Abstract

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a pathogen that has disseminated throughout Canadian hospitals and communities. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of over 9,300 MRSA isolates obtained from the Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program has identified 10 epidemic strain types in Canada (CMRSA1 to CMRSA10). In an attempt to determine specific genetic factors that have contributed to their high prevalence in community and/or hospital settings, the genomic content of representative isolates for each of the 10 Canadian epidemic types was compared using comparative genomic hybridizations. Comparison of the community-associated Canadian epidemic isolates (CMRSA7 and CMRSA10) with the hospital-associated Canadian epidemic isolates revealed one open reading frame (ORF) (SACOL0046) encoding a putative protein belonging to a metallo-beta-lactamase family, which was present only in the community-associated Canadian epidemic isolates. A more restricted comparison involving only the most common hospital-associated Canadian epidemic isolates (CMRSA1 and CMRSA2) with the community-associated Canadian epidemic isolates did reveal additional factors that might be contributing to their prevalence in the community and hospital settings, which included ORFs encoding potential virulence factors involved in capsular biosynthesis, serine proteases, epidermin, adhesion factors, regulatory functions, leukotoxins, and exotoxins.

Over the past few decades, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) has become a major health concern on a global scale. MRSA is associated with toxin-mediated diseases such as toxic shock syndrome and scalded skin syndrome as well as more severe diseases such as bacteremia, pneumonia, endocarditis, and osteomyelitis. MRSA was first reported in Canada in 1981 (11) and has since disseminated nationwide. Although initially associated with nosocomial infections, community-associated isolates have appeared in many Canadian communities and appear to be rapidly disseminating, especially in western Canada (5, 13, 26).

From 1995 to 2004, 38 hospitals belonging to the Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program (CNISP) collected over 9,300 MRSA isolates, which were typed using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), for the purpose of national surveillance. A Canadian epidemic PFGE strain type has been defined as one that is clinically significant and isolated from five or more hospital sites or from three or more geographical regions across Canada (21). Initial surveillance from 1995 to 1999 identified six epidemic types of MRSA in Canada, CMRSA1 to CMRSA6 (23), where the “C” stands for Canadian and should not be confused with community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA). Since 1999, four new epidemic types (CMRSA7 to CMRSA10) have emerged (13; unpublished data). CMRSA1 to CMRSA6, CMRSA8, and CMRSA9 are typically hospital-associated MRSA (HA-MRSA), while CMRSA7 and CMRSA10 are commonly CA-MRSA.

This report describes the comparison of the genomic contents of representative isolates for each of the 10 Canadian epidemic PFGE types (CMRSA1 to CMRSA10) for the purpose of identifying genetic factors that might be indicative of virulence potential and/or epidemicity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

CMRSA isolates and molecular typing.

Isolates used in this study (Table 1) were obtained through the ongoing surveillance of MRSA at 38 hospitals in Canada by the CNISP (22). Strains were typed according to the Canadian standardized PFGE method as previously described (12). A single isolate representing the most common PFGE fingerprint pattern for each of the 10 epidemic CMRSA strain types was chosen arbitrarily to represent the CMRSA clusters. Multilocus sequence typing was performed using primers and PCR conditions described previously (3). Primers were synthesized and sequences were determined by the DNA Core Facility at the National Microbiology Laboratory (Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada). Sequences for each allele were compared to those in the current database of alleles available at www.mlst.net. Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) typing was performed using primers and conditions described previously (14).

TABLE 1.

Isolates used in this studya

| Isolate | Yr isolated | Epidemic type | HA or CA | Other PFGE name(s) | MLST | CCb | SCCmec type | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Col | NA | NA | NA | NA | ST250 | CC8 | I | The Institute of Genomic Research (Rockville MD) |

| 01S-0177 | 2001 | CMRSA1 | HA | USA600 | ST45 | CC45 | II | 21 |

| 01S-0277 | 2001 | CMRSA2 | HA | USA100/800/New York | ST5 | CC5 | II | 21 |

| 98S-0566 | 1997 | CMRSA3 | HA | ST241 | CC8 | III | 21 | |

| 99S-0966 | 1999 | CMRSA4 | HA | USA200/EMRSA16 | ST36 | CC30 | II | 21 |

| 01S-0354 | 2001 | CMRSA5 | HA | USA500 | ST8 | CC8 | IV | 21 |

| 00S-1054 | 2000 | CMRSA6 | HA | ST239 | CC8 | III | 21 | |

| 00S-0907 | 2001 | CMRSA7 | CA | USA400/MW2 | ST1 | CC1 | IV | 13 |

| 00S-0331 | 2000 | CMRSA8 | HA | EMRSA15 | ST22 | CC22 | IV | CNISP study |

| 01S-0965 | 2001 | CMRSA9 | HA | NA | ST8 | CC8 | II | CNISP study |

| 04S-0073 | 2004 | CMRSA10 | CA | USA300 | ST8 | CC8 | IV | CNISP study |

HA, hospital-associated isolate; CA, community-associated isolate; NA, not applicable.

CC, clonal cluster.

Comparative genomic hybridizations (CGH).

S. aureus ORFmer PCR primer pairs, representing 2,741 open reading frames (ORFs) from S. aureus Col, were purchased from Sigma Genosys (St. Louis, MO). PCR was performed using the manufacturer's guidelines and confirmed using agarose gel electrophoresis. The resulting ORF set was resuspended to a concentration of 100 to 200 ng/μl in 50% dimethyl sulfoxide, and 700 pl of each product was printed in house (DNA Core Facility, National Microbiology Laboratory, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada) onto UltraGAPS slides (Corning Incorporated Life Sciences, Acton, MA). The ORF set was printed in duplicate on each slide, with the replicate set being printed immediately below the first. Slides were checked for quality using the Paragon Microarray Quality Control Stain kit (Invitrogen).

Cultures were grown in brain heart infusion broth at 37°C for 18 h, centrifuged, and lysed using lysostaphin. Genomic DNA was extracted using the phenol-chloroform extraction method as described previously (17). The DNA was sheared to 300 to 500 bp by sonication with the Virsonic ultrasonic cell disruptor 100 (VirTis, Gardiner, NY) for 2.5 min. The concentration of sheared DNA was determined at 260 nm using the Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Nano-drop Technologies, Wilmington, DE) and subsequently diluted to 111 ng/μl in double-distilled water.

Sheared genomic DNA was labeled with dCTP coupled to Cy3 or Cy5 (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) via random primed labeling using the Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) Bioprime CGH kit. Cy dye incorporation was determined using the Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Nano-drop Technologies), and values over 0.020 pmol/ng were used in the experiments. Labeled DNA, along with 100 μg of yeast tRNA, was concentrated using Microcon YM-30 centrifugal filter devices (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The volume of the labeled DNA was adjusted to 55 μl using prehybridization buffer (3× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate], 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS] [Sigma]) and then boiled for 1 min 30 s prior to hybridization.

Arrays were blocked in prehybridization buffer containing 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin at 50°C for 1 h. The slides were washed in double-distilled water, rinsed in 100% isopropanol, and dried by centrifugation. The labeled probe was applied to the array and covered with a HybriSlip coverslip (Grace Bio-Labs, Bend, OR). Arrays were incubated at 55°C overnight in a 10-slide hybridization chamber (Genetix, United Kingdom). Hybridized arrays were removed from the chamber and immediately dipped in 55°C wash buffer 1 (2× SSC, 0.1% SDS) in order to remove the coverslip. The slides were then washed in wash buffer 1 for 5 min at 55°C. Slides were then removed to a 10-min room temperature wash in wash buffer 2 (0.1× SSC, 0.1% SDS). Residual SDS was then removed by four 1-min room temperature washes in 0.1× SSC and a final rinse in 0.01× SSC. Slides were dried using centrifugation and scanned using the Virtek (Ontario, Canada) Chipreader.

Microarray analysis.

Six hybridizations using three different biological replicates (the ORF set was printed in duplicate on each slide) were performed for each isolate and consisted of the test isolate labeled with Cy3 or Cy5 and Col labeled with the opposing dye (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). To rule out any dye bias, one of the three hybridizations for each isolate tested included a dye swap. Images generated from the Virtek Chipreader were imported into the ArrayPro Analyzer software package (Media Cybernetics, Inc., Silver Spring, MD). Data were filtered to include only spots whose fluorescence on the reference channel was greater than two times the background fluorescence. Data that were filtered out were eliminated from further analysis. Data were imported into Genomotyping Analysis by Charles Kim (9) and analyzed using a bin size of 0.10, no data smoothing, normal curve peak modeling, and a binary output (1 for present and 0 for absent/divergent) with a 0% estimated probability of presence. GeneMaths was used in order to sort the data and to insert null values wherever the data had been filtered out. All spot replicates were manually aligned using Microsoft Excel, and the following criteria were applied: (i) for any ORF, at least three of the replicates had to contain data, and if more than half the spots were 1's, the ORF was considered to be present; (ii) if more than half the spots were 0's, the ORF was considered to be absent/divergent; and (iii) if the 1 and 0 calls for one spot were equal, the status of that ORF was considered to be unknown. Once all the hybridization data had been combined, they were imported into a new GeneMaths database.

PCR validation.

PCR was carried out in a 50-μl solution containing 500 ng template DNA; 3 mM MgCl2; 0.2 mM each dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP; a 1× concentration of AmpliTaq Gold PCR buffer; and 0.5 units AmpliTaq Gold (Applied Biosystems). Primers were used at a final concentration of 1 μM and are listed in Table 2. Cycling conditions were 5 min at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 55°C, and 60 s at 72°C and a final 5-min extension step at 72°C. Resulting products were visualized on a Tris-borate-EDTA agarose (1.5%) gel. The amplicons were purified using Microcon YM-100 centrifugal filter devices (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and sequenced for validation.

TABLE 2.

PCR primers used for the validation of the CGH data

| Locus tag | Gene | Primer | Primer sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SACOL0046 | SA0046F | AAGTGCTTCATACACCGGGTCACA | |

| SA0046R | AGCCTCCTTACTGCGGAGATCAAA | ||

| SACOL0143 | cap5H | SA0143F | TGACCAACCAAGCCGTACAACA |

| SA0143R | TTCTCCCACCACTTGCTTTCCA | ||

| SACOL0144 | cap5I | SA0144F | AGGGTTTGGTCCGCATGAAGAAGT |

| SA0144R | CGGCGTAACTTCCTTTAGAACAATGCC | ||

| SACOL0145 | cap5J | SA0145F | ACCCAAGAAATTCCGCGAGGGTTA |

| SA0145R | GCCTAATCCGGCAGTAAATGCTGA | ||

| SACOL0886 | sek | SA0886F | TCTAATAGTGCCAGCGCTCAAGGT |

| SA0886R | GGTAACCCATCATCTCCTGTGTAG | ||

| SACOL0887 | sei | SA0887F | TGGTGGAATTACGTTGGCGAATCA |

| SA0887R | TCTGCTTGACCAGTTCCGGTGTAA | ||

| SACOL1871 | epiG | EpiGF1 | AAGCAAGCGCTCACATTTGTACCC |

| EpiGR1 | GAACCACGAATGATCTCCAAGCAC | ||

| SACOL1872 | epiE | EpiEF1 | ACGGGAACAGCGAATAGTGTGTCA |

| EpiER1 | AGCGTAATAAGCGGGATTCTCTGC | ||

| SACOL1874 | epiP | EpiPF1 | TGAACCGGAGGAAACAGGTGATGT |

| EpiPR1 | CATTACCAGCTGCAGCAACAACGA | ||

| SACOL1876 | epiC | EpiCF1 | AGTGGATTAGCTGGGATAGGGAGA |

| EpiCR1 | ACCCGTATTGCCATAACACCAACC | ||

| SACOL2196 | SA2196F | TGTATTGACAGGAAGTACATTTCAAAGTG | |

| SA2196R | GTTCAAGATAGCTTAAATATGCTTCGTC | ||

| SACOL2507 | sarU | SA2507F | GAAACGAAGCAGATGAACGCCGTA |

| SA2507R | CATCTGCAAGGGATCGTTCTTTGA |

RESULTS

Molecular characterization and epidemiology of CMRSA1 to CMRSA10.

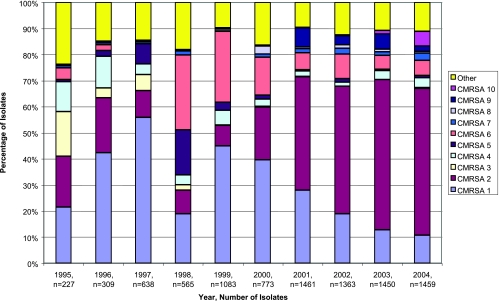

The 10 Canadian epidemic strain types each have unique epidemiological traits (Fig. 1 and Table 1). From 1995 to 2000, CMRSA1 was the most prevalent strain type but has now been replaced by CMRSA2, which accounted for approximately 55% of all isolates in 2004 (Fig. 1). CMRSA3 was most likely to cause an infection (23) but has virtually disappeared since 1997, being replaced by the closely related CMRSA6. The majority of CMRSA5 and CMRSA6 strain types were associated with a single hospital site (23). CMRSA8 is genetically similar to EMRSA15, a common European epidemic strain type (15). PFGE patterns of CMRSA7 and CMRSA10 were indistinguishable from those of USA400/MW2 and USA300, respectively, which are strain types linked with CA-MRSA outbreaks in the United States (7, 20). The occurrence of CMRSA7 and CMRSA10 has increased in Canada over the past few years; however, CMRSA10 has become the more prevalent of the two (Fig. 1), especially in western Canada. This has also been observed in the United States, where USA300 is more prevalent than USA400 (6, 7, 24).

FIG. 1.

MRSA isolates obtained through the CNISP from 1995 to 2004.

Genomic comparison of CMRSA1 to CMRSA10.

A complete summary of the genomic comparisons of CMRSA1 to CMRSA10 is presented in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Of the 2,704 interpretable ORFs represented on the array, 1,971 (73%) were present in all the isolates tested (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Comparison of the genomic contents of CMRSA1 to CMRSA10 revealed 21 variable regions, which were defined as three or more contiguous divergent/absent ORFs in three or more isolates (Table 3) (4). Nine ORFs were absent in all isolates, five of which were in variable region 2, containing the SCCmec region, and four of which were in variable region 7, containing bacteriophage L54a (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The presence or absence/divergence of select adhesins, exoenzymes, toxins, and regulatory systems determined using CGH for all 10 isolates is summarized in Table 4.

TABLE 3.

Locations and features of variable regions in the S. aureus genome determined using CGH

| Variable region | No. of ORFs | Location | Feature(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 31 | SACOL0035-SACOL0066 | SCCmec |

| 2 | 6 | SACOL0069-SACOL0074 | Transcriptional regulator |

| 3 | 5 | SACOL0079-SACOL0083 | All hypothetical proteins |

| 4 | 3 | SACOL0132-SACOL0134 | Degenerate replication and transposase proteins |

| 5 | 3 | SACOL0143-SACOL0145 | cap5HIJ |

| 6 | 22 | SACOL0276-SACOL0297 | Diarrheal toxin |

| 7 | 72 | SACOL0318-SACOL0390 | Bacteriophage L54a |

| 8 | 13 | SACOL0468-SACOL0483 | Exotoxins 2, 3, 4, and 5 |

| 9 | 9 | SACOL0644-SACOL0653 | All hypothetical proteins |

| 10 | 3 | SACOL0848-SACOL0850 | All hypothetical proteins |

| 11 | 27 | SACOL0885-SACOL0911 | Pathogenicity island, enterotoxins b and i |

| 12 | 9 | SACOL1339-SACOL1348 | All hypothetical proteins |

| 13 | 3 | SACOL1352-SACOL1354 | ABC transporter proteins |

| 14 | 14 | SACOL1573-SACOL1586 | traG, FtsK-like protein, integrase/recombinase |

| 15 | 5 | SACOL1857-SACOL1861 | Restriction enzyme hsdS |

| 16 | 21 | SACOL1864-SACOL1884 | Epidermin-related proteins, lukS and lukD, serine proteases |

| 17 | 4 | SACOL2012-SACOL2015 | Acetyltransferase, terminase, integrase/recombinase |

| 18 | 6 | SACOL2200-SACOL2205 | clpA-related protein |

| 19 | 5 | SACOL2494-SACOL2498 | All hypothetical proteins |

| 20 | 3 | SACOL2505-SACOL2507 | sarT and sarU |

| 21 | 5 | SACOL2726-SACOL2730 | 2 integrase/recombinase-related genes |

TABLE 4.

Presence or absence/divergence for select adhesins, exoenzymes, exotoxins, and regulatory elements in CMRSA1 to CMRSA10

| Locus tag | Gene | Description | Presence or absence/divergence in strain:

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMRSA1 | CMRSA2 | CMRSA3 | CMRSA4 | CMRSA5 | CMRSA6 | CMRSA7 | CMRSA8 | CMRSA9 | CMRSA10 | |||

| Adhesins | ||||||||||||

| SACOL0608 | sdrC | SdrC protein | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| SACOL0609 | sdrD | SdrD protein | +/− | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| SACOL0610 | sdrE | SdrE protein | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| SACOL1169 | fib | Fibrinogen-binding protein precursor-related protein | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| SACOL2509 | fnbB | Fibronectin-binding protein B | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| SACOL2511 | fnbA | Fibronectin-binding protein A | + | +/− | + | − | + | + | − | − | + | + |

| Exoenzymes | ||||||||||||

| SACOL1864 | Serine protease SplF | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | |

| SACOL1865 | Serine protease SplE | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | |

| SACOL1866 | Serine protease SplD | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | |

| SACOL1867 | Serine protease SplC | − | + | + | +/− | + | + | + | − | + | + | |

| SACOL1868 | Serine protease SplB | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | |

| SACOL1869 | Serine protease SplA | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | |

| SACOL1871 | epiG | Epidermin immunity protein | − (−) | − (−) | + (+) | − (−) | + (+) | + (+) | + (+) | − (−) | + (+) | + (+) |

| SACOL1872 | epiE | Epidermin immunity protein | − (−) | − (−) | + (+) | − (−) | + (+) | + (+) | + (+) | − (−) | + (+) | + (+) |

| SACOL1873 | epiF | Epidermin immunity protein | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| SACOL1874 | epiP | Epidermin leader peptide-processing serine protease | − (−) | − (−) | + (+) | − (−) | + (+) | + (+) | + (+) | − (−) | + (+) | + (+) |

| SACOL1875 | epiD | Epidermin biosynthesis protein | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| SACOL1876 | epiC | Epidermin biosynthesis protein | − (−) | − (−) | + (+) | − (−) | + (+) | + (+) | + (+) | − (−) | + (+) | + (+) |

| SACOL1877 | epiB | Epidermin biosynthesis protein | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| SACOL1878 | epiA | Lantibiotic epidermin precursor | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| SACOL2659 | aur | Aureolysin | +/− | + | + | − | + | +/− | + | + | + | + |

| Exotoxins | ||||||||||||

| SACOL0265 | Diarrheal toxin-like protein | +/− | +/− | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| SACOL0468 | Exotoxin 3 | +/− | +/− | + | − | + | + | − | − | + | + | |

| SACOL0469 | Exotoxin 2 | − | +/− | +/− | +/− | +/− | + | + | − | + | + | |

| SACOL0470 | Exotoxin 2 | +/− | +/− | +/− | +/− | + | + | + | − | + | + | |

| SACOL0472 | Exotoxin 2 | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | |

| SACOL0473 | Exotoxin 5 | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| SACOL0474 | Exotoxin 4 | +/− | +/− | +/− | +/− | +/− | +/− | − | − | + | + | |

| SACOL0478 | Exotoxin 3 | − | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | + | + | |

| SACOL0762 | “Hemolysin, putative” | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| SACOL0886 | sek | Staphylococcal enterotoxin | − (−) | − (−) | + (+) | − (−) | + (+) | + (+) | + (+) | − (−) | − (−) | + (+) |

| SACOL0887 | sei | Staphylococcal enterotoxin type I | − (−) | − (−) | + (+) | − (−) | + (+) | + (+) | + (+) | − (−) | − (−) | + (+) |

| SACOL0907 | seb | Staphylococcal enterotoxin B | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − |

| SACOL1178 | “Exotoxin 1, putative” | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | |

| SACOL1179 | “Exotoxin 4, putative” | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | |

| SACOL1180 | “Exotoxin 3, putative” | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| SACOL1880 | lukD | Leukotoxin LukD | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| SACOL1881 | lukS | Synergohymenotropic toxin LukS | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| SACOL2004 | lukF | “Leukocidin precursor, F subunit, putative” | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| SACOL2006 | lukM | Leukotoxin LukM | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| SACOL2160 | “Hemolysin, putative” | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | |

| Regulatory | ||||||||||||

| SACOL0072 | “Transcriptional regulator, LysR family” | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | |

| SACOL0074 | “Transcriptional regulator, LysR family” | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | |

| SACOL0091 | “Transcriptional regulator, GntR family” | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | |

| SACOL0672 | sarA | Staphylococcal accessory regulator A | +/− | +/− | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| SACOL1891 | RNA III-activating protein TRAP | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | |

| SACOL2023 | agrB | Accessory gene regulator protein B | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| SACOL2506 | sarT | Staphylococcal accessory regulator T | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| SACOL2507 | sarU | Staphylococcal accessory regulator U | − (−) | + (+) | + (+) | − (−) | + (+) | + (+) | + (+) | + (+) | + (+) | + (+) |

| SACOL2524 | “Transcriptional regulator, MarR family” | − | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | |

| Other | ||||||||||||

| SACOL0046 | Metallo-beta-lactamase family protein | − (−) | − (−) | − (−) | − (−) | − (−) | − (−) | + (+) | − (−) | − (−) | + (+) | |

| SACOL0143 | cap5H | Capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis protein | − (−) | +/− (+) | + (−) | − (−) | + (+) | − (−) | − (−) | + (+) | + (+) | + (+) |

| SACOL0144 | cap5I | Capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis protein | − (−) | +/− (+) | + (−) | +/− (−) | + (+) | − (−) | − (−) | + (+) | + (+) | + (+) |

| SACOL0145 | cap5J | Capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis protein | − (−) | +/− (+) | − (−) | + (−) | + (+) | − (−) | − (−) | + (+) | + (+) | + (+) |

| SACOL2196 | Hypothetical protein | + (+) | + (+) | + (+) | + (+) | + (+) | + (+) | − (−) | + (+) | + (+) | + (+) | |

a+, presence of gene; −, absence of gene; +/−, unknown. PCR results are shown in parentheses: +, positive PCR amplicon; −, negative PCR amplicon.

Genomic comparison of epidemic HA-CMRSA and epidemic CA-CMRSA.

Comparison of the genomic contents of the eight Canadian hospital-associated epidemic isolates CMRSA1 to CMRSA6, CMRSA8, and CMRSA9 with the two Canadian epidemic community-associated isolates CMRSA7 and CMRSA10 revealed 1,971 common ORFs. Investigation into identifying ORFs that are different between hospital-associated CMRSA (HA-CMRSA) and community-associated CMRSA (CA-CMRSA) isolates revealed only one ORF (SACOL0046) encoding a metallo-beta-lactamase family protein, which was specific to the CA-CMRSA isolates (Table 4). This potential biomarker for CA-CMRSA was further verified using PCR (Table 4). Conversely, no ORFs that were present in only the HA-CMRSA isolates compared to the CA-CMRSA isolates were identified (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

A more restricted comparison involving the two most common hospital-associated isolates in Canada (CMRSA1 and CMRSA2) with the two community-associated isolates (CMRSA7 and CMRSA10) revealed 51 differences (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The presence of ORFs specific to CMRSA7 and CMRSA10 included three SCCmec ORFs contained within variable region 1 (SACOL0035, SACOL0036, and SACOL0046), two staphylococcal enterotoxin ORFs contained within variable region 11 (SACOL0886 and SACOL0887), and seven epidermin ORFs contained within variable region 16 (SACOL1870 and SACOL1872 to SACOL1877) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The presence or absence of ORFs in only CMRSA7 and CMRSA10 encoding these two enterotoxins, as well as four select ORFs encoding epidermin and its modification factors, was confirmed using PCR (Table 4).

Genomic comparison of CMRSA1 and CMRSA2.

CMRSA1 was the most prevalent hospital-associated strain identified by the CNISP from 1995 to 1999 (23) but has since declined. On the contrary, CMRSA2 has increased substantially from 1999 to 2004 and has become the most prevalent strain type in Canada (Fig. 1). The genomic contents of these two hospital-associated isolates were compared to investigate potential ORFs specific to CMRSA2 that might be contributing to its prevalence. This comparison revealed 186 differences, 114 of which represented ORFs present in only CMRSA2 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). This included three ORFs in variable region 20 encoding an LPXTG motif protein (SACOL2505) as well as two accessory regulators, SarT (SACOL2506) and SarU (SACOL2507), seven ORFs in variable region 16 encoding serine proteases (SACOL1864, SACOL1866, and SACOL1867 to SACOL1869) and leukotoxins (SACOL1880 and SACOL1881), two exotoxins in variable region 8 (SACOL0472 and SACOL0473), as well as three additional exotoxins located downstream (SACOL1178 to SACOL1180). Three other ORFs of potential interest not identified in CMRSA1, but present in CMRSA2, include ORFs encoding an extracellular matrix-binding protein (SACOL0608), a fibrinogen-binding precursor-related protein (SACOL1169), and a putative pathogenicity protein (SACOL1472).

The 72 genes present in CMRSA1 but absent/divergent in CMRSA2 included 31 ORFs contained within bacteriophage L54a and 31 hypothetical ORFs of unknown function. One ORF of potential interest included the accessory gene regulator protein B (SACOL2023), which was absent in CMRSA2.

Genomic comparison of CMRSA7 and CMRSA10.

The occurrence of CMRSA7 and CMRSA10 has increased in Canada over the past few years; however, CMRSA10 has become the more prevalent of the two as determined by nosocomial surveillance (Fig. 1) and other reports (5). Comparison of the genomic content of these two isolates revealed 127 differences, 119 of which were ORFs present in only CMRSA10 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). This included three ORFs in variable region 5 involved in capsular biosynthesis (SACOL0143 to SACOL0145), three ORFs in variable region 8 encoding exotoxins (SACOL0468, SACOL0474, and SACOL0478), three ORFs contained within variable region 11 encoding two regulatory genes (SACOL0890 and SACOL0891) and a putative ORF (SACOL0903), and two other regulatory genes belonging to the GntR (SACOL0091) and MarR (SACOL2524) family. The eight ORFs present in only CMRSA7 but absent/divergent in CMRSA10 included four ORFs contained within bacteriophage L54a (SACOL0327, SACOL0328, SACOL0321, and SACOL0344), three hypothetical ORFs (SACOL0497, SACOL910, and SACOL2032), and an ORF encoding a glycosyl transferase family protein (SACOL0243).

A comparison of CMRSA1, CMRSA2, CMRSA7, and CMRSA10 revealed 17 ORFs present in only CMRSA2 and CMRSA10, which included 12 ORFs encoding hypothetical proteins and splD (SACOL1866), encoding a serine protease (Table 4; see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

DISCUSSION

Comparison of the genomic content of the 10 MRSA isolates used in this study revealed 1,971 invariant genes (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) representing the core genetic content of S. aureus, which is similar to previous estimates of 1,954 (10), 2,029 (2), and 2,198 (4) common genes. The 21 regions of variability highlighted in this study (Table 3) shared some similarities with the 18 regions of difference previously described for S. aureus (4). This included regions containing SCCmec, bacteriophage L54a, cap5, enterotoxins i and b, exotoxins 2 to 4, epidermin, leukocidin, and the region encoding two accessory regulators, SarT and SarU.

Analysis of the CGH data for each of the MRSA strain types examined determined that there was no specific or set of defined virulence factors whose presence or absence/divergence could definitively differentiate HA-MRSA from CA-MRSA isolates. Similar findings were reported in a recent study comparing the genomic content of an American epidemic community-associated strain type, USA300, with three other S. aureus lineages (24). From these studies, it cannot be concluded that such factors do not exist, as genes potentially indicative of epidemicity may not have been represented on the arrays.

A more restricted comparison did reveal the presence or absence/divergence of a few ORFs that might be of significance. For instance, comparison of the two most common HA-CMRSA isolates (CMRSA1 and CMRSA2) with the CA-CMRSA isolates (CMRSA7 and CMRSA10) revealed a gene cluster in the CA-CMRSA isolates encoding epidermin and its modification factors, which yields a lantibiotic against other gram-positive bacteria (18). The epidermin gene cluster has also been designated bsa (bacteriocin in S. aureus) in MW2 (1) and is similar to those previously reported for S. epidermidis (19). This gene cluster is carried on a type II genomic island, νSaβ, and was previously proposed to provide selective advantages for the MW2 CA-MRSA strain in competing with other bacterial species for colonization (1). However, the epi/bsa gene cluster cannot be used as a specific marker for CA-CMRSA strains, as it was also present in four epidemic HA-CMRSA isolates (CMRSA3, CMRSA5, CMRSA6, and CMRSA9) (Table 4).

Previous markers commonly used to detect CA-MRSA strains have included lukF-PV and lukS-PV, which encode the Panton-Valentine leukocidin. However, the presence of Panton-Valentine leukocidin is not an absolute indicator of CA-MRSA, as indicated by its absence in a number of community-associated isolates (16, 25; data not shown). Further examination of ORFs from our array that might be indicative of CA-CMRSA isolates revealed one ORF, SACOL0046, encoded within the J1 region of the SCCmec element, which was present only in CMRSA7 and CMRSA10. SACOL0046 encodes a putative protein belonging to a metallo-beta-lactamase family, and its presence in only community-associated epidemic strains is in accordance with data provided in a previous genomic hybridization study comparing epidemic community-associated strains (USA300 and USA400) with epidemic hospital-associated strains (USA100 and USA500) (24). Therefore, further studies involving the prevalence of SACOL0046 in other CA-MRSA genetic backgrounds should be conducted to determine if this factor is truly specific to established CA-MRSA isolates.

In comparison to the other nine CMRSA isolates used in this study, there were no ORFs represented on the array that could be solely responsible for the high prevalence of CMRSA2 (Fig. 1; see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Comparison of CMRSA2 with CMRSA1, which was the prevalent strain type up to 1999, did reveal some differences in genomic content that might be contributing to the higher occurrence of CMRSA2. These included ORFs encoding potential virulence factors involved in capsular biosynthesis, serine proteases, adhesion factors, regulatory functions, leukotoxins, and exotoxins (Table 4; see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The comparison of the two community-associated Canadian epidemic strain types (CMRSA7 and CMRSA10) also revealed additional virulence factors in CMRSA10 encoding proteins involved in capsular biosynthesis, exotoxins, regulatory functions, and adhesion (Table 4; see Table S1 in the supplemental material), which might be contributing to the prevalence of CMRSA10 in Canadian communities.

In a recent study, 61 invasive S. aureus isolates associated with community-acquired infections and 100 noninvasive S. aureus isolates previously collected from healthy blood donors were investigated using CGH (10). Similar to our study, those authors found many differences in genomic contents between isolates but no set of ORFs that could predict invasiveness. Alternatively, factors such as type of disease, location of acquisition, or epidemicity may be linked with host factors, environmental pressures, or gene expression patterns. Further studies into these additional factors could provide invaluable information in elucidating the potential pathogenicity and/or epidemicity of S. aureus strains, which could ultimately result in alternative targets for future antibiotic and/or vaccine development.

This is the first study to describe the genomic characteristics of Canadian epidemic CMRSA strain types. CGH comparisons have revealed some interesting genetic differences between hospital- and community-associated isolates, which warrant further examination to better understand the molecular aspects involved in the epidemic and community-associated nature of MRSA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The research described in this study was partially funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, grant number HSO-63189, and Health Canada.

We also thank Shari Tyson and Kathleen Dawson for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 11 April 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jcm.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baba, T., F. Takeuchi, M. Kuroda, H. Yuzawa, K.-I. Aoki, A. Oguchi, Y. Nagai, N. Iwama, K. Asano, T. Naimi, H. Kuroda, L. Cui, K. Yamamoto, and K. Hiramatsu. 2002. Genome and virulence determinants of high virulence community-acquired MRSA. Lancet 359:1819-1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cassat, J. E., P. M. Dunman, F. McAleese, E. Murphy, S. J. Projan, and M. S. Smeltzer. 2005. Comparative genomics of Staphylococcus aureus musculoskeletal isolates. J. Bacteriol. 187:576-592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Enright, M. C., N. P. J. Day, C. E. Davies, S. J. Peacock, and B. G. Spratt. 2000. Multilocus sequence typing for characterization of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible clones of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1008-1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fitzgerald, J. R., D. E. Sturdvent, S. M. Mackie, S. R. Gill, and J. M. Musser. 2001. Evolutionary genomics of Staphylococcus aureus: insights into the origin of methicillin-resistant strains and the toxic shock syndrome epidemic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:8821-8826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilbert, M., J. MacDonald, D. Gregson, J. Siushansian, K. Zhang, S. Elsayed, K. Laupland, T. Louie, K. Hope, M. Mulvey, J. Gillespie, D. Nielsen, V. Wheeler, M. Louie, A. Honish, G. Keays, and J. Conly. 2006. Outbreak in Alberta of community-acquired (USA300) methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in people with a history of drug use, homelessness or incarceration. CMAJ 175:149-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herold, B. C., L. C. Immergluck, M. C. Maranan, D. S. Lauderdale, R. E. Gaskin, S. Boyle-Vavra, C. D. Leitch, and R. S. Daum. 1998. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in children with no identified predisposing risk. JAMA 279:593-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunt, C., M. Dionne, M. Delorme, D. Murdock, A. Erdrich, D. Wolsey, A. V. Groom, J. E. Cheek, J. Jacobson, B. Cunningham, L. Shireley, K. Belani, S. Kurachek, P. Ackerman, S. Cameron, P. Schlievert, J. Pfeiffer, M. P. H. Hennepin, S. Johnson, D. J. Boxrud, J. Bartkus, M. S. Besser, K. Smith, K. H. LeDell, C. O'Boyle, R. Lynfield, K. White, M. T. Osterholm, and K. A. Moore. 1999. Four pediatric deaths from community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus—Minnesota and North Dakota, 1997-1999. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 48:707-710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reference deleted.

- 9.Kim, C. C., E. A. Joyce, K. Chan, and S. Falkow. 2002. Improved analytical methods for microarray-based genome-composition analysis. Genome Biol. 3:research0065.1-research0065.17. http://genomebiology.com/2002/3/11/research/0065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Lindsay, J. A., C. E. Moore, N. P. Day, S. J. Peacock, A. A. Witney, R. A. Stabler, S. E. Husain, P. D. Butcher, and J. Hinds. 2006. Microarrays reveal that each of the ten dominant lineages of Staphylococcus aureus has a unique combination of surface-associated and regulatory genes. J. Bacteriol. 188:669-676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Low, D. E., M. Garcia, S. Callery, P. Milne, H. R. Devlin, I. Campbell, and H. Vellend. 1981. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus—Ontario. Can. Dis. Wkly. Rep. 7:249-250. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mulvey, M. R., L. Chui, J. Ismail, L. Louie, C. Murphy, N. Chang, M. Alfa, and the Canadian Committee for the Standardization of Molecular Methods. 2001. Development of a Canadian standardized protocol for subtyping methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3481-3485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mulvey, M. R., L. MacDougall, B. Cholin, G. Horsman, M. Fidyk, S. Woods, and the Saskatchewan CA-MRSA Study Group. 2005. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Canada. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11:844-850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oliveira, D. C., and H. de Lencastre. 2002. Multiplex PCR strategy for rapid identification of structural types and variants of the mec element in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2155-2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richardson, J. F., and S. Reith. 1993. Characterisation of a strain of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (EMRSA-15) by conventional and molecular methods. J. Hosp. Infect. 25:45-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saïd-Salim, B., B. Mathema, K. Braughton, S. Davis, D. Sinsimer, W. Eisner, Y. Likhoshvay, F. R. DeLeo, and B. N. Kreiswirth. 2005. Differential distribution and expression of Panton-Valentine leucocidin among community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:3373-3379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 18.Saris, P. E., T. Immonen, M. Reis, and H. G. Sahl. 1996. Immunity to lantibiotics. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 69:151-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schnell, N., K. D. Entian, U. Schneider, F. Gotz, H. Zahner, R. Kellner, and G. Jung. 1988. Prepeptide sequence of epidermin, a ribosomally synthesized antibiotic with four sulphide-rings. Nature 333:276-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seybold, U., E. V. Kourbatova, J. G. Johnson, S. J. Halvosa, Y. F. Wang, M. D. King, S. M. Ray, and H. M. Blumberg. 2006. Emergence of commu-nity-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 genotype as a major cause of health care-associated blood stream infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42:647-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simor, A. E., D. Boyd, L. Louie, A. McGeer, M. Mulvey, and B. M. Willey. 1999. Characterization and proposed nomenclature of epidemic strains of MRSA in Canada. Can. J. Infect. Dis. 10:333-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simor, A. E., M. Ofner-Agostini, E. Bryce, K. Green, A. McGeer, M. Mulvey, S. Paton, and the Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program, Health Canada. 2001. The evolution of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Canadian hospitals: 5 years of national surveillance. CMAJ 165:21-26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simor, A. E., M. Ofner-Agostini, E. Bryce, A. McGeer, S. Paton, M. R. Mulvey, and the Canadian Hospital Epidemiology Committee and Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program, Health Canada. 2002. Laboratory characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Canadian hospitals: results of 5 years of national surveillance, 1995-1999. J. Infect. Dis. 186:652-660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tenover, F. C., L. K. McDougal, R. V. Goering, G. Killgore, S. J. Projan, J. B. Patel, and P. M. Dunman. 2006. Characterization of a strain of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus widely disseminated in the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:108-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Voyich, J. M., M. Otto, B. Mathema, K. R. Braughton, A. R. Whitney, D. Welty, R. D. Long, D. W. Dorward, D. J. Gardner, G. Lina, B. N. Kreiswirth, and F. R. DeLeo. 2006. Is Panton-Valentine leukocidin the major virulence determinant in community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus disease? J. Infect. Dis. 194:1761-1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wylie, J. L., and D. L. Nowicki. 2006. Molecular epidemiology of community- and health care-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Manitoba, Canada. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:2830-2836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.