Abstract

Genetic diversity of the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori in an individual host has been observed; whether this diversity represents diversification of a founding strain or a mixed infection with distinct strain populations is not clear. To examine this issue, we analyzed multiple single-colony isolates from two to four separate stomach biopsies of eight adult and four pediatric patients from a high-incidence Mexican population. Eleven of the 12 patients contained isolates with identical random amplified polymorphic DNA, amplified fragment length polymorphism, and vacA allele molecular footprints, whereas a single adult patient had two distinct profiles. Comparative genomic hybridization using whole-genome microarrays (array CGH) revealed variation in 24 to 67 genes in isolates from patients with similar molecular footprints. The one patient with distinct profiles contained two strain populations differing at 113 gene loci, including the cag pathogenicity island virulence genes. The two strain populations in this single host had different spatial distributions in the stomach and exhibited very limited genetic exchange. The total genetic divergence and pairwise genetic divergence between isolates from adults and isolates from children were not statistically different. We also analyzed isolates obtained 15 and 90 days after experimental infection of humans and found no evidence of genetic divergence, indicating that transmission to a new host does not induce rapid genetic changes in the bacterial population in the human stomach. Our data suggest that humans are infected with a population of closely related strains that vary at a small number of gene loci, that this population of strains may already be present when an infection is acquired, and that even during superinfection genetic exchange among distinct strains is rare.

Stomach colonization by the bacterium Helicobacter pylori is extremely common in humans, and although generally asymptomatic, infection can lead to unwanted outcomes, including peptic ulcers and gastric cancer. The infection rates vary from 20 to 30% in economically developed regions to 80 to 90% in developing regions. The population structure of H. pylori is unusual due to vertical transmission of the bacteria within families, predominantly from parent to child or between children via oral-oral, gastric-oral, or fecal-oral routes (10, 18, 32, 33, 55). No environmental reservoir of the bacteria has been identified. Infection persists chronically without specific antimicrobial intervention, allowing divergence of multiple isolated populations. Molecular finger printing techniques, such as random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD)-PCR, have revealed marked sequence heterogeneity between strains from unrelated individuals (2). The genome-wide extent of sequence diversity has been determined in exquisite detail by whole-genome sequencing of three unrelated clinical isolates, isolates 26695, J99, and HPAG1 (3, 39, 53). The mechanisms by which this diversity is generated and propagated through the population and its impact on both the host and the bacterium are unknown.

There is diversity within the bacterial population in single infected hosts. Molecular fingerprinting studies using RAPD (57), amplified fragment length polymorphisms (AFLP) (40), and sequence analysis of virulence-associated or housekeeping genes (20, 46) with multiple single-colony isolates or cultures obtained from separate biopsy samples from single patients revealed that strains isolated from single patients were closely related but that there were subtle differences in the majority of patients. The variants have even been referred to as quasi-species of a single strain (35). A smaller number of patients (10 to 20%) have shown evidence of a mixed infection, defined as clones from a single patient that are more similar to isolates from other patients than they are to each other. Interestingly, strains isolated at the same time or after 6 months to 10 years have shown similar divergence (11, 35, 40, 41, 46, 57). Thus, while populations may diverge within the host, divergence appears to occur slowly.

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) has been particularly useful for examining the mechanisms contributing to variation within the H. pylori population. Analysis of homoplasy using individual gene sequences from a large collection of isolates revealed that recombination between H. pylori strains is more frequent than recombination between strains of most species, so that gene loci on the single bacterial chromosome are in linkage equilibrium (48). Only isolates obtained from related family members showed signs of being clonal. A subsequent study in which the workers compared gene sequences at 10 loci from participants in antibiotic eradication trials and in which paired isolates were obtained at a mean interval of 1.8 years indicated that recombination, not mutation, explained most of the variation observed. Furthermore, strains obtained from the same individual differed in 3% of the genome (20). One disadvantage of MLST is that it queries only a limited portion of the genome (a fraction of a percent). Interestingly, comparative genomic hybridization using whole-genome microarrays (array CGH) has revealed that the presence of 25% of the genes in the genome of H. pylori strains varies (25, 44), and even within an infected individual the presence of 3% of the genes in isolates can vary (28). Recombination has been proposed to be the mechanism for gene acquisition and loss, although this has been convincingly demonstrated in only a few cases (30, 34, 46). When the recombination events occur remains an open question.

In several studies workers have investigated transmission of H. pylori strains within families (27, 42, 54). These studies suggest that children acquire strains most frequently from their mothers, but they also acquire strains from other family members. Additionally, multiple strain variants and recombinants have been observed in children. This raises the possibility that there is no stringent bottleneck during transmission, meaning that children may be infected with a population of bacteria, possibly from multiple sources. Alternatively, there may be a transmission bottleneck, but strains then diverge by mutation and recombination. Infection of experimental animals has shown that colonization by multiple distinct strains is possible and that strains do not undergo extensive recombination during relatively short times (1, 15, 49, 52). Additionally, serial passage in vitro or long-term infection of mice has not revealed measurable divergence of clones, arguing against the hypothesis that there is a high degree of genomic instability in H. pylori (37).

The aim of the present work was to examine the genetic diversity in the H. pylori populations colonizing the stomachs of single human hosts from a population with a high rate of infection, in both children and adults. We also searched for evidence of de novo genetic diversity generated during experimental transmission of a defined strain to new adult human hosts. Multiple single H. pylori colonies were isolated from different regions of the stomachs of patients and were analyzed by using sequence polymorphisms in the virulence gene vacA, RAPD-PCR, AFLP, and array CGH to quantify differences among isolates at the whole-genome level. For naturally infected adults and children, we observed ubiquitous colonization by an H. pylori population with multiple strain variants defined by genetic diversity in a limited number of genes. Mixed infection by multiple strains, defined by diversity in a much larger number of genes, was less frequent. In the case of mixed infection, we confirmed predicted phenotypic differences among the infecting strains and documented limited recombination between two strains. Consistent with animal infection studies, we obtained no evidence of genetic diversification shortly after experimental infection of adult human volunteers with a homogeneous strain. The presence of multiple related but distinct genotypes, even in children, suggests that multiple genotypes may persist during transmission from human host to human host.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

Four H. pylori-infected children attending the Pediatric Hospital, Centro Medico Nacional, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, in Mexico City were studied. The children presented at the gastroenterology service because of recurrent abdominal pain (median age, 7 years; age range, 5 to 10 years; two males and two females). Eight H. pylori-infected adult patients, recruited in the General Hospital at Centro Medico Nacional, were also studied. Six of these patients had peptic ulcers (median age, 60 years; age range, 28 to 88 years; four males and two females; three patients with duodenal ulcers and three patients with gastric ulcers), and one had nonulcer dyspepsia (age, 38 years; female). All patients had H. pylori infections, as documented by the urea breath test and culture. The project was approved by the ethics committee of the General Hospital of the Centro Medico Nacional, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, Mexico City, Mexico. In all cases patients were informed about the nature of the study and were asked to sign a consent form. Four patients who participated in a human challenge study (patients 101, 103, 104, and 105) have been described previously (24).

H. pylori isolation.

Two biopsies from each site (antrum, corpus, fundus, and incisura angularis in adults and antrum and corpus in children) were taken from each patient. One biopsy from each site was cultured for H. pylori isolation, and the other was fixed and processed for histological analysis. For culture, biopsy samples were homogenized and inoculated onto Trypticase soy agar plates supplemented with 7.5% sheep blood. Cultures were identified by urease, catalase, and oxidase tests and Gram staining.

From the primary growth obtained for each biopsy site, six or seven single colonies were isolated and propagated; growth from single colonies was swept and suspended in a saline solution for DNA isolation as previously described (5), and the preparations were stored at −20°C until they were tested.

Reference strains.

The following strains were used as controls: 60190 (= ATCC 49503) (cag pathogenicity island positive [PAI+], vacA s1a/m1), Tx30a (= ATCC 51932) (cag PAI−, vacA s2/m2), and 84-183 (= ATCC 53726) (cag PAI+, vacA s1b/m1). DNA from control and test strains were included in each PCR assay. For coculture experiments G27 (14) and a PAI mutant derivative constructed by insertion of a Kan-SacB cassette (13) at bp 122 of the cag2 open reading frame (ORF) were used. For array CGH studies of isolates obtained after experimental challenge, Baylor challenge strain BCS 100 (= ATCC BAA-945) was used (24).

PCR genotyping for vacA and cagA.

The method used for vacA signal sequence and mid-region PCR typing was a slight modification of the method described by Atherton et al. (6). The PCR conditions were 35 cycles of 94°C for 0.5 min, 56°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1.5 min and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. For cagA typing, two sets of primers were used (primers F1 and B1 and primers B7628 and B7629) (23).

RAPD-PCR fingerprinting.

RAPD fingerprinting was performed as previously described (51), using the 1281 and 1254 oligonucleotides for priming. The PCR products were electrophoresed in 2.5% agarose gels, and the resulting DNA patterns were analyzed with an automatic image analyzer (Syngene, United Kingdom).

AFLP analysis.

AFLP analysis was performed as previously described (21). Briefly, 5 μg of H. pylori DNA was digested with 20 U of HindIII, adapter oligonucleotides ADH1 and ADH2 were ligated to the DNA fragments, and fragments were PCR amplified for 33 cycles using primer H1-1. Products were separated on a 2% agarose gel.

Array CGH.

The microarray design and hybridization conditions used have been described previously (44). Each strain was examined by performing a two-color competitive hybridization with a reference sample. For the Mexican pediatric and adult patient isolates and strain BCS 100, the reference preparation used was an equal molar mixture of sequenced strains 26695 and J99, which were used to design the probes on the microarray (44). For the isolates obtained in the human infection experiment, the reference sample was the strain administered to the patients (BCS 100). Each isolate was analyzed on at least two microarrays, which generated four potential data points for each gene. Data points were excluded due to low signals, slide abnormalities, and a regression correlation of pixel intensities in each channel of <0.6. Only the genes for which at least two (and up to ten) measurements were obtained were analyzed. Data were normalized using the default-computed normalization of the Stanford Microarray Database (22), and the mean of the log2(red channel normalized net intensity/green channel net intensity) (log2RAT2N) was computed. Data were also not included if the standard deviation of the log2RAT2N was greater than 1.0. For analysis of the Mexican isolates and BCS 100 a constant cutoff for absence of a gene was defined as a log2RAT2N value of −1.0 based on test hybridizations (28). Data were simplified into a binary score, analyzed with CLUSTER (http://bonsai.ims.u-tokyo.ac.jp/∼mdehoon/software/cluster/) (16), and displayed with TREEVIEW (http://rana.lbl.gov/EisenSoftware.htm) (19). For the human challenge experiments, the GACK program (http://falkow.stanford.edu/whatwedo/software/) (31) was used to determine the divergence of genes from the genes of the starting strain because the BCS 100 strain used as the reference did not hybridize optimally with array probes in order to look for gene loss more stringently. Only genes present in BCS 100 were considered because a low signal in the reference channel resulted in misleading log ratio data. The complete data sets are available in Tables S1 and S4 in the supplemental material. The raw data are available at http://genome-www5.stanford.edu.

PCR confirmation of microarray results.

Fifty nanograms of genomic DNA of each isolate was used in a PCR mixture containing 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates and 0.2 mM primer DNA. The conditions used for amplification were one cycle of 1 min at 94°C, 30 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 48 to 56°C, and 2 to 4 min at 72°C, and one cycle of 5 min at 72°C. The primer sequences are shown in Table S2 in the supplemental material. In some cases, PCR products were sequenced using Big Dye sequencing reagents (ABI) and primers used for amplification by the FHCRC genomic resource. Sequences were aligned using the Sequencher software (version 4.5) to elucidate the genomic sequences between conserved ORFs. These sequences were compared to the sequences of reference strain ORFs using the NCBI BLAST server (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/) and were aligned using MAFFT 5.8 (online version; http://align.bmr.kyushu-u.ac.jp/mafft/online/server/) to generate a ClustalW-like output.

Coculture experiments.

The human gastric adenocarcinoma cell line AGS was maintained in the presence of 10% CO2 in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cells in 24-well plates. H. pylori strains were grown at 37°C overnight in 90% brucella broth supplemented with 10% FBS, harvested, and resuspended in DB medium (81% Dulbecco modified Eagle medium, 9% brucella broth, 10% FBS) at a density of 2 × 106 bacteria/ml, and 1 ml was used to inoculate each well. At each time, supernatant was harvested, centrifuged, and frozen for interleukin-8 (IL-8) analysis (Biotrak enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay system [Amersham Biosciences, United States]). To detect phosphorylated and total CagA, the remaining cells and bacteria in each well were lysed with 100 μl of 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis sample buffer (0.25 M Tris-Cl [pH 6.8], 4% glycerol, 4% SDS, 0.001% bromphenol blue, 2% 2-mercaptoethanol). Samples were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. To visualize phosphorylated CagA, membranes were probed with anti-phosphotyrosine PY20 anticorpus (BD Transduction Laboratories, United States), followed by a 1:10,000 dilution of goat anti-mouse-horseradish peroxidase (Amersham Biosciences). Immune reactive proteins were visualized using the ECL Plus Western blot detection reagent (Amersham Biosciences). To measure CagA, the same membranes were probed with a 1:10,000 dilution of anti-CagA polyclonal anticorpus pAs (4), followed by a 1:10,000 dilution of goat anti-rabbit-horseradish peroxidase (Amersham Biosciences), and were visualized using ECL Plus.

Statistics.

The presence of the clade 1 genotype in the antrum compared with the rest of the stomach was evaluated with Fisher's exact test, and the extent of gene variation between children and adults was evaluated by the Mann-Whitney test using the InStat software (version 3.0; GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences obtained in this study have been deposited in GenBank with accession numbers EF521122 to EF521132.

RESULTS

Molecular fingerprinting revealed limited diversity in chronically infected adults and children in Mexico.

H. pylori isolates exhibit genetic variability within single hosts. We examined H. pylori genetic diversity in a Mexican population with a high incidence of infection. To extensively map the H. pylori population in the stomach, we obtained multiple single-colony isolates from biopsy specimens taken from four different sites in the stomachs of eight adults (median age, 60 years). We studied 227 H. pylori single colonies, a mean of 28 colonies per patient, and seven colonies from each of the four regions of the stomach (fundus, corpus, incisura angularis, and antrum). We also obtained single-colony isolates from two biopsy sites (corpus and antrum) in four children (median age, 7 years) to investigate differences in genetic diversity between adults and children. For the pediatric isolates, we studied two single colonies from each biopsy site.

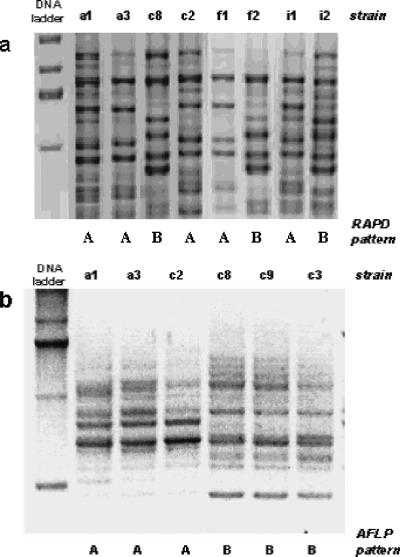

All H. pylori colonies isolated from the four stomach regions of seven of the eight adult patients and all pediatric patients had the same RAPD and AFLP fingerprints, suggesting that each patient was colonized by a single strain. In contrast, colonies from one adult patient (patient 259) had two different RAPD patterns, which were designated RAPD patterns A and B (Fig. 1). Strains with RAPD pattern A had the same AFLP pattern (AFLP pattern A), while strains with RAPD pattern B had AFLP pattern B (Fig. 1 and Table 1).

FIG. 1.

H. pylori fingerprints of multiple single colonies isolated from the antrum (isolates a1 and a3), corpus (isolates c2, c3, c8, and c9), fundus (isolates f1 and f2), and incisura angularis (isolates i1 and i2) of gastric biopsies from patient 259. (a) RAPD patterns of isolates from the four regions, showing two different patterns, patterns A and B, as determined with primer 1254. (b) AFLP patterns of isolates from patient 259 with RAPD patterns A and B. Two AFLP patterns were observed, which coincided with the two RAPD patterns.

TABLE 1.

Genetic characterization of H. pylori isolates from patient 259

| Region | No. of isolates | RAPD pattern | AFLP pattern | Microarray clade | vacA allele | Presence of cagPAI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antrum | 5 | A | A | 1 | s1m1 | + |

| Corpus | 1 | A | A | 1 | s1m1 | + |

| 3 | B | B | 2 | s2m2 | − | |

| Fundus | 2 | A | A | 1 | s1m1 | + |

| 2 | B | B | 2 | s2m2 | − | |

| Incisura angularis | 1 | A | A | 1 | s1m1 | + |

| 2 | B | B | 2 | s2m2 | − |

We characterized two virulence-associated loci (vacA and cagA) in each isolate using PCR. One adult patient (patient 249) had identical RAPD and AFLP patterns but had distinct vacA genotypes, which were characterized in a separate study (7). The remaining patients with uniform AFLP patterns had the same vacA and cagA genotypes; isolates from three patients had the vacA s1m1 allele associated with high-level toxin expression and were cagA+, whereas isolates from the other three patients had the vacA s2m2 allele associated with a lower level of toxin expression and were ΔcagA. Three of the pediatric isolates were vacA s1m1 cagA+, and one was vacA s2m2 ΔcagA. In the case of patient 259, who appeared to have two distinct strain populations, all the colonies in clade 1 (RAPD pattern A, AFLP pattern A) contained the vacA s1m1 allele and were cagA+. All the isolates in clade 2 (RAPD pattern B, AFLP pattern B) were vacA s2m2 ΔcagA (Table 1).

Microarray genotyping identified previously recognized and new variable genes.

To further explore the diversity of isolates in single patients, we used array CGH to compare the gene content of each isolate with the gene contents of two unrelated reference strains which have been fully sequenced (strains 26695 and J99). For this analysis we chose three adult patients with different strain populations; one of them appeared to have a homogeneous strain population, one of them appeared to have a mixed infection based on the appearance of two different RAPD profiles, and one of them appeared to have a mixed infection based on the presence of different vacA alleles. We analyzed 36 colonies and included isolates from all four biopsy sites. In addition, we analyzed two antral and two corpus isolates for each of the four pediatric patients (except patient 323, for which only a single corpus isolate was available for analysis) and examined a total of 51 clones. Of the 1,675 genes analyzed, 18 were not reliably measured and 7 were absent in all isolates, while 1,285 (78%) were uniformly present. The remaining 365 genes were differentially present or absent in one or more strains. These variable genes included 309 genes previously documented to be variable based on genomic microarray profiling of clinical isolates obtained from diverse populations worldwide (25, 29, 44). We identified 15 additional genes not previously documented to be variable in strains that were missing in a least two isolates from one to five patients (Table 2). Conversely, 165 genes found to be dispensable in a subset of strains previously were universally present in this collection of isolates (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). The complete data set for the 51 isolates is shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material, and raw microarray hybridization data are available from the Stanford Microarray Database (http://genome-www5.stanford.edu).

TABLE 2.

New genes that are variable in the strains in the Mexican patient population

| Locusa | Desciptionb | Frequency (%)c | No. of patients |

|---|---|---|---|

| HP0119 | 77 | 1 | |

| HP0174 | 92 | 1 | |

| HP0327 | Flagellar protein G | 94 | 3 |

| HP0350 | 92 | 2 | |

| HP0479 | Nonfunctional type II restriction endonuclease | 82 | 1 |

| HP0599 | Hemolysin secretion protein precursor, methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein | 98 | 2 |

| HP0664 | 96 | 1 | |

| HP0719 | 96 | 1 | |

| HP0820 | 94 | 1 | |

| HP0823 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 94 | 1 |

| HP0938 | 96 | 2 | |

| HP1076 | 98 | 1 | |

| HP1257 | Orotate phosphoribosyltransferase | 96 | 1 |

| HP1392 | Fibronectin/fibrinogen-binding protein | 90 | 2 |

| HP1511 | 90 | 5 |

Locus designation according to the 26695 genome sequence (53).

Annotation according to The Institute for Genomic Research Comprehensive Microbial Database (http://cmr.tigr.org/tigr-scripts/CMR/CmrHomePage.cgi) and the PyloriGene database (http://genolist.pasteur.fr/PyloriGene/genome.cgi) (9).

Frequency at which the gene is present in the 51 isolates tested, corrected for clones for which data were not available.

Clustering based on gene content provided evidence of strain variants and mixed infections with distinct strains.

We determined if our array CGH results differentiated strains like the RAPD analysis using cluster analysis. The 365 genes whose presence varied among the isolates were used to perform an unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis of the isolates based on gene content. As shown in Fig. 2, all of the colonies studied from the patients with isolates having the same RAPD and AFLP fingerprints (adult patients 249 and 251 and pediatric patients 291, 323, 612, and 653) grouped together in distinct nodes on the dendrogram. Interestingly, the 16 isolates from the patient with multiple RAPD and AFLP patterns (patient 259) fell into two separate groups that we designated clades 1 and 2. The two clades exhibit equal divergence from each other and from the isolates from the other patients. The nine isolates with RAPD pattern A and AFLP pattern A were in clade 1, whereas the seven isolates with RAPD pattern B and AFLP pattern B were in clade 2 (Table 1 and Fig. 2), providing further evidence that this patient harbored separate strain populations. In addition, the isolates from patient 249, which had different vacA types, all clustered together based on their gene complements, which is consistent with the RAPD profile data.

FIG. 2.

Clustering of single-colony isolates based on gene content: dendrogram showing the output of hierarchical clustering of single-colony isolates from two patients based on the presence or absence of 365 genes whose presence varied in the strains based on microarray hybridization. Each isolate is identified by a three-digit number indicating the patient source, followed by a letter indicating the biopsy site (a, antrum; c, corpus; f, fundus; i, incisura angularis) and a number indicating the single-colony number from the initial isolation. Isolates from all but one patient grouped together. Isolates from patient 259 fell into two separate clusters that correspond to clade 1 and clade 2 (indicated by brackets). The two patient 259 clusters exhibit equal similarity with the strains from other patients and with each other, as indicated by the distance between nodes, which reflect the Pearson correlation coefficients.

Patient 259 was colonized by two distinct strain populations.

Isolates from all patients showed robust hybridization, indicating gene presence, for 1,359 to 1,545 of the genes on the microarray (Table 3). For strains that clustered together there were 24 to 67 genes whose presence varied in single-colony isolates; however, in patient 259 the presence of 178 genes varied. These genes included 113 genes that perfectly distinguished the two clades by either being present in all isolates in clade 1 and absent in all isolates in clade 2 or vice versa. The vast majority of these genes had no informative homologies. The notable exceptions were the 26 genes of the cag PAI, which has been linked to increased virulence. The clade 1 isolates contained the cag PAI, while the clade 2 isolates did not. The remaining genes included 43 genes that were always present in one clade and variably present in the other, 15 genes that were absent in one clade and variably present in the other, and 7 genes that were variably present in both clades. We independently verified the presence or absence of three genes that were always present in clade 1 and always absent in clade 2 (HP1177 [omp27], HP1243 [babA], and HP0995 [xerD]) and two genes that were always present in clade 2 and always absent in clade 1 (HP1324 and HP0855 [algI]) using gene-specific PCR. For all 16 single-colony isolates the PCR data confirmed the microarray data (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Microarray analysis of gene content of H. pylori isolates

| Patient | Age (yr) | No. of isolates examined | No. of variable genes | Presence of cag PAI | Total no. of genes per isolate | Avg no. of pairwise variable genes (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 249 | 71 | 12 | 67 | + | 1520-1546 | 21 (5) |

| 251 | 88 | 8 | 36 | − | 1454-1496 | 12 (3) |

| 259 | 28 | 16 | 178 | ± | 1444-1513 | |

| 259 (clade 1) | 9 | 36 | + | 1496-1513 | 13 (3) | |

| 259 (clade 2) | 7 | 36 | − | 1444-1475 | 15 (4) | |

| 291 | 7 | 4 | 24 | + | 1505-1513 | 13 (4) |

| 323 | 7 | 4 | 35 | + | 1484-1504 | 19 (9) |

| 612 | 10 | 3 | 36 | + | 1373-1519 | 21 (7) |

| 653 | 5 | 4 | 44 | − | 1476-1487 | 22 (7) |

We examined whether the variable genes in isolates from patient 259 were located together on the chromosome. To examine the physical distribution of the variable genes, we organized the genes in a pseudogene order derived by mapping the observed inversion and translocation breakpoints of the previously published J99 genome sequence onto the observed inversion and translocation breakpoints of the previously published 26695 genome sequence (44). The genes that distinguished the two clades from patient 259 were in blocks consisting of one to nine genes in addition to the 26-gene block of the cag PAI. The largest blocks of genes that varied, besides the genes of the cag PAI, mapped to the plasticity zone, a region with a known high level of diversity containing the majority of strain-specific genes in the sequenced strains (3). In contrast, the genes that varied within each clade were gained or lost in single-gene increments (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

Sequencing across loci that were variable in clades revealed limited genetic exchange among strain populations during mixed infection.

Although most genes that were variably present perfectly distinguished the two clades of patient 259, seven genes mapping to six chromosomal loci appeared to be variably present in both the clade 1 and clade 2 strain populations. The variable hybridization pattern might be explained by genetic exchange between the two strain populations, generating a mosaic pattern of gene presence. In order to test this hypothesis, we designed primers for the flanking universally present genes to amplify across these loci in each isolate. We successfully amplified DNA and sequenced the products from four loci representing five of the seven genes that were variable in the clades (Table 4). For one locus we obtained an amplification product that was the same size for all 16 isolates, and for three loci we obtained clade-specific amplification products; one locus was amplified only from clade 2 isolates, while for the other two loci we obtained products that were two distinct sizes and perfectly correlated with the clades to which the isolates belonged. We sequenced the PCR products for three isolates from each clade (a total of six isolates). In all but one case the sequences in a clade were identical. A comparison of the consensus sequences from the clade 1 and clade 2 isolates revealed numerous single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), as well as large insertions and deletions (Table 4). These findings support our array results showing that strains belonging to the same clade are closely related, while strains belonging to different clades are quite diverse.

TABLE 4.

Analysis of patient 259 variable loci

| Genomic locus | ORF(s) in reference strains

|

Size, highest-homology ORF (% identity) in patient 259

|

Homologues or paralogues of patient 259 isolate genes | Polymorphisms (no. of SNPs, no. of insertions/deletions)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26695 | J99 | HPAG1 | Clade 1a | Clade 2b | Within clade | Betweens clades | ||

| Between HP0160 and HP0162c | HP0161 | No ORF | No ORF | 672 bp, no ORF | 519 bp, no ORF | NAd | 0, 0 | 189, 11 |

| Between JHP0957 and JHP0960 | Locus not present | JHP0958, JHP0959 | Locus not present | No amplification | 1.2 kb, HP1412/HP0423 (58) | HP1412, HP0423, JHP0958-9, JHP1307, HPAG1_1337-8, HPAG1_0970 | 0, 0 | NA |

| Between HP0879 and HP0883 (ruvA)c | HP0880, HP0881 | JHP0813, JHP0814 | HPAG1_0862 | 2.2 kb, HPAG1_0862 (83) | 1.6 kb, JHP1044 (84) | HPAG1_0862, HP0488/HP1116, JHP1044, JHP1041, JHP0440, HPAG1_1054, HPAG1_0464 | 0, 0e | 108, 13 |

| Between HP0961 and HP0963c | HP0962 | JHP0896 | No ORF | 1.2 kb, HPAG1_0946 (77) | 1.2 kb, HPAG1_0946, (82) | HP0896, HP0963, HPAG1_0946 | 0, 0 | 167, 5 |

The clade 1 isolates sequenced were a3, f6, and i8.

The clade 2 isolates sequenced were c3, f4, and i10.

The homologues for the genes in the other sequenced strains are as follows: HP0160/JHP0149/HPAG1_0158, HP0162/JHP0149/HPAG1_0159, HP0160/JHP0149/HPAG1_0158, HP0162/JHP0149/HPAG1_0159, HP0961/JHP0895/HPAG1_0945, and HP0963/JHP0897/HPAG1_0946.

NA, not applicable.

The clade 2 isolate i10 sequence had nine SNPs and three insertions/deletions compared to the other clade 2 sequences in the first 372 bp but was identical to the three clade 1 isolate sequences, suggesting that there was a recombination event.

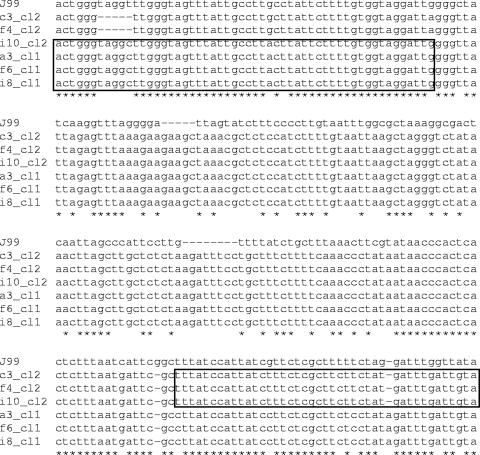

In one case the sequencing data suggested that a recombination event occurred. This recombination event occurred in clade 2 isolate i10 at the HP0879-to-HP0883/ruvA locus. Excluding the i10 isolate, a comparison of 2,176 bp of the consensus sequence for the clade 1 and clade 2 isolates revealed 108 SNPs and 13 insertions or deletions ranging from 1 to 606 bp long. For the first 372 bp the isolate i10 genomic sequence aligned perfectly with the genomic sequences of the three clade 1 isolates (including nine SNPs and three insertions or deletions), while for the remainder of the sequence it was identical to the genomic sequences of the other two clade 2 isolates (Fig. 3). The recombination event affected the amplification of this locus in the i10 clone. While all the clade 1 strains gave a product at 54°C that was 2.2 kb long, only one of the clade 2 isolates (i10) produced a band at this temperature, which was a distinct size (1.6 kb). At 52°C the remaining clade 2 isolates produced an amplification product that was the same size as the i10 product obtained at 54°C. The similarity of the isolate i10 sequence to clade 1 sequences at the 5′ end may explain the fact that this region could be amplified with a higher annealing temperature than the six other clade 2 sequences. At the other three loci analyzed, the isolate i10 sequences were identical to the sequences for the other clade 2 loci for the entire length of the region amplified. Thus, at the four loci sequenced, the isolates appeared to be highly clonal in each clade (no polymorphisms), but the sequences were quite different in the different clades (numerous polymorphisms). Additionally, we found evidence of one recombination event between the two clade populations.

FIG. 3.

Patient 259 clade 2 isolate i10 has a mosaic DNA sequence at the locus spanning JHP0812 to JHP0815/ruvA. The J99 reference strain and three clade 1 and three clade 2 isolate genomic sequences were aligned using MAFFT. Sequences flanking the recombination junction are shown. At the 5′ end of the sequence (box) the i10 sequences match the polymorphisms found in the three clade 1 isolates. At the 3′ end the i10 sequences match the polymorphisms found in the two other clade 2 isolates (box). The intervening region encompasses the crossover point. The asterisks indicate bases conserved in all seven sequences. The J99 reference strain sequence is quite divergent from the patient 259 isolate sequences.

The data for all four of the loci analyzed showed that there was marked genetic diversity among the three reference strains of H. pylori (26695, J99, and HPAG1). The reference strains either had unique ORFs or lacked ORFs at these genomic locations. In all cases the patient 259 isolates had sequences that were highly divergent from the sequences of the corresponding gene spots on the microarray (<82% identity). Thus, it is more likely that the mosaic hybridization pattern observed was caused by poor probe homology than by actual divergence among isolates within each clade. Interestingly, the genomic architecture of the patient 259 isolates at the four loci corresponded to the genomic architecture of at least one of the fully sequenced reference strains, although a predicted ORF often exhibited the highest level of homology with a homologue or paralogue located at a different chromosomal position in the sequenced strains (Table 4). This suggests that the regions selected for analysis, only one of which falls in a previously annotated plasticity zone (JHP0958-JHP0959), may represent hot spots for genomic alterations.

Variation among genes that are variable in strains.

We examined the distribution of variable genes in patients to identify the genes that were variable in the strain populations in individual hosts. Of the 365 genes variably present in our patient population, 171 were differentially present in patients but not in the isolates from a single patient (or in a single clade) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The remaining 196 genes were variably present in one or more patients (or clade). Most of these genes (136 genes) did not have an informative annotation based on the nucleotide sequence. The genes with putative functions included genes involved in DNA uptake, modification, or metabolism (22), genes encoding outer membrane proteins (5), and genes involved in cell envelope biosynthesis or modification (7). Many of the annotated genes belong to multigene families, such as the genes encoding outer membrane proteins. It is possible that these genes can be lost during infection simply due to functional redundancy with other proteins in the cell. Alternatively, there may be selective pressures in the changing host environment that drive the changes observed. The number of genes that varied within a particular host's population ranged from 24 to 67 (Table 3). The average pairwise difference in gene content for the intrahost populations ranged from 12 to 22 genes (Table 3).

We examined whether any genes distinguished adult and pediatric patients. Three of the genes that distinguished patients exhibited a reciprocal relationship in the adult and pediatric patients. A hypothetical gene present in the J99 sequenced strain (JHP0587) and another hypothetical gene present in all three sequenced strains (HP0688/JHP0628/HPAG1_0671) were present in all of the adult isolates and in none of the pediatric isolates. A gene encoding a putative type III restriction modification system methyl transferase (HP1522/JHP1411/HPAG1_1393) that exhibits phase variation (45) was present only in pediatric isolates and not in the isolates from adults. There was no statistical difference in the extents of genetic variation observed in adults and in children when either the total number of variable loci (P = 0.38) or the pairwise difference between isolates (P = 0.34) was considered.

We also examined whether gene content varied by anatomical site within the stomach. Clustering based on all the variable genes did not indicate that there was a closer relationship among strains from the same biopsy site. Although isolates from the same biopsy site sometimes grouped together, they often did not (Fig. 2). For example, for patient 323 isolates a2 and c5 from the antrum and corpus, respectively, had gene complements that were more similar to each other than to the gene complement of the other isolate from the same anatomical location. The same was true for isolates a1 and c1 from patient 251 and isolates a6 and c10 from patient 612. We examined on a gene-by-gene basis whether gene presence or absence correlated with anatomical site, but we found no genes for which the data approached statistical significance.

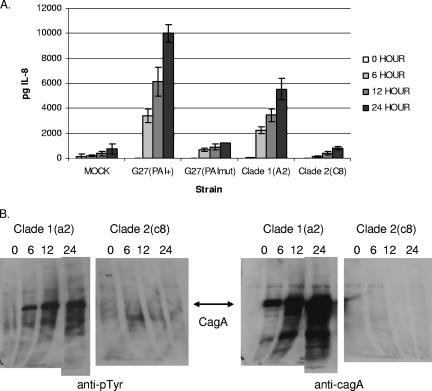

cag PAI genes were functional in a clade 1 isolate.

The distributions of the two strain populations in the stomach of patient 259 were different. Both clades were found in the fundus, corpus, and incisura angularis of the stomach, but in the antrum only clade 1 bacteria were isolated. A Fisher's exact test comparing the presence of the clade 1 bacteria and colonization of the antrum with the presence of the clade 1 bacteria and colonization of the rest of the stomach yielded a P value of 0.0337, suggesting that the clade 1 bacteria outcompeted clade 2 bacteria in the antrum but not in the rest of the stomach. These two strain populations differ at more than 100 gene loci and, importantly, differ at two loci previously implicated in enhanced virulence, the cag PAI and the vacA cytotoxin loci. Since the patient suffered from duodenal ulcers, we wondered if the clade 1 bacteria had a higher pathogenic potential and if the type IV secretion system encoded by the cag PAI actively induced host cell IL-8 production and translocation of the CagA effector protein.

To determine whether the genes of the cag PAI in clade 1 isolates were functional, we cocultured AGS cells with an isolate belonging to each clade from patient 259. Clade 1 bacteria induced levels of IL-8 secretion that were higher than the levels induced by a control strain having a mutation in the PAI (Fig. 4A). Additionally, this strain translocated CagA protein into host cells, allowing tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 4B). The clade 2 strain, in contrast, induced low levels of IL-8 secretion (Fig. 4A) and expressed no detectable CagA protein (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Clade 1 strains have a functional cag PAI. (A) IL-8 protein content determined by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay at 0, 6, 12, and 24 h for AGS human gastric adenocarcinoma cells cocultured with broth alone (MOCK), a control strain containing a functional cag PAI [G27(PAI+)], an isogenic strain with a mutation in the cag PAI [G27(PAImut)], clade 1 isolate 259a2 [Clade 1(A2)], and clade 2 isolate 259c8 [Clade 2(C8)]. Each bar indicates the mean for three wells. The standard deviations are indicated by error bars. (B) The cells described above were analyzed by immunoblotting to determine the presence of tyrosine-phosphorylated CagA using a monoclonal anti-phosphotyrosine antibody, and the blots were probed with a polyclonal antibody directed against CagA to verify the identity of the phosphorylated band and to determine the total amount of CagA protein. The clade 2 strain had no detectable CagA protein or phosphotyrosine signal in this portion of the gel due to the absence of the cagA gene. The 24-h assay mixture for clade 1 isolate a2 was run on a separate gel, and this gel was placed next to the gel containing the remaining mixtures using Adobe Photoshop software.

H. pylori strains from humans recently infected with a single isolate did not exhibit population-wide genetic variation.

Although our analysis of independent H. pylori isolates demonstrated that there was genetic divergence within the strain population in each individual's stomach, our data gave no indication of when the genetic events leading to this divergence occurred. To examine this issue, we performed an array CGH analysis with single-colony isolates from biopsy samples from four adult patients who were experimentally infected with a homogeneous strain in order to characterize a test strain for vaccine efficacy experiments (24). We analyzed two single-colony isolates from biopsy specimens obtained 15 and 90 days postinoculation. To increase the sensitivity and specificity, the array CGH protocol was modified so that the inoculating strain (BCS 100) was used as the reference instead of our normal reference, which consisted of the two sequenced strains used to generate the microarray. We considered for this analysis only the genes present in BCS 100 (1,576 genes) based on our standard array CGH profiling with the sequenced reference strains. No genes in any of the postinoculation isolates made our hybridization ratio cutoff for gene absence. The BCS 100 strain, however, was not expected to hybridize optimally to our microarrays due to sequence divergence, and in our previous quality control validation experiments we utilized the sequenced strains as the reference sample. Thus, we employed the GACK algorithm to look for gene divergence during infection. This algorithm more faithfully assesses genetic divergence or absence when sequences distinct from those used for array fabrication are assayed by using a dynamic cutoff based on the data distribution, and it gives an estimated probability of presence (EPP) as the output (31). When this analysis was performed, six of eight isolates showed no evidence of sequence divergence; for all genes the probability of gene presence was 100%. One of the two remaining isolates had a single gene, and the second isolate had seven genes with EPPs ranging from 40 to 95% (see Table S4 in the supplemental material). Both of the isolates that showed divergence were obtained from 15-day biopsy samples, and the 90-day isolates from the same patients showed no evidence of divergence. We sequenced the corresponding genomic DNA from the input and output strains for two genes from the 15-day output of patient 15 (JHP0616, 40% EPP; HP0478, 65% EPP) and the single gene with less than 100% EPP from the 15-day output of patient 104 (HP0859, 75% EPP). In all cases the input and output sequences were identical. Their levels of identity to the probe sequences on the microarray ranged from 70 to 95%, and the levels of identity correlated with the EPPs. This indicates that little, if any, genetic divergence and no changes in gene presence were generated in four patients shortly after infection with a homogeneous strain from an unrelated host. Although we analyzed only two isolates from four adult patients, the pairwise gene content difference between isolates was zero, compared to 5 to 32 for the 51 isolates from three Mexican adults and four Mexican children analyzed (see above).

DISCUSSION

Although genetic variation among H. pylori isolates is well established, the mechanism by which this variation is generated is not well understood. H. pylori strains have a wide range of mutation frequencies, some of which correspond to a mutator phenotype (8). However, more recent studies have shown that no mutations occur during passage in vitro or upon experimental infection of animals (37). Sequence analyses of genetic differences among paired isolates from the same patient have indicated that there are recombination-mediated events between substantially divergent sequences (20, 34). The goals of this study were to obtain insight into the genome-wide extent of bacterial genetic variation in the bacterial strain populations of infected individuals and to examine when and how this variation is generated.

In this study we investigated the genetic diversity of host bacterial populations in a Mexican population with a high rate of infection (80%). This Mexican population had a higher probability of mixed infection with multiple strains than other populations with lower infection rates, such as populations in the United States and Western Europe. For 11 of the 12 naturally infected patients analyzed, both the RAPD and AFLP approaches indicated that the strains isolated from a host were closely related. Array CGH analysis showed that >95% of the gene loci were highly conserved in strains from the same patient. Although the array CGH results support the hypothesis that the subjects were infected with a population of closely related strains, they also revealed evidence of widespread limited genetic divergence in the strain population in each patient. In single patients, the presence of 24 to 67 genes in single-colony isolates varied. A similar array CGH analysis of isolates from a single United States patient revealed variability in 44 gene loci (28). In a second study the researchers found evidence of genetic differences between pairs of isolates from four of seven (57%) Columbian patients and 5 of 14 (36%) American patients using array CGH (34). In our study we observed a higher frequency of genetic differences between pairs of isolates obtained from individuals from Mexico (100%), but the number of genetic loci affected was similar to the number reported previously (24 to 67 loci versus 44 loci). The higher frequency reported here may have resulted from the fact that more isolates were analyzed for each patient.

We initially considered two extreme models for the generation of a genetically diverse population in an infected individual's stomach. The first model posits a bottleneck during transmission, where a single clone or a few clones establish infection. The initially homogeneous population diversifies over time by mutation, and the genetic changes spread through the population by subsequent recombination between the naturally competent bacteria. Thus, considerable genetic variation could accumulate when the population is sampled in late adulthood, when H. pylori-related symptoms often present and after thousands of doublings have occurred. Alternatively, a second model suggests that children may be infected with a diverse collection of strains from unrelated donors. The diverse strains then homogenize over time via genetic exchange, again due to H. pylori's natural competence and efficient recombination machinery. Evidence which supports this model comes from recent studies with another population in which the endemic infection rate is high (17). Both models predict a difference in the extents of genetic variation in the bacterial populations present in the stomachs of adults and children. In our study, however, we found that the amount of genetic variation was independent of patient age; children as young as 5 years old and adults as old as 81 years old showed comparable variations in gene content.

It is possible that we did not observe a difference in genetic variation between children and adults because we did not sample children that were young enough. It has been proposed that upon infection of a new human host, mutation and/or recombination may be induced, which results in diversification (37). Once the infection is established, however, the potentially dangerous genomic instability might be down-regulated, allowing the population to stably persist. Since our youngest patient was 5 years old and the infection may have been acquired as early as 6 months of age, it is possible that accelerated diversification had already occurred. To address this possibility, we analyzed isolates obtained in a human challenge study performed with the homogeneous strain BCS 100 at 15 and 90 days postinfection (24). The adult volunteers were not related to each other and were not related to the patient from which the donor strain was obtained. Therefore, if host-specific differences select for genetic changes in the bacteria, we expected that such conditions were present during this experiment. In our array CGH and sequencing analyses we found no changes in gene content or sequence divergence up to 3 months after transmission.

Transiently superinfecting strains can donate genetic material that persists in the chronically infecting strain population and contributes to genetic diversity after the initial colonization event. The well-documented incidence of recurrent infection after antibiotic eradication in adults and children suggests that even adults continue to be exposed to H. pylori, at least in regions where the levels of infection are high (26, 47, 56). One patient in our study exhibited heterogeneity with all three tests for macrodiversity. We concluded that there were two distinct populations in patient 259 (designated clade 1 and clade 2) because in contrast to the 24 to 67 genes that varied in most patients, we observed 178 genes that varied, and 113 of these genes perfectly distinguished the two strain groups. Interestingly, within each clade the amount of gene variation was similar to the amount of gene variation observed in individual patients (36 genes). This suggests either that both the strain populations coexisted and diversified in this individual for some time or that this individual was recently infected with a second population of strains.

We were particularly interested in whether there was genetic exchange between the two strain populations since superinfection is a source of genetic variation via recombination of genomic DNA taken up by natural transformation. The presence of so many genes that perfectly distinguished the two clades argues against the hypothesis that there was a high rate of exchange between these two populations in spite of the fact that they were found to coexist at three separate biopsy sites. We sequenced four loci that showed variable hybridization within both clades and that have highly variable sequences in the three reference strains of H. pylori that have been sequenced. Consistent with a clonal genetic structure for each clade population, sequencing of approximately 6,000 bp of genomic DNA from each of six different isolates revealed identical clade-specific sequences with one exception. In the one exception, the polymorphisms observed are best explained by a recombination event with genomic DNA from an isolate belonging to the other clade population. Fortuitously, this recombination event resulted in an altered temperature requirement for PCR amplification of the region, which allowed us to ascertain that the recombination event occurred in only one of seven clade 2 isolates. The low frequency of recombination events observed raises the possibility that there are barriers to genetic exchange. The two strain populations differed in the presence of nine putative restriction-modification genes, which may constitute a very significant barrier to genetic exchange.

Polymorphisms that are best explained by a recombination event have been identified many times by other workers and indeed likely explain the variable loci that we observed in the host strain populations. The source of the recombinant sequences, however, usually cannot be identified. In our study, the most parsimonious explanation is that the recombinant sequence came from the second strain population in the host. Interestingly, one previously documented case of a recombination event between two strain populations in a single infected individual defined at the sequence level involved the cag PAI, a highly variable genomic region (30). The locus where we observed a recombination event also has a highly mosaic structure in the sequenced strains, as well as a number of clinical isolates (12). Thus, targeting such regions in addition to the housekeeping and virulence genes commonly used in MLST studies should help workers characterize the generation of diversity in H. pylori strains.

Most of the patients were colonized with a single strain population, but how did one patient sustain two largely independent strain populations? Among the genes that distinguish clades 1 and 2, the cag PAI genes stand out. Strains positive for the cag PAI are associated with peptic ulcers and gastric adenocarcinoma and induce a variety of cellular phenotypes during coculture with mammalian cells (38, 50). Only the clade 1 strain, which had a functional cag PAI, was found in the antrum and was presumably associated with the development of duodenal ulcers in this patient. Although we cannot exclude the possibility that clade 2 bacteria were simply missed in the antrum due to inadequate sampling, our data suggest that the ratio of the bacteria belonging to the two clades at this biopsy site was skewed compared to the ratio in the rest of the stomach.

The exclusive colonization of the antrum by clade 1 may indicate that this clade is more fit than clade 2 for colonization of this region. Colonization of a single human host by distinct populations of cag PAI+ and cag PAI− strains was documented in a previous study (30). Interestingly, in this study the workers also observed one type of strains exclusively in the antrum, but in this case both cag PAI+ and cag PAI− variants of this strain type were observed. The results of another study using a Mongolian gerbil infection model suggested that the colonization loads of isogenic strains having mutations in either cagA or other cag PAI genes were reduced in the corpus but not in the antrum (43). Together, these data make it very unlikely that the cag PAI is solely responsible for tropism to a particular region of the stomach, although it may affect colonization levels. Although it is not clear whether bacterial genotypes determine infection patterns (36), some strains have a specific and consistent tropism during animal infections (1). We were not able to find any genes that were present or absent exclusively in isolates obtained from a particular region of the stomach, although such negative results might have been expected given our small sample size.

Although the mechanism of H. pylori transmission in the human population has not been firmly established, vertical transmission within families with a bias toward maternally generated infection has been suggested. We suggest that a population of strains can persist during transmission, but this population has restricted diversity, presumably due to geographic and genetic isolation and selection in previous hosts. Further tests of whether diverse populations persist during transmission will require studies of multiple single-colony isolates from infected mothers, fathers, and children and will be technically challenging since endoscopy of healthy individuals would be required to obtain such samples. Such studies, however, might reveal genes required for transmission but not for persistence by identifying genes that are more frequently variable in adults than in children. In our study we identified a few genes that were present only in adults or children, but because of our limited sample size we could not draw any specific conclusions about these genes. The possibility of transmission with a mixed population could have important implications for vaccine design as some protein targets that have been examined (e.g., VacA and CagA) are encoded by genes that are among the genes that are often found to be variable in isolates, both between and within infected individuals. Additionally, molecular diagnostic methods will need to ensure adequate sampling of the bacterial population within individuals to determine the bacterial contribution to disease risk. Finally, it would be very interesting to determine how and why the variable loci (which include determinants of pathogenicity) are maintained in the population when they can clearly be lost or mutated in a subset of isolates. Analysis of infections with divergent strain populations in vitro and in animal models may begin to address these questions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We received financial support from the Pew Charitable Trusts Biomedical Scholars Program (N.R.S.); from Public Health Service grants AI054423 and DK53708 from the National Institutes of Health (N.R.S.); from a grant from CONACYT, Mexico (J.T.); from The Coordinacion de Investigacion en Salud, IMSS, Mexico (J.T.); from a Senior Clinical Fellowship from the Medical Research Council, UK (J.C.A.); and from grants from CORE and Cancer Research UK (J.C.A.).

We thank Marion Dorer for helpful discussions and for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 March 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akada, J. K., K. Ogura, D. Dailidiene, G. Dailide, J. M. Cheverud, and D. E. Berg. 2003. Helicobacter pylori tissue tropism: mouse-colonizing strains can target different gastric niches. Microbiology 149:1901-1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akopyanz, N., N. O. Bukanov, T. U. Westblom, S. Kresovich, and D. E. Berg. 1992. DNA diversity among clinical isolates of Helicobacter pylori detected by PCR-based RAPD fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:5137-5142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alm, R. A., L. S. Ling, D. T. Moir, B. L. King, E. D. Brown, P. C. Doig, D. R. Smith, B. Noonan, B. C. Guild, B. L. deJonge, G. Carmel, P. J. Tummino, A. Caruso, M. Uria-Nickelsen, D. M. Mills, C. Ives, R. Gibson, D. Merberg, S. D. Mills, Q. Jiang, D. E. Taylor, G. F. Vovis, and T. J. Trust. 1999. Genomic-sequence comparison of two unrelated isolates of the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 397:176-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amieva, M. R., N. R. Salama, L. S. Tompkins, and S. Falkow. 2002. Helicobacter pylori enter and survive within multivesicular vacuoles of epithelial cells. Cell. Microbiol. 4:677-690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atherton, J. C. 1996. Techniques to detect pathogenic strains of Helicobacter pylori, p. 133-143. In C. L. Clayton and H. L. T. Mobley (ed.), Methods in molecular medicine. Helicobacter pylori protocols. Humana Press Inc., Totowa, NJ.

- 6.Atherton, J. C., P. Cao, R. M. Peek, Jr., M. K. Tummuru, M. J. Blaser, and T. L. Cover. 1995. Mosaicism in vacuolating cytotoxin alleles of Helicobacter pylori. Association of specific vacA types with cytotoxin production and peptic ulceration. J. Biol. Chem. 270:17771-17777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aviles-Jimenez, F., D. P. Letley, G. Gonzalez-Valencia, N. Salama, J. Torres, and J. C. Atherton. 2004. Evolution of the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin in a human stomach. J. Bacteriol. 186:5182-5185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bjorkholm, B., M. Sjolund, P. G. Falk, O. G. Berg, L. Engstrand, and D. I. Andersson. 2001. Mutation frequency and biological cost of antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:14607-14612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boneca, I. G., H. de Reuse, J. C. Epinat, M. Pupin, A. Labigne, and I. Moszer. 2003. A revised annotation and comparative analysis of Helicobacter pylori genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:1704-1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brenner, H., M. Weyermann, and D. Rothenbacher. 2006. Clustering of Helicobacter pylori infection in couples: differences between high- and low-prevalence population groups. Ann. Epidemiol. 16:516-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carroll, I. M., N. Ahmed, S. M. Beesley, A. A. Khan, S. Ghousunnissa, C. A. Morain, C. M. Habibullah, and C. J. Smyth. 2004. Microevolution between paired antral and paired antrum and corpus Helicobacter pylori isolates recovered from individual patients. J. Med. Microbiol. 53:669-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chanto, G., A. Occhialini, N. Gras, R. A. Alm, F. Megraud, and A. Marais. 2002. Identification of strain-specific genes located outside the plasticity zone in nine clinical isolates of Helicobacter pylori. Microbiology 148:3671-3680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Copass, M., G. Grandi, and R. Rappuoli. 1997. Introduction of unmarked mutations in the Helicobacter pylori vacA gene with a sucrose sensitivity marker. Infect. Immun. 65:1949-1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Covacci, A., S. Censini, M. Bugnoli, R. Petracca, D. Burroni, G. Macchia, A. Massone, E. Papini, Z. Xiang, N. Figura, and R. Rappuoli. 1993. Molecular characterization of the 128-kDa immunodominant antigen of Helicobacter pylori associated with cytotoxicity and duodenal ulcer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:5791-5795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Danon, S. J., B. J. Luria, R. E. Mankoski, and K. A. Eaton. 1998. RFLP and RAPD analysis of in vivo genetic interactions between strains of Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter 3:254-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Hoon, M. J., S. Imoto, J. Nolan, and S. Miyano. 2004. Open source clustering software. Bioinformatics 20:1453-1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delport, W., M. Cunningham, B. Olivier, O. Preisig, and S. W. van der Merwe. 2006. A population genetics pedigree perspective on the transmission of Helicobacter pylori. Genetics 174:2107-2118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drumm, B., G. I. Perez-Perez, M. J. Blaser, and P. M. Sherman. 1990. Intrafamilial clustering of Helicobacter pylori infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 322:359-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eisen, M. B., P. T. Spellman, P. O. Brown, and D. Botstein. 1998. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:14863-14868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Falush, D., C. Kraft, N. S. Taylor, P. Correa, J. G. Fox, M. Achtman, and S. Suerbaum. 2001. Recombination and mutation during long-term gastric colonization by Helicobacter pylori: estimates of clock rates, recombination size, and minimal age. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:15056-15061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibson, J. R., E. Slater, J. Xerry, D. S. Tompkins, and R. J. Owen. 1998. Use of an amplified-fragment length polymorphism technique to fingerprint and differentiate isolates of Helicobacter pylori. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2580-2585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gollub, J., C. A. Ball, G. Binkley, J. Demeter, D. B. Finkelstein, J. M. Hebert, T. Hernandez-Boussard, H. Jin, M. Kaloper, J. C. Matese, M. Schroeder, P. O. Brown, D. Botstein, and G. Sherlock. 2003. The Stanford Microarray Database: data access and quality assessment tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:94-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gonzalez-Valencia, G., J. C. Atherton, O. Munoz, M. Dehesa, A. M. la Garza, and J. Torres. 2000. Helicobacter pylori vacA and cagA genotypes in Mexican adults and children. J. Infect. Dis. 182:1450-1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graham, D. Y., A. R. Opekun, M. S. Osato, H. M. El-Zimaity, C. K. Lee, Y. Yamaoka, W. A. Qureshi, M. Cadoz, and T. P. Monath. 2004. Challenge model for Helicobacter pylori infection in human volunteers. Gut 53:1235-1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gressmann, H., B. Linz, R. Ghai, K. P. Pleissner, R. Schlapbach, Y. Yamaoka, C. Kraft, S. Suerbaum, T. F. Meyer, and M. Achtman. 2005. Gain and loss of multiple genes during the evolution of Helicobacter pylori. PLoS Genet. 1:e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Halitim, F., P. Vincent, L. Michaud, N. Kalach, D. Guimber, F. Boman, D. Turck, and F. Gottrand. 2006. High rate of Helicobacter pylori reinfection in children and adolescents. Helicobacter 11:168-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han, S. R., H. C. Zschausch, H. G. Meyer, T. Schneider, M. Loos, S. Bhakdi, and M. J. Maeurer. 2000. Helicobacter pylori: clonal population structure and restricted transmission within families revealed by molecular typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3646-3651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Israel, D. A., N. Salama, U. Krishna, U. M. Rieger, J. C. Atherton, S. Falkow, and R. M. Peek, Jr. 2001. Helicobacter pylori genetic diversity within the gastric niche of a single human host. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:14625-14630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joyce, E. A., K. Chan, N. R. Salama, and S. Falkow. 2002. Redefining bacterial populations: a post-genomic reformation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3:462-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kersulyte, D., H. Chalkauskas, and D. E. Berg. 1999. Emergence of recombinant strains of Helicobacter pylori during human infection. Mol. Microbiol. 31:31-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim, C. C., E. A. Joyce, K. Chan, and S. Falkow. 2002. Improved analytical methods for microarray-based genome-composition analysis. Genome Biol. 3:RESEARCH0065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kivi, M., A. L. Johansson, M. Reilly, and Y. Tindberg. 2005. Helicobacter pylori status in family members as risk factors for infection in children. Epidemiol. Infect. 133:645-652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kivi, M., Y. Tindberg, M. Sorberg, T. H. Casswall, R. Befrits, P. M. Hellstrom, C. Bengtsson, L. Engstrand, and M. Granstrom. 2003. Concordance of Helicobacter pylori strains within families. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5604-5608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kraft, C., A. Stack, C. Josenhans, E. Niehus, G. Dietrich, P. Correa, J. G. Fox, D. Falush, and S. Suerbaum. 2006. Genomic changes during chronic Helicobacter pylori infection. J. Bacteriol. 188:249-254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuipers, E. J., D. A. Israel, J. G. Kusters, M. M. Gerrits, J. Weel, A. van Der Ende, R. W. van Der Hulst, H. P. Wirth, J. Hook-Nikanne, S. A. Thompson, and M. J. Blaser. 2000. Quasispecies development of Helicobacter pylori observed in paired isolates obtained years apart from the same host. J. Infect. Dis. 181:273-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li, L., R. M. Genta, M. F. Go, O. Gutierrez, J. G. Kim, and D. Y. Graham. 2002. Helicobacter pylori strain and the pattern of gastritis among first-degree relatives of patients with gastric carcinoma. Helicobacter 7:349-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lundin, A., B. Bjorkholm, I. Kupershmidt, M. Unemo, P. Nilsson, D. I. Andersson, and L. Engstrand. 2005. Slow genetic divergence of Helicobacter pylori strains during long-term colonization. Infect. Immun. 73:4818-4822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nilsson, C., A. Sillen, L. Eriksson, M. L. Strand, H. Enroth, S. Normark, P. Falk, and L. Engstrand. 2003. Correlation between cag pathogenicity island composition and Helicobacter pylori-associated gastroduodenal disease. Infect. Immun. 71:6573-6581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oh, J. D., H. Kling-Backhed, M. Giannakis, J. Xu, R. S. Fulton, L. A. Fulton, H. S. Cordum, C. Wang, G. Elliott, J. Edwards, E. R. Mardis, L. G. Engstrand, and J. I. Gordon. 2006. The complete genome sequence of a chronic atrophic gastritis Helicobacter pylori strain: evolution during disease progression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:9999-10004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Owen, R. J., M. Ferrus, and J. Gibson. 2001. Amplified fragment length polymorphism genotyping of metronidazole-resistant Helicobacter pylori infecting dyspeptics in England. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 7:244-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prouzet-Mauleon, V., M. A. Hussain, H. Lamouliatte, F. Kauser, F. Megraud, and N. Ahmed. 2005. Pathogen evolution in vivo: genome dynamics of two isolates obtained 9 years apart from a duodenal ulcer patient infected with a single Helicobacter pylori strain. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:4237-4241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raymond, J., J. M. Thiberg, C. Chevalier, N. Kalach, M. Bergeret, A. Labigne, and C. Dauga. 2004. Genetic and transmission analysis of Helicobacter pylori strains within a family. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10:1816-1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rieder, G., J. L. Merchant, and R. Haas. 2005. Helicobacter pylori cag-type IV secretion system facilitates corpus colonization to induce precancerous conditions in Mongolian gerbils. Gastroenterology 128:1229-1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salama, N., K. Guillemin, T. K. McDaniel, G. Sherlock, L. Tompkins, and S. Falkow. 2000. A whole-genome microarray reveals genetic diversity among Helicobacter pylori strains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:14668-14673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salaun, L., B. Linz, S. Suerbaum, and N. J. Saunders. 2004. The diversity within an expanded and redefined repertoire of phase-variable genes in Helicobacter pylori. Microbiology 150:817-830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smeets, L. C., N. L. Arents, A. A. van Zwet, C. M. Vandenbroucke-Grauls, T. Verboom, W. Bitter, and J. G. Kusters. 2003. Molecular patchwork: chromosomal recombination between two Helicobacter pylori strains during natural colonization. Infect. Immun. 71:2907-2910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Soto, G., C. T. Bautista, D. E. Roth, R. H. Gilman, B. Velapatino, M. Ogura, G. Dailide, M. Razuri, R. Meza, U. Katz, T. P. Monath, D. E. Berg, and D. N. Taylor. 2003. Helicobacter pylori reinfection is common in Peruvian adults after antibiotic eradication therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 188:1263-1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Suerbaum, S., J. M. Smith, K. Bapumia, G. Morelli, N. H. Smith, E. Kunstmann, I. Dyrek, and M. Achtman. 1998. Free recombination within Helicobacter pylori. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:12619-12624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suto, H., M. Zhang, and D. E. Berg. 2005. Age-dependent changes in susceptibility of suckling mice to individual strains of Helicobacter pylori. Infect. Immun. 73:1232-1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takata, T., S. Fujimoto, K. Anzai, T. Shirotani, M. Okada, Y. Sawae, and J. Ono. 1998. Analysis of the expression of CagA and VacA and the vacuolating activity in 167 isolates from patients with either peptic ulcers or non-ulcer dyspepsia. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 93:30-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taylor, N. S., J. G. Fox, N. S. Akopyants, D. E. Berg, N. Thompson, B. Shames, L. Yan, E. Fontham, F. Janney, F. M. Hunter, et al. 1995. Long-term colonization with single and multiple strains of Helicobacter pylori assessed by DNA fingerprinting. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:918-923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thompson, L. J., S. J. Danon, J. E. Wilson, J. L. O'Rourke, N. R. Salama, S. Falkow, H. Mitchell, and A. Lee. 2004. Chronic Helicobacter pylori infection with Sydney strain 1 and a newly identified mouse-adapted strain (Sydney strain 2000) in C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice. Infect. Immun. 72:4668-4679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tomb, J. F., O. White, A. R. Kerlavage, R. A. Clayton, G. G. Sutton, R. D. Fleischmann, K. A. Ketchum, H. P. Klenk, S. Gill, B. A. Dougherty, K. Nelson, J. Quackenbush, L. Zhou, E. F. Kirkness, S. Peterson, B. Loftus, D. Richardson, R. Dodson, H. G. Khalak, A. Glodek, K. McKenney, L. M. Fitzegerald, N. Lee, M. D. Adams, E. K. Hickey, D. E. Berg, J. D. Gocayne, T. R. Utterback, J. D. Peterson, J. M. Kelley, M. D. Cotton, J. M. Weidman, C. Fujii, C. Bowman, L. Watthey, E. Wallin, W. S. Hayes, M. Borodovsky, P. D. Karp, H. O. Smith, C. M. Fraser, and J. C. Venter. 1997. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 388:539-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van der Ende, A., E. A. Rauws, M. Feller, C. J. Mulder, G. N. Tytgat, and J. Dankert. 1996. Heterogeneous Helicobacter pylori isolates from members of a family with a history of peptic ulcer disease. Gastroenterology 111:638-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weyermann, M., G. Adler, H. Brenner, and D. Rothenbacher. 2006. The mother as source of Helicobacter pylori infection. Epidemiology 17:332-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wheeldon, T. U., T. T. Hoang, D. C. Phung, A. Bjorkman, M. Granstrom, and M. Sorberg. 2005. Long-term follow-up of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in Vietnam: reinfection and clinical outcome. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 21:1047-1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wong, B. C., W. H. Wang, D. E. Berg, F. M. Fung, K. W. Wong, W. M. Wong, K. C. Lai, C. H. Cho, W. M. Hui, and S. K. Lam. 2001. High prevalence of mixed infections by Helicobacter pylori in Hong Kong: metronidazole sensitivity and overall genotype. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 15:493-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.