Eukaryotic transcription factors belong to a class of proteins that often have folded domains linked by intrinsically disordered segments. These modular proteins have an inherent problem of being resistant to crystallization and the concern that even if they were crystallized the resultant structure might not be representative of the one in solution because of crystal packing effects. They are also difficult to study by NMR because they are generally so large. A notable member of this class of proteins is the tumor suppressor p53, which is the key protein in the cell's defenses against cancer (1–3). p53 is ≈40% intrinsically disordered. Of 393 residues of each chain of its tetrameric structure, only residues 100–300, the core domain (CD) that binds sequence specifically to DNA, and residues 324–355, the tetramerization domain (Tet), are folded. The structures of the two domains were determined by x-ray crystallography and NMR methods. The CD adopts an Ig-like β-sandwich that provides a scaffold for a DNA binding surface (4, 5). The Tet forms a symmetrical tetramer made of two tight dimers stabilized by an antiparallel β-sheet and helix–helix interactions (6–9). The sequences of the p53 DNA binding sites or response ele-ments have four subsites, 5 bp long each, so that four CDs in tetrameric p53 can bind to one response element. Okorokov et al. (10) recently proposed a model for the structure of murine p53 on the basis of cryoelectron microscopy and single-particle analysis. Their model was very unusual in that it is composed of a skewed cube with the Tet being dissociated, so that four p53 monomers interact via their N and C termini. The arrangement of the CDs in this structure is not compatible with all four binding to the four subsites of the DNA response element, suggesting an alternative binding mode that has yet to be proven.

In this issue of PNAS, a team of several groups (11), led by Alan Fersht, has now proposed a quite different structure for human p53. This landmark study should be a paradigm for future work on complex multidomain proteins with folded and intrinsically disordered regions. To do this, they first had to use protein engineering to stabilize the intrinsically unstable wild-type p53 and generated a biologically active, stabilized mutant that is suitable for biophysical studies (12). They then used high-field NMR to find that the CD in the full-length protein has the same structure as isolated CDs that have been solved by x-ray crystallography (4) and NMR in solution (5). The NMR studies further showed that the protein is effectively a loosely coupled dimer of dimers of CDs and not a rigid tetrameric structure. They also detected from losses of signals which parts of the CD formed the dimer interface, and those transpired to be the same as the major dimer interface in the crystal structure of four separate CDs bound to a DNA binding site (13). Addition of a DNA response element caused the protein to rigidify. Small-angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) studies then showed that p53 has an elongated cross-shaped structure, with a pair of CD dimers at either end with the Tet domain being in the middle. On the addition of DNA to this “open conformation” of p53, the protein closed around the DNA, so it passed through a hole or a tunnel lined by the CD tetramer at one end, the Tet on the other, the two being connected by four unstructured chains illustrated by the cartoon in Fig. 1. Electron microscopy (EM) on the p53–DNA complex gave the same type of structure found by SAXS. But, the structure of the DNA-free p53 analyzed by EM was similar to that of the protein in the p53–DNA complex. This structure is unlikely to be biologically relevant because long DNA would not have access to its binding site on the CDs. The obvious explanation is that, as indicated by NMR, p53 is a dynamical ensemble of conformations, with the average structure being that determined by SAXS. However, immobilization under the conditions of the EM either selects a particular conformation or the compact conformations are the ones most visible. These findings demonstrate that structural determination of immobilized samples must be combined with measurements in solutions.

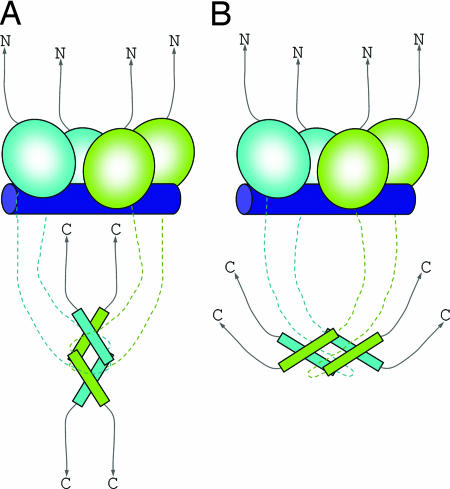

Fig. 1.

Cartoon models of p53 bound to DNA. (A) A model based on the structural model proposed by Kitayner et al. (13). (B) A model based on the EM structure proposed by Tidow et al. (11). The CD tetramer is composed of two identical dimers shown as pairs of green and cyan balloons. The Tet is shown as four elongated rectangles, each representing a long α-helix and a short β-strand. The two tetramers are connected by unstructured chains shown as broken lines of the corresponding color codes. The unstructured N and C termini are shown as curved arrows. The DNA response element is represented by a blue cylinder.

The model proposed by Fersht and colleagues (11) is consistent with the biological properties of p53. The extreme N terminus that includes a transactivation domain and the extreme C terminus that incorporates a regulatory domain are subject to posttranslational modifications as well as binding to other proteins, events that modulate p53 activity (3). In both the free and DNA-bound forms of p53, these regions can be accessed for such interactions. In the DNA-bound form, the relative arrangement of the core tetramer and the Tet is in accordance with the model proposed by Kitayner et al. (13) for full-length p53 on the basis of crystal structures of tetrameric CDs bound to four DNA subsites and symmetry considerations. However, in this model the long axis of the C-terminal tetramer is perpendicular to the DNA helix (Fig. 1A), whereas in the model derived by the EM analysis, the long axis of this tetramer is parallel to the DNA helix (Fig. 1B). The latter arrangement may have a functional advantage over the first one. In such a structure, the positively charged C termini at the ends of the four chains (two at each side) can interact at either side of the negatively charged long DNA helices, thereby helping to bend the DNA away from the CD tetramer, a direction proposed from solution studies on p53 bound to its DNA binding site (14). Both p53 architectures could be biologically functional depending on the specific DNA binding site (e.g., contiguous versus noncontiguous subsites) and the involvement of other proteins.

Future structural studies on p53 and its complexes with DNA and/or other proteins promise more exciting discoveries on the many different facets of this molecule that enable its functional diversity as the “guardian of the genome.”

Footnotes

The author declares no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page 12324.

References

- 1.Vogelstein B, Lane D, Levine AJ. Nature. 2000;408:307–310. doi: 10.1038/35042675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oren M. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:431–442. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laptenko O, Prives C. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:951–961. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cho Y, Gorina S, Jeffrey PD, Pavletich NP. Science. 1994;265:346–355. doi: 10.1126/science.8023157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canadillas JM, Tidow H, Freund SM, Rutherford TJ, Ang HC, Fersht AR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2109–2114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510941103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clore GM, Ernst J, Clubb R, Omichinski JG, Kennedy WM, Sakaguchi K, Appella E, Gronenborn AM. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:321–333. doi: 10.1038/nsb0495-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeffrey PD, Gorina S, Pavletich NP. Science. 1995;267:1498–1502. doi: 10.1126/science.7878469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee W, Harvey TS, Yin Y, Yau P, Litchfield D, Arrowsmith CH. Nat Struct Biol. 1994;1:877–890. doi: 10.1038/nsb1294-877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mittl PR, Chene P, Grutter MG. Acta Crystallogr D. 1998;54:86–89. doi: 10.1107/s0907444997006550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okorokov AL, Sherman MB, Plisson C, Grinkevich V, Sigmundsson K, Selivanova G, Milner J, Orlova EV. EMBO J. 2006;25:5191–5200. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tidow H, Melero R, Mylonas E, Freund SMV, Grossmann JG, Carazo JM, Svergun DI, Valle M, Fersht AR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:12324–12329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705069104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nikolova PV, Henckel J, Lane DP, Fersht AR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14675–14680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitayner M, Rozenberg H, Kessler N, Rabinovich D, Shaulov L, Haran TE, Shakked Z. Mol Cell. 2006;22:741–753. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagaich A, Zhurkin VB, Durrel SR, Jernigan RL, Appella E, Harrington RE. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:1875–1880. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]