Abstract

Hydroxyurea (HU), a drug effective in the treatment of sickle cell disease, is thought to indirectly promote fetal hemoglobin (Hb F) production by perturbing the maturation of erythroid precursors. The molecular mechanisms involved in HU-mediated regulation of γ-globin expression are currently unclear. We identified an HU-induced small guanosine triphosphate (GTP)–binding protein, secretion-associated and RAS-related (SAR) protein, in adult erythroid cells using differential display. Stable SAR expression in K562 cells increased γ-globin mRNA expression and resulted in macrocytosis. The cells appeared immature. SAR-mediated induction of γ-globin also inhibited K562 cell growth by causing arrest in G1/S, apoptosis, and delay of maturation, cellular changes consistent with the previously known effects of HU on erythroid cells. SAR also enhanced both γ- and β-globin transcription in primary bone marrow CD34+ cells, with a greater effect on γ-globin than on β-globin. Although up-regulation of GATA-2 and p21 was observed both in SAR-expressing cells and HU-treated K562 cells, phosphatidylinositol 3 (PI3) kinase and phosphorylated ERK were inhibited specifically in SAR-expressing cells. These data reveal a novel role of SAR distinct from its previously known protein-trafficking function. We suggest that SAR may participate in both erythroid cell growth and γ-globin production by regulating PI3 kinase/extracellular protein–related kinase (ERK) and GATA-2/p21-dependent signal transduction pathways.

Introduction

Hydroxyurea (HU), a ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor and an S-phase–specific cytotoxic agent, has been successfully used in the clinic to treat sickle cell disease because it augments the production of fetal hemoglobin (Hb F).1,2 In a multicenter study of HU in sickle cell anemia (MSH), HU treatment dramatically reduced the frequency of hospitalization due to the incidence of pain, acute chest syndrome, and the blood transfusion requirements in patients with sickle cell disease.2 After 2 years of HU treatment, Hb F levels increased from 5% of total Hb to 9% in the majority of patients.2 Similarly, as Hb F levels became elevated after HU treatment, the rate and extent of sickle hemoglobin (Hb S) polymerization appeared to be reduced.1 A 9-year follow-up of 233 patients in the original MSH cohort indicated, among other findings, that taking HU was associated with a 40% reduction in mortality.3

Several mechanisms have been proposed to account for the induction of Hb F by HU. Because HU directly kills late erythroid progenitor cells and triggers rapid erythroid regeneration,4 HU has been assumed to promote Hb F production by perturbing the maturation of erythroid precursors. Accelerated erythropoiesis increases the chance of premature lineage commitment and the induction of F-cell formation.5 HU also increases erythropoietin (EPO) production and enhances the proliferation of erythroid precursors and their ability to synthesize Hb F.6 HU could effectively stimulate erythropoiesis and production of Hb F through multiple mechanisms.7 It has been reported that induction of Hb F by HU is mediated by up-regulation of GATA-2 and down-regulation of GATA-1.7,8 Recent studies from our laboratory have also demonstrated that, in addition to regulating GATA expression, HU also induces expression of genes related to the cell cycle and apoptosis; the actions of HU depend upon its concentration.7 Induction of peroxidation by HU can generate nitric oxide (NO),9,10 a known inducer of soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC), which, in turn, can modulate the expression of γ-globin.11 However, the molecular mechanisms by which HU regulates γ-globin gene expression need to be further elucidated. To elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the HU-induced elevation of Hb F and to explore new signal transduction pathways related to HU-mediated hemoglobin gene expression, we used mRNA differential display to identify HU inducible gene(s) in human adult erythroid cells. Here, we identify a new small guanosine triphosphate (GTP)–binding protein, secretion-associated and RAS-related (SAR) protein, as a specific HU-inducible gene.

The small GTP-binding protein superfamily comprises more than 100 members in eukaryocytes.12,13 Members of the SAR/adenosine diphosphate (ADP) ribosylation factor (Arf) family are GTPases14-16 active in protein trafficking and maturation.17 SAR itself functions in cargo selection and export of proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi via the cytosolic coat protein complex II (COPII) secretory pathway. It has been reported that several Ras superfamily members participate in hematopoietic cell proliferation and differentiation processes involving endo- and exocytosis or cell adhesion.18-21 However, it is unknown whether SAR participates in hemoglobin gene regulation, and which signal transduction pathway SAR uses. Here, we demonstrate that HU-induced SAR plays a pivotal role in γ-globin gene induction by causing cell apoptosis and G1/S-phase arrest through the reduction of phosphatidylinositol 3 (PI3) kinase and extracellular protein–related kinase (ERK) phosphorylation and increased p21 and GATA-2 expression. Localization of SAR in the endoplasmic reticulum was also confirmed.

Materials and methods

Cell cultures

Two-phase liquid cultures of human adult erythroid cells (HAECs) were prepared from the peripheral blood of healthy donors. Mononuclear cells were isolated by centrifugation over Ficoll-Hypaque (1.077 g/mL; Organon Teknika, Durham, NC), washed twice with Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and cultured according to a previously published 2-phase liquid culture protocol.22 Cells were treated with 100 μM HU on days 7 and 8, and RNA was collected on day 10 of phase II culture for differential display. K562 cells grew in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) plus 4 mM glutamine, 10 U/mL penicillin, and 10 μg/mL streptomycin. Growth curves were performed by seeding cells at a density of 2.5 × 104 cells/mL, then counting them every 24 hours for 4 days. The morphology of K562 cells was observed after hematoxylin and eosin staining. Enriched primary bone marrow AC133+ cells and CD34+ cells were purchased from Poietic Technologies (Gaithersburg, MD) and cultured according to a previously described protocol.23

Molecular cloning of the SAR gene using differential display

Differential display was performed using an RNA Image Kit (GeneHunter, Nashville, TN). We used a MessageClean DNase I kit (GeneHunter) to eliminate chromosomal DNA from total RNA before differential display experiments. Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) followed the manufacturer's protocol. Reproducible differential bands were excised and eluted by boiling the gel slices for 15 minutes. Eluted DNA was reamplified using the same primer set, purified, and cloned into the PCR II TOPO vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for sequencing. The human SAR gene was cloned by 5′- and 3′-RACE (rapid amplification of cDNA ends) with the Marathon cDNA Amplification Kit using bone marrow Ready Marathon cDNA (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). Homology searches of GenBank and expressed sequence tag (EST) databases were performed using GCG software (Genetics Computer Group, Madison, WI).

SAR protein expression in vitro

A full-length SAR cDNA was cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI), then transcribed and translated into a sulfur 35 (35S)–labeled peptide using a TNT Quick T7-coupled transcription/translation system (Promega) with [35S]-methionine (555 MBq/mL [15 mCi/mL], Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). The translation product was subjected to electrophoresis in 4%-12% Bis-Tris ([bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]tris(hydroxymethyl)methane) gels. The gels were exposed to film to determine the size of the translated product by comparison with known protein standards.

Northern and Western blotting

A SAR cDNA probe was hybridized to Multiple Tissue Northern (MT) Blots (Clontech) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Membranes were stripped between probes by incubating the blots in sterile 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) solution at 95°C for 10 minutes. The Human Cell Cycle filter membrane containing various human cDNA sequences was purchased (Superarray, Frederick, MD). For hybridization probes, 5 μg of total RNA from K562 cells transfected with SAR or with vector alone was converted to cDNA by random hexamer labeling with Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) reverse transcriptase and [33P]–deoxycytidine triphosphate (dCTP) (370 MBq/mL; NEN Life Sciences, Boston, MA), according to the protocol provided by the supplier. The filter arrays were scanned in a Fuji BAS-1500 phosphoimager (Fuji, Stamford, CT). Before quantitative analysis, hybridization signals for each probe were normalized using GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) cDNAs as reference controls. For Western blots, cell lysates containing 50 μg protein were loaded on Tris-glycine gels (Invitrogen), transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Invitrogen), and then immunoblotted with antibodies to PI3 kinase (BD Bioscience, Palo Alto, CA), phospho- and total ERK, GATA-1, and GATA-2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) for 1 hour. Washing and detection using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) Western Blotting Analysis System (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Powerblot screen

Proteins were separated on 4% to 15% gradient SDS–polyacrylamide gel and transferred onto Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA). After transfer, the membrane was dried and re-wet in methanol, then blocked for 1 hour with blocking buffer (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE). Next, the membrane was clamped with a Western blotting manifold that isolated 41 channels across the membrane. In each channel, a complex antibody cocktail was added and allowed to hybridize for 1 hour at 37°C. The blot was washed and hybridized for 30 minutes at 37°C with secondary goat antimouse conjugated to Alexa680 fluorescent dye (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). The membrane was washed, dried, and scanned at 700 nm using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR). The bands were identified, and molecular masses were assessed using specialized software. Each observed band, where possible, was manually matched against the expected molecular mass of a protein recognized by an individual antibody in the mixture.

Transfection and gene expression of SAR in K562 cells

We cloned the SAR cDNA into pEF6/V5-His-TOPO (Invitrogen) and stably transfected it into K562 cells by electroporation (Amaxa Biosystems, Cologne, Germany). Stable SAR-expressing clones were selected by culturing the cells in 6 μg/mL blasticidin for 2 weeks. An antibody directed against the His tag was used to identify high and low levels of SAR by Western blotting; expression was confirmed by Northern blotting and RT-PCR.

Retrovirus generation and gene transduction in CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells

The SAR coding region with a green fluorescent protein (GFP) tag at the 3′ end or GFP alone was subcloned into the murine stem cell virus (MSCV) retroviral expression vector (Clontech). The retroviruses were packaged into PT67 packaging cells. The viral titers were determined and high-titer viral clones were selected. For SAR transduction in CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells, 2 × 106 viral particles were preloaded onto a RetroNectin-coated plate (Takara Shuzo, Kyoto, Japan) and incubated at 37°C for 5 hours. Just prior to infection, the viral supernatant was discarded and the plate was washed with PBS; 1 × 105 CD34+ cells were then added to the preloaded viral plate with growth medium, and the plate was incubated at 37°C. This procedure was repeated twice at 24-hour intervals. On day 7, the infected CD34+ cells were subjected to GFP sorting, and GFP-positive CD34+ cells were selected and cultured. The sorted cells were harvested on day 10, day 14, and day 18 for further analysis.

RNA isolation, RT-PCR, and real-time PCR

RNA was isolated with Tri Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH) according to the manufacturer's recommended protocol. RT-PCR was carried out using SuperScript reverse transcriptase and Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR primer pairs were as follows: γ-globin sense (SN): 5′-AAGATGCTGGAGGAGAAAC-3′, antisense (ASN): 5′-TGCTTGCAGAATAAAG CC-3′; SAR SN 5′-CAATATCCAATGTGCCAATCCTTA-3′, ASN 5′-GAAAACCCTCGCC GTACCTT3′; GAPDH SN 5′-SN TGAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTTGGT-3′, ASN 5′-CATGTGGGCCATGAGGTCCACCAC-3′; Glycophorin C (GlyC) SN: 5′-TGGGG AAGCAAGGAAATAAG-3′; ASN 5′-AGCTGGATCAATGGCAGAC-3′. Real-time PCR was accomplished with Platinum QPCR SuperMix-UDG (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The γ-globin and β-globin gene primers and probe sequences were published previously24; control β-actin primers and probe were ordered from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA).

Cellular localization of SAR protein

GFP was tagged onto the 3′ end of the SAR coding region by cloning it into the pGFP-N1 vector (Clontech); the resulting construct was transfected into K562 cells by electroporation. After 8 hours or 18 hours of culture in fresh medium, transfectants were collected and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Cells were then washed 3 times before being cytospinned onto glass slides. The cells were then incubated with an anticalreticulin antibody (Affinity Bioreagent, Golden, CO) for 4 hours and antirabbit antibody for 1 hour before being visualized under a Zeiss TV200 confocal fluorescence microscope with a × 100 objective (1.4 NA). Emission wavelengths were 488 nm and 567 nm for fluoroscein isothiocyanate (FITC) and rhodamine, respectively. The images were collected on an ORCA ER CCD (Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ). Images were acquired and analyzed using Improvision Software (Improvision, Lexington, MA).

Cell cycle and apoptosis analysis

Cells were counted and centrifuged at 207 g for 5 minutes. The cell pellets were resuspended at a density of 0.5 to 1.0 × 106 cells/mL; 400 μL Quickstain solution (FAST Systems, Gaithersburg, MD) was then added to each sample, and the samples were incubated in darkness for 30 minutes at 22 to 28°C. We used flow cytometry (EPICS-XL Model; Beckman Coulter, Hialeah, FL) with signal acquisition at 675 nm to determine cell-cycle distributions. Laser excitation was at 488 nm; emission filters for FITC and propidium iodide were 525 nm and 630 nm, respectively. The terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated dUTP (deoxyuridine triphosphate) nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay for cell apoptosis was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol (Promega). The images were acquired with a fluorescence microscope system (Axioplan 2; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Thornwood, NY) with a 20 ×/0.75 NA objective and a Zeiss Axiocam HRc real-color CCD camera. Acquisition software is AxioVision 4.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis of the results were obtained using the Student t test for significance of the difference of individual pairs and the Pearson of correlation coefficient for the closeness of linear relationship.25

Results

Molecular cloning, SAR protein production, and localization in erythroid cells

In vivo studies have shown that continuous infusion of 20 mg/kg HU into patients maintains a serum concentration of HU at 100 μM.26 In order to obtain an exposure regimen for the differential display study that closely resembled the in vivo pharmacokinetics of HU treatment in patients, HAECs were treated with 100 μMHU on day 7 and day 8, and RNA was collected on day 10. A reverse dot blot was used to confirm differential expression, and one particular transcript was identified that was significantly induced in response to HU treatment. This gene had 92% similarity to the mouse small GTP–binding protein SAR1 by sequence analysis. We then obtained the full-length human SAR cDNA sequence (2878 base pair [bp]) by screening a bone marrow library with 5′-and 3′-RACE. The human SAR gene was mapped to chromosome 10q22 using a National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) genomic data search. Alignment of the cDNA with the chromosome 10 genomic sequence (Celera Discovery System, Rockville, MD) revealed that the SAR gene contains 8 exons and 7 introns. Sequence analysis showed a 599-bp open reading frame that includes 3 GTP binding motifs.

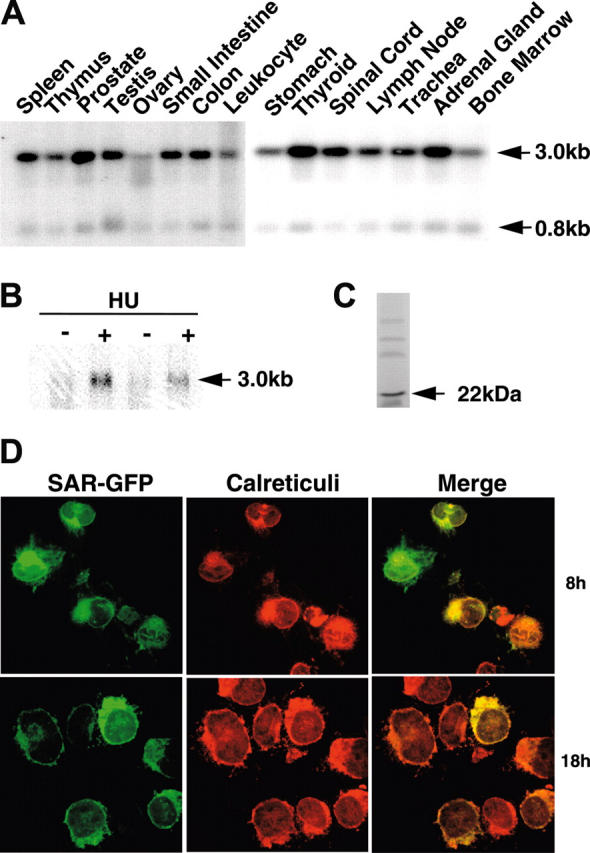

Human multiple-tissue RNA blots probed with the SAR cDNA revealed transcripts of 3.0 and 0.8 kilobase (kb) in most tissues. SAR mRNA was abundant in glandular tissues, such as prostate, thyroid, and adrenal gland. In contrast, relatively low levels were found in spleen, small intestine, spinal cord, lymph node, and trachea, and very low levels were detected in leukocytes, bone marrow, and ovary (Figure 1A). SAR mRNA was barely detectable in primary cultures of HAECs, but increased by at least 4-fold after 48 hours of 100 μM HU treatment (Figure 1B). In vitro transcription and translation of full-length SAR cDNA produced a single 22-kDa peptide (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

SAR mRNA expression in different tissues and HU induction of SAR. (A) mRNA blots of multiple human tissues were hybridized with a 32P-labeled SAR-specific probe. (B) Human adult erythroid cells were treated with (+) or without (-) 100 μM HU, as detailed in “Materials and methods.” Total RNA was isolated on day 10 and probed for SAR mRNA by Northern blotting. (C) In vitro transcription/translation of the SAR protein produced a 22-kDa peptide. (D) Cellular localization of SAR tagged with GFP at the 3′ end in SAR-transfected K562 cells. Green indicates GFP fluorescence; red indicates staining for calreticulin, which indicates the endoplasmic reticulum; yellow (in the merged image) represents overlapping green and red fluorescence. Cells were incubated for 8 or 18 hours.

To localize SAR expression within cells, we transiently transfected GFP-tagged SAR (SAR-GFP) cDNA into the K562 cells. Cells were fixed after transfection, and then incubated with an anticalreticulin antibody for comparison with the SAR-GFP localization; calreticulin is expressed exclusively in the endoplasmic reticulum. Under a confocal fluorescence microscope, the SAR-GFP signal appeared predominantly in the cytoplasmic and perinuclear areas (Figure 1D). K562 cells transfected with GFP alone showed primarily nuclear fluorescence (data not shown). The SAR-GFP colocalized with calreticulin, suggesting that SAR was present in the endoplasmic reticulum, as expected from SAR's known protein-trafficking function.

SAR-induced γ-globin gene expression in K562 cells

To determine whether and how SAR regulates γ-globin gene expression in human erythroid cells, we stably transfected SAR into K562 cells and then analyzed multiple SAR-expressing and vector-transfected clones. Northern blotting revealed significantly higher γ-globin mRNA levels in SAR-transfected cells than in vector-transfected cells (Table 1). To better clarify the correlation between SAR and γ-globin expression, we divided the SAR-expressing cells into 2 groups: clones with high γ-globin gene expression (> 2-fold induction) and clones with lower γ-globin gene expression (< 2 fold induction). As shown in Table 1, both groups had significant induction of γ-globin mRNA compared with the vector control (P < .001), ranging from a 1.5-fold to a 4.3-fold increase in γ-globin mRNA levels. On average, SAR-expressing clones had 3.5-fold higher levels of γ-globin mRNA than vector controls. Coexistence of SAR mRNA and high levels of γ-globin mRNA in K562 cells indicate that HU-induced SAR may be involved in γ-globin mRNA induction in erythroid cell development.

Table 1.

γ-globin gene expression in stable transfected clones

| Gamma increase, fold* | |

|---|---|

| Low gamma-expressing clones† | |

| No. 1 | 1.24 |

| No. 2 | 1.39 |

| No. 3 | 1.73 |

| No. 4 | 1.40 |

| No. 5 | 1.21 |

| Average (SD) | 1.40 (0.34) |

| High gamma-expressing clones‡ | |

| No. 1 | 4.78 |

| No. 2 | 5.21 |

| No. 3 | 3.33 |

| No. 4 | 3.50 |

| No. 5 | 2.23 |

| Average (SD) | 3.81 (1.53) |

| Vector-only clones | |

| No. 1 | 0.93 |

| No. 2 | 0.68 |

| No. 3 | 0.81 |

| No. 4 | 1.04 |

| No. 5 | 0.60 |

| No. 6 | 1.20 |

| Average (SD) | 0.88 |

Fold increase compared with k562 cells

P compared with vector clones = .003

P compared with vector clones = .005

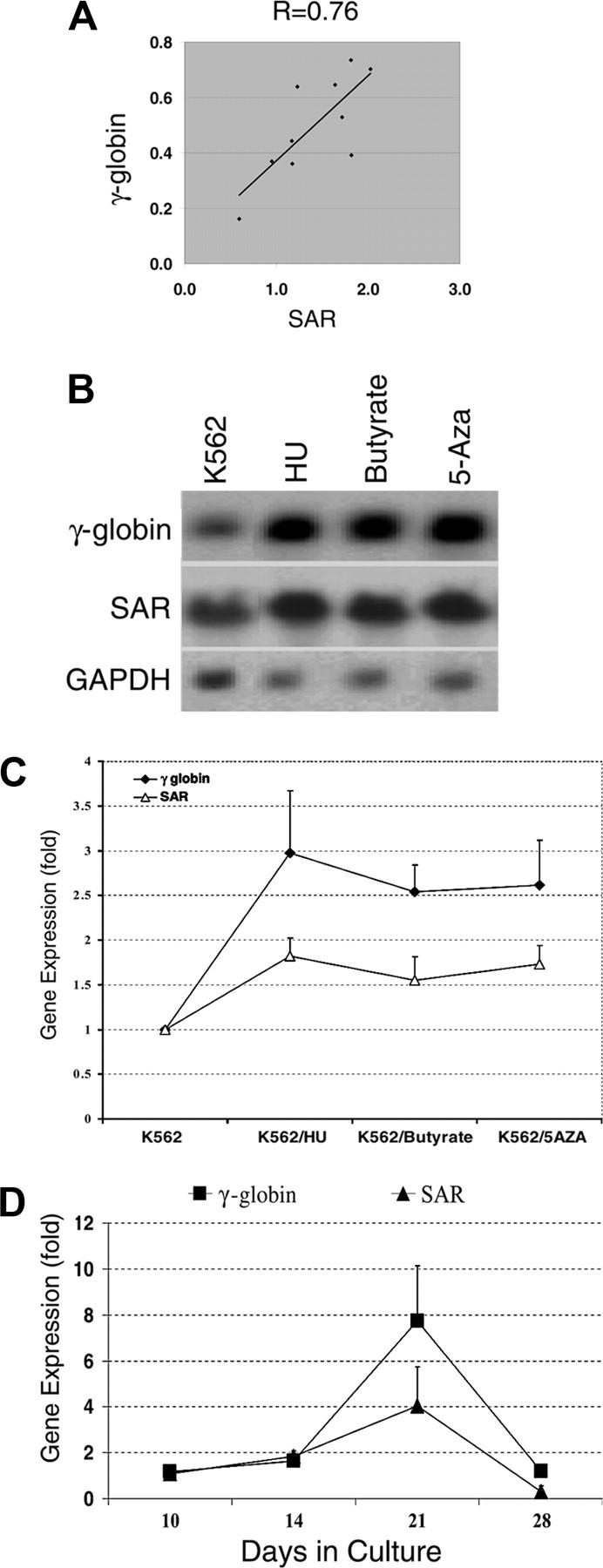

To investigate whether SAR is a common or specific inducer for the γ-globin gene, we designed 3 sets of experiments. First we used semi-quantitative RT-PCR to analyze and correlate SAR and γ-globin mRNA levels in SAR-expressing K562 cells; we found a correlation coefficient of 0.76 between SAR and γ-globin mRNA levels (Figure 2A). Second, when parental K562 cells were treated with various hemoglobin gene inducers (hydroxyurea, butyrate, and 5-azacytidine) for 48 hours, a Northern blot indicated that all 3 inducers up-regulated γ-globin mRNA, from 2.5-fold for butyrate to 3.0-fold for hydroxyurea. In the same experiment, SAR mRNA increased in parallel with the γ-globin mRNA, from 1.5-fold after butyrate treatment to 2.1-fold after hydroxyurea (Figure 2B-C). Third, the expression of SAR and γ-globin mRNA in cultured primary bone marrow AC133+ cells was determined by RT-PCR at different time points. In the presence of EPO, both SAR and γ-globin mRNA began to be expressed at day 10, reached a peak at day 21, and declined to baseline at day 28, reflecting a similar time course and pattern of gene expression (Figure 2D). These data further indicate that there is a close temporal relation between SAR and γ-globin mRNA expression in primary bone marrow cells, and strongly suggest that the SAR and γ-globin genes coexist in cells of this erythroid lineage.

Figure 2.

SAR and γ-globin gene expression in SAR transfectants, K562 cells treated with globin inducers, and AC133+ cells. (A) Correlation of γ-globin and SAR mRNA. The diagonal line shows trend line. γ-globin (Gamma) and SAR mRNA levels were normalized to glycophorin C determined by quantitative RT-PCR in SAR-transfected K562 cells. (B) Northern blot analysis of γ-globin and SAR mRNA expression in K562 cells 48 hours after treatment with HU, butyrate, or 5-azacytidine, as detailed in “Materials and methods.” GAPDH was used as an internal control. (C) Quantitative analysis of γ-globin and SAR mRNA levels normalized to GAPDH from Northern blots. (D) RT-PCR determination of SAR and γ-globin mRNA expression (normalized to GAPDH) in AC133+ cells (with EPO) cultured for the indicated amounts of time. Error bars indicate standard deviation of the mean of 3 independent experiments.

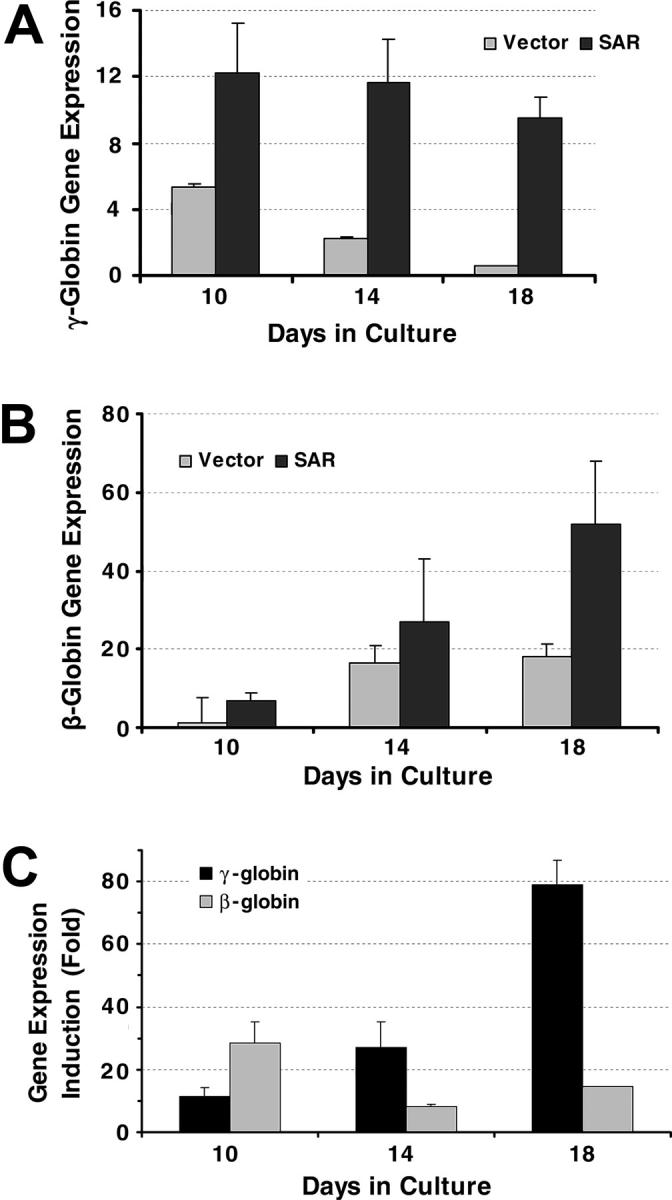

SAR-induced hemoglobin gene expression in CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells

We next investigated the effects of SAR using primary bone marrow stem cells. A SAR-GFP fusion construct was produced using the pMSCV retroviral expression system. A pure population of SAR-infected CD34+ stem cells was obtained after cell sorting. Both γ- and β-globin mRNA transcripts were measured dynamically using real-time PCR (Figure 3A-B). SAR enhanced both γ-globin and β-globin mRNA expression in the CD34+ stem cells, but the effects on γ-globin were larger and more sustained than the effects on β-globin (Figure 3C). SAR enhanced γ-globin gene expression 3-fold at day 10, 5.4-fold at day 14, and 15.8-fold at day 18 in SAR-infected CD34+ cells, compared with 5.7-fold at day 10, 1.6-fold at day 14, and 2.9-fold at day 18 for β-globin mRNA induction.

Figure 3.

γ-globin and β-globin gene transcription in CD34+ cells determined by real time PCR. (A) γ-globin gene expression in CD34+ cells infected with an SAR retrovirus and vector control cells, normalized with β-actin gene. (B) β-globin genes expression in CD34+ cells infected with an SAR retrovirus and vector control cells, normalized with β-actin gene. (C) Comparison of SAR effect on γ-globin and β-globin genes in SAR-expressing CD34+ cells, shown as fold increase compared with vector control cells. Error bars indicate standard deviation of the mean of 3 independent experiments.

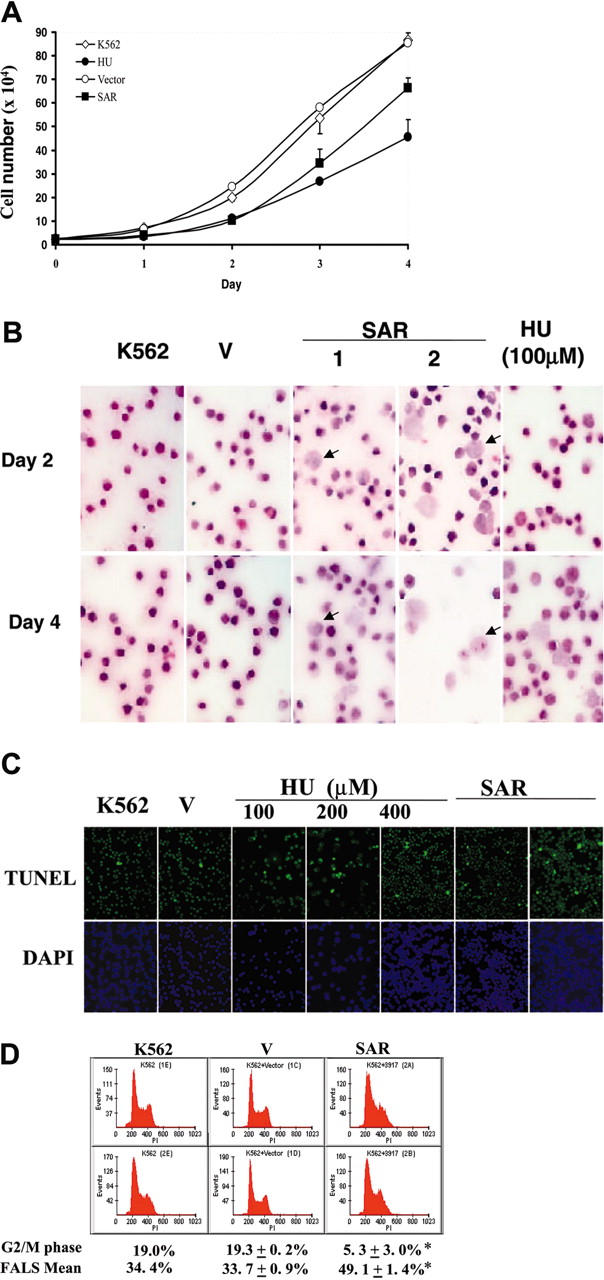

G1/S phase accumulation and apoptosis in SAR-expressing cells

We also noted that SAR-transfected K562 cells grew more slowly than vector-transfected controls. Parental and vector-transfected cells doubled in approximately 18 hours, compared with 30 hours in SAR transfectants (Figure 4A). Hematoxylin and eosin staining of these cells showed the existence of many enlarged cells. The nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio was increased in some of these cells, which also exhibited macrocytic morphology, implying that SAR delayed erythroid maturation. HU-treated K562 cells had similar morphologic features, particularly after 4 days of HU treatment (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Effects of HU and SAR expression on K562 cell growth. (A) Growth curve generated as described in “Materials and methods.” ⋄ indicates parental K562 cells; •, HU-treated parental K562 cells; ○, vector-transfected cells; and ▪, SAR-expressing cells. Cell-doubling times were calculated from the graph. (B) Enforced expression of SAR (2 clones are shown) led to dramatic macrocytosis and a relatively immature appearance in some K562 cells, as seen with hematoxylin and eosin staining. HU-treated parental cells are also shown (HU). (C) A sizable fraction of SAR transfectants underwent apoptosis, as shown by TUNEL assays. Apoptotic cells are stained green; the nuclei of cells stained with DAPI are blue. Similarly, K562 cells treated with HU for 24 hours showed some apoptotic cells. (D) Cell-cycle and FACS analysis. SAR-expressing cells were arrested in G1/S phase and showed a decreased G2/M fraction. Cell-cycle analysis was performed after cells were plated for 48 hours. Error bars indicate standard deviation of the mean of 3 independent experiments.

HU not only causes apoptosis in K562 cells, it also up-regulates apoptosis-related molecules.7 As expected, the incidence of apoptosis was notably higher in SAR-expressing K562 clones than in vector controls. A TUNEL assay showed that a sizable fraction of SAR-expressing cells underwent apoptosis (Figure 4C). This fact and the prolonged doubling time in SAR-expressing cells indicate that the cell cycle might be impacted due to the forced SAR expression. As shown in Figure 4D, the percentage of cells in G2/M decreased from 19.3 ± 0.2% in vector-transfected cells) to 5.3 ± 3.0% in SAR transfectants, while the G1/S phase fraction increased to 21% in SAR-expressing cells, suggesting that SAR-expressing cells accumulate in G1 and S phase. By measuring the forward angle light scatter (FALS), an indicator of cell volume, we observed a significant increase in SAR-expressing cells (49.1 ± 1.4%) compared with vector-transfected cells (33.7 ± 0.9%) (P < .05). The effects on cell volume and G1/S accumulation by SAR were again consistent with the known effects of HU on erythroid cells.

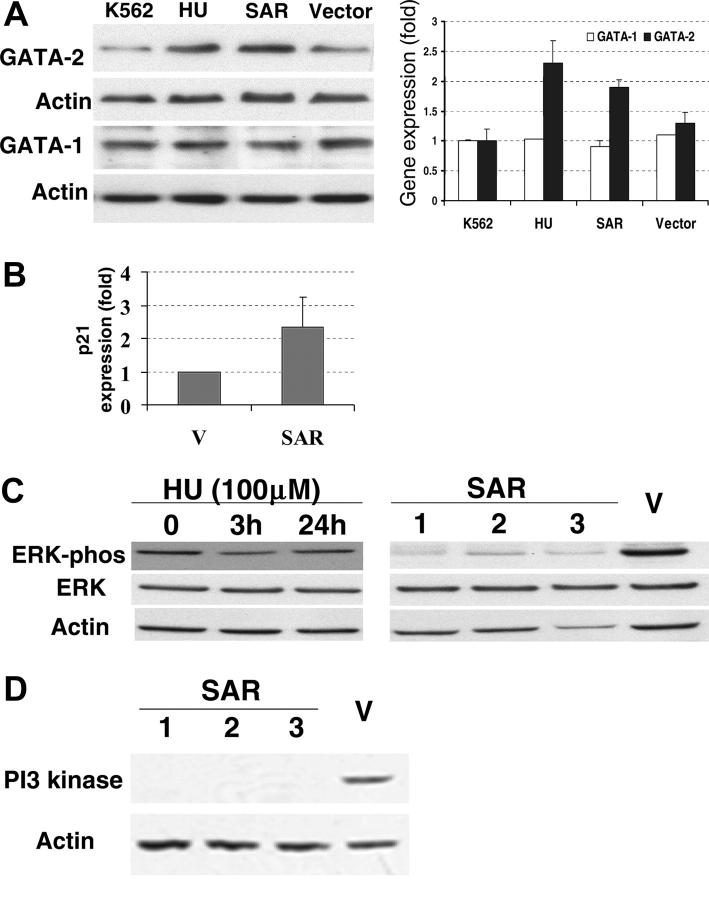

Increased protein levels of GATA-2 and p21 in SAR-expressing K562 cells

The erythroid transcription factors GATA-1 and GATA-2 are considered to be active modulators of γ-globin gene expression.7,8 We therefore investigated the GATA-1 and GATA-2 proteins in SAR-expressing K562 cells with Western blots. GATA-2 protein levels, but not GATA-1, were significantly elevated in these cells compared with vector controls (P < .05; Figure 5A). In the same experiment, similar effects on GATA-1 and GATA-2 protein levels were observed in K562 cells after 3 days of HU treatment. Interestingly, p21 mRNA was also elevated 2.4-fold in SAR-expressing cells compared with the vector control (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Expression of GATA-1, GATA-2, ERK, and PI3 kinase proteins, and p21 mRNA in parental and SAR-transfected K562 cells. (A) Comparison of GATA-1 and GATA-2 protein levels in parental K562 cells (grown in the presence or absence of HU for 3 days), vector-transfected cells, and SAR-expressing cells. Left panel shows Western blot; right panel, fold increase over untransfected K562 cells. (B) p21 mRNA levels in SAR-expressing cells and vector controls detected by hybridization. (C) Total and phosphorylated ERK in SAR transfectants and K562 cells treated with HU for 3 days. (D) PI3 kinase protein in SAR-transfected and vector control K562 cells. Samples containing 50 μg protein were subjected to electrophoresis on Tris-glycine gels and to Western blotting with antibodies directed against either phosphorylated ERK, total ERK, or PI3 kinase. Error bars indicate standard deviation of the mean of 3 independent experiments.

Decreased ERK phosphorylation and PI3 kinase accompanied SAR overexpression

Because there was observable growth inhibition in SAR-expressing cells, overexpressing SAR may impact growth-related signals. It has been reported that the inhibition of Ras/ERK enhances erythroid cell differentiation.27 Therefore, we examined mitogen- and stress-activated signaling molecules in the SAR-expressing cells and vector controls. Interestingly, phospho-ERK (pERK) levels, but not total ERK protein, decreased in all 3 SAR-transfected clones compared with vector-transfected cells (Figure 5C). In contrast, neither the phosphorylation state nor the total level of p38 protein was altered in response to SAR expression (data not shown). ERK phosphorylation transiently decreased after 3 hours of exposure to 100 μM HU in K562 cells, but returned to baseline by 24 hours. By using a PowerBlot screen (BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Jose, CA), we also found that the most significant protein change was an 11-fold reduction of PI3 kinase in SAR-expressing clones compared with vector controls. This result was further confirmed by Western blot (Figure 5D).

Discussion

Using differential display, we identified the small GTP-binding protein SAR as an HU-inducible gene. The induction of γ-globin mRNA by HU was correlated with an increase of SAR mRNA in human erythroid cells, leading us to hypothesize that SAR is a specific factor involved in γ-globin production after HU treatment. This hypothesis is supported by (1) the induction of SAR mRNA by HU in both HAECs and K562cells; (2) the induction of γ-globin in both K562 cells and CD34+ cells expressing SAR; (3) the correlation of SAR and γ-globin mRNA expression in SAR-transfected K562 cells; (4) parallel increases in mRNA levels for both genes in response to 3 γ-globin gene inducers in K562 cells; and (5) parallel induction of both γ-globin and SAR mRNA in AC133+ cells cultured with EPO. These observations indicate that the effects of SAR expression in hematopoietic cells not only closely resemble the effects of HU in these cells, but also that the induction of SAR is a specific event in the HU-induced enhancement of γ-globin production.

SAR has long been known to participate in protein trafficking from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi complex.16,17 The localization of SAR in the endoplasmic reticulum and its association with γ-globin gene expression demonstrated in this study suggest that SAR may also play a special role in hemoglobin regulation. Although the precise pathway(s) and molecules through which SAR regulates the γ-globin gene remain unknown, SAR may increase the transport of membrane-bound transcription factor precursors from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi. In this model, the proteolytic cleavage of the precursor proteins in the Golgi would activate cytosolic fragments that enter the nucleus and regulate erythroid-specific transcription factors, such as GATA, eventually modulating γ-globin gene expression. Alternatively, increased SAR levels in erythroid cells may influence local concentrations and intracellular locations of GTP and cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). Increased availability of intracellular GTP could affect γ-globin expression either directly or indirectly. It has been reported that guanine, guanosine, and guanine ribonucleotides, but not ATP, CTP, and UTP, induce K562 differentiation, which is associated with the accumulation of γ-globin mRNA.28 GTP also dramatically increases the half-life of γ-globin mRNA.29 Activators of the sGC and protein kinase G (PKG) pathways have been implicated in the regulation of γ-globin gene expression in both erythroleukemic cells and in primary erythroblasts.11 Expression of γ-globin and the sGC alpha subunit are correlated, indicating that GTP-binding proteins may participate in γ-globin induction. The finding of a direct interaction between SAR and erythroid-specific factors will strengthen these speculative models.

Stable transfection of SAR into K562 cells arrested the cells at a premature stage, which is associated with increased synthesis of γ-globin. K562 cells express γ-, ε-, and δ-globin but not β-globin, and HU is reported to promote both γ- and β-globin production.7,30 We therefore transduced the SAR gene into CD34+ cells using a retroviral system to investigate its effects on β- and γ-globin production. We found that SAR and HU were similarly able to regulate hemoglobin production in the CD34+ stem cells, and SAR induced both γ- and β-globin production. SAR-mediated γ-globin induction was more sustained and profound than the induction of the β-globin gene. This indicates that γ-globin is an important target of SAR and HU during erythroid maturation.

Alterations in the p21, GATA-2, and ERK signal transduction pathways were seen in SAR-expressing cells. The transcription factors GATA-1 and GATA-2 are required for normal hematopoiesis. GATA-1 is essential for survival during primitive and definitive erythropoiesis and terminal maturation. GATA-2 is required for the expansion of multipotential hematopoietic progenitors, but is dispensable for terminal differentiation of erythroid cells and plays a critical role in both the proliferation and survival of early hematopoietic cells.31 Enforced expression of GATA-2 in pluripotent hematopoietic cells blocks both their amplification and differentiation.32 GATA-1 and GATA-2 are important in hemoglobin regulation.8 In the regulatory loop between SAR and the γ-globin gene, GATA-1 and GATA-2 can interact to enhance γ-globin promoter activity. It has been shown that a decline in GATA-1 levels alone, without a substantial change in GATA-2, does not affect γ-globin gene expression.33 Increasing GATA-2 levels increase ε-globin and γ-globin transcripts in K562 cells.8 In the present study, GATA-2 protein levels increased significantly in SAR-expressing cells without a significant change in GATA-1, consistent with the effect of HU on parental K562 cells. We posit that SAR may disturb erythroid maturation by up-regulating GATA-2, resulting in an increase in γ-globin production.

p21 plays a regulatory role within the G1/S cell-cycle check-point. Forced GATA-2 expression inhibits cytokine-dependent growth of normal hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells by modulating p21 protein levels.34 In p21-transgenic mice, p21 was found to regulate proliferation and differentiation of early hematopoietic progenitors and, to a lesser extent, of erythroid cells.35 In this study, SAR-expressing cells not only up-regulated GATA-2, but also had a 2- to 3-fold increase in p21 levels. It is likely that p21 induction in SAR-transfected cells exceeded a growth-inhibiting threshold; this would have prevented cells from differentiating into terminal erythroid cells, thereby keeping them at a stage conducive to Hb F production. Our data are consistent with a recent report that GATA-2 inhibited the growth of hematopoietic stem cells as well as other hematopoietic cell lines.34 The authors suggested that overexpression of GATA-2 may alter cytokine signals and shift the binding partners of GATA-2.

Small GTP-binding proteins interact with PI3 kinase binding proteins to facilitate vesicle-mediated vacuolar protein sorting. It has been reported that PI3 kinase regulates erythroid cell differentiation and hemoglobin production,36,37 and inhibition of PI3 kinase activity could dephosphorylate ERK.38 Enforced SAR expression in K562 cells down-regulated PI3 kinase and dephosphorylated ERK, which may imply that SAR blocks ERK phosphorylation through down-regulation of PI3 kinase. Inhibition of ERK has been shown to inhibit cell growth and gene transcription.39 ERK activity can be elevated in response to proliferative factors, as well as in response to differentiating agents; related signal molecules can show differences depending on the genetic makeup of cells used in each experiment. ERK dephosphorylation might induce hemoglobin synthesis and inhibit cell proliferation. Therefore, our data suggest that HU-induced increases in γ-globin gene mRNA levels may involve the PI3 kinase-ERK signal transduction pathway.

Taken together, our findings suggest that SAR induces γ-globin gene expression in human erythroid cells. HU up-regulates SAR gene expression in erythroid cells, implying that SAR may play a role in γ-globin gene induction and erythroid cell maturation. We have shown that enforced SAR expression alone can replicate the known effects of HU on erythroid cells, including cytotoxicity, G1/S-phase accumulation, macrocytosis, and γ-globin induction. The induction of SAR mRNA expression by HU also suggests that selective enhancement of membrane trafficking may play a role in erythrocyte maturation and proliferation. SAR is likely to be involved in a variety of normal erythrocyte functions.

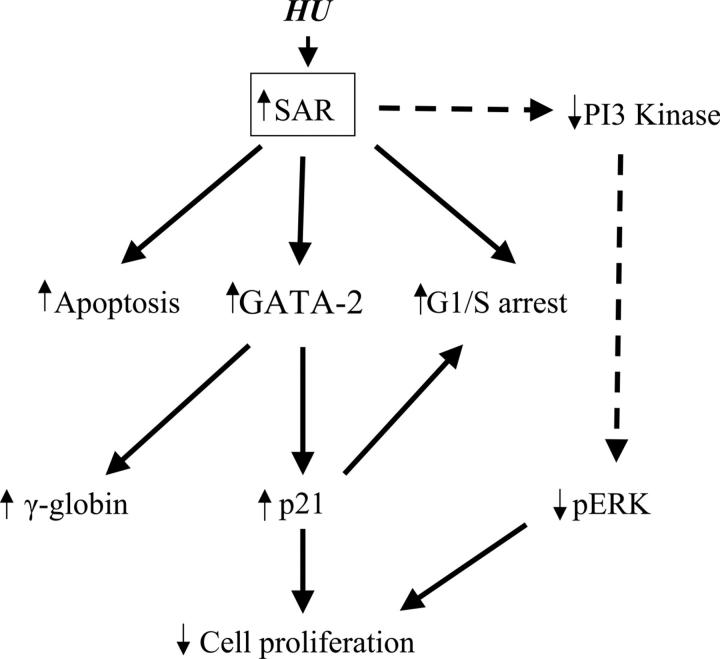

This study represents the first evidence that the small GTP-binding protein SAR participates in cell-cycle control through up-regulation of GATA-2 and p21 in erythroid maturation, as depicted in Figure 6. Elucidation of the relationship among SAR's vesicular trafficking functions and γ-globin induction may allow new therapies for sickle-cell disease and β-thalassemia. Further studies will determine whether SAR is an obligatory mediator of these effects and will explore the specific molecular pathways involved. Direct interactions between SAR and associated binding partner(s) should be established to provide the molecular basis of SAR function in hemoglobin protein production.

Figure 6.

Schematic pathways of SAR-mediated globin gene induction. Enforced SAR expression alone can replicate the known effects of HU on K562 cells, including cytotoxicity (apoptosis), G1/S-phase arrest, and γ-globin induction. SAR-induced GATA-2 expression not only increases γ-globin gene induction, it also induces p21 protein. Induction of p21 causes inhibition of cell proliferation and G1/S arrest. Reduction of PI3 kinase (PI3K) and phosphorylated ERK (pERK) can be triggered by SAR.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank Dr Juan Bonifacino and Dr Ivan Ding for valuable discussion and helpful suggestions.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, June 28, 2005; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3458.

D.C.T. and J.Z. contributed equally to this study.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

- 1.Rodgers GP, Dover GJ, Noguchi CT, Schechter AN, Nienhuis AW. Hematologic responses of patients with sickle cell disease to treatment with hydroxyurea. N Engl J Med. 1990;322: 1037-1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Charache S, Terrin ML, Moore RD, et al. Effect of hydroxyurea on the frequency of painful crises in sickle cell anemia: investigators of the Multicenter Study of Hydroxyurea in Sickle Cell Anemia. N Engl J Med. 1995;332: 1317-1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinberg MH, Barton F, Castro O, et al. Effect of hydroxyurea on mortality and morbidity in adult sickle cell anemia: risks and benefits up to 9 years of treatment. JAMA. 2003;289: 1645-1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torrealba-de Ron AT, Papayannopoulou T, Knapp MS, Fu MF, Knitter G, Stamatoyannopoulos G. Perturbations in the erythroid marrow progenitor cell pools may play a role in the augmentation of HbF by 5-azacytidine. Blood. 1984;63: 201-210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blau CA, Constantoulakis P, al-Khatti A, et al. Fetal hemoglobin in acute and chronic states of erythroid expansion. Blood. 1993;81: 227-233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papassotiriou I, Stamoulakatou A, Voskaridou E, Stramou E, Loukopoulos D. Hydroxyurea induced erythropoietin secretion in sickle cell syndromes may contribute in their Hb F increase [abstract]. Blood. 1998;92: 160a.9639512 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang M, Tang DC, Liu W, et al. Hydroxyurea exerts bi-modal dose-dependent effects on erythropoiesis in human cultured erythroid cells via distinct pathways. Br J Haematol. 2002;119: 1098-1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ikonomi P, Noguchi CT, Miller W, Kassahun H, Hardison R, Schechter AN. Levels of GATA-1/GATA-2 transcription factors modulate expression of embryonic and fetal hemoglobins. Gene. 2000;261: 277-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang J, Jordan SJ, Barr DP, Gunther MR, Maeda H, Mason RP. In vivo production of nitric oxide in rats after administration of hydroxyurea. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;52: 1081-1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu X, Lockamy VL, Chen K, et al. Effects of iron nitrosylation on sickle cell hemoglobin solubility. J Biol Chem. 2002;277: 36787-36792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikuta T, Ausenda S, Cappellini MD. Mechanism for fetal globin gene expression: role of the soluble guanylate cyclase-cGMP-dependent protein kinase pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98: 1847-1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takai Y, Sasaki T, Matozaki T. Small GTP-binding proteins. Physiol Rev. 2001;81: 153-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matozaki T, Nakanishi H, Takai Y. Small G-protein networks: their crosstalk and signal cascades. Cell Signal. 2000;12: 515-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lederkremer GZ, Cheng Y, Petre BM, et al. Structure of the Sec23p/24p and Sec13p/31p complexes of COPII. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98: 10704-10709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuoka K, Schekman R, Orci L, Heuser JE. Surface structure of the COPII-coated vesicle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98: 13705-13709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang M, Weissman JT, Beraud-Dufour S, et al. Crystal structure of Sar1-GDP at 1.7: a resolution and the role of the NH2 terminus in ER export. J Cell Biol. 2001;155: 937-948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Springer S, Spang A, Schekman R. A primer on vesicle budding. Cell. 1999;97: 145-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vidal MJ, Stahl PD. The small GTP-binding proteins Rab4 and ARF are associated with released exosomes during reticulocyte maturation. Eur J Cell Biol. 1993;60: 261-267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vita F, Soranzo MR, Borelli V, Bertoncin P, Zabucchi G. Subcellular localization of the small GTPase Rab5a in resting and stimulated human neutrophils. Exp Cell Res. 1996;227: 367-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishio H, Suda T, Sawada K, Miyamoto T, Koike T, Yamaguchi Y. Molecular cloning of cDNA encoding human Rab3D whose expression is up-regulated with myeloid differentiation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1444: 283-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fukushima S, Yamada T, Hashiguchi A, Nakata Y, Hata J. Augmentation of human leukemic cell invasion by activation of a small GTP-binding protein Rho. Exp Hematol. 2000;28: 391-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fibach E, Manor D, Treves A, Rachmilewitz EA. Growth of human normal erythroid progenitors in liquid culture: a comparison with colony growth in semisolid culture. Int J Cell Cloning. 1991;9: 57-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen L, Zhang J, Tang DC, Fibach E, Rodgers GP. Influence of lineage-specific cytokines on commitment and asymmetric cell division of haematopoietic progenitor cells. Br J Haematol. 2002;118: 847-857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith RD, Li J, Noguchi CT, Schechter AN. Quantitative PCR analysis of HbF inducers in primary human adult erythroid cells. Blood. 2000;95: 863-869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snedecor GW, Cochran WG. Statistical Methods. Ames, IA: Iowa State University, 1980.

- 26.Fabricius E, Rajewsky F. Determination of hydroxyurea in mammalian tissues and blood. Rev Eur Etud Clin Biol. 1971;16: 679-683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsuzaki T, Aisaki K, Yamamura Y, Noda M, Ikawa Y. Induction of erythroid differentiation by inhibition of Ras/ERK pathway in a friend murine leukemia cell line. Oncogene. 2000;19: 1500-1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osti F, Corradini FG, Hanau S, Matteuzzi M, Gambari R. Human leukemia K562 cells: induction to erythroid differentiation by guanine, guanosine and guanine nucleotides. Haematologica. 1997;82: 395-401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morceau F, Dupont C, Palissot V, et al. GTP-mediated differentiation of the human K562 cell line: transient [rf]overexpression of GATA-1 and stabilization of the gamma-globin mRNA. Leukemia. 2000;14: 1589-1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang SZ, Ren ZR, Chen MJ, et al. Treatment of beta-thalassemia with hydroxyurea (HU): effects of HU on globin gene expression. Sci China B. 1994;37: 1350-1359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsai FY, Orkin SH. Transcription factor GATA-2 is required for proliferation/survival of early hematopoietic cells and mast cell formation, but not for erythroid and myeloid terminal differentiation. Blood. 1997;89: 3636-3643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Persons DA, Allay JA, Allay ER, et al. Enforced expression of the GATA-2 transcription factor blocks normal hematopoiesis. Blood. 1999;93: 488-499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shimamoto T, Nakamura S, Bollekens J, Ruddle FH, Takeshita K. Inhibition of DLX-7 homeobox gene causes decreased expression of GATA-1 and c-myc genes and apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94: 3245-3249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ezoe S, Matsumura I, Nakata S, et al. GATA-2/estrogen receptor chimera regulates cytokine-dependent growth of hematopoietic cells through accumulation of p21(WAF1) and p27(Kip1) proteins. Blood. 2002;100: 3512-3520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Albanese P, Chagraoui J, Charon M, et al. Forced expression of p21 in GPIIb-p21 transgenic mice induces abnormalities in the proliferation of erythroid and megakaryocyte progenitors and primitive hematopoietic cells. Exp Hematol. 2002;30: 1263-1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bavelloni A, Faenza I, Aluigi M, et al. Inhibition of phosphoinositide 3-kinase impairs pre-commitment cell cycle traverse and prevents differentiation in erythroleukemia cells. Cell Death Differ. 2000;7: 112-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kubota Y, Tanaka T, Yamaoka G, et al. Wortmannin, a specific inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase, inhibits [rf]erythropoietin-induced erythroid differentiation of K562 cells. Leukemia. 1996;10: 720-726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmidt EK, Fichelson S, Feller SM. PI3 kinase is important for Ras, MEK and Erk activation of Epo-stimulated human erythroid progenitors. BMC Biol. 2004;2: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kortenjann M, Thomae O, Shaw PE. Inhibition of v-raf-dependent c-fos expression and transformation by a kinase-defective mutant of the mitogen-activated protein kinase Erk2. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14: 4815-4824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]