Abstract

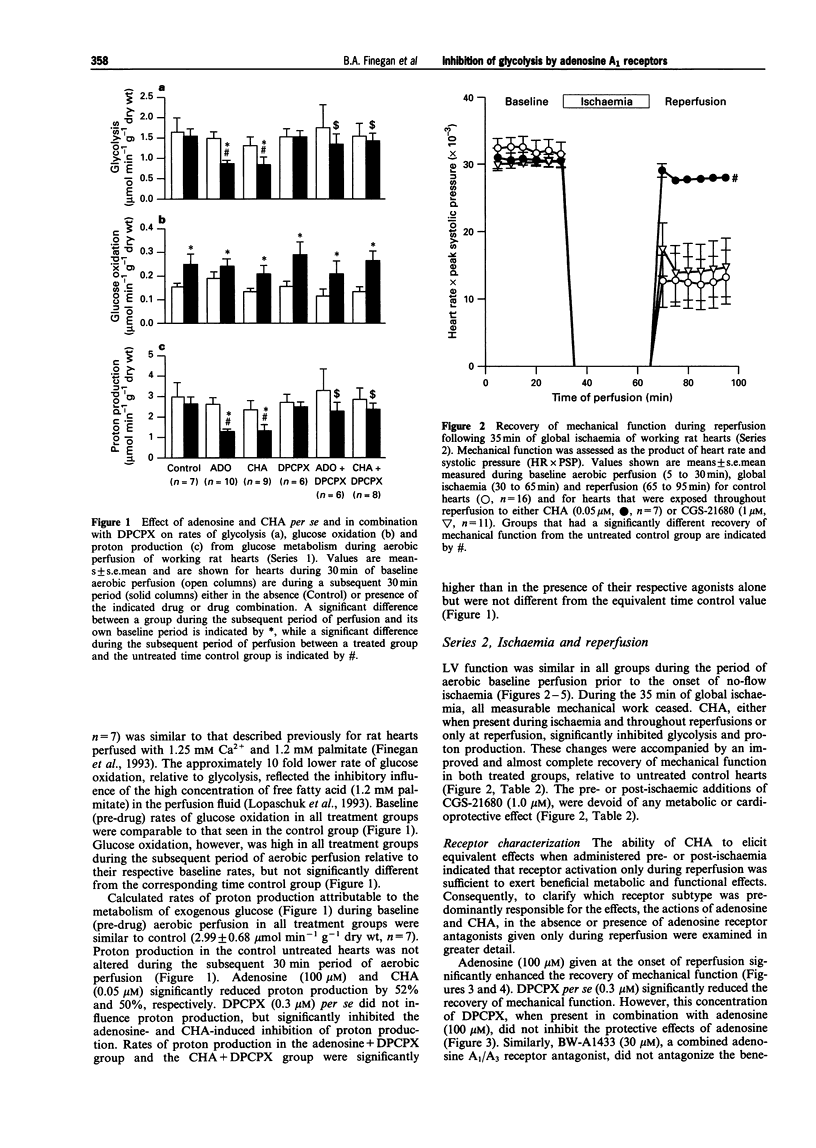

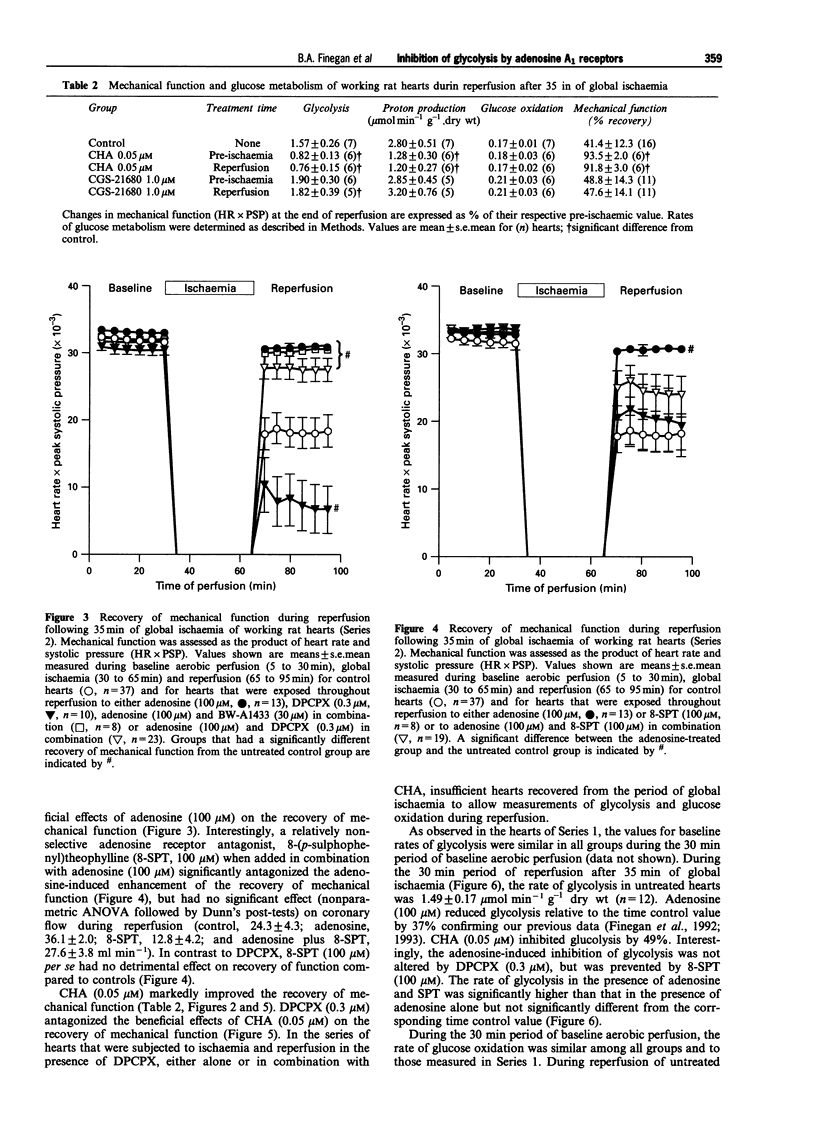

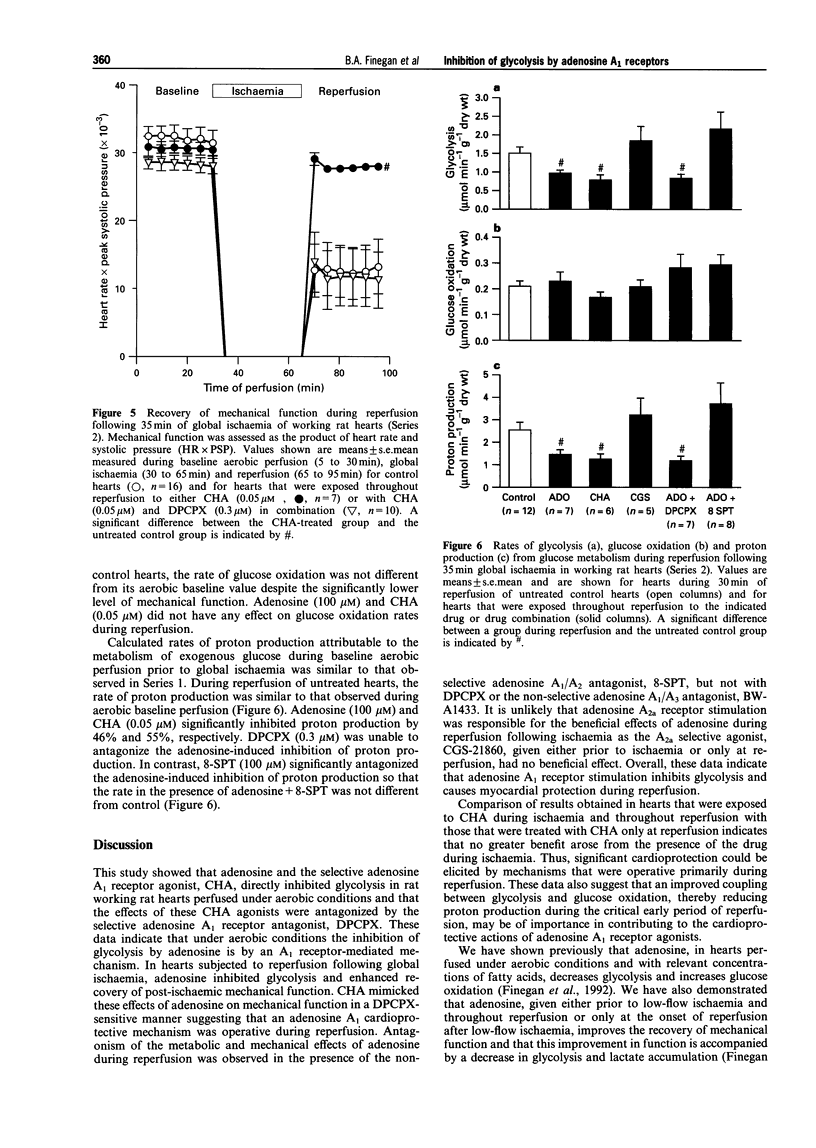

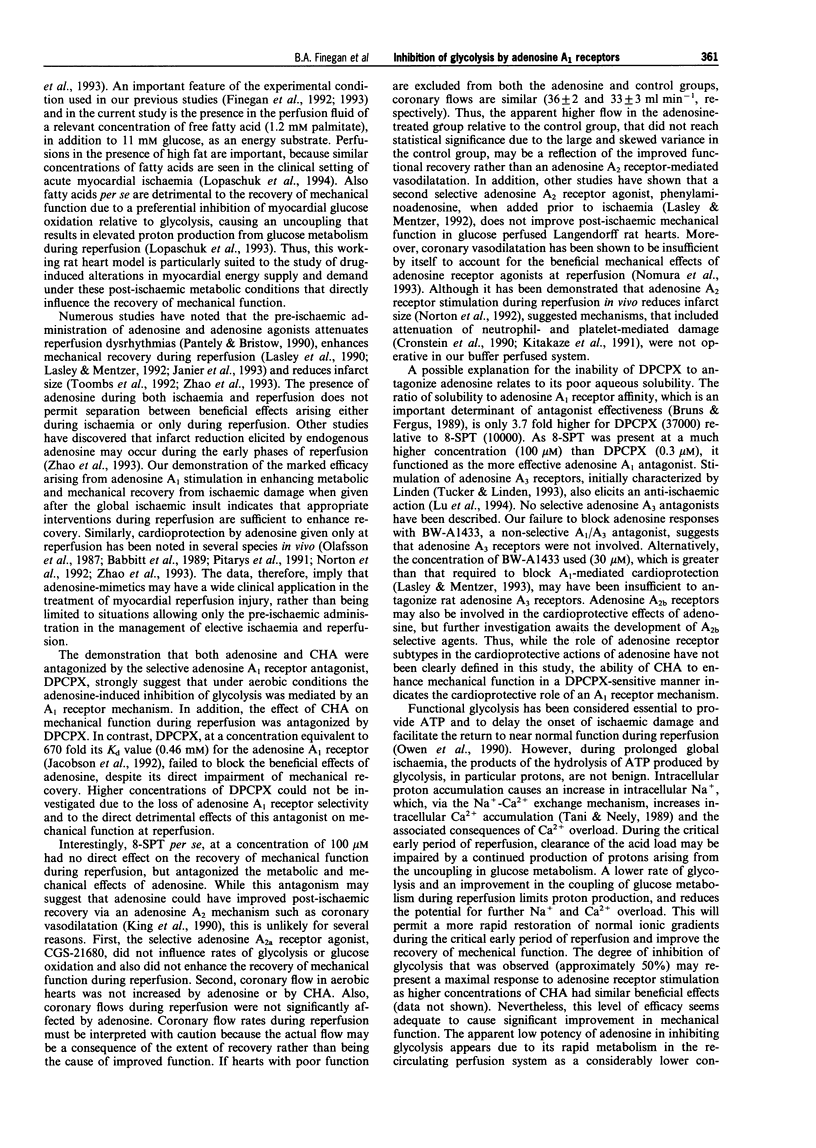

1. This study examined effects of adenosine and selective adenosine A1 and A2 receptor agonists on glucose metabolism in rat isolated working hearts perfused under aerobic conditions and during reperfusion after 35 min of global no-flow ischaemia. 2. Hearts were perfused with a modified Krebs-Henseleit buffer containing 1.25 mM Ca2+, 11 mM glucose, 1.2 mM palmitate and insulin (100 muu ml-1), and paced at 280 beats min-1. Rates of glycolysis and glucose oxidation were measured from the quantitative production of 3H2O and 14CO2, respectively, from [5-3H/U-14C]-glucose. 3. Under aerobic conditions, adenosine (100 microM) and the adenosine A1 receptor agonist, N6-cyclohexyladenosine (CHA, 0.05 microM), inhibited glycolysis but had no effect on either glucose oxidation or mechanical function (as assessed by heart rate systolic pressure product). The improved coupling of glycolysis to glucose oxidation reduced the calculated rate of proton production from glucose metabolism. The adenosine A1 receptor antagonist, 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine (DPCPX 0.3 microM) did not alter glycolysis or glucose oxidation per se but completely antagonized the adenosine- and CHA-induced inhibition of glycolysis and proton production. 4. During aerobic reperfusion following ischaemia, CHA (0.05 microM) again inhibited glycolysis and proton production from glucose metabolism and had no effect on glucose oxidation. CHA also significantly enhanced the recovery of mechanical function. In contrast, the selective adenosine A2a receptor agonist, CGS-21680 (1.0 microM), exerted no metabolic or mechanical effects. Similar profiles of action were seen if these agonists were present during ischaemia and throughout reperfusion or when they were present only during reperfusion. 5. DPCPX (0.3 microM), added at reperfusion, antagonized the CHA-induced improvement in mechanical function. It also significantly depressed the recovery of mechanical function per se during reperfusion. Both the metabolic and mechanical effects of adenosine (100 microM) were antagonized by the nonselective A1/A2 antagonist, 8-sulphophenyltheophylline (100 microM). 6. These data demonstrate that inhibition of glycolysis and improved recovery of mechanical function during reperfusion of rat isolated hearts are mediated by an adenosine A1 receptor mechanism. Improved coupling of glycolysis and glucose oxidation during reperfusion may contribute to the enhanced recovery of mechanical function by decreasing proton production from glucose metabolism and the potential for intracellular Ca2+ accumulation, which if not corrected leads to mechanical dysfunction of the postischaemic myocardium.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Angello D. A., Berne R. M., Coddington N. M. Adenosine and insulin mediate glucose uptake in normoxic rat hearts by different mechanisms. Am J Physiol. 1993 Sep;265(3 Pt 2):H880–H885. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.265.3.H880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babbitt D. G., Virmani R., Forman M. B. Intracoronary adenosine administered after reperfusion limits vascular injury after prolonged ischemia in the canine model. Circulation. 1989 Nov;80(5):1388–1399. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.5.1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruns R. F., Fergus J. H. Solubilities of adenosine antagonists determined by radioreceptor assay. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1989 Sep;41(9):590–594. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1989.tb06537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collis M. G. The vasodilator role of adenosine. Pharmacol Ther. 1989;41(1-2):143–162. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(89)90104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronstein B. N., Daguma L., Nichols D., Hutchison A. J., Williams M. The adenosine/neutrophil paradox resolved: human neutrophils possess both A1 and A2 receptors that promote chemotaxis and inhibit O2 generation, respectively. J Clin Invest. 1990 Apr;85(4):1150–1157. doi: 10.1172/JCI114547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronstein B. N., Levin R. I., Belanoff J., Weissmann G., Hirschhorn R. Adenosine: an endogenous inhibitor of neutrophil-mediated injury to endothelial cells. J Clin Invest. 1986 Sep;78(3):760–770. doi: 10.1172/JCI112638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale W. E., Hale C. C., Kim H. D., Rovetto M. J. Myocardial glucose utilization. Failure of adenosine to alter it and inhibition by the adenosine analogue N6-(L-2-phenylisopropyl)adenosine. Circ Res. 1991 Sep;69(3):791–799. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.3.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis S. C., Gevers W., Opie L. H. Protons in ischemia: where do they come from; where do they go to? J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1991 Sep;23(9):1077–1086. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(91)91642-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ely S. W., Berne R. M. Protective effects of adenosine in myocardial ischemia. Circulation. 1992 Mar;85(3):893–904. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.3.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finegan B. A., Clanachan A. S., Coulson C. S., Lopaschuk G. D. Adenosine modification of energy substrate use in isolated hearts perfused with fatty acids. Am J Physiol. 1992 May;262(5 Pt 2):H1501–H1507. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.5.H1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finegan B. A., Lopaschuk G. D., Coulson C. S., Clanachan A. S. Adenosine alters glucose use during ischemia and reperfusion in isolated rat hearts. Circulation. 1993 Mar;87(3):900–908. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.3.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fralix T. A., Murphy E., London R. E., Steenbergen C. Protective effects of adenosine in the perfused rat heart: changes in metabolism and intracellular ion homeostasis. Am J Physiol. 1993 Apr;264(4 Pt 1):C986–C994. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.4.C986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover G. J. Protective effects of ATP sensitive potassium channel openers in models of myocardial ischaemia. Cardiovasc Res. 1994 Jun;28(6):778–782. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.6.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson K. A., van Galen P. J., Williams M. Adenosine receptors: pharmacology, structure-activity relationships, and therapeutic potential. J Med Chem. 1992 Feb 7;35(3):407–422. doi: 10.1021/jm00081a001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janier M. F., Vanoverschelde J. L., Bergmann S. R. Adenosine protects ischemic and reperfused myocardium by receptor-mediated mechanisms. Am J Physiol. 1993 Jan;264(1 Pt 2):H163–H170. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.1.H163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King A. D., Milavec-Krizman M., Müller-Schweinitzer E. Characterization of the adenosine receptor in porcine coronary arteries. Br J Pharmacol. 1990 Jul;100(3):483–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb15833.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch G. E., Codina J., Birnbaumer L., Brown A. M. Coupling of ATP-sensitive K+ channels to A1 receptors by G proteins in rat ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1990 Sep;259(3 Pt 2):H820–H826. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.3.H820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitakaze M., Hori M., Sato H., Takashima S., Inoue M., Kitabatake A., Kamada T. Endogenous adenosine inhibits platelet aggregation during myocardial ischemia in dogs. Circ Res. 1991 Nov;69(5):1402–1408. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.5.1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasley R. D., Mentzer R. M., Jr Adenosine improves recovery of postischemic myocardial function via an adenosine A1 receptor mechanism. Am J Physiol. 1992 Nov;263(5 Pt 2):H1460–H1465. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.5.H1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasley R. D., Mentzer R. M., Jr Adenosine increases lactate release and delays onset of contracture during global low flow ischaemia. Cardiovasc Res. 1993 Jan;27(1):96–101. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasley R. D., Rhee J. W., Van Wylen D. G., Mentzer R. M., Jr Adenosine A1 receptor mediated protection of the globally ischemic isolated rat heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1990 Jan;22(1):39–47. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(90)90970-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G. S., Richards S. C., Olsson R. A., Mullane K., Walsh R. S., Downey J. M. Evidence that the adenosine A3 receptor may mediate the protection afforded by preconditioning in the isolated rabbit heart. Cardiovasc Res. 1994 Jul;28(7):1057–1061. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.7.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopaschuk G. D., Collins-Nakai R., Olley P. M., Montague T. J., McNeil G., Gayle M., Penkoske P., Finegan B. A. Plasma fatty acid levels in infants and adults after myocardial ischemia. Am Heart J. 1994 Jul;128(1):61–67. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(94)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopaschuk G. D., Wambolt R. B., Barr R. L. An imbalance between glycolysis and glucose oxidation is a possible explanation for the detrimental effects of high levels of fatty acids during aerobic reperfusion of ischemic hearts. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993 Jan;264(1):135–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens D., Lohse M. J., Rauch B., Schwabe U. Pharmacological characterization of A1 adenosine receptors in isolated rat ventricular myocytes. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1987 Sep;336(3):342–348. doi: 10.1007/BF00172688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullane K. Myocardial preconditioning. Part of the adenosine revival. Circulation. 1992 Feb;85(2):845–847. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.2.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton E. D., Jackson E. K., Turner M. B., Virmani R., Forman M. B. The effects of intravenous infusions of selective adenosine A1-receptor and A2-receptor agonists on myocardial reperfusion injury. Am Heart J. 1992 Feb;123(2):332–338. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(92)90643-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olafsson B., Forman M. B., Puett D. W., Pou A., Cates C. U., Friesinger G. C., Virmani R. Reduction of reperfusion injury in the canine preparation by intracoronary adenosine: importance of the endothelium and the no-reflow phenomenon. Circulation. 1987 Nov;76(5):1135–1145. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.76.5.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen P., Dennis S., Opie L. H. Glucose flux rate regulates onset of ischemic contracture in globally underperfused rat hearts. Circ Res. 1990 Feb;66(2):344–354. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.2.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantely G. A., Bristow J. D. Adenosine. Renewed interest in an old drug. Circulation. 1990 Nov;82(5):1854–1856. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.5.1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitarys C. J., 2nd, Virmani R., Vildibill H. D., Jr, Jackson E. K., Forman M. B. Reduction of myocardial reperfusion injury by intravenous adenosine administered during the early reperfusion period. Circulation. 1991 Jan;83(1):237–247. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.1.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardt G., Waas W., Kranzhöfer R., Mayer E., Schömig A. Adenosine inhibits exocytotic release of endogenous noradrenaline in rat heart: a protective mechanism in early myocardial ischemia. Circ Res. 1987 Jul;61(1):117–123. doi: 10.1161/01.res.61.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tani M., Neely J. R. Role of intracellular Na+ in Ca2+ overload and depressed recovery of ventricular function of reperfused ischemic rat hearts. Possible involvement of H+-Na+ and Na+-Ca2+ exchange. Circ Res. 1989 Oct;65(4):1045–1056. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.4.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toombs C. F., McGee D. S., Johnston W. E., Vinten-Johansen J. Protection from ischaemic-reperfusion injury with adenosine pretreatment is reversed by inhibition of ATP sensitive potassium channels. Cardiovasc Res. 1993 Apr;27(4):623–629. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.4.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toombs C. F., McGee S., Johnston W. E., Vinten-Johansen J. Myocardial protective effects of adenosine. Infarct size reduction with pretreatment and continued receptor stimulation during ischemia. Circulation. 1992 Sep;86(3):986–994. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.3.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker A. L., Linden J. Cloned receptors and cardiovascular responses to adenosine. Cardiovasc Res. 1993 Jan;27(1):62–67. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt D. A., Edmunds M. C., Rubio R., Berne R. M., Lasley R. D., Mentzer R. M., Jr Adenosine stimulates glycolytic flux in isolated perfused rat hearts by A1-adenosine receptors. Am J Physiol. 1989 Dec;257(6 Pt 2):H1952–H1957. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.6.H1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z. Q., McGee S., Nakanishi K., Toombs C. F., Johnston W. E., Ashar M. S., Vinten-Johansen J. Receptor-mediated cardioprotective effects of endogenous adenosine are exerted primarily during reperfusion after coronary occlusion in the rabbit. Circulation. 1993 Aug;88(2):709–719. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.2.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z. Q., Nakanishi K., McGee D. S., Tan P., Vinten-Johansen J. A1 receptor mediated myocardial infarct size reduction by endogenous adenosine is exerted primarily during ischaemia. Cardiovasc Res. 1994 Feb;28(2):270–279. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]