Abstract

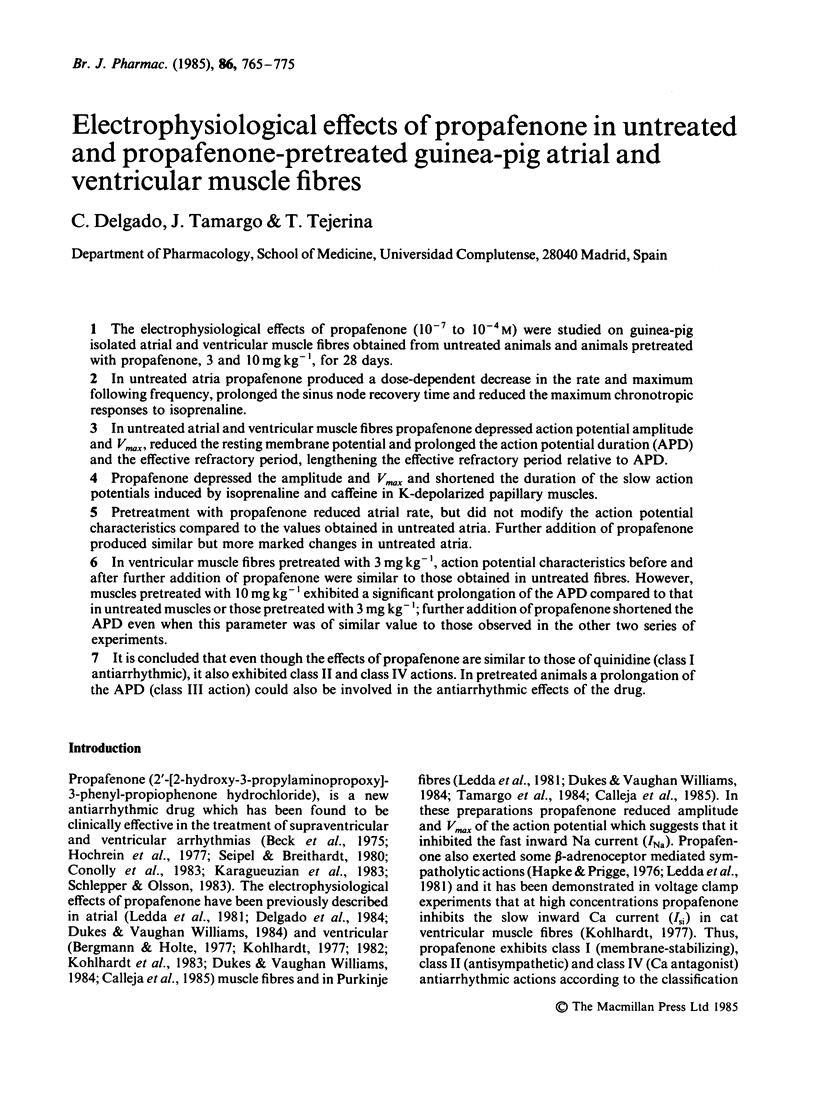

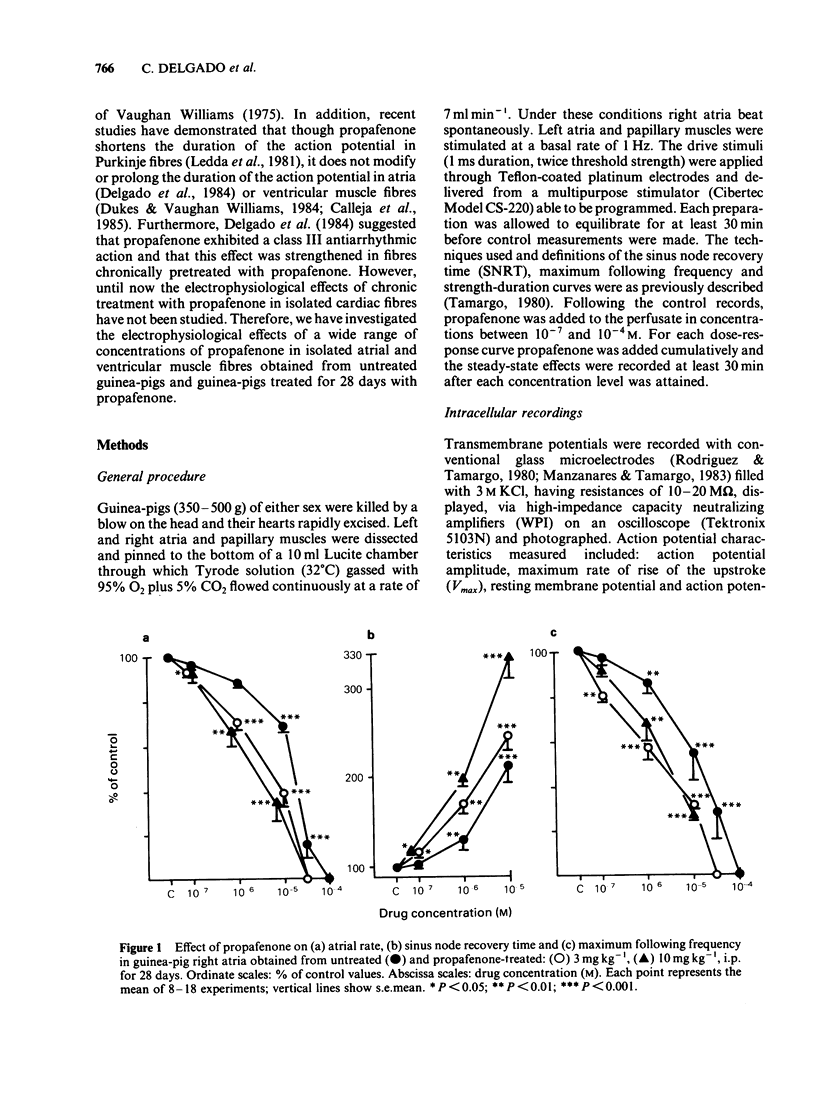

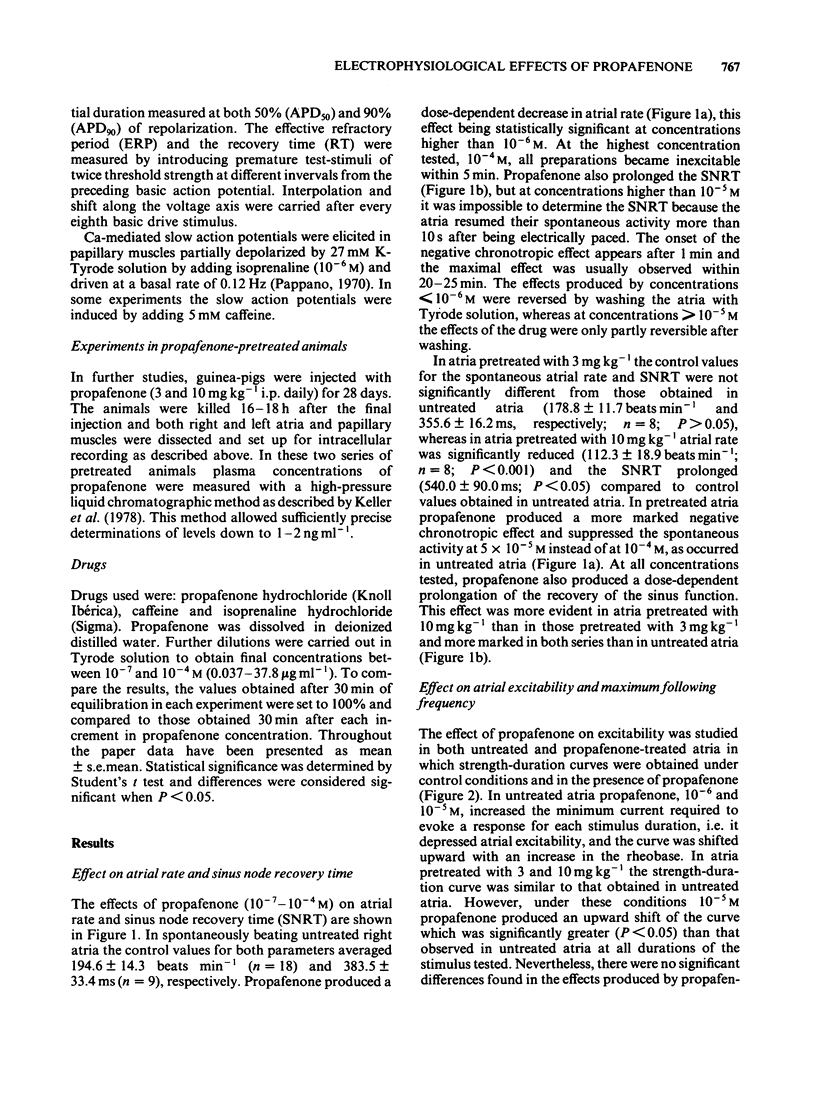

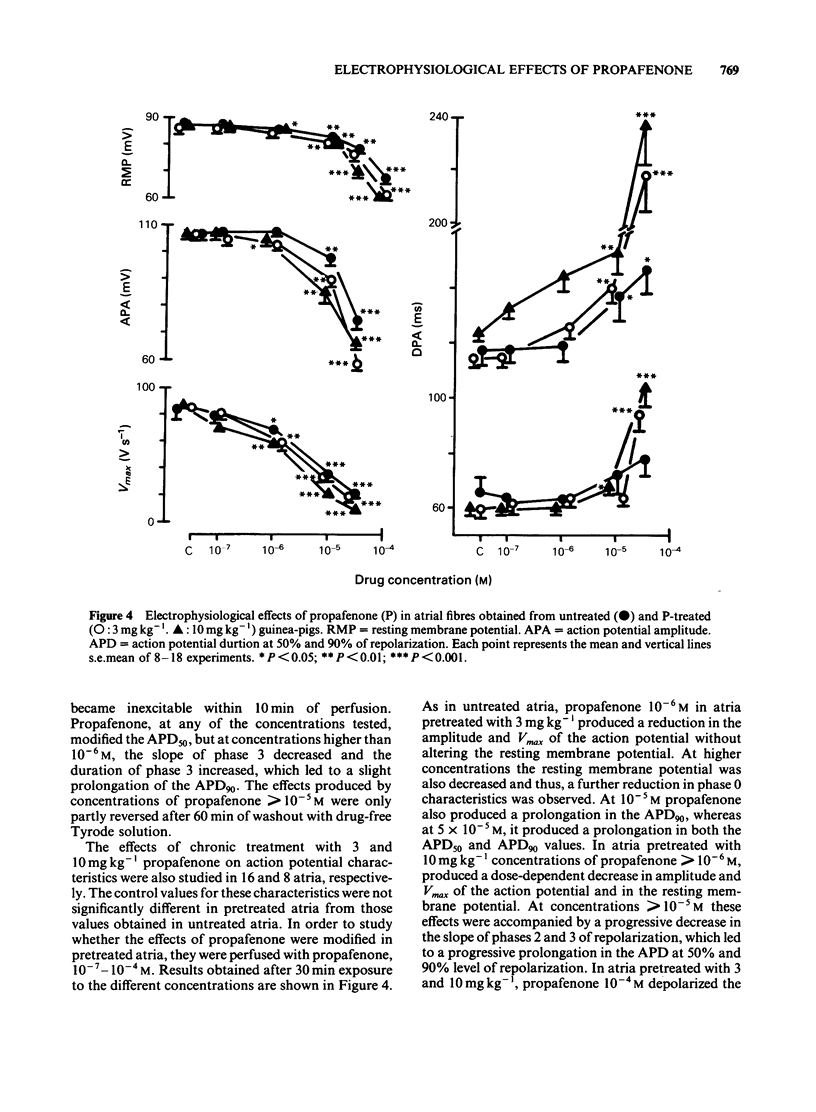

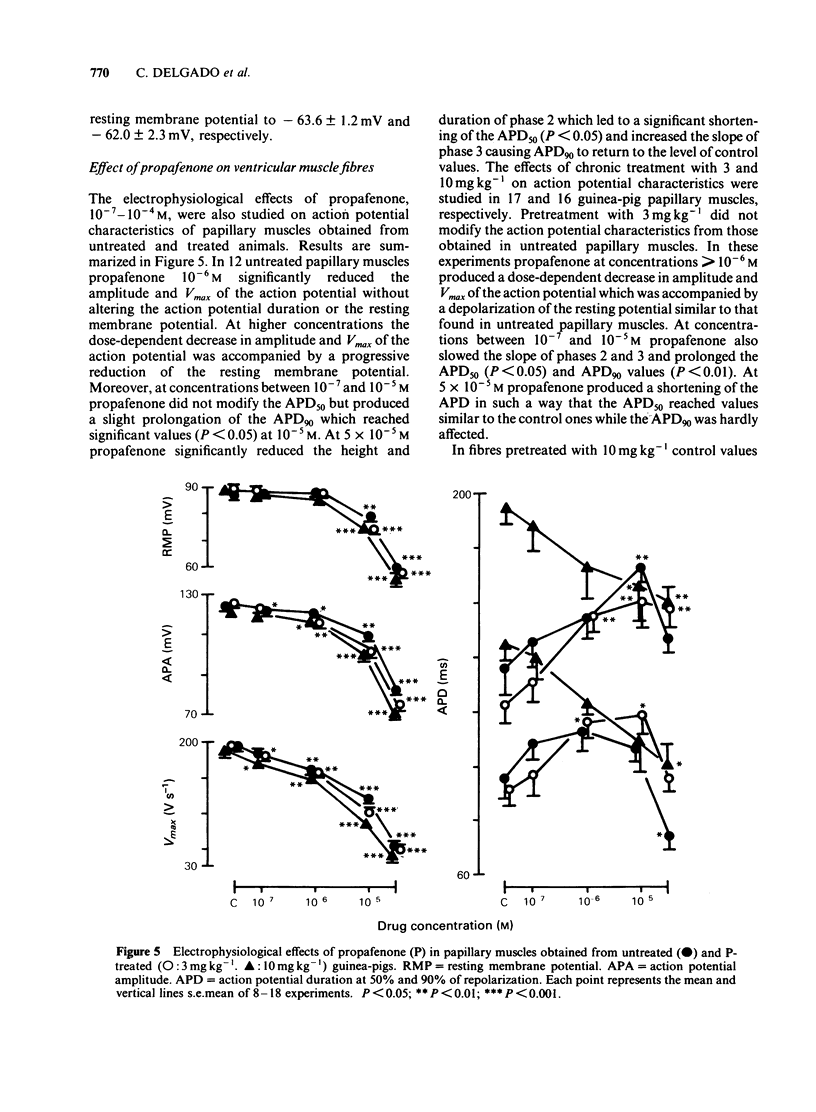

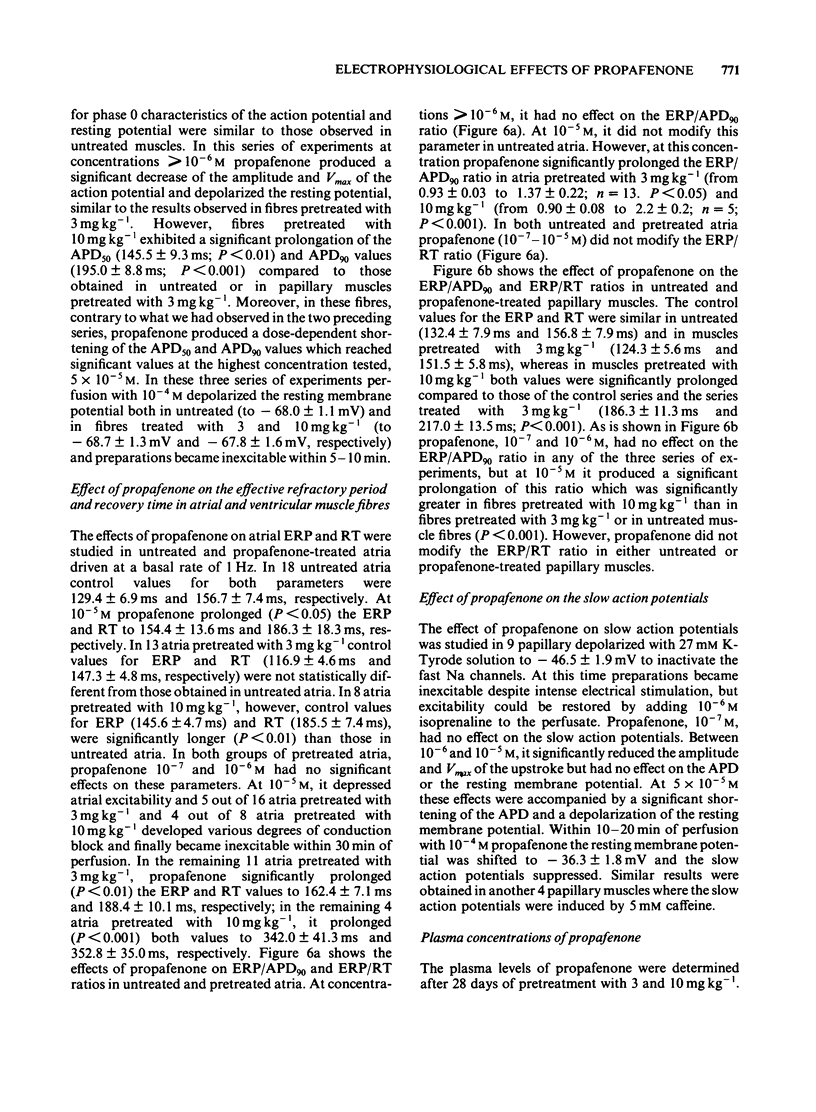

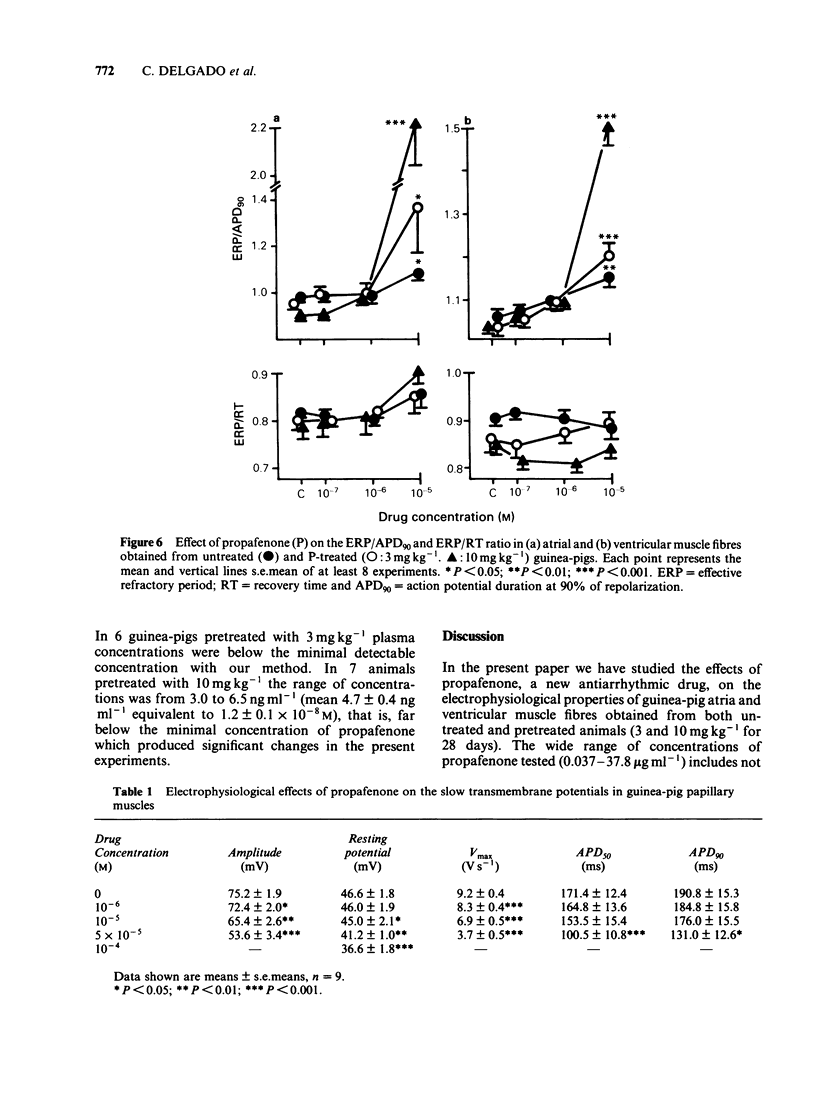

The electrophysiological effects of propafenone (10(-7) to 10(-4) M) were studied on guinea-pig isolated atrial and ventricular muscle fibres obtained from untreated animals and animals pretreated with propafenone, 3 and 10 mg kg-1, for 28 days. In untreated atria propafenone produced a dose-dependent decrease in the rate and maximum following frequency, prolonged the sinus node recovery time and reduced the maximum chronotropic responses to isoprenaline. In untreated atrial and ventricular muscle fibres propafenone depressed action potential amplitude and Vmax, reduced the resting membrane potential and prolonged the action potential duration (APD) and the effective refractory period, lengthening the effective refractory period relative to APD. Propafenone depressed the amplitude and Vmax and shortened the duration of the slow action potentials induced by isoprenaline and caffeine in K-depolarized papillary muscles. Pretreatment with propafenone reduced atrial rate, but did not modify the action potential characteristics compared to the values obtained in untreated atria. Further addition of propafenone produced similar but more marked changes in untreated atria. In ventricular muscle fibres pretreated with 3 mg kg-1, action potential characteristics before and after further addition of propafenone were similar to those obtained in untreated fibres. However, muscles pretreated with 10 mg kg-1 exhibited a significant prolongation of the APD compared to that in untreated muscles or those pretreated with 3 mg kg-1; further addition of propafenone shortened the APD even when this parameter was of similar value to those observed in the other two series of experiments. It is concluded that even though the effects of propafenone are similar to those of quinidine (class I antiarrhythmic), it also exhibited class II and class IV actions. In pretreated animals a prolongation of the APD (class III action) could also be involved in the antiarrhythmic effects of the drug.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Beck O. A., Witt E., Hochrein H. Der Einfluss des Antiarrhythmikums Propafenon auf die intrakardiale Erregungsleitung. Klinische Untersuchungen mit Hilfe de His-Bündel-Elektrographie. Z Kardiol. 1975 Feb;64(2):179–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. M., Gettes L. S., Katzung B. G. Effect of lidocaine and quinidine on steady-state characteristics and recovery kinetics of (dV/dt)max in guinea pig ventricular myocardium. Circ Res. 1975 Jul;37(1):20–29. doi: 10.1161/01.res.37.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly S. J., Kates R. E., Lebsack C. S., Harrison D. C., Winkle R. A. Clinical pharmacology of propafenone. Circulation. 1983 Sep;68(3):589–596. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.68.3.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dukes I. D., Vaughan Williams E. M. The multiple modes of action of propafenone. Eur Heart J. 1984 Feb;5(2):115–125. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a061621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hapke H. J., Prigge E. Zur Pharmakologie von 2'-[2-Hydroxy-3-(propylamino)-propoxy]-3-phenylpropiophenon (Propafenon, SA 79)-hydrochlorid. Arzneimittelforschung. 1976;26(10):1849–1857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karagueuzian H. S., Fujimoto T., Katoh T., Peter T., McCullen A., Mandel W. J. Suppression of ventricular arrhythmias by propafenone, a new antiarrhythmic agent, during acute myocardial infarction in the conscious dog. A comparative study with lidocaine. Circulation. 1982 Dec;66(6):1190–1198. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.66.6.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller K., Meyer-Estorf G., Beck O. A., Hochrein H. Correlation between serum concentration and pharmacological effect on atrioventricular conduction time of the antiarrhythmic drug propafenone. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1978 Mar 17;13(1):17–20. doi: 10.1007/BF00606676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlhardt M. A quantitative analysis of the Na+-dependence of Vmax of the fast action potential in mammalian ventricular myocardium. Saturation characteristics and the modulation of a drug-induced INa blockade by [Na+]o. Pflugers Arch. 1982 Feb;392(4):379–387. doi: 10.1007/BF00581635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlhardt M., Seifert C., Hondeghem L. M. Tonic and phasic INa blockade by antiarrhythmics. Different properties of drug binding to fast sodium channels as judged from Vmax studies with propafenone and derivatives in mammalian ventricular myocardium. Pflugers Arch. 1983 Mar 1;396(3):199–209. doi: 10.1007/BF00587856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlhardt M., Seifert C. Inhibition of Vmax of the action potential by propafenone and its voltage-, time- and pH-dependence in mammalian ventricular myocardium. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1980;315(1):55–62. doi: 10.1007/BF00504230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledda F., Mantelli L., Manzini S., Amerini S., Mugelli A. Electrophysiological and antiarrhythmic properties of propafenon in isolated cardiac preparations. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1981 Nov-Dec;3(6):1162–1173. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198111000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzanares J., Tamargo J. Electrophysiological effects of imipramine in nontreated and in imipramine-pretreated rat atrial fibres. Br J Pharmacol. 1983 May;79(1):167–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1983.tb10509.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappano A. J. Calcium-dependent action potentials produced by catecholamines in guinea pig atrial muscle fibers depolarized by potassium. Circ Res. 1970 Sep;27(3):379–390. doi: 10.1161/01.res.27.3.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine A. E., Vaughan Williams E. M. Adaptation to prolonged beta-blockade of rabbit atrial, purkinje, and ventricular potentials, and of papillary muscle contraction. Time-course of development of and recovery from adaptation. Circ Res. 1981 Jun;48(6 Pt 1):804–812. doi: 10.1161/01.res.48.6.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez S., Tamargo J. Electrophysiological effects of imipramine on bovine ventricular muscle and Purkinje fibres. Br J Pharmacol. 1980 Sep;70(1):15–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1980.tb10899.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider J. A., Sperelakis N. Slow Ca2+ and Na+ responses induced by isoproterenol and methylxanthines in isolated perfused guinea pig hearts exposed to elevated K+. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1975 Apr;7(4):249–273. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(75)90084-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seipel L., Breithardt G. Propafenone--a new antiarrhythmic drug. Eur Heart J. 1980 Aug;1(4):309–313. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a061135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiu M. F. Mitral valve disease. Eur Heart J. 1984 Mar;5 (Suppl A):131–134. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/5.suppl_a.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer D. H., Lazzara R., Hoffman B. F. Interrelationship between automaticity and conduction in Purkinje fibers. Circ Res. 1967 Oct;21(4):537–558. doi: 10.1161/01.res.21.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh B. N., Vaughan Williams E. M. The effect of amiodarone, a new anti-anginal drug, on cardiac muscle. Br J Pharmacol. 1970 Aug;39(4):657–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1970.tb09891.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamargo J. Electrophysiological effects of bunaphtine on isolated rat atria. Eur J Pharmacol. 1980 Mar 7;62(1):81–88. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(80)90483-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tritthart H., Volkmann R., Weiss R., Fleckenstein A. Calcium-mediated action potentials in mammalian myocardium. Alteration of membrane response as induced by changes of Cae or by promoters and inhibitors of transmembrane Ca inflow. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1973;280(3):239–252. doi: 10.1007/BF00501349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan Williams E. M. Classification of antidysrhythmic drugs. Pharmacol Ther B. 1975;1(1):115–138. doi: 10.1016/0306-039x(75)90019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEIDMANN S. The effect of the cardiac membrane potential on the rapid availability of the sodium-carrying system. J Physiol. 1955 Jan 28;127(1):213–224. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1955.sp005250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams E. M., Hassan M. O., Floras J. S., Sleight P., Jones J. V. Adaptation of hypertensives to treatment with cardioselective and non-selective beta-blockers. Absence of correlation between bradycardia and blood pressure control, and reduction in slope of the QT/RR relation. Br Heart J. 1980 Nov;44(5):473–487. doi: 10.1136/hrt.44.5.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams E. M., Raine A. E., Cabrera A. A., Whyte J. M. The effects of prolonged beta-adrenoceptor blockade on heart weight and cardiac intracellular potentials in rabbits. Cardiovasc Res. 1975 Sep;9(5):579–592. doi: 10.1093/cvr/9.5.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]