Abstract

We have recently demonstrated that IL-12 induced cellular inflammatory responses consisting mainly of accumulation of mononuclear leucocytes in the lungs of mice infected with Cryptococcus neoformans and protected mice against fulminant infection. We examined the involvement of endogenously synthesized IFN-γ in such a response by investigating the effects of a neutralizing monoclonal antibody against this cytokine. The latter treatment completely abrogated the positive effects of IL-12 on survival of infected mice and prevented IL-12-induced elimination of microbials from the lungs. Histopathological examination showed that accumulation of mononuclear leucocytes in the infected lungs caused by IL-12 was clearly inhibited by anti-IFN-γ MoAb. We also examined the local production of mononuclear cell-attracting chemokines such as monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES), macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α), MIP-1β and IFN-γ-inducible protein 10 (IP-10) in the lungs using a reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) method. We found that these chemokines were not synthesized in the infected lungs, while IL-12 treatment markedly induced their production. Interestingly, neutralizing anti-IFN-γ MoAb strongly suppressed IL-12-induced production of these chemokines. Similar results were obtained with MCP-1 and MIP-1α when their synthesis was measured at the protein level using respective ELISA kits. Our results indicate that IFN-γ plays a central role in the protective effects of IL-12 by inducing mononuclear leucocyte-attracting chemokines and cellular inflammatory responses.

Keywords: Cryptococcus neoformans, chemokines, interferon-gamma, IL-12, lungs

INTRODUCTION

IL-12 stimulates the production of IFN-γ by natural killer (NK) cells and γδ T cells [1, 2], an important component of the early host defence reaction against infection [3–6]. Furthermore, IL-12 is important in chronic infection, since it plays a central role in the generation of Th1 cells [7], a prerequisite for protecting the host against infectious agents through the production of IFN-γ [8]. The majority of the biological actions of this cytokine are thought to be mediated by IFN-γ [1, 9]. However, recent studies using IFN-γ gene-disrupted mice [10–12] raised the possibility of a direct action of IL-12 independent of IFN-γ.

Several chemoattractant proteins, designated as chemokines, have been recently identified. C-C chemokines, including monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES), macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α) and MIP-1β attract mainly monocytes, lymphocytes, eosinophils and basophils [13–23]. Furthermore, IFN-γ-inducible protein 10 (IP-10) selectively stimulates the migration of monocytes and lymphocytes into the site of inflammation [24], although it belongs to the C-X-C subfamily, which is involved in the trafficking of neutrophils [13, 14]. Thus, the accumulation of inflammatory mononuclear leucocytes at sites of infection is considered to be regulated by the local production and secretion of these chemokines [13, 14].

Cryptococcus neoformans, a ubiquitous fungal pathogen, causes a life-threatening infection in patients with impaired cell-mediated immunity, such as AIDS. Recently, we established a murine model of pulmonary and disseminated infection with a highly virulent clinical strain of C. neoformans, mimicking the physiological route and natural course of infection in humans [25]. In this model, accumulation of inflammatory leucocytes in the infected lungs is poor, and infection is associated with a high mortality. Interestingly, in these mice a marked cellular inflammatory response consisting mainly of mononuclear leucocytes was induced after treatment with IL-12, which closely correlated with protection of mice against fulminant infection. However, the precise mechanism underlying such protection is not well understood.

In the present study, to define the involvement of endogenously synthesized IFN-γ in IL-12-induced cellular inflammatory responses and protection against cryptococcal infection, we examined the effect of neutralizing anti-IFN-γ MoAb on these responses. Because recent investigations from other laboratories showed the critical roles of chemokines including MCP-1 and MIP-1α in host protection against C. neoformans [26–28], we further evaluated the local production of chemokines in the lungs of mice receiving this infection and also examined the effect of IL-12 and anti-IFN-γ MoAb.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Female (BALB/c × DBA/2)F1 mice were purchased from SLC Japan (Hamamatsu, Japan) and used at the age of 7–10 weeks. The experimental protocol was approved by the Ethics Review Committee for Animal Experimentation of our university. All mice were housed in a pathogen-free environment and received sterilized food and water at the Laboratory Animal Centre for Biomedical Science in University of the Ryukyus.

Cryptococcus neoformans

A serotype A-encapsulated strain of C. neoformans, YC-11, was obtained from a patient with pulmonary cryptococcosis. The yeast cells were cultured on potato dextrose agar plates for 3–4 days before use.

Intratracheal instillation of microorganisms

Mice were anaesthetized by an i.p. injection of 70 mg/kg of pentobarbital (Abbott Labs, North Chicago, IL) and restrained on a small board. Live C. neoformans (1 × 105) were inoculated in a volume of 50 μl per mouse by inserting a blunted 25 G needle into and parallel to the trachea.

IL-12

Recombinant murine IL-12 was kindly provided by Hoffmann-La Roche Inc. (Nutley, NJ). IL-12 was intraperitoneally administered at a dose of 0.1 μg per mouse daily for 7 days from the day of infection.

Histopathological examination

Mice were killed 14 days after instillation of C. neoformans. The lung specimens were fixed in 4% buffer formalin, dehydrated and embedded in paraffin. Sections were cut and stained with haematoxylin and eosin using a standard staining procedure, and examined under a light microscope.

Preparation of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

Mice were killed 7 and 14 days after infection and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was collected as described below. Briefly, after bleeding under anaesthesia with ether, the chest was opened and the trachea was cannulated with the outer sheath of a 22 G i.v. catheter/needle unit (Becton Dickinson Vascular Access, Sandy, UT), and the lung was lavaged once with 1 ml of chilled PBS. The obtained samples were stored at −70°C until measurement of cytokines. Using this method, 300–500 μl of lavage fluid were usually collected from each mouse.

Antibodies

Anti-interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) MoAb was purified by a protein A column kit (Ampure PA Kit; Amersham Japan, Tokyo, Japan) from ascitic fluid obtained from nude mice injected intraperitoneally with a hybridoma (clone R4-6A2, purchased from ATCC, Rockville, MD). To block endogenously synthesized IFN-γ, mice were injected intraperitoneally with this MoAb at 200 μg 1 day before, on the day of and once a week after infection. Rat IgG (Wako Chemical Co., Tokyo, Japan) was used as a control antibody.

Extraction of RNA and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted from the lungs of mice 7 and 14 days after instillation of C. neoformans by the acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform method and subsequently reverse transcription was carried out, as described in our recent study [29]. The obtained cDNA was then amplified in an automatic DNA thermal cycler (Perkin Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, CT) using specific primers 5′-TCC ATG CAG GTC CCT GTC ATG CTT-3′ (sense) and 5′-CTA GTT CAC TGT CAC ACT GGT C-3′ (anti-sense) for MCP-1, 5′-TCT TCT CTG GGT TGG CAC ACA C-3′ (sense) and 5′-CCT CAC CAT CAT CCT CAC TGC A-3′ (anti-sense) for RANTES, 5′-GGA ATT CTG CAG TCC CAG CTC TGT GCA A-3′ (sense) and 5′-GGA ATT CCA CAG TCA TAT CCA CAA TAG-3′ (anti-sense) for MIP-1β, 5′-CCC GGG AAT TCA TAC CAT GAA CCC AAG TGC TGC C-3′ (sense) and 5′-GTC ACG ATG AAT TCC TTA AGG AGC CCT TTT AGA CCT-3′ (anti-sense) for IP-10 [30], 5′-CAC CCT CTG TCA CCT GCT CAA CAT C-3′ (sense) and 5′-GGT TCC TCG CTG CCT CCA AGA CTC T-3′ (anti-sense) for MIP-1α [31], 5′-GTT GGA TAC AGG CCA AGA CTT TGT TG-3′ (sense) and 5′-GAT TCA ACT TGC GCT CAT CTT AGG C-3′ (anti-sense) for hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase (HPRT) [29]. We added 1.0 μl of the sample cDNA solution to 49 μl of the reaction mixture, which contained the following concentrations: 10 mm Tris–HCl pH = 8.3, 50 mm KCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 10 μg/ml gelatin, dNTP (each at a concentration of 200 μm), 1.0 μm sense and anti-sense primer, 1.25 U of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Perkin Elmer Cetus). The mixture was incubated for 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 62°C and 1 min 45 s at 72°C for MCP-1, RANTES, MIP-1β and IP-10, and for 1 min at 94°C, for 1 min at 54°C and for 1 min 30 s at 72°C for HPRT. The number of cycles was determined for samples not reaching the amplification plateau (30 cycles for MCP-1, MIP-1β, IP-10 and HPRT, and 27 cycles for RANTES). For MIP-1α, the sequence of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification was one cycle of denaturation at 95°C for 2 min, followed by annealing at 56°C for 30 s and extension at 72°C for 1 min. This cycle was followed by 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 56°C and 1 min for 72°C repeated 38 times. The PCR products were electrophoresed on 2% agarose gels, stained with 0.5 μg/ml ethidium bromide and observed with a UV transilluminator.

Measurement of cytokine concentrations

The concentration of chemokines in BALF was measured by ELISA kits purchased from R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN). The sensitivity of these assays was 9 and 1.5 pg/ml for MCP and MIP-1α, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± s.d. The unpaired Student's t-test was used to compare differences between groups. Survival data were analysed using the generalized Wilcoxon test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

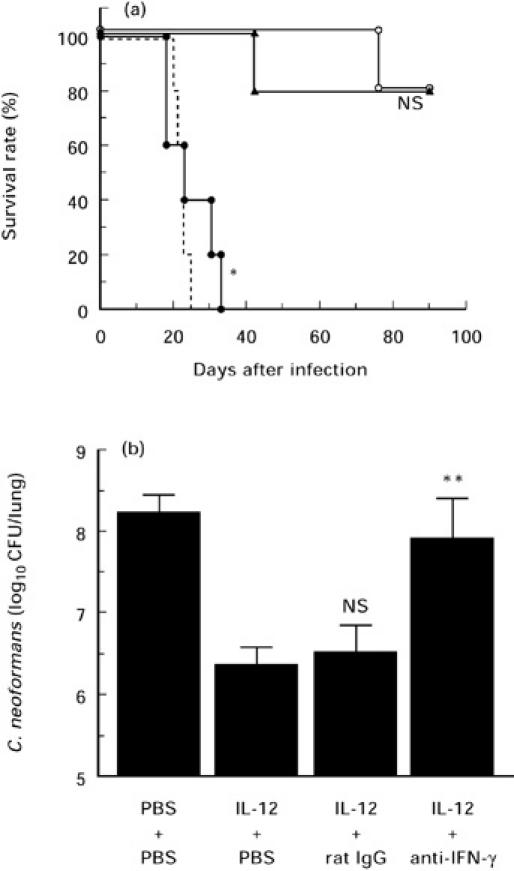

IL-12-induced protection against cryptococcal infection is mediated by IFN-γ

Recently, we demonstrated that IL-12 protected mice against fulminant infection with C. neoformans [25, 29]. In these studies, IFN-γ mRNA was not expressed in the lungs at any time interval after intratracheal infection with C. neoformans, while treatment with IL-12 induced the synthesis of this cytokine as early as day 1 post-infection. Although many investigators have indicated that the biological activities of IL-12 are mediated by endogenously synthesized IFN-γ [1, 9], others have provided evidence in support of IFN-γ-independent action for IL-12 [10–12]. To define the involvement of IFN-γ in our system, we first examined the effect of neutralizing anti-IFN-γ MoAb on the IL-12-induced protection against pulmonary infection with C. neoformans. As shown in Fig. 1a, all infected and PBS-treated mice died within 4 weeks of infection, while administration of IL-12 saved 80% of these mice. Treatment with anti-IFN-γ MoAb almost completely abrogated the effect of IL-12 on the survival of infected mice, while control rat IgG did not show such effect. In addition, IL-12 treatment significantly potentiated the clearance of live yeast cells from the infected lungs, and neutralization of endogenously synthesized IFN-γ by specific MoAb almost completely abrogated this effect of IL-12, while control rat IgG did not show any influence (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Effect of neutralizing anti-IFN-γ MoAb on the protective effect of IL-12 treatment. (a) Mice received daily i.p. injections of PBS (no symbol, broken line; n = 5) or 0.1 μg of IL-12 (○; n = 5) for 7 days from the day of intratracheal instillation of 1 × 105 cells of Cryptococcus neoformans. IL-12-treated mice were injected intraperitoneally with 200 μg of control rat IgG (▴; n = 5) or 200 μg of anti-IFN-γ MoAb (•; n = 5) 1 day prior to, at the day of and once a week after infection. The number of live mice was counted. NS, Not significant; *P < 0.01 compared with infected/IL-12-treated and antibody-untreated mice by the generalized Wilcoxon test. (b) Number of live microorganisms in lungs examined 3 weeks after infection in the same experiment. Bars represent the mean ± s.d. of five mice. The experiments were repeated three times with similar results. NS, Not significant; **P < 0.05 compared with infected/IL-12-treated and antibody-untreated mice by Student's t-test.

Effect of anti-IFN-γ MoAb on IL-12-induced local inflammatory responses

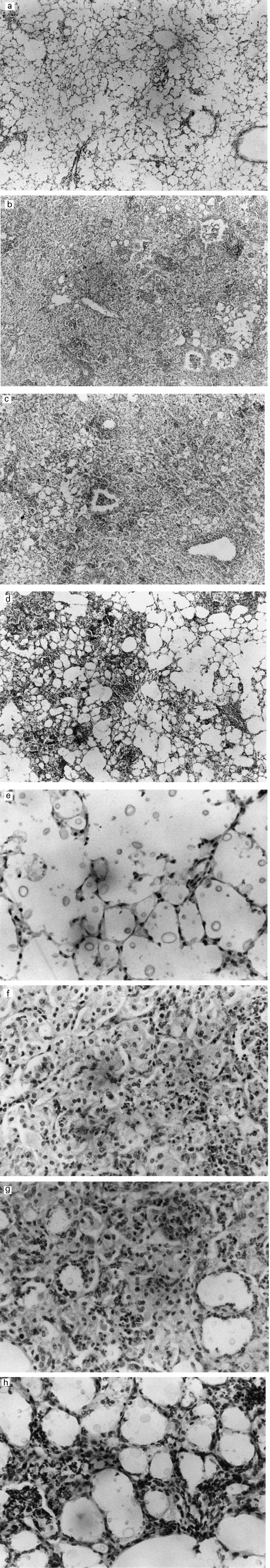

We recently demonstrated the presence of a large number of multiplying C. neoformans in the alveolar spaces of infected animals, with poor accumulation of inflammatory leucocytes [25]. In addition, it was also shown that treatment with IL-12 caused a marked increase in the number of infiltrating leucocytes consisting mainly of macrophages and lymphocytes, which were diffusely present throughout the infected lungs. To elucidate the role of endogenously synthesized IFN-γ in IL-12-induced trafficking of inflammatory leucocytes into the lungs, we examined the effect of anti-IFN-γ MoAb. As shown in Fig. 2(a, e), a poor inflammatory response was repeatedly observed throughout the lungs of mice infected with C. neoformans, while a massive infiltration of mononuclear inflammatory leucocytes was induced after treatment with IL-12 (Fig. 2b,f). Neutralization of endogenously synthesized IFN-γ by administration of a specific MoAb clearly suppressed these responses (Fig. 2d,h), while control rat IgG did not show such effect (Fig. 2c,g).

Fig. 2.

(See also pp 117–119) Effect of neutralizing anti-IFN-γ MoAb on the inflammatory responses induced by IL-12. Mice received daily i.p. injections of PBS (a,e) or 0.1 μg of IL-12 (b,f) for 7 days from the day of intratracheal infection with 1 × 105 cells of Cryptococcus neoformans. IL-12-treated mice were injected intraperitoneally with 200 μg of control rat IgG (c,g) or 200 μg of anti-IFN-γ MoAb (d,h) using the same schedule described in Fig. 1. Paraffin sections of the lung were prepared from mice killed 14 days after instillation of the microorganisms, stained with haematoxylin and eosin, and examined at × 40 (a,b,c,d) and × 200 (e,f,g,h) under a light microscope. Each photomicrograph represents a representative mouse (three per group). The experiments were repeated two times with similar results.

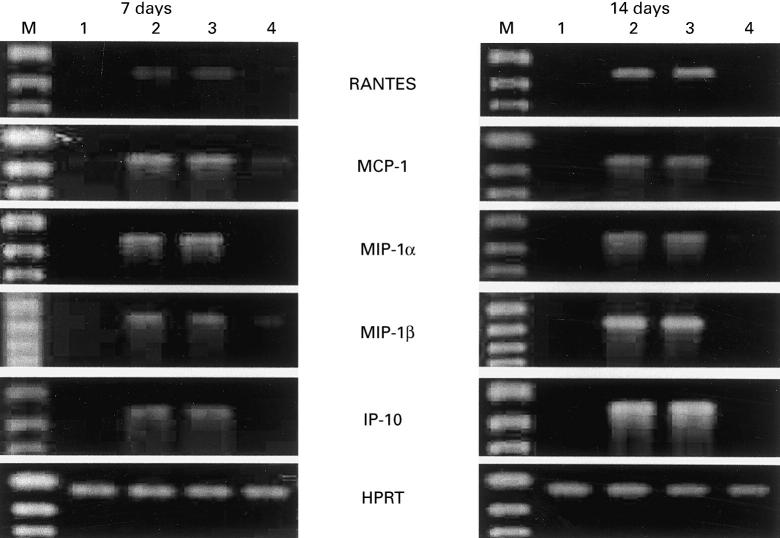

IFN-γ-dependent induction of chemokine responses by IL-12

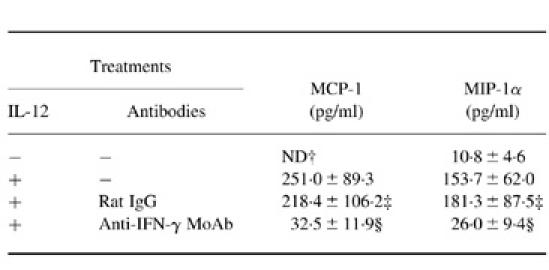

Because induction of cellular inflammatory responses has been shown to be mediated by a variety of chemokines synthesized at the site of the primary infection, we measured the expression of MCP-1, RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β and IP-10 mRNAs, which have been reported to enhance the infiltration of mononuclear leucocytes into the inflammatory sites, and examined the effect of IL-12. As shown in Fig. 3, mRNAs of these chemokines could not be detected in the lungs on days 7 and 14 of infection, while IL-12 treatment clearly induced their synthesis at both time intervals. These observations were quite compatible with the histopathological findings. In the next experiment, we examined the effect of neutralizing anti-IFN-γ MoAb on IL-12-induced expression of MCP-1, RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β and IP-10 mRNAs. Treatment with such MoAb strongly inhibited the synthesis of these chemokines (Fig. 3). Furthermore, these findings were confirmed by measuring BALF levels of MCP-1 and MIP-1α using the respective ELISA kits. As shown in Table 1, anti-IFN-γ MoAb significantly suppressed IL-12-induced production of these chemokines in the lungs of mice infected with C. neoformans, while control rat IgG did not show such effect.

Fig. 3.

Effect of neutralizing anti-IFN-γ MoAb on IL-12-induced expression of chemokine mRNA in lungs. Mice received daily i.p. injections of PBS (n = 3) or 0.1 μg of IL-12 for 7 days from the day of intratracheal infection with 1 × 105 cells of Cryptococcus neoformans. IL-12-treated mice were injected intraperitoneally with 200 μg of control rat IgG (n = 3) or 200 μg of anti-IFN-γ MoAb (n = 3) using the schedule described in Fig. 1. On days 7 and 14 of infection, mice were killed and total RNA was extracted from the lungs. Subsequently, reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was carried out for the indicated chemokines. Hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase (HPRT) was used as an internal control. RNA samples were obtained separately from three mice in each group, and the results are representative of three sets of separate samples. 1, Infected/PBS-treated; 2, infected/IL-12-treated; 3, infected/IL-12 and rat IgG-treated; 4, infected/IL-12 and anti-IFN-γ MoAb-treated; M, DNA size marker.

Table 1.

Effect of anti-IFN-γ MoAb on IL-12-induced chemokine production*

* Mice received daily i.p. injections of PBS or 0.1 μg of IL-12 for 7 days from the day of intratracheal instillation of 1 × 105 cells of Cryptococcus neoformans. These mice were injected intraperitoneally with PBS, 200 μg of control rat IgG or 200 μg of anti-IFN-γ MoAb 1 day prior to, at the day of and once a week after infection. On day 14 of infection, mice were killed and bronchoalveolar lavage fluids (BALF) were obtained. Content of MCP-1 and MIP-1α in the BALF was measured by ELISA. Data indicate the mean ± s.d. of four mice. The experiment was repeated twice with similar results.

† ND, Not detected.

‡ Not significant compared with IL-12-treated and antibody-untreated mice by Student's t-test.

§ P < 0.01 compared with IL-12-treated and antibody-untreated mice by Student's t-test.

DISCUSSION

The major findings of the present study were: (i) IL-12-induced protection of mice against infection with C. neoformans was mediated by IFN-γ; the protective effect of IL-12 was completely abrogated by neutralization of endogenously synthesized IFN-γ by a specific MoAb; (ii) IL-12 enhanced the accumulation of mononuclear leucocytes in the lungs of infected mice, an effect inhibited by treatment with anti-IFN-γ MoAb; (iii) a good correlation between histopathological findings and local production of mononuclear leucocyte-chemoattractants such as MCP-1, RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β and IP-10; and (iv) inhibition of IL-12-induced production of these chemokines by administration of anti-IFN-γ MoAb.

Most biological activities of IL-12 are mediated by endogenously synthesized IFN-γ [1, 9], although several other studies have also shown IFN-γ-independent effects for IL-12 [10–12]. Using IFN-γ gene-disrupted mice, Taylor et al. [10] have recently demonstrated the presence of an IFN-γ-independent mechanism in IL-12-induced antimicrobial effects against Leishmania donovani, which was mediated by tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). Similarly, Zilocchi et al. [11] reported IFN-γ-independent rejection of IL-12-transduced carcinoma cells, an effect that was mediated by CD4+ T cells and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Wang et al. [12] also reported IFN-γ-independent actions of IL-12 on IL-4 and IL-10 synthesis in IFN-γ gene-disrupted mice infected with L. major [12]. In the present study, however, we indicated that IFN-γ was essential for the protective activity of IL-12 against infection with C. neoformans. Previous studies using neutralizing anti-IFN-γ MoAb demonstrated that this cytokine was a key molecule to express host resistance against cryptococcal infection [31, 32], and that its protective activity was mediated by inducing macrophage production of fungicidal mediators including nitric oxide [34, 35]. Thus, our results indicate that IL-12 protected mice against fulminant pulmonary cryptococcosis by inducing IFN-γ-dependent activation of fungicidal mechanisms, although we could not completely exclude an alternative possibility that endogenously synthesized IFN-γ during infection may collaborate with the IFN-γ-independent effect of exogenously administered IL-12 in protecting mice against this infection.

In a previous study by Huffnagle et al. [26], CD4+ T cells as well as macrophages were predominantly recruited into lungs infected with C. neoformans, and the kinetics of such recruitment correlated well with the production of MCP-1. Furthermore, these workers indicated that the recruitment of these cells was strongly suppressed by neutralizing anti-MCP-1 antibody. In another study [27], the same authors also demonstrated the involvement of MIP-1α in the recruitment of macrophages, but not of CD4+ T cells, into the lungs of mice infected with C. neoformans. In an in vitro study, Levitz and co-workers demonstrated that C. neoformans induced the production of MCP-1 by human peripheral blood monocytes [36]. Doyle & Murphy recently showed the induction of MIP-1α synthesis by injection of cryptococcal antigen, which was involved in the accumulation of lymphocytes and neutrophils at the inflammatory site, and the critical role of this chemokine in host resistance to cryptococcal infection [28]. By contrast, in our study a large number of fungal yeast cells multiplied in the alveolar spaces, associated with a poor presence of inflammatory leucocytes, in the lungs infected with C. neoformans. Because the fungal pathogen used in this study did not or marginally induced the local production of chemokines such as MCP-1, RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β and IP-10 in the lungs, the inconsistent results between our and other laboratories may be due to the strain difference of C. neoformans in the ability to induce the chemokine responses.

On the other hand, administration of IL-12 induced a marked infiltration of inflammatory cells consisting mainly of macrophages and lymphocytes. This observation was in agreement with the results showing the local production of mononuclear leucocyte-attracting chemokines in the lungs by treatment with IL-12. Furthermore, the reduced production of these chemokines by neutralizing anti-IFN-γ MoAb correlated with the attenuated accumulation of mononuclear leucocytes in lungs infected with C. neoformans. These results suggest that the cellular inflammatory responses caused by IL-12 in the lungs of mice infected with C. neoformans may be mediated by mononuclear leucocyte-attracting chemokines produced upon stimulation with endogenously synthesized IFN-γ. Interestingly, Pearlman et al. [30] recently demonstrated IL-12-induced production of a spectrum of chemokines similar to those of the present study and recruitment of inflammatory cells consisting of mononuclear leucocytes and eosinophils, although they did not confirm the involvement of IFN-γ as a mediator in these responses.

In a series of recent studies from our laboratory [25, 29], we have demonstrated that the expression of IFN-γ mRNA was induced in lungs infected with C. neoformans as early as the first day after administration of IL-12. On the other hand, the expression of RANTES, MCP-1, MIP-1α and MIP-1β mRNA appeared on day 3, although the kinetics of the expression of IP-10 mRNA was similar to that of IFN-γ (unpublished data). Thus, IFN-γ production was likely to have preceded the generation of chemokines in the lungs of mice infected with C. neoformans after treatment with IL-12. Based on these findings, we postulate that endogenously synthesized IFN-γ may be involved in the chemokine production caused by IL-12. In previous studies, IFN-γ was demonstrated to potentiate the production of RANTES, MCP-1, MIP-1α, MIP-1β and IP-10 by macrophages, endothelial cells, fibroblasts and keratinocytes [37–42]. In fact, intradermal injection of IFN-γ induces a local production of IP-10 and elicits the infiltration of mononuclear inflammatory cells [43–45]. Combined together, these findings indicate that IFN-γ plays a central role in the protective effects of IL-12, not only by augmenting macrophage cryptococcocidal activity through induction of reactive nitrogen intermediates, as previously reported by our laboratory and other investigators [34, 35], but also by inducing a variety of chemokines and cellular inflammatory responses consisting mostly of mononuclear leucocytes.

Host resistance to microbial pathogens includes accumulation of appropriate inflammatory cells at the site of infection at an appropriate time. In cryptococcal infection, mononuclear leucocytes such as macrophages and lymphocytes, rather than neutrophils, are important [46]. Although chemokines are directly and selectively associated with these cellular inflammatory responses, many other proinflammatory cytokines including IL-1, TNF-α, IL-6, IFN-γ and IL-12 are also involved in the formation of inflammatory lesions. Therefore, for a better understanding of the host defence mechanism, further studies are necessary to examine the relationship between inflammatory responses mediated by proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. In the present study, we defined IFN-γ as a cytokine that connects these two inflammatory processes following exogenous administration of IL-12 in mice infected with C. neoformans.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr F. G. Issa (Department of Medicine, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia) for editing the manuscript. This work was supported in part by the Japan Health Science Foundation and a Grant-in-Aid for Science Research (09670292) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sport and Culture and by grants from the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12: a proinflammatory cytokine with immunoregulatory functions that bridge innate resistance and antigen-specific adaptive immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:251–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.001343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skeen MJ, Ziegler HK. Activation of γδ T cells for production of IFN-γ is mediated by bacteria via macrophage-derived cytokines IL-1 and IL-12. J Immunol. 1995;154:5832–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunn PL, North RJ. Early gamma interferon production by natural killer cells is important in defense against murine listeriosis. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2892–900. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.2892-2900.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laskay T, Rolinghoff M, Solbach W. Natural killer cells participate in the early defense against Leishmania major infection in mice. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:2237–41. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosat JP, MacDonald HR, Louis JA. A role for γδ+ T cells during experimental infection of mice with Leishmania major. J Immunol. 1993;150:550–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scharton TM, Scott P. Natural killer cells are a source of interferon gamma that drives differentiation of CD4+ T cell subsets and induces early resistance to Leishmania major in mice. J Exp Med. 1993;178:567–77. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.2.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsieh CS, Macatonia SE, Tripp CS, O'Garra A, Murphy KA. Development of Th1, CD4+ T cells through IL-12 produced by Listeria-induced macrophages. Science. 1993;260:547–9. doi: 10.1126/science.8097338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mosmann TR, Sad S. The expanding universe of T-cell subsets: Th1, Th2 and more. Immunol Today. 1996;17:138–46. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)80606-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12: a cytokine produced by antigen-presenting cells with immunoregulatory functions in the generation of T-helper cells type 1 and cytotoxic lymphocytes. Blood. 1994;84:4008–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor AP, Murray HW. Intracellular antimicrobial activity in the absence of interferon-γ: effect of interleukin-12 in experimental visceral leishmaniasis in interferon-γ gene-disrupted mice. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1231–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.7.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zilocchi C, Stoppacciaro A, Chiodoni C, Parenza M, Terrazzini N, Colombo MP. Interferon γ-independent rejection of interleukin 12-transduced carcinoma cells requires CD4+ T cells and granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Exp Med. 1998;188:133–43. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.1.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang ZE, Zheng S, Corry DB, Dalton DK, Seder RA, Reiner SL, Locksley RM. Interferon γ-independent effects of interleukin 12 administered during acute or established infection due to Leishmania major. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12932–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baggiolini M, Dewald B, Moser B. Interleukin-8 and related chemotactic cytokines—CXC and CC chemokines. Adv Immunol. 1994;55:97–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oppenheim JJ, Zachariae COC, Mukaida N, Matsushima K. Properties of the novel proinflammatory supergene ‘intercrine’ cytokine family. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:617–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.003153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshimura T, Robinson EA, Tanaka S, Appella E, Kuratsu JI, Leonard EJ. Purification and amino acid analysis of two human glioma-derived monocyte chemoattractants. J Exp Med. 1989;169:1449–59. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.4.1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsushima K, Larsen CG, DuBois GC, Oppenheim JJ. Purification and characterization of a novel monocyte chemotactic and activating factor produced by a human myelocytic cell line. J Exp Med. 1989;169:1485–90. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.4.1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carr MW, Roth SJ, Luther E, Rose SS, Springer TA. Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 acts as a T-lymphocyte chemoattractant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3652–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schall TJ, Bacon K, Toy KJ, Goeddel DV. Selective attraction of monocytes and T lymphocyte of the memory phenotype by the cytokine RANTES. Nature. 1990;347:669–71. doi: 10.1038/347669a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kameyoshi Y, Dorschner A, Mallet AI, Christophers E, Schroder JM. Cytokine RANTES released by thrombin-stimulated platelets is a potent attractant for human eosinophils. J Exp Med. 1992;176:587–92. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.2.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rot A, Krieger M, Brunner T, Bischoff SC, Schall TJ, Dahinden CA. RANTES and macrophage inflammatory protein 1α induce the migration and activation of normal human eosinophil granulocytes. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1489–95. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.6.1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bischoff SC, Krieger M, Brunner T, Rot A, von Tscharner V, Baggiolini M, Dahinden CA. RANTES and related chemokines activate human basophilgranulocytes through different G protein-coupled receptors. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:761–7. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sherry B, Tekamp-Olson P, Gallegos C, Bauer D, Davatelis G, Masiarz F, Coit D, Cerami A. Resolution of the two components of macrophage inflammatory protein 1 and cloning and characterization of one of those components, macrophage inflammatory protein 1β. J Exp Med. 1998;168:2251–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.6.2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schall TJ, Bacon K, Camp RDR, Kaspari JW, Goeddel DV. Human macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α) and MIP-1β chemokines attract distinct populations of lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1821–5. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taub DD, Lloyd AR, Conlon K, et al. Recombinant human interferon-γ inducible protein 10 is chemoattractant for human monocytes and T lymphocytes and promotes T cell adhesion to endothelial cells. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1809–14. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawakami K, Tohyama M, Xie Q, Saito A. Interleukin-12 protects mice against pulmonary and disseminated infection caused by Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;104:208–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.14723.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huffnagle GB, Strieter RM, Standiford TJ, McDonald RA, Burdick MD, Kunkel SL, Toews GB. The role of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) in the recruitment of monocytes and CD4+ T cells during a pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans infection. J Immunol. 1995;155:4790–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huffnagle GB, Strieter RM, McNeil LK, McDonald RA, Burdick MD, Kunkel SL, Toews GB. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α) is required for the efferent phase of pulmonary cell-mediated immunity to a Cryptococcus neoformans infection. J Immunol. 1997;159:318–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doyle HA, Murphy JW. MIP-1 alpha contributes to the anticryptococcal delayed hypersensitivity reaction and protection against Cryptococcus neoformans. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;61:147–55. doi: 10.1002/jlb.61.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawakami K, Tohyama M, Xie Q, Saito A. Expression of cytokines and inducible nitric oxide synthase mRNA in the lungs of mice infected with Cryptococcus neoformans: effects of interleukin-12. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1307–12. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1307-1312.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pearlman E, Lass JHD, Bardenstein S, Diaconu E, Hazlett FE, Jr, Albright J, Higgins AW, Kazura JW. IL-12 exacerbates helminth-mediated corneal pathology by augmenting inflammatory cell recruitment and chemokine expression. J Immunol. 1997;158:827–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tessier PA, Naccache PH, Clark-Lewis I, Cladue RP, Neote KS, McColl SR. Chemokine networks in vivo. Involvement of C-X-C and C-C chemokines in neutrophil extravasation in vivo in response to TNF-α. J Immunol. 1997;159:3595–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salkowski CA, Balish E. A monoclonal antibody to gamma interferon blocks augmentation of natural killer cell activity induced during systemic cryptococcosis. Infect Immun. 1991;59:486–93. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.2.486-493.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kawakami K, Tohyama M, Teruya K, Kudeken N, Xie Q, Saito A. Contribution of interferon-γ in protecting mice during pulmonary and disseminated infection with Cryptococcus neoformans. FEMS Immunol Microbiol. 1996;13:123–30. doi: 10.1016/0928-8244(95)00093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Granger DL, Hibbs JB, Jr, Perfect JR, Durack T. Specific amino acid (l-arginine) requirement for the microbiostatic activity of murine macrophages. J Clin Invest. 1988;81:1129–36. doi: 10.1172/JCI113427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tohyama M, Kawakami K, Futenma M, Saito A. Enhancing effect of oxygen radical scavengers on murine macrophage anticryptococcal activity through production of nitric oxide. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;103:436–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1996.tb08299.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levitz SM, North EA, Jiang Y, Nong SH, Kornfeld H, Harrison TS. Variables affecting production of monocyte chemotactic factor 1 from human leukocytes stimulated with Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 1997;65:903–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.3.903-908.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marfaing-Koka A, Devergne O, Gorgone G, Portier A, Schall TJ, Galamaud P, Emilie D. Regulation of the production of the RANTES chemokine by endothelial cells. Synergistic induction by IFN-γ and TNF-α and inhibition by IL-4 and IL-13. J Immunol. 1995;154:1870–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Satriano JA, Hora K, Shan Z, Stanley ER, Mori T, Schlondorff D. Regulation of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and macrophage colony-stimulating factor-1 by IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor-α, IgG aggregates, and cAMP in mouse mesangial cells. J Immunol. 1993;150:1971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou ZHL, Chaturvedi P, Han YL, et al. IFN-γ induction of the human monocyte chemoattractant protein (hMCP)-1 gene in astrocytoma cells: functional interaction between an IFN-γ-activated site and a GC-rich element. J Immunol. 1998;160:3908–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martin CA, Dorf ME. Differential regulation of interleukin-6, macrophage inflammatory protein-1, and JE/MCP-1 cytokine expression in macrophage cell lines. Cell Immunol. 1991;135:245–58. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(91)90269-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luster AD, Unkeless JC, Ravetch JV. γ-Interferon transcriptionally regulates an early-response gene containing homology to platelet proteins. Nature. 1985;315:672–6. doi: 10.1038/315672a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luster AD, Ravetch JV. Biochemical characterization of a γ interferon-inducible cytokine (IP-10) J Exp Med. 1987;166:1084–97. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.4.1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nathan CN, Kaplan G, Levis WR, et al. Local and systemic effects of low doses of recombinant interferon-γ after intradermal injection in patients with lepromatous leprosy. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:6–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198607033150102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaplan G, Luster AD, Hancock G, Cohn ZA. The expression of a γ interferon-induced protein (IP-10) in delayed immune responses in human skin. J Exp Med. 1987;166:1098–108. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.4.1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Narumi S, Wyner LM, Sroler MH, Tannenbaum CS, Hamilton TA. Tissue specific expression of murine IP-10 mRNA following systemic treatment with interferon-γ. J Leukocyte Biol. 1992;52:27–33. doi: 10.1002/jlb.52.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murphy JW. Cryptococcosis. In: Cox RA, editor. Immunology of fungal diseases. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1989. pp. 93–138. [Google Scholar]