Abstract

Increased expression of the molecule CD200 in mice receiving renal allografts is associated with immunosuppression leading to increased graft survival, and altered cytokine production in lymphocytes harvested from the transplanted animals. Preferential production of IL-4, IL-10 and TGFβ occurs on donor-specific restimulation in vitro, with decreased production of IL-2, IFNγ and TNFα. These effects are enhanced by simultaneous infusion of CD200 immunoadhesin (CD200Fc) and donor CD200 receptor (CD200r) bearing macrophages to transplanted mice. C57BL/6 mice do not normally resist growth of EL4 or C1498 leukaemia tumour cells. Following transplantation of cyclophosphamide-treated C57BL/6 with T-depleted C3H bone marrow cells, or for the EL4 tumour, immunization of C57BL/6 mice with tumour cells transfected with a vector encoding the co-stimulatory molecule CD80 (EL4-CD80), mice resist growth of tumour challenge. Immunization of C57BL/6 mice with EL4 cells overexpressing CD86 (EL4-CD86) is ineffective. Protection from tumour growth in either model is suppressed by infusion of CD200Fc, an effect enhanced by co-infusion of CD200r+ macrophages. CD200Fc acts on both CD4+ and CD8+ cells to produce this suppression. These data are consistent with the hypothesis that immunosuppression following CD200–CD200r interaction can regulate a functionally important tumour growth inhibition response in mice.

Keywords: CD200, co-stimulation, immunoregulation, tumour immunity

Introduction

In experimental mice we have shown that survival of vascularized (renal) and nonvascularized (skin) allografts is increased following donor-specific portal vein (pv) immunization [1,2]. Using a DNA subtractive hybridization approach, we showed that tolerance in pv-immunized mice was associated with increased expression of a number of distinct mRNAs [3], one of which encodes a molecule referred to initially as OX2, now CD200, which is expressed on the surface of many cell types, including follicular dendritic cells (DC), as well as neuronal and endothelial cells [4]. Infusion of anti-CD200 monoclonal antibodies from the time of transplantation reversed the immunosuppression associated with pv immunization and the polarization to type-2 cytokine production seen [3]. Furthermore, a soluble immunoadhesin (CD200Fc), synthesized to link the extracellular domain of CD200 to a murine IgG2aFc region, also suppressed T cell allostimulation and type-1 cytokine production (IL-2, IFNγ) in vitro and in vivo [5]. These and other data [6] were taken to imply that DC expressed a novel ‘co-regulatory’ molecule, CD200, which controls the outcome of TCR–antigen encounter. While major costimulatory stimuli for T cell activation are provided by interactions of CD40L with CD40 and CD28 (and CTLA4) with CD80/CD86 [7–12], blocking co-stimulation alone has not reproducibly induced tolerance. We interpreted these data to reflect the importance of molecules such as CD200 in an active process of induction of immunoregulation [3]. More recently we presented data suggesting that it is the interaction of CD200 with a receptor (CD200r) on the surface of macrophages (mph) which imparts the major suppressive signal in this transplant model [13]. Hoek et al. [14] also recently reported on an CD200 knockout mouse, documenting an increased susceptibility to the autoimmune diseases EAE and collagen-induced arthritis, consistent with the hypothesis of a general immunoregulatory role for CD200 [3]. Other cells (besides those of the myeloid lineage [13,14]) have been reported to express CD200r, including a small percentage of αβTCR+ cells, and most γδTCR+ cells [13].

Interest in the field of tumour immunology has increased in the last several years with the growing evidence that it is possible to identify, and immunize animals for protection with, discrete tumour antigens [15–17]. A number of groups have reported on the use of DC coated with tumour antigen, or expressing tumour antigen (following transfection with cDNAs encoding the antigen), as immunogens to induce tumour rejection [18–22]. An alternative approach has used tumour cells themselves, transfected with gene(s) such as those controlling cytokines or expression of co-stimulatory molecules (CD80/CD86) on the cell surface, as an immunogen [11,23–26]. In an interesting model using as recipients animals receiving allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (BMT), which mimicks a therapy used for treatment of leukaemia in man, Blazar et al. reported that it was possible to promote a graft-versus-leukaemia (GVL) effect, without unwanted graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), by preimmunizing tumour transplanted mice with tumour cells transfected to express CD80, but not CD86 [27]. In the experiments described below we have asked whether CD200–CD200r interactions can also suppress tumour immunity in C57BL/6 mice to the syngeneic leukaemia cells EL4 or C1498 seen following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (from C3H donors), or following preimmunization with CD80-transfected tumour cells in Freund's adjuvant.

Materials and methods

Mice

Male C3H/HEJ, BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbour, Maine, USA. Mice were housed five per cage and allowed food and water ad libitum. All mice were used at 8–12 weeks of age.

Monoclonal antibodies

The following monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs) were obtained from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA, USA) unless stated otherwise: anti-IL-2 (S4B6, ATCC; biotinylated JES6–5H4); anti-IL-4 (11B11, ATCC; biotinylated BVD6–24G2); anti-IFNγ (R4-6A2, ATCC; biotinylated XMG1·2); anti-IL-10 (JES5-2A5; biotinylated, SXC-1); anti-IL-6 (MP5–20F3; biotinylated MP5-32C11); anti-TNFα (G281-2626; biotinylated MP6-XT3); FITC anti-CD80, FITC anti-CD86 and FITC anti-CD40 were obtained from Cedarlane Labs, Hornby, Ontario, Canada. The hybridoma producing DEC205 (antimouse dendritic cells) was a kind gift from Dr R.Steinman, and was labelled directly with FITC. FITC anti-H2Kb, FITC anti-H2Kk and antithy1·2 monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs) were obtained from Cedarlane Labs, Hornby, Ontario, Canada. Unconjugated and PE-conjugated rat antimouse CD200 was obtained from BioSpark Inc., Mississauga, Ontario, Canada [28]. CD200Fc was prepared in a Baculovirus expression system, using a cDNA encoding a murine IgG2aFc region (a kind gift from Dr T. Strom, Harvard, USA) which carried mutations to delete complement binding and FcR sites, as we have described elsewhere [5]. Rat monoclonal antibody to CD200r was prepared from rats immunized with CHO cells transfected to express a cDNA encoding CD200r [29]. Anti-CD4 (GK1·5, rat IgG2b) and anti-CD8 (2·43, rat IgG2b) were both obtained from ATCC, and used for in vivo depleteion by i.v. infusion of 100 µg Ig/mouse weekly. A control IgG2b antibody (R35·38), as well as strepavidin horseradish peroxidase and recombinant mouse GM-CSF, was purchased from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA, USA).

Preparation of cells

Single-cell spleen suspensions were prepared aseptically and after centrifugation cells were resuspended in α-minimal essential medium (αMEM) supplemented with 2-mercaptoethanol and 10% fetal calf serum (αF10). CD200r+ LPS splenic Mph, stained (> 20%) with FITC-CD200Fc, were obtained by velocity sedimentation of cells cultured for 48 h with 1 µg/ml LPS [13]. Bone marrow cells were flushed from the femurs of donor mice, washed and resuspended in αF10. Cells were depleted of mature T lymphocytes using antithy 1·2 and rabbit complement.

C1498 (a spontaneous myeloid tumour) and EL4 (a radiation-induced thymoma tumour) cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA). Cells used for transplantation into mice were passaged weekly (5 × 106 cells/mouse) intraperitoneally in stock 8-week-old C57BL/6 recipients. For experimental tumour challenge either 5 × 106 EL4 tumour cells or 5 × 105 C1498 cells were given intraperitoneally to groups of six mice (see Results). Animals were sacrificed when they became moribund. EL4 cells stably transfected to express CD80 or CD86 were obtained from Dr J. Allison, Cancer Research Laboratories, UC Berkeley, CA, USA, while C1498 transfected with CD80/CD86 (cloned into pBK vectors) were produced in the author's laboratory. Tumour cells (parent and transfected) were stored at −80°C and thawed and cultured prior to use. Cells used for immunization, including the tumour cells transfected with CD80/CD86, were maintained in culture in αMEM medium supplemented with 10% FCS. Untransfected and transfected cells of each tumour line were used for immunization within two passages in culture. Over this time in culture transfected cells repeatedly showed stable expression (by FACS) of CD80/CD86 (> 80% positive for each tumour assayed over a 6-month period with multiple vials thawed and cultured). Non-transfected tumour cells did not stain with these MoAbs (< 2%).

CD200r+ cells were obtained from lymphocyte-depleted murine spleen cells. Cells were treated with rabbit antimouse lymphocyte serum and complement (both obtained from Cedarlane Laboratories, Hornby, Ontario, Canada), cultured with LPS (10 µg/ml) for 24 h, and separated into populations of different size by velocity sedimentation [13]. Small CD200r+ cells stained > 65% by FACS with anti-CD200r antibody [29].

Bone marrow transplantation (BMT)

C57BL/6 mice received 300 mg/kg cyclophosphamide i.v. 24 h before intravenous infusion of 20 × 106 T-depleted C3H or C57BL/6 bone marrow cells. Immediately prior to use for tumour transplantation (28 days following bone marrow engrafting), a sample of PBL (50 µl/mouse) was obtained from the tail vein of individual mice and analysed by FACS with FITC-anti-H2Kk or FITC-anti-H2Kb MoAb. Cells from normal C57BL/6 or C57BL/6 reconsituted C57BL/6 mice were 100% H2Kb positive, as expected. In similar fashion, PBL from C3H mice were 100% H2Kk positive. H2Kk positive cells in the C3H-reconstituted C57BL/6 mice by FACS comprised 85% ± 8·5% of the total cell population (mean over ∼ 100 mice used in the studies described below). Mice in all groups were gaining weight and healthy.

Cytotoxicity and cytokine assays

In allogeneic mixed leucocyte cultures (MLC) used to assess cytokine production or CTL, responder spleen cells were stimulated with equal numbers of mitomycin-C treated (45 min at 37°C) spleen stimulator cells in triplicate in αF10. Supernatants were pooled at 40 h from replicate wells and assayed in triplicate in ELISA assays for lymphokine production as follows, using capture and biotinylated detection MoAbs as described above. Varying volumes of supernatant were bound in triplicate at 4°C to plates precoated with 100 ng/ml MoAb, washed ×3, and biotinylated detection antibody added. After washing, plates were incubated with strepavidin-horseradish peroxidase (Cedarlane Laboratories), developed with appropriate substrate and O.D.405 determined using an ELISA plate reader. Recombinant cytokines for standardization were obtained from Pharmingen (USA). All assays showed sensitivity in the range 40–4000 pg/ml. CTL assays were performed at 5 days using cells harvested from the same cultures (as used for cytokine assays). Various effector : target ratios were used in 4 h 51Cr release tests with 72 h ConA activated spleen cell blasts of stimulator genotype.

Quantification of CD200 mRNA by PCR

RNA extraction from spleen tissue of tumour-injected mice was performed using Trizol reagent. The O.D.280/260 of each sample was measured and reverse transcription performed using oligo (dT) primers (27–7858: Pharmacia, USA). cDNA was diluted to a total volume of 100 µl with water and frozen at − 70°C until use in PCR reactions with primers for mouse CD200 and GAPDH [3]. Different amounts of standard cDNA from 24 h cultures of LPS-stimulated peritoneal macrophages (known to express CD200 and GAPDH) were amplified in six serial 1 : 10 dilutions for 30 cycles by PCR, in the presence of a tracer amount of 32P. Samples were analysed in 12·5% polyacrylamide gels, the amplicons cut from the gel and radioactivity measured in a β-counter. A standard curve was drawn for each set of primer pairs (amplicons). cDNAs from the various experimental groups were assayed in similar reactions using 0·1 µl cDNA, and all groups were normalized to equivalent amounts of GAPDH. CD200 cDNA levels in the different experimental groups were then expressed relative to the cDNA standard (giving a detectable 32P signal over five log10 dilutions). Thus a value of 5 (serial dilutions) indicates a test sample with approximately the same cDNA content as the standard, while a value of 0 indicates a test sample giving no detectable signal in an undiluted form (< 1/105 the cDNA concentration of the standard).

Results

Growth of EL4 or C1498 tumour cells in C57BL/6 mice, and in allogeneic (C3H) BMT mice

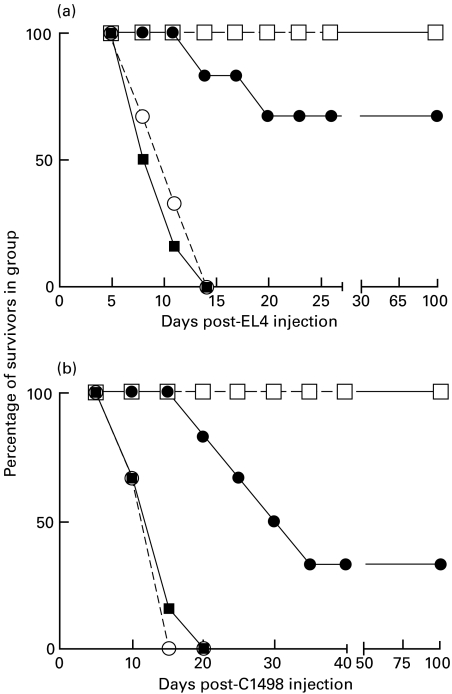

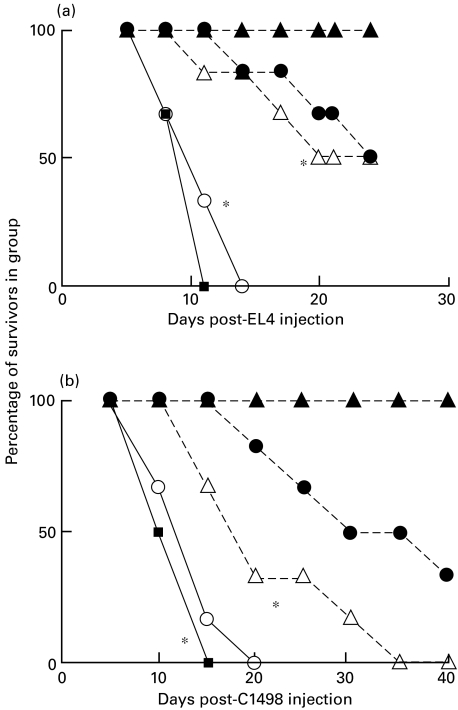

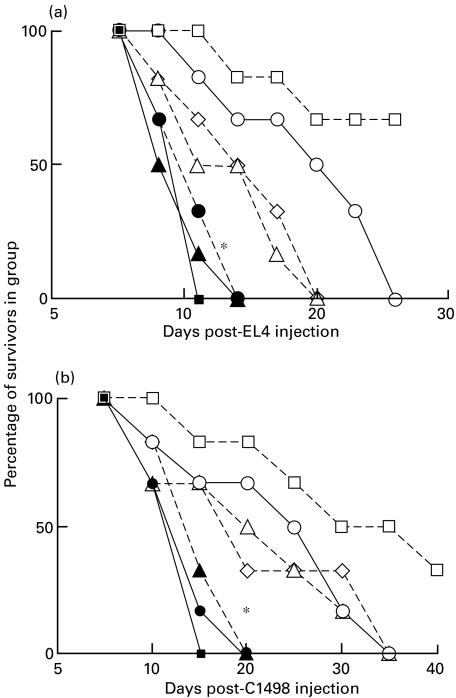

Groups of six C57BL/6 mice received i.v. infusions of 300 mg/kg cyclophosphamide (in 0·5 ml PBS). A control group received PBS only, as did a control group of six C3H mice. 24 h later cyclophosphamide-treated C57BL/6 mice received i.v. injection of 20 × 106 T-depleted bone marrow cells pooled from C57BL/6 mice (syngeneic transplant) or C3H mice (allogeneic transplantation). All groups of animals received intraperitoneal injection (in 0·5 ml PBS) of 5 × 106 EL4 or 5 × 105 C1498 tumour cells (see Fig. 1) 28 days later. Animals were monitored daily post-tumour inoculation.

Fig. 1.

Inhibition of EL4 or C1498 tumour growth in C3H bone marrow reconstituted C57BL/6 mice. Groups of six BL/6 mice received 20 × 106 T-depleted BL/6 or C3H bone marrow cells 24 h following cyclophosphamide treatment. 5 × 106 EL4 or 5 × 105 C1498 tumour cells were injected 28 days later into these mice, and control BL/6 or C3H mice. > 85% of PBL from C3H reconstituted BL/6 were stained by FITC anti-H2Kk MoAb at this time. ▪, Untreated C57BL/6; ○, BL/6 with BL/6 bm; •, BL/6 with C3H bm; □, untreated C3H.

Data in Fig. 1 (one of two such studies) show clearly that while C3H mice rejected both EL4 and C1498 (allogeneic) leukaemia cell growth, 100% mortality was seen within 9–12 days in normal C57BL/6 mice, or in syngeneic bone marrow reconstituted mice. Interestingly, despite the absence of overt GVHD (as defined by weight loss and overall health), two-thirds of C3H reconstituted C57BL/6 mice rejected EL4 tumour cells, reflecting the existence of a graft versus leukaemia effect (GVL) (panel a, Fig. 1), and there was a marked delay of death for mice inoculated with C1498 leukaemia cells (panel b). In separate studies similar findings were made using tumour inocula (for EL4/C1498, respectively) ranging from 2 × 106 to 10 × 106 or 1·5 × 105−10 × 105 (R.M.G., unpublished).

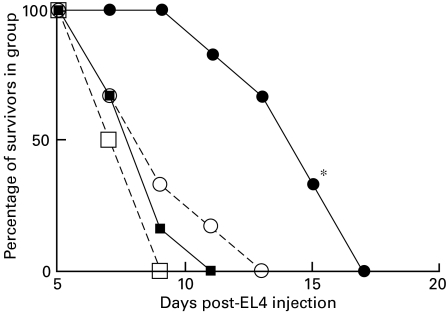

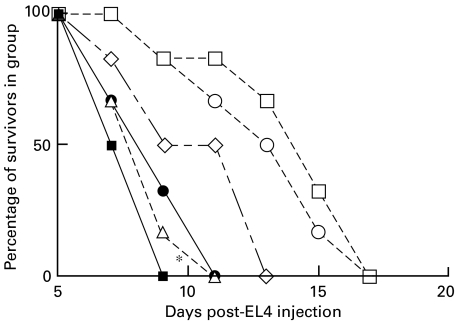

Immunization of normal C57BL/6 mice for protection against EL4 tumour growth

Blazar and coworkers reported immunization for protection from tumour growth in C57BL/6 mice using tumour cells transfected to overexpress mouse CD80 [27]. Using CD80 and CD86 transfected EL4 cells obtained from this same group, or C1498 cells tranfected with CD80/CD86 in our laboratory, we immunized groups of six C57BL/6 mice i.p. with complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA) alone, or with CFA mixed with 5 × 106 mitomycin-C treated tumour cells, or CD80/CD86 transfected tumour. Animals received two injections at 14-day intervals. Ten days after the last immunization all mice received 5 × 106 EL4 tumour cells, or 5 × 105 C1498 cells, and mortality followed. Data are shown in Fig. 2(one of two studies), for EL4 only.

Fig. 2.

EL4 tumour growth in BL/6 mice immunized twice, at 14-day intervals, with 5 × 106 EL4 cells transfected to express CD80 or CD86. 5 × 106 EL4 cells were injected as tumour challenge 10 days after the last immunization. *(•), P < 0·05, compared with untreated BL/6 control mice,  . ▪, Untreated C57BL/6; ○, EL4 immunized; •, EL4-CD80 immunized; □, EL4-CD86 immunized.

. ▪, Untreated C57BL/6; ○, EL4 immunized; •, EL4-CD80 immunized; □, EL4-CD86 immunized.

In agreement with a number of other reports, mice preimmunized with CD80-transfected EL4 survive significantly longer after challenge with viable EL4 tumour cells than non-immunized animals, or those immunized with non-transfected cells or CD86 transfected cells (P < 0·05) − see also Fig. 5 below. Similar data were obtained using CD80-transfected C1498 cells (R.M.G., unpublished). In separate studies (not shown) mice immunized with tumour cells in the absence of Freund's adjuvant failed to show any protection from tumour growth. However, equivalent protection (to that seen using Freund's adjuvant) was also seen using concomitant immunization with poly(I:C) (100 µg/mouse) as adjuvant (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Inhibition of immunity to EL4 tumour cells in EL4-CD80 immunized BL/6 mice using CD200Fc − see Fig. 2 and text for details. Mice received i.v. infusion of control IgG or CD200Fc as described in Fig. 4. *P < 0·05, comparing normal Ig injected controls and CD200Fc injected mice (▴, ▵). ▪, Untreated C57BL/6; ○, EL4 immunized; ▴, EL4-CD80 immunized + IgG; □, EL4-CD86 immunized; ▵, EL4-CD80 immunized + CD200Fc.

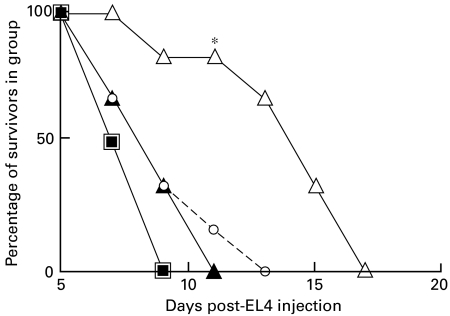

Role of CD4+ and/or CD8+ cells in modulation of tumour growth after BMT

In order to investigate the effector cells responsible for leukaemia growth-inhibition in mice transplanted with allogeneic bone marrow (see Fig. 1), BMT recipients received weekly injections of 100 µg/mouse anti-CD4 (GK1·5) or anti-CD8 (2·43) MoAb, followed at 28 days by leukaemia cell injection as described for Fig. 1. Depletion of CD4 and CD8 cells in all mice with these treatments was > 98% as defined by FACS analysis (not shown).

As shown in Fig. 3 (data from one of three studies), and in agreement with data reported elsewhere [27], in this BMT model tumour growth inhibition for EL4 cells is predominantly a function of CD8 rather than CD4 cells (compare ▵ in panel a, versus ○), while for C1498 leukaemia cells growth inhibition was equally, but not completely, inhibited by infusion of either anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 MoAb (see panel b of Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Suppression of growth inhibition in C57BL/6 BMT recipients of EL4 or C1498 tumour cells (see Fig. 1) following 4-weekly infusions of 100 µg/mouse anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 MoAb, beginning on the day of BMT (tumour cells were injected at 28 days post-BMT). Data are shown for six mice/group. *P < 0·02 compared with •; **P < 0·05 compared with •. ▴, B:C + anti-CD8; ▵, B:C + anti-CD8; ○, B:C + anti-CD4; •, BL/6 with C3H (B:C); ▪, normal BL/6.

Evidence that tumour rejection in BMT mice is regulated by CD200

Previous studies in rodent transplant models have implicated expression of a novel molecule, CD200, in the regulation of an immune rejection response. Specifically, blocking functional expression of CD200 by a monoclonal antibody to murine CD200 prevented the increased graft survival which followed donor-specific pretransplant immunization, while a soluble form of CD200 linked to murine IgG Fc (CD200Fc) was a potent immunosuppressant [3,5]. In order to investigate whether expression of CD200 was involved in regulation of tumour immunity, we studied first the effect of infusion of CD200Fc on suppression of resistance to growth of EL4 or C1498 tumour in BMT mice, as described in Fig. 1, and secondly the effect of CD200Fc infusion in mice immunized with CD80-transfected tumour cells, as described in Fig. 2. Note that this CD200Fc lacks binding sites for mouse complement and FcR (see Materials and methods, and [5]). In all cases control groups of mice received infusions of equivalent amounts of pooled normal mouse IgG. Data for these studies are shown in Figs 4 and 5, respectively (data from one of two studies in each case).

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of immunity to EL4 or C1498 tumour challenge following infusion of CD200Fc in C57BL/6 mice reconstituted with C3H bone – see Fig. 1 and text for more details. Cyclophosphamide-treated BL/6 mice received bone marrow rescue with T-depleted C3H or BL/6 cells. 28 days later all mice, and groups of control normal C3H mice, received i.p. injection with 5 × 106 EL4 or 5 × 105 C1498 tumour cells. Bone marrow reconstituted mice received further i.v. infusion of normal mouse IgG or CD200Fc (10 µg/mouse/injection) five times at 2-day intervals beginning on the day of tumour injection. *P < 0·02 compared with normal Ig control (i.e. compare ▵ with ▴; and ○ with •). ▪, BL/6 with BL/6; •, BL/6 with C3H:CD200Fc; ○, BL/6 with C3H:CD200Fc; ▴, normal C3H + IgG; ▵, normal C3H:CD200Fc.

It is clear that suppression of growth of either EL4 or C1498 tumour cells in BMT mice is inhibited by infusion of CD200Fc, but not by pooled normal mouse IgG (Fig. 4). CD200Fc also caused increased mortality in EL4 or C1498 injected normal C3H mice (see ▵ in panels a and b of Fig. 4), as predicted from our earlier data showing suppression of alloreactivity by this reagent [5]. Data in Fig. 5 show that resistance to EL4 tumour growth in EL4-CD80 immunized mice (as documented in Fig. 2) is also inhibited by infusion of CD200Fc. In separate studies (not shown) a similar inhibition of immunity induced by CD80 transfected C1498 was demonstrated using CD200Fc.

Effect of anti-CD200 MoAb on resistance to tumour growth in mice immunized with CD80/CD86 transfected tumour cells

As further evidence for a role for CD200 expression in tumour immunity in EL4-CD80/EL4-CD86 or C1498-CD80/C1498-CD86 immunized mice we examined the effect of infusion of an anti-CD200 MoAb on EL4 or C1498 tumour growth in this model. Infusion of anti-CD200 into mice preimmunized with EL4-CD86, or C1498-CD86 uncovered evidence for resistance to tumour growth (compare ▪ and □ in panels a and b of Fig. 6). Separate studies (not shown) revealed that anti-CD200 produced no significant perturbation of EL4 growth in the EL4 or EL4-CD80 immunized mice, or of C1498 growth in C1498 or C1498-CD86 immunized mice. We interpreted these data to suggest that immunization with EL4-CD86 or C1498-CD86 elicited an antagonism of tumour immunity resulting from increased expression of CD200. Thus, blocking the functional increase of CD200 expression with anti-CD200 reversed the inhibitory effect. Note that in studies not shown we have reproduced these same effects of anti-CD200 (in mice immunized with CD86-transfected tumour cells) with F(ab′)2 anti-CD200 (R.M.G., unpublished).

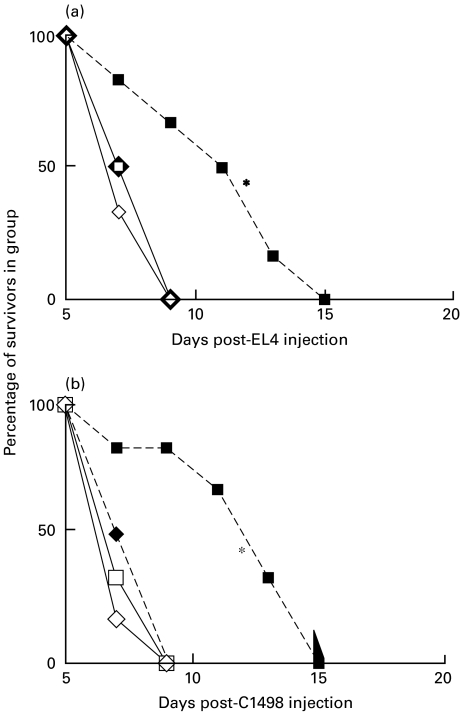

Fig. 6.

<Improved tumour immunity in EL4-CD86 or C1498-CD86 immunized C57BL/6 mice following infusion of anti-CD200 MoAb. See legend to Fig. 2 and text for more details. Where shown, groups of mice received i.v. infusion of anti-CD200, 100 µg/mouse, on three occasions at 3-day intervals beginning on the day of tumour injection. *P < 0·05 (▪) compared with non-immunized controls, with/without anti-CD200 (□, ♦). (a) ◊, Untreated C57BL/6; □, EL4-CD86 immunized; ▪, EL4-CD86 immunized + 3B6; ♦, 3B6 alone. (b) ◊, Untreated C57BL/6; □, C1498-CD86 immunized; ▪, C1498-CD immunized + 3B6; ♦, 3B6 alone.

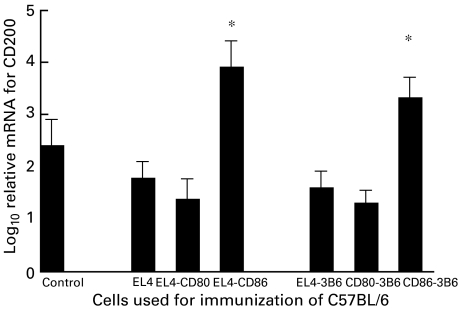

To confirm that immunization with CD86-transfected tumour cells was indeed associated with increased expression of CD200, we repeated the study shown in Fig. 6, and sacrificed three mice/group at 4 days following EL4 tumour injection. RNA was isolated from the spleen of all mice, and assayed by quantitative PCR for expression of CD200 (using GAPDH as ‘housekeeping’ mRNA control). Data for this study are shown in Fig. 7, and show convincingly that CD200 mRNA expression was > fivefold increased following preimmunization with EL4-CD86, a condition associated with increased tumour growth compared with EL4-immunized mice (Figs 2 and 6). In dual-staining FACS studies (not shown) with PE-anti-CD200 and FITC-DEC205, the predominant CD200+ population seen in control and immunized mice were DEC205+ (> 80%) − see also [6]. Similar results were obtained using C1498 tumour cells (data not shown).

Fig. 7.

Log10 relative concentrations of CD200 mRNAs compared with standardized control mRNA − see Materials and methods for technique used for quantification. All samples were first normalized for equivalent concentrations of GAPDH mRNA. Values shown represent arithmetic means ± s.d. for three individual samples for each time point. Mice were preimmunized with CD80/CD86-transfected tumour cells as described in the text. *P < 0·02 compared with untreated control, or mice immunized with EL4 or EL4-transfected with CD80.

Given this increase in CD200 expression following preimmunization with CD86-transfected cells, and the evidence that CD200 is associated with delivery of an immunosuppressive signal to antigen encountered at the same time, we also examined the response of spleen cells taken from these C57BL/6 mice to allostimulation (with mitomycin-C treated BALB/c spleen cells), in the presence/absence of anti-CD200 MoAb. Data from one of 3 studies are shown in Table 1. Interestingly, mice preimmunized with EL4-CD86 cells show a decreased ability to generate CTL on alloimmunization with third-party antigen (BALB/c), and decreased type-1 cytokine production (IL-2, IFNγ), with some trend to increased type-2 cytokines (IL-4 and IL-10). These effects were reversed by inclusion of anti-CD200 in culture, consistent with the hypothesis that they result from increased delivery of an immunosuppressive signal via CD200 in spleen cells obtained from these animals [3].

Table 1.

Preimmunization of mice with EL4-CD86 causes increased CD200 expression which leads to generalized suppression to newly encountered alloantigen

| Cytokines in supernatant § | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumour used for immunization † | % Lysis ‡ | IL-2 | IL-4 | IFNγ | IL-10 |

| None (control) | 43 ± 5·5 | 980 ± 125 | 50 ± 10 | 455 ± 65 | 35 ± 10 |

| EL4 | 41 ± 6·2 | 890 ± 135 | 60 ± 15 | 515 ± 70 | 30 ± 10 |

| EL4-CD80 | 46 ± 6·3 | 955 ± 140 | 45 ± 15 | 525 ± 55 | 30 ± 10 |

| EL4-CD86 | 16 ± 4·2* | 420 ± 75* | 125 ± 20* | 240 ± 40* | 120 ± 20* |

| None (control) + | 46 ± 5·8 | 950 ± 105 | 55 ± 15 | 490 ± 60 | 40 ± 10 |

| EL4 + | 44 ± 4·9 | 940 ± 115 | 50 ± 20 | 530 ± 60 | 35 ± 10 |

| EL4-CD80 + | 44 ± 6·0 | 905 ± 120 | 60 ± 15 | 555 ± 75 | 35 ± 10 |

| EL4-CD86 + | 39 ± 4·29 | 870 ± 125 | 75 ± 20 | 540 ± 65 | 40 ± 15 |

Spleen cells were pooled from three C57BL/6 mice/group, pretreated as described in the text, by immunization with 5 × 10 6 mitomycin-C treated EL4 tumour cells, or CD80/CD86-transfected tumour cells, in complete Freund's adjuvant 4 days earlier; 5 × 106 spleen cells were incubated in triplicate with equal numbers of mitomycin-C treated BALB/c spleen stimulator cells.

+ indicates anti-CD200 (anti-OX2) added to cultures (5 µg/ml) % specific lysis in 4-h 51Cr release assays with 72-h cultured BALB/c spleen Con A blast cells (effector : target ratio shown is 100 : 1).

Cytokines in culture supernatants assayed in triplicate by ELISA at 40 h (see Materials and methods). Data represent pg/ml except for IL-10 (ng/ml).

P < 0·05 compared with all groups.

Evidence for an interaction between CD200 and CD200r ± cells in inhibition of EL4 tumour growth

Inhibition resulting from infusion of CD200Fc into mice follows an interaction with immunosuppressive CD200r+ cells [13]. At least one identifiable functionally active population of suppressive CD200r+ cells was described as a small, F4/80+ cell in a pool of splenic cells following LPS stimulation [13] − F4/80 is a known cell surface marker for tissue macrophages. In a further study we investigated whether signalling induced by CD200–CD200r interaction (where CD200r+ cells were from lymphocyte-depleted, LPS stimulated spleen cells) was behind the suppression of tumour immunity seen following CD200Fc injection. All groups of six recipient mice received tumour cells i.p. In addition to infusion of CD200Fc as immunosuppressant (○ in Fig. 8), one group of C3H reconstituted animals received CD200r+ cells (▵ in Fig. 8: > 65% of these cells stained with an anti-CD200r MoAb), while a final group received a mixture of both CD200Fc and CD200r+ cells (▴). It is clear from Fig. 8 that it is this final group, in which interaction between CD200 and CD200r is possible, which showed maximum inhibition of tumour immunity compared with the C3H reconstituted control mice (•).

Fig. 8.

Increased inhibition of tumour immunity using infusion of CD200Fc with CD200r+ cells in C57BL/6 recipients of C3H bone marrow − see text and Materials and methods for more details. In this experiment some mice received not only CD200Fc with EL4 or C1498 tumour, but in addition a lymphocyte-depleted, LPS-stimulated, macrophage population stained (> 65%) with anti-CD200r MoAb (2F9). *(○), P < 0·05, compared with control allogeneic bone marrow recipients (•); **(▴), P < 0·05, compared with mice receiving CD200Fc alone (○). ▴, B:C + CD200Fc + CD200r+ cells; ▵, B:C + CD200r+ cells; ○, B:C + CD200Fc; •, BL/6 with C3H (B:C); ▪, normal BL/6.

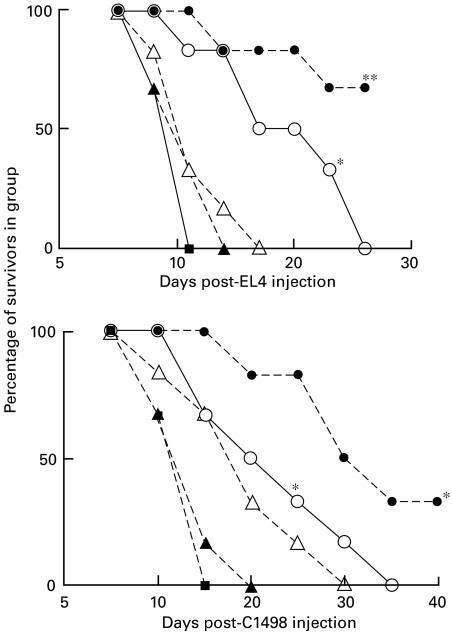

Role of CD4 ± and/or CD8 ± cells in CD200 regulated modulation of tumour growth after BMT

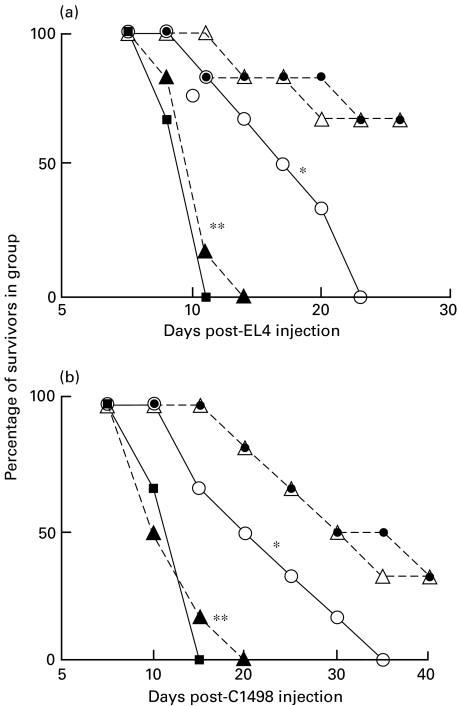

Data in Fig. 3 above and elsewhere [27] show that tumour growth inhibition for EL4 cells is predominantly a function of CD8 rather than CD4 cells, while for C1498 leukaemia cells growth inhibition was equally, but not completely, inhibited by infusion of either anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 MoAb. To investigate the role of CD200 in the protection mediated by different T cell subclasses, the following additional studies were performed. In the first, C57BL/6 recipients of C3H BMT received (at 28 days post-BMT) inoculations of EL4 or C1498 tumour cells along with anti-CD4, anti-CD8 or CD200Fc alone, or combinations of (anti-CD4+ CD200Fc) or (anti-CD8+ CD200Fc). Survival was followed as before (see Fig. 9:one of two studies). In a second study (Fig. 10:data from one of two such experiments) a similar treatment regimen of MoAb or CD200Fc alone or in combination was used to modify growth of EL4 tumour cells in mice preimmunized with EL4-CD80 cells, as described earlier in Fig. 2.

Fig. 9.

Combinations of CD200Fc and anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 MoAb produce increased suppression of tumour growth inhibition in C57BL/6 recipients of C3H BMT. Groups of six mice received weekly i.v. infusions of 100 µg anti-T cell MoAb or five i.v. infusions of 10 µg/mouse CD200Fc, alone or in combination, beginning on the day of tumour injection (28 days post-BMT). *P < 0·02 compared with no antibody (and no CD200Fc) control group, □. •, B:C + anti-CD4/CD200Fc; ○, B:C + anti-CD4; ◊, B:C + CD200Fc; ▵, B:C + anti-CD8; ▴, B:C + anti-CD8/CD200Fc; ▪, normal; □, BL/6 with C3H (B:C).

Fig. 10.

Effect of combined CD200Fc and anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 MoAb on suppression of EL4 tumour growth inhibition in C57BL/6 recipients preimmunized with EL4-CD80 transfected cells (see Fig. 2). Data are shown for groups of six mice/group. Weekly i.v. infusions of 100 µg anti-T cell MoAb or five i.v. infusions of 10 µg/mouse CD200Fc, alone or in combination, were begun on the day of tumour injection (10 days after the final immunization with EL4-CD80 cells). *P < 0·02 compared with no antibody (and no CD200Fc) control group, □. ▪, Untreated C57BL/6; ▵, EL4-CD80 immunized + anti-CD8; □, EL4-CD80 immunized; ○, EL4 CD80 immunized + anti-CD4; ◊, EL4-CD80 immunized + CD200Fc; •, EL4-CD80 immunized + anti-CD4/CD200Fc.

Data in panel a of Fig. 9 confirm the effects previously documented in Figs 3 and 4, that CD200Fc and anti-CD8 each significantly impaired the growth inhibition in BMT recipients of EL4 cells, while anti-CD4 mAb was less effective. Combinations of CD200Fc and either anti-T cell MoAb led to even more pronounced inhibition of tumour immunity in the BMT recipients, to levels seen with non-allogeneic transplanted mice (compare • and ▴ to control, ▪, Fig. 9). Data with C1498 tumour cells (panel b) were somewhat analogous, although as in Fig. 3 anti-CD4 alone produced equivalent suppression of growth inhibition to anti-CD8 with this tumour (compare □ and ▵). As was the case for the EL4 tumour, combinations of CD200Fc and either anti-T cell MoAb caused essentially complete suppression of C1498 tumour growth inhibition (compare • and ▴ to control,  ). Both sets of data, from panels a and b, are consistent with the notion that CD200Fc blocks (residual) growth-inhibitory functional activity in both CD4 and CD8 cells, thus further inhibiting tumour immunity remaining after depletion of T cell subsets.

). Both sets of data, from panels a and b, are consistent with the notion that CD200Fc blocks (residual) growth-inhibitory functional activity in both CD4 and CD8 cells, thus further inhibiting tumour immunity remaining after depletion of T cell subsets.

Data in Fig. 10, using EL4 immunized BL/6 mice, also showed combinations of CD200Fc and anti-CD4 treatment produced optimal suppression of tumour immunity to EL4 cells, consistent with an effect of CD200Fc on CD8+ cells. Anti-CD8 alone (▵ in Fig. 10) abolished tumour immunity in these studies, so any potential additional effects of CD200Fc on CD4+ cells could not be evaluated.

Discussion

In the studies described above, we have asked whether expression of the molecule CD200, reported previously to down-regulate rejection of tissue/organ allografts in rodents [3], was implicated in immunity to tumour cells in syngeneic hosts. Two model systems were used. The first, in which tumour cells are injected into mice which had received an allogeneic bone marrow transplant following cyclophosphamide preconditioning, has been favoured as a model for studying potential innovative treatments of leukaemia/lymphoma in man [27,30–32]. In the second, EL4 or C1498 tumour cells were infused into BL/6 mice which had been preimmunized with tumour cells transfected to overexpress the co-stimulatory molecules CD80 or CD86. These studies were stimulated by the growing interest in such therapy for immunization of human tumour patients with autologous transfected tumour cells [11,23–26].

In both sets of models we found evidence for inhibition of tumour growth (Fig. 1 and 2) which could be further modified by treatment designed to regulate expression of CD200. Infusion of CD200Fc suppressed tumour immunity (led to increased tumour growth and faster mortality) in both models (Figs 4 and 5), while anti-CD200 improved tumour immunity in mice immunized with CD86-transfected EL4 or C1498 tumour cells (Fig. 6). We interpreted this latter finding as suggesting that the failure to control tumour growth following immunization with EL4-CD86 or C1498-CD86 was associated with overexpression of endogenous CD200, a hypothesis which was confirmed by quantitative PCR analysis of tissue taken from such mice (Fig. 7). CD200 was expressed predominantly on DEC205+ cells in the spleen of these mice (see text), which was associated with a decreased ability of these spleen cell populations to respond to allostimulation in vitro (see Table 1). Non-antigen-specific inhibition following CD200 expression formed the basis of our previous reports that a soluble form of CD200 (CD200Fc) was a potent immunosuppressant [3]. Consistent with the hypothesis that increased expression of CD200 in mice immunized with CD86-transfected tumour cells was responsible for the inhibition of alloreactivity seen in Table 1, suppression was abolished by addition of anti-CD200 mAb (see lower half of Table 1). Earlier reports have already documented an immunosuppressive effect of CD200Fc on alloimmune responses [5], production of antibody in mice following immunization with sheep erythrocytes [5] and more recently (Gorczynski, in preparation) on collagen-induced arthritis in mice.

Maximum inhibition of tumour immunity was achieved by concomitant infusion of CD200Fc and CD200r+ cells (F4/80+ macrophages: see Fig. 8). We next investigated the cell type responsible for tumour growth inhibition whose activity was regulated by CD200–CD200r interactions. Our data confirmed previous reports that EL4 growth inhibition was predominantly associated with CD8 immune cells, while immunity to C1498 was a function of both CD4+ and CD8+ cells [27]. For both tumours in BMT models suppression of tumour growth inhibition was maximal following combined treatment with CD200Fc and either anti-T cell MoAb, consistent with the idea that CD200 suppression acts on both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

A number of studies have examined immunity to EL4 or C1498 tumour cells in similar models to those described above [27,33], concluding that CD8+ cells are important in (syngeneic) immunity to each tumour, and CD4+ T cells are also important in immunity to C1498 [27]. Evidence to date suggests that NK cell-mediated killing is not relevant to tumour growth inhibition in BMT mice of the type used above [27]. Other reports have addressed the issue of the relative efficiency of induction of tumour immunity in a number of models following transfection with CD80 or CD86, and also concluded that CD80 may be superior in induction of antitumour immunity [27,34], while CD86 may lead to preferential induction of type-2 cytokines [8]. This is of interest, given the cytokine production profile seen in EL4-CD86 immunized mice (Table 1), which is similar to the profile seen following CD200Fc treatment of allografted mice [3]. EL4-CD86 immunized mice show increased expression of CD200 (Fig. 7), with no evidence for increased resistance to tumour growth (Fig. 2). Resistance is seen in these mice following treatment with anti-CD200 (Fig. 6a). Somewhat better protection from tumour growth is seen using viable tumour cells for immunization, rather than mitomycin-C treated cells as above [27]. Whether this would improve the degree of protection from tumour growth in our model and/or significantly alter the role of CD200–CD200r interactions in its regulation remains to be seen.

There are few studies exploring the manner in which suppression mediated by CD200–CD200r interactions occurs. In a recent study in CD200 KO mice Hoek et al. observed a profound increase in the presence of activated macrophages and/or macrophage-like cells [14], and we and others had previously found that CD200r was expressed on macrophages [13,35]. We also reported that CD200r was present on a subpopulation of T cells, including the majority of activated γδTCR+ cells [13], a result we have recently confirmed by cloning a cDNA for CD200r from such cells (Kai et al., in preparation). γδTCR+ cells may mediate their suppressive function via cytokine production [36], while unpublished data (R.M.G., in preparation) suggests that the CD200r+ macrophage cell population may exert its activity via mechanisms involving the indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) tryptophan catabolism pathway [37]. We suggest that the mechanism by which CD200Fc leads to suppression of tumour growth inhibition in the models described is likely to be a function both of the tumour effector cell population involved (Figs 9, 10) as well as the CD200r cell population implicated in suppression.

In a limited series of studies (not shown) we have used other BMT combinations (B10 congenic mice repopulated with B10.D2, B10.BR or B10.A bone marrow) to show a similar resistance to growth of EL4 or C1498 tumour cells, which is abolished by infusion of CD200Fc. Studies are in progress to examine whether DBA/2 or BALB/c mice can be immunized to resist growth of P815 syngeneic (H2d) tumour cells by P815 cells tranfected with CD80/CD86, and whether this can also be abolished by CD200Fc. Taken together, however, our data are consistent with the hypothesis that the immunomodulation following CD200–CD200r interactions, described initially in a murine allograft model system, is important also in rodent models of tumour immunity. If true in humans, this has potential implications clinically.

Acknowledgments

Supported by Medical Research Council grant to RMG (no. MT-14678).

References

- 1.Gorczynski RM, Holmes W. Specific manipulation of immunity to skin grafts bearing multiple minor histocompatibility differences. Immunol Lett. 1991;27:163–72. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(91)90145-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorczynski RM, Chen Z, Chung S, et al. Prolongation of rat small bowel or renal allograft survival by pretransplant transfusion and/or by varying the route of allograft venous drainage. Transplantation. 1994;58:816–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gorczynski RM, Chen Z, Fu XM, Zeng H. Increased expression of the novel molecule Ox-2 is involved in prolongation of murine renal allograft survival. Transplantation. 1998;65:1106–14. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199804270-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barclay AN. Different reticular elements in rat lymphoid tissue identified by localization of Ia, Thy-1 and MRC OX-2 antigens. Immunology. 1981;44:727–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorczynski RM, Cattral MS, Chen ZG, et al. An immunoadhesin incorporating the molecule OX-2 is a potent immunosuppressant that prolongs allo- and xenograft survival. J Immunol. 1999;163:1654–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorczynski L, Chen Z, Hu J, Kai G, Ramakrishna V, Gorczynski RM. Evidence that an OX-2 positive cell can inhibit the stimulation of type-1 cytokine production by bone-marrow-derived B7-1 (and B7-2) positive dendritic cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:774–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hancock WW, Sayegh MH, Zheng XG, Peach R, Linsley PS, Turka LA. Costimulatory function and expression of CD40 ligand, CD80, and CD86 in vascularized murine cardiac allograft rejection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13967–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13967. 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freeman GJ, Boussiotis VA, Anumanthan A, et al. B7-1 and B7-2 do not deliver identical costimulatory signals, since B7-2 but not B7-1 preferentially costimulates the initial production of IL-4. Immunity. 1995;2:523–32. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuchroo VK, Das MP, Brown JA, et al. B7-1 and B7-2 costimulatory molecules activate differentially the Th1/Th2 developmental pathways: application to autoimmune disease therapy. Cell. 1995;80:707–18. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90349-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emtage PCR, Wan YH, Bramson JL, Graham FL, Gauldie J. A double recombinant adenovirus expressing the costimulatory molecule B7-1 (murine) and human IL-2 induces complete tumor regression in a murine breast adenocarcinoma model. J Immunol. 1998;160:2531–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Imro MA, Dellabona P, Manici S, et al. Human melanoma cells transfected with the B7-2 co-stimulatory molecule induce tumor-specific CD8 (+) cytotoxic T lymphocytes in vitro. Hum Gene Ther. 1998;9:1335–44. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.9-1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osman GE, Cheunsuk S, Allen SE, et al. Expression of a type II collagen-specific TCR transgene accelerates the onset of arthritis in mice. Int Immunol. 1998;10:1613–22. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.11.1613. 10.1093/intimm/10.11.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gorczynski RM, Yu K, Clark D. Receptor engagement on cells expressing a ligand for the tolerance- inducing molecule OX2 induces an immunoregulatory population that inhibits alloreactivity in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2000;165:4854–60. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.4854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoek RM, Ruuls SR, Murphy CA, et al. Down-regulation of the macrophage lineage through interaction with OX2 (CD200) Science. 2000;290:1768–71. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Theobald M, Ruppert T, Kuckelkorn U, et al. The sequence alteration associated with a mutational hotspot in p53 protects cells from lysis by cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific for a flanking peptide epitope. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1017–28. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.6.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armstrong TD, Pulaski BA, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Tumor antigen presentation: changing the rules. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1998;46:70–4. doi: 10.1007/s002620050463. 10.1007/s002620050463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fischer WH, Straten PT, Terheyden P, Becker JC. Function and dysfunction of CD4 (+) T cells in the immune response to melanoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1999;48:363–70. doi: 10.1007/s002620050587. 10.1007/s002620050587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flo J, Tisminetzky S, Baralle F. Modulation of the immune response to DNA vaccine by co-delivery of costimulatory molecules. Immunology. 2000;100:259–67. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00041.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim TS, Chung SW, Hwang SY. Augmentation of antitumor immunity by genetically engineered fibroblast cells to express both B7.1 and interleukin-7. Vaccine. 2000;18:2886–94. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00061-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heiser A, Dahm P, Yancey DR, et al. Human dendritic cells transfected with RNA encoding prostate-specific antigen stimulate prostate-specific CTL responses in vitro. J Immunol. 2000;164:5508–14. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.10.5508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lord EM, Frelinger JG. Tumor immunotherapy: cytokines and antigen presentation. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1998;46:75–81. doi: 10.1007/s002620050464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esche C, Lokshin A, Shurin GV, et al. Tumor's other immune targets: dendritic cells. J Leukocyte Biol. 1999;66:336–44. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.2.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brady MS, Lee F, Eckels DD, Ree SY, Latouche JB, Lee JS. Restoration of alloreactivity of melanoma by transduction with B7.1. J Immunother. 2000;23:353–61. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200005000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jung D, Hilmes C, Knuth A, Jaeger E, Huber C, Seliger B. Gene transfer of the co-stimulatory molecules B7-1 and B7-2 enhances the immunogenicity of human renal cell carcinoma to a different extent. Scand J Immunol. 1999;50:242–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1999.00588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freund YR, Mirsalis JC, Fairchild DG, et al. Vaccination with a recombinant vaccinia vaccine containing the B7-1 co-stimulatory molecule causes no significant toxicity and enhances T cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Int J Cancer. 2000;85:508–17. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000215)85:4<508::aid-ijc11>3.0.co;2-d. 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000215)85:4<508::aid-ijc11>3.3.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin-Fontecha A, Moro M, Crosti MC, Veglia F, Casorati G, Dellabona P. Vaccination with mouse mammary adenocarcinoma cells coexpressing B7-1 (CD80) and B7-2 (CD86) discloses the dominant effect of B7-1 in the induction of antitumor immunity. J Immunol. 2000;164:698–704. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blazar BR, Taylor PA, Boyer MW, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Allison JP, Vallera DA. CD28/B7 interactions are required for sustaining the graft-versus-leukemia effect of delayed post-bone marrow transplantation splenocyte infusion in murine recipients of myeloid or lymphoid leukemia cells. J Immunol. 1997;159:3460–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ragheb R, Abrahams S, Beecroft R, et al. Preparation and functional properties of monoclonal antibodies to human, mouse and rat OX-2. Immunol Lett. 1999;68:311–5. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(99)00060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gorczynski RM. Transplant tolerance modifying antibody to CD, 200 receptor (CD200r) but not CD, 200 alters cytokine production profile from stimulated macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 2001;100:1–6. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200108)31:8<2331::aid-immu2331>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Imamura M, Hashino S, Tanaka J. Graft-versus-leukemia effect and its clinical implications. Leuk Lymphoma. 1996;23:477–92. doi: 10.3109/10428199609054857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blazar BR, Taylor PA, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Sharpe AH, Vallera DA. Opposing roles of CD28 : B7 and CTLA-4 : B7 pathways in regulating in vivo alloresponses in murine recipients of MHC disparate T cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:6368–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Champlin R, Khouri I, Kornblau S, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic transplantation as adoptive immunotherapy − induction of graft-versus-malignancy as primary therapy. Hematol Oncol Clin N Am. 1999;13:1041+. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boyer MW, Orchard PJ, Gorden K, Andersen PM, McIvor RS, Blazar BR. Dependency upon intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM) recognition and local IL-2 provision in generation of an in vivo CD8+ T cell immune response to murine myeloid leukemia. Blood. 1995;85:2498–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen L, McGowan P, Ashe S, Johnston J, Li Y, Hellstrom KE, Hellstrom KE. Tumor immunogenicity determines the effect of B7 co-stimulation on T-cell mediated tumor immunity. J Exp Med. 1994;179:523–30. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wright GJ, Puklavec MJ, Hoek RM, Sedgewick JD, Brown MH, Barclay AN. Lymphoid/neuronal cell surface OX2 glycoprotein recognizes a novel receptor on macrophages implicated in the control of their function. Immunity. 2000;13:233–42. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gorczynski RM, Cohen Z, Leung Y, Chen Z. gamma delta TCR (+) hybridomas derived from mice preimmunized via the portal vein adoptively transfer increased skin allograft survival in vivo. J Immunol. 1996;157:574–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mellor AL, Munn DH. Tryptophan catabolism and T-cell tolerance: immunosuppression by starvation? Immunol Today. 1999;20:469–73. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(99)01520-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]