Abstract

Signal transduction pathways in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes utilize protein phosphorylation as a key regulatory mechanism. Recent studies have proven that eukaryotic-type serine/threonine protein kinases (Hank's type) are widespread in many bacteria, although little is known regarding the cellular processes they control. In this study, we have attempted to establish the role of a single eukaryotic-type protein kinase, StkP of Streptococcus pneumoniae, in bacterial survival. Our results indicate that the expression of StkP is important for the resistance of S. pneumoniae to various stress conditions. To investigate the impact of StkP on this phenotype, we compared the whole-genome expression profiles of the wild-type and ΔstkP mutant strains by microarray technology. This analysis revealed that StkP positively controls the transcription of a set of genes encoding functions involved in cell wall metabolism, pyrimidine biosynthesis, DNA repair, iron uptake, and oxidative stress response. Despite the reduced transformability of the stkP mutant, we found that the competence regulon was derepressed in the stkP mutant under conditions that normally repress natural competence development. Furthermore, the competence regulon was expressed independently of exogenous competence-stimulating peptide. In summary, our studies show that a eukaryotic-type serine/threonine protein kinase functions as a global regulator of gene expression in S. pneumoniae.

Signal transduction pathways are essential for the regulation of gene expression in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Signal transduction in prokaryotes was considered to occur primarily by histidine protein kinases that activate transcription by the phosphorylation of cognate response regulators (72). Recent studies have clearly demonstrated that this paradigm requires further investigation (reviewed in reference 13). Eukaryotic-type Ser/Thr protein kinases (STPKs) as well as Ser/Thr phosphoprotein phosphatases (STPPs) operate in many bacteria, constituting a signaling network independent of the canonical two-component system circuits. However, compared to their eukaryotic counterparts, the signals to which STPKs and STPPs respond, the mechanism of signal transduction, and their substrates remain poorly understood.

Prokaryotic STPKs have been shown to regulate various cellular functions, such as developmental processes (47, 37, 49), secondary metabolism (77), stress responses (27, 50), metabolic processes (48, 66), biofilm formation (27), and also virulence in streptococci (18, 28, 64), Yersinia pseudotuberculosis (21), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (80), and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (14, 79). Although these studies established the function of protein kinases, only several target substrates have been identified to date (16, 31, 42, 48, 55, 64, 66, 78). The result of posttranslational modification of a substrate on its function has been demonstrated in just a minority of cases (49, 66).

In contrast to the case with many microorganisms, Streptococcus pneumoniae and other streptococci contain a single gene encoding an STPK, which is genetically linked to a protein phosphatase-encoding gene (18, 28, 64). As a result, this feature makes them a more straightforward and practical model for defining the regulatory functions provided by these proteins.

We recently characterized the biochemical properties of both the protein kinase StkP and the protein phosphatase PhpP of S. pneumoniae and showed that the autophosphorylated form of StkP is a substrate for PhpP. These results suggest that StkP and PhpP could operate as a functional pair in vivo (55). It has been demonstrated that such functional coupling could play a role in the control of kinase activity (4). An analysis of phosphoproteome maps of both wild-type and stkP-null mutant strains revealed that one of the endogenous substrates of StkP is phosphoglucosamine mutase GlmM (55). GlmM is an essential enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine, a key common precursor to cell envelope components (41). The phosphorylation of GlmM is necessary for its activity in Escherichia coli and is achieved during an autophosphorylation process (29). On the other hand, the phosphorylation of GlmM by StkP is not essential for its enzymatic activity since the S. pneumoniae stkP mutant is viable. In addition to GlmM, we have identified the α-subunit of RNA polymerase as another substrate of StkP in in vivo-labeling experiments, although the significance of its modification is unclear (55).

It has also been shown that the mutation of stkP attenuates virulence in both pneumonia and bacteremia models of infection, indicating that StkP plays an important role for bacterial survival in vivo (18). A recent report by Oggioni et al. provided evidence that the expression of stkP was significantly increased in vivo in both the blood and tissues of infected mice (56). During the infection process, S. pneumoniae is exposed to various stress factors, including nutritional deprivation, temperature shift, pH changes, increased osmolality, and reactive oxygen species generated by host phagocytes. Due to the transmembrane topology of StkP and the presence of an extracellular sensor domain containing reiterated PASTA (penicillin binding protein and Ser/Thr protein kinase-associated domain) signature sequences (81), we hypothesized that StkP could transmit environmental cues into the cell.

Here we report the growth characteristics of an S. pneumoniae stkP mutant under different stress conditions. These results suggest that the expression of StkP can contribute to the resistance of S. pneumoniae to environmental stresses. Microarray analysis was used to compare the expression profile of the stkP mutant with that of the wild type. This analysis revealed that the stkP mutation is broadly pleiotropic and affects the transcription of several sets of important genes. Several functional gene categories have been identified that could account for a reduced stress response and attenuated virulence. Furthermore, we show that StkP of S. pneumoniae plays a role in the maintenance of low expression levels of competence genes under conditions that do not support competence development. Finally, we propose a hypothesis to describe the putative mechanism of competence deficiency in an stkP mutant.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

S. pneumoniae strain CP1015 (44) and its isogenic derivative, CP1015ΔstkP (like CP1015 but ΔstkP::Cm [55]), were grown at 37°C in casein tryptone (CAT) medium supplemented with 0.2% glucose and 1/30 volume 0.5 M K2HPO4, pH 7.5. DNA from strain CP1016 (rif-23) was used as donor DNA for transformation assays (45). The following antibiotics were added when necessary at the indicated concentrations: chloramphenicol, 10 μg ml−1; and rifampin, 1 μg ml−1.

Construction of S. pneumoniae stkP mutant.

The deletion of the stkP gene was achieved by transforming an S. pneumoniae wild-type strain with a vectorless DNA fragment consisting of stkP downstream and upstream regions of homology and a cat cassette replacing the stkP coding region as previously described (55). Viable chloramphenicol-resistant clones arising from a double-crossover event were readily obtained after S. pneumoniae transformation. The resulting clones were further examined for successful allelic exchange by diagnostic PCR and Southern hybridization. The junctions between exogenous and chromosomal DNA were verified by sequencing.

In vitro stress experiments.

To compare the effect of temperature stress on the wild-type and ΔstkP mutant strains, we used the same number of cells (4 × 104 CFU ml−1) to inoculate CAT medium prewarmed to 37 and 40°C. Cultures were incubated statically under aerobic conditions at the indicated temperatures. At 1-h intervals, samples were removed and their optical densities (OD) were determined at a wavelength of 400 nm.

The sensitivity of cells to H2O2 was tested by exposing aliquots of cultures (107 CFU ml−1; OD400 = 0.4) grown in CAT medium at 37°C to 40 mM H2O2 for 5, 10, 15, and 20 min at 37°C. Viable cells were counted by plating them onto agar plates before and after exposure to H2O2, and results were expressed as percentages of survival.

Adaptability of the wild-type and isogenic CP1015ΔstkP mutant to osmotic stress was evaluated by monitoring bacterial growth in CAT medium containing 400 mM NaCl. To initiate the growth experiments, bacteria grown to early exponential phase (OD400 = 0.2) were inoculated into prewarmed CAT medium with or without NaCl. At 1-h intervals, bacterial growth was monitored by measuring the OD400.

To study the role of StkP in acid tolerance, we used equal numbers of cells (4 × 104 CFU ml−1) of both the wild-type strain and the ΔstkP mutant to inoculate CAT medium adjusted to pHs 6.5 and 7.5. At 1-h intervals, samples were withdrawn and the OD400 values were determined.

RNA extraction.

For an analysis of the transcriptome and quantitative real-time PCR, RNA was isolated from 50 ml of pneumococcal culture grown at 37°C in CAT medium to an OD400 of 0.4. Total bacterial RNA was extracted with hot acid phenol according to the method of Cheng et al. (10). After preliminary purification and precipitation with isopropanol, the crude RNA was treated with DNase I (Ambion) and purified further using RNeasy columns (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The typical yield from 50 ml of cells was approximately 200 μg of purified RNA.

Reverse transcription and microarray hybridization.

Commercial S. pneumoniae whole-genome microarray slides from Eurogentec (Belgium) were used in this study. The full genome array consists of amplicons representing segments of 2,085 open reading frames from S. pneumoniae reference strain TIGR4 spotted in duplicate on a glass slide.

Ten micrograms of purified RNA samples was reverse transcribed and differentially labeled with Cy3-dCTP and Cy5-dCTP (Amersham Biosciences) in the presence of random hexamer primers (Amersham Biosciences) and SuperScript II RNase H− RT (Invitrogen) in a total volume of 20 μl. The reaction mixture was incubated at 42°C for 1.5 h. Dye swap labeling was performed systematically for all labeled RNA samples. Pairs of Cy3- and Cy5-labeled cDNA samples were mixed and hybridized to the array at 37°C for 15 h. After hybridization, the slides were washed in 0.2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)-0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate for 5 min, followed by a wash in 0.2× SSC for 5 min.

Data analysis.

The arrays were scanned using the GeneTAC UC-4 scanner (Genomic Solutions). TIGR Spotfinder 2.2.3 (71) was used for determining the average signal intensity and the local background for each spot. The Cy3/Cy5 fluorescence ratios were log2 transformed and normalized by LOWESS normalization in the TIGR microarray data analysis system (MIDAS) 2.17 (71). In total, six hybridizations using samples from three independent bacterial cultures and RNA extractions were performed and the average was calculated from the independent experiments. The statistical significance of the expression ratios was determined by applying the Student t test. Genes whose expression ratios changed by a factor of at least 2 and had P values of <0.01 were considered significantly regulated by StkP (95 genes). In order to verify the significance of regulation by a different statistical method, the data matrix of log2-transformed gene expression ratios of all replicates was imported into TIGR MultiExperiment Viewer (MeV) 4.0 (71) and analyzed by a one-class significance analysis of microarrays (SAM) test (76). SAM statistics were based on all 4,096 possible permutations, and the threshold delta value (Δ = 0.91) was based on delta versus the percent false discovery rate table reported by SAM to avoid any falsely significant genes. SAM identified 208 significantly regulated genes and confirmed all 97 genes identified by Student t test and expression ratio threshold.

Validation of array data.

The significance of signals obtained from microarray hybridizations was verified by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) (see below) using Sybr green I JumpStart Taq ReadyMix kit (Sigma). Six derepressed genes (spr0013, spr0857, spr1109, spr1724, spr1864, and spr2041), eight repressed genes (spr0096, spr0867, spr0934, spr1057, spr1154, spr1320, spr1684, and spr2021), and two stably expressed genes (spr0708 and spr1757) were chosen for this confirmatory study. qRT-PCRs were performed with the same RNA samples that were used for microarray analysis. For each gene, three biological replicates with three technical replicates each were used.

Competence gene expression.

Cells were grown in CAT medium at 37°C until an OD400 of 0.4 before exposure to competence-stimulating peptide (CSP) (250 ng ml−1). At specified intervals (8 and 13 min) after the addition of CSP, total RNAs were extracted (see above). Sample “0” was taken before the addition of CSP. Reverse transcription was performed as described above. For the expression profile analysis of competence genes, qRT-PCR was performed (see below) on a select group of competence genes: spr0013, spr0020, spr0043, spr0857, spr1724, spr1864, spr2041, and spr2043.

qRT-PCR.

qRT-PCRs were carried out in a Mxp3000 LightCycler instrument (Stratagene). All primers were calculated using Primer3 services at http://frodo.wi.mit.edu. PCR products were approximately 100 bp in length. A master mix of the following reaction components was prepared to the following end concentrations: 6.9 μl water, 1 μl forward primer (0.5 μM), 1 μl reverse primer (0.5 μM), 0.2 μl internal Rox reference dye, and 9.9 μl Sybr green JumpStart Taq ReadyMix (Sigma). One microliter of cDNA (50 ng reverse-transcribed total RNA) was added as a PCR template. Amplification was performed using the following cycling protocol: 3 min of initial denaturation at 95°C, followed by a three-step profile consisting of 30 s of denaturation at 95°C, 25 s of annealing at 60°C, and 25 s of extension at 72°C for a total of 40 cycles. Each qRT-PCR was performed in triplicate using RNA from two independent isolations, and no-reverse-transcriptase controls were also included. The change in expression of each gene in the wild-type and CP1015ΔstkP mutant strain was calculated according to the equation of Pfaffl (62). Values were normalized to the reference gyrA gene (spr1099) encoding the DNA gyrase subunit A. Melting curve analysis was also performed to evaluate PCR specificity and resulted in single primer-specific melting temperatures. For a list of the primers used, see Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Complementation experiment.

An S. pneumoniae strain with an ectopic copy of the pcsB gene was constructed by transformation with a synthetic linear PCR amplicon kindly provided by M. Winkler (51). A bgaA::[kan-t1t2-PfcsK]-pcsB+ fragment was inserted into the dispensable bgaA chromosomal gene. The presence of the desired mutation was verified by screening for changes in the sizes of fragments amplified from chromosomal DNA using the flanking primers.

Competence assay.

The transformation was performed as described previously (35). Briefly, cells were grown in CAT medium at 37°C to OD400 values of 0.1 and 0.4. Appropriate aliquots were withdrawn, incubated in the presence or absence of CSP (250 ng ml−1), and mixed with rif-23 donor DNA (1 μg ml−1). Further incubation was carried out at 37°C for 1 h before plating in CAT agar containing 1 μg Rif ml−1. Serial dilutions of transformed cultures were plated, and transformation efficiencies were calculated as the ratio of the viable counts on plates with and without rifampin. Results are expressed as the mean counts from two independent experiments.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

S. pneumoniae has been shown to contain a single gene coding for a eukaryotic-type protein kinase functionally coupled to its cognate protein phosphatase (55). Studies performed with virulent strains suggested that an stkP mutation severely affects virulence in a murine model of infection (18). The results presented in this work report two significant findings. First, we demonstrate that the stkP mutation confers a phenotype that is sensitive to many stress conditions, including elevated temperature, oxidizing agents, osmotic pressure, and acidic conditions. Second, by using microarray analysis, we have identified genes belonging to several functional categories whose expressions were affected at the transcriptional level in an stkP mutant.

In vitro growth phenotype of the ΔstkP mutant.

Prior to studying the effect of the stkP mutation on the global expression profile of S. pneumoniae, we first examined the growth characteristics of the stkP-null mutant in vitro. The stkP mutant strain displayed small but significant changes in growth properties under nonstress conditions. A comparison of the growth levels of the mutant and parent strains in CAT medium at 37°C showed that the mutant had a significantly reduced growth rate compared to that of the parent strain in the early exponential phase (Fig. 1A). The calculated doubling time of the mutant was increased to 55 min compared to 35 min for the parent strain. In addition, cultures of the mutant strain exhibited an increased rate of autolysis at the stationary phase of growth and did not achieve the same final optical density as the parent strain. The extended lag phase and slower doubling time in the early exponential phase and the recovery of growth with a rate approaching that of the wild type in the mid-exponential phase, which we observed in our studies, are reminiscent of those observed for protein kinase mutants in other streptococci (27, 28, 64).

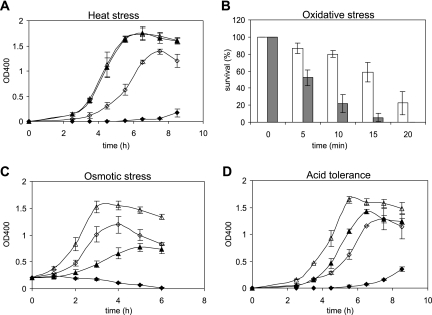

FIG. 1.

In vitro stress experiments. (A) Growth curves of the wild type (triangles) and the stkP-deficient mutant (diamonds) at different temperatures. A total of 4 × 104 CFU ml−1 of each strain was used to inoculate CAT medium prewarmed at the indicated temperatures. Bacteria were grown at 37°C (open symbols) and 40°C (filled symbols). Samples were taken at 1-h intervals for measurement of the OD400. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (B) H2O2 survival test of the wild type (open columns) and the stkP-deficient mutant (gray columns). In the assays, cells were grown in CAT medium at 37°C to an OD400 of 0.4 and the aliquots (107 CFU) were used in each assay. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 5, 10, 15, and 20 min without or with 40 mM H2O2, and viable counts were carried out. Experiments were performed in triplicate. (C) Growth curves as measured by the ODs of the wild type (triangles) and the stkP-deficient mutant (diamonds) grown in CAT (open symbols) and CAT plus 400 mM NaCl (filled symbols). The growth of cultures was monitored from an initial OD400 of 0.2. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (D) Growth curves of the wild type (triangles) and the stkP-deficient mutant (diamonds) at different pHs. Equal numbers of cells (4 × 104 CFU ml−1) of both the wild-type strain and the ΔstkP mutant were used to inoculate CAT medium adjusted to pHs 6.5 (filled symbols) and 7.5 (open symbols), and bacteria were grown at 37°C. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviations of the means.

We also studied the growth phenotype of the ΔstkP mutant at an elevated temperature. In contrast to the parent strain, which was unaffected at 40°C, the growth of the mutant strain was almost completely impaired (Fig. 1A). This result suggests that StkP regulates genes involved in adaptation to high temperatures.

Sensitivity of the ΔstkP mutant to oxidative stress.

To determine whether the ΔstkP strain has an altered sensitivity to oxidative stress, its ability to survive H2O2- and superoxide (O2−)-induced oxidative stress was examined and compared with that of the parental strain. Decreased survival of the ΔstkP mutant, compared to that of the wild type, was observed at 40 mM H2O2 (Fig. 1B). After 15 min of treatment with 40 mM hydrogen peroxide, 96% of the ΔstkP cells were killed, whereas 69% of the wild-type cells survived. Both the wild-type and mutant strains were also exposed to 50 mM paraquat over a 30-min period. In contrast to the results of experiments using hydrogen peroxide as an oxidative agent, both the wild type and the ΔstkP mutant exhibited virtually the same sensitivity to superoxide (data not shown). This sensitivity to oxidative killing might be a major contributor to the attenuated virulence of the stkP mutant (18), since such cells would be less likely to survive attacks by the innate host defense system.

The ΔstkP mutant strain is more susceptible to osmotic stress.

To further characterize the ability of the stkP mutant strain to cope with stress conditions, its growth was measured under high osmolality. Growth of the wild-type strain in CAT medium containing 400 mM NaCl was impaired (Fig. 1C). The stkP mutant strain exhibited no discernible growth, and virtually all of the cells lysed at the end of cultivation. Hence, the stkP mutant has a reduced tolerance to osmotic stress.

The ΔstkP mutant strain is less tolerant to acidic pH.

A comparison of the growth of the wild-type and mutant strains under mild acidic conditions (pH 6.5) showed that the stkP mutant is much less tolerant to an acidic pH (Fig. 1D). In contrast to that of the parent strain, which was only slightly affected, the growth of the mutant strain was significantly slower with an extended lag phase. A similar effect of Ser/Thr protein kinase deletion on acid tolerance has been observed in Streptococcus mutans (27). Taken together, these data indicate that the stkP mutation confers sensitivity to a variety of stressors, suggesting that it very likely affects numerous different cellular functions.

Global transcription profile of the ΔstkP mutant.

To begin to address the genetic basis of these phenotypes, we performed an analysis of global transcription of the ΔstkP mutant compared to the wild-type parent in the exponential phase (OD400 = 0.4) in CAT. Custom S. pneumoniae whole-genome microarray slides from Eurogentec (Materials and Methods) were used throughout this study. In total, six independent hybridizations using RNA samples from three separate bacterial cultures were performed for both strains. After background subtraction and normalization, the data were processed and statistically evaluated (Materials and Methods). Among 2,085 genes evaluated, changes in relative transcript amounts of at least twofold were observed for 95 genes. Under the conditions used, more than 4% of S. pneumoniae genes were identified as transcriptionally affected, indicating a global regulatory function for the StkP signaling protein. Complete lists of genes with affected transcript levels are given in Tables 1 and 2. The majority of altered genes could be clustered into several different functional categories.

TABLE 1.

Down-regulated genes in the ΔstkP mutant strain

| Functional category | Gene no. | Gene product (gene) | Mean of log2 ratios | P value | Expression ratioa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell wall | spr0096 | Hypothetical protein, LysM domain protein | −3.46 | 6.57E-07 | −11.01 |

| spr0867 | Endo-beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase (lytB) | −2.26 | 3.25E-11 | −4.78 | |

| spr2021 | General stress protein PcsB (pcsB) | −3.24 | 5.37E-09 | −9.47 | |

| Glycerol metabolism | spr1344 | Glycerol uptake facilitator protein paralog (glpF) | −1.05 | 2.02E-06 | −2.08 |

| spr1990 | Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, truncation (glpD) | −1.01 | 6.00E-04 | −2.01 | |

| spr1991 | Glycerol kinase (glpK) | −1.37 | 4.82E-05 | −2.58 | |

| Pyrimidine metabolism | spr0613 | Orotidine-5′-decarboxylase (pyrF) | −1.54 | 8.75E-09 | −2.90 |

| spr0614 | Orotate phosphoribosyltransferase (pyrE) | −1.55 | 1.92E-10 | −2.92 | |

| spr0865 | Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase electron transfer subunit (pyrDII) | −2.07 | 2.84E-08 | −4.19 | |

| spr0866 | Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (pyrD) | −2.38 | 2.49E-11 | −5.21 | |

| spr1053 | Dihydroorotase (pyrC) | −1.50 | 7.59E-07 | −2.83 | |

| spr1153 | Carbamoylphosphate synthase (ammonia), heavy subunit (carB) | −1.43 | 1.21E-08 | −2.69 | |

| spr1154 | Carbamoylphosphate synthase (glutamine-hydrolyzing) light subunit (carA) | −1.27 | 4.64E-09 | −2.41 | |

| spr1155 | Aspartate carbamoyltransferase (pyrB) | −1.30 | 6.19E-10 | −2.47 | |

| spr1156 | Transcriptional attenuation of the pyrimidine operon/uracil phosphoribosyltransferase activity (pyrR) | −1.49 | 5.80E-08 | −2.80 | |

| spr1165 | Uracil permease (pyrP) | −1.94 | 3.65E-09 | −3.83 | |

| DNA repair | spr1054 | 8-oxo-dGTP nucleoside triphosphatase (mutX) | −1.95 | 4.63E-10 | −3.88 |

| spr1055 | DNA-uracil glycosylase (ung) | −2.03 | 1.48E-09 | −4.08 | |

| spr1317 | O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (ogt) | −1.02 | 8.51E-11 | −2.02 | |

| spr1660 | Exodeoxyribonuclease (exoA) | −1.20 | 5.16E-05 | −2.30 | |

| Iron uptake | spr0934 | ABC transporter substrate binding protein-iron transport | −1.16 | 1.30E-05 | −2.23 |

| spr1684 | ABC transporter membrane-spanning permease-ferric iron transport (fatD) | −1.04 | 1.86E-02 | −2.10 | |

| spr1685 | ABC transporter membrane-spanning permease-ferric iron transport (fatC) | −1.51 | 1.15E-04 | −2.85 | |

| spr1686 | ABC transporter ATP binding protein-ferric iron transport (fecE) | −1.67 | 1.93E-03 | −3.17 | |

| spr1687 | ABC transporter substrate binding protein-ferric iron transport (fatB) | −2.23 | 1.43E-04 | −4.70 | |

| Oxidative stress | spr1321 | Conserved hypothetical protein, similar to amidotransferase, SNO family | −1.25 | 2.08E-03 | −2.38 |

| spr1322 | Pyridoxine biosynthesis protein (pdx1) | −1.10 | 1.22E-03 | −2.14 | |

| spr1495 | Thioredoxin-linked thiol peroxidase (psaD) | −1.15 | 2.88E-03 | −2.21 | |

| Other | spr0551 | Branched-chain amino acid transport system carrier protein (brnQ) | −1.21 | 3.18E-05 | −2.31 |

| spr1047 | Lipoate protein ligase A (lplA) | −1.01 | 4.08E-05 | −2.02 | |

| spr1048 | Dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (acoL) | −1.10 | 3.91E-04 | −2.14 | |

| spr1577 | Eukaryotic-type serine/threonine kinase (stkP) | −4.46 | 3.66E-04 | −22.04 | |

| spr1657 | ABC transporter ATP binding/membrane spanning protein | −1.01 | 3.37E-06 | −2.01 | |

| Hypothetical genes | spr0084 | Conserved hypothetical protein, rhodanese-like protein | −1.70 | 5.31E-06 | −3.24 |

| spr0552 | Conserved hypothetical protein, M42 glutamyl aminopeptidase homologue | −1.23 | 9.50E-04 | −2.34 | |

| spr0652 | Conserved hypothetical protein, degV family | −2.20 | 4.94E-10 | −4.61 | |

| spr0709 | Hypothetical protein | −1.14 | 6.85E-05 | −2.20 | |

| spr0755 | Conserved hypothetical protein, putative lipoprotein precursor | −1.04 | 1.22E-04 | −2.06 | |

| spr1052 | Conserved hypothetical protein, MATE efflux protein family | −1.08 | 6.76E-07 | −2.12 | |

| spr1056 | Hypothetical protein | −3.14 | 3.76E-04 | −8.81 | |

| spr1057 | Conserved hypothetical protein, hydrolase HAD-like family | −5.87 | 3.33E-10 | −58.52 | |

| spr1316 | Conserved hypothetical protein, similar to arsenate reductase | −1.08 | 1.16E-10 | −2.12 | |

| spr1318 | Hypothetical protein, putative acetyltransferase | −1.13 | 1.72E-08 | −2.19 | |

| spr1319 | Hypothetical protein | −2.69 | 1.76E-06 | −6.47 | |

| spr1320 | Conserved hypothetical protein, similar to hemolysin III | −3.34 | 1.66E-05 | −10.16 | |

| spr1436 | Conserved hypothetical protein, methyltransferase-like protein | −1.57 | 3.01E-05 | −2.98 | |

| spr1498 | Conserved hypothetical protein, putative large secreted protein | −1.03 | 2.33E-04 | −2.05 | |

| spr1790 | Conserved hypothetical protein, related to sporulation protein, SpoIIIJ | −1.17 | 5.43E-08 | −2.26 |

The ratio of the gene expression level in the ΔstkP mutant strain compared to that of the wild-type strain.

TABLE 2.

Up-regulated genes in the ΔstkP mutant strain

| Functional category | Gene no. | Gene product (gene) | Mean of log2 ratios | P value | Expression ratioa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early competence genes | spr0020 | Competence protein (comW) | 2.84 | 1.80E-04 | 7.18 |

| spr0043 | Transport ATP binding protein ComA (comA) | 3.27 | 2.77E-05 | 9.65 | |

| spr0044 | Transport protein ComB (comB) | 4.99 | 7.60E-06 | 31.73 | |

| spr2041 | Response regulator (comE) | 5.12 | 1.20E-05 | 34.76 | |

| spr2042 | Histidine protein kinase (comD) | 5.24 | 1.98E-06 | 37.81 | |

| spr2043 | Competence stimulating peptide precursor (comC) | 3.29 | 2.29E-04 | 9.76 | |

| spr0013/1819 | Competence-specific global transcription modulator (comX/comX2) | 4.22 | 1.13E-04 | 18.59 | |

| Late competence genes | spr0857 | Competence protein (celB) | 1.39 | 7.00E-03 | 2.62 |

| spr1144 | DNA processing Smf protein (smf) | 1.46 | 3.43E-03 | 2.75 | |

| spr1724 | Single-stranded DNA binding protein (ssbB) | 1.71 | 8.68E-05 | 3.27 | |

| spr1758 | Competence induced protein A (cinA) | 1.17 | 5.70E-04 | 2.26 | |

| spr1861 | Competence protein (cglD) | 1.35 | 4.29E-03 | 2.54 | |

| spr1863 | Competence protein (cglB) | 3.00 | 2.55E-03 | 8.02 | |

| spr1864 | Competence protein (cglA) | 2.92 | 1.19E-03 | 7.57 | |

| Competence-related CSP-induced genes | |||||

| Bacteriocin production | spr0472 | BlpY protein (blpY) | 1.50 | 3.99E-03 | 2.83 |

| spr0473 | Hypothetical protein (blpZ) | 1.24 | 6.54E-03 | 2.36 | |

| spr0474 | ABC transporter ATP binding protein (pncP) | 1.07 | 3.25E-03 | 2.10 | |

| spr1561 | ABC transporter membrane-spanning permease-Na+ export (natB) | 1.88 | 2.43E-03 | 3.69 | |

| spr1562 | ABC transporter ATP binding protein-Na+ export (natA) | 2.10 | 1.09E-03 | 4.30 | |

| Purine metabolism | spr0021 | Adenylosuccinate synthetase (purA) | 2.11 | 1.54E-05 | 4.31 |

| spr0053 | Phosphoribosylaminoimidazole carboxylase, catalytic subunit (purE) | 1.46 | 1.32E-03 | 2.75 | |

| spr0054 | Phosphoribosyl glucinamide formyltransferase (purK) | 1.33 | 3.12E-04 | 2.52 | |

| spr1109 | Formate-tetrahydrofolate ligase (fhs) | 1.07 | 7.59E-07 | 2.10 | |

| spr1128 | GMP reductase (guaC) | 1.01 | 2.20E-06 | 2.01 | |

| Hypothetical genes | spr0128 | Hypothetical protein | 1.75 | 3.26E-04 | 3.36 |

| spr1407 | Hypothetical protein | 1.66 | 1.45E-04 | 3.16 | |

| spr1760 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 1.12 | 1.73E-03 | 2.18 | |

| spr1761 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 1.18 | 9.78E-04 | 2.27 | |

| spr1857 | Hypothetical protein | 2.67 | |||

| spr1858 | Hypothetical protein | 1.72 | 2.79E-03 | 3.30 | |

| spr1859 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 2.46 | 9.51E-03 | 5.50 | |

| Riboflavin metabolism | spr0161 | Riboflavin synthase beta chain (ribE) | 1.08 | 9.07E-06 | 2.12 |

| spr0162 | Riboflavin biosynthesis; GTP-cyclohydrolase II (ribA) | 1.60 | 2.04E-07 | 3.03 | |

| spr0164 | Riboflavin biosynthese; a deaminase (ribD) | 1.53 | 1.12E-07 | 2.89 | |

| spr1017 | Macrolide efflux protein (mreA) | 2.73 | 2.97-E04 | 6.64 | |

| Other | spr0059 | Beta-galactosidase 3 (bgaC) | 1.01 | 2.31E-03 | 2.01 |

| spr0060 | Phosphotransferase system sugar-specific EIIB component | 1.37 | 6.01E-04 | 2.58 | |

| spr0561 | Cell wall-associated serine proteinase precursor PrtA (prtA) | 1.16 | 1.15E-04 | 2.23 | |

| spr1324 | Thiamine biosynthesis lipoprotein (apbE) | 1.17 | 8.63E-05 | 2.25 | |

| spr1408 | Formylmethionine deformylase (def) | 1.88 | 8.62E-05 | 3.69 | |

| spr1935 | Dihydroxyacid dehydratase (ilvD) | 1.73 | 3.32E-05 | 3.31 | |

| spr1945 | Choline binding protein (pcpA) | 1.47 | 9.96E-05 | 2.77 | |

| Hypothetical genes | spr1482 | Hypothetical protein | 1.22 | 1.56E-06 | 2.33 |

| spr1623 | Hypothetical protein | 1.82 | 3.30E-10 | 3.52 | |

| spr1624 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 1.91 | 9.22E-10 | 3.75 | |

| spr1625 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 1.75 | 1.60E-11 | 3.37 | |

| spr1626 | Hypothetical protein | 1.52 | 6.09E-07 | 2.87 | |

| spr1768 | Conserved hypothetical protein, related to Trp repressor binding protein | 1.11 | 8.90E-06 | 2.15 |

The ratio of the gene expression level in the ΔstkP mutant strain compared to that of the wild-type strain.

As an internal control, stkP transcripts were not detected from the ΔstkP mutant (decrease of 22-fold) compared to the presence of the parent strain (Table 1). stkP is located downstream of, and overlaps with, phpP, a gene coding for StkP cognate phosphatase (55). The presence of a transcriptional terminator following stkP suggested that stkP is the last gene in the operon (18). Thus, the polar effect resulting from stkP replacement is unlikely. Furthermore, the level of transcription from the phpP (spr1578) and orf-1576 genes, which flank stkP, remained unaffected in the ΔstkP mutant and its stkP+ parent, indicating a lack of polar effects on the surrounding genes.

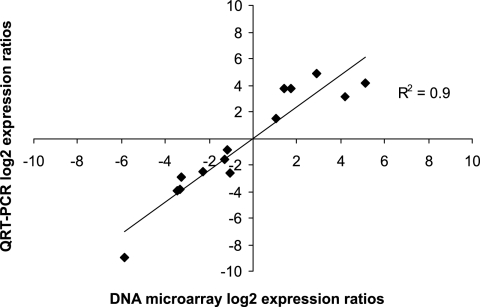

Validation of gene expression by qRT-PCR analysis.

The RT-PCR approach was chosen as an independent method to validate the microarray results. We quantified transcripts of selected genes by using the same RNA samples that were used for the microarray assays. Average data from at least two experimental replicates are shown in Table 3. In each instance, the qRT-PCR results correlated well (R2 = 0.9) with those obtained from the microarrays (Fig. 2). qRT-PCR assays provided a higher dynamic range for relative gene expression than did the DNA microarrays, as indicated for spr1057 as well as spr0857 (celB), spr1684 (fatD), spr1724 (ssbB), and spr1864 (cglA). Both microarray and qRT-PCR analysis showed that the expression levels of recA and ciaH are unaltered in the stkP mutant.

TABLE 3.

qRT-PCR confirmation of microarray data

| Gene product | Gene no. | Expression ratioa

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA microarray | Real-time PCR | ||

| Transcriptional regulator ComX1 | spr0013 | 18.6 | 16.9 |

| Hypothetical protein, LysM domain protein | spr0096 | −11.0 | −15.9 |

| Sensor histidine kinase CiaH | spr0708 | * | −1.6 |

| Competence protein CelB | spr0857 | 2.6 | 22.0 |

| Endo-beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase | spr0867 | −4.8 | −5.5 |

| ABC transporter substrate binding protein-iron transport | spr0934 | −2.2 | −1.8 |

| Conserved hypothetical protein, member of the hydrolase HAD-like family | spr1057 | −58.5 | −502.2 |

| Formate-tetrahydrofolate ligase | spr1109 | 2.1 | 2.1 |

| Carbamoylphosphate synthase (glutamine-hydrolyzing) light subunit | spr1154 | −2.4 | −3.0 |

| Conserved hypothetical protein, similar to hemolysin III | spr1320 | −10.2 | −15.7 |

| ABC transporter membrane-spanning permease-ferric iron transport | spr1684 | −2.1 | −10.6 |

| Single-stranded DNA binding protein SsbB | spr1724 | 3.3 | 23.6 |

| RecA protein | spr1757 | * | 1.6 |

| Competence protein CglA | spr1864 | 7.6 | 53.7 |

| General stress protein GSP-781 | spr2021 | −9.5 | −7.4 |

| Response regulator ComE | spr2041 | 34.7 | 30.1 |

The ratio of the gene expression level in the ΔstkP mutant strain compared to that of the wild-type strain indicating genes up- or down-regulated in the ΔstkP mutant strain.

, gene is not significantly regulated by StkP.

FIG. 2.

Correlations between gene expression levels determined by DNA microarray and qRT-PCR. The solid line is the linear regression line; the correlation coefficient is 0.9.

Functional classification of downregulated genes in ΔstkP mutant.

Apart from a few exceptions, genes encoding proteins potentially involved in the regulation of cell wall biosynthesis were most strongly repressed (Table 1). spr0096 (11-fold decrease) encodes a hypothetical protein containing a LysM domain, one of the most common protein modules in bacterial cell surface proteins. LysM occurs most often in cell wall-degrading enzymes, where it is believed to act to anchor the catalytic domains to their substrates (30). Several proteins that contain the domain, including staphylococcal immunoglobulin G binding proteins and Escherichia coli intimin, are involved in bacterial pathogenesis (3). lytB (fivefold) encodes glucosaminidase, which catalyzes the last step in cell wall division that disperses intact cells (17). It has been shown recently that lytB mutants exhibited a significantly reduced colonization of the nasopharynx but exhibited a behavior similar to that of the parental lytB+ strain when they were tested in a model of pneumococcus-induced sepsis (22).

A significant decrease of expression (10-fold) of spr2021 (pcsB) has been shown in microarray analysis and validated further by qRT-PCR. The pcsB homologues of Streptococcus mutans (11) and Streptococcus agalactiae (67) have been implicated in responses to general stress, but their functions remain unknown. pcsB mutants in both species of streptococcus were more sensitive to low pH, high osmotic pressure, and high temperature than was their pcsB+ parent strain (67, 68). A similar increase of sensitivity to elevated temperature, high osmolality, and pH was observed in an S. pneumoniae R6 derivative strain expressing less than half the normal PcsB amount (M. Winkler, personal communication). Unlike the case in S. mutans and S. agalactiae, PcsB is strictly essential in S. pneumoniae (51). It has been demonstrated that severe depletion of PcsB led to a rapid cessation of growth. Therefore, a model in which PcsB acts as a critical murein hydrolase that modulates cell wall biosynthesis has been proposed.

To test whether decreased resistance to stress conditions of the ΔstkP mutant resulted from low abundance of pcsB transcript, we constructed a merodiploid strain expressing an ectopic copy of the pcsB allele under the control of a fucose-inducible PfcsK promoter. No significant effect on either growth characteristics or stress resistance was observed when the ectopic expression of pcsB was induced with fucose over a wide range of inducer concentrations (data not shown). Therefore, it seems that the increased sensitivity of the stkP mutant to stress conditions is multifactorial, not simply dependent on the decreased level of pcsB expression.

Recent studies revealed that pcsB expression is positively regulated by the VicRK two-component system (52). VicRK is a homologue of the essential two-component system, which is highly conserved in and specific to the low-G+C-content gram-positive bacteria, where it is often designated YycFG based on its initial discovery in Bacillus subtilis (20). Both the yycF and yycG genes are required for viability. Conversely, in S. pneumoniae, only the response regulator vicR gene was found to be essential (32, 74), suggesting that VicR functions independently of sensor kinase VicK, possibly participating in signal transduction with another two-component system kinase. In a recent study performed by Ng et al. (53), binding sequences for VicR were determined by band shift and footprinting experiments. VicR bound to regions upstream of pcsB, pspA, spr0096, spr1875, and spr0709. The phosphorylation of VicR to VicR-P increased the apparent strength and changed the nature of binding to these regions.

A comparison of our microarray results with those obtained by Ng et al. (52, 53) shows that spr0096, spr0709, lytB, and pcsB genes were strongly downregulated in both the vicR and stkP isogenic mutants. No changes were observed in the expression of the vicRKX genes in the ΔstkP mutant compared to that in the stkP+ parent. Thus, the positive regulatory effect on the expression of spr0096, spr0709, lytB, and pcsB genes can be confined to direct interaction of StkP with VicR. This finding could suggest that in addition to its cognate kinase, VicK, the activity of the response regulator VicR can be modulated by StkP. Whether StkP influences the ability of VicR to bind DNA and/or regulate downstream transcription or affect the stability of VicR is currently being investigated. Recently, Rajagopal et al. (65) brought the first experimental evidence that direct cross talk between two different signaling systems exists.

The genes encoding proteins involved in pyrimidine de novo biosynthesis comprised the largest category, containing 10 genes that were coordinately downregulated by 2.4- to 5.2-fold. In contrast to a number of different gram-positive organisms, the pyrimidine biosynthesis genes are scattered on the chromosome of S. pneumoniae and are organized in five putative transcriptional units: pyrFpyrE, pyrDIIpyrD, pyrC, pyrP, and pyrRpyrBcarAcarB. The first gene in the pyrRpyrBcarAcarB operon is pyrR encoding a regulatory protein. In B. subtilis, regulation of the pyr operon occurs through a transcriptional attenuation mechanism in which PyrR promotes transcriptional termination at three attenuation regions in the operon when uridine nucleotide levels are high (34, 75). High levels of UMP stimulate PyrR to bind to a conserved sequence and secondary structure in the mRNA in each attenuation region called the antiantiterminator or the binding loop (73). Binding of PyrR to this sequence prevents the formation of an antiterminator stem-loop and allows a downstream ρ-independent transcription terminator to form, reducing the expression of downstream genes. When UMP levels are low, the RNA binding affinity of PyrR is reduced and the more stable antiterminator stem-loop is favored, leading to transcriptional read-through and expression of the downstream genes.

By analyzing the sequences of the upstream and intergenic regions of genes comprising the PyrR regulon in S. pneumoniae, we identified the highly conserved sequence motif 5′-ARUCCNGNGAGGYU-3′ in the pyrRpyrBcarAcarB mRNA leader, in the pyrBcarA intergenic region, and in the pyrFpyrE and pyrP leader sequences (data not shown). The secondary structures that may be formed by the RNA in these regions in S. pneumoniae are similar to the structures found in the RNA transcribed from the B. subtilis pyr operon. These findings suggest that the expression of the pyr genes of S. pneumoniae can be regulated by the same attenuator mechanism as that suggested for B. subtilis. The fact that all genes of the S. pneumoniae pyr regulon, including pyrR, are repressed in the stkP mutant could indicate that in addition to the attenuation mechanism, their expressions are regulated by an alternative mechanism. Collectively, these results suggest that the regulation of pyrimidine biosynthesis in S. pneumoniae involves multiple levels of control (i.e., transcriptional and posttranslational).

There were two- to fourfold decreases in the relative transcript amounts of several genes involved in DNA repair. Two of these, spr1055 and spr1054, coding for DNA uracil glycosylase (ung) and 8-oxodGTP nucleoside triphosphatase (mutX), respectively, are clustered with pyrC (see above). MutX of S. pneumoniae is a homologue of E. coli MutT, an antimutator protein (40). In addition, the expression of spr1317 (O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase ogt) and spr1660 (exodeoxyribonuclease exoA) was moderately affected (twofold decrease).

Decreased expression of a gene cluster, piuBCDA (spr1684-spr1687), containing the components of an iron uptake ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporter (also called a fat or pit1 operon) that is required for virulence (6, 7) was observed (2.8- to 4.7-fold decrease). This result was further validated by qRT-PCR, which showed even higher values for the change in expression for the first gene in the operon, spr1684 (fatD) (Table 3). In addition, there was a 2.2-fold reduction in spr0934 transcripts, a homologue of piaA. piaA is the first gene of a four-gene iron transport operon (Pit2) and has been identified as a ferrophore binding protein (7). Three gene clusters, pit, pia, and piu, each encoding four elements of an iron uptake ABC transporter, have been implicated in iron uptake by S. pneumoniae (6, 7).

To test the susceptibility to inhibition by streptonigrin, which can be used as an indirect indicator of intracellular iron concentration (5), we measured the zone of growth inhibition surrounding an antibiotic disk impregnated with 5 μg of streptonigrin on blood agar plates. Since no differences in zone size were observed for mutant and wild-type strains, we concluded that both strains have similar iron transport capacities (data not shown). This result is in agreement with the previous finding that the pia product is likely to be the dominant S. pneumoniae iron transporter during both in vitro and in vivo growth (7). Thus, the attenuated virulence of the stkP mutant strain cannot be attributed to the defect in iron transport.

Another functional category of repressed genes comprises those that mediate resistance to oxidative stress, including spr1322 and spr1495, encoding pyridoxine biosynthesis protein Pdx1 and thioredoxin-linked thiol peroxidase PsaD. Pdx1 has been reported as a singlet oxygen resistance protein (19), and it has been suggested that PsaD is a homologue of E. coli thiol peroxidase, which scavenges superoxide and peroxide ions (54).

In addition to the genes with experimentally defined functions, a large group of repressed genes coding for proteins with either unknown or putative functions were observed. The alteration in relative transcription of several of these genes was considerable, suggesting that they may function in the observed phenotypic properties. A notably large decrease for the spr1057-spr1056 cluster (59- and 9-fold, respectively) encoding conserved hypothetical polypeptides was detected. spr1057, the most strongly repressed gene (as high as 500-fold by qRT-PCR) in the stkP mutant, encodes a homologue of the haloacid dehalogenase (HAD)-like protein superfamily, which includes a variety of enzymes with different functions. Despite the fact that it is named after a dehalogenase, the vast majority of the known catalytic activities in the HAD family involve phosphoryl transfer (2). The few members of the family that have a defined function are associated with membrane transport, metabolism, signal transduction, and nucleic acid repair. The E. coli YjjG protein, a member of the HAD superfamily, exhibits a high phosphatase activity towards 5′-dTMP, 5′-dUMP, and 5′-UMP and might be involved in the pyrimidine substrate cycles (63). Further work is necessary to elucidate the function of the HAD protein in S. pneumoniae. Nevertheless, the extent and strength of its repression in the stkP mutant suggest that its expression can be completely inhibited. Indeed, a proteomic analysis of the wild-type and stkP strains demonstrated that mutant cells are depleted of Spr1057 protein (data not shown).

Among the other repressed hypothetical genes, we observed a substantial reduction (10-fold by microarrays and 15-fold by qRT-PCR) in the expression of the spr1320 gene encoding a putative second pneumococcal hemolysin that is distinct from pneumolysin. Spr1320 is a conserved protein in all streptococci as well as additional bacterial species and is similar to hemolysin III. It has been described as a lysin responsible for a beta-hemolytic effect in pneumococci (9); however, no data are available regarding its potential role in pathogenesis.

Inactivation of stkP leads to overexpression of competence genes.

The analysis of the induced genes in the stkP mutant showed that the majority of upregulated genes belong to the competence regulon (Table 2). This finding was surprising as it has been previously demonstrated that an stkP mutation effectively abolishes natural competence development (18). Furthermore, the S. pneumoniae strains were grown in CAT medium, in which the wild-type strain CP1015 fails to develop spontaneous competence. We selected these culture conditions to uncouple the regulatory effects of StkP on growth and physiology from those on competence. All the ComE-dependent genes (early com genes) described previously as key components of the competence regulatory cascade, including comCDE, comAB, comX, and comW (26, 33, 35, 36, 58), were strongly upregulated in the ΔstkP mutant (Table 2). These genes encode functions absolutely required for competence induction. A comparison of the induction ratios of the core early competence genes, including comCDE, comAB, comX, and comW, with those reported in previous reports (15, 61) suggested that the competence regulatory circuit is fully induced. Although there were differences in the amplitude of induction between particular surveys, these differences could be attributed to the distinct microarrays, variations in medium composition, and in the strains used.

In contrast, the levels of induction of σx-dependent genes (late competence genes) required for the process of DNA uptake, processing, and recombination were generally 10- to 20-fold lower than those reported previously (15, 61). In addition, several competence genes had transcript levels below the cutoff value of twofold, suggesting that their expression levels were not affected in the stkP mutant. These genes include celA, coiA, dalA, cclA, recA, cglC, cflA, and cflB. It has been experimentally demonstrated that these genes encode proteins whose functions are indispensable in efficient DNA binding, uptake, and recombination (8, 38, 46, 59, 61). Among these, the absence of recA induction was confirmed by qRT-PCR (Table 3). Previous studies have demonstrated that the recA gene is induced at competence (38, 57), and de novo synthesis of RecA molecules is absolutely required for full recombination proficiency during transformation (46, 61). recA is the second gene in a cinA-recA-dinF-lytA late operon and, in competent cells, is induced from the competence-inducible promoter located in front of cinA (Pcin). In noncompetent cells, recA is expressed from its own σA-type promoter (46). The competence-specific induction of recA (that is, expression from Pcin) accounts for 95% of the yield of transformants. Thus, we conclude that low basal level expression of recA and possibly other DNA uptake and processing genes could be a major factor contributing to the reduced rate of transformation in the stkP mutant strain.

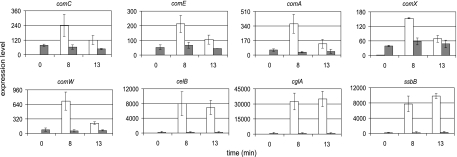

Responsiveness of competence genes to CSP induction in the wild-type and ΔstkP strains.

The results from our global transcription analysis showed that the “core” early competence genes are induced in the stkP mutant during mid-exponential growth. In order to address whether an observed increase of expression of selected competence genes in the stkP mutant corresponds to the levels of the fully induced com regulon, we quantified the mRNA levels in the CSP-induced and uninduced cultures of both wild-type and mutant strains. comC, comE, comA, comX, and comW were selected as representatives of early genes. Cultures of both strains were grown in parallel to an OD400 of 0.4 (the same conditions as cultures used for microarray analysis) and sampled immediately before and after the addition of CSP (250 ng ml−1) for the purification of RNA (see Materials and Methods). This dose of CSP was sufficient to induce full competence in the wild-type strain. To analyze the kinetics of the CSP response, samples were taken 8 and 13 min after CSP addition. As expected, in the wild-type strain, a low basal signal increase was observed for representatives of early genes (comC, comE, comA, comX, and comW) tested upon CSP treatment, reaching the maximum level at 8 min and then declining by 13 min (Fig. 3). This rapid response and sharp decline in mRNA levels are typical of what was previously reported for competence genes (1, 60, 69). In contrast, the level of the corresponding transcripts in the mutant strain, although significantly elevated, remained unaffected by the addition of CSP (Fig. 3). Transcription levels of the induced genes in the wild-type strain reached values two- to eightfold higher than those measured in the stkP mutant.

FIG. 3.

Competence genes expression determined by qRT-PCR. Relative levels of mRNA of selected competence genes before (time zero) and 8 min and 13 min after the addition of CSP to wild-type (open columns) and stkP mutant bacteria (gray columns). mRNA levels in both wild-type and mutant are expressed relative to uninduced wild-type levels. Data are representative of two separate experiments. The data shown are means and standard deviations (error bars) of at least three technical replicates.

Representatives of late competence genes, including cglA, celB, and ssbB, were analyzed in the same experimental setup. A large increase in transcript levels for these genes was observed upon CSP treatment in the wild-type cells at 8 min, reaching the expected maximum level at 13 min (Fig. 3). As before, the kinetics of late gene induction were in good agreement with those stated in previous reports (1, 15, 60, 61, 69). As observed with the early genes, the transcript levels of late competence genes were elevated and remained unaffected by CSP treatment in the stkP mutant. The induction amplitude of the late genes represented by celB, cglA, and ssbB showed a much higher increase (20- to 25-fold) (Fig. 3) relative to “induced” levels in the stkP background, suggesting that this increase of expression is likely not sufficient to derepress competence development. This result suggests that the reduced transformation efficiency in the stkP mutant is caused by weak induction of DNA uptake and processing genes. On the other hand, the elevated level of the competence regulon in the stkP mutant is sufficient for the increase of transformation frequency by a factor of 103 compared to that of the wild-type strain under conditions that repress competence development.

Competence development.

To exclude the possibility that the observed failure of stkP strain cells to respond to exogenous CSP may result from an occurrence of a transient postcompetence period, when cells remain refractory to CSP (43), we performed the analysis of transcript levels as well as transformation assays at a lower optical density (OD400 = 0.1). This density was selected because the refractory phase persists for about 1 to 1.5 generations after spontaneous as well as CSP-induced development of competence (12, 43). The cell counts at given optical densities corresponded to approximately 1.5 generations. The transcript level of the sampled genes was essentially the same as that in the cultures at a higher cell density, suggesting that the absence of a CSP response in the mutant strain is not a consequence of a refractory period (data not shown). Competence assays were performed with cultures of the wild-type and stkP mutant strains. Competence development was measured in cultures both induced by the addition of exogenous CSP and uninduced and grown in CAT medium, a broth which prevents Cp1015 from developing spontaneous competence. As expected, basal transformation efficiency was observed in the wild-type cultures in conditions that repressed competence development (<10−5%) (Table 4). In the isogenic stkP mutant strain, the yield of transformants attained a transformation efficiency ∼1,000-fold higher than that of the wild type. The addition of CSP to the wild-type culture resulted in a 105-fold increase in the transformation frequency (it reached 2.3%), whereas no change was observed in the stkP mutant strain. This result demonstrates that the transformation efficiency in the mutant strain is not affected by the addition of exogenous CSP. The transformation efficiencies of CSP-treated and untreated cells were similar to those obtained at an OD400 of 0.4 (Table 4). Thus, it seems plausible that the competence regulon is permanently induced; however, the degree of induction does not reach sufficient levels for full activation of the competence cascade. Thus, the results of the transformation assays are consistent with those of qRT-PCR and microarray analysis.

TABLE 4.

Transformation efficiencies of S. pneumoniae wild-type and ΔstkP mutant strains in the medium that did not allow natural competence development and after CSP treatmenta

| OD400 | S. pneumoniae strain | CSP inductionb | Total count (CFU ml−1 [107]) | Transformants (CFU ml−1 [104]) | Transformation efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | CP1015 | No | 4.85 ± 0.52 | <0.003 | <6.22E-05 ± 0.71E-05 |

| Yes | 4.95 ± 0.54 | 102.00 ± 26.23 | 2.04 ± 0.32 | ||

| CP1015ΔstkP | No | 4.20 ± 0.38 | 4.50 ± 0.53 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | |

| Yes | 3.80 ± 0.68 | 9.25 ± 0.82 | 0.25 ± 0.04 | ||

| 0.4 | CP1015 | No | 14.53 ± 0.64 | <0.003 | <2.07E-05 ± 0.09E-05 |

| Yes | 11.58 ± 0.73 | 264.10 ± 17.15 | 2.29 ± 0.28 | ||

| CP1015ΔstkP | No | 10.00 ± 0.37 | 7.33 ± 0.49 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | |

| Yes | 11.91 ± 0.66 | 2.27 ± 0.38 | 0.02 ± 0.0 |

Transformation efficiencies were calculated as the ratio of the viable counts on plates with and without rifampin (see Materials and Methods). Results are expressed as the mean counts (±standard deviations) from three independent experiments.

Competence induction with CSP at 250 ng ml−1.

Our finding that the basal-level expression of competence genes is increased and transformability is reduced is reminiscent of the phenotype reported for a particular S. pneumoniae mutant (24). This mutation, which is localized in the transcription terminator of the tRNAArg gene located immediately upstream of comCDE, was suggested to destabilize the terminator and to allow transcriptional read-through of comCDE (39). Contrary to expectation, an increased basal level expression of comCDE impeded both spontaneous and CSP-induced competence in S. pneumoniae. However, reduced competence and response to CSP can be bypassed either through the addition of synthetic CSP or by increasing CSP export capacity, e.g., overexpression of comAB (24). In contrast, the transformability of the stkP strain is unaffected by the addition of exogenous synthetic CSP. Evidently, the mechanism leading to an increased expression of competence genes in the stkP mutant is different, although its basis is at present unclear.

In summary, our microarray analysis of the transcription profile of a stkP mutant revealed that the posttranslational modification of an as-yet-unidentified target(s) affects the expression of many functionally different genes in S. pneumoniae. Nevertheless, considering the fact that the contribution of stkP to virulence varies with the different S. pneumoniae strains and the site of infection (18), it is very likely that the impact on the repertoire of genes regulated will be strain dependent. It is becoming increasingly clear that genes encoding signaling proteins make different contributions to gene expression depending on the genetic background of the parental strain (25).

The broad pleiotropic effect of the stkP mutation is noteworthy. One possible explanation is that some phenotypic properties of the mutant strain can be ascribed to the deregulation of an essential GlmM enzyme (55), resulting in so-far-unidentified, although envisaged, alterations in the cell wall biosynthesis. These perturbations could be reflected in some features of the mutant strain likely involving susceptibility to stress conditions. Apart from this possibility, StkP could assume a direct role, interacting with transcription machinery. However, as StkP lacks canonical DNA binding domains and as a result is unlikely to directly regulate transcription, the input signal must be transmitted through an effector molecule. Considering that this effect is exerted to many different gene categories involved in diverse cellular processes, the existence of a common factor mediating the transfer of signal to transcription machinery seems plausible. We hypothesize that the α-subunit of RNA polymerase is a candidate for such an effector. Our studies revealed that RpoA is a substrate of StkP either in vivo (55) or in vitro (unpublished results). Its covalent modification, particularly at the C-terminal domain (23), can contribute to the altered efficiency of transcription initiation by changing its affinity for promoters or transcription factors (70). The identification of the target amino acids that are phosphorylated will provide the grounds for further investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Grant Agency of Charles University (188/2004/B-BIO/PrF to L.S.), the Institute of Microbiology of the Czech Academy of Sciences (grant no. Z50200510-I050 to L.N. and Institutional Research Concept no. AV0Z50200510), and the Czech Science Foundation (204/07/P082 to L.N. and 204/02/1423 to P.B.). The purchase of the microarray processing equipment was supported in part by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (NAS course “Genome-wide Approaches to Understanding Bacterial Pathogenesis,” Prague, 9 September 2002 to 20 September 2002). The work of M.B. was supported by grant no. 1G46068 of the National Agency for Agricultural Research.

We thank Donald Morrison for valuable discussions. We also thank Malcolm Winkler for provision of the pcsB-complementing amplicon and Vladimír Kořínek for help with qRT-PCR. We are grateful to Elaine Allan for critically reading the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 6 April 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alloing, G., B. Martin, C. Granadel, and J. P. Claverys. 1998. Development of competence in Streptococcus pneumoniae: pheromone autoinduction and control of quorum sensing by the oligopeptide permease. Mol. Microbiol. 29:75-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aravind, L., and E. V. Koonin. 1998. The HD domain defines a new superfamily of metal-dependent phosphohydrolases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 23:469-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bateman, A., and M. Bycroft. 2000. The structure of a LysM domain from E. coli membrane-bound lytic murein transglycosylase D (MltD). J. Mol. Biol. 299:1113-1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boitel, B., M. Ortiz-Lombardia, R. Duran, F. Pompeo, S. T. Cole, C. Cervenansky, and P. M. Alzari. 2003. PknB kinase activity is regulated by phosphorylation in two Thr residues and dephosphorylation by PstP, the cognate phospho-Ser/Thr phosphatase, in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 49:1493-1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolzán, A. D., and M. S. Bianchi. 2001. Genotoxicity of streptonigrin: a review. Mutat. Res. 488:25-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown, J. S., S. M. Gilliland, and D. W. Holden. 2001. A Streptococcus pneumoniae pathogenicity island encoding an ABC transporter involved in iron uptake and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 40:572-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown, J. S., S. M. Gilliland, J. Ruiz-Albert, and D. W. Holden. 2002. Characterization of Pit, a Streptococcus pneumoniae iron uptake ABC transporter. Infect. Immun. 70:4389-4398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell, E. A., S. Y. Choi, and H. R. Masure. 1998. A competence regulon in Streptococcus pneumoniae revealed by genomic analysis. Mol. Microbiol. 27:929-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canvin, J. R., J. C. Paton, G. J. Boulnois, P. W. Andrew, and T. J. Mitchell. 1997. Streptococcus pneumoniae produces a second haemolysin that is distinct from pneumolysin. Microb. Pathog. 22:129-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng, Q., E. A. Campbell, A. M. Naughton, S. Johnson, and H. R. Masure. 1997. The com locus controls genetic transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 23:683-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chia, J. S., Y. Y. Lee, P. T. Huang, and J. Y. Chen. 2001. Identification of stress-responsive genes in Streptococcus mutans by differential display reverse transcription-PCR. Infect. Immun. 69:2493-2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Claverys, J. P., and L. S. Havarstein. 2002. Extracellular-peptide control of competence for genetic transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Front. Biosci. 7:d1798-d1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cozzone, A. J. 2005. Role of protein phosphorylation on serine/threonine and tyrosine in the virulence of bacterial pathogens. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 9:198-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curry, J. M., R. Whalan, D. M. Hunt, K. Gohil, M. Strom, L. Rickman, M. J. Colston, S. J. Smerdon, and R. S. Buxton. 2005. An ABC transporter containing a forkhead-associated domain interacts with a serine-threonine protein kinase and is required for growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Infect. Immun. 73:4471-4477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dagkessamanskaia, A., M. Moscoso, V. Henard, S. Guiral, K. Overweg, M. Reuter, B. Martin, J. Wells, and J. P. Claverys. 2004. Interconnection of competence, stress and CiaR regulons in Streptococcus pneumoniae: competence triggers stationary phase autolysis of ciaR mutant cells. Mol. Microbiol. 51:1071-1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dasgupta, A., P. Datta, M. Kundu, and J. Basu. 2006. The serine/threonine kinase PknB of Mycobacterium tuberculosis phosphorylates PBPA, a penicillin-binding protein required for cell division. Microbiology 152:493-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Las Rivas, B., J. L. Garcia, R. Lopez, and P. Garcia. 2002. Purification and polar localization of pneumococcal LytB, a putative endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase: the chain-dispersing murein hydrolase. J. Bacteriol. 184:4988-5000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Echenique, J., A. Kadioglu, S. Romao, P. W. Andrew, and M. C. Trombe. 2004. Protein serine/threonine kinase StkP positively controls virulence and competence in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 72:2434-2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ehrenshaft, M., P. Bilski, M. Y. Li, C. F. Chignell, and M. E. Daub. 1999. A highly conserved sequence is a novel gene involved in de novo vitamin B6 biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:9374-9378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fabret, C., and J. A. Hoch. 1998. A two-component signal transduction system essential for growth of Bacillus subtilis: implications for anti-infective therapy. J. Bacteriol. 180:6375-6383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galyov, E. E., S. Hakansson, A. Forsberg, and H. Wolf-Watz. 1993. A secreted protein kinase of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is an indispensable virulence determinant. Nature 361:730-732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gosink, K. K., E. R. Mann, C. Guglielmo, E. I. Tuomanen, and H. R. Masure. 2000. Role of novel choline binding proteins in virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 68:5690-5695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gourse, R. L., W. Ross, and T. Gaal. 2000. UPs and downs in bacterial transcription initiation: the role of the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase in promoter recognition. Mol. Microbiol. 37:687-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guiral, S., V. Henard, C. Granadel, B. Martin, and J. P. Claverys. 2006. Inhibition of competence development in Streptococcus pneumoniae by increased basal-level expression of the ComDE two-component regulatory system. Microbiology 152:323-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hendriksen, W. T., N. Silva, H. J. Bootsma, C. E. Blue, G. K. Paterson, A. R. Kerr, A. de Jong, O. P. Kuipers, P. W. Hermans, and T. J. Mitchell. 2007. Regulation of gene expression in Streptococcus pneumoniae by response regulator 09 is strain dependent. J. Bacteriol. 189:1382-1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hui, F. M., L. Zhou, and D. A. Morrison. 1995. Competence for genetic transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae: organization of a regulatory locus with homology to two lactococcin A secretion genes. Gene 153:25-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hussain, H., P. Branny, and E. Allan. 2006. A eukaryotic-type serine/threonine protein kinase is required for biofilm formation, genetic competence, and acid resistance in Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 188:1628-1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jin, H., and V. Pancholi. 2006. Identification and biochemical characterization of a eukaryotic-type serine/threonine kinase and its cognate phosphatase in Streptococcus pyogenes: their biological functions and substrate identification. J. Mol. Biol. 357:1351-1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jolly, L., F. Pompeo, J. van Heijenoort, F. Fassy, and D. Mengin-Lecreulx. 2000. Autophosphorylation of phosphoglucosamine mutase from Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 182:1280-1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joris, B., S. Englebert, C. P. Chu, R. Kariyama, L. Daneo-Moore, G. D. Shockman, and J. M. Ghuysen. 1992. Modular design of the Enterococcus hirae muramidase-2 and Streptococcus faecalis autolysin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 70:257-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kang, C. M., D. W. Abbott, S. T. Park, C. C. Dascher, L. C. Cantley, and R. N. Husson. 2005. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis serine/threonine kinases PknA and PknB: substrate identification and regulation of cell shape. Genes Dev. 19:1692-1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lange, R., C. Wagner, A. de Saizieu, N. Flint, J. Molnos, M. Stieger, P. Caspers, M. Kamber, W. Keck, and K. E. Amrein. 1999. Domain organization and molecular characterization of 13 two-component systems identified by genome sequencing of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Gene 237:223-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee, M. S., and D. A. Morrison. 1999. Identification of a new regulator in Streptococcus pneumoniae linking quorum sensing to competence for genetic transformation. J. Bacteriol. 181:5004-5016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu, Y., and R. L. Switzer. 1996. Evidence that the Bacillus subtilis pyrimidine regulatory protein PyrR acts by binding to pyr mRNA at three sites in vivo. J. Bacteriol. 178:5806-5809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luo, P., H. Li, and D. A. Morrison. 2003. ComX is a unique link between multiple quorum sensing outputs and competence in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 50:623-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luo, P., and D. A. Morrison. 2003. Transient association of an alternative sigma factor, ComX, with RNA polymerase during the period of competence for genetic transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 185:349-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Madec, E., A. Laszkiewicz, A. Iwanicki, M. Obuchowski, and S. Seror. 2002. Characterization of a membrane-linked Ser/Thr protein kinase in Bacillus subtilis, implicated in developmental processes. Mol. Microbiol. 46:571-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin, B., P. Garcia, M. P. Castanie, B. Glise, and J. P. Claverys. 1995. The recA gene of Streptococcus pneumoniae is part of a competence-induced operon and controls an SOS regulon. Dev. Biol. Stand. 85:293-300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martin, B., M. Prudhomme, G. Alloing, C. Granadel, and J. P. Claverys. 2000. Cross-regulation of competence pheromone production and export in the early control of transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 38:867-878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Méjean, V., C. Salles, L. C. Bullions, M. J. Bessman, and J. P. Claverys. 1994. Characterization of the mutX gene of Streptococcus pneumoniae as a homologue of Escherichia coli mutT, and tentative definition of a catalytic domain of the dGTP pyrophosphohydrolases. Mol. Microbiol. 11:323-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mengin-Lecreulx, D., and J. van Heijenoort. 1996. Characterization of the essential gene glmM encoding phosphoglucosamine mutase in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 271:32-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Molle, V., L. Kremer, C. Girard-Blanc, G. S. Besra, A. J. Cozzone, and J. F. Prost. 2003. An FHA phosphoprotein recognition domain mediates protein EmbR phosphorylation by PknH, a Ser/Thr protein kinase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochemistry 42:15300-15309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morrison, D. A. 1997. Streptococcal competence for genetic transformation: regulation by peptide pheromones. Microb. Drug Resist. 3:27-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morrison, D. A., S. A. Lacks, W. R. Guild, and J. M. Hageman. 1983. Isolation and characterization of three new classes of transformation-deficient mutants of Streptococcus pneumoniae that are defective in DNA transport and genetic recombination. J. Bacteriol. 156:281-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morrison, D. A., M. C. Trombe, M. K. Hayden, G. A. Waszak, and J. D. Chen. 1984. Isolation of transformation-deficient Streptococcus pneumoniae mutants defective in control of competence, using insertion-duplication mutagenesis with the erythromycin resistance determinant of pAMβ1. J. Bacteriol. 159:870-876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mortier-Barrière, I., A. de Saizieu, J. P. Claverys, and B. Martin. 1998. Competence-specific induction of recA is required for full recombination proficiency during transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 27:159-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nádvorník, R., T. Vomastek, J. Janecek, Z. Technikova, and P. Branny. 1999. Pkg2, a novel transmembrane protein Ser/Thr kinase of Streptomyces granaticolor. J. Bacteriol. 181:15-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nariya, H., and S. Inouye. 2002. Activation of 6-phosphofructokinase via phosphorylation by Pkn4, a protein Ser/Thr kinase of Myxococcus xanthus. Mol. Microbiol. 46:1353-1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nariya, H., and S. Inouye. 2005. Modulating factors for the Pkn4 kinase cascade in regulating 6-phosphofructokinase in Myxococcus xanthus. Mol. Microbiol. 56:1314-1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Neu, J. M., S. V. MacMillan, J. R. Nodwell, and G. D. Wright. 2002. StoPK-1, a serine/threonine protein kinase from the glycopeptide antibiotic producer Streptomyces toyocaensis NRRL 15009, affects oxidative stress response. Mol. Microbiol. 44:417-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ng, W. L., K. M. Kazmierczak, and M. E. Winkler. 2004. Defective cell wall synthesis in Streptococcus pneumoniae R6 depleted for the essential PcsB putative murein hydrolase or the VicR (YycF) response regulator. Mol. Microbiol. 53:1161-1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ng, W. L., G. T. Robertson, K. M. Kazmierczak, J. Zhao, R. Gilmour, and M. E. Winkler. 2003. Constitutive expression of PcsB suppresses the requirement for the essential VicR (YycF) response regulator in Streptococcus pneumoniae R6. Mol. Microbiol. 50:1647-1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ng, W. L., H. C. Tsui, and M. E. Winkler. 2005. Regulation of the pspA virulence factor and essential pcsB murein biosynthetic genes by the phosphorylated VicR (YycF) response regulator in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 187:7444-7459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Novak, R., J. S. Braun, E. Charpentier, and E. Tuomanen. 1998. Penicillin tolerance genes of Streptococcus pneumoniae: the ABC-type manganese permease complex Psa. Mol. Microbiol. 29:1285-1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nováková, L., L. Saskova, P. Pallova, J. Janecek, J. Novotna, A. Ulrych, J. Echenique, M. C. Trombe, and P. Branny. 2005. Characterization of a eukaryotic type serine/threonine protein kinase and protein phosphatase of Streptococcus pneumoniae and identification of kinase substrates. FEBS J. 272:1243-1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oggioni, M. R., C. Trappetti, A. Kadioglu, M. Cassone, F. Iannelli, S. Ricci, P. W. Andrew, and G. Pozzi. 2006. Switch from planktonic to sessile life: a major event in pneumococcal pathogenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 61:1196-1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pearce, B. J., A. M. Naughton, E. A. Campbell, and H. R. Masure. 1995. The rec locus, a competence-induced operon in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 177:86-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pestova, E. V., L. S. Havarstein, and D. A. Morrison. 1996. Regulation of competence for genetic transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae by an auto-induced peptide pheromone and a two-component regulatory system. Mol. Microbiol. 21:853-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pestova, E. V., and D. A. Morrison. 1998. Isolation and characterization of three Streptococcus pneumoniae transformation-specific loci by use of a lacZ reporter insertion vector. J. Bacteriol. 180:2701-2710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Peterson, S., R. T. Cline, H. Tettelin, V. Sharov, and D. A. Morrison. 2000. Gene expression analysis of the Streptococcus pneumoniae competence regulons by use of DNA microarrays. J. Bacteriol. 182:6192-6202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Peterson, S. N., C. K. Sung, R. Cline, B. V. Desai, E. C. Snesrud, P. Luo, J. Walling, H. Li, M. Mintz, G. Tsegaye, P. C. Burr, Y. Do, S. Ahn, J. Gilbert, R. D. Fleischmann, and D. A. Morrison. 2004. Identification of competence pheromone responsive genes in Streptococcus pneumoniae by use of DNA microarrays. Mol. Microbiol. 51:1051-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pfaffl, M. W. 2001. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Proudfoot, M., E. Kuznetsova, G. Brown, N. N. Rao, M. Kitagawa, H. Mori, A. Savchenko, and A. F. Yakunin. 2004. General enzymatic screens identify three new nucleotidases in Escherichia coli. Biochemical characterization of SurE, YfbR, and YjjG. J. Biol. Chem. 279:54687-54694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rajagopal, L., A. Clancy, and C. E. Rubens. 2003. A eukaryotic type serine/threonine kinase and phosphatase in Streptococcus agalactiae reversibly phosphorylate an inorganic pyrophosphatase and affect growth, cell segregation, and virulence. J. Biol. Chem. 278:14429-14441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rajagopal, L., A. Vo, A. Silvestroni, and C. E. Rubens. 2006. Regulation of cytotoxin expression by converging eukaryotic-type and two-component signalling mechanisms in Streptococcus agalactiae. Mol. Microbiol. 62:941-957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]