Abstract

Regulation of the trans-plasma membrane pH gradient is an important part of plant responses to several hormonal and environmental cues, including auxin, blue light, and fungal elicitors. However, little is known about the signaling components that mediate this regulation. Here, we report that an Arabidopsis thaliana Ser/Thr protein kinase, PKS5, is a negative regulator of the plasma membrane proton pump (PM H+-ATPase). Loss-of-function pks5 mutant plants are more tolerant of high external pH due to extrusion of protons to the extracellular space. PKS5 phosphorylates the PM H+-ATPase AHA2 at a novel site, Ser-931, in the C-terminal regulatory domain. Phosphorylation at this site inhibits interaction between the PM H+-ATPase and an activating 14-3-3 protein in a yeast expression system. We show that PKS5 interacts with the calcium binding protein SCaBP1 and that high external pH can trigger an increase in the concentration of cytosolic-free calcium. These results suggest that PKS5 is part of a calcium-signaling pathway mediating PM H+-ATPase regulation.

INTRODUCTION

A critical feature distinguishing plants from animals is that plants are sessile and thus have to cope with numerous environmental challenges. For example, plant roots are exposed to soil solutions that are constantly changing in pH as well as in the concentrations of mineral nutrients and toxic ions. Proton translocating ATPases in the plasma membrane (PM H+-ATPases) of plant cells establish the pH and membrane potential gradients across the plasma membrane (Palmgren, 2001). In plants, a number of factors, including blue light and fungal elicitors, have been shown to elicit changes in cellular pH by regulating the PM H+-ATPases (Marre, 1979; Spalding and Cosgrove, 1992; Kinoshita and Shimazaki, 1999). It has been shown that PM H+-ATPase is subject to in vivo phosphorylation (Schaller and Sussman, 1988), and recently it has been demonstrated that activation of the PM H+-ATPases by phosphorylation plays an important role in the response to, for example, blue light (Kinoshita and Shimazaki, 1999) and elevated levels of aluminum (Shen et al., 2005). Acidification of the cell wall is an important part of the growth-promoting effect of the phytohormone auxin (Rayle and Cleland, 1992), and auxin is known to affect the activity of the PM H+-ATPase (Hager et al., 1991; Frias et al., 1996), although the signaling components that mediate the effect of auxin on PM H+-ATPase are unknown.

The C terminus of the plant PM H+-ATPase includes ∼100 residues and serves as an autoinhibitory domain to inhibit the activity of the enzyme (Palmgren et al., 1991). The penultimate residue in the regulatory C-terminal domain of the PM H+-ATPase is phosphorylated in vivo (Olsson et al., 1998) and within seconds of exposure to blue light (Kinoshita and Shimazaki, 1999). Phosphorylation of this residue, Thr-947 in AHA2, an Arabidopsis thaliana isoform of the PM H+-ATPase, generates a binding site for a regulatory 14-3-3 protein (Fuglsang et al., 1999; Svennelid et al., 1999; Maudoux et al., 2000). The phosphorylation-dependent promotion of 14-3-3 binding results in displacement of the C-terminal constraint, leading to activation of pump activity (reviewed in Palmgren, 2001). The activated protein complex consists of six phosphorylated PM H+-ATPase molecules assembled in a hexameric structure together with six 14-3-3 molecules (Kanczewska et al., 2005). The protein kinase responsible for the phosphorylation of Thr-947 has not yet been identified.

Several lines of evidence point toward the involvement of more than one protein kinase in the regulation of the PM H+-ATPases. A phosphorylated Ser is present in the C-terminal region of a guard cell PM H+-ATPase (Kinoshita and Shimazaki, 1999). In addition, a large-scale mass spectrometric study of phosphorylated Arabidopsis PM proteins revealed that in addition to Thr-947, at least two phosphorylation sites involving Ser are present within the regulatory C terminus of AHA2 (Ser-899 and Ser-904; Nühse et al., 2004). Several of the putative phosphorylation sites are well conserved within the plant PM H+-ATPases, which further supports a potentially important role for these residues.

The physiological importance of phosphorylation of the PM H+-ATPase at alternative sites is only beginning to be elucidated. In response to blue light, the C-terminal domain is phosphorylated at a Ser residue (Kinoshita and Shimazaki, 1999). A synthetic phosphopeptide derived from the C-terminal regulatory domain of PM H+-ATPase and phosphorylated at Ser-933 (corresponding to Ser-931 in AHA2) was found to suppress the blue light–induced increase in PM H+-ATPase activity (Kinoshita and Shimazaki, 2002). The addition of this phosphopeptide did not affect the binding of 14-3-3 protein or the phosphorylation levels of the PM H+-ATPase, which led the authors to suggest that the peptide could be part of a pump autoinhibitory region. In response to fungal elicitors, the PM H+-ATPase is inhibited following phosphorylation by a Ca2+-dependent protein kinase (CDPK; Lino et al., 1998) and reactivated by dephosphorylation (Xing et al., 1996). This response to phosphorylation and dephosphorylation is functionally opposite to pump activation following phosphorylation of Thr-947. A CDPK phosphorylates a recombinant fusion protein containing 66 amino acid residues derived from the C-terminal domain of the tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) PM H+-ATPase isoform PMA2 (Rutschmann et al., 2002). Recently, Yu et al. (2006) reported a phosphorylation-dependent activation of the PM H+-ATPase by an abscisic acid (ABA)–stimulated CDPK. A rice (Oryza sativa) CDPK phosphorylates the rice PM H+-ATPase OSA1 in vitro on a residue corresponding to Thr-861 in AHA2 (Ookura et al., 2005).

Calcium (Ca2+) is a ubiquitous second messenger in plant cells. Hormones like ABA and environmental stresses, including salt stress, drought, and cold, have been shown to trigger changes in the concentration of cytoplasmic free Ca2+ (Sanders et al., 1999; Knight, 2000). During salt stress in Arabidopsis, the Ca2+ sensor Salt Overly Sensitive3 (SOS3) binds to and activates the Ser/Thr protein kinase SOS2 (Liu and Zhu, 1998; Halfter et al., 2000). The Ca2+-SOS3-SOS2 complex has been shown to phosphorylate and activate the Na+/H+ antiporter SOS1, resulting in regulation of Na+ homeostasis and salt tolerance (Zhu, 2002).

The Arabidopsis genome encodes a family of 10 SOS3-like putative Ca2+ sensors (SCaBPs/CBLs) and 25 SOS2-like protein kinases (PKS/CIPKs) (Guo et al., 2001; Kolukisaoglu et al., 2004). Several of these have been found to be associated with detergent-insoluble microdomains of the PM, so-called rafts that are also enriched in PM H+-ATPase (Shahollari et al., 2004). In this study, we investigated the function and mechanism of action of one SOS2-like protein kinase, PKS5 (CIPK11). We found that loss-of-function mutants of PKS5 are resistant to high pH in the external medium. We show that PKS5 negatively regulates the activity of the PM H+-ATPase and that PKS5 phosphorylates one of the PM H+-ATPases, AHA2, at a novel site, Ser-931, in the C-terminal regulatory domain. This phosphorylation abolishes the interaction with an activating 14-3-3 protein. These results suggest that PKS5 is a regulator in a novel Ca2+ signaling pathway controlling PM H+-ATPase activity and extracellular acidification.

RESULTS

PKS5 RNA Interference Lines Are More Tolerant to High External pH

To identify protein kinases putatively involved in regulation of the major primary plant ion pump, the plant PM H+-ATPase, we used RNA interference (RNAi) to silence the expression of members of the PKS family. A member of this family, SOS2, has previously been shown to regulate plant plasma membrane transport proteins (Qiu et al., 2002; Cheng et al., 2004). We expected that altered activity levels of the PM H+-ATPase would affect the ability of the plant to tolerate conditions of extreme pH alterations in the growth medium. When the medium pH is alkaline, it is difficult for root cells to establish a steep proton gradient to support nutrient uptake. In addition, the solubility of some nutrients, such as iron, is reduced at an alkaline pH.

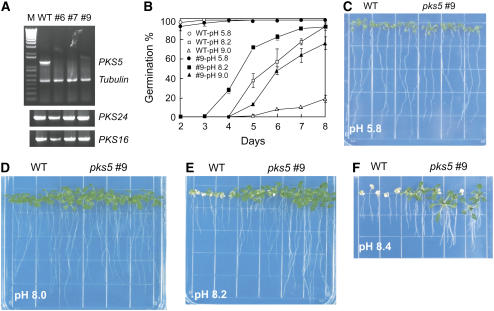

RNAi silencing of several members of the PKS family did not result in phenotypic alterations under alkaline conditions, but an exception was found with PKS5. After transformation with a PKS5 RNAi construct, PKS5 gene expression was examined in lines from three independent Arabidopsis transformants by RT-PCR (Figure 1A, top panel); PKS5 expression was not detectable in any of the lines. Amplification of Tubulin in these same reactions resulted in similar amounts of product in both wild-type and the RNAi lines, providing an internal control (Figure 1A, top panel). When cDNA from the same lines was used as a template for RT-PCR using primers corresponding to two genes closely related to PKS5 (PKS24/CIPK14 and PKS16/CIPK2), products were amplified, suggesting that silencing was specific for PKS5 (Figure 1A, middle and bottom panels).

Figure 1.

PKS5 RNAi Plants Are More Tolerant to High External pH.

(A) PKS5 expression is silenced in the PKS5 RNAi lines. Products of RT-PCR using DNA from wild-type Arabidopsis, three independent PKS5 RNAi lines (pks5#6, pks5#7, and pks5#9), and PKS5-specific primers (top panel). Tubulin primers were included in the PCR reactions as an internal control. RT-PCR with PKS24 and PKS16 gene-specific primers (bottom panels). M, molecular size markers.

(B) to (F) PKS5 RNAi line pks5#9 is more tolerant to high external pH during germination and growth. Wild-type and pks5#9 seeds were germinated on vertical MS agar plates at pH 5.8, 8.2, or 9.0. Ratios of seed germination over time as a percentage of the total number of seeds planted are shown for the different treatments ([B], means ± sd, n = 3). Four-day-old wild-type and pks5#9 seedlings, germinated on MS media at pH 5.8, were transferred (day 4) to MS media at pH 5.8 (C), 8.0 (D), 8.2 (E), or 8.4 (F). Images were taken 2 weeks after seedling transfer.

Twelve individual PKS5 RNAi lines (T2) were tested for seed germination and seedling growth as a function of media pH, and five lines showed increased tolerance to high external pH. One T3 homozygous line (pks5#9) was used for subsequent studies. Both wild-type and pks5#9 seeds germinated well at pH 5.8 (Figure 1B). By contrast, at pH 8.2, wild-type seeds suffered, but pks5#9 seeds managed relatively well (Figure 1B). This difference was even more pronounced at pH 9.0, where 70% of pks5#9 seeds germinated compared with <20% of the wild-type seeds (Figure 1B).

To examine the response of seedlings to high external pH, 4-d-old wild-type and pks5#9 seedlings that had been grown on medium at pH 5.8 were transferred to medium at pH 5.8, 8.0, 8.2, or 8.4. The growth of wild-type seedlings was completely inhibited on medium at pH 8.4, but pks5#9 seedlings continued to grow (Figure 1F). The tolerance of pks5#9 plants to high external pH was observed in a narrow window between pH 8.0 and 8.4. At lower pH values in the media, pks5#9 plants showed no significant difference in root growth when compared with the wild type.

The PKS5 RNAi lines were examined for seedling responses to ABA and various stresses, such as drought, salt, cold, extreme pH, and high concentrations of glucose. We did not observe any phenotypic aberrations in the RNAi lines under these treatments except the one observed in response to high pH.

T-DNA Knockout and Ethyl Methanesulfonate Alleles of pks5 Have Increased Tolerance to High External pH

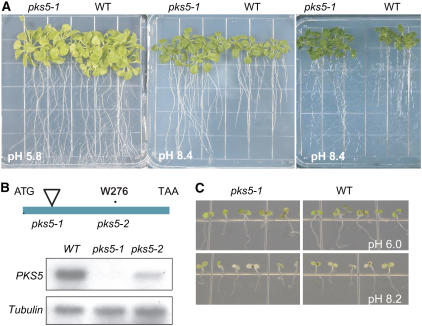

A T-DNA insertion line defective in PKS5 (SALK_108074) was later obtained, and homozygous mutant plants were identified by PCR using primers specific to the T-DNA left border and PKS5, respectively. The T-DNA had inserted 456 bp downstream of the predicted ATG start site of PKS5 (At2g30360) (Figure 2B). RNA gel blot analysis showed that PKS5 transcript was absent in the T-DNA insertion mutant (Figure 2B, middle panel). Eight ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS) alleles of pks5 were also obtained via TILLING (Greene et al., 2003; http://tilling.fhcrc.org:9366). One of the EMS alleles, in which a single G-to-A mutation was found in the PKS5 coding sequence and resulted in the substitution of Trp-276 by a premature stop codon, was also tested in this study (Figure 2A). Six-day-old seedlings from the pks5 T-DNA line (pks5-1) and the TILLING line (pks5-2) were exposed to medium at high external pH (8.4). As was seen with the PKS5 RNAi lines, these mutants were more resistant to high external pH (Figure 2A) than wild-type plants. Chlorosis at this stage was not as pronounced as with younger seedlings (Figures 1E and 1F). Table 1 summarizes the responses of the PKS5 T-DNA and EMS mutants and an RNAi line to high external pH. All of the pks5 mutants and RNAi plants were more resistant to high external pH for both survival and root growth.

Figure 2.

T-DNA Insertion and EMS pks5 Mutants Have a Similar Phenotype to That Found in the PKS5 RNAi Line.

(A) and (B) Six-day-old wild-type and pks5 seedlings, germinated on MS media pH 5.8, were transferred to MS media at pH 5.8 ([A], left panel) and 8.4 ([A], center and right panels). All images were taken 2 weeks after seedling transfer. The positions of the T-DNA insertion (pks5-1) and the premature stop codon (pks5-2) are indicated ([B], top panel). RNA gel blot analysis showed that the PKS5 transcript was undetectable in the pks5-1 mutant ([B], middle panel).

(C) Seedlings (4 d old) were transferred to plates buffered with Bicine to pH 8.2. Control plates were adjusted to pH 6.5 using the same buffer. Images were taken 3 d after seedling transfer.

Table 1.

Survival Rate and Root Growth of pks5 Mutants and RNAi Seedlings in Response to Treatment with High External pH

| Survival Rate at pH 8.4

|

Root Growth (cm)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survival (No. of Plants) | Total No. of Plants | Survival Rate (%) | pH 5.7 | pH 8.4 | Relative Growth (%) | |

| Wild type | 66 | 212 | 32.1 | 6.23 ± 0.52 | 1.23 ± 0.45 | 19.7 |

| pks5-1 | 162 | 256 | 63.3 | 6.32 ± 0.43 | 3.13 ± 0.56 | 49.5 |

| pks5-2 | 170 | 286 | 59.4 | 6.44 ± 0.78 | 3.24 ± 0.79 | 42.2 |

| pks5#9 | 153 | 240 | 63.8 | 6.35 ± 0.46 | 3.67 ± 0.64 | 57.8 |

While the response of the pks5 mutants and RNAi lines to high external pH was somewhat variable under the conditions used, the experiments were repeated independently 10 times and showed significantly increased tolerance of the plants to high external pH. Variability in some of the experiments was likely due to the narrow range of the pH phenotype and physiological condition of the seedlings under treatment.

A pH gradient (ΔpH; acidic on the outside) is required for solute uptake through proton-coupled secondary active transporters. Therefore, the increased ability of pks5 mutants to grow at high pH could be due to an increased extrusion of protons from the cell, leading to local acidification of the rhizosphere. To inhibit the formation of such an acidic root microenvironment, we grew plants on plates buffered at pH 8.2 (Figure 2C). Under these conditions, the pks5-1 mutant had the same poor growth as wild-type plants. Both the wild type and the pks mutants grew well when the root exterior was buffered at pH 6.5. This led us to conclude that pks5 mutant plants do not tolerate alkaline pH as such but rather have an improved capacity for medium acidification.

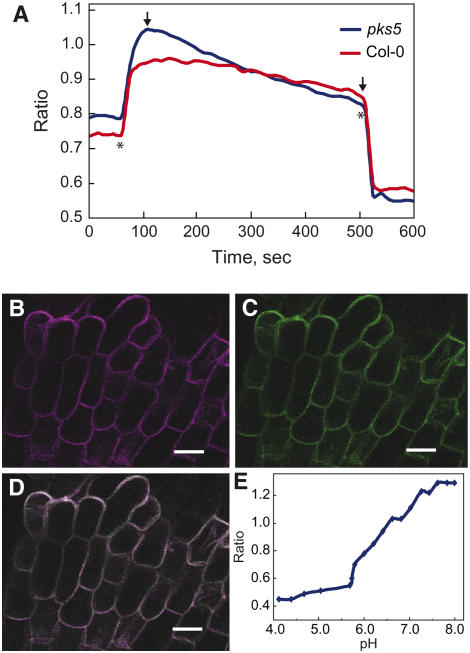

Proton Secretion Is Increased in Roots of pks5 Mutants

To directly measure changes in proton extrusion as a function of changing environmental pH, we incubated roots with the pH-sensitive ratiometric probe D-1950. This dextran-conjugated membrane-impermeable dye (pKa = 6.4) reports pH changes between pH 5.0 and 8.0 (Figure 3E). In the upper region of the root where root hairs emerge abundantly, the dye was distributed evenly in the apoplastic cell wall region but did not enter cells (Figures 3B to 3D). Single plantlets were incubated at a medium pH of 5.8, and subsequently pH was increased to pH 8.4. The probe immediately reported medium alkalization (Figure 3A); consequently, the pH of the apoplast slowly decreased with time (Figure 3A). The steeper downwards slope for pks5-1 plants compared with the wild type is evidence for a higher rate of proton extrusion in response to alkalization. No significant difference in extracellular acidification was observed between pks5-1 and wild-type plants grown at pH 5.8.

Figure 3.

pH Ratio Imaging in the Apoplast of Columbia-0 and pks5-1 Roots.

(A) Mean value ratio curve for mutant (n = 13) and wild-type (n = 10) plants. Ratios were calculated as fluorescein/rhodamin fluorescence levels. The slope in each experiment was calculated and used in one-way analysis of variance, which showed wild-type and mutant plants to react significantly differently on raised pH regimes. Asterisks show where pH regimes were shifted upwards to pH 8.4 and downwards to pH 5.8, respectively. Arrows indicate the two outer points used to define the area from where the slope was calculated.

(B) Fluorescence in the fluorescein channel colored in pseudo color.

(C) Fluorescence in the rhodamin channel colored in pseudo color.

(D) Overlay of the fluorescein and rhodamin channels colored in pseudo colors. Bars = 20 μm in (B) to (D).

(E) pH calibration curve showing the response of the probe D-1950 at different pH regimes.

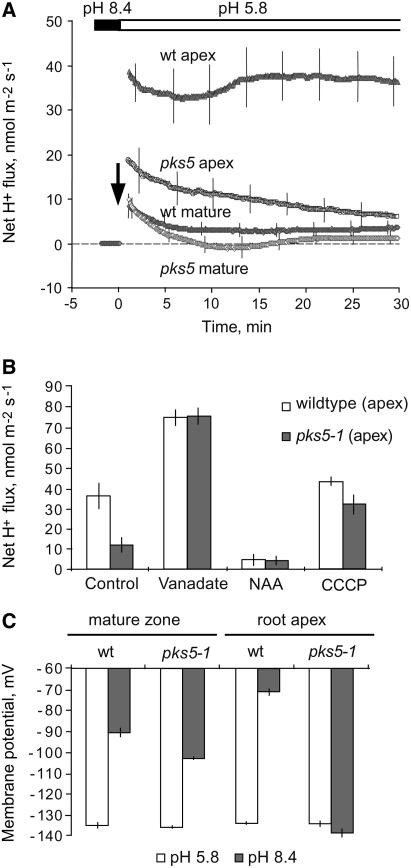

Noninvasive ion flux measurements (Shabala et al., 1997) were used for further in situ characterization of proton fluxes in pks5-1 roots. Due to the buffering effect of water, measuring net H+ fluxes at pHo > 8 was not feasible, as it would result in a gross (several orders of magnitude; Newman, 2001) underestimation of the flux value. To overcome this limitation, a series of recovery experiments (Shabala et al., 2006) was performed. Plant roots were treated at high pH (8.4) for 1 to 2 h. After roots adapted to alkaline conditions, solution pH was changed from 8.4 to 5.8, and transient net H+ fluxes were recorded as plants tried to adjust to acidic conditions.

Acidification of the root media resulted in a substantial increase in net H+ uptake as a consequence of an almost four order of magnitude increase in H+ concentration in the bath solution. Only a minor (P = 0.05) difference was found between wild-type and pks5-1 plants when net H+ fluxes were measured in the maturation zone (defined as the region 5 mm from the apex in 1-week-old seedlings; Figure 4A), whereas a fourfold difference (significant at P < 0.01) was found between wild-type and pks5 plants in the root apex, with much higher net H+ transport in wild-type roots. This is strong evidence that transmembrane H+ fluxes are increased in the pks5 mutant. We did not expect to observe higher H+-ATPase activity in the root apex compared with the maturation zone; this result might be explained by a dependence of the sensitivity of the technique employed for flux measurement that is dependent on the age of the cells investigated.

Figure 4.

In Vivo Measurement of Net Proton Fluxes from Roots of pks5 and Wild-Type Plants.

Noninvasive ion flux measurements (the MIFE) were used for in situ characterization of pks5 roots. Error bars represent means ± se of three replicate experiments.

(A) Net proton fluxes in pks5 and wild-type root tips and in mature roots. Due to the buffering effect of water at alkaline pH, a series of recovery experiments was performed. Plant roots were treated at high pH (8.4) for 1 to 2 h. After roots adapted to alkaline conditions, the solution pH was changed from 8.4 to 5.8 (indicated by an arrow), and transient net H+ fluxes were recorded as plants tried to adapt to acidic conditions.

(B) Net proton fluxes as a result of pretreatment with effectors of the PM H+-ATPase.

(C) Membrane potential in response to external pH in pks5 and wild-type root tips and in mature roots.

To confirm the involvement of a P-type pump in proton excretion in pks5-1 mutants, a pharmacological approach was undertaken (Figure 4B). Root pretreatment in 0.5 mM vanadate (a known inhibitor of P-type ATPases) eliminated any difference between net H+ fluxes in the wild type and pks5-1. Furthermore, vanadate caused a severalfold increase in the magnitude of H+ influx as expected from elimination of H+ extrusion. Root pretreatment with 100 μM 1-naphthaleneacetic acid (a known stimulator of the PM H+ pump; Hager, 2003) significantly reduced net H+ uptake in both genotypes (Figure 4B). Finally, the protonophore m-chlorophenylhydrazone (50 μM) also increased net H+ uptake in pks5-1 plants (Figure 4B). Taken together, these findings strongly suggest that the PM H+-ATPase activity is a major factor contributing to net H+ fluxes measured by the MIFE technique and that activity of the PM H+ pump is substantially higher in the pks5-1 root apex compared with that in wild-type plants.

Increased Membrane Potential in pks5 Mutant Plants

Activation of the PM H+-ATPase in root cells is expected to result in the development of a steep membrane potential, negative on the inside. Direct measurements of membrane potential of epidermal root cells were employed to test whether this was the case (Figure 4C). Alkaline treatment caused a substantial depolarization of the membrane in epidermal cells of the wild-type root apex. By contrast, alkaline pH did not evoke any reduction of membrane potential in such cells in pks5-1 plants (Figure 4C). This supports the notion that in pks5-1 plants, PM H+-ATPase activity is increased.

PKS5 Expression Is Regulated Developmentally and in Response to Hormones and Stress

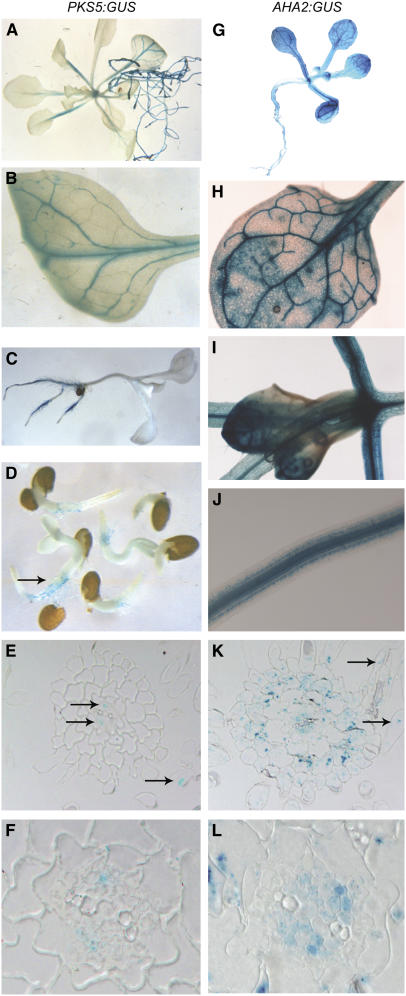

To examine the pattern of PKS5 gene expression, the PKS5 promoter was fused to the β-glucuronidase (GUS) reporter gene and GUS expression was determined in 10 independent transgenic lines. The GUS signal was not detected in flowers, siliques, or seeds from PKS5:GUS transgenic plants. However, upon germination, seedlings showed intense staining in hypocotyls and roots, including root hairs (Figures 5C and 5D), suggesting that PKS5 is regulated in a spatial manner. As seedlings matured, GUS activity was detected in the vascular tissue of both the stem and leaf (Figures 5A and 5B). While the intensity of staining was variable among the individual lines tested, the pattern observed was always similar.

Figure 5.

PKS5 and AHA2 Gene Expression Colocalizes in Arabidopsis.

GUS staining of transgenic plants expressing PKS5:GUS in roots ([A] to [E]) and vascular tissues of leaves and stems ([A] and [B]). GUS staining of transgenic plants expressing AHA2:GUS in roots ([G], [J], and [K]) and vascular tissues of leaves and stems ([H] to [J]). Cross sections of roots ([E], [F], [K], and [L]) with ×100 magnifications ([F] and [L]). Arrows indicate staining of vascular tissue (E) and root hairs ([E] and [K]).

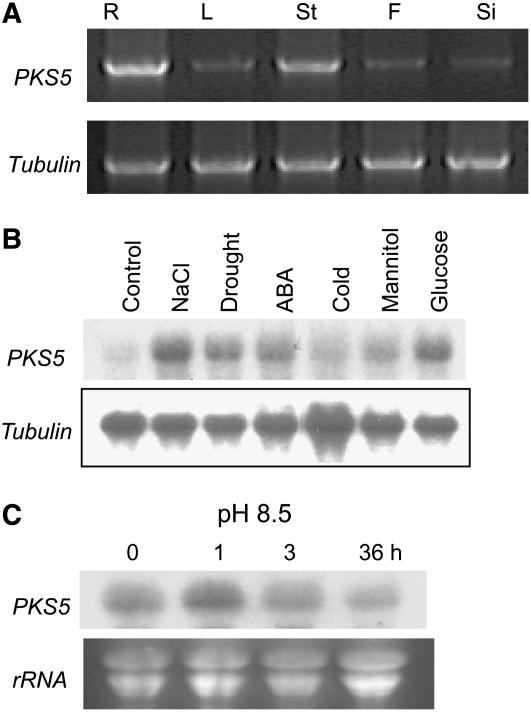

RT-PCR analyses confirmed that PKS5 is expressed in roots and stems but is barely detectable in flowers and siliques (Figure 6A). Expression of PKS5 in roots corresponds well with a role for this gene in regulating root medium acidification. To analyze the expression pattern of PKS5 in response to different environmental conditions, RNA gel blot analysis showed that the steady state level of PKS5 transcript was upregulated by treatment with NaCl, drought, ABA, and glucose but not by prolonged exposure to cold (Figure 6B). Extended exposure to high pH caused the PKS5 transcript level to decrease (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

PKS5 Expression in Arabidopsis Is Regulated by Developmental and Environmental Conditions.

(A) RT-PCR analysis of PKS5 in different plant tissues using tubulin as control. R, root; L, leaf; St, stem; F, flower; Si, silique.

(B) and (C) RNA gel blot analysis of PKS5 in response to NaCl (300 mM for 3 h), drought (water content reduced by 30%), ABA (100 μM for 3 h), cold (0°C for 48 h), osmotic stress (300 mM mannitol for 3 h), glucose (300 mM for 3 h), or high external pH (C). Hybridization to a tubulin probe (B) or ethidium bromide staining of rRNA (C) was used as loading control.

To compare the expression pattern of PKS5 with that of AHA2, a major PM H+-ATPase isoform in roots (Harper et al., 1990), we cloned the AHA2 promoter and fused it to the GUS reporter gene. Among 11 independent lines of transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing this construct, all showed high expression in roots and leaves, especially in the vascular tissue (Figures 5G to 5J). In cross sections of the root, blue precipitate was readily identified in epidermal cells, including root hairs, as well as in cortex, phloem, and xylem parenchyma cells (Figures 5K and 5L). In similar cross sections of pPKS5:GUS-expressing plants, staining was evident in root phloem (Figures 5E and 5F), known to have a relatively high amount of cytoplasm compared with other cell types, but could not be identified with certainty in other cell types, most likely due to significantly lower expression levels (note the GUS staining of root hairs in pPKS5:GUS-expressing plants in Figures 5C and 5D). Taken together, PKS5 and the PM H+-ATPase isoform AHA2 colocalize in most Arabidopsis tissues, including roots.

High External pH Elicits a Cytosolic Ca2+ Signal

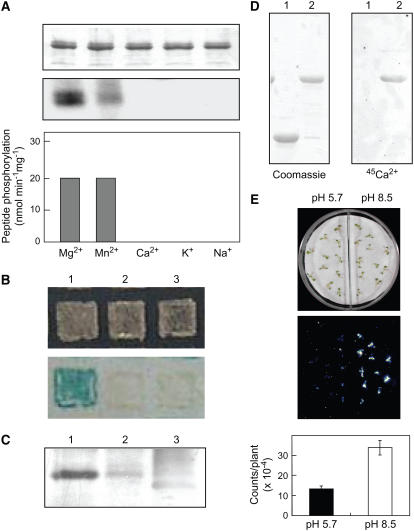

To determine if perception of high external pH involves a cytosolic Ca2+ signal, transgenic Arabidopsis seedlings containing a 35S:aequorin chimeric gene (Knight et al., 1991) were germinated and grown on Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium at pH 5.7. Four-day-old seedlings were transferred to MS media at pH 5.7 or 8.5. Immediately after the transfer, the seedlings were imaged for bioluminescence. Figure 7E shows that luminescence intensity in response to treatment at pH 8.5 is ∼2 times higher than that at pH 5.7, suggesting that exposure to high external pH triggers a fast increase in the concentration of cytoplasmic free Ca2+ in Arabidopsis.

Figure 7.

PKS5 Is an Active Protein Kinase and Interacts with SCaBP1, and High External pH Triggers a Ca2+ Signal.

(A) Evaluation of PKS5 autophosphorylation and phosphorylation of a peptide substrate. Following autophosphorylation assays, protein (100 ng per lane) was separated by SDS-PAGE, and the gel was stained with Coomassie blue (top panel) and exposed to x-ray film (middle panel). The ability of PKS5 to phosphorylate the peptide substrate p3 (400 pmol per assay) in the presence of different cofactors was determined (bottom panel). Data represents means ± sd; n = 3.

(B) Interaction between SCaBP1 and PKS5 in a yeast two-hybrid assay. A yeast strain, Y190, transformed with the following constructs: pAS2-SCaBP1 and pACT2-PKS5 (lane 1); pAS2-SCaBP1 and pACT (lane 2); pACT-PKS5 and pAS2 (lane 3). Top panel, yeast growth; bottom panel, β-galactosidase activity.

(C) SCaBP1 and PKS5 interact in vivo. Coimmunoprecipitation of Myc-tagged PKS5 and HA-tagged SCaBP1 protein from protoplasts. PKS5-Myc was immunoprecipitated using anti-Myc antibodies and the coprecipitated SCaBP1 protein detected by protein gel blotting using HA antibodies. Lane 1, protoplasts transformed with PKS5-Myc and SCaBP1-HA plasmid DNA; lane 2, as in lane 1, but protein extracted from half as many protoplasts; lane 3, protoplasts transformed only with PKS5-Myc.

(D) SCaBP1 is a Ca2+ binding protein. GST-SCaBP1 fusion protein and GST were separated on 12.5% SDS-PAGE gels and blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and the membrane was incubated with 45Ca2+. Left panel, Coomassie blue staining; right panel, Ca2+ binding. Lane 1, GST; lane 2, GST-SCaBP1.

(E) High external pH elicits a cytosolic Ca2+ signal. Transgenic seedlings containing 35S:aequorin were grown on MS medium for 4 d. The seedlings were treated with 10 μM coelenterazine overnight. Seedlings were transferred to dishes that were divided into two parts: one with filter paper saturated with nutrient solution at pH 8.5 and another with pH 5.8. Bioluminescence images (middle panel) were taken immediately after transfer to media and quantified (bottom panel). Error bars represent means ± se of three replicate experiments.

SCaBP1 Is a Ca2+ Binding Protein and Interacts with PKS5

PKS5 is a predicted protein kinase with high sequence similarity to SOS2 (Guo et al., 2001). Previous studies have shown that SOS2 interacts with and is activated by the Ca2+ binding protein SOS3 (Halfter et al., 2000). Using yeast two-hybrid assays, we tested whether PKS5 interacts with members of the SCaBP/CBL family. PKS5 was found to interact with the SOS3-like Ca2+ binding protein SCaBP1/CBL2 (Figure 7B) but not with any other member of the SCaBP/CBL family. Rapid appearance of intense β-galactosidase reporter gene activity demonstrated that PKS5 interacted specifically and strongly with SCaBP1.

To determine if PKS5 interacts with SCaBP1 in vivo, a Myc-tag was fused translationally to the C-terminal end of PKS5 and an HA-tag was fused to the C-terminal end of SCaBP1. PKS5-Myc and SCaBP1-HA were transfected into Arabidopsis protoplasts (Sheen, 2001). PKS5-Myc was immunoprecipitated using anti-Myc antibodies, and the proteins were subjected to immunoblot analysis using HA antibodies (Figure 7C). The results show that SCaBP1 coimmunoprecipitated with PKS5 (lane 1), suggesting that PKS5 interacts with SCaBP1 in planta. Antibody recognition was diminished when the number of protoplasts used in the assay was reduced to by half (lane 2) and eliminated when the PKS5-Myc plasmid alone was transferred into the protoplasts (lane 3).

The deduced amino acid sequence of SCaBP1 suggests the presence of at least three putative EF-hand motifs (Guo et al., 2001). To determine if SCaBP1 is capable of binding Ca2+, glutathione S-transferase (GST)-SCaBP1 fusion protein and GST were used in Ca2+ binding assays. Proteins were separated on 12.5% SDS-PAGE gels and blotted to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was then incubated with 45Ca2+ (Figure 7D, right panel). GST-SCaBP1 (lane 2) but not GST (lane 1) was able to bind Ca2+, demonstrating that SCaBP1 is a Ca2+ binding protein.

PKS5 Encodes an Active Protein Kinase

To determine if PKS5 is a functional protein kinase, GST-PKS5 fusion protein was produced in Escherichia coli and used in vitro for autophosphorylation and phosphorylation of the peptide substrate p3 (Halfter et al., 2000). While Ca2+, K+, and Na+ had no effect on either activity, Mg2+ or Mn2+ could serve as a cofactor for both (Figure 7A). Highest levels of autophosphorylation were found when Mg2+ was included in the assay (Figure 7A, middle panel); however, there was no significant difference in p3 peptide phosphorylation in the presence of Mg2+ or Mn2+ (Figure 7A, bottom panel). These results demonstrate that the recombinant PKS5 protein is an active protein kinase. This is in contrast with bacterially expressed SOS2 protein and several other PKS proteins that are all incapable of substrate phosphorylation in vitro (Halfter et al., 2000; Gong et al., 2002).

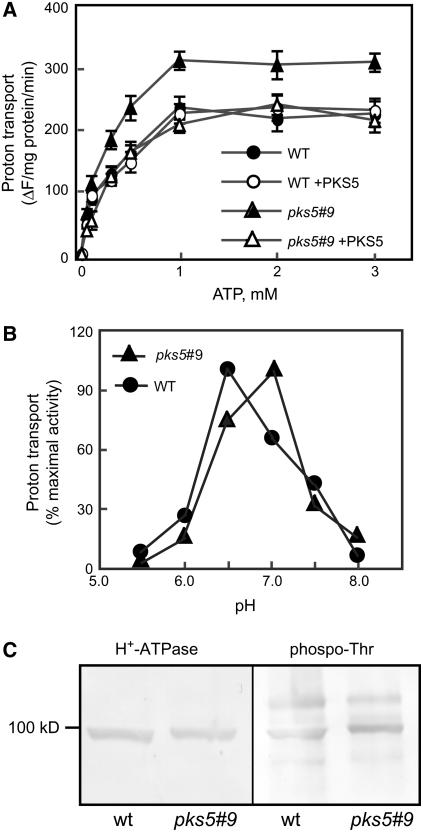

PKS5 Negatively Regulates the Activity of the PM H+-ATPase

To determine whether PKS5 phosphorylation of the PM H+-ATPase affects the activity of this pump, the H+ transport activity of the ATPase was compared in plasma membrane vesicles isolated from wild-type and pks5#9 plants. ΔpH formation was significantly higher in vesicles isolated from pks5#9 plants (Figure 8A). We performed protein blot analysis and found similar levels of PM H+-ATPase protein in pks5 mutants compared with wild-type plants (Figure 8C), which confirms that activation of the proton pump was at the posttranslational level. Immunodecoration of PM H+-ATPase protein with an antiphosphothreonine antibody resulted in similar staining in wild-type and pks5 plants (Figure 8C), implying that dephosphorylation of Thr-947 could not have been part of this negative regulation.

Figure 8.

PKS5 Negatively Regulates the Activity of the PM H+-ATPase.

(A) H+ transport (ΔpH formation) as a function of substrate (ATP). Data represent means ± se of at least three replicate experiments. Each replicate experiment was performed using independent membrane preparations from wild-type and pks5#9 plants grown at the same time.

(B) Measurement of ΔpH formation as a function of pH at 3 mM ATP. One representative experiment of three replicates is shown; each replicate experiment was performed using independent membrane preparations. Reactions in (A) and (C) were initiated with the addition of 4 mM MgSO4. In (B), data are presented as percentage of control initial rate, which was set at 100% for activity at pH 6.5 and 7.0 for the wild type and pks5#9, respectively.

(C) Protein blot of PM proteins from wild-type and pks5#9 plants probed with an anti-PM H+-ATPase antibody (left) or an antiphosphothreonine antibody (right).

To test the in vitro effect of PKS5 on H+ pumping, a GST-PKS5 fusion protein was added directly to H+ transport assays. In the presence of 100 ng/mL GST-PKS5, H+-transport activity in the pks5#9 plants was reduced to the level measured in vesicles isolated from wild-type plants (Figure 8A, pks5#9 +PKS5). No effect on the H+ transport was observed when GST-PKS5 was added to vesicles isolated from wild-type plants (Figure 8A). The specificity of PKS5-induced reduction in activity of the ATPase was demonstrated when T/DSOS2DF, a constitutively active SOS2 kinase (Qiu et al., 2002), did not reduce H+ transport activities.

Kinetic analysis showed that the PM H+-ATPase in pks5#9 and wild-type plants had a similar affinity for ATP (Km ∼0.15 mM). Other differences in the properties of the H+-ATPase in wild-type and pks5#9 plants included a modest increase in the Vmax (Figure 8A) and a shift in the pH optimum from 6.5 to 7.0 (Figure 8B). A shift of the pH optimum toward the alkaline range is typical for activated forms of the PM H+-ATPase (Palmgren, 2001).

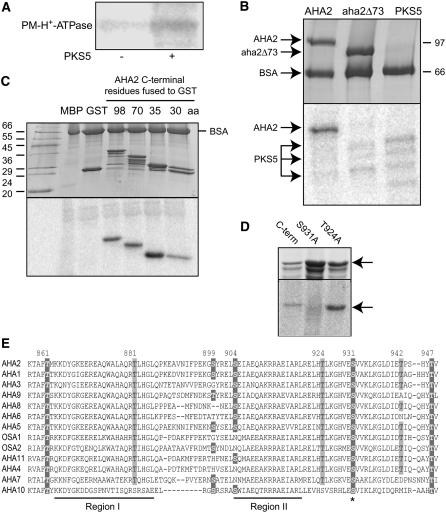

PKS5 Phosphorylates Ser-931 of the PM H+-ATPase AHA2

To determine if the reduction in PM H+-ATPase activity in the presence of PKS5 could be a result of direct phosphorylation of the transporter, in vitro phosphorylation assays were performed. The ATPase was precipitated from detergent solubilized plasma membrane vesicles with a combination of antibodies prepared to the central loop, the N terminus, and the C terminus of the PM H+-ATPase. When the immunoprecipitated protein was used in phosphorylation assays with PKS5, an ∼100-kD protein corresponding to the PM H+-ATPase was phosphorylated (Figure 9A). By contrast, an active SOS2 kinase, T/DSOS2DF, was not able to phosphorylate the ATPase.

Figure 9.

PKS5 Phosphorylates the PM H+-ATPase.

(A) The H+-ATPase was pulled down from plasma membrane vesicles with polyclonal H+-ATPase antibodies and used in phosphorylation assays without (left lane) and with (right lane) PKS5 protein.

(B) Deletion of 73 C-terminal amino acid residues eliminates PKS5 phosphorylation of the H+-ATPase AHA2. Coomassie blue–stained SDS gel (10%; top panel) and the corresponding phosphor image (bottom panel). Lane 1, AHA2 + PKS5; lane 2, aha2Δ73 + PKS5; lane 3, PKS5 alone (3× concentration as in lanes 1 and 2), PKS5 appears as a triple band.

(C) PKS5 phosphorylates the C terminus of AHA2. Coomassie blue–stained gradient SDS gel (8 to 15%; top panel) and the corresponding phosphor image (bottom panel). Lane 1, molecular mass standards; lane 2, myelin basic protein (MBP); lane 3, GST; lane 4, GST C-terminal 98 amino acids (aa); lane 5, GST C-terminal 70 amino acids; lane 6, GST C-terminal 35 amino acids; and lane 7, GST-C-terminal 30 amino acids.

(D) Phosphorylation of GST C-terminal AHA2 mutants. Coomassie blue–stained SDS gel (top panel) and the corresponding phosphor image (bottom panel). Lane 1, wild type; lane 2, T931A; and lane 3, S942A.

(E) Alignment of the C termini of the PM H+-ATPases in Arabidopsis (AHA2 numbering). Ser or Thr residues reported to be phosphorylated are boxed with dark gray; conserved Ser and Thr residues are boxed with light gray. Ser-931, the site of AHA2 phosphorylation by PKS5, is conserved in the PM H+-ATPases in Arabidopsis (marked with an asterisk).

Because AHA2 is a major isoform of the PM H+-ATPase expressed in Arabidopsis roots, we reasoned that it might be a substrate for PKS5. To test this, full-length AHA2 was expressed in yeast and purified by nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose chromatography (Figure 9B), and the purified protein was used as substrate for in vitro phosphorylation assays with PKS5. Results from these phosphorylation assays demonstrated that PKS5 phosphorylates full-length AHA2 and that PKS5 undergoes autophosphorylation. A purified AHA2 deletion mutant, aha2Δ73, lacking the C-terminal 73 amino acid residues of the regulatory domain, was not phosphorylated by PKS5 (Figure 9B). These results strongly indicate that the target site for PKS5 phosphorylation is located within the C-terminal 73 residues of AHA2.

To narrow down the PKS5 phosphorylation site in AHA2, different parts of the regulatory C-terminal region of AHA2 were expressed in E. coli as GST fusion proteins (Figure 9C) and used in phosphorylation assays. PKS5 does not phosphorylate GST but phosphorylates the fusions between GST and the 98, 70, 35, or 30 C-terminal amino acid residues of AHA2 (Figure 9C). The PKS5 phosphorylation site must, therefore, be located within the last 30 amino acids of the regulatory C-terminal region of the H+-ATPase. GST-AHA2 fusion proteins were found to be rapidly degraded following their isolation, and multiple bands were therefore observed on Coomassie blue–stained gels. However, it is evident that only full-length protein is phosphorylated by PKS5 (Figure 9C).

To identify the specific site for PKS5 phosphorylation in AHA2, all Ser and Thr residues within the last 35 C-terminal residues of the ATPase were replaced one by one with an Ala residue. The mutant proteins were subsequently tested for their ability to serve as substrates for PKS5 phosphorylation. Despite high levels of expression, the S931A mutant protein was not phosphorylated by PKS5. By contrast, wild-type protein as well as the T924A, T942A, S904A, and T947A mutant proteins served as substrates for PKS5 (Figure 9D). It therefore seems likely that Ser-931 serves as the target for PKS5 action. A mass spectrometric approach (Nühse et al., 2004) was taken to investigate whether Ser-931 is phosphorylated in Arabidopsis in vivo. Although AHA2-derived peptides showed high coverage of the hydrophilic parts of the pump molecule (Nühse et al., 2004), we did not observe any peptide, phosphorylated or not, that included Ser-931. The vicinity of Ser-931 is highly charged and contains many recognition sites for proteases. The expected small size of peptides including Ser-931 may therefore complicate peptide recovery after proteolytic digest of samples. Among Arabidopsis PM H+-ATPases, the region surrounding Ser-931 is highly conserved (Figure 9E). This indicates that other PM H+-ATPases may also be substrates of PKS5.

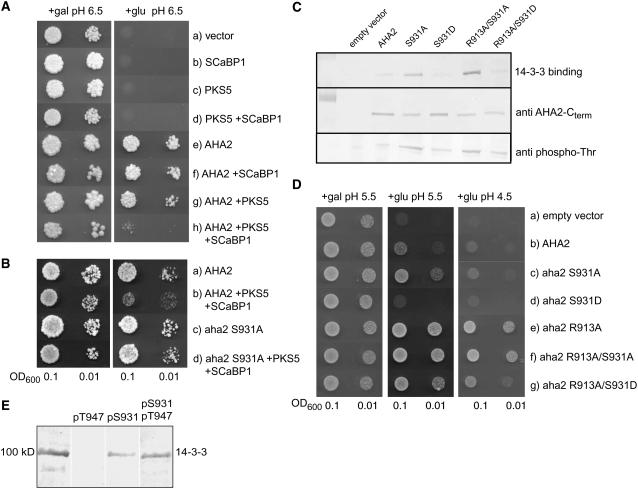

PKS5-Mediated Phosphorylation of AHA2 Inhibits Interaction with an Activating 14-3-3 Protein

When expressed in yeast, Thr-947 of AHA2 is phosphorylated by an endogenous yeast protein kinase, allowing for an interaction of the C-terminal domain with the host 14-3-3 protein (Fuglsang et al., 1999). Figure 10C demonstrates that the interaction of a 14-3-3 protein with the C-terminal domain of the H+-ATPase was abolished when Ser-931 is mutated to Asp to mimic the negative charge introduced by phosphorylation. A S931A mutation showed increased 14-3-3 binding (Figure 10C). An activated mutant of the H+-ATPase R913A is highly phosphorylated at Thr-947 and strongly binds 14-3-3 protein (Jahn et al., 2002). A double mutant R913A/S931D showed strongly reduced binding of 14-3-3 protein (Figure 10C). The inability of the S931D mutant to bind 14-3-3 protein could reflect a lack of phosphorylation of Thr-947, the only Thr residue that has been demonstrated to be phosphorylated in AHA2. This possibility could be ruled out as in protein blots, the S931D mutant was clearly immunodecorated with a phosphothreonine antibody and to comparable levels as wild-type AHA2 (Figure 10C).

Figure 10.

Together, PKS5 and SCaBP1 Inhibit the Activity of the PM H+-ATPase AHA2 When Expressed in Yeast by Reducing the Amount of 14-3-3 Protein Bound.

(A) Drop tests were used as an indication of the activity of AHA2. The endogenous yeast PM H+-ATPase is only expressed when galactose is used as a carbon source, so the growth of the cells is dependent on the activity of AHA2 on glucose medium. The yeast cells harbor three plasmids expressing AHA2, PKS5, and SCaBP1 in different combinations (a to h). Cells were diluted in sterile water, and 8 μL was spotted at two concentrations (OD600 = 0.1 and 0.01) on selective media, pH 6.5. Gal, galactose; glu, glucose. The growth of the cells was monitored 3 to 6 d after transformation.

(B) Mutation of Ser-931 in AHA2 abolishes the inhibition by PKS5 and SCaBP1. Drop test of yeast cells expressing AHA2 alone (a), AHA2 together with PKS5 and SCaBP1 (b), aha2S931A alone (c), or together with PKS5 and SCaBP1 (d).

(C) Binding of 14-3-3 protein to the PM H+-ATPase is reduced when a charge is introduced at position 931 in aha2. Plasma membrane from yeast expressing different mutants of aha2 was subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Top panel, 14-3-3 binding in an overlay assay; bottom panel, protein gel blot detecting the AHA2 C terminus.

(D) Drop test demonstrating the yeast growth related to the amount of 14-3-3 protein bound to the PM H+-ATPase. As in (A), except that medium pH was 4.5 and yeast cells only harbored a single plasmid containing the H+-ATPase.

(E) Overlay assay in which interaction between 14-3-3 proteins and PM H+-ATPase immobilized on a membrane cannot be abolished by a peptide derived from the C terminus of AHA2 if it is phosphorylated at Ser-931. 14-3-3 proteins were preincubated with peptides before use in the overlay assay. The peptides employed were all derived from the 24 C-terminal residues of AHA2 (residues 925 to 948) and contained one or two phosphoryl groups at the indicated positions. Unless indicated, unphosphorylated peptide was used.

To study the in vivo consequences of the changed ability of AHA2 to bind 14-3-3 proteins, growth of the yeast pma1 mutant expressing the above constructs was studied. At acidic external pH (pH 4.5) AHA2 cannot complement pma1 (Figure 10D, b), but at somewhat higher pH values (pH 5.5), AHA2 supports some growth in the absence of Pma1p (Figure 10D, b). Substituting Ser-931 with Asp resulted in reduced growth at pH 5.5 compared with wild-type AHA2 (Figure 10D, d). The constitutively activated R913A mutant supports increased growth (Figure 10D, e), but substitution of Ser-931 with Asp in this background likewise resulted in reduced growth (Figure 10D, g). Taken together, these results support the hypothesis that phosphorylation of Ser-931 interferes with binding of a 14-3-3 protein even under conditions where Thr-947 is phosphorylated.

To test this hypothesis more directly, peptides covering the 24 C-terminal residues of AHA2 were synthesized so that they were nonphosphorylated or phosphorylated at either Thr-947, Ser-931, or both of these positions. Recombinant AHA2 protein was immobilized on a membrane and incubated with 14-3-3 protein in the presence of the fungal toxin fusicoccin that induces an almost irreversible binding of 14-3-3 protein to the C-terminal portion of the PM H+-ATPase. Figure 10E shows that the peptide carrying a phosphoryl group on Thr-947 prevented 14-3-3 binding to AHA2, indicating that the peptide phosphorylated at this position interacts with 14-3-3 protein as expected. Conversely, the peptide carrying a phosphogroup at Ser-931 did not interact with 14-3-3 protein. Strikingly, the peptide carrying phosphoryl groups at both Ser-931 and Thr-947 did not interact with 14-3-3 protein. This demonstrates that phosphorylation of AHA2 at Ser-931 prevents interaction with 14-3-3 protein no matter whether Thr-947 is phosphorylated or not.

Reconstitution of AHA2 Regulation by SCaBP1 and PKS5 in Yeast

To test the effect of PKS5 on the activity of AHA2, we used the yeast strain RS-72 as a model organism. In RS-72, the endogenous H+-ATPase, PMA1, is under the control of the GAL1 promoter and is therefore only expressed when grown on media with galactose as the sole carbon source. When grown on media containing glucose, the yeast cells are dependent on the activity of the plasmid-borne plant PM H+-ATPase under the control of the constitutive PMA1 promoter. As shown in Figure 10, SCaBP1, PKS5, or an empty vector did not support growth of PMA1-deficient yeast cells on selective media (Figure 10A, a to d). When AHA2 was expressed alone, the activity of the plant PM H+-ATPase complemented the function of the endogenous PM H+-pump and the cells grew (Figure 10A, e).

We next tested whether phosphorylation of the PM H+-ATPase by PKS5 is regulated by SCaBP1 in vivo. When PKS5 and SCaBP1 were coexpressed with AHA2, the cells grew very poorly, suggesting that PKS5 and SCaBP1 downregulate the activity of AHA2 (Figure 10A, h). PKS5 and SCaBP1 did not have any effect when only one of them was expressed with AHA2 (Figure 10A, f and g). This demonstrates that in the yeast system, PKS5 and SCaBP1 can act in concert to inactivate AHA2.

The in vitro phosphorylation experiments suggested that PKS5 phosphorylates Ser-931 in AHA2. We therefore mutated the Ser residue to an Ala and transformed the mutant aha2S931A into RS-72, either alone or together with PKS5 and SCaBP1. As can be seen in Figure 10B, the S931A mutation did not affect the yeast complementation of pma1 by AHA2 (a and c), but it completely abolished the repressive effect of SCaBP1 and PKS5 on AHA2 activity (Figure 10B, b and d). This result further supports the conclusion that Ser-931 in AHA2 is the target of PKS5.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we used a reverse genetics approach to investigate the function of the Arabidopsis protein kinase PKS5, which colocalizes in the plant body with the major PM H+-ATPase isoform AHA2. Our results indicate that PKS5 is a critical negative regulator of the PM H+-ATPase that controls extracellular acidification and that PKS5 itself is a component of a Ca2+-dependent signaling pathway elicited by an alkaline environment.

To corroborate the physiological role of these regulatory components, yeast was used as a heterologous host for the reconstitution of a complete plant signal transduction chain, including the PM H+-ATPase, the final target, PKS5, and SCaBP1, a Ca2+ sensor interacting with PKS5. SCaBP1 and PKS5 in concert exert a constitutive repressive effect on the PM H+-ATPase. We demonstrated that this inhibition is due to an inability of PKS5-phosphorylated H+-ATPase to interact with an activating 14-3-3 protein. The role of SCaBP1 in PKS5 regulation is still not clear. It could act as a direct modulator of protein kinase activity, but in vitro, we found PKS5 to be active in the absence of SCaBP1, although activity of PKS5 in vivo in yeast complementation assays was dependent upon the presence of SCaBP1. Alternatively, SCaBP1 could be involved in recruiting PKS5 to the plasma membrane, in analogy with the role of SOS3 in controlling SOS2 targeting (Quintero et al., 2002).

Because of the essential role of PM H+-ATPases in plant growth, development, and responses to hormones and the environment, our finding that the activity of these proton pumps is inhibited by PKS5 has far-reaching implications. In pks5 mutant plants, PM H+-ATPase activity is derepressed. The increased H+ transport activity lowers the pH in the local rhizosphere. This is likely to be an advantage not only in an alkaline environment but also under other conditions where a steeper ΔpH across the plasma membrane is required. By contrast, negative regulation of the PM H+-ATPase by PKS5 might be an advantage under conditions where PM H+-ATPase activity has to be rapidly downregulated (e.g., when external signals induce membrane depolarization and cytoplasmic acidification) (Mathieu et al., 1996). In response to fungal elicitors, the PM H+-ATPase was shown to be inhibited by phosphorylation via a CDPK (Lino et al., 1998) and activated by dephosphorylation (Xing et al., 1996), although the protein kinase and phosphatase were not identified. One site of inhibition most likely involves dephosphorylation of Thr-947, whereas phosphorylation of Ser-931 might provide an additional inhibition site.

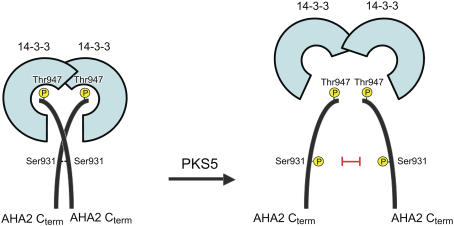

The results presented in this article suggest a model in which 14-3-3 regulation of the PM H+-ATPase is controlled by at least two protein kinases. The first protein kinase, which is still not identified, phosphorylates Thr-947, creating a binding site for an activating 14-3-3 protein (Fuglsang et al., 1999, 2003). The protein kinase identified in this work, PKS5, has Ser-931 as its target and abolishes 14-3-3 binding even if Thr-947 is phosphorylated (Figure 11). Thus, it appears that plant PM H+-ATPases can be either activated or inhibited by phosphorylation, depending on the protein kinase involved. The C-terminal end of the H+-ATPase, including the phosphorylated Thr-947, interacts with a specific binding groove of the 14-3-3 protein (Würtele et al., 2003). In addition to this site, an upstream region of the H+-ATPase covering residues Glu-915 to Val-932 interacts with 14-3-3 proteins (Jelich-Ottmann et al., 2001; Fuglsang et al., 2003). This interaction, which involves another region of the 14-3-3 protein, is required for stabilization of the protein–protein interaction.

Figure 11.

Model for the Regulation of the PM H+-ATPase by Two Protein Kinases.

When the PM H+-ATPase is phosphorylated at the very C terminus on Thr-947, the binding of a dimeric 14-3-3 protein results in activation of the pump. Each 14-3-3 protein binds the C-terminal tail of a PM H+-ATPase molecule, resulting in a complex between two 14-3-3 proteins and two closely associated C-terminal regions of the PM H+-ATPase (Ottmann et al., 2007). Following activation, the proton pump can be inactivated by either a protein phosphatase removing the phosphate group on Thr-947 (data not shown) or by the PKS5 protein kinase, which introduces a second phosphate group upstream in the C terminus at Ser-931. Due to steric and electrostatic hindrances, the complex between two 14-3-3 proteins and two PM H+-ATPases is not stable when Ser-931 is simultaneously phosphorylated on both PM H+-ATPase polypeptides. As a consequence, the binding of 14-3-3 protein to the PM H+-ATPase is blocked.

While this work was under revision, the structure of a peptide covering the 52 C-terminal residues of PMA2, a tobacco PM H+-ATPase, in complex with 14-3-3 proteins was published (Ottmann et al., 2007). Each binding groove of a dimeric 14-3-3 protein binds the C-terminal end of a PMA2 peptide. Outside the binding cleft, the two peptides interact with each other. According to the crystal structure, Ser-938 (corresponding to Ser-931 in AHA2) exposes its side chain to the center of the dimeric 14-3-3 protein. At this position, the peptides are in close proximity to each other, and the side chains of two Ser-938 are facing one another. Substitution of Ser-938 with a negative charge abolished binding of 14-3-3 protein (Ottmann et al., 2007). It therefore seems plausible that phosphorylation of Ser-931 in AHA2 results in steric and electrostatic hindrances that lead to destabilization of the complex between the 14-3-3 protein and the H+-ATPase even though Thr-947 is phosphorylated.

In support of the inhibitory role of phosphorylation at Ser-931, Kinoshita and Shimazaki (2002) found that a synthetic phosphopeptide derived from the C-terminal region of the Vicia faba PM H+-ATPase VHA1 and phosphorylated at Ser-933 (corresponding to Ser-931 of AHA2) does not bind to 14-3-3 protein but inhibits a blue light–activated VHA1. This would suggest that the phosphopeptide can contribute to autoinhibition of the pump and might represent part of the C terminus directly involved in negative regulation. In response to treatment with elicitors, two other phosphorylation sites have been identified in the PM H+-ATPase (Nühse et al., 2003); however, the residue identified in this work, Ser-931, is not one of these two sites. This does not exclude a phosphorylation of Ser-931 in vivo, since none of the AHA2-derived peptides identified covered this region of AHA2 (Nühse et al., 2004).

Our data show that PKS5 is regulated by high external pH at multiple levels. First, its activity is regulated by Ca2+ signaling, likely through SCaBP1. Second, PKS5 expression is downregulated by treatment with high pH. This downregulation of PKS5 transcript level is consistent with our proposed reduction of its kinase activity and probably contributes to the overall inactivation of this kinase. Although PKS5 and SCaBP1 in concert inhibit AHA2 when coexpressed in yeast and Ca2+ increases in Arabidopsis seedlings in response to an alkaline environment, we still do not know whether alkaline pH induces increased cytoplasmic Ca2+ specifically in root epidermal cells and whether this results in activation or deactivation of PKS5 in planta. This might be dependent on other proteins, cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentrations, and/or fluctuation patterns. Although the level of PKS5 transcript is upregulated by treatment with ABA, NaCl, mannitol, glucose, or drought, pks5 mutant plants did not show any phenotypic defect under these conditions, suggesting that plant responses to these conditions may involve proteins that are functionally redundant with PKS5.

In summary, we have identified components of a signal transduction pathway that regulates the major ion pump in the plant plasma membrane. This provides a novel example of the posttranslational network of players that control solute transport across the plant plasma membrane.

METHODS

Plant Materials

Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Columbia (Col) was used in all experiments. Plants for genetic analysis, transformation, and vesicle transport assays were grown in pot medium (Metro-Mix 350; Scott-Sierra Horticultural Products) in growth chambers with 16 h light at 22°C, 8 h dark at 18°C, and 70% relative humidity. All seedlings were germinated and grown on MS media at pH 5.8 unless otherwise indicated. Four-day-old seedlings grown under constant white fluorescent light at room temperature (22°C ± 2°C) were used for external pH tests or luminescence imaging.

For MIFE experiments, plants were grown at 22°C and 24 h fluorescent lighting (100 mmol m−2 s−1 irradiance) in sterile conditions in full-strength MS media supplemented with 1% (w/v) sucrose (see Demidchik et al., 2002 for more details). For measurements, 5- to 6-d-old plants were used.

Ion Flux Measurements

Net fluxes of H+ were measured noninvasively using the MIFE technique (University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia) essentially as described (Shabala et al., 1997; Shabala, 2000). Microelectrodes were pulled and silanized with tributylchlorosilane. After backfilling, electrode tips were filled with a commercially available ionophore H+ cocktail (95297 from Fluka). The electrode was mounted on a three-dimensional micromanipulator (MMT-5; Narishige) positioned 20 μm above the root surface.

Single Arabidopsis plants were mounted horizontally in a Perspex holder with agar (see Babourina et al., 2000 for details). The holder was immediately placed in a 4-mL measuring chamber filled with bath medium at pH 5.8 (control plants) or pH 8.4 (treated plants). The chamber was mounted on a computer-driven three-dimensional manipulator (Patchman NP2; Eppendorf) and left to equilibrate for 2 h.

Net ion fluxes were measured from the root epidermis in mature (∼2 to 3 mm from the root tip) and meristematic (∼120 μm from the tip) zones. During measurements, the MIFE software controlled the PatchManNP2 (Eppendorf) to move the electrodes between two positions, 20 and 50 μm from the root surface in a 10-s square-wave manner. The software also recorded electric potential differences from the electrodes between the two positions using a DAS08 analog-to-digital card (Computer Boards) in the computer (for details, see Shabala et al., 1997; Newman, 2001). Using the calibrated Nernst slope of pH, the ion flux was calculated using the MIFE software for cylindrical diffusion geometry (Newman, 2001).

The basic bathing solution was 0.5 mM KCl plus 0.1 mM CaCl2, adjusted to pH 5.8 or 8.4 with KOH, and was unbuffered. For the control plants, the solution was changed just prior to measurement. For the H+ flux measurements in the treated plants bathed for 2 h at pH 8.4, the solution was replaced with that at pH 5.8 within 2 min of the start of the flux measurement. Recordings for H+ flux were made for 20 min for the control plants and for 60 min for the treated plants.

Membrane Potential Measurements

Conventional KCl-filled Ag/AgCl microelectrodes (Shabala and Lew, 2002) with tip diameter ∼0.5 μm were used to measure membrane potential of epidermal cells in mature (∼2 to 3 mm from the root tip) and meristematic (∼120 μm from the tip) zones. Arabidopsis plants were mounted in the holder as described above and left to equilibrate in the basic bathing medium at pH 5.8 or 8.4 for 2 h. Steady state membrane potential values were measured with the plants in these solutions from at least five individual plants for each treatment and both the mature zone and the apex for each root, with not more than three measurements taken from any one root. Membrane potentials were recorded for 1.0 min after the potential stabilized following cell penetration.

Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy

Seedlings (7 to 15 d old) were incubated for 20 min under dark and humid conditions in probe D1950 (20 μM; Molecular Probes) containing dextran, fluorescein (pH sensitive, excitation 488 nm, emission 565 to 590 nm), and tetramethylrhodamine (pH insensitive, excitation 543 nm, emission 565 to 590 nm). After incubation, seedlings were thoroughly washed in KCl buffer, pH 6.0 (10 mM), and mounted in medical adhesive (Hollister) on microscope slides and covered with a droplet of KCl buffer, pH 6.0 (10 mM).

The slides were placed in a confocal microscope (Leica TCS SP2; Leica Microsystems), and ×40 dipping lenses with a numerical aperture of 0.8 were used for all recordings. Recordings were in xyt mode with a line average of 4 and 15 s between each recording. Total recording time was 10 min. Recordings were started at pH 6, and after five scans (60 s), the buffer was changed to KHCO3 buffer, pH 8.6 (10 mM). After an additional 30 scans (510 s), the buffer was changed to MES, pH 4.0 (0.1 M). All recordings were conducted on cells in the zone of the radicle immediately under the hypocotyl where root hair density is highest.

A pH ratio calibration curve was calculated using pH buffers in the range of pH 4.0 to 8.7 (Figure 3E) to ensure that measurements were made in the sensitive area of the probe.

Ratio curves were calculated for each Col-0 and pks5 seedling, and the reaction slope between scans 5 and 35 were calculated and tested using one-way analysis of variance. The mutant plants lowered pH significantly more than wild-type plants (P = 0.017) over a period of 7.5 min.

RNA Gel Blot and RT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from wild-type Arabidopsis roots, leaves, stems, siliques, and seeds or from wild-type plants treated with low temperature, ABA, NaCl, glucose, mannitol, or drought (see text for details) and used for RNA gel blot analysis (30 μg per lane). For RT-PCR analysis of PKS5 expression, first-strand cDNA was synthesized from total RNA isolated from wild-type and PKS5 RNAi plants using the following primers: reverse, 5′-ATGCCAGAGATCGAGATTG-3′; forward, 5′-TGAACCCTGAGTTTACCATTC-3′.

PKS5:GUS Constructs and Histochemical Detection of GUS Activity

To prepare the PKS5:GUS construct, a 1543-bp PKS5 promoter fragment, referring to the translation start codon, was isolated by PCR and cloned into the pBI101 vector between the HindIII and XbaI sites. The AHA2:GUS construct contained a 2000-bp AHA2 promoter fragment, isolated by PCR and cloned into pCAMBIA 1303. After transformation, 10 independent transgenic lines (T2) were tested for GUS activity (Haritatos et al., 2000).

PKS5 Kinase Activity

Prior to use, the kinase PKS5-GST was eluted from glutathione-Sepharose beads with reduced glutathione (50 mM Tris-HCl and 10 mM reduced glutathione, pH 8.0). Phosphorylation assays using either GST-PKS5 (autophosphorylation) or peptide p3 (ALARAASAAALARRR) as substrates were performed as described by Halfter et al. (2000). Kinase buffer contained 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 10 μM ATP, and 1 mM DTT and either 5 mM MgCl2, MnSO4, NaCl, KCl, or CaCl2 as indicated. The kinase reaction (total volume of 20 μL) was started with the addition of 100 μM peptide p3 and 0.5 μL γ-32P-ATP (5 μCi). After incubation at 30°C for 30 min, the reaction was terminated with the addition of 0.5 μL of 0.5 M EDTA and the GST-PKS5 fusion protein was pelleted. For peptide phosphorylation analysis, 10 μL of the supernatant was spotted onto P81 Whatman paper, which was washed with 1% phosphoric acid, and quantified by phosphor imaging (Molecular Dynamics). For analysis of PKS5 autophosphorylation, proteins were separated on a 10% SDS polyacrylamide gel, and after drying, the gel was exposed to x-ray film.

RNAi Constructs and Plant Transformation

For modification of PKS5 expression by RNAi, a 299-bp DNA fragment from PKS5 CDS of 961 to 1260 bp was used. This gene-specific cDNA fragment of PKS5 was amplified by PCR using the following primer pairs: forward primer 5′-CGGGATCCATTTAAATTTGTCGGGATTGTTTGC-3′ and reverse primer 5′-GGACTAGTGGCGCGCCTGAACCCTGAGTTTACCATTC-3′. The forward primer contained BamHI and SwaI restriction sites (underlined) and the reverse primer SpeI and AscI restriction sites (underlined). The PKS5 PCR fragment was first cloned into the pFGC1008 vector (http://ag.arizona.edu/chromatin/fgc1008.html) between the SwaI and AscI sites in the antisense orientation. The sense fragment was then inserted between the BamHI and SpeI sites. The PKS5 RNAi construct was introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 and transformed into wild-type (Col ecotype) plants by floral infiltration.

TILLING Mutants and T-DNA Lines

EMS mutant alleles of pks5 were generated by the Targeting Induced Local Lesions in Genomes service (Greene et al., 2003; http://tilling.fhcrc.org:9366). The T-DNA line of pks5 was from the Salk T-DNA collection. Homozygous lines were identified using PKS5 gene-specific primers and T-DNA left border primers: PKS5F, 5′-ATGCCAGAGATCGAGATTGCC-3′; PKS5R, 5′-AATAGCCGCGTTTGTTGACGAC-3′; LBb1, 5′-AACCAGCGTGGACCGCTTGCTGC-3′; and LBa1, 5′-TTTTTCGCCCTTTGACGTTGGAG-3′.

Plant Growth as a Function of pH

Sterilized seeds were sown on MS media at pH 5.8 containing 1.2% (w/v) agar, stratified for 3 d at 4°C, and then transferred to 22°C in continuous light. Seedlings were transferred to MS media at the test pH (5.8, 7.5, 8.0, 8.2, or 8.4). To assess the effect of pH on germination, sterilized wild-type and PKS5 RNAi seeds were plated directly on MS media at the test pH (5.8, 7.5, 8.2, 8.4, 8.6, and 9.0). The pH of the media was adjusted by titration with HCl or KOH, without using buffers or with 200 mM Bicine, pH 8.2. Percentage of seedling germination was measured 2 weeks later.

Plasma Membrane Isolation and H+ Transport Activity

Isolation of plasma membrane vesicles was by two-phase partitioning as described (Qiu et al., 2002) from rosette plants grown in soil (pH ∼7.5). To characterize the activity of the PM H+-ATPase, its H+ transport activity was measured as described (Qiu et al., 2002) using 50 μg of plasma membrane protein. Recombinant PKS5 protein (100 ng GST-PKS5) was preincubated for 7 min at room temperature with plasma membrane vesicles isolated from pks5#9 RNAi plants; the assay was initiated by the addition of MgSO4.

Protein Interaction Assays

To determine if there is a physical interaction between the PKS5 and SCaBP1 proteins, the yeast two-hybrid system was employed as described (Halfter et al., 2000). To test whether PKS5 interacts with SCaBP1 in vivo, a MYC-tag was translationally fused to the C-terminal end of PKS5 and an HA-tag was fused to the C-terminal end of SCaBP1; both constructs were under the control of a double 35S promoter. The plasmids were either cotransformed or transformed singly into wild-type Arabidopsis protoplasts. Protoplast transient expression assays were performed as described by Sheen (2001). After 10 to 12 h of incubation, protoplasts were harvested and protein extracts were prepared using 105 protoplasts per 100 μL extraction buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 2 μM leupeptin, and 2 μM pepstatin). Anti-HA antibody (Invitrogen) was used for protein immunoprecipitation, and immunoblot analysis was performed using an anti-Myc antibody (Sigma-Aldrich). Both anti-Myc and anti-HA antibodies were used at a 1:100 dilution.

Purification of the PM H+-ATPase from Arabidopsis

To isolate the PM H+-ATPase, membrane vesicles (25 μg) were incubated in a buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 300 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, and 3% Triton X-100) containing a mixture of antibodies (5 μL each) generated from the central loop and N- and C-terminal domains of the PM H+-ATPase from Arabidopsis (Palmgren et al., 1991). After incubation at 4°C for 2 h, Protein A beads (20 μL) were added to the solution and the incubation continued for an additional 12 h at 4°C. The Protein A beads (with the PM H+-ATPase) were subsequently isolated by centrifugation (1000 rpm) and washed three times with the same buffer without antibodies but with 0.25% Triton X-100 and used in phosphorylation assays. The presence of PM H+-ATPase on the Protein A beads was confirmed by protein gel blotting.

In Vitro Phosphorylation of PM H+-ATPase

An equal amount of beads was used for a kinase assay. The kinase assay buffer contained 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 10 μM ATP, and 1 mM DTT. The kinase reaction was started with the addition of 0.5 μL [γ-32P]ATP (5 μCi). After incubation at 30°C for 30 min, the reaction was terminated with the addition of 0.5 μL of 0.5 M EDTA.

In vitro phosphorylation of recombinant AHA2 by GST-PKS5 was performed in a total volume of 50 μL containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and 6 mM MgCl2 plus 0.4 mg/mL BSA. The reaction was started by the addition of 100 μM ATP and 1 μCi [γ-32P]ATP. After 30 min of incubation at 30°C, the reaction was stopped by addition of 50 μL of 22% trichloroacetic acid. The protein was precipitated, resuspended in Laemmli sample buffer, and subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE. After staining and drying the gel, phosphorylation was detected using a Storm 860 scanner (Molecular Dynamics).

Ca2+ Binding Assays

For Ca2+ binding assays, recombinant SCaBP1 protein was run on an SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to nitrocellulose. After transfer, the membrane was washed three times in a solution containing 10 mM imidazole-HCl, pH 6.8, 60 mM KCl, and 5 mM MgCl2. The membrane was then incubated in the same buffer with 37 kBq/mL 45Ca2+ for 10 min, rinsed with distilled water for 30 min, air-dried, and exposed to x-ray film for 3 d.

Cytosolic Ca2+ Imaging

To detect cytosolic-free Ca2+ changes when plants were exposed to high external pH, transgenic plants containing a chimeric 35S:aequorin gene were used (Knight et al., 1991). The transgenic seeds were germinated on MS medium, and 4-d-old seedlings were submerged in 10 μM coelenterazine in water and incubated in the dark at room temperature overnight. The seedlings were then transferred to two-compartment Petri dishes. One compartment had Whatman filter paper saturated with MS nutrient solution at pH 5.7 and the other at pH 8.5. Immediately after the transfer, seedlings were imaged using a cooled CCD camera, and the bioluminescence images were taken as described (Ishitani et al., 1997).

Yeast Complementation Assays

Modification of the yeast expression vector pFL61 was made as follows: the URA3 gene was removed by BglII digestion. The ADE1 and HIS4 genes were amplified from yeast genomic DNA by PCR and inserted into the BglII site of pFL61, resulting in pMP1612 and pMP1645, respectively. NotI sites were added to PCR amplified PKS5 and SCaBP1 genes, the products were sequenced and ligated into the NotI-digested pMP1612 and pMP1645 plasmids, resulting in pMP1648 and pMP1646, respectively. For expression of AHA2, the polylinker in the centromeric yeast vector pRS413 (Stratagene) was removed by digestion with ApaI and SacI, a linker containing a HindIII site was inserted at this position, and AHA2, including the PMA1 promoter and terminator, was inserted as a HindIII fragment, resulting in pMP1745. To generate aha2 mutants, the AHA2 gene was removed by XhoI and SpeI and mutagenized genes inserted as XhoI-SpeI fragments.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain RS-72 (Mat a; ade1-100 his4-519 leu2-3,312 pPMA1∷pGAL1) was used for complementation tests (Fuglsang et al., 2003). Each experiment was replicated independently three times, each time with cells from three independent transformation events.

Biochemistry of PM H+-ATPase

Purification of recombinant His-tagged full-length H+-ATPase (pMP 691) and His-tagged AHA2Δ73 (pMP652) mutant was performed as described by Buch-Pedersen et al. (2000). Isolation of plasma membrane protein from the yeast strain RS-72 was performed essentially as previously described (Axelsen et al., 1999).

Peptide Inhibition Assay

Peptides covering AHA2 residues 925 to 948 were synthesized in four different variants by Thistle Research. The modifications were as follows: (1) no modification, (2) a phosphogroup at Thr-947, (3) a phosphogroup at Ser-931, and (4) phosphogroups at both Ser-931 and Thr-947. Recombinant 14-3-3 protein (10 μM) was preincubated with peptide (30 μM) for 30 min before use in an overlay assay essentially as described by Fuglsang et al. (1999).

Antibodies

For protein blotting, the following antibodies were employed: anti-Thr (Zymed), anti-RGS-6x-His (Qiagen), anti-14-3-3 (barley 14-3-3b; Jahn et al., 1997), and anti-H+-ATPase (Palmgren et al., 1991).

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers At2g30360 (PKS5), At1g78300 (GF14 ω 14-3-3), At4g30190 (AHA2), and At5g55990 (SCaBP1).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01GM59138 to J.-K.Z., Department of Energy Grant DE-FG03-93ER20120 to K.S.S., an Australian Research Council Discovery grant to S.S., Danish Research Council Grant 23-04-0241 to A.T.F., and Danish Council for Technology and Innovation Grant 274-05-0269 to M.G.P. We thank Annette Christensen and Lise Girsel for excellent technical assistance.

The authors responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantcell.org) are: Michael G. Palmgren (palmgren@life.ku.dk) and Jian-Kang Zhu (jian-kang.zhu@ucr.edu).

References

- Axelsen, K.B., Venema, K., Jahn, T., Baunsgaard, L., and Palmgren, M.G. (1999). Molecular dissection of the C-terminal regulatory domain of the plant plasma membrane H+-ATPase AHA2: Mapping of residues that when altered give rise to an activated enzyme. Biochemistry 38 7227–7234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babourina, O., Leonova, T., Shabala, S., and Newman, I. (2000). Effect of sudden salt stress on ion fluxes in intact wheat suspension cells. Ann. Bot. (Lond.) 85 759–767. [Google Scholar]

- Buch-Pedersen, M.J., Venema, K., Serrano, R., and Palmgren, M.G. (2000). Abolishment of proton pumping and accumulation in the E1P conformational state of a plant plasma membrane H+-ATPase by substitution of a conserved aspartyl residue in transmembrane segment 6. J. Biol. Chem. 275 39167–39173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, N.H., Pittman, J.K., Zhu, J.K., and Hirschi, K.D. (2004). The protein kinase SOS2 activates the Arabidopsis H+/Ca2+ antiporter CAX1 to integrate calcium transport and salt tolerance. J. Biol. Chem. 279 2922–2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demidchik, V., Bowen, H.C., Maathuis, F.J.M., Shabala, S.N., Tester, M.A., White, P.J., and Davies, J.M. (2002). Arabidopsis thaliana root non-selective cation channels mediate calcium uptake and are involved in growth. Plant J. 32 799–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frias, I., Caldeira, M.T., Perez-Castineira, J.R., Navarro-Avino, J.P., Culianez-Macia, F.A., Kuppinger, O., Stransky, H., Pages, M., Hager, A., and Serrano, R. (1996). A major isoform of the maize plasma membrane H+-ATPase: Characterization and induction by auxin in coleoptiles. Plant Cell 8 1533–1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuglsang, A.T., Borch, J., Bych, K., Jahn, T.P., Roepstorff, P., and Palmgren, M.G. (2003). The binding site for regulatory 14-3-3 protein in plant plasma membrane H+-ATPase: Involvement of a region promoting phosphorylation-independent interaction in addition to the phosphorylation-dependent C-terminal end. J. Biol. Chem. 278 42266–42272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuglsang, A.T., Visconti, S., Drumm, K., Jahn, T., Stensballe, A., Mattei, B., Jensen, O.N., Aducci, P., and Palmgren, M.G. (1999). Binding of 14-3-3 protein to the plasma membrane H+-ATPase AHA2 involves the three C-terminal residues Tyr946-Thr-Val and requires phosphorylation of Thr947. J. Biol. Chem. 274 36774–36780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong, D., Gong, Z., and Zhu, J.K. (2002). Expression, activation and biochemical properties of a novel Arabidopsis protein kinase. Plant Physiol. 129 225–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene, E.A., Codomo, C.A., Taylor, N.E., Henikoff, J.G., Till, B.J., Reynolds, S.H., Enns, L.C., Burtner, C., Johnson, J.E., Odden, A.R., Comai, L., and Henikoff, S. (2003). Spectrum of chemically induced mutations from a large-scale reverse-genetic screen in Arabidopsis. Genetics 164 731–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y., Halfter, U., Ishitani, M., and Zhu, J.K. (2001). Molecular characterization of functional domains in the protein kinase SOS2 that is required for plant salt tolerance. Plant Cell 13 1383–1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hager, A. (2003). Role of the plasma membrane H+-ATPase in auxin-induced elongation growth: Historical and new aspects. J. Plant Res. 116 483–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hager, A., Debus, G., Edel, H.G., Stransky, H., and Serrano, R. (1991). Auxin induces exocytosis and the rapid synthesis of a high-turnover pool of plasma-membrane H+-ATPase. Planta 185 527–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfter, U., Ishitani, M., and Zhu, J.K. (2000). The Arabidopsis SOS2 protein kinase physically interacts with and is activated by the calcium-binding protein SOS3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97 3735–3740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haritatos, E., Ayre, B.G., and Turgeon, R. (2000). Identification of phloem involved in assimilate loading in leaves by the activity of the galactinol synthase promoter. Plant Physiol. 123 929–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper, J.F., Manney, L., DeWitt, N.D., Yoo, M.H., and Sussman, M.R. (1990). The Arabidopsis thaliana plasma membrane H+-ATPase multigene family. Genomic sequence and expression of a third isoform. J. Biol. Chem. 265 13601–13608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishitani, M., Xiong, L., Stevenson, B., and Zhu, J.K. (1997). Genetic analysis of osmotic and cold stress signal transduction in Arabidopsis: Interactions and convergence of abscisic acid-dependent and abscisic acid-independent pathways. Plant Cell 9 1935–1949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn, T., Fuglsang, A.T., Olsson, A., Bruntrup, I.M., Collinge, D.B., Volkmann, D., Sommarin, M., Palmgren, M.G., and Larsson, C. (1997). The 14-3-3 protein interacts directly with the C-terminal region of the plant plasma membrane H+-ATPase. Plant Cell 9 1805–1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn, T.P., Schulz, A., Taipalensuu, J., and Palmgren, M.G. (2002). Post-translational modification of plant plasma membrane H+-ATPase as a requirement for functional complementation of a yeast transport mutant. J. Biol. Chem. 277 6353–6358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelich-Ottmann, C., Weiler, E.W., and Oecking, C. (2001). Binding of regulatory 14-3-3 proteins to the C terminus of the plant plasma membrane H+-ATPase involves parts of its autoinhibitory region. J. Biol. Chem. 276 39852–39857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanczewska, J., Marco, S., Vandermeeren, C., Maudoux, O., Rigaud, J.L., and Boutry, M. (2005). Activation of the plant plasma membrane H+-ATPase by phosphorylation and binding of 14-3-3 proteins converts a dimer into a hexamer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102 11675–11680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita, T., and Shimazaki, K. (1999). Blue light activates the plasma membrane H+-ATPase by phosphorylation of the C-terminus in stomatal guard cells. EMBO J. 18 5548–5558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita, T., and Shimazaki, K. (2002). Biochemical evidence for the requirement of 14-3-3 protein binding in activation of the guard-cell plasma membrane H+-ATPase by blue light. Plant Cell Physiol. 43 1359–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight, H. (2000). Calcium signaling during abiotic stress in plants. Int. Rev. Cytol. 195 269–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight, M.R., Campbell, A.K., Smith, S.M., and Trewavas, A.J. (1991). Transgenic plant aequorin reports the effects of touch and cold-shock and elicitors on cytoplasmic calcium. Nature 352 524–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolukisaoglu, U., Weinl, S., Blazevic, D., Batistic, O., and Kudla, J. (2004). Calcium sensors and their interacting protein kinases: Genomics of the Arabidopsis and rice CBL-CIPK signaling networks. Plant Physiol. 134 43–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lino, B., Baizabal-Aguirre, V.M., and Gonzalez de la Vara, L.E. (1998). The plasma-membrane H+-ATPase from beet root is inhibited by a calcium-dependent phosphorylation. Planta 204 352–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J., and Zhu, J.K. (1998). A calcium sensor homolog required for plant salt tolerance. Science 280 1943–1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]