L3 | 85.71 | 0.9954 | 1017 (8.06) |

| hsa-mir-584 | MI0003591 | Chromosome 5: 148422069–148422165(−) | MER81 | 92.78 | 0.0008 | 794 (10.96) |

| hsa-mir-587 | MI0003595 | Chromosome 6: 107338693–107338788(+) | MER115 | 100.00 | 0.0053 | 970 (6.39) |

| hsa-mir-588 | MI0003597 | Chromosome 6: 126847470–126847552(+) | L1MA3 | 100.00 | 0.0000 | 873 (10.77) |

| hsa-mir-603 | MI0003616 | Chromosome 10: 24604620–24604716(+) | MADE1 | 84.54 | 0.0102 | 1008 (7.44) |

| hsa-mir-606 | MI0003619 | Chromosome 10: 76982222–76982317(+) | L1MCc | 100.00 | 0.0014 | 776 (8.38) |

| hsa-mir-607 | MI0003620 | Chromosome 10: 98578416–98578511(−) | MIR | 100.00 | 0.9990 | 985 (8.83) |

| hsa-mir-616 | MI0003629 | Chromosome 12: 56199213–56199309(−) | L2 | 100.00 | 0.0004 | 922 (10.30) |

| hsa-mir-619 | MI0003633 | Chromosome 12: 107754813–107754911(−) | L1MC4, AluSx | 100.00 | 0.0008 | 765 (8.89) |

| hsa-mir-625 | MI0003639 | Chromosome 14: 65007573–65007657(+) | L1MCa | 100.00 | 0.0018 | 1065 (4.41) |

| hsa-mir-626 | MI0003640 | Chromosome 15: 39771075–39771168(+) | L1MB8, L1MCa | 56.38 | 0.0086 | 1022 (6.65) |

| hsa-mir-633 | MI0003648 | Chromosome 17: 58375308–58375405(+) | MIRb | 100.00 | 0.0136 | 843 (7.12) |

| hsa-mir-634 | MI0003649 | Chromosome 17: 62213652–62213748(+) | L1ME3A | 48.45 | 0.0019 | 886 (5.08) |

| hsa-mir-640 | MI0003655 | Chromosome 19: 19406872–19406967(+) | MIRb | 100.00 | 0.0074 | 853 (28.49) |

| hsa-mir-644 | MI0003659 | Chromosome 20: 32517791–32517884(+) | L1MB3 | 61.70 | 0.1035 | 970 (4.95) |

| hsa-mir-645 | MI0003660 | Chromosome 20: 48635730–48635823(+) | MER1B | 62.77 | 0.0002 | 682 (13.49) |

| hsa-mir-648 | MI0003663 | Chromosome 22: 16843634–16843727(−) | L2 | 98.94 | 0.0008 | 943 (6.15) |

| hsa-mir-649 | MI0003664 | Chromosome 22: 19718465–19718561(−) | L1M4, MER8, AluSx | 100.00 | 0.0005 | 1033 (10.65) |

| hsa-mir-652 | MI0003667 | Chromosome X: 109185213–109185310(+) | MER91C | 100.00 | 0.9883 | 803 (39.36) |

| hsa-mir-659 | MI0003683 | Chromosome 22: 36573631–36573727(−) | Arthur1 | 46.39 | 0.0027 | 890 (8.20) |

| hsa-mir-95 | MI0000097 | Chromosome 4: 8057928–8058008(−) | L2 | 95.06 | 0.9862 | 847 (16.06) |

Human genome (hg 18) coordinates of the miRNA.

Percentage of miRNA overlapping with TE sequence.

Total number of targets with the percentage derived from TEs in parentheses.

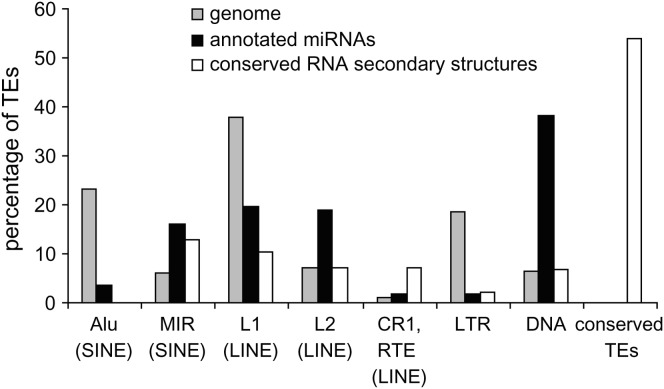

The TE-related miRNAs that we identified are derived from all four major classes of human TEs: long- and short- interspersed nuclear elements (LINE and SINE), long-terminal-repeat-containing elements (LTR) and DNA-type transposons (Table 1). Specific classes and families of TEs show marked over- or underrepresentation among human miRNAs (Figure 2). The related L2 (LINE) and MIR (SINE) families, as well as DNA elements, show far more overlap with miRNA genes than is expected on the basis of their relative frequency in the genome (37 observed vs. 11 expected; χ2 = 30.74, P = 3.0 × 10−8). Most of the DNA-type elements that contribute to miRNA genes are short nonautonomous derivatives of full-length transposons known as miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements (MITEs). This includes a group of seven closely related miRNA genes (hsa-mir-548), which are all derived from the Made1 family of MITEs (Piriyapongsa and Jordan 2007). Alu (SINE) elements and LTR type TEs are generally underrepresented among TE-derived miRNA genes. Most TE-related miRNA genes are derived from a single TE insertion, but there are several examples where nested insertion events have led to the origin of a single miRNA gene from two or even three TEs (supplemental Figure 2 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/). For instance, there are two cases where a Made1 element inserted into an LTR element yielded a miRNA gene (examples 24 and 27 in supplemental Figure 2 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/), and an insertion of an Alu into a L1 (LINE) sequence also gave rise to a miRNA gene (example 46 in supplemental Figure 2 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/).

Figure 2.—

Percentage of TE sequences among different classes and families for the human genome (shading) and for TE-derived miRNA genes (solid). Relative percentages are shown such that the total will sum to 100% for the genome and for miRNAs.

TE-derived human miRNA genes were used as queries in BLAT searches against the human genome sequence to search for putative paralogs. There are 19 cases of TE-derived miRNA genes with closely related paralogs in the human genome (Table 2). The number of paralogs per miRNA ranges from 1, for the L1-derived hsa-mir-552, to 145, for the Made1-derived hsa-mir-548d-2.

TABLE 2.

Putative TE-derived miRNA paralogs

| miRNA name (from miRBase) | miRBase accession no. | Colocated TE | Paralogsa |

|---|---|---|---|

| hsa-mir-513-1 | MI0003191 | MER91C | 3 |

| hsa-mir-513-2 | MI0003192 | MER91C | 3 |

| hsa-mir-548a-1 | MI0003593 | MADE1 | 24 |

| hsa-mir-548a-2 | MI0003598 | LTR16A1, MADE1 | 81 |

| hsa-mir-548a-3 | MI0003612 | MLT1G1, MADE1 | 82 |

| hsa-mir-548b | MI0003596 | MADE1 | 23 |

| hsa-mir-548c | MI0003630 | MADE1 | 124 |

| hsa-mir-548d-1 | MI0003668 | MADE1 | 71 |

| hsa-mir-548d-2 | MI0003671 | MADE1 | 145 |

| hsa-mir-552 | MI0003557 | L1MD2 | 1 |

| hsa-mir-562 | MI0003568 | L1MB7 | 2 |

| hsa-mir-566 | MI0003572 | AluSg | 87 |

| hsa-mir-570 | MI0003577 | MADE1 | 48 |

| hsa-mir-571 | MI0003578 | L1MA9 | 4 |

| hsa-mir-579 | MI0003586 | MADE1, L1MB8 | 3 |

| hsa-mir-603 | MI0003616 | MADE1 | 30 |

| hsa-mir-607 | MI0003620 | MIR | 1 |

| hsa-mir-649 | MI0003664 | L1M4, MER8, AluSx | 4 |

| hsa-mir-652 | MI0003667 | MER91C | 4 |

Number of paralogous sequences in the human genome.

Evolution of TE-derived miRNAs:

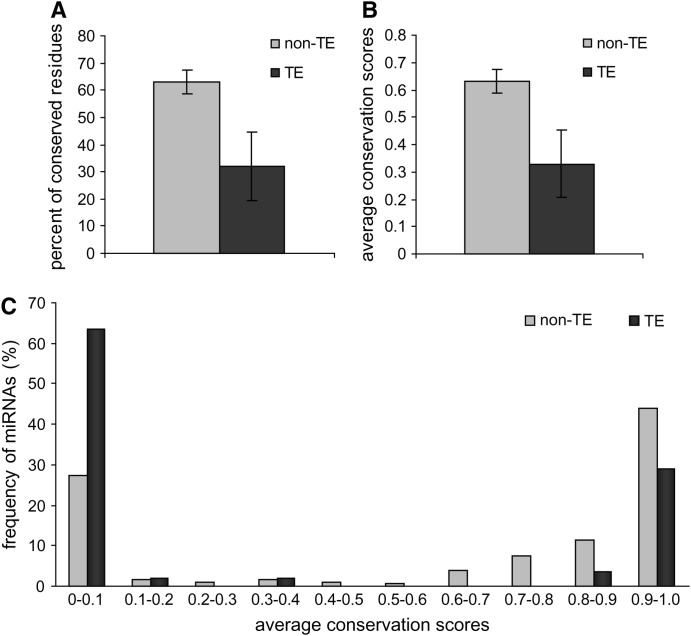

Comparative genomic sequence data were used to assess the relative evolutionary rates of TE-derived miRNAs. This analysis was based on whole-genome sequence alignments between humans and 16 other vertebrate species. Two related approaches were used to evaluate the conservation of individual miRNA sequence sites across vertebrate genomes; the first approach results in a binary characterization of either conserved or nonconserved for each site, while the second rests on a more continuous score that relates the probability of a site being conserved. All genome sites for human miRNAs were considered using these two metrics, and the relative conservation levels for TE-derived vs. non-TE-derived miRNA genes were compared. A total of 32.1% of sites in TE-derived miRNAs map to the most conserved elements in the human genome. This is far greater than the ∼5% of conserved sites seen for the entire human genome but significantly less than seen for non-TE-derived miRNAs, which have 63.2% conserved sites (t = 4.39, P = 1.4e-5, Student's t-test) (Figure 3A). When the per-site conservation probabilities of human miRNAs were measured, a similar pattern was observed. The average conservation score of TE-derived miRNAs was 0.33 compared to 0.63 for non-TE-derived miRNAs (t = 4.37, P = 1.5e-5, Student's t-test) (Figure 3B). In addition, the frequency distribution of the average conservation scores for all human miRNA genes reveals that, compared to non-TE-derived miRNAs, there are far more TE-derived miRNAs that show little or no conservation and fewer that are highly conserved (Figure 3C). Thus, on the whole, TE-derived miRNAs are significantly less conserved than non-TE-derived miRNAs.

Figure 3.—

Evolutionary conservation of human miRNA genes. (A) The percentage of conserved residues for non-TE-derived miRNAs (shading) vs. TE-derived miRNAs (solid) with 95% confidence intervals shown. (B) The average per-site conservation score for non-TE-derived miRNAs (shading) vs. TE-derived miRNAs (solid) with 95% confidence intervals shown. (C) Frequency distribution of the average per-site conservation scores for non-TE-derived miRNAs (shading) vs. TE-derived miRNAs (solid).

We used the frequency distribution of average conservation scores to divide TE-derived miRNAs into conserved (≥0.8 average conservation probability) and nonconserved (<0.8 average conservation probability) groups. Using this criteria, there are 37 nonconserved and 18 conserved TE-derived miRNAs (Table 1). The least-conserved TE-derived miRNAs are primate specific, having orthologous sequences in the chimpanzee only or both the chimpanzee and Rhesus genomes. Of 18 conserved miRNAs, 14 are derived from the L2 and MIR families; this is far more than would be expected on the basis of the overall frequency of L2 and MIR sequences among TE-derived miRNAs (χ2 = 17.8, P = 3.6e-5). The conservation of L2 and MIR TE-derived miRNAs is consistent with a previous study that found many anomalously conserved L2 and MIR sequences (Silva et al. 2003). Indeed, L2 and MIR are relatively ancient TE families with many sequences that inserted prior to the divergence of the human and mouse evolutionary lineages. We observed 10 of the conserved L2- and MIR-derived miRNA sequences to have orthologous sequences in the mouse genome, and there are 9 orthologous mouse miRNAs in these regions that are annotated in miRBase (Table 3). All of the 8 conserved L2 miRNAs are derived from the same region near the 3′-end of the L2 consensus sequence (approximately positions 3200–3400), while the 6 MIR-derived miRNAs are found in dispersed locations on the MIR consensus sequence.

TABLE 3.

Human–mouse orthologous miRNAs derived from L2 and MIR TEs

| miRBase names and accession nos. for human orthologous miRNAs | Genome coordinates for human orthologous regions | Related TE sequence | miRBase names and accession nos. for mouse orthologous miRNAs | Genome coordinates for mouse orthologous regions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hsa-mir-345: MI0000825 | Chromosome 14: 99843949–99844046(+) | MIR | mmu-mir-345: MI0000632 | Chromosome 12: 109,284,780–109,284,874 (+) |

| hsa-mir-130b: MI0000748 | Chromosome 22: 20337593–20337674(+) | MIRm | mmu-mir-130b: MI0000408 | Chromosome 16: 17,037,626–17,037,705(−) |

| hsa-mir-151: MI0000809 | Chromosome 8: 141811845–141811934(−) | L2 | mmu-mir-151: MI0000173 | Gap |

| hsa-mir-95: MI0000097 | Chromosome 4: 8057928–8058008(−) | L2 | — | Gap |

| hsa-mir-330: MI0000803 | Chromosome 19: 50834092–50834185(−) | MIRm | mmu-mir-330: MI0000607 | Chromosome 7: 18,339,991–18,340,084(+) |

| hsa-mir-370: MI0000778 | Chromosome 14: 100447229–100447303(+) | MIRm | mmu-mir-370: MI0001165 | Chromosome 12: 110,066,065–110,066,139(+) |

| hsa-mir-325: MI0000824 | Chromosome X: 76142220–76142317(−) | L2 | mmu-mir-325: MI0000597 | Chromosome X: 101,581,801–101,581,898(−) |

| hsa-mir-545: MI0003516 | Chromosome X: 73423664–73423769(−) | L2 | — | Chromosome X: 99,818,159–99,818,260(−) |

| hsa-mir-374: MI0000782 | Chromosome X: 73423846–73423917(−) | L2 | mmu-mir-374: MI0004125 | Chromosome X: 99,818,306–99,818,361(−) |

| hsa-mir-28: MI0000086 | Chromosome 3: 189889263–189889348(+) | L2 | mmu-mir-28: MI0000690 | Chromosome 16: 24,743,204–24,743,289(+) |

| hsa-mir-493: MI0003132 | Chromosome 14: 100405150–100405238(+) | L2 | — | Chromosome 12: 110,028,035–110,028,123(+) |

| hsa-mir-607: MI0003620 | Chromosome 10: 98578416–98578511(−) | MIR | — | Gap |

| hsa-mir-421: MI0003685 | Chromosome X: 73354937–73355021(−) | L2 | — | Chromosome X: 99,775,634–99,775,718(−) |

| hsa-mir-378: MI0000786 | Chromosome 5: 149092581–149092646(+) | MIRb | mmu-mir-378: MI0000795 | Gap |

“Gap” indicates no orthologous region.

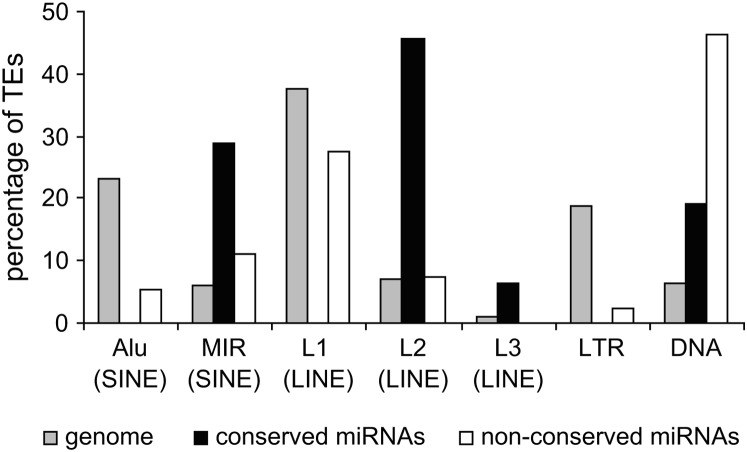

A frequency distribution of conserved vs. nonconserved TE-derived miRNA genes, compared to genomewide relative TE frequencies, reveals distinct conservation levels for miRNAs derived from particular TE classes/families (Figure 4). For instance, L2 and MIRs contribute far more conserved than nonconserved miRNAs, and the fraction of conserved L2 and MIR elements in miRNAs is much higher than seen for these same elements in the genome as a whole. DNA-type elements show the opposite pattern. There is a higher fraction of nonconserved DNA-type elements among miRNAs than is seen for the whole genome. All of the miRNAs derived from Alu and L1 elements are nonconserved.

Figure 4.—

Percentage of TE sequences among different classes and families for the human genome (shading), for conserved TE-derived miRNAs (solid), and for nonconserved TE-derived miRNAs (open). Relative percentages are shown such that the total will sum to 100% for the genome and for each group of miRNAs.

Regulation and function:

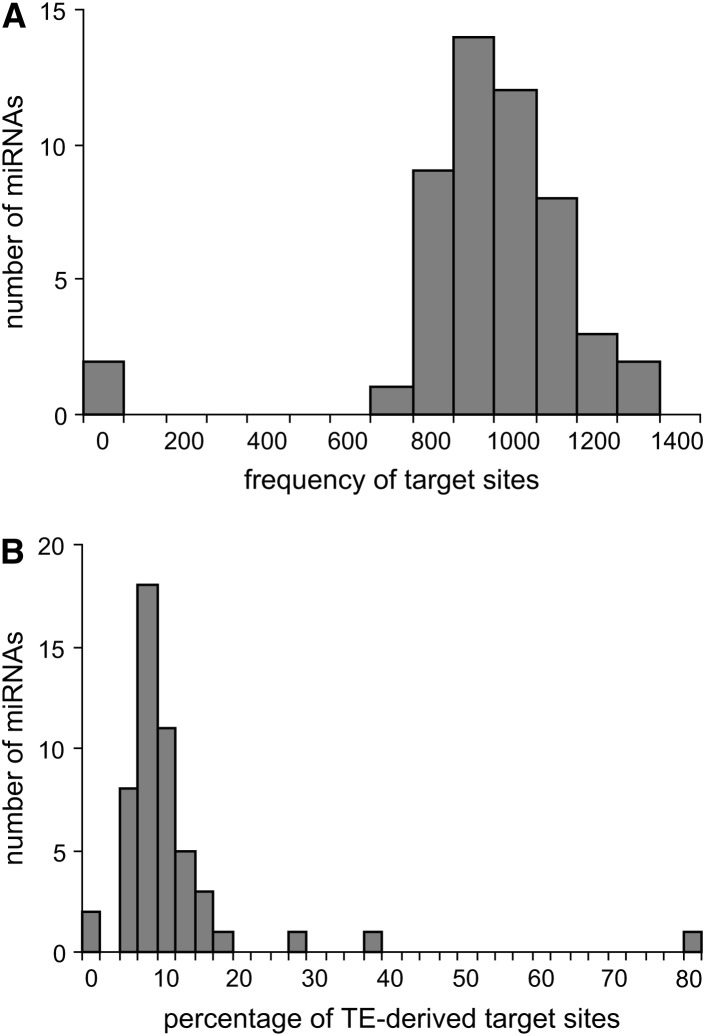

Given their high copy numbers, there is a potential for TE-derived miRNAs to regulate multiple genes via homologous target sites dispersed throughout genome. Using the miRBase target predictions, TE-derived miRNAs were found to have hundreds of putative target sites (Table 1; Figure 5A). However, while many of these target sites are also derived from TEs, in most cases the proportion of TE-derived target sites is ∼10% (Table 1; Figure 5B). Thus, TE-derived miRNAs also have the potential to regulate host genes with non-TE-derived targets. The relative paucity of TE-derived target sites can be attributed, in part, to the fact that target-site prediction methods employ conservation of 3′-UTR sequences as one criteria and TEs tend to be lineage specific and nonconserved.

Figure 5.—

Target-site frequencies for TE-derived miRNAs. (A) Frequency distribution showing the number of target sites per TE-derived miRNA. (B) Frequency distribution showing the percentage of TE-derived target sites per TE-derived miRNA.

There are several outliers that have a substantially higher fraction of TE-derived target sites. For instance, hsa-mir-566 is derived from Alu and it has 1184 predicted targets with 948 (80%) derived from TEs. Most of these TE-derived hsa-mir-566 target sites are related to Alu insertions and this is consistent with previous studies that have found numerous putative Alu-related miRNA target sites in the human genome (Daskalova et al. 2006; Smalheiser and Torvik 2006).

The predicted target sites analyzed here are all putative sites and it is difficult to know with certainty whether they are actually involved in miRNA-mediated gene regulation. Another way to evaluate the regulatory potential of miRNAs is to compare the expression patterns of miRNAs to the expression patterns of the genes they are thought to regulate (Farh et al. 2005; Stark et al. 2005; Huang et al. 2006; Sood et al. 2006). The rationale behind the miRNA–mRNA expression pattern comparison is based on the mRNA degradation model of miRNA action. According to this model, miRNA binding to mRNA target sites causes the mRNA transcripts to be degraded. This model predicts anti-correlations between expression levels of miRNAs and the mRNAs of their target genes; i.e., high levels of miRNA would lead to decreased levels of targeted mRNA.

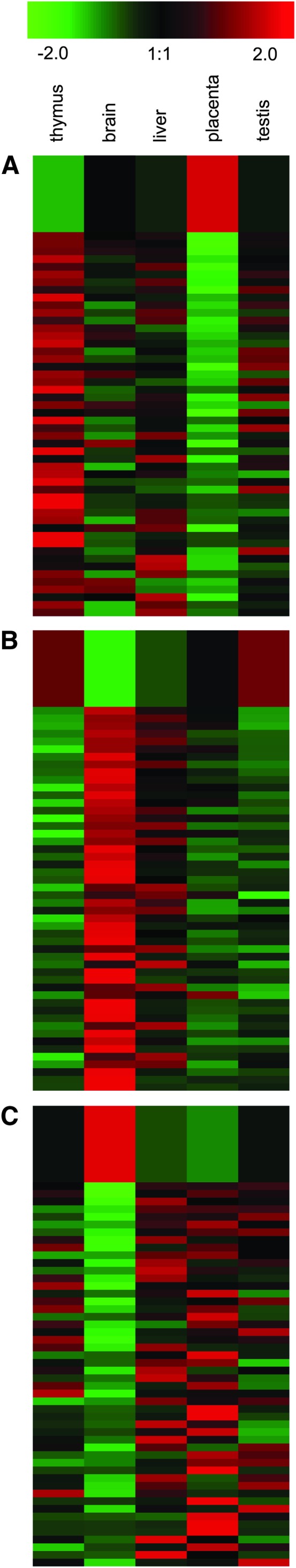

We sought to compare miRNA expression levels for TE-derived miRNA genes to mRNA expression levels of their target genes to look for anti-correlations that are consistent with regulation via mRNA degradation. miRNA expression data were taken from a microarray study of 150 human miRNAs across five tissue samples (Barad et al. 2004), and mRNA expression data were taken from the Novartis SymAtlas (Su et al. 2004). Pairs of miRNA–mRNA gene expression profile vectors were compared using the Pearson correlation coefficient (r). There were only three TE-derived miRNA genes with expression data available. Despite this small sample size and the fairly low resolution afforded by the comparison of only five tissues, we found numerous cases of strongly anti-correlated miRNA–mRNA pairs (Figure 6). Since this anti-correlation is consistent with the mRNA degradation model of miRNA gene regulation, it provides an additional source of support for putative miRNA target sites and the regulatory action of TE-derived miRNAs.

Figure 6.—

Anti-correlated expression patterns for TE-derived miRNAs and their targeted mRNAs. Results for three TE-derived miRNAs with expression data are shown: hsa-mir-130b (A), hsa-mir-28 (B), and hsa-mir-95 (C). The top row in A–C shows the relative miRNA expression across five human tissues, and the subsequent rows show relative expression levels for targeted mRNAs. The 50 most-negative Pearson correlation coefficients (range r = −0.99 to −0.51; P = 1.2 × 10−10–1.3 × 10−1) are shown for each plot.

We also evaluated the GO biological process annotations of the anti-correlated gene sets to look for overrepresented functional categories that may indicate specific functional roles for TE-derived miRNAs. The top 10% of anti-correlated mRNAs (i.e., those with the lowest r-values) for each of the three TE-derived miRNAs with expression data were evaluated for overrepresented GO terms. The miRNA hsa-mir-130b gave the strongest signal of GO term overrepresentation; 39 of 80 genes were found to correspond to significantly overrepresented GO terms (supplemental Table 1 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/). Many of these genes correspond to metabolism and transcriptional regulation in general as well as to several negative regulators of DNA metabolism (supplemental Figure 3 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/). This negative regulation is achieved in part by chromatin remodeling, silencing, and heterochromatin formation. Thus, hsa-mir-130b may act to indirectly upregulate DNA metabolism by downregulating chromatin-based repressors.

Prediction of novel TE-derived miRNAs:

The function of miRNAs, and of noncoding RNAs in general, is related to their secondary structure (Mattick and Makunin 2006). Selective constraint on such sequences often leads to compensatory mutations that maintain the base-pair interactions in the double-stranded regions of the structures, such as miRNA stem regions. Sequence alignments can be evaluated for the signal of conserved base-pair interactions as well as compensatory mutations to identify conserved, and thus presumably functionally relevant, secondary structural elements. Recent application of such techniques has led to the discovery of many novel putative regulatory RNA sequences (Washietl et al. 2005; Pedersen et al. 2006). It has even been shown that orthologous regions that are not constrained at the level of primary sequence may nevertheless encode conserved secondary structural elements (Torarinsson et al. 2006). Given the contribution of TEs to experimentally characterized miRNAs shown here and elsewhere (Smalheiser and Torvik 2005; Borchert et al. 2006; Piriyapongsa and Jordan 2007), we sought to evaluate human TE sequences for the ability to form hairpin structures along with the signals of conserved base pairs and compensatory mutations that indicate putatively functional secondary structures. This approach provides a way to predict further contributions of TEs to miRNAs.

Human genome TE sequences were evaluated for the potential to encode conserved secondary structures (Pedersen et al. 2006) that meet the criteria of miRNA genes (Bentwich et al. 2005). This approach is conservative in the sense that it relies on sequence conservation and most of the experimentally characterized TE-derived miRNAs that we observe (37 of 55) are not evolutionarily conserved. Using this conservative approach, we found 587 human TEs with the potential to encode conserved secondary structures (supplemental Table 2 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/); 4 of these sequences corresponded to previously known human miRNAs annotated in miRBase. Evaluation of these conserved secondary structures was used to identify 85 TE-derived sequences that meet the structural criteria of putative miRNA genes, and 70 of these sequences also show evidence of being expressed (Table 4). These 70 putative TE-derived miRNA sequences meet the previously defined biogenesis, conservation, and, at least in principle, expression criteria used for the identification of miRNA genes (Ambros et al. 2003).

TABLE 4.

Predicted TE-derived miRNA genes

| Namea | Coordinatesb | Colocated TE | Expression datac |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3715_0_+_61 | Chromosome 1: 3131597–3131629(+) | MER121 | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 15086_0_−_78 | Chromosome 1: 15041842–15041859(−) | HAL1 | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 25288_0_−_83 | Chromosome 1: 23621848–23621877(−) | MIRb | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 30647_0_+_38 | Chromosome 1: 27752374–27752433(+) | MIRb | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 52664_0_−_50 | Chromosome 1: 44571346–44571464(−) | Eulor9A | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 67626_0_−_76 | Chromosome 1: 57127400–57127465(−) | Eulor1 | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 85615_0_+_83 | Chromosome 1: 76474930–76474947(+) | MIRb | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 120809_0_+_79 | Chromosome 1: 111021701–111021719(+) | MIR | EST/mRNA |

| 122080_0_−_62 | Chromosome 1: 112177611–112177631(−) | MIR | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 124780_0_−_66 | Chromosome 1: 114214379–114214407(−) | MIRb | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 154818_0_−_64 | Chromosome 1: 162825371–162825437(−) | MER135 | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 188052_1_−_92 | Chromosome 1: 198460508–198460590(−) | Eulor3 | — |

| 204532_0_−_104 | Chromosome 1: 211522027–211522054(−) | UCON31 | EST |

| 230542_0_−_67 | Chromosome 1: 244286075–244286098(−) | L1MB3 | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 1231553_0_+_75 | Chromosome 2: 67238894–67239028(+) | Eulor4 | EST/mRNA |

| 1258257_0_+_85 | Chromosome 2: 104314401–104314489(+) | MER134 | — |

| 1361323_0_+_57 | Chromosome 2: 213067475–213067509(+) | Eulor5A | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 1573547_0_+_44 | Chromosome 3: 61643441–61643518(+) | MER126 | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 1573643_0_+_95 | Chromosome 3: 61718341–61718381(+) | MER134 | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 1620066_0_−_64 | Chromosome 3: 116298434–116298458(−) | Eulor1 | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 1651767_0_+_52 | Chromosome 3: 146074810–146074873(+) | Eulor3 | — |

| 1668216_0_−_58 | Chromosome 3: 168436231–168436447(−) | MER126 | — |

| 1730972_0_−_56 | Chromosome 4: 46681709–46681733(−) | L1ME3B | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 1747758_0_−_63 | Chromosome 4: 74275595–74275629(−) | L1M5 | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 1757379_0_+_70 | Chromosome 4: 85466757–85466855(+) | MER134 | — |

| 1827751_0_+_75 | Chromosome 4: 181988895–181988914(+) | MIRb | EST |

| 1830405_0_+_49 | Chromosome 4: 183690755–183690850(+) | MER135 | EST/mRNA/RS |

| 1873731_0_+_53 | Chromosome 5: 58495675–58495729(+) | UCON9 | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 1902777_0_+_53 | Chromosome 5: 90643387–90643420(+) | AmnSINE1_GG | EST/mRNA |

| 1920501_0_+_72 | Chromosome 5: 113735156–113735173(+) | L2 | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 1966281_0_+_83 | Chromosome 5: 156681824–156681841(+) | MIR3 | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 1975838_0_−_80 | Chromosome 5: 165688874–165688944(−) | Eulor5A | — |

| 1979031_0_+_61 | Chromosome 5: 167506770–167506888(+) | Eulor9A | EST/mRNA/RS |

| 1987527_0_+_59 | Chromosome 5: 175727565–175727628(+) | L2 | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 2000476_0_−_85 | Chromosome 6: 8499794–8499914(−) | Eulor6C | EST/mRNA |

| 2031067_0_+_44 | Chromosome 6: 39048083–39048162(+) | Eulor5A | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 2075048_0_−_91 | Chromosome 6: 94484941–94484963(−) | ERVL-E | EST/mRNA |

| 2115069.5_0_+_82 | Chromosome 6: 141179709–141179763(+) | Eulor5B | — |

| 2165103_0_+_104 | Chromosome 7: 28447122–28447144(+) | MER121 | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 2195049_0_+_117 | Chromosome 7: 73161289–73161306(+) | MIR3 | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 2232211_0_+_45 | Chromosome 7: 113190696–113190791(+) | Eulor6B | — |

| 2247695_1_+_65 | Chromosome 7: 129521966–129521985(+) | L1ME4a | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 2265159_0_+_85 | Chromosome 7: 146833245–146833271(+) | UCON4 | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 2330918_0_−_108 | Chromosome 8: 79081399–79081462(-) | Eulor3 | — |

| 2344217_0_+_65 | Chromosome 8: 97188471–97188580(+) | MER135 | EST |

| 2348773_0_+_51 | Chromosome 8: 102229956–102230022(+) | Charlie9 | — |

| 2401146_0_−_96 | Chromosome 9: 16787222–16787246(−) | MIR | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 2421368_0_−_79 | Chromosome 9: 37811135–37811158(−) | L1MC4a | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 2426661_0_+_64 | Chromosome 9: 70297285–70297306(+) | MER91A | EST/KG/RS |

| 2455634_0_−_64 | Chromosome 9: 105918396–105918420(−) | MER5A | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 2469999_0_+_79 | Chromosome 9: 118715772–118715795(+) | UCON11 | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 2500550_0_−_83 | Chromosome X: 10899595–10899617(−) | L4 | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 2519737_0_+_67 | Chromosome X: 24557155–24557175(+) | L1ME4a | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 2598753_0_+_171 | Chromosome X: 123865376–123865447(+) | Eulor11 | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 2607024_0_−_68 | Chromosome X: 131689852–131689873(−) | L1MB5 | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 2625375_0_+_86 | Chromosome X: 152562536–152562556(+) | L2 | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 276291_0_+_66 | Chromosome 10: 62836157–62836220(+) | L1M5 | — |

| 285555_0_+_63 | Chromosome 10: 72980870–72980944(+) | MER125 | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 334961_0_+_78 | Chromosome 10: 117579937–117579954(+) | L2 | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 335779_0_+_54 | Chromosome 10: 118027456–118027512(+) | Eulor6D | EST |

| 377681_0_+_96 | Chromosome 11: 19331037–19331062(+) | L3 | mRNA/KG |

| 425555_0_+_71 | Chromosome 11: 71985685–71985701(+) | MIR | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 438439_0_+_83 | Chromosome 11: 83316376–83316398(+) | L2 | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 486187_0_+_68 | Chromosome 11: 130861130–130861151(+) | MIRb | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 487071_2_+_103 | Chromosome 11: 131453921–131453949(+) | MER122 | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 492576_0_−_95 | Chromosome 12: 2125422–2125443(−) | MIRb | mRNA/KG/RS |

| 533638.0_0_−_122 | Chromosome 12: 50492331–50492353(−) | MIRb | mRNA/KG |

| 542148_0_−_83 | Chromosome 12: 55246557–55246574(−) | LTR37B | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 551096_0_−_85 | Chromosome 12: 64538090–64538148(−) | Eulor5A | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 596947_0_+_93 | Chromosome 12: 115505370–115505426(+) | MER123 | EST/mRNA |

| 697653_0_+_69 | Chromosome 14: 33093444–33093479(+) | UCON11 | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 700890_0_−_65 | Chromosome 14: 35855217–35855366(−) | Eulor6A | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 775713_0_+_77 | Chromosome 15: 25703141–25703162(+) | L1MCc | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 787092_0_−_65 | Chromosome 15: 35993736–35993832(−) | Eulor5A | — |

| 896537_0_+_81 | Chromosome 16: 30749660–30749680(+) | MIR | EST |

| 928869_0_+_74 | Chromosome 16: 70304015–70304037(+) | MIR3 | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 976169_0_+_86 | Chromosome 17: 24040248–24040268(+) | L1ME4a | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 989909_0_+_100 | Chromosome 17: 34009010–34009024(+) | MIR3 | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 1000039.8_0_+_109 | Chromosome 17: 39468501–39468532(+) | L1MC4 | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 1077028_0_−_58 | Chromosome 18: 33875730–33875789(−) | MIRb | — |

| 1105916_0_−_78 | Chromosome 18: 71369451–71369514(−) | UCON11 | — |

| 1435354_0_−_79 | Chromosome 20: 44235903–44235921(−) | MIR | EST/mRNA/KG/RS |

| 1443968_0_−_61 | Chromosome 20: 53838763–53838824(−) | UCON29 | — |

| 1466070_0_−_70 | Chromosome 21: 33853177–33853203(−) | L2 | EST/mRNA |

| 1496941_0_+_79 | Chromosome 22: 35289947–35289989(+) | L1MC4 | EST |

Name of the EvoFold locus from the hg18 UCSC Genome Browser annotation. The last field in the name corresponds to the EvoFold score.

Genome coordinates and strand of the EvoFold locus.

Source of the expression data for the locus: KG, UCSC Genome Browser known gene annotation; RS, NCBI RefSeq annotation.

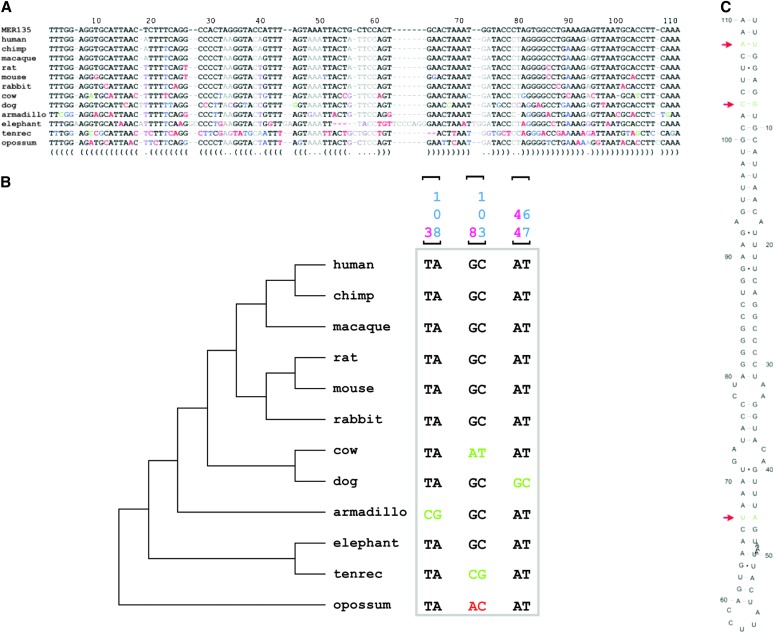

An example of a predicted TE-derived miRNA gene is shown in Figure 7. The MER135 sequence shown is a member of a family of recently characterized nonautonomous DNA-type elements, i.e., MITEs, with ∼500 copies in the human genome (Jurka 2006). Since MITEs have palindromic structures with terminal inverted repeats that flank short internal regions, their expression as RNA results in the formation of the kinds of hairpins seen for pre-miRNAs. Indeed, MITEs have previously been shown to contribute miRNA genes in the Arabidopsis and human genomes (Mette et al. 2002; Piriyapongsa and Jordan 2007).

Figure 7.—

Ab initio prediction of human TE-derived miRNA genes. (A) Multiple sequence alignment of the MER135 consensus sequence with the human genome sequence and orthologous genomic regions from 11 other vertebrate genomes. The predicted secondary structure is shown below the alignment with paired and unpaired positions indicated by parentheses and dots, respectively. Residues are colored according to the annotated secondary structure base pairs and their substitutions: gray, unpaired and no substitution; purple, unpaired and substitution; black, paired and no substitution; blue, paired and single substitution; green, paired and double substitution; red, not compatible with annotated pair. (B) Phylogenetic tree of the aligned species showing the double substitutions that maintain the secondary structure. Paired double substitutions are indicated with brackets and their positions in the alignment are shown. (C) Secondary structure of the predicted miRNA gene. Positions of the double substitutions are indicated by red arrows.

DISCUSSION

Abundance of TE-derived miRNAs:

Noncoding regulatory RNAs, such as miRNAs, are a recently discovered class of genes, and the number of miRNA genes that exist among eukaryotic genomes is very much an open question (Berezikov et al. 2006). Sustained efforts at high-throughput characterization of miRNA genes, based on both experimental and computational approaches, continue to result in the discovery of many novel miRNAs (Bentwich et al. 2005; Cummins et al. 2006). This can be appreciated by examining the release statistics of miRBase (ftp://ftp.sanger.ac.uk/pub/mirbase/sequences/CURRENT/README). Plotting the number of miRNA gene entries against the miRBase release dates suggests that the number of known miRNA genes has experienced two distinct phases of linear increase, before and after the June 2005 release, and the current rate of increase in known miRNA genes is even greater than for the initial phase (supplemental Figure 4 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/).

For the most part, the miRBase data do not include substantial numbers of computationally predicted miRNA genes. The only computational predictions represented in miRBase are highly conserved sequences that are orthologous to experimentally characterized miRNA genes in other species. Consideration of computationally identified miRNAs would suggest that miRNA gene numbers are substantially higher than currently appreciated. However, a number of computational methods for miRNA prediction do not consider TE-derived miRNAs (Bentwich et al. 2005; Lindow and Krogh 2005; Nam et al. 2005; Li et al. 2006). This is because, mainly for reasons of tractability, one of the first steps in computational analysis of eukaryotic genome sequences is the exclusion of repetitive DNA by RepeatMasking. TEs will also tend to be excluded from predictions based solely on conservation between species because they are rapidly evolving and lineage-specific genomic elements. This is underscored by the fact that the set of TE-derived human miRNAs that we identify here is enriched for genes experimentally characterized in humans (93% for TE-derived vs. 81% for non-TE-derived miRNAs; χ2 = 4.76, P = 0.03).

The factors described above that suggest the exclusion of TE-derived miRNAs led us to speculate as to how many more miRNA genes would be discovered if TE sequences were not eliminated from consideration a priori. To investigate this, we employed our own ab initio computational approach to try and predict TE-derived miRNA sequences. Application of this method to the human genome revealed 587 cases of human TE sequences that encode conserved RNA secondary structures, 85 of which are most likely to represent bona fide miRNA genes. Fifteen of the TE-derived miRNA genes that we predicted using this approach overlap with previous miRNA computational predictions (Berezikov et al. 2005; Pedersen et al. 2006) as well as experimentally characterized miRNAs from miRBase.

Conservation of TE-derived miRNAs:

Many miRNA genes are evolutionarily conserved and may have functional orthologs in multiple species. Indeed, sequence conservation is one of the criteria used to aid the computational discovery of miRNAs. While the TE-derived miRNA genes analyzed here are less conserved, on average, than non-TE-derived miRNAs, there are a number of well-conserved miRNAs that evolved from TE sequences (Table 1). The majority of these conserved miRNAs are related to the ancient L2 and MIR TE families, and some of these sequences have been previously identified (Smalheiser and Torvik 2005). This is particularly interesting because numerous L2 and MIR sequences have been shown to be anomalously conserved between the human and mouse genomes (Silva et al. 2003). Specifically, Silva et al. (2003) demonstrated that many L2 and MIR sequences found in orthologous human–mouse intergenic regions were present in the common ancestor of the two species and, following their divergence, evolved under strong selective constraint. From this, they reasoned that these selectively constrained sequences probably play some role related to gene regulation, although no specific functional role was ascribed to them. Here, we show that at least some of these conserved L2 and MIR fragments provide miRNA sequences with the potential to regulate numerous human genes.

As in the case of L2 and MIR (Silva et al. 2003), comparative genomic approaches are used to infer functionally important genomic regions, particularly noncoding regions, by virtue of their high sequence conservation (Zhang and Gerstein 2003). It is becoming increasingly apparent that a number of such highly conserved genomic sequences correspond to TEs (Bejerano et al. 2006; Kamal et al. 2006; Nishihara et al. 2006; Xie et al. 2006). While enhancer activity has been demonstrated for one of these conserved TEs (Bejerano et al. 2006), for the most part, the specific function encoded by conserved TE sequences remains unknown. The collection of conserved TE sequences recently assembled by Repbase corresponds to <1% of all human genome TEs, but these sequences contribute >50% of all TE-encoded conserved secondary structures that we detected (Figure 2). Thus, our results suggest that many conserved TE sequences may encode miRNAs or perhaps other noncoding regulatory or structural RNAs.

Lineage-specific effects of TE-derived miRNAs:

Most of the TE-derived miRNAs analyzed here are not evolutionarily conserved (Table 1). This is not surprising when you consider that TEs are the most lineage-specific and nonconserved elements found in eukaryotic genomes (Lander et al. 2001). The overrepresentation of nonconserved sequences among TE-derived miRNAs is also consistent with previous work that has shown TE-derived cis-regulatory binding sites to be more divergent than non-TE-derived cis sites (Mariño-Ramirez et al. 2005). From a practical perspective, this means that computational discovery methods that employ conservation as a criterion will necessarily overlook many TE-derived regulatory sequences. In terms of evolution, this means that the greatest differences between eukaryotic genomes will correspond to TE sequences. In this sense, TEs can be considered as drivers of genome diversification. This may be uninteresting if TEs serve only to replicate themselves and do not play any role for their host genomes as the selfish DNA theory of TEs holds (Doolittle and Sapienza 1980; Orgel and Crick 1980). However, if some TEs are in fact functionally relevant to their hosts, as we have shown here for the case of TE-derived miRNAs, then their divergence may have important evolutionary implications. Indeed, TE-derived regulatory sequences may be particularly prone to contribute to regulatory differences among species that lead to lineage-specific phenotypes. This has been shown for the case of TE-derived regulatory sequences that are associated with high levels of expression divergence between humans and mice (Mariño-Ramirez and Jordan 2006).

While most computational efforts to discover noncoding regulatory sequences have focused on conserved genomic elements, recent studies have begun to emphasize rapidly evolving regions as well (Pollard et al. 2006a,b; Prabhakar et al. 2006). The rationale behind this is the notion that rapidly evolving regulatory regions may yield species-specific differences. An emphasis on the discovery of TE-derived regulatory sequences would complement current approaches to the discovery of rapidly evolving regulatory regions that are likely to contribute to the phenotypic divergence among species.

Genome defense and global gene regulatory mechanisms:

Finally, we speculate that our results point to a connection between genome defense mechanisms necessitated by TEs and the emergence of global gene regulatory systems that may have allowed for the complex regulatory phenotypes characteristic of multicellular eukaryotes. TE insertions are highly deleterious and, as a consequence, a number of global gene-silencing mechanisms, including methylation (Yoder et al. 1997), imprinting (McDonald et al. 2005), and heterochromatin (Lippman et al. 2004), may have evolved originally as TE defense mechanisms. siRNAs are also thought to have evolved as a defense mechanism against TEs (Matzke et al. 2000; Vastenhouw and Plasterk 2004; Slotkin et al. 2005), and the results reported here and elsewhere (Smalheiser and Torvik 2005; Borchert et al. 2006; Piriyapongsa and Jordan 2007) indicate that miRNAs can emerge from TEs as well. More recently, an analogous TE defense mechanism based on small RNAs complementary to TEs in Drosophila has been reported (Brennecke et al. 2007). Apparently, different RNA interference systems may have evolved convergently on multiple occasions to help silence TEs. Later, these regulatory mechanisms could have been co-opted to exert controlling effects over thousands of host genes as is the case for miRNAs. The evolution of such complex gene regulatory systems can be considered nonadaptive (Lynch 2007) in the sense that they did not evolve by virtue of selection for the role that they play now. However, neither did these global regulatory mechanisms evolve passively since they were swept to fixation by selective pressure to defend against TEs. Therefore, the emergence of TE-related global regulatory systems, exemplified by RNA interference, can be considered to be exaptations (Gould and Vrba 1982) driven by the internal mutational dynamics (Stoltzfus 2006) of the genome.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nalini Polavarapu and Ahsan Huda for technical support and helpful comments. Jittima Piriyapongsa is supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of Thailand. I. King Jordan is supported by the School of Biology at the Georgia Institute of Technology. This research was supported in part by the intramural research program of the National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

References

- Ambros, V., 2004. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature 431 350–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambros, V., B. Bartel, D. P. Bartel, C. B. Burge, J. C. Carrington et al., 2003. A uniform system for microRNA annotation. RNA 9 277–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner, M., C. A. Ball, J. A. Blake, D. Botstein, H. Butler et al., 2000. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 25 25–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barad, O., E. Meiri, A. Avniel, R. Aharonov, A. Barzilai et al., 2004. MicroRNA expression detected by oligonucleotide microarrays: system establishment and expression profiling in human tissues. Genome Res. 14 2486–2494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel, D. P., 2004. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116 281–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejerano, G., C. B. Lowe, N. Ahituv, B. King, A. Siepel et al., 2006. A distal enhancer and an ultraconserved exon are derived from a novel retroposon. Nature 441 87–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentwich, I., A. Avniel, Y. Karov, R. Aharonov, S. Gilad et al., 2005. Identification of hundreds of conserved and nonconserved human microRNAs. Nat. Genet. 37 766–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berezikov, E., V. Guryev, J. van de Belt, E. Wienholds, R. H. Plasterk et al., 2005. Phylogenetic shadowing and computational identification of human microRNA genes. Cell 120 21–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berezikov, E., E. Cuppen and R. H. Plasterk, 2006. Approaches to microRNA discovery. Nat. Genet. 38(Suppl.): S2–S7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchette, M., W. J. Kent, C. Riemer, L. Elnitski, A. F. Smit et al., 2004. Aligning multiple genomic sequences with the threaded blockset aligner. Genome Res. 14 708–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchert, G. M., W. Lanier and B. L. Davidson, 2006. RNA polymerase III transcribes human microRNAs. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13 1097–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennecke, J., D. R. Hipfner, A. Stark, R. B. Russell and S. M. Cohen, 2003. bantam encodes a developmentally regulated microRNA that controls cell proliferation and regulates the proapoptotic gene hid in Drosophila. Cell 113 25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennecke, J., A. A. Aravin, A. Stark, M. Dus, M. Kellis et al., 2007. Discrete small RNA-generating loci as master regulators of transposon activity in Drosophila. Cell 128 1089–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britten, R. J., 1996. DNA sequence insertion and evolutionary variation in gene regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93 9374–9377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. Z., L. Li, H. F. Lodish and D. P. Bartel, 2004. MicroRNAs modulate hematopoietic lineage differentiation. Science 303 83–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, J. M., Y. He, R. J. Leary, R. Pagliarini, L. A. Diaz, Jr. et al., 2006. The colorectal microRNAome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103 3687–3692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daskalova, E., V. Baev, V. Rusinov and I. Minkov, 2006. 3′ UTR-located Alu elements: donors of potential miRNA target sites and mediators of network miRNA-based regulatory interactions. Evol. Bioinform. Online 2 99–116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolittle, W. F., and C. Sapienza, 1980. Selfish genes, the phenotype paradigm and genome evolution. Nature 284 601–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enright, A. J., B. John, U. Gaul, T. Tuschl, C. Sander et al., 2003. MicroRNA targets in Drosophila. Genome Biol. 5 R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farh, K. K., A. Grimson, C. Jan, B. P. Lewis, W. K. Johnston et al., 2005. The widespread impact of mammalian MicroRNAs on mRNA repression and evolution. Science 310 1817–1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould, S. J., and E. S. Vrba, 1982. Exaptation: a missing term in the science of form. Paleobiology 8 4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths-Jones, S., R. J. Grocock, S. van Dongen, A. Bateman and A. J. Enright, 2006. miRBase: microRNA sequences, targets and gene nomenclature. Nucleic Acids Res. 34 D140–D144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofacker, I. L., W. Fontana, P. F. Stadler, S. Bonhoeffer, M. Tacker et al., 1994. Fast folding and comparison of RNA secondary structures. Monatsh. Chem. 125 167–188. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J. C., Q. D. Morris and B. J. Frey, 2006. Detecting microRNA targets by linking sequence, microRNA and gene expression data, pp. 114–129 in RECOMB 2006, edited by A. Apostolico, C. Guerra, S. Istrail, P. A. Pevzner and M. S. Waterman. Springer-Verlag, Venice, Italy.

- Jordan, I. K., I. B. Rogozin, G. V. Glazko and E. V. Koonin, 2003. Origin of a substantial fraction of human regulatory sequences from transposable elements. Trends Genet. 19 68–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurka, J., 2006 MER135: conserved mammalian repeat, probably derived from a non-autonomous DNA transposon. Repbase Rep. 6 388.

- Jurka, J., V. V. Kapitonov, A. Pavlicek, P. Klonowski, O. Kohany et al., 2005. Repbase Update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 110 462–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal, M., X. Xie and E. S. Lander, 2006. A large family of ancient repeat elements in the human genome is under strong selection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103 2740–2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karolchik, D., A. S. Hinrichs, T. S. Furey, K. M. Roskin, C. W. Sugnet et al., 2004. The UCSC Table Browser data retrieval tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 32 D493–D496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent, W. J., 2002. BLAT: the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 12 656–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent, W. J., C. W. Sugnet, T. S. Furey, K. M. Roskin, T. H. Pringle et al., 2002. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 12 996–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent, W. J., R. Baertsch, A. Hinrichs, W. Miller and D. Haussler, 2003. Evolution's cauldron: duplication, deletion, and rearrangement in the mouse and human genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100 11484–11489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidwell, M. G., and D. R. Lisch, 2001. Perspective: transposable elements, parasitic DNA, and genome evolution. Evolution Int. J. Org. Evolution 55 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagos-Quintana, M., R. Rauhut, W. Lendeckel and T. Tuschl, 2001. Identification of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs. Science 294 853–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander, E. S., L. M. Linton, B. Birren, C. Nusbaum, M. C. Zody et al., 2001. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature 409 860–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau, N. C., L. P. Lim, E. G. Weinstein and D. P. Bartel, 2001. An abundant class of tiny RNAs with probable regulatory roles in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 294 858–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R. C., and V. Ambros, 2001. An extensive class of small RNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 294 862–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R. C., R. L. Feinbaum and V. Ambros, 1993. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 75 843–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. C., C. Y. Pan and W. C. Lin, 2006. Bioinformatic discovery of microRNA precursors from human ESTs and introns. BMC Genomics 7 164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindow, M., and A. Krogh, 2005. Computational evidence for hundreds of non-conserved plant microRNAs. BMC Genomics 6 119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippman, Z., A. V. Gendrel, M. Black, M. W. Vaughn, N. Dedhia et al., 2004. Role of transposable elements in heterochromatin and epigenetic control. Nature 430 471–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, M., 2007. The Origins of Genome Architecture. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA.

- Mariño-Ramirez, L., and I. K. Jordan, 2006. Transposable element derived DNaseI-hypersensitive sites in the human genome. Biol. Direct 1 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariño-Ramirez, L., K. C. Lewis, D. Landsman and I. K. Jordan, 2005. Transposable elements donate lineage-specific regulatory sequences to host genomes. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 110 333–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick, J. S., and I. V. Makunin, 2006. Non-coding RNA. Hum. Mol. Genet. 15 Spec. No. 1: R17–R29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzke, M. A., M. F. Mette and A. J. Matzke, 2000. Transgene silencing by the host genome defense: implications for the evolution of epigenetic control mechanisms in plants and vertebrates. Plant Mol. Biol. 43 401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, J. F., M. A. Matzke and A. J. Matzke, 2005. Host defenses to transposable elements and the evolution of genomic imprinting. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 110 242–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mette, M. F., J. van der Winden, M. Matzke and A. J. Matzke, 2002. Short RNAs can identify new candidate transposable element families in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 130 6–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, W. J., S. Hagemann, E. Reiter and W. Pinsker, 1992. P-element homologous sequences are tandemly repeated in the genome of Drosophila guanche. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89 4018–4022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam, J. W., K. R. Shin, J. Han, Y. Lee, V. N. Kim et al., 2005. Human microRNA prediction through a probabilistic co-learning model of sequence and structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 33 3570–3581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishihara, H., A. F. Smit and N. Okada, 2006. Functional noncoding sequences derived from SINEs in the mammalian genome. Genome Res. 16 864–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orgel, L. E., and F. H. Crick, 1980. Selfish DNA: the ultimate parasite. Nature 284 604–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquinelli, A. E., B. J. Reinhart, F. Slack, M. Q. Martindale, M. I. Kuroda et al., 2000. Conservation of the sequence and temporal expression of let-7 heterochronic regulatory RNA. Nature 408 86–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, J. S., G. Bejerano, A. Siepel, K. Rosenbloom, K. Lindblad-Toh et al., 2006. Identification and classification of conserved RNA secondary structures in the human genome. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2 e33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piriyapongsa, J., and I. K. Jordan, 2007. A family of human microRNA genes from miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements. PLoS ONE 2 e203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, K. S., S. R. Salama, B. King, A. D. Kern, T. Dreszer et al., 2006. a Forces shaping the fastest evolving regions in the human genome. PLoS Genet. 2 e168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, K. S., S. R. Salama, N. Lambert, M. A. Lambot, S. Coppens et al., 2006. b An RNA gene expressed during cortical development evolved rapidly in humans. Nature 443 167–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar, S., J. P. Noonan, S. Paabo and E. M. Rubin, 2006. Accelerated evolution of conserved noncoding sequences in humans. Science 314 786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart, B. J., F. J. Slack, M. Basson, A. E. Pasquinelli, J. C. Bettinger et al., 2000. The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 403 901–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siepel, A., G. Bejerano, J. S. Pedersen, A. S. Hinrichs, M. Hou et al., 2005. Evolutionarily conserved elements in vertebrate, insect, worm, and yeast genomes. Genome Res. 15 1034–1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva, J. C., S. A. Shabalina, D. G. Harris, J. L. Spouge and A. S. Kondrashovi, 2003. Conserved fragments of transposable elements in intergenic regions: evidence for widespread recruitment of MIR- and L2-derived sequences within the mouse and human genomes. Genet. Res. 82 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin, R. K., M. Freeling and D. Lisch, 2005. Heritable transposon silencing initiated by a naturally occurring transposon inverted duplication. Nat. Genet. 37 641–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smalheiser, N. R., and V. I. Torvik, 2005. Mammalian microRNAs derived from genomic repeats. Trends Genet. 21 322–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smalheiser, N. R., and V. I. Torvik, 2006. Alu elements within human mRNAs are probable microRNA targets. Trends Genet. 22 532–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit, A. F. A., R. Hubley and P. Green, 1996–2004 RepeatMasker Open-3.0 (http://www.repeatmasker.org).

- Sood, P., A. Krek, M. Zavolan, G. Macino and N. Rajewsky, 2006. Cell-type-specific signatures of microRNAs on target mRNA expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103 2746–2751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark, A., J. Brennecke, N. Bushati, R. B. Russell and S. M. Cohen, 2005. Animal MicroRNAs confer robustness to gene expression and have a significant impact on 3′UTR evolution. Cell 123 1133–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltzfus, A., 2006. Mutationism and the dual causation of evolutionary change. Evol. Dev. 8 304–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturn, A., J. Quackenbush and Z. Trajanoski, 2002. Genesis: cluster analysis of microarray data. Bioinformatics 18 207–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su, A. I., T. Wiltshire, S. Batalov, H. Lapp, K. A. Ching et al., 2004. A gene atlas of the mouse and human protein-encoding transcriptomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101 6062–6067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torarinsson, E., M. Sawera, J. H. Havgaard, M. Fredholm and J. Gorodkin, 2006. Thousands of corresponding human and mouse genomic regions unalignable in primary sequence contain common RNA structure. Genome Res. 16 885–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Lagemaat, L. N., J. R. Landry, D. L. Mager and P. Medstrand, 2003. Transposable elements in mammals promote regulatory variation and diversification of genes with specialized functions. Trends Genet. 19 530–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vastenhouw, N. L., and R. H. Plasterk, 2004. RNAi protects the Caenorhabditis elegans germline against transposition. Trends Genet. 20 314–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volff, J. N., 2006. Turning junk into gold: domestication of transposable elements and the creation of new genes in eukaryotes. BioEssays 28 913–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washietl, S., I. L. Hofacker and P. F. Stadler, 2005. Fast and reliable prediction of noncoding RNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102 2454–2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X., M. Kamal and E. S. Lander, 2006. A family of conserved noncoding elements derived from an ancient transposable element. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103 11659–11664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder, J. A., C. P. Walsh and T. H. Bestor, 1997. Cytosine methylation and the ecology of intragenomic parasites. Trends Genet. 13 335–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B., D. Schmoyer, S. Kirov and J. Snoddy, 2004. GOTree Machine (GOTM): a web-based platform for interpreting sets of interesting genes using Gene Ontology hierarchies. BMC Bioinformatics 5 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z., and M. Gerstein, 2003. Of mice and men: phylogenetic footprinting aids the discovery of regulatory elements. J. Biol. 2 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]