Abstract

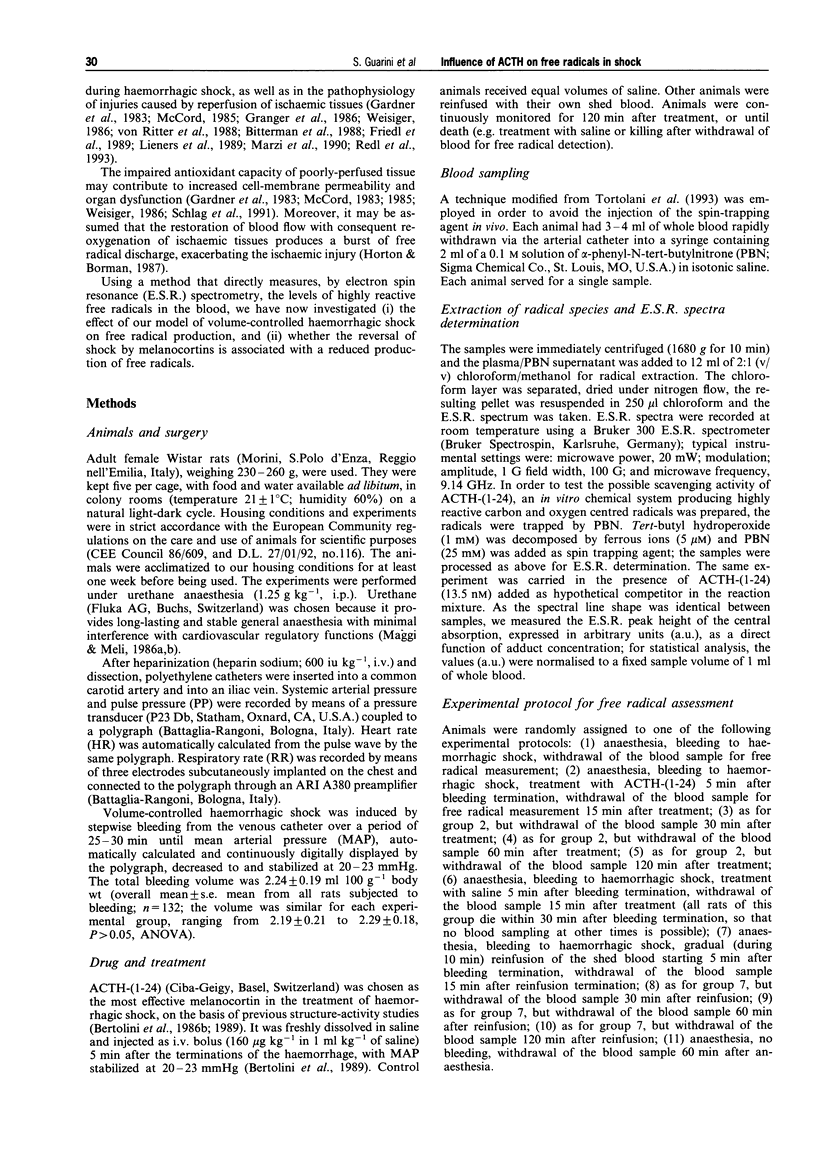

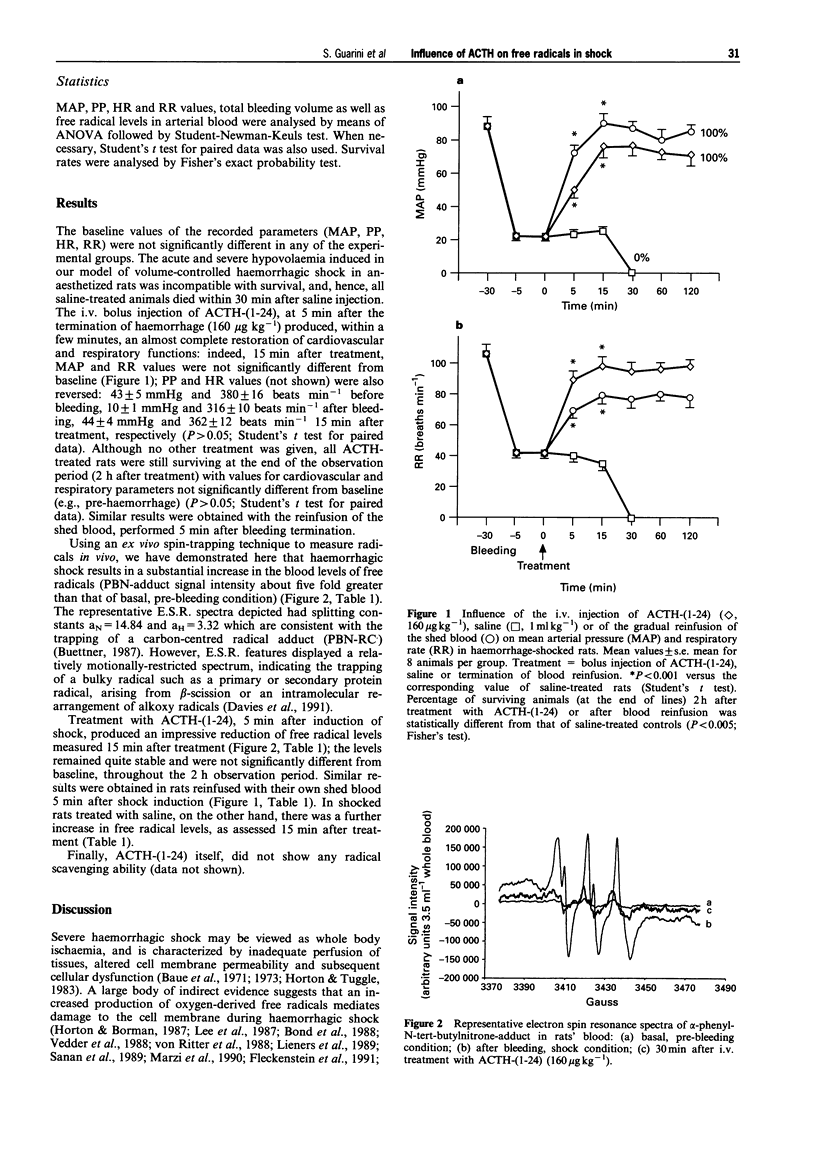

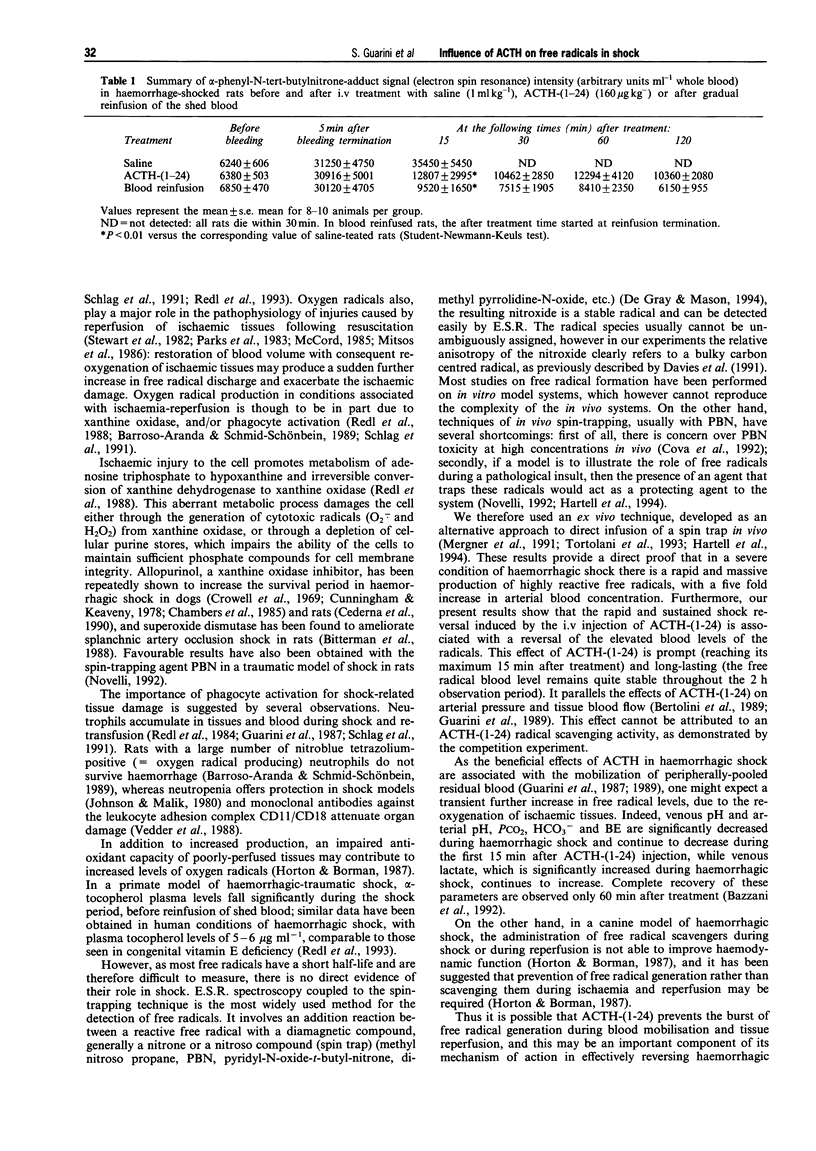

1. The influence of ACTH-(1-24) on the blood levels of highly reactive free radicals in haemorrhagic shock was studied in rats. 2. Volume-controlled haemorrhagic shock was produced in adult rats under general anaesthesia (urethane, 1.25 g kg-1 intraperitoneally) by stepwise bleeding until mean arterial pressure stabilized at 20-23 mmHg. Rats were intravenously (i.v.) treated with either ACTH-(1-24) (160 micrograms kg-1 in a volume of 1 ml kg-1) or equivolume saline. Free radicals were measured in arterial blood by electron spin resonance spectrometry using an ex vivo method that avoids injection of the spin-trapping agent (alpha-phenyl-N-tert-butylnitrone). 3. Blood levels of free radicals were 6490 +/- 273 [arbitrary units (a.u.) ml-1 whole blood, before starting bleeding, and 30762 +/- 2650 after bleeding termination (means +/- s.e. mean of the values obtained in all experimental groups). All rats treated with saline died within 30 min, their blood levels of free radicals being 35450 +/- 5450 a.u. ml-1 blood, 15 min after treatment. Treatment with ACTH-(1-24) produced a rapid and sustained restoration of arterial pressure, pulse pressure, heart rate and respiratory function, with 100% survival at the end of the observation period (2 h); this was associated with an impressive reduction in the blood levels of free radicals, that were 12807 +/- 2995, 10462 +/- 2850, 12294 +/- 4120, and 10360 +/- 2080 a.u. ml-1 blood, 15, 30, 60 and 120 min after ACTH-(1-24) administration, respectively. 4. These results provide a direct demonstration that (i) in haemorrhagic shock there is a rapid and massive production of highly reactive free radicals, and that (ii) the sustained restoration of cardiovascular and respiratory functions induced by the i.v. injection of ACTH-(1-24) is associated with a substantial reduction of free radical blood levels. It is suggested that ACTH-(1-24) prevents the burst of free radical generation during blood mobilisation and subsequent tissue reperfusion, and this may be an important component of its mechanism of action in effectively preventing death for haemorrhagic shock.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Barroso-Aranda J., Schmid-Schönbein G. W. Transformation of neutrophils as indicator of irreversibility in hemorrhagic shock. Am J Physiol. 1989 Sep;257(3 Pt 2):H846–H852. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.3.H846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baue A. E., Chaudry I. H., Wurth M. A., Sayeed M. M. Cellular alterations with shock and ischemia. Angiology. 1974 Jan;25(1):31–42. doi: 10.1177/000331977402500106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baue A. E., Wurth M. A., Chaudry I. H., Sayeed M. M. Impairment of cell membrane transport during shock and after treatment. Ann Surg. 1973 Oct;178(4):412–422. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197310000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzani C., Tagliavini S., Bertolini E., Bertolini A., Guarini S. Influence of ACTH-(1-24) on metabolic acidosis and hypoxemia induced by massive hemorrhage in rats. Resuscitation. 1992 Apr-May;23(2):113–120. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(92)90196-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolini A., Ferrari W., Guarini S. The adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-induced reversal of hemorrhagic shock. Resuscitation. 1989 Dec;18(2-3):253–267. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(89)90027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolini A., Guarini S., Ferrari W. Adrenal-independent, anti-shock effect of ACTH-(1-24) in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1986 Apr 2;122(3):387–388. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(86)90424-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolini A., Guarini S., Ferrari W., Noera G., Massini C., Di Tizio S. ACTH-(1-24) restores blood pressure in acute hypovolaemia and haemorrhagic shock in humans. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1987;32(5):537–538. doi: 10.1007/BF00637684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolini A., Guarini S., Ferrari W., Rompianesi E. Adrenocorticotropin reversal of experimental hemorrhagic shock is antagonized by morphine. Life Sci. 1986 Oct 6;39(14):1271–1280. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(86)90188-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolini A., Guarini S., Rompianesi E., Ferrari W. Alpha-MSH and other ACTH fragments improve cardiovascular function and survival in experimental hemorrhagic shock. Eur J Pharmacol. 1986 Oct 14;130(1-2):19–26. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(86)90179-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolini A. The opioid/anti-opioid balance in shock: a new target for therapy in resuscitation. Resuscitation. 1995 Aug;30(1):29–42. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(94)00863-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitterman H., Aoki N., Lefer A. M. Anti-shock effects of human superoxide dismutase in splanchnic artery occlusion (SAO) shock. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1988 Jul;188(3):265–271. doi: 10.3181/00379727-188-42734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond R. F., Haines G. A., Johnson G., 3rd The effect of allopurinol and catalase on cardiovascular hemodynamics during hemorrhagic shock. Circ Shock. 1988 Jul;25(3):139–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buettner G. R. Spin trapping: ESR parameters of spin adducts. Free Radic Biol Med. 1987;3(4):259–303. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(87)80033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cederna J., Bandlien K., Toledo-Pereyra L. H., Bergren C., MacKenzie G., Guttierez-Vega R. Effect of allopurinol and/or catalase on hemorrhagic shock and their potential application to multiple organ harvesting. Transplant Proc. 1990 Apr;22(2):444–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers D. E., Parks D. A., Patterson G., Roy R., McCord J. M., Yoshida S., Parmley L. F., Downey J. M. Xanthine oxidase as a source of free radical damage in myocardial ischemia. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1985 Feb;17(2):145–152. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(85)80017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cova D., De Angelis L., Monti E., Piccinini F. Subcellular distribution of two spin trapping agents in rat heart: possible explanation for their different protective effects against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Free Radic Res Commun. 1992;15(6):353–360. doi: 10.3109/10715769209049151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowell J. W., Jones C. E., Smith E. E. Effect of allopurinol on hemorrhagic shock. Am J Physiol. 1969 Apr;216(4):744–748. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1969.216.4.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham S. K., Keaveny T. V. Effect of a xanthine oxidase inhibitor on adenine nucleotide degradation in hemorrhagic shock. Eur Surg Res. 1978;10(5):305–313. doi: 10.1159/000128020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies M. J., Gilbert B. C., Haywood R. M. Radical-induced damage to proteins: e.s.r. spin-trapping studies. Free Radic Res Commun. 1991;15(2):111–127. doi: 10.3109/10715769109049131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleckenstein A. E., Smith S. L., Linseman K. L., Beuving L. J., Hall E. D. Comparison of the efficacy of mechanistically different antioxidants in the rat hemorrhagic shock model. Circ Shock. 1991 Dec;35(4):223–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedl H. P., Till G. O., Trentz O., Ward P. A. Roles of histamine, complement and xanthine oxidase in thermal injury of skin. Am J Pathol. 1989 Jul;135(1):203–217. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner T. J., Stewart J. R., Casale A. S., Downey J. M., Chambers D. E. Reduction of myocardial ischemic injury with oxygen-derived free radical scavengers. Surgery. 1983 Sep;94(3):423–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granger D. N., Höllwarth M. E., Parks D. A. Ischemia-reperfusion injury: role of oxygen-derived free radicals. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl. 1986;548:47–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarini S., Bazzani C., Bertolini A. Role of neuronal and vascular Ca(2+)-channels in the ACTH-induced reversal of haemorrhagic shock. Br J Pharmacol. 1993 Jul;109(3):645–650. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13621.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarini S., Ferrari W., Bertolini A. Anti-shock effect of ACTH-(1-24): influence of subtotal hepatectomy. Pharmacol Res Commun. 1988 May;20(5):395–403. doi: 10.1016/s0031-6989(88)80015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarini S., Ferrari W., Mottillo G., Bertolini A. Anti-shock effect of ACTH: haematological changes and influence of splenectomy. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1987 Oct;289(2):311–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarini S., Tagliavini S., Bazzani C., Benelli A., Bertolini A., Ferrari W. Effect of ACTH-(1-24) on the volume of circulating blood and on regional blood flow in rats bled to hypovolemic shock. Resuscitation. 1989 Dec;18(2-3):133–134. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(89)90006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarini S., Tagliavini S., Bazzani C., Ferrari W., Bertolini A. Early treatment with ACTH-(1-24) in a rat model of hemorrhagic shock prolongs survival and extends the time-limit for blood reinfusion to be effective. Crit Care Med. 1990 Aug;18(8):862–865. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199008000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartell M. G., Borzone G., Clanton T. L., Berliner L. J. Detection of free radicals in blood by electron spin resonance in a model of respiratory failure in the rat. Free Radic Biol Med. 1994 Nov;17(5):467–472. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)90173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton J. W., Borman K. R. Possible role of oxygen-derived, free radicals in cardiocirculatory shock. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1987 Oct;165(4):293–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A., Malik A. B. Effect of granulocytopenia on extravascular lung water content after microembolization. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980 Oct;122(4):561–566. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1980.122.4.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E. S., Greenburg A. G., Maffuid P. W., Melcher E. D., Velky T. S. Superoxide radicals and hemorrhagic shock: are intravascular radicals associated with mortality? J Surg Res. 1987 Jan;42(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(87)90056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieners C., Redl H., Molnar H., Fürst W., Hallström S., Schlag G. Lipidperoxidation in a canine model of hypovolemic-traumatic shock. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1989;308:345–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludbrook J., Ventura S. ACTH-(1-24) blocks the decompensatory phase of the haemodynamic response to acute hypovolaemia in conscious rabbits. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995 Mar 14;275(3):267–275. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggi C. A., Meli A. Suitability of urethane anesthesia for physiopharmacological investigations in various systems. Part 1: General considerations. Experientia. 1986 Feb 15;42(2):109–114. doi: 10.1007/BF01952426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggi C. A., Meli A. Suitability of urethane anesthesia for physiopharmacological investigations in various systems. Part 2: Cardiovascular system. Experientia. 1986 Mar 15;42(3):292–297. doi: 10.1007/BF01942510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord J. M. Oxygen-derived free radicals in postischemic tissue injury. N Engl J Med. 1985 Jan 17;312(3):159–163. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501173120305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord J. M. The superoxide free radical: its biochemistry and pathophysiology. Surgery. 1983 Sep;94(3):412–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mergner G. W., Weglicki W. B., Kramer J. H. Postischemic free radical production in the venous blood of the regionally ischemic swine heart. Effect of deferoxamine. Circulation. 1991 Nov;84(5):2079–2090. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.5.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsos S. E., Fantone J. C., Gallagher K. P., Walden K. M., Simpson P. J., Abrams G. D., Schork M. A., Lucchesi B. R. Canine myocardial reperfusion injury: protection by a free radical scavenger, N-2-mercaptopropionyl glycine. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1986 Sep-Oct;8(5):978–988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noera G., Angiello L., Biagi B., Pensa P. Haemorrhagic shock in cardiac surgery. Pharmacological treatment with ACTH (1-24). Resuscitation. 1991 Oct;22(2):123–127. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(91)90002-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noera G., Pensa P., Guelfi P., Biagi B., Curcio C., Bentini B. ACTH-(1-24) and hemorrhagic shock: preliminary clinical results. Resuscitation. 1989 Dec;18(2-3):145–147. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(89)90010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novelli G. P. Oxygen radicals in experimental shock: effects of spin-trapping nitrones in ameliorating shock pathophysiology. Crit Care Med. 1992 Apr;20(4):499–507. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199204000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks D. A., Bulkley G. B., Granger D. N. Role of oxygen-derived free radicals in digestive tract diseases. Surgery. 1983 Sep;94(3):415–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinelli G., Chesi G., Di Donato C., Reverzani A., Marani L. Preliminary data on the use of ACTH-(1-24) in human shock conditions. Resuscitation. 1989 Dec;18(2-3):149–150. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(89)90011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redl H., Gasser H., Schlag G., Marzi I. Involvement of oxygen radicals in shock related cell injury. Br Med Bull. 1993 Jul;49(3):556–565. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redl H., Schlag G., Hammerschmidt D. E. Quantitative assessment of leukostasis in experimental hypovolemic-traumatic shock. Acta Chir Scand. 1984;150(2):113–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanan S., Sharma G., Malhotra R., Sanan D. P., Jain P., Vadhera P. Protection by desferrioxamine against histopathological changes of the liver in the post-oligaemic phase of clinical haemorrhagic shock in dogs: correlation with improved survival rate and recovery. Free Radic Res Commun. 1989;6(1):29–38. doi: 10.3109/10715768909073425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlag G., Redl H., Hallström S. The cell in shock: the origin of multiple organ failure. Resuscitation. 1991 Apr;21(2-3):137–180. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(91)90044-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortolani A. J., Powell S. R., Misík V., Weglicki W. B., Pogo G. J., Kramer J. H. Detection of alkoxyl and carbon-centered free radicals in coronary sinus blood from patients undergoing elective cardioplegia. Free Radic Biol Med. 1993 Apr;14(4):421–426. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(93)90091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vedder N. B., Winn R. K., Rice C. L., Chi E. Y., Arfors K. E., Harlan J. M. A monoclonal antibody to the adherence-promoting leukocyte glycoprotein, CD18, reduces organ injury and improves survival from hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation in rabbits. J Clin Invest. 1988 Mar;81(3):939–944. doi: 10.1172/JCI113407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisiger R. A. Oxygen radicals and ischemic tissue injury. Gastroenterology. 1986 Feb;90(2):494–496. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(86)90955-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Ritter C., Hinder R. A., Oosthuizen M. M., Svensson L. G., Hunter S. J., Lambrecht H. Gastric mucosal lesions induced by hemorrhagic shock in baboons. Role of oxygen-derived free radicals. Dig Dis Sci. 1988 Jul;33(7):857–864. doi: 10.1007/BF01550976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]