Abstract

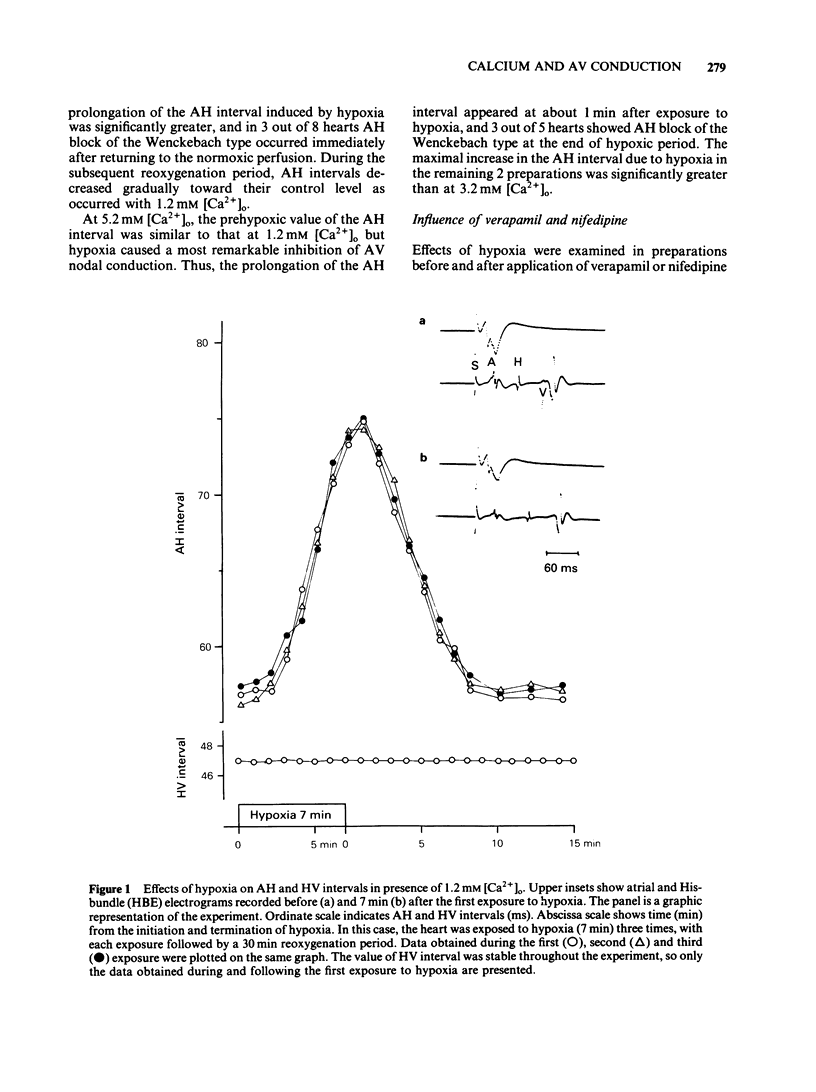

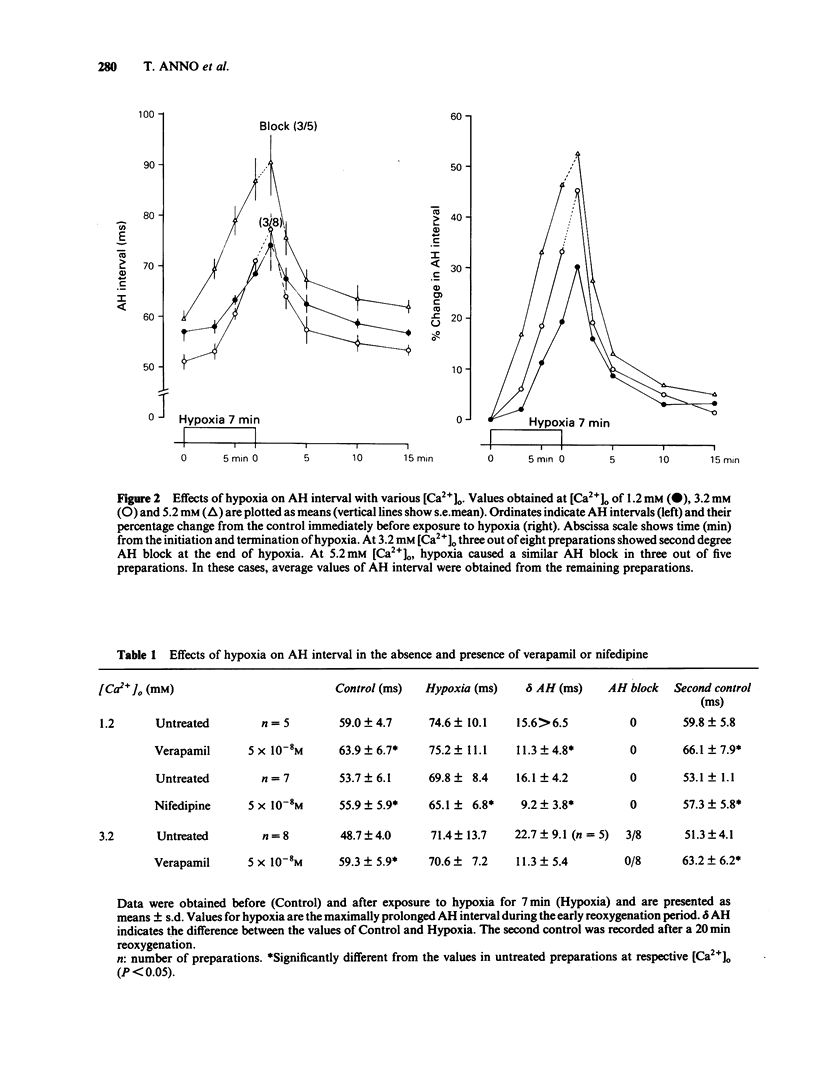

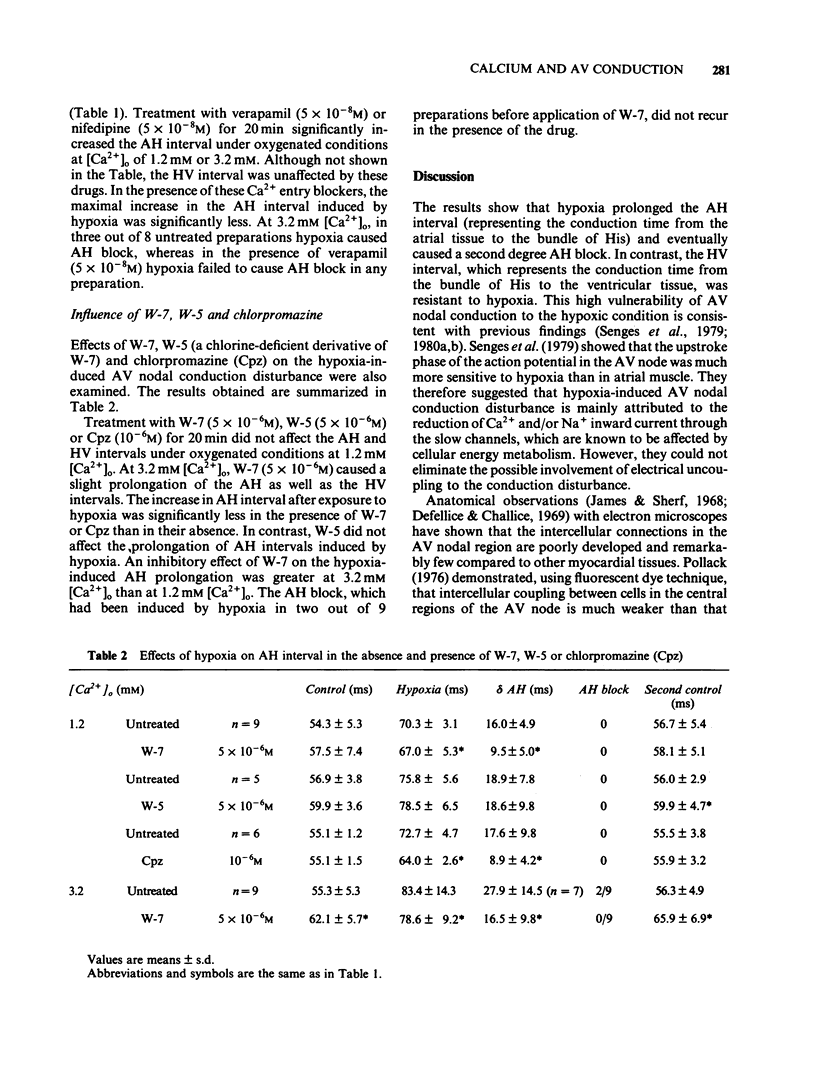

Effects of hypoxia on atrioventricular conduction were investigated in the Langendorff-perfused isolated heart of the rabbit with various extracellular calcium concentrations ([Ca2+]) as well as in the presence of verapamil, nifedipine, N-(6-aminohexyl)-5-chloro-1-naphthalenesulphonamide (W-7) and chlorpromazine. The prolongation of the atrio-His (AH) interval by hypoxia for 7 min was greater with increasing [Ca2+]o ranging from 1.2 to 5.2 mM. At [Ca2+]o of over 3.2 mM under hypoxic conditions, AH block of the Wenckebach type was observed in some cases. Verapamil (5 X 10(-8) M) and nifedipine (5 X 10(-8) M) caused a significant prolongation of AH intervals before hypoxia. However, the intensity of AH prolongation due to hypoxia was significantly attenuated in the presence of the calcium entry blocker, and AH block was not induced even at 3.2 mM [Ca2+]o. W-7 (5 X 10(-6) M) and chlorpromazine (10(-6) M) did not affect the AH intervals before hypoxia. The hypoxia-induced prolongation of the AH interval or AH block was prevented in the presence of these drugs. W-5, a chlorine-deficient derivative of W-7, showed no protection against hypoxia-induced AV nodal conduction disturbances. These findings suggest that hypoxia-induced AV nodal conduction disturbance is explained, at least in part, by the electrical uncoupling of nodal cells, probably due to the calcium overload. This conduction disturbance is protected by calcium entry blockers or by calmodulin inhibitors, but the mode of protective action is not the same for these different categories of drugs.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bkaily G., Sperelakis N., Eldefrawi M. Effects of the calmodulin inhibitor, trifluoperazine, on membrane potentials and slow action potentials of cultured heart cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 1984 Oct 1;105(1-2):23–31. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(84)90645-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonke F. I. Passive electrical properties of atrial fibers of the rabbit heart. Pflugers Arch. 1973 Mar 5;339(1):1–15. doi: 10.1007/BF00586977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung W. Y. Calmodulin plays a pivotal role in cellular regulation. Science. 1980 Jan 4;207(4426):19–27. doi: 10.1126/science.6243188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Mello W. C. Intercellular communication in cardiac muscle. Circ Res. 1982 Jul;51(1):1–9. doi: 10.1161/01.res.51.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Mello W. C. Passive electrical properties of the atrio-ventricular node. Pflugers Arch. 1977 Oct 19;371(1-2):135–139. doi: 10.1007/BF00580781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFelice L. J., Challice C. E. Anatomical and ultrastructural study of the electrophysiological atrioventricular node of the rabbit. Circ Res. 1969 Mar;24(3):457–474. doi: 10.1161/01.res.24.3.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleckenstein A., Janke J., Döring H. J., Leder O. Myocardial fiber necrosis due to intracellular Ca overload-a new principle in cardiac pathophysiology. Recent Adv Stud Cardiac Struct Metab. 1974;4:563–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franson R. C., Pang D. C., Towle D. W., Weglicki W. B. Phospholipase A activity of highly enriched preparations of cardiac sarcolemma from hamster and dog. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1978 Oct;10(10):921–930. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(78)90338-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOFFMAN B. F. Physiology of atrioventricular transmission. Circulation. 1961 Aug;24:506–517. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.24.2.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidaka H., Asano M., Tanaka T. Activity-structure relationship of calmodulin antagonists, Naphthalenesulfonamide derivatives. Mol Pharmacol. 1981 Nov;20(3):571–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidaka H., Yamaki T., Totsuka T., Asano M. Selective inhibitors of Ca2+-binding modulator of phosphodiesterase produce vascular relaxation and inhibit actin-myosin interaction. Mol Pharmacol. 1979 Jan;15(1):49–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda N., Toyama J., Shimizu T., Kodama I., Yamada K. The role of electrical uncoupling in the genesis of atrioventricular conduction disturbance. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1980 Aug;12(8):809–826. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(80)90082-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James T. N., Sherf L. Ultrastructure of the human atrioventricular node. Circulation. 1968 Jun;37(6):1049–1070. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.37.6.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin R. M., Weiss B. Mechanism by which psychotropic drugs inhibit adenosine cyclic 3',5'-monophosphate phosphodiesterase of brain. Mol Pharmacol. 1976 Jul;12(4):581–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein W. R. Junctional intercellular communication: the cell-to-cell membrane channel. Physiol Rev. 1981 Oct;61(4):829–913. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1981.61.4.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Means A. R., Tash J. S., Chafouleas J. G. Physiological implications of the presence, distribution, and regulation of calmodulin in eukaryotic cells. Physiol Rev. 1982 Jan;62(1):1–39. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1982.62.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayler W. G., Poole-Wilson P. A., Williams A. Hypoxia and calcium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1979 Jul;11(7):683–706. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(79)90381-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedergerke R., Orkand R. K. The dual effect of calcium on the action potential of the frog's heart. J Physiol. 1966 May;184(2):291–311. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1966.sp007916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peracchia C., Bernardini G., Peracchia L. L. Is calmodulin involved in the regulation of gap junction permeability? Pflugers Arch. 1983 Oct;399(2):152–154. doi: 10.1007/BF00663912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack G. H. Intercellular coupling in the atrioventricular node and other tissues of the rabbit heart. J Physiol. 1976 Feb;255(1):275–298. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter H. The dependence of slow inward current in Purkinje fibres on the extracellular calcium-concentration. J Physiol. 1967 Sep;192(2):479–492. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1967.sp008310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer S. W., Burton K. P., Jones H. P., Oei H. H. Phenothiazine protection in calcium overload-induced heart failure: a possible role for calmodulin. Am J Physiol. 1983 Mar;244(3):H328–H334. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1983.244.3.H328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senges J., Brachmann J., Pelzer D., Krämer B., Kübler W. Combined effects of glucose and hypoxia on cardiac automaticity and conduction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1980 Mar;12(3):311–323. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(80)90043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senges J., Hennig E., Brachmann J., Pelzer D., Mizutani T., Kübler W. Effects of orciprenaline on the sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodes in presence of hypoxia. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1980 Jan;12(1):135–147. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(80)90115-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senges J., Mizutani T., Pelzer D., Brachmann J., Sonnhof U., Kübler W. Effect of hypoxia on the sinoatrial node, atrium, and atrioventricular node in the rabbit heart. Circ Res. 1979 Jun;44(6):856–863. doi: 10.1161/01.res.44.6.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata S., Carrier O., Jr Antagonizing action of chlorpromazine, dibenamine, and phenoxybenzamine on potassium-induced contraction. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1967 Jul;45(4):587–596. doi: 10.1139/y67-071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEIDMANN S. The electrical constants of Purkinje fibres. J Physiol. 1952 Nov;118(3):348–360. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh M. P., Le Peuch C. J., Vallet B., Cavadore J. C., Demaille J. G. Cardiac calmodulin and its role in the regulation of metabolism and contraction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1980 Oct;12(10):1091–1101. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(80)90034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe Y., Dreifus L. S. Electrophysiologic effects of digitalis on A-V transmission. Am J Physiol. 1966 Dec;211(6):1461–1466. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1966.211.6.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe Y., Dreifus L. S. Inhomogeneous conduction in the A-V node. A model for re-entry. Am Heart J. 1965 Oct;70(4):505–514. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(65)90364-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidmann S. Electrical constants of trabecular muscle from mammalian heart. J Physiol. 1970 Nov;210(4):1041–1054. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtczak J. Contractures and increase in internal longitudianl resistance of cow ventricular muscle induced by hypoxia. Circ Res. 1979 Jan;44(1):88–95. doi: 10.1161/01.res.44.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]