Abstract

Jasmonates are plant signaling molecules that play key roles in defense against certain pathogens and insects, among others, by controlling the biosynthesis of protective secondary metabolites. In Catharanthus roseus, the APETALA2-domain transcription factor ORCA3 is involved in the jasmonate-responsive activation of terpenoid indole alkaloid biosynthetic genes. ORCA3 gene expression is itself induced by jasmonate. By loss- and gain-of-function experiments, we located a 74-bp region within the ORCA3 promoter, which contains an autonomous jasmonate-responsive element (JRE). The ORCA3 JRE is composed of two important sequences: a quantitative sequence responsible for a high level of expression and a qualitative sequence that appears to act as an on/off switch in response to methyl jasmonate. We isolated 12 different DNA-binding proteins having one of four different types of DNA-binding domains, using the ORCA3 JRE as bait in a yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) one-hybrid transcription factor screening. The binding of one class of proteins bearing a single AT-hook DNA-binding motif was affected by mutations in the quantitative sequence within the JRE. Two of the AT-hook proteins tested had a weak activating effect on JRE-mediated reporter gene expression, suggesting that AT-hook family members may be involved in determining the level of expression of ORCA3 in response to jasmonate.

Jasmonic acid (JA) and its volatile methyl ester (MeJA), collectively called jasmonates, are fatty acid derivatives that are synthesized via the octadecanoid pathway (Turner et al., 2002; Wasternack et al., 2006). Jasmonates are involved in the regulation of a number of processes in plants, including certain developmental processes, senescence, and responses to wounding and pathogen attack (Turner et al., 2002; Wasternack et al., 2006). An important defense response that depends on jasmonates as regulatory signals is the induction of secondary metabolite accumulation (Gundlach et al., 1992; Memelink et al., 2001). JA induces secondary metabolism at the transcriptional level by switching on the coordinate expression of a set of biosynthetic genes (Schenk et al., 2000; Memelink et al., 2001).

The APETALA2 (AP2)-domain transcription factor ORCA3 (octadecanoid-derivative responsive Catharanthus AP2-domain) is a regulator of several genes involved in primary and secondary metabolism, including the strictosidine synthase (STR) gene, leading to terpenoid indole alkaloid biosynthesis in the plant species Catharanthus roseus (van der Fits and Memelink, 2000; Memelink et al., 2001). Expression of the ORCA3 gene, as well as of its target genes, is induced by MeJA (van der Fits and Memelink, 2000). ORCA3 transactivates the STR promoter via sequence-specific binding to a jasmonate- and elicitor-responsive element (JERE; Menke et al., 1999; van der Fits and Memelink, 2001), indicating that ORCA3 is a transcription factor involved in jasmonate signaling.

The expression of the ORCA3 gene itself is rapidly induced by MeJA (van der Fits and Memelink, 2001), which implies that ORCA3 either autoregulates its own gene expression level or, alternatively, that the ORCA3 gene is regulated by one or more upstream transcription factors. The latter option, a transcriptional cascade regulating plant stress-responsive gene expression, has been described in ethylene and cold signaling (Solano et al., 1998; Chinnusamy et al., 2003).

Different (Me)JA-responsive elements (JREs) have been identified in several plant promoters. The promoters of the PI-II (proteinase inhibitor) gene of potato (Solanum tuberosum; Kim et al., 1992) or the soybean (Glycine max) vspB (vegetative storage proteinB) gene (Mason et al., 1993) contain a G-box-like motif within their JA-responsive regions. However, the JREs of other promoters do not contain sequences with similarity to the G box (Rouster et al., 1997; He and Gan, 2001). In Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), a GCC box was found to mediate JA responsiveness of the PLANT DEFENSIN1.2 (PDF1.2) promoter (Brown et al., 2003). The tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) putrescine N-methyltransferase promoter requires both a G box and a GCC motif to respond to jasmonate (Xu and Timko, 2004). The JERE from the Catharanthus STR promoter also contains a core GCC box (Menke et al., 1999). The JERE interacts with the AP2-domain transcription factors ORCA2 and ORCA3 (Menke et al., 1999; van der Fits and Memelink, 2001).

Here, we describe the identification of a bipartite (Me)JRE in the ORCA3 promoter, which is composed of an A/T-rich quantitative sequence determining the expression level and a G-box-like qualitative sequence switching on the (Me)JA response. Using yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) one-hybrid screening, we have isolated four classes of DNA-binding proteins. One class characterized by a single AT-hook DNA-binding motif binds specifically to the quantitative (Me)JA-responsive sequence.

RESULTS

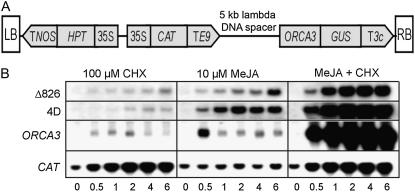

The ORCA3 Promoter Is Responsive to MeJA

ORCA3 mRNA accumulation in suspension-cultured C. roseus cells is rapidly induced by MeJA (van der Fits and Memelink, 2001). To test whether MeJA-induced mRNA accumulation is due to transcriptional activation, we introduced an ORCA3 promoter fragment fused to the GUS reporter gene (Fig. 1A) in suspension-cultured C. roseus cells. Figure 1B shows the expression of the GUS gene driven by the Δ826 ORCA3 promoter extending from positions −826 to −53 relative to the translational start codon. In transgenic cells incubated with MeJA, expression of GUS was induced within 0.5 h and continued to rise up to 6 h. Accumulation of the endogenous ORCA3 transcript was also induced within 0.5 h of treatment with MeJA but thereafter followed different kinetics. To better understand the mechanisms behind these different kinetics, we compared GUS and ORCA3 mRNA accumulation in the presence of the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX). ORCA3 mRNA accumulation is superinduced by a combination of MeJA and CHX (Fig. 1B; van der Fits and Memelink, 2001). Superinduction by CHX is commonly observed with immediate-early response genes in mammalian cells (Edwards and Mahadevan, 1992) and is usually attributed to decreased mRNA degradation. Whereas the kinetics of ORCA3 mRNA accumulation were transient with MeJA alone, the combination of MeJA and CHX caused a steady increase over the 6-h time period. These expression patterns are compatible with a rapid degradation of ORCA3 mRNA after initial accumulation in response to MeJA alone, and mRNA stabilization in the presence of CHX. It is clear that ORCA3 mRNA is rapidly degraded, as shown by a 5-fold reduction in the time interval between 0.5 and 1 h after MeJA treatment. This corresponds to a half-life of around 15 min or even less if transcription of the ORCA3 gene continued during this time, which is suggested by the fact that the ORCA3 Δ826 promoter was active over this time interval. GUS mRNA accumulation driven by the Δ826 promoter was also induced by CHX and superinduced by the combined treatment with CHX and MeJA. However, in this case, similar kinetics with a steady MeJA-responsive increase in the mRNA amounts were observed with or without CHX, which can be explained by a relative stability of the GUS transcript. The relative magnitude of superinduction was much larger for the endogenous ORCA3 transcript than for the GUS transcript, which can also be explained by assuming that the ORCA3 transcript is much more unstable than the GUS transcript. Analysis of CAT (chloramphenicol acetyl transferase) gene expression under the control of the constitutive cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter showed that in response to CHX treatment, the amount of CAT mRNA increased, indicating that it was also stabilized. In contrast to GUS and ORCA3 mRNAs, CAT mRNA was not superinduced by the combined treatment with CHX and MeJA. These results show that MeJA-induced ORCA3 mRNA accumulation is at least partly a transcriptional response. Although we cannot exclude that the endogenous ORCA3 promoter contains additional elements upstream of position 826 that specify the kinetics of ORCA3 mRNA accumulation, the results show that the Δ826 fragment of the ORCA3 promoter shows MeJA-responsive activity and therefore contains a JRE. In the presence of CHX, the MeJA-responsive accumulation of endogenous ORCA3 transcript and ORCA3 promoter-driven GUS transcript showed similar kinetics, indicating that the different kinetics in response to MeJA alone are caused by rapid degradation of the ORCA3 transcript, which suggests that the ORCA3 promoter derivative Δ826 is likely to show the same pattern of MeJA-responsive transcription initiation as the endogenous ORCA3 promoter.

Figure 1.

The ORCA3 promoter contains a MeJA-responsive element. A, Schematic representation of the T-DNA transferred to C. roseus suspension cells in the ORCA3 promoter studies. The CAT and hygromycin phosphotransferase genes are under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter, while GUS is under the control of an ORCA3 promoter derivative. Genes in the T-DNA have terminators from the nopaline synthase gene or the pea (Pisum sativum) ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase-small subunit-encoding E9 or 3C genes. LB and RB, Left and right T-DNA borders. B, mRNA levels of the GUS and CAT transgenes and the endogenous ORCA3 gene in representative transgenic BIX cell lines containing the ORCA3 promoter constructs Δ826-GUS or 4D-GUS-47 treated with 100 μm CHX, 10 μm MeJA, or both compounds combined for different number of hours. Blots shown in the Δ826 and 4D segments were hybridized with a GUS probe. Both cell lines showed identical patterns of CaMV 35S-driven CAT mRNA and endogenous ORCA3 mRNA accumulation. The examples shown here are from the 4D line. Film exposure times were 15 h for GUS and CAT and 48 h for ORCA3.

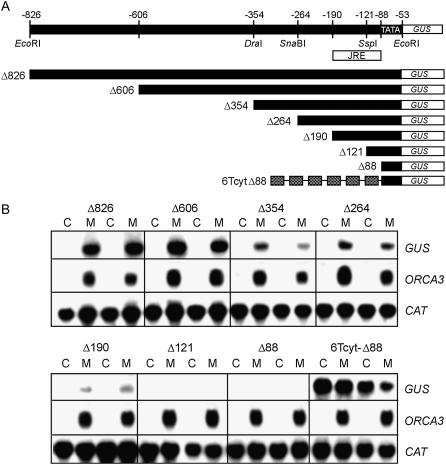

Localizing the JRE by 5′ Deletion Analysis

To locate the JA-responsive region within the Δ826 promoter, the effect of progressive 5′ deletions (Fig. 2A) was analyzed in two independent mixed transgenic cell populations for each construct. Figure 2B shows the expression of the GUS gene driven by deletion derivatives of the ORCA3 promoter in comparison with the expression of the CaMV 35S-CAT transgene and the endogenous ORCA3 mRNA level in the same RNA samples. In transgenic cells harboring the Δ826 or the Δ606 fragments, incubation with MeJA resulted in increased GUS mRNA accumulation compared with the control treatment (Fig. 2B), which was qualitatively similar to endogenous ORCA3 mRNA accumulation. Deletion to positions −354 and −264 did not abolish MeJA inducibility, but the expression levels were somewhat reduced. Further deletion to −190 resulted in a promoter construct with a low level of MeJA-responsive expression. Deletion to −121 and −88 resulted in unresponsive promoter constructs. Analysis of endogenous ORCA3 gene expression showed that the induction treatments were effective. Analysis of CAT gene expression showed equal loading of RNA and similar levels of expression of this control gene on the T-DNA in the different transgenic cell lines (Fig. 2B). These results show that a JRE is located downstream of position −190. To establish whether this JRE is located upstream or downstream of position −88, six head-to-tail copies of the constitutive cyt1 cis-acting element from the T-DNA T-CYT gene (Neuteboom et al., 1993) were fused to the Δ88 construct (Fig. 2A). In cell lines carrying the 6Tcyt-Δ88 construct, high basal levels of GUS mRNA were found, and expression was not inducible with MeJA (Fig. 2B), indicating that there is not a silent JRE downstream of position −88 that could be potentiated by the cyt1 elements. These results show that a JRE is located between positions −190 and −88. The region upstream of position −190 may contain additional JREs or, alternatively, constitutive promoter elements that could contribute to the expression level.

Figure 2.

Localization of the JRE by 5′ deletion analysis of the ORCA3 promoter. A, Schematic representation of 5′ deletion derivatives of the ORCA3 promoter fused to GUS. Construct 6Tcyt-Δ88 contains six copies of the constitutive cyt-1 element of the T-DNA T-CYT gene fused to the ORCA3 Δ88 promoter. The position of the JRE deduced from this analysis is indicated. B, Northern blots showing GUS, ORCA3, and CAT mRNA levels in two independent transgenic BIX cell lines for each deletion construct. Cells were treated with 10 μm MeJA (M) or DMSO (C) at a final concentration of 0.1% for 5 h. Numbering of nts in the ORCA3 promoter is relative to the ATG start codon of translation.

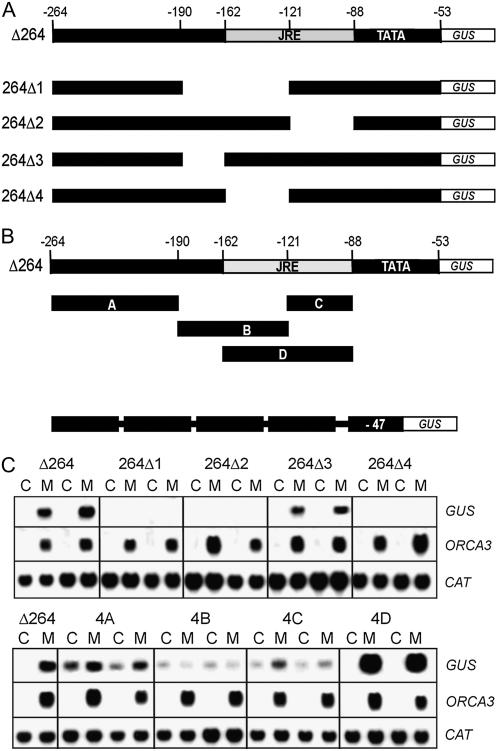

Localizing the JRE by Internal Deletion Analysis

To narrow down the JA-responsive region in the ORCA3 promoter, an internal deletion analysis was performed in the context of the Δ264 promoter (Fig. 3A), which is the shortest promoter derivative still showing relatively strong JA responsiveness. Internal deletions of the −190 to −121, the −162 to −121, or the −121 to −88 regions abolished MeJA responsiveness (Fig. 3C), indicating that the region around position −121 is important for JA-responsive expression. Deletion of a region from positions −190 to −162 did not affect JA responsiveness. These results indicate that the JRE is located between positions −162 and −88 relative to the ATG start codon and further suggest that an important sequence is overlapping position −121.

Figure 3.

Localization of the JRE. A, Schematic representation of internal deletion constructs within the Δ264 context. B, Position of fragments A to D derived from the Δ264 promoter. Fragments were tetramerized and fused to the CaMV 35S minimal promoter and the GUS reporter gene. C, Northern blots showing GUS, ORCA3, and CAT mRNA levels in two independent transgenic BIX cell lines for each construct. Cells were treated for 5 h with 10 μm MeJA (M) or DMSO (C) at a final concentration of 0.1%. Numbering of nts in the ORCA3 promoter is relative to the ATG start codon of translation.

A Fragment Containing the JRE Autonomously Confers MeJA-Responsive Transcriptional Activation

To determine whether regions in the Δ264 promoter are able to confer MeJA-responsive gene expression in a gain-of-function approach, head-to-tail tetramers of four different fragments, called A to D and spanning the −264 to −88 region, were fused to a minimal CaMV 35S promoter (−47 to +27) fused to GUS (Fig. 3B). A cell line harboring the Δ264 construct was used as a reference for the level of MeJA-responsive gene expression. The A tetramer (−264 to −190) conferred a basal expression level onto the GUS gene with a low level of MeJA responsiveness. A tetramer of fragment B (−190 to −121) conferred a low basal expression level, and MeJA caused no positive response but appeared to have even a slight negative effect on the expression level. A tetramer of fragment C (−121 to −88) conferred a low basal level of expression with a clear response to MeJA. As expected from the internal deletion analysis, a tetramer of fragment D (−162 to −88) conferred a high level of MeJA-responsive gene expression, which was much higher than the expression level of the Δ264 promoter. In contrast to the other tetramers, the D tetramer conferred no basal expression level and was in this respect qualitatively similar to the Δ264 promoter. In each cell line, MeJA induced the expression of the endogenous ORCA3 gene to similar levels, and all cell lines expressed the CAT transgene at similar levels (Fig. 3C). These results show that the D region autonomously confers MeJA-responsive gene expression, demonstrating that it carries a JRE. In addition to activating gene expression in response to MeJA, it also appears to silence the basal level of gene expression in the absence of MeJA.

The C fragment, which is a subfragment of D, confers a very low level of MeJA responsiveness, indicating that it contains part, but not all, of a functional JRE. The B fragment, which overlaps for a large part with the D fragment, does not carry any complete JRE. Finally, fragment A appears to carry a weak JRE distinct from the one in the D fragment.

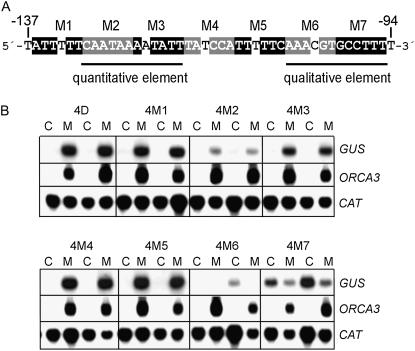

The JRE Is Composed of Two Functionally Distinct Sequences

Block scanning mutagenesis of the D region of the ORCA3 promoter (Fig. 4A) was performed to pinpoint the exact location of the JRE. The activities of seven mutated versions of the tetramerized D fragment were analyzed in two independently transformed C. roseus cell lines for each construct. By comparing basal and MeJA-induced GUS gene expression for each mutant line to the expression conferred by the wild-type D tetramer, mutants M1, M4, and M5 were found to confer wild-type MeJA responsiveness (Fig. 4B). With mutation M2 and to some degree M3, the activation of GUS expression by MeJA treatment was significantly reduced, but expression was still induced. Mutant M6 and especially M7 conferred a basal expression level, which is actually reduced in response to MeJA. In each cell line, MeJA induced the expression of the endogenous ORCA3 gene to similar levels, and all cell lines expressed the CAT transgene at similar levels. These results revealed the presence of two different sequence elements in the D region. The first sequence is located in the region covered by mutations M2 and M3 around position −121 and seems to be necessary for a high level of expression, which we therefore call a quantitative sequence. The second sequence, situated in the region covered by mutations M6/M7, seems to be necessary to silence the basal expression level, and it activates transcription in response to MeJA. Therefore, this is a qualitative sequence, which acts as an on/off switch in response to MeJA.

Figure 4.

Block scanning mutagenesis identified two sequences in the D region of the ORCA3 promoter that are important for the MeJA response. A, The wild-type sequence of the D region is shown. Numbering of mutations is given above the sequence. In each mutant, boxed nts were changed into their complementary nt. B, Northern blots showing GUS, ORCA3, and CAT mRNA levels in two independent transgenic BIX cell lines for each construct. Cells were incubated for 5 h with 10 μm MeJA (M) or DMSO (C) at a final concentration of 0.1%.

Isolation of cDNAs Encoding Proteins Binding to Fragment D

In a first approach, the D region of the ORCA3 promoter was used as bait in a yeast one-hybrid transcription factor screening. Derivatives of yeast strain Y187, containing one or two copies of the D fragment fused to the HIS3 selection marker, were used in a one-hybrid screen for DNA-binding proteins with an expression library of C. roseus cells treated with MeJA, where cDNAs were cloned in a fusion with the GAL4 activation domain in the yeast expression vector pAD-GAL4-2.1. A total of 2.4 × 106 Y187-1D and 4.1 × 106 Y187-2D transformants were screened. Eighteen plasmids were isolated that conferred increased growth in Y187-1D and Y187-2D compared with the Y187 control, which corresponded to eight different mRNA species (Table I). These eight species can be divided in three classes. The first class is represented by the single clone 2D81 encoding a protein with homology to a poorly characterized family of putative zinc-finger transcription factors (Kuusk et al., 2006). Another class is constituted of two clones encoding proteins containing a DNA-binding homeodomain (HD) followed by the Leu zipper (Zip) protein dimerization motif. The last class comprises five clones encoding proteins containing a DNA-binding AT-hook motif and a conserved region known as domain of unknown function (DUF) 296, which is found in certain plant proteins and is hypothesized to be involved in DNA binding based on its invariable cooccurrence with the AT-hook motif.

Table I.

Classification of one-hybrid clones

| Longest Clonea | No. Clonesb | Classc | Insert Lengthd | GenBank Accession No.e |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D81 | 1 | Zinc-finger | 1,336 | EF025303 |

| 2D206 | 3 | HD-ZIP | 1,173 | EF025304 |

| 2D21 | 2 | HD-ZIP | 1,023 | EF025305 |

| 2D328 | 2 | AT-hook | 825 | EF025306 |

| 2D173 | 2 | AT-hook | 1,352 | EF025307 |

| 2D449 | 2 | AT-hook | 1,027 | EF025308 |

| 2D38M, 2D1 | 4 | AT-hook | 1,180 | EF025309 |

| 2D7 | 3 | AT-hook | 1,327 | EF025310 |

| 4C19 | 28 | 1R-MYB | 1,601 | EF025311 |

| 4C32 | 5 | 1R-MYB | >1,429 | EF025312 |

| 4C49 | 38 | 1R-MYB | 1,396 | EF025313 |

| 4C80, 4C87 | 11 | 1R-MYB | 1,286 | EF025314 |

The longest clone of each cDNA species is in the first position; the second clone, if any, was used to produce GST fusion protein.

Number of cDNAs corresponding to the same mRNA species.

Type of DNA-binding motif.

Insert length without linker sequences of the longest clone in base pairs. >, cDNA 3′ UTR was not fully sequenced.

Accession number for the longest clone.

In another approach, a Y187-derived yeast strain containing four copies of the C element fused to the HIS3 selection gene was screened with an expression library of C. roseus cells treated with yeast extract, where cDNAs were cloned into the vector pACTII. Screening of 2.5 × 106 transformants yielded 87 colonies, of which 82 contained plasmids encoding single-repeat MYB transcription factors falling in four different related families (Table I).

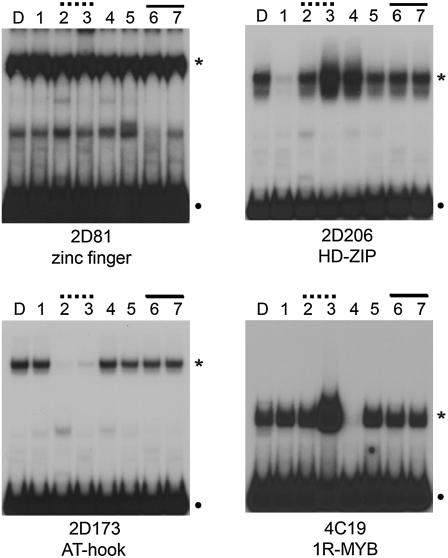

The AT-Hook Proteins Interact with the Quantitative JA-Responsive Sequence

To test whether mutation of the two distinct sequences within the D region of the ORCA3 promoter impaired binding of the DNA-binding proteins encoded by the one-hybrid clones, glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged proteins produced in Escherichia coli and D fragment variants were used in electrophoretic mobility shift assays. The 2D81 protein bound wild-type D fragment as well as all its mutated versions (Fig. 5), indicating that the encoded protein is not specific for the D element or that its binding site is located outside the mutated region. Both HD-Zip proteins 2D206 and 2D21 seemed to bind better to mutated D fragments M3 and M4 and showed reduced binding to mutated D fragment M1 compared to binding to the wild-type D fragment (Fig. 5; results not shown). The M1 mutation has no effect on MeJA responsiveness of the D region in Catharanthus cells. Binding of the four classes of single-repeat MYB proteins was impaired by mutation M4 (Fig. 5; results not shown), which has no effect on MeJA responsiveness of the D region in vivo. Binding of the zinc-finger, HD-Zip, and 1R-MYB classes of proteins was not affected by mutations in the two jasmonate-responsive sequences, suggesting that these proteins are not involved in the MeJA responsiveness or the level of expression conferred by the D fragment. All five AT-hook proteins did not bind to mutated D fragments M2 and M3 but did bind to the M1, M4, M5, M6, and M7 fragments (Fig. 5; results not shown). The importance of the M2/M3 region for binding of AT-hook proteins indicates that these transcription factors may be responsible for activation of gene expression mediated by the quantitative sequence.

Figure 5.

In vitro binding of proteins encoded by representative one-hybrid clones of each class to wild-type or mutated derivatives of fragment D. Fragments indicated at the top of each segment were used as probes in in vitro binding assays using the protein indicated at the bottom of each segment. D represents wild-type D fragment, and numbers 1 to 7 represent mutated fragments M1 to M7 as shown in Figure 4A. Mutations affecting the quantitative sequence and the qualitative sequence are overlined with broken and solid lines, respectively. Dots indicate free probes, whereas asterisks indicate specific DNA-protein complexes. All members of each class gave qualitatively similar binding patterns to the example shown here (data not shown).

AT-Hook Proteins Are Weak Activators and Are Not Transcriptionally Induced by MeJA

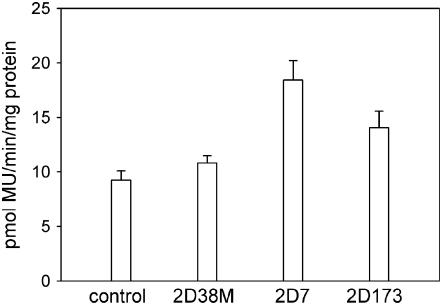

To test the hypothesis that the AT-hook proteins are activators of transcription via the D element, transactivation assays were conducted. Clones 2D173, 2D38M, and 2D7 were selected for these experiments, because they possibly contain the full-length coding regions, whereas the other two clones are obviously incomplete. As shown in Figure 6, 2D7 and 2D173 caused 2- and 1.5-fold increases, respectively, in GUS reporter gene expression, whereas 2D38M had little or no effect.

Figure 6.

Transactivation analysis of AT-hook proteins. Effect of AT-hook proteins expressed from the CaMV 35S promoter on 4D-GUS-47 reporter gene expression in bombarded cells of C. roseus cell line MP183L. Means of triplicate bombardments corrected for protein amounts with ses are shown.

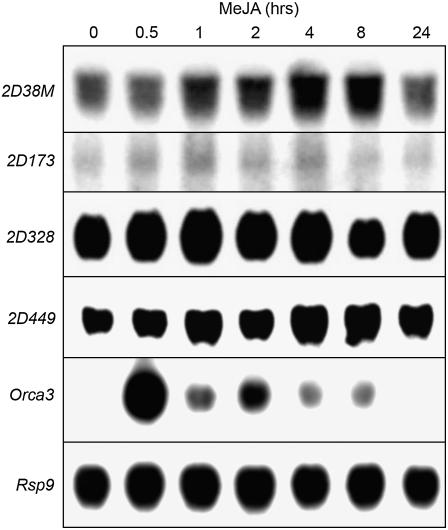

To study whether the AT-hook proteins could possibly contribute to the MeJA responsiveness of the ORCA3 promoter as a result of increased protein abundance due to stimulation of AT-hook gene expression by MeJA, the mRNA levels corresponding to the AT-hook clones were determined in a MeJA time course. Although we were unable to obtain detectable hybridization with clone 2D7, mRNA species hybridizing to clones 2D38M, 2D173, 2D328, and 2D449 showed little or no variation in abundance after MeJA treatment within a 24-h time course (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

AT-Hook gene expression analysis. Northern blots showing mRNA levels corresponding to AT-hook genes, ORCA3, and the Rps9 control gene. MP183L cells were treated with 10 μm MeJA for different number of hours.

DISCUSSION

Using transgenic C. roseus cell suspensions harboring ORCA3 promoter-GUS fusions, we have demonstrated that MeJA-induced accumulation of ORCA3 mRNA occurs at the transcriptional level. By loss- and gain-of-function experiments, we located a 74-bp region within the ORCA3 promoter containing an autonomous JRE. Block scanning mutagenesis revealed two important sequences within the JRE: a quantitative sequence responsible for a high level of expression and a qualitative sequence that acts as an on/off switch in response to MeJA. Moreover, we identified by one-hybrid screening five clones of related AT-hook transcription factors, which bind specifically to the quantitative sequence in the ORCA3 JRE. Two of them were found to have a weak activating effect on D-mediated reporter gene expression, indicating that AT-hook family members are possibly involved in determining the level of expression conferred by the JRE in response to jasmonate.

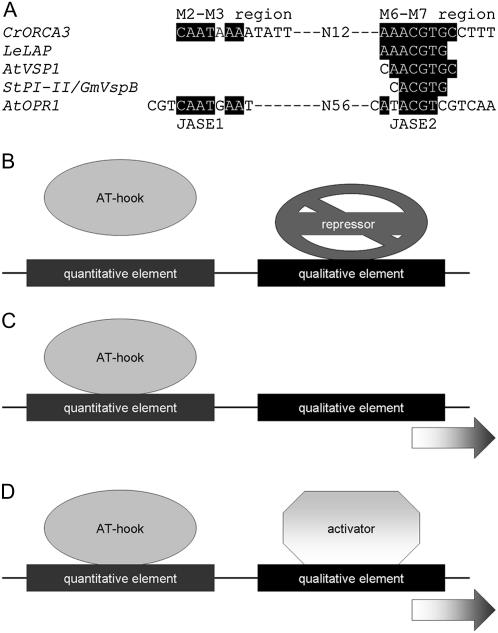

A range of motifs has been found to be responsible for JA-induced transcription of various genes. A region containing an ACCGCC sequence, which binds the ORCA3 transcription factor (van der Fits and Memelink, 2001), is responsible for the MeJA-responsive expression of the STR gene in Catharanthus cells (Menke et al., 1999). A similar sequence (GCCGCC) was found to modulate the JA responsiveness of the PDF1.2 promoter in Arabidopsis (Brown et al., 2003). There are no significant similarities between the GCC box and the two JA-responsive sequences in the ORCA3 JRE. However, the qualitative sequence contains a G box (CACGTG) with one mismatch and is in fact a T/G hybrid box composed of T-box and G-box half sites, according to the terminology in Foster et al. (1994). The same T/G box (Fig. 8A) was found in the promoter of the LAP (Leu aminopeptidase) gene of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). This element was shown to be responsible for the JA-responsive activation of this gene and was shown also to be bound by two basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factors (Boter et al., 2004). In addition, in the Arabidopsis VSP1 gene, a G box with one mismatch, which is very similar to the ORCA3 T/G box (Fig. 8A), was pointed out as a JRE (Guerineau et al., 2003). G boxes are present in the JA-responsive promoter regions of the soybean VSPB gene (Mason et al., 1993) and the potato PI-II gene (Kim et al., 1992). In tobacco, the MeJA-induced expression of the putrescine N-methyltransferase gene involves a G box and is also dependent on a GCC box (Xu and Timko, 2004). Two JREs, JASE1 (5′-CGTCAATGAA-3′) and JASE2 (5′-CATACGTCGTCAA-3′), were identified in the promoter of the OPR1 gene from Arabidopsis (He and Gan, 2001). Although JASE2 does not contain a G box, it does contain the ACGT core element. Both JASE1 and JASE2 show some similarities to the sequences in the ORCA3 JRE (Fig. 8A). The lack of a GCC box in the ORCA3 JRE indicates that the ORCA3 promoter is not regulated by an AP2-domain transcription factor, including one of the ORCAs. In agreement with this notion, we did not observe specific binding of ORCA3 or the related ORCA2 to the ORCA3 promoter and, in addition, did not observe activation of the ORCA3 promoter by either ORCA protein in transient transactivation assays in Catharanthus cells (D. Vom Endt and J. Memelink, unpublished data). Therefore, JA-responsive expression of the ORCA3 gene appears to be controlled by at least two different types of upstream transcription factors distinct from the ORCAs binding to the quantitative and qualitative sequences.

Figure 8.

JA-responsive expression conferred by the bipartite JRE. A, Comparison of JREs. Alignment of JREs in the promoters of the genes encoding Catharanthus ORCA3 (CrORCA3), tomato (LeLAP), Arabidopsis (AtVSP1), potato (StPI-II), soybean (GmVspB), and Arabidopsis 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid-10,11-reductase (AtOPR1). Similarities with the ORCA3 JRE are highlighted. B to D, Models for JA-responsive expression conferred by the bipartite JRE. B, Without JA, a repressor protein is bound to the qualitative DNA sequence, silencing expression. In the presence of JA, the repressor is inactivated, allowing expression following binding of AT-hook protein to the quantitative sequence (C), or the qualitative sequence binds an activator protein (D), which stimulates expression together with the AT-hook protein. In the latter case, the AT-hook protein can be DNA bound irrespective of the presence of JA. Activator in D and repressor in B can be differently modified forms of the same protein.

Using the D and C fragments in one-hybrid screening, we have isolated four classes of DNA-binding proteins with possible roles in regulation of gene expression. Analysis of binding in vitro revealed that only the binding of the AT-hook class of proteins was affected by mutations in a sequence important for the jasmonate-responsive activity of the D region. The AT-hook proteins have impaired binding to mutated D derivatives M2 and M3. This region of the D fragment defines the quantitative JA-responsive sequence (Fig. 4). Therefore, one or more of the AT-hook proteins is probably responsible for the activity of the quantitative sequence. In accordance with this notion, two of the AT-hook proteins had an activating effect on D element-mediated gene expression. The weak transactivation effect observed is in line with the relatively mild effect of the M2 and M3 mutations on the D-mediated gene expression level. The AT-hook motif was first identified in the high mobility group I(Y) [HMG-I(Y)] nonhistone chromosomal proteins, which contain three copies of this motif (Aravind and Landsman, 1998). The AT-hook motif is a nine-amino acid sequence with a central highly conserved Gly-Arg-Pro core, which binds to the minor groove of AT-rich DNA. The HMG-I(Y) proteins are thought to coregulate transcription by modifying the architecture of DNA, thereby enhancing the accessibility of promoters to transcription factors. Following its original identification, the AT-hook motif has been found in a large number of proteins as single or multiple copies, often associated with one or more other DNA-binding domains (Aravind and Landsman, 1998). Plants have a class of AT-hook proteins, which is characterized by an N-terminal histone H1 globular domain followed by multiple (4–15) AT-hook motifs (Meijer et al., 1996). The pathogenesis-related HD protein from parsley (Petroselinum crispum) contains four AT-hook motifs combined with a HD and a zinc-finger-like PHD finger (Korfhage et al., 1994). The Catharanthus AT-hook proteins described here contain only a single copy of the AT-hook motif, which is followed by a conserved DUF296 thought to be a DNA-binding domain based on its invariable association with the AT-hook motif. Currently, all classes of plant AT-hook proteins are poorly characterized at the functional level, with a total absence of functional information for the single AT-hook/DUF296 class.

Unfortunately, in this one-hybrid screening, DNA-binding proteins able to bind specifically to the qualitative sequence were not found. Based on its similarity to the LAP promoter element (Boter et al., 2004) and its identity as a T/G box, the qualitative sequence in the ORCA3 promoter is likely to bind a bHLH transcription factor. Our inability to isolate this putative bHLH transcription factor via yeast one-hybrid screening may be due to the fact that it binds as a heterodimer or to the necessity for plant-specific modifications for binding. If the qualitative sequence indeed binds a bHLH transcription factor, the regulation of ORCA3 expression would show similarity to the regulation of the genes encoding CBF (C-repeat binding factor) AP2-domain proteins involved in cold-responsive gene expression in Arabidopsis. The cold-responsive expression of the CBF genes is controlled by the bHLH transcription factor INDUCER OF CBF EXPRESSION1 (Chinnusamy et al., 2003). A G box in the STR promoter was also shown to bind bHLH proteins (Pré et al., 2000; Chatel et al., 2003). It is interesting in this context that the gene encoding the bHLH protein CrMYC1 showed JA-responsive expression (Chatel et al., 2003). The STR G box also binds two bZIP proteins called G-box binding factor1 (CrGBF1) and CrGBF2, which acted as repressors of this promoter in transient assays (Sibéril et al., 2001). By analogy, one or more GBFs could also act as repressors via binding to the qualitative sequence within the ORCA3 promoter, which would fit well with the fact that the qualitative sequence represses basal expression levels in a noninduced state.

Our current model is that the quantitative sequence in the JRE is bound by one or more transcriptional activators, which confer a high level of ORCA3 expression in response to (Me)JA. The AT-hook transcription factors isolated in the one-hybrid screening are likely to fulfill the role of these activators (Fig. 8). The qualitative sequence, on the other hand, seems to bind a repressor in the noninduced state (Fig. 8B). Activation could be conferred by binding of an AT-hook protein to the quantitative sequence upon release of the qualitative sequence from repression (Fig. 8C), in which case the qualitative sequence would only be an off switch. Alternatively, and more likely in our opinion, the qualitative sequence could also bind an (bHLH-type) activator in the induced state (Fig. 8D). In the later case, repressor and activator could be different proteins or could be the same (bHLH) protein switching between two activity states.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of ORCA3 Promoter-GUS Fusions

ORCA3 promoter deletions were generated by PCR or using internal restriction sites and cloned into reporter plasmid GusXX. Six copies of the Tcyt element were cloned into Δ88GusXX to generate the control construct 6Tcyt-Δ88GusXX. ORCA3 promoter fragments A to D were generated by PCR or using internal restriction sites, tetramerized, and cloned in reporter plasmid GusSH-47. Block mutations M1 to M7 were introduced in the D fragment via PCR using the Stratagene Quickchange protocol. In each mutant, six or five adjacent nucleotides (nts) were changed into their complementary nt, i.e. changing A to T and G to C (Fig. 4A). The seven mutated versions of the D fragment were tetramerized and cloned into GusSH-47. Promoter-GUS fusions were transferred to the binary vector pMOG22λCAT (Menke et al., 1999). Cloning details can be found in the supporting information and are available on request.

Cell Culture, Transformation, and Treatments

Catharanthus roseus cell line BIX was transformed using Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Each transgenic cell line was a mixed population estimated to consist of thousands of independent transformants. Transgene expression level therefore reflected an average largely independent of T-DNA chromosomal position or copy number. For each construct, two independent mixed transgenic cell populations were generated and analyzed. Cell suspension cultures were treated 4 d after transfer with 10 μm MeJA (Bedoukian Research) diluted in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) at a final concentration of 0.1% (v/v). Control cultures were treated with DMSO only. In the CHX experiments, cells were treated with 100 μm CHX (Sigma) and/or 10 μm MeJA at final concentrations of 0.2% (v/v) DMSO.

Yeast One-Hybrid Screening

A monomer and a dimer of the D fragment and a tetramer of the C fragment were fused to a TATA box-HIS3 gene. HIS3 gene constructs were integrated in the genome of yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) strain Y187 by homologous recombination. After transformation of the cDNA libraries in the 1D, 2D, and 4C yeast strains, cells were plated on synthetic dextrose minimal medium lacking Leu and His supplemented with 5, 15, and 5 mm 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (Sigma), respectively. Colonies were patched on medium containing 20 μg/mL X-α-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-α-d-galactopyranoside; BD Biosciences, CLONTECH) to check for specific activation of HIS3 gene expression based on lack of MEL1 gene activation.

Isolation of Recombinant Proteins

The inserts from selected one-hybrid plasmids (Table I) were cloned into pGEX-KG or pGEX-4T1. GST fusion proteins were isolated using glutathione Sepharose 4B beads (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Transient Expression Assays

C. roseus cells of cell line MP183L were transformed by particle bombardment as described (Menke et al., 1999). Cells were cobombarded in triplicate with 1 μg of the 4D-GUS-47 reporter construct and 8 μg of an overexpression vector carrying an AT-hook clone fused in sense orientation to the CaMV 35S promoter (see Supplemental Data S1 for cloning details). Cells were harvested 24 h later and frozen in liquid nitrogen. GUS activity assays were performed as described (Menke et al., 1999), and protein concentrations were measured using Bradford protein assay reagent (Bio-Rad).

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers EF025303 to EF025314.

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Data S1. Detailed Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ward de Winter for assistance with tissue culturing.

This work was supported by a Socrates/Erasmus grant (to M.S.S.).

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantphysiol.org) is: Johan Memelink (j.memelink@biology.leidenuniv.nl).

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

References

- Aravind L, Landsman D (1998) AT-hook motifs identified in a wide variety of DNA-binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 26 4413–4421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boter M, Ruíz-Rivero O, Abdeen A, Prat S (2004) Conserved MYC transcription factors play a key role in jasmonate signaling both in tomato and Arabidopsis. Genes Dev 18 1577–1591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RL, Kazan K, McGrath KC, Maclean DJ, Manners JM (2003) A role for the GCC-box in jasmonate-mediated activation of the PDF1.2 gene of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 132 1020–1032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatel G, Montiel G, Pré M, Memelink J, Thiersault M, Saint-Pierre B, Doireau P, Gantet P (2003) CrMYC, a Catharanthus roseus elicitor- and jasmonate-responsive bHLH transcription factor that binds the G-box element of the strictosidine synthase gene promoter. J Exp Bot 54 2587–2588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnusamy V, Ohta M, Kanrar S, Lee B-H, Hong X, Agarwal M, Zhu J-K (2003) ICE1: a regulator of cold-induced transcriptome and freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev 17 1043–1054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards DR, Mahadevan LC (1992) Protein synthesis inhibitors differentially superinduce c-fos and c-jun by three distinct mechanisms: lack of evidence for labile repressors. EMBO J 11 2415–2424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster R, Izawa T, Chua NH (1994) Plant bZIP proteins gather at ACGT elements. FASEB J 8 192–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerineau F, Benjdia M, Zhou DX (2003) A jasmonate-responsive element within the A. thaliana vsp1 promoter. J Exp Bot 54 1153–1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundlach H, Müller MJ, Kutchan TM, Zenk MH (1992) Jasmonic acid is a signal transducer in elicitor-induced plant cell cultures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89 2389–2393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Gan S (2001) Identical promoter elements are involved in the regulation of the OPR1 gene by senescence and jasmonic acid in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol 47 595–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S-R, Choi J-L, Costa MA, An G (1992) Identification of G-box sequence as an essential element for methyl-jasmonate response of potato proteinase inhibitor II promoter. Plant Physiol 99 627–631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korfhage U, Trezzini GF, Meier I, Hahlbrock K, Somssich IE (1994) Plant homeodomain protein involved in transcriptional regulation of a pathogen defense-related gene. Plant Cell 6 695–708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuusk S, Sohlberg JJ, Magnus Eklund D, Sundberg E (2006) Functionally redundant SHI family genes regulate Arabidopsis gynoecium development in a dose-dependent manner. Plant J 47 99–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason HS, DeWald DB, Mullet JE (1993) Identification of a methyl jasmonate-responsive domain in the soybean vspB promoter. Plant Cell 5 241–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer AH, van Dijk EL, Hoge JHC (1996) Novel members of a family of AT hook-containing DNA-binding proteins from rice are identified through their in vitro interaction with consensus target sites of plant and animal homeodomain proteins. Plant Mol Biol 31 607–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memelink J, Verpoorte R, Kijne JW (2001) ORCAnisation of jasmonate-responsive gene expression in alkaloid metabolism. Trends Plant Sci 6 212–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menke FLH, Champion A, Kijne JW, Memelink J (1999) A novel jasmonate- and elicitor-responsive element in the periwinkle secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene Str interacts with a jasmonate- and elicitor-inducible AP2-domain transcription factor, ORCA2. EMBO J 18 4455–4463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuteboom STC, Stoffels A, Hulleman E, Memelink J, Schilperoort RA, Hoge JHC (1993) Interaction between the tobacco DNA-binding activity CBF and the cyt-1 promoter element of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens T-DNA gene T-CYT correlates with cyt-1 directed gene expression in multiple tobacco tissue types. Plant J 4 525–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pré M, Sibéril Y, Memelink J, Champion A, Doireau P, Gantet P (2000) Isolation by the yeast one-hybrid system of cDNAs encoding transcription factors that bind to the G-box element of the strictosidine synthase gene promoter from Catharanthus roseus. Int J Bio-Chromatogr 5 229–244 [Google Scholar]

- Rouster J, Leah R, Mundy J, Cameron-Mills V (1997) Identification of a methyl jasmonate-responsive region in the promoter of a lipoxygenase 1 gene expressed in barley grains. Plant J 11 513–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk PM, Kazan K, Wilson I, Anderson JP, Richmond T, Somerville SC, Manners JM (2000) Coordinated plant defense responses in Arabidopsis revealed by microarray analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97 11655–11660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibéril Y, Benhamron S, Memelink J, Giglioli-Guivarc'h N, Thiersault M, Boisson B, Doireau P, Gantet P (2001) Catharanthus roseus G-box binding factors 1 and 2 act as repressors of strictosidine synthase gene expression in cell cultures. Plant Mol Biol 45 477–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solano R, Stepanova A, Chao Q, Ecker JR (1998) Nuclear events in ethylene signaling: a transcriptional cascade mediated by ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE3 and ETHYLENE RESPONSE-FACTOR1. Genes Dev 12 3703–3714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JG, Ellis C, Devoto A (2002) The jasmonate signal pathway. Plant Cell (Suppl) 14 S153–S164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Fits L, Memelink J (2000) ORCA3, a jasmonate-responsive transcriptional regulator of plant primary and secondary metabolism. Science 289 295–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Fits L, Memelink J (2001) The jasmonate-inducible AP2/ERF-domain transcription factor ORCA3 activates gene expression via interaction with a jasmonate-responsive promoter element. Plant J 25 43–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasternack C, Stenzel I, Hause B, Hause G, Kutter C, Maucher H, Neumerkel J, Feussner I, Miersch O (2006) The wound response in tomato: role of jasmonic acid. J Plant Physiol 163 297–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu B, Timko M (2004) Methyl jasmonate induced expression of the tobacco putrescine N-methyltransferase genes requires both G-box and GCC-motif elements. Plant Mol Biol 55 743–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.