Abstract

When the Lac− strain of Escherichia coli, FC40, is incubated with lactose as its sole carbon and energy source, Lac+ revertants arise at a constant rate, a phenomenon known as adaptive mutation. Two alternative models for adaptive mutation have been proposed: (i) recombination-dependent mutation, which specifies that recombination occurring in nongrowing cells stimulates error-prone DNA synthesis, and (ii) amplification-dependent mutation, which specifies that amplification of the lac region and growth of the amplifying cells creates enough DNA replication to produce mutations at the normal rate. Here, we examined several of the predictions of the amplification-dependent mutation model and found that they are not fulfilled. First, inhibition of adaptive mutation by a gene that is toxic when overexpressed does not depend on the proximity of the gene to lac. Second, mutation at a second locus during selection for Lac+ revertants is also independent of the proximity of the locus to lac. Third, mutation at a second locus on the episome occurs even when the lac allele under selection is on the chromosome. Our results support the hypothesis that most Lac+ mutants that appear during lactose selection are true revertants that arise in a single step from Lac− cells, not from a population of growing or amplifying precursor cells.

When Lac− cells of Escherichia coli strain FC40 are plated on medium with lactose as the sole carbon and energy source, Lac+ revertants arise at a constant rate for about a week (6). Because Lac+ revertants do not arise when the cells are merely starving in the absence of lactose, this phenomenon was originally thought to be an example of “directed mutation” (8). However, other, nonselected mutations appear in the Lac− population while Lac+ mutations are occurring (17), so the phenomenon is now known as adaptive mutation. This term refers to one or more processes that produce mutations that relieve the selective pressure, whether or not other, nonselected mutations also occur (19).

Adaptive mutation to Lac+ in strain FC40 has a number of characteristics that distinguish it from normal growth-dependent mutation (reviewed in references 18 and 47). Three of these characteristics are of particular relevance to this study: (i) adaptive mutation requires recombination functions, (ii) adaptive mutation is enhanced when the mutational target is on the F episome and conjugal functions are expressed, and (iii) most of the adaptive mutations are due to the error-prone DNA polymerase IV (Pol IV).

Adaptive mutation in FC40 includes another phenomenon, called by various researchers hypermutation, transient mutation, general mutagenesis, or general hypermutability. About 1% of the Lac+ revertants of FC40 isolated after incubation on lactose medium have mutations elsewhere in their genomes, indicating that they have experienced a state of hypermutation (46, 56). However, when tested, these revertants do not have high mutation rates, indicating that the hypermutable state is transient. The extra mutations do not appear if Pol IV is defective (55) or if the SOS response is repressed (53). In addition, the mismatch repair system is not active in the hypermutating population (46). The hypermutators account for only 10% of the Lac+ adaptive mutations, whereas 90% of the Lac+ mutations occur in the normal population (46). The experiments reported here do not address the mechanism of hypermutation but instead focus on how the majority of adaptive Lac+ mutations are produced.

Two alternative models for adaptive mutations have been proposed to account for the majority of the Lac+ adaptive mutations. The model we favor, called here “recombination-dependent mutation” (RDM), is as follows (18). When FC40 is incubated on lactose, the cells do not proliferate, but because the mutant lac allele is leaky, enough energy is available so that replication is occasionally initiated at one of the episome's vegetative origins. Although the cells are not conjugating, the conjugal origin sustains a low level of nicking (25); when the replication fork encounters this persistent nick, the fork collapses, creating a double-strand end that initiates double-strand break repair. During this process, RecA catalyzes the invasion of a single strand into the homologous duplex, priming DNA synthesis from the 3′ end. Either the accurate DNA polymerase, Pol II, or the error-prone polymerase, Pol IV, can be recruited to perform this synthesis. If Pol IV prevails, it synthesizes a track of error-containing DNA. When this synthesis includes the lac region, Lac+ mutations are produced.

The alternative model, called here “amplification-dependent mutation” (ADM), is favored by Roth and coworkers (48, 49). They propose that the Lac− population initially contains a few cells that have duplicated the lac region. Because the mutant lac allele is leaky, these cells further amplify the lac region and slowly grow on the lactose medium, producing microcolonies of pseudo-Lac+ cells. True Lac+ revertants occur among the amplifiers when the total number of lac alleles (the number of cells multiplied by the number of their lac alleles) becomes so large that the probability of mutation is high. Then, as each Lac+ revertant multiplies, its amplification is resolved so that the Lac+ cells eventually carry only a single Lac+ allele. In their latest model, Roth and Andersson assumed a mutation rate of one Lac+ mutation for every 108 replications of the lac region, which is close to the normal growth-dependent mutation rate. With this mutation rate, the replications required for each Lac+ mutation can be achieved if 100 amplifying clones each reach a size of 104 cells and each cell has 100 copies of the mutant lac allele (48).

As described many years ago (54), when certain Lac− strains of E. coli are plated on minimal lactose medium, colonies can appear that are composed of cells that have amplified the Lac− allele to the extent that they are phenotypically Lac+. These can be detected by loss of the Lac+ phenotype when the putative revertant cells are grown on nonselective medium (54). During a normal 5-day adaptive-mutation experiment with FC40, colonies composed of unstably Lac+ cells are only a few percent (≈2%) of the total number of Lac+ colonies that appear (16). However, if the experiment is continued beyond 5 days, the proportion of colonies composed of unstably Lac+ cells increases, eventually becoming 30% to 40% of the total (26, 41).

The appearance of clones of unstably Lac+ cells neither supports nor refutes either of the two models described above. According to the RDM model, the majority of Lac+ revertants that appear in the first 5 days of an experiment are due to RDM, while amplification without reversion accounts for the minority, slowly growing Lac+ colonies that appear later in the experiment. In contrast, according to the ADM model, amplification is the precursor of all of the Lac+ colonies, whether they are composed of true Lac+ revertants, unstable amplifiers, or a mixture of both. Because, according to the ADM model, the amplified mutant lac copies disappear when a true Lac+ revertant appears, it has proved difficult to produce compelling evidence to distinguish between the two models.

In the study reported here, we tested several of the predictions of the ADM model. We reexamined some previously reported results and found that, when proper controls were done, the results did not support the ADM model. Furthermore, we generated new results that refute several strong predictions of the ADM model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The strains used are listed in Table 1 . Genetic manipulations were performed using standard techniques (34). The source of the tetracycline-resistant (Tcr) defective transposon zzf-1831::dTn10 Tcr was Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strain TT10423 (obtained from J. Roth). The creation of the F′ Φ(lacI33-lacZ) Pro+ zzf-1831::dTn10 Tcr strain FC453 is described elsewhere (17, 23); FC453 is identical to TT22951 (28). A Tcr scavenger strain was made by mating the episome from TT10423 into an E. coli strain and using a P1 lysate of this strain to transduce the scavenger strain, FC29, to Tcr Lac−; the episome from this strain was passed through a collector strain and then mated back into P90C [= ara Δ(gpt-lac)5 thi] (12) to create PFJ212. The creation of strain FC722, a Tcs (tetracycline-sensitive) derivative of FC453, is described elsewhere (17), and the same method was used to make Tcs derivatives of strains TT23244 and TT23245 (28). Briefly, the Tcr strains were mutated with the frameshift mutagen ICR191, and Tcs cells were selected (32). The Tcs episomes were then passed through a collector strain and mated back into FC36 [= ara Δ(gpt-lac)5 thi Rifr] (6) to yield FC1440 and FC1443. The two mutant tetA alleles from these strains were amplified and sequenced; FC1440 has a +1 G mutation in a run of four Gs that begins at bp 815 of the tetA coding sequence; FC1443 has a +1 G mutation in a run of four Gs that begins at bp 331 of the tetA coding sequence, which is the same mutation as that carried by FC722 (17).

TABLE 1.

E. coli strains used in this study

| Strain | Phenotype or genotype | Relevant characteristic | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| MG1655 | Wild type | 2 | |

| FC29 | ara Δ(gpt-lac)5 thi/F′ Δ(lacIZ) Pro+ | Nonrevertible Lac− | 6 |

| FC36 | ara Δ(gpt-lac)5 thi Rifr | Nonrevertible Lac− | 6 |

| FC40 | FC36/F′ Φ(lacI33-lacZ) Pro+ | Revertible Lac− on the episome | 6 |

| FC453 | FC40 zzf-1831::dTn10 Tcr | Tcr Tn10 5 kb from lac on the episome | 23 |

| FC572 | FC40 eda-51::Tn10 | Tcr on the chromosome | 24 |

| FC691 | F− Φ(lacI33-lacZ) | Revertible Lac− on the chromosome | 46 |

| TP941 | MG1655 Φ(lacI33-lacZ) | Revertible Lac− on the chromosome | This study |

| PFJ212 | FC29 zzf-1831::dTn10 Tcr | Tcr Tn10 5 kb from lac on the episome | This study |

| FC722 | FC453 Tcs | Tcs Tn10 5 kb from lac on the episome | 17 |

| TT23243 | FC40 dTn10 Tcr | Tcr Tn10 99 kb from lac on the episome | 28 |

| TT23244 | FC40 dTn10 Tcr | Tcr Tn10 105 kb from lac on the episome | 28 |

| TT23245 | FC40 dTn10 Tcr | Tcr Tn10 24 kb from lac on the episome | 28 |

| FC1373 | FC691 dTn10 Tcs | Revertible Lac− and Tcs on the chromosome | This study |

| FC1440 | TT23244 Tcs | Tcs Tn10 105 kb from lac on the episome | This study |

| FC1443 | TT23245 Tcs | Tcs Tn10 24 kb from lac on the episome | This study |

| FC1477 | FC1443 Δ(lacIZYA) | Tcs Tn10 24 kb from Δ(lacIZYA) on the episome | This study |

| FC1482 | FC36 eda::Knr-Φ(lacI33-lacZ) | Revertible Lac− on the chromosome | This study |

| FC1487 | FC1482 × F′(FC1477) | Revertible Lac− on the chromosome; Tcs Tn10 24 kb from Δ(lacIZYA) on the episome | This study |

Mapping the transposons.

The locations of Tn10 in strains TT23243, TT23244, and TT23245 were determined by sequencing products of arbitrarily primed PCR (42). This technique uses two cycles of PCR. The first cycle was performed using genomic DNA, the Tn10-specific primer 5′-AGTTCGGTAAGAGTGAGAG3′, and two different arbitrary primers. The second cycle was performed using amplified DNA from the first cycle; a nested Tn10-specific primer, 5′CATATGACAAGATGTGATC-3′; and another arbitrary primer. The amplified product was confirmed by gel electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide.

Cloning of Φ(lacI33-lacZ).

The lambda Red recombination system is described elsewhere (39). pTP1016 (39) contains the cat gene flanked by the E. coli sequences that normally flank the lacI and lacY genes. Red-mediated gap repair was used to clone the chromosomal lacIq Φ(lacI33-lacZ)-lacY+ region. First, pTP1049 was made by cutting pTP1016 with restriction endonucleases SphI and BsrGI, electroporating the gapped plasmid into strain TP732 (40), and selecting for ampicillin-resistant (Apr) transformants; the resulting plasmid was the product of Red-mediated gap repair, in the process of which it acquired the chromosomal lacIq Φ(lacI33-lacZ)-lacY+ version of the lac operon. Second, pTP1058 was made by deleting sequences between the BglII and BamHI sites of pTP1049. Third, a kanamycin-resistant (Knr) element was installed just upstream of lacI by ligating a Knr cassette derived from Tn903 into the SphI site of pTP1049, creating pTP1070; this Knr cassette was made by PCR amplification with the oligodeoxyribonucleotides 5′-CATCATCACGCATGCACGTTGTGTCTCAAAATCTCTGA-3′ and 5′-ATCATCCACGCATGCTACAACCAATTAACCAATTCTGATTAG-3′. Fourth, the plasmid-borne Knr-Φ(lacI33-lacZ)-lacY+ cassette was crossed onto the chromosome by electroporating linearized pTP1070 into a Red+ Δ(lacIZYA) derivative of MG1655; recombinants were selected for Knr, and their structures were verified by PCR. Finally, the Knr-Φ(lacI33-lacZ)-lacY+ construct was moved into normal (Red−) MG1655 Δ(lacIZYA) by P1 transduction.

Construction of a strain with an ectopic chromosomal Φ(lacI33-lacZ)-lacY+ allele and a Lac− Tcs episome.

To make a strain carrying an ectopic version of the mutant lac allele, Knr-Φ(lacI33-lacZ)-lacY+ was inserted into the eda gene as follows. First, an E. coli strain in which most of the eda gene was replaced by cat was constructed by electroporating TP829 (a Red+ derivative of MG1655) (39) with the PCR product of strain TP872 (39) amplified with primers 5′-CCTGTATCACTTTTTAAGACGACAAATTTGTAATCAGGCGGCATGCATTTACGTTGAATG-3′ and 5′- GTAGTTAGCCGGAGAAATACCACCCGTCGGGCAGAAACGGTGTACAATTCAGGCGTAGCA-3′. Second, the cat gene and its flanking chromosomal sequences were amplified with primers 5′-CCGTGCGGTTATGAAAACCT-3′ and 5′-CGTAAAGTGGTGCTGGCACT-3′, and the product was digested with NgoMIV and BglII and ligated to the NgoMIV- and BglII-cut plasmid. Third, the cat gene of the resulting plasmid was replaced by cutting it with SphI and BsrGI and ligating in the Φ(lacI33-lacZ)-lacY+ cassette from plasmid pTP1049. Fourth, the Knr element from Tn903 was inserted into the SphI site upstream from Φ(lacI33-lacZ)-lacY+ in the plasmid in such a way that its direction of transcription was away from lac, creating plasmid pTP1157. Fifth, the Δeda::Knr-Φ(lacI33-lacZ)-lacY+ element was crossed onto the chromosome by digesting pTP1157 with NgoMIV and BglII, electroporating the linear product into a Red+ Δ(lacIZY) strain, and selecting Knr recombinants, the structures of which were verified by PCR. Finally, Δeda::Knr-Φ(lacI33-lacZ)-lacY+ was moved into FC36 by P1 transduction, with selection for Knr colonies, yielding strain FC1482.

The Δ(lacIZYA) Tcs episome was made by first mating the Tcs episome from strain FC1443 into a Δ(lacIZYA) Met− strain. A ΔlacIZYA::Cm insertion-deletion was created in the episome using lambda Red-mediated recombination as previously described (13), yielding strain FC1477. The resulting episome was mated into FC1482, selecting for Met+ and Pro+, yielding strain FC1487.

Mutation, growth, and viability assays.

Media and experimental protocols were as previously described (6, 16). As required, minimal medium was supplemented with 10 μg/ml tetracycline (Tc), 50 μg/ml chlortetracycline (CTc), and 40 μg/ml 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal, a chromogenic substrate of β-galactosidase that stains Lac+ cells blue). To measure adaptive mutation to Lac+ in strains with the mutant lac allele on the episome, several independent cultures of the revertible (tester) strains and a culture of PFJ212 (scavenger) cells were grown to saturation in M9-glycerol minimal medium; about 108 tester cells from each culture plus about 109 scavenger cells were added to 2 ml minimal top agar with and without Tc or CTc and plated onto M9-lactose plates with and without Tc or CTc. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 5 days, and new Lac+ colonies were counted every day. The same procedure was used to measure adaptive mutation to Lac+ in strains with the mutant lac allele on the chromosome, except 109 tester cells were plated with no scavenger cells. To determine mutation rates to Tcr, Tcs strains were grown as described above; five samples of 108 tester cells from each culture plus 109 cells of the scavenger, FC29, were added to 2 ml minimal top agar and plated onto five M9-lactose plates. These were then overlaid with 2 ml minimal top agar and incubated at 37°C for 5 days. New Lac+ colonies were counted and marked every day. After 0, 1, 2, and 3 days of incubation, one set of plates from each culture were overlaid with 5 ml minimal top agar containing 1.2% glycerol, 1 mg of X-Gal, and 0.4 mg of Tc. New white (Tcr Lac−) colonies were counted 3 days later. The number of cells in each culture was determined by plating appropriate dilutions on rich medium.

To calculate the fraction of Lac+ colonies that were not detected on lactose medium plus Tc or CTc, equations for the expected value and variance of a ratio were used (44). For each strain and each day, we calculated the expected value and variance of (L − T)/L, where L was the number of Lac+ colonies on lactose medium without Tc or CTc and T was the number of Lac+ colonies on lactose medium with Tc or CTc. These calculations accounted for the covariances of the values, as described previously (44).

RESULTS

Amplification of the lac locus is not a necessary precursor to Lac+ adaptive mutation.

The ADM model predicts that if amplification is inhibited, all adaptive mutation to Lac+ should also be inhibited. To test this prediction, Hendrickson et al. (28) exploited the fact that cells with one copy of the transposon Tn10 are Tcr, but cells with multiple copies of Tn10 become Tcs. This is because Tc induces the tetA gene that is carried on the transposon, and overproduction of the efflux transporter encoded by tetA is toxic (11, 15).

Escherichia coli strain FC40 has the lac operon deleted from the chromosome but carries a revertible mutant lac allele, Φ(lacI33-lacZ), on its episome (6). Hendrickson et al. (28) constructed several derivatives of FC40, each of which had a defective Tn10 at a different distance from the unreverted lac allele. When these FC40 derivatives were tested for adaptive reversion to Lac+ in the presence of Tc or CTc, a nontoxic inducer of tetA, the rate of adaptive mutation to Lac+ declined in proportion to the closeness of the Tn10 to lac. In contrast, a chromosomal Tn10 had no effect, and none of the Tn10s affected the appearance of Lac+ revertants during exponential growth (28). The authors interpreted these results to mean that when the Tn10 is coamplified with lac, the increased copies of the tetA gene make the cells sensitive to Tc or CTc, so amplifying cells are eliminated from the population. Since, according to the ADM model, amplification is a necessary precursor for reversion to Lac+, Lac+ revertants are also eliminated. The closer the Tn10 is to lac, the more likely it will be coamplified, so the greater the reduction in Lac+ reversion due to Tc or CTc will be (28).

We obtained (from John Roth) the strains used by Hendrickson et al. (28). To identify the exact locations of the Tn10 insertions, we sequenced the region flanking each one. Strains TT23243, TT23244, and TT23245 have Tn10 inserted in repC (99 kb from lac), in the F plasmid gene ycbB (104 kb from lac), and in yafA (24 kb from lac), respectively. These results are in agreement with previous estimations of the locations of the transposons in these strains (28). Strain FC453 (23), which is identical to strain TT22951 used by Hendrickson et al. (28), has a Tn10 in the mhpC gene, about 5 kb from lac (29; our unpublished results).

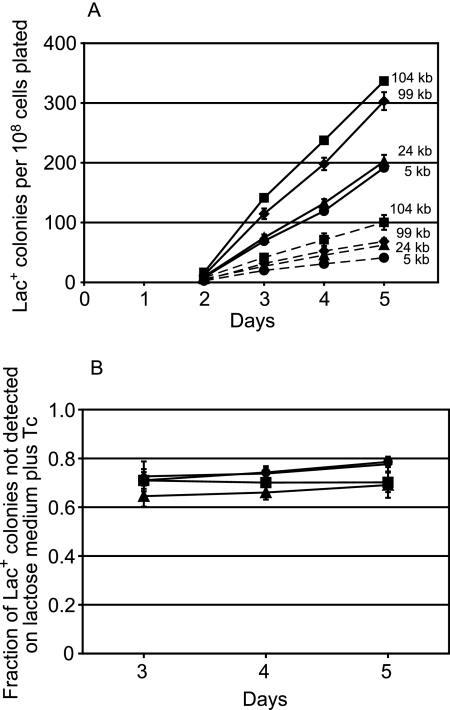

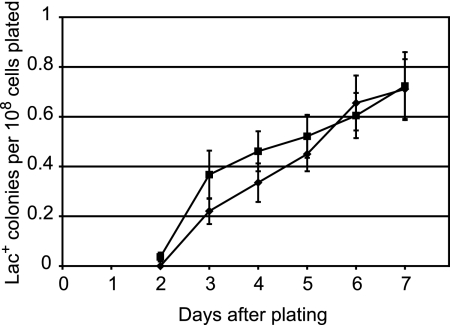

We repeated the experiments described above, and as shown in Fig. 1A, we obtained some of the same results as did Hendrickson et al. When the lactose plates contained Tc, the rate of adaptive mutation to Lac+ was reduced. In addition, the closer the Tn10 was to lac, the lower was the rate of reversion to Lac+ in the presence of Tc. However, as a control, we simultaneously plated these same cultures on lactose plates without Tc. Figure 1A shows that, as expected, the rates of reversion to Lac+ for all the strains were higher without Tc. However, unexpectedly, the reversion rate of each strain in the absence of Tc paralleled its rate in the presence of Tc. That is, Tc reduced the rate at which Lac+ adaptive mutations appeared by the same extent, about 70 to 80%, no matter where on the episome the Tn10 was located. These results are summarized in Fig. 1B.

FIG. 1.

Effect of tetracycline on adaptive mutation to Lac+ of strains with Tn10s at various distances from the mutant lac allele. Samples from three independent cultures of each strain were plated with PFJ212 scavenger cells on lactose medium with and without Tc. (A) The mean cumulative number of Lac+ colonies appearing from days 2 to 5 divided by the number of cells plated. The error bars, some of which are smaller than the symbols, indicate the standard error of the mean (SEM). Each number is the distance in kb of the Tn10 element from the mutant lac allele. Circles, FC453; triangles, TT23245; squares, TT23244; diamonds, TT23243; solid lines, without Tc; dashed lines, with Tc. (B) The fraction of the total number of Lac+ colonies that did not appear from days 3 to 5 when the lactose medium contained Tc. The error bars represent the SEM (see Materials and Methods). The results from day 2 are not shown because the colonies that appear on day 2 are due to mutations occurring during nonselected growth prior to plating.

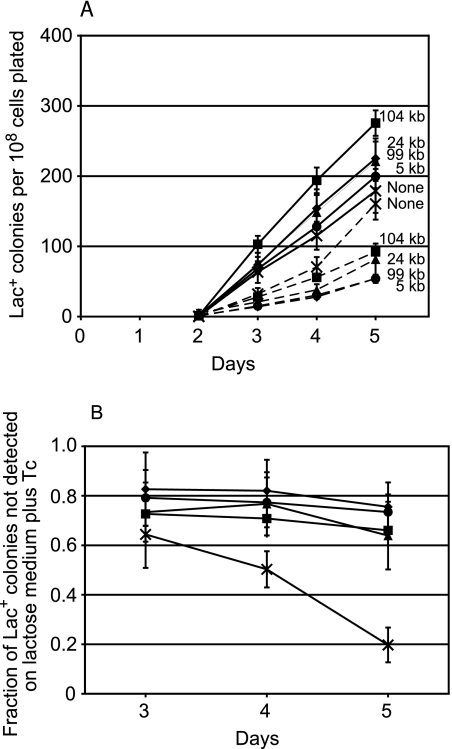

We repeated this experiment with CTc, the nontoxic inducer of tetA, and obtained the same results (Fig. 2A). As shown in Fig. 2B, the rates of adaptive mutation to Lac+ of strains with a Tn10 on the episome were all reduced by the same amount, 60 to 80%, in the presence of CTc no matter where on the episome the Tn10 was located. In the same experiment, we also tested the effect of CTc on FC40, which has no Tn10, and on an FC40 derivative that has a Tn10 in the eda gene on its chromosome (which we previously demonstrated does not affect adaptive mutation [24]). CTc inhibited the rate of adaptive mutation to Lac+ of FC40 by only about 10% and actually stimulated that of the strain with Tn10 on its chromosome by about 20% (Fig. 3). In addition, it is clear from Fig. 3 that in the absence of CTc (or Tc), the rates of reversion to Lac+ of all of the strains with a Tn10 on the episome were higher than the reversion rate of FC40 or FC40 with Tn10 on the chromosome. Thus, the simple presence of Tn10 on the episome does not inhibit mutation.

FIG. 2.

Effect of chlortetracycline on adaptive mutation to Lac+ of strains with Tn10s at various distances from the mutant lac allele. Samples from four independent cultures of each strain were plated with FC29 scavenger cells on lactose medium with and without CTc. (A) The mean cumulative number of Lac+ colonies appearing from days 3 to 5 divided by the number of cells plated. The error bars, some of which are smaller than the symbols, represent the standard errors of the mean (SEM). Each number is the distance in kb of the Tn10 element from the mutant lac allele (28). Circles, FC453; triangles, TT23245; squares, TT23244; diamonds, TT23243; crosses, FC40; solid lines, without CTc; dashed lines, with CTc. (B) The fraction of the total number of Lac+ colonies that did not appear from days 3 to 5 when the lactose medium contained CTc. The error bars represent the SEM (see Materials and Methods). The results from day 2 are not shown because the colonies that appear on day 2 are due to mutations occurring during nonselected growth prior to plating.

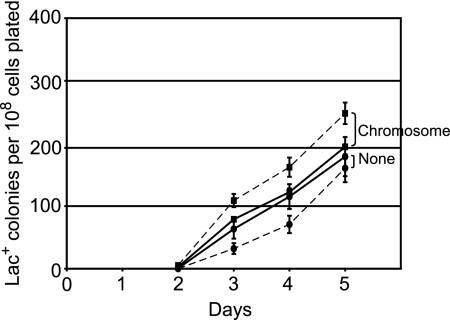

FIG. 3.

Effect of chlortetracycline on adaptive mutation to Lac+ of strains with no Tn10 or with a Tn10 on the chromosome. Samples from four independent cultures of each strain were plated with FC29 scavenger cells on lactose medium with and without CTc. The data are the mean cumulative numbers of Lac+ colonies appearing from days 2 to 5 divided by the number of cells plated. The error bars, some of which are smaller than the symbols, represent the standard errors of the mean. Circles, FC40; squares, FC572; solid lines, without CTc; dashed lines, with CTc. The data shown here are from the same experiment shown in Fig. 2.

We interpret these results to mean that inhibition of adaptive mutation by Tc or CTc does not require amplification of the lac region. When cells amplify lac, the amplified region is 10 to 40 kb long, centered on the lac locus (1, 26, 54); thus, the two Tn10s that are located 99 kb and 104 kb from lac should only rarely, if ever, be coamplified with lac (28). These two Tn10s are also outside of a 135-kb duplication (not amplification) reported on the episome (49, 51, 53), yet the inhibition of adaptive mutation by Tc or CTc was as great in cells carrying these Tn10s as it was in cells with a Tn10 that was only 5 kb away from lac. The ADM model cannot account for these results.

Amplification of a mutant tetA allele is not a necessary precursor of its reversion during lactose selection.

When FC40 is under selection to become Lac+, other, nonselected mutations also occur. This was first detected as reversion of a frameshift mutation in the tetA gene carried by a Tn10 element on the episome (17). When the Lac− population was incubated on lactose medium, reversion to Tcr occurred at a rate similar to that of reversion to Lac+ and with the same genetic requirements (17). Since the same element inserted in the chromosome reverts at a much lower rate during lactose selection (5), which is also true of the mutant lac allele (22, 43, 46), mutation rates during nutrient limitation appear to be about 100-fold higher on the episome than on the chromosome (7).

The mutant Tn10 that was used in the prior study (17) is the same element used by Hendrickson et al. (28) and in the experiments described above. Since this element is only about 5 kb from the mutant lac allele, Roth and Andersson (48) have argued that the high rate of reversion of this mutant tetA gene is due to its frequent coamplification with the mutant lac allele during lactose selection. According to the ADM model, when coamplified, mutations reverting the tetA allele occur among the extra copies, and then the amplification is resolved with a Tcr mutation but without a Lac+ mutation. Thus, Roth and Andersson claimed that higher episomal mutation rates are not required to explain the results (48).

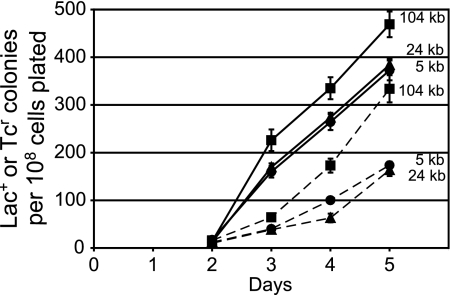

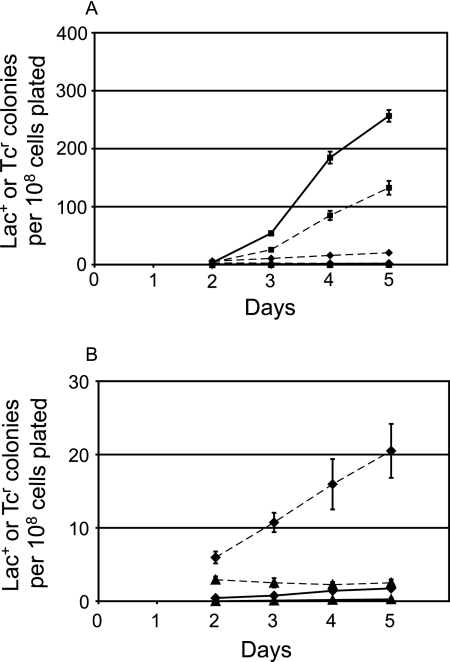

The ADM model predicts that only mutant tetA genes that are close to the mutant lac allele should revert during lactose selection. We tested this prediction by making revertible frameshift mutations in the tetA genes of two Tn10 elements used in the experiments described above that are located 24 and 104 kb from lac. As shown in Fig. 4, when these strains were incubated on lactose, Tcr revertants accumulated with kinetics similar to reversion of the tetA gene located only 5 kb from lac. Indeed, reversion of the mutant tetA gene located 104 kb from lac occurred at a higher rate than did that of the mutant tetA gene located 5 kb from lac. Also, as previously published (17), Tcr reversion occurred only during lactose incubation, not when the Tcs cells were merely starved without lactose (data not shown). We interpret these results to mean that coamplification of Tn10 is not required for reversion of the tetA gene during lactose selection.

FIG. 4.

Adaptive mutation to Lac+ and reversion to Tcr of strains with a Tcs Tn10 at various distances from the mutant lac allele. Samples from four independent cultures of each strain were plated with FC29 scavenger cells on lactose medium. Every day, a subset of the plates was overlaid with top agar containing glycerol, X-Gal, and Tc (see Materials and Methods). The data are the mean cumulative numbers of Lac+ colonies or Tcr colonies appearing from days 2 to 5 divided by the number of cells plated. The error bars, some of which are smaller than the symbols, represent the standard errors of the mean. Circles, FC722; triangles, FC1443; squares, FC1440; solid lines, Lac+ colonies; dashed lines, Tcr colonies.

Lac+ mutants arise in a strain with an intact chromosomal lac allele.

When the mutant lac allele was moved from the episome to the chromosome by recombination, the rate of adaptive mutation fell 100-fold (22). However, Slechta et al. (51) did not see a similar decrease when they used a transposon to insert the mutant lac allele at various positions in the Salmonella enterica genome. To explain this discrepancy, Roth and Andersson (48) proposed that the lac allele had been rearranged during recombination in the E. coli strain. The Φ(lacI33-lacZ) allele has three mutations, a promoter-up mutation, lacIq, that increases transcription; a small deletion fusing lacI to lacZ that puts lacZ under the control of the lacIq promoter; and a +1 frameshift in the lacI coding sequence that inactivates lacZ and lacY (6, 9, 36). Roth and Andersson (48) suggested that during recombination, these three mutations could have been dissociated. In addition, a unique junction between the lac locus and the dinB locus was created when the episome originally excised from the chromosome, and this might give rise to further rearrangements.

To verify the structure of the chromosomal lac allele used in our previous experiments, we cloned it with minimal flanking sequences from strain FC691 (46) into a plasmid. Direct sequencing of relevant parts of the plasmid DNA showed the presence of the three expected mutations described above (data not shown). We then tagged the allele with a Knr element and reintroduced it into the chromosome at its proper place in MG1655, a nearly wild-type strain of E. coli. The original and reconstructed strains were compared for reversion to Lac+, and as shown in Fig. 5, the two strains reverted at approximately the same rate. We obtained similar results with an MG1655 derivative that received the Φ(lacI33-lacZ) allele by transduction in such a way that the episomal dinB gene was not also transferred (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Adaptive mutation to Lac+ of the original and the reconstructed chromosomal Φ(lacI33-lacZ) strains. Cells from eight independent cultures of each strain were plated on lactose medium. The data are the mean cumulative numbers of Lac+ colonies appearing each day divided by the number of cells plated. The error bars represent the standard errors of the mean. Diamonds, FC691; squares, TP941.

Tcr reversion occurs when lac and tet are in trans.

If amplification of the mutant lac allele were necessary for Tcr reversion, the mutant lac and tetA alleles would have to be in cis. To test this hypothesis, we created a strain with the lac allele on the chromosome and the mutant tetA allele on the episome. The Knr-Φ(lacI33-lacZ) construct described above was inserted into the eda gene on the chromosome of the strain with lac-pro deleted, FC36. The eda gene was chosen because we had previously demonstrated that disrupting it has no effect on adaptive mutation (24). The episome used was from FC1443, which has the mutant tetA allele 24 kb from lac. To prevent recombination between the ectopic lac allele on the chromosome and the lac allele on the episome, all of lacI, -Z, -Y, and -A were deleted from this episome. The rate of adaptive reversion to Lac+ of this strain, FC1487, was indistinguishable from that of FC1373, which has both the mutant lac and the mutant tetA alleles on the chromosome (Fig. 6B). We compared reversion to Lac+ and Tcr during incubation on lactose medium of strains FC1373, FC1443, and FC1487. As shown in Fig. 6, reversion to Tcr of the strain (FC1487) with the mutant lac and tetA alleles in trans was eightfold higher than that of the strain (FC1373) with the mutant lac and tetA alleles in cis on the chromosome. However, Tcr reversion was sixfold higher yet in the strain (FC1443) with the lac and tet alleles in cis on the episome (see below). All of the Tcr revertants that arose during the experiment were dependent on the presence of lactose (data not shown). These results demonstrate that nonselected mutations arise in Lac− cells during lactose incubation, even when there is no possibility of coamplification of the second mutational target with the mutant lac allele.

FIG. 6.

Adaptive mutation to Lac+ and reversion to Tcr of strains with the mutant lac and tet alleles located either in cis or in trans. (A) Samples from five independent cultures of each strain were plated with FC29 scavenger cells on lactose medium. Each day, a subset of the plates was overlaid with top agar containing glycerol, X-Gal, and Tc (see Materials and Methods). The data are the mean cumulative numbers of Lac+ colonies or Tcr colonies appearing from days 2 to 5 divided by the number of cells plated. The error bars, some of which are smaller than the symbols, represent the standard errors of the mean. Solid lines, Lac+ colonies; dashed lines, Tcr colonies. In FC1443, the lac and tet alleles are both on the episome (squares); in FC1373, the lac and tet alleles are both on the chromosome (triangles); in FC1487, the lac allele is on the chromosome and the tet allele is on the episome (diamonds). (B) Same as panel A, except only data from strains FC1373 and FC1487 are shown with the y axis expanded.

DISCUSSION

The results presented here demonstrate that several of the predictions of the ADM model are not fulfilled. Our first result shows that, in contrast to a previous report (28), inhibition of Lac+ adaptive mutation by Tc or CTc does not require that the tetA gene be close to the mutant lac allele (Fig. 1 and 2). Two of the Tn10s used, 99 kb and 104 kb, are too far away from lac to be included in any amplification or duplication that has been reported for this episome (1, 26, 49, 51, 53, 54). Therefore, the inhibition appears not to result from coamplification of the two genes. Since placement of the Tn10 close to lac causes no more inhibition than placement of the Tn10 far from lac (Fig. 1B and 2B), it appears that amplification is not a precursor to Lac+ reversion.

Clearly, adaptive mutation to Lac+ is inhibited by Tc or CTc if there is a Tn10 anywhere on the episome but not if the Tn10 is on the chromosome or if the cell has no Tn10 (Fig. 1, 2, and 3). When Lac− cells are incubated in lactose medium, they have two to four episomes (21), and perhaps that many copies of the tetA gene are enough to be inhibitory. Alternatively, transcription of the tetA gene may directly inhibit adaptive mutation. For example, supercoiling domains can be altered by high levels of transcription of tetA and other genes (10, 14), and the episome might be particularly sensitive to this phenomenon. Such changes could influence the amount or efficiency of recombination or the ability of recombination to stimulate mutation at lac.

Our second result shows that proximity to lac is also not required for reversion of mutant tetA alleles during lactose selection (Fig. 4). Thus, these nonselected mutations, which occur at the same rate and with the same requirements as do adaptive Lac+ mutations (17), cannot be due to coamplification of tetA with lac, as was hypothesized (48). Indeed, the rate of reversion to Tcr was higher when the mutant tetA allele was distant from lac than when it was close. Since the mutation rates of both the tetA and lac alleles on the episome are much higher than those of the same alleles on the chromosome, these results support the hypothesis that the mutation rate on the episome is intrinsically high during lactose selection. Recently, it was reported that the mutation rate is high on the episome in growing cells as well and that these mutations also are largely due to Pol IV (30). We hypothesize that the episome has a high mutation rate because the persistent nick at the conjugal origin stimulates recombination (45) and that during recombination Pol IV is recruited to perform DNA synthesis (20). Homologous recombination between the episome and the chromosome is known to be particularly frequent (50), and F episomes from natural isolates show evidence of extensive recombination (3, 4, 35). However, the mechanism we proposed for mutation on the episome is expected to occur, albeit at a lower frequency, on the chromosome whenever a replication fork encounters a nick or double-strand break.

To account for the low rate of adaptive reversion when the mutant lac allele is on the E. coli chromosome, Roth and Andersson (48) hypothesized that the allele had been rearranged during the construction of the chromosomal derivative. To test this hypothesis, we cloned and sequenced the chromosomal lac locus from strain FC691 and found that it had the same sequence and structure as the original episomal allele. We then inserted the cloned lac segment into the chromosome of a nearly wild-type E. coli strain in such a way that there was little possibility for chromosomal rearrangements via homologous recombination. Our third result shows that the reconstructed chromosomal Φ(lacI33-lacZ) allele reverts at about the same rate as the original (Fig. 5), demonstrating that there is nothing special about FC691, the strain we normally use. We suggest that the difference between the results obtained with FC691 and those obtained by Roth and coworkers was their placement of the lac allele within a large, complex transposon and/or their use of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium instead of E. coli as their test organism (52).

Verifying the integrity of the chromosomal lac allele was important for our fourth result, which demonstrates that some nonselected Tcr mutations arise on the episome during lactose selection even when the mutant lac allele is in trans on the chromosome (Fig. 6). Like the Tcr revertants in the other strains, these revertants also did not appear when the cells were merely starving (data not shown). This result further supports the hypothesis that during lactose selection mutations on the episome accumulate independently of lac amplification. Furthermore, in the strain with lac and tet in trans, dinB and lac are not proximal either on the episome or on the chromosome; thus, dinB and lac coamplification is also not a requirement for mutation during lactose selection.

During lactose selection, the number of Tcr revertants that appeared in the strain with the mutant lac and tet alleles in trans was one-sixth of the number that appeared in the strain with the mutant alleles in cis on the episome. In addition, the Tcr reversion rate only tripled in a recG mutant strain with the mutant lac and tet alleles in trans compared to the 100-fold increase in a recG mutant strain with the mutant alleles in cis on the episome (data not shown). The mutant lac allele on the chromosome produces about one-half as much β-galactosidase as the mutant lac allele on the episome (P. L. Foster, unpublished results). It is possible that there is a threshold of energy that must be produced from the leaky lac allele to allow the full rate of episomal mutation and that this need is not met by the chromosomal lac allele.

Our results agree with the prediction of the RDM model that the sole role of the leaky lac allele is to provide the cell a small influx of energy while it is incubating on lactose medium. It was reported that when double-strand breaks were induced on the episome in stationary-phase cells, reversion of the mutant tetA allele 5 kb from the lac locus was stimulated even in the absence of lactose (38). Since adaptive reversion of both the mutant lac allele and the mutant tetA allele normally requires lactose (6, 17), these results suggest that the energy-dependent step of adaptive mutation is the formation of double-strand breaks. The RDM model postulates that double-strand breaks occur on the episome when DNA replication encounters the persistent single-strand nick at the conjugal origin, causing the replication fork to collapse (20). Therefore, we conclude that the slow influx of energy provided from the catabolism of lactose by the leaky lac allele allows DNA replication of the episome, resulting in the production of double-strand breaks.

Previous results have also not supported the ADM model. The ADM model is just one version of the “growth of an intermediate” model postulated by Lenski et al. (31). All such models predict that, as the intermediate population grows, the rate at which Lac+ revertants appear should increase with time. However, on solid and in liquid media, the rate at which Lac+ revertants of FC40 appear is constant for at least 5 days (6, 16). All “growth of an intermediate” models also predict that on solid medium the intermediate population should make microcolonies, but these have not been detected (16, 27).

It is possible to salvage certain features of the ADM model by judicious choice of parameters. For example, it has been proposed that the mutation rate in amplifying cells is 35 times the normal rate (28), which lowers the amount of lac amplification required. The nonlinearity predicted by the ADM model can be somewhat modified by randomly adjusting the probability that an amplifying clone will develop a Lac+ mutation (37, 51). The stochastic extinction of clones has also been evoked to explain why microcolonies cannot be detected (48). In a recent theoretical paper simulating the results of ADM, all of these adjustments were made (37). Interestingly, even using the most advantageous parameters, the probability that a Lac+ revertant would appear was essentially zero until the fifth day of the experiment, at which point the probability rose sharply. Thus, the ADM simulation did not account for the 100 or so Lac+ colonies that typically arise from days 2 to 5; instead, the simulation predicted that if Lac+ mutants were contingent on amplification, they would appear almost simultaneously after 5 days of incubation. This aspect of the simulation closely approximates experimental results obtained when a duplication of lac was engineered into a strain of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium: a burst of Lac+ colonies appeared after 5 days of incubation on lactose medium (51).

In conclusion, the results presented here support the hypothesis that most of the Lac+ mutants that appear during the first few days of lactose selection are true revertants that arise in a single step from Lac− cells, not from a population of growing or amplifying precursor cells. Amplification does occur, but it gives rise to cells that are unstably Lac+ because they contain amplifications of the Lac− allele. These cells make colonies that appear late in the experiment and normally contribute only slightly to the population of Lac+ colonies. The results reported here support other evidence (16, 21, 26, 27, 33, 40, 41) that, during lactose selection, amplification and true reversion are independent pathways leading to an adaptive Lac+ phenotype.

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Aiello, J. H. Miller, R. Proff, J. R. Roth, and B. L. Wanner for sending us bacterial strains and for technical assistance.

This work was supported by USPHS grant NIH-NIGMS GM65175 to P.L.F., NIH Training Grant T32 G07757 to J.D.S., and NSF grant MCB-0234991 to A.R.P.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 January 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersson, D. I., E. S. Slechta, and J. R. Roth. 1998. Evidence that gene amplification underlies adaptive mutability of the bacterial lac operon. Science 282:1133-1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blattner, F. R., G. Plunkett III, C. A. Bloch, N. T. Perna, V. Burland, M. Riley, J. Collado-Vides, J. D. Glasner, C. K. Rode, G. F. Mayhew, J. Gregor, N. W. Davis, H. A. Kirkpatrick, M. A. Goeden, D. J. Rose, B. Mau, and Y. Shao. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277:1453-1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyd, E. F., and D. L. Hartl. 1997. Recent horizontal transmission of plasmids between natural populations of Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica. J. Bacteriol. 179:1622-1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyd, E. F., C. W. Hill, S. M. Rich, and D. L. Hartl. 1996. Mosaic structure of plasmids from natural populations of Escherichia coli. Genetics 143:1091-1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bull, H. J., M.-J. Lombardo, and S. M. Rosenberg. 2001. Stationary-phase mutation in the bacterial chromosome: recombination protein and DNA polymerase IV dependence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:8334-8341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cairns, J., and P. L. Foster. 1991. Adaptive reversion of a frameshift mutation in Escherichia coli. Genetics 128:695-701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cairns, J., and P. L. Foster. 2003. The risk of lethals for hypermutating bacteria in stationary phase. Genetics 165:2317-2318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cairns, J., J. Overbaugh, and S. Miller. 1988. The origin of mutants. Nature 335:142-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calos, M. P., and J. H. Miller. 1981. Genetic and sequence analysis of frameshift mutations induced by ICR-191. J. Mol. Biol. 153:39-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, D., and D. M. Lilley. 1999. Transcription-induced hypersupercoiling of plasmid DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 285:443-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chopra, I., S. W. Shales, J. M. Ward, and L. J. Wallace. 1981. Reduced expression of Tn10-mediated tetracycline resistance in Escherichia coli containing more than one copy of the transposon. J. Gen. Microbiol. 126:45-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coulondre, C., and J. H. Miller. 1977. Genetic studies of the lac repressor. IV. Mutagenic specificity in the lacI gene of Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 117:577-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2001. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deng, S., R. A. Stein, and N. P. Higgins. 2004. Transcription-induced barriers to supercoil diffusion in the Salmonella typhimurium chromosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:3398-3403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eckert, B., and C. F. Beck. 1989. Overproduction of transposon Tn10-encoded tetracycline resistance protein results in cell death and loss of membrane potential. J. Bacteriol. 171:3557-3559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foster, P. L. 1994. Population dynamics of a Lac− strain of Escherichia coli during selection for lactose utilization. Genetics 138:253-261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foster, P. L. 1997. Nonadaptive mutations occur on the F′ episome during adaptive mutation conditions in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 179:1550-1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foster, P. L. 2004. Adaptive mutation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 186:4846-4852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foster, P. L. 1999. Mechanisms of stationary phase mutation: a decade of adaptive mutation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 33:57-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foster, P. L. 2000. Adaptive mutation in Escherichia coli. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 65:21-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foster, P. L., and W. A. Rosche. 1999. Increased episomal replication accounts for the high rate of adaptive mutation in recD mutants of Escherichia coli. Genetics 152:15-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foster, P. L., and J. M. Trimarchi. 1995. Adaptive reversion of an episomal frameshift mutation in Escherichia coli requires conjugal functions but not actual conjugation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:5487-5490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foster, P. L., and J. M. Trimarchi. 1995. Conjugation is not required for adaptive reversion of an episomal frameshift mutation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 177:6670-6671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foster, P. L., J. M. Trimarchi, and R. A. Maurer. 1996. Two enzymes, both of which process recombination intermediates, have opposite effects on adaptive mutation in Escherichia coli. Genetics 142:25-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frost, L. S., and J. Manchak. 1998. F− phenocopies: characterization of expression of the F transfer region in stationary phase. Microbiology 144:2579-2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hastings, P. J., H. J. Bull, and S. M. Rosenberg. 2000. Adaptive amplification: an inducible chromosomal instability mechanism. Cell 103:723-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hastings, P. J., A. Slack, J. F. Petrosino, and S. M. Rosenberg. 2004. Adaptive amplification and point mutation are independent mechanisms: evidence for various stress-inducible mutation mechanisms. PLoS Biol. 2:e399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hendrickson, H., E. S. Slechta, U. Bergthorsson, D. I. Andersson, and J. R. Roth. 2002. Amplification-mutagenesis: evidence that “directed” adaptive mutation and general hypermutability result from growth with a selected gene amplification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:2164-2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kofoid, E., U. Bergthorsson, E. S. Slechta, and J. R. Roth. 2003. Formation of an F′ plasmid by recombination between imperfectly repeated chromosomal Rep sequences: a closer look at an old friend (F′128pro lac). J. Bacteriol. 185:660-663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuban, W., P. Jonczyk, D. Gawel, K. Malanowska, R. M. Schaaper, and I. J. Fijalkowska. 2004. Role of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase IV in in vivo replication fidelity. J. Bacteriol. 186:4802-4807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lenski, R. E., M. Slatkin, and F. J. Ayala. 1989. Mutation and selection in bacterial populations: alternatives to the hypothesis of directed mutation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:2775-2778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maloy, S. R., and W. D. Nunn. 1981. Selection for loss of tetracycline resistance by Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 145:1110-1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McKenzie, G. J., P. L. Lee, M.-J. Lombardo, P. J. Hastings, and S. M. Rosenberg. 2001. SOS Mutator DNA polymerase IV functions in adaptive mutation and not adaptive amplification. Mol. Cell 7:571-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller, J. H. 1992. A short course in bacterial genetics: a laboratory manual and handbook for Escherichia coli and related bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 35.Mulec, J., M. Starcic, and D. Zgur-Bertok. 2002. F-like plasmid sequences in enteric bacteria of diverse origin, with implication of horizontal transfer and plasmid host range. Curr. Microbiol. 44:231-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Müller-Hill, B., and J. Kania. 1974. Lac repressor can be fused to β-galactosidase. Nature 249:561-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pettersson, M. E., D. I. Andersson, J. R. Roth, and O. G. Berg. 2005. The amplification model for adaptive mutation—simulations and analysis. Genetics 169:1105-1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ponder, R. G., N. C. Fonville, and S. M. Rosenberg. 2005. A switch from high-fidelity to error-prone DNA double-strand break repair underlies stress-induced mutation. Mol. Cell 19:791-804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poteete, A. R., A. C. Fenton, and A. Nadkarni. 2004. Chromosomal duplications and cointegrates generated by the bacteriophage lamdba Red system in Escherichia coli K-12. BMC Mol. Biol. 5:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poteete, A. R., H. R. Wang, and P. L. Foster. 2002. Phage λ Red-mediated adaptive mutation. J. Bacteriol. 184:3753-3755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Powell, S. C., and R. M. Wartell. 2001. Different characteristics distinguish early versus late arising adaptive mutations in Escherichia coli FC40. Mutat. Res. 473:219-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pratt, L. A., and R. Kolter. 1998. Genetic analysis of Escherichia coli biofilm formation: roles of flagella, motility, chemotaxis and type I pili. Mol. Microbiol. 30:285-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Radicella, J. P., P. U. Park, and M. S. Fox. 1995. Adaptive mutation in Escherichia coli: a role for conjugation. Science 268:418-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rice, J. A. 1995. Mathematical statistics and data analysis. Wadsworth Publishing Company, Belmont, CA.

- 45.Rodriguez, C., J. Tompkin, J. Hazel, and P. L. Foster. 2002. Induction of a DNA nickase in the presence of its target site stimulates adaptive mutation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 184:5599-5608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosche, W. A., and P. L. Foster. 1999. The role of transient hypermutators in adaptive mutation in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:6862-6867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rosenberg, S. M., and P. J. Hastings. 2004. Adaptive point mutation and adaptive amplification pathways in the Escherichia coli Lac system: stress responses producing genetic change. J. Bacteriol. 186:4838-4843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roth, J. R., and D. I. Andersson. 2004. Adaptive mutation: how growth under selection stimulates Lac+ reversion by increasing target copy number. J. Bacteriol. 186:4855-4860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roth, J. R., E. Kugelberg, A. B. Reams, E. Kofoid, and D. I. Andersson. 2006. Origin of mutations under selection: the adaptive mutation controversy. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 60:477-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seifert, H. S., and R. D. Porter. 1984. Enhanced recombination between lambda plac5 and F42lac: identification of cis- and trans-acting factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:7500-7504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Slechta, E. S., K. L. Bunny, E. Kugelberg, E. Kofoid, D. I. Andersson, and J. R. Roth. 2003. Adaptive mutation: general mutagenesis is not a programmed response to stress but results from rare coamplification of dinB with lac. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:12847-12852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Slechta, E. S., J. Harold, D. I. Andersson, and J. R. Roth. 2002. The effect of genomic position on reversion of a lac frameshift mutation (lacIZ33) during non-lethal selection (adaptive mutation). Mol. Microbiol. 44:1017-1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Slechta, E. S., J. Liu, D. I. Andersson, and J. R. Roth. 2002. Evidence that selected amplification of a bacterial lac frameshift allele stimulates Lac+ reversion (adaptive mutation) with or without general hypermutability. Genetics 161:945-956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tisty, D. T., A. M. Albertini, and J. H. Miller. 1984. Gene amplification in the lac region of E. coli. Cell 37:217-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tompkins, J. D., J. E. Nelson, J. C. Hazel, S. L. Leugers, J. D. Stumpf, and P. L. Foster. 2003. Error-prone polymerase, DNA polymerase IV, is responsible for transient hypermutation during adaptive mutation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 185:3469-3472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Torkelson, J., R. S. Harris, M.-J. Lombardo, J. Nagendran, C. Thulin, and S. M. Rosenberg. 1997. Genome-wide hypermutation in a subpopulation of stationary-phase cells underlies recombination-dependent adaptive mutation. EMBO J. 16:3303-3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]