Abstract

HIV replication and LTR-mediated gene expression can be modulated by CD8+T cells in a cell type-dependent manner. We have previously shown that supernatants of activated CD8+ T cells of HIV-infected individuals greatly enhanced p24 levels in human macrophages infected with NSI or SI primary isolates of HIV-1. Here we have examined the effect of culture with CD8+T cell supernatants on HIV-1 LTR-mediated gene expression in monocytic cells. CD8+T cell supernatants enhanced LTR-mediated gene expression in U38 cells activated with Tat in the absence or presence of phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and ionomycin or TNF-α. Further, enhancement of LTR-mediated gene expression and virus replication in U38 cells and U1 cells, respectively, was pertussis toxin-sensitive. The enhancement of gene expression and virus replication was associated with increased levels of TNF-α and was significantly abrogated by antibody to TNF-α. In contrast, the suppression of LTR-mediated gene expression by CD8+T cell supernatants in Jurkat T cells was not pertussis toxin-sensitive and TNF-α levels were not affected. These results demonstrate that factors produced by CD8+T cells utilize different cellular pathways to mediate their effects on HIV transcription and replication in different cell types.

Keywords: HIV, CD8+ T cell, macrophage, transcription, pertussis toxin

INTRODUCTION

A non-lytic suppression of HIV-1 replication by CD8+ T lymphocytes was first described by Walker et al. [1]. This activity was further shown to be mediated by a soluble factor(s) and was subsequently termed the CD8 anti-viral factor (CAF) [2,3]. The suppression of replication was later demonstrated to be due to a chemokine-mediated block in the access to co-receptors required for infection of CD4+ cells. Recent studies have demonstrated that infection by T cell-tropic strains of HIV-1 is mediated by the CXC chemokine receptor CXCR4 (Lestr/fusin) [4–7]. Infection with macrophage-tropic strains can be mediated by the CC chemokine receptors CCR5 [8–10] or CCR3 [11,12]. The involvement of chemokine receptors for infection of cells by HIV-1 received further support by the demonstration that individuals homozygous for a 32-bp deletion mutant of CCR5 were resistant to infection with HIV-1 [13–16].

In addition to inhibition of HIV-1 replication in CD4+ T cells and T cell lines, CD8+ T cells mediate inhibition of LTR-directed gene expression in T cell lines [17–21]. We previously reported on the opposite effects of CD8+ T cells on gene expression in T cells versus monocytic cells [22]. The enhancement of gene expression in monocytic cells treated with CD8+ T cell culture supernatants correlated strongly with the corresponding level of suppression of gene expression in Jurkat T cells. Further, we have shown that in both monocytic cells [22] and T cells [23] the modulation of LTR-mediated gene expression was not induced by the β-chemokines RANTES, macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α) or MIP-1β or by a combination of these chemokines. It was recently reported that the chemokines individually or in combination did not suppress replication of HIV-1SF33 in CD4+ T cells [24]. In addition, the activity of CAF has been shown to be distinct from the β-chemokines and known cytokines [25].

Cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage serve as reservoirs of HIV due to their inherent resistance to the lytic effects of HIV [26]. In addition, macrophage-tropic HIV-1 isolates can be demonstrated throughout HIV infection [27]. We have previously shown that culture of HIV-1-infected human macrophages with CD8+ T cell supernatants results in significantly enhanced virus replication and is mediated by a soluble factor produced by CD8+ T cells [28]. This was observed for a variety of primary isolates of HIV. The enhancement of virus replication in monocytic cells induced by CD8+ T cells is of particular interest since this enhancement may contribute to the persistence of HIV-1 in cells of this lineage. Here we have further defined the cellular pathways to determine their effects on CD8+-induced enhancement and suppression of LTR-mediated gene expression in monocytic cells and T cells, respectively. We demonstrate that the enhancement of gene expression by CD8+ T cell-derived factor(s) is mediated by the induction of increased levels of TNF-α in human macrophages and monocytic cell lines, while TNF-α levels are not modulated by these CD8-derived factors in Jurkat T cells. Further, the enhancement of gene expression in human monocytes and monocytic cell lines is sensitive to the G-protein inhibitor pertussis toxin (PT).

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Subjects

HIV-infected asymptomatic subjects (CD4+ > 350/μl) were referred by Dr Fiona Smaill at the McMaster Special Immunology Services Clinic (Hamilton, Ontario, Canada). Ethical approval for these studies was conferred by McMaster University Health Sciences Centre.

Cell culture and reagents

Jurkat E-6 cells and monocytic cell lines (U38 and U1) were cultured in RPMI 1640 (6 × 105 cells/ml) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. U38 cells are stably transfected with the HIV-1 LTR linked to the bacterial gene chloramphenicol acetyl transferase (CAT) [29,30] (AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH, Bethesda, MD; contributors Dr B. K. Felber and Dr G. N. Pavlakis). The U1 cell line [31] is chronically infected with HIV-1 (AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, contributor Dr T. M. Folks).

Final concentrations of reagents used were: PT (10 ng/ml; Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA), cholera toxin (CT; 100 ng/ml; Calbiochem), cyclosporin A (CsA; 10 μg/ml; Sandoz, East Hanover, NJ), phorbol myristate acetate (PMA; 25 ng/ml; Sigma, St Louis, MO), ionomycin (2 μm; Sigma), human recombinant TNF-α and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (10 and 2.5 ng/ml, respectively; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and anti-human TNF-α (500 ng/ml; R&D Systems).

Generation of CD8+ T cell-derived supernatants from infected subjects

Human CD8+ T lymphocytes were isolated from peripheral blood of HIV+ individuals by Ficoll gradient followed by positive selection using CD8+-conjugated magnetic beads (Miltenyi, Auburn, CA). CD8+ lymphocytes (5 × 105 cells/ml) were cultured in RPMI 1640 containing 20% FCS, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 5 μg/ml phytohaemagglutinin (PHA) and 20 U/ml recombinant human IL-2 (rIL-2). Following 3 days of culture the cells were washed and recultured in medium lacking PHA for 3 days. Prior to the collection of supernatants, the cell concentration was adjusted to 4 × 105 cells/ml. CD8+ T cell supernatants were individually screened for the level of suppression and enhancement of LTR-CAT expression in Jurkat and U38 cells, respectively, prior to use in the described experiments. Supernatants were split into aliquots and were stored at −70°C.

Transfections and CAT assay

The vectors pLTRCAT and pSVtat have been described previously [32,33]. Jurkat T cells and U38 monocytes (3 × 107) were transfected using a DEAE dextran procedure [34]. In U38 transfections, the vector pSVtat was provided at 5 μg per transfection. Transfected cells were cultured with CD8+ T cell supernatant at a ratio of 1:1 (supernatant:RPMI). In experiments using inhibitors of activation pathways the reagents were added prior to the addition of CD8+ T cell supernatant. Twenty-four hours following transfection the cells were treated with PMA and ionomycin or TNF-α for 18 h. The cells were then lysed by four rounds of freeze/thaw and the lysate supernatant was used to measure CAT activity using a CAT ELISA system (Boehringer Mannheim, Laval, Quebec, Canada). U1 cells were transfected with 10 μg pLTRCAT and cultured with CD8+ T cell supernatant in the absence and presence of PT. Following 3 days of culture, aliquots of the supernatants of U1 cells were assayed for p24 antigen by ELISA (Organon Teknika, Durham, NC). The cells were lysed as described and lysates used to measure CAT activity. Transfection efficiency was determined by co-transfection of 10 μg of the vector pCH110 [35] in which β-galactosidase expression is driven by an SV40 promoter. β-galactosidase expression was assayed by measuring absorbance at 420 nm using o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG; Sigma) as a substrate. The significance of differences between treatment groups was calculated using Student's t-test.

Detection of TNF-α in cell culture supernatants

TNF-α concentrations were measured by ELISA according to the manufacturer's directions (Genzyme Diagnostics, Cambridge, MA). The sensitivity limit of the ELISA was 0.5 pg/ml. TNF-α levels were determined on CD8+ T cell supernatants and cell culture supernatants using a TNF-α standard curve.

RESULTS

Enhancement of LTR-mediated gene expression in U38 cells is sensitive to PT

We previously demonstrated that CD8+ T cell supernatants of HIV-1-infected subjects increased HIV replication in monocytic cells in a manner independent of the β-chemokines MIP-1α, MIP-1β and RANTES [22]. It has been reported that signal transduction via the G-protein-coupled RANTES receptor is not required for the anti-viral function of the chemokine [13]. We investigated whether CD8-mediated enhancement of HIV-1 LTR-driven gene expression in monocytic cells was associated with a G protein-coupled receptor using the G protein modulator PT [36,37].

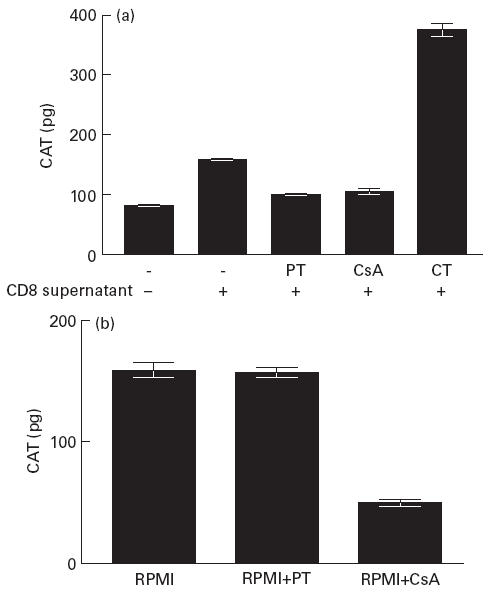

These experiments were performed comparatively with the G protein activator CT which has been reported to enhance LTR-mediated gene expression in monocytic cells [38] and with the immunosuppressive drug CsA, which abrogates LTR-mediated gene expression [39]. U38 cells were transfected with a vector expressing HIV Tat (pSVtat) and subsequently treated with PMA and ionomycin in the presence of CD8+ T cell-derived supernatants. As shown in Fig. 1a, culture of the transfected cells with supernatant derived from CD8+ T cells of an HIV-1-infected subject enhanced HIV-1 LTR-mediated gene expression. While CT further enhanced gene expression, PT abrogated the CD8-mediated enhancement to similar levels as CsA (P < 0.001). Further examination revealed that while PT had no effect on LTR-mediated gene expression in the absence of CD8+ T cell supernatants, CsA had significant down-modulating activity (Fig. 1b). The sensitivity of CD8-mediated enhancement to abrogation by PT was found to be dose-dependent, as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

(a) Effect of the G protein inhibitor pertussis toxin (PT) on CD8-mediated enhancement of LTR-mediated gene expression. U38 cells transfected with pSVtat were cultured with RPMI or with CD8+ T cell supernatant:RPMI (1:1) in the absence and presence of cholera toxin (CT), cyclosporin A (CsA) or PT for 18 h prior to stimulation with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and ionomycin. Chloramphenicol acetyl transferase (CAT) levels were measured in cell lysates following 18 h stimulation. Results show the mean and s.d. of four independent experiments. (b) U38 cells transfected with pSVtat were cultured in RPMI or RPMI containing either CsA or PT for 24 h and CAT levels were measured in cell lysates following 18 h stimulation with PMA and ionomycin. Results show the mean and s.d. of four independent experiments.

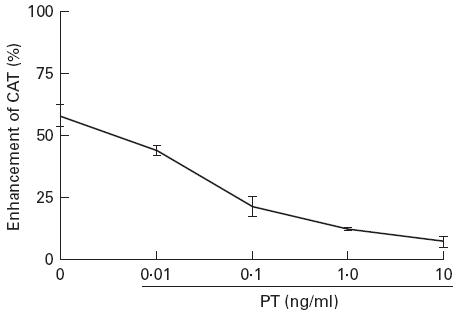

Fig. 2.

Pertussis toxin (PT) sensitivity of CD8-mediated enhancement of transcription is dose-dependent. U38 cells were transfected with pSVtat and cultured with RPMI in the presence and absence of CD8+ T cell supernatant. PT was included at the indicated doses. Cells were lysed for measurement of chloramphenicol acetyl transferase (CAT) 18 h following treatment with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and ionomycin. Results show the mean and s.d. of three independent experiments.

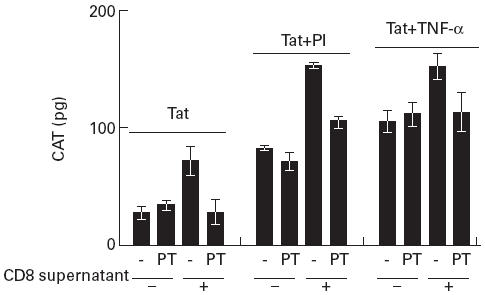

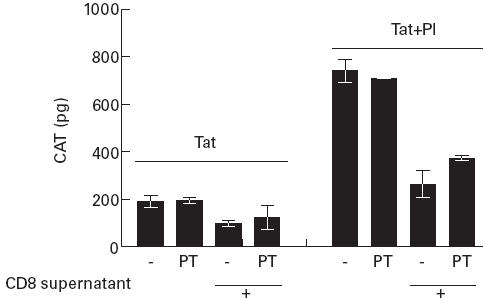

In Fig. 3 the effect of PT on pSVtat-transfected U38 cells in the absence and presence of CD8+ T cell supernatant is shown. PT had no effect on Tat-mediated transactivation in the absence of CD8+ T cell supernatant. However, the enhancement of CAT expression in Tat-transfected cells induced by CD8+ T cell supernatant was abrogated by PT. In pSVtat-transfected U38 cells treated with PMA and ionomycin or TNF-α, PT had no effect on CAT expression in the absence of CD8+ T cell supernatant. In PMA and ionomycin and TNF-α treatment groups the enhancement of CAT expression by CD8+ T cell supernatant was abrogated by pertussis toxin (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Pertussis toxin (PT) inhibits other mechanisms of LTR activation. pSVtat-transfected U38 cells were cultured with RPMI in the absence or presence of PT or with CD8+ T cell supernatant at 1:1 with RPMI in the absence and presence of PT for 24 h. Cells were then split into three treatment groups receiving no treatment, phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and ionomycin (PI) or TNF-α for a further 18 h before measuring chloramphenicol acetyl transferase (CAT) levels in cell lysates. Results are presented as the mean and s.d. of three independent experiments.

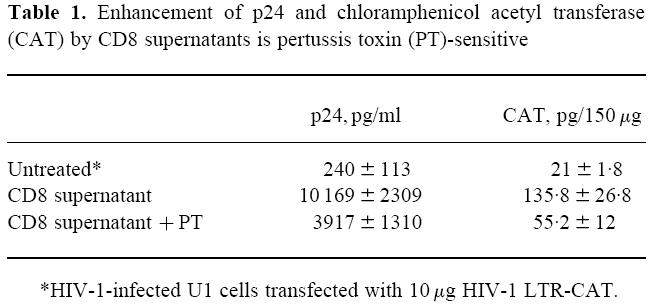

Pertussis toxin abrogates CD8-mediated effect on virus replication and CAT expression in U1 cells

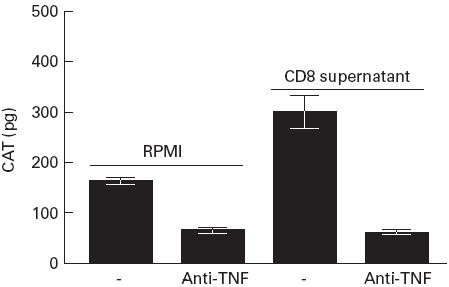

In view of the abrogation of the effect of CD8+ T cell supernatants on U38 cells by PT, we transfected HIV-1-infected U1 monocytic cells with pLTRCAT and cultured the cells in the absence and presence of CD8+ T cell supernatant (Table 1). Both p24 and CAT levels were increased by CD8+ T cell supernatants. However, incorporation of PT in the culture resulted in a reduction in the enhancement of p24 and CAT expression induced by the supernatant. In fact, the reduction of p24 levels by PT was mirrored by a similar decrease in HIV LTR-driven CAT expression (Table 1). Thus, CD8+ T cell-mediated enhancement targets both HIV replication and gene expression in parallel. In pSVtat-transfected U38 cells treated with PMA and ionomycin, the enhancement of gene expression by CD8-derived supernatant was significantly abrogated (P < 0.01) by anti-TNF-α antibody (Fig. 4).

Table 1.

Enhancement of p24 and chloramphenicol acetyl transferase (CAT) by CD8 supernatants is pertussis toxin (PT)-sensitive

*HIV-1-infected U1 cells transfected with 10 µg HIV-1 LTR-CAT.

Fig. 4.

Antibody to TNF-α abrogates the CD8-mediated enhancement of LTR activity in U38 cells. U38 cells transfected with pSVTat were cultured with RPMI or with RPMI containing anti-TNF-α (500 ng/ml) in the presence and absence of CD8+ T cell supernatant (1:1 with medium) for 24 h. Cells were treated with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and ionomycin for a further 18 h before measuring chloramphenicol acetyl transferase (CAT) levels in cell lysates. Results are presented as the mean and s.d. of four independent experiments.

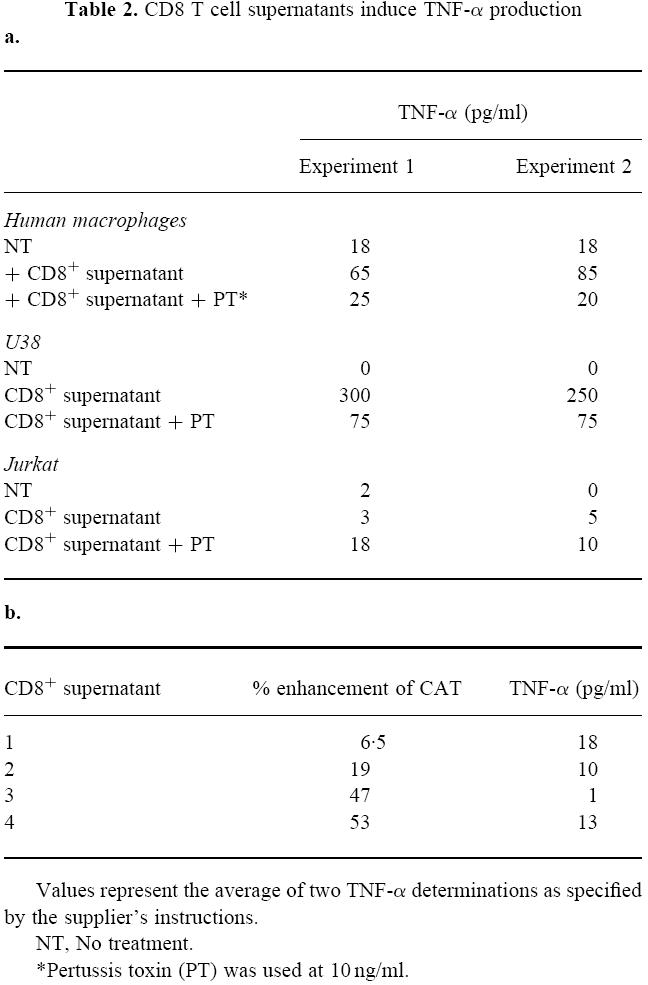

CD8+ T cell supernatants enhance TNF-α levels in human macrophages and monocytic cells in the absence of other stimuli

As shown in Table 2a, culture with CD8+ supernatant alone enhanced TNF-α production by human macrophages and this enhancement was abrogated by PT. Similarly, in untreated U38 cells cultured with CD8+ T cell supernatants for 40 h, TNF-α levels were enhanced and this increase was partly abrogated by PT. TNF-α levels were lower in Jurkat cells and no modulation of these levels resulted from culture with supernatants. In addition, PT was not found to enhance or reduce LTR-mediated CAT expression in pSVtat-transfected Jurkat T cells treated with PMA and ionomycin or TNF-α (Fig. 5). Further, the suppression of gene expression induced by CD8+ T cell supernatant was not affected by PT (Fig. 5). We examined TNF-α levels present in CD8+ T cell supernatants with a range of enhancing activity (Table 2b). No correlation was found between TNF-α levels present and the ability of the CD8+ T cell supernatant to enhance LTR-mediated transcription in U38 cells.

Table 2.

CD8 T cell supernatants induce TNF-α production

Values represent the average of two TNF-α determinations as specified by the supplier's instructions.

NT, No treatment.

*Pertussis toxin (PT) was used at 10 ng/ml.

Fig. 5.

Pertussis toxin (PT) does not influence HIV LTR activity in Jurkat cells. Jurkat cells co-transfected with pLTR-chloramphenicol acetyl transferase (CAT) and pSVtat were cultured in RPMI or RPMI containing PT for 24 h. The cells were split into two treatment groups receiving either no treatment or phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and ionomycin (PI). Following 18 h of culture CAT levels in cell lysates were measured. Results show the mean and s.d. of three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

This study was undertaken to clarify further the mechanism of enhancement of HIV-1 replication and LTR-mediated gene expression in monocytic cells by CD8+ T cell supernatants from HIV-1-infected individuals. We previously reported that while CD8+ T cell supernatants suppress HIV-1 LTR-mediated gene expression in Jurkat T cells [18,19], an opposite effect was observed on gene expression in monocytic cells [22]. In addition, we demonstrated that the β-chemokines, MIP-1α, MIP-1β and RANTES, do not have an effect on LTR-mediated gene expression, nor did a combination of antibodies to these chemokines abrogate the enhancement of HIV-1 replication in monocytic cells [22]. In this current work we have demonstrated that the enhancement of LTR-mediated gene expression is sensitive to PT, indicating a G protein-coupled mechanism of activation. In addition, PT had no effect on LTR-driven gene expression in the absence of CD8+ T cell culture supernatants. We also show that both the increase in HIV-1 replication and LTR-mediated gene expression in transfected/infected U1 are PT-sensitive.

Guanine nucleotide-binding proteins (G proteins) couple several receptors to intracellular pathways (reviewed in [40]). Chemokines can invoke calcium mobilization and protein kinase C activation in monocytes. These events are induced by second messengers generated following the activation of phospholipase C by G proteins [37,41–43]. The response of monocytes to chemokines is sensitive to PT, which irreversibly modifies the function of the Gi subset of G proteins by ADP-ribosylation [41,44]. Chowdhury et al. [44] demonstrated that the inhibition of TNF-α-mediated virus replication by PT in U1 cells resulted from ADP-ribosylation of Gi. We examined TNF-α levels and found that the enhancement of both viral replication and LTR-mediated transcription by CD8+ T cell factors was associated with an elevated level of TNF-α production in the cells which was abrogated by PT. The enhancement of CAT and p24 levels in transfected U1 cells was surprisingly similar, as was the level of abrogation of both CAT and p24 by PT, suggesting that the CD8+ factor(s) mediating the enhancement of both viral gene transcription and virus replication in monocytic cells might be the same. This argument is further strengthened by the observed increase in TNF-α levels in cells cultured with CD8+ T cell supernatant. The induction of TNF-α is probably not caused by TNF-α in the culture supernatants, since these levels were approx. 100–1000-fold lower than those commonly used to activate transcription or replication. The CD8-derived factor(s) thus has the ability to enhance TNF-α, which in turn increases virus replication and LTR-mediated gene expression. In addition, antibody to TNF-α abrogated the enhancement of gene expression mediated by CD8-derived culture supernatants.

The demonstration that TNF-α levels were enhanced by culture with CD8+ T cell supernatants in U38 cells and human macrophages, but not in Jurkat T cells, further suggests that CD8-derived factors have the potential to influence gene expression in a cell type-dependent manner. In addition, the effect of CD8+ T cells on HIV gene expression is not limited to the β-chemokines. IL-16, a product of CD8+ T lymphocytes and a ligand for CD4 [45], has recently been shown to strongly inhibit HIV-1 promoter activity [46] and mRNA expression in T cells [47]. In addition, increased levels of IL-16 are produced by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of long-term non-progressors [48]. Schmidtmayerova et al. [49] have reported that β-chemokine levels are enhanced by HIV infection, and further, that the ability of the β-chemokines to inhibit or stimulate HIV replication is cell type-dependent [50]. Recent reports have indicated that β-chemokines have no effect on [10] or stimulate [49] HIV-1 replication in macrophages. We have previously reported that the β-chemokines RANTES, MIP-1α and MIP-1β do not influence LTR-mediated gene expression, nor do antibodies to these chemokines abrogate the CD8-mediated enhancement of gene expression in monocytic cells [22] or the suppression of gene expression in Jurkat T cells [23]. Additionally, we showed that supernatant of CD8+ T cells of HIV-1-infected individuals could enhance rather than inhibit HIV replication in human macrophages [28]. In contrast, Moriuchi et al. [51] demonstrated suppression of p24 production in GM-CSF-treated human monocytes infected with HIV-1BAL by culture supernatant of a Herpesvirus saimiri-transformed CD8+ T cell clone. The opposite effects may be due to differences in culture conditions or the possible presence of cytokines or chemokines, induced by transformation, with down-regulatory effects on virus replication.

HIV-1 transcription and replication can be positively and negatively modulated by a variety of cytokines. In addition, dichotomous effects on replication have been observed for IL-4, IL-10, interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) (reviewed in [52]). For example, the inhibition of virus replication induced by IL-10 in human macrophages [53,54] has been linked to inhibition of cell differentiation [55], inhibition of reverse transcription [56] and inhibition of TNF-α and IL-6 secretion [57]. In contrast, IL-10 can synergize with TNF-α to activate HIV replication in monocytic cells [58]. GM-CSF has been reported to inhibit HIV replication in monocytic cells [59], but in the presence of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), GM-CSF enhances replication in a TNF-α-independent manner. IFN-γ can suppress virus replication in certain T cell lines [60] and in promonocytic U937 cells [61,62]. However, while pretreatment of macrophages with IFN-γ inhibited virus replication, the addition of IFN-γ after infection has been reported to increase replication [63]. TGF-β has potent suppressive effects on HIV replication in cells treated with IL-6 but not in cells treated with TNF-α [64]. Finally, IL-4 can suppress virus replication in human macrophages and can synergize with IL-10 in this suppression [54]. In contrast, IL-4 and IFN-γ have been reported to increase HIV-1 replication in macrophages [56].

These dichotomous effects may be dependent on cell type, culture conditions and the state of differentiation or activation of the infected cell. Thus identification of CD8+ T cell factors which modulate virus replication in monocytic cells and T cells is clouded not only by the above conditions but also by the complex interplay of individual and combinations of cytokines on HIV replication. It is not known if the same factor or group of factors which act at the level of replication are the same as those affecting transcription. Further, it remains to be determined whether the factors that enhance replication and transcription in monocytic cells are identical to those which suppress these functions in T cells. We have approached the identification of CD8+ T cell-derived factors in two ways. First by the examination of cellular pathways which may be recruited by the CD8+ factors. These studies will complement our current ongoing biochemical characterization of the factors. Using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) fractionation of CD8+ T cell supernatants which suppress gene expression in Jurkat cells, we have identified a fraction which strongly suppresses gene expression in T cells and enhances gene expression in monocytic cells. The factor is a 10–30-kD protein which is heat-resistant and acid-stable (data not shown).

HIV infection can enhance the production of β-chemokines by macrophages [49] which could result in a suppression of HIV-1 replication in T cells. However, at the same time CD8+-derived factors, which may include unidentified cytokines and chemokines, may enhance replication in macrophages, providing a new wave of virus to infect CD4+ T cells. In addition, the effect of CD8-derived factors may be multiplied further upon many cycles of replication. In early infection this activity might play a role in the persistence of macrophage-tropic strains of HIV-1. The CD8+ T cell factors which modulate LTR-mediated gene expression have not been studied in all cell types infectable by HIV, such as dendritic cells. Given the inflammatory effects of chemokines and cytokines, combined with the enhancing effects of CD8+ factors on HIV replication in human macrophages, efforts to control HIV infection using CD8-derived factors must be approached with caution.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Canadian Association for AIDS Research (CANFAR) and the Medical Research Institute of Canada.

REFERENCES

- 1.Walker CM, Moody DJ, Stites DP, Levy JA. CD8+ lymphocytes can control HIV infection in vitro by suppressing virus replication. Science. 1986;234:1563–6. doi: 10.1126/science.2431484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brinchmann JE, Gaudernack G, Vartdal F. CD8+ T cells inhibit HIV replication in naturally infected CD4+ T cells: evidence for a soluble inhibitor. J Immunol. 1990;144:2961–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker CM, Levy JA. A diffusable lymphokine produced by CD8+ T lymphocytes suppresses HIV replication. Immunol. 1989;66:628–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berson JF, Long D, Doranz BJ, Rucker J, Jirik FR, Doms RW. A seven-transmembrane domain receptor involved in fusion and entry of T-cell-tropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strains. J Virol. 1996;70:6288–95. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6288-6295.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bleul CC, Farzan M, Choe M, Parolin C, Clark-Lewis I, Sodroski J, Springer TA. The lymphocyte chemoattractant SDF-1 is a ligand for LESTR/fusin and blocks HIV entry. Nature. 1996;382:829–32. doi: 10.1038/382829a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feng Y, Broder CC, Kennedy PE, Berger EA. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane domain, G-protein coupled receptor. Science. 1996;272:872–7. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oberlin E, Amara A, Bachelerie F. The CXC chemokine SDF-1 is the ligand for LESTR/fusin and prevents infection by T-cell-line-adapted HIV-1. Nature. 1996;382:833–5. doi: 10.1038/382833a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alkhatib G, Combadiere C, Broder CC, Feng Y, Kennedy PE, Murphy PM, Berger EA. CC CKR5: a RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β receptor as a fusion cofactor for macrophage-tropic HIV-1. Science. 1996;272:1955–8. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deng HK, Liu R, Ellmeier W, et al. Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature. 1996;381:661–6. doi: 10.1038/381661a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dragic T, Litwin V, Allaway GP, et al. HIV-1 entry into CD4+ cells is mediated by the chemokine receptor CC-CKR-5. Nature. 1996;381:667–73. doi: 10.1038/381667a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choe H, Farzan M, Sun Y, et al. The β-chemokine receptors CCR3 and CCR5 facilitate infection by primary HIV-1 isolates. Cell. 1996;85:1135–48. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doranz BJ, Rucker J, Yi Y, et al. A dual-tropic primary HIV-1 isolate that uses fusin and the β-chemokine receptors CKR-5, CKR-3, and CKR-2b as fusion cofactors. Cell. 1996;85:1149–58. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cocchi F, DeVico AL, Garzino-Demo A, Arya SK, Gallo RC, Lusso P. Identification of RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β as the major HIV-suppressive factors produced by CD8+ T cells. Science. 1995;270:1811–5. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dean M, Carrington M, Winkler C, et al. Genetic restriction of HIV-1 infection and progression to AIDS by a deletion allele of the CKR5 structural gene. Science. 1996;273:1856–61. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5283.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu R, Paxton WA, Choe S, et al. Homozygous defect in HIV-1 coreceptor accounts for resistance of some multiply exposed individuals to HIV-1 infection. Cell. 1996;86:367–77. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samson M, Labbe O, Mollereau C, Vassart G, Parmentier M. Molecular cloning and functional expression of a new human CC-chemokine receptor gene. Biochem. 1996;35:3362–7. doi: 10.1021/bi952950g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen C-H, Weinhold KJ, Bartlett JA, Bolognesi DP, Greenberg M. CD8+ T lymphocyte-mediated inhibition of HIV-1 long terminal repeat transcription: a novel antiviral mechanism. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1993;9:1079–86. doi: 10.1089/aid.1993.9.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Copeland KFT, McKay PJ, Rosenthal KL. Suppression of activation of the human immunodeficiency virus long terminal repeat by CD8+ T-cells is not lentivirus specific. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1995;11:1321–6. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Copeland KFT, McKay PJ, Rosenthal KL. Suppression of the human immunodeficiency virus long terminal repeat by CD8+ T-cells is dependent on the NFAT-1 element. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1996;12:143–8. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knuchel M, Bednarik DP, Chikkala N, Ansari AA. Biphasic in vitro regulation of retroviral replication by CD8+ cells from nonhuman primates. J AIDS. 1994;7:438–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mackewicz CE, Blackbourn DJ, Levy JA. CD8+ T cells suppress human immunodeficiency virus replication by inhibiting viral transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2308–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.6.2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Copeland KFT, Leith J, McKay PJ, Rosenthal KL. CD8+ T-cell supernatants of HIV-1-infected individuals have opposite effects on long terminal repeat-mediated transcription in T cells and monocytes. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1997;13:71–77. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leith JG, Copeland KFT, Mckay PJ, Richards CD, Rosenthal KL. CD8+ T-cell-mediated suppression of HIV-1 long terminal repeat-driven gene expression is not modulated by the CC chemokines RANTES, macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α and MIP-1β. AIDS. 1997;11:575–80. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199705000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paliard X, Lee AY, Walker CM. RANTES, MIP-1α and MIP-1β are not involved in the inhibition of HIV-1SF33 replication mediated by CD8+ T-cell clones. AIDS. 1996;10:1317–21. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199610000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mackewicz C, Levy JA. CD8+ cell anti-HIV activity: nonlytic suppression of virus replication. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1992;8:1039–50. doi: 10.1089/aid.1992.8.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gendelman HE, Orenstein JM, Baca LM, et al. The macrophage in the persistence and pathogenesis of HIV infection. AIDS. 1989;3:475–95. doi: 10.1097/00002030-198908000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schuitemaker H, Kootstra NA, De Goede REY, De Wolf F, Miedema F, Tersmette M. Monocytotropic human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) variants detectable in all stages of HIV infection lack T-cell line tropism and syncytium-inducing ability in primary T-cell culture. J Virol. 1991;65:356–63. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.1.356-363.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Copeland KFT, McKay PJ, Newton JJ, Rosenthal KL. Enhancement of HIV-1 replication in human macrophages is induced by CD8+ T-cell soluble factors. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;114:87–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00699.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Felber BK, Pavlakis GN. A quantitative bioassay for HIV-1 based on trans-activation. Science. 1988;239:184–7. doi: 10.1126/science.3422113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwartz S, Felber BK, Fenyo EM, Pavlakis GN. Rapidly and slowly replicating human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates can be distinguished according to target-cell tropism in T-cell and monocyte cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7200–3. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.18.7200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Folks TM, Justement J, Kinter A, Dinarello CA, Fauci AS. Cytokine-induced expression of HIV-1 in a chronically infected promonocytic cell line. Science. 1987;238:800–2. doi: 10.1126/science.3313729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berkhout B, Silverman RH, Jeang K-T. Tat trans-activates the human immunodeficiency virus through a nascent RNA target. Cell. 1989;59:273–82. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90289-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peterlin M, Luciw PA, Barr JP, Walker MD. Elevated levels of mRNA can account for the transactivation of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:9734–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.24.9734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Queen C, Baltimore D. Immunoglobulin gene transcription is activated by downstream sequence elements. Cell. 1983;33:741–8. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herbomel P, Bourachof B, Yaniv M. Two distinct enhancers with different cell specificities coexist in the regulatory region of polyoma. Cell. 1984;39:653–61. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90472-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caterina MJ, Devreotes PN. Molecular insights into eukaryotic chemotaxis. FASEB J. 1991;5:3078–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sozzani S, Molino M, Locati M, et al. Receptor-activated calcium influx in human monocytes exposed to monocyte chemotactic protein-1 and related cytokines. J Immunol. 1993;150:1544–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chowdhury IH, Koyanagi Y, Horiuci S, et al. cAMP stimulates human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) from latently infected cells of monocyte-macrophage lineage: synergism with TNF-α. Virol. 1993;194:345–9. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schreiber SL, Crabtree GR. The mechanism of action of cyclosporin A and FK506. Immunol Today. 1992;13:136–41. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90111-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taylor CW. The role of G proteins in transmembrane signalling. Biochem J. 1990;272:1–13. doi: 10.1042/bj2720001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sozzani S, Luini W, Molino M, et al. The signal transduction pathway involved in the migration induced by a monocyte chemotactic cytokine. J Immunol. 1991;147:2215–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verghese MW, Charles L, Jakoi L, Dillon SB, Snyderman R. Role of guanine nucleotide regulatory protein in the activation of phospholipase C by different chemoattractants. J Immunol. 1987;138:4374–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Verghese MW, Smith CD, Charles LA, Jakoi L, Snyderman R. A guanine nucleotide regulatory protein controls polyphosphoinositide metabolism, Ca2+ mobilization and cellular responses to chemoattractants in human monocytes. J Immunol. 1986;137:271–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chowdhury IH, Koyanagi Y, Hazeki O, Ui M, Yamamoto N. Pertussis toxin inhibits induction of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in infected monocytes. Virol. 1994;203:378–83. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Center DM, Berman JS, Kornfeld H, Theodore AC, Cruikshank WW. The lymphocyte chemoattractant factor. J Lab Clin Med. 1995;125:167–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maciaszek JW, Parada NA, Cruikshank WW, Center DM, Kornfeld H, Viglianti GA. IL-16 represses HIV-1 promoter activity. J Immunol. 1991;158:5–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou P, Goldstein S, Devadas K, Tewari D, Notkins AL. Human CD4+ cells transfected with IL-16 cDNA are resistant to HIV-1 infection: inhibition of mRNA expression. Nature Med. 1997;3:659–64. doi: 10.1038/nm0697-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scala E, D'Offizi G, Rosso R, et al. C-C chemokines, IL-16 and soluble antiviral factor activity are increased in cloned T cells from subjects with long-term nonprogressive HIV infection. J Immunol. 1997;158:4485–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schmidtmayerova H, Nottet HSL, Nuovo G, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection alters chemokine β peptide expression in human monocytes: implications for recruitment of leukocytes into brain and lymph nodes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:700–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmidtmayerova H, Sherry B, Bukrinsky M. Chemokines and HIV replication. Nature. 1996;382:767. doi: 10.1038/382767a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moriuchi H, Moriuchi M, Combadiere C, Murphy PM, Fauci AS. CD8+ T-cell-derived soluble factor(s), but not β-chemokines RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β, suppress HIV-1 replication in monocyte/macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:15341–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fauci AS. Host factors and the pathogenesis of HIV-induced disease. Nature. 1996;384:529–34. doi: 10.1038/384529a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Akridge RE, Oyafuso LKM, Reed SG. IL-10 is induced during HIV infection and is capable of decreasing viral replication in human macrophages. J Immunol. 1994;153:5782–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kootstra NA, Van'tWout AB, Huisman HG, Miedema F, Schuitemaker H. Interference of interleukin-10 with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in primary monocyte-derived macrophages. J Virol. 1994;68:6967–75. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.11.6967-6975.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chang J, Naif HM, Li S, Jozwiak R, Ho-Shon M, Cunningham AL. The inhibition of HIV replication in monocytes by interleukin 10 is linked to inhibition of cell differentiation. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1996;12:1227–35. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Montaner LJ, Griffin P, Gordon S. Interleukin-10 inhibits initial reverse transcription of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and mediates a virostatic latent state in primary blood-derived human macrophages in vitro. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:3393–400. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-12-3393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weissman DG, Poli G, Fauci AS. Interleukin 10 blocks HIV replication in macrophages by inhibiting the autocrine loop of tumor necrosis factor α and interleukin 6 induction of virus. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1994;10:1199–206. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Finnegan A, Roebuck KA, Nakai BE, et al. IL-10 cooperates with TNFα to activate HIV-1 from latently and acutely infected cells of monocyte/macrophage lineage. J Immunol. 1996;156:841–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Matsuda S, Akagawa K, Honda M, Yokota Y, Takebe Y, Takemori T. Suppression of HIV replication in human monocyte-derived macrophages induced by granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1995;11:1031–8. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yamada O, Hattori N, Kurimura T, Kita M, Kishida T. Inhibition of growth of HIV by human natural interferon in vitro. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1988;4:287–94. doi: 10.1089/aid.1988.4.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hammer SM, Gillis JM, Groopman JE, Rose RM. In vitro modification of human immunodeficiency virus infection by granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and gamma interferon. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:8734–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.22.8734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hartshorn KL, Neumeyer D, Vogt MW, Schooley RT, Hirsch MS. Activity of interferons alpha, beta and gamma against human immunodeficiency virus replication in vitro. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1987;3:125. doi: 10.1089/aid.1987.3.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Koyanagi Y, O'Brien WA, Zhao JQ, Golde DW, Gasson JC, Chen ISY. Cytokines alter production of HIV-1 from primary mononuclear phagocytes. Science. 1988;241:1673–5. doi: 10.1126/science.241.4873.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Poli G, Kinter AL, Justement JS, Bressler P, Kehrl JH, Fauci AS. Transforming growth factor β suppresses human immunodeficiency virus expression and replication in infected cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage. J Exp Med. 1991;173:589–97. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.3.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]