Abstract and Introduction

Abstract

Background and Aims

Bezoars occur most commonly in patients with impaired gastrointestinal motility or a history of gastric surgery. Noonan syndrome is associated with gastrointestinal dysfunction and feeding difficulties in children. We report the case of a 64-year-old man with Noonan syndrome who was admitted to the hospital with a small bowel obstruction. An emergency laparotomy was performed and the patient was found to have a phytobezoar of the ileum that had caused edema of the intestinal wall resulting in the obstruction.

Methods/Results

A review of the literature was performed with PubMed using the keywords “Noonan syndrome,” “bezoars,” and “phytobezoar.” Although problems with gastrointestinal motility in Noonan syndrome appear to improve with age, it is conceivable that in this case, abnormal gastrointestinal motility may have predisposed the patient to this condition.

Conclusion

Bezoars are an uncommon but notable cause of small bowel obstruction. This is the first case of a bezoar in a patient with Noonan syndrome reported in the English literature.

Introduction

Noonan syndrome is a multiple congenital anomaly disorder with an incidence estimated at 1 per 1000 to 1 per 2500 live births.[1] It was first described by Noonan and Ehmke in 1963[2] in a series of patients with unusual facies, multiple malformations, and congenital heart disease. The other primary associated features of Noonan syndrome include developmental delay, mild mental retardation, short stature, undescended testes, hypotonia, seizure disorders, bleeding diatheses, and congenital cardiac defects. Because of a number of shared clinical features, Noonan syndrome was previously thought to be a form of Turner syndrome, a chromosomal condition that exclusively affects females. However, because individuals with Noonan syndrome have normal karyotypes, it is now recognized to be a separate condition. Although the pathophysiology of Noonan syndrome is not well understood, it is thought to be transmitted in an autosomal dominant fashion with variable expression. Many cases, however, appear to be sporadic. Linkage analysis suggests that the gene for Noonan syndrome may exist on chromosome 12q.[3]

For centuries, different types of bezoars (accumulations of foreign matter) have been known to occur in the stomach and intestines of animals and humans. Phytobezoars are the most common type, consisting of nondigestible food material such as cellulose, lignin, and fruit tannins. A sticky coagulum is formed on contact with gastric acids due to polymerization of monomeric fruit tannins (especially those occurring in persimmons and citrus fruits).[4] Trichobezoars are classically described as consisting mostly of hair, and are often noted in psychologically impaired adults and children who also have trichotillomania (a compulsion to pull out one's hair).[4] Rapunzel's syndrome, due to compulsive hair-chewing, results in the formation of a long-tailed trichobezoar, a documented variant of trichobezoars.[4] Lactobezoars are most often found in low-birth-weight neonates fed a highly concentrated formula during the first few weeks of life. Milk elements such as casein congeal due to poor neonatal gastrointestinal motility, concentrated formula regimens, and dehydration. Various medications such as nifedipine, cholestyramine, kayexalate, antacids, and objects such as nuts, glue, cement, and shellac have been reported to cause bezoars. All types of bezoars are commonly associated with impaired gastrointestinal motility or previous gastric surgery.[4]

We report a case of a phytobezoar in a patient with Noonan syndrome. A MEDLINE search of articles published between 1965 and 2006 using the keywords “Noonan syndrome” and “bezoar” or “phytobezoar” revealed no previously reported cases.

Case Report

A 64-year-old man with Noonan syndrome presented to the emergency department with a 1-day history of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, decreased oral intake, and obstipation. His abdomen was distended but he was passing flatus. His past medical history was significant for Noonan syndrome, in addition to congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, gout, asthma, hypogonadism, chronic renal insufficiency, and 2 surgeries for kidney stone removal.

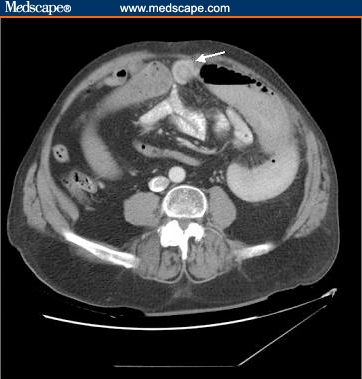

Abnormal laboratory values included a white blood cell count of 13.3 × 103 cells/mcL and a creatinine level of 1.5 mg/dL. A radiograph of the abdomen revealed 2 significantly dilated small bowel loops with fold thickening in the left side of the abdomen (Figure 1). A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen demonstrated many dilated loops of fluid-filled distal jejunum with decompressed proximal jejunum and distal ileum (Figure 2). Inferior to the umbilicus near the midline was a 1.5-cm target sign of the small bowel with an outer enhancing wall, a hypodense inner ring, and a central hyperdensity. Because this abnormality was seen at the transition point and was likely located in the ileum, we thought it might represent a very short-segment intussusception or potentially a gallstone ileus. A streaky air pattern in the dilated loops was suspicious for pneumatosis.

Figure 1.

Abdominal plain film radiograph. Note the multiple dilated loops of small bowel suggestive of a small bowel obstruction.

Figure 2.

Abdominal CT scan. The arrow points to the phytobezoar in the small bowel.

An emergency exploratory laparotomy was performed and we found that the patient had mild adhesive disease requiring a lysis of adhesions. A segment of hyperemic thickened ileum was also noted to have a large mobile mass within it. The wall of the small bowel was incised to extract the phytobezoar and closed primarily. The patient's postoperative course was characterized by mild congestive heart failure, but there were no other complications. When he was discharged from the hospital he was able to tolerate a regular diet without difficulty.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, there have been no previously published reports in the medical literature of phytobezoars in patients with Noonan syndrome. This case represents what may be an interesting association between bezoars and gastrointestinal dysmotility related to Noonan syndrome. A study of 25 children with Noonan syndrome ranging in age from 2 months to 12 years revealed that 16 had gastrointestinal symptoms such as reflux and failure to thrive.[5] However, difficulties with feeding often went unrecognized, and the etiology of the problem was uncertain. In this same group of patients, 7 of 25 had foregut dysmotility and gastroesophageal reflux documented by electrogastrography and antroduodenal manometry. Four of the 7 children with foregut dysmotility had abnormal gastric and small bowel myoelectrical activity that was characterized as disorganized and weak. The study authors speculated that the dysmotility and feeding difficulties were due to a delay in the development of the enteric nervous system in children with Noonan syndrome. Although many of these children improved with age, persistent dysmotility could put them at risk for the development of bezoars, such as the one seen in our patient.

The main risk factors for bezoars include gastric surgery and gastrointestinal dysmotility. Delayed gastric emptying and abnormal gastric motility patterns were prominent in one series of patients with bezoars, suggesting that these events were the underlying factors in their development.[6] However, another series of patients with bezoars who had undergone vagotomy or pyloroplasty did not demonstrate uniformly delayed gastric emptying as assessed by technetium-99m- labeled studies.[7] A study involving 117 patients with gastrointestinal bezoars revealed that 87% occurred in the small bowel and 30% in the stomach.[8] Furthermore, 70% of patients had previous surgery for peptic ulcer disease, and 80% of these patients had a bilateral truncal vagotomy with pyloroplasty. Of the 87 patients presenting with intestinal bezoars, excessive intake of vegetable fiber occurred in 40%, and 24% had alterations of mastication and dentition. A review of several case series noted that bezoars were prevalent among patients with mental retardation; one study estimated that up to 10% of emergency laparotomies in mentally retarded patients may be performed because of bezoars.[9] Another recognized risk factor for bezoars is diabetic gastroparesis.[6]

Patients with bezoars often present with signs and symptoms of bowel obstruction, such as colicky abdominal pain, vomiting, and constipation or obstipation. Plain abdominal films can reveal dilated small bowel loops, and barium enema studies can show an intraluminal filling defect of variable size that will not appear fixed to bowel wall.[4] Abdominal CT scan is the best diagnostic modality for detecting bezoars. The pathognomonic appearance of bezoars is that of a well-defined ovoid intraluminal mass with mottled gas pattern at the site of obstruction.[10] Radiographic evidence of a small bowel obstruction with dilated fluid and air-filled loops proximal to the site of obstruction and distal collapsed small bowel may also be present. Definitive treatment consists of exploratory laparotomy with milking of contents to the cecum, or enterotomy. Medical treatment is usually inadequate.

There are scant recent data on the prevalence of bezoars causing mechanical small bowel obstruction, although one series from Hong Kong reported that over a 10-year period, 19 of 1020 (2%) small bowel obstructions at their hospital were related to bezoars.[11] However, a review from the Mayo Clinic reported that only 3 of 314 (0.9%) small bowel obstructions were due to bezoars.[12] Thus, geographical variation may exist, although the true incidence is still unknown.

Concluding Remarks

Bezoars are an uncommon but notable cause of small bowel obstruction and are associated with gastrointestinal dysmotility. A study[5] of feeding difficulties and dysmotility in children with Noonan syndrome suggests the possibility that enteric nervous system developmental delay may predispose these patients to gastric dysmotility that does not often improve. This subset of patients may be at risk of developing bezoars.

Footnotes

Readers are encouraged to respond to the author at varmam@surgery.ucsf.edu or to Paul Blumenthal, MD, Deputy Editor of MedGenMed, for the editor's eyes only or for possible publication via email: pblumen@stanford.edu

Contributor Information

Asaf Bitton, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Jennifer N. Keagle, Department of Surgery, University of Washington, Seattle.

Madhulika G. Varma, Department of Surgery, University of California, San Francisco Authors' Email: varmam@surgery.ucsf.edu.

References

- 1.Noonan JA. Noonan syndrome revisited. J Pediatr. 1999;135:667–668. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70082-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noonan JA, Ehmke DA. Associated non-cardiac malformations in children with congenital heart disease. J Pediatr. 1963;63:468–470. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jamieson CR, van der Burgt I, Brady AF, et al. Mapping a gene for Noonan syndrome to the long arm of chromosome 12. Nat Genet. 1994;8:357–360. doi: 10.1038/ng1294-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrus CH, Ponsky JL. Bezoars: classification, pathophysiology and treatment. Am J Gasetoenterol. 1988;83:476–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah N, Rodriguez M, Louis DS, Lindley K, Milla PJ. Feeding difficulties and foregut dysmotility in Noonan's syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1999;81:28–31. doi: 10.1136/adc.81.1.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brady PG. Gastric phytobezoars consequent to delayed gastric emptying. Gastrointest Endosc. 1978;24:159–161. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(78)73494-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calabuig R, Navarro S, Carrio I, Artigas V, Mones J, Puig LaCalle J. Gastric emptying and bezoars. Am J Surg. 1989;157:287–290. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(89)90552-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robles R, Parrilla P, Escamilla C, et al. Gastrointestinal bezoars. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1000–1001. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Goor H, van Rooyen W. Bezoars: a special cause of ileal obstruction in mentally retarded patients. Neth J Surg. 1991;43:43–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yildirim T, Yildirim S, Barutcu O, Oguzkurt L, Noyan T. Small bowel obstruction due to phytobezoar: CT diagnosis. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:2659–2661. doi: 10.1007/s00330-001-1267-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lo CY, Lau PW. Small bowel phytobezoars: an uncommon cause of small bowel obstruction. Aust N Z J Surg. 1994;64:187–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1994.tb02175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mucha P. Small intestinal obstruction. Surg Clin North Am. 1987;67:597–620. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)44234-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]