Abstract

Increased mitotic recombination enhances the risk for loss of heterozygosity, which contributes to the generation of cancer in humans. Defective DNA replication can result in elevated levels of recombination as well as mutagenesis and chromosome loss. In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a null allele of the RAD27 gene, which encodes a structure-specific nuclease involved in Okazaki fragment processing, stimulates mutation and homologous recombination. Similarly, rad3-102, an allele of the gene RAD3, which encodes an essential helicase subunit of the core TFIIH transcription initiation and DNA repairosome complexes confers a hyper-recombinagenic and hypermutagenic phenotype. Combining the rad27 null allele with rad3-102 dramatically stimulated interhomolog recombination and chromosome loss but did not affect unequal sister-chromatid recombination, direct-repeat recombination, or mutation. Interestingly, the percentage of cells with Rad52-YFP foci also increased in the double-mutant haploids, suggesting that rad3-102 may increase lesions that elicit a response by the recombination machinery or, alternatively, stabilize recombinagenic lesions generated by DNA replication failure. This net increase in lesions led to a synthetic growth defect in haploids that is relieved in diploids, consistent with rad3-102 stimulating the generation and rescue of collapsed replication forks by recombination between homologs.

GENOMIC integrity and, ultimately, cell survival rely on the coordinated and accurate responses of various damage repair systems to insults incurred by the DNA. In their absence, chromosomal instability, a hallmark of tumor cells, is markedly increased (Mitelman et al. 1994; Radford et al. 1995; Gupta et al. 1997; Lengauer et al. 1998; Gray and Collins 2000; Bishop and Schiestl 2001; Feitelson et al. 2002; Kamb 2003; Lin et al. 2003; Rajagopalan and Lengauer 2004). Homologous recombination (HR) is a repair mechanism that is critical for repairing double-strand breaks (DSBs) created by DNA replication failure, ionizing radiation, and other damaging agents (Game and Mortimer 1974; Resnick 1976; Resnick and Martin 1976; Tishkoff et al. 1997; Symington 1998; Paques and Haber 1999; Cox et al. 2000; Debrauwere et al. 2001; Galli et al. 2003; Michel et al. 2004). Many of the genes involved in HR, such as RAD50, RAD51, RAD52, RAD53, RAD54, RAD55, RAD56, RAD57, RAD59, RDH54/TID1, MRE11, and XRS2 (NBS1 in humans), were first identified through mutants sensitive to ionizing radiation (Game and Mortimer 1974). The HR proteins physically interact with and process DSBs to facilitate their repair (Paques and Haber 1999; Sugawara et al. 2003; Krogh and Symington 2004).

Repair by HR requires an initiating event, such as a DSB (Resnick 1976; Resnick and Martin 1976; Szostak et al. 1983; Paques and Haber 1999), and a homologous donor sequence carrying sufficient genetic information to repair the break (Rubnitz and Subramani 1984; Bailis and Rothstein 1990; Sugawara and Haber 1992; Jinks-Robertson et al. 1993). The donor sequences most commonly used to repair DSBs are homologous sequences on the sister-chromatid or homologous chromosome. However, increased mitotic recombination with a homologous chromosome or nonallelic, ectopic sequences increases the risk for deleterious genome rearrangements or loss of heterozygosity (LOH) and paves the road for carcinogenesis or other diseases (Gupta et al. 1997; Bishop and Schiestl 2001). Several studies have demonstrated that the development of many cancers involves the loss or gain of information by interhomolog recombination mechanisms such as gene conversion and break-induced replication (Bishop and Schiestl 2001). For example, one study reported that 81.3% of colorectal adenocarcinomas exhibited LOH (Lin et al. 2003), while, in another study, up to 37.5% of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast displayed LOH (Radford et al. 1995).

Identifying the factors that stimulate interhomolog recombination may provide insight into the molecular mechanisms that promote LOH and cell transformation. Defects in DNA replication proteins such as Dna2, Pol δ, and Rad27 stimulate mitotic recombination (Symington 1998; Aguilera et al. 2000; Lopes et al. 2002; Michel et al. 2004), perhaps by interfering with DNA replication fork progression. Alternatively, a DNA replication fork may encounter a lesion that blocks leading- or lagging-strand synthesis (Holmes and Haber 1999; Lopes et al. 2006b). Lesions can be bypassed using error-prone mechanisms or through template switching to the sister chromatid. If the lesion persists, leaving a daughter-strand nick or gap (Lopes et al. 2006b), subsequent DNA replication may generate a collapsed fork that resembles a single-ended DSB (Saleh-Gohari et al. 2005; Cortes-Ledesma and Aguilera 2006). Whereas mutagenic bypass and template switching may aid in preventing fork collapse and DSB formation, the requirement for HR to rescue collapsed forks is clearly suggested by the observation that certain DNA replication mutations are lethal in combination with mutations in the HR machinery (Tishkoff et al. 1997; Symington 1998; Debrauwere et al. 2001; Galli et al. 2003; Michel et al. 2004).

In yeast, the RAD27 gene codes for a 5′–3′ flap exo- and endonuclease that processes Okazaki fragments during lagging-strand DNA synthesis and is the homolog to the human FEN-1 protein (Harrington and Lieber 1994; Reagan et al. 1995; Sommers et al. 1995; Lieber 1997). In the rad27-null mutant, all consequences of defective lagging-strand synthesis are observed. For example, rad27-null mutant cells display increased levels of single-stranded DNA (Vallen and Cross 1995; Parenteau and Wellinger 1999), mutagenesis (Tishkoff et al. 1997), microsatellite instability (Schweitzer and Livingston 1998; Xie et al. 2001; Refsland and Livingston 2005), minisatellite instability (Kokoska et al. 1998; Lopes et al. 2006a), telomeric repeat instability (Parenteau and Wellinger 1999), and recombination (Tishkoff et al. 1997; Symington 1998; Negritto et al. 2001). Combining the rad27Δ-null allele with null mutations in a large number of HR genes leads to synthetic lethality, strongly suggesting the need for HR to rescue DNA replication defects in these cells (Tishkoff et al. 1997; Symington 1998; Debrauwere et al. 2001).

Previous studies in yeast showed that certain alleles of the RAD3, SSL1, and SSL2 genes, which encode subunits of the transcription factor IIH (TFIIH) and nucleotide excision repair (NER) complexes, display elevated levels of mitotic recombination (Golin and Esposito 1977; Malone and Hoekstra 1984; Montelone et al. 1988, 1992; Montelone and Liang-Chong 1993; Montelone Bailis et al. 1995; Bailis and Maines 1996; Garfinkel and Bailis 2002). This suggests a role for these DNA repair genes either in preventing the formation of lesions that utilize recombination for repair or in modulating the recombinational response to these lesions. TFIIH and the NER repairosome share seven subunits that include RAD3, SSL1, SSL2, TFB1, TFB2, TFB4, and TFB5 (Svejstrup et al. 1995; Feaver et al. 2000; Takagi et al. 2003; Ranish et al. 2004). TFIIH is required for transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II, while the NER repairosome is required for the repair of UV damage (Feaver et al. 1993; Svejstrup et al. 1995). Both RAD3 and SSL2 code for DNA-dependent ATPase/helicases with opposite polarities and are essential for cell viability (Higgins et al. 1983; Naumovski and Friedberg 1983; Sung et al. 1987; Guzder et al. 1994; Sung et al. 1996). Recently, the Ssl1 subunit has also been shown to possess E3 ubiquitin ligase activity (Takagi et al. 2005). Since Ssl1 and Rad3 interact physically and genetically (Bardwell et al. 1994; Maines et al. 1998), it is possible that this function may be integral to the roles already described for these proteins.

Mutant alleles of the RAD3, SSL1, and SSL2 genes confer several genetically separable phenotypes, indicative of their roles in multiple cellular functions. Consistent with these observations, human homologs of these genes have been linked to the diseases xeroderma pigmentosum, Cockayne's syndrome, and trichothiodystrophy, which are characterized by transcriptional and DNA repair defects and increased tumor formation (Garfinkel and Bailis 2002). While mutations in the yeast RAD3 and SSL1 genes create separable transcription, NER, and recombination phenotypes (Montelone et al. 1988; Song et al. 1990; Feaver et al. 1993; Montelone and Malone 1994; Wang et al. 1995; Maines et al. 1998), it remains unclear how these changes are related.

One RAD3 mutant allele, rad3-102, was identified on the basis of its ability to confer elevated levels of mitotic recombination and mutagenesis (Malone and Hoekstra 1984). The rad3-102 allele contains a point mutation that alters amino acid residue 661 in the seventh conserved domain of the Rad3 helicase (Montelone and Malone 1994). Further, like the rad27-null allele, rad3-102 confers synthetic lethality when combined with mutations in the HR genes RAD52 and RAD50 (Malone and Hoekstra 1984). This may be independent from the transcription initiation and NER function of Rad3 as the rad3-102 mutation does not confer any apparent transcription defect, and only a minor NER defect (Hoekstra and Malone 1987; Malone et al. 1988). In this article, we examine the epistatic interactions between rad3-102 and a null allele of RAD27 to determine if their elevated rates of mutation and recombination are mechanistically related.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and plasmids:

All strains used in this study are isogenic with W303-1A (Thomas and Rothstein 1989) and are shown in Table 1. All yeast strain construction used conventional methods (Burke et al. 2000). The construction of the rad27∷LEU2 allele was described previously (Frank et al. 1998) and the rad3-102 allele was incorporated into yeast from the plasmid pBM3-102 that was a generous gift of Beth Montelone and Robert Malone (Montelone et al. 1988; Montelone and Malone 1994). All strains derived from those containing the rad27∷LEU2 mutation were checked for differences in growth to assure absence of suppressors. The rad27-null mutation confers a slow-germination phenotype that is easily distinguishable from wild-type strains. ABX761, used for the unequal sister-chromatid recombination (USCR) assay, was constructed by transforming XbaI-digested PNN287, the generous gift of Michael Fasullo (Fasullo and Davis 1987), into ABX731-8C (MATa, his3-Δ200) by electroporation. Insertion of the plasmid at the targeted site was verified by Southern blot analysis (M. S. Navarro and A. M. Bailis, unpublished results). Yeast strains containing the hom3-10, lys2-Bgl, and CAN1 alleles were derived from strain RKY2672 from Richard Kolodner (Tishkoff et al. 1997) and backcrossed into our background at least four times. The RAD52-YFP allele was the generous gift of Michael Lisby and Rodney Rothstein (Lisby et al. 2001). Assays were conducted from haploids taken immediately from dissection plates or from diploids constructed from newly dissected spore colonies.

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotypea | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| ABX471-2C | MATα hom3-10 lys2-Bgl CAN1 | This study |

| ABX474-4B | MATα hom3-10 lys2-Bgl CAN1 rad27∷LEU2 | This study |

| ABX460-6A | MATahom3-10 lys2-Bgl, CAN1 rad3-102 | This study |

| ABX481-1C | MATα hom3-10 lys2-Bgl CAN1 rad27∷LEU2 rad3-102 | This study |

| ABX761 | MATa/α CAN1/can1-100 his3-Δ200/HIS3 trp1-1/trp1-1∷his3-Δ3′∷his3-Δ5′∷URA3 rad3-102/RAD3 rad27∷LEU2/RAD27 | This study |

| ABX1465 | MATa/α his3∷URA3∷his3/HIS3 rad3-102/RAD3 | This study |

| ABX1368 | MATa/α his3Δ-200/his3∷URA3∷his3 TRP1/trp1-1 rad27∷LEU2/RAD27 | This study |

| ABX1308 | MATa/α CAN1/can1-100 his3Δ-200/his3∷URA3∷his3 rad27∷LEU2/RAD27 rad3-102/RAD3 | This study |

| ABX633 | MATa/α can1-100/CAN1 hom3-10/HOM3 HIS3/his3-11, 15, trp1-1/TRP1, URA3/ura3-1 LYS2/lys2Δ-Bgl | This study |

| ABX647 | MATa/α can1-100/CAN1 HOM3/hom3-10 HIS3/his3∷ura3∷LEU2 TRP1/trp1-1 rad3-102/rad3-102 | This study |

| ABX658 | MATa/α can1-100/CAN1 HOM3/hom3-10 TRP1/trp1-1 his3∷URA3∷his3/HIS3 rad27∷LEU2/rad27∷LEU2 | This study |

| ABX693 | MATa/α can1-100/CAN1 HOM3/hom3-10 ura3-1/URA3 LYS2/lys2ΔBgl rad3-102/rad3-102 rad27∷LEU2/rad27∷LEU2 | This study |

| ABX861 | MATa/α ADE2/ade2-1 his3∷URA3∷his3/HIS3 rad3-102/RAD3 rad27∷LEU2/RAD27 RAD52/RAD52-YFP | This study |

| W961-5A | MATaHIS3 | John McDonald |

| ABX362-14C | MATarad3-102 | This study |

| ABX217-3C | MATaHIS3 rad27∷LEU2 | This study |

| ABX397-3A | MATarad3-102 rad27∷leu2∷hisG | This study |

| ABX447 | MATa/α leu2-3, 112 RAD27/rad27∷LEU2 | This study |

| ABX430 | MATa/α rad3-102/rad3-G595R | This study |

| ABX1869 | MATa/α ADE2/ade2-1, CAN1/can1-100, his3-11, 17/HIS3, TRP1/trp1-1, leu2-3, 112 rad27∷LEU2/RAD27 RAD3/rad3-102 | This study |

| ABT576 | MATα, LEU2, pRS416 (URA3) | This study |

| ABT577 | MATα, LEU2, pJM3 (MATa, URA3) | This study |

| ABT581 | MATα, HIS3, rad27∷LEU2, rad3-102, pRS416 (URA3) | This study |

| ABT582 | MATα, HIS3, TRP1, rad27∷LEU2, rad3-102, pJM3 (MATa, URA3) | This study |

| ABX1358 | MATa/α his3∷URA3∷his3/his3-Δ200, TRP1/trp1-1 | This study |

| ABX1369 | MATa/α his3∷URA3∷his3/his3-Δ200, TRP1/trp1-1, rad3-102/rad3-102 | This study |

| ABX1362 | MATa/α his3∷URA3∷his3/his3-Δ200, TRP1/trp1-1, rad27∷LEU2/rad27∷LEU2 | This study |

| ABX2010 | MATa/α his3∷URA3∷his3/his3-Δ200, TRP1/trp1-1, rad27∷LEU2/rad27∷LEU2, rad3-102/rad3-102 | This study |

| ABX1498 | MATa/α can1-100/CAN1, hom3-10/HOM3, ura3∷KANMX/ura3∷KANMX, HXT13/hxt13∷URA3 | This study |

| ABX1204 | MATa/α can1-100/CAN1, hom3-10/HOM3, ura3∷KANMX/ura3∷KANMX, HXT13/hxt13∷URA3, rad3-102/rad3-102 | This study |

| ABX1175 | MATa/α can1-100/CAN1, hom3-10/HOM3, ura3∷KANMX/ura3∷KANMX, HXT13/hxt13∷URA3, rad51∷LEU2/rad51∷LEU2 | This study |

| ABX1611 | MATa/α can1-100/CAN1, hom3-10/HOM3, HIS3/HIS3, ura3∷KANMX/ura3∷KANMX, HXT13/hxt13∷URA3, rad51∷LEU2/rad51∷LEU2, rad3-102/rad3-102 | This study |

All strains were isogenic to W303-1A (MATa ade2-1 can1-100 his3-11,17 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 rad5-G535R) (Thomas and Rothstein 1989). Only deviations from this genotype are listed.

The impact of the rad5-G535R allele on growth, mutation, recombination, and chromosome loss was shown to be minimal and did not change the effects exerted by the rad3-102 or rad27-null alleles singly or in combination (M. S. Navarro and A. M. Bailis, unpublished results).

Centromere-containing plasmid pRS416 (Christiansen et al. 1991), which contains the URA3 gene, and pJM3, which contains the URA3 and MATa genes, were generously provided by Phil Hieter and Jim Haber.

Determination of mutation rates:

The lys2-Bgl, hom3-10, and CAN1 mutation rates for ABX471-2C (wild type), ABX474-4B (rad27), ABX460-6A (rad3-102), and ABX481-1C (rad27Δ rad3-102) were determined as described previously (Tishkoff et al. 1997). Strains were plated on YPD (2% peptone, 1% yeast extract, 2% dextrose) for single colonies at 30°. For each genotype, seven individual colonies from at least five strains were excised from plates and individually suspended in sterile water. Appropriate dilutions were plated onto YPD to determine the total number of viable cells, onto synthetic medium lacking lysine to determine the number of lysine prototrophic (Lys+) cells per colony, onto synthetic medium lacking threonine to determine the number of threonine prototrophic (Thr+) cells per colony, and onto synthetic medium without arginine plus 60 μg/ml of canavanine to determine the number of canavanine resistant (Canr) cells per colony. Individual rates were calculated using the method of the median (Lea and Coulson 1949) and are expressed as the number of mutation events/cell/generation. Confidence intervals of 95% were determined by a previously described method (Spell and Jinks-Robertson 2004). A minimum of 30 cultures were tested per strain.

Determination of unequal sister-chromatid recombination rates:

The rates of unequal sister-chromatid recombination were determined as previously described (Fasullo and Davis 1987). At least five freshly dissected ABX761 segregants (of each genotype) containing the USCR construct and the his3-Δ200 allele were streaked out for single colonies on YPD. After 3 days of growth at 30°, at least three single colonies were excised from each plate and suspended in sterile water. Appropriate dilutions were plated onto YPD to determine the total number of viable cells and synthetic complete medium lacking histidine to determine the number of His+ cells per colony. After growth at 30° for 3–4 days, the number of His+ events was determined. Unequal sister-chromatid recombination rates and 95% confidence intervals were calculated from a minimum of 15 trials as described above.

Determination of direct-repeat recombination rates:

The direct-repeat assay was performed as described previously (Maines et al. 1998). Two truncated HIS3 sequences, sharing 415 bp of homology, flank a URA3 marker at the HIS3 locus on chromosome XV. Recombination between the duplicate sequences results in deletion of the URA3 marker and generation of a wild-type HIS3 allele. At least 15 freshly dissected segregants containing the direct repeat were grown to saturation in synthetic medium lacking uracil at 30°. Appropriate dilutions of cells were plated onto YPD medium to determine the number of viable cells and onto synthetic complete medium lacking histidine to determine the number of His+ recombinants. Plates were incubated at 30° for 4 days. Deletion rates and 95% confidence intervals were calculated from a minimum of 15 trials as described above.

Determination of chromosome V loss and interhomolog recombination rates:

The rates of interhomolog recombination (IHR) and chromosome V loss were determined as described previously (Klein 2001). Freshly dissected segregants containing either CAN1 and HOM3 or can1-100 and hom3-10 alleles were crossed to generate CAN1/can1-100, HOM3/hom3-10 diploid strains. At least five independent diploids of each genotype were prepared. Seven fresh colonies of each diploid were dispersed in sterile water. Appropriate dilutions of cells were plated onto YPD medium to determine the total number of viable cells and onto synthetic medium lacking arginine and containing 60 μg/ml of canavanine to determine the number of Canr colonies. The total number of Canr colonies was determined after growth at 30° for 4 days. Canr colonies were replica plated onto synthetic medium lacking threonine. After 2 days of growth at 30°, the fractions of colonies that were Canr Thr+ and Canr Thr− were determined. Cells that were Canr Thr− were scored as chromosome loss events and cells that were Canr Thr+ were scored as interhomolog recombination events. Canr Thr+ colonies may also represent mutation events; however, it was found that Canr Thr+ colonies result predominantly from mitotic recombination (Golin and Esposito 1977). Rates and 95% confidence intervals were determined from a minimum of 35 trials as described above.

To distinguish break-induced replication events from gene conversion events among interhomolog recombination events, we inserted the URA3 marker within the telomere proximal hxt13 locus on chromosome V as previously described (Chen and Kolodner 1999). For the assay, the hxt13∷URA3 allele is on the same copy of chromosome V copy that contains the wild-type HOM3 and CAN1 alleles. Appropriate dilutions of diploid cells were plated onto YPD medium and onto synthetic medium lacking arginine and containing canavanine to determine the number of Canr colonies. The total number of Canr colonies was determined after growth at 30° for 4 days. Canr colonies were replica plated onto synthetic medium lacking threonine and onto synthetic medium lacking uracil. After 2 days of growth at 30°, the fractions of colonies that were Canr Thr+ Ura+ were scored as gene conversion events, cells that were Canr Thr+ Ura− were scored as break-induced replication events, and cells that were Canr Thr− Ura− were scored as chromosome loss events. It is important to note that we were unable to distinguish between break-induced replication (BIR) and crossover events with this assay.

Fluorescence microscopy:

All experiments were performed according to previously described methods (Lisby et al. 2001). In brief, 5 ml of cells were grown in complete synthetic medium to an OD600 of 0.2 at room temperature. Growth at room temperature is required to allow the chromophore to form efficiently (Lim et al. 1995). One milliliter of cells was then washed and resuspended in 200–300 μl of complete synthetic medium. A small aliquot of cells was placed on a glass slide and sealed with VALAP solution (a combination of equal volumes of petroleum jelly, lanolin, and paraffin). Cells were visualized using an Olympus (Melville, NY) AX70 automated upright microscope containing a mercury illumination source and a U-MWIBA filter cube (excitation 460–490 nm) for visualizing Rad52-YFP. Ten live cell images were taken at 0.1-μm intervals along a z-axis, using a Spot RT slider high-resolution B/W camera and a Plan/Apochromat 60x, 1.4 numerical aperture lens, and prepared using the Image Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD) and Image J software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Brightfield images were used to count total cell number and define cell-cycle phase, and each z-stack fluorescence image was inspected for the presence of a Rad52-YFP focus.

Determination of doubling time:

YPD liquid (5 ml) was inoculated with a single colony and grown overnight at 30°. Aliquots from each wild-type, rad3-102, rad27-null, and rad3-102 rad27-null culture were used to inoculate 5 ml of YPD to a cell density of ∼1 × 107 cells/ml and grown at 30°. Culture density was measured each hour by monitoring turbidity using a Klett–Summerson colorimeter fitted with a red filter. Doubling times were calculated using a common algorithm (Singleton 1995). Growth assays with strains containing either pJM3 or pRS416 were done using synthetic complete medium lacking uracil to maintain selection for the plasmids.

RESULTS

Mutagenic response to DNA replication defects is unaltered in the rad3-102 rad27-null double mutant:

The rad27-null mutant confers a defect in lagging-strand synthesis that was previously shown to increase mutagenesis in several mutation assays (Tishkoff et al. 1997). Since the rad3-102 mutant also displays an increased mutation rate (Malone and Hoekstra 1984; Montelone et al. 1992; Montelone and Liang-Chong 1993; Montelone and Koelliker 1995), we investigated the epistatic relationship between the rad27-null and rad3-102 mutations with respect to mutagenesis. The CAN1 forward mutation assay and the hom3-10 and lys2-Bgl reversion assays previously utilized to characterize the rad27-null mutant were used (Tishkoff et al. 1997). The CAN1 forward mutation rate assay selects for cells made resistant to canavanine (Canr) by mutagenesis of the arginine permease gene (Grenson et al. 1966). The reversion assays select for revertants of either a 4-base insertion in the LYS2 gene (lys2-Bgl) or a +1 T insertion within a run of six T's in the HOM3 gene (hom3-10). Consistent with previous results (Tishkoff et al. 1997), we observed significant increases in mutation rate with all three assays in the rad27-null mutant cells (Table 2): a 16-fold increase in the rate of CAN1 mutation, an 8-fold increase in the rate of hom3-10 reversion, and a 17-fold increase in the rate of lys2-Bgl reversion. rad3-102 cells displayed significantly increased rates with only the hom3-10 (7-fold increased) and lys2-Bgl (8-fold increased) reversion assays. Interestingly, rad3-102 did not alter the mutator effect of the rad27-null mutation, even in the hom3-10 reversion assay where its stimulation is similar to that seen with the rad27-null mutation. These results suggest that the rad3-102 and rad27-null mutations affect the same mutagenic mechanism. To further confirm this conclusion, we determined the spectrum of representative lys2-Bgl reversion mutations from wild-type, rad3-102, rad27-null, and rad3-102 rad27-null double mutants. Sequencing of nucleotides 315–540 of the LYS2 gene from at least 20 independent Lys+ revertants revealed that the mutation spectrum of the rad3-102 rad27-null double mutant was similar to that of the rad27-null single mutant, particularly with regard to the deletion/insertion mutations that are characteristic of rad27-null mutant cells (44 and 36%, respectively). No deletion/insertion mutations appeared in wild-type or rad3-102 Lys+ revertants (L. Bi and A. M. Bailis, unpublished results).

TABLE 2.

Mutation rate analysis in wild-type and mutant strains

| Mutation rate

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | Genotype | Canr (×10−7) | Hom+ (×10−7) | Lys+ (×10−7) |

| ABX471-2C | Wild type | 4.0 (3.8–4.4) | 0.26 (0.21–0.29) | 0.32 (0.27–0.42) |

| ABX460-6A | rad3-102 | 5.7 (4.8–7.5) | 1.9 (1.6–2.6) | 2.6 (1.9–3.2) |

| ABX474-4B | rad27 | 64 (54–88) | 2.2 (1.3–3.0) | 5.3 (3.6–7.6) |

| ABX481-1C | rad3-102 rad27 | 69 (47–85) | 1.7 (0.85–2.0) | 4.0 (2.9–4.8) |

All rates were determined from a minimum of 30 trials as described in materials and methods; 95% confidence intervals are indicated in parentheses.

Unequal sister-chromatid and direct-repeat recombination are unaffected by the rad3-102 allele in the rad3-102 rad27-null double mutants:

Template switching with the sister chromatid is another response to replication lesions (Dong and Fasullo 2003). Consequently, we investigated the epistatic relationship between the rad3-102 and rad27-null mutations with respect to USCR using an assay developed by Fasullo and Davis (1987). The assay monitors the frequency of recombination between 3′ and 5′ truncated copies of the HIS3 gene that share 300 bp of homologous sequence and are arranged tail to head at the TRP1 locus on chromosome IV. This arrangement restricts the production of a functional HIS3 gene until S-phase. The rate of USCR in the rad27-null single mutant was 48-fold over the wild-type rate and the rad3-102 mutant increased recombination <4-fold over wild type (Table 3). USCR in the rad3-102 rad27-null double mutant was not significantly different from the rad27-null single mutant.

TABLE 3.

Recombination and chromosome loss rates in wild-type and mutant strains

| Haploid

|

Diploid

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relevant genotype | USCRa (×10−6) | DRRa (×10−5) | IHRb (×10−5) | CLb (×10−6) | DRRc (×10−5) |

| Wild type | 1 (0.8–1.2) | 6.6 (5.5–7.8) | 1.4 (1.2–1.5) | 1.8 (1.4–2.5) | 1.5 (1.2–2.7) |

| rad3-102 | 3.3 (1.3–5.6) | 12 (11–13) | 9.2 (8.3–11) | 2.6 (1.4–4.2) | 6.4 (4.9–18) |

| rad27 | 46 (26–61) | 44 (32–59) | 100 (90–120) | 52 (33–67) | 41 (33–56) |

| rad3-102 rad27 | 79 (54–107) | 84 (32–220) | 2000 (190–4000) | 310 (149–612) | 67 (44–120) |

USCR and direct-repeat recombination (DRR) rates were determined from a minimum of 15 trials as described in materials and methods using haploids dissected from ABX761, ABX1308, ABX1368, and ABX1465; 95% confidence intervals are indicated in parentheses.

IHR and chromosome loss (CL) rates were determined from a minimum of 35 trials as described in materials and methods using diploids ABX633, ABX647, ABX658, and ABX693.

DRR rates were determined from a minimum of seven trials as described in materials and methods using diploids ABX1358, ABX1369, ABX1362, and ABX2010.

Unlike USCR, deletion formation by recombination between nontandem direct repeats on a chromosome can occur before or after the initiation of replication. We determined the rates of recombination between 3′ and 5′ truncated copies of the HIS3 gene that share 415 bp of homology and flank a URA3 selectable marker in haploid and diploid cells (Maines et al. 1998). The rates of direct-repeat recombination in haploid cells were increased sevenfold in the rad27-null mutant and only twofold in the rad3-102 mutant (Table 3). Like USCR, the direct-repeat recombination rate in double-mutant haploids was not significantly different from the rate in rad27-null single mutants, although the possible presence of the additive effects of combining the rad3-102 and rad27-null alleles cannot be dismissed. Very similar effects were observed in diploids, suggesting that the presence of a homolog does not affect the mechanism of recombination. These results indicate that the rad27-null and rad3-102 mutations may affect both recombinagenic responses to replication lesions by similar mechanisms.

Together, the rad3-102 and rad27-null mutations confer synergistic increases in chromosome loss and recombination between homologs:

Chromosome loss and recombination between homologs have previously been shown to be stimulated in DNA replication mutant cells (Haber 1999), presumably in response to lesions generated during DNA replication. In particular, daughter-strand nicks or gaps that are not repaired by error-prone bypass or template switching with the sister chromatid may persist to form collapsed replication forks that can stimulate chromosome loss and recombination with the homolog in diploid cells (Daigaku et al. 2006). Since these may be important consequences of DNA replication lesion formation, we examined the epistatic interactions between rad3-102 and the rad27-null allele with respect to chromosome loss and interhomolog recombination. Using a previously described assay for measuring the loss of one copy of chromosome V and recombination between chromosome V homologs (Klein 2001), we observed wild-type levels of chromosome loss and a sevenfold increase in interhomolog recombination in rad3-102/rad3-102 homozygotes and a 29-fold increase in chromosome loss and a 71-fold increase in interhomolog recombination in the rad27-null/rad27-null homozygotes (Table 3). However, in contrast to the previous assays, the combination of the rad3-102 and rad27-null alleles led to synergistically increased rates of chromosome loss and interhomolog recombination: a 172-fold increase in chromosome loss and a 1400-fold increase in interhomolog recombination in the rad3-102/rad3-102 rad27-null/rad27-null double homozygotes. These results suggest that DNA replication fork collapse is greatly stimulated in rad3-102 rad27-null mutants.

The rad3-102 and rad27-null mutations together increase the percentage of G2/M-phase cells with Rad52-YFP foci:

Previously, Lisby et al. (2001, 2003, 2004) tagged the yeast Rad52 homologous recombination protein with the yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) (Ormö et al. 1996) and observed that it forms nuclear foci in response to DNA damage induced by ionizing radiation, DSB formation by the HO endonuclease, and collapsed replication forks. If, as suggested by the chromosome loss and interhomolog recombination data, the rad3-102 and rad27-null alleles together lead to synergistic increases in replication fork collapse, more rad3-102 rad27-null double-mutant cells might be expected to display foci than rad3-102 and rad27-null single mutant cells. As observed previously, we found that most wild-type cells exhibited diffuse nuclear fluorescence and that only 6.6% of S-phase and 4.1% of G2/M-phase cells contained one or more foci in an asynchronous population (Table 4) (Lisby et al. 2001). Consistent with the levels of recombination observed in rad3-102 and rad27-null mutant cells, 23% of S-phase and 14% of G2/M-phase rad3-102 mutant cells displayed a focus, while 23% of S-phase and 47% of G2/M-phase rad27-null mutant cells displayed foci. As predicted, the rad3-102 rad27-null double mutant exhibited a greater percentage of cells with foci than either of the single mutants, with 47% of S-phase and 68% of G2/M phase cells containing foci.

TABLE 4.

Rad52-YFP focus formation in wild-type and mutant cells

| % cells containing a focus ±2 SEa

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Relevant genotype | S-phase | G2/M-phase |

| Wild type | 6.6 ± 5.3 | 4.1 ± 1.8 |

| rad3-102 | 23 ± 3.8 | 14 ± 1.5 |

| rad27 | 23 ± 7.6 | 47 ± 10 |

| rad3-102 rad27 | 47 ± 8.0 | 68 ± 2.9 |

Percentage of cells containing a focus was measured by dividing the number of cells in S- or G2/M-phase containing one or more foci by the total number of cells in S- or G2/M-phase and is reported as the median percentage ±2 standard errors of at least five trials. Each trial consisted of at least 50 cells.

A profound growth defect in the rad3-102 rad27-null double-mutant haploid is suppressed in the homozygous double-mutant diploid:

The rad3-102 and rad27-null single mutant haploid strains exhibit mild growth defects at 30° (Sommers et al. 1995; Symington 1998) (Table 5). However, combining the rad3-102 and rad27-null alleles synergistically increases doubling time in haploids. Strikingly, the doubling time of the rad3-102/rad3-102 rad27-null/rad27-null double homozygote is very similar to that in the rad27-null/rad27-null single homozygote (Table 5). This result may indicate an effect of diploidy, MAT heterozygosity, or both. MAT heterozygosity has been demonstrated to increase recombination in diploid cells as well as resistance to DNA damage in both haploid and diploid cells (Friis and Roman 1968; Heude and Fabre 1993; Fasullo and Dave 1994; Fasullo et al. 1999). To distinguish whether MAT heterozygosity is solely responsible for rescuing the growth defect of the double-mutant cells, we transformed both wild-type and rad3-102 rad27-null MATα haploids with a plasmid that contains the MATa sequence and repeated the growth assays. As a control, we also transformed wild-type and double-mutant MATα haploids with pRS416 that lacks MAT sequences. MAT heterozygosity did not significantly alter the doubling time of rad3-102 rad27-null double-mutant haploids. This suggests that the presence of a homolog is required to rescue the growth defect imposed by the combination of the rad3-102 and rad27-null alleles, perhaps by permitting chromosome loss or by enabling interhomolog recombination to rescue collapsed forks that otherwise inhibit growth.

TABLE 5.

Doubling times of wild-type and mutant strains

| Relevant genotype | Haploid DT ±2 SE (min) | Diploid DT ±2 SE (min) |

|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 94 ± 3.9 | 95 ± 2.0 |

| Wild type + pRS416 | 102 ± 2.7 | ND |

| Wild type + pJM3 | 96 ± 3.4 | ND |

| rad3-102 | 105 ± 3.9 | 98 ± 3.6 |

| rad27 | 114 ± 8.0 | 130 ± 4.7 |

| rad3-102 rad27 | 175 ± 11 | 130 ± 10 |

| rad3-102 rad27 + pRS416 | 192 ± 11 | ND |

| rad3-102 rad27 + pJM3 | 189 ± 11 | ND |

Doubling times (DT) were determined at 30° as described in materials and methods and are reported as the median doubling time ±2 standard errors in minutes from at least five independent trials.

DISCUSSION

The TFIIH and NER helicase Rad3 has been variously implicated in spontaneous mutagenesis and recombination, as well as in the processing of recombination intermediates (Malone and Hoekstra 1984; Montelone et al. 1988, 1992; Montelone and Liang-Chong 1993; Montelone and Malone 1994; Bailis et al. 1995; Montelone and Koelliker 1995; Bailis and Maines 1996). This article addresses the effect of a known hypermutagenic and hyper-recombinagenic allele, rad3-102, in the context of the defined DNA replication defect conferred by the rad27-null mutation to better understand how Rad3 functions in the development of mutations, genome rearrangements, and LOH. We revealed that two mechanisms that promote LOH, chromosome loss, and interhomolog recombination were synergistically stimulated in the rad3-102 rad27-null double mutant. However, mutation rate and unequal sister-chromatid and direct-repeat recombination, mechanisms that do not rely on the presence of a homologous chromosome, were not stimulated any further in the double mutant than in the rad27-null single mutant. These results suggest that rad3-102 confers a preference for mechanisms that utilize a homolog in the rescue of replication lesions generated in the absence of Rad27. In support of this hypothesis, differential growth of rad3-102 rad27-null haploids and homozygous diploids suggests that these lesions, which we suggest may be collapsed forks, either are efficiently repaired by interhomolog recombination or result in chromosome loss in diploids.

The Rad27 nuclease functions primarily in the removal of the 5′ RNA/DNA flap generated during lagging-strand synthesis (Harrington and Lieber 1994; Reagan et al. 1995; Sommers et al. 1995; Lieber 1997). In its absence, processing by other nucleases may create nicks or gaps in the daughter-strand, which have been observed in rad27-null mutants (Vallen and Cross 1995; Parenteau and Wellinger 1999). These daughter-strand nicks and gaps may be utilized for mutagenic bypass or template switching and give rise to mutations or sister-chromatid exchange events (Fasullo and Davis 1987; Holmes and Haber 1999; Michel et al. 2004; Saleh-Gohari et al. 2005; Lopes et al. 2006b), as observed in our rad27-null mutant (Tables 2 and 3). Persistence of a flap would lead to replication fork collapse upon confrontation with the replicative polymerase during the next cell cycle. Chromosome breaks have been observed in rad27-null mutant cells (Vallen and Cross 1995; Callahan et al. 2003), which could elicit checkpoint signals that lead to arrest in G2, slow growth, and enhanced chromosome loss and interhomolog recombination (Tables 3 and 5; L. Bi and A. M. Bailis, unpublished results). These observations are most consistent with the rad27-null mutation primarily affecting the creation of DNA damage. Previous studies have implicated Rad27 in the processing of recombination intermediates (Wu et al. 1999; Negritto et al. 2001; Kikuchi et al. 2005; Zheng et al. 2005). The results reported here do not support such a conclusion, perhaps, because the effects of increased chromosome breakage on our assays eclipse the effects on the processing of intermediates in rad27-null mutant cells. Substantial increases in all of the consequences of replication lesion formation in the rad27-null mutant cells argues that blocking Okazaki fragment maturation leads to dramatic increases in genome instability.

The role that the Rad3 helicase plays in the maintenance of genome stability is unclear. While the participation of Rad3 in NER and transcription is not inconsistent with the effects of rad3 mutations on mutagenesis and recombination, rad3-102, the hypermutagenic and hyper-recombinagenic mutant described here, displays minimal or no defects in nucleotide excision repair or transcription (Hoekstra and Malone 1987; Montelone et al. 1988). Certain mutations in SSL1, which encodes another core subunit of TFIIH and the NER repairosome, stimulate short-sequence recombination and attenuate the processing of DSBs (Maines et al. 1998). Recently, Ssl1 has also been shown to have ubiquitin ligase activity that may influence its role in genome stability (Hoege et al. 2002). Since RAD3 and SSL1 have been shown to interact genetically (Bardwell et al. 1994; Maines et al. 1998), and Rad3 and Ssl1 to interact physically (Bardwell et al. 1994; Maines et al. 1998), it is possible that rad3-102 influences genome stability through an interaction between Rad3 and Ssl1, but this has yet to be explored.

It was previously suggested that the hyper-recombinagenic effect of rad3-102 resulted from the mutant protein generating lesions in the DNA that ultimately became DSBs (Montelone et al. 1988). This hypothesis was especially attractive since rad3-102, like rad27Δ, is synthetically lethal in mutant rad52 and rad50 backgrounds (Malone and Hoekstra 1984). While the hypermutagenic and hyper-recombinagenic nature of the rad3-102 mutant is reminiscent of the rad27-null mutant, we observed several essential differences. In general, the hypermutagenic and hyper-recombinagenic characteristics of the rad3-102 mutant were significantly less severe than those of the rad27-null mutant. These are reflected by the minimal effects of the rad3-102 allele on cell-cycle profile, Rad52-YFP focus formation, and growth, which are inconsistent with substantial increases in DNA replication lesions (Tables 4 and 5; L. Bi and A. M. Bailis, unpublished results). Therefore, it seems likely that the rad3-102 allele exerts its effect subsequent to the formation of DNA replication lesions. In further support of this hypothesis, we have previously shown that another allele of RAD3, rad3-G595R, has a substantial effect on recombination that has been initiated by an HO-endonuclease-catalyzed DSB, perhaps by changing their exonucleolytic processing (Bailis et al. 1995). Consequently, we suggest that the rad3-102 allele may exacerbate the effect of the rad27-null allele on loss of heterozygosity primarily by altering the cellular response to DNA replication lesions.

The data presented here are consistent with a model for the interaction between the rad27-null and rad3-102 mutant alleles where the loss of Rad27 leads to the accumulation of DNA replication lesions and rad3-102 alters their processing. Loss of Rad27 results in the inefficient cleavage of RNA primer sequences from the 5′-ends of Okazaki fragments, such that at least one RNA residue remains, blocking their ligation to adjacent fragments. Other nucleases remove these 5′-ends, creating daughter-strand nicks and gaps that accumulate in rad27-null mutant cells (Merrill and Holm 1998; Parenteau and Wellinger 1999). The 3′-ends of these gaps may be recognized by polymerases with an increased tendency for mis-insertion that synthesize across the gap in an error-prone manner, contributing to the robust mutation rate in the rad27-null mutants (Table 2). Alternatively, the gaps may be repaired by template switching with the sister chromatid (Zheng and Fasullo 2003) that can also account for the duplications that accumulate in rad27-null mutants (Tishkoff et al. 1997), as well as for the increases in USCR and direct-repeat recombination (Table 3).

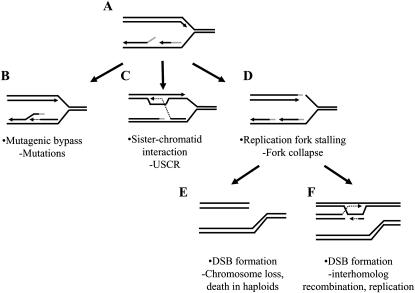

We suggest that rad3-102 may attenuate the removal of the residual RNA primer sequences from Okazaki fragments by blocking nucleases that can compensate for the loss of Rad27 (Symington 1998). This may occur because the NER repairosome, of which Rad3 is a component, may recognize and bind to the primer sequences as it does to other polymerase-blocking lesions (Johansson et al. 2004), limiting nuclease access in rad3-102 mutant cells. Under these circumstances, unprocessed and unligatable Okazaki fragments would be expected to accumulate. An increase in unprocessed Okazaki fragments may lead to widespread DSB formation by DNA replication fork collapse in the subsequent S-phase as the discontinuities would lie on the template for leading-strand synthesis (Figure 1). Alternatively, the nicks may stimulate DSB formation prior to the following S-phase (Tishkoff et al. 1997). The DSBs may be repaired by interhomolog recombination or give rise to chromosome loss that can be tolerated in diploids but may be fatal in haploids. Evidence for this in rad3-102 rad27-null double-mutant haploids exists in the significant increase in the percentage of cells with Rad52-YFP foci (Table 4) and the synthetic growth defect in haploid cells that lack an efficient means of rescuing the collapsed forks (Table 5). However, in rad3-102 rad27-null double-mutant diploids, the presence of a homolog appears to rescue the synthetic growth defect (Table 5), perhaps through the repair of DSBs by interhomolog recombination, which is increased 1400-fold, or through supporting chromosome loss, which is stimulated 172-fold (Table 3). Interestingly, the presence of a homolog failed to stimulate direct-repeat recombination in the rad3-102 rad27-null double-mutant diploids beyond that observed in the rad27-null single-mutant haploids, and these rates were not significantly different from those observed in rad27-null and rad3-102 rad27-null haploids (Table 3). This is consistent with fork collapse leading to the formation of single-ended DSBs that are thought to be ideal substrates for interhomolog recombination by BIR (McEachern and Haber 2006), but not, perhaps, direct-repeat recombination, which is thought to occur by single-strand annealing (Lin et al. 1990; Ivanov et al. 1996; Dong and Fasullo 2003; Davis and Symington 2004).

Figure 1.—

Model of the consequences of DNA replication fork failure in rad27-null mutant cells. (A) During DNA replication, the 5′ RNA/DNA flaps (shaded line) of Okazaki fragments generated on the lagging strand are inefficiently processed in the rad27-null mutant. (B) The 5′ RNA/DNA flap may be displaced by mutagenic polymerases and later cleaved by other endo-/exonucleases. (C) Alternatively, the 3′-end of the next Okazaki fragment might interact with the sister chromatid to facilitate synthesis beyond the unligatable flap that is later displaced by the newly synthesized strand and degraded by exonucleases. (D) Unligated ends may persist until the next round of replication where they will serve as the leading-strand template and consequently force the fork to collapse, creating single-ended DSBs that may not be optimal substrates for template switching or direct-repeat recombination. This often results in chromosome loss and death in haploids (E), whereas in diploid cells (F), recombination with the homolog enables restart of the replication fork. Defective exonucleolytic digestion of residual flaps in rad3-102 rad27-null double mutants increases the incidence of unligated ends and results in synergistic increases in chromosome loss and interhomolog recombination in diploids, but kills haploids.

The interhomolog recombination observed in wild-type diploids is largely RAD51 independent (Klein 2001; Table 6), suggesting that the rad3-102 allele may stimulate a RAD51-independent form of BIR. In support of this notion, rad3-102 is not synthetically lethal in combination with the rad51-null allele (M. S. Navarro and A. M. Bailis, unpublished results). Interestingly, when we modified the interhomolog recombination assay such that gene conversion could be distinguished from BIR, we observed that a six- to sevenfold increase in gene conversion and BIR in a rad3-102 diploid was suppressed in a rad3-102 rad51-null diploid (Table 6). This may suggest that the large stimulation in interhomolog recombination observed in the rad3-102 rad27-null diploids occurs by a Rad51-dependent mechanism. However, this hypothesis cannot be directly addressed due to the inviability of rad27-null rad51-null double-mutant cells (Tishkoff et al. 1997; Symington 1998; Debrauwere et al. 2001).

TABLE 6.

BIR and GC rates in wild-type and mutant diploids

| Relevant genotype | BIR ratea (×10−5) | GC ratea (×10−5) |

|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 1.3 (0.93–1.8) | 0.22 (0.17–0.30) |

| rad3-102 | 8.5 (7.3–11) | 1.3 (0.97–1.6) |

| rad51 | 3.5 (2.9–5.0) | 0.37 (0.24–0.75) |

| rad3-102 rad51 | 4.6 (3.4–6.5) | 0.47 (0.24–0.89) |

BIR and gene conversion (GC) rates were determined from a minimum of seven trials in the diploids ABX1498, ABX1204, ABX1175, and ABX1611; 95% confidence intervals are indicated in parentheses.

The high degree of conservation of the DNA replication and repair apparatus throughout eukaryotic phylogeny supports the speculation that similar genetic or pharmacological disruptions of Okazaki fragment maturation and processing in human cells could lead to massive increases in LOH, and the initiation of carcinogenesis. In fact, such collisions between pharmacology and genotype may help to explain differential responses to chemotherapeutic drugs, some of which disrupt DNA synthesis in a manner that may elicit unforeseen DNA repair responses. We are further exploring the role that Rad3, and, by extension, its human homolog Xpd, may play in the response to replication lesions at the DNA level in the hope of better understanding the link between DNA replication and LOH through homologous recombination.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Haber, M. Lisby, R. Rothstein, J. McDonald, M. Fasullo, R. Malone, B. Montelone, and R. Kolodner for strains and plasmids. We also thank M. C. Negritto, L. Hoopes, P. Frankel, and members of the Bailis laboratory for stimulating discussions. We also thank several anonymous reviewers for suggesting improvements to the manuscript. This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grant GM57484 to A.M.B. and F31-GM067568 to M.S.N., as well as funds from the Beckman Research Institute of the City of Hope and the City of Hope National Medical Center.

References

- Aguilera, A., S. Chavez and F. Malagon, 2000. Mitotic recombination in yeast: elements controlling its incidence. Yeast 16: 731–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailis, A. M., and S. Maines, 1996. Nucleotide excision repair gene functon in short-sequence recombination. J. Bacteriol. 178: 2136–2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailis, A. M., and R. Rothstein, 1990. A defect in mismatch repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae stimulates ectopic recombination between homeologous genes by an excision repair dependent process. Genetics 126: 535–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailis, A. M., S. Maines and M. T. Negritto, 1995. The essential helicase gene RAD3 suppresses short sequence recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15: 3998–4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardwell, L., A. J. Bardwell, W. J. Feaver, J. Q. Svejstrup, R. D. Kornberg et al., 1994. Yeast RAD3 protein binds directly to both SSL2 and SSL1 proteins: implications for the structure and function of transcription/repair factor b. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91: 3926–3930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, A. J. R., and R. H. Schiestl, 2001. Homologous recombination as a mechanism of carcinogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1471: M109–M121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke, D., D. Dawson and T. Stearns, 2000. Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Callahan, J. L., K. J. Andrews, V. A. Zakian and C. H. Freudenreich, 2003. Mutations in yeast replication proteins that increase CAG/CTG expansions also increase repeat fragility. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23: 7849–7860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C., and R. D. Kolodner, 1999. Gross chromosomal rearrangements in Saccharomyces cerevisiae replication and recombination defective mutants. Nature 23: 81–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen, T. W., R. S. Sikorski, M. Dante, J. H. Shero and P. Heiter, 1991. Multifunctional yeast high-copy number shuttle vectors. Gene 110: 119–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes-Ledesma, F., and A. Aguilera, 2006. Double-strand breaks arising by replication through a nick are repaired by cohesin-dependent sister-chromatid exchange. EMBO Rep. 7: 919–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox, M. M., M. F. Goodman, K. N. Kreuzer, D. J. Sherratt, S. J. Sandler et al., 2000. The importance of repairing stalled replication forks. Nature 404: 37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daigaku, Y., S. Mashiko, K. Mishiba, S. Yamamura, A. Ui et al., 2006. Loss of heterozyosity in yeast can occur by ultraviolet irradiation during the S phase of the cell cycle. Mutat. Res. 600: 177–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, A. P., and L. S. Symington, 2004. RAD51-dependent break-induced replication in yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24: 2344–2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debrauwere, H., S. Loeillet, W. Lin, J. Lopes and A. Nicolas, 2001. Links between replication and recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a hypersensitive requirement for homologous recombination in the absence of Rad27 activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98: 8263–8269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Z., and M. Fasullo, 2003. Multiple recombination pathways for sister chromatid exchange in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: role of RAD1 and the RAD52 epistasis group genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 31: 2576–2585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasullo, M., and P. Dave, 1994. Mating type regulates the radiation-associated stimulation of reciprocal translocation events in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Gen. Genet. 243: 63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasullo, M. T., and R. W. Davis, 1987. Recombinational substrates designed to study recombination between unique and repetitive sequence in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84: 6215–6219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasullo, M., T. Bennet and P. Dave, 1999. Expression of Saccharomyces cerevisiae MATa and MAT alpha enhances the HO-endonuclease stimulation of chromosomal rearrangements directed by his3 recombinational substrates. Mutat. Res. 433: 33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feaver, W. J., J. Q. Svejstrup, L. Bardwell, A. J. Bardwell, S. Buratowski et al., 1993. Dual roles of a multiprotein complex from S. cerevisiae in transcription and DNA repair. Cell 75: 1379–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feaver, W. J., W. Huang, O. Gileadi, L. Meyers, C. M. Gustafsson et al., 2000. Subunit interactions in yeast transcription/repair factor TFIIH. Requirement for Tfb3 subunit in nucleotide excision repair. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 5941–5946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feitelson, M. A., B. Sun, N. L. S. Tufan, J. Liu, J. Pan et al., 2002. Genetic mechanisms of hepatocarcinogenesis. Oncogene 21: 2593–2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank, G., J. Qiu, M. Somsouk, Y. Weng, L. Somsouk et al., 1998. Partial functional deficiency of E160D flap endonuclease-1 mutant in vitro and in vivo is due to defective cleavage of DNA substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 33064–33072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friis, J., and H. Roman, 1968. The effect of the mating-type alleles on intragenic recombination in yeast. Genetics 59: 33–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli, A., T. Cervelli and R. H. Schiestl, 2003. Characterization of the hyperrecombination phenotype of the pol3-t mutation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 164: 65–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Game, J., and R. K. Mortimer, 1974. A genetic study of X-ray sensitive mutants in yeast. Mutat. Res. 24: 281–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel, D. J., and A. M. Bailis, 2002. Nucleotide excision reapir, genome stability, and human disease: new insight from model systems. J. Biomed. Biotech. 2: 55–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golin, J. E., and M. Esposito, 1977. Evidence for joint genic control of spontaneous mutation and genetic recombination during mitosis in Saccharomyces. Mol. Gen. Genet. 150: 127–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray, J. W., and C. Collins, 2000. Genome changes and gene expressions in human solid tumors. Carcinogenesis 21: 443–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenson, M., M. Mousset, J. M. Wiame and J. Bechet, 1966. Multiplicity of the amino acid permeases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. I. Evidence for a specific arginine-transporting system. Biochem. Biophys. Acta 127: 325–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, P. K., A. Sahota, S. A. Boyadjiev, S. Bye, C. Shao et al., 1997. High frequency in vivo loss of heterozygosity is primarily a consequence of mitotic recombination. Cancer Res. 57: 1188–1193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzder, S. N., H. Qiu, C. H. Sommers, P. Sung, L. Prakash et al., 1994. DNA repair gene RAD3 of S. cerevisiae is essential for transcription by RNA polymerase II. Nature 367: 91–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber, J. E., 1999. DNA recombination: the replication connection. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24: 271–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, J. J., and M. R. Lieber, 1994. The characterization of a mammalian DNA structure-specific endonuclease. EMBO J. 13: 1235–1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heude, M., and F. Fabre, 1993. a/α-control of DNA repair in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: genetic and physiological aspects. Genetics 133: 489–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, D. R., S. Prakash, P. Reynolds, R. Polakowska, S. Weber et al., 1983. Isolation and characterization of the RAD3 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and inviability of rad3 deletion mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 80: 5680–5684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoege, C., B. Pfander, G. L. Moldovan, G. Pyrowolaskis and S. Jentsch, 2002. RAD6-dependent DNA repair is linked to modification of PCNA by ubiquitin and SUMO. Nature 419: 135–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra, M. F., and R. E. Malone, 1987. Hyper-mutation caused by the rem1 mutation in yeast is not dependent on error-prone or excision repair. Mutat. Res. 178: 201–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, A. M., and J. E. Haber, 1999. Double-strand break repair in yeast requires both leading and lagging strand DNA polymerases. Cell 96: 415–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, E. L., N. Sugawara, J. Fishman-Lobell and J. E. Haber, 1996. Genetic requirements for the single-strand annealing pathway of double-strand break repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 142: 693–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinks-Robertson, S., M. Michelitch and S. Ramcharan, 1993. Substrate length requirements for efficient mitotic recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13: 3937–3950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, F., A. Lagerqvist, K. Erixon and D. Jenssen, 2004. A method to monitor replication fork progression in mammalian cells: nucleotide excision repair enhances and homologous recombination delays elongation along damaged DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 32: e157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamb, A., 2003. Consequences of nonadaptive alterations in cancer. Mol. Biol. Cell 14: 2201–2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi, K., Y. Taniguchi, A. Hatanaka, E. Sonoda, H. Hochegger et al., 2005. Fen-1 facilitates homologous recombination by removing divergent sequences at DNA break ends. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25: 6948–6955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein, H. L., 2001. Spontaneous chromosome loss in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is suppressed by DNA damage checkpoint functions. Genetics 159: 1501–1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokoska, R. J., L. Stefanovic, H. T. Tran, M. A. Resnick, D. A. Gordenin et al., 1998. Destabilization of yeast micro- and minisatellite DNA sequences by mutations affecting a nuclease involved in Okazaki fragment processing (rad27) and DNA polymerase δ (pol3-t). Mol. Cell. Biol. 18: 2779–2788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh, B. O., and L. S. Symington, 2004. Recombination proteins in yeast. Annu. Rev. Genet. 38: 233–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lea, D. E., and C. A. Coulson, 1949. The distribution of the numbers of mutants in bacterial populations. J. Genet. 49: 264–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengauer, C., K. W. Kinzler and B. Vogelstein, 1998. Genetic instabilities in human cancers. Nature 396: 643–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieber, M., 1997. The FEN-1 family of structure-specific nucleases in eukaryotic DNA replication, recombination and repair. BioEssays 19: 233–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim, C. R., Y. Kimata, M. Oka, K. Nomaguchi and K. Kohno, 1995. Thermosensitivity of green fluorescent protein fluorescence utilitzed to reveal novel nuclear-like compartments in a mutant nucleoporin NSP1. J. Biochem. 118: 13–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, F. L., K. Sperle and N. Sternberg, 1990. Intermolecular recombination between DNAs introduced into mouse L cells is mediated by a nonconservative pathway that leads to crossover products. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10: 103–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J., S. Chang, Y. Yang and A. F. Li, 2003. Loss of heterozygosity and DNA aneuploidy in colorectal adenocarcinoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 10: 1086–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisby, M., R. Rothstein and U. H. Mortensen, 2001. Rad52 forms DNA repair and recombination center during S phase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98: 8276–8282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisby, M., U. H. Mortensen and R. Rothstein, 2003. Colocalization of multiple DNA double-strand breaks at a single Rad52 repair centre. Nat. Cell Biol. 5: 572–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisby, M., J. H. Barlow, R. C. Burgess and R. Rothstein, 2004. Choreography of the DNA damage response: spatiotemporal relationships among checkpoint and repair proteins. Cell 118: 699–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, J., H. Debrauwere, J. Buard and A. Nicolas, 2002. Instability of the human minisatellite CEB1 in rad27Δ and dna2–1 replication-deficient yeast cells. EMBO J. 21: 3201–3211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, J., C. Ribeyre and A. Nicolas, 2006. a Complex minisatellite rearrangements generated in the total or partial absence of Rad27/hFEN1 activity occur in a single generation and are Rad51 and Rad52 dependent. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26: 6675–6689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, M., M. Foiani and J. M. Sogo, 2006. b Multiple mechanisms control chromosome integrity after replication fork uncoupling and restart at irreparable UV lesions. Mol. Cell 21: 15–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maines, S., M. C. Negritto, X. Wu, G. M. Manthey and A. M. Bailis, 1998. Novel mutations in the RAD3 and SSL1 genes perturb genome stability by stimulating recombination between short repeats in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 150: 963–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone, R. E., and M. F. Hoekstra, 1984. Relationships between a hyper-rec mutation (REM1) and other recombination and repair genes in yeast. Genetics 107: 33–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone, R. E., B. A. Montelone, C. Edwards, K. Carney and M. F. Hoekstra, 1988. A reexamination of the role of the RAD52 gene in spontaneous mitotic recombination. Curr. Genet. 14: 211–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEachern, M. J., and J. E. Haber, 2006. Break-induced replication and recombinational telomere elongation in yeast. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75: 111–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill, B. J., and C. Holm, 1998. The RAD52 recombinational repair pathway is essential in pol30 (PCNA) mutants that accumulate small single-stranded DNA fragments during DNA synthesis. Genetics 148: 611–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel, B., G. Grompone, M. Flores and V. Bidnenko, 2004. Multiple pathways process stalled replication forks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101: 12783–12788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitelman, F., B. Johansson and F. Mertens, 1994. Catalog of Chromosomal Aberrations in Cancer. Wiley-Liss, New York.

- Montelone, B. A., and K. J. Koelliker, 1995. Interactions among mutations affecting spontaneous mutation, mitotic recombination, and DNA repair in yeast. Curr. Genet. 27: 102–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montelone, B. A., and B. C. Liang-Chong, 1993. Interaction of excision repair gene products and mitotic recombination functions in yeast. Curr. Genet. 24: 481–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montelone, B. A., and R. E. Malone, 1994. Analysis of the rad3–101 and rad3–102 mutations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: implications for structure/function of Rad3 protein. Yeast 10: 13–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montelone, B. A., M. F. Hoekstra and R. E. Malone, 1988. Spontaneous mitotic recombination in yeast: the hyper-recombinational rem1 mutations are alleles of the RAD3 gene. Genetics 119: 289–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montelone, B. A., L. A. Gilberston, R. Nassar, C. Giroux and R. E. Malone, 1992. Analysis of the spectrum of mutations induced by the rad3–102 mutator allele of yeast. Mutat. Res. 267: 55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naumovski, L., and E. C. Friedberg, 1983. A DNA repair gene required for the incision of damaged DNA is essential for viability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 80: 4818–4821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negritto, M. C., J. Qiu, D. O. Ratay, B. Shen and A. M. Bailis, 2001. Novel function of Rad27 (FEN-1) in restricting short-sequence recombination. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21: 2349–2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormö, M., A. B. Cubitt, K. Kalllio, L. A. Gross, R. Y. Tsien et al., 1996. Crystal structure of the Aequorea victoria green fluorescent protein. Science 273: 1392–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paques, F., and J. E. Haber, 1999. Multiple pathways of recombination induced by double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63: 349–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parenteau, J., and R. J. Wellinger, 1999. Accumulation of single-stranded DNA and destabilization of telomeric repeats in yeast mutant strains carrying a deletion of RAD27. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19: 4143–4152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radford, D. M., K. L. Fair, N. J. Phillips, J. H. Ritter, T. Steinbrueck et al., 1995. Allelotyping of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: deletion of loci on 8p, 13q, 16q, 17p and 17q. Cancer Res. 55: 3399–3405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopalan, H., and C. Lengauer, 2004. Aneuploidy and cancer. Nature 432: 338–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranish, J. A., S. Hahn, Y. Lu, E. C. Yi, X. Li et al., 2004. Identification of TFB5, a new component of general transcription and DNA repair factor IIH. Nat. Genet. 36: 707–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reagan, M. S., C. Pittenger, W. Siede and E. C. Friedberg, 1995. Characterization of a mutant strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae with a deletion of the RAD27 gene, a structural homolog of the RAD2 nucleotide excision repair gene. J. Bacteriol. 177: 364–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Refsland, E. W., and D. M. Livingston, 2005. Interactions among DNA ligase 1, the flap endonuclease and proliferating cell nuclear antigen in the expansion and contraction of CAG repeat tracts in yeast. Genetics 171: 923–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick, M. A., 1976. The repair of double-strand breaks in DNA: a model involving recombination. J. Theor. Biol. 59: 97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick, M. A., and P. Martin, 1976. The repair of double-strand breaks in the nuclear DNA of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and its genetic control. Mol. Gen. Genet. 143: 119–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubnitz, J., and S. Subramani, 1984. The minimum amount of homology required for homologous recombination in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 4: 2253–2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh-Gohari, N., H. E. Bryant, N. Schultz, K. M. Parker, T. N. Cassel et al., 2005. Spontaneous homologous recombination is induced by collapsed replication forks that are caused by endogenous DNA single-strand breaks. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25: 7158–7169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer, J. K., and D. M. Livingston, 1998. Expansions of CAG repeat tracts are frequent in a yeast mutant defective in Okazaki fragment maturation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 7: 69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton, P., 1995. Bacteria in Biology, Biotechnology, and Medicine. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

- Sommers, C. H., E. J. Miller, B. Dujon, S. Prakash and L. Prakash, 1995. Conditional lethality of null mutations in RTH1 that encodes the yeast counterpart of a mammalian 5′ to 3′ exonuclease required for lagging strand synthesis in reconstituted systems. J. Biol. Chem. 270: 4193–4196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song, J. M., B. A. Montelone, W. Siede and E. C. Friedberg, 1990. Effects of multiple yeast rad3 mutant alleles on UV sensitivity, mutability, and mitotic recombination. J. Bacteriol. 172: 6620–6630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spell, R. M., and S. Jinks-Robertson, 2004. Determination of mitotic recombination rates by fluctuation analysis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Mol. Biol. 262: 3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara, N., and J. E. Haber, 1992. Characterization of double-strand break induced recombination: homology requirements and single-stranded DNA formation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12: 563–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara, N., X. Wang and J. E. Haber, 2003. In vivo roles of Rad52, Rad54, and Rad55 proteins in Rad51-mediated recombination. Mol. Cell 12: 209–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung, P., L. Prakash, S. Weber and S. Prakash, 1987. The RAD3 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae encodes a DNA-dependent ATPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84: 6045–6049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung, P., S. N. Guzder, L. Prakash and S. Prakash, 1996. Reconstitution of TFIIH and requirement of its DNA helicase subunits, Rad3 and Rad25, in the incision step of nucleotide excision repair. J. Biol. Chem. 271: 10821–10826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svejstrup, J. Q., Z. Wang, W. J. Feaver, X. Wu, D. A. Bushnell et al., 1995. Different forms of TFIIH for transcription and DNA repair: holo-TFIIH and a nucleotide excision repairosome. Cell 80: 21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symington, L. S., 1998. Homologous recombination is required for the viability of rad27 mutants. Nucleic Acids Res. 26: 5589–5595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szostak, J. W., T. L. Orr-Weaver, R. J. Rothstein and F. W. Stahl, 1983. The double-strand break repair model for recombination. Cell 33: 25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi, Y., H. Komori, W. Chang, A. Hudmon, H. Erdjument-Bromage et al., 2003. Revised subunit structure of yeast TFIIH and reconciliation with human TFIIH. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 43897–43900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi, Y., C. A. Masuda, W. H. Chang, H. Komori, D. Wang et al., 2005. Ubiquitin ligase activity of TFIIH and the transcriptional response to DNA damage. Mol. Cell 18: 237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, B. J., and R. Rothstein, 1989. The genetic control of direct-repeat recombination in Saccahormyces: the effect of rad52 and rad1 on mitotic recombination of a GAL10 transcriptionally regulated gene. Genetics 123: 725–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tishkoff, D. X., N. Filosi, G. M. Gaida and R. D. Kolodner, 1997. A novel mutation avoidance mechanism dependent on S. cerevisiae RAD27 is distinct from DNA mismatch repair. Cell 88: 253–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallen, E. A., and F. R. Cross, 1995. Mutations in RAD27 define a potential link between G1 cyclins and DNA replication. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15: 4291–4302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z., S. Buratowski, J. Q. Svejstrup, W. J. Feaver, X. Wu et al., 1995. The yeast TFB1 and SSL1 genes, which encode subunits of transcription factor IIH, are required for nucleotide excision repair and RNA polymerase II transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15: 2288–2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X., T. E. Wilson and M. R. Lieber, 1999. A role for FEN-1 in nonhomologous DNA end-joining: the order of strand annealing and nucleolytic processing events. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96: 1303–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y., Y. Liu, J. L. Argueso, L. A. Henricksen, H. Kao et al., 2001. Identification of rad27 mutations that confer differential defects in mutation avoidance, repeat tract instability, and flap cleavage. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21: 4889–4899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, D., and M. Fasullo, 2003. Multiple recombination pathways for sister-chromatid exchange in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: role of RAD1 and the RAD52 epistasis group genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 31: 2576–2585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L. M. Z., Q. Chai, J. Parrish, D. Xue, S. M. Patrick et al., 2005. Novel function of the flap endonuclease 1 complex in processing stalled DNA replication forks. EMBO Rep. 6: 83–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]