Abstract

Immortalized central nervous system (CNS) cell lines are useful as in vitro models for innumerable purposes such as elucidating biochemical pathways, studies of effects of drugs, and ultimately, such cells may also be useful for neural transplantation. The SV40 large T (LT) oncoprotein, commonly used for immortalization, interacts with several cell cycle regulatory factors, including binding and inactivating p53 and retinoblastoma family cell-cycle regulators. In an attempt to define the minimal requirements of SV40 T antigen for immortalizing cells of CNS origin, we constructed T155c, encoding the N-terminal 155 amino acids of LT. The p53 binding region is known to reside in the C-terminal region of LT. An additional series of mutants was produced to further narrow the molecular targets for immortalization, and plasmid vectors were constructed for each. In a p53 temperature sensitive cell line model, T64-7B, expression of T155c and all constructs having mutations outside of the first 82 amino acids were capable of overriding cell-cycle block at the non-permissive growth temperature. Several cell lines were produced from fetal rat mesencephalic and cerebral cortical cultures using the T155c construct. The E107K construct contained a mutation in the Rb binding region, but was nonetheless capable of overcoming cell cycle block in T64-7B cell and immortalizing primary cultured cells. Cells immortalized with T155c were often highly dependent on the presence of bFGF for growth. Telomerase activity, telomere length, growth rates, and integrity of the p53 gene in cells immortalized with T155c did not change over 100 population doublings in culture, indicating that cells immortalized with T155c were generally stable during long periods of continuous culture.

Keywords: Immortalization, SV40 large T antigen, T155g, T155c, Plasmid, Telomerase, Telomere, Growth arrest, T64-7b, Cell line, Cell cycle, Oncogene

Introduction

Cell lines are very useful for many applications in cell biology, ranging from in vitro studies of viral propagation, developmental mechanisms, and drug effects, to potential clinical uses in transplantation. The concept of a cell line, a homogeneous cell population which can be indefinitely propagated in culture is, however, at odds with the normal development and function of an organism. Normal somatic cells exert lateral influences upon their neighbors to adopt different fates, and most cells in the mature organism are not continuously cycling. Thus, a homogeneous and perpetual population of identical somatic vertebrate cells does not normally exist in nature, except in the aberrant situation where mutations accumulate to produce tumors (e.g., Nowak et al., 2002). Thus, the creation of such cells requires either intervention or extraction from tumors.

Although tumor cell lines are valuable as in vitro models, for example, PC 12 cells, SH-SY5Y cells and many others, tumor cells have abnormalities, are usually unstable, and of course are not useful for transplantation. Numerous cell lines have been created by the introduction of oncogenes into primary cultures, and these cells are not tumorigenic, at least in some cases, in animals (e.g., Anton et al., 1994; Gray et al., 2000; Isono et al., 1992; Lundberg et al., 2002; Okoye et al., 1994; Whittemore and Onifer, 2000). It is widely recognized that tumor formation requires a number of mutational events, and some viral oncogenes apparently have the capacity to stimulate cell division without entirely converting the target cells into tumor cells. The concept of producing cell lines in the laboratory for the ultimate purpose of transplantation into human subjects is, therefore, an attempt to create cells which behave like tumor cells in some but not all respects.

In concept, a transplantable cell line would have the capacity for context-dependent unlimited growth, while under other contexts retaining the capacity for integration into an organism as a normal somatic cell. There are a number of strategies through which this might be achieved. One important element of this aim is to alter a cell sufficiently to allow for unlimited growth in vitro, while minimally interfering with normal cellular functions. Thus, the purpose of the present experiment is solely to focus on properties of the oncogene itself, to explore the minimum requirements for obtaining unlimited growth of cell lines derived from primary CNS rodent primary cultures.

One of the most commonly used immortalizing agents is the product of the simian virus 40 large tumor oncogene, SV40 large T (LT) (Bryan and Reddel, 1994; Cepko, 1989, 1992; Snyder, 1995). Cells immortalized with LT, either wild type or temperature sensitive variants, typically are not tumorigenic after transplantation into the brain (Giordano et al., 1996; Isono et al., 1992; Okoye et al., 1994, 1995; Renfranz et al., 1991), but are often phenotypically immature and genetically abnormal (Cepko, 1992); reviewed in Bryan and Reddel (1994).

In previous experiments, we identified T155, now called T155g, which is a 155-amino acid N-terminal fragment of SV40 large T antigen which also encodes the small t antigen. This agent was able to immortalize primary cells from rat mesencephalon (Truckenmiller et al., 1998), and cells produced by T155g were stable over long-term culture (Dillon-Carter et al., 2002; Truckenmiller et al., 2002). The entire p53 binding region, which may promote chromosomal rearrangements and prevent apoptosis, is deleted from T155g. In the present study, we further explored oncogene fragments derived from T155g to identify a minimal immortalizing agent for primary rodent CNS cultures.

Methods

Construction of T155c plasmid vector

To construct a plasmid containing the cDNA sequence for the truncated SV40 large T gene, a fragment containing the coding sequence for the first 155 amino acids of the T antigen was generated by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the A7 cell line (Geller and Dubois-Dalcq, 1988) as a template. The A7 cell line contains the full-length cDNA of SV40 large T integrated into its genomic DNA. The PCR oligonucleotide primers, custom synthesized by Gibco Life Technologies (Gaithersburg, MD), were SV40-5226 (5′tattccagaagtagtgaggagg) and SV40-4352-Not (5′cgcgcgaagcttaatgttctattactaaacacagcatgctc). The latter primer contains an added stop codon and Not1 restriction endonuclease site at the 5' end. PCR amplification was carried out using Perkin-Elmer GeneAmp reagents (Foster City, CA). The amplification conditions were: 30 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 55°C for 30 s, and elongation at 72°C for 30 s The PCR products were agarose gel purified using kit reagents from Qiagen Inc, (Chatsworth, CA), and ligated into a pCRII TA cloning vector (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA). The insert was isolated from positive colonies by Hindlll and Not1 digestion and subcloned into a pRc/RSV expression vector (Invitrogen), which includes the Rous sarcoma virus LTR to drive expression and the neomycin resistance gene for selection. The region of the plasmid insert was sequenced in both directions to verify the T155 cDNA sequence (Johns Hopkins DNA Sequencing Facility, Baltimore MD).

Construction of mutant T155c vectors

A series of deletion and substitution mutants of the T155c plasmid were generated by site-directed mutagenesis (Fig. 1) using a two-side overlap extension PCR method (McPherson, 1991). The pRc/RSV/T155c plasmid was used as the template. The PCR primers for each mutant were two complementary mutagenic primers and two flanking primers (PREP forward primer and pcDNA3.1/BGH reverse primer, Invitrogen). The mutagenesis was accomplished by combining each mutagenic primer with a flanking primer and carrying out the first two PCR reactions (95°C for 2 min, then 25 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 55°C for 30 s, elongation at 68°C for 30 s, followed by a final elongation step at 72°C for 5 min). The resulting two PCR products were combined and annealed, and a third PCR reaction was carried out with only the two flanking primers. The final PCR product, which contained the mutation or deletion, was cloned into a PCR TA vector (Invitrogen), and then shuttled into pRc/RSV/T155c vector, replacing the T155c insert. The inserts of each mutant plasmid were sequenced in both forward and reverse directions to confirm the success of the mutagenesis (Johns Hopkins DNA Sequencing Facility).

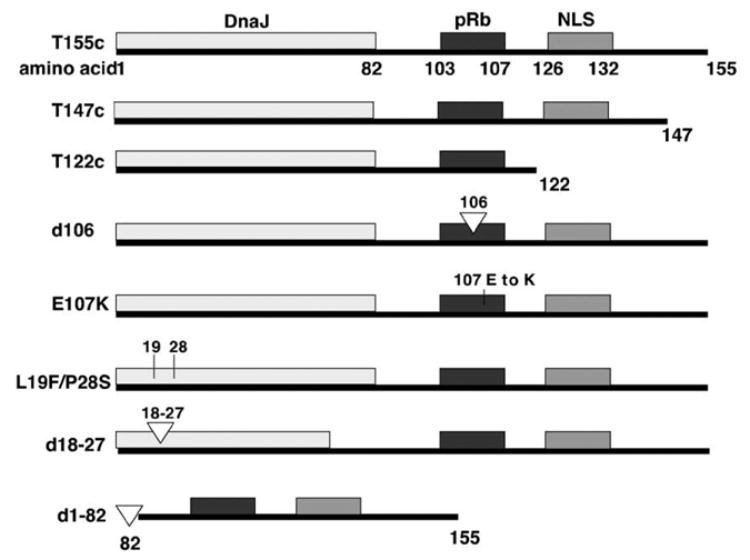

Fig. 1.

Diagram of T155c peptide and mutant variants. The regions corresponding to the DnaJ domain, the pRb and pRb-family binding region, and the nuclear localization signal (NLS) are shown.

Cell cultures

T64-7B cells were provided by Dr. Arnold J. Levine, Princeton University. These cells were derived from rat embryo fibroblasts transformed by activated ras and a temperature-sensitive mutant of p53 (Martinez et al., 1991; Michalovitz et al., 1990). The cells actively divide at 37–39°C and are blocked in the G1 phase of the cell cycle at 32°C. The cells were maintained in a 5% CO2 incubator in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM, Gibco Life Technologies) containing 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin G, 100 μg/ml streptomycin.

Primary embryonic rat brain cultures were established using standard methods. The brains from day 13 (E-13) Sprague-Dawley embryos were removed, and the ventral mesencephalon or cerebral cortex was dissected under sterile conditions. The cells were mechanically dissociated and plated in 25 cm2 flasks in culture medium consisting of Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's medium/Ham's F12 (DMEM/ F12, 1:1), 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ ml penicillin G, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 20 ng/ml human recombinant basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF, Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, or Sigma Co., St. Louis, MO).

To induce differentiation, CO5 cells were cultured to 90% confluence and then treated with neurobasal media (Gibco Life Technologies) supplemented with 50 μM dibutryl cyclic AMP (Sigma) for 48 h.

Transfections and cell cloning

T64-7B cells were transfected with pRc/RSV-T155c or mutant variants using either DOTAP (Boehringer-Mannheim), or LipofectaminePlus (Gibco Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's recommendations for transfection of adherent cells. The cells were in log-phase growth in 25 or 75 cm2 flasks at about 30% confluence at the time of transfection. For T155c-transfected cultures, after 3–5 days, the cells were replated into 12-well dishes in selection medium containing G418 antibiotic (0.5 mg/ml) (Geneticin, Sigma or Gibco Life Technologies) and placed in a 33°C incubator (the non-permissive temperature for T64-7B cells). Colony formation was monitored over a 3-week period. Colonies were expanded, passaged several times, and screened by immunocytochemical staining with antibodies for SV40 large T antigen (see Immunocytochemistry below). Clones from positive-staining colonies were derived by limiting dilution. After 2 weeks, surviving cells were stained for SV40 large T and replated for proliferation assays (see below).

Primary rat mesencephalon or cortical cells were cultured for 5 days, then subcultured into poly-D-lysine-coated 6-well plates. The following day, the cells (about 80% confluent) were transfected with pRc/RSV-T155c or E107K using Fugene 6 (Boehringer Mannheim,), following the manufacturer's directions. For each well, 2 μg of plasmid DNA was mixed with 6 μl of Fugene 6 and 100 μl of culture media. The media was changed the following day. After 5 days, culture media containing 20 ng/ml bFGF and 250 μg/ml G418 antibiotic was added. After 4 weeks, individual colonies derived from single cells were collected using cloning rings, and expanded.

Proliferation analyses

T64-7B cells transfected with T155c, mutant variants of T155c, or untransfected cells were plated into two 25 cm2 flasks each, at a density of 2 × 105 cells per flask, and allowed to attach for 24 h at the permissive temperature, 37°C. One flask from each group was then switched to 33°C, and a minimum of 100 cells total, in 10–25 fields (1.88 mm2 field size) per flask were counted daily using phase microscopy for 15 days.

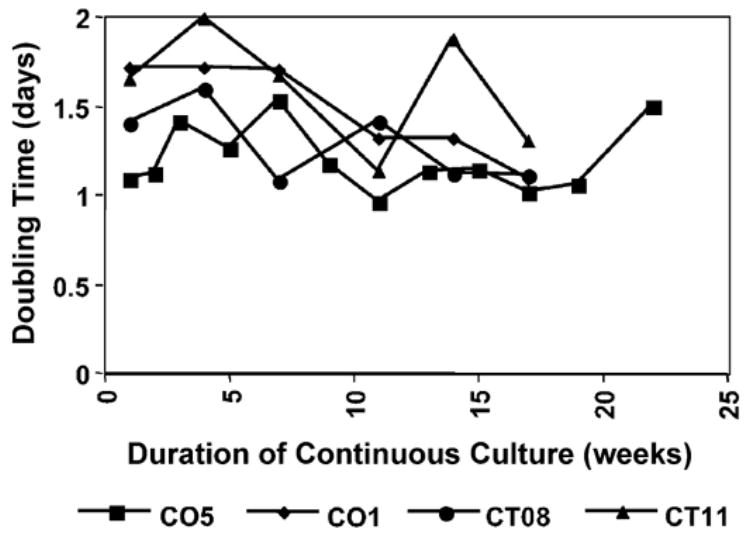

The CO1, CO5, CT08, and CT11 cell lines were cultured for up to 24 weeks in 25 cm2 flasks, passaging the cells each week by reseeding them at a density of 2 × 105 cells per flask. At 2- to 3-week time intervals, the cells were counted for four consecutive days after passaging. Cells in live cultures were counted visually using a 20 × lens on an inverted Nikon microscope (30–50 fields per flask). The number of days required for the cells to double in number (doubling time) was estimated from these cell counts by fitting the growth curve to the logarithmic function y = a log x - b, where y = number of days, x = number of cells, and a and b are constants. Doubling time in days was obtained by multiplying by the factor a = 0.301. The cumulative number of population doublings over time was derived from these calculations.

For growth factor requirement analysis of the cell lines, cells were plated with basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF, 20 ng/ml) in the media and allowed to grow for two more passages. The cells were then plated into two flasks for each cell line and allowed to settle for 1 day; on the next day, the media in one flask of each cell line was replaced with media lacking bFGF, while the remaining flasks received media with bFGF. Cells were counted everyday as described above and passaged two more times. In some cases, bFGF was then added and the cells counted for 4 or 5 more days.

Immunocytochemistry

Expression of T155c or mutant variants of T155c in T64-7B cells was tested by indirect immunocytochemistry using antibodies against different epitopes of SV40 large T. Cells grown in chamber slides (LabTek II), were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, permeabilized with ethanol/acetic acid (95:5) at −20°C for 1 min, and blocked for non-specific antigens with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 5% horse serum, 5% goat serum, and 1% bovine serum albumen for at least 20 min at room temperature. The cells were then incubated with primary antibody for 3 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. Cells were incubated in secondary antibody (Alexa 594-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), diluted 1:500 in blocking reagent, for 1 h at room temperature. The cells were washed three times with PBS at each step. After removal of the wells, Slow-Fade Light (Molecular Probes) mounting medium was applied to the slides, covered with a glass cover slip, and examined under a Zeiss microscope. The primary mouse monoclonal antibodies, diluted 1:100 in blocking reagent, were: Clone PAb416 (Ab-2) against SV40 large T amino-terminus (but not small t) (Oncogene Research Products, Cambridge, MA), Clone PAb419 (Oncogene Research Products) against amino acids 1–82 of the amino-terminal region, PAb 108 also against SV40 large T amino-terminal region between amino acids 1–82 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and PAb 101 against SV40 large T carboxyl-terminus between amino acids 518 to 708 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Cultures of cell lines derived from T155c-transfected primary rat cultures were prepared for immunostaining by fixing on ice with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.3 for 45 min After four 5-min rinses, non-specific binding was blocked by incubating the cells at room temperature with 0.01 M sodium phosphate buffer, 5% normal goat serum, and 0.2% triton X-100 for 1 h. The cells were then incubated with primary mouse monoclonal antibodies against SV40 (PAb 416, diluted 1:50, Oncogene Research Products); vimentin (1:50, Sigma); nestin (1:500, PharminGen), β-III-tubulin (1:1000, Promega, Madison, WI), or glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP 1:100, PharminGen) overnight at 4°C. For chromophore detection, cells were incubated in a 1:333 dilution of biotinylated anti-mouse IgG, followed by avidin complex (1:200, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Cells were visualized using 3,3'-diaminobenzidine (0.5 mg/ml in 0.05M Tris-HCL buffer, pH 7.6) with 0.01% H2O2. For light microscopy, the cells were dehydrated in graded ethanol (50%, 70%, 95%, 100%, xylene) and mounted on microscope slides with Permount mounting resin (Fisher Scientific, Fairlawn, NJ). For fluorescence detection, the secondary antibody was fluoroscein isothiocyanate-(FITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) or AlexaFluor 594 (Molecular Probes) diluted 1:200. After the final washes, the cells were coated with a thin layer of PermaFluor mounting medium (Beckman Coulter Inc, Fullerton, CA) and covered with glass coverslips. Images were observed using a Zeiss Axiovert 100 microscope.

T155C polyclonal antibody

The amino acid sequence DKGGDEEKMKKMNTC, representing residues 44–57 of SV40 LT antigen was employed to produce a rabbit polyclonal antibody to the N-terminal region. The antibody was produced by Sigma-Genosys (The Woodlands, TX), by synthesizing the above peptide, conjugating to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH), and immunizing rabbits with Complete Freund's Adjuvant followed by boosters with Incomplete Freund's Adjuvant.

The procedure for immunocytochemistry was similar to that described above, except that cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton-X 100 for min, incubated in 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate for 5 min at 37°C, and blocked with 5% normal goat serum prior to incubation with the primary antibody diluted 1:100 in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. The secondary antibody was anti-rabbit AlexaFluor 586 (Molecular Probes) diluted 1:200. Cells were washed with PBS after each step.

p53 gene sequence

Genomic DNA was extracted from cultured cells and from freshly dissected normal E13 rat fetal brain and tail tissues using a Qiaex Genomic DNA Extraction kit (Qiagen Inc) following the manufacturer's instructions. Oligonucleotides for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were custom synthesized (Gibco BRL Life Technologies) to anneal to the intron sequences flanking exons 5, 6–7, and 8–9. The primer sequences are shown in Table 1. DNA (0.02–0.5 μg) was added to a reaction mixture containing 20 nM of each oligonucleotide primer and PCR Supermix (Gibco BRL Life Technologies) in a 100 μl volume and subjected to amplification in a Perkin-Elmer thermocycler for 30 cycles of denaturation (95°C, 30 s), annealing (55°C, 30 s), elongation (72°C, 30 s). The amplification products were separated on 2% PE Express agarose gels (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, CA) containing ethidium bromide. The DNA bands were visualized under UV light and quickly excised then purified using kit reagents from Qiagen. DNA sequencing was performed in both the forward and reverse directions by the Johns Hopkins DNA Facility, using the PCR primers as the sequencing primers.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide PCR primers used for rat p53 gene sequencing

| Exon 5 | Sense

antisense |

GACCTTTGATTCTTTCTCCTCTCC

GGGAGACCCTGGACAACCAG |

| Exon 6–7 | Sense

antisense |

CTGGTTGTCCAGGGTCTCC

CCCAACCTGGCACACAGCTT |

| Exon 8–9 | Sense

antisense |

CTTACTGCCTTGTGCTGTGC

CTTAAGGGTGAAATATTCTCC |

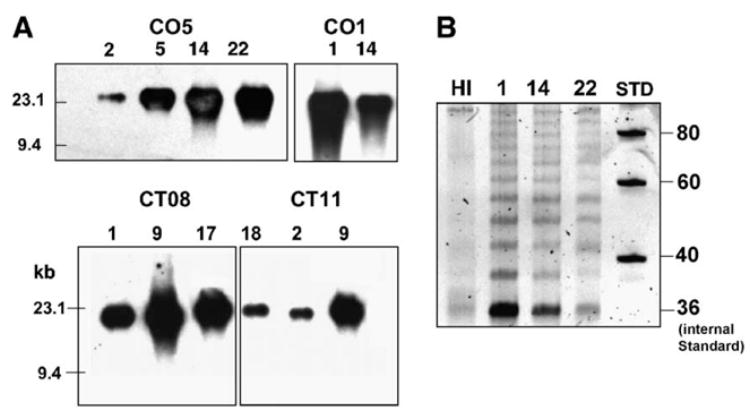

Telomere length assays

Telomere length was measured using PharminGen Teloquant kit, following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, genomic DNA from early and late passage cultures of cell lines CO1 (weeks 1, 14, and 22 in culture) and CO5 (weeks 2, 5, and 14) was extracted (Promega Wizard genomic DNA extraction kit). The DNA (2 or 2.5 μg) was digested with a mixture of Hinfl and Rsal restriction endonucleases. The resulting restriction fragments were resolved by electrophoresis on a 0.6% agarose gel and transferred onto a nylon membrane (Hybound-N+, Amersham, Piscataway, NJ). The membrane was hybridized with a biotinylated telomere probe provided in the kit, and detected by chemiluminescence according to the manufacturer's protocol. After washes with 2× SSC containing 0.1% SDS at room temperature and 0.2× SSC containing 0.1% SDS at 42°C, the membrane was incubated in blocking buffer (0.5% dry milk, 0.1% Tween-20, 20 mM Tris-buffered saline and 150 mM sodium chloride) and then in 25 ng/ml streptavidin-conjugated horse radish peroxidase in blocking buffer, each for 1 h at room temperature. Following washes with 0.1% Tween-20/PBS, the membrane was incubated in equal volumes of peroxide NA and Luminol/enhance NA for 5 min at room temperature. The membrane was exposed to X-ray film to visualize the bands.

Telomerase activity

Telomerase activity of cells was measured using a Telomeric Repeat Amplification Protocol (TRAP) (PharminGen). Cells were harvested from early and late passage cultures and washed with PBS. Cell pellets were stored at −80°C until assayed at the same time, after all samples were harvested. The pellets were solubilized with 200 CHAPS lysis buffer (0.5% w/v CHAPS: 3-[3-cholamindopropyl)di-methylammonio]-l-propanesulfonate), 10 mM Tris-HCl. pH 7.5, 1 mM sodium chloride, 1 mM EGTA, 0.1 mM benzamidine, 5 mM beta-mercaptoethanol, 10% w/v glycerol). Samples containing 0.45 and 0.9 μg of total protein were added to the PCR reaction mixture, which contained 10× TRAP buffer (200 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 15 mM magnesium chloride, 1% Tween-20, 630 mM potassium chloride, 10 mM EGTA, 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin), 0.1 μg of TS primer, deoxytrinucleotide mixture, primer mixture, and Taq DNA polymerase, in distilled deionized water. The PCR conditions were: one cycle at 30°C for 30 min followed by 30 cycles of denaturing at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 58°C for 30 s and elongation at 72°C for 30 s. PCR products were resolved by 12.5% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel. The telomere repeats were viewed by staining the gel with SyBrGreen (Molecular Probes). The image was captured with an AlphaEase imaging system (Alpha Innotech Corp., San Leandro, CA). The control reactions were heat-treated cell lysates (85°C, 10 min), or no lysate.

Results

T155c plasmid and mutant constructs

The DNA sequence in both forward and reverse directions showed that the T155c insert was 100% homologous to the appropriate region of the SV40 large T (LT) cDNA sequence (Tooze, 1980). Likewise, the DNA sequences of the deletion and substitution mutants were confirmed. Fig. 1 shows diagrams of T155c peptide and variants. T147c is a shorter cDNA fragment, encoding the first 147 amino acids, and T122c eliminates the coding region for the nuclear localization sequence (NLS). The d106 mutant construct was used as a mock Rb-binding region mutation because, although the mutation was within the binding sequence, the binding sequence was not changed. The amino acid in position 106 was eliminated in the pRb-binding motif LXCXE (amino acids 103–107); however, amino acid 108 is also E, thus the LXCXE pRb binding motif remained intact. For mutant E107K, the glutamic acid moiety in position 107 (E) was mutated to lysine (K), thereby eliminating the pRb binding motif. Three mutations in the DNA J domain were employed, these included L19F plus P28S, in which amino acid number 19 was mutated from L (leucine) to F (phenylalanine) and amino acid number 28 was mutated from P (proline) to S (serine). There were also two deletion mutants in the J domain, including d18–27 which eliminates amino acids 18 through 27, and d1–82 in which the entire amino-terminal 82 amino acids were removed.

T64-7B cells

Transfection and selection

In preliminary experiments, transfected cells were placed in a 33°C incubator, the non-permissive growth temperature, in medium containing G418. In subsequent experiments, the cells were left at 37°C to speed the growth of the cells and colony formation. At either temperature, most of the cells died within 2 days of culture in G418. Surviving cells grew into colonies within 2 weeks at 37°C and 3–4 weeks at 33°C. In some cases, individual colonies were harvested and cloned by serial dilution; while in other cases, the colonies in a given flask were passaged and grown as an uncloned population.

Expression of T155c and mutants

T64-7B cells transfected with T155c or variants of T155c (Fig. 1) were screened for immunoreactivity with antibodies against different epitopes of LT (Table 2). T155c and T147c showed positive immunoreactivity, located in the nuclei, with antibodies that bind to regions within the LT amino-terminal region. These antibodies were PAb 416, which reacts with a region between amino acids 82–128, and PAb 108, which reacts within amino acids 1 to 82. Cells expressing T122c, which lacks the LT nuclear localization signal, showed both nuclear and cytoplasmic immunoreactivity with both antibodies against LT amino-terminal regions. The mutant variants d106 and E107K also showed nuclear staining with antibodies against LT amino-terminal regions. The cells transfected with mutant L19F + P28S, both the pooled population and the clones, showed nuclear staining with PAb416 but not PAb108, suggesting that the mutations within the DnaJ domain disrupted the structure in that region while leaving the pRb-binding area intact. Neither the pooled population nor the clones of cells transfected with the mutants d18–27 and d1–82 stained with PAb419 or PAb108, and weakly with PAb416. Because these mutants have large areas of deletion, the antibodies may not have been able to recognize the resulting structures. Staining with the negative control antibody, PAb101, against LT carboxyl-terminus, was negative in cells transfected with all of the constructs, as expected because the carboxyl-terminus of LT is missing from all constructs.

Table 2.

Immunostaining of T64-7B cells transfected with T155c and mutants

| Vector | PAb416 (82–128) | PAb419 (1–82) | PAb108 (1–82) | PAb101 (c-terminus) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T155c | +++ | ++ | +++ | − |

| T147 | +++ | ++ | +++ | − |

| T122 | ++* | ND | ++* | − |

| d1-82 | + | − | − | − |

| d18-27 | ++ | − | − | − |

| D106 | +++ | + | +++ | − |

| E107K | +++ | ++ | +++ | − |

| L19F, P28S | ++ | − | − | − |

| Vector | − | − | − | − |

| Normal | − | − | − | − |

The amino acid region of SV40 large T in which each antibody binds is given in parentheses.

Vector = cells transfected with pRc/RSV vector with no insert. Normal = cells not transfected; +++, very strong staining; ++, strong; +, weakly positive; −, no staining; ND, not done.

All staining was nuclear except for T122, which showed both nuclear and cytoplasmic staining.

Rescue from growth arrest

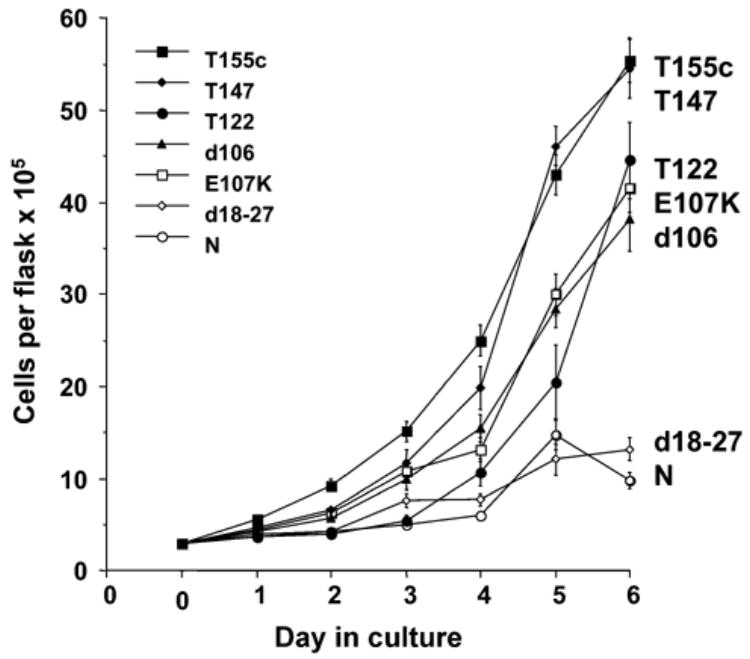

Cells expressing T155c or variants were plated into two 75 cm2 flasks for each construct at 2 × 105 cells per flask, and one flask from each condition was placed in a 33°C incubator and the other in a 37°C incubator. The cells were counted daily until the cultures that were proliferating in the 33°C incubator reached confluence, which was about 6 days. Counts were continued in the flasks at 33°C up to 15 days to insure that the apparent growth-arrested cultures did not begin to grow after a longer time in culture. Fig. 2 compares the growth rates of cells compiled from two separate transfections of each construct and five separate experiments. All constructs tested except d18–27 and the untransfected cells resulted in some proliferation at the non-permissive temperature. T155c and T147c generally gave the most robust growth at 33°C, while cells expressing T122c (NLS missing), E107K (pRb-binding site disrupted), and d106 (mock pRb-binding disruption) also grew at the non-permissive temperature, although at a slower rate, but reached confluence after about 7 or 8 days in culture. All cultures grew to confluence within 6 days at the permissive temperature, 37°C (not shown).

Fig. 2.

Growth of T64-7B cells (p53 temperature-sensitive cell line), transfected with T155c and mutant variants, at the non-permissive temperature. Data were combined and averaged from growth curve experiments repeated five times using cells from two separate transfections with each construct, except L19F/P28S which was one experiment. N = cells transfected with vector only.

Cell lines derived from primary rat fetal cell cultures

Summary and T antigen fragment expression

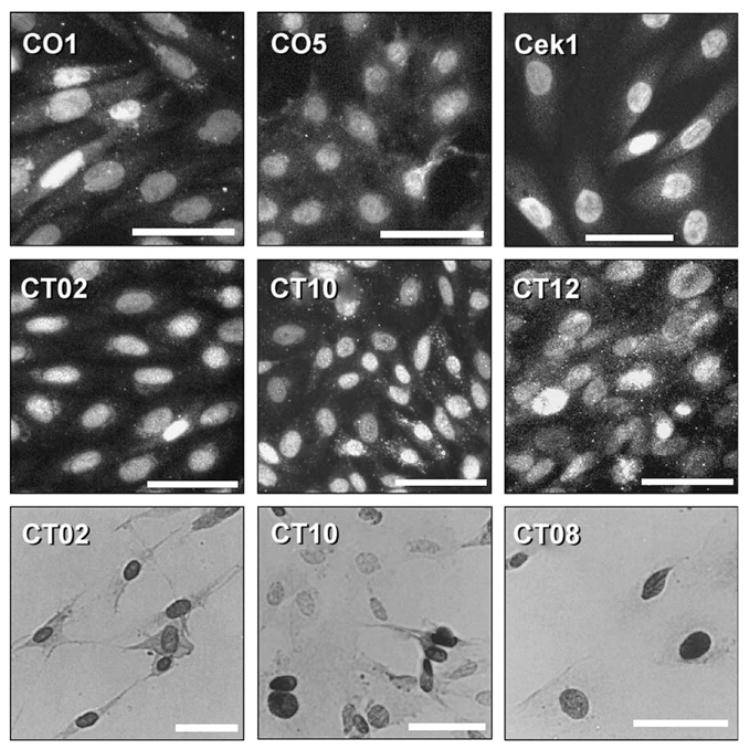

Transfection experiments were performed using primary fetal mesencephalic and cerebral cortical cultures from E12 to E14 rats. Using T155c, five clones were initially obtained from mesencephalic cultures, although only two survived long-term culture. The two cell lines from mesencephalon were designated C01 and CO5. Five cell lines were obtained from cerebral cortical cultures, and were designated CT02, CT08, CT10, CT11, CT12. Although all five grew and were initially studied, only three of these, CT02, CT10, and CT12, have survived and are available as frozen stocks. CT08 and CT11 have been lost. A single cell line was obtained using E107K. This line, designated Cek1, was obtained from a mesencephalic culture at passage 4, day 12 gestation by transfecting the culture three times on successive days. Each of these cell lines showed positive nuclear immunoreactivity using antibody PAb416 against the N-terminal of the SV40 large T antigen and/or with the SV40 N-terminal polyclonal antibody. Examples are shown in Fig. 3. Immunoreactivity of the Cek1 cell line was observed for the polyclonal antibody only (Fig. 3). None of the cell lines were positive for carboxyl-terminal LT. For several cell lines, the presence of the T155c gene was verified by PCR, and for Cek1, expression of the T155c-E107K fragment was also verified by rt-PCR (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Examples of immunostaining of mesencephalic and cortical cell lines using the SV40 N-terminal polyclonal antibody (upper six frames) or antibody PAb416 (lower three frames). The upper six frames show immunofluorescence staining and the lower three are 3,3′-diaminobenzidine detection. Calibration bar = 50 μm.

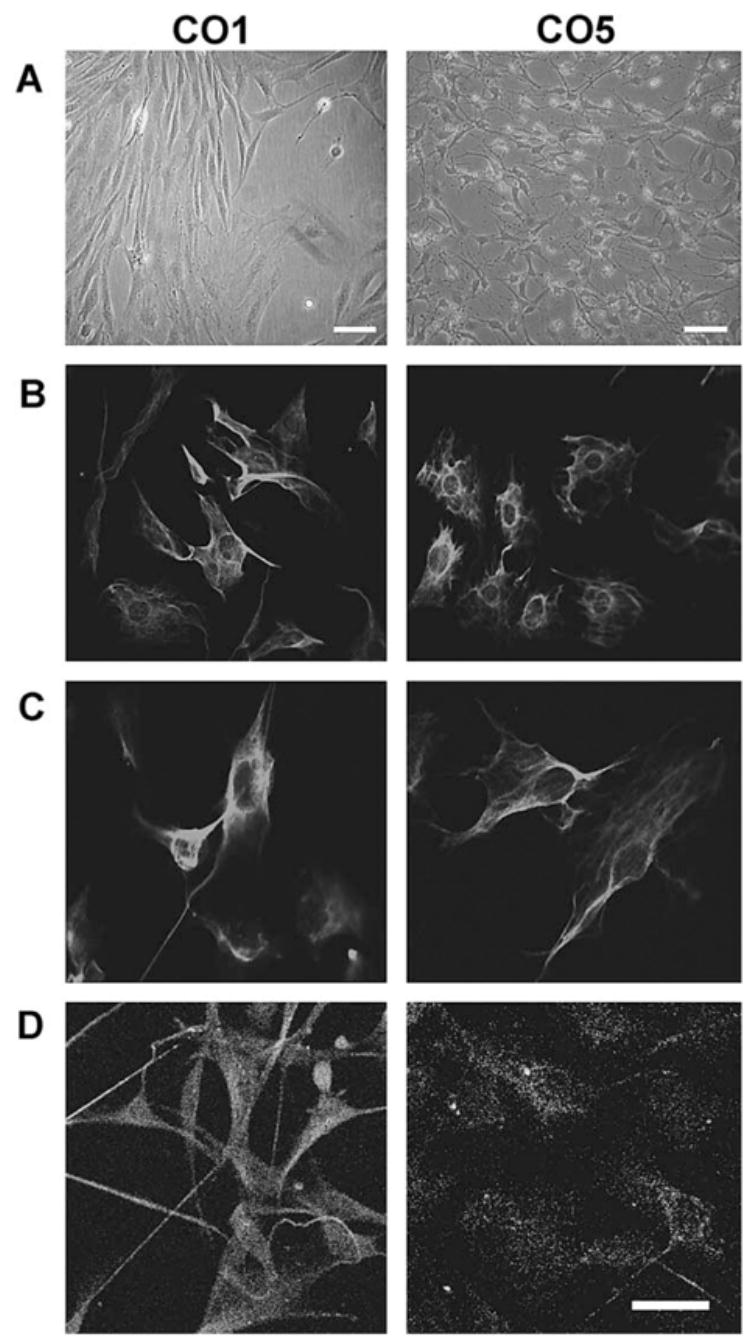

Mesencephalic cultures and T155c plasmid

Fig. 4 shows the general appearance of these cell lines. CO1 had an elongate, generally bipolar shape. The CO5 cell line had a more stellate, but variable morphology, and showed the unusual property of growing in two layers, with a lower layer of cells attached to the substrate and the upper cell layer extending cytoplasmic processes on top of the substrate layer of cells.

Fig. 4.

T155c-transfected rat mesencephalic cells, clones CO1 and CO5. The upper two frames show phase contrast images. Row B: immunofluorescence staining for vimentin; row C: nestin; row D: GFAP. Calibration bar = 40 μm.

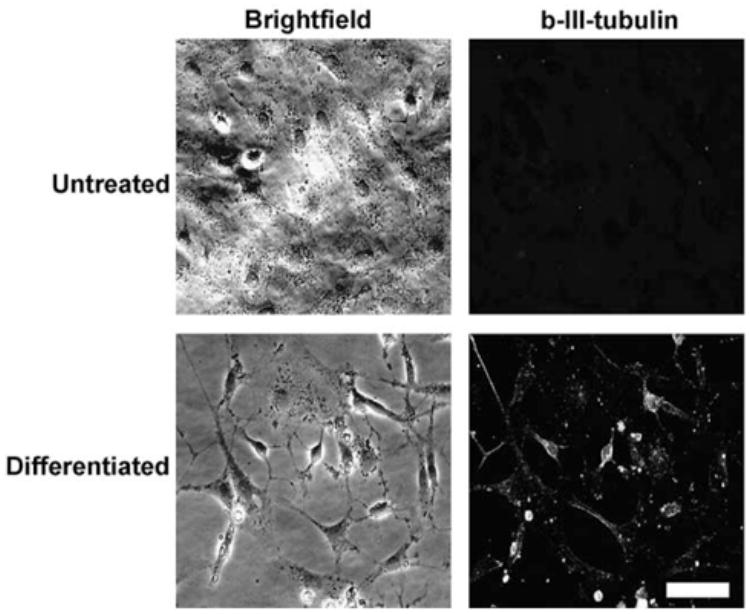

Both CO1 and CO5 cell lines showed positive immunostaining for amino-terminal LT, nestin, and vimentin; CO1 was positive for GFAP, but CO5 was not (Fig. 4). The CO5 cell line differentiated readily when treated with neurobasal medium and 50 μM dibutyryl cyclic AMP (Fig. 5). After 48 h, many of the cells had developed compact cell perikarya and long processes and were positive for (β-III Tubulin.

Fig. 5.

CO5 cells express TUJ-1 during differentiation. Sub-confluent CO5 cells were treated with Neurobasal media + 50 mM dbcAMP for 48 h or left untreated. Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and probed for β-III tubulin expression using specific antisera. Indirect immunofluorescence indicates an up-regulation of β-III tubulin expression as CO5 cells convert to neuronal phenotype. Calibration bar = 50 μm.

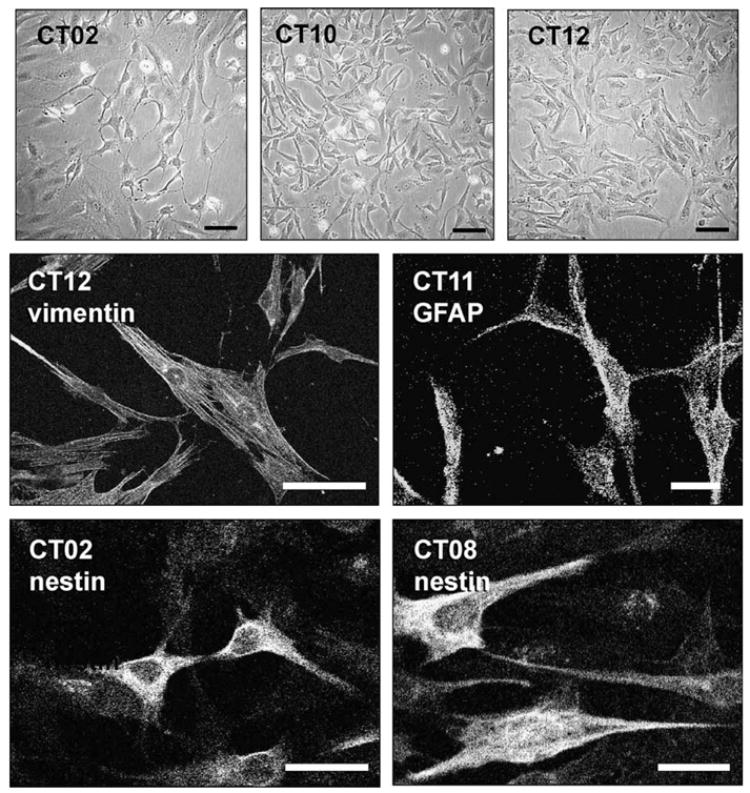

Cerebral cortical cultures and T155c plasmid

The cortical cell lines were positive for nestin and vimentin. CT11 was also positive for GFAP. Examples of immunostaining and phase contrast images of these cell lines are shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Cortical cell lines CT02, CT08, CT10, CT11, and CT12. The upper three frames show phase contrast images of three of the cell lines. Examples of vimentin, GFAP, and nestin staining are shown. Only CT11 expressed GFAP. Calibration bars =100 μm.

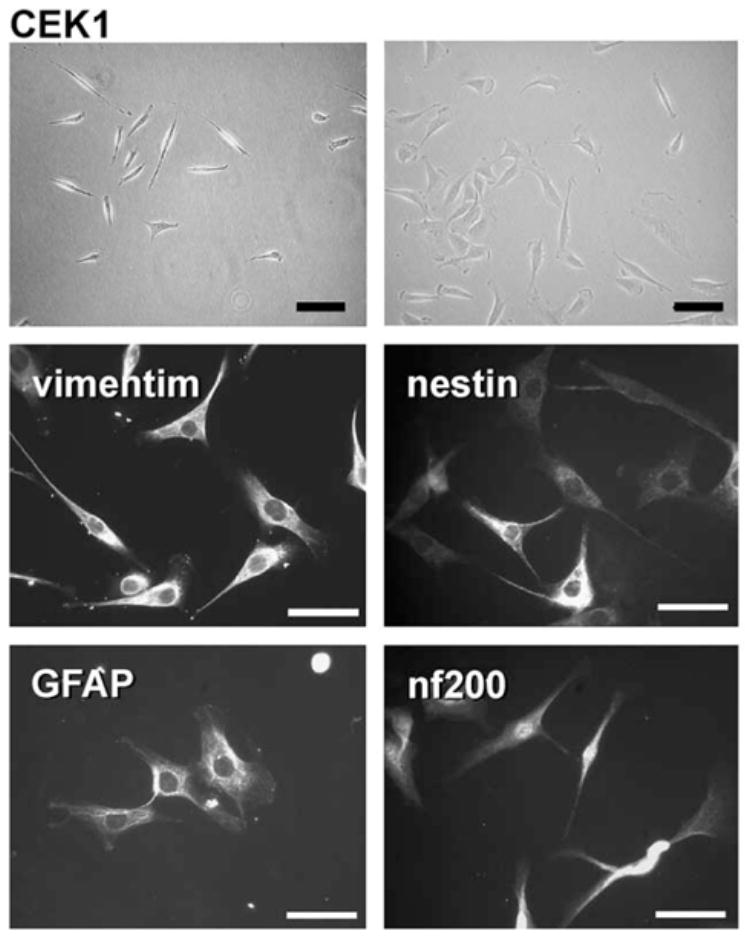

Mesencephalic cultures and El07K plasmid

The Cek1 cell line was derived from a mesencephalic culture using E107K. Although only a single cell line was obtained, and it seemed that it was more difficult to immortalize cells using E107K as compared to T155c, we do not have quantitative data to support that conclusion. Cek1 was immunopositive for vimentin, nestin, GFAP, and neurofilament 200 kDa (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

The mesencephalic cell line Cek1. The upper two frames are phase contrast, and the four lower frames show immunofluorescence staining as indicated. Calibration bar = 100 μm.

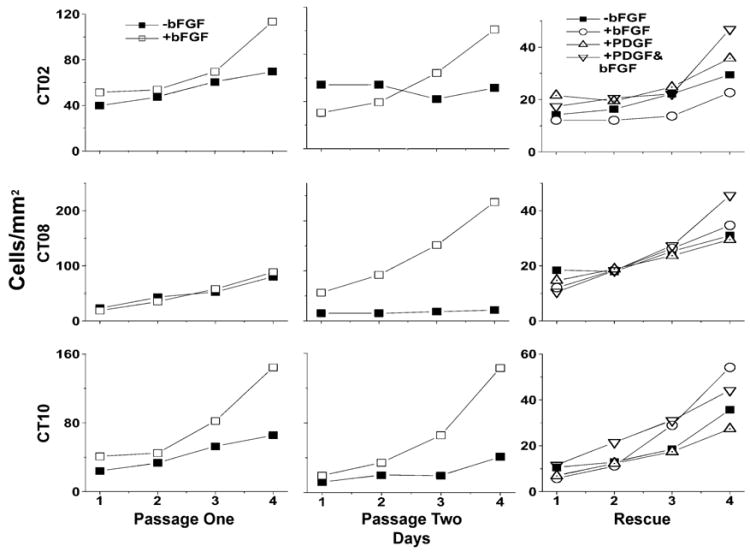

bFGF dependence and growth properties

In general, the cell lines derived using either T155c or E107K were highly dependent upon bFGF for continued growth. CO1 or CTO2 cells that were passaged without bFGF in the culture media formed large flat cells with a feathery cytoplasm (not shown), and their growth rate diminished greatly (Fig. 8). After 2–4 passages without bFGF, the cells no longer divided and did not survive. If bFGF was added to the culture media after the cells reached a non-dividing state but before cell death, the cells resumed mitosis and returned to the elongate shape.

Fig. 8.

Several of the cell lines immortalized with T155c were highly dependent on bFGF for growth, although this observation was not consistent in all cases. The graph shows cell density over time for three of the CT cell lines. When passaged without bFGF, growth of these cell lines stopped or was greatly attenuated. For the third passage, labeled “rescue”, bFGF, PDGF, or both, were added to cells that had been maintained without bFGF.

In some cases, growth ceased almost completely when bFGF was removed from the medium. Generally, the difference in growth was more apparent after the cells had been grown for 1 week and passaged without adding bFGF to the medium (Table 3 and Fig. 8). When bFGF was added to the medium, rapid growth resumed within 2 or 3 days (Fig. 8). However, the bFGF dependence of the cell lines was inconsistent even for the same cell line tested repeatedly (Table 3).

Table 3.

Growth of cell lines when passaged with and without bFGF

| No bFGF* |

+bFGF* |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell type | Plating density (cells/cm2) | Week 1 | After passage | Week 1 | After passage |

| CO1 | 4000 | 312 | 73 | 589 | 941 |

| CO5 | 20,000 | 293 | 262 | 782 | 505 |

| CT02 | 4000 | 292 | 671 | 900 | 782 |

| CT02 | 4000 | 175 | 95 | 214 | 331 |

| CT08 | 4000 | 351 | 146 | 472 | 422 |

| CT10 | 2000 | 273 | 339 | 353 | 735 |

| CT10 | 4000 | 306 | 611 | 2988 | 850 |

| CT10 | 20,000 | 453 | 700 | 776 | 607 |

| CT12 | 4000 | 413 | 379 | 1683 | 2444 |

| CEK1 | 4000 | 445 | 960 | 615 | 1008 |

| CEK1 | 20,000 | 318 | 171 | 491 | 401 |

Data shown are percentage increase in cell number over 4 days.

Stability of cell lines

Long-term growth

Four of the cell lines, CO1, CO5, CT08, and CT11, were passaged each week for 17 to 22 weeks at a density which allowed log phase growth over a 5-day period, and counted daily at 2- or 3-week intervals over a 5-day period. Doubling time (the time required for cells to double in number) and number of population doublings (PD, the number of times the population doubled during the growth curve) were calculated from the growth curves. This procedure was designed to determine increases or decreases in growth rate over an extended period of time in culture. Fig. 9 illustrates that, throughout the time period assayed (at least 100 population doublings), the CO5, CT08, and CT11 cell lines maintained relatively stable growth rates. CO1 showed a distinct growth acceleration over time, from a doubling time of 1.7 days at weeks 1–7 to 1.09 at week 17. These results, in addition to passaging the cells beyond the experimental time frame, indicate that that the cells are indeed immortalized and showed no signs of senescence or crisis. In addition, with the possible exception of CO1, it did not appear that there were additional mutations, which promoted rapid growth, or emergence of rapidly growing subclones.

Fig. 9.

Growth rates of CO1, CO5, CT08, and CT11 and cells over time. Cells were replated each week and counted over a 5-day period at the time points indicated. Population doubling was calculated based on log-phase growth fit for the curves generated at each time point.

Telomere length and telomerase activity

Fig. 10A shows the telomere length of the CO1, CO5, CT08, CT11, and cells at different time points in culture. These data correspond to the same cells used for the growth curves in Fig. 9. While the amount of telomeric DNA was variable, telomere lengths did not shorten or change over time. Telomerase activity of clone CO5, as measured by a TRAP assay, (Fig. 10B) shows that activity persisted through the experimental time frame.

Fig. 10.

Telomere length and telomerase activity. (A) Telomere length for clones CO5, CO1, CT08, and CT11. Numbers above each lane show the number of weeks each cell line was maintained in continuous culture. The samples corresponded to the time points in Fig. 9. Size markers are in kilobases. (B) Telomerase activity for clone CO5. Lane 1, heat inactivated sample; lanes 2–4 represent clone CO5 at week 1,14, and 22. STD is a 20-bp size standard. The 36-bp band is an internal standard.

p53 sequence analysis

The p53 gene was sequenced in three regions corresponding to exons 5, 6–7, and 8–9 for CO1 and CO5, which were reported to be the most likely areas for mutations in rat tumor cells (Vancutsem et al., 1994). In DNA extracted from both early and late passage cultures of both cell lines, the sequences were 100% homologous to normal p53 gene or cDNA sequences (Hulla and Schneider, 1993). These results indicate that the p53 gene in these cell lines was not mutated in the course of generating the cell lines or after multiple passages in culture.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to explore the possibility of constructing an agent for immortalizing mammalian cells in culture that has a minimal potential to interfere with normal cellular machinery. In previous studies, we constructed a plasmid vector to express T155, now called T155g, which contains a genomic DNA sequence from the SV40 early region that encodes the first 155 amino acids of SV40 large T (LT) and also small t as an alternative splice product. Expression of T155g, though lacking the binding domain for p53, was capable of overcoming growth arrest in a p53 temperature-sensitive cell line, T64-7B, and could immortalize primary fetal rat mesencephalic cells which retained phenotypic properties similar to primary neural progenitor cells (Truckenmiller et al., 1998, 2000). In the present study, we describe a construct derived from the cDNA of T155, called T155c, which expresses the truncated LT but not small t, and a series of deletion and substitution mutants of T155c.

LT is the most thoroughly studied of the agents commonly used for immortalizing mammalian cells. Extensive analyses of this 708 amino acid protein have identified three major domains involved in immortalizing or transforming cells by interacting with cell cycle regulatory proteins. Residues 1–82 form complexes with the nuclear protein pRb and pRb-related proteins p107 and p130, and have functions of the DnaJ domain family of molecular chaperones (Brodsky and Pipas, 1998; DeCaprio, 1999;Kelley, 1998; Srinivasan et al, 1997). The LXCXE motif (residues 103–107) binds the retinoblastoma protein (pRb) and family members p107 and p130 (DeCaprio et al., 1988; Stubdal et al, 1996). It is believed that the N-terminal DnaJ domain cooperates with the Rb-binding domain to dissociate Rb-E2F complexes, thereby promoting re-entry of non-dividing cells into the cell cycle (Kim et al, 2001a; Zalvide et al, 1998). In the carboxyl half of LT, two regions within residues 351–626 function as p53-binding and inactivating domains (Kim et al, 2001b; Lane and Crawford, 1979; Linzer and Levine, 1979; Sarnow et al, 1982).

One of the purposes of the present study was to explore the minimum requirements for immortalizing primary CNS cells in vitro while avoiding the potential for tumorogenicity, with less concern for efficiency of immortalization. There have been contradictory reports regarding which domains of LT are required for immortalization, although the choice of cell type and methods may contribute to the disparities, (Conzen and Cole, 1995; Kierstead and Tevethia, 1993; Maclean et al, 1994; Tevethia et al, 1988; Thompson et al, 1990). In a previous report (Truckenmiller et al, 1998), we described a plasmid construct, called T155, which expresses only the first 155 amino acids of LT, and therefore lacks the p53 binding domain, and demonstrated that it is capable of immortalizing fetal rat mesencephalic cells after stable transfection in vitro. A portion of the T155 DNA sequence also encodes SV40 small t by an alternative splicing mechanism, and the two proteins have amino acid residues 1–82 in common (Jog et al, 1990;Paucha et al., 1978). Small t is believed to be critical for the transformation of cells but is not required for immortalization (Bikel et al, 1986, 1987; Bouck et al, 1978; Fanning, 1992). While the functions of small t are incompletely understood, in cells that have been subjected to SV40 infection, it is reported to enhance viral replication and polyploidy of the host cells (Whalen et al, 1999) to facilitate transformation of the infected cells by LT in limiting growth conditions (Bikel et al, 1987; Martin and Chou, 1975; Rubin et al, 1982) and to promote induction of cell cycle progression in non-dividing cells, (Porras et al, 1999). Known cellular targets for small t are hsc70 (Srinivasan et al, 1997) and protein phosphatase 2A (Pallas et al, 1990; Yang et al, 1991). Other reported functions of small t include transcriptional activation of promoters of AP-1 (Frost et al, 1994) cyclin A (Porras et al, 1999), and cyclin D1 (Watanabe et al, 1996), repression of c-fos promoters (Wang et al, 1994), and down-regulation of the cdk inhibitor p27KIP1 (Porras et al, 1999).

The T155c-E107K construct, in which the LXCXE motif that binds the pRb family of proteins was disrupted by mutating the E to K, also produced delayed growth. This growth rate was on the average about the same rate as cells expressing d106, which does not disrupt the LXCXE sequence but contains an altered downstream sequence due to the cDNA frame shift. In contrast to these results, both Quartin et al. (1994) and Gjoerup et al. (2000) report that a cDNA construct expressing the amino-terminal 135 amino acids of LT without small t and containing the E107K mutation (LT1-135 Kl) produced no colonies of T64-7B cells in a colony-forming assay. Our system differs in several respects, and any one or combination of these differences could account for the discrepancy. T155c is 20 amino acids longer, and although this additional sequence does not include other known functional domains, it may affect structure or other features of the peptide. We used a plasmid vector having different promoter and selection properties. We allowed the T64-7B cells to grow at the permissive temperature following transfection until transfections were well established. After extensive selection in G418, which insured survival of only stable transfectants, the cultures were immunostained for LT to insure that 100% of the cells expressed the constructs before performing growth curves. Perhaps the most significant difference is that our assay system was to monitor rates of growth rather than count colony formation. While the T155c-E107K mutant showed a growth rate at the non-permissive temperature that was delayed in comparison to the T155c parent construct, growth was consistent and repeatable using different batches of transfected cells.

It would therefore appear that, at least under the conditions of our system, a construct lacking the p53 binding domain and with a disrupted Rb-binding domain was still able to override, albeit weakly, the temperature-sensitive cell cycle block in T64-7B cells. This result was unexpected because the ability to override p53-induced cell cycle is believed to occur via mechanisms relating to inhibiting the growth-arresting properties of pRb (Pomerantz et al., 1998; reviewed in Harbour and Dean, 2000. With the pRb binding domain disrupted, this would essentially leave the DnaJ domain to participate in this mechanism. There is a great deal of speculation, some contradictory, regarding the role of the LT DnaJ domain in the process of cell immortalization. The DnaJ domain of LT may function as a chaperone for the rearrangement of protein complexes, and other functions have been proposed (DeCaprio, 1999; Eckner et al., 1996; Srinivasan et al., 1997). However, the relationship of these functions to cell immortalization remains to be determined. Nonetheless, it appears that amino acids 1–82, at least, must be intact for sustained growth stimulation in the T64-7B cell line model.

Immortalization is normally characterized by overcoming two growth barriers in culture, senescence and “crisis”. Senescence is a poorly understood phenomenon exhibited by non-immortal cells in culture, characterized by an exit from the cell cycle but continued long-term viability (Campisi, 1997; Wynford-Thomas, 1997, reviewed in Sherr and DePinho, 2000). Senescence may result at least in part from telomere shortening, which occurs when the 3' ends of chromosomes are incompletely replicated with each round of cell division (Levy et al., 1992; Wellinger and Sen, 1997). LT is believed to delay senescence and increase the life span of cells beyond the normal limit of approximately 50 population doublings. However, continued proliferation then gives way to slowed growth, chromosomal instability, and high rates of cell death, or “crisis” (Girardi et al., 1966). Human cells rarely escape crisis to become immortal. Stabilization of telomeres is required for escape from crisis and subsequent continued growth and immortality. This stabilization usually occurs via telomerase activity (Greider and Blackburn, 1985; Kim et al., 1994) which maintains telomere length, or sometimes by proposed alternate mechanisms (Bryan et al., 1995). Murine somatic cells have longer telomeres (Kipling, 1997) and appear to be more predisposed to immortalization and transformation than human or rat cells. One rodent cell line immortalized by Passaging, WB-F344, showed highly variable telomere lengths and telomerase activity during long-term culture (Golubovskaya et al., 1999). Cell lines derived by passaging generally show a loss of p53 or p19ARF function (Kamijo et al., 1997; Zindy et al., 1998) over time in culture. We observed that telomeres of cells immortalized by T155c were stable over time, from very early passage to late passage cells, and that telomerase activity in the CO5 line was present over the same time period.

Chromosomal abnormalities are expected to occur in cells that become immortal, and even in cells that are merely subjected to the artificial growth conditions of cell culture. Mutations in the p53 gene are common in numerous types of tumors. Because T155c successfully immortalized primary CNS cells in culture, we wished to eliminate the possibility that immortalization may have resulted in part from spontaneous mutations in the p53 gene, which has been shown to cause immortalization of mouse fibroblasts (Kamijo et al., 1997; Zindy et al., 1998). Sequence analysis of DNA from the CO1 and CO5 cell lines confirmed that there were no mutations in the p53 gene regions reported to be most susceptible to mutation even after multiple passages and long-term culture.

Moreover, growth rates were generally stable over time, and it did not appear that faster-growing subclones that had accumulated additional mutations emerged over time in culture. Therefore, CNS cells immortalized by T155 show stable telomeres, stable growth over time in culture, and do not have mutations in the p53 gene that contribute to immortalization.

Improved methods for immortalizing cells at various stages of differentiation may be important in the long term for the development of cell-based therapies. Cell lines that can be maintained in vitro for extended periods and subjected to various manipulations may allow for the production of cells with specific engineered properties that are optimized, by subsequent genetic modification, for the production of growth factors, hormones, or other substances, or for the development of synaptic connections with the mature host brain (cf. Freed, 2000). The plasmid-based immortalization strategy employed in the present study will not be the ideal technique for long-term use with human cells that are intended for therapeutic applications. Nonetheless, the minimalized oncogenes, which are employed here, are likely to interfere less with normal cellular growth regulatory pathways than intact viral oncogenes. Cells produced by transfection with T155c have variable properties, but some such cell lines seem remarkably stable and have the capacity to develop neuronal properties when differentiated. A previous study (Truckenmiller et al., 2000) showed that at least some cells immortalized with the T155g oncogene, which is related to the T155c used in the present study, exhibit neuronal differentiation and are stable during long-term culture. Thus, T155c and T155g may be useful oncogenes for the production of cell lines, which are to be employed for transplantation.

References

- Anton R, Kordower JH, Maidment NT, Manaster JS, Kane DJ, Rabizadeh S, Schueller SB, Yang J, Rabizadeh S, Edwards RH, Markham CH, Bredesen DE. Neural-targeted gene therapy for rodent and primate Hemiparkinsonism. Exp Neurol. 1994;127:207–218. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1994.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bikel I, Mamon H, Brown EL, Boltax J, Agha M, Livingston DM. The T-unique coding domain is important to the transformation maintenance function of the simian virus 40 small t antigen. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:1172–1178. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.4.1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bikel I, Montano X, Agha ME, Brown M, McCormack M, Boltax J, Livingston DM. SV40 small t antigen enhances the transformation activity of limiting concentrations of SV40 large T antigen. Cell. 1987;48:321–330. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90435-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouck N, Beales N, Shenk T, Berg P, di Mayorca G. New region of the simian virus 40 genome required for efficient viral transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978;75:2473–2477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.5.2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky JL, Pipas JM. Polyomavirus T antigens: Molecular chaperones for multiprotein complexes. J Virol. 1998;72:5329–5334. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5329-5334.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan TM, Englezou A, Gupta J, Bacchetti S, Reddel RR. Telomere elongation in immortal human cells without detectable telomerase activity. EMBO J. 1995;14:4240–4248. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00098.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan TM, Reddel RR. SV40-induced immortalization of human cells. Crit Rev Oncog. 1994;5:331–357. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v5.i4.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campisi J. The biology of replicative senescence. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:703–709. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(96)00058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepko CL. Immortalization of neural cells via retrovirus-mediated oncogene transduction. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1989;12:47–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.12.030189.000403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepko CL. Transduction of genes using retrovirus vectors. In: Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K, editors. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Wiley; New York: 1992. (9.10) 1–9, (14.3) [Google Scholar]

- Conzen SD, Cole CN. The three transforming regions of SV40 T antigen are required for immortalization of primary mouse embryo fibroblasts. Oncogene. 1995;11:2295–2302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCaprio JA. The role of the J domain of SV40 large T in cellular transformation. Biologicals. 1999;27:23–28. doi: 10.1006/biol.1998.0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCaprio JA, Ludlow JW, Figge J, Shew JY, Huang CM, Lee WH, Marsilio E, Paucha E, Livingston DM. SV40 large tumor antigen forms a specific complex with the product of the retinoblastoma susceptibility gene. Cell. 1988;54:275–283. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90559-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon-Carter O, Johnston RE, Borlongan CV, Truckenmiller ME, Coggiano M, Freed WJ. T155g-immortalized kidney cells produce growth factors and reduce sequelae of cerebral ischemia. Cell Transplant. 2002;11:251–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckner R, Ludlow JW, Lill NL, Oldread E, Arany Z, Modjtahedi N, DeCaprio JA, Livingston DM, Morgan JA. Association of P300 and CBP with simian virus 40 large t antigen. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3454–3464. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.7.3454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanning E. Simian virus 40 large t antigen: the puzzle, the pieces, and the emerging picture. J Virol. 1992;66:1289–1293. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1289-1293.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freed WJ. Neural Transplantation: An Introduction. MIT Press; Cambridge: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Frost JA, Alberts AS, Sontag E, Guan K, Mumby MC, Feramisco JR. Simian virus 40 small t antigen cooperates with mitogen-activated kinases to stimulate AP-1 activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:6244–6252. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.6244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller HM, Dubois-Dalcq M. Antigenic and functional characterization of a rat central nervous system-derived cell line immortalized by a retroviral vector. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:1977–1986. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.5.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano M, Takashima H, Poltorak M, Geller HM, Freed WJ. Constitutive expression of glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) by striatal cell lines immortalized using the tsa58 allele of the SV40 large T antigen. Cell Transplant. 1996;5:563–575. doi: 10.1177/096368979600500506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girardi AJ, Weinstein D, Moorhead PS. SV40 Transformation of human diploid cells. A parallel study of viral and karyologic parameters. Ann Med Exp Biol Fenn. 1966;44:242–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjoerup O, Chao H, DeCaprio JA, Roberts TM. PRB-dependent, J domain-independent function of simian virus 40 large T Antigen in override of P53 growth suppression. J Virol. 2000;74:864–874. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.2.864-874.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golubovskaya VM, Filatov LV, Behe CI, Presnell SC, Hooth MJ, Smith GJ, Kaufmann WK. Telomere shortening, telomerase expression, and chromosome instability in rat hepatic epithelial stem-like cells. Mol Carcinog. 1999;24:209–217. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2744(199903)24:3<209::aid-mc7>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA, Grigoryan G, Virley D, Patel S, Sinden JD, Hodges H. Conditionally immortalized, multipotential and multifunctional neural stem cell lines as an approach to clinical transplantation. Cell Transplant. 2000;9:153–168. doi: 10.1177/096368970000900203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greider CW, Blackburn EH. Identification of a specific telomere terminal transferase activity in tetrahymena extracts. Cell. 1985;43:405–413. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbour JW, Dean DC. Rb function in cell-cycle regulation and apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:E65–E67. doi: 10.1038/35008695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulla JE, Schneider RP. Structure of the rat P53 tumor suppressor gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:713–717. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.3.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isono M, Geller HM, Poltorak M, Freed WJ. Intracerebral transplantation of the A1 immortalized astrocytic cell line. Res Neurol Neurosci. 1992;4:301–310. doi: 10.3233/RNN-1992-4501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jog P, Joshi B, Dhamankar V, Imperiale MJ, Rutila J, Rundell K. Mutational analysis of simian virus 40 small-t antigen. J Virol. 1990;64:2895–2900. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.6.2895-2900.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamijo T, Zindy F, Roussel MF, Quelle DE, Downing JR, Ashmun RA, Grosveld G, Sherr CJ. Tumor suppression at the mouse INK4a locus mediated by the alternative reading frame product P19ARF. Cell. 1997;91:649–659. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80452-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley WL. The J-domain family and the recruitment of chaperone power. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:222–227. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01215-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kierstead TD, Tevethia MJ. Association of P53 binding and immortalization of primary C57BL/6 mouse embryo fibroblasts by using simian virus 40 t-antigen mutants bearing internal overlapping deletion mutations. J Virol. 1993;67:1817–1829. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.1817-1829.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Roth KA, Coopersmith CM, Pipas JM, Gordon JI. Expression of wild-type and mutant simian virus 40 large tumor antigens in villus-associated enterocytes of transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:6914–6918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.6914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, You S, Kim IJ, Foster LK, Farris J, Ambady S, Ponce de Leon FA, Foster DN. Alterations in P53 and E2F-1 function common to immortalized chicken embryo fibroblasts. Oncogene. 2001a;20:2671–2682. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HY, Ahn BY, Cho Y. Structural basis for the inactivation of retinoblastoma tumor suppressor by SV40 large t antigen. EMBO J. 2001b;20:295–304. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.1.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipling D. Telomere structure and telomerase expression during mouse development and tumorigenesis. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:792–800. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(97)00060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane DP, Crawford LV. T antigen is bound to a host protein in SV40-transformed cells. Nature. 1979;278:261–263. doi: 10.1038/278261a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy MZ, Allsopp RC, Futcher AB, Greider CW, Harley CB. Telomere end-replication problem and cell aging. J Mol Biol. 1992;225:951–960. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90096-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linzer DI, Levine AJ. Characterization of a 54K dalton cellular SV40 tumor antigen present in SV40-transformed cells and uninfected embryonal carcinoma cells. Cell. 1979;17:43–52. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90293-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg C, Englund U, Trono D, Bjorklund A, Wictorin K. Differentiation of the RN33B cell line into forebrain projection neurons after transplantation into the neonatal rat brain. Exp Neurol. 2002;175:370–387. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maclean K, Rogan EM, Whitaker NJ, Chang AC, Rowe PB, Dalla-Pozza L, Symonds G, Reddel RR. In vitro transformation of li-fraumeni syndrome fibroblasts by SV40 large t antigen mutants. Oncogene. 1994;9:719–725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin RG, Chou JY. Simian virus 40 functions required for the establishment and maintenance of malignant transformation. J Virol. 1975;15:599–612. doi: 10.1128/jvi.15.3.599-612.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez J, Georgoff I, Levine AJ. Cellular localization and cell cycle regulation by a temperature-sensitive P53 protein. Genes Dev. 1991;5:151–159. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson MJ. Directed mutagenesis, a practical approach. In: Horton RM, editor. Recombination and Mutagenesis of DNA Sequences Using PCR. Oxford Univ. Press; New York: 1991. pp. 217–246. [Google Scholar]

- Michalovitz D, Halevy O, Oren M. Conditional inhibition of transformation and of cell proliferation by a temperature-sensitive mutant of P53. Cell. 1990;62:671–680. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90113-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak MA, Komarova NL, Sengupta A, Jallepalli PV, Shih IM, Vogelstein B, Lengauer C. The role of chromosomal instability in tumor initiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16226–16231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202617399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okoye GS, Freed WJ, Geller HM. Short-term immunosuppression enhances the survival of intracerebral grafts of A7-immortalized glial cells. Exp Neurol. 1994;128:191–201. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1994.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okoye GS, Powell EM, Geller HM. Migration of A7 immortalized astrocytic cells grafted into the adult rat striatum. J Comp Neurol. 1995;362:524–534. doi: 10.1002/cne.903620407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallas DC, Shahrik LK, Martin BL, Jaspers S, Miller TB, Brautigan DL, Roberts TM. Polyoma small and middle T antigens and SV40 small t antigen form stable complexes with protein phosphatase 2A. Cell. 1990;60:167–176. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90726-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paucha E, Mellor A, Harvey R, Smith AE, Hewick RM, Waterfield MD. Large and small tumor antigens from simian virus 40 have identical amino termini mapping at 0.65 map units. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978;75:2165–2169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.5.2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz J, Schreiber-Agus N, Liegeois NJ, Silverman A, Alland L, Chin L, Potes J, Chen K, Orlow I, Lee HW, Cordon-Cardo C, DePinho RA. The Ink4a tumor suppressor gene product, P19Arf, interacts with mdm2 and neutralizes mdm2's inhibition of P53. Cell. 1998;92:713–723. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81400-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porras A, Gaillard S, Rundell K. The simian virus 40 small-t and large-t antigens jointly regulate cell cycle reentry in human fibroblasts. J Virol. 1999;73:3102–3107. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.3102-3107.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quartin RS, Cole CN, Pipas JM, Levine AJ. The amino-terminal functions of the simian virus 40 large t antigen are required to overcome wild-type P53-mediated growth arrest of cells. J Virol. 1994;68:1334–1341. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1334-1341.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renfranz PJ, Cunningham MG, McKay RD. Region-specific differentiation of the hippocampal stem cell line HiB5 upon implantation into the developing mammalian brain. Cell. 1991;66:713–729. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90116-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin H, Figge J, Bladon MT, Chen LB, Ellman M, Bikel I, Farrell M, Livingston DM. Role of small t antigen in the acute transforming activity of SV40. Cell. 1982;30:469–480. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90244-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarnow P, Ho YS, Williams J, Levine AJ. Adenovirus Elb-58kd tumor antigen and SV40 large tumor antigen are physically associated with the same 54 Kd cellular protein in transformed cells. Cell. 1982;28:387–394. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90356-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr CJ, DePinho RA. Cellular senescence: Mitotic clock or culture shock? Cell. 2000;102:407–410. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder EF. Retroviral vectors for the study of neuroembryology: immortalization of neural cells. In: Kaplit MG, Loewy AD, editors. Viral Vectors: Tools for Analysis and Genetic Manipulation of the Nervous System. Academic Press; New York: 1995. pp. 435–475. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan A, McClellan AJ, Vartikar J, Marks I, Cantalupo P, Li Y, Whyte P, Rundell K, Brodsky JL, Pipas JM. The amino-terminal transforming region of simian virus 40 large t and small t antigens functions as a J domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4761–4773. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubdal H, Zalvide J, DeCaprio JA. Simian virus 40 large T antigen alters the phosphorylation state of the RB-related proteins P130 and P107. J Virol. 1996;70:2781–2788. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.2781-2788.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tevethia MJ, Pipas JM, Kierstead T, Cole C. Requirements for immortalization of primary mouse embryo fibroblasts probed with mutants bearing deletions in the 3' end of SV40 gene A. Virology. 1988;162:76–89. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90396-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson DL, Kalderon D, Smith AE, Tevethia MJ. Dissociation of Rb-binding and anchorage-independent growth from immortalization and tumorigenicity using SV40 mutants producing n-terminally truncated large T antigens. Virology. 1990;178:15–34. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90375-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tooze J. DNA Tumor Viruses, Part 2: Molecular Biology of Tumor Viruses. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Truckenmiller ME, Tornatore C, Wright RD, Dillon-Carter O, Meiners S, Geller HM, Freed WJ. A truncated SV40 large T antigen lacking the P53 binding domain overcomes P53-induced growth arrest and immortalizes primary mesencephalic cells. Cell Tissue Res. 1998;291:175–189. doi: 10.1007/s004410050989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truckenmiller ME, Zhang P, Conejero C, Vawter MP, Cheadle C, Becker K, Dillon-Carter O, Freed WJ. Characteristics of rat cell lines produced with T155, a truncated SV40 large T polypeptide. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 2000;26 (1):1101. [Google Scholar]

- Truckenmiller ME, Vawter MP, Zhang P, Conejero-Goldberg C, Dillon-Carter O, Morales N, Cheadle C, Becker KG, Freed WJ. AF5, a CNS cell line immortalized with an N-terminal fragment of SV40 large T: growth, differentiation, genetic stability and gene expression. Exp Neurol. 2002;175:318–337. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vancutsem PM, Lazarus P, Williams GM. Frequent and specific mutations of the rat P53 gene in hepatocarcinomas induced by tamoxifen. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3864–3867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WB, Bikel I, Marsilio E, Newsome D, Livingston DM. Transrepression of RNA polymerase II promoters by the simian virus 40 small t antigen. J Virol. 1994;68:6180–6187. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6180-6187.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe G, Howe A, Lee RJ, Albanese C, Shu IW, Karnezis AN, Zon L, Kyriakis J, Rundell K, Pestell RG. Induction of cyclin d1 by simian virus 40 small tumor antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:12861–12866. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.12861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellinger RJ, Sen D. The DNA structures at the ends of eukaryotic chromosomes. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:735–749. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(97)00067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalen B, Laffin J, Friedrich TD, Lehman JM. SV40 small t antigen enhances progression to >G2 during lytic infection. Exp Cell Res. 1999;251:121–127. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore SR, Onifer SM. Immortalized neural cell lines for CNS transplantation. Prog Brain Res. 2000;127:49–65. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(00)27005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynford-Thomas D. Proliferative lifespan checkpoints: cell-type specificity and influence on tumour biology. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:716–726. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(97)00064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SI, Lickteig RL, Estes R, Rundell K, Walter G, Mumby MC. Control of protein phosphatase 2A by simian virus 40 small-t antigen. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:1988–1995. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.4.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalvide J, Stubdal H, DeCaprio JA. The J domain of simian virus 40 large t antigen is required to functionally inactivate RB family proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1408–1415. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.3.1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zindy F, Eischen CM, Randle DH, Kamijo T, Cleveland JL, Sherr CJ, Roussel MF. Myc signaling via the ARF tumor suppressor regulates P53-dependent apoptosis and immortalization. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2424–2433. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.15.2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]