Abstract

Background

Many randomized trials involve missing binary outcomes. Although many previous adjustments for missing binary outcomes have been proposed, none of these makes explicit use of randomization to bound the bias when the data are not missing at random.

Methods

We propose a novel approach that uses the randomization distribution to compute the anticipated maximum bias when missing at random does not hold due to an unobserved binary covariate (implying that missingness depends on outcome and treatment group). The anticipated maximum bias equals the product of two factors: (a) the anticipated maximum bias if there were complete confounding of the unobserved covariate with treatment group among subjects with an observed outcome and (b) an upper bound factor that depends only on the fraction missing in each randomization group. If less than 15% of subjects are missing in each group, the upper bound factor is less than .18.

Results

We illustrated the methodology using data from the Polyp Prevention Trial. We anticipated a maximum bias under complete confounding of .25. With only 7% and 9% missing in each arm, the upper bound factor, after adjusting for age and sex, was .10. The anticipated maximum bias of .25 × .10 =.025 would not have affected the conclusion of no treatment effect.

Conclusion

This approach is easy to implement and is particularly informative when less than 15% of subjects are missing in each arm.

Background

Missing outcome data are common in clinical studies [1,2]. Many approaches assume missing at random (MAR) as a base case. MAR means that the probability of missing depends only on observed variables [3]. Four strategies for examining the bias or sensitivity of results when MAR does not hold are to (i) fit all saturated MAR and non-MAR missing-data models [4,5], (ii) add a parameter to various MAR models to make them non-MAR and test if the fit is significantly improved [6,7], (iii) impute the missing data in one arm using the observed proportion of events in the other arm [8,9], (iv) estimate results under a non-MAR missing-data mechanism with key parameters specified by the investigator [1,10]-[13]. We propose a variation of method (iv) for randomized trials with binary outcome that explicitly uses the randomization distribution to reduce user input. To our knowledge this is the only method that exploits the randomization distribution for missing-data adjustment.

We illustrate the methodology using data from the Polyp Prevention Trial (PPT) in which 2079 men and women with recently removed colorectal adenoma were randomized to receive either intensive counseling to adopt a low-fat diet (intervention) or a standard brochure on healthy eating (control) [14]. The binary outcome was at least one adenoma detected on colonoscopy following randomization. In the control arm 9% of the subjects were missing the outcome, and in the intervention arm 7% were missing the outcome. Dropping the data from subjects with a missing outcome gives an estimated difference of -.002 (s.e.=.022) in the probability of adenoma recurrence between the intervention and control groups. Thus there was very little evidence that intensive counseling to adopt a low-fat diet reduced the probability of adenoma recurrence. An important question was whether or not an adjustment for the missing outcomes would have changed this conclusion.

Methods

Adjusting for Observed Covariates

As a starting point, we assume the data are missing at random (MAR). Let Y denote the binary outcome of adenoma recurrence. Let Z = 0 denote random assignment to the control group and Z = 1 denote random assignment to the intervention group. Also let R = 0 if the outcome is missing and 1 if the outcome is observed. Suppose we also have data on the observed variable S, which represents either strata formed by the cross-classification of categorical baseline covariates or outpoints of a continuous variable. Under the MAR assumption, the probability of missing depends on Z and S but not Y, namely,

pr(R = 1|z, s, Y = 1) = pr(R = 1 | z, s). (1)

Because R and Y are conditionally independent given Z and S, it follows from (1) that

pr(Y = 1|z, s, R = 1) = pr(Y = 1|z, s). (2)

In other words, under the MAR assumption in (1), the probability of adenoma recurrence conditional on treatment assignment and baseline covariates is the same in all subjects as in subjects not missing outcome. Baker and Laird [6] proved the related result that under MAR the maximum likelihood estimate of the probability of outcome conditional on covariates is the same in all subjects as in subjects not missing outcome.

With binary outcomes, the overall measure of treatment effect is typically a difference, a relative risk, or an odds ratio. We focus on the difference because it is easy to interpret [15] and because it simplifies our formulation. Let Δs denote the treatment effect for stratum 5, namely

Δs = pr(Y = 1|Z = 1, s) - pr(Y = 1|Z = 0, s). (3)

By virtue of the randomization pr (S = s|Z = 1) = pr(S = s|Z = 0) = pr(S = s). Therefore we can write the overall treatment effect as

Δ = ΣsΔs pr(S = s). (4)

If the missing-data mechanism is given in (1), then from (2), the treatment effect in stratum s (3) equals the treatment effect in stratum s among subjects with observed outcomes,

Δs = pr (Y = 1|Z = 1,s, R = 1) - pr(Y = 1|Z = 0, s, R = 1). (5)

Let nzsy denote the number of subjects in treatment group z and stratum s who have observed outcome y. Based on (5), we estimate Δs by

ds = qs1 - qs0, where qsz = nzs1/nzs+, (6)

where "+" denotes summation over the indicated subscript. Let Nzs denote the number of subjects (with either observed or missing outcomes) in treatment group z and stratum s. We estimate pr(S = s) by ws = N+s/N++, giving an overall estimate of treatment effect,

= Σsdsws (7)

= Σsdsws (7)

The estimate in (7) is closely related to the estimate proposed by Horvitz and Thompson [16]. It is also maximum likelihood because it is a function of maximum likelihood estimates of the parameters. Using the delta method, and noting that  = d1w1 + d2w2 + .... dh-1wh-1 + dh (1 -

= d1w1 + d2w2 + .... dh-1wh-1 + dh (1 -  ), we obtain

), we obtain

where wh = 1 -  .

.

Bias from an omitted binary covariate

Suppose that instead of (1), the probability of missingness depends on treatment assignment, baseline strata, and an unobserved binary covariate x. For our example from the Polyp Prevention Trial, x could be an unreported indicator of a family history of colon cancer. Then

pr(R = 1|z, s, x, Y = 1) = pr(R = 1|z, s, x). (9)

In other words the data would be MAR if x were observed. The model in (9) implies that, when x is not observed, missingness depends on outcome and on treatment group via

![]()

We assume that for each level of x within stratum s, the treatment effect is the same, namely

Δs = pr(Y = 1|Z = 1, s, x) - pr(Y = 1|Z = 0, s, x)

= pr(Y = 1|Z = 1, s, x, R = 1) - pr(Y = 1|Z = 0, s, x, R = 1) from (9) (11)

Importantly Δs in (11) does not depend on x. Let  denote the apparent treatment effect in stratum s after collapsing over x, namely,

denote the apparent treatment effect in stratum s after collapsing over x, namely,

To formalize the relationship between  and Δs let

and Δs let

αxs = pr(Y = 1|Z = 0, s, x, R = 1) (13)

ψs = α1s - α0s (14)

φzs = pr(X = 1|z, s, R = 1), (15)

εs = φ1s - φ0s. (16)

Combining (11) and (13), we can write

pr(Y = 1|Z = 1, s, x, R = 1) = αxs + Δs. (17)

Substituting (13)-(17) into (12) gives

![]()

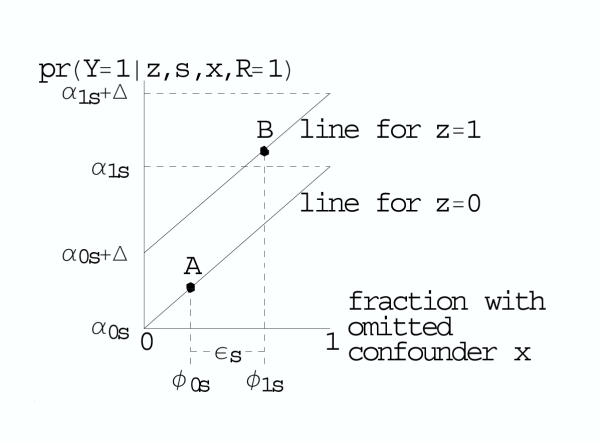

For a tabular display of these calculations see Table 1. For a graphical depiction based on the BK-plot [17,18], see Figure 1.

Table 1.

Cell probabilities in a generic stratum s

| randomization group | unobserved covariate | probability of outcome given group, unobserved covariate, s, not missing | probabilitity of unobserved covariate given group, s, not missing | probability of outcome given group, s not missing |

| Z | X | pr(Y = 1|z, s, x, R = 1) | pr(x|z, s, R = 1) | pr(Y = 1|z, s, R = 1) |

| = pr(Y = 1|z, s, x) if MAR | ||||

| 1 | 0 | α0s + Δs | (1 - φ1s) | |

| (α0s + Δs) (1 - φ1s) + (α1s + Δs) φ1s | ||||

| 1 | α1s + Δs | φ1s | ||

| 0 | 0 | α0s | (1 - φ0s) | |

| α0s(1 - φ0s) + α1s φ0s | ||||

| 1 | α1s | φ0s | ||

| difference between randomization groups: | Δs + ψsεs, where εs = φ1s - φ0s, ψs = α1s - α0s | |||

Under missing at random (MAR), the probabilities in the third column are the same for subjects not missing outcome as for all subjects, so Δs represents the true treatment effect, which is the same for both levels of x. Because the distribution of x is different among subjects not missing outcome in each randomization group, the apparent treatment effect is the difference in weighted averages over x in the last column, namely, Δs + ψsεs. To bound the overall bias Σsψsεspr (S = s), we specify an upper bound for εs based only on the fraction missing and a plausible value for the maximum of ψs based on the estimates of ψs if an observed covariate were missing.

Figure 1.

BK-plot of bias from an unobserved binary covariate among subjects not missing outcome. The upper diagonal line is the probability of outcome among subjects not missing outcome in randomization group Z = 1. The lower diagonal line is the probability of outcome among subjects not missing outcome in randomization group group Z = 0. For subjects in group 0, the fraction with X = 1 is φ0s and the probability of outcome is indicated by point A. For subjects in group 1, the fraction with X = 1 is φ1s and the probability of outcome is indicated by point B. The true treatment effect Δs is the difference between the diagonal lines. The apparent treatment effect Δs is the vertical distance between points A and B, which equals Δ + ψsεs, where εs = φ1s - φ0s and ψs = α1s - α0s = the slope of each diagonal line. To bound the overall bias Σsψsεspr(S = s), we specify an upper bound for εs based only on the fraction missing and a plausible value for the maximum of ψs based on the estimates of ψs if an observed covariate were missing.

From (18) the bias from omitting x in stratum s is ψs εs. The first factor

ψs = pr(Y = 1|Z = 0, s, X = 1, R = 1) - pr(Y = 1|Z = 0, s, X = 0, R = 1) (19)

is the effect of X on subjects in the control group with observed outcomes. By virtue of the MAR assumption in (9), we could also write ψs = pr(Y = 1|Z = 0, s, X = 1) - pr(Y = 1|Z = 0,5, X = 0), which is the effect of X on all subjects in the control group. The second factor,

εs = pr(X = 1|Z = 1, s, Z = 1) - pr(X = 1|Z = 0, s, R = 1), (20)

ranges from -1 to 1 and measures the degree of confounding between X and Z among subjects with observed outcomes (i.e. R = 1). If εs = 0, there is no confounding and no bias because the distribution of X among subjects with observed outcomes is the same in the control and study group. If εs = ± 1 there is complete confounding and the bias reaches the maximum value of ± ψs. Taking a weighted average over all strata, the overall apparent treatment effect is

and the overall bias is

bias = Σsψs εs ws. (22)

Remarkably it is possible to obtain simple bounds on εs based only on the proportion of subjects who are missing in each randomized group in stratum s. Let

πzs = pr(R = 1|z, s) (23)

denote the proportion of subjects in randomization group z and stratum s with an observed outcome. As derived in the Appendix See additional file: 1, the maximum εs, which we call the upper bound factor, is

![]()

If only 15% of the subjects are missing in each arm ε(max)s is less than .18. If we let ψmax denote the anticipated maximum value of ψs, then substituting (24) into (22) gives the anticipated maximum bias,

biasmax = ± ψmax Σs ε(max)s ws, (25)

where the anticipated maximum bias under complete confounding, ψmax, is specified by the investigator; the upper bound factor, ε(max)s, is based on the fraction with observed outcomes in stratum s; and ws is the fraction of subjects in stratum s.

Thus the investigator need only specify ψmax. One might argue that if x were a strong unobserved inherited gene, ψmax would be close to 1. However because, "eligible subjects had no history of colorectal cancer, surgical resection of adenomas, bowel resection, the polyposis syndrome, or inflammatory bowel disease" [14], it is unlikely that many subjects had an unobserved high-penetrance gene related to the recurrence of adenomas. We therefore believe that unobserved factors that might affect both adenoma recurrence and missingness could have an effect of similar magnitude as observed baseline covariates. Thus to obtain a plausible value for ψmax, we suggest estimating ψs, as defined in (19), based on observed covariates. (See the Results section.) Of course the relationship between observed covariates and missingness could differ substantially from the relationship between an unobserved covariate and missingness. Nevertheless, we believe that estimates of ψs from observed covariates are helpful for specifying a realistic value for ψmax.

Results

We applied our approach to data from the PPT trial stratified by age and sex (Table 2). We first assumed MAR and applied (7) and (8) to estimate the difference in the probabilities of adenoma recurrence between the two groups. We obtained  = -.003 with se(

= -.003 with se( ).=.022, which is close to the unstratified estimate and its standard error.

).=.022, which is close to the unstratified estimate and its standard error.

Table 2.

Results of Polyp Prevention Trial

| stratum s | adenoma | difference in observed | weight | bias factor ε(max)s | ||||

| stratum s | recurrence | rates of recurrence ds | ws | |||||

| sex | age | group | no | yes | missing | |||

| control | 573 | 374 | 94 (9%) | |||||

| study | 578 | 380 | 76 (7%) | |||||

| men | 30–49 | control | 33 | 22 | 5 (8%) | -.23 | .07 | .09 |

| study | 58 | 12 | 3 (4%) | |||||

| 40–59 | control | 99 | 76 | 7 (4%) | .01 | .17 | .05 | |

| study | 94 | 76 | 9 (5%) | |||||

| 60–69 | control | 122 | 105 | 25 (10%) | -.04 | .23 | .11 | |

| study | 144 | 105 | 18 (7%) | |||||

| 70–79 | control | 65 | 76 | 26 (16%) | -.04 | .13 | .20 | |

| study | 70 | 71 | 29 (17%) | |||||

| women | 30–49 | control | 54 | 11 | 3 (4%) | .03 | .10 | .07 |

| study | 47 | 12 | 4 (6%) | |||||

| 40–59 | control | 69 | 24 | 4 (4%) | .02 | .11 | .04 | |

| study | 69 | 27 | 4 (4%) | |||||

| 60–69 | control | 77 | 31 | 13(11%) | .08 | .12 | .11 | |

| study | 68 | 40 | 5 (4%) | |||||

| 70–79 | control | 54 | 29 | 11(12%) | .22 | .07 | .12 | |

| study | 28 | 37 | 4 (6%) | |||||

The overall estimate of the difference in probabilities of recurrence between study and control groups is ![]() = Σsdsws = -.003 with a standard error .022. We define ε(max)s = max((1 - π0s)/π1s, (1 - π1s)/π0s), where πzs equals one minus the fraction missing in group z and stratum s. The anticipated maximum bias is ψmax Σs ε(max)s ws = ± .10 ψmax, where ψmax is the anticipated bias if there were complete confounding of the unobserved covariate and treatment.

= Σsdsws = -.003 with a standard error .022. We define ε(max)s = max((1 - π0s)/π1s, (1 - π1s)/π0s), where πzs equals one minus the fraction missing in group z and stratum s. The anticipated maximum bias is ψmax Σs ε(max)s ws = ± .10 ψmax, where ψmax is the anticipated bias if there were complete confounding of the unobserved covariate and treatment.

To compute the anticipated maximum bias (25) we first computed ε(max)s using (24) and estimated ws from the observed fractions (Table 2). This gave Σsε(max)s ws = .10. We then specified ψmax, the anticipated maximum bias under complete confounding. To obtain a plausible value for ψmax, we estimated ψs in (19) pretending either sex or age was the unobserved covariate x. This gave  = .23, .18, .18, .19, for the four age categories when x = sex and .07 and .09 for the two sex categories when x = age. Treating the largest

= .23, .18, .18, .19, for the four age categories when x = sex and .07 and .09 for the two sex categories when x = age. Treating the largest  as a realistic lower bound for ψmax, we specified a slightly larger value, ψmax = .25, so that the anticipated maximum bias is biasmax = ± .25 × .10 = .025. The MAR confidence interval is shifted to the right or left by the anticipated maximum bias (Figure 2).

as a realistic lower bound for ψmax, we specified a slightly larger value, ψmax = .25, so that the anticipated maximum bias is biasmax = ± .25 × .10 = .025. The MAR confidence interval is shifted to the right or left by the anticipated maximum bias (Figure 2).

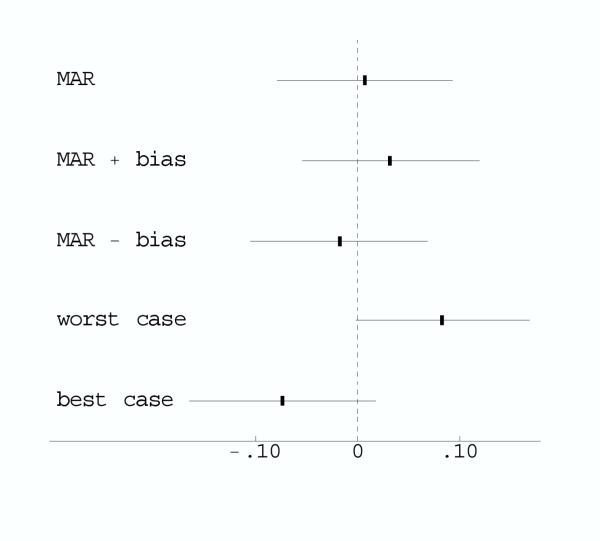

Figure 2.

Comparison of missing data adjustments for Polyp Prevention Trial. The graph plots the estimated differences in the probability of adenoma recurrence between the intevention and control groups and the 95% confidence intervals. MAR is missing at random within strata. MAR ± bias shifts the MAR confidence interval based on the anticipated maximum bias. Worst and best case imputes missing data to the randomization group that would give the largest positive and negative effect, respectively.

For purpose of comparison, we also computed estimates and confidence intervals under a worst (best) case imputation [9,19], where missing outcome data in each stratum were imputed as no recurrence (recurrence) in controls and recurrence (no recurrence) in the intervention group. (These stratum-specific estimates were combined over strata using weights inversely proportional to the stratum-specific variances.) In the worst and best case imputations the confidence intervals did not overlap zero (Figure 2).

Our sensitivity analysis showed that the worst and best case imputations were too extreme. Because the absolute value of the anticipated maximum bias, .025, is smaller than 1.96 × se ( ) = .043, the bias-adjusted confidence intervals overlap zero. Thus the anticipated maximum bias of ± .025 did not change our conclusion of little evidence of an effect of treatment on adenoma recurrence. However it did increase our uncertainty, as the more extreme lower and upper bounds indicated that the true effect of treatment could likely be higher or lower than indicated by the original analysis.

) = .043, the bias-adjusted confidence intervals overlap zero. Thus the anticipated maximum bias of ± .025 did not change our conclusion of little evidence of an effect of treatment on adenoma recurrence. However it did increase our uncertainty, as the more extreme lower and upper bounds indicated that the true effect of treatment could likely be higher or lower than indicated by the original analysis.

Discussion

The key idea of our method is to incorporate non-MAR missingness by postulating an unobserved binary covariate. Although similar in spirit to using an unobserved binary covariate with observational data [20], randomization adds important extra information that can be usefully exploited. Our formulation implies that the probability of missingness depends on both outcome and treatment assignment.

The proposed methods hinges on first selecting the appropriate baseline covariates. We agree with Myers [21] that if one anticipates missing data, one should collect information on the baseline covariates related to outcome that might predict missing in outcome. We assumed that within a stratum, the effect of treatment did not depend on the unobserved binary covariate. We view this as a main effect and thus a reasonable approximation.

We also agree with Shih [1] that one should collect information on the cause of missingness. In particular we recommend reporting whether any of the missing outcomes were definitely MAR, for example, due to random technical problems, to accidents, or to leaving the study for reasons completely unrelated to the investigation. Suppose that outcome was definitely MAR in a proportion vzs of subjects. Then it is more informative to write vzs as pr(R = 1, not MAR|z, s) + vzs. Because vzs contains no information about the effect of X on missingness, one can replace πzs by πzs - vzs, which reduces ε(max)s and hence reduces the anticipated maximum bias.

Although we applied our methodology to a cross-classification of categorical covariates, it could also be applied to continuous covariates or a univariate combination of covariates in a manner analogous to a propensity score [22]. Let u denote a vector of covariates and ez = pr(R = 1|z, u). Following the derivation of propensity scores [22], we can write, pr(R = 1|z, ez) = E(r|z, ez) = E(E(r|z, u)|z, ez) = E(ez|z, ez) = ez. Therefore pr(R = 1|z, u) = pr(R = 1|z, ez), and thus ez contains the same information for the probability of being observed as u. This calculation justifies using ez to summarize the covariates predicting missingness. To form five strata for randomized group z, we would compute ez for each subject in group z and then divide the distribution of ez into quintiles.

Conclusion

The bias due to an unobserved binary covariate could arise when the probability of missingness depends on both treatment and outcome. Computation of the bias is easy because it equals the maximum anticipated bias under complete confounding multiplied by an upper bound factor. The maximum anticipated bias might require some expert input but some lower bound values can be obtained using observed baseline covariate. The upper bound factor is easily computed from the fraction missing in each group. The methodology is particularly useful in the common situation when no more than 15% of the subjects (in excess of those definitely MAR) have missing outcomes, so that the upper bound factor in the bias is less than .18.

Contributions

SGB devised the basic model with the unobserved covariate, worked out the unconstrained maximization, and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. LSF worked out the constrained maximization and provided substantive improvements to the manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Stuart G Baker, Email: sb16i@nih.gov.

Laurence S Freedman, Email: lsf@actcom.co.il.

References

- Shih WJ. Problems in dealing with missing data and informative censoring in clinical trials. Current Controlled Trials in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2002;3:4. doi: 10.1186/1468-6708-3-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollis S. A graphical sensitivity analysis for clinical trials with non-ignorable missing binary outcome. Statistics in Medicine. 2002;21:3823–3834. doi: 10.1002/sim.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJ, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. John Wiley & Sons, New York. 1987.

- Baker SG, Rosenberger WF, DerSimonian R. Closed-form estimates for missing counts in two-way contingency tables. Statistics in Medicine. 1992;11:643–657. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780110509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molenberghs G, Kenward MG, Goetghebeur E. Sensitivity analysis for incomplete contingency tables: the Slovenian plebiscite case. Applied Statistics. 2001;40:15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Baker SG, Laird NM. Regression analysis for categorical variables with outcome subject to nonignorable nonresponse. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1988;83:62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Baker SG, Ko C, Graubard BI. A sensitivity analysis for nonrandomly missing categorical data arising from a national health disability survey. Biostatistics. 2003;4:41–56. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittes J, Lakatos E, Probstfield J. Surrogate endpoints in clinical trials: cardiovascular diseases. Statistics in Medicine. 1989;8:415–425. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780080405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proschan MA, McMahon RP, Shih JH, Hunsberger SA, Geller NI, Knatterud G, Wittes J. Sensitivity analysis using an imputation method for missing binary data in clinical trials. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference. 2001;96:155–165. doi: 10.1016/S0378-3758(00)00332-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vach W, Blettner M. Logistic regression with incompletely observed categorical covariates-investigating the sensitivity against violation of the missing at random assumption. Statistics in Medicine. 1995;14:1315–1329. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780141205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matts JP, Launder CA, Nelson ET, Miler C, Dain B. The Terry BeirnCommunity Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS. Statistics in Medicine. 1997;16:1943–1954. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19970915)16:17<1943::AID-SIM631>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotnitzky A, Wypij D. A note on the bias of estimators with missing data. Biometrics. 1994;50:1163–1170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharfstein DO, Rotnitzky A, Robins JM. Adjusting for nonignorable drop-out using semiparametric nonresponse models. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1999;94:1096–1148. (with discussion) [Google Scholar]

- Schatzkin A, Lanza E, Corle D, Lance P, Iber F, Caan B, Shike M, Weissfeld J, Burt R, Cooper MR, Kikendall JW, Cahill J, Freedman L, Marshall J, Schoen RE, Slattery M. The Polyp Prevention Trial Study Group. Lack of effect of a low-fat, high-fiber diet on the recurrence of colorectal adenomas. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342:1149–1155. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004203421601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton JL. Number need to treat: properties and problems. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A. 2000;163:403–419. [Google Scholar]

- Horvitz DG, Thompson DJ. A generalization of sampling without replacement from a finite population. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1952;47:663–685. [Google Scholar]

- Wainer H. The BK-Plot: Making Simpson's paradox clear to the masses. Chance. pp. 60–62.

- Baker SG, Kramer BS. Good for women, good for men, bad for people:Simpson's paradox and the importance of sex-specific analysis in observationalstudies. Journal of Women's Health & Gender-Based Medicine. 2001;10:867–872. doi: 10.1089/152460901753285769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz JL, Manski CF. Nonparametric analysis of randomizedexperiments with missing covariate and outcome data (with discussion). Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2000;95:77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Assessing sensitivity to an unobserved binarycovariate in an observational study with binary outcome. Journal of the RoyalStatistical Society, Series B. 1983;45:212–218. [Google Scholar]

- Myers WR. Handling missing data in clinical trials: an overview. DrugInformation Journal. 2000;34:525–533. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Reducing bias in observational studies using sub-classification on the propensity score. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1984;79:516–524. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.