Abstract

Human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV16) infection has been linked to the development of cervical and anal dysplasia and cancer. One hallmark of persistent infection is the synthesis of the viral E7 protein in cervical epithelial cells. The expression of E7 in dysplastic and transformed cells and its recognition by the immune system as a foreign antigen make it an ideal target for immunotherapy. Utilizing the E7-expressing murine tumour cell line, TC-1, as a model of cervical carcinoma, an immunotherapy based on the administration of an adjuvant-free fusion protein comprising Mycobacterium bovis BCG heat shock protein (hsp)65 linked to HPV16 E7 (hspE7) has been developed. The data show that prophylactic immunization with hspE7 protects mice against challenge with TC-1 cells and that these tumour-free animals are also protected against re-challenge with TC-1 cells. In addition, therapeutic immunization with hspE7 induces regression of palpable tumours, confers protection against tumour re-challenge and is associated with long-term survival (> 253 days). In vitro analyses indicated that immunization with hspE7 leads to the induction of a Th1-like cell-mediated immune response based on the pattern of secreted cytokines and the presence of cytolytic activity following antigenic recall. In vivo studies using mice with targeted mutations in CD8 or MHC class II or depleted of CD8 or CD4 lymphocyte subsets demonstrate that tumour regression following therapeutic hspE7 immunization is CD8-dependent and CD4-independent. These studies extend previous observations on the induction of cytotoxic T lymphocytes by hsp fusion proteins and are consistent with the clinical application of hspE7 as an immunotherapy for human cervical and anal dysplasia and cancer.

Keywords: immunotherapy, HPV, heat shock protein, E7 fusion

Introduction

Among the approximately 100 different genotypes of human papillomavirus (HPV), it is the presence of HPV16 that is most frequently associated with the appearance of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) [1] as well as anal [2] and cervical cancer [3]. Interestingly, the incidence of HPV infection with high-risk types such as HPV16 far exceeds the number of individuals who present with high-grade CIN, and fewer still progress to invasive cancer [4,5]. It is believed that the induction of cell-mediated immunity by the host contributes to limiting the progression from infection and low-grade CIN to high-grade CIN and cancer [6–8]. Because E7 (an early viral protein of HPV16) is continuously expressed by the target epithelial cell upon viral integration and cellular transformation [9], is highly conserved in amino acid sequence among HPV genotypes [10] and is antigenic in man [11–13], immunotherapeutic strategies to enhance the endogenous response to this tumour-specific antigen for the treatment of HPV-associated disease are being developed [14,15].

The unusual immunogenicity of heat shock proteins (hsp), originally observed in the context of microbial infection, has prompted researchers to exploit these properties in the development of infectious disease vaccines and cancer immunotherapies (reviewed in [16]). It has been previously demonstrated that adjuvant-free immunization of mice with a recombinant fusion protein consisting of Mycobacterium bovis BCG hsp65 and portions of the nucleoprotein (NP) antigen of influenza virus elicits MHC class I-restricted, NP-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) [17]. Based on these and other results demonstrating induction of CD8+ CTL by mycobacterial hsp fusions [18–21], the potential utility of a recombinant fusion protein comprising M. bovis BCG hsp65 and HPV16 E7 (hspE7) has been evaluated for the immunotherapy of an E7-expressing murine tumour cell line, TC-1. TC-1 is tumourigenic in syngeneic, immunocompetent mice and has been characterized as a model for human cervical carcinoma [22,23].

The present study demonstrates that adjuvant-free immunization of C57Bl/6 mice with hspE7 protects animals against challenge with TC-1 cells and also protects against re-challenge with higher doses of TC-1 cells. Similarly, immunization of tumour-bearing mice with hspE7 leads to tumour regression, protection from re-challenge and long-term survival. Using mice genetically deficient in CD8 or MHC class II Aβ chain, or mice depleted of CD4+ or CD8+ T lymphocyte subsets in vivo by antibody administration, tumour regression following hspE7 immunization appears to be dependent on CD8+ T cells, but independent of CD4+ T cells. This is the first study to demonstrate that therapeutic immunization with an hsp fusion protein induces tumour regression and represents the first example of cancer immunotherapy based on the use of an hsp65 fusion protein.

Materials and methods

Plasmid construction

pET65

The M. bovis BCG hsp65 gene was polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplified from pRIB1300 [24] using the following primers. The forward primer (W046: 5′ TTC GCC ATG GCC AAG ACA ATT GCG 3′) contains an ATG start codon at an NcoI site. The reverse primer (W078: 5′ TTC TCG GCT AGC TCA GAA ATC CAT GCC 3′) contains an NheI site downstream of a TGA stop codon. The PCR product was digested with NcoI and NheI, purified and ligated to pET28a (Novagen, Madison, WI) which had been cut with NcoI and NheI. pET65 encodes the M. bovis BCG hsp65 protein, abbreviated hsp65.

pET65C

The M. bovis BCG hsp65 gene was PCR amplified from pRIB1300 using the same forward primer (W046) as for pET65. The reverse primer (W076: 5′ CGC TCG GAC GCT AGC TCA CAT ATG GAA ATC CAT GCC 3′) contains an NdeI site upstream and an NheI site downstream of a TGA stop codon. The PCR product was digested with NcoI and NheI, purified and ligated to pET28a which had been cut with NcoI and NheI.

pET65H

The M. bovis BCG hsp65 gene was PCR amplified from pRIB1300 using the following primers. The forward primer (W093: 5′ AAT CAC TTC CAT ATG GCC AAG ACA ATT 3′) contains an ATG start codon at an NdeI site. The reverse primer (W094: 5′ CGC TCG GAC GAA TTC TCA GCT AGC GAA ATC CAT GCC 3′) contains an NheI site upstream and an EcoRI site downstream of a TGA stop codon. The PCR product was digested with NdeI and EcoRI, purified and ligated to pET28a which had been cut with NdeI and EcoRI.

pET65H/E7

The HPV16 E7 gene was PCR amplified from HPV16 genomic DNA (pSK/HPV16; ATCC, Rockville, MD) using the following primers. The forward primer (W133: 5′ AAC CCA GCT GCT AGC ATG CAT GGA GAT 3′) contains an NheI site upstream of an ATG start codon. The reverse primer (W134: 5′ AGC CAT GAA TTC TTA TGG TTT CTG 3′) contains an EcoRI site downstream of a TAA stop codon. The PCR product was digested with NheI and EcoRI, purified and ligated to pET65H which had been cut with NheI and EcoRI. pET65H/E7 encodes an N-terminal histidine-tagged fusion protein consisting of hsp65 linked at the C-terminus to HPV16 E7, abbreviated (h)hspE7.

pET65C/E7-1N

The HPV16 E7 gene was PCR amplified from HPV16 genomic DNA (pSK/HPV16) using the following primers. The forward primer (W151: 5′ CCA GCT GTA CAT ATG CAT GGA GAT 3′) contains an ATG start codon at an NdeI site. The reverse primer (W134: 5′ AGC CAT GAA TTC TTA TGG TTT CTG 3′) contains an EcoRI site downstream of a TAA stop codon. The PCR product was digested with NdeI and EcoRI, purified and ligated to pET65C which had been cut with NdeI and EcoRI. pET65C/E7-1N encodes a fusion protein consisting of hsp65 linked at the C-terminus to HPV16 E7, abbreviated hspE7.

pET/H/E7

The HPV16 E7 gene was PCR amplified from HPV16 genomic DNA (pSK/HPV16) using the following primers. The forward primer (W133: 5′ AAC CCA GCT GCT AGC ATG CAT GGA GAT 3′) contains an NheI site upstream of an ATG start codon. The reverse primer (W134: 5′ AGC CAT GAA TTC TTA TGG TTT CTG 3′) contains an EcoRI site downstream of a TAA stop codon. The PCR product was digested with NheI and EcoRI, purified and ligated to pET28a which had been cut with NheI and EcoRI. pET/H/E7 encodes the HPV16 E7 protein containing an N-terminal histidine tag, abbreviated (h)E7.

All bacterial expression plasmids were sequenced to confirm the gene (or fusion gene) insert, promoter and terminator regions.

Protein purification

The Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3) (Novagen) was used as host for all recombinant protein production, with the exception of pET65, which was transformed into BL21(DE3) pLysS (Novagen). BL21(DE3) pLysS cells harbouring pET65 were grown in 2xYT containing 30 μg/ml kanamycin and 34 μg/ml chloramphenicol, while all other transformants were grown in 2xYT containing 30 μg/ml kanamycin. All bacterial cultures were grown in 2 L shaker flasks at 250 rev/min to OD600 = 0·5 and then induced with 0·5 mm isopropyl‐β‐d‐thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 3 h at 37°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and lysed by sonication in the presence of 2 μg/ml aprotinin, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, 2 μg/ml pepstatin and 2 mm PMSF. Lysates containing recombinant proteins were centrifuged at 58 545 g for 20 min at 4°C to obtain supernatant (soluble protein) and pellet (inclusion body) fractions.

Hsp65

Mycobacterium bovis BCG hsp65 protein (hsp65) present in the soluble fraction was purified by the following chromatographic steps; SP-Sepharose (200-ml column; Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden), Q-Sepharose (200-ml column; Pharmacia), Sephacryl S-300 (500-ml column; Pharmacia) and ceramic hydroxyapatite (HAP; 100-ml column; Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY). Purified hsp65 was exchanged into Dulbecco's modified PBS (DPBS)/15% glycerol and stored at −70°C.

HspE7

Hsp65–HPV16 E7 fusion protein (hspE7) present in the soluble fraction was purified by the following chromatographic steps: 0–15% ammonium sulphate precipitation, Ni-chelating Sepharose (100-ml column; Pharmacia) and Q-Sepharose (100-ml column; Pharmacia). Endotoxin was removed by extensive washing with 1% Triton X-100 on a Ni-chelating Sepharose column in the presence of 6 m guanidine–HCl (Gu–HCl). Purified hspE7 was exchanged into DPBS/15% glycerol and stored at −70°C.

(h)hspE7

N-terminal histidine-tagged hspE7 ((h)hspE7) was prepared from inclusion bodies by solubilization in 6 m Gu–HCl and loading onto a Ni-chelating Sepharose column (50 ml; Pharmacia). The column was washed extensively with 1% Triton X-100/6 m Gu–HCl to remove endotoxin and bound proteins were refolded on the resin prior to elution with a gradient of 50–500 mm imidazole. Eluted proteins were further purified on Q-Sepharose (50-ml column; Pharmacia). Purified (h)hspE7 was exchanged into DPBS/20% glycerol and stored at −70°C.

(h)E7

N-terminal histidine-tagged HPV16 E7 protein ((h)E7) was prepared from inclusion bodies by solubilization in 6 m Gu–HCl and loading onto a Ni-chelating Sepharose column (50 ml; Pharmacia). The column was washed extensively with 1% Triton X-100/6 m Gu–HCl to remove endotoxin, and bound (h)E7 was refolded on the resin and eluted by a 50–500 mm imidazole gradient. Purified (h)E7 was exchanged into DPBS/25% glycerol and stored at −70°C.

All recombinant proteins used in this study contained < 0·05 endotoxin units (EU)/μg as measured by the chromogenic Limulus ameobocyte lysate assay (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD). For hspE7, endotoxin content was further verified by in vivo rabbit pyrogenicity testing and in vitro tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) release assay from the RAW 264.7 macrophage cell line (ATCC; data not shown). SDS–PAGE analysis indicated that all recombinant proteins used in this study were purified to > 95% homogeneity, as determined by densitometric scan of coomassie blue-stained gels (data not shown).

Mice and immunizations

Female C57Bl/6 mice of approximately 8–10 weeks old were purchased from Charles River Canada (St-Constant, Que.). Immunodeficient mice with a targeted mutation in the CD8α gene [25] on the B6 background were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Immunodeficient mice with a targeted mutation in the β-chain of Ab [26] on the B6 background were purchased from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY). Animals were housed at the StressGen animal care facility according to the guidelines of the Canadian Council of Animal Care (CCAC). All immunizations with recombinant protein were given subcutaneously in the scruff of the neck in 0·2 ml PBS. Dose and regimen details are in the figure legends.

Tumour cell lines

The murine H-2b tumour cell line, TC-1 (containing the HPV16 E6, E7 and activated human Ha-ras genes) was obtained from T.C.W. and maintained as previously described [22]. The MC38 cell line, derived from a 1,2-dimethylhydrazine-induced colon adenocarcinoma in C57Bl/6 mice, was kindly provided by Dr James Young (NCI, Bethesda, MD).

In vivo antibody depletion of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells

The depleting rat anti-CD4 (GK1.5) [27] or anti-CD8 (53.6-72) [28] MoAbs were purified from ascites by (NH4)2SO4 precipitation and Protein G affinity chromatography by standard methods. Depleting MoAb (100 μg) was administered by the i.p. route for 3 consecutive days and every 3–4 days thereafter until the completion of the experiment. Preliminary experiments had shown that this MoAb dose was sufficient to deplete > 99% of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells from peripheral lymph nodes (i.e. inguinal, axillary, and cervical) as determined by flow cytometry. The presence of CD4+ T cells was determined using the non-competing anti-CD4 MoAb, RM4.4–FITC conjugate. CD8+ T cells were detected using 53.6-72–FITC. For tumour regression experiments, T cell subset depletion was verified by periodic sampling of peripheral blood from a separate cohort of identically treated (sentinel) mice. Flow cytometry confirmed depletion of > 99% of CD4+ or CD8+ T lymphocytes in sentinel mice at the time of tumour challenge and for the duration of the experiment.

Implantation and measurement of TC-1 tumour

In preparation for implantation into mice, TC-1 cells were cultured until approximately 70% confluent and harvested with DPBS containing 0·25% trypsin (Gibco BRL), followed by dilution with Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS; ICN, Aurora, OH) plus 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The cells were pelleted at 300 g, washed twice in HBSS and adjusted to 6·5 × 105 viable cells per ml as determined by trypan blue dye exclusion. In all experiments reported here, the viability of tumour cells implanted into mice was > 90%. Between 24 h and 48 h prior to tumour cell implantation, the hind flank of each mouse was shaved. TC-1 cells were injected subcutaneously into the shaven area of the flank in 0·2 ml HBSS using a 25 G needle. Starting 3–7 days later and every 3–4 days thereafter, the area was observed and palpated for the presence of a tumour nodule. In some experiments, tumour diameters were measured in two orthogonal dimensions using electronic callipers (Sylvac Ultra-Cal III; F. Fowler, Inc., A.C.T. Equipment, Vancouver, B.C.). Tumour volumes were calculated from these measurements according to: (length × width2)/2 [29]. Tumour-bearing mice were killed when moribund, as defined by the CCAC guidelines.

Cytokine analysis

Pooled splenocytes from groups of three mice were harvested and made into single-cell suspensions. Using 96-well flat-bottomed plates, 6 × 105 cells were cultured using RPMI 160 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Hyclone, Logun, UT) in a total volume of 0·2 ml. For each cytokine, triplicate cultures were restimulated for 72 h with either medium, glutathione-S-transferase (GST; 1·4 μm = 42 μg/ml) or (h)E7 (1·4 μm = 20 μg/ml). Pooled supernatants from triplicate wells were centrifuged and the cell-free portions were frozen at −70°C until analysed. Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), IL-5 and IL-10 content was measured by antibody capture ELISA using the respective pairs of antibodies according to manufacturer's instructions (PharMingen, San Diego, CA). The levels of cytokine detected in culture supernatants were extrapolated from a curve generated using recombinant cytokine as standard (PharMingen). Data are expressed as cytokine released in pg/ml + s.d. of triplicate ELISA values.

Measurement of cytolytic activity against TC-1 tumour cells

Pooled splenocytes prepared from immunized animals (three mice per group) were depleted of erythrocytes by Tris–NH4Cl treatment and 2 × 107 splenocytes were co-cultured with 1 × 106 mitomycin C-treated TC-1 cells in a total volume of 9 ml of medium using six-well plates (Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ). After 5 days, viable splenocytes were recovered by buoyant density centrifugation (Lympholyte-M; Cedarlane, Hornby, Ontario) and used in a standard 4-h 51Cr-release assay. Target cells were labelled with 100 μCi of CrO4 (NEN, Boston, MA) for 2 h. Effector cells were added to 5 × 103 labelled target cells at ratios of 11:1, 33:1 and 100:1 (tested in triplicate). After 4 h, supernatants were harvested and measured for released radioactivity using a Beckman LS6500 scintillation counter. Spontaneous and total release, determined by lysis of targets with 1% TX-100, were used to calculate percentage corrected lysis according to: 100 × (release by effectors – spontaneous release)/(total release – spontaneous release).

Statistical analysis

Cumulative survival curves were computed using Kaplan–Meier analysis. Statistical differences in tumour incidence were computed using the two-tailed Fisher's exact test. Differences in cytolytic activity were compared using the two-tailed Student's t-test. Analyses were performed using Statview 4.5 or Excel 5.0 software.

Results

Prophylactic immunization with hspE7 confers protection against recurrent TC-1 tumour challenge

To examine the ability of (h)hspE7 immunization to confer protection against in vivo challenge with TC-1, an E7-expressing tumour cell line [22,23], female C57Bl/6 mice were injected subcutaneously with PBS (control) or 1·4 nmol (100 μg) (h)hspE7 twice and then challenged with TC-1 cells (Fig. 1, day 0). This dose of (h)hspE7 was chosen based on preliminary dose-ranging experiments which indicated that following an identical protocol, 90–100% of immunized mice rejected a single s.c. challenge with TC-1 cells over a 41-day period (data not shown).

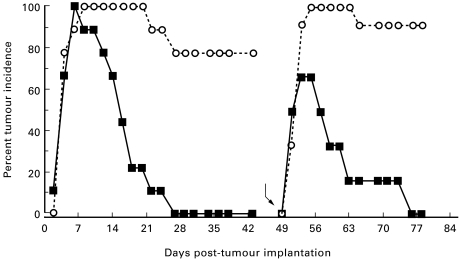

Fig. 1.

Prophylactic immunization with recombinant polyhistidine-tagged hspE7 protein ((h)hspE7) protects against TC-1 tumour challenge and re-challenge. C57Bl/6 mice (12 per group) were immunized subcutaneously in the scruff of the neck with either PBS (○) or 1·4 nmol of (h)hspE7 (▪) and then boosted 14 days later. Twelve days after the boost mice were challenged subcutaneously in the right flank with 1·3 × 105 TC-1 cells (day 0) and observed for 43 days. On day 49 (bent arrow), tumour-free mice were re-challenged with a larger dose of TC-1 cells (5 × 105) in the left flank and observed for an additional 29 days. In addition, a new group of untreated mice was challenged with tumour cells on day 49 to verify the tumourigenicity of the TC-1 inoculum. Data are presented as percent tumour incidence per group.

Figure 1 shows that TC-1 cell implantation resulted in the appearance of palpable s.c. tumours in all mice within 7 days. However, in contrast to PBS-treated mice, where tumours were present in the majority (80%) of animals for the initial observation period (43 days), complete tumour regression was observed in (h)hspE7-immunized mice. When the tumour-free animals from the (h)hspE7-treated group were re-challenged with a larger dose of TC-1 cells (Fig. 1, bent arrow), a similar temporal course of transient tumour growth and decline was observed, ultimately leading to complete tumour regression. As expected, a new cohort of unimmunized mice verified the tumourigenicity of the TC-1 cells used for re-challenge.

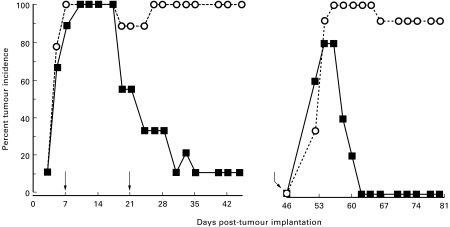

Therapeutic immunization with hspE7 induces TC-1 tumour regression and confers protection against tumour re-challenge

Given the ability of prophylactic (h)hspE7 immunization to induce TC-1 tumour rejection, experiments were performed to determine if (h)hspE7 immunization could induce regression of established TC-1 tumours. In these studies, therapy was initiated at 7 days post-tumour implantation, when 90–100% of mice had palpable s.c. tumours. Mice were injected subcutaneously with TC-1 cells on the hind flank (Fig. 2, day 0) and then 7 and 21 days later treated with PBS or 1·4 nmol (h)hspE7. By the end of the initial 45-day observation period, when tumour incidence in PBS-treated mice was 100%, (h)hspE7 therapy led to tumour regression in 90% of mice. When tumour-free mice from the (h)hspE7-treated cohort were re-challenged with a larger dose of TC-1 cells (Fig. 2, bent arrow), a similar pattern of transient tumour growth and complete tumour regression was observed in these therapeutically immunized mice as in those receiving prophylactic immunizations (Fig. 1).

Fig. 2.

Therapeutic immunization with recombinant polyhistidine-tagged hspE7 protein ((h)hspE7) induces TC-1 tumour regression and protects against tumour re-challenge. C57Bl/6 mice (nine per group) were injected subcutaneously with 1·3 × 105 TC-1 cells in the right flank (day 0). At 7 and 21 days post-implantation, the mice were immunized with PBS (○) or 1·4 nmol of (h)hspE7 (▪) in the scruff of the neck (arrows). The presence of s.c. tumour was monitored for 45 days. On day 46 (bent arrow), tumour-free mice were re-challenged subcutaneously in the left flank with a larger dose of TC-1 cells (5 × 105) and observed for an additional 33 days. In addition, a new group of untreated mice were challenged on day 46 with tumour cells to verify the tumourigenicity of the TC-1 inoculum. Data are presented as percent tumour incidence per group.

A single therapeutic immunization with hspE7 induces TC-1 tumour regression and promotes long-term survival

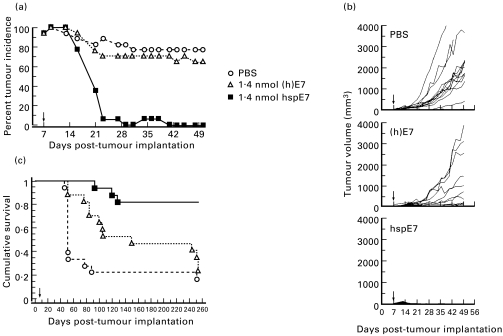

Since the data shown in Fig. 2 indicate that a decrease in tumour incidence was already apparent in (h)hspE7-treated animals prior to the time of the second immunization, a single immunization regimen was investigated. HspE7, which lacks the N-terminal polyhistidine sequence, was created so that this molecule could also progress to human trials, and its equivalence to (h)hspE7 was demonstrated in tumour regression experiments similar to those depicted in Fig. 2 (data not shown). The therapeutic efficacy of a single hspE7 immunization was compared with that of an equimolar amount of (h)E7 protein alone in mediating tumour regression. As shown in Fig. 3a, a palpable s.c. tumour was apparent in all mice by 9 days post-implantation. Within 3 weeks following a single therapeutic immunization with hspE7 there was nearly complete tumour rejection. In contrast, over this same period tumour incidence in PBS-treated and (h)E7-treated animals remained at 80% and 70%, respectively. For comparison, tumour volumes from individual mice are shown in Fig. 3b. By the conclusion of the 50-day measurement period, average tumour volume in PBS-treated mice was 1200 mm3 and a majority of animals had become moribund and were killed. In (h)E7-treated animals, tumour progression was observed in most animals and by day 50 average tumour volume was 800 mm3. However, in hspE7-treated animals tumour progression was either absent or transient, and by day 28 post-implantation 100% of animals were tumour-free.

Fig. 3.

A single therapeutic immunization with hspE7 induces TC-1 tumour regression and promotes long-term survival. C57Bl/6 mice were injected subcutaneously in the hind flank with 1·3 × 105 TC-1 cells (day 0). Seven days post-implantation, when measurable tumour (2 × 2 mm minimum) was apparent in all animals, mice were arbitrarily assigned into groups (17–18 animals per group) and immunized subcutaneously in the scruff of the neck with either PBS, 1·4 nmol of (h)E7 or 1·4 nmol hspE7 (arrow). The same cohorts of PBS (○) (h)E7 (Δ), or hspE7 (▪)-treated mice were used to produce the data displayed in (a), (b) and (c). (a) Percent tumour incidence in mice receiving hspE7 therapy. Mice were scored for the presence or absence of a palpable s.c. tumour nodule for 50 days post-implantation. (b) Individual tumour volumes from mice receiving hspE7 therapy. Tumour volumes of s.c. nodules were assessed for 50 days post-implantation (as described in Materials and Methods). (c) Long-term survival in mice receiving hspE7 therapy. Mice were monitored for survival over a 253-day period post-implantation. Mice that became moribund due to tumour burden were killed. Time to death is plotted on a Kaplan–Meier survival curve.

To determine the effect of hspE7 therapy on long-term survival, these animals were followed for a period of 253 days. The Kaplan–Meier survival plot (Fig. 3c) shows that 66% of PBS-treated animals were moribund by day 56 and only 3/18 (17%) animals survived to day 253. For the (h)E7-treated group, 53% of animals were moribund by day 154 and only 4/17 (24%) survived to day 253. In contrast, survival in the hspE7-treated group was 82% (14/17) over this 8-month period and was statistically significant relative to the PBS- and (h)E7-treated cohorts (P < 0·0001).

As a final measure of therapeutic efficacy, a single hspE7 immunization was delayed until 15 days post-tumour implantation and tumour dose was increased approximately two-fold to 2·5 × 105 cells. HspE7 therapy (1·4 nmol) was compared with administration of equimolar amounts of hsp65 alone, (h)E7 alone or an admixture of hsp65 and (h)E7. Compared with PBS treatment, only hspE7 immunization induced statistically significant regression of TC-1 tumours (P < 0·014; data not shown). The finding that therapeutic immunization with hsp65 or (h)E7 alone, or an admixture of the two proteins, does not induce significant tumour regression indicates that covalent linkage between hsp65 and E7 is required for the anti-tumour effect.

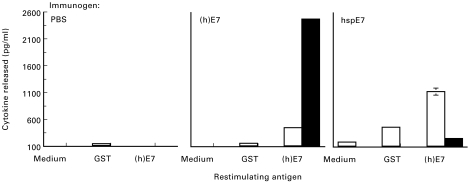

Th1 cytokine bias and cytolytic activity of splenocytes from animals immunized with hspE7

As an initial step in the identification of immune effector mechanisms associated with tumour rejection, the immune response induced by hspE7 immunization was characterized. Mice were immunized with either PBS, 1·4 nmol (h)E7 or 1·4 nmol hspE7 and boosted 14 days later. Fourteen days after the boost, splenocyte cultures were prepared and tested for their capacity to secrete IFN-γ or IL-5 upon restimulation with medium, (h)E7 or the irrelevant antigen, GST. As shown in Fig. 4, splenocyte cultures from hspE7-immunized mice released moderate levels of IFN-γ and low levels of IL-5 upon (h)E7 restimulation. In contrast, splenocytes from (h)E7-immunized animals released high levels of IL-5 and low levels of IFN-γ when restimulated with (h)E7. Cytokine release appeared to be relatively specific for E7, as co-culturing with either medium or GST (added at the molar equivalent of (h)E7) resulted in release of minimal levels of IFN-γ and no IL-5. The release of IL-10 was also measured in each case and mirrored the IL-5 response, but at a lower magnitude (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Splenocytes from hspE7-immunized mice produce IFN-γ upon restimulation. C57Bl/6 mice (three per group) were immunized subcutaneously in the scruff of the neck with either PBS, 1·4 nmol (h)E7 or 1·4 nmol hspE7 and then boosted 14 days later. Fourteen days after the boost, pooled splenocyte cultures were prepared and restimulated with medium, 1·4 μm glutathione-S-transferase (GST; as irrelevant antigen) or 1.4 μm (h)E7, as described in Materials and Methods. IFN-γ (□) and IL-5 (▪) content of 72-h culture supernatants was determined by ELISA and expressed as pg/ml ± s.d. of triplicate ELISA values.

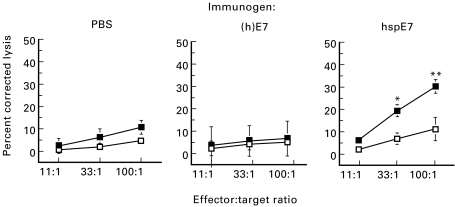

To determine if hspE7 immunization could induce cytolytic activity against TC-1 cells, pooled splenocyte cultures from groups of mice immunized with PBS, 1·4 nmol (h)E7 or 1·4 nmol hspE7 were restimulated in vitro with inactivated TC-1 cells. Viable effector cells were assessed for cytotoxic activity against TC-1 or MC38 cells, a syngeneic adherent tumour line used as a negative control. In other experiments (data not shown) the non-adherent EL4 thymoma cell line was included as a second negative control. The data presented in Fig. 5 indicate that effector cells derived from hspE7-immunized mice were significantly more cytotoxic for E7-expressing TC-1 targets than those obtained from PBS- or (h)E7-immunized mice. In addition, this cytotoxic activity appeared specific for TC-1 cells. Similar data were obtained for animals immunized with 7 nmol hspE7 (data not shown). In addition, similar levels of cytolysis were observed when CD8+ T cell-enriched splenocyte populations from hspE7-immunized mice were co-cultured with EL4 target cells pulsed with the H-2b-restricted CTL epitope E749-57 [30] (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Splenocytes from hspE7-immunized mice are cytotoxic for TC-1 cells in vitro. C57Bl/6 mice (three per group) were injected subcutaneously with either PBS, 1·4 nmol (h)E7 or 1·4 nmol hspE7. Animals were boosted 7 days later. Seven days after the boost, pooled splenocyte cultures were prepared and re-stimulated for 5 days with mitomycin C-treated TC-1 cells and tested for cytolytic activity against the following 51Cr-labelled target cells: MC38 (irrelevant target; □) or the E7-expressing tumour cell line TC-1 (▪). Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. of percent corrected lysis from three independent experiments, using ct/min of released radioactivity detected in supernatants of cultures after 4 h of effector:target incubation at the indicated ratios. **(h)E7 versus hspE7 for TC-1, P < 0·05 and PBS versus hspE7 for TC-1, P < 0·02; *PBS versus hspE7 for TC-1, P < 0·05.

Tumour regression following hspE7 immunization is CD8-dependent, CD4-independent

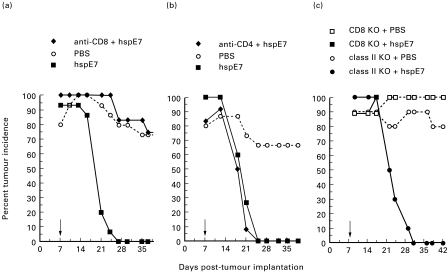

To assess the role of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells in tumour regression in mice receiving therapeutic hspE7 immunization, in vivo antibody depletion experiments were performed. Mice were depleted of CD8+ or CD4+ lymphocyte subsets by the chronic administration of the MoAbs 53.6-72 or GK1.5, respectively, then challenged with TC-1 cells. At 7 days post-implantation, lymphocyte-depleted and non-depleted cohorts were immunized with hspE7 and tumour incidence followed for 39 days. The data in Fig. 6a,b indicate that whereas CD8 depletion abolished the efficacy of hspE7 immunization, CD4 depletion had virtually no effect. These results indicate that CD8+ but not CD4+ T cells are required for tumour regression in hspE7-immunized mice. To corroborate these findings, tumour regression following hspE7 immunization was tested in mice with a targeted mutation in either the CD8α gene (CD8 KO) or the β-chain of the Ab molecule (class II KO). Figure 6c shows that hspE7 immunization is ineffective in CD8 KO mice, whereas complete tumour regression is observed in class II KO mice. Therefore, data from in vivo antibody depletion and gene ‘knockout’ approaches are consistent with a CD8-dependent, CD4-independent mechanism for tumour regression in hspE7-immunized animals.

Fig. 6.

Tumour regression following hspE7 immunization is CD8-dependent, CD4-independent. (a,b) Antibody-depleted (see Materials and methods) or non-depleted mice were injected subcutaneously in the hind flank with 1·3 × 105 TC-1 cells (day 0). Seven days post-implantation (arrow), a depleted and non-depleted group of mice (12–15 animals per group) were treated with 1·4 nmol hspE7, as indicated in the legend. A third group was treated with PBS. The presence of s.c. tumour was monitored for 37 or 39 days. Data are presented as percent tumour incidence per group. (a) CD8+ T cell-depleted mice using MoAb 53.6-72. (b) CD4+ T cell-depleted mice using MoAb GK1.5. (c) Mice with a targeted mutation in CD8α (CD8 KO) or the β-chain of Ab (class II KO) were implanted with 1·3 × 105 TC-1 cells subcutaneously in the hind flank. Seven days later (arrow), the CD8 KO and class II KO cohorts were divided into two groups (9–10 per group) and immunized with PBS or 1·4 nmol hspE7, as indicated in the legend. The presence of s.c. tumour was monitored for 42 days. Data are presented as percent tumour incidence per group.

Discussion

Adjuvant-free immunization of C57Bl/6 mice with a BCG hsp65–HPV16 E7 fusion protein (hspE7) is efficacious in the prophylaxis and therapy of an E7-expressing murine tumour cell line, TC-1. Notably, tumour regression and long-term survival occur in mice receiving a single hspE7 immunization. Consistent with induction of CTL by other hsp fusion proteins [17–21], regression of TC-1 tumours following hspE7 immunization is a feature of the intact fusion protein only. This study represents the first instance of tumour therapy with an hsp fusion protein and provides the scientific basis for the clinical application of hspE7 in the treatment of HPV-associated human cervical and anal dysplasia and carcinoma.

Consistent with the in vivo results, hspE7 immunization induced cytolytic cells which recognized TC-1 tumour cells in vitro, and splenocytes derived from hspE7-immunized mice secreted the Th1 cytokine IFN-γ following restimulation with E7 protein. This is in contrast to the immune response profile following (h)E7 immunization, which did not induce cytolytic activity against TC-1 cells and is associated with IL-5 production. Therefore, immunization of mice with the E7 antigen fused to hsp65 markedly alters the E7 recall response from that of IL-5 to IFN-γ production, suggesting a shift toward a type-1 response. Also in line with this shift is the observation that significantly lower anti-E7 antibody titres were seen in mice immunized with hspE7 than with (h)E7 (data not shown).

It is noteworthy that in the absence of CD4+ T cells (or MHC class II-restricted responses), tumour rejection is observed following treatment with hspE7. Other examples of CD4-independent CD8+ CTL induction include the delivery of CTL epitopes by DNA plasmid immunization [31] and the host response to several viral antigens [32,33]. At present, it is unknown whether in an immunocompetent animal immunized with hspE7, CD4+ T cells provide help for induction of CD8+ CTL. Under conditions of CD4 depletion, or genetic deficiency in MHC class II presentation (as in the present study), possible alternate mechanisms exist for CD8 activation, such as those mediated by CD40 [34] or IL-12 [35], or the synergistic action of IL-12 and IL-18 [36], via direct antigen-presenting cell (APC) stimulation. It is relevant that in at least one example (a SCID-CD8 TCR transgenic system) IFN-γ-producing, functional CD8+ T cell effectors were generated [37]. This suggests that in the absence of CD4+ T cells, differentiated CD8+ T cell effectors can arise, so long as appropriate CD8 priming signals are provided (see below).

Other reports have described the ability of mycobacterial hsp70 and hsp65 fusion proteins to induce CTL activity in the absence of CD4+ T cells [20,21]. The mechanism(s) by which hsp fusion proteins elicit MHC class I-restricted CTL probably involves direct stimulation of professional APC, bypassing the requirement for CD4 help. For example, it has previously been demonstrated that exposure of macrophages in vitro to bacterial and mammalian hsp results in the release of proinflammatory cytokines and up-regulation of cell adhesion molecules [38–41]. Most significant is the recent identification of toll-like receptor-4 and CD14 as candidate hsp60 receptors on human and murine macrophages, respectively [40,41]. Engagement of such ‘pattern recognition’ receptors [42] on APC is reminiscent of hsp activation of innate immune response effectors such as natural killer (NK) and γδ T cells [43,44] and is consistent with the proposal that hsp represent ‘danger signals’ to the immune system used in the surveillance of abnormal situations such as infection, cell death and transformation [45]. It is intriguing that in contrast to tumour cell-derived peptides non-covalently associated with hsp chaperones [46,47], the tumour immunity seen with hsp fusion proteins (this study and [19]) is CD4-independent. One interpretation of these data is that the fusion construct exposes structural motif(s) within the hsp that is recognized by the innate immune system, resulting in direct activation of macrophages or dendritic cells.

In the TC-1 tumour model, previous immunotherapeutic approaches have employed delivery of recombinant vaccinia virus containing a LAMP1-E7 DNA sequence [22] or the CTL peptide epitope, E749-57, in combination with an anti-CD40 MoAb [48]. Tumour prophylaxis has been demonstrated using HPV16 L1/L2–E7 fusion protein virus-like particles [49]. Thus, the TC-1 model developed by Wu and colleagues [22,23] has been validated for the testing of novel immunotherapeutics for the treatment of HPV-associated neoplasia. Based on the data presented here, we are currently testing the efficacy of hspE7 in clinical trials targeting cervical and anal dysplasias associated with HPV infection. It is relevant to note that previous phase I immunotherapy studies involving HPV16 E7 have been conducted. Frazer et al. [50] reported on the use of the recombinant fusion protein GST–E7 combined with Algammulin (inulin and Alhydrogel), as adjuvant. In another study, van Driel et al. [51] used two E7 CTL peptide epitopes and a pan-reactive HLA-DR T helper peptide emulsified with Montanide ISA 51 as adjuvant. In a third trial, DNA encoding mutated E6 and E7 from HPV16 and HPV18 was delivered using a vaccinia virus vector [52]. In all three trials, a total of 32 advanced cervical cancer patients were enrolled, some of whom were immunocompromised. Clinical responses were not observed in the GST–E7 or E7 peptide trials. Interestingly, two out of eight patients who received the vaccinia construct were reported as tumour-free and evidence for the induction of CTL was seen in one individual.

In contrast to the above approaches, hspE7 immunotherapy does not require adjuvant, obviates the need to select HLA restrictive epitopes and avoids the use of viral vectors and potentially oncogenic HPV DNA sequences. Moreover, the activation of anti-tumour CTL by hspE7 in the absence of CD4+ T cells suggests that this mode of immunotherapy may have distinct advantages in immunocompromised individuals, such as those with invasive cancer and/or HIV infection. The frequent down-regulation of class I molecules in cervical cancer [53], as in many cancers, represents a challenge to CTL-based immunotherapies. Further understanding of the unique mechanism(s) by which hsp fusions elicit cellular immunity may provide a basis for the therapy of even poorly immunogenic tumours.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Vincent Salvatori for providing support to the HPV program initiated at StressGen. The expert technical assistance of Susan Bantroch, Leah Gamache, LiJuan Sun, Heather Sweet, Yingchun Tan, Evelyn Wiebe, Joy Schembri, Cor Turnnir, Fan Zhang and Nicole Shortt is greatly appreciated. The authors also thank Dr Achim Recktenwald for assistance with protein characterization and Irina Sladecek, Mark Winnett and Shane Birley for the production of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Olsen AO, Gjoen K, Sauer T, Orstavik I, Naess O, Kierulf K, Sponland G, Magnus P. Human papillomavirus and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II-III: a population-based case-control study. Int J Cancer. 1995;61:312–5. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910610306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frisch M, Fenger C, van den Brule AJC, et al. Variants of squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal and perianal skin and their relation to human papillomaviruses. Cancer Res. 1999;59:753–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosch FX, Manos MM, Munoz N, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus in cervical cancer: a worldwide perspective. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:796–802. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.11.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nobbenhuis MA, Walboomers JMM, Helmerhorst TJM, et al. Relation of human papillomavirus status to cervical lesions and consequences for cervical-cancer screening: a prospective study. Lancet. 1999;354:20–25. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)12490-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Syrjanen KJ. Spontaneous evolution of intraepithelial lesions according to the grade and type of implicated human papillomavirus. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1996;65:45–53. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(95)02303-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsukui T, Hildesheim A, Schiffman MH, et al. Interleukin 2 production in vitro by peripheral lymphocytes in response to human papillomavirus-derived peptides: correlation with cervical pathology. Cancer Res. 1996;56:3967–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kadish AS, Ho GYF, Burk RD, Wang Y, Romney SL, Ledwidge R, Angeletti RH. Lymphoproliferative responses to human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 proteins E6 and E7: outcome of HPV infection and associated neoplasia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1285–93. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.17.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clerici M, Merola M, Ferrario E, et al. Cytokine production patterns in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: association with human papillomavirus infection. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:245–50. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.3.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tommasino M. Papillomaviruses in human cancer: the role of E6 and E7 oncoproteins. Austin, Texas: Landes Bioscience; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nindl I, Rindfleisch K, Lotz B, Schneider A, Durst M. Uniform distribution of HPV 16 E6 and E7 variants in patients with normal histology, cervical intra–epithelial neoplasia and cervical cancer. Int J Cancer. 1999;82:203–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990719)82:2<203::aid-ijc9>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kast WM, Brandt RMP, Sidney J, Drijfhout J-W, Kubo RT, Grey HM, Melief CJM, Sette A. Role of HLA-A motifs in identification of potential CTL epitopes in human papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7 proteins. J Immunol. 1994;152:3904–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ressing ME, van Driel WJ, Celis E, et al. Occasional memory cytotoxic T-cell responses of patients with human papillomavirus type-16 positive cervical lesions against a human leukocyte antigen-A*0201-restricted E7-encoded epitope. Cancer Res. 1996;56:582–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Youde SJ, Dunbar PRR, Evans EML, Fiander AN, Borysiewicz LK, Cerundolo V, Man S. Use of fluorogenic histocompatibility leukocyte antigen-A*0201/HPV 16 E7 peptide complexes to isolate rare human cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-recognizing endogenous human papillomavirus antigens. Cancer Res. 2000;60:365–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Street MD, Tindle RW. Vaccines for human papillomavirus-associated anogenital disease and cervical cancer: practical and theoretical approaches. Expert Opin Invest Drugs. 1999;8:761–76. doi: 10.1517/13543784.8.6.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murakami M, Gurski KJ, Steller MA. Human papillomavirus vaccines for cervical cancer. J Immunother. 1999;22:212–8. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199905000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mizzen L. Immune responses to stress proteins: applications to infectious disease and cancer. Biotherapy. 1998;10:173–89. doi: 10.1007/BF02678295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anthony LSD, Wu H, Sweet H, Turnnir C, Boux LJ, Mizzen LA. Priming of CD8+ CTL effector cells in mice by immunization with a stress protein-influenza virus nucleoprotein fusion molecule. Vaccine. 1998;17:373–83. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00199-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suzue K, Zhou XZ, Eisen HN, Young RA. Heat shock fusion proteins as vehicles for antigen delivery into the major histocompatibility complex class I presentation pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13146–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamazaki K, Nguyen T, Podack ER. Cutting edge: tumor secreted heat shock-fusion protein elicits CD8 cells for rejection. J Immunol. 1999;163:5178–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang Q, Richmond JFL, Suzue K, Eisen HN, Young RA. In vivo cytotoxic T lymphocyte elicitation by mycobacterial heat shock protein 70 fusion proteins maps to a discrete domain and is CD4(+) T cell independent. J Exp Med. 2000;191:403–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.2.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cho BK, Palliser D, Guillen E, Wiesneweski J, Young RA, Chen J, Eisen HN. A proposed mechanism for the induction of cytotoxic T lymphocyte production by heat shock fusion proteins. Immunity. 2000;12:263–72. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80179-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin KY, Guarnieri G, Staveley-O'Carroll KF, Levitsky HI, August JT, Pardoll DM, Wu T‐C. Treatment of established tumors with a novel vaccine that enhances major histocompatibility class II presentation of tumor antigen. Cancer Res. 1996;56:21–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ji HX, Chang EY, Lin K-Y, Kurman RJ, Pardoll DM, Wu T-C. Antigen-specific immunotherapy for murine lung metastatic tumors expressing human papillomavirus type 16 E7 oncoprotein. Int J Cancer. 1998;78:41–45. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980925)78:1<41::aid-ijc8>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Eden W, Thole JE, van der Zee R, Noordzij A, van Embden JD, Hensen EJ, Cohen IR. Cloning of the mycobacterial epitope recognized by T lymphocytes in adjuvant arthritis. Nature. 1988;331:171–3. doi: 10.1038/331171a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fung-Leung WP, Schilham MW, Rahemtulla A, Kundig TM, Vollenweider M, Potter J, van Ewijk W, Mak TW. CD8 is needed for development of cytotoxic T cells but not helper T cells. Cell. 1991;65:443–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90462-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grusby MJ, Johnson RS, Papaioannou VE, Glimcher LH. Depletion of CD4+ T cells in major histocompatibility complex class II-deficient mice. Science. 1991;253:1417–20. doi: 10.1126/science.1910207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dialynas DP, Quan ZS, Wall KA, Pierres A, Quintans J, Loken MR, Pierres M, Fitch FW. Characterization of the murine T cell surface molecule, designated L3T4, identified by monoclonal antibody GK1.5: similarity of L3T4 to the human Leu-3/T4 molecule. J Immunol. 1983;131:2445–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ledbetter JA, Herzenberg LA. Xenogeneic monoclonal antibodies to mouse lymphoid differentiation antigens. Immunol Rev. 1979;47:63–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1979.tb00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naito S, von Eschenbach AC, Giavazzi R, Fidler IJ. Growth and metastasis of tumor cells isolated from a human renal cell carcinoma implanted into different organs of nude mice. Cancer Res. 1986;46:4109–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feltkamp MCW, Smits HL, Vierboom MPM, et al. Vaccination with cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope-containing peptide protects against a tumor induced by human papillomavirus type 16-transformed cells. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:2242–9. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomson SA, Sherritt MA, Medveczky J, Elliott SL, Moss DJ, Fernando GJP, Brown LE, Suhrbier A. Delivery of multiple CD8 cytotoxic T cell epitopes by DNA vaccination. J Immunol. 1998;160:1717–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vasilakos JP, Michael JG. Herpes simplex virus class I-restricted peptide induces cytotoxic T lymphocytes in vivo independent of CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 1993;150:2346–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.von Herrath MG, Yokoyama M, Dockter J, Oldstone MBA, Whitton JL. CD4-deficient mice have reduced levels of memory cytotoxic T lymphocytes after immunization and show diminished resistance to subsequent virus challenge. J Virol. 1996;70:1072–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1072-1079.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bennett SRM, Carbone FR, Karamalis F, Flavell RA, Miller JFAP, Heath WR. Help for cytotoxic-T-cell responses is mediated by CD40 signalling. Nature. 1998;393:478–80. doi: 10.1038/30996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bianchi R, Grohmann U, Belladonna ML, Silla S, Fallarino F, Ayroldi E, Fioretti MC, Puccetti P. IL-12 is both required and sufficient for initiating T cell reactivity to a class I-restricted tumor peptide (P815AB) following transfer of P815AB-pulsed dendritic cells. J Immunol. 1996;157:1589–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okamura H, Kashiwamura S, Tsutsui H, Yoshimoto T, Nakanishi K. Regulation of interferon-gamma production by IL-12 and IL-18. Curr Opin Immunol. 1998;10:259–64. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80163-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Croft M, Carter L, Swain SL, Dutton RW. Generation of polarized antigen-specific CD8 effector populations: reciprocal action of interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-12 in promoting type 2 versus type 1 cytokine profiles. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1715–28. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Retzlaff C, Yamamoto Y, Hoffman PS, Friedman H, Klein TW. Bacterial heat shock proteins directly induce cytokine mRNA and interleukin-1 secretion in macrophage cultures. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5689–93. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5689-5693.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verdegaal EME, Zegveld ST, van Furth R. Heat shock protein 65 induces CD62e, CD106, and CD54 on cultured human endothelial cells and increases their adhesiveness for monocytes and granulocytes. J Immunol. 1996;157:369–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohashi K, Burkart V, Flohe S, Kolb H. Cutting edge: heat shock protein 60 is a putative endogenous ligand of the toll-like receptor-4 complex. J Immunol. 2000;164:558–61. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kol A, Lichtman AH, Finberg RW, Libby P, Kurt-Jones EA. Cutting edge: heat shock protein (HSP) 60 activates the innate immune response: CD14 is an essential receptor for HSP60 activation of mononuclear cells. J Immunol. 2000;164:13–17. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Medzhitov R, Janeway CA. Innate immunity: impact on the adaptive immune response. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:4–9. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80152-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Multhoff G, Botzler C, Jennen L, Schmidt J, Ellwart J, Issels R. Heat shock protein 72 on tumor cells: a recognition structure for natural killer cells. J Immunol. 1997;158:4341–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wei YQ, Zhao X, Kariya Y, Fukata H, Teshigawara K, Uchida A. Induction of autologous tumor killing by heat treatment of fresh human tumor cells: involvement of gamma delta T cells and heat shock protein 70. Cancer Res. 1996;56:1104–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matzinger P. Tolerance, danger, and the extended family. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:991–1045. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.005015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Udono H, Levey L, Srivastava PK. Cellular requirements for tumor-specific immunity elicited by heat shock proteins: tumor rejection antigen gp96 primes CD8+ T cells in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3077–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tamura Y, Peng P, Liu K, Daou M, Srivastava PK. Immunotherapy of tumors with autologous tumor-derived heat shock protein preparations. Science. 1997;278:117–20. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Diehl L, den Boer AT, Schoenberger SP, van der Voort EIH, Schumacher TN, Melief CJM, Offringa R, Toes REM. CD40 activation in vivo overcomes peptide-induced peripheral cytotoxic T-lymphocyte tolerance and augments anti-tumor vaccine efficacy. Nat Med. 1999;5:774–9. doi: 10.1038/10495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Greenstone HL, Nieland JD, de Visser KE, et al. Chimeric papillomavirus virus-like particles elicit antitumor immunity against the E7 oncoprotein in an HPV16 tumor model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1800–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Frazer IH, Tindle RW, Fernando GJP, Malcolm K, Herd K, McFadyn S, Cooper PD, Ward B. Vaccines for human papillomavirus infection and anogenital disease. Austin, Texas: R G Landes; 1999. Safety and immunogenicity of HPV16 E7/Algammulin; pp. 91–104. [Google Scholar]

- 51.van Driel WJ, Ressing ME, Kenter GG, et al. Vaccination with HPV16 peptides of patients with advanced cervical carcinoma: clinical evaluation of a phase I-II trial. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:946–52. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Borysiewicz LK, Fiander A, Nimako M, et al. A recombinant vaccinia virus encoding human papillomavirus types 16 and 18, E6 and E7 proteins as immunotherapy for cervical cancer. Lancet. 1996;347:1523–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90674-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bontkes HJ, Walboomers JMM, Meijer CJLM, Helmerhorst TJM, Stern PL. Specific HLA class I down-regulation is an early event in cervical dysplasia associated with clinical progression. Lancet. 1998;351:187–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)78209-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]