Abstract

A series of unconventional microtubule organizing centers play a fundamental role during egg chamber development in Drosophila. To gain a better understanding of their molecular nature, we have studied the centrosomal component γ-tubulin during Drosophila oogenesis. We find that although single mutations in either of the two γ-tubulin genes identified in Drosophila do not affect oogenesis progression the simultaneous depletion of both protein products has severe consequences. The combination of loss-of-function mutant alleles for the two γ-tubulin genes leads to mitotic defects in female germ cells, resulting in agametic ovaries. A combination of weaker mutant alleles instead allows female germ-cell development to proceed, although the resulting egg chambers display pleiotropic abnormalities, most frequently affecting the number of nurse cells and oocytes per egg chamber. Thus, γ-tubulin is required for several processes at different stages of germ-cell development and oogenesis, including oocyte determination and differentiation. Our data provide a functional link between a component of the peri-centriolar material, such as γ-tubulin, and microtubule organization during Drosophila oogenesis. In addition, our results show that γ-tubulin is required for female germcell proliferation and that the two γ-tubulins present in Drosophila are functionally equivalent during female germ-cell development and oogenesis.

Drosophila oogenesis starts with the asymmetric division of a germ-line stem cell to generate a cystoblast that in turn divides, producing a cyst of 16 cells interconnected by ring canals. The cyst, surrounded by a layer of follicle cells of somatic origin, forms the egg chamber. One of the 16 cystocytes will become the oocyte, whereas the remaining 15 (nurse cells) undergo endoreduplication and supply the oocyte with materials through the ring canals (reviewed in ref. 1).

The microtubule cytoskeleton is required for essential steps at different stages of oogenesis (2-7). A functional microtubule organizing center (MTOC) is needed for the oocyte to differentiate (2, 3) and define the position of the oocyte nucleus in midoogenesis (2), thereby specifying the future dorso-ventral axis of the embryo (8-10). Moreover, the movement of particles within nurse cells (11), the delivery of determinants to their correct position in the oocyte (for reviews, see refs. 12-14) and the ooplasmic streaming that redistributes the oocyte content in late oogenesis (15) are microtubule dependent.

The microtubule cytoskeleton organization undergoes a series of major rearrangements during egg chamber differentiation (reviewed in refs. 14 and 16). In the early cyst, microtubules originate within the oocyte with their minus ends adjacent to the posterior oocyte cortex (3, 17). From the oocyte, they reach the nurse cells passing through the intercellular bridges that connect them. At midoogenesis the microtubules are more concentrated at the anterior side of the oocyte (18, 19). Later on, long microtubules are located all along the surface of the oocyte, which after maturation are replaced by short, randomly oriented microtubules (18).

Despite the important role of the microtubule cytoskeleton during oogenesis and its dynamic organization, the information regarding MTOCs is rather fragmentary. The centrioles of the cystocytes migrate through the intercellular bridges of the newly formed egg chamber to the presumptive oocyte, thus defining the major MTOC of the entire cyst (3, 20-22). These centrioles were detected up to stage 1 of egg chamber differentiation (21, 22), but were no longer observed at midoogenesis (23). At later stages of oogenesis the position of the MTOC has been deduced by the organization of the microtubule cytoskeleton (3, 18, 19, 22), microtubule depolymerization/repolymerization experiments (18), and localization of microtubule polarity reporters (17, 21, 24, 25). The molecular nature of the MTOCs in oogenesis is just starting to be investigated. Centrosomin (CNN), an essential component of the centrosomes of proliferating cells (26-29), associates with the centrosomes of dividing cystoblasts, but is not detectable in 16-cell cysts in the germarium (21). Thereafter, CNN colocalizes with the minus ends of microtubules at stages 6-10 of oogenesis (27). γ-Tubulin is present on the centrosomes in the germarium and on migrating centrioles (21, 22). Furthermore, it localizes all around the oocyte cortex during stages 8-10 (30) and accumulates at the anterior cortex of egg chambers at midoogenesis (31).

To gain a better understanding of how microtubule organization is achieved during Drosophila oogenesis, we have studied the role of γ-tubulin during this process. γ-Tubulin is involved in the nucleation of microtubules (ref. 32 and references therein) and is present at the centrosomes and MTOCs in many different systems (ref. 33 and references therein). In Drosophila two γ-tubulins are known, γTub23C and γTub37C, with divergent expression patterns and mutant phenotypes. γTub23C is ubiquitous and required for somatic mitotic divisions, male meiosis, and spermatogenesis (34, 35). γTub37C is expressed in ovaries and at early stages of development and is required for bcd mRNA localization at midoogenesis (31), female meiosis, and nuclear proliferation in early embryos (33, 36, 37).

We show that the simultaneous depletion of both γ-tubulin gene products has severe consequences on oogenesis progression. The combination of strong loss-of-function mutant alleles of the two γ-tubulin genes results in female germ-cell mitotic defects, leading to agametic ovaries. A combination of milder mutant alleles, instead, allows female germ cells to develop, but the resulting egg chambers are abnormal. The defects observed indicate that γ-tubulin, a highly conserved centrosomal component, is also required for the function of the unconventional MTOCs present during oogenesis. These observations also suggest that the two γ-tubulin proteins are functionally equivalent during female germ-cell development.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila Cultures and Stocks. All used lines are described in Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org. Recombinants between fs(2)TW11, fs(2)TW1RU34, and γTub23CPI were obtained by standard genetic procedures. γTub23CPI b fs(2)TW11 px sp was balanced over T(2:3)TSTL, Tb (J. Casal and C.G., unpublished work) to distinguish homozygous larvae and pupae. Two stocks were analyzed for the weaker combination: γTub23CPI fs(2)TW1RU34cn px sp (stock 33) and γTub23CPI fs(2)TW1RU34 cn c px sp (stock 55). For rescue experiments we used the construct P[γTub37C+] (33) or the construct P[γTub23C+] carrying the entire γTub23C gene (S. Llamazares, personal communication).

Cytology. To preserve tubulin, adult ovaries were dissected in PBS at room temperature and fixed for 10 min in methanol at -20°C. Before blocking and antibody incubation, ovarioles were separated and permeabilized in PBS with 1% Triton X-100 for 1 h. All other procedures were standard and are described in Supporting Text.

Results

The Simultaneous Depletion of the Two γ-Tubulin Gene Products Results in Agametic Ovaries, Caused by Germ-Cell Loss During Development. To address the role of γ-tubulin in oogenesis, we studied the behavior of microtubules in WT flies or flies homozygous for either γTub23CPI (34, 35) or fs(2)TW11 (33, 36, 38), which are the most severe mutant alleles available for γTub23C and γTub37C, respectively (see Supporting Text). We found that the microtubule cytoskeleton is overall properly organized during oogenesis in female mutants for either of the two γ-tubulin (Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), suggesting that the two protein products are redundant during oogenesis. To test this hypothesis we generated flies mutant for both γ-tubulins. We have studied two different combinations of γ-tubulin double mutant flies. Both of them carry γTub23CPI (34, 35) in combination with either fs(2)TW11, a severe loss of function of γTub37C,or fs(2)TW1RU34, a hypomorph allele of the same gene (33, 36, 37).

Homozygous γTub23CPI fs(2)TW11 females are agametic with rudimentary ovaries (Figs. 1L and 7D). The agametic phenotype is fully rescued by transposons carrying a WT copy of either of the two γ-tubulins. In contrast to this dramatic effect in oogenesis, the only alterations observed in spermatogenesis are post-mitotic and identical to those produced by the γTub23CPI mutation on its own (35). Failure to form germ cells (12, 39) or their loss during development (40) result in agametic ovaries. In γTub23CPI fs(2)TW11 mutant embryos (Fig. 1B) germ cells form, migrate, and populate the gonads just as they do in control animals (Fig. 1 A). Ovaries of mutant second-instar larvae (Fig. 1D) are also indistinguishable from the WT (Fig. 1C) by anti-Vasa staining. By the third-instar larva stage the number of germ cells is slightly reduced (Fig. 1F, compare with Fig. 1E). At the prepupa stage, germ cells are found scattered throughout the mutant ovary, their total number is dramatically reduced (Fig. 1H, see Supporting Text for a detailed description of WT ovary differentiation through the pupal stages), and the shape and size of some of those cells are also abnormal (Fig. 1H, arrow). In the WT at this stage, germ cells are still concentrated at the equator of the ovary, contacting the terminal filaments anteriorly (41) (Fig. 8 B and E, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). From this stage on germ cells degenerate and steadily disappear in the mutant (Fig. 1J, compare with Fig. 1I) so that in adult ovaries (Fig. 1L) the germaria are empty and the anti-Vasa antibody recognizes only a few dispersed spots that may correspond to degenerating germ cells. These spots disappear in 4- to 5-day-old mutant females.

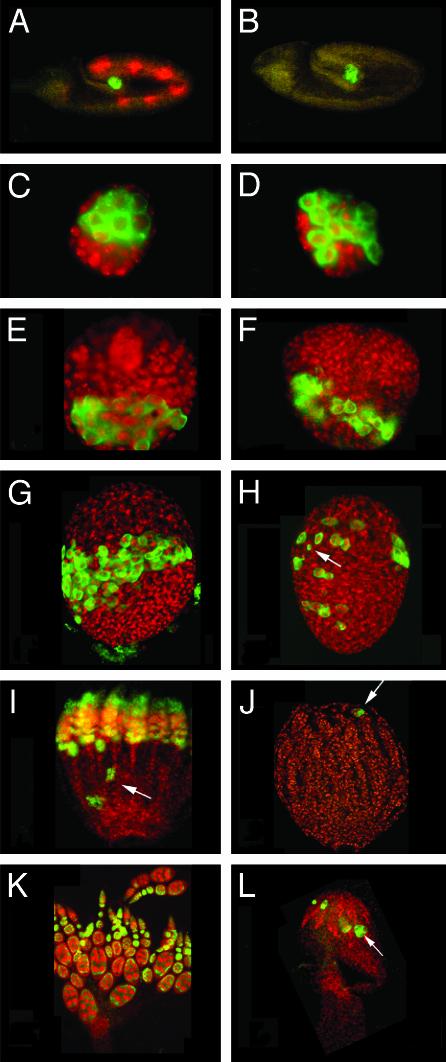

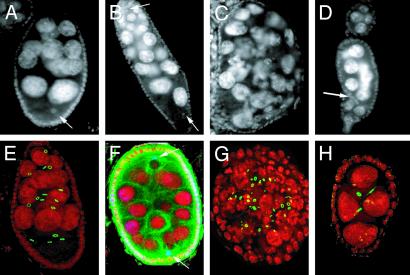

Fig. 1.

Germ cells degenerate starting at the late larva stage in γTub23CPI fs(2)TW11 double mutant females. Germ cells in control γTub23CPI fs(2)TW11/+ heterozygous animals (A, C, E, G, I, and K) and γTub23CPI fs(2)TW11 homozygous animals (B, D, F, H, J, and L) at different stages of development visualized with anti-Vasa antibody (green) and counterstained with anti-β-galactosidase antibodies (red) for a blue balancer (see Materials and Methods)(A and B) or the DNA stain TOTO-3 (red) (C-L). The stages shown are embryos (A and B) and ovaries from second-instar larva (C and D), third-instar larva (E and F), P1 pupa (G and H), P5/6 pupa (I and J), and 1-day-old adult (K and L). All gonads are oriented with their posterior end to the bottom. (A-D) We did not detect any difference between control and homozygous individuals from embryogenesis until second-instar larva. In mutant third-instar larva ovaries (F) the number of germ cells is slightly reduced in comparison to the WT (E; diameter of the gonad is 60 μm). Prepupa γTub23CPI fs(2)TW11 homozygous ovaries (H) contain fewer germ cells than control ovaries (G) and germ cells are dispersed throughout the gonad. In older pupae mutant ovaries contain only a few Vasa-positive cells (J), sometimes clustered (arrow). At this stage most WT germ cells are arranged within ovarioles (I) that already contain egg chambers and few clusters of germ cells lagging behind at the posterior half of the ovary (arrow). In WT adult ovaries (K) Vasa is present in the cysts in the germarium and is enriched in the nurse cells of later cysts. In γTub23CPI fs(2)TW11 double mutant ovaries (L) a few Vasa-positive cells and clusters are still present (arrow). (A-F, K, and L) Images were produced by conventional fluorescence microscopy. (G-J) Projections of confocal sections.

Thus maintenance of the female germ line in Drosophila requires γ-tubulin. Moreover, unlike in other tissues and developmental stages, which specifically require one of the two γ-tubulin products (refs. 33 and 34 and S. Llamazares, personal communication), either of them can provide the function required for female germ-line differentiation.

Germ-Cell Mitosis Is Abnormal in γTub23CPI fs(2)TW11 Homozygous Females. To determine the cause of germ-cell degeneration in γTub23CPI fs(2)TW11 homozygous females, we examined mitosis in these cells (Fig. 2) in late third-instar larvae, when the first signs of germ-cell degeneration appear. Fig. 2A shows a normal mitotic germ cell from a control γTub23CPI fs(2)TW11 heterozygous female, with a well-organized metaphase plate and the two centrosomes positioned at its opposite sides. In half of the female germ-cell mitotic figures of γTub23CPI fs(2)TW11 mutants (n = 10) the centrosomes are not aligned along the axis of the condensed chromosome plate. Furthermore, the level of condensation of the chromosomes is too high, as judged by their appearance as short, thick, and separate units (Fig. 2 B-D). The mitotic cell in Fig. 2B contains a single centrosome or two very close unsegregated centrosomes (arrow). Correspondingly, mitotic spindles are composed of short (Fig. 2H), often disorganized, microtubules associated with the chromosomes (Fig. 2 F and G, compare with Fig. 2E for the WT). In conclusion, the γ-tubulin defect produces severe abnormalities in spindle organization in the germ line.

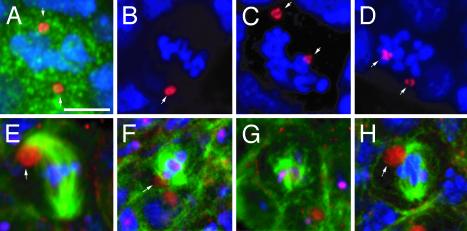

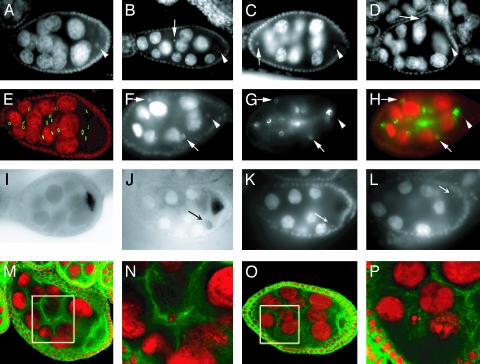

Fig. 2.

Mitotic divisions are affected in γTub23CPI fs(2)TW11 third-instar larva ovaries. Mitotic cells of the germ line in WT (A and E) and γTub23CPI fs(2)TW11 (B-D and F-H) third-instar larva ovaries. The germ cells were identified by immunostaining with an anti-Vasa antibody in A-D (green, shown only in A) or with anti-β-spectrin antibody in E-H (red). DNA is in blue in A-H, centrosomes in A-D were stained with an anti-centrosomin antibody (red), and microtubules in E-H were stained with anti-α-tubulin antibodies (green). (A-D) Centrosomes are positioned at opposite sides of the condensed chromosomes in a WT division (A, arrows). In mutant germ cells centrosomes are not correctly aligned (C and D, arrows). (B) A mutant mitotic cell with a single centrosomal signal (arrow). (E-H) Normal mitotic division in a WT germ cell (E). The spectrosome is associated with one spindle pole (arrow). In the mutant the spindle can be almost normal (H)to very poorly organized (F and G). The spectrosome is associated with the spindle, but not always with the spindle pole (F, arrow). All panels are projections of confocal sections. (Scale bar is 5 μm.)

γTub37C Is Present at the Centrosomes of Female Germ Cells, but Not of Gonadal Somatic Cells. The somatic tissue of the ovary seems to be far less affected by the γTub23CPI fs(2)TW11 double mutant than the germ line. To understand the reason for this, we studied the distribution of γTub37C in whole-mount preparations of WT ovaries. These were stained with Rb1011, specific for γTub37C (33), or Rb1015, which recognizes both γ-tubulins (see Materials and Methods). Rb1011 decorates the centrosomes of dividing germ cells (Fig. 3A, arrows), but not those of somatic cells (Fig. 3B, arrows indicate putative position of centrosomes). Rb1015, instead, recognizes the centrosomes of both somatic (Fig. 3D, arrows) and germ cells (Fig. 3C, arrows) that are undergoing mitosis. Hence, γTub37C is present in the centrosome of the female germ cells, but absent or below detection levels, in the centrosome of the surrounding somatic cells of the ovary.

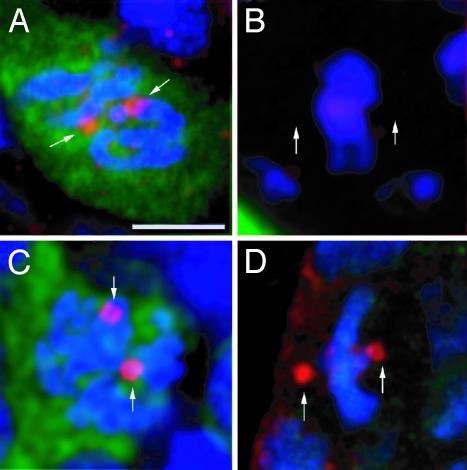

Fig. 3.

Cell type-dependent expression of γTub37C. Germ (A and C) and somatic (B and D) cells from WT third-instar larva ovaries stained (red) with antibodies that recognize only γTub37C (A and B) or both γ-tubulin isoforms (C and D). The germ cells are identified by immunostaining with an anti-VASA antibody (green), and DNA was stained with TOTO-3 (blue). γTub37C is detected at the centrosomes of dividing germ cells (A, arrows) but not in dividing somatic cells (B, arrows point to putative position of the centrososmes). All images are projections of confocal sections. The reddish appearance of DNA in B is caused by bleed-through of TOTO-3 into the red channel in this preparation and does not represent a specific signal. (Scale bar is 5 μm.)

A Weaker Combination of γ-Tubulin Mutant Alleles Results in Defective Egg Chambers. Females carrying the weaker double mutant combination γTub23CPI fs(2)TW1RU34 are sterile, but lay a few eggs. Their ovaries are much reduced in size and contain only a few egg chambers (Fig. 4 and Table 1). Some of the ovaries are completely empty (Fig. 4A) or contain only one or two degenerating egg chambers (Fig. 4B, arrow), whereas others contain some egg chambers at various stages of development (Fig. 4 C and D, arrow), including mature oocytes (Fig. 4F, arrow). These phenotypes are fully rescued by transposons carrying a WT copy of either of the two γ-tubulins. There are no significant differences between mutant and control in the average number of ovarioles per ovary (Table 1), consistent with the negligible effect that this mutant condition seems to have on the development of the somatic tissue of the ovary. However, more than half of the ovarioles in the double mutant combination are empty, and the average number of egg chambers per ovary in the mutant is about eight times less than in heterozygous flies and around half of them are abnormal (Table 1). The empty ovarioles found in γTub23CPI fs(2)TW1RU34 homozygous ovaries resemble the phenotype seen in γTub23CPI fs(2)TW11 ovaries (e.g., Fig. 4A, arrow). They are possibly also produced by germ-cell degeneration during development, as in γTub23CPI fs(2)TW11, because we found no difference between the number of empty and full ovarioles in 1- and 10-day-old females, indicating that germ-cell maintenance in adult mutant females is not severely compromised.

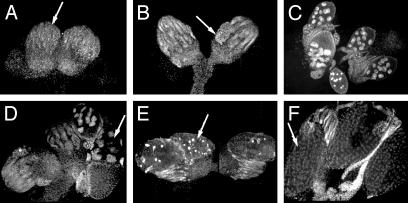

Fig. 4.

Abnormal oogenesis of γTub23CPI fs(2)TW1RU34 homozygous females. Ovaries from γTub23CPI fs(2)TW1RU34 double mutant females stained with DAPI (see Fig. 1K for comparison with the WT). (A) Rudimentary ovaries resembling the phenotype of the γTub23CPI fs(2)TW11 combination. Arrow points to an empty ovariole. (B) Ovaries containing only a few degenerating egg chambers with highly condensed DNA (arrow). (C and D) Ovaries with empty ovarioles and ovarioles with differentiated egg chambers up to stage 10 (arrow in D). (E and F) Ovaries containing a few mature oocytes that are small and display highly condensed DNA (E, arrow) or are apparently normal (F, arrow).

Table 1. Quantification of the mutant phenotypes observed in γTub23CPI fs(2)TW1RU34 mutant ovaries.

|

Ovarioles

|

Egg chambers

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stock line | Ovaries | Total | Per ovary | Empty, % | Total | Per ovary | Abnormal, % |

| γTub23CPI fs(2)TW1RU34 (line no. 55) | 19 | 256 | 13.5 | 50 | 170 | 8.9 | 64 |

| γTub23CPI fs(2)TW1RU34 (line no. 33) | 14 | 175 | 12.5 | 77 | 109 | 7.8 | 45 |

| γTub23CPI fs(2)TW1RU34/+ (line no. 33) | 8 | 120 | 15.0 | 0 | 529 | 66.0 | 8 |

| γTub23CPI fs(2)TW1RU34; P[37C+] (line no. 33) | 4 | 48 | 12.0 | 0 | 214 | 53.5 | 0 |

Ovarioles and egg chambers per ovary and frequency of abnormal egg chambers in homozygous females from two γTub23CPI fs(2)TW1RU34 lines (no. 55 and no. 33), heterozygous females from line no. 33 and homozygous females from the same stock carrying a transposon that contains the γTub37C WT transgene, P[37C+] (33).

Within the egg chambers that develop, ≈50% show abnormalities that can be observed by phase-contrast microscopy and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining (Table 2). The type of abnormality observed was the same among different recombinant lines, but their frequency was different (Table 2). Most abnormal egg chambers present one of three major phenotypes: degenerating egg chambers with pycnotic DNA (Fig. 4E, arrow), egg chambers with 14 nurse cells and two oocyte-like nuclei (14 + 2 in Table 2), and compound egg chambers that contain >16 cells (>16 in Table 2). The remaining abnormal egg chambers show a variety of phenotypes, which occur at lower frequency. These include egg chambers with <16 germ cells, egg chambers with misplaced oocyte or abnormally shaped oocyte nucleus, oocytes containing endoreduplicated nuclei, reduced oocyte growth, abnormal positioning of the dorsal appendages, and egg chambers containing 16 nurse cells and no oocyte. Therefore, degenerating egg chambers aside, the majority of the abnormal phenotypes of γTub23CPI fs(2)TW1RU34 affects either the total cell number or the ratio between nurse cells and oocytes within egg chambers.

Table 2. Relative frequency of the abnormal phenotypes observed in egg chambers of line nos. 33 and 55 homozygous females.

|

Abnormal egg chambers

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Abnormal number of nurse cells and oocytes

|

||||||||||

| Stock line | Total | 14 + 2 | >16 | <16 | 16 + 0 | Endoreduplicated nuclei within the oocyte | Abnormal position of the oocyte nucleus | Broken oocyte nucleus | Reduced oocyte size | Degenerating egg chambers |

| γTub23CPI fs(2)TW1RU34 (line no. 33) | 51 | 32 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| γTub23CPI fs(2)TW1RU34 (line no. 55) | 117 | 8 | 34 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 62 |

γ-Tubulin Defect Affects the Number of Germ Cells per Egg Chamber. Egg chambers that contain too many germ cells are of two types in γTub23CPI fs(2)TW1RU34 mutants. In egg chambers like the one shown in Fig. 5B, which contain two distinct groups of nurse cell nuclei of different dimensions and two oocyte nuclei, the cause for the supernumerary germ cells was fusion. Consistently, in these egg chambers there are two distinct populations of ring canals and four ring canals by each oocyte (data not shown). Tubulin staining shows two clearly distinct microtubule foci, each associated with one oocyte nucleus (Fig. 5F, arrows). In contrast, in egg chambers where the dimensions of most nurse cell nuclei and ring canals are mixed and heterogeneous, the supernumerary cells were probably produced by extra rounds of mitosis (Fig. 5 C and G). At a low rate, egg chambers with too few germ cells are also observed in γTub23CPI fs(2)TW1RU34 ovaries (Fig. 5 D and H) and are in part produced by abnormal migration of the follicle cells within a forming egg chamber (Fig. 5D, arrow) (42, 43). Arrest of cystoblast mitotic divisions could also be at the origin of the phenotype in a subset of the chambers with reduced cell number (Fig. 5H). Consistently, γTub23C and γTub37C have been shown to lead to mitotic arrest in somatic tissues and the early embryo, respectively (34, 36).

Fig. 5.

Egg chambers with incorrect number of germ cells in γTub23CPI fs(2)TW1RU34 mutant females. Immunofluorescence of egg chambers from WT (A and E) and γTub23CPI fs(2)TW1RU34 (B-D and F-H) females, stained with DAPI (gray in A-D and red in E-H). Ring canals are green in E, G, and H. Posterior is to the bottom. (B and F) Egg chambers produced by fusion of adjacent egg chambers. Two oocyte nuclei are located at opposite ends (arrows), and the total number of nurse cells corresponds to 30. (F) Tubulin staining (green) and nodkhc-LacZ localization (blue) reveal that an MTOC is associated with each of the two oocyte nuclei. (C and G) Two egg chambers containing >16 germ cells, likely produced by extra rounds of mitotic divisions judging by the nurse cell size, the shape of the egg chamber, and the mixed population of ring canals in G.(D and H) Shown are <16 egg chambers. There are follicle cells within the egg chamber in D (arrow). The egg chamber in H contains only four germ cells and three ring canals, suggesting an early arrest of the mitotic program. Images A-D were obtained by conventional fluorescence microscopy. Images E-H are projections of confocal sections. Egg chamber size is ≈150 μm.

γ-Tubulin Defect Affects Oocyte Determination. A high percentage of the abnormal egg chambers found in γTub23CPI fs(2)TW1RU34 double mutant females contain 14 nurse cell nuclei and two oocyte-like nuclei (Fig. 6 and Table 2). In these cases, one of the two oocyte-like nuclei is always located posteriorly and within one of the four ring-canal cells of the cyst, like a WT oocyte (arrowheads in Fig. 6 A-D and F-H). The second oocyte-like nucleus, on the other hand, can be found anywhere within the egg chamber (Fig. 6 B-D, arrows), in cells with any number of ring canals (Fig. 6 F-H, arrows point to two oocyte-like nuclei within cells with only one ring canal). Thus, the ectopic oocyte-like nucleus does not belong to the second pro-oocyte. The level of endoreduplication of the ectopic oocyte-like nucleus is variable, as judged by its size (Fig. 6D). The 14 + 2 egg chamber phenotype was never observed after stage 10, possibly because of degeneration of these egg chambers after that stage or to reversion of the ectopic oocyte-like nucleus to a nurse cell fate. To define whether the second oocyte-like nucleus-containing cell has assumed an oocyte fate we performed in situ hybridizations to osk mRNA, which localizes very early within the oocyte (44). Although it was difficult to preserve the mutant egg chambers during the hybridization procedure, at least in one instance we could detect the presence of osk mRNA associated with the second oocyte-like nucleus (Fig. 6 J-L, arrow). We hypothesize that the major single MTOC in the early egg chamber cannot form properly in the γ-tubulin double mutant, and some residual MTOC activity is left in one of the presumptive nurse cells at the time of centriole migration. This would interfere with the differentiation of the cell, which assumes an oocyte fate producing the 14 + 2 phenotype. To test our hypothesis we stained these egg chambers for α-tubulin (Fig. 6 M-P). We could rarely detect an accumulation of microtubules close to the second oocyte nucleus in stage 7/8 egg chambers (Fig. 6 M and N). Because in most instances this was not the case (Fig. 6 O and P), it is possible that the presence of MTOC activity might be required at an early stage of egg chamber differentiation for inducing the oocyte-like fate, and that the small MTOC is unstable and regresses as the egg chamber matures.

Fig. 6.

Egg chambers with defective oocyte determination in γTub23CPI fs(2)TW1RU34 mutant females. Egg chambers from WT (A, E, and I) or γTub23CPI fs(2)TW1RU34 (B-D, F-H, J-L, and M-P) females stained for DNA (gray in A-D, F, K, and L; red in E, H, and M-P), ring canals (gray in G, green in E and H) and microtubules (green in M-P). Posterior is to the right. (B-D) One of the two oocyte-like nuclei found within these egg chambers is always located posterior (arrowhead), as in the WT (A). The second oocyte-like nucleus (arrow) can be found anywhere within the egg chamber, posterior (D), anterior (C), or in the middle (B). It may have undergone a few rounds of endoreduplication in D.(F-H) One of the oocyte-like nuclei of this egg chamber is located posteriorly (arrowhead) within a cell with four ring canals (only two are visible). The oocyte has four ring canals in the WT (E). There are two more oocyte-like nuclei in the mutant egg chamber (arrows), located in cells with only one ring canal. H is a merge of F and G. (I and J) In situ hybridizations to osk mRNA. In the mutant (J) most signal is located within the posterior oocyte, similarly to what observed in a WT egg chamber (I), but there is also some accumulation of osk mRNA associated with the second oocyte-like cell (arrow in J). K and L are different focal planes of the egg chamber shown in J, stained with DAPI, to indicate the position of the oocyte nucleus (arrow in L) and the second oocyte-like nucleus (arrow in K). (M-P) Two examples of microtubule organization in 14 + 2 egg chambers at midoogenesis. N and P are higher-magnification images of the areas within the white boxes in M and O, respectively. In the egg chamber in M microtubules seem to accumulate around the second oocyte-like nucleus (N). No clear accumulation of microtubules close to the second oocyte-like nucleus can instead be detected in O and P. All images were obtained with conventional fluorescence microscopy, except E and M-P, which are confocal images, and I and J, which were obtained with phase-contrast microscopy. Egg chamber size is ≈150 μm.

Discussion

We have shown that γ-tubulin is required at different stages of female germ-line development. A severe lack of γ-tubulin function leads to germ-cell loss during pupal stages and results in agametic ovaries. A partial loss of function allows the survival of female germ cells, but results in a series of abnormalities during oogenesis, which indicate that γ-tubulin is also required during later stages.

In γTub23CPI fs(2)TW11 mutant animals germ cells are formed and develop normally until late larval stages, but become abnormally positioned within the ovary and start to degenerate at the onset of puparium formation. We show that in dividing female germ cells of γTub23CPI fs(2)TW11 homozygous late third-instar larvae both spindle organization and centrosome positioning are affected, similarly to what has previously been reported in larval neuroblast divisions of γTub23C mutants (34) and in the early embryonic divisions of embryos laid by γTub37C mutant mothers (36, 37). Thus, a likely cause for germ-cell loss in γTub23CPI fs(2)TW11 homozygous females is a failure in mitotic progression.

The precise timing of female germ-cell degeneration in γTub23CPI fs(2)TW11 mutants at the larva-to-pupa transition could simply be the result of the kinetics of exhaustion of maternally contributed γ-tubulin (33, 45). The same argument could also explain the differential sensitivity of male and female germ cells, because proliferation and differentiation occur earlier in the male than in the female germ line. An additional possibility would be a critical requirement of γ-tubulin for a germ line-specific function at the prepupa stage. The prepupa is thought to coincide with the timing of germ-cell differentiation (refs. 41, 46, and 47 and our data). It is conceivable that the onset of germ-cell differentiation is accompanied by a specific cytoskeletal reorganization, requiring defined levels of γ-tubulin.

The weaker γTub23CPI fs(2)TW1RU34 mutant combination allows oogenesis to proceed, but leads to a wide range of abnormal phenotypes, mostly affecting the number of nurse cells and oocytes within the egg chamber.

In CycE mutants (48) and different combinations of spindle mutants (49) none of the pro-oocytes reverts toward a nurse cell fate (4, 41), producing egg chambers with 14 nurse cells and 2 oocyte-like nuclei. In contrast, the ectopic oocyte-like nucleus in the 14 + 2 mutant egg chambers that we describe does not always correspond to the second pro-oocyte, but can be located anywhere in the cyst (Fig. 6 A-H). Thus, the formation of this ectopic oocyte could be better explained with a positive activation of the oocyte determination program in the wrong cell. Interestingly, we have shown that in few instances a microtubule focus is associated with the second oocyte-like nucleus, supporting the hypothesis that the determination of a second oocyte-like cell is caused by the ectopic presence of MTOC material associated with one of the nurse cells. This finding would imply that γ-tubulin is involved in properly organizing or positioning the MTOC. Furthermore, the initial steps of oocyte determination require a functional microtubule cytoskeleton that supports the proper branching of the fusome, which is in turn required for the polarized organization of the microtubule cytoskeleton (22). The investigation of the early stages of egg chamber formation in mutant germaria will help shed light on how this phenotype is generated.

At a low rate, γTub23CPI fs(2)TW1RU34 double mutant ovaries display alterations that have previously been reported to be produced as a consequence of colchicine treatment. These include egg chambers with 16 nurse cells and no oocyte (16 + 0), reduced oocyte size, and short and partially fused dorsal appendages (2). Interestingly, in the γTub23CPI fs(2)TW1RU34 mutant egg chambers microtubules are present, although they are not correctly organized. It thus seems that the same effect can be produced in the absence of microtubules or the presence of disorganized microtubules.

An additional conclusion that can be drawn from our results is that the two γ-tubulin products are functionally equivalent during female germ-cell development and oogenesis. In fact, with the only exception of the localization of bicoid RNA to the anterior cortex of the oocyte after stage 10b (31), either of them can provide the necessary γ-tubulin function required for these processes. We have previously shown that female meiosis and nuclear proliferation during early embryogenesis specifically require γTub37C (33) whereas somatic mitosis and spermatogenesis depend on the γTub23C gene product (34, 35). Although these observations argue that in some cases there is specificity of function, a definitive answer will require future functional tests of protein compatibility, after the ectopic expression of both proteins.

We have shown that γ-tubulin is required at different stages during female germ-cell differentiation. These include germ-cell development, cystoblast proliferation, and oocyte determination and differentiation. Some of these functions, like the differentiation of the oocyte among the 16 cystocytes, and oocyte growth, are known to be microtubule dependent. Additionally, we described a failure in proper microtubule organization in few instances. Therefore, the alterations produced by mutation in γ-tubulin can be interpreted as a defect in microtubule organization, thus providing a link between a universal component of the peri-centriolar material like γ-tubulin and microtubule organization during oogenesis. This finding is remarkable given the considerable divergence between the MTOCs that occur during oogenesis and more conventional centrosomes (reviewed in ref. 50).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to A. M. Michon, A. Ephrussi, P. Lasko, T. Kaufman, I. Clark, E. Wieschaus, L. Goldstein, and the Drosophila stock centers at Indiana University (Bloomington) and Umea, Sweden, for providing antibodies and fly strains used in this work. D. N. Cox, P. Gönczy, and B. Lange provided many helpful comments for this manuscript. Leica Lasertechnik, Heidelberg, kindly provided the TCS-NT confocal microscope used in this work to European Molecular Biology Laboratory. G.T. was a recipient of a European Molecular Biology Laboratory predoctoral fellowship. The Human Capital and Mobility Program of the European Community (CT96-005-970330) supported this work.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviation: MTOC, microtubule organizing center.

References

- 1.Spradling, A. C. (1993) in The Development of Drosophila melanogaster, eds. Bate, M. & Martinez-Arias, A. (Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press, Plainview, NY), pp. 1-70.

- 2.Koch, E. A. & Spitzer, R. H. (1983) Cell Tissue Res. 228, 21-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Theurkauf, W. E., Alberts, B. M., Jan, Y. N. & Jongens, T. A. (1993) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 118, 1169-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carpenter, A. T. (1994) Ciba Found. Symp. 182, 223-246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox, D. N., Lu, B., Sun, T. Q., Williams, L. T. & Jan, Y. N. (2001) Curr. Biol. 11, 75-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huynh, J. R., Shulman, J. M., Benton, R. & St. Johnston, D. (2001) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 128, 1201-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaccari, T. & Ephrussi, A. (2002) Curr. Biol. 12, 1524-1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roth, S., Jordan, P. & Karess, R. (1999) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 126, 927-934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonzalez-Reyes, A., Elliott, H. & St. Johnston, D. (1995) Nature 375, 654-658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roth, S., Neuman-Silberberg, F. S., Barcelo, G. & Schupbach, T. (1995) Cell 81, 967-978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Theurkauf, W. E. & Hazelrigg, T. I. (1998) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 125, 3655-3666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rongo, C. & Lehmann, R. (1996) Trends Genet. 12, 102-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grunert, S. & St. Johnston, D. (1996) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 6, 395-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riechmann, V. & Ephrussi, A. (2001) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 11, 374-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gutzeit, H. (1986) Roux's Arch. Dev. Biol. 195, 173-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Megraw, T. L. & Kaufman, T. C. (2000) Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 49, 385-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clark, I. E., Jan, L. Y. & Jan, Y. N. (1997) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 124, 461-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Theurkauf, W. E., Smiley, S., Wong, M. L. & Alberts, B. M. (1992) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 115, 923-936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cha, B. J., Koppetsch, B. S. & Theurkauf, W. E. (2001) Cell 106, 35-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahowald, A. P. & Strassheim, J. M. (1970) J. Cell Biol. 45, 306-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bolivar, J., Huynh, J. R., Lopez-Schier, H., Gonzalez, C., St. Johnston, D. & Gonzalez-Reyes, A. (2001) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 128, 1889-1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grieder, N. C., de Cuevas, M. & Spradling, A. C. (2000) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 127, 4253-4264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sonnenblick, B. P. (1950) in Biology of Drosophila, ed. Demerec, M. (Wiley, New York), pp. 62-167.

- 24.Clark, I., Giniger, E., Ruohola-Baker, H., Jan, L. Y. & Jan, Y. N. (1994) Curr. Biol. 4, 289-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li, M., McGrail, M., Serr, M. & Hays, T. S. (1994) J. Cell Biol. 126, 1475-1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heuer, J. G., Li, K. & Kaufman, T. C. (1995) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 121, 3861-3876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, K. & Kaufman, T. C. (1996) Cell 85, 585-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vaizel-Ohayon, D. & Schejter, E. D. (1999) Curr. Biol. 9, 889-898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Megraw, T. L., Li, K., Kao, L. R. & Kaufman, T. C. (1999) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 126, 2829-2839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cha, B. J., Serbus, L. R., Koppetsch, B. S. & Theurkauf, W. E. (2002) Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 592-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schnorrer, F., Luschnig, S., Koch, I. & Nusslein-Volhard, C. (2002) Dev. Cell 3, 685-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moritz, M. & Agard, D. A. (2001) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 11, 174-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tavosanis, G., Llamazares, S., Goulielmos, G. & Gonzalez, C. (1997) EMBO J. 16, 1809-1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sunkel, C. E., Gomes, R., Sampaio, P., Perdigao, J. & Gonzalez, C. (1995) EMBO J. 14, 28-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sampaio, P., Rebollo, E., Varmark, H., Sunkel, C. E. & Gonzalez, C. (2001) Curr. Biol. 11, 1788-1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Llamazares, S., Tavosanis, G. & Gonzalez, C. (1999) J. Cell Sci. 112, 659-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilson, P. G. & Borisy, G. G. (1998) Dev. Biol. 199, 273-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lindsley, D. L. & Zinn, G. G. (1992) The Genome of Drosophila melanogaster (Academic, San Diego).

- 39.St. Johnston, D. (1993) in The Development of Drosophila melanogaster, eds. Bate, M. & Martinez-Arias, A. (Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press, Plainview, NY), pp. 325-363.

- 40.Staab, S. & Steinmann-Zwicky, M. (1996) Mech. Dev. 54, 205-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.King, R. C. (1970) Ovarian Development in Drosophila melanogaster (Academic, New York).

- 42.Cummings, C. A. & Cronmiller, C. (1994) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 120, 381-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goode, S., Melnick, M., Chou, T. B. & Perrimon, N. (1996) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 122, 3863-3879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ephrussi, A., Dickinson, L. K. & Lehmann, R. (1991) Cell 66, 37-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilson, P. G., Zheng, Y., Oakley, C. E., Oakley, B. R., Borisy, G. G. & Fuller, M. T. (1997) Dev. Biol. 184, 207-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bhat, K. M. & Schedl, P. (1997) Dev. Dyn. 210, 371-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cox, D. N., Chao, A., Baker, J., Chang, L., Qiao, D. & Lin, H. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 3715-3727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lilly, M. A. & Spradling, A. C. (1996) Genes Dev. 10, 2514-2526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gonzalez-Reyes, A., Elliott, H. & St. Johnston, D. (1997) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 124, 4927-4937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gonzalez, C., Tavosanis, G. & Mollinari, C. (1998) J. Cell Sci. 111, 2697-2706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.